GAIGEL: A four-handed development of Bezique, with players seated opposite as partners. It can be played with a regular forty-eight-card pinochle pack, each suit ranking A, A, 10, 10, K, K, Q, Q, J, J, 9, 9. (Originally sevens were used instead of nines, but the latter are preferable today, as pinochle packs are common.)

Five cards are dealt to each player, and the next is turned up as trump, the pack being laid across it. Player at the dealer’s left leads any card to the first trick, and the others, in turn, play whatever they want, with no need to follow suit or trump. Highest card of suit led wins unless trumped, when highest trump wins. The winner draws the top card from the pack, adding it to his hand, and the other players do the same in turn. The winner then leads to the next trick.

When all cards have been drawn, the hands are played out, but now each player must follow suit and play higher if he can. If out of suit, he must trump if he can and also trump higher whenever possible. Partners pool their tricks, and cards taken by each team are counted according to the original schedule used in bezique and pinochle: Each ace, 11; ten, 10; king, 4; queen, 3; jack, 2. Last trick counts 10, so that 250 points are possible in play; but the first team to reach 101 must declare “out,” thereby winning the game. This is done by either partner knocking on the table before a new trick is played. Tricks already taken are then turned up and their points are counted, to make sure the claim is correct.

Other points may be gained during play by the following melds:

| Royal Marriage (K, Q of trump) |

40 points |

| Double Royal (K, K, Q, Q of trump) |

80 |

| Ordinary Marriage (K, Q of plain suit) |

20 |

| Double Marriage (K, K, Q, Q of suit) |

40 |

Such a meld can be made only by a player who has just won a trick, or by his partner if he failed to meld, and before the next card is drawn from the pack. Also, once a marriage is melded, another is not allowable in the same suit; hence to meld a double marriage, a player must lay down all four cards at once. When all cards have been drawn from the pack, no further melds are allowed, with this exception:

Five nines may be melded at any time for 101 points.

Thus, a player holding or drawing such a combination has only to show it and his team wins automatically.

Having won a trick, a player may exchange a dix for the turned-up trump. Usually, there is no score for this; but an optional rule allows 10 points for the exchange. In that case, the holder of the second dix can score 10 by simply showing it.

As already mentioned, a team must declare “out” as soon as it hits 101 or higher. This means that both partners must keep an exact count of the points their team takes, which is one of the intriguing features of the game. In most instances, the team that goes out is credited with winning a single game, but there are special cases where a team scores a “gaigel,” which counts as two games, in accordance with the following rules:

When a team scores 101 before the opposing team wins a trick.

If an opposing player knocks before his team has attained a total of 101; or:

If neither opponent knocks when their team has reached the required 101.

Before knocking, a player can ask to see the trick just taken, to check his mental calculation; but if he looks further back through either trick pile, his team forfeits the game and the opposing team scores a gaigel.

Special Note: Gaigel can be played by two, three, five, or eight players, each on his own, with the cards coming out evenly in both the deal and the draw. The more players, the more likely that the game will go into extra hands requiring fresh deals, before reaching the needed 101.

GARBAGE: An inelegant term for Five in One, this page.

GENTLEMEN’S AGREEMENT: A sophisticated form of Contract Bridge, this page, in which hands are abandoned unless the declarer has been doubled or has made a bid that will ensure game if successful.

GERMAN SKAT: This is Skat, this page, as originally played, including the bid of “Frage” (see Frog, this page) and other features no longer generally used.

GERMAN SOLO: A modern development of Ombre, this page, with four players, each on his own, using a thirty-two-card pack, ranking A, K, Q, J, 10, 9, 8, 7 in descending order, with these exceptions: The  Q, known as “spadilla,” is always the highest trump; the seven of the trump suit, called “manila,” is next; and the

Q, known as “spadilla,” is always the highest trump; the seven of the trump suit, called “manila,” is next; and the  Q, or “basta,” is always the third highest trump, the ace of trump being fourth; and so on, down to the eight. One suit, usually clubs, is known as “color” and takes precedence over the other suits when naming a trump.

Q, or “basta,” is always the third highest trump, the ace of trump being fourth; and so on, down to the eight. One suit, usually clubs, is known as “color” and takes precedence over the other suits when naming a trump.

Hence, each suit, when trump, would be ranked as follows:

| Clubs (Color): |

Spades: |

Hearts: |

Diamonds: |

Q 7 Q 7  Q Q  A K J 10 9 8 A K J 10 9 8 |

Q Q  7 Q A K J 10 9 7 Q A K J 10 9 |

Q Q  7 7  Q Q  A K Q J 10 9 8 A K Q J 10 9 8 |

Q Q  7 7  Q Q  A K Q J 10 9 8 A K Q J 10 9 8 |

Eight cards are dealt to each player, and, beginning at the dealer’s left, players bid for the privilege of naming trump and playing the hand on the following ascending scale:

Simple Game: Player names a trump suit after gaining the bid and calls for the holder of a nontrump ace to serve as his partner; or if the bidder holds all such aces, he calls for a king in a nontrump suit. Either way, the specified card is revealed by its holder only in the course of play. Bidder and temporary partner must take five of the eight tricks. Each then collects one chip from an opponent; or each pays one chip if they fail to make the bid. The trump named is any suit except “color.”

Simple in Color: The same game, but the bidder states that he will name color as the trump suit if he gains the bid. Bidder and partner each collect two chips from another player, or each pays two chips if they lose.

Solo: In this game, the bidder plays alone against the three other players, naming any trump suit except color. For taking five or more tricks, he collects two chips from each opponent; if he fails, he pays two chips to each.

Solo in Color: Played like regular solo, but in bidding the player states that he will name color as trump. If he wins his five tricks, he collects four chips instead of only two, or pays four if he loses.

Solo Tout: After gaining the bid, the player names any trump except color and must take all eight tricks to win, collecting eight chips from each of the other players if he does, or paying eight to each if he loses.

Solo Tout in Color: Played like solo tout, but with color named as trump during the bidding. Bidder collects sixteen chips if he wins, and pays sixteen chips if he loses.

Optional Nullo: By previous agreement a bidder may offer to play his hand face up—which is termed “ouvert”—without winning a trick. There is no trump suit, and if the bidder succeeds, he collects seven chips from each of the others, or pays each seven chips if he fails.

In any case, once the trump is known, play begins at dealer’s left, with highest card of suit led taking the trick unless trumped, then highest trump wins. Players must follow suit if possible and when out of suit can either play trump or discard from another suit. Winner of each trick leads to the next. In case all players pass, whoever holds the highest trump—the  Q—must show it and take the bid at a simple game or at simple solo. Once a player passes, he is out of the bidding from then on; but when a player gains the final bid, he can decide to play the hand at a higher level, assuming the additional risk involved.

Q—must show it and take the bid at a simple game or at simple solo. Once a player passes, he is out of the bidding from then on; but when a player gains the final bid, he can decide to play the hand at a higher level, assuming the additional risk involved.

GERMAN WHIST: A two-player form of Whist, this page, with the usual fifty-two-card pack. Each is dealt thirteen cards and the next is turned up as trump. The opponent leads and the dealer follows suit if able; otherwise discarding or trumping as in whist. Winner of trick draws the face-up card from the pack; loser draws the card beneath. The next card is turned up and the winner of the trick leads to the next trick. This continues until the entire pack is drawn, the remaining cards being played out. The player taking the most tricks collects the difference between his total and the loser’s.

Note: The card originally turned up continues to represent trump throughout the play of the entire hand.

GILE or GILET: A game too antiquated to deserve consideration beyond the fact that it was the ancestor of Brelan, Brag, and Poker.

GIN RUMMY: Originally known as “poker gin,” this has developed into perhaps the most popular of all two-handed games and is therefore worthy of consideration in its own right. Gin, as it is familiarly known, follows the pattern of Knock Rummy, this page, with cards ranking from king down to ace and with ten cards being dealt to each player, the purpose being to form matched sets of three or four cards of the same value (as J–J–J or 9–9–9–9) and sequences of three or more cards of the same suit (as  J–10–9 or

J–10–9 or  5–4–3–2–A). As in rummy, face cards (K, Q, J) count 10 points each; all others according to their spots.

5–4–3–2–A). As in rummy, face cards (K, Q, J) count 10 points each; all others according to their spots.

After dealing ten cards each to the opponent and himself, the dealer places the pack between them and turns up the top card beside it, as an upcard representing a discard pile. Opponent either takes the upcard to open play, discarding another card instead, or extends that privilege to the dealer, who in turn must either take the upcard or let the opponent open play by taking the top card of the pack. He may discard it, or keep it and discard some other card; in any case, a new upcard is now on display, and from then on each player in turn may take either the top card of the pack or the upcard, discarding as he chooses.

No melds are made until a player, after drawing, finds that he can reduce his “deadwood” or extra cards to 10 points or less. He can then knock on the table to end the play; after that, he melds his sets and sequences, makes a discard, and displays his unmatched deadwood.

As a simple illustration:

After a draw, Player X decides to knock on the strength of the following holding:

Player Y then melds whatever he can, with the added privilege of laying off extra cards on X’s melds, by extending sets or sequences. Assume that Y holds these ten cards:

In scoring, the player who knocked subtracts his points from the other player’s and credits himself with the difference, which goes into his column on a score sheet. In the above example, X would subtract his 4 points from Y’s 15, scoring 11 for X (15–4 11). The winner of the hand always deals the next hand, and the new score is entered in the proper column, continuing hand by hand until one player reaches 100 points or more, thereby winning game and receiving a bonus of 100 points. Both the box score and the bonus are doubled if a player wins every hand in the game, shutting out the other player. Each player receives a bonus of 25 points for each hand he won; and at the finish, one score is subtracted from the other to determine the margin of the victory.

11). The winner of the hand always deals the next hand, and the new score is entered in the proper column, continuing hand by hand until one player reaches 100 points or more, thereby winning game and receiving a bonus of 100 points. Both the box score and the bonus are doubled if a player wins every hand in the game, shutting out the other player. Each player receives a bonus of 25 points for each hand he won; and at the finish, one score is subtracted from the other to determine the margin of the victory.

That, however, is not all.

Any time a knocker melds his entire hand, so his count is 0, he “goes gin,” and the other player is not allowed to lay off on his hand. For going gin, he gains an additional 25-point bonus, even if the other player should meld all his cards as well, though that seldom happens, for by then the opposing player should have already knocked.

Frequently, however, a knocker may be tied or “undercut” by the other player. Here is an example of how that may happen:

Then, instead of being stuck with a count of 16 points (8 3

3 3

3 2

2 16), Y lays off

16), Y lays off  8 and

8 and  3 at the ends of X’s sequence (making it

3 at the ends of X’s sequence (making it  8 7 6 5 4 3), which leaves Y with only

8 7 6 5 4 3), which leaves Y with only  3 and

3 and  2 (3

2 (3 2

2 5). So Y receives 25 points, which is customary for equaling the knocker’s count, plus 3 points representing the margin of difference (8–5

5). So Y receives 25 points, which is customary for equaling the knocker’s count, plus 3 points representing the margin of difference (8–5 3) for a total of 28 points for the hand.

3) for a total of 28 points for the hand.

In short, the opposing player scores as if he had knocked and picks up 25 points above that. He also becomes winner of the hand and therefore deals the next hand.

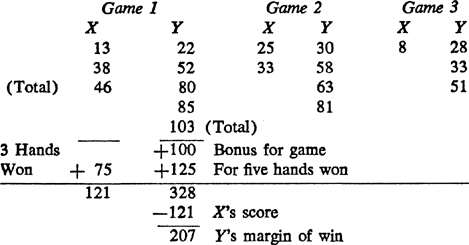

Hollywood Gin is a term applied to the popular practice of playing three (or more) games simultaneously, in overlapping style. A player scores his first winning hand in Game 1; his second winning hand in both Games 1 and 2; his third winning hand in Games 1, 2, and 3. From then on, all winning hands are scored in all three games until a player reaches 100 in any game, ending that game; but the others are played to their conclusions.

The following example will illustrate the precedure:

In the initial hand, Player X has 13 points, which is entered as his first hand in Game 1. In the next hand, X scores 25 points, so it is entered in both Game 1 and Game 2, thus:

| Game 1 |

Game 2 |

Game 3 |

| X Y |

X Y |

X Y |

13  |

25  |

|

38  |

|

|

Now, Player Y comes up with a winning hand of 22 points, which is his first win and therefore is entered only in Game 1:

| Game 1 |

Game 2 |

Game 3 |

| X Y |

X Y |

X Y |

| 13 22 |

25 |

|

| 38 |

|

|

In the next hand, Player X scores 8 points, which apply to all three games, 1, 2 and 3, as follows:

| Game 1 |

Game 2 |

Game 3 |

| X Y |

X Y |

X Y |

| 13 22 |

25 |

8 |

| 38 |

33 |

|

| 46 |

|

|

Player Y gets busy and wins four hands in a row, scoring 30, 28, 5, and 18, respectively, resulting in the following successive entries:

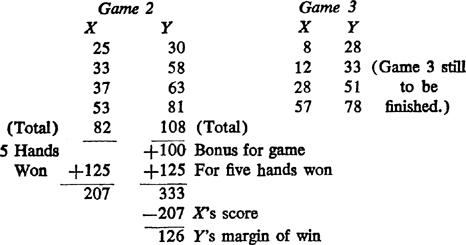

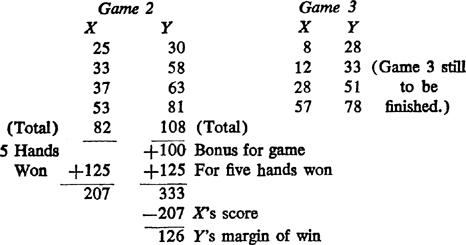

Now, X, who gained a nice head start, is at a disadvantage, since he can’t score in three games anymore, as Y did for two hands. Assuming that X wins three consecutive hands with scores of 4, 16, and 29, but that Y then undercuts X’s knock and comes through for 27. Games 2 and 3 would then stand:

Oklahoma Gin introduces one seemingly slight rule that utterly changes the pattern of play from that of standard gin. The rule is that the value of the upcard sets the number of points required for a knock during the ensuing deal. A face card or a ten makes no change in the 10-point minimum; while a nine, eight, or seven does not matter much. Lower values, however, greatly affect the play, and with an ace (1 point) the knocker practically has to go gin; in some circles, that is required. Due to the stepped-up play, game is usually set at 150, 200, or 250 (as preferred) with a bonus for winning the game set at the corresponding levels. Another rule often included is “spades double,” meaning that if the upcard is a spade all scores resulting from that hand are doubled.

Variants of Gin Rummy include the “round the corner” feature of standard rummy, in which an ace is both high and low, with a value of 15 points. In some circles, the opposing player is allowed to “lay off” on the knocker’s hand when he has “gone gin”; and a further rule may be introduced, eliminating any score for that hand if the opposing player reduces his count to zero, thus matching the knocker’s gin. Several forms of partnership gin rummy have been devised, along with versions of three-handed play, but gin is essentially a two-handed game, and other types of rummy are preferable when the accommodation of additional players becomes a matter of moment.

GLEEK: An old English three-handed game with a forty-four-card pack, lacking threes and twos, in which players were paid off for “gleek” or three of a kind, and “mournival,” or four of a kind, with only A, K, Q, J counting. Those four paid off as honors in a turned-up trump suit (as  A, K, Q, J), and the hand was finally played out as in Whist, this page, with a further score for tricks.

A, K, Q, J), and the hand was finally played out as in Whist, this page, with a further score for tricks.

GO BOOM: A juvenile game with two to six players utilizing a fifty-two-card pack ranking A, K, Q, J, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2. Each player is dealt seven cards, and, beginning at the dealer’s left, a player leads any card, which the others must match in suit or value. (Example:  9 is led; it could be followed by

9 is led; it could be followed by  J,

J,  9,

9,  3,

3,  9.) Anyone unable to play must draw up to three cards from top of pack until he can. After that, he can pass.

9.) Anyone unable to play must draw up to three cards from top of pack until he can. After that, he can pass.

Tricks are tossed aside as worthless, but whoever plays the highest card of the suit led has the privilege of leading to the next. The player who first disposes of all his cards wins the game.

GO FISH: This game is similar to Authors, this page, but simpler. With two or three players, each is dealt seven cards; with three to five players, each is dealt five cards. First player demands of any other, “Give me your nines,” or any other value he may name, provided that his own hand contains a card of that denomination. The player given the demand must hand them over if he has any, and the first player can make a new demand from anyone he chooses. But if a player cannot meet the demand, he says, “Go fish!” and the demander must draw the top card of the pack.

If it proves to be the value wanted, or fills a “book” by matching three cards of a value he already holds, he can continue. Otherwise, the call moves to the player on his left. This goes on until one player has laid down his entire hand in matched sets of books of four cards each, thereby winning the game.

GRAND: An intriguing composite game in which a fifty-two-card pack is dealt equally among four players, those seated opposite being partners. Beginning at dealer’s left, each player in turn may pass or make a bid in a multiple of five, going as high as 100. The high bidder then has several choices. He may decide to play a hand of Whist, this page, where he names the trump suit and leads to the first trick. For each trick that his team takes over the “book” of six, it scores 5 points. As an example: with a bid of “15” a team would have to take nine tricks but would score 5 points more for each extra trick. Taking all thirteen tricks would score 35 points, but also gives the team a bonus of 30, so a bid of “65” is possible. After the opening lead by the bidder, play proceeds exactly as in whist. If a team falls short, it is “set back” the amount of its bid and opponents score 5 points per trick for any they take over the book of six.

A bidder may decide to play a hand of no-trump, which in this game is termed “grand,” and is played just like whist but without a trump. In grand, each trick counts 9 points, with a bonus of 40 for “big slam,” so taking all thirteen tricks would score 103 points (7×9 40

40 103). Bids are still made in multiples of 5, hence a player bidding “20” could decide to go for ten tricks in whist (4×5

103). Bids are still made in multiples of 5, hence a player bidding “20” could decide to go for ten tricks in whist (4×5 20) or only eight in grand (2×9

20) or only eight in grand (2×9 18). Thus a choice of grand is not revealed until the bidder announces it, which adds to the zest of the game. A team scores what it makes in grand; if it falls short, it is set back the amount of the bid and opponents score 9 points for each trick they take over book of six.

18). Thus a choice of grand is not revealed until the bidder announces it, which adds to the zest of the game. A team scores what it makes in grand; if it falls short, it is set back the amount of the bid and opponents score 9 points for each trick they take over book of six.

As a further twist, a bidder can switch to Euchre, this page, with the suits ranking as in that game. Here, each player discards all but five cards from his hand, but no one can keep a trump lower than the eight. With a bid of “5,” a team must take three tricks; with a bid of “10,” four tricks; with a bid of “20,” all five tricks. Bidder leads to the first trick, and his team scores for all it takes; if short, it is set back the amount bid plus 20 points, but the opponents do not score. Possible losses would therefore be: 5 20

20 25; 10

25; 10 20

20 30; 20

30; 20 20

20 40.

40.

A player bidding “20” can decide to “play alone,” with the privilege of asking for his partner’s best card in exchange for one of his own, giving the opponents the same privilege. In this case, he scores 25 for taking all tricks, but is only set back the usual 40 if he fails. However, if he finds himself forced to bid “25,” he can do so, with the understanding that he must play a lone hand, with the exchange privilege if he chooses euchre. If he makes his bid, he scores 25; if he fails, he is set back 25 25

25 50.

50.

To illustrate this interesting situation: The trump suit consists of the jack (right bower), jack of the same color (left bower), followed by A, K, Q, 10, 9, 8 in that order. Assume that the bidder holds  J,

J,  J,

J,  A,

A,  Q,

Q,  K as his best possible hand, and names spades as trump. He decides to play a “lone hand,” discarding the

K as his best possible hand, and names spades as trump. He decides to play a “lone hand,” discarding the  K, in the hope that his partner’s best card is a spade, because a fifth trump will mean a sure win for the bidder.

K, in the hope that his partner’s best card is a spade, because a fifth trump will mean a sure win for the bidder.

However, his partner has no spade. His best card, though, is the  A, and upon gaining that, the bidder still has this chance: If the four remaining trumps,

A, and upon gaining that, the bidder still has this chance: If the four remaining trumps,  K, 10, 9, 8, are evenly divided between his opponents, the opponent gaining the other’s best card still will only have three trumps. So the bidder plays his bowers and ace, clearing the trumps, and takes the next two tricks with the remaining trump and the odd ace. But if one opponent holds

K, 10, 9, 8, are evenly divided between his opponents, the opponent gaining the other’s best card still will only have three trumps. So the bidder plays his bowers and ace, clearing the trumps, and takes the next two tricks with the remaining trump and the odd ace. But if one opponent holds  K, 9, 8 and the other holds the

K, 9, 8 and the other holds the  10, he can take the

10, he can take the  10 as his partner’s best card, giving him an odd card in return. Holding

10 as his partner’s best card, giving him an odd card in return. Holding  K, 10, 9, 8, he is sure to win the fourth trick with the

K, 10, 9, 8, he is sure to win the fourth trick with the  K and probably the fifth trick as well, thus setting the bidder back 40, if his bid was 20, or 50 if he was forced to bid 25.

K and probably the fifth trick as well, thus setting the bidder back 40, if his bid was 20, or 50 if he was forced to bid 25.

As if all this were not enough, anyone bidding up to 50 has still another option; namely, to declare Hearts, this page, as the game for that hand. The bidder leads, and if his team avoids taking any hearts, they score 50 points and the opponents are set back 1 point for each heart, or 13 in all. If the bidder’s team takes any hearts, it is set back the amount of its bid (which may be anything from 5 to 50) and 1 point for each heart. Opponents are also set back 1 point per heart.

Game is 100 points. If a team scores a big slam in grand, it wins the game, even though it may have a minus score at the time. If the dealer’s team reaches a score of 70, the player at dealer’s left can simply declare hearts as the game, with no other bids allowed. In any case, a “pass” by the first player indicates that he would like to play at hearts but is leaving the choice to his partner. If nobody bids, the dealer must take it at a minimum of “5,” choosing whatever game he regards as the least deadly.

Scoring involves other angles in grand. Often, when the bidding is spirited, opposing teams are set back so often that they frequently go in the hole and never climb out sufficiently to reach the goal of 100. So it is frequently decided to terminate play after a specified number of additional hands or at a certain time. Then the team with the highest score is credited with a final total of 100, just as if it had actually reached that figure. The losing team’s score is subtracted from 100 to establish the winner’s margin of victory. Examples: Team A goes out with 108 when Team B has only 45 points. Team A is credited with 100–45 55 points. But if Team A had only 48 points against B’s 45, Team A would still be credited with 100–45

55 points. But if Team A had only 48 points against B’s 45, Team A would still be credited with 100–45 55.

55.

However, that still is not final. Setbacks also figure in the score. Each time a team is set back, an “X” is marked beside the deduction. At the finish, each team’s setbacks are counted and the lesser deducted from the greater. The difference is multiplied by 10 and credited to the team with less setbacks. That margin is either added or deducted to playing score, as the case may be. Examples: In the case given above, if A had 5 setbacks and B had 7, the difference would be in A’s favor—2× 10 20—and that would be added to A’s score, giving A a winning margin of 75.

20—and that would be added to A’s score, giving A a winning margin of 75.

But if A had 12 setbacks—some very small—against B’s 7, the difference would be in B’s favor–5 × 10 50—which would be deducted from A’s playing score of 55, reducing A’s margin of victory to a mere 5 points. This is both a unique and important feature of grand, when settlements are made in chips or otherwise.

50—which would be deducted from A’s playing score of 55, reducing A’s margin of victory to a mere 5 points. This is both a unique and important feature of grand, when settlements are made in chips or otherwise.

Note: Detailed rules for Whist, Euchre, and Hearts will be found under those heads, and are followed in the play of grand, with the important exception that in grand the bidder always leads to the first trick.

GRAND DEMON: A variant of Fascination—Solitaire, this page.

GRUESOME TWOSOME: Poker. See this page.

GUTS: Poker. See this page.

Q, known as “spadilla,” is always the highest trump; the seven of the trump suit, called “manila,” is next; and the

Q, known as “spadilla,” is always the highest trump; the seven of the trump suit, called “manila,” is next; and the  Q, or “basta,” is always the third highest trump, the ace of trump being fourth; and so on, down to the eight. One suit, usually clubs, is known as “color” and takes precedence over the other suits when naming a trump.

Q, or “basta,” is always the third highest trump, the ace of trump being fourth; and so on, down to the eight. One suit, usually clubs, is known as “color” and takes precedence over the other suits when naming a trump. 7

7  7

7  1

1 4).

4).