Kaibara Ekken (1630–1714) was one of the leading Neo-Confucian thinkers of early modern Japan. Born in the beginning of the Tokugawa era (1600–1863), he had a significant intellectual influence during the period and is well respected in his birthplace of Fukuoka in northern Kyushu down to the present.1 Ekken was raised in a lower-ranking samurai family, was sent to study in Kyoto by the local provincial government (han), and subsequently was employed by the provincial lord (daimyo) as a government adviser. This ensured his career as a scholar and writer relatively free from financial concerns. His remarkable productivity was, no doubt, due to his moderate but secure income, as well as to the peaceful conditions established by the unification of the country under the Tokugawa shogunate. Moreover, he received invaluable assistance from his nephew, Kaibara Chiken, and his disciple Takeda Shun’an. In addition, his wife was a talented woman who, it is conjectured, collaborated with him in some of his writings, particularly his diaries and travel accounts. Ekken was not unaware of these fortunate circumstances supporting his scholarly life. He frequently spoke of a feeling of gratitude for blessings received and the need to repay one’s debt to the human and natural forces that sustain a person’s life.

Ekken’s sense of gratitude was closely linked to his empathic understanding of the suffering dimension of life, as he lost both his mother and his stepmother at an early age. Ekken’s sympathies toward the more difficult aspects of life were, no doubt, also nurtured by growing up primarily amid townspeople outside the castle of the ruling daimyo rather than only among the samurai class. Furthermore, he lived for several of his early years in the countryside, where his proximity to the daily life of farmers inevitably stimulated his later interest in agriculture and botany. This breadth of life experience is reflected in the wide range of his concerns in his lecturing, research, and writing.

These early experiences were expanded by his later studies in Kyoto and his frequent opportunities to travel. For seven years he studied in Kyoto, the intellectual capital of his time. There he met many of the most illustrious Confucian scholars of Japan, including Kinoshita Jun’an (1621–1698), Yamazaki Ansai (1618–1682), and Itō Jinsai (1627–1705). He maintained contact with several of these scholars and paid them visits on his return trips to Kyoto. He also traveled on various occasions to the political capital, Edo (Tokyo), where he met one of the leading government advisers, the Confucian scholar Hayashi Gahō (1618–1680). In addition, he frequently visited the port city of Nagasaki in Kyushu, where he could purchase Chinese books and occasionally even Western ones. It was there at age twenty-one that he obtained a copy of the Song Neo-Confucian scholar Zhu Xi’s (1130–1200) most important work, Reflections on Things at Hand (Jinsilu). Seventeen years later, he wrote the first Japanese commentary on this text, Notes on Reflections on Things at Hand (Kinshiroku bikō). This marked a significant moment in the introduction of Neo-Confucian thought into the Japanese context. It also signaled Ekken’s enormous appreciation for Zhu Xi’s comprehensive Neo-Confucian synthesis.

Ekken’s lifelong preoccupation with Zhu became an impetus for introducing Confucian ideas and ethics into Japanese society, politics, and education. Ekken’s breadth of concerns and understanding regarding Confucian thought reflects his life experience, his opportunities for travel, and his contacts with scholars and other classes in society. Impressive in Ekken’s writings is not only the range and volume of his production, but also the sincerity and humility of his own voice. From high-level Confucian scholarship to popular treatises on Confucian morality, and from botanical and agricultural studies to provincial topographies and genealogies, Ekken demonstrated a commitment to intellectual and ethical concerns rarely surpassed in the Tokugawa period.

In terms of Confucian scholarship, in addition to his appreciative commentary on Zhu Xi’s Reflections on Things at Hand, Ekken’s most important philosophical work, the Record of Great Doubts (Taigiroku), sets forth his disagreements with Zhu Xi.2 These two texts illustrate the extent of both affirmation and dissent Ekken displayed in his interactions with the writings of this leading Chinese Neo-Confucian philosopher. His ability to be simultaneously appreciative and critical reflects something of the dynamic quality of the Confucian tradition itself. As On-cho Ng and Kai-wing Chow have suggested, “Confucianism was never a formalism of ideas frozen in time, reified as immutable dogmas. Its very vitality, dynamism, and existence depended on its remaking and reinventing itself.”3 Reinventing itself over many centuries, Confucianism and its later form of Neo-Confucianism passed from China to Korea and then to Japan by means of a complex and at times contested set of texts, dialogues, and commentaries. This rich interaction of the tradition with different cultural contexts and in response to new social and political urgencies is especially present in Ekken’s efforts to adapt Confucianism to the Japanese context.

The reflections in the Record of Great Doubts of a seventeenth-century Japanese intellectual on some of the key philosophical ideas of a twelfth-century synthesizer of Neo-Confucianism illustrate the intellectual vitality of the Confucian tradition; a gap of five centuries did not lessen the importance of the arguments related to how one lived one’s life and contributed to society. In the Record of Great Doubts, Ekken argues for a philosophy of vitalistic naturalism as a basis for moral self-cultivation and for active response to social and political affairs. He resists any potential tendencies in Neo-Confucian thought toward transcendental escapism, quietism, or self-centered cultivation. He aims instead to articulate a dynamic philosophy of material force (C. qi or ch’i, J. ki) as a unifying basis for the interaction of self, society, and nature. This philosophy is sometimes called a monism of qi because it posits a nondualistic integration of li (principle) and qi. In this context, self-cultivation becomes a primary means for an integrated life. Ekken emphasizes that material force as the vital spirit present in all life needs to be cultivated in oneself and enjoyed in nature.

The Record of Great Doubts is, then, a broad summary of Ekken’s commitment to a monism of qi. This is the philosophical grounding for Ekken’s dual interests in popularizing Confucian ethics and providing pragmatic assistance to various classes in society. Understanding principle in daily affairs was the basis for both ethics and action. His unified worldview provided a holistic and convincing basis for adopting Confucianism into Japan. In order to spread Confucian ideas among a wide variety of people, Ekken wrote moral treatises (kunmono) in a simplified Japanese style addressed to particular groups, including samurai, families, women, and children.4 This was part of his profound commitment to Confucian ideas and practices as being a valuable contribution to Japanese society in its emerging period of peace and stability. For establishing a new moral social-political order, Confucianism was considered by many to be an indispensable philosophy.5 Ekken’s writings and teachings contributed significantly to its spread and nativization in his comparisons of Confucianism with Shinto. As naturalistic philosophies emphasizing virtues such as authenticity and sincerity, Confucianism and Shinto were seen by many scholars as having similar concerns. Ekken illustrated this in his essay Precepts on the Gods (Jingikun), where he equates the way of the Confucian sages with the way of the Japanese gods (kami). He also observed that the principles of change and constancy in nature were essential to both traditions.

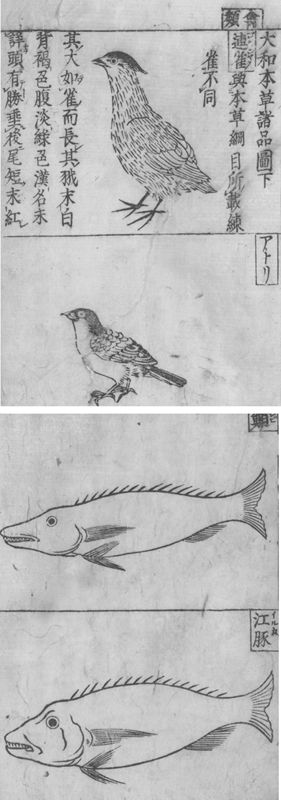

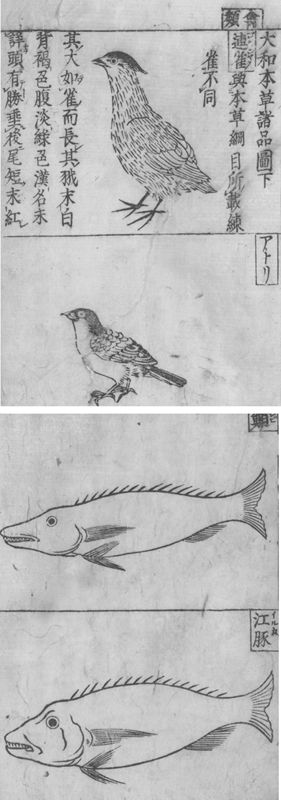

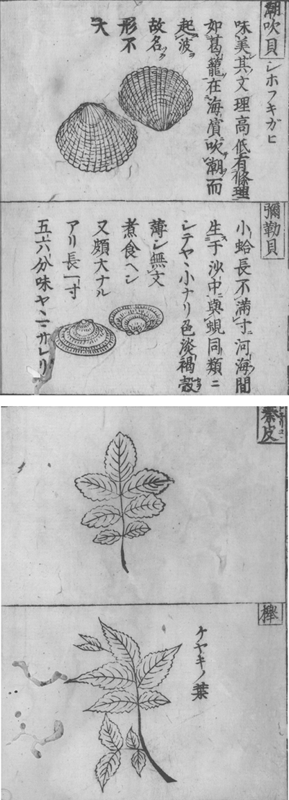

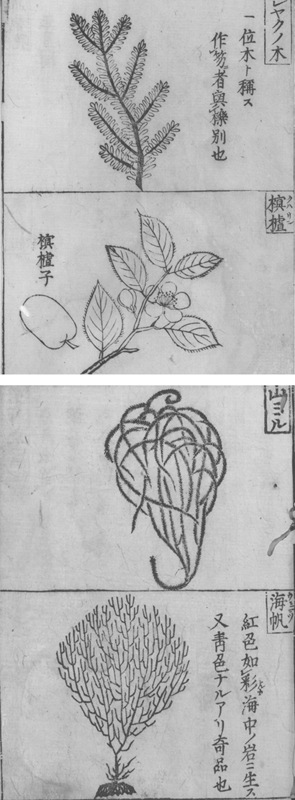

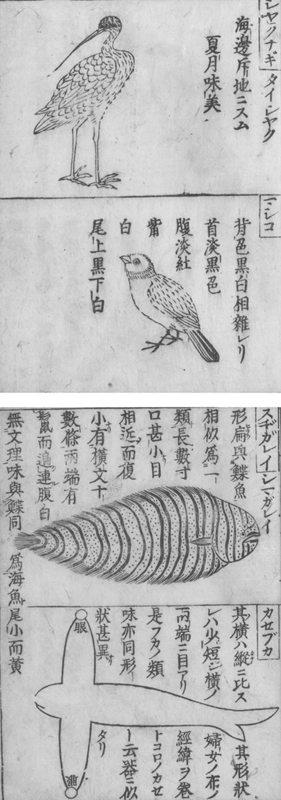

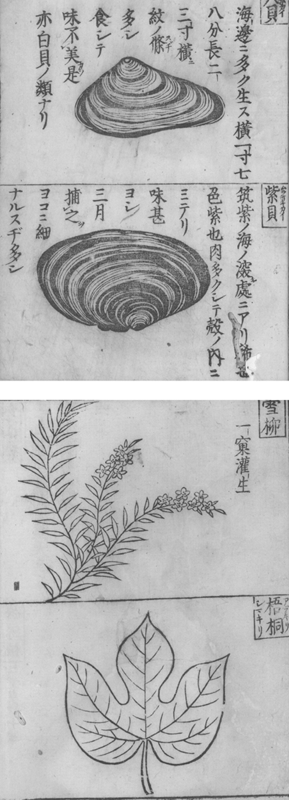

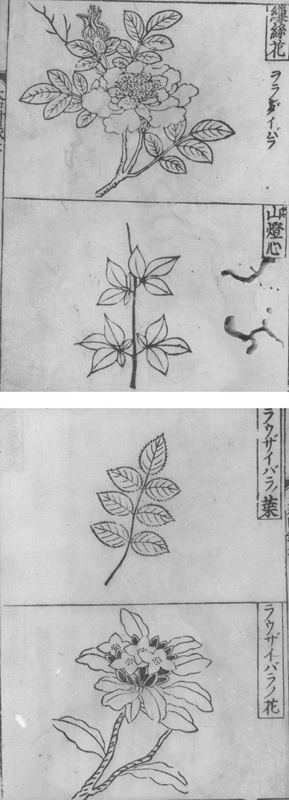

The other major thrust of Ekken’s thought was pragmatic and involved what has been termed practical learning (jitsugaku).6 Here Ekken’s interests encompassed such areas as medicine, botany, agriculture, astronomy, geography, and mathematics. One of his best-known works of practical learning is Plants of Japan (Yamato honzō), a natural history of plants, herbs, shells, fish, and birds. It is based on the long-established tradition in China of plant taxonomy. In addition, his Precepts on Health Care (Yōjōkun) is still popular in Japan.7 Moreover, he wrote an introduction to Miyazaki Yasusada’s agricultural treatise Nōgyō zensho, an important explanation of farming techniques intended to assist farmers. He also contributed to local history and geography through his genealogies of the Kuroda han and his travelogues and diaries. Ekken’s diverse interests in practical learning and in investigating things in nature led him to be called the Aristotle of Japan by a German naturalist.8

Underlying the clearly extraordinary range of Ekken’s intellectual and moral concerns is his philosophical commitment to a vitalism expressed as a monism of qi, contrasting with the qualified dualism articulated by some Neo-Confucians, such as Zhu Xi, who distinguished between principle and material force. Hence the significance of Ekken’s Record of Great Doubts, which explains his reservations and commitments in subtle detail. This work constitutes a central philosophical text in the history of Japanese Neo-Confucianism, and for this reason warrants discussion, explication, and interpretation. The translation that follows is made available with the hope that by situating it within its East Asian philosophical lineage and its Japanese historical context, it will provoke further discussion regarding the formulation of cosmology and ethics in the Tokugawa period.9

The Text in the Context of East Asian Confucianism

Confucianism has been the primary vehicle for the transmission of humanistic learning and moral values in East Asia. Its imprint has been considerable not only in China but in Korea, Japan, and Vietnam as well. Indeed, it is important to note the great variety of scholars, texts, and schools that the term “Confucianism” embraces over time and across cultures. Thus it may be helpful to sketch briefly the development of Confucianism itself so as to locate the text within its larger East Asian philosophical and religious context.

Confucianism refers most basically to the thought of Confucius (Kong Qiu, 551–479 B.C.E.) and his followers in China, especially Mencius (385?–312? B.C.E.) and Xunzi (307–219? B.C.E.). This classical period (ca. 551–223 B.C.E.) of remarkable intellectual flourishing is frequently called the period of the hundred philosophers. Born in a time of rapid social change, Confucius devoted his life to reestablishing order through rectification of the individual and the state. This involved a creative transmission of earlier Chinese traditions embracing moral, political, and religious components. The texts of the early Confucian tradition are known as the Five Classics: the Classics of History, Poetry, Changes, and Rites, and the Spring and Autumn Annals.

The principal teachings of Confucius, as contained in the Analects, emphasize the practice of moral virtues, especially humaneness or love (ren) and filiality (xiao). These were exemplified by the “noble person” (junzi) particularly in the five relations: between parent and child, ruler and minister, husband and wife, older and younger siblings, and friend and friend. From the time of the Han dynasty (202 B.C.E.–226 C.E.), these basic Confucian ideals and their larger cosmological implications played a pivotal role in Chinese thought and institutions. Indeed, the main purpose of Han Confucianism was to elucidate the interrelations of the natural, social, and political orders so that both ruler and individuals could be effective moral agents. Heaven, Earth, and humans were seen as part of a dynamic system; by participating in this system, humans fulfilled their role in this trinity and assisted in “the transforming and nourishing process of Heaven and Earth.”10 The Han thinkers, especially Dong Zhongshu (195?–105? B.C.E.), established the philosophical and political basis for State Confucianism that was invoked by later dynasties for their own ideological ends. Confucianism was, however, somewhat eclipsed by the spread of Buddhism during the Six Dynasties (222–589), Sui (589–618), and Tang (618–960) periods.

Confucianism was revitalized in the eleventh and twelfth centuries during the Song dynasty largely by the ideas of Zhou Dunyi (1017–1073), Zhang Zai (1020–1077), Cheng Hao (1032–1085), Cheng Yi (1033–1107), and Zhu Xi (1130–1200). It was Zhu’s synthesis of these thinkers and his codification of texts into the Four Books that became known as Neo-Confucianism. The Four Books, which he felt contained the central ideas of Confucian thought, are the Analects, Mencius, and two chapters of the Record of Rites: the Great Learning and the Doctrine of the Mean. These texts and Zhu’s commentaries on them became the basis for the civil service examination system that endured in China for some six hundred years. With this system, government officials were selected for office on the basis of Confucian moral education. Confucianism thus became the foundation for a meritocracy in contrast to the achievement of office by privilege, rank, or birth.

Zhu’s Reflections on Things at Hand is a central Neo-Confucian text. This anthology of Song Neo-Confucian thought is considered to be “unquestionably the most important single work of philosophy produced in the Far East during the second millennium a.d.”11 Zhu himself describes the work in the following manner: “The Four Books are the ladders to the Six Classics, the Jinsilu is the ladder to the Four Books.”12

In this work, Zhu compiled texts that provided, for the first time, a comprehensive metaphysical basis for Confucian thought and practice. In response to the Buddhists’ metaphysics of emptiness and their perceived tendency toward withdrawal from the world in meditative practices, Zhu formulated a spirituality based on a balance of religious reverence, ethical practice, scholarly investigation, and political participation. The disillusionment caused by the failure of political reforms in the Northern Song dynasty led Zhu Xi to advocate the moral and spiritual education of individuals in order to affect the larger social and political order. He outlined a program of study that was broadly and practically based and yet had a deep regard for the unique moral and spiritual cultivation of each person. To investigate things without and to have reverence within were the two complements of his thought.

Unlike the Buddhists, who saw human ignorance of the impermanent nature of the world as a source of suffering, Zhu Xi, and the Neo-Confucians after him, affirmed change as the source of transformation in both the cosmos and the person. Thus Neo-Confucian spiritual discipline involved cultivating one’s moral nature so as to bring it into harmony with the larger pattern of change in the cosmos. Moral virtues were often paired with a cosmological counterpart; the central virtue of humaneness (C. ren, J. jin), for example, was seen as the source of fecundity and growth in both the individual and the cosmos (C. yuan, J. gen). By practicing humaneness, one could effect the transformation of things in oneself, in society, and in the cosmos. In so doing, one realized a deeper identity with reality, characterized as “forming one body with all things” (C. wan wu yi ti, J. banbutsu ittai). This process of cultivation involved disciplining one’s mind and heart, which is represented by a single character in Chinese (shin) and Japanese (kokoro). Thus the mental and emotional dimensions of humans are intertwined and are translated here as mind-and-heart.

Confucian thought, political institutions, social organization, and educational curricula had a profound influence on China, Korea, and Vietnam. Chinese influence in Vietnam, felt as early as the Han dynasty, was long lasting; indeed, northern Vietnam was a part of the Chinese empire for a millennium (111 B.C.E.–993 C.E.). Confucian thought passed into Korea beginning in the third and fourth centuries, and into Japan in the sixth and seventh centuries; it has had a lasting impact on the social, political, and educational systems of both countries. As in China, in Korea, too, Zhu Xi’s commentaries on the Four Books became the foundation for the civil service examination system. This system of selecting government officials on the basis of merit rather than hereditary privilege lasted in China and Korea until the early twentieth century. In Japan, although there were no civil service examinations, the Four Books and Zhu’s commentaries became the basis of the samurai educational curriculum in the premodern period. These texts were particularly important during the Tokugawa period, when Confucianism spread through schools and through the writings and lectures of individual scholars such as Ekken.

Zhu Xi’s influence on East Asian thought and education has clearly been significant and enduring. In this context, a work such as Ekken’s Record of Great Doubts takes on particular importance. Ekken provided the Japanese not only with the first accessible commentary on Zhu Xi’s Reflections on Things at Hand but also with one of the first fully developed disagreements with Zhu. Thus both affirmation and dissent are represented in Ekken’s work as he developed his own articulation of the philosophy of material force.

Wing-tsit Chan has translated qi as “material force,” something that consists of both matter and energy.13 Chan notes that before the notion of li developed in the Neo-Confucian tradition, qi referred to the “psychophysiological power associated with blood and breath.”14 He also suggests that the words “matter” or “ether” are not adequate translations for qi because they convey only one aspect of the term.15

One of the earliest appearances of the term qi in the classical period is in the writings of Mencius, who refers to qi as “that which fills the body.”16 In this context, qi can be translated as “vital force” or “vital power.”17 Mencius notes that the qi that fills one’s body is directed by the will. He observes that it is important not to abuse or block one’s qi but to allow it to flow freely. If one does this and nourishes one’s qi, it will fill the space between Heaven and Earth. A famous reference in Mencius speaks of a “flood-like qi,” sometimes translated as a “strong, moving power.”18 Mencius says that this floodlike qi is difficult to explain. He comments, nonetheless, on the importance of nourishing it, for, he says, that qi is,

in the highest degree, vast and unyielding. Nourish it with integrity and place no obstacle in its path and it will fill the space between Heaven and Earth. It is a qi which unites rightness and the Way. Deprive it of these and it will collapse. It is born of accumulated rightness and cannot be appropriated by anyone through a sporadic show of rightness. Whenever one acts in a way that falls below the standard set in one’s heart, it will collapse.19

It is clear that this psychophysical energy must be cultivated carefully, for it is what links us to all other living things. In other words, in humans qi is a special form of material energy that can be nurtured through self-cultivation, which contributes to our moral and physical well-being and provides a basis for respecting other humans. The whole universe is, likewise, filled with the matter-energy of qi. By nourishing not only our own qi but also the consciousness of our connection to this energy in nature we become full participants in the dynamic, transformative processes of the universe. That is because qi is the underlying unity of life, simultaneously moral and physical, spiritual and material. These ideas are further developed by Zhang Zai, Zhu Xi, and Luo Qinshun in China and such other Neo-Confucians as Yi Yulgok in Korea and Kaibara Ekken in Japan.

Zhang Zai’s Development of the Concept of Material Force

Zhang Zai’s (1020–1077) great contribution to Neo-Confucian thought was his elaboration of qi as the vital material force that runs throughout creation. Qi is in a constant process of transformation that is self-generating. This change, however, is not simply random, illusory, or purposeless. Underlying the dynamic movement of qi is the pattern of the alternation of yin and yang. Thus all change, he asserts, occurs by means of principles (li). These principles or patterns of change are not simply repetitious or static entities. Each event, thing, or person is unique and hence of moral value in the continually unfolding process of qi: “In what has been created through stages of formation and transformation, no single thing (in the universe) is exactly like another.”20 The constantly changing quality of qi, then, is its dynamic force, which reveals both pattern and uniqueness as inherent in the universe.

Zhang Zai took an important step for Neo-Confucian metaphysics when he identified qi with the void, or the Great Vacuity (taixu). The distinguished twentieth-century Neo-Confucian scholar Tang Junyi (1909–1978) saw this as an attempt to synthesize the notion of qi as understood by the scholars of the Jin and the Han with the emptiness of the Daoists and the Buddhists.21 This synthesis contains two significant aspects, which Tang characterized as the vertical aspect and the horizontal aspect. In its vertical aspect, Zhang essentially provided a basis for asserting the unity of being and nonbeing, thus challenging the Buddhist and Daoist positions, which gave priority to emptiness and nonbeing respectively. In its horizontal aspect, Zhang provided a metaphysical explanation for intercommunion and change in the phenomenal world by means of the voidness of qi. Both the vertical and horizontal dimensions laid the groundwork for Zhang’s theory of mind as having a cosmic basis. Essentially he aimed to show the intrinsic connection between the human mind and the cosmic order by means of a shared qi. Thus humans have the potential for understanding the underlying unity of qi behind all forms of change. Furthermore, humans have the capacity for intersubjective empathy with all of creation through comprehending the constant fusion and diffusion of qi. Zhang set forth these ideas in the Western Inscription (Ximing), where he indicates metaphorically that humans are the children of Heaven and Earth.

The Vertical Aspect of Zhang Zai’s Synthesis: Metaphysical Position

In developing the concept of qi, Zhang Zai, like other Confucians before him, drew on the Classic of Changes as one of his chief sources of inspiration. His cosmology is distinctive, however, in that he identifies qi with the unity of all life. He describes the two aspects of qi as its substance (ti) and its function (yong). As substance it is known as the Great Vacuity, the primal undifferentiated material force, while as function it is the Great Harmony (taihe), the continuous process of integration and disintegration. The significance of differentiating these dual aspects of qi is its affirmation of the underlying unity of being and nonbeing, of the seen and the unseen. Thus both inner spirit and external transformation are understood as part of a whole, which is the constant appearance and disappearance of qi. Comprehending this reality brings one to “penetrate the secret of change,”22 the understanding that material force is never destroyed, only transformed. While the forms of things are constantly changing, there is nonetheless a “constant unity of being and nonbeing.”23

The significance of Zhang’s metaphysical position is that it provided a comprehensive explanation of change that could then be related to the process of spiritual growth and cultivation in human beings. Change is affirmed as purposive and humans are called upon to identify with change and participate in the transformation of things.

Zhang Zai emphasizes his position in contrast to the Daoist belief that being arises from nonbeing and in contrast to the Buddhist tendency to emphasize the illusory quality of reality. He wanted neither to transcend change, as he suggested Buddhists aimed to do in meditation, nor to prolong life, as the Daoists tried to do with elixirs and practices to nurture the body.24 Instead, he affirms the phenomenal world as a manifestation of qi. Moreover, he does not see non-being as a void into which phenomena disappear and are annihilated. Rather, he sees it in more positive terms as the source not only of life but also of generation and transformation; material force transforms through “fusion and intermingling.”25 He writes that “the integration and disintegration of material force is to the Great Vacuity as the freezing and melting of ice is to water. If we realize that the Great Vacuity is identical with material force, we know that there is no such thing as non-being.”26 Thus the Great Vacuity is the unmanifested aspect of the creativity and fecundity of the universe. The Great Harmony is its manifested aspect. They are not two separate things.

Ultimately Zhang Zai’s identification of qi with the Great Vacuity intended to overcome any duality between that which produces and that which is produced, between substance and function. “If one says that the Great Vacuity can produce qi (i.e., is itself distinct from qi) then,” he writes, “this means that the Void is infinite whereas qi is finite, and that the noumenal (ti) is distinct from the phenomenal (yong). This leads … to … failure to understand the constant principle of unity between being and non-being.”27 Apprehension of this essential unity is what Tang Junyi calls the vertical aspect of Zhang Zai’s identification of qi with the void.

The Horizontal Aspect of Zhang Zai’s Synthesis: Ethical Implications

The horizontal aspect, according to Tang, is the voidness of qi itself, which accounts for the constant intercourse and, hence, generation of things. Transformation depends on the interpenetration and “mutual prehension”28 of things. They could not occur unless the qi of all things was empty, for the emptiness becomes the matrix of intersubjectivity. Thus things and persons can become uniquely present to one another through the mutual resonance of the voidness of qi. As Tang writes, “whenever a thing is in intercourse with another it is always that the thing by means of its void contains the other and prehends it.”29 Spatiality or emptiness is the means by which communion occurs and hence change becomes possible. Generation and transformation arise because through the void things can “diffuse their ether (qi) and extend themselves to other objects.”30 This fusion and diffusion of qi is expressed by Zhang Zai as extension (shen) and transformation (hua). Through these two principles of change, material force has the power both to produce and to be produced. Creativity and communion are possible, then, by the very nature of material force itself.

The whole universe can be seen as in a process of generation and evolution, which are themselves regarded as positive qualities exhibiting moral characteristics.31 Zhang expresses this as follows:

Spirituality or extension is the virtue of Heaven

Transformation is the way of Heaven

Its virtue is its substance, its way its function

Both become one in the ether (qi).32

In an analogous manner, humans have a moral nature that is exhibited in the virtues of rightness and humaneness. Rightness in humans corresponds to transformation and differentiation in the natural order, for it brings things to completion. Similarly, humaneness corresponds to generation and extension, for it means sharing the same feeling. The fecundity of the cosmological order has its counterpart in the activation of virtue in the human order. Central to Zhang Zai’s cosmology is his assertion that the task of the human is to understand and identify with the transformation of things, which he sees as essentially a spiritual process. He writes, “All molds and forms are but dregs of this spiritual transformation.”33 The person who knows the principles of transformation will be able to “forward the undertakings of Heaven and Earth.”34 His comprehensive affirmation of the role of the human in the universe can be seen in the Western Inscription, where he identifies the human with the whole cosmic order:

Heaven is my father, Earth is my mother and even such a small creature as I finds an intimate place in their midst.

Therefore, that which fills the universe I regard as my body and that which directs the universe I consider as my nature.

All people are my brothers and sisters, and all things are my companions….

In life I follow and serve [Heaven and Earth]. In death I will be at peace.35

Zhang Zai’s ethical, “mystical humanism”36 is the necessary corollary to his understanding of the dynamics of change in the physical order. He sees the same process of fusion and intermingling as acting in the human through the operation of humaneness. Change holds a great creative potential for growth and fulfillment. Yet he realizes that there is also a mystery of interaction that is impossible to grasp fully: “This is the wonder that lies in all things.”37

For Zhang, the key to harmonizing human nature and the way of Heaven is the practice of sincerity. Sincerity and enlightenment are the two aspects of spiritual practice, of the cultivation of one’s nature and the investigation of things. In this balancing of inner and outer wisdom, Zhang distinguishes between nature and destiny, saying that nature is endowed by Heaven and is not obscured by material force. Destiny he defines as what is decreed by Heaven and permeates one’s nature. One of the goals of achieving sagehood is to develop one’s nature and thus fulfill one’s destiny. In this way, a person can form one body with all things.

The significance of these distinctions in Zhang Zai’ s thought is that he maintains (in the tradition of Mencius) that human nature is originally good. To account for evil he does, however, posit two natures, an original one and a physical one. This is something Ekken did not embrace, although he follows Zhang’s larger understanding of a monism of qi. Evil arises because of imbalances in our physical nature that, in turn, result from the mingling of our physical nature with qi. Material force emerges from its undifferentiated state in the Great Vacuity, and differentiation arises in its phenomenal appearances. Because of this inevitable process, conflict and opposition are bound to arise and hence also evil. He recognizes that physical nature, while not evil in itself, has the potential for giving rise to evil in human actions. It is possible, however, to recover one’s original nature through moral cultivation. Indeed, one can overcome any incipient tendencies toward evil by enlarging one’s mind to embrace all things through intensive study. Zhang Zai notes that “the great benefit of learning is to enable oneself to transform his own physical nature.”38 Zhang also observes that the mind can harmonize human nature and feelings. This doctrine of the mind, however, is left for later Neo-Confucians to develop more fully.

In summary, Zhang Zai’s doctrine of the Great Vacuity provides a metaphysical basis by which to explain the unity and the constant interaction and penetration of things. It also gives an ethical grounding for understanding the interactions among people. The agency of both the fecundity of the natural order and the activation of virtue in the human order in effecting change and transformation can be understood as possible because of spatiality and emptiness. As Wing-tsit Chan has pointed out, it is precisely this condition that allows all things to realize their authenticity and full being. For “only when reality is a vacuity can the material force operate and only with the operation of the material force can things mutually influence, mutually penetrate and mutually be identified.”39 Identification and communion of humans with nature and with each other is possible because of the emptiness of qi.

With these carefully articulated metaphysical and ethical discussions, Zhang Zai was the first Neo-Confucian who also argued for the essential unity of principle and material force. This unified view was central to the monism or philosophy of qi of Luo Qinshun in Ming China, Yi Yulgok in Yi Korea, and Kaibara Ekken in Tokugawa Japan.

The Influence of the Monism of Qi of Luo Qinshun

In addition to the influence of Zhang Zai’s unified cosmology, Ekken is indebted to the Ming Confucian Luo Qinshun (1465–1547), who initially articulated his disagreements with Zhu’s qualified dualism in his important text Knowledge Painfully Acquired (Kunzhiji).40 First published in China in 1528, it was republished more than ten times in the Ming and Qing periods. It was reprinted in Korea and from there was brought to Japan after the Japanese expeditions to Korea in the 1590s. Hayashi Razan (1583–1657) was said to have read it and made a copy before 1604. A Japanese woodblock edition was issued in 1658 and read shortly afterward by Ekken, Itō Jinsai (1627–1705), Andō Seian (1622–1701), and others.41 Similarly, in Korea, with the thought of Yi Yulgok (1536–1584), there arose another formulation of the disagreements with Zhu.42 These thinkers, Luo, Yi, and Ekken, are the central figures in what has been termed a monism or philosophy of qi school of thought in East Asian Neo-Confucianism. Each wished to preserve monism over dualism with shared concerns for the relationship between cosmological perspectives and views of self-cultivation.43

In his work of remarkable scholarship and careful thought, Luo, following Zhang Zai, lays out his argument for the importance of qi as the unitary basis of reality and as the source of changes in the natural world. He argues forcefully against Zhu Xi’s qualified dualism of li and qi and for the importance of the vital material force in the world. He wished to avoid either a potential transcendentalism of the Zhu Xi school of Neo-Confucianism or a subjective idealism of the Chan school of Buddhism or the Wang Yangming school of Neo-Confucianism. Instead, he emphasized viewing the world of humans as part of a single unified reality of qi. Acquiring knowledge of this world and of the human mind was part of the moral cultivation of the individual. Luo, like Zhang Zai, thus hoped to preserve both unity and diversity and to establish a metaphysics whereby the natural world and the human mind are identified yet distinct. These are surely perennial problems in philosophy, and the subtle deliberations of Luo had a powerful influence in the evolution of Neo-Confucian thought in China, and they also affected the development of both Korean and Japanese Neo-Confucianism. The implications for metaphysics, ethics, epistemology, and empiricism were significant, especially for promoting practical learning.

Metaphysics: Monism of Qi

In seeking to explain the evolution of the universe and its constant change over time, Luo speaks, in language that echoes Zhang Zai, of the unitary force of qi:

That which penetrates heaven and earth and connects past and present is nothing other than material force (qi), which is unitary. This material force, while originally one, revolves through endless cycles of movement and tranquility, going and coming, opening and closing, rising and falling. Having become increasingly obscure, it then becomes manifest; having become manifest, it once again reverts to obscurity. It produces the warmth and coolness and the cold and heat of the four seasons, the birth, growth, gathering in, and storing of all living things, the constant moral relations of the people’s daily life, the victory and defeat, gain and loss in human affairs.44

This qi has its manifestations in the seasons and in natural growth, as well as in moral relations in human life. Yet Luo insists that within this transformation and variety “there is a detailed order and an elaborate coherence which cannot ultimately be disturbed.”45 This order is principle and is, moreover, not separate from material force. Luo states repeatedly that li and qi are not different things. Indeed, he notes that he seeks a means to reconcile and recover the ultimate unity of li and qi. 46

Material force operates throughout the universe in a process of continual disintegration and integration, like the waxing and waning of yin and yang. Relying on Zhang Zai’s text Correcting Youthful Ignorance (Zhengmeng), Luo describes this process:

In its disintegrated state, qi is scattered and diffuse. Through integration, it forms matter, thereby giving rise to the manifold diversity of men and things. Yin and yang follow one another in endless succession, thereby establishing the great norms of heaven and earth.47

In another passage, Luo acknowledges the subtlety of the kind of distinctions he is trying to make in the relationship of li and qi:

Li must be identified as an aspect of qi, and yet to identify qi with li would be incorrect. The distinction between the two is very slight, and hence it is extremely difficult to explain. Rather we must perceive it within ourselves and comprehend it in silence.48

Ethics: One Nature in Humans

The implications of Luo’s monism is that he does not accept the distinction of two natures in humans, the original nature and physical nature posited by Zhang Zai and other Song Neo-Confucians as a means of explaining the origin of evil.

Luo maintains that in the classical Confucian tradition human nature is one. He believes that “human beings are fundamentally alike at birth in sharing the unitary qi and the compassionate mind.”49 Humans are united to all living things by virtue of their qi: “The qi involved in human breathing is the qi of the universe. Viewed from the standpoint of physical form, it is as if there were the distinction of interior and exterior, but this is actually only the coming and going of this unitary qi. Master Cheng said, ‘Heaven (or nature) and man are basically not two. There is no need to speak of combining them.’ This is also the case with li and qi.”50 He accounts for diversity by reference to Cheng Yi’s phrase “Principle is one, its particularizations are diverse.”51 Luo observes: “At the inception of life when they are first endowed with qi, the principle of human beings and things is just one. After having attained physical form, their particularizations are diverse.”52 Along with a rejection of a dualism of an original nature and a physical nature comes a denial of an antagonism between the principles of nature and human desires. Thus human emotions and desires are affirmed as valid parts of human nature and deserving of being cultivated and expressed appropriately.

Epistemology and Empiricism: Investigating Things

In terms of knowledge, Luo’s emphasis on qi gives rise to his strong affirmation of the importance of sense knowledge and experience. He does not see this sort of knowledge as less valid than the kind of moral knowledge derived from texts or history. He thus affirms the necessity of “investigating things” (gewu) and examining principles in the world as a means of acquiring knowledge. Although the idea of investigating things originated with classical Confucians in the Great Learning, it became a central doctrine of the school of Neo-Confucians inspired by the Cheng brothers and Zhu Xi. With Luo, however, the foundation for the extension of Confucianism into an empirical area is clearly laid, and it is precisely what happened in the thought of Kaibara Ekken in seventeenth-century Japan with his profound interest in studying the natural world.

All these ideas were adopted and adapted by Ekken in the Record of Great Doubts. His desire to affirm the world in its dynamic process of material force, in the feeling aspects of human nature, in the appreciation of the fecundity of the natural world, and in the investigation of things, both human and natural, was essential to Ekken’s thought. His philosophy of the monism of qi expressed in this work formed the basis of his writings for both specialists and a broader public on Neo-Confucian ideas of cosmology and of his varied studies in aspects of practical learning—ranging from geography and history to astronomy, medicine, and mathematics.

Affirmation and Dissent: The Significance of the Record of Great Doubts

Like Luo Qinshun, Ekken was “a dedicated follower and a constructive critic” of Zhu Xi.53 Ekken proposed to question respectfully yet creatively some of the principal metaphysical ideas of Zhu Xi. In so doing, he opened up the margins of dissent and called for critical reevaluation within the Neo-Confucian tradition. The Record of Great Doubts demonstrates the complex processes of continuity and change, adoption, and adaptation that are vital parts of an ongoing humanistic tradition such as Neo-Confucianism. As On-cho Ng and Kai-wing Chow have observed: “Both the texts and doctrines of any vital cultural tradition, such as Confucianism, are always in the midst of transformation, drift, and rupture, in medias res, relocated and remapped in ongoing interpretations and publications.”54 Indeed, by reconfiguring the idea of qi, this text illustrates that Neo-Confucianism was far from being simply a static orthodoxy passively accepted in various parts of East Asia. Rather, in a figure like Ekken and in a work such as the Record of Great Doubts, the intricate adaptation of a tradition through affirmation and dissent can be perceived. The text also demonstrates the painstaking efforts of Confucians to distinguish their concerns and commitments from those of the Buddhists and Daoists. They aimed above all, as Ekken makes abundantly clear, to claim involvement in—not withdrawal from—the world as a primary value.

Ekken’s treatise is significant in the context of the Neo-Confucian tradition in East Asia for a number of historical, methodological, philosophical, and religious reasons.

1. Historically the text demonstrates the appeal and affirmation of Neo-Confucian ideas across cultures in East Asia. In particular, it documents the transmission and adaptation of distinctive forms of Chinese Neo-Confucianism to Japan: the monism of qi of Zhang Zai in the Song and Luo Qinshun in the Ming.

2. Methodologically it exemplifies the careful style of questioning and dissenting that was possible in the Neo-Confucian tradition of “learning for oneself” (Analects 14:25) rather than to impress others. Indeed, it affirms the importance of doubt as a method of individual inquiry for the attainment of authentic personhood and for the critical appropriation of a tradition.

3. Philosophically it argues against a separation of principle (li) and material force (qi) in favor of a monism of qi. Ekken suggests that the vitalistic naturalism of qi is preferable to the transcendental rationalism of li because the latter may result in quietism or withdrawal from the world. Affirmation of the world and investigation of it is indispensable to Ekken’s thought.

4. Religiously it affirms the cosmological context of naturalism as a basis for Ekken’s position that an individual must be in harmony with the vital material force in the universe so as to participate in the moral transformation of self and society. Thus affirming the world requires active participation in it.

The Text in the Context of Tokugawa Japan

Ekken lived during the early Tokugawa period, when Japan was emerging from the tumultuous wars and internal disruptions of the late medieval era. With the unification of Japan under the first Tokugawa shogun, Ieyasu, a new capital was established at Edo by the shogun-led government, or bakufu. The political and economic power of the government was solidified by Ieyasu’s successors through a variety of means. Most significant were the measures taken to close the country (sakoku) and to attempt to control the provincial rulers (daimyo).

Observing the political and missionary encroachments of the Spanish and Portuguese in Asia in the sixteenth century, the Tokugawa bakufu was wary of any possible foreign interference with their power. They therefore took strong measures to prevent foreigners from entering or Japanese from leaving the country. Even Japanese who were overseas were prohibited from returning to Japan. This sealing off of the borders through the sakoku edicts was effective in many respects. In particular, it resulted in the suppression of Christianity and the eventual end of Japan’s “Christian century,” which had begun with European missionaries such as Francis Xavier, who arrived in Japan in 1549.55 It did not, however, prevent books and other materials from entering Japan through the agency of the Dutch traders who were allowed to remain on the island of Deshima in Nagasaki harbor. Moreover, as Ronald Toby, Bob Wakabayashi, and other scholars have noted, trade with various parts of Asia was not fully suppressed.56 Thus while Japan was closed to a foreign presence on its soil, it was not completely isolated from Chinese books and Western ideas, especially through what was known as Dutch learning.57 Ekken himself frequently went to Nagaski to purchase books and was thus exposed to both Chinese Neo-Confucian texts and certain Western scientific texts.

The other principal means of bakufu control was through the political and economic administration known as the bakuhan system. It consisted of maintaining a seemingly delicate balance between regional autonomy (han) and centralized autocracy (bakufu). A hierarchy of political power was maintained, with the emperor in Kyoto symbolically at the apex. The shogun in Edo paid his respects to the emperor and so derived his authority from the emperor. In turn, the daimyo of each province were obligated to demonstrate their allegiance to the bakufu in various ways. The power of the daimyo was regulated through taxation, land distribution, and fealty obligations. Most prominent among these obligations was the system of alternate attendance in Edo known as sankin kōtai. The daimyo were required to travel with a large retinue to Edo every other year. There they had to maintain a residence where their wife and children lived. The cost of the travel and the residence prevented the daimyo from becoming an economic threat to the bakufu. Moreover, their political activities could be more closely observed by their presence in the capital. By these means, the bakufu maintained a strong centralized bureaucratic control in Edo.

Ekken was the beneficiary of this bakuhan system in various ways, primarily because it was a period of political stability after decades of warfare. He was employed for many years as an adviser to the local daimyo in Fukuoka. With this patronage came the opportunity to study in Kyoto and to travel with the han retinue to Edo on numerous occasions. Although the han asked him to do several lengthy genealogies and local histories, he also had financial support from the han to pursue his own interests in practical learning and in Confucian scholarship. Indeed, the benefits of his studies were felt by various classes of people in his own province and beyond.

The consequences of this time of peaceful consolidation extended also into the spheres of economics and education and encouraged the spread of Confucianism. With the decline of the samurai as a warring class, there was a need for other employment. Many of these samurai became bureaucrats or advisers to the government in Edo or in their respective provinces. Others became teachers, scholars, or tutors in the newly forming educational system under the aegis of Confucian philosophy.58 Although there was not a civil service examination system in Japan, as there had been in China and Korea, a new kind of literati class (jusha) began to emerge. The Confucian virtue of meritocracy was especially valued by this literati class as its members became leading educators and political advisers. Moreover, the moral philosophy, political theory, and practical learning of Confucianism appealed to the samurai as well as to those of other classes.

The rising intellectual influence of the samurai was somewhat offset by the growing economic power of merchants. Trade flourished along the Tōkaidō road to Edo. Osaka, in particular, became a center of bustling economic activity. Confucianism was invoked also by the merchants to articulate the educational philosophy of their Osaka academy, known as the Kaitokudō. 59 Even the farmers benefited, from the publication of agricultural manuals stimulated by the practical learning concerns of Confucian scholars such as Ekken.

The Spread of Confucian Ideas and Values

The relative peace and growing prosperity of the early Tokugawa period were ideal conditions for the gradual spread of Confucianism to many strata of the closed society. The reasons for this growth are manifold and deserving of further exploration. At a minimum, however, it is worth noting that not least of these reasons was the inherent appeal of Confucianism itself.60 With Ekken this appeal is evident in his ardent embrace of Confucian moral thought and in his drive to spread Confucian ideas to diverse classes of society. Through his work and that of others, Confucian values were disseminated through various levels of society. This dissemination was made possible by the rapid growth of inexpensive printing methods and the increased literacy due to the establishment of schools. Tetsuo Najita has described the diffusion of Confucianism in Tokugawa Japan:

The importance of Confucianism as a source from which key mediating concepts were drawn to grapple with specific moral issues confronting Tokugawa commoners is easily confirmed by the available literature of the period. In the case of merchants, Confucianism offered a language with which to conceptualize their intellectual worth in terms of universalistic definitions of “virtue.” Thus while Confucianism undeniably remained the preferred philosophy of the aristocracy, to view it as being enclosed within the boundaries of that class would be to deny that system of thought its adaptive and expansive abilities.61

In this spread of Confucianism, distinctive schools of thought began to develop in Japan as lively philosophical debate emerged among scholars. The leaders of these schools of thought included those who were most indebted to the Song Neo-Confucian scholar Zhu Xi (such as Yamazaki Ansai and Hayashi Razan), others who were more attracted to the Ming Neo-Confucian Wang Yangming (such as Nakae Tōju and Kumazawa Banzan),62 and still others who felt it was important to return to the early Confucian tradition of Confucius and Mencius (such as Itō Jinsai and Ogyū Sorai).63 Numerous philosophical issues divided these schools, but a principal area of debate in Japan was the adaptability of Confucianism to a different cultural and intellectual milieu. The process of accommodating Confucianism to the Japanese context has been termed the naturalization of Confucianism.64 It involved intricate and at times tortuous discussions of which aspects of Confucianism were appropriate to particular times, places, and circumstances in Japan. For certain thinkers it brought into focus ways in which Confucianism and Shinto could be compared, identified, or syncretized so as to indigenize Confucian ideas by means of the native tradition. As Najita has observed, for many of these scholars this process of adaptation was a means of giving a language and a vocabulary to an indigenous ethical system: Shinto.65

This process of adapting and adopting Confucian philosophy and practice was for Ekken a central concern. He attempted to address the issue on a number of levels, including showing the compatibility of Confucianism and Shinto and popularizing Confucian moral teachings among various classes in society. The issue of selectively adopting another philosophical tradition is a main concern in the Record of Great Doubts.

What is striking about Ekken’s process of selectively adopting from the Chinese Neo-Confucian tradition is his long reflection on various aspects of Zhu Xi’s thought and his reluctance to appear to break radically with him. Sometime after the age of thirty-five, Ekken became more fully convinced of the correctness of Zhu’s ideas. Before that, he had read widely in the texts of Lu Xiangshan, Wang Yangming, and their followers. His turn from the Lu-Wang school to the Cheng-Zhu school occurred after his discovery of the General Critique of Obscurations of Learning (Xue bu tong bian) by Chen Jian (1497–1567). Chen’s sharp critique of the Lu-Wang school as being too Buddhistic and subject to excesses helped to shape Ekken’s allegiance to Zhu Xi. It also heightened his awareness of purported Buddhist influences on Zhu and the other Neo-Confucians. Nonetheless, to promote Zhu’s thought Ekken compiled selections of his most critical passages and punctuated them so they could be read in Japanese. These were published in A Selection of Zhu Xi’s Writing (Shushi bunpan) when Ekken was thirty-eight. Yet even from this time Ekken’s doubts were evident, for it was this same year that he wrote Notes on Reflections on Things at Hand, in which he cited passages from Xue Xuan disagreeing with Zhu’s understanding of principle and material force.66 Ekken’s doubts regarding Zhu’s ideas became more pronounced in his late forties, and by the time he was fifty-six they appeared to be irresolvable.67

It is interesting to note, however, that he did not publish the Record of Great Doubts during his lifetime. The reasons for this may never be fully understood, but at a minimum it appears to reflect his concern that he would be identified with the Ancient Learning (kogaku) scholars, especially Itō Jinsai, who had adopted a position regarding qi close to his own. In their search for a pure form of Confucianism, the Ancient Learning scholars sought to return to the classical texts of Confucianism, especially Confucius and Mencius, and to bypass the later Neo-Confucian thinkers. Ekken seemed to feel that Jinsai was too critical of Zhu Xi, and he did not want to appear to be dismissive of Zhu’s thought, as Jinsai was in his return to the early Confucian classics. Okada Takehiko has suggested, moreover, that Ekken felt a debt of gratitude to the Song Confucians because of their affirmation of the importance of a deep love of nature.68 So much of Ekken’s practical learning arose from his feeling for the complexity and beauty of nature. Accordingly, Ekken’s gratitude to the Song Confucians, and to Zhu Xi in particular, is expressed with great deference. He strongly criticized the Ming Confucians, who seemed to Ekken to be arrogant and flippant in their disagreements with Zhu. Ekken chose as due respect for Zhu’s teachings neither such disregard nor a blind loyalty but an appropriate and thoughtful disagreement with them.

Consequently, Ekken was reluctant to have the Record of Great Doubts published lest he be misunderstood as rejecting Zhu Xi. Even his followers were hesitant to publish the text after his death because they understood his concern that his thought could be dismissed as heretical. Not until half a century later was it finally published, by Ono Hokkai, one of Ogyū Sorai’s disciples. The work was praised by Sorai when he first read it several years after Ekken’s death: “It gives me great pleasure to find that there is a scholar in a faraway place who has anticipated my own thoughts.”69 Mori Rantaku, a disciple of Dazai Shundai, also praised the Record of Great Doubts: “The one volume of the Taigiroku is superlative, a comprehensive treatise which is the result of extensive scholarship and deep dedication…. This book alone sufficiently displays Ekken’s greatness as a master. It is an ever-shining beacon of scholarship.”70

It would seem, then, according to Okada Takehiko and others, that although the Record of Great Doubts was greatly appreciated by later scholars, Ekken’s concern was he might be seen as too closely aligned with Jinsai’s more radical critique and as having abandoned Zhu Xi. His disagreement with some of Zhu Xi’s ideas left undiminished his profound debt to Zhu’s synthesis of Song Neo-Confucianism, and Okada has thus called him a reformed Zhu Xi scholar.71

One of Ekken’s underlying intentions was to identify the lingering traces of Buddhist and Daoist influences in Zhu’s thought that seemed to him to tend toward emptiness and a lack of involvement in worldly affairs. In highlighting these influences, he hoped to maintain the important connection between cosmology and self-cultivation; his primary concern was that one’s metaphysics should affect one’s ethical stance in the world. Ideas and action, theory and practice were deeply intertwined. He made a valiant, though at times tortuous, effort to identify systematically what he felt was problematic in Zhu’s metaphysics and ethics. This required, however, carefully defining the grounds for disagreement within a tradition. Setting the parameters of dissent between skepticism and blind acceptance was a major contribution of the Record of Great Doubts.

Tradition and the Individual: The Importance of Dissent and the Centrality of Learning

In religion, philosophy, and social thought, doubt and dissent have always had a crucial role, for ideas are rarely passed on without reflection and debate. In the West, from the early Greek skeptics to contemporary deconstructionists and postcolonialists, elements of dissent have continued to percolate and provoke. Similarly in Asia, from the Buddhist sense of great doubt in the Chan tradition to the skepticism and paradox of the Daoists and the intellectual questioning and investigations of the Confucians, doubt has been an ongoing preoccupation. This role of doubt serves to remind us of the constant elusiveness of truth and the volatility of traditions. It also underscores the creativity of individuals and the vitality of thought traditions that are open to discussion and dissent. The delicate balancing of individual doubt with the burden of the past is at the heart of the struggle of traditions over time and across cultures. Indeed, identifying the complex dynamics of change and continuity within a tradition is a major challenge for philosophers, theologians, and historians.

When a significant intellectual debate emerges in a tradition, it not only illuminates the tensions within and pressures from without, but also testifies to the vitality and flexibility of the tradition for the adherents themselves. Lines of doubt and argumentation cast light on the strands of continuity and change:

When there is a prolonged and general loyalty to any complex philosophy, philosophical discourse tends to take on the character of fine-grained, exacting analysis and argumentation known as “scholasticism.” This is a treasure for those interested in discovering the dynamic tensions and stresses that reveal the structural seams of a complex philosophical synthesis. As the fine grain emerges in a piece of wood through long polishing, so too does scholastic polishing inevitably bring out the fine grain of the system. And it is the controversies that resist solution that are most of interest; if there is some point that can engage fine minds on both sides for decades or even centuries, it likely indicates a deeper strain, conflict or tension in the very structure of the system itself.72

Examples of such creative tension are the different but complementary emphases of the Cheng-Zhu and Lu-Wang schools in China, the Four-Seven debate (on the Four Beginnings and the Seven Feelings) in Korea,73 and the arguments regarding the relationship between principle and material force that characterize Neo-Confucian thought throughout East Asia. As we have seen, this debate regarding principle and material force was important in the work of Luo Qinshun in China, Yi Yulgok in Korea, and Kaibara Ekken in Japan.

For Ekken, this balancing of individual doubt and a tradition’s lineage was a monumental preoccupation engaging many decades of his life. He did not want to subvert the transmission of the tradition or to undermine the contribution of his intellectual forebears. Rather, he hoped to enrich and enliven the multiple interpretations and implications of Confucian thought, especially that of Zhu Xi. Ekken’s intellectual struggles cause us to reevaluate the conventional notion that Confucianism was a tradition transmitted routinely without disagreement or individual reflection. Moreover, it adds complexity to the various divisions of orthodox and heterodox teachings in Confucianism by suggesting that the dividing lines were not clearly drawn and that criteria for categorization were subject to continual contestation and reevaluation. In short, the subtlety of the means and methods of dissent in a figure like Ekken demand a more careful reflection on issues of intellectual lineage and transmission as well as creativity and change within a tradition like Confucianism. Such reflection requires us to focus again on the role of learning for Confucians.

Because learning is central to the Confucian tradition, the content and method of learning were frequently the source of discussion and debate. As the Confucians created a sense of correct historical lineage of the passage of the Dao, as they established schools or encouraged study in the family, as they fostered civil service examinations or promoted government service, some of the key questions and concerns surrounded the topic of learning.74

Within these discussions there arose a creative tension between learning as a communal legacy and learning as individually liberating. In other words, the dialectic between the tradition and the individual was a source of constant interplay and reflection. The changes and continuities in the tradition can be traced to the manifold debates on the centrality of learning. Education was a means of sifting through past inheritance and present concerns for personal rectification as well as for societal needs. Scholars were inspired by the ideal of learning in order to improve themselves rather than to impress others. To suggest, as some scholars have, that Confucianism promoted only rote memorization or rigid traditionalism is to overlook many of the subtleties and differences in the process of learning that occurred in different historical times, geographical spaces, and cultural circumstances.

The Confucian emphasis on learning for the improvement of the individual as well as society resulted in a remarkable flourishing of what Wm. Theodore de Bary has called Confucian personalism, by which the self was seen not as an isolated individual but as “the dynamic center of a larger social whole, biological continuum, and moral/spiritual continuity.”75 Critical to this Confucian personalism was a commitment to learning and to scholarly pursuits, a commitment that distinguished Confucianism as a tradition and galvanized individuals toward a path of “learning for oneself.”76 This ideal of learning for oneself implied a deeply felt sense of personal realization along with the potential for finding the Way (Dao) in oneself.77 The passion for learning as a means of transforming self and society no doubt accounts for the remarkable appeal and affirmation of Confucianism across the cultures and societies of East Asia.

In essence, learning was the vehicle toward cultivation of the individual that would in turn affect the family, the society, the state, and even the cosmos. This is most succinctly expressed in the Great Learning, which Zhu Xi selected from the Record of Rites as one of the Four Books essential to any educational curriculum. Hence learning was an activity with great moral and spiritual import. It was not undertaken only for one’s own edification, but for the positive effects on the larger social-political milieu. Through learning, appropriate harmonious relations could be activated between self and society and between individuals and the natural world. In addition, practical learning would benefit the larger society.

Tradition: Legacy, Lineage, and Learning

For Ekken the dialectic between tradition and the individual was a delicate but dynamic one. Learning for him was a lifelong personal commitment to the Confucian Way as well as a means for the appropriation of Confucian ideas for the political, social, and educational realms. How to adapt and adopt the Confucian tradition preoccupied Ekken throughout his life. This is especially evident in his moral treatises, which were intended to spread Confucian teachings to various groups and classes in Tokugawa society.

The Record of Great Doubts bears the fruit of this preoccupation in a carefully constructed document. Although the lines of argumentation are frequently repetitive, Ekken asserts his loyalty to the tradition while demonstrating his ability to dissent from it. This kind of creative dissent is the means by which the Confucian tradition was changed and adapted to new circumstances. It does not approach outright skepticism, but it exhibits its own method of careful inquiry.

This method is evident in Ekken’s urging that distinctions should be made among (1) particular texts, (2) key individuals, (3) significant ideas, and (4) types of scholarship. He notes first that the classical texts are the most reliable, especially the Classic of Changes. Moreover, the language of the classics is, he asserts, significant and should be followed carefully. He takes an example from the Classic of Changes of the Chinese character for “one” in describing yin and yang as a basis for discussing his unified philosophy of the Way. Second, he argues that one should have respect for individuals in the tradition but should also realize that people have blind spots and are not infallible. Thus, for example, the Song scholars may be sagacious but they are not sages. In this respect, the learning of Confucius and Mencius is considered sagely, while that of the Song Neo-Confucians is deemed wise. Third, he believes the ideas of the Song Confucians that rely on Confucius and Mencius should be distinguished from those not rooted in Confucius and Mencius. In this way, one can identify some of the underlying Buddhist and Daoist influences on Song Neo-Confucianism, especially with regard to meditation and quietism. Fourth, Ekken judges that Song scholarship is too detailed, verbose, and scattered when compared with the holistic theories of Confucius and Mencius. He suggests that a scholar ought to start with things close at hand and proceed to more lofty things.

Individual Learning: Doubting, Discerning, Deciding

Ekken’s notion of doubt as a method of inquiry into the tradition and discernment as a means of selectivity within the tradition is complemented by the idea of deciding for oneself as a means of reappropriation of the tradition. All of this depends primarily on the persistence and perception of an individual in pursuing learning. Doubting, discerning, and deciding are the key tools in acquiring knowledge of the Way. Without these tools the tradition could become a stagnant repository of platitudes rather than an enlivened stream of intellectual resources.

Ekken also observes that the Classic of Changes reminds us that the Way is vast and no individual alone can exhaust it. One needs to consult with others who are broad-minded and to place confidence in one’s teachers. Complete self-reliance or subjectivity, he points out, would be inappropriate to the challenging task of pursuing the Way.

The individual is encouraged above all to acknowledge that doubt—appropriate rather than simply trivial doubt—is an indispensable intellectual tool. Ekken’s text opens with a positive view of doubt as promoting progress in learning. A statement included from Zhu Xi underscores this: “If our doubt is great, our progress will be significant; if our doubt is small, our progress will be insignificant. If we don’t have doubts, we won’t progress.”78 Indeed, we are told, as Lu Xiangshan said, “In learning it is regrettable if we do not have doubts.”79 Throughout the text, we are urged to move through the process of doubt and discernment to decision making so that “we should doubt what we should doubt and believe what we should believe.”

Ekken describes this process as one of various stages that may occur in sequence or in a multifold simultaneity. Discernment involves choosing and discarding particular ideas by sifting carefully through various alternatives. This demands having an openness to learning and abandoning self-concern. It requires avoiding narrowness, obstinacy, or bias in one’s view. It also implies that one should not be too critical, arrogant, or aggressive in stating one’s opinions.80 Ekken specifically criticizes the Ming Confucians in this regard. He suggests, rather, that one needs to express one’s ideas with sympathy and sincerity.

Finally, one ought, Ekken notes, to develop the habits of good scholarship: accessibility and simplicity, not abstraction and abstruseness. When all these tools are being applied one can decide for oneself what is appropriate learning within a tradition. One can then follow the Way and adapt its pursuit to one’s own time, place, and circumstances. Accordingly, inquiring, selecting, and reappropriating are the means for the individual to interact creatively with tradition.

It is instructive to see how Ekken’s own text exemplifies his probing method of discernment in terms of both content and style. In particular, the repetition of certain ideas and key phrases clearly have a function of highlighting his main concerns. His style also demonstrates a spirit of open scholarly inquiry along with an invitational tone to the reader to reflect together with Ekken on these issues. Moreover, through repetition an honesty and humility of painstaking rumination are conveyed. Doubting is never complete for Ekken, and, rather like recurring musical cadences, the repetition of doubt reflects stylized permutations with an underlying purpose. Indeed, as a method of inquiry, repetition in the Confucian tradition can be seen as the “practice of learning,”81 one requiring attention and provoking reformulation.

Philosophical Debates Regarding Principle and Material Force

The Nature of the Disagreements with Zhu Xi

Ekken’s disagreements with Zhu Xi focused on the issue of cosmology, in particular the nature and formation of the universe. While this may appear to be simply a rarefied metaphysical discussion, its implications for his ethical thought and his studies of nature are far from abstract. From Ekken’s naturalism outlined as a philosophy of material force, he is able to argue for an affirmation of human nature and human action along with an appreciation of the natural world and its seasonal transformations.

Ekken wished to affirm the unity of the dynamic creativity of the processes of nature and of the Way. He maintained that the processes of nature and of the Way flowed from the same generative source of material force and argued that they could not emerge from what he understood to be the original emptiness referred to by Buddhists and Daoists. He quoted the Doctrine of the Mean to illustrate his point: “The great Way of the sages is vast and it causes the development and growth of all things.”82 Ekken continues, “It flows through the seasons and never stops. It is the root of all transformations and the place from which all things emerge. It is the origin of all that is received from Heaven.”83

Ekken claimed that the Cheng brothers and Zhu Xi had set forth a qualified but dualistic position that tended to separate the Way from concrete reality. He maintained that Zhu argued for the differentiation of li and qi. This resulted in a potential bifurcation of this world and a transcendent realm. Ekken firmly denied that this was consonant with a Confucian sense of the importance of commitment to the world. He argued against such a dualism because he felt it could lead to an idealism that undervalued nature and human action in the world and thus could result in life-denying rather than life-affirming ethical practices.

Ekken argued for a naturalism that saw the universe as emerging and continuing due solely to the operations of material force. He emphasized the unity of this dynamic life process, for it is understanding and harmonizing with this vital force that forms the basis of moral and spiritual cultivation.

The Implications of a Vitalistic Cosmology of Material Force

It is important to note that what distinguishes Song Neo-Confucianism from earlier Confucianism is a more elaborate attention to cosmology and metaphysics. Zhu Xi’s Neo-Confucian synthesis in Reflections on Things at Hand begins with a section titled “On the Substance of the Way,” which draws on Zhou Dunyi’s cosmological “Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate.” This diagram and Zhu’s interpretation of it became the source of Ekken’s doubts regarding Zhu’s metaphysics.

In the Record of Great Doubts, Ekken gives careful attention to Zhu Xi’s interpretation of the “Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate” as a cosmological map of evolution. Ekken’s aim was to distinguish elements in the diagram he felt were Buddhist or Daoist. His concern related especially to two points that, in Ekken’s mind, illustrate the implications of the interconnection of cosmology and cultivation in a way that could devalue action in the world:

The cosmogonic problem of the origins of the universe as seen in the relation of wuji (nonfinite) and taiji (Supreme Ultimate) as either bifurcating reality or as suggesting that the

1. source of all reality is emptiness. Wuji has been translated as the Ultimate of Nonbeing, the nonfinite, or the infinite, while taiji has been translated as the Great Ultimate or the Supreme Ultimate. Joseph Adler has translated them as Non-Polar (wuji) and Supreme Polarity (taiji).84

2. The relationship of these two polarities reflects the ethical problem of potentially prioritizing tranquility and thus emphasizing withdrawal from affairs.

These two points were, in fact, criticized by others before Ekken, often for similar reasons. Perhaps the most famous disagreement occurred in a series of debates between Zhu Xi and Lu Xiangshan over the wuji–taiji issue. Ekken concisely summarizes the problem: “The Supreme Ultimate [taiji] originates from the nonfinite [wuji] and thus establishes making quietude central as the fundamental mode for humans. These concepts have been transmitted from Buddhism and Daoism.”85

Okada Takehiko has outlined the points of Ekken’s disagreements with Zhu Xi:

[T]he doctrine of the Supreme Ultimate and the Infinite (t’ai-chi wu-chi; taikyoku mukyoku), the doctrine of abiding in tranquility, the doctrine of quiet-sitting, the identification of nature with principle, the distinction between an original nature and a physical nature, the dualism of principle and material force, the idea of the indestructibility of principle and the nature, the idea of clear virtue as tranquil and unobscured, the idea of the Principle of Nature as empty, tranquil and without any sign, the idea of one source for substance and function, and the idea of the identity of the manifest and the hidden.86

The opening line of the “Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate” is “The Ultimate of Non-Being (wuji) and also the Great Ultimate (taiji).”87 This line refers to the origin of all life and has been subject to numerous interpretations and debates. The central problem in the debate is the role of wuji and its relation to taiji. The problem is exacerbated by the ambiguity of the linking word er, which means “and also” or “in turn.” It can likewise be translated as “and then,” which implies a separation between these two entities. Zhu Xi’s comments on this line imply that he is trying to hold these two terms in creative tension:

“The operations of Heaven have neither sound nor smell.” And yet this [Ultimate of Nonbeing] is really the axis of creation and the foundation of things of all kinds [ultimate being]. Therefore “the Ultimate of Nonbeing and also the Great Ultimate.” It does not mean that outside of the Great Ultimate there is an Ultimate of Nonbeing.88

It should be noted that Wm. Theodore de Bary has argued that Zhu Xi did not use wuji as simply a Daoist principle of emptiness out of which reality emerged. Rather, he suggests that “wuji and taiji were inseparable aspects, not successive stages of being. They were correlative aspects of a Way that was in one sense indeterminate and yet in another sense the supreme value and ultimate end of all things.”89 The implications of this are significant for the link between cosmological principles and self-cultivation. The Supreme Ultimate, or principle, is manifest in each individual human nature. However, the cultivation of this opens one up to the inexhaustible potential of boundless creativity. Thus for Zhu Xi, the human mind is “empty and spiritual yet replete with principle.”90

The dynamic relationships between the cosmological principles of wuji and taiji and their implications for self-cultivation are at the heart of Ekken’s concerns. Even if, as de Bary argues, Zhu Xi did not intend wuji to be equated with emptiness, Ekken was nonetheless particularly worried that wuji may be perceived as comparable to emptiness or nothingness in a Buddhist or Daoist sense. The difficulty Ekken saw issuing from this perspective is that by positing wuji as the foundation of everything, one may tend to see the myriad things that arise as illusory and quietism may be a consequence. This is Ekken’s principal concern as he questions the origins of the Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate and the uses of the term wuji. Ekken notes that while Zhou employs the term in the “Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate,” he does not refer to it in Penetrating the Classic of Changes. He suggests that the Cheng brothers never used the term wuji. In noting its Daoist and Buddhist links, however, he claims the term appears first in Daoism in Laozi (chap. 28) and then in Buddhism in the Huayan View of the Realm of the Dharmas (Huayan fajie guan) of Dushun (557–640).91