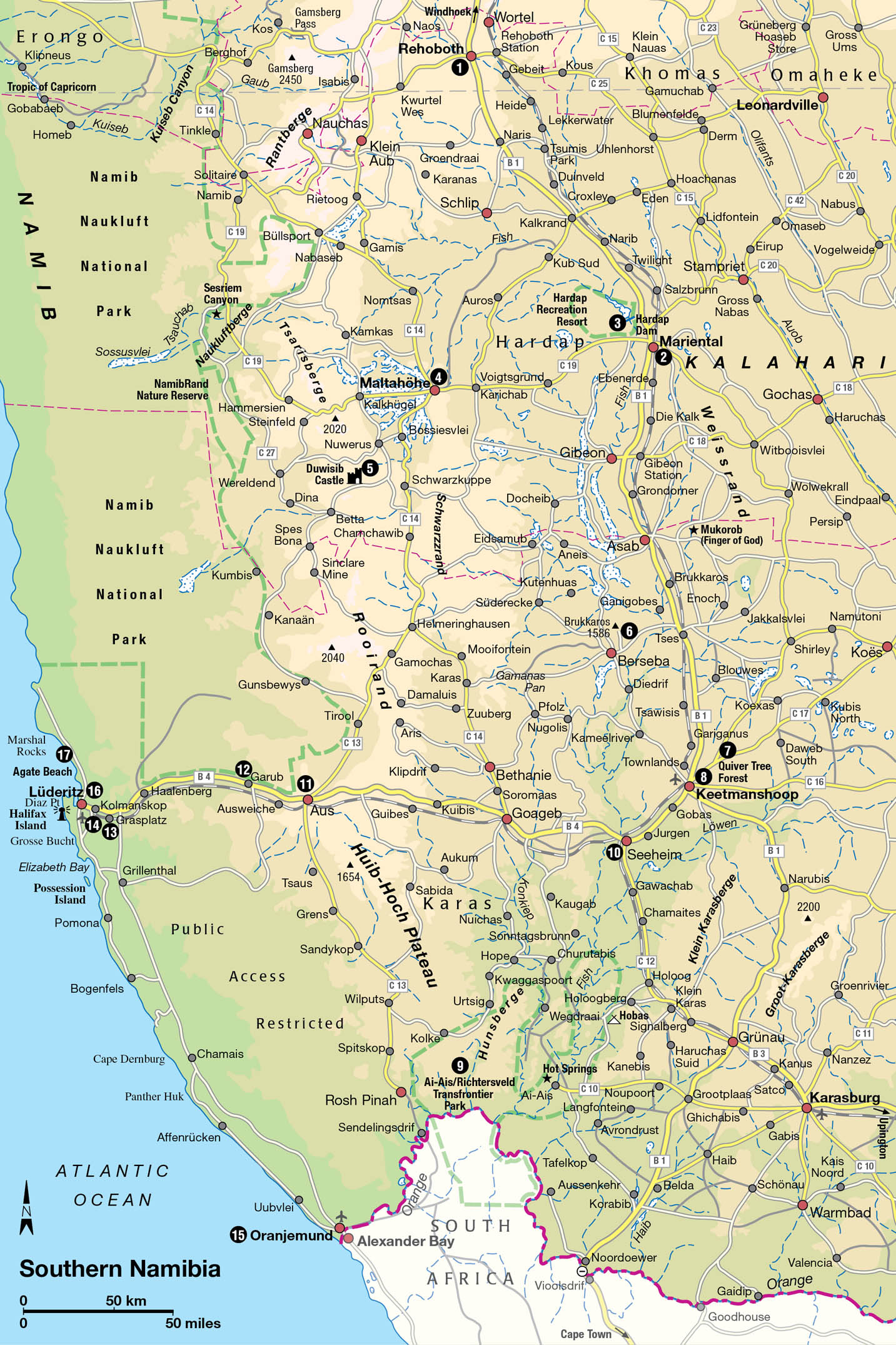

Stretched between the Namib Desert in the west and the dry Kalahari in the east, southern Namibia’s flat, wide-open expanses are characterised by stony outcrops peppered with quiver trees and low, table-top mountains. Often neglected as a tourist destination because it lacks northern Namibia’s wealth of big game, the region nevertheless contains a range of unusual sights, including one of the world’s least-visited geological wonders.

Kolmanskop, a deserted mining town near Lüderitz.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

Rehoboth and Lake Oanob

The quickest way to reach the south is to take the B1 from Windhoek. At first the road passes through bush interspersed with large trees, and you may even see baboons crossing the road between the capital and Rehoboth 1 [map], which straddles the Tropic of Capricorn 87km (52 miles) to the south. The main attraction in this area, 7km (4 miles) south of town, is Lake Oanob, which was created in 1990 when a 55-metre (180ft) dam – the highest in Namibia – was built on the eponymous river, and is now the site of the relaxed Lake Oanob Resort.

The wild horses near Garub.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

Bypassed by the main highway, Rehoboth nevertheless has an interesting history as the stronghold of the Baster community who farm the area. A mixed-race group – the progeny of Cape Dutch settlers and the indigenous Khoikhoi – the Basters found themselves rejected by both communities. Eventually, many of them banded together and migrated northwest away from South Africa, settling around the little mission station of Rehoboth in 1870. Throughout the last century, they made many attempts to obtain home rule for their community and did, in fact, finally obtain a measure of independence when Namibia was under South African control – although, ironically, this was granted in order to strengthen the divisions within the country in the name of apartheid.

The history of the Baster people is the subject of several displays in the Rehoboth Museum (tel: 062 522954; www.rehobothmuseum.com; 9am–noon Mon–Sat and 2–4pm Mon–Fri; charge), which is housed in the Old Postmasters House next to the Post Office, about 300 metres from the B1. In addition to detailing the foundation of Rehoboth and the short-lived reign of the autonomous Baster government in the 1980s, the museum also hosts some interesting displays on local geology and archaeology, as well as various traditional cultures of Namibia.

Hardap Game Park

Heading south from Rehoboth, after the B1 crosses the Oanob River, the taller trees disappear, and soon after that it leaves behind the Auas Mountains – the last obvious topographical feature until it reaches Mariental 2 [map], 174km (105 miles) further south. Just before Mariental, the road drops off the central highland plateau; a right turn along Route 93 here will take you to Hardap Dam 3 [map], the largest reservoir in Namibia with a surface area of some 25 sq km (10 sq miles). Fed by the Fish River, the lake is a haven for freshwater anglers, while the aquarium adjacent to the tourist office houses fish species from Namibia’s major rivers.

The restaurant at Hardap Dam Game Reserve and Resort.

Namibia Wildlife Resorts

An early morning or late afternoon game drive in the Hardap Dam Game Reserve & Resort (tel: 063-240381, www.nwr.com.na; resort gate: 6am–11pm; charge), which extends over 250 sq km (100 sq miles) on the southern and western side of the dam, can be rewarding. Along with Namibia’s southernmost population of black rhino, reintroduced at the end of the last century, wildlife includes, red hartebeest, kudu, eland, oryx, springbok and Hartmann’s mountain zebra. The dam is one of Namibia’s only two white pelican breeding sites, but it also attracts plenty of other birds, from red-knobbed coot and squacco heron to osprey, fish eagles and cormorants.

Mariental itself is a typically dry and dusty southern African everytown, equipped with a few small hotels, filling stations, supermarkets and restaurants. Superficially, it is an improbable setting for a flood, but that is exactly what happened here in March 2006, when the sluice gates to nearby Hardap Dam were opened too late after heavy rains, and the town was submerged waist-high in water.

To the northeast of Mariental, a clutch of newish game ranches set on the western fringe of the Kalahari makes for a convenient first stop out of Windhoek en route to the far south. The most established of these is the Intu Africa Kalahari Game Reserve, which offers accommodation in three small camps as well as guided game drives into an 180 sq km (70 sq miles) enclosure where grazers such as giraffe, dry-country antelope and Burchell’s zebra cohabit with suricate, bat-eared fox and black-backed jackal. Similar but smarter, the new Bagatelle Lodge has accommodation set on the crest of a dune and a similar range of wildlife to Intu Africa, supplemented by recently re-introduced cheetah.

Desert grasses beside the road to Lüderitz.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

Many travellers pass through Maltahöhe 4 [map], which lies 110km (65 miles) west of Mariental along the C19 at the junction of important routes north to Namib-Naukluft National Park and south to Lüderitz, but few linger very long in this nondescript town. Of greater interest, Duwisib Castle 5 [map] (tel: 066 385303; www.nwr.com.na; daily 8am–1pm and 2–5pm; charge) is an improbable neo-Baroque castle set in the heart of the desert some 72km southwest of Maltahöhe alongside the D286. Built in 1909 by Baron Captain Hans Heinrich von Wolf for his American wife, the 22-room castle was designed by the eminent architect Willi Sander, and constructed using local stone and other materials imported from Germany, and artisans from Italy, Sweden and Ireland. The Baron died in 1916 in the Battle of the Somme and his wife never returned to Namibia. Today, the castle houses a museum with an intriguing collection of 18th- and 19th-century antiques, armour and paintings, and there is a campsite in the grounds.

An unusual mountain and forest

Back on the B1, continuing southward from Mariental, you’ll see the imposing sandstone mass of the Weissrand escarpment dominating the scenery to the east. Formed by the incision of the Fish River between 5 and 15 million years ago, the escarpment has been cut back at an estimated rate of 4km (2.5 miles) every million years, and has actually retreated some 40km (25 miles) from the river during this time.

Still further south, to the right of the road beyond blink-and-you’ll-miss-it Asab, the steep outer slopes of the prominent Mount Brukkaros 6 [map], visible from 100km (60 miles) distant, lead to a 1,586-metre (5,203ft)-high rim that encloses a 2km (1.25-mile)-wide caldera. Despite appearances, Brukkaros is not a true volcano, but was created some 80 million years ago when the combination of magma trapped underground and seeping water created a hydrostatic explosion that caused surface rocks to be blasted high into the sky, but without any issue of lava or pumice.

The spectacular and little-visited caldera can be explored on foot, and it is also possible to stay overnight at the no-frills community-run Brukkaros Campsite (tel: 063 257188/223572). To get there from the B1, turn west onto the gravel D390 at Tses, then after 30km (18 miles), about 4km (2.5 miles) before you reach the former mission station of Berseba, follow the signpost right to Brukkaros, which you reach after 8km (5 miles). From the end of the road, it’s a 30-minute walk to the crater’s floor and then about an hour’s fairly steep climb up to the old observation station perched on the edge of the rim, offering superb views down to the plains below. Make sure you have sufficient water, a snack, stout walking shoes and a hat before setting off.

Back on the B1, turn left a few miles north of Keetmanshoop onto the C16 to Aroab, and then left again less than a mile further on to the C17 (signposted for Koës) to reach the Quiver Tree Forest 7 [map] (tel: 063 683421, www.quivertreeforest.com, daily; charge) some 12km (8 miles) to the east. The quiver – which grows up to 7 metres (23ft) high, and is also known as the kokerboom – is one of four Namibian aloes to be classified as a tree; around 250 such trees grow amongst the rocky outcrops here and the grove has been declared a national monument. Close by is Giants’ Playground, a series of huge rock totems strewn across the landscape like piles of oversized tin cans. Known locally as the Vratteveld, these outcrops are erosional remnants of molten lava dating back some 180 million years.

The Keetmanshoop Museum.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

The transport hub of Keetmanshoop 8 [map] is a good starting-point from which to explore Namibia’s southernmost reaches. Situated some 480km (298 miles) south of Windhoek, the town dates back to 1866 when a small settlement was established here by missionary Johann Schroeder and named in honour of the then president of the Rhenish Missionary Society, Johann Keetman. Of considerable architectural interest is the Old Post Office, which dates to 1910, but the oldest building is the imposing Rhenish Mission Church, a remarkable Gothic edifice erected in 1895 to replace an earlier structure destroyed by floods. Today, the church houses the Keetmanshoop Museum and is hung with memorabilia of the early days of the mission, while the gardens are dotted with wagons alongside a replica of a Nama hut (tel: 063 221256; Mon–Fri 7.30am–12.30pm and 2.30–4.30pm; free).

The town is also an important centre for Namibia’s Karakul sheep-breeding industry (for more information, click here).

The Fish River Canyon

Vying with Ethiopia’s Blue Nile Gorge for the (inherently subjective) accolade of Africa’s largest canyon is the magnificent Fish River Canyon, the dominant topographic feature of Namibia’s far south. Indeed, the canyon is one of Africa’s most spectacular natural wonders, measuring about 160km (100 miles) from north to south, up to 550 metres (1,800ft) deep, and up to 26km (15 miles) wide. Formerly the centrepiece of Fish River Canyon National Park, it is now protected in the Ai-Ais/Richtersveld Transfrontier Park 9 [map]. This is one of several so-called “Peace Parks” that cross Africa’s international boundaries, having recently merged management with its South African component, the former Richtersveld National Park, which lies immediately south of the Orange River.

The Fish River Canyon can easily be visited as a day trip from Keetmanshoop, though it’s worth staying overnight in the immediate vicinity to see it in the soft light of dusk or dawn. Either way, you need to follow the B4 southwest towards Lüderitz, then turn left at Seeheim ) [map] onto the gravel C12, and keep heading south. Then take a right turn onto the D601 south of Holoog, a left onto the D324 and a right onto the C10. If you’re travelling during the rainy season, be warned the road sometimes floods, so ask about current conditions at any hotel in Keetmanshoop.

The main entrance is the Hobas Information Centre (www.nwr.com.na; daily 7.30am–noon and 2–5pm; charge) at the northern end of the canyon, where a lovely campsite boasts modern toilet facilities, a shop and swimming pool. From Hobas you can drive to several observation points along the eastern rim, all of which offer awe-inspiring views over the rocks and riverbed far below. Access to the bottom of the canyon is not permitted to day visitors without a permit, obtainable either at Hobas or the Ai-Ais entrance gate. If you’re interested in hiking the entire canyon, bear in mind it’s quite a challenge and permitted only in winter; every day between May and September intrepid walkers who have made the necessary advance booking set off from the northernmost viewpoint to hike the 85km (53 miles) from Hobas to Ai-Ais, a four- or five-day trek. A permit is required to do the hike and best bought well in advance.

From Hobas, a gravel road winds through the mountains for about 70km (43 miles) to the /Ai-/Ais Hot Springs. For the final 10km (6 miles,) the road twists down through a wonderful ravine between piles of loose and shattered buff and dark brown rocks; the sudden greenness around the /Ai-/Ais spring at the bottom comes as a real surprise. Although rather strenuous, an ascent of the hills overlooking /Ai-/Ais is rewarded with spectacular views of the rest camp down below, and the inhospitable canyon stretching away to the west.

West of the Fish River, the Hunsberg Mountains form part of the Fish River Canyon conservation area but, because of its rugged terrain, the area is not open to the public – a pity, because as well as offering beautiful scenery, it is the habitat of several rare botanical species.

Tip

When you’re exploring the Lüderitz peninsula, stick to hard-surface roads and avoid loose sand and the area’s seemingly negotiable salt pans.

Into the forbidden territory

Back on the main road (the B4) between Seeheim and Lüderitz, you will cross the Fish River just as the northernmost signs of the canyon begin to show. Continuing further west, Diamond Area I (also known as the Sperrgebiet, or “forbidden territory”), is entered a few miles beyond Aus ! [map]. As the name suggests, this area is strictly controlled and it is illegal to leave the road until you get to Lüderitz. Stretching from the Orange River in the south to 26°S latitude, Diamond Area I extends about 100km (60 miles) inland from the Atlantic. Exclusive mining rights to this diamond-rich area have been granted to the Namibia Diamond Corporation (NAMDEB), which is owned in equal shares by the Namibian Government and the well-known mining multinational De Beers. As you approach Garub @ [map], along a stretch of road flanked by the Sperrgebiet to the south and Namib-Naukluft National Park to the north, keep an eye open for the wild horses of the Namib which are usually seen in this vicinity; a pumping-station is maintained to provide water for them. During the German colonial period a contingent of troops was stationed at Garub and it’s thought that the horses are the offspring of animals abandoned when the Germans retreated ahead of the advancing South African forces in 1915. Their numbers fluctuate from year to year, but during favourable conditions more than 100 horses roam the inhospitable desert.

The ghost town that is Kolmanskop, a former mining town.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

“It could be a Diamond…”

August Stauch was quite content with life. He had a fine position with the German railway company Lenz & Co, and his pretty wife, Ida, tended lovingly to him and their two children. If only it wasn’t for the asthma… When his firm won a contract from the German Colonial Railway Building and Operating Company to build a line far away in German South West Africa, he was an obvious choice for a posting. The colony’s dry, sunny climate would certainly be good for his asthma, and it was only a two-year contract. Accordingly, Stauch sadly took leave of his family and set out, landing at Windhoek in May 1907.

Stauch’s main task as railway inspector was to keep part of the new track being built between Lüderitz and Aus free of sand from the shifting dunes. One day, in April 1908, an unusual stone stuck to the oiled shovel of a worker, Zacharias Lewala, who ran to his foreman: “Must give Mister little klippe (stone). Is miskien diamant! (is maybe diamond!)” The foreman stashed the stone away in his pocket and later told Stauch the tale, laughing. But Stauch didn’t laugh; instead, he tried to cut the crystal in his pocket-watch with the stone – and succeeded. Lewala’s find turned out to be a tiny part of one of the world’s richest alluvial diamond fields, which today is still a mainstay of Namibia’s economy.

A once-stately house at Grasplatz £ [map] serves as a reminder of the hectic period following the discovery of diamonds here in 1908 (for more information, click here). A few miles further west, forlorn Kolmanskop $ [map] rises like a ghost town out of a sea of sand. Once the centre of the flourishing diamond-mining industry, today it’s a mere shadow of a more glorious era. Abandoned in 1956, nature has since reclaimed most of the town and sand has swept through broken windows and open doors, although towards the end of the 20th century some buildings such as the casino, the skittle alley and the retail shop were restored. The town can be visited only on guided tours, after a permit has been obtained from Lüderitz Safaris and Tours in Lüderitz (tel: 063 202719).

Today, the equivalent diamond-rush town is Oranjemund % [map] (Orange Mouth) about 8km (5 miles) from the mouth of the Orange River near the South African border. This became the focus of Namibia’s diamond industry following the discovery of diamonds here in 1928. The 100km (60-mile) stretch of coastline north of the town was once considered the world’s richest alluvial diamond field, but it’s now nearing the end of its lifespan and production is expected to wind down within the next 15 years. For obvious reasons, strict security measures are in force and this mining town, which appears from maps to be accessible only by air, is not open to tourists.

Lüderitz and around

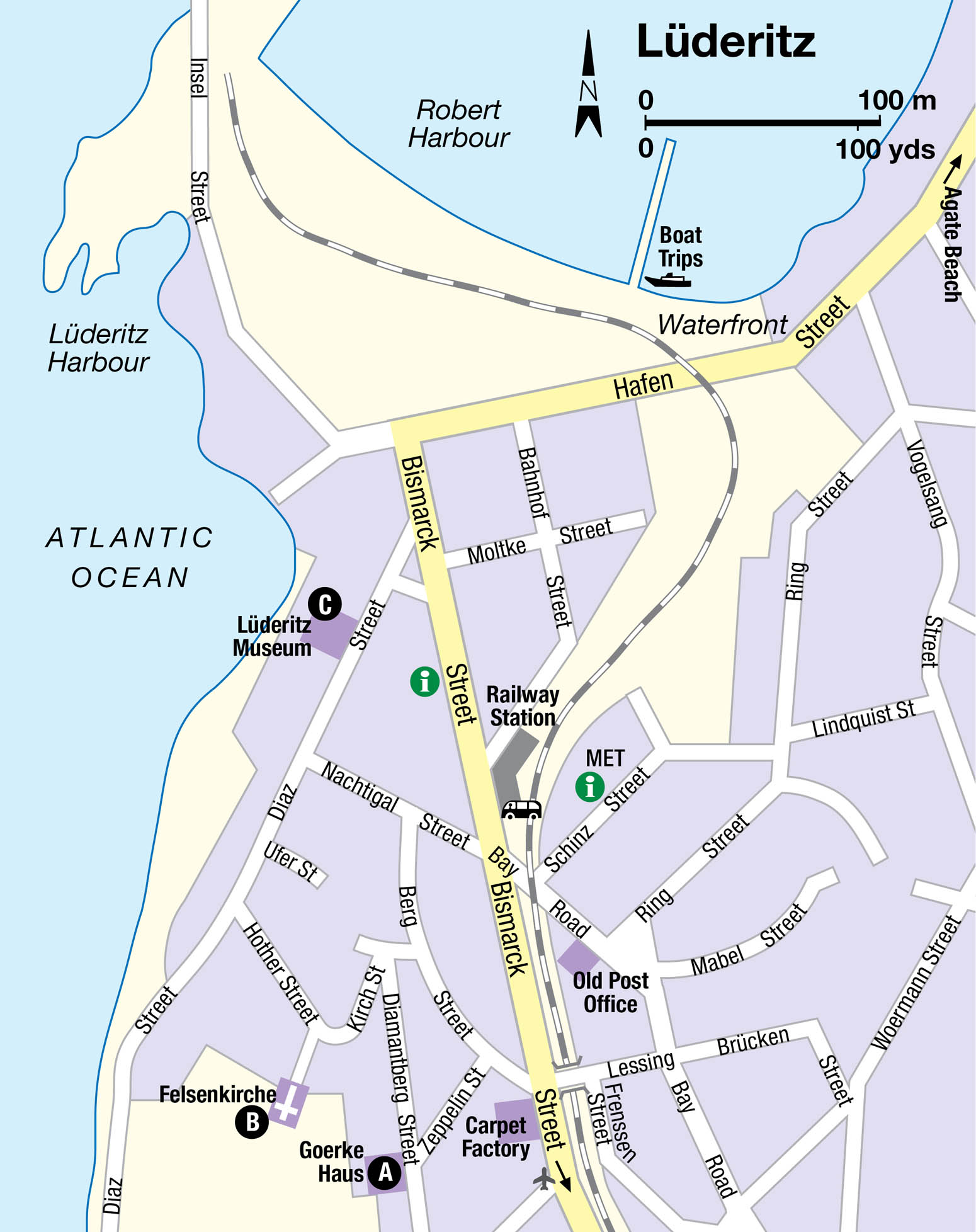

From Kolmanskop, it’s just 9km (5.5 miles) to the sleepy old fishing port of Lüderitz ^ [map], whose brightly painted Art Nouveau buildings stand in pleasing contrast to the granite outcrops and tall dunes that otherwise characterise this forbidding stretch of coast. The town is named after its founder Adolf Lüderitz, a former tobacco merchant and cattle rancher who bought the peninsula known to the Portuguese as Angra Pequena (Narrow Bay) from a local Nama chief and established a trading post there. Fishing and the harvesting of guano were the main activities in Lüderitz prior to 1909, when the diamond rush began.

German-style town-planning in Lüderitz.

Clare Louise Thomas/Apa Publications

Today, Lüderitz vies with Swakopmund as Namibia’s most engaging town. True, it has fewer facilities than Swakopmund, and attracts relatively low tourist volumes, but the compact layout and time-warped colonial architecture make it an utter delight to explore on foot. Don’t miss a visit to its most striking German colonial building, the pale blue Goerke Haus A [map] (Diamantberg Street; Mon–Fri 2–4pm and Sat–Sun 4–5pm; charge), perched on the slopes above the town centre. Designed by architect Otto Ertl, it was built in 1910 for the diamond company manager Lieutenant Hans Goerke, and while it is not typical of the local Art Nouveau architectural style, it is rich in the detail of this period.

The nearby Felsenkirche B [map] (Evangelical Lutheran Church), consecrated in 1912 and with an altar window donated by Kaiser Wilhelm II, is especially worth visiting during the late afternoon, when the setting sun illuminates the stained-glass windows beautifully. Also worth a visit, the Lüderitz Museum C [map] (Diaz Street; tel: 063-203959; Mon–Fri 10am–noon and 3.30–5pm; charge), has interesting displays about the history of the town and the local fishing and diamond industry, as well as the wildlife of the nearby desert and coast.

The Lüderitz Peninsula is characterised by numerous bays, lagoons and unspoilt stretches of beach which are accessible by car or, if one has the time and energy, on foot. At Diaz Point, 22km (14 miles) outside Lüderitz, a replica of the cross erected by Bartolomeu Diaz on 25 July 1488 serves as a reminder of the 15th-century Portuguese explorations. Fur seals can be seen on the rocks offshore here, while a varied marine birdlife includes the rare black oystercatcher, migrant waders such as turnstone and whimbrel, and various gulls and terns.

As an alternative (weather permitting), it’s worth taking a boat trip via Diaz Point to Halifax Island where you can get close-up views of the African penguin colony, though sadly this was badly affected by an April 2009 oil spill in which hundreds of birds died.

The beach & [map] at Agate Bay, 8km (5 miles) north of town, is popular with bathers, but the chances of finding any agates are slim. Another popular beach for swimming and picnicking is Grosse Bucht at the peninsula’s southern point, while at the nearby Sturmvogelbucht the remains of an old Norwegian whaling station can be seen rusting away.