Cultural Warfare

Chapter 4 engages with the dialectical relationship between culture and politics. As ideological reasons alone do not account for the creation of the Greek student movement, the chapter explores the roots of its cultural background, as well as the ways in which the latter in turn reinforced student combativeness. It examines new trends in cinema, theater, music, aesthetics, and everyday life in an attempt to explain how new cultural identities were shaped. It turns to alternative forms of culture that were created in juxtaposition to the Junta with an interest in how several countercultural elements acquired political significance over time. This section also addresses the role of female students in both the student body in general and in the movement in particular, in an attempt to account for continuities and ruptures with the past. Lastly, references are made to the contested issue of a belated “sexual revolution” and private going public.

Just like any other authoritarian regime the Colonels tried to achieve near complete control of the mass media in order to ensure an informational monopoly. Preventive censorship was in operation up to 1969, and no printed document could circulate without the authorization of the Censorship Office. This created a vacuum of alternative information and intellectual cultivation, as the heavy weight of voicing opposition fell on clandestine papers. Inevitably, the very moment the regime allowed relative freedom of expression, parts of the press began to express a mild critique of its governance, breaking its “information monopoly.”1

Since 1967, Greek writers had refused to publish anything as a means of demonstrating passive resistance through silence. “Refusing to submit your writings to be examined by the police authorities and the censorship office is after all an issue of self-respect and self-dignity,” said writer Spyros Plaskovitis in talking about this period.2 This proved to be a controversial decision that contributed to the lack of the circulation of any alternative and heterodox ideas during the first years of the dictatorship. In fact, Filippos Vlachos, the founder and director of the publishing house Keimena [Texts], appeared extremely critical of this tactic years later concluding that “silence was also convenient … an escape, not resistance.”3

Whereas antiregime artists continued to protest by refusing to write, publish, or exhibit, some journalists devised a range of strategies to counter the effects of censorship. Integral to their creativity in resistance was the fact that repression helps to create new sorts of knowledge and different ways to communicate a message. According to Michel Foucault, “Censorship not only cuts off or blocks communication, it also acts as an incitement to discourse, with silence as an integral part of this discursive activity.”4 In this sense, erasure can be enabling as well as delimiting. Comic strip artists, such as Bost, Kyr, and Kostas Mitropoulos, who collaborated with the major dailies of the time, were among those who managed to undermine censorship most successfully through references, allegories, and innuendos that were confusing to the uninitiated but easily discernible to the ones looking for a hidden message.5 American writer and Athens resident at the time, Kevin Andrews argued that people who were hastily reading these cartoons in the papers “almost had the sense of participating at the cost of a couple of drachmas, in resistance activity.”6

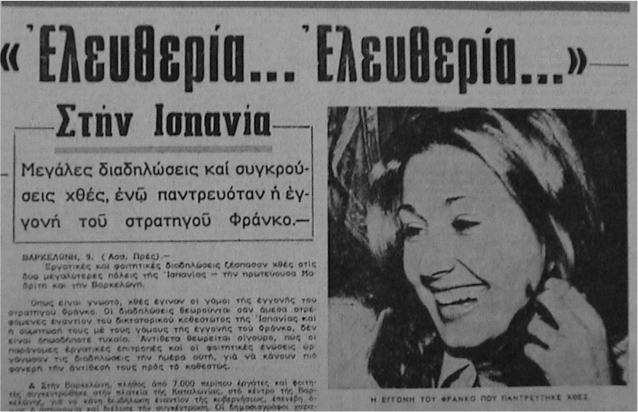

The press was a major factor in the dissemination of information and the development of the awareness of the political situation in Greece under the Junta. In so far as the press fully covered the court-martial trials and published complete trial transcripts, it provided an opportunity for students to learn about resistance efforts. The pleas of the accused offered them the opportunity to defend their actions while condemning the regime and reporting having been tortured. The press also offered detailed, often provocative full coverage of student mobilizations. The Athenian and Salonicean dailies Ta Nea and Thessaloniki dedicated a daily column to student issues (both using as their logos images associated with May ’68), which served as means of constant update on student mobilizations. Minas Papazoglou’s column in Ta Nea, titled “Youth and Its Problems,” promoted the antiregime students’ demands and criticized the appointed student councils during the spring and summer of 1972. The column also published letters of protest by antiregime students. A series of journalists writing for Thessaloniki followed the same pattern in their regular feature “The Students’ Column.” According to a US report, Thessaloniki was an “anti-American [and] anti-regime” publication with “strong influence among younger leftists and students.”7 Chrysafis Iordanoglou, a law student in Salonica, emphasizes, “If this communication medium with the journalism it represented had not existed, it is doubtful that the student movement of Salonica would have survived.”8 Another typical pattern of Thessaloniki was to present the student unrest in other countries with large headlines, extensive photographic material, and direct allusions to the Greek situation. Typically, a large headline would read “The Militaries Are Panicking” or “The Student Revolt Is Spreading,” and with tiny letters underneath one would read “in Italy” or “in Spain.”9 It is not at all surprising that Thessaloniki’s director, Antonis Kourtis, was constantly warned and fined by the regime.10

Figure 4.1. Headline of the antiregime daily Thessaloniki reading “Freedom … Freedom,” and with small letters in the subtitle “in Spain.” This was a typical strategy of the newspapers during the Junta, testing the boundaries of censorship. (Source: Thessaloniki newspaper)

As was the case with students elsewhere, Greek students read the papers voraciously in order to find out what was going on in the world in a period of dramatic events, from the Vietnam War to the Middle East crisis, and also to read accounts of events in which they themselves had participated, resulting in a rather self-reflexive position. Giannis Kourmoulakis observes: “Messages were coming, even if curtailed, but they found fertile ground and they touched us. And somehow we started as well little by little also to get revolutionized” (Kourmoulakis, interview).

As we have seen, the dictatorship’s liberalization experiment proved to be crucial for the development of the student movement, contributing to a significant change in the political and social climate of the country. One major reason for this shift was the production and circulation of books, a defining factor for the enhancement of antiregime consciousness among students. The critical silence-breaking moment in publishing was the publication of the Dekaochto Keimena [Eighteen Texts] (1970), which followed a 1969 dramatic statement by the Nobel Prize–winning poet George Seferis condemning the Junta at the BBC—the first public condemnation from within Greece made by a respected, noncommunist intellectual.11 These eighteen allusive literary texts were written by well-known intellectuals who avoided naming the Greek Junta outright but used, in the words of one of the contributors, “innuendo, transposition and … metaphors which the reader could easily understand, but for which it would be difficult for the authorities to prosecute.”12 Four short stories, for example, referred to a fictitious Latin American country under dictatorship called “Boliguay.” The experiment was followed by the publication of Nea Keimena [New Texts] and Nea Keimena 2 and the journal I Synecheia [Continuity] by the same circle of intellectuals, including a number of left-wing writers.13 In April 1973 one of the contributors to this symbolic rupture, the poet Manolis Anagnostakis, appeared self-critical about the years of artistic silence:

What could be … the picture—if any—that today’s twenty-year-old youths, who were 14 then, might have of the condition of our cultural and political landscape before the April coup? If we talk to them … about the Spring that was about to bloom on our intellectual horizon, what mechanisms of representation do they have to follow us? With what depot of nonexisting experiences would they grasp what the three-year relentless silence meant, and how would they be convinced about the necessity of the intellectual transition to a specific moment in time from speechlessness to direct discourse?14

The publication of Eighteen Texts coincided with the regime’s decision to open itself up, suspending preventive censorship and abolishing the last blacklist of books in 1970. Up to 1969, the only publishing houses that had been established and whose books became points of reference (Keimena, Kalvos, Stochastis) focused on classical political thought and literature. The softening of censorship led to a spectacular increase in domestic cultural output, however, and publishers found a way out of the previous stagnation.

From late 1970 to late 1971, 150 new publishing houses were opened, and 2,000 new titles were printed in inexpensive paperback editions.15 This overproduction of publications aimed to encourage critical thinking in young readers, which could help them to understand existing realities. Books were needed that would provide a “practical perspective” or a way out of the political impasse. Publishers believed that through books, they could “ideologically awaken the people against the dictatorial regime,” as they believed that books would be food for the intellectually starving Greeks and a direct means of political acculturation.16 Some publishers were oriented toward the publication of left-wing books (Odysseas, Praxi) with a program that “covered the range of Marxist and Leninist books” (Synchroni Epochi), the “renewal of official Marxist thought” (Odysseas), the “ideological armament of young people” (Neoi Stochoi), and the “creation of an antiauthoritarian movement in Greece” (Diethnis Vivliothiki).17

Books like Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber’s The American Challenge, John Kenneth Galbraith’s The New Industrial State, and Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy’s Monopoly Capital soon became bestsellers, just as they had abroad.18 Vladimir Ilyich Lenin and Karl Marx, as well as Mikhail Bakunin, Rosa Luxemburg, and Gyorg Lúkacs appeared in bookshop windows. American writer Kevin Andrews observed that “after 1970 some foreigners wondered how Greece could be a dictatorship when the kiosks around Athens University were filled with the works of … Marxists of the Twenties and Thirties, all in paperback.”19

Other publishing projects aimed to satisfy readers’ need to reexamine phenomena and problems from within the tradition of contemporary Greek philosophical and sociological standard works. Those books introduced a new closer theoretical scrutiny. Publishing was limited at the beginning (1970–1971) but more extensive later on. Andrianos Vanos explained how the slow trickle of books in 1970 and 1971 acted as a catalyst for the dissemination of ideas:

There was something that was very much of help, apart from the illegal books that circulated, which in a way helped everybody: That just before this political explosion took place, political publications started coming out, like those of Kalvos, or others, but which were coming out little by little, since up to that point no books were published. So, everyone read the same books. … A book would come out, and since there was no other, everybody was talking about it. So, we were analyzing from all sides. Same thing when another book would come out. So, in a way we were following some common steps. There was no chaos in information. (Vanos, interview)

Within the ’68 movements the expression “3 M’s” was a quite common way to refer to the fashionable theoretical triangle between Marx, Mao, and Marcuse. The (re)appearance and large-scale diffusion of a series of basic Marxist texts by Greek and foreign authors through Themelio [Foundation], a traditional left-wing publishing house that had been closed down immediately after the coup spread this expression among Greek students.20 Neoi Stochoi [New Aims] was a Trotskyist publishing house that exercised even greater influence through a series of publications, as well as an eponymous journal. With articles from a whole range of Marxist revolutionaries and writers, Neoi Stochoi made the first attempt to defy the barrier of censorship and test its limits by openly adopting Marxist terminology. Its publications appeared in a pocket-sized format in order to reach a wide readership, rendering so-called alternative Marxist analysis an extremely popular and common point of reference. Nikitas Lionarakis offers a comment on the influence of Neoi Stochoi: “I have studied Marxism through the Neoi Stochoi. My entire generation, that is … This approach of the publishing houses ‘Marxified’ our generation very much. That is, it turned [the] insurrection into a Marxist one” (Lionarakis, interview).

Among the most fashionable topics diffused in these “unorthodox” publications featured so-called center-periphery and third-worldist theories of a global class struggle that would supposedly result from the student periphery, joined by the working classes, closing in on the imperialist pole. As might be expected, the Greek political stalemate was another favorite topic, framing the imposition and maintenance of the dictatorship as a token of US imperialism. The “foreign factor theory” became a permanent element in Greek conceptualizations of politics.

It is noteworthy that some students at the time attributed the re-appearance of Themelio and the circulation of Neoi Stochoi to the police. A common pro-Moscow communist trope held that the police allowed Neoi Stochoi to be published in the hope that the journal’s Trotskyist line would divide and disorient left-wing students. Interestingly, however, followers of the Communist Party were among Neoi Stochoi’s fanatic readers, despite the fact that “instructors” warned the students that it might be a governmental provocation.

These publications spurred on the diffusion of sociological works and the rediscovery of the classics of socialism (Marx, Lenin), as well as social theory (the Frankfurt School, Louis Althusser) and psychosexual theory (Wilhelm Reich). Antonio Gramsci and Regis Debray, “heretical” writers according to the standards of the Old Left, were among the most translated authors. Their works, which challenged Marxist orthodoxy, became fashionable among the New Left and were intellectual landmarks for many students. They tapped into the students’ desire to oppose authoritarianism, revealing a growing demand for revolutionary and subversive texts. Marcuse’s One-Dimensional Man, “the gospel of ’68” according to student Ilias Triantafyllopoulos, became a guiding book that familiarized the Greek radical readership with the idea that students and disenfranchised social outcasts would be the future carriers of social change, instead of the “compromised” working class. Marcuse’s motto, “The only hope lies with the hopeless,” became a slogan. As Triantafyllopoulos explains: “Through Marcuse I started rather to realize, to rationalize or to interpret the world. Marx came afterward, then came all the other things, but we started with those everyday situations, the elements of lived experience” (Triantafyllopoulos, interview).

The need to be up-to-date with the latest trends in critical theory became part of socialization among student groups. Law student during the Junta years and present-day constitutionalist Nikos Alivizatos notes the impact of the radical French maîtres a penser, stressing that those students who did not possess some basic knowledge of theories, such as structuralism and poststructuralism, were considered uncool: “In terms of readings, France was, of course, the center of the universe and the whole Marxist structuralism with Althusser, Poulantzas, and all the things you can imagine. To put it bluntly, in the post-’68 climate you could not date a woman if you hadn’t read Althusser” (Alivizatos, interview).

Less influential were the Soviet books, such as Leninism and Modern Times, published by Synchroni Epochi [Modern Times], the publishing house affiliated with the Communist Party. Though widely read, these were often perceived as passé. “Books of the Soviet school of thought did not endure over time,” former communist student leader Nikos Bistis remarks, citing as an example “a book on Czechoslovakia, which had come out right after, which justified the invasion with puerile arguments” (Bistis, interview). Nikos Kaplanis, a dentistry student in Salonica and head of the clandestine KNE, argues the opposite, “In terms of Prague, I personally was fooled by KKE’s myth that whatever thing is not ours cannot be revolutionary either” (Kaplanis, interview). The leftist *Pavlos recalls that he and others like him became obsessed with books on Marxism-Leninism in order to address their theoretical deficits, since they did not come from left-wing families. Still, the vast bulk of students joined the orthodox communists, reserving their heretical training for future occasions, as Bistis points out: “It is impressive that although the first books that were circulated were ‘heretical’ books of the Left or the American Left, Marcuse and so on, the great majority of the youth joined the KKE in the end” (Bistis, interview).

Marxist indoctrination was so widespread that even conservative professors who had outlived the purges of the Junta were aware of it. Angeliki Xydi goes so far as to maintain that these professors even adopted an apologetic stance toward the Marxist students:

I remember that we had a philosophy professor at the university, Mr. Moutsopoulos, who entered at the second year of the department where I was, and he knew that the things he would say would seem to us rubbish, even if we wouldn’t tell him that they were rubbish. And he would tell us, “Alright, I apologize to the Marxists.” Yes, and these things right in the middle of the Junta. (Xydi, interview)

Alkis Rigos, meanwhile, reconstructs students’ tendency to use their theoretical arsenal to confront the Junta’s professors:

We had many Junta professors in the university, namely, ministers of the Junta. Our professor of sociology was Tsakonas, who was minister of the presidency, that is, of propaganda of the dictatorship, and who was offering some supposedly free seminars, and, after we argued with each other on whether to take them or not, we decided that we should participate, but in order to tear them apart. We would show off how left-wing we were, but with arguments. One couldn’t use the empty political rhetoric that we had right after the Metapolitefsi. One talked about the substance. (Rigos, interview)

The distinction that Rigos draws between the fruitfulness of discourses and theoretical explorations, both during the time of the Junta and the period of the democratic transition, is present in most recollections.

In the first years of the 1970s, the publication of any book of critical thinking, including literary works, could be assessed as political resistance against the authoritarian regime, and almost every book could be considered political.21 Dissident figures such as the Turkish poet Nazim Hikmet and Chilean poet Pablo Neruda were translated repeatedly during the dictatorship and read in a heroic light. Ioanna Karystiani stresses the importance of poetry in the training of the students. In her view, poetry’s contribution was literal rather than ideological, though for her own part she argues for a self-sacrificial romantic determination: “This is how I tuned in, by reading poems, having read Ritsos, Dostoyevsky, by reciting Mayakovsky, and these were … ideological equipment in the full sense” (Karystiani, interview).

It seems that publishers who sympathized with the student movement often exploited young people’s eagerness for new ideas. An article that appeared in 1973 in the literary journal I Synecheia condemned the fashion of “transferring the foreign problematization which emerge[d] from a different reality [and] translating it into Greek without any introduction or even warning about the different conditions.”22 In many cases, the introductory sections of the books seem entirely out of place, trying to establish connections with the Greek case no matter how different the paradigm was, while the quality of the translations was often very poor.23 In another issue of I Synecheia, a literary critic concluded, “We had forgotten that enlightenment needs enlightened people.”24 Others felt, however, that the uncontextualized appearance of such literature in Greek could serve as a useful intellectual exercise. Myrsini Zorba remarks: “I fell onto Gramsci and there I started having more complex thoughts, but this is how you realized that you could interpret any text and any thought on the basis of your own needs and your own experience. Radicalize it, orient it toward a different direction” (Zorba, interview). Michalis Sabatakakis, on the other hand, is firm in his conviction that publishers paid too little attention to Italian and French Euro-Communism:

There was a suffocating absence of books about the stream of thought which in that period was blossoming in Europe within the environment of the communist Left and was called Euro-Communism. … In reality, we did not systematically follow all this stream of thought, whether this was the Italian Euro-Communist school around the PCI, the Italian Communist Party, or the French one, let’s say, with the characteristic case of Poulantzas. Only too occasionally. This was our contact with the political book” (Sabatakakis, interview).

Andrianos Vanos stressed the fact that readings created cohesiveness, due to the pressing need to put new ideas into action. In his view, this process produced people with a firm theoretical background: “People with a solid theoretical training emerged, who had read, who had discussed, who had exchanged conflicting views, without a theoretical aim, an exercise on paper, but with the intention of applying all this” (Vanos, interview). Panos Theodoridis, on the other hand, points out that all these heterogeneous and fragmented readings often created intellectual chaos: “We were reading chunks from Marx, Lenin, Trotsky, the anarchists, all the time; our education was full of things like that. We were continuously reading French intellectuals and monopoly capitalisms … , things that we half understood, but half of which we didn’t understand a word.”25

Books on the history of the Greek Left focusing on the 1940s, the resistance, and the civil war were another point of reference for students. These were very popular at the time, since students liked to think of their own struggle as the continuation of the mythical, albeit defeated, Greek Left, just as the dictatorship was the natural outcome of decades of arbitrary right-wing rule. In contrast to Italy and the critique of the Resistenza by the ’68ers, student activists in Greece in the 1970s did not attack this sacred shibboleth of the Left. Instead, they idealized the wartime communist resistance and its revolutionary tradition. Les Kapetanios (Paris, 1970), a book by the French author Dominique Eudes, provided a romanticized version of the Greek partisans and became a best-selling vehicle of instruction, as for Greek students up to that point “there was a gap, a void, a black page” concerning this period (Tsaras, interview). The old partisan songs likewise reemerged as an emotional form of entertainment and a “transfer” of the revolutionary spirit of history. In terms of aesthetics, the “wild bearded men” of Greece in the early 1970s were strongly reminiscent of the communist guerrillas. Giorgos Kotanidis recalls fantasizing about “the revolutionaries with the red flags going down Alexandras Avenue,” an inescapable reference to EAM/ELAS; “My dreams were deep red,” he reminisces, stressing the revolutionary color of his imaginary projections.26

In addition, the publication of a series of protest magazines promoting “critical thinking” (Prosanatolismoi, Protoporia, Politika Themata, Anti) and a series of underground magazines that focused on avant-garde art (Lotos, Tram, Kouros, Panderma)27 caused a considerable stir with the authorities.28 There followed a series of translations of basic texts on student uprisings abroad, which provided the theoretical toolkit for student revolt. The collective volume Student Power is a major example (1973). According to its introduction, “Just as the liberation movements of the Third World have long ago decided not to wait for the liberation of their countries as a consequence of the socialist revolution in the imperial metropolis, so students today refuse to wait for some external deliverance from their condition.”29 Fred Halliday’s chapter from the volume had been published separately a year earlier under the title The History of Student Movements Worldwide (thus modifying the original title “Students of the World Unite”). According to Trotskyist militant Giannis Felekis, this little booklet on Argentina, Vietnam, and Palestine, was priceless as it introduced multiple revolts from which one could draw valuable conclusions (Felekis, interview).

All these readings were a precious resource for the circulation of information on theoretical matters connected to the movement, as well as on international developments. In the foreword to Student Power, the Greek editor issues the warning that although “the assimilation of the experience of others is necessary, at the same time the mechanistic transfer of models of thought and action which were shaped under entirely different conditions would be unrealistic.” Nonetheless, that book would provide Greek readers a chance “to approach the questioning, the demands and the methods of students beyond Greece.”30 Often, the Spanish model was evoked as one to emulate, as in Fred Halliday’s remarks, reproduced in the student journal Protoporia: “The Spanish students succeeded. They created reaction in the illiberal regime of the Caudillo, proving that student forces can act under conditions of fierce repression.”31

The ritual whereby left-wing books were acquired is also worthy of consideration: they could be purchased at left-wing bookshops or at street vendors. Some of the bookshops became meeting places for discussions, such as Manolis Anagnostakis’s and Kaiti Saketa’s bookshops in Salonica and Manolis Glezos’s bookshop in Athens, which were attacked by extreme right-wingers on more than one occasion. Saketa remembers that when a new book was published and ordered from Athens, her shop would put its cover in the bookshop window for students to see. “Such was the longing of the people” (Saketa, interview). One student bookshop in Athens with a fanatic readership was called The Clockwork Orange, a classic reference to a film that had acquired a cult status despite its being banned. The bookshops also became meeting points where hard-core political analysis took place. As sociologist Hank Johnston argues, “When political opportunities are severely constricted, much of the doing of contentious politics is talking about it.”32 Paraphrasing Primo Moroni and Bruna Miorelli, one could say that in 1970s Greece the old eighteenth-century idea of the bookshop as a place of culture was combined with the modern one of the market opening onto the street.33 Rena Theologidou’s recollections are evocative of the depth and fervor of the students’ dialogue at their bookshop meetings:

We were going to Kaiti Saketa’s [bookshop] and we gathered there, she was KKE-Esoterikou. She had a basement down there. And we were saying, “What is the revolution like?” “Is it this way?” “Is it that way?” “Should we publish Avgi clandestinely?” “Should we not?” (Theologidou, interview)

Many students immersed themselves fully in this climate of intellectual overproduction and became manic consumers of the printed word. The Guardian pointed out in 1972, “The security authorities have long been worried about the effect these [books] might have among students as, with the news media comparatively muzzled, they are making increasing use of the wave of left-wing books which have been appearing.”34 Thereafter, the new list of “discouraged books” included books by Marcuse, Garaudy, Sartre, and Brecht, which were, however, already sold and circulating in massive numbers. As publisher Loukas Axelos suggests, “Regardless of the quality of the responses [these books] gave to the present and the future, they were literally sucked in by the already awaiting, and at this point reading, public … mainly by the students which were its basic body.”35

Political books undoubtedly contributed to the creation of a critical stance and to the shaping of an alternative political position on behalf of the students. Book consumption and the circulation of journals helped create a common style and transmit a universal and direct message by the encouragement of creative reading.

Jean-Luc Godard has famously argued that film is “a gun that can shoot twenty-four frames per second.” It was precisely this capacity of cinema to impregnate people’s minds with ideas and to radicalize its spectators that was internalized by the militant student audiences of the time. The large-scale diffusion of the journal Synchronos Kinimatografos [Contemporary Cinema], which became a standard point of reference, encouraged the generally enthusiastic reception of the French and American avant-gardes and the trend in Greek political cinema known as “New Greek Cinema.” The journal—the Greek equivalent of the French Cahiers du Cinéma—was concerned not only with cinema but also with general theoretical discussions and debates, usually seeking connections to politics.36 It was the successor to the influential Ellinikos Kinimatografos [Greek Cinema], which had published five issues before the coup, including articles by the French critic André Bazin on “how film as a medium was difficult to read for clear cut messages.”37 Beginning in the late 1960s, New Greek Cinema followed this rule by adopting indirect codes of expression in order to communicate sociopolitical messages. In the face of strict censorship, the filmmakers of New Greek Cinema began using a cryptic visual language that could elude the censor’s eye. This was done through metaphors, allusions, and elliptic filmic language. In Pandelis Voulgaris’s movie The Matchmaking of Anna [To Proxenio tis Annas] (1972), for example, the restriction on female subjectivity, personalized by a thirty-year-old domestic servant working for a middle-class family in a world dominated by male power relations,38 offers a strong critique of social relations in early 1970s Greece while it also seems to refer to the country’s suppression under the domination of the Colonels or the United States. This kind of cinema was occasionally rejected by young politicized spectators, however, and in 1971 there was already criticism of the “students and liberals who fill the cinema Alkyonis and all at once praise often insignificant films, just because they were ‘transmitting a message.’”39

The New Greek Cinema also sought a return to an authentic Greek rural spirit, symbolized in The Matchmaking of Anna by the maid from the provinces and the “real,” “authentic” culture that she represents, which comes across as a liberating force. In a similar manner, Theo Angelopoulos’s Reconstruction [Anaparastasi] (1970), about a murder in the Greek countryside, was filmed in a remote village that led him to “discover” the traditional rural spirit: “This was the image that was representative for me. I, a man of asphalt, pollution, Athens, suddenly came to know a part of Greece, I came to know Greece, the middle Greece, the unknown Greece.”40 This rediscovery of Greek “roots” and of rural tradition also became conceptualized as a pole of resistance in terms of music, as will be shown later. However, *Katerina remembers a discussion at EKIN following a screening of Reconstruction, in which she was irritated by Angelopoulos’s “folklorist mannerisms” (*Katerina, interview).

More than Reconstruction, Angelopoulos’s direct indictment of the Junta came in 1972 with his film Days of ’36 [Meres tou ’36]. This was a film that chronicled the coming of the dictatorship of General Metaxas in 1936: clearly speaking about one military regime in the context of another was too direct a message to be missed. As for the film’s cryptic mode of expression, the filmmaker himself is quite revealing: “The dictatorship is embodied in the formal structure of the film. Imposed silence was one of the conditions under which we worked. The film is made in such a way that the spectator realizes that censorship is involved.”41

The new manner of filmmaking led to a rift with mainstream Greek cinema productions, which consisted of farces, war epics, and melodramas—formulas that had proven commercially successful. Because mainstream Greek cinema was endorsed by the dictators, they were viewed as a major cultural weapon aimed at imposing a “stupefying sentimentalism,” according to film critic Giannis Soldatos.42 The New Greek Cinema film productions, by contrast, were characterized by social sensibility and a direct and unsentimentalized approach to everyday stories with neo-realist and Brechtian characteristics.43 Even films with no blatant political characteristics, such as Giorgos Stamboulopoulos’s Open Letter [Anoichti Epistoli] (1968), a film about a disoriented young man and his constant mental references to the Occupation period (which was nevertheless butchered by censorship), or Angelopoulos’s Reconstruction, were consumed and received by antiregime actors as purely political. In other words, spectators of a general antiregime disposition were reading the political into everything.

Cinema became extremely significant not only in terms of its form, content, symbolism, and reception but also as a point of meeting and recognition. The discussions that necessarily followed the screenings were of vital importance: “[I remember] the terrible explosions in the discussion of Alkyonis following the movies,” Myrsini Zorba recalls, “where the hard-core ideological confrontation lurked once again as soon as the lights were turned on” (Zorba, interview). In Salonica, a law student, Vangelis Kargoudis, took the initiative to organize a cinema club, which ended up having four thousand registered members. The club soon became an important meeting point, attempting to bring students closer to the spirit of the movies of the time. Political cinema was the most popular genre, including films such as Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Spider’s Stratagem and The Conformist (1970), both about the rise of Italian Fascism. Such screenings were often linked to political provocation: “We searched and found Melville’s movie, The Stool Pigeon, and we put big posters around the city, ‘The Stool Pigeon!,’ ‘The Stool Pigeon!’” (laughter) (Kargoudis, interview).

In the cinema club, too, the movies were followed by a three-hour discussion directed by Kargoudis himself. This practice focused on the dynamic aspects of collective viewing and the communal experience of watching and debating about a film, juxtaposed with the solitary practice of reading books and the “passive” viewing of television. The debates following the screenings, which were also attended by policemen in civilian clothes, reinforced the quite popular idea of the active and reflexive spectator. Students soon became real film buffs. Vourekas remarks:

The cinema club was in reality a forum for political discussion. It was a context which legalized politics, ideological discussions, and confrontations within the Left and its streams. So it happened. We all got registered of course in the cinema club, with ID cards and everything. Naturally, the police watched [the movies] too, and there were screenings of Italian neorealism but also more recent movies, for example Godard—hermetic, difficult, but it looked as if he was trying to say something. (Vourekas, interview)

The club’s organizer, Kargoudis, was the one to pay the price for any sort of revolutionary exaltation during the discussions: “I got beaten black and blue for any nonsense that the PPSP and EKKE people said. This had become standard; screening on Sunday, on Monday I was arrested at home” (Kargoudis, interview). Kargoudis recalls with emotion the cinema club’s last session:

At some point we realized that this was the last Sunday and that they were going to hit us. … Around 9, 9:30 in the morning there came two riot vehicles, which were brand new, they were received in ’72. And they blocked Pallas cinema in a vertical fashion, one from here and one from there, and there was a big gathering, according to the more modest calculations 700 to 800 persons. And the whole thing turned into a demonstration, and the respective beatings took place too. (Kargoudis, interview)

Although the Maoist organizations were, alongside a handful of anarchists, the most faithful carriers of the spirit of the ’68 uprisings, they often opposed culture of all sorts. This attitude was probably inspired by the general destructive mania of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, which rejected all artifacts as products of bourgeois decadence. Greek Maoists’ rejection of the aesthetics of most ’68 movements as “bourgeois” was reinforced by the conviction that art could only be engaged with, since its main task was to generate an oppositional political consciousness. Panos Theodoridis recalls that in 1973, at the invitation of the appointed student council, the composer Manos Hadjidakis came to Salonica with the filmmaker Pandelis Voulgaris in order to present Magnus Eroticus [O Megalos Erotikos] (1973) at the city’s Film Festival. Voulgaris’s film was inspired by and based on Hadjidakis’s eponymous LP. Left-wingers were furious, Theodoridis says, though “deep inside we were all Hadjidakean.” Similarly, Vourekas explains that to young people like him it seemed utterly inappropriate to produce an artistic creation that disregarded the political situation:

It seemed to me quite extreme to release Magnus Eroticus during the Junta. It broke my nerve, I couldn’t … this thing seemed unbearable to me. … I was an enemy of his music precisely because he could not express what all the rest were feeling. Expression for us was action, political struggle, anti-Junta, antidictatorship action, what could the Magnus Eroticus say to us? We considered it an irony at least. A man, a petit bourgeois, closed inside his world, “Here the world is falling apart and the whore is washing her hair.” Precisely this, this was the sensation. And we snubbed him and despised him. (Vourekas, interview)

Panos Theodoridis still regrets this attitude today: “To have in the midst of the years of the Junta and all this turmoil … two sensitive persons talking about erotic discourse was for us the most insulting thing, so we went into the dress circle and booed Magnus Eroticus. This is one of the deeds of which I will be ashamed for the rest of my life.”44 His sentence clearly represents the abyss of temporal and semantic distance between past and present self.

Similarly, in a characteristic discussion following the projection of Theo Angelopoulos’s Reconstruction, at which he was present, a hard-core group of Maoists attacked the up-and-coming filmmaker and the most charismatic exponent of New Cinema in Greece, as petit-bourgeois. Andrianos Vanos, a Maoist student himself, vividly remembered Angelopoulos’s screening, though in a very different way. In his recollection, these screenings were the point at which the conflict went public:

Clashes took place, no matter which movie was coming to the cinema club. But the people in charge brought Angelopoulos, they brought him and he made a speech. Another hundred policemen gathered, and we couldn’t get in anymore, and a conflict started in the city. In the open. Not introverted, within a cinema. So, everything was going outdoors. (Vanos, interview)

Even though Vanos mentions the cinema club, in reality his description is of the screening of Reconstruction at the State Theater during the Film Festival, where it won the award for best film of the year (1970). Angelopoulos himself recalled that a demonstration started immediately after the ceremony, with students cheering at him in exaltation since “at any opportunity that was given there was an attempt to do something against the dictatorship.” He described a screening of the film at the University of Patras that same year, 1970, as a poignant moment that characterized the cryptic communication between artists of the time and their audiences. During the discussion that followed the film because policemen were present in civilian dress, Angelopoulos recalled that students asked questions in a hidden manner, and he gave affirmative answers. Angelopoulos characterized such peculiar communication “between the lines” as a form of magic, as it was denser than any detailed explanation.45

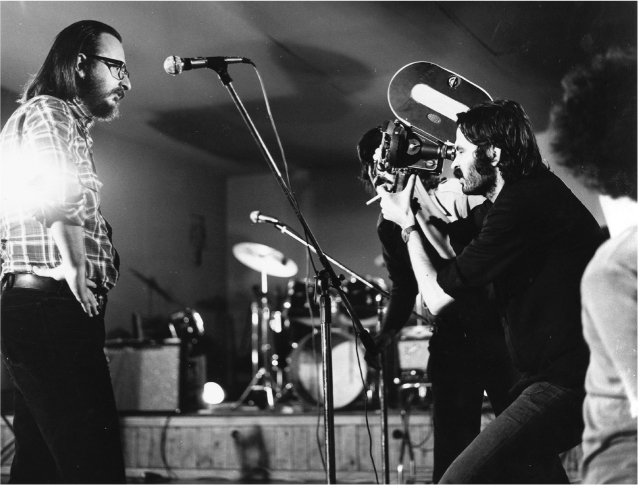

In its attempt to censor movies, the dictatorial regime constricted itself to a naive handling of film topics, searching for messages only on the surface (slogans, songs, and labels), so that movies with indirect social implications and political dimensions escaped the censor’s eye. From the early 1970s onward, however, amid the softening of censorship and the rise of general radicalism, the politicization of Greek directors became blatant. This shift is apparent, for instance, in Thanasis Rentzis and Nikos Zervos’s film Black-White [Mavro-Aspro] (1973), which contained direct references with footage of a “cinéma-verité” kind to the rising student movement and castigated social apathy. Even “conformist” directors chose to use words like “democracy” and “weapon” in their titles in order to attract an audience with vague references to politics and revolution.46

Figure 4.2. Scene from Thanasis Rentzis and Nikos Zervos’s movie Black-White, 1973. The student protagonist enters a record store in Athens and stares at a poster of Frank Zappa, while in the background one can hear a song by Deep Purple. The film shows the extent of familiarization with Western pop culture, including progressive rock. It also contains direct references of a “cinéma-verité” kind to the rising student movement. (Courtesy Thanasis Rentzis)

Greek students discovered Soviet and Eastern European cinema—first and foremost Sergei Eisenstein and the legendary Hungarian Milos Jancso—and were equally attracted to the innovations and experimentations of the French Nouvelle Vague; as Antonis Liakos aptly put it they were “the bastards of Hollywood, Eisenstein and nouvelle vague.”47 They were also seduced by the liberating energy of films such as Paul Williams’s Out of It, which treated the subject of rebellious youth in the United States; angered by the injustice committed against Sacco and Vanzetti in Giuliano Montaldo’s eponymous film; and blown away by the hippie hit Easy Rider.48 The opening credits, which featured Steppenwolf’s hymn “Born to Be Wild” and offered a positive depiction of hippie communal life and sexual freedom, were strongly imprinted on the minds of Greek youth. Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point was another hit, with its different handling of the same topic and its aggressive depiction of youthful rebellion. The film’s musical score familiarized the students with the sound of the Grateful Dead and the experimental rock of Pink Floyd.

In addition to being a means of drawing people closer together, films also encouraged reaching out to others. Cinema acted as a universal code and a means of “transmitting experiences”—the very experiences that Greek students were lacking. Angeliki Xydi remembers that the global repertoire of youthful defiance struck her through the documentary on the festival of Woodstock rather than through the reporting of the ’68 events, which for some reason passed unnoticed for her:

Various things that were taking place abroad reached me of course, but these too came through in strange ways, not very clearly. I do not remember, that is, being intrigued by May ’68. I should not lie about that, I discovered it later on. But I remember that I was impressed by Woodstock and that I saw the movie three times and that once I also dragged my mother. I wanted to bring her to the cinema and make her watch as well and understand what incredible things were taking place outside Greece. (Xydi, interview)

As Xydi’s remarks suggest, movies depicting the countercultural hippie scene of US youth and its political awareness incited an emotive response in the youthful Greek audience. In some instances, they generated instantaneous antiregime reflexes and were banned shortly after their release, thus acquiring legendary status. According to newspaper reports, screenings of American movies focusing on the rebellious youth were often followed by staged performances of the films’ subject matter in the streets. Roger Miliex, the director of the French Institute in Greece, recalls in his diaries: “Yesterday [30 November 1970], on their way out of a screening of the film Woodstock, which presents American youth pop festivals, two thousand young Athenians demonstrated in the center of the capital, shouting slogans against the police, while engaging in a confrontation with them.”49 This was an interesting phenomenon of reenactment and mimesis, whereby imitation became active interpellation.50

Leonidas Kallivretakis, a lower-school student during this period, recalls that the police ordered the closing of the doors before the Woodstock screening started, when the cinema was still half-empty. The result was that three thousand youths broke the cinema’s shutters and staged street battles with the police in the entire center of Athens, where many got beaten up, arrested, and had their hair cut.51 Greek youths were effectively displacing their opposition to the dictatorship by adopting the countercultural energy of Woodstock: “They were thus locating their struggle in (the context of) the 60s and dis-locating the abusive topos of the Greek dictatorship,” cultural theorist Dimitris Papanikolaou observes.52

These students were out of tune with the conservative Greek society’s attitude toward protest and counterculture. In an article published in the liberal newspaper Ta Nea the playwright Dimitris Psathas observed with revulsion: “The whole story was that some people wanted to get inside [the cinema] and watch the hippies and listen to the hippie songs, and the police were so scared by the possibility that our youth would also be seduced during the screenings by the frenzied action, the hysteria, the madness and the maniac crises of foreign youth—especially American—that at some point it thought of prohibiting the movie.” Later on in the article, Psathas continued in the same line:

The hysterical yelling of youths with their hair pulled out and of singers wearing long moustaches and beards, dressed in rags, covers the greatest part of the hippie movie. The whirling dervishes of hippie music beat themselves, pull their hair out, faint while singing, bleat desperately or holler. Maybe there are a few kids here in this sick category as well, among whom were certainly those silly chits with or without long hair who created the fuss last Sunday. The greatest part of our youth, however, is not being seduced by such rubbish.”53

Psathas’s comments are reminiscent of the moral panic that Western pop music was causing to officials in the Communist Bloc countries in about the same period.54

The day after Woodstock’s failed screening, Deputy Minister Georgalas visited Panteios School and made a speech “analyzing the aims and ideology of the Revolution of April 21.” Thereafter, a pro-regime medical student complained that “after three and a half years of efforts to detoxify the youth nothing ha[d] been achieved,” since “the distancing of the youth from other activities ha[d] pushed them deeper into hippyism.” Georgalas retorted that the youth was effectively detoxified, that the revolution had not yet used all its potential, and that the Woodstock incident was of no great importance. When the student mentioned the appearance of “three to five thousand anarchists,” Georgalas responded that “they weren’t anarchists but vivacious youths,”55 as it was probably too hazardous to label them otherwise. The interchange between the two, which included frequent references to “detoxification”—Georgalas’s favorite phrase to use when referring to the youth—and to anarchists and hippies, conveys the level of public debate on such matters and the negative charge with which these were loaded. It is noteworthy that at this time the Greek film comedies My Aunt, the Hippie [I Theia mou I Chipissa], A Hippie with Tsarouchia [Enas Chipis me Tsarouchia], and the theatrical play Hippies and Dirladas [Chipides kai Dirladades] enjoyed great success.56 This suggests the almost obsessive treatment of the subject of “hippies,” who were presented as grotesque, buffoonish, and as engaging in decadent cultural behavior. Equally interesting was the mainstream comedy Marijuana Stop (dir. Giannis Dalianidis, 1971), which adopted a strongly moralist tone in reference to the hippie counterculture, including drugs. Meanwhile, for dissident students hippieism connoted apolitical behavior, and drugs were identified with the underworld. They longed to be energetic rather than “stoned” and were getting their “fix” with adrenaline alone. “It seems that the [student] movement itself is like a drug,” former student leader Giorgos Vernikos concludes.57

However, the fact that Greece was a stage for hippieism contributed to locals’ being accustomed to freer habits, even if by 1971 the Holy Synod of the Greek Orthodox Church was calling all monks and nuns to pray for help because Greece was “scourged by the worldly touristic wave” and “contemporary western invaders.”58 The Economist further reported: “The Greeks, and not just the soldiers, don’t much like to see unwashed, barefooted and shabby youth sitting on the pavements in the center of Athens; nor do they have any respect for the dropouts hitch-hiking their way to Istanbul, Kabul and Goa without a drachma in their pockets. But they tolerate them.”59 In contrast to this article’s assertion, however, hippie attire gradually became fashionable in Greece; though drugs, yoga, and Zen Buddhism remained largely unknown, the spirit, the fashion, and the aesthetics of the hippies influenced everyday life, despite the fact that this was an otherwise authoritarian society and state. From the hippies came the trends of wearing bloomers and carrying handwoven bags. In addition, words and phrases like “flower power,” “make love not war,” “Twiggy,” and “Carnaby” penetrated the Greek vocabulary, and a multicolor, dreamlike psychedelic aesthetic was promoted by commercials.60

Connected to US counterculture was also Stuart Hagmann’s The Strawberry Statement (1970), which became the “cult” feature movie of the time. The film, based on a best-selling autobiographical account of a “college revolutionary,” chronicled the uprising of Columbia University students in 1968, exalting student activism and free love and rejecting university authoritarianism and police brutality.61 The most powerful point in the movie is its final scene, in which the barricaded students welcome the storming police while rhythmically chanting “Give peace a chance” before the action turns into brutal clashes and beatings. Myrsini Zorba remembers this as an explosion that the students “were internally ready for” (Zorba, interview). American Ambassador Henry J. Tasca reported in November 1970 about the screening of the film in Athens in a telegraphic fashion:

At several performances in at least two theaters, spectators in front rows stood up and shouted slogans. In one case groups shouted “1-1-4” which refers to article in former constitution promising equality to all citizens and was popular leftist street chant before coup. In another case disturbance was so great that police were called in to remove some of those causing disturbances, although as far as informant was aware no arrests were made. … Anti-regime slogans shouted during performance of feature film and accompanying newsreel, reported applause for episodes in which students beat up police and applause following glimpses of photographs of Robert Kennedy, Che Guevara and Mao Tse Tung.62

The enthusiastic responses that the film generated among students demonstrate their identification with the rebellious protagonists, confirming Laura Mulvey’s analysis that spectators in cinema blatantly project their repressed desires onto the performers.63

Apart from offering a space for mimicking foreign student movements, cinema halls—especially Alkyonis and Studio in Athens and Thymeli in Salonica—served as sites for information exchange and recognition. “In the movies everyone participated—police spies and left-wingers. They all watched along,” Thanasis Skamnakis remarks. “And you started getting to know faces, you saw them at the university, you saw them in the places where you hung out. And you started, you know, acquiring a visual connection to some people” (Skamnakis, interview). Thodoros Vourekas explains: “It became a nucleus; it became an agitational network between us, a very serious agitation, meaning that all the preparation was taking place there. Afterward I realized that most people who were acting in the student movement were also there” (Vourekas, interview). “The only issue was how to break the ice. This was the big issue,” Chrysafis Iordanoglou remembers. “How to break it, how to bring the people out, how to get to know each other.” (Iordanoglou, interview)

Figure 4.3. Projecting the repressed desire for freedom onto the screen. This was the 1970 advertisement for the film The Strawberry Statement, which dealt with student uprisings on US campuses. The film caused a sensation and was subsequently banned.

Cinema was a major advocate of common consciousness and a vehicle for self-education—“a whole internal world,” in the words of Iordanoglou. Greek students shared what media theorist Peppino Ortoleva has defined as the “eros of student movements for cinema” in the 1968 era.64 In her life story Angeliki Xydi recalled a day associated in her memory with Alain Resnais, highlighting the fact that hers was a generation of serious film buffs:

I remember that I saw Last Year in Marienbad the day in which I went for the first time to the Police Station for “a private matter.” This terrible piece of paper had arrived home calling me to go in for “a private matter.” It was 8 November 1972; I remember well because it was my name day. … They wanted to advise me of course in the way that they knew best. In any case, I was beaten black and blue that day, and I used to have very long hair back then, which I had just shampooed because it was my name day, it was beautiful. And they pulled it so hard [laughter] that it became like a wig and my head was aching terribly. But the evening was booked: in no case would we miss Last Year in Marienbad! [laughter]. (Xydi, interview)

This passage vividly depicts not only the repressive character of the regime even in the period of liberalization but also the strong connection between students and visual culture, with the latter offering a magical “window to the world,” a tool that could reverse and smooth over existing harsh realities. Therefore, I strongly disagree with eyewitness Kevin Andrews’s conclusion that “the result of these very few, uneasy and hesitant productions was that tired audiences could come away refreshed for yet one more tomorrow of boredom, anxiety, humiliation and eventually … indifference because it’s all too difficult.”65 Instead of acting as a two-edged sword, as Andrews suggests, art in general, and cinema in particular, proved to be a game-changer in the arena of protest. Film became the necessary companion of dissident students, facilitating the emergence of a militant social network and bringing culture and ideology together with artistic consumption and political agitation.

A place of recognition but also a lieu par excellence for voicing dissent was Salonica’s annual Film Festival. The screenings offered opportunities to assemble and became the definite meeting point for students in late September each year. It was state policy to promote and reward war epics about Greek bravery against either the German or Bulgarian aggressors during the Second World War. Since these films supposedly promoted the military virtues of Greek people, students tended to mock them. The darkness and the relative anonymity in Salonica’s large State Theater offered a perfect setting in which young people could vent their anger against the state-imposed movies and indirectly against the general political situation. According to filmmaker Grigoris Grigoriou “resistance … started from the spectators. Within the dark theater, during the screening hours, people applauded any scene that they considered as a hint against the Junta and wildly booed any scenes of anticommunist hysteria.”66 The pro-regime newspaper Eleftheros Kosmos reported with annoyance in 1970:

A group of immature youngsters during the screenings is booing whatever is not of their liking from an artistic or historical perspective. Hiding themselves within the darkness of the theater, these coward “revolutionaries” create a rude atmosphere that disturbs the other spectators who have gathered in order to take part in an artistic show and not a political meeting. Shouldn’t the police be present at the balcony … in order to bring the troublemakers back to order?67

Frequently, students opened a mock dialogue with the characters in the movies, asking them questions, responding to their lines, or just commenting. During one season, the Junta’s main film producer, James Paris, provoked the angry disapproval of students who exited in protest (“Shame on you!”) and the outburst of a young filmmaker who asked in a loud voice, “Is there no censorship for this?” Maria Mavragani remembers that it was an obligation to go to the theater balcony and shout. The students’ reactions tended to be overtly subversive, using irony and references to television commercials. Another film presented at the same festival was called Raging Youth [Orgismeni Genia] (dir. Gerasimos Papadatos, 1972), hinting at young people’s rebelliousness but clumsily presenting them as disoriented and vain. Students repeated slogans from television commercials in order to ridicule the dialogue, for example by starting to sing the tune of an advertisement called “Mr. Forte” when the film’s male protagonist demonstrated his toughness to his female counterpart. When he was informed by his girlfriend that she was pregnant, young people sang yet another common television commercial called “Now you know.” The reverberation of these commercials on behalf of dissident students points to the growing presence of a mass culture in Greece that was reinforced by a boost in mass consumerism by the regime.68 It also indicates a “situationist” mode of inverting and subverting the commercials’ initial meaning. During a moment of provocation, some youths shouted that they preferred watching the well-known porn star of the period, Kostas Gousgounis, to the film.69

During the screening of costume drama Hippocrates and Democracy [O Ippokratis kai I Dimokratia] (dir. Dimis Dadiras, 1972) at the thirteenth festival in September 1972, the character Hippocrates at one point said, “Then we have democracy,” and a student from the gallery asked, “Come again?” When Aspasia, Pericles’ wife, said, “There are greater sorrows awaiting us,” someone replied, “Us too, us too!”70 Here too, the “situationist” practice of mock dialoguing with the film undermined the spirit of official propaganda in which the movies were packaged, as well as the serious character and prestige of the festival as a whole. Historian Nikos Papadogiannis’s conclusion that this was a typical case of the survival of the practice of “dialogue with the screen”—a practice that dates back to the early days of cinema—is particularly pertinent.71

The movies offered an opportunity to express anger and dissatisfaction with the cultural priorities and aesthetics of the pro-Junta artists, as well as space to branch out. More importantly, the students made subtle references to the political situation. Little by little, and especially in 1973, their reactions in the gallery of the theater tended to be dictated by exclusively political criteria. A contemporary film critic characteristically complained in the autumn of 1973: “We understand the hunger of the audience for politics but we should not abandon our aesthetic standards entirely; a bad movie should not be praised just because there are glimpses of the Vietnam War or snippets of revolutionary songs and political slogans.”72 The fact that this kind of critique was not voiced by an “indignant” pro-regime intellectual demonstrates the growing politicization of public discourse at the time and the rising fear of critics that qualitative criteria would be eventually entirely overshadowed by cheap militantism. In any case, the dissident subculture that was established in Salonica Film Festival’s gallery during the Junta years was to be continued and even intensified in the years following the restoration of democracy in 1974.

Another privileged site of student communication and interaction was theater. From April 1967 through November 1969, the Colonels exercised direct state-imposed censorship over theater productions, making it “virtually impossible,” according to theater specialist Gonda Van Steen, “for stage companies to stage anything capable of being construed, or misconstrued, as a challenge to authoritarianism.”73 The initial ban on plays included a number of classical dramas deemed radical in their political ideas: Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus (revolutionary ideas and unbowed spirit of Prometheus), The Phoenicians (heretic in morality, nonbelief in religion, radical in politics), the subversive The Suppliants by Euripides, Ajax by Sophocles (lack of solidarity within the army), and above all Antigone (a standing incitement to civil disobedience to a military usurper who has taken over an enfeebled monarchy).74

Similarly, Aristophanes’ comedies, which are characterized by a general distrust of authorities and intellectuals alike, were banned; Lysistrata, with its ‘ithyphallic apparatus … and thrasonical soldiers on stage” was the worst offender.75 A foreign correspondent observed: “The censors consider that [these plays] contain ideas subversive to society, the King and religion, the three pillars of the regime instituted by the coup of April 21. They have substituted other plays regarded as ‘less dangerous to the public mind.’”76 The dictators treated Aristophanes as a nonconformist creator of irreverent artifacts, occasionally allowing his plays to be staged in an attempt to seem liberal and to offer “safety valves for venting dissent.” This trick failed miserably, however: because modern opposition plays were banned, Aristophanes provided the raw material for criticizing the excesses of the ludicrous dictators. It was up to the audience to identify the resemblances.77

By the early 1970s, the theater, like the cinema and the publishing world, had been somewhat liberalized. The softening of censorship allowed certain plays to return to the stage, even if norms of production and reception remained distorted. As the classical actress Anna Synodinou maintained in late 1972, one of the main reasons for the reemergence of artists, including playwrights and actors, was a growing concern that the new generation should not suffer from a cultural void—a statement similar to that made by Manolis Anagnostakis concerning books.78 In other words, artists like Synodinou wished that the previous generation of young people, which suffered the absence of any substantial cultural activity from 1967 to 1971, would be succeeded by one that would experience a renewed intellectual dynamism. In July 1972, Synodinou reemerged with Sophocles’ Elektra, and in early 1973 she went overtly political with the staging of Bertolt Brecht’s Antigone, in which she played the main role.

Soon, the subtext became more important than the apparent subject matter, and theater became a venue for dissent. The relationship between spectacle, text, music, and dance, and particularly the metatheatrical and extradramatic elements in the performances of politicized actors, contributed to that shift. By 1972, a number of directors, playwrights, actors, and actresses had devoted themselves to a theater that would reach the people and would communicate political messages. The journal Anoichto Theatro [Open Theater] (Athens, 1971) outlined this new role in an editorial published in its first issue in 1971 that defined “political theater.” The editorial concluded, in line with the reelaboration of tradition, that the correct knowledge of tradition “is always the starting point of every renewal.”79

In Athens, Karolos Koun’s Theatro Technis [Art Theater] basement performances were a focal point of the theater revival. The Theatro Technis’s particular approach to Attic comedy followed an idealized quest for pure folk culture. There followed productions of plays by Harold Pinter, Luigi Pirandello, Samuel Beckett, Eugène Ionesco, Jean Genet, and a single production of a Shakespeare play, Measure for Measure, which, according to Modern Greek scholar Peter Mackridge, was “a symbolic choice of play, with its central themes of justice and mercy.”80 To paraphrase sociologist José María Maravall’s conclusion about anti-Franco Spanish students at the same time, cultural deviance in the Colonels’ Greece was equivalent to political deviance: Beckett or Genet were as subversive as Lenin.81 For *Katerina, these performances contained “an allusory wink” that the trained student audiences of the time “could easily grasp” (*Katerina, interview). The Stoa Theater in Athens that was inaugurated in 1971 by Thanasis Papageorgiou and Eleni Karpeta also staged performances of political plays, such as Peter Weiss’s The Song of the Lusitanian Bogey. Drama teams like Stefanos Linaios’s Synchrono Elliniko Theatro [Contemporary Greek Theater] (Athens, 1970) performed plays that included political references, among them Goodnight Margarita, an adaptation of an old theatrical success based on a dramatic story during the German occupation. Nikos Bistis points out how this particular play helped to break down barriers and attract people to the student movement: “This was a classic performance of the bourgeois woman who passes over to the Left, she falls in love with a partisan. … All these spectacles helped people to be drawn to the Left” (Bistis, interview).

In Salonica, interest in theater blossomed tremendously under the Junta. The State Theater’s productions managed to attract more than three hundred thousand spectators per year to their performances, a great number of whom were students. As the state-controlled theater did not make a serious effort at transcendence in its repertoire, the growth seems indicative of a new form of group socialization and exchange through the theatrical ritual. Gradually, young people became increasingly preoccupied with theater. It became a widespread phenomenon, giving the students an important and influential role as consumers of cultural artifacts. The general director of the State Theater of Salonica, Georgios Kitsopoulos, stated in an interview with the pro-regime student paper O Foititis in late 1972 that he was seriously considering asking the opinion of the students, whom he considered a “class” on their own, before deciding to stage future plays:

The attendance of all these students in theater, the get-together, this lively participation, the notes with opinions and comments, have created a community. We have the perspective of having a closer relation to the class of youth, so that you should not be surprised—this is the first time I say this—if in the future we invite representative groups of youth before staging a play, in order to read it to them and let them give their opinion on the reasons why that play should be staged or not.82

Theater journals containing quite radical standpoints began to appear and were readily consumed. The most influential was Anoichto Theatro, a “monthly review of political theater” that contained articles by renowned left-wing intellectuals like Gyorg Lúkacs and traced international innovative developments such as the Living Theater in the United States. In an interview with Protoporia, the director of Anoichto Theatro, Giorgos Michailidis, stated clearly that “for us political theater means, first of all, opposition to any form of power.”83 Similarly, the journal Theatrika [Theater Issues] had as its motto a phrase by Eugène Ionesco: “All people that have the tendency to dominate others are paranoid.”

In late 1971, the theater scene started changing in Salonica as well, and interesting links were created between the literary scene and the Theatriko Ergastiri [Theatrical Workshop], which was run by students. A network of publishers, theater persons, and accommodating student groups was put into place. Bookseller and theater aficionado Kaiti Saketa recalls: “Filippos Vlachos of the Keimena publications came to Salonica. Salonica then was a distribution center for books, and we were in contact with all the publishers of Athens. So, where did he go when he came over here? Straight to the Theatriko Ergastiri.” At the same time new creative spaces were developed around theater, which facilitated the creation of new meaning. For a long time there was no student society that could accommodate dissident students; thus Saketa argues, “It was as if [students] had theater as their base” (Saketa, interview).

When the Theatriko Ergastiri brought Bertolt Brecht’s Man Equals Man in late 1972—a play full of references to everyday alienation, including the loss of innocence, the impossibility of communication, and the estrangement of the self (“You should forget about your opinions”)—the first performances took place in half-empty theaters. The theater columnist for Thessaloniki wondered, “How many—if not everybody in the theater room—should leave the Amalia Theater skeptical every night? It is an obligation, it is an injunction to get to know ourselves, to judge ourselves.”84 His moralist tone condemns the passive attitude of those who did not join the spectacles and who did not question themselves about the restrictions that were imposed on them on a daily basis.

The students redeemed themselves, however, proving to be some of the most sensitive receivers of theater and establishing a direct dialogue with the art form and its content. Brecht’s epic theater was much more influential on the young people of Greece than, for example, street theater, which did not manage to penetrate the country. The Theatriko Ergastiri turned to a more Greek-centered repertoire and in 1972 performed Greek playwright Mendis Bostantzoglou’s (Bost) Fafsta, a satire of bourgeois life and its linguistic anarchy. The workshop’s contributors articulated a desire to form a sort of “Greek Theater” by adopting a Greek repertoire and themes close to the Greek reality. The whole play is a sort of feast, in which the spectators themselves are involved in the end, in this way partaking in the spectacle in a dynamic way. The farce established a special relationship with the spectators by inviting them to interact—a practice that was about to become a standard feature in alternative theater performances over the following years.

Elefthero Theatro [Free Theater], the most remarkable of all of the theater groups of this period, was a collective created in 1970 by young actors and artists. With “living theater” features and a belief in Brechtean Verfremdung, the group decided to abolish the “director-dictator” in a symbolic antiauthoritarian move that resonated both with the repressive state of affairs in the country but also with a general radical tendency abroad: everything had to be the result of collective creation—in the tradition of Ariane Mnouschkine’s Théâtre du Soleil.85 Many of the Elefthero Theatro’s actors were members of the Maoist EKKE, not least because one of them, Giorgos Kotanidis, belonged to the organization’s leading group. As he notes in his memoirs, “In Europe a revolutionary ideology was being born and artists were in the vanguard. What better proof that theater, cinema and the revolution are part and parcel?”86 The collective’s political radicalism also inspired a stance critical of the “absolute spectacle” and a search for theater of contestation. Elefthero Theatro’s manifesto declared, with extraordinary frankness in its Marxist wording, that it was a group comprised of people under twenty-eight who detested bourgeois theatrical values.87 Just like with cinema, the idea here was that the spectators should be induced to think critically: “We oppose this passive attitude of the audience; its decline in front of a universe of heroes, divas, routine, lots of crying, lots of laughing. In contrast, we advocate a spectacle that keeps the audience alive, perceptive and happy.”88

The group was composed of graduates of the National Theater, some of whom were also enrolled as students in the universities of Athens or Salonica in order to retain their student status. This link with the student world was intensified through their close collaboration with EKIN, which included the staging of plays in the latter’s basement and the active role of some actors in its initiatives, and vice versa. The main contact was Elefthero Theatro’s leading actor, Nikos Skylodimos, himself a graduate of the prestigious Leonteios School and therefore a fellow student of some of those well-to-do youths who comprised the main circle of EKIN.

Elefthero Theatro had a spectacular debut when it staged John Gay’s Beggar’s Opera on 3 September 1970, in Athens. Kaiti Saketa remembers the same performance when it was staged in Salonica the following year: “This was a revolutionary act for Salonica, to have a play similar to Brecht’s Threepenny Opera staged at the Royal Theater, with innuendos, with pantomime against the dictatorship, things that were not stated clearly” (Saketa, interview).

Another breakthrough event for the Elefthero Theatro was its staging in 1971 and 1972 of Petros Markaris’s The Story of Ali Redjo [I Istoria tou Ali Redjo]. Being a clear indictment of the socioeconomic exploitation of the powerless have-nots by the powerful haves, the play was a succinct but unambiguous statement of social protest. The play included, among other things, the projection of a film that involved images of a tractor intercepted by shots of a tank. When the still of the tank covered the screen in the end, it became clear that it “pointed to the colonels and their military semiotics.”89 Playwright Markaris argued in an autobiographical text years later that the Elefthero Theatro’s staging of his play was the most collective and full-fledged resistance act in the field of the arts throughout the Junta years.90

In 1973, due to political differences the initial group of Elefthero Theatro broke up.91 Nonetheless, in the summer of the same year, and with some of the founders of the group persecuted or imprisoned for subversive political action, Elefthero Theatro made a direct statement regarding the current affairs and especially the dictators’ “controlled liberalization” experiment. With …And You’re Combing Your Hair […Kai Sy Chtenizesai], a production in the tradition of the Athenian epitheorisi (revue genre) and co-written by the group members together with left-wing playwrights Kostas Mourselas, Giorgos Skourtis, and Bost, it advanced the idea of abstention from the 29 July 1973 referendum for the abolition of the monarchy. The revue’s title (“You’re combing your hair,” meaning you are brushing your problems away) and the show’s poster and program (a collage with a finger pointing at the reader/audience over bodiless dancing legs), were a clear indictment of the entire society of indifference and social apathy.92 Since Elefthero Theatro members believed that the lifestyle and conformism of the Greek petty bourgeoisie were responsible for many of the country’s ills, several of the revue’s satirical numbers actually castigated issues such as the lower-middle-class obsession with socioeconomic mobility, its hypocritical stance regarding premarital sex, and its fascination with football and television.93

Figure 4.4. The avant-garde theater group Elefthero Theatro performing John Gay’s Beggar’s Opera in 1970. The group, which decided to abolish the director-dictator in a symbolic antiauthoritarian move, exemplified the fusion between politics and the arts. (Courtesy Giorgos Kotanidis)

By this point, audiences interpreted Elefthero Theatro’s productions as political commentary with great potential and impact.94 Rena Theologidou remembers the performances of …And You’re Combing Your Hair as “a revolution within the [Junta’s] ‘Revolution’—a real revolution”: “We used to go to [the theater of] Alsos every night, I could go on stage and play it. We knew it by heart, the dialogues, everything” (Theologidou, interview). Even though magazines of the time attest to the fact that the greatest and most enthusiastic part of the audience was comprised of students, the massive numbers of people that flocked to watch the show reveal that performance theater with a political edge was becoming mainstream.

By 1973, even mainstream companies, such as that of popular actress Jenny Karezi, staged political plays. Karezi, with her husband and fellow actor Kostas Kazakos, commissioned Iakovos Kambanellis to write a play that was performed in the spring of 1973 and was about to become one of the most popular anti-Junta theatrical events of the entire dictatorship period: Our Grand Circus [To Megalo mas Tsirko]. Academic and antiregime activist Giorgos Koumandos claims that the performances of this particular play “became massive political demonstrations, the biggest ones during the seven-year dictatorship—before the events at the Polytechnic.”95 The play was based on a series of historical vignettes that were filled with allusions and references to the Greek people’s suffering throughout the centuries from either foreign rule or domestic autocracy. In an alternative reading of Modern Greek history, Our Grand Circus paralleled authoritarian moments of the past to the rule of the Colonels and to US neocolonialism. Ostensibly in reference to the constitution granted by the first sovereign of Greece, the Bavarian King Otto, in 1844, characters in the play voiced the slogans “The people’s voice equals God’s rage” and “Constitution”—drawing an inescapable comparison to the savage violation of constitutional rule by the Colonels ever since 1967.