CHAPTER 8

Walker’s Ridge

and Russell’s Top

The harsh conditions, and spread of disease, affected even the fittest young men at Anzac. Fred Hughes, now 57 years old, found them debilitating and could offer little resistance to the prevailing illnesses. Soon his health broke down. He lasted at his post for the first few weeks, but in June had to be evacuated suffering from pneumonia. He was in Egypt for a short time then spent most of the month on a hospital ship. No sooner had he returned than he was ill again and had to be sent back to the ship for a further week during July.

Hughes’ declining health and lack of fitness prevented him from taking a full and active role in the command of his brigade. Largely owing to this, and an awareness of the trouble he was having with a couple of his officers, most notably Brazier, he lost the trust of his superiors. Charles Bean, in a discreet footnote in the official history, says Birdwood now had little confidence in Hughes.1 When pressed in 1928 by Wilfrid Kent Hughes to justify this statement, Bean responded bluntly: ‘All I can say is … the authority for this is absolute.’2 Clearly Bean had been told this by Birdwood, or one of his most senior staff.

With the ageing Hughes unable to give proper attention to his work, most of the responsibility fell to Antill, who, it was acknowledged, became the main influence in the command of the brigade. Probably because the brigade major had a reputation for being strict and experienced, it was felt that there was no need to replace the brigadier. Senior officers who met Antill on Gallipoli were initially impressed by him as he conformed more to the style of the professional British army officers than most of the other Australians whom they encountered.

Reports of Antill’s work at Anzac spoke of his efficiency. He kept the headquarters staff working smoothly, there were few discipline problems, and the brigade’s trenches were among the best to be seen. While he certainly had ambitions to obtain the command of the brigade for himself, Antill did nothing to undermine Hughes’ position. Writing to his brother, he described Hughes as ‘a fine gentleman and my strongest and best friend – straight as a line’.3 In return, Hughes seems to have had full faith in him.

Birdwood should have taken steps to have Hughes retired. But it was an era in which it was not unusual for a senior officer to be retained despite the evidence showing that he was unsuitable. Declining ability and fading reputations were often overlooked. In a system where background and influence still held much weight, the simplest course was to take no action. Bean criticised the failure to remove these officers, but observed that it was a very common practice to do nothing in such circumstances.4 The practice of propping up ineffective commanders had become so ingrained in the British military system that it spilled over into the colonial and dominion forces, and was acknowledged as a matter of fact by Colonel Hubert Foster, the Director of Military Science at Sydney University before the war, in writing on the ‘Principles of command’. He wrote: ‘Only one man can command. It is true that the nominal Commander has not always been this one man, owing to some physical, intellectual or moral deficiency in his character.’ He added, ‘however, it is essential that the Chief must rely on one man only’.5 On Anzac Hughes had to some extent become, in Foster’s words, the brigade’s ‘nominal commander’.

Another commander too old to manage in the conditions on Gallipoli was Major James O’Brien, the 8th Light Horse’s second-in-command, who was also in his fifties. He was continually ill and had to be replaced. Miell, the commanding officer of the 9th Light Horse, also had health problems and had to go away for a short time. On another occasion he was wounded while asleep in his dug-out. It was not serious and he was back on duty after a week.

Carew Reynell, the second in command, continued to play an important role in the management of the 9th Light Horse. He was an exceptional soldier and had quickly gained a reputation as being quite fearless. He claimed as a great uncle a distinguished British officer at the battle of Waterloo, and he had a love of military history. His wife later wrote: ‘My husband had always been an ardent soldier. When he was 12 years of age he had read every book he could get about Military History including Napier’s Peninsula War – which he knew very thoroughly.’6 Reynell’s father had prevented him going off to the South African War because he was then still in his teens. He became an active militia officer and was a major in the 22nd Light Horse Regiment when the war commenced. He liked all aspects of soldiering – one of his sergeants complained that he had a ‘partiality for drill’, even on Gallipoli, and was inspired by what he saw as his role in the great military events taking place around him.

If courage was part of the Reynell family’s heritage, it was most evident in the generations which served in the world wars. Carew Reynell was to be killed on Gallipoli in an action in which he abandoned all caution. His son, Richard, who was then just two years old, served as a pilot in the Royal Air Force and died on 7 September 1940 while fighting in the Battle of Britain. May Reynell, herself a tireless war worker, lost her husband, brother and son in the wars. When writing of the circumstances of his death, Hughes had to say that Reynell ‘was too keen – if such is possible’.7

The last week in June was a tough one for the brigade and saw the 8th and 9th Regiments involved in their first big fight, with Reynell playing a notable part. But in the lead-up to this some casualties were suffered.

On the 27th, the enemy’s artillery commenced firing on Walker’s Ridge, and for a while the shells fell heavily upon the 8th Light Horse in the trenches opposite The Nek. Within half an hour seven men were killed and 15 wounded. The regimental headquarters was badly hit and Lieutenant Colonel White was wounded in the head; his second-in-command, Major Ernest Gregory, who was trying to organise stretcher parties, and the adjutant, Captain Joseph Crowl, were both killed.

The enemy gunners could hardly have hoped for a better bag. The loss of these prominent officers, who were central to the operation of the regiment, was a severe shock. Gregory’s experience had been admired – he had served 15 years, had recently spent six months with the British cavalry in India, and afterwards was in command of a militia light horse regiment – and Crowl’s ability respected. Because no regular soldiers of appropriate rank had been immediately available for the post of adjutant when the 8th Light Horse was being formed, ‘Terry’ Crowl, a second lieutenant from the militia, had been temporarily appointed. He performed so well, and had shown such promise, that he had been confirmed in the position and promoted.

Many in the regiment were affected by the officers’ deaths, including Trooper Alexander Borthwick. ‘I will be glad to take my uniform off, never to wear it again. To see a strong vigorous man like Captain Crowle [sic] have the life crushed out of him in a second by a shell is enough to make war revolting to any man.’8 A large group gathered around the graves of both men when they were buried side by side down near the beach.

Major Arthur Deeble was promoted into Gregory’s position and, for the moment, also filled in for Colonel White. Regarded as more fastidious than efficient, he was a university-educated suburban school principal who had enthusiastically devoted much of his spare time to soldiering. On Gallipoli he would have to face the raw edge of battle until, finally, he was taken off ill in September.9

White was evacuated with his wound, and later wrote: ‘This awful day. They shelled us with the French “75” at 5 am. I was hit at 5.30. Crowl and Gregory within a few minutes of each other – poor chaps they never knew what hit them. It was Gregory’s birthday too.’10 With some relief, he added: ‘They put me on a Hospital ship where the piece of shell was taken out, a hot bath, pyjamas, and sleep.’ At least he was free from the wild fighting which soon followed.

The shelling was resumed at intervals as a preliminary to a massed Turkish assault across The Nek in the early morning of 30 June. On a black, stormy night the enemy commenced with a feint against Quinn’s Post. Meanwhile artillery rounds fell on Russell’s Top, which was then subjected to heavy machine-gun and rifle fire. At midnight the men in the forward saps reported movement on the enemy’s front and those in the firing line and support trenches were alerted. Men began to file into position and stood shoulder to shoulder on the fire-steps, while behind them machine-gunners peered forward looking for signs of movement. About 15 minutes passed, then the Turks appeared, rising from the trenches and rushing forward in a massed attack.

The Australians were ready and met the enemy, as they came across The Nek, with a withering fire. Maxim guns, firing on fixed lines with well-measured ranges, scythed down dozens of them. Still they came on, many stumbling unaware into the forward saps, where sharp actions were fought with bombs and bayonets. For a while B Squadron of the 8th Light Horse took the brunt, but it never faltered, its concentrated fire dropping the enemy in front of them. The firing line was packed with riflemen, while many of the support troops, unable to find a place, climbed out of the back of the trenches to get a better shot. The Australians fired and reloaded, recharging their magazines like machines. Captain Archibald McLaurin, one of the few senior officers left in the 8th Light Horse, led a counter-attack to recover one of the main saps, which had been overrun.

On the left the enemy got into the long shallow front sap, which had been only lightly held, and about 50 of them crossed, continuing deep into the Australians’ positions. Reynell, revolver in hand, then quickly gathered a party and rushed up a communications trench, fighting his way into the front sap. Shots were exchanged at about three metres. More men followed, shooting and bombing, until the line was regained.

In the 9th Light Horse, Sergeant Cameron was leading his troop forward when he was ordered to reinforce the machine-gun post at Turk’s Point, which was threatened by the enemy, who had broken through. ‘The firing at this point was very heavy, and I lost one man before we got into position. Then we extended along the ridge and in doing so lost two more. It fairly rained hail [of bullets] there and they even succeeded in getting between our main trench and posts, but these were soon accounted for.’11

About this time the enemy tried to outflank the 8th Light Horse by moving around below the ridge on the right. They were seen and dealt with by bombs and by machine-guns from across on Pope’s Hill. By 2 am, the Turkish attack had been destroyed. Despite this, another assault was launched later in the morning. It was shot down as soon as the men had left the trenches. The Australians’ discipline never wavered, and the enemy, by attacking on such a narrow front, had no chance against both machine-guns and rapid, concentrated rifle fire. Captain ‘Naish’ Callary, of the 9th Light Horse wrote:

The Turks had a bad time. Our fellows said it reminded them of shooting rabbits running around. They were repulsed with severe losses as the morning showed when one could have a good look. Nothing but dead Turks all over the place. One gets used to the smell. How callous one gets. Such sights one sees and being so common and frequent makes one frightfully hard.12

At the height of the fighting the killing became automatic and impersonal. Walter McConnan wrote about it to his father: ‘Our rifle-fire not only checked them but piled them up in heaps. Of course a good many got away but our bag was good, I reckoned on a couple for my share. This was the most exciting time we had enjoyed till recently.’13 Reading this letter 70 years afterwards, his daughter commented: ‘at times I find it hard to reconcile some [of] his remarks with the truly gentle person he was’.14

Morning was a sobering experience. Sergeant Cameron, who had lost three of his men in the fighting, wrote:

I went around the trenches in the morning, and the sight that met one’s gaze was horrible. Dead Turks and some not quite dead were lying about like rabbits after a night’s poison had been laid. We rescued the wounded by throwing out ropes to which they fastened themselves and were drawn in; the dead near the trenches were dragged in and buried.15

The light horse casualties had been light: seven men killed and 19 wounded. The enemy’s losses amounted to hundreds, and dozens of them were buried by the Australians. The regiments remained alert but in the following days the Turks, obviously stunned by the scale of their defeat, were quiet. Captain George Wieck recalled how ‘scarcely a shot was fired at Russell’s Top during the whole of 30 June, and the men moved freely where previously it was death to venture’.16 The light horsemen were kept busy burying the dead, and cleaning up and repairing the trenches. The numerous bodies lying out in no-man’s-land could not be reached and remained there until the end of the campaign. Within days the stench from these decaying corpses enveloped Russell’s Top.

An interpreter from Godley’s headquarters, Aubrey Herbert, best known as a British member of parliament and a renowned Middle East traveller, was sent up to help bring in any Turks who might be still be lying wounded in front of the parapets. Scholarly, adventurous, and quite unmilitary looking, Herbert was one of the more eccentric members of the staff. Afterwards he often visited Russell’s Top and became good friends with Carew Reynell and young Kent Hughes. The entry in his diary about the day’s work provides a picture of the death and destruction following battle:

We found a first-rate Australian, Major Reynell. We went through the trenches, dripping with sweat; it was a boiling hot day. We had to crawl through a secret sap over a number of dead Turks, some of whom were in a ghastly condition, headless and covered with flies. Then out from the darkness into another sap, with a dead Turk to walk over. The Turkish trenches were 30 yards off, and the dead lay between the two lines. When I called I was answered at once by a Turk. He said he could not move … I gave him a drink, and Reynell and I carried him in, stumbling over the dead among whom he lay.17

Another occasional visitor was Charles Bean. Little escaped the notice of this lanky bespectacled man as he moved around the headquarters or through the trench lines. He developed a deep admiration for the types of Australians he found here, although he was never one of them, and was always awkward in the company of ordinary soldiers. Lieutenant Colonel White had been unimpressed by Bean and believed that if Donald McDonald, a Melbourne correspondent who had gone to the South African War, was covering the campaign instead of Bean, ‘you would have some splendid accounts of our life here’.18 White knew that one of Bean’s early despatches sent from Egypt, describing the wild behaviour of some of the first contingent, had been resented by the troops. He would never know that the author would one day immortalise the AIF in his remarkable official history.

In their attack across The Nek, the Turks had demonstrated, to their great cost, that it was impossible to cross this narrow stretch of ground in the face of machine-guns and massed rifle fire. In such a narrow space the advantage lay all too heavily with the defenders, regardless of which side of no-man’s-land they stood. The reputation of the ground in front of The Nek was now firmly established as a notorious killing field. The Turks had already given the place the name Jessarit Tepe (Hill of Valour).

It was the weaponry available, abetted by the terrain, which in the end set the nature of the campaign, and here the machine-gun dominated. Although both sides had more than one type of machine-gun, the main one each used on Gallipoli was essentially the same, the Maxim gun. The British Vickers gun, an improved version, was also beginning to come available. The Maxim was cumbersome and heavy because of its distinctive water cooling-jacket enclosing the barrel, but it was also reliable and deadly. It could pour out about 500 rounds per minute, and be fired over sights up to 2000–2300 metres. From a fixed mounting it could be set to shoot on predetermined targets on call. Employed in enfilade, a few guns in defence provided an impenetrable zone of fire.

On 2 July the 9th Light Horse was relieved and moved down to Rest Gully. The 8th Regiment followed a couple of days later and, while there, was reunited with its commanding officer who resumed duty with his head still heavily bandaged. When White saw the carnage from the battle, which had taken place in his absence, he said he could only feel sorry for the Turks.

It was little over a fortnight after the 8th Light Horse suffered the loss of two of its senior officers that tragedy struck again with the death of Captain Campbell, the regiment’s doctor. He, White and Dale had walked the kilometre to the beach to have an evening swim. It had been a quiet day and this was usually the safest time. However, while the men were undressing on a barge, a Turkish shell struck, tearing off Campbell’s lower legs before exploding and wounding others nearby. White and Dale were stunned. Campbell was rushed to a medical tent, but little could be done. He died on a hospital ship early next morning, 14 July.19 Colonel White, having cheated death once again, wrote home:

A sad, sad, day, poor dear Campbell, how we all loved him. Doctor, soldier, gentleman, friend … he was always so gentle, sympathetic and kind. The men loved him; the officers called him a man. Dear straight upright clean living Campbell, cut off just as your splendid life and career was just beginning, why should it be so? You who could so ill be spared to us. God comfort your parents; the whole Regiment mourns for you. Oh war is horrible.20

Despite the action and ordeals on Anzac, the brigade’s staff was still bothered by the attitude of Brazier back in Egypt, his lack of communication, and other petty problems. Brazier was now insisting that he took his orders from the local base commandant. In particular, a furore developed over the use of four motor cars the brigade had left behind. When Antill heard that Brazier was using one of the vehicles, he wrote demanding that they all be locked away and the keys sent to him on Anzac. Instead, Brazier referred the matter to the local commandant who approved the cars being used.

The situation reached new depths while Hughes was away from Gallipoli and convalescing in Egypt. He visited Brazier and stayed overnight at the camp. Brazier saw that Hughes was feeling the strain of active service and thought he looked ‘a wreck’. Next morning the brigadier asked for the four cars to accompany him to Cairo so that he could collect some troops’ comforts. Instead, when he reached the Australian Base Office he dismissed the drivers and sent the cars on to the motor transport company. After he left, Brazier, who had been tipped off, simply went back to the base commandant and obtained authority to have the vehicles returned to him. Hughes, of course, was furious when he heard of this further defiance.

Hughes and Antill were also not very happy with Major Alan Love, who was acting in command of the 10th Light Horse. It was thought that he bore many of Brazier’s attitudes. He became unpopular, and lost a lot of support within the regiment, when he devised a scheme to send out a party of about ten men to attack, and then destroy with explosives, an enemy strongpoint called Snipers’ Nest. Kidd, who had been lucky to survive when he led the attack at Quinn’s post, was very critical of the plan which showed little regard for the lives of the men. He reported that the ‘party came back quicker than they went. To perform the job in one night under the nose of a strong Turkish outpost appears to me to have emanated from a hysterical brain.’21 Foss described it as ‘an extremely risky and somewhat inglorious episode.’22

A week before receiving his movement orders, Brazier got a note from Love:

I am informed by Brigade HQrs that you are expected here any day and the sooner the better for they are worrying the life out of me. A CO has not only to fight the enemy but the staff as well. I have been bad with diarrhoea for about 14 days and am just about played out. I understand the Brigadier was very annoyed with you over something, hence his decision to relieve you and get you over here.23

Against the last sentence Brazier scribbled triumphantly: ‘Motor Cars – he got licked.’ Love continued:

Antill is as great a bully as ever and leads us a cat and dog life – I understand there is a possibility of his getting command of the brigade if the Brigadier again breaks down. What ho, then! When you come take my advice and bring fruit, cocoa, coffee, and tin soups or such like, as there is nothing here, but tin dog.

Brazier left Alexandria on 27 July, handing his duties over to Major Daly of the 9th Light Horse, and arrived at Anzac three days later to resume command of his regiment. Hughes apprised him of the situation and escorted him around the trenches on Russell’s Top. For the moment their mutual animosity was thinly concealed.

Throughout July the three regiments’ casualties through enemy action and sickness continued to mount. On 12 July, McFarlane, the staff captain, was hit. He received a severe leg wound which required his being sent away and eventually returned to Australia. He was replaced by another regular officer, but when he became ill young Kent Hughes was appointed to act in the position. The replacement of a veteran professional soldier by the brigadier’s 20-year-old nephew, who had only held his rank of second lieutenant for a few weeks, has to be seen as a weakening of the brigade’s command capacity and a strengthening of Antill’s hand. One can only speculate on what role McFarlane might have played had he been present during the charge at The Nek, but his experience must have been missed.

One of the 8th Light Horse officers commented that: ‘Our acting staff captain Billy Kent Hughes was a mere boy, very good natured and thoroughly inexperienced. Like the Brigadier, he left most things to the brigade major, who largely trusted to luck and countermanded his own orders.’24

Kent Hughes was a remarkable young man. He had been awarded a Rhodes scholarship before leaving for the war, was later an Olympic athlete, served in both wars and became a well known member of state and federal parliaments. He was eventually promoted to brigade major of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade and performed well throughout the later desert campaign. Antill described him as ‘a fine boy,’ adding, ‘we took him from the ranks’.25 In mid-June Kent Hughes received a minor bullet wound to the arm and was sent off to the hospital ship, where he joined his uncle for a couple of days. He was also to see his father, who had obtained a commission in the Australian Army Medical Corps and was now attached to No. 3 Australian General Hospital on Lemnos; they met briefly on the beach during a visit his father made to Anzac.26

While more senior officers were watching Hughes’ performance, he was assessing that of his own officers. The two eldest commanding officers, Brazier and Miell, had not impressed Hughes to the extent that White had done, and he increasingly felt that Brazier was unfit for his position. From his three regiments he believed that White, Reynell, and Todd of the 10th Light Horse were the best of those he had available.

Major Tom Todd was an important member of his regiment. Although a 41-year-old city accountant, he had shown that he was not out of place among the hardiest of his unit’s bushmen. Described as ‘over six feet in height, with a powerful, resonant voice and a tremendous virility and energy’, he had learnt his soldiering with the New Zealanders as a young lieutenant on the South African veldt.27 He was one of that war’s early colonial heroes, being awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his work during 1900. His experience had been invaluable when the 10th Light Horse was being formed and trained. At home in Perth he had been called ‘the life and soul of Claremont’ camp.28 He was quickly promoted and given command of A Squadron. There was an uneasiness in Brazier’s relations with Todd, whom he must have seen as a reminder of his own limited experience and lack of active service.

George Lambert, The charge of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade at The Nek, 7 August 1915. (AWM ART07965)

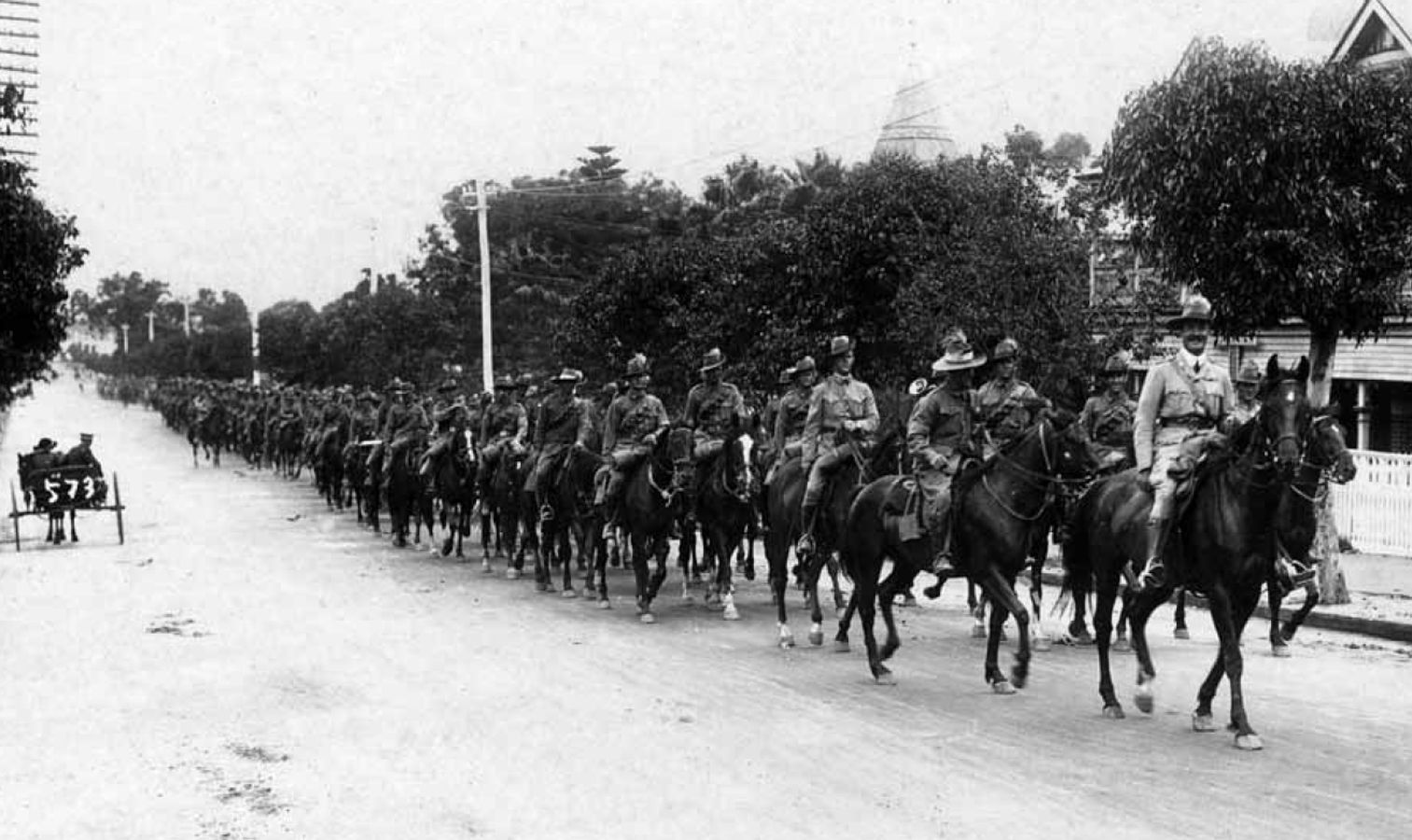

Major Tom Todd leads a parade of the 10th Light Horse Regiment before departing for the war. Instead of acting in a mounted role, the regiment served in the trenches alongside the infantry on Gallipoli. (AWM P09573.005)

Colonel Frederic Hughes who commanded the 3rd Light Horse Brigade during the charge at The Nek. This formal portrait was taken before the brigade left Australia. (AWM H19195)

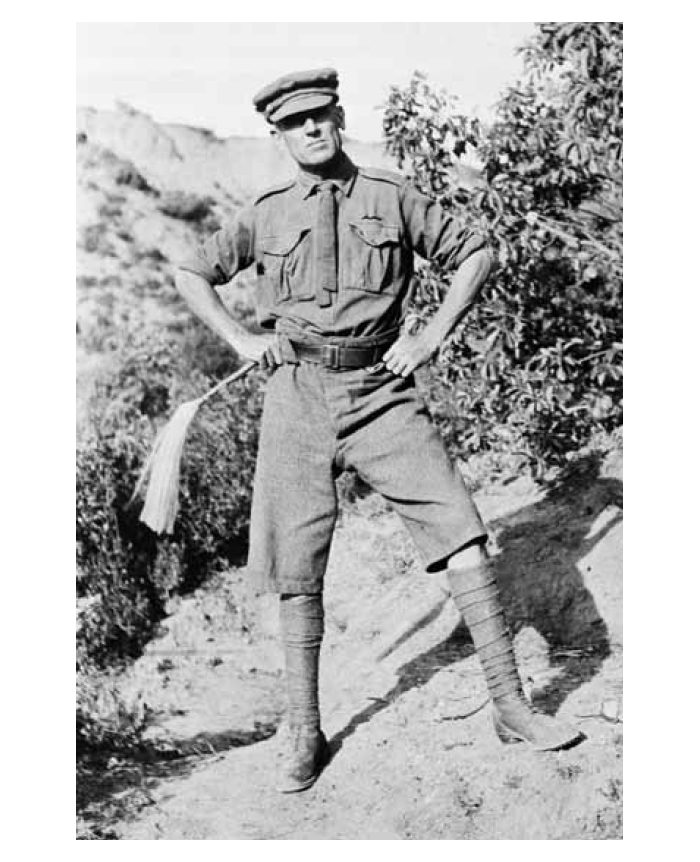

Lieutenant Colonel Noel Brazier, commanding officer of the 10th Light Horse Regiment. He is in the uniform of the regiment he commanded before the war. Brazier tried unsuccessfully

to have the charge at The Nek stopped. (AWM P0783/01)

Lieutenant Colonel Alexander White, of the 8th Light Horse Regiment, with his wife and infant son, shortly after his appointment to command the regiment. He died leading his men at The Nek. (Mrs M. McPherson)

Lieutenant Colonel Jack Antill was the Brigade Major of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade at the charge at The Nek. He was later promoted to command the brigade. (AWM G01330)

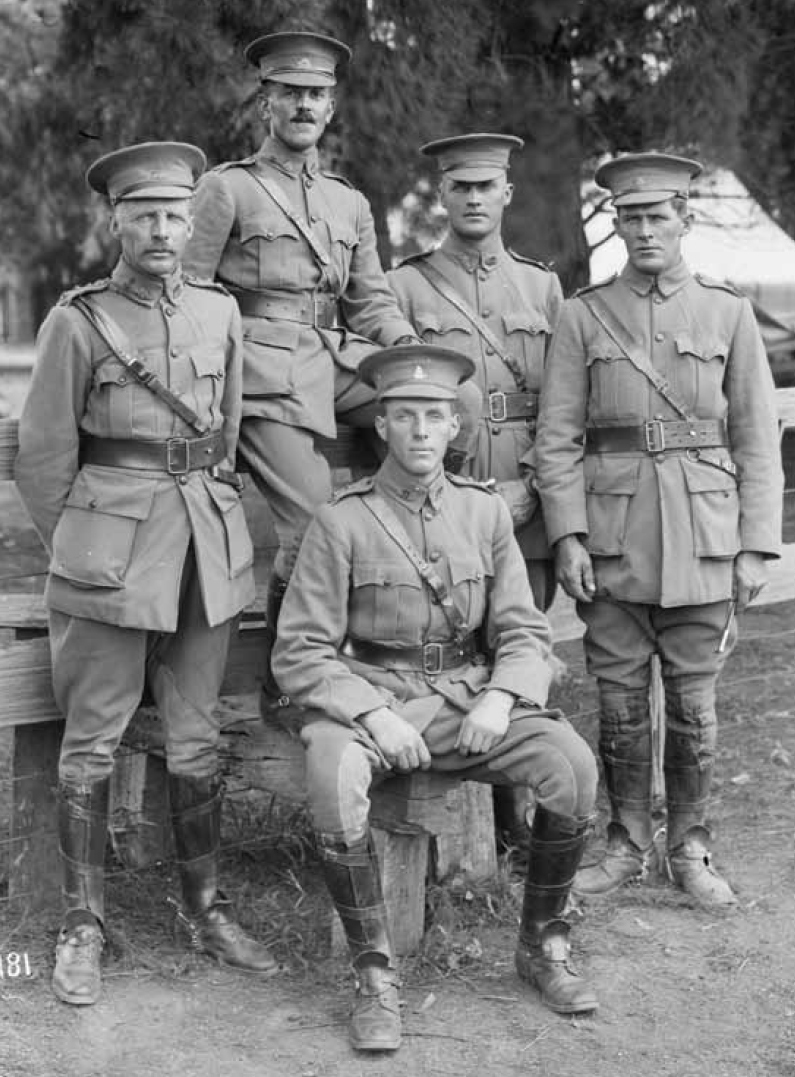

Officers of C Squadron, 8th Light Horse Regiment, in camp at Broadmeadows. All took part in the charge at The Nek. (L to R) Captain A. McLaurin (wounded), Major A. Deeble, Lieutenant C. Dale (killed), Second Lieutenant W. Robinson (wounded), and Second Lieutenant C. Carthew (killed). Only Deeble survived the action uninjured. (AWM DAX0181)

Recently arrived at Anzac, some of B Squadron of the 8th Light Horse Regiment are gathered in a rest area behind the front line. They were soon to man the trenches at The Nek. (AWM H03164)

Central characters in The Nek drama on the slopes of Walker’s Ridge, near the 3rd Light Horse Brigade’s headquarters. The divisional commander, General Godley (left), is speaking to Colonel Hughes (centre, light jacket) and Lieutenant Colonel Antill (right). (AWM J02715)

Light horsemen in the trenches at The Nek. Trench warfare was dramatically different from the mounted operations the light horse expected when they enlisted. (AWM J02719)

In the trenches on Gallipoli, Major Thomas Redford

observes the enemy lines using a periscope. He was later

killed in the 8th Light Horse’s charge on 7 August 1915.

(AWM H03124)

A crew of the 9th Light Horse Regiment manning the machine-gun at Turk’s Point. This gun fired on the Turks across The Nek during the attack on 7 August 1915.(AWM J02704)

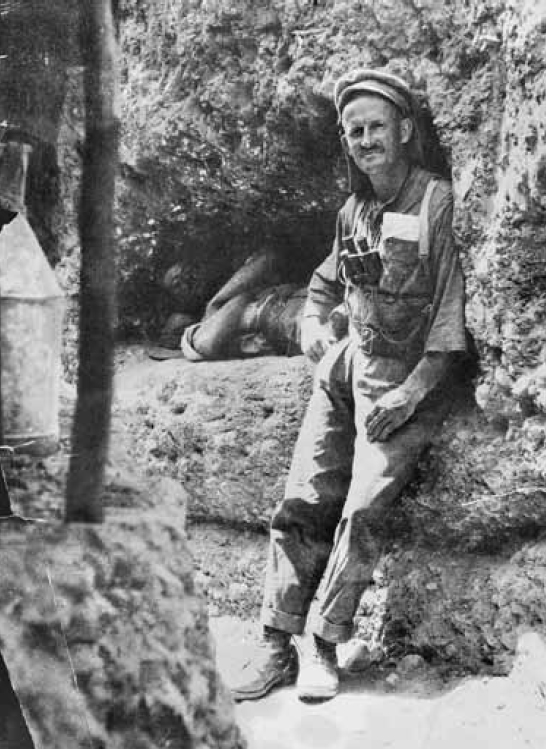

Signaller James Campbell of the 8th Light Horse Regiment,in his dugout burrowed into the rear slopes of Walker’s

Ridge at Anzac. (AWM H03197)

Captain Phil Fry of the 10th Light Horse Regiment in

the trenches at The Nek. The popular officer survived

the charge on 7 August but was killed at Hill 60

three weeks later. (AWM A05401)

No-man’s-land at The Nek on the only occasion that it was safe to be there, the armistice to bury the dead on 24 May 1915. (AWM H03920)

An aerial view of The Nek battlefield. This 1923 photograph shows the construction of the cemetery on the former no-man’s-land. Australian trenches are still visible in the foreground and the monument erected by the Turks stands beyond the graves. (AWM H18635)

The battlefield at The Nek as Charles Bean found it in 1919. The Australian trenches are in the foreground, while the Turkish lines are identified by their monument. Note the skyline, which suggests this photograph was taken in the vicinity of the one showing the armistice (see next page) in May 1915. (AWM G02013A)

Men of the 10th Light Horse gathered behind Walker’s Ridge. The white armbands were issued for the attack at dawn on 7 August 1915, so it can be concluded that these are some of the survivors. (AWM P0516/05/02)

After the battle, survivors of the 10th Light Horse on Walker’s Ridge collect the unclaimed kits of those who were casualties in the regiment’s tragic charge at The Nek. (AWM P00516.005)

The last living survivor of the charge at The Nek, Lionel Simpson DCM, died in 1991 aged 100. In 1984 he visited George Lambert’s famous painting of the action. (Author)

Sunday crowds in Melbourne outside The Argus newspaper office anxiously await further reports of the fighting on Gallipoli, and the inevitable accompanying long list of casualties. (AWM H11613)