BACCARA or BACCARAT: Chiefly a gambling casino game played with three packs of cards, values running from ace, as 1, up to 9, with tens and face cards rating 0. The banker sets a betting limit, and two players stake wagers against him individually. The banker deals cards alternately to the player on his right, then on his left, finally to himself, twice around, each getting two, face down. These are noted and if anyone has a total of 8 or 9, he turns up his cards as a “natural.” Example: 2 6

6 8, or 8

8, or 8 J

J 8. 4

8. 4 5

5 9, or 9

9, or 9 Q

Q 9. If the total comes to more than 9, the first figure is dropped; thus 9

9. If the total comes to more than 9, the first figure is dropped; thus 9 9

9 18 would be a natural 8.

18 would be a natural 8.

The banker pays off or collects from each player separately; and in the case of two naturals, 9 wins over 8, while with a tie, bets are off. If no one has a natural, cards remain face down, and each person can “stand” on those he has or call for one more card, which is dealt face up, his purpose being to come closest to 9 and thus become the winner. Example: Player A stands with 5 2

2 7. Player B, holding 3

7. Player B, holding 3 J, draws a 6, making 3

J, draws a 6, making 3 0

0 6

6 9. Dealer, holding 8

9. Dealer, holding 8 4, draws a 6, making 8

4, draws a 6, making 8 4

4 6

6 18

18 8. Dealer collects from A and pays off B.

8. Dealer collects from A and pays off B.

Other players may participate, betting along with A or B, as they prefer. Or they may place bets on a middle line, winning if both players win and losing if both lose. These bets, termed à cheval, are called off if one player wins and the other loses. Before the deal, a player may announce “Banco,” thereby betting the full amount of the bank and playing both hands for himself, with no other players allowed.

BANGO: A card game resembling “bingo,” utilizing a fifty-two-card pack, or preferably a double pack (104 cards) when up to a dozen players participate. Each contributes a specified number of chips to a pool or pot and is then dealt five cards in a face-up row. Cards are turned up singly from the pack, and whenever a player can match one in value (as nine for nine), he turns down his corresponding card or cards. The first player to turn down his entire row calls, “Bango” and wins the pot. With a tie, the pool is split; if no one wins, it is carried into the next pool.

Note: Instead of turning down cards, markers (such as odd chips) can be placed upon them.

BANKER AND BROKER: Also known as Blind Hookey, Dutch Bank, and Honest John.

The pack: The standard fifty-two cards running in descending values, A, K, Q, J, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2. Suits play no part.

Number of players: Up to a dozen.

Deal and Play: The dealer, as “banker,” cuts the pack into four, five, or six piles. Players place tokens alongside whatever piles they want, leaving one vacant for the banker, who turns the piles face up, beginning with his own, showing the bottom cards. For every card of higher value, the banker pays off chip for chip. He collects from all that his card matches or exceeds in value. By rotating the deal after each hand, the banker’s advantage can be spread equally among the players.

BANK NIGHT: See this page.

BARNYARD: A variant of Menagerie, using names of fowls and domestic animals. See this page.

BASEBALL: A form of wild-card Poker. See this page.

BASSET: An early form of Faro, popular in Venice in 1700. See Faro, this page.

BATTLE ROYAL: Three-handed Gin Rummy (this page) allowing each player to take up either of the two previous discards. When a player knocks, the others, in turn, lay off on his hand.

BEAST: A now obsolete forerunner of Loo and Nap.

BEAT YOUR NEIGHBOR: A form of Stud Poker. See this page.

BEDSPRINGS: A modern variant of Poker, this page.

BEER PLAY: Another name for Bierspiel. See Rams, this page.

BEGGAR MY NEIGHBOR: An automatic but exciting two-player game with each holding half a fifty-two-card pack in a face-down pile. They deal cards alternately from the top of their respective piles into a center heap, face up, as long as only spot cards appear. But when one turns up a picture card (or ace), it calls for his opponent to deal cards as follows: jack, 1; queen, 2; king, 3; ace, 4. If all are spots, the original player wins the center heap, gathering it as it stands and placing it face down beneath his pile. But if the opponent turns up a picture card (or ace), it takes precedence and the original player must meet the new demand on the same terms; and so on.

(Example: A deals a queen, calling for two cards. B deals a spot, then an ace, calling for four. A deals spot, spot, jack, calling for one. B deals a spot and A wins the center heap.)

The winner starts the play anew, and it continues until one player has “beggared” his opponent by taking all his cards, thus winning the game. As many as six players can participate, all being given nearly equal piles; or still more, if a double pack of 104 cards is used. All deal in rotation to the center pile, and when one runs out of cards, he drops from the game and the next player continues where he left off. This eventually narrows the game to two players, as in its simple form.

BELEAGUERED CASTLE: A type of Solitaire. See this page.

BELOTTE: A French game similar to Klaberjass, described under that head. See this page.

BEST FLUSH: A form of Poker in which only flushes or partial flushes count. See this page.

BET OR DROP: Draw Poker, with the rule that a player must bet or pass up the hand. See this page and this page.

BETROTHAL: A form of Solitaire, this page.

BETTY HUTTON: A form of Poker, this page.

BEZIQUE: This forerunner of Pinochle requires a sixty-four-card pack with two of each value in each suit, ranking A, A, 10, 10, K, K, Q, Q, J, J, 9, 9, 8, 8, 7, 7, with each seven of trump serving as a dix, with a value of 10 points. In the original two-handed game, the play and melds are as follows:

Only eight cards are dealt to each player (usually three, three, two) with the next turned up beneath the pack to represent trump. In play, the leads and draws are the same as in two-handed pinochle, with no need to follow suit or trump until the last eight tricks. However, in bezique, only aces and tens—called brisques—are counters, at 10 points each, with 10 for the last trick, making 170 points taken in play.

In melds, there is a marked difference from pinochle, namely:

With each player starting with a hand of eight cards, the opponent leads any card and the dealer plays whatever he wants. The highest card of the suit led takes the trick unless a plain suit lead is trumped. The winner of each trick may lay his melds face up in front of him, but can score only for one. Others must wait until he wins later tricks. For example, a player lays down:

K Q

K Q  J

J  J

J  J

J  J

J

He declares four jacks for 40 points and is free to play any jack except the  J, which he retains in order to meld a bezique (

J, which he retains in order to meld a bezique ( J

J  Q) after winning another trick. After winning a third trick, he can declare the spade marriage (

Q) after winning another trick. After winning a third trick, he can declare the spade marriage ( K Q) for a further score.

K Q) for a further score.

The winner of each trick adds the top card of the pack to his hand and the loser takes the next. The winner leads either from his hand or his meld, and the loser plays accordingly. When all the pack has been drawn, a player must follow suit and take the trick if possible; if out of suit, he must take the trick with a trump if he has one; otherwise, he plays from an odd suit. At the finish, brisques and last trick are counted at 10 points each and added to each player’s individual melds.

As in pinochle, a player can meld a royal marriage for 40 points and later add the A, 10, J for a trump sequence at 250. But once a meld is made, none of its cards may be used toward another meld in the same class. Thus, after melding four aces for 100, the remaining four aces would have to be melded as a group to score 100; and so on.

A player melding a bezique ( Q,

Q,  J) for 40 points can add another such combination to score 500 for double bezique (

J) for 40 points can add another such combination to score 500 for double bezique ( Q Q,

Q Q,  J J), but if forced to declare both simultaneously, he would not score 40, but only the 500 for double bezique. Similarly, he might lose 40 for a royal marriage if forced to meld it as part of a sequence.

J J), but if forced to declare both simultaneously, he would not score 40, but only the 500 for double bezique. Similarly, he might lose 40 for a royal marriage if forced to meld it as part of a sequence.

Otherwise, the melding rules of bezique are more liberal than in pinochle. A player does not have to add a card from his hand in making a fresh meld, but may, on occasion, declare a combination already showing on his board. Example: A player melds  J,

J,  J,

J,  J,

J,  J for 40. He retains the

J for 40. He retains the  J while playing other jacks. Later, he melds

J while playing other jacks. Later, he melds  Q,

Q,  Q,

Q,  Q,

Q,  Q for 60. He wins a trick a few plays later and points to the

Q for 60. He wins a trick a few plays later and points to the  J,

J,  Q combination still on the board, announcing it as a 40-point meld for bezique.

Q combination still on the board, announcing it as a 40-point meld for bezique.

Each hand in bezique can constitute a game, but it is preferable to set a cumulative total for game, such as 1000 points; or better, 1500, due to the fact that a player scoring a double bezique (500) would have too great an advantage in a 1000-point game.

Note: Since bezique is seldom played today, it has been described as though it were an offshoot of the more popular pinochle, rather than as the parent game. Bezique itself has variants, the simplest being to disregard the dix as a scoring factor and to begin the play without turning up a trump. All suits are plain until one player melds a marriage, which is declared a royal, thereby making its suit trump.

Bezique is sometimes confused with sixty-four-card pinochle, which utilizes the sixty-four-card bezique pack but is played and scored exactly like pinochle, except that each player is dealt sixteen cards and the seven of trump serves as the dix, instead of the nine.

RUBICON BEZIQUE: This introduces some radical and intriguing departures from the original two-handed game. A 128-card pack is used with four of each kind, ranked A, 10, K, Q, J, 9, 8, 7 as usual. Nine cards are dealt to each player, but no trump is turned up, hence there is no dix. Instead, the first marriage declared by either player establishes the trump suit.

As a preliminary, if either hand is entirely devoid of court cards (K, Q, J), the player displays it face up and scores 50 points for a carte blanche. If he fails to draw a court card after the first trick, he scores another; and the same applies to successive tricks until a court card does appear, after which the player can make no more such declarations.

Other declarations or melds are as follows:

| Royal marriage |

40 |

Plain marriage |

20 |

| Trump sequence |

250 |

Any sequence |

150 |

Bezique ( Q, Q,  J) J) |

40 |

Double bezique |

500 |

| Triple bezique |

1500 |

Quadruple |

4500 |

| Any four jacks |

40 |

Any four queens |

60 |

| Any four kings |

80 |

Any four aces |

100 |

Playing and drawing proceed as in the standard game of bezique, but brisques (each A or 10) do not count, unless the score is tied, in which case the brisques are counted to determine the winner. The player taking the last trick scores 50 points; but earlier in the game, however, we encounter the somewhat fantastic departure from the normal that gives rubicon bezique its decisive individuality:

After playing a card from a meld, the player may add another card to form a new meld, with another score. Example: From a meld of  Q,

Q,  Q,

Q,  Q,

Q,  Q, for 60 points, he plays the

Q, for 60 points, he plays the  Q and wins the trick. He promptly lays down a

Q and wins the trick. He promptly lays down a  Q for another 60 points and plays a

Q for another 60 points and plays a  Q, winning that trick also. So he lays down a

Q, winning that trick also. So he lays down a  Q and calls it another 60 points.

Q and calls it another 60 points.

Even more wonderful, he can meld a  K Q as a marriage for 20 points; then another

K Q as a marriage for 20 points; then another  K Q for 20 points; and following that, he can interchange the kings and queens, scoring 20 points for the first

K Q for 20 points; and following that, he can interchange the kings and queens, scoring 20 points for the first  K and the second

K and the second  Q; then 20 points again for the second

Q; then 20 points again for the second  K and the first

K and the first  Q. However, once a king and queen have been declared and scored as part of a sequence (A, 10, K, Q, J), neither can be used toward a new marriage.

Q. However, once a king and queen have been declared and scored as part of a sequence (A, 10, K, Q, J), neither can be used toward a new marriage.

With a bezique, a player can meld a  J and

J and  Q for 40 points, then later play a member of the pair (as the

Q for 40 points, then later play a member of the pair (as the  J) and form another 40-point bezique by adding another, identical card, in this case, a

J) and form another 40-point bezique by adding another, identical card, in this case, a  J, This can be repeated with either member of the pair. However, unless nearly all the cards have been drawn from the pack, or needed cards have already been played, a player melding

J, This can be repeated with either member of the pair. However, unless nearly all the cards have been drawn from the pack, or needed cards have already been played, a player melding  J,

J,  Q would do better to hold another

Q would do better to hold another  J on the chance of drawing a

J on the chance of drawing a  Q, when he could add them to those already melded, forming a double bezique (

Q, when he could add them to those already melded, forming a double bezique ( J J,

J J,  Q Q), for 500 points.

Q Q), for 500 points.

Similarly, he could go for triple bezique (1500) and quadruple bezique (4500) by adding new combinations to those still on the board, making a total of 40 500

500 1500

1500 4500

4500 6540. But such an opportunity would be rare indeed. So many combinations are possible in this game that a player usually must choose those that are most profitable or most expedient, rather than try to cash all his holdings or bank on potentials.

6540. But such an opportunity would be rare indeed. So many combinations are possible in this game that a player usually must choose those that are most profitable or most expedient, rather than try to cash all his holdings or bank on potentials.

Since rubicon bezique is essentially a high scoring game, careful score must be kept throughout the hand, which is regarded as a complete game. In declaring a meld, a player may announce a future meld by laying down the necessary cards; but they serve only as a reminder, as the future meld cannot be scored until he has taken another trick.

Example: A player can lay down four queens, including  Q, and with them a

Q, and with them a  J and

J and  K, declaring, “Sixty for queens,” then adding, “With forty to score for bezique [

K, declaring, “Sixty for queens,” then adding, “With forty to score for bezique [ Q,

Q,  J] and twenty to score for a marriage [

J] and twenty to score for a marriage [ K Q].” The three cards thus involved would have to remain on the board until the player takes another trick, then the bezique could be counted and he could play the

K Q].” The three cards thus involved would have to remain on the board until the player takes another trick, then the bezique could be counted and he could play the  J. But he would have to retain the

J. But he would have to retain the  K Q until after taking another trick, in order to count the marriage.

K Q until after taking another trick, in order to count the marriage.

A player should continue to announce such futures after each trick, until he actually scores them, just to keep the record straight; but he can abandon any futures if need be. Players are also allowed to count the remaining cards in the pack, as the draw nears the end, as after that no more melds can be declared. During the play of the last nine tricks, a player must follow suit and take the trick if he can; if out of suit, he must trump if possible.

Scoring follows a special pattern in rubicon bezique. Each deal is regarded as a game in itself, and the player with the higher score wins the game, but brisques are not usually counted. Scores are reckoned in hundreds, so if the dealer should total 1420 and the opponent 1150, the final scores would be 1400 and 1100, giving the dealer a margin of 300 points, to which he adds 500 as a bonus for winning the game, for a final margin of 800 points. If the difference is less than 100 points, the winner is credited with 100 plus 500 for game, or 600 points in all.

However, if a loser fails to reach the 1000 mark, he is said to be “rubiconed” and the winner adds the loser’s points to his score, as though he had taken all the tricks, and is credited with 320 for the brisques that they contain (sixteen aces and sixteen tens at 10 points each). Also, the winner is given a double bonus, scoring 1000 for winning the game. As an example: Opponent scores 1120 and dealer scores 470. Opponent counts his 1100 plus dealer’s 400, with 320 for brisques and 1000 for game: 1100 400

400 320

320 1000

1000 2820, or 2800, as customarily reckoned.

2820, or 2800, as customarily reckoned.

If a loser’s score is close to 1000, he is allowed to count his own brisques to avoid being rubiconed. Assuming that his meld comes to 860, and he finds that he has taken sixteen brisques for 160 points, his total would be 1020, giving him the needed 1000. That would be deducted from the winner’s score, which in this case would include the winner’s brisques, since the loser was allowed to count his own.

Similarly, brisques should be checked when scores are close enough for them to decide the issue. Example: Dealer scores 1160; opponent, 1070. Brisques are counted and dealer has only ten against opponent’s twenty-two. Final score: Dealer 1160 100

100 1260. Opponent 1070

1260. Opponent 1070 220

220 1290. Opponent becomes the winner.

1290. Opponent becomes the winner.

SIX-PACK BEZIQUE: This is the modernized form of rubicon bezique, played with three bezique packs of sixty-four cards each, making a total of 192 cards. This is the equivalent of six piquet packs of thirty-two cards each—valued A, 10, K, Q, J, 9, 8, 7—hence the term “six-pack bezique.” The original version was called “Chinese bezique” and was simply rubicon bezique with more cards, which made it somewhat unwieldy, but new features were added later, bringing the game up to its present standard.

There are two players, as in rubicon bezique, but each is dealt twelve cards. This makes it more difficult to receive a hand devoid of kings, queens, and jacks; hence a carte blanche, as such a hand is called, scores 250 and can be repeated as long as the player continues to draw cards of other values. In addition to the melds listed under rubicon bezique, the following are included in the six-handed game:

| Four trump aces |

1000 |

| Four trump tens |

900 |

| Four trump kings |

800 |

| Four trump queens |

600 |

| Four trump jacks |

400 |

Play proceeds exactly as in rubicon bezique, with the first marriage melded establishing the trump suit, a very important feature, because of the bonus counts just listed. There is no count whatever for any brisques—aces and tens—that are taken during play, but the player taking the last trick scores 250 points in this game. A dix (seven of trump) has no meld value. Each deal is a game, as in rubicon bezique, but the winner scores 1000 points in six-pack play. That is added to the winner’s high score, and the loser’s low score is deducted to determine the margin of victory in terms of hundreds, just as in rubicon bezique.

Also, the loser can be rubiconed if he fails to score 3000 or more. In that case, the winner adds the loser’s score to his own to determine the winning total. There is no bonus for brisques as in rubicon bezique, because, as already mentioned, they do not figure at all.

An interesting preliminary may be introduced in six-pack bezique, namely: Before dealing, the dealer tries to lift exactly twenty-four cards from the top of the pack; while his opponent, watching the action, tries to guess the actual number lifted. If the dealer is right, he scores 250 points; if the opponent is right, he scores 150. This is not recommended, as it has nothing to do with the actual play of the game.

Another optional rule is that the same trump cannot be declared in two successive deals; hence a marriage in the old trump, if melded first, is scored as an ordinary marriage. This rule, too, is dubious, since each deal constitutes a game in itself, and therefore it is hard to see why one should have a bearing on the next.

In some circles, a meld of the  Q

Q  J is scored as a bezique only when spades are trump. Instead, the

J is scored as a bezique only when spades are trump. Instead, the  Q

Q  J is used when diamonds are trump; the

J is used when diamonds are trump; the  Q

Q  J when clubs are trump; and the

J when clubs are trump; and the  Q

Q  J when hearts are trump. This means that beziques cannot be melded in any form until a trump has been declared, which at times can have a very marked effect upon the play. This rule, too, is of questionable value, as it tends to complicate the game; hence like the other options, it should be decided upon beforehand.

J when hearts are trump. This means that beziques cannot be melded in any form until a trump has been declared, which at times can have a very marked effect upon the play. This rule, too, is of questionable value, as it tends to complicate the game; hence like the other options, it should be decided upon beforehand.

EIGHT-PACK BEZIQUE: Almost identical with the six-pack game, this requires a fourth bezique pack of sixty-four cards, or in other terms two more piquet packs of thirty-two cards each. In all, this means a total of 256 cards, so the two players are each dealt fifteen cards each. All scoring is the same as in six-pack bezique, but with these additions to the schedule:

| Quintuple pinochle |

9000 |

| Five trump aces |

2000 |

| Five trump tens |

1800 |

| Five trump kings |

1600 |

| Five trump queens |

1200 |

| Five trump jacks |

800 |

Scores are much greater due to more cards in the hands as well as in the pack, so the loser is rubiconed unless he scores 5000 points or more. As in all forms of rubicon bezique, the winner does not have to reach that level, the whole burden being on the loser.

Summarizing games of the rubicon type, the big feature is that of “repeating” melds or declarations by simply playing one card and adding another such card to the existing meld. This can be done with any form of meld, including beziques; but in that case, particularly, good judgment must be exercised. A player can meld a  Q and

Q and  J for 40 points; then play the

J for 40 points; then play the  Q and put a second

Q and put a second  Q with the

Q with the  J for another 40; then play the

J for another 40; then play the  J and put a second

J and put a second  J with the

J with the  Q for still another 40. But all those would be “single” beziques, so he would do far better to hold onto his second

Q for still another 40. But all those would be “single” beziques, so he would do far better to hold onto his second  Q until he acquires the second

Q until he acquires the second  J, when he could lay both with the “single” bezique on the board and declare a “double” bezique for 500 points. The same applies to triple, quadruple, and quintuple beziques.

J, when he could lay both with the “single” bezique on the board and declare a “double” bezique for 500 points. The same applies to triple, quadruple, and quintuple beziques.

BID EUCHRE: A name originally applied to the game of Five Hundred. See this page.

BID WHIST: A fast-moving form of Whist dependent on a special bidding feature. Described under Whist, this page.

BIERSPIEL: A variation of Rams, described under that head. See this page.

BIG FORTY: A variant of Lucas. See this page.

BIMBO: Double-handed High-Low Poker. See this page.

BINOCHLE: A former term for Pinochle, applicable to the old-style game; not the more modern versions. See this page.

BISLEY: A type of Solitaire. See this page.

BLACK JACK: A name given the game of Hearts when the  J is counted as a 13-point penalty card instead of the

J is counted as a 13-point penalty card instead of the  Q. See Hearts, this page.

Q. See Hearts, this page.

BLACKJACK: This highly popular game is basically the same as Twenty-one, but the term blackjack usually applies to the sociable or private form, with twenty-one referring to variations played at gambling casinos. In sociable blackjack, a standard fifty-two-card pack is used with suits disregarded and each card valued numerically only: ace, 1 or 11; face cards (K, Q, J), 10 each; others according to their spots, 10 down to 2.

One player acts as banker and deals a single card face down to each player, including himself. Each looks at his card and bets up to an agreed limit. The dealer does not bet but may double the amounts; if he does, any other player may redouble individually, but if any player is unwilling to go double, the dealer wins that player’s original stake. Each player is then dealt a second card face up, dealer included. If a player holds an ace (11) and a face card or a ten (10), it is a “natural” 21 and he collects twice the amount of his bet from the dealer, unless the dealer also has a natural. In that case, the dealer collects the amount bet by that player, or twice the amount bet from any player who does not have a natural.

If the dealer has no natural, he pays off any players who do have, then, beginning with the remaining players at his left, he deals cards face up, one by one, as that player calls for them. The player’s aim is to hit a total as close to 21 as possible without going over, so he declares that he will “stand” when he thinks he has enough cards, or if he wants more, he says, “Hit me.” If he goes over 21, his hand is a “bust” and he must turn it down, while the dealer collects the bet.

The dealer does the same with the next remaining player and so on, with up to a dozen in the game. Any who stand wait while the dealer draws cards for himself; if he goes bust, he pays each standing player the amount he bet. But if the dealer stands, all cards are turned up and the dealer pays off all players with totals higher than his own, but collects from any that are less or the same. The rule is that ties favor the dealer, exactly as with naturals.

Despite this advantage, a dealer risks heavy losses if he goes bust a few times in a row. So in some circles the deal simply moves around the board hand by hand, as in other card games, each new dealer shuffling the pack and having it cut before he deals. But the more popular rule is for all players to “cut for low” to determine the original dealer, who retains that privilege but with the option of selling it to the highest bidder before or after any hand. However, if he deals a natural to another player and is unable to match it, the dealing privilege goes to that player beginning with the next hand. With more than one claimant, the player nearest the dealer’s left takes precedence.

Under that rule, a standard procedure is for the new dealer to shuffle the pack, have it cut, then turn up the top card—say the  8—and “burn” it by placing it face up at the bottom of the pack. He then deals a regular round of blackjack, but in gathering up the dealt cards, he places them face up beneath the burnt card and deals another round from the top of the pack, as is. He continues thus with the next round until he comes to the burnt card (

8—and “burn” it by placing it face up at the bottom of the pack. He then deals a regular round of blackjack, but in gathering up the dealt cards, he places them face up beneath the burnt card and deals another round from the top of the pack, as is. He continues thus with the next round until he comes to the burnt card ( 8), when he pauses in the deal to turn the pack face down, shuffle it, have it cut, burn another card, and continue the deal from the point where it was interrupted. However, at the beginning of any round in which the burnt card is soon due to appear, the dealer may turn all cards of the pack face down and shuffle as with the original deal.

8), when he pauses in the deal to turn the pack face down, shuffle it, have it cut, burn another card, and continue the deal from the point where it was interrupted. However, at the beginning of any round in which the burnt card is soon due to appear, the dealer may turn all cards of the pack face down and shuffle as with the original deal.

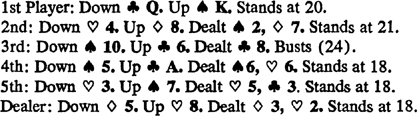

Here is a typical hand in a blackjack game with six players.

If the fourth player had counted ace 11, he would have gone bust on the

11, he would have gone bust on the  6, so he counted ace

6, so he counted ace 1 and with 5

1 and with 5 1

1 6

6 12 called for another card.

12 called for another card.

The dealer, after drawing the  3, had only 16 (5

3, had only 16 (5 8

8 3). He figured the first player for 18, 19, or 20. The second player has 17 showing in face-up cards (8

3). He figured the first player for 18, 19, or 20. The second player has 17 showing in face-up cards (8 2

2 7); the fourth, 13 (1

7); the fourth, 13 (1 6

6 6); the fifth, 15 (7

6); the fifth, 15 (7 5

5 3), making the dealer’s 16 a very probable loss on all three counts. So the dealer drew one more, the

3), making the dealer’s 16 a very probable loss on all three counts. So the dealer drew one more, the  2, and banked on his 18 (5

2, and banked on his 18 (5 8

8 3

3 2) to match at least two of the rival hands, which it did. So the dealer paid off the first and second, while he collected from the fourth and fifth.

2) to match at least two of the rival hands, which it did. So the dealer paid off the first and second, while he collected from the fourth and fifth.

Certain special hands are customarily played in blackjack. These include:

Splitting Pairs: If a player’s first two cards, down and up, are of the same denomination, as two kings, or any other pair down to two deuces, he can turn the first card up and call each member of the pair the upcard of a separate hand, betting equally on each. The dealer then gives him two downcards, one for each hand; and the player draws or stands on each, playing them on their individual merits. With a pair of cards valued at 10 each, or better still a pair of aces, the lucky player has twice the usual chance of making a natural.

Doubling Down: If a player’s first two cards total exactly 11, as 9–2, 8–3, 7–4, 6–5, he can turn up his first card and call for another downcard to replace it, provided he also doubles his bet. He must then stand on those three cards, playing them as a regular hand. Since there is about one out of three chances of making 21 by this procedure, many players regard it as an ideal opportunity to double a bet. By agreement, players may be allowed to double down on a total of 10 (as 2–8, 3–7, 4–6, 5–5) or a total of 9 (as 7–2, 6–3, 5–4). In the case of 9, if the player is dealt a 2 as his new downcard, he can turn it up, add it to his total, making 11, and demand another downcard.

Payoff Hands: By agreement, a player holding any of the following combinations may turn up his downcard and demand an instant payoff, regardless of whether the dealer can later match or exceed his total:

Any five cards that do not exceed 21 (as 3–3–4–A–9 or 6–2–3–4–5). Player receives double the amount of his bet. For each additional card, another double (as 3–5–2–2–3–4, four times). (Or 5–3–3–A–A–2–6, eight times.) (Or 2–3–2–4–4–2–A–3, sixteen times.) A total of 21 composed of a 6, 7, and 8 pays double the bet. A total of 21 composed of three 7’s pays triple the bet.

BLACK LADY: A form of Hearts in which the  Q (or Black Lady) counts 13 points against the player taking it. Known also as Black Maria, Black Widow and by other names. See this page.

Q (or Black Lady) counts 13 points against the player taking it. Known also as Black Maria, Black Widow and by other names. See this page.

BLACK MARIA or BLACK WIDOW: Other names for Black Lady. See this page–this page.

BLACKOUT: Another name for the game of Oh, Hell! See this page.

BLIND ALL FOURS: A name originally given to the game of Pitch. See this page.

BLIND AND STRADDLE: The early form of Blind Opening. See this page.

BLIND CINCH: A variation of Cinch, this page.

BLIND EUCHRE: Simple Euchre with a two-card widow. See this page.

BLIND HOOKEY: A popular name for Banker and Broker, this page.

BLIND OPENING: A form of Poker in which players make opening bets before looking at their hands. See this page.

BLIND STUD: See this page.

BLIND TIGER: A modern form of Blind Opening. See this page.

BLOCK RUMMY: A form of Rummy, this page, in which a player must make a final discard to go out; and play is blocked after all cards have been drawn from the pack, hand with lowest count becoming winner.

BLUCHER: Napoleon, with two extra bids. See Napoleon, this page.

BLUFF: The original and now obsolete form of Poker, using a twenty-card pack, ranking in descending order, A, K, Q, J, 10, with four players each being dealt a five-card hand. Bets, raises, and calls follow, each trying to outbluff the others, with the highest hand winning in the case of a showdown. The term “bluff” also applies to Straight Poker, this page.

BOATHOUSE RUMMY: Regular Rummy, this page, but with the rule that, if a player takes the top card of the discard pile, he must also take the card below it or the top card of the pack. Though he takes up two, he can discard only one. Play ends only when a player can lay down his entire hand, with an ace counting high or low; or both, as 2, A, K. Other players can match their own combinations but cannot lay off on other hands. The winner collects the value of each card left in an opposing hand, or simply one point for each card, whichever is agreed.

BOBTAIL OPENER: Poker. See this page.

BOBTAIL STUD: Poker. See this page.

BOLIVIA: This is an extension of Samba, this page, that has become a game in its own right. It is played with the triple pack (162 cards including jokers), and it follows the basic rules of samba, including the scoring of sequences of three to seven cards in the same suit, with a run of seven being termed an “escalera” (instead of a “samba”) and counting the customary 1500 points. However, a meld of three to seven “wild cards” is also allowed, as in certain forms of Canasta, and this is termed a “bolivia,” counting 2500. A “natural canasta” scores 500; a “mixed canasta,” 300, as in the parent games.

To go out, a team must meld at least one escalera (or sequence), plus either another escalera, a bolivia, or a canasta. The opening meld requirements are exactly as in samba, but with the greater scoring possibilities, game is 15,000 points.

Bolivia has been stepped up with the following rules applied to opening melds: At the 5000 level, 150 points; at 7000, still 150, but the player must lay down a mixed canasta or higher; at 8000, an opening meld of 200, with the player laying down a mixed canasta or better; at 9000, still 200, but the player must lay down a natural canasta or better. Game, however, is set at 10,000 (as in samba). In this version, a bolivia only counts 2000, but in going out it is allowable to add to the ends of an escalera. Thus played, this game is also termed Brazilian Canasta.

As a penalty rule, a team caught with a melded three- or four-card sequence has 1000 points taken from its score. Red threes double in value from 500 to 1000 when a team holds five of them; with 200 more points for the sixth. But unless a team manages to meld a canasta or better, its red threes are deducted from its score. Black threes can be rated on the same basis if so desired.

BOODLE: Technically, this is a transitional game between New Market and Michigan, but it is also applied to any form of Michigan in which additional “boodle cards” are added to the layout. See Michigan, this page.

BOSTON: A complex and now obsolete variation of Whist, this page, introduced at the time of the American Revolution and incorporating features of other games that were popular at the same period, including the turnup of a card from another pack to designate a preferred trump suit.

BOSTON DE FONTAINEBLEAU: A variant of Boston, with no turnup of a “preference card” from another pack. Instead, bidders can name their suits, with  ranking over

ranking over  ,

,  ,

,  in the order given, when bids are for the same number of tricks. See Whist, this page.

in the order given, when bids are for the same number of tricks. See Whist, this page.

BOUILLOTTE: A famous French antecedent of Poker, usually played by four players with a twenty-card pack ranking A, K, Q, 9, 8. Three cards are dealt to each player, and the next is turned up as a common card for all hands, termed the retourne. Hands are bet somewhat as in poker, the highest being a brelan carre, or four of a kind including the wild card; next a simple brelan, or three of a kind in hand; with a special bonus for a brelan favori, or three of a kind including the retourne. If no one holds a brelan, all dealt cards are shown along with the retourne and those of each suit valued as ace, 11; face cards, 10 each; others according to their spots. The active player holding the highest card in the winning suit is credited for point and wins the pool. With three players, queens are eliminated to leave only twelve cards; with five players, they are retained and sevens are added to make twenty-four cards.

BOURRE: A modern adaptation of Écarté, this page, with two to seven players using a full pack of fifty-two cards, ranking A, K, Q, J, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2. Each player contributes an equal number of chips to a pool or pot. Five cards are dealt to each player, and the next card is turned up to designate the trump suit. Any player may then turn down his hand and drop out; those who remain or “stay” can “stand pat” with their holdings, or discard one to five cards, drawing others to replace them.

The player at the dealer’s left leads to the first trick, and the rest must follow suit, each playing a higher card if he has one. If out of suit, a player must play any trump he holds. If unable to do either, he can discard from an odd suit. Highest card of suit led wins the trick unless trumped, and winner of each trick leads to the next.

However, there is one special rule: Any player holding any of the three top trumps (A, K, Q) must lead his highest trump at the first opportunity, thus drawing out or forcing out others, a unique feature of this game. Whoever wins the most tricks takes the pool; in case of a tie, it is split equally. But if any player stays and takes no tricks whatever, he must contribute the full amount of the pool (or pot) toward the next deal’s pool. That, perhaps, is the game’s great feature, encouraging players to “stay” when they really should “drop” but depend on the hope of cashing in the double pot on the next round.

BRAG: An English antecedent of Poker, this page, in which three cards are dealt to each player from a fifty-two-card pack. After betting, hands are compared to determine the winner. Three aces are the highest, followed by three kings and so on down, then pairs from aces down, with the odd card breaking a tie; then simply high card, with the same ranking, A, K, Q, J, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2. There are, however, three wild cards called “braggers,” each representing any card in the pack, including itself. They are the  A,

A,  J,

J,  9 and are ranked in that order. A “natural” combination takes precedence over one containing a “bragger”; hence three fives composed of

9 and are ranked in that order. A “natural” combination takes precedence over one containing a “bragger”; hence three fives composed of  5,

5,  5,

5,  5 would beat one formed by

5 would beat one formed by  5,

5,  A,

A,  9. Similarly, a pair such as

9. Similarly, a pair such as  10,

10,  10 would defeat

10 would defeat  10,

10,  A, which in turn would beat

A, which in turn would beat  10,

10,  J. In case of an absolute tie, the player nearest the dealer’s left is winner.

J. In case of an absolute tie, the player nearest the dealer’s left is winner.

In American Brag, there are eight braggers, consisting of the four jacks and the four nines. All are equal in value, and a combination containing a bragger outranks a natural hand of the same value, making three braggers the highest possible hand (over three aces) with tie hands fairly frequent.

BRAZILIAN CANASTA: A name given to Bolivia with stepped-up rules. See this page.

BRELAN: Another name for Bouillotte. See this page.

BRIDGE: See Auction Bridge, this page, and Contract Bridge, this page, now universal games.

BRIDGE WHIST: A once highly popular game representing the transition from Whist to Bridge. See this page and this page.

BUILD-UP: Double Dummy Bridge (see this page) with nine-card dummies. Players bid, two cards are dealt to each hand, then two moved from hand to dummy. This is repeated and play follows.

BUTCHER BOY: A form of Five-Card Stud Poker. See this page.

6

6 8, or 8

8, or 8 J

J 8. 4

8. 4 5

5 9, or 9

9, or 9 Q

Q 9. If the total comes to more than 9, the first figure is dropped; thus 9

9. If the total comes to more than 9, the first figure is dropped; thus 9 9

9 18 would be a natural 8.

18 would be a natural 8.

K Q

K Q  J

J  J

J  J

J