The play’s the thing

Hamlet, Act 2, Scene 2

When Shakespeare arrived in London, probably in the late 1580s, it was the beginning of a new era in theatre, and performances were much closer to the art form we might recognise today than in the previous years. Dedicated playhouses were being built in the capital and the companies putting on performances were increasingly professional. New genres, venues and performance styles were being tested out on audiences hungry for entertainment.

Theatre-goers in Renaissance London were not shy in letting their opinions be known. Plays could draw enormous crowds but they were repeated only as long as audience numbers stayed high. A staggering number of plays only saw one production before disappearing for ever. It was an experimental time, but playwrights soon learned to give the audience what it wanted – fantastical stories, fight scenes and bloody deaths. It was a very different world to the one we know now, but this environment produced some of the greatest theatrical works ever written.

* * *

Shakespeare’s first theatrical home, the imaginatively named ‘Theatre’, was only the second purpose-built playhouse to be constructed. It was built in 1576 in Shoreditch, just outside London’s city walls and the reach of the City authorities. The venue only closed after an argument with the landlord over the lease. Fortunately for the Theatre’s owner, actor-manager James Burbage, the lease only applied to the land. When negotiations failed, Burbage had the building dismantled and moved south of the Thames to Southwark, where it was resurrected as the Globe in 1599.

South of the river, still out of the reach of the City authorities, was a place where Elizabethan Londoners went to have fun. Southwark was the area where theatres were generally located, among public gardens, bear-baiting arenas and taverns. It was also home to over 100 brothels, or ‘stews’ as they were known.1

There was a particularly close association between these houses of ill repute and their neighbours, the playhouses. The Rose Theatre had been built on the site of a former brothel, hence its name, the Elizabethan slang for a prostitute. The business partners Alleyn and Henslowe, who owned the Rose Theatre, also owned a number of stews in the area. Southwark, therefore, had something of a reputation and unsurprisingly bear-baiting and brothels, and their associated dangers from maulings and venereal disease respectively, are frequently alluded to in Renaissance plays. A civic edict ordered wherrymen (ferrymen) to moor their boats on the northern bank of the Thames at night, so that ‘thieves and other misdoers shall not be carried’ to the brothels and taverns of Southwark.

Ideas of what was considered entertaining were very different 400 years ago. For example, in the morning, the average Londoner might go to Tyburn, or to a number of other sites of execution in and around the capital, to watch a hanging. They could then walk across London Bridge, the only bridge crossing the Thames at the time, towards Southwark. At the south end of the bridge they would pass under the Great Stone Gate, where the decapitated heads of criminals and traitors were prominently displayed on pikes (one visitor to London in 1592 counted 34 heads on display). In the afternoon they could watch similar scenes acted out in theatres where characters would be dragged off to be executed and fake heads would be brought out onstage to show the deed had been done.

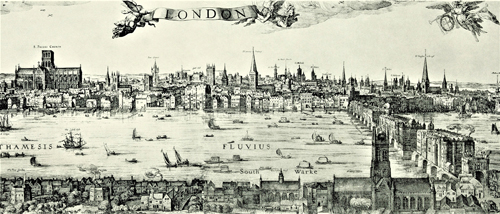

Panorama of London produced in 1616 by Claes Jansz Visscher showing the Globe and the Bear Garden in the bottom left and, in the bottom right, the heads of traitors above the Great Stone Gate on the south side of London Bridge.

* * *

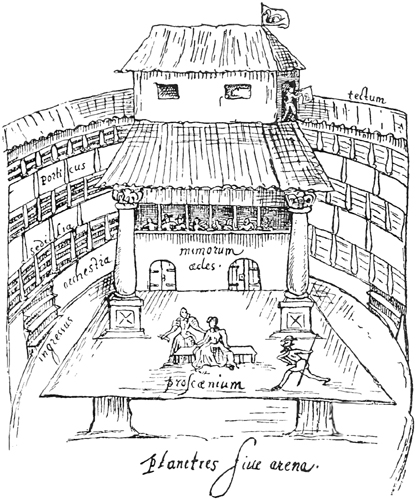

The popularity of theatres grew rapidly in the 1590s, when Shakespeare was just starting to make his presence felt on the theatrical scene. There were a handful of purpose-built playhouses in operation around the capital competing for audiences and more were constructed over the following decades. Knowledge of what these buildings looked like and how they operated has been pieced together from evidence from a variety of sources including archaeological excavation, contemporary letters and diaries as well as sketches and maps; there are even hints found in the plays themselves. In the opening of Henry V, Shakespeare describes the surroundings as ‘this wooden O’ and asks the audience to imagine the scene at the Battle of Agincourt instead of a bare stage in a London suburb. The actor speaking these words for the first time was standing in front of an audience either at the Curtain Theatre in Shoreditch or the Globe on the South Bank.

These early theatres were built from wood in a roughly circular or polygonal shape, which was as close to a circle as the materials and Elizabethan building techniques allowed. In the centre of the building was the pit or yard, open to the elements, where audience members (called groundlings) stood to watch performances in front of a raised stage. The stage was covered by a canopy richly decorated in bright colours and gilding, ‘this majestical roof fretted with golden fire’ (Hamlet).2 Encircling the yard were three storeys of covered galleries.

The interior of the Swan Theatre sketched by Johannes De Witt in 1595.

The theatres attracted their audiences from all parts of society, from the richest to the poorest. Within the walls of the theatre, nobility rubbed shoulders with ne’er-do-wells. Prostitutes and pickpockets plied their trade among the jostling crowds (though both professions might have found an easier living in the nearby taverns). Ticket prices were extremely cheap: for one penny anyone could stand in the yard under the open sky to watch the performance.3 Seats under cover in the galleried areas were more expensive and prices rose as comfort and proximity to the stage increased.

The amphitheatres were open year-round, apart from regular closures for 37 days during Lent, and eight weeks during the summer for touring. Performances, plague permitting, continued through autumn and winter. It was a determined and hardy audience member who could stand through several hours of a performance in the freezing cold or pouring rain.

England experienced a dramatic change in climate around the turn of the seventeenth century. Shakespeare seems to have made the most of the unpredictable weather and open-air conditions in his many references to storms (Pericles, Twelfth Night and, of course, The Tempest). His audience could well have been standing in a torrential downpour while hearing the lines from Julius Caesar, ‘Why, now, blow wind, swell billow and swim bark! / The storm is up, and all is on the hazard.’ When Hamlet complains, ‘The air bites shrewdly, it is very cold’, he wasn’t just setting the scene, it really was freezing. Europe and North America were in the middle of the ‘Little Ice Age’. The seventeenth century was the coldest of the entire second millennium and 1601, the year Hamlet was probably first performed, was its coldest year.

Nevertheless, people don’t seem to have been put off by the inclement weather. Theatres regularly attracted audiences in their thousands. Johannes de Witt, a Dutch scholar who visited London in 1595–1596, estimated that the Swan playhouse could hold 3,000 people. Nearby, Shakespeare’s Globe had a capacity of at least 3,000, according to the Spanish ambassador, who went to the rebuilt theatre in 1624; other estimates have it at a capacity of 3,300. It would have been crowded, to say the least. Perhaps the close proximity of 3,299 others helped to keep you warm.4

A trip to the theatre would have been an assault on all the senses. A combination of foul smells from the nearby polluted river, bear-baiting arenas and the neighbourhood breweries and tanneries (known collectively as the ‘stink trades’) would have pervaded the air. Inside the theatre food sellers weaved through the crowd offering nuts, meat and shellfish. Bad breath and body odour, from thousands of unwashed audience members huddled together with no toilet facilities, created ‘a foul and pestilent congregation of vapours’ as Shakespeare put it in Hamlet. Men could find a convenient pillar or wall; women didn’t even have to move and could take advantage of their long skirts to relieve themselves on the floor where they stood. This was nothing unusual.

Surprisingly, urine was a valuable commodity because of its high urea content (around 5 per cent in a fresh sample; the rest is mostly water). Over time chemical changes can convert the urea to ammonia and its high pH means it can break down organic material. Tanners would soak animal hides in stale urine to soften them. Ammonia, via nitrates, could also be used to produce saltpetre, a key ingredient in gunpowder, and a gunpowder manufacturer obtained the rights to scrape the floor in Ely cathedral where the women stood during services. No testing for urine was done on the site of the Rose Theatre when it was excavated in 1989, but if women were uninhibited in a place of worship, it seems unlikely they would have restrained themselves at the theatre. In Twelfth Night Duke Orsino may have been right when he said that the women in his audience ‘lack retention’. The lack of a roof at the Globe, and other theatres, may have made it bitterly cold in winter but at least it was well ventilated.

Then there was the noise. Productions in the amphitheatres had to be loud in order to be heard across the open space. Trumpets blared to herald battles and fireworks and pyrotechnics were used enthusiastically to illustrate cannon-fire and lightning storms, despite the obvious dangers of sparks in a densely packed and highly combustible venue. And the noise wasn’t just coming from the stage. Elizabethan and Jacobean audiences could be, indeed were expected to be, vocal during the performance.

* * *

Going to the theatre could be a considerable hazard; health and safety considerations were not paramount in Shakespeare’s day. On 29 June 1613, the Globe Theatre burned to the ground during a production of Henry VIII (known at the time as All is True). Incredibly, given the number of people likely to have been squashed into the building at the time, no one died.5 An account of the event from Sir Henry Wotton, an English author and diplomat, shows how lucky they were:

Now, let matters of state sleep, I will entertain you at the present with what has happened this week at the Bankside. The King’s players had a new play, called All is True, representing some principal pieces of the reign of Henry VIII, which was set forth with many an extraordinary circumstance of pomp and majesty, even to the matting of the stage; the Knights of the Order with their Georges and Garter, the Guards with their embroidered coats, and the like: sufficient within a while to make greatness very familiar, if not ridiculous. Now, King Henry making a masque at the Cardinal Wolsey’s house, and certain chambers being shot off at his entry, some of the paper or other stuff wherewith one of them was stopped did light on the thatch, where being thought at first but idle smoke, and their eyes more attentive to the show, it kindled inwardly and ran round like a train, consuming within less than an hour the whole house to the very grounds. This was the fatal period of that virtuous fabric, wherein yet nothing did perish but wood and straw and a few forsaken cloaks; only one man had his breeches set on fire, that would perhaps have broiled him if he had not by the benefit of a provident wit put it out with bottle ale.

Audience members were not always so lucky. On 13 January 1583 a huge crowd gathered to watch the bear-baiting at the Paris Garden in Southwark. Mounted up on rickety scaffolding, the building suddenly collapsed, wounding 200 to 300 spectators, some severely, and killing seven. This was nothing new or particularly surprising as there had been similar fatal collapses before this. What made this incident the more shocking was that it happened on a Sunday. The more conservative members of society saw it as a judgement from God and used it as an argument against all forms of entertainment that they saw as licentious.

It wasn’t just poor building work that threatened the welfare of Elizabethan audiences; the plays themselves sometimes posed risks. In 1587, the Lord Admiral’s Men were performing in London, probably at the Theatre playhouse. One of the actors was tied to a pillar and an inexplicably loaded musket was fired at him. It ‘missed the fellow he aimed at and killed a child, and a woman great with child forthwith, and hit another man in the head very sore’. The Lord Admiral’s Men went into a tactical temporary retirement and disappeared from the records for over a year.

* * *

It’s not difficult to see why City authorities and Puritans had such a low regard for theatres. When Shakespeare’s company tried to expand their operations to an indoor theatre north of the river, it was resisted for years. Finally, in 1608, they were granted permission to perform in an indoor playhouse at Blackfriars.6 It might have been seen as a step up in the theatrical world, as its location, north of the river, was more respectable; the audience, all seated, was considerably smaller, and ticket prices were much higher. But the company didn’t turn its back on the Globe. Instead, they based themselves at their indoor venue for the cold winter months but returned to their South Bank home during the summer.

The Blackfriars venue was considerably smaller than the Globe and productions had to be adapted to the new space. Trumpet calls could be deafening in the enclosed room and were abandoned for quieter instruments. Extensive use of pyrotechnics inside could choke an audience and make the stage difficult to see through the smoke. Light entered, and presumably smells and smoke escaped, through small windows located near the high ceiling and extra lighting was provided by candles.

Performances had to be adapted for the more claustrophobic environment, but some plays were better suited than others. Macbeth, a play set mostly at night that includes witches, ghosts and murders, would have been quite a different experience in the gloomy setting of Blackfriars compared to the bright open space of the Globe. The smaller enclosed space allowed for more intimate scenes and elaborate special effects to be incorporated into plays, but battle scenes had to be scaled down to fit on the smaller stage. In those days actors fought with real swords and audience members could even sit onstage to watch the action up close. In 1622, at the indoor Red Bull Theatre, one audience member got too close. A felt-maker’s apprentice was accidentally injured by one of the actors, Richard Baxter, during a particularly exuberant sword display. The very real risk of injury must have made for an exhilarating experience for some.

Audiences at Blackfriars might have been expected to be more genteel, but things could still get pretty raucous. On one occasion an Irish lord blocked the view of the Countess of Essex at the Blackfriars Theatre. An argument ensued between the lord and the Countess’s escort that quickly developed into a duel. Later in the seventeenth century, during a performance of Macbeth at the Blackfriars venue, a nobleman perched on the edge of the stage spotted someone he knew entering the theatre on the other side. He stood up and walked through the action onstage to greet his friend. When one of the actors rebuked the nobleman he was slapped for his impudence and the audience rioted.

* * *

Going to the theatre was obviously rather different in Shakespeare’s day, more crowded, noisier, undoubtedly smellier, and a rather more risky experience than now. None of this seems to have deterred Elizabethan audiences. Even though there were only a handful of venues, it is estimated that in 1595 around 15,000 people went to the theatre every week. The appetite for something new to watch was difficult to sate.

To keep the crowds interested, the turnover of plays was considerable and productions were only repeated if they were popular. For example, in the 1594/5 season the Lord Admiral’s Men enjoyed a run of 49 weeks in the Rose Theatre, interrupted only by Lent and a short break for essential repairs. In that time they put on 273 performances of 38 different plays, 21 of which were completely new. Only eight of those plays were performed the following season. Playwrights were churning out new material at an incredible rate and rehearsal time was severely limited. An Elizabethan actor’s capacity for learning new lines, and retaining them to build up a considerable repertoire, must have been phenomenal.

Modern audiences can easily miss connections between plays because they are usually seen in isolation. Frequent visits to the theatre and a rapid turnover of material meant an Elizabethan audience was much better placed to pick up on links between plays as well as subtle references to work by other playwrights. Writers like Shakespeare could also afford to spread the narrative over several plays, such as in the three parts of Henry VI, because they would be presented in relatively quick succession.

But there were other constraints on playwrights that just don’t exist today. Performances started at 2 p.m. and were restricted to a mere ‘two hours’ traffic of our stage’ (Romeo and Juliet), by order of the civic authorities, although this doesn’t appear to have been strictly enforced. Even so, plays had to be over before dark in the open-air theatres (fine in the summer, but it could mean a 4 p.m. finish in an English winter, at the latest). Most performances appear to have lasted between two and three hours, including a jig at the end.

A playwright may have submitted a beautifully crafted, elegantly worded script full of poetical speeches and witty dialogue, but changes would be inevitable in performance. Manuscripts would be annotated with stage directions and edits made to keep everything within the restricted time. Stage performances would have focused on the action and kept the minimum of explanation to make the plot comprehensible. Henry V, for example, was probably staged without many of the stirring speeches that are favourites with modern audiences.

The different versions of Shakespeare’s plays that have come down to us offer possible insights into how plays were edited for performance, and how they were amended over the years to bring new life to old plays in revival. For example, the quarto version7 of Henry V was printed shortly after the play first appeared on the stage and the text was probably taken from the transcript of a performance. It is much shorter than the Folio version,8 which most likely came from the original manuscript, and captures all of Shakespeare’s poetic vision for the play. The full text is a more enjoyable read for us today than the truncated version put onstage.

Tastes in drama were also different. For example, Pericles, rarely performed today, was a huge hit with Shakespeare’s audiences. The popularity of Titus Andronicus, another play that eventually fell out of favour for centuries owing to its violent nature, was still drawing envious remarks from Ben Jonson 20 years after it was first performed. By contrast, Anthony and Cleopatra was not nearly so popular, and would have been lost for ever if it had not been included in the First Folio. But by and large, Renaissance audiences went to see the same Shakespeare plays that still pull in the crowds over 400 years later. This raises the question, how different were the performances themselves?

One difference was the style of acting, which would probably have been very formal and stilted to modern eyes. In Elizabethan times, actors had been expected, by and large, to stand still and address their lines to the audience using specific hand gestures to express emotion and sentiment. But performers were increasingly using a more lifelike style that often brought praise from critics. Shakespeare’s company was certainly moving towards a more naturalistic mode of bringing their characters to life onstage. The playwright even made fun of how some actors still used a very formal style, as in Hamlet when the young prince talks to the troupe of actors just arrived at Elsinore Castle:

Speak the speech, I pray you, as I pronounced it to you, trippingly on the tongue; but if you mouth it, as many of your players do, I had as lief the town-crier spoke my lines. Nor do not saw the air too much with your hand, thus, but use all gently; for in the very torrent, tempest, and, as I may say, the whirlwind of passion, you must acquire and beget a temperance that may give it smoothness.

Set design was also very different. No curtain could be brought down to hide complex set changes, and so simple things like a throne would signify the setting was a royal palace. Signs might be placed over doors to show whose home or which tavern they signified, and black hangings might be used to identify the play as a tragedy. Lighting couldn’t be controlled in the open-air theatres and so actors holding torches or lanterns showed it was night-time. A prologue or chorus was often used to set the scene and describe sudden changes in setting. Mostly the stage was fairly bare, ‘a sterile promontory’ as Hamlet put it, but this certainly wouldn’t have detracted from the experience. Elizabethan audiences went to hear plays rather than see them, and just because there wasn’t much in the way of set design didn’t mean there was nothing of interest to see on the stage.

Money might have been saved on the sets but considerable investments were made on clothing and costumes. Those in the higher echelons of society, mainly knights and nobles, had a custom of bequeathing their clothes to their servants. These servants couldn’t have worn the clothes left to them as there was a strict etiquette about who could wear what in Elizabethan England, so the servants would sell the clothes on to acting companies. This meant actors could be clothed in exquisite garments bought at a knock-down price. Even elaborate clerical garments could be easily obtained thanks to the Reformation.

Costuming choices seem to have been made based on appearance rather than accuracy. A sketch of a production of Titus Andronicus from 1595 shows half the cast in Roman garb and the rest in contemporary Elizabethan clothes. This was probably not due to a restricted wardrobe budget but rather a deliberate choice.

Sketch apparently of a performance of Titus Andronicus made by Henry Peacham in 1595. It shows Tamora pleading with Titus. Behind her are her two sons with their hands tied and behind them stands Aaron.

Elizabethan theatre was not about realism, faithful reproductions of historical events or moral lessons – it was about entertainment. Historical accuracy was only a minor consideration and chronology suffered particularly under Shakespeare’s quill. He could skip over several years in a few lines and travel backwards in time from one scene to the next. The Bard was perfectly happy to change events, omit certain characters or introduce new fictional ones into his history plays when it suited him.

There are many other things within Shakespeare’s plays that today seem anachronistic. Clocks strike when they shouldn’t. Cleopatra plays billiards centuries before the game, or anything like it, was invented. Macbeth talks of payments made in dollars before such a currency existed. In short, considerable artistic licence was in use.

A playwright’s first consideration was the drama and spectacle of a play, but practical issues of staging were a vital consideration. After performing at public theatres, acting companies might have to travel to a much smaller venue for a private performance paid for by a rich patron. Props, costumes and staging would be kept to the very minimum for easy transport. The staging of the play would have been altered on the fly depending on what space was available to them. For example, without a trapdoor available, the gravedigger’s scene in Hamlet is likely to have been cut.

On large stages like the Globe, plays could be written specifically for the facilities available. But even when the space was large and prop stores were close to hand, Shakespeare kept things to a minimum. Small props, such as letters and rings, might have been essential to the plot but it is estimated that 80 per cent of the scenes he wrote for the Globe require no props whatsoever. However, he did make exceptions for some of the gorier scenes when body parts and blood were used in abundance to appeal to the Elizabethan and Jacobean audiences’ tastes.

* * *

Shakespeare referred to the stage as ‘this unworthy scaffold’ (Henry V) – not only a show of modesty but also a comparison with sites of execution. Shakespeare and his fellow playwrights were trying to attract the same audiences that went to watch bear-baiting and fencing displays for the same price as a theatre ticket, and also had to remember that the public could witness floggings, dismemberments and executions of criminals for free. In terms of spectacle, theatrical performances had to give value for money. Shakespeare scattered violence, blood and gore liberally throughout his plays. His characters fight each other with swords, some are stabbed or decapitated, hands are sliced off, tongues are cut out and eyes are gouged.

Perhaps the most iconic image people associate with Shakespeare is also its most macabre: Hamlet holding a human skull. It might have been relatively easy to bribe someone to steal a skull from a local charnel house but, despite Elizabethan familiarity with death and decapitated heads on spikes, using genuine human remains in a play might have been seen as disrespectful. Nevertheless, several productions of Hamlet have used real skulls. In 1982 the pianist André Tchaikowsky died and bequeathed his skull to the Royal Shakespeare Company for use in Hamlet’s graveyard scene. Though it was often used in rehearsals, actors were unnerved by the skull and it wasn’t used in a live performance until 2008.

To modern audiences Shakespeare may seem quite macabre in his tastes, but he was certainly not exceptional among his contemporaries. Compared to John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi, or The Battle of Alcazar by George Peele (a play with a ‘bloody banquet’ that features ‘dead men’s heads in dishes’ and that later calls for three characters to be disembowelled onstage), Shakespeare was usually quite restrained in his depiction of bloody and violent acts.

Blood and gore on the Renaissance stage was the norm, and directions for characters to be wounded, hurt or stabbed feature in more than 150 contemporary plays. As witnesses to violence and death on an almost daily basis, Elizabethan theatre audiences would not have been easily shocked. They were also in a good position to be able to judge the accuracy of many of the gorier stage props used, including the severed hands and tongues in Titus Andronicus and the decapitated heads brought onstage in several of the history plays – Henry VI Part ii calls for three in the same play! The real thing was visible on spikes not far from the theatre.

Stage make-up and props were available, but how realistic these might have been is not so easy to judge. Neither is the effect a playwright was trying to create. A suggestion of how artificial body parts might be made for the stage comes from Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi. Severed hands are presented to the Duchess but it is a trick. As Ferdinand explains,

Excellent, as I would wish; she’s plagued in art.

These presentations are but framed in wax

By the curious master in that quality,

Vincentio Lauriola, and she takes them

For true substantial bodies.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries wax effigies were sometimes produced of recently deceased nobility. A particularly famous one of Prince Henry, who had died on 6 November 1612, was drawn through the streets of London – the same year that The Duchess of Malfi was first performed at the Blackfriars Theatre. Particular attention was paid to the face and hands to make them resemble the Prince as closely as possible. Funeral effigies were elaborate constructions as well as realistic – Prince Henry’s wax figure could sit and stand. It was common practice to name the artist who had made these impressive figures and so Webster was following tradition when he names Vincentio Lauriola, even though no such person is known to have existed. In The Winter’s Tale Shakespeare has a statue of Hermione brought onstage as a memorial to the character that died earlier in the play. The audience is told the uncannily lifelike effigy has been newly produced by the Italian master Julio Romano, who was a real-life Italian Renaissance artist.

As well as direct references to body parts in play texts and stage directions, a list of props and costumes belonging to the Lord Admiral’s Men has survived. Their collection of theatrical possessions included ‘Mahemetes head’, ‘Arogosse head’, ‘iii Turkes heads’ as well as numerous limbs and a wooden leg.

Perhaps even more gruesome than decapitated heads, individual eyes are occasionally required to show to the audience. Today lychees are often employed when actors need to be seen to have an eyeball gouged out onstage, as the size, colour and texture of the fruit make excellent eye substitutes. Although the fruit is referred to in its native China as far back as 2000 bc, the first mention of it in the West is in 1646, long after Shakespeare was dead and buried. Elizabethans probably didn’t need to go to such lengths to produce fake eyeballs when the real thing was readily available from nearby slaughterhouses.

Another difficulty was blood. There are many references to blood in plays of this era and several blood substitutes are known to have been used to create a good effect. Red vinegar and wine could be stored in bladders or soaked into sponges and concealed about an actor’s person. Then at the critical moment he would squeeze the sponge or pierce the bladder to make the ‘blood’ flow. One problem with the use of vinegar or wine is that, though they would look fairly convincing in a puddle onstage, they don’t adhere well to the skin. Something stickier, and with a more intense colour, was needed for daubing on actors or props.

Several references have been found to the use of vermilion, a mercury compound of sulfur that makes a bright red pigment. One such reference is in the payments made by Canterbury officials in 1528–9, apparently for a play on the subject of St Thomas Becket. The pigment was presumably used to illustrate blood at the moment of the saint’s martyrdom.9 Vermilion is a very distinctive red but it is not a particularly good match for blood. Its striking colour would enable an audience to easily understand that it represented blood in certain situations, but sometimes it just wasn’t good enough and a play called for the use of the real thing.

Animal blood from pigs, cattle or sheep would have been relatively easy to obtain from nearby abattoirs or butchers, but not all blood behaves in exactly the same way. Clots are formed when blood is exposed to the air, a blood vessel is damaged or blood flow ceases and the blood begins to pool. These clots are made of platelets (fragments of red blood cells) and a mesh of long fibres called fibrin. The fibres clump together to form a net that traps more platelets and other cells in the blood. Clots are vital to prevent blood loss and to stop bacteria and other sources of infection from entering a wound, but this also means that liquid blood, left exposed to the air, doesn’t stay liquid for long, at least in small quantities (seconds to minutes). Large volumes of blood can take a long time to fully clot, hours even. Compared with human blood, large quantities of cow’s blood clot more slowly and remain liquid for longer before turning into a sticky jellied mess that won’t flow. Sheep’s blood takes even longer.

Using sheep’s blood meant there was plenty of time to collect it from a nearby abattoir and store it in bladders until it was needed onstage. When the moment arrived to pierce the bladder and let the blood flow, it was most likely to remain liquid. This fact was well known to the Elizabethan actors and entertainers, even if they knew nothing of the science of clotting.

Reginald Scot, in his 1584 book The Discoverie of Witchcraft, describes a trick that could be performed to allow someone to appear to stab themselves. The trick called for the use of ‘a gut or bladder of blood’ placed between a ‘plate’ and a ‘false belly’, ‘which blood must be of calf or of a sheep; but in no wise of an ox or cow, for that will be too thick’. Although Scot refers to the thickness of the blood, a sheep’s blood is actually no ‘thinner’ than a cow’s; the red blood cell mass (in healthy animals) is the same. Scot probably meant how quickly it stopped flowing, or clotted, and just didn’t have the technical word for it.

Bladders of sheep’s blood would therefore have been a fairly standard prop in an Elizabethan theatre. But sometimes even real blood wasn’t gory enough and stage directions became even more graphic. One play contains a note simply calling for ‘raw flesh’. Annotations in the margins of Peele’s The Battle of Alcazar detail how three characters could appear to be disembowelled in front of the audience. The notes call for ‘3 vials of blood & a sheeps gather’. The gather was a bladder holding the liver, heart and lungs of the sheep. A small flask of its blood was given to each actor to burst open at the appropriate moment.

Regardless of what substance was used, all of these blood types and blood substitutes would stain if they came into contact with the costumes. Clothing was the most valuable part of an acting company’s possessions, but laundering the delicate material used for the ornate costumes of the tragedies would have been difficult, especially given the limited cleaning materials available at the time. One option was soap, which is excellent for removing greasy deposits but, depending on the composition of the soap, probably wasn’t good for removing blood stains.

Another option was lye, which can be made from the ashes of hardwood. During their life these trees accumulate potassium, which doesn’t burn and so is left concentrated in the ashes. When mixed with water the potassium forms potassium hydroxide, or caustic potash, a corrosive liquid that destroys organic material such as blood. However, if the mixture is too strong it can also corrode the fabric and harm the hands of the person doing the laundry.10

A slightly less caustic, but possibly more unpleasant, approach would be to wash the clothes in stale urine. The ammonia formed from the urea would also break down organic matter that causes blood stains but it is much less corrosive than lye, so the fabric of the clothes was less likely to be damaged. However, the dyes used to colour Elizabethan fabrics would not have been very colour-fast and repeated washing would fade the costumes, so it was to be avoided if at all possible. Blood onstage was therefore carefully controlled.

The 1649 play The Rebellion of Naples, by an author known only as T. B., calls for an on-stage decapitation and even suggests how it might be done. ‘He thrusts out his head, and they cut off a false head made of a bladder fill’d with blood.’ Surely blood spurting uncontrollably all over the stage would have theatre producers wincing at the potential laundry bill. But in 1649 the theatres were closed, and had been for seven years thanks to the Puritans, so the play was probably written as a closet play (to be read rather than performed) and these notes were merely suggestions rather than practical details on how it should be staged.

In plays that were performed onstage, deaths that were more difficult to act out might take place offstage. Characters returning from a violent episode that took place offstage could appear in front of the crowd with themselves and/or their props already bloodied. But if a character was to be wounded or killed onstage, the directions were often quite specific. For example, in the King’s Men’s production of The Princess performed around 1637: ‘Bragadine shoots, Virgil puts his hand to his eye, with a bloody sponge and the blood runs down.’

In the case of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, the script calls for Caesar to be killed onstage by eight conspirators.11 There are references to blood, and the 33 stab wounds specified in the text are likely to make one hell of a mess, but all this can be carefully orchestrated.

At the moment of the attack, Caesar is surrounded by the conspirators; it looks dramatic and also shields the audience from what is actually going on. It would be enough for the audience to see swords drawn and Caesar collapse to the floor to understand that he had been stabbed many times. A pool of blood can then be made on the stage and a pre-bloodied mantle can be laid over him. Everything can be carefully controlled to avoid ruining not just Caesar’s costume but those of his murderers too.

After the deed is done Brutus calls on his fellow conspirators to ‘Stoop, Romans, stoop, / And let us bathe our hands in Caesar’s blood / Up to the elbows and besmear our swords’. Carefully applying the blood from a pool on the floor means staining the costumes is less likely. It is also important in terms of plot, as when Mark Antony enters and shakes hands with each of the conspirators the blood is spread to his hands, and he marks himself out as someone who is also guilty of crimes against Caesar (he profits enormously from Caesar’s death by becoming a ruler of Rome). The point of the scene may not be to realistically depict the death of Caesar, but to illustrate the event and dramatically draw attention to the guilt of those involved, who are left quite literally with blood on their hands.

Getting the blood onto the actors was one issue, but washing it off before the next scene presented another challenge. An example of how this was managed onstage comes from the play Look About You, performed by the Lord Admiral’s Men in 1599. In the play the trickster Skinke goes through a series of transformations to evade capture. In one scene, he enters the stage disguised as Prince John, wearing the Prince’s cloak and sword. This disguise is rapidly discarded, then Skinke changes clothes with a servant and applies blood to his face from a convenient saucer. He has only a few lines to achieve all of this before the ‘real’ Prince John enters. The Prince takes Skinke for a beaten and abused servant and lets him go. Before he leaves he tells the audience he will swim the Thames to Blackheath, hinting that he is going to wash off the blood; 250 lines later Skinke reappears without the blood and disguised as a hermit. Blood was clearly easier to apply than to remove, and the actor is given a considerable amount of time to clean up and don a new disguise.

In Julius Caesar Shakespeare allows much less time for the actors to clean up. Brutus has a 43-line opportunity to wash the blood from his hands and arms while Antony mourns over Caesar’s body and discusses plans with his servant. Antony then has 34 lines to do the same while Brutus addresses the crowd in Caesar’s funeral oration. The pace of the play isn’t held up but there is still just enough time for the actors to wash off the blood – an example of Shakespeare’s mastery of stagecraft.

Whatever the expectations and limitations of special effects in Elizabethan theatre, they didn’t deter the Bard from including an extraordinary variety of different deaths for his characters.

Notes

1 There are two possible explanations for brothels being referred to as stews. It may be because of their location near ponds used to breed fish for the dinner table; it may also be a connection to Roman bath-houses, often associated with prostitution, which contained a sweating room and therefore a stove, which in Norman French is called ‘estues’ or ‘estuwes’.

2 This canopy, supported by two enormous pillars, was referred to as ‘the heavens’ and the area below stage, accessed by a trapdoor in the middle of the stage, was consequently known as ‘hell’.

3 For comparison, one penny could buy a loaf of bread. Actors, and artisans who had completed their apprenticeship, earned around a shilling a day (12 pence).

4 In the new Globe Theatre, opened in 1997 close to the original site of Shakespeare’s 1599 theatre, capacity was more than halved to 1,500 owing to health and safety considerations.

5 Perhaps wary of its fiery history, it was not until 13 years after its opening that the new Globe Theatre was brave enough to stage a production of this play.

6 From a historical point of view the Blackfriars Theatre is the more important venue as it formed the basis for all subsequent indoor theatres.

7 Around half of Shakespeare’s plays were published individually during his lifetime as quarto editions, so called because the paper was folded twice to make four leaves.

8 After his death, John Heminges and Henry Condell, actors in Shakespeare’s company, collected together all of his works from the author’s own copies or the company’s manuscripts, and compiled them into one volume, known as the First Folio.

9 Vermilion (also known as cinnabar) was a versatile pigment that could be used as paint, ink and even blusher.

10 Lye can be so corrosive that it has been used to dissolve the bodies of murder victims.

11 According to Plutarch’s Lives, Shakespeare’s source for the play, the conspirators pressed together so eagerly to stab Julius Caesar that they wounded each other.