Religious Freedom as Concept and Constitutional Right

No one shall be disquieted on account of his opinions, including his religious views, provided their manifestation does not disturb the public order established by law.

(Nul ne doit être inquiété pour ses opinions, même religieuses, pourvu que leur manifestation ne trouble pas l’ordre public établi par la loi.)

—Article 10, Declaration of the Rights of Man

Article 10 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man can be read today as a straightforward affirmation of the freedom of thought, and in particular of the freedom of religion. But the debates that led to Article 10 were anything but serene. Just over a month after the storming of the Bastille had ensured the survival of the National Assembly, representatives were struggling to draft a document laying out the basic human rights that would undergird the constitution they would write. Of all the heated debates that accompanied this process, those that occurred on August 22 and 23 dealing with religious liberty were the most contentious. The editor of the Gazette Nationale/Moniteur Universel wrote in despair that it was impossible to describe accurately the session of August 23 at which “the most remarkable disorder dominated, where partiality was in control. . . . The motion of M. de Castellane was amended, sub-amended, divided, tortured, twisted in a hundred ways. One heard on all sides: I propose an amendment. . . . I demand to speak.”1

At one level the passion that had representatives shouting at each other in the Assembly is easy to grasp. These men were staking out positions on the appropriate role of religion in the reformed French state, a tendentious issue that bedeviled French regimes throughout the revolutionary era and beyond. The Count de Castellane’s motion, which became the basis for the final version of the article, established a position that maximized individual freedom, asserting that “no one ought to be disturbed for his religious opinions, nor troubled in the exercise of his religion.”2 From Castellane’s perspective, shared by the Count de Mirabeau, the leading voice for reform in the Assembly, Catholics and non-Catholics had equal rights to believe and practice the religion of their choice, and the state had no role to play in policing how this religious freedom was exercised.

Castellane’s motion provoked controversy because it replaced drafts of three articles that looked back to the Old Regime in declaring that a state-endorsed religion was essential for the public order. Article 18 of this earlier proposal included an explicit reference to an established religion as a legitimate constraint on individual religious liberty: “No citizen who does not trouble the established cult should be disturbed.”3 Castellane’s attempt to discard language supporting a public cult and a regulatory role for the state provoked heated responses from defenders of Catholic interests in the Assembly, most notably the abbé d’Eymar. As the debate drew to an end, Eymar proposed to substitute for Castellane’s motion Article 16 of the earlier proposal: “Law, being unable to control secret crimes, needs the support of religion. It is thereby essential and indispensable for the good order of society, that religion be maintained, conserved, and respected.”4 Mirabeau and the Protestant pastor Jean-Paul Rabaut de Saint-Etienne fought back hard against this assertion of the state’s interest in maintaining religion, pushing the Assembly to reject Eymar’s motion and vote on Castellane’s instead. But it was at this point that the chaos described by the Moniteur broke out, and at the last minute the motion was amended to add the clause that preserved a tutelary role for the state. In the final wording Article 10, following Castellane, affirmed that no person would be troubled for his religious opinions, but only if “their manifestation does not trouble the public order established by law.”5 Although it substituted “public order” for “established cult” as the basis for warranting limits on religious liberty, this last-minute amendment amounted to a concession to those Catholics who wished the state to retain the right to monitor and control the public expression of religion. It also opened the door for all future regimes to intervene in religious matters based on shifting interpretations of what constituted a threat to “public order.”

Looking back on the debates over Article 10 it is easy to see the relationship between church and state, Catholicism and the emerging regime, as the central point of contention. But in stating their positions on this question the representatives in the National Assembly also reformulated the terms used for understanding religious liberty, and their relationship to each other. This shift was dramatically emphasized in the speeches of François Jean-Joseph de Laborde and Mirabeau on August 22. Laborde began by calling on the delegates to embrace the idea of tolerance, and to remember all the blood shed by intolerance over the past two centuries. He referred as well to the “freedom of conscience” and the “freedom of religion,” but he used these phrases, along with “tolerance,” indiscriminately. No one could doubt that Laborde favored Castellane’s proposal, but his language suggests a fuzzy conceptualization of the basic terms used to define and defend religious liberty.

Mirabeau’s speech, which followed Laborde’s, suffers from no such confusion. Mirabeau publicly rebuked his colleague, not because they disagreed on the need to defend religious liberty but because of the terms he employed to defend this right. Mirabeau proclaimed that “I do not come to preach tolerance. The most unlimited freedom of religion is in my eyes a right so sacred that the word tolerance, which attempts to express it, appears to me itself tyrannical, since the existence of the authority that has the power to tolerate undermines the liberty of thought, for that which it tolerates, it might choose not to tolerate.”6 The following day Rabaut de Saint-Etienne came back to this point forcefully: “But Gentlemen, it is not even tolerance that I demand; it is liberty. . . . Tolerance! I ask that it be banned in turn, and it will be, this unjust word, which presents us as citizens worthy to be pitied, criminals to be pardoned.”7

This assault on “tolerance” might seem surprising, given how proponents of reform had previously used the term to criticize official persecution of religious minorities. Toleration developed as a practice and also as an idea throughout the eighteenth century, culminating in a series of measures in France, Prussia, the Hapsburg Empire, the Dutch Republic, and Great Britain that granted religious minorities limited civil rights.8 In France the revolutionary decade of the 1790s produced a paradoxical situation in which the religious liberty affirmed in Article 10 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man was compromised by the intermittent and sometimes violent repression of organized religious practice.9 This gap between theory and practice contributed to a further elaboration of the terms used to define religious liberty, a development that was passed on to the constitutional regimes of Napoleon, the Bourbon Restoration, and the July Monarchy. The experience of religious liberty in the post-revolutionary era took place in a historical context shaped by philosophical debates and state policies that evolved over the three centuries that began with the Reformation. It is beyond the scope of this book to trace in detail the history of religious liberty during this period, but an overview of how its definition and practice evolved from the Reformation through the early nineteenth century can suggest the complicated political and spiritual landscape within which the converts I study lived and moved.

In this chapter I will review the evolution of religious liberty in some major texts and in state policy from the sixteenth through the early nineteenth centuries. Starting in the sixteenth century French writers such as Montaigne, concerned with the violence and disorder that followed from the Protestant Reformation, developed an evolving set of concepts that form an important part of the history of religious liberty. These concepts, in particular liberté de conscience and tolérance, were not always clearly distinguished from each other, nor was their relationship fully articulated, an ambiguity that helps explain the confusion in the debates of 1789.10 But they played a major role in the philosophical discussions and state policies of the period and laid the groundwork for an expanding language of religious liberty enunciated during the French Revolution and embedded in the liberal political systems that emerged in the nineteenth century. Laying out the history of these terms is complicated, in part because of the shifting and fluid ways in which they were used and in part because they become entangled with the overarching concept of religious liberty, which concerns me here. In order to be clear, I will generally retain the French (tolérance, liberté de conscience, liberté religieuse, liberté des cultes), or place the specific English term in quotation marks, but will use “religious liberty” without emphasis to indicate the general category within which they operate.

The language and policies that define the history of religious liberty in the Old Regime troubled and engaged writers from Montaigne through Benjamin Constant on a personal as well as a theoretical level. As with the individuals whose religious choices will take up much of this book, religious liberty in the Old Regime was not only a philosophical issue involving state policy but a question of personal identity with profound existential resonance. Converts in the post-revolutionary decades made their decisions within a religious culture shaped by language and memory inherited from the Old Regime. My goal here is to examine this culture so we can better grasp the individual and collective dimensions of religious liberty that the Ratisbonne brothers, Ivan Gagarin, Félicité Lamennais, George Sand, and Ernest Renan grappled with and reformulated, thereby helping to define the modern experience of this fundamental right.

“Freedom of Conscience” in Montaigne

Montaigne’s Essays provide an invaluable starting point for probing the complicated ways in which religious liberty was understood in the crisis of the religious wars of sixteenth-century France (1562–1598) and in the aftermath of the horrors of the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre of 1572, when Catholic mobs in Paris slaughtered several thousand Protestants.11 Questions of religious identity and liberty were a preoccupation if not an obsession in this period, as Protestants and Catholics struggled against each other and sought to construct a political and religious regime that would restore peace and order in France. It is well known that Montaigne played a significant diplomatic role in mediating between Henri III, the Catholic League, and the Protestant forces led by Henri de Navarre.12 These efforts at reconciliation align with some of his reflections in the Essays, but this work reveals as well the ambiguity and tension built into debates over religious liberty. As sensitive and sympathetic as he is in confronting individual uncertainty and volatility, Montaigne gives serious weight also to the obligation of an individual to accept the religion of the state as essential for a well-ordered society.

Montaigne takes up directly the issue of freedom of conscience (liberté de conscience) in an essay of that title, which focuses primarily on the Roman emperor Julian the Apostate and his religious policies with regard to Christians.13 The essay opens, however, with a direct comment on the French civil wars. Although Montaigne approves of those “upholding the religion and constitution of our country,” he condemns those who reject a policy of moderation in favor of “decisions which are unjust, violent, and rash.” Shifting quickly from contemporary France to the Roman Empire, Montaigne claims that Julian was “harsh . . . but not cruel” in his treatment of Christians and in the end adopted a policy of liberté de conscience, hoping that this would create religious divisions that would weaken any potential resistance to his reign.14 The concluding passage of this essay is characteristic of Montaigne’s thought, with its subtle appreciation of the different strategic uses made of liberté de conscience and its ironic description of royal policy. “It is worth considering that, in order to stir up the flames of civil strife, the Emperor Julian exploited the self-same remedy of freedom of conscience which our kings now employ to stifle them. On the one side you could say that to slacken the reins and allow the parties to hold on to their opinions is the way to sow dissension broadcast: it is all but equivalent to lending a hand to increase it, since there is no obstacle to bar its course and no legal constraint to rein it back. For the other side you could say that to slacken the reins and allow the parties to hold on to their opinions is to soften and weaken them by ease and laxity; it blunts the goad, whereas rareness, novelty and difficulty sharpen it. Yet for the honor and piety of our kings I prefer to believe that, since they could not do what they wished, they pretended to wish to do what they could.”15 What are we to make of this curious and complex passage? As M. A. Screech notes, Montaigne’s concept of liberté de conscience in this essay can be taken to mean “freedom of worship granted to a rival sect of Christians,” that is to say, a policy of state toleration directed at a dissident religious minority. Although the term “conscience” carries with it a sense of individual right, compatible with Montaigne’s sympathetic consideration of the subjective self, in the context of the murderous religious wars of this period liberté de conscience was understood to refer primarily to the right of public worship.16 Furthermore, despite the positive tone in describing Julian’s policy, Montaigne’s conclusion emphasizes the different motives that led to arguments favoring this liberty, and the uncertain consequences that might follow from allowing it. Julian expected that a policy of liberté de conscience would lead to religious pluralism, shoring up his regime by dividing potential enemies into competing sects. For French kings (presumably Charles IX, Henri III, and Henri IV), however, liberté de conscience and pluralism would lead to social peace, as communities would be grateful for the chance to worship openly, free from persecution. Montaigne’s closing jab suggests that the Valois kings had chosen to accept the principle of liberté de conscience because they had no choice.

Montaigne’s concern with following his thoughts wherever they might lead produces an ambivalent posture that is both sympathetic and critical toward “freedom of conscience,” interpreted primarily from the perspective of rulers considering how best to maintain peace and harmony in their domains. Montaigne has thought his way into the royal policy that he supported, a process that results in a profound but telling paradox. Since enforcing the ideal of religious uniformity has generated civil war, he argues, kings (and their advisers?) have taken the less attractive but prudent alternative of allowing different cults to practice within their states. But in the course of making this move, kings (and their advisers?) turn pragmatic policy into principle. This subtle move may be an act, a pretense, but it nonetheless shifts the basis for defending “freedom of conscience” from practical necessity to social ideal.

The open-ended quality of Montaigne’s position on liberté de conscience is in sharp contrast to comments made elsewhere in the Essays. As Quentin Skinner and others have observed, Montaigne combines skepticism about absolute claims of religious truth with an insistence on the value of religious uniformity. This principle is affirmed at the outset of “An Apology for Raymond Sebond,” where Montaigne argues that the “novelties of Luther . . . would soon degenerate into loathsome atheism.” But the consequences of admitting religious difference would be social and political as well as religious: “Once you have put into [the hands of ordinary people] the foolhardiness of despising and criticizing opinions which they used to hold in the highest awe (such as those which concern their salvation), and once you have thrown into the balance of doubt and uncertainty any articles of their religion, they soon cast all the rest of their beliefs into similar uncertainty. They had no more authority for them, no more foundation, than for those you have just undermined; and so, as though it were the yoke of a tyrant, they shake off all those other concepts which had been impressed upon them by the authority of Law and the awesomeness of ancient custom.”17 Here Montaigne establishes religious uniformity as an ideal, even while his efforts at reconciling the warring factions in 1588, and his opposition to all forms of cruelty and violence, align him with the alternative policy of the politiques. This group was central to the eventual resolution of the religious wars, but their advocacy of toleration was prudential, based on the need to establish social peace. Given the terrible costs of the war, the politiques advocated a policy of tolerance as a lesser of two evils, an unfortunate concession made necessary in order to avoid the destruction of the commonwealth, “the only alternative to endemic civil strife.”18

Montaigne’s position was part of a powerful tradition that helps explain the qualified nature of the Edict of Nantes (1598), in which Henri IV allowed Protestants to worship within clearly specified geographical limits, looking ahead to a time when they would be “better instructed, or convinced in their consciences by the Holy Spirit of their error and heresy.”19 Not all those who argued in favor of “freedom of conscience” during the sixteenth century looked forward to the restoration of religious uniformity. But Sebastian Castellio, Guillaume Postel, and Jean Bodin, like Montaigne, nevertheless regarded religious pluralism with a heavy sense of regret.20 Defenders of “freedom of conscience” in the sixteenth century did not celebrate religious liberty as a source of healthy pluralism; they viewed it as a regrettable concession to the flawed human condition.

Montaigne’s skepticism led him to a qualified and complex defense of “freedom of conscience.” It led him as well to a paradoxical position critical of dissent, and an argument that individuals should accept the reigning religious system. Montaigne’s defense of religious uniformity is hard to reconcile with the profound exploration of the individual that is the dominant characteristic of the Essays. Montaigne comes back repeatedly and often to reflections that show him to be unsure of his position and open-minded about alternatives, a posture already on display in the conclusion of his essay on “freedom of conscience.” In “On Presumption” he writes that “philosophy never seems to have a better hand to play than when she battles against our presumption and our vanity; when in good faith she acknowledges her weakness, her ignorance, and her inability to reach conclusions.”21 Passages such as this make it easy to understand Charles Rosen’s comment that “fundamental to Montaigne is the conclusion that casts doubt upon itself, and thus reveals him at his most profound.”22 Taking Montaigne at his word, he manages to combine a fascination with the individual self, understood in all its volatility and uncertainty, with a sincere attachment to Catholicism, based on his respect for social convention and religious authority. In the Essays Montaigne captures the origins of the tense and ambiguous relationship between individuals, religious communities, and states whose evolution we will follow throughout this book.23

The Edict of Nantes, proclaimed by Henri IV in 1598 in order to settle over thirty years of intermittent violence and civil war, employs language similar to Montaigne’s in allowing for the protection of Protestant “freedom of conscience” that had been under assault during the wars of religion.24 Although the edict allowed Protestants limited rights of public worship and representation in courts, it looked forward to a future when God would be worshiped in the same form by everyone, thus replicating the ambiguous posture of Montaigne regarding religious minorities. Although it is often referred to as the “Edict of Toleration,” the document makes no use of tolérance, a term that had only recently been introduced to describe a state policy of permitting more than one religion, adopted out of necessity.25 By the end of the sixteenth century, in the Edict of Nantes, “freedom of conscience” had emerged as a principle concept for defending religious liberty, but at this stage it was laden with a sense of regret and constraint and referred ambiguously to both individuals and religious communities.

Bayle, Bergier, and Bourbon Policy in the Eighteenth Century

The revocation of the Edict of Nantes, enacted by the Edict of Fontaine-bleau (1685), was a catastrophic political mistake on the part of Louis XIV and his advisers. As a result, as many as two hundred thousand Protestants who had contributed to the prosperity of the kingdom fled the country, contributing to a wave of negative public opinion that fueled the international coalition that would oppose France over the next thirty years. Apart from such tactical considerations, it is difficult not to be shocked and disgusted by the repressive policies that led up to and followed the revocation. Bribes and harassment were designed to coerce conversions, practices that seem mild compared to the billeting of troops with Protestant families, which led thousands to convert in the early 1680s. I will not rehearse here the details of the repression that led up to and followed the revocation and that produced a major rebellion in the early seventeenth century.26 It is worth remembering that in several places local communities maintained peaceful relations for much of the seventeenth century, in the face of increasing royal pressure for religious uniformity.27 But the Edict of Fontainebleau was a landmark event, forcing Protestants to flee, convert, or go underground and provoking an intellectual response that led to a new stage in the history of religious liberty. To grasp this change no figure is more important than Pierre Bayle (1647–1706).

Bayle’s approach to religious freedom was not just an academic matter for him, for his life was marked by several movements across religious boundaries and a personal tragedy that resulted from the repression of the 1680s. The son of a Calvinist minster, Bayle converted to Catholicism as a young man before returning to the faith of his father and becoming a professor at the Protestant Academy in Sedan. In the face of the intensified persecution that began in 1681 Bayle fled to the Dutch Republic, where he published a series of works that helped establish the foundation for the Enlightenment, including the Lettre sur la comète (1682) and the Dictionnaire historique et critique (1696). Because officials could not prosecute Bayle for heresy, they arrested his brother Jacob, who died in prison in 1685, adding a personal dimension to Bayle’s assault on intolerance.28 The revocation of the Edict of Nantes provided the immediate context for Bayle’s groundbreaking defense of religious liberty in his Philosophical Commentary on These Words of the Gospel, Luke 14:23, ‘Compel Them to Come In, That My House May Be Full’ (Commentaire philosophique sur ces paroles de Jésus-Christ: Contrains-les d’entrer) (1686).29

Bayle’s work is an extended refutation of the Catholic interpretation of the passage from the Gospel of Luke (14:23) where Jesus instructs his listeners with the parable of the wedding feast to which the invited guests refuse to come. After the host has replaced those on the guest list with the poor, lame, and blind there are still places left at the table, which leads Jesus to order his servant to “go into the roads and lanes, and compel people to come in, so that my house may be filled.” Catholic apologists, starting with Augustine, had used this passage to defend the state repression of heresy and the enforcement of religious uniformity, an argument renewed in the wake of the Edict of Fontainebleau. Bayle’s attack against this position is based first of all on its failure to meet a basic standard of reason that must be applied to religious claims. Bayle is careful to identify reason as a God-given ability, not an attribute derived solely from human nature, though such a claim was not enough to protect him from charges of atheism. But for Bayle coerced acts have no religious value, for the nature of religion requires first of all “a certain persuasion in the soul with regard to God,” which would then manifest itself in “outward signs.” But if “these outward signs exist without that interior state of the soul which answers to them, or with such an inward state as is contrary to them, they are acts of hypocrisy and falsehood, or impiety and revolt against conscience.”30 From this perspective a state policy of intolerance and repression forces a division between the conscience and outward behavior, an unreasonable posture and therefore an inappropriate interpretation of Luke. Bayle draws as well directly from biblical texts and insists that any reasonable interpretation of the New Testament would conclude that the “principal character of Jesus Christ . . . the reigning qualities of his soul, were humility, meekness, and patience,” attributes that clearly contradict any policy of force carried out in his name.31

Bayle does not deny that clergy and statesmen had the right to make efforts to convince dissenters that they were mistaken, but no such arguments could rely on force. In taking this position Bayle uses the term “freedom of conscience” as an individual right as the basis for a state policy he refers to as “tolerance.” “That it is the duty of superiors to use their utmost endeavors, by lively and solid remonstrances, to undeceive those who are in error; yet to leave them the full liberty of declaring for their opinions, and serving God according to the dictates of their conscience, if they have not the good fortune to convince them: neither laying before them any snare or temptation of worldly punishment in case they persist, nor reward if they abjure. Here we find the fixed indivisible point of true liberty of conscience [liberté de conscience]; and so far as any one swerves more or less from this Point, so far he more or less reduces tolerance [tolérance].”32 Bayle’s Commentary is a passionate defense of “freedom of conscience” as the basis for a policy of “toleration” of religious minorities and represents a major shift in the ways in which these terms had been deployed in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Unlike Montaigne, Bayle uses both terms in his work, and again unlike Montaigne, he defends them without the irony of the Essays. Barbara de Negroni sees Bayle’s work as a “Copernican revolution” in the history of religious liberty, insofar as “tolerance is no longer based on objective criteria, but on the position of the subject; it derives not from revealed dogmas, but from the rights of conscience.”33 On the basis of his robust argument for “freedom of conscience” and “toleration” Bayle perhaps merits Jonathan Israel’s judgment that he was a key figure in a “radical Enlightenment” characterized by rationalism, religious skepticism, and political principles that form the basis for modern liberal and democratic societies.34 But Bayle at one point does pull back from a “radical” position and asserts, as does John Locke, a “moderate” in Israel’s terms, that atheists should not share in the “freedom of conscience” granted to Christians.35 This position does not fit well with the overall argument in his Commentary, nor with Bayle’s other writings that defend the possibility of the “virtuous atheist.” Based on such inconsistencies, Israel dismisses Bayle’s comment on atheism as “de rigueur,” suggesting that his position was not meant to be taken seriously, since it is so deeply incompatible with his otherwise unequivocal defense of freedom of conscience.36 Perhaps this is so, but it is also possible that Bayle meant what he wrote, a position that would put him more in line with Locke, and with a prior tradition in which defenders of toleration made a point to exclude atheists, seen as incapable of participating in the civil order.37 However we interpret this passage, it is telling that Bayle was still willing to make at least some concession to the right of the state to enforce a certain level of religious belief.38 Nonetheless, Bayle’s powerful endorsement of “freedom of conscience” and “tolerance” formed the basis for subsequent defenses of religious liberty, while the persecution of the Huguenots that was renewed in 1685 kept the focus of such discussions on the issue of state policy toward the public worship of religious minorities. “Freedom of conscience” was an individual right, but its exercise was understood to take place in specific communities whose “toleration” by the state was the principal concern.39

The arguments in favor of “freedom of conscience” and “tolerance” did not go unchallenged. At the General Assembly of the Clergy in 1651 the bishop of Comminges called on the young Louis XIV “to banish from his kingdom this unfortunate liberty of conscience, which destroys the true liberty of God’s children.”40 Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries “semantic associations of tolérance were largely negative, so the strongest traditions that French political culture inherited from its medieval past were profoundly antithetical to the acceptance of religious division within the kingdom.”41 This tradition of hostility to a policy of toleration endured throughout the eighteenth century, as illustrated in the Dictionnaire de théologie of the abbé Bergier (1718–1790), a standard manual well into the nineteenth century as well. Bergier’s position is particularly significant because it came from a writer identified with the “Catholic Enlightenment,” known for his engagement with the philosophes and their discussions of reason and nature as the basis for knowledge.42 Bergier subjected Bayle’s concept of “freedom of conscience” to what he understood to be a withering attack, arguing that to accept the position that we are obligated to follow our conscience wherever it leads opens the door to heresy, crime, and disorder. Conscience can claim its rights over us only when it has been properly instructed in the truths of the Catholic faith. “It is not true that in forcing [Protestants] to allow themselves to be instructed, one obliges them to act against their conscience; they are constrained only to be enlightened and reformed; when they refuse it is not because of their sensitivity to their conscience, but the result of pure obstinacy.” For Bergier, claims made on the basis of “freedom of conscience” were a mere pretext for Protestants who “wanted to profess their religion publicly, to exercise with the greatest possible display a religion different from the dominant religion, to take possession of churches, banish Catholics, hunt down and exterminate priests, as they have done in those places where they became masters.”43 As for “tolerance,” Bergier regarded as “an absurdity” the idea that “all religions ought to be equally permitted, none ought to be dominant or favored over another, and every individual ought to decide for himself whether or not to have one.”44 Bergier clearly grasped the principles of “freedom of conscience” and “tolerance” and just as clearly dismissed them as incompatible with Catholic orthodoxy.

Although Protestants had certainly acted with intolerance and violence during the wars of religion, by the middle of the eighteenth century Bergier’s description of them much more aptly described recent practices of the French state. The revocation of the Edict of Nantes was celebrated by the Catholic clergy as a triumph of truth over heresy, and when Protestant communities in the Cévennes mountains in southern France resisted they were brutally repressed in a bloody civil war.45 The death of Louis XIV in 1715 led to a brief respite, but when Louis XV came of age one of the first acts of his reign was to reaffirm the absolute prohibition of any religion other than Catholicism in a decree of 1724: “It is our will that the Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman Religion alone be practiced in our Kingdom, and all the lands under our authority; we forbid to all of our subjects of any estate, quality, and condition to exercise in any way a religion other than Catholicism, and to gather for such a purpose in any place under any pretext, under pain of being sentenced for life to the galleys, for men, and to be shaved and imprisoned for life, for the women.”46 Despite these prohibitions and threats, Protestant communities managed to survive in what became known as the “church of the desert,” but without any legal protection they were dependent on the forbearance of local officials. A crackdown occurred, for example, in Bordeaux in 1749, where the courts sentenced nine men to life terms in the galleys, and their wives to be shaved and imprisoned, for having been married in a Protestant ceremony.47 In the second half of the eighteenth century such persecution was still possible, as evident in the famous Calas affair, discussed later in this chapter. But after 1750 what had been formerly regarded as orthodox doctrine and standard state policy in support of “one King, one law, one faith” came increasingly to be regarded as unreasonable, cruel, and counterproductive. But even as “freedom of conscience” and “tolerance” became more acceptable, they continued to evoke complex attitudes and unresolved tensions about the meaning of religious liberty.

Voltaire, Rousseau, and the Encyclopédie: Tolérance and Conscience in the Enlightenment

For the philosophes religious liberty was a central concern, evident in three key texts that all appeared within the two-year period of 1762–1763: Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Emile and The Social Contract, first published in 1762, and Voltaire’s Treatise on Tolerance, which appeared in 1763.48 Voltaire and Rousseau were writing in a context in which intolerance was still state policy, with the Edict of Fontainebleau (1685) officially in effect. But in the second half of the eighteenth century, Protestant communities began to profit from a policy of benign neglect.49 When this de facto toleration was abandoned it was shocking and offensive in part because open persecution had become unusual. This emerging experience of religious liberty was nonetheless fragile because it could still be and was at times violated by an intolerant state. The philosophes regarded Bayle with enormous respect, and their defense of “freedom of conscience” and its link to “toleration” follows closely his reasoning. But Bayle also devoted hundreds of pages to a close reading of the church fathers, understood as authorities who could help provide the proper interpretation of Luke 14:23. For Voltaire and Rousseau, scriptural texts and church fathers were irrelevant in considering religious liberty, which derived from a natural right inherent in each individual. But in their aggressive and rationalistic defense of religious liberty Voltaire and Rousseau still struggled to articulate clearly the nature of an individual right to freedom of conscience in its relationship to the duties to family, community, and state.

Voltaire, in his Treatise on Tolerance, condemns in the most forthright manner the persecution of the Protestant religious minority in France. In doing so he relies on the concepts of liberté de conscience and tolérance inherited from Bayle, but he does not distinguish these with the same clarity as his predecessor, and he uses them interchangeably, in a manner similar to some of the speeches in the National Assembly of 1789. In chapter 5, for example, when he proposes that Germany demonstrates how tolerance produces social harmony, he refers to liberté de conscience, even though the context suggests he is concerned with communal and not individual rights. For Voltaire, Germany would be “a desert covered with the bones of Catholics, Evangelicals, Reformers, and Anabaptists, all massacred by each other, were it not for the Peace of Westphalia which eventually established in the country the right to freedom of conscience.”50

Voltaire may have been sympathetic to the freedom of individual religious choice, but in the Treatise on Tolerance he tends to look aside from this issue to focus instead on Catholic persecution of the Protestant community. As with Bayle, he saw freedom of conscience as inextricably bound to the issue of state toleration of religious dissidents, which remained in the foreground of his thinking. This tendency to look first of all at the state in considering religious liberty can be seen in Voltaire’s interpretation of the treatment of the Calas family by the French judicial system, the cause célèbre that prompted Voltaire to write the Treatise.51 In his essay Voltaire reviews the tragic story, in which a mentally disturbed son in a Protestant family who had perhaps been considering conversion to Catholicism committed suicide. The Parlement of Toulouse subsequently found the father guilty of murder on flimsy evidence, which led to his execution and the persecution of the entire family. For Voltaire and his enlightened colleagues, the Calas affair became a symbol of official Catholic intolerance toward a minority community. But Voltaire spends no time in his essay explicitly defending liberté de conscience from the perspective of individual choice, despite the pivotal role this played in the affair. For Voltaire, religious liberty centered on the right of Protestants to worship publicly and to be protected against state violence, with individual freedom of conscience a prior but unexamined assumption. Voltaire condemns the Catholic judges of Toulouse for intolerance directed at the Calas family and the Protestant community. But he never probes the basis for their unreasonable decision, the conviction on the part of Catholics that families would regard with murderous hatred a member who chose to leave the family’s religion. The Catholic judges of Toulouse could not imagine that Protestants might accept such an act of communal disloyalty based on the rights of individual conscience. Voltaire did not bother constructing an argument against such an assumption, which would have distracted him from his main goal of advocating for a policy of state tolerance.52 Voltaire’s passionate defense of toleration is echoed in Laborde’s speech in the debate over Article 10, but in that debate as well the communal dimension of religious liberty, not the freedom of the individual conscience, remains the principal focus.

The freedom of the individual is very much in the foreground of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s reflections on religious liberty, but his writings on this topic further illuminate the tension inherent in this issue as it was understood in the eighteenth century.53 Rousseau’s struggle to make sense of religious liberty comes as no surprise given the complicated religious journey he took in his own life, as described in his Confessions. Rousseau abandoned his Calvinism in 1728 as a young man of sixteen, converted not by any change in his religious convictions but because of the charm of a young woman, Mme de Warens, who later became his mistress.54 After their initial, brief meeting, Mme de Warens, herself a convert supported by the king of Savoy because of her success as a proselytizer, sent Rousseau off to a hospice for converts in Turin. There he would be instructed and accepted into the Catholic faith, but the completion of his conversion was a painful process in which a supposedly free choice of a new religion was compromised, even coerced, by the circumstances in which he found himself.

In the Confessions Rousseau describes a horrific institution whose ignorant teachers failed to convince him of the truths of Catholicism, and which was a haven for pederasts, one of whom attempted to seduce him.55 Impoverished and alone in the world, Rousseau nonetheless went through with the charade of a conversion that was fundamentally insincere. Reflecting on his decision to convert in the Confessions, Rousseau takes a position that belies his own experience: “It is clear, I think, that for a child, and even for a man, to have a religion means to follow the one in which he is born.”56 While it is easy to see why Rousseau would take such a position given the troubled transition that he lived through at Turin, affirming the value of religious constancy, of fidelity to the faith of one’s fathers, nonetheless runs counter to Rousseau’s commitment to independence and liberty in matters of religion, a tension that is developed in more detail in Emile and The Social Contract.

In Emile Rousseau’s struggle with religious liberty takes center stage in book 4, which includes the famous “Creed of a Savoyard Vicar.” In scrutinizing this text from the perspective of religious liberty we should recall Rousseau’s general principle that individuals who have reached adolescence, at twelve or thirteen, should learn through a process of independent discovery. As articulated in book 3, Rousseau applies this principle to the study of nature, but the language suggests as well an underlying commitment to intellectual independence: “Put the problems before him and let him solve them himself. Let him know nothing because you have told him, but because he has learnt it for himself. . . . If ever you substitute authority for reason he will cease to reason; he will be a mere plaything of other people’s thoughts.”57 As we shall see, Rousseau struggles to reconcile this principle, which might lead to a defense of the absolute liberty of conscience in religious matters, with the right of the father to raise his children in the religion he chooses and the need for an overarching set of religious values embraced by all members of a society.

In Emile Rousseau’s pupil has been raised to be a student of nature, which he discovers on his own, though with the help of the guiding and at times intrusive hand of a tutor. But while the tutor subtly assists and shapes the education of Emile, he adamantly refuses to present him with doctrines that do not arise from personal experience. Consequently, the regime advocated by Rousseau includes no formal religious education, a point that Rousseau acknowledges might surprise his readers: “At fifteen he will not even know that he has a soul, at eighteen even he may not be ready to learn about it.” Such ignorance is an advantage compared to the “heart-breaking stupidity” that comes from the mindless memorization of the catechism. For Rousseau, a child “understands so little of what he is made to repeat that if you tell him to say just the opposite he will be quite ready to do it. . . . When a child says he believes in God, it is not God he believes in, but Peter or James who told him that there is something called God.”58 Not only are religious ideas mindlessly parroted, they vary widely from place to place; faith is, according to Rousseau, a matter of geography.59 This variability of religious ideas carries with it an insidious consequence, for children are instructed to disparage the religions of other people and thereby form ideas of God that are “mean, grotesque, harmful, and unworthy.” This religious formation lasts throughout their lives, so that “as men they understand no more of God than they did as children.”60

Rousseau’s ideal education, in which children would not receive any religious instruction, raised a difficult question. If the religions fathers teach to children, based on the accidental circumstances of their place of birth, are to be rejected, what should take their place? In what religion should Emile be raised? At first Rousseau’s answer seems clear: “What religion shall we give him, to what sect shall this child of nature belong? The answer strikes me as quite easy. We will not attach him to any sect, but we will give him the means to choose for himself according to the right use of his own reason.”61 It is precisely at this point in Emile that Rousseau breaks away from a style in which he directly addresses the reader and passes the word to the famous “Savoyard Vicar,” a text in which Rousseau recalls (and reinvents) his own experience in Turin and the help he received from a sympathetic and heterodox Catholic clergyman.62 In Emile Rousseau passes over the fact that he actually went through with his conversion and instead emphasizes his skepticism and despair as a young man who had come to see religion as “a mask for selfishness, . . . its holy services but a screen for hypocrisy.”63 The “creed of the Savoyard Vicar” has become one of the most famous of Rousseau’s texts, a powerful argument for a religion that rejects the divisive dogmas of established churches in favor of a belief shaped by the feeling individual’s communing with a harmonious natural order. Rousseau’s theological speculations, which he intended as a refutation of atheism, earned him the condemnation of the Paris Parlement, which reacted against his explicit critique of ritual and revelation.64 Forced to flee to Switzerland to avoid prosecution, Rousseau paid a personal price for embodying his insistence in Emile that the heart of all authentic religious experience is the individual human conscience, the point where the divine and the human meet: “Conscience! Conscience! Divine instinct, immortal voice from heaven; sure guide for a creature ignorant and finite indeed, yet intelligent and free; infallible judge of good and evil, making man like to God!”65 The Savoyard’s theological emphasis on the divinized individual conscience leads him inevitably back to an affirmation of the absolute right of the individual to choose his religion: “Let us therefore seek honestly after truth; let us yield nothing to the claims of birth, to the authority of parents and pastors, but let us summon to the bar of conscience and reason all that they have taught us from our childhood.”66 Unlike Voltaire, in Emile Rousseau approaches religious liberty through a concentrated exploration of the individual conscience.

This prescription for the pursuit of religious truth apart from “parents and pastors” seems clear enough, but the Savoyard Vicar soon confronts an obstacle that leads him to an entirely different place from where he (and Rousseau) began. The vicar describes his long investigation into the arguments in favor of the different religions, which depend on competing claims of absolute truth. But despite his most strenuous efforts, he is unable to come to any certain conclusion. And if the vicar, with his education and intelligence, is unable to decide, what of the common workman? In language that recalls the anxiety of Montaigne about religious pluralism, Rousseau writes that if people were to indulge themselves in a quest for certain religious truth, the result would be a social catastrophe: “Then farewell to the trades, the arts, the sciences of mankind, farewell to all the peaceful occupations; there can be no study but that of religion, even the strongest, the most industrious, the most intelligent, the oldest, will hardly be able in his last years to know where he is; and it will be a wonder if he manages to find out what religion he ought to live by, before the hour of his death.”67 Religious freedom if taken seriously and pursued as a duty thus leads to social chaos, not to mention personal despair. Here, as with Montaigne, an appreciation of the value of the individual conscience runs up against the need for harmony and social order.

The Savoyard Vicar’s own solution after his failed religious quest is to accept an “unwilling scepticism” that is “in no way painful to me, for it does not extend to matters of practice.”68 Speaking more generally, the vicar takes a position that is surprising, even shocking, when compared with his earlier castigation of the “heart-breaking stupidity” of priests who teach children their catechism lessons, which might contain ideas about God that are “mean, grotesque, harmful, and unworthy.”69 For the vicar now states that “I regard all individual religions as so many wholesome institutions which prescribe a uniform method by which each country may do honor to God in public worship; institutions which may each have its reason in the country, the government, the genius of the people, or in other local causes which make one preferable to another in a given time or place. I think them all good alike, when God is served in a fitting manner.”70 Moreover, since all religions are “wholesome” and “good alike” there is no reason for people to change from the one in which they were born. In fact, “to ask anyone to abandon the religion in which he was born is, I consider, to ask him to do wrong, therefore to do wrong oneself. While we await further knowledge, let us respect public order; in every country let us respect the laws, let us not disturb the form of worship prescribed by law; let us not lead its citizens into disobedience; for we have no certain knowledge that it is good for them to abandon their own opinions for others, and on the other hand we are quite certain that it is a bad thing to disobey the law.”71 As he nears the conclusion of their conversation, the vicar advises Rousseau to “go back to the religion of your fathers, and follow it in sincerity of heart, and never forsake it. . . . In our present state of uncertainty, it is an inexcusable presumption to profess any faith but that we are born into, while it is treachery not to practice honestly the faith we profess.”72 Over the course of his analysis of religious liberty in Emile Rousseau has thus come to a position that contradicts his earlier embrace of the absolute authority of the individual conscience.

Religious liberty is also evoked in powerful but ambiguous terms in The Social Contract, the other famous text that Rousseau published in 1762.73 In the closing pages of the Contract Rousseau discusses in a more schematic fashion the tension between individual conscience and public cult that he explored in depth in Emile. In his chapter on “Civil Religion” he draws a sharp contrast between “the religion of man and the religion of the citizen.” The first, “without temples, altars, or rites, [is] limited to the purely inward worship of the supreme God and to the eternal duties of morality.” The religion of the citizen, on the contrary, “has its dogmas, its rites, its outward form of worship prescribed by law.” Rousseau also describes a third form of religion, exemplified in Roman Christianity, in which both the state and the church claim the authority to prescribe laws. Rousseau dismisses this hybrid as “obviously bad” because it “breaks down social unity. . . . All institutions that place man in contradiction with himself are worthless.”74 In developing his thoughts on the religion of the state Rousseau repeats ideas found in Emile, but in sharper language that adds a punitive dimension that the Savoyard Vicar avoided. The articles of this civil religion are to be determined by the sovereign, and all are obliged to follow them, for otherwise “it is impossible to be a good citizen or a faithful subject.” Citizens who refuse to accept the civil religion are liable to banishment and death. But the passage in which Rousseau establishes the right of the sovereign to punish religious dissent is a telling illustration of the curious and convoluted way in which Rousseau thought about religious liberty: “Without being able to obligate anyone to believe [the articles of a civil religion], the sovereign can banish from the state anyone who does not believe them; it can banish him not for being impious but for being unsociable.” Despite his attempt to preserve the right of the individual conscience, Rousseau condemns citizens who at one time accepted the civil religion and then rejected it. In granting the state such coercive power, Rousseau seems to contradict prior statements that condemned state religions for making people “bloodthirsty and intolerant” and for believing that “[the state] performs a holy act in killing anyone who does not accept its gods.”75 In The Social Contract, as in Emile, Rousseau fails to reconcile his commitment to the rights of the individual conscience with those of the state, and as in Emile he ends up in a paradoxical position in which the individual can be seen as torn by a choice between faithfulness to his conscience or to his state. Rousseau’s convoluted reasoning on religious liberty, and his deference to the power of the family and the state to impose and regulate religious belief, helps explain his lack of interest in participating in the defense of toleration along the lines of Bayle or Voltaire. He took no great interest in the Calas affair and on one occasion refused the appeal of the Protestant community to intervene in favor of the pastor Rochette, imprisoned for leading clandestine services and eventually hanged.76 In responding to this appeal Rousseau opposed freeing any prisoner of the state “even if he has been wrongly detained.” Any such attempt “is a . . . rebellion that cannot be justified, and those in power always have the right to punish it.”77

Emile and The Social Contract are puzzling texts in their consideration of religious liberty. On the one hand Rousseau unequivocally affirms the absolute right of the individual conscience to make a free choice of religion, advises readers that in an ideal world children should not be given a religious education, and ridicules the grotesque diversity of religious beliefs. On the other hand he insists that children ought to be raised in the different religions of the countries where they are born, stay faithful to the religions prescribed by law, and face banishment or death for becoming religious dissenters.78 Rousseau’s contending positions expose the enduring tension between individual conscience and the claims of family, church, and state. This conflict surfaces again in the confusing exchanges between Mirabeau and Rabaut de Saint-Etienne on the one hand and the abbé d’Eymar and his supporters on the other in the debates of August 22–23. The public chaos in the National Assembly over how to understand religious liberty echoes as a public manifestation of the contradictions of Rousseau.

It seems inevitable that conscience and tolérance would be taken up in the Encyclopédie, the central text of the Enlightenment, edited by Diderot and d’Alembert, that began appearing in 1751. Louis de Jaucourt’s article on liberté de conscience and Jean-Edme Romilly’s on tolérance defend the rights of individual judgment and religious minorities in terms that recall arguments drawn from Bayle, whose work is cited favorably by Romilly.79 Conscience earns two entries, one by Jaucourt under the rubrics Philosophie, Logique, Métaphysique, which defines the term as the equivalent of the English “consciousness” and restricts it to the self-awareness of one’s perceptions. The second entry, by an anonymous author under the rubrics Droit naturel, Morale, defines conscience as “the judgement that each person makes with regard to his own actions, compared with the ideas that he has of the law that binds him.” But this faculty is also responsible for establishing the standard it will apply in the first place, which explains why this “interior forum” is not a stable entity, for it might at different times be “decisive, doubtful, correct, bad, probable, erroneous, irresolute, scrupulous, etc.” Individual reason is accorded an important role in the operation of conscience but is also potentially limited by the value attached to external sources of authority. It is once again conscience that establishes how to balance these forces. Conscience is thus a fundamental source of moral judgment and personal identity but also observed by the individual who possesses it, and so is separated from as well as identified with the self.80 All of the converts I study struggled with their consciences, understood as both a source of their religious freedom and a constraint on it. In reflecting on this dilemma they were working within the rich conceptual vein inherited from the Enlightenment, trying to understand how a conscience could be, as Rousseau put it, “a sure guide for a creature ignorant and finite indeed, yet intelligent and free.”81

From Tolérance to Liberté des Cultes

In the years just before the revolution royal policy finally made a small but significant concession to the rights of religious minorities in the Edict of Versailles, issued in November 1787. Influenced by public officials, including his minister Chrétien-Guillaume de Lamoignon de Malesherbes, Louis XVI declared that Protestants would now be able to register their marriages legally without going through the subterfuge of a Catholic ceremony.82 The edict, however, was narrowly conceived as a way of granting Protestants the right to pass property to their heirs and made no reference to either “freedom of conscience” or “tolerance.” Public worship by Protestants was still banned, Protestant communities were not recognized as having any legal standing, and ministers could not dress in any way to distinguish themselves. In its first article the decree reaffirmed that “the Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman religion will continue to enjoy alone, in our kingdom, the right to public worship.” This policy of civil but not religious tolerance had been proposed by Jansenist writers beginning in the 1760s but by the end of the eighteenth century no longer satisfied Protestants such as Rabaut de Saint-Etienne, who defended “freedom” as an alternative to “toleration” in his speech to the National Assembly on August 23, 1789.83

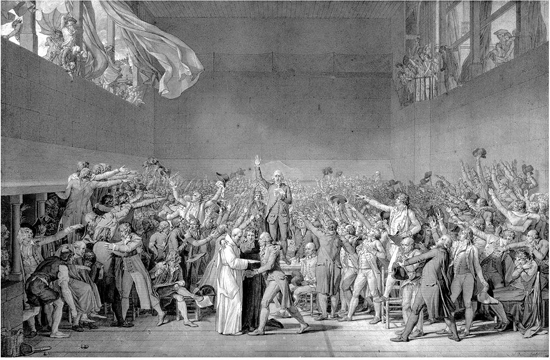

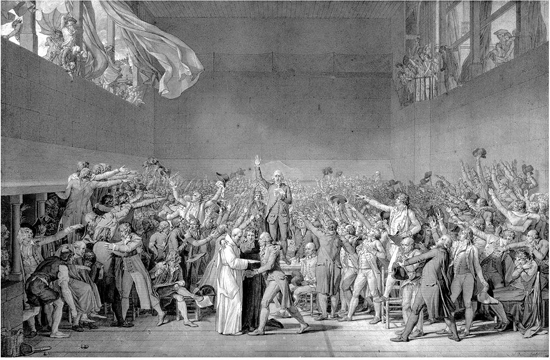

The debate over Article 10 with which this chapter began testifies to the central importance of religious liberty for revolutionaries and their opponents from the outset of the French Revolution. Jacques-Louis David’s famous design for a monumental painting of the Tennis Court Oath, presented at the Salon of 1791, offers melodramatic confirmation of the revolutionary concern for religious liberty and the tension between public pressure to conform and the rights of the individual conscience. David celebrates the pivotal moment on June 20, 1789, when the mayor of Paris, Bailly, led the delegates of the National Assembly in swearing an oath to write a constitution for France. In the foreground just below Bailly we see the Protestant minister Rabaut de Saint-Etienne embracing two Catholic clergymen, the Dominican monk Dom Gerle and the abbé Grégoire. For David, religious reconciliation shares the stage with popular sovereignty as a major aspiration of the French Revolution. But on the far right of the work a small scene unfolds that reveals a troubled atmosphere in which individual liberty is challenged by the pressure to conform. As the delegate Martin sits with his arms folded, refusing to join in the oath, the deputy Camus, a leading specialist on religious questions, grabs his arm in an apparent attempt to coerce his taking of the oath. But Camus is at the same time restrained by another delegate, willing to tolerate Martin’s dissent. David here illuminates the contested boundary between public adherence to the revolution and the right of individual dissent, an issue linked to the desire for religious reconciliation on display in the center of the work.84

Figure 1. Jacques Louis David, The Oath of the Tennis Court. Château de Versailles et de Trianon. © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY.

By 1791 the challenge to unity that David confined to a corner had taken center stage, fueled first of all by conflicts over the status of the Catholic Church. An attempt by Dom Gerle to have Catholicism named as the state religion failed to win a majority in the National Assembly in April 1790, leading to a tumultuous session that recalled the debate over Article 10 of the previous year. The “Dom Gerle affair” set the stage for the stormy debate over the Civil Constitution of the Clergy (July 1790), in which the French state asserted its authority over the church by redrawing diocesan boundaries to reflect the new system of departments and mandating that bishops and priests be elected rather than named by ecclesiastical authorities. This political debate produced a social and religious crisis when the National Assembly demanded that the clergy swear an oath to uphold a reform that many rejected as unwarranted state interference with the church. By 1791 France was moving toward a period of religious repression and civil war rather than religious liberty and reconciliation.85

The combination of resistance by “refractory” clergy who refused to swear the oath to the new constitution and the outbreak of war in April 1792 produced a toxic atmosphere in which many revolutionaries became convinced that Catholic dissidents posed an existential threat to the new regime. The repression that followed led to the abolition of religious orders, the exile and execution of thousands of clergy, the closing of churches, and an active campaign of dechristianization.86 All of these policies were carried out by regimes that continued to embrace the principle of religious liberty, perhaps an unsurprising but nonetheless a disheartening irony.

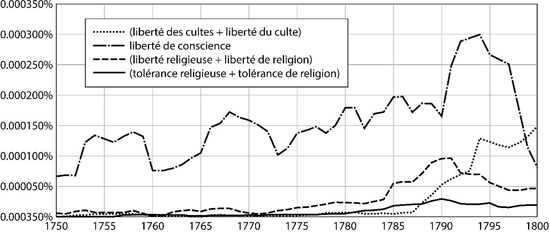

In the Constitutions of 1791, 1793, and 1795, and in a series of laws passed during the regimes of the Convention (1792–1795) and the Directory (1795–1799), religious liberty was repeatedly affirmed in principle even while it was often compromised by repressive measures.87 The turbulent and often violent conflicts over religion during this period contributed to the further articulation of language used to define religious freedom. Although its origins as a phrase can be dated at least to the 1770s, “religious liberty” (liberté religieuse) emerged as an important category in the 1780s and 1790s, a shift reflected dramatically in the debates over Article 10 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man (figure 2). This phrase had the advantage of establishing the freedom of religious practice as a fundamental human right and not as a gift granted by an authoritarian regime. At the same time it brought together both the individual and collective dimensions of religious liberty, linking external practice to personal belief. This conflation is evident in the controversies of the 1790s on the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and the drafting of new constitutions. In a report on religious tolerance to the National Assembly of 1791, for example, the ex-bishop of Autun Talleyrand called for a decree that would give Catholic clergy who had refused to take the oath to the constitution the right to say Mass in parish churches, providing that they did not trouble the public order by opposing the constitution: “We reject this hypocritical toleration which would allow freedom of thought but not its expression in public acts. Let men no longer be obligated to lie to themselves.” In accepting Talleyrand’s report the assembly passed a law drafted by the abbé Sièyes allowing refractory clergy to hold public religious services and announcing that “the principles of religious liberty . . . are identical with those that have been recognized and proclaimed in the Declaration of the Rights of Man.”88 Within a few months the Legislative Assembly would reject this irenic posture in favor of harsher treatment of the refractory clergy, a repressive policy that could nonetheless be defended on the basis of the limiting final clause of Article 10. As the delegate Pierre-Toussaint Durand de Maillane insisted, “No particular right must prevail over the right of an entire Nation to tranquility and public order, to which even the freedom of religious opinions has been subjected to in the Declaration of Rights.”89

Figure 2. Ngram of terms referring to religious liberty, 1750–1800. The percentages on the left are based on the total number of two- and three-word phrases in the entire corpus of French works available on Google Books for this period. Search conducted in June 2016.

The ambiguous character of “religious liberty” helps explain the emergence of another linguistic innovation, the “liberty of cults” (liberté des cultes), which referred specifically to the public manifestation of religion. This phrase made an appearance in the 1750s in a text published in The Hague, praising the city because its liberté des cultes allowed two young people from different religions to marry.90 But it came into common use in French publications only in the 1780s, when it was used by Rabaut de Saint-Etienne and Condorcet, among others, to argue for the rights of Protestants in France. In the 1790s liberté des cultes surpassed liberté religieuse as the common term used to specify the right to worship publicly according to one’s beliefs (figure 2).91 Constitutions adopted this language, as in the “premier titre” of the Constitution of 1791, which guaranteed “the freedom of everyone to practice the religious cult to which he belongs.” Subsequent decrees and constitutions affirmed the liberté des cultes even while they placed severe restrictions on public practice. After the fall of Robespierre and the end of the Terror, the abbé Grégoire boldly defended the liberté des cultes in a speech to the National Convention in which he claimed that such freedom currently did not exist in France and that religious persecution was the primary explanation for counterrevolutionary activity.92 Boissy d’Anglas’s Rapport sur les libertés des cultes, presented to the Convention in February 1795, declared that “no practice of any cult can be prohibited” and condemned attacks against Catholics during the recently concluded Terror, which he compared to the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre. But his report also called for the prohibition of any religious ceremony in public spaces.93 The constitution establishing the Directory failed to include freedom of religion as one of the fundamental rights, although it did announce in Article 354, as one of its “general dispositions,” that “no one can be prevented from exercising, in conformity with the laws, the cult he has chosen. No one can be forced to contribute to the expenses of a cult. The Republic provides no funds for them.”94 This language suggests the continuing suspicion leaders of the republic directed at the Catholic Church, now effectively separated from the state. Despite such efforts, Catholicism experienced a revival after 1795, taking advantage of a widening space for religious freedom that was increasingly defined in the language of liberté des cultes.95 As Suzanne Desan demonstrates in her groundbreaking work on religion during the revolution, ordinary citizens referred explicitly to the liberté des cultes in claiming the right to public worship in the 1790s.96 Even fervent counterrevolutionaries such as the abbé de Barruel invoked this newly defined freedom as an instrument for attacking the revolutionary regime when it sought to repress Catholic practice.97 Barruel stopped far short of defending liberté des cultes as a worthwhile concept on its own terms. He was interested only in pointing out the hypocrisy of the Jacobins, not in defending religious liberty. But his backhanded endorsement of liberté des cultes nonetheless suggests the seductive appeal of a right that was increasingly accepted even while its meaning and application remained ambiguous.

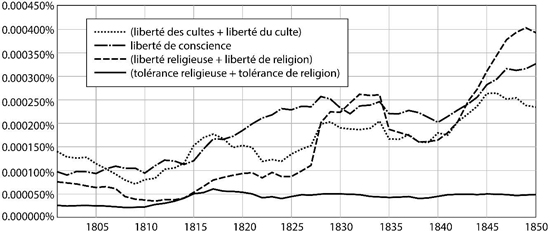

Napoleon adopted this new term as his own in swearing to defend the liberté des cultes in his coronation oath of 1804: “I swear to maintain the territorial integrity of the Republic and to respect and preserve the laws of the Concordat and the liberty of cults.”98 The prominent position of liberté des cultes in the oath attests to its importance as a principle, but Napoleonic practice in fact placed severe limits on the churches. As first consul (1799–1804) Napoleon recognized both the Catholic revival and the importance of religious peace for the stability of the new regime of the Consulate (1799–1804) and so negotiated the Concordat of 1801, which would govern relations between the French state and the Catholic Church until their separation in 1905. The first article asserts that “the Catholic, apostolic and Roman religion will be freely exercised in France” but immediately adds a caveat almost identical to the one that qualified Article 10 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man: “Its cult will be public, conforming to the police regulations that the Government judges necessary for public tranquility.” The concordat pointedly did not make Catholicism the official religion of the state, declaring only that it was the “religion of the great majority of French citizens.”99 Although the treaty with Rome granted freedom of religious exercise to Catholics following a decade when their right to public worship had been periodically denied, this liberté du culte was at the same time compromised by the tutelary power awarded to the state. Catholic priests would be paid officials, as financial compensation for the seizure of church lands, a measure that made the clergy liable to control by the state. Bishops would be nominated by the head of state, with the pope investing them with their spiritual authority. The Organic Articles, attached to the concordat before it was officially promulgated in 1802, further enhanced state power, restricting meetings between bishops and their communication with Rome. Official relationships were established as well with Calvinist and Lutheran churches, two other “recognized” religions, and, in 1808, with Judaism.100 In addition to monitoring closely these established religions the Napoleonic criminal code enacted in 1810 prohibited the meeting of any unauthorized religious groups on the basis of Articles 291–294.101 As was the case during the revolutionary era, the Napoleonic regime combined official endorsement of religious liberty with policies that constrained religious practice, a tension that would continue to generate conflicts over the meaning and application of this new and ambiguous human right.

When the Catholic Bourbons were restored to France following the defeat of Napoleon’s armies in 1814 they faced the challenge of renewing the connections between throne and altar of the Old Regime, while making concessions to the religious freedom that had been endorsed and at times practiced during the previous twenty-five years.102 The Charter of 1814 defined what Pierre Rosanvallon termed an “impossible monarchy,” a phrase that nicely captures the paradoxical status of religion in the regime, for while Article 5 affirms religious liberty (“everyone professes his religion with an equal liberty, and obtains for his cult the same protection”), Article 6 establishes Catholicism as the official religion of the state (“however the Catholic, Apostolic and Roman religion is the religion of the State”).103 This tension provoked anxiety and resistance from both Catholic conservatives, who embraced an ideal of religious uniformity as the only possible basis for social order, and liberals, who feared that a state religion would necessarily compromise religious liberty. In official teaching and political theory, Catholic insistence on church authority as an appropriate limit to freedom of conscience and freedom of practice continued to exert influence throughout the Restoration, and beyond. Conservative theorists could look back to Pius VI’s papal brief of 1791, Quod aliquantum, as a foundation for their position. Condemning both the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and the Declaration of the Rights of Man, Pius asserted that the “license to think, say, write and even print with impunity anything that the most dissolute imagination might suggest” was a “monstrous right,” a form of madness.104 Louis de Bonald, one of the principal advocates of a Catholic restoration, both before and after the return of the Bourbons, condemned the principle of tolérance as a mask for religious indifference and a program aimed at the destruction of all religion.105 Speaking in the Chamber of Deputies in 1815, Bonald called on representatives to replace “the rights of man” with the “rights of God.”106 As we will see in chapter 5, Félicité Lamennais during the Restoration won praise from conservative Catholics for his impassioned assault on the religious liberty established by the French charter, before reversing himself in a move that shocked contemporaries. In practice as well as theory religious liberty seemed at times threatened by the government of the Restoration. Although Catholic conservatives were disappointed with the regime, a series of laws passed in the first two years of the Restoration showed the influence of the clerical party. Divorce was abolished, church control over education was enhanced, work was banned on Sundays and religious holidays, and in 1825 the notorious “Sacrilege Law” made it a capital crime to desecrate a consecrated host.107 On an individual level those who refused to decorate their churches in honor of the Fête-Dieu or to take off their hats to honor the Eucharist in processions could be prosecuted, leading to court cases that drew national attention to the issue.108 Collectively the state at times cracked down on religious groups that fell outside the “recognized” cults of Catholicism, Calvinism, Lutheranism, and Judaism, using the penal code against evangelical preachers from England and mystic missionaries such as Mme de Krüdener, who was active in Alsace from 1808 to 1817.109 On other occasions officials were content to keep track of illegal religious meetings, such as those organized by Quakers, and not provoke a scene by intervening, thereby helping the sect in its recruitment.110 But the principle of careful state observation and regulation of religion was never questioned; it was applied throughout the period, lasting until the separation of church and state in 1905, and still echoes in the present.111

This restriction of freedom in the religious marketplace was a particular target of Benjamin Constant, who played a central role in both the theoretical and political debates over religious liberty throughout the Restoration (1814–1830). Like other major theoreticians of religious liberty, Constant drew on personal experience as well as philosophical reflection in developing his ideas. Over the course of his early years Constant moved from a deeply skeptical attitude to one respectful of religious sentiment, mediated by a period of engagement with a mystical circle in 1807.112 Constant’s views, first developed while in exile from the Napoleonic empire, combined a hostility toward Catholicism, a religion that could not be reconciled with liberty, with an appreciation of Protestantism as derived from individual religious experience. In chapter 17 of Principles of Politics (1815) Constant ridicules the attempt by Rousseau to reconcile religious liberty with a coercive civil religion. Such “civil intolerance” was a pretext for tyranny, and an absurd contradiction in a philosopher who presented himself as a defender of freedom. For Constant, “the only reasonable idea regarding religion” was the “freedom of cults without restriction, without privilege, without obliging individuals, as long as they obey the law, to declare their attachment to any particular cult.”113 Responding to the fear that such freedom without limits would produce a constantly expanding number of sects, Constant accepted the premise that such a situation would emerge and embraced it as a positive development. Competition between sects would create a virtuous circle, with each new addition pushing the others to moral improvement. Underlying such a dynamic was the principle of freedom of inquiry (libre examen), the right of an individual to choose without regard to any external authority.114

Constant is best known for the striking contrast he drew between ancient and modern liberty in the speech he made at the Athénée Royale in 1819, where he painted a picture of the ancient Greek city-states as governed by an active citizenry capable of making public decisions but severely constrained in their private lives.115 In the ancient world liberty was thus an attribute of the collectivity, whereas in the modern world it was claimed as an individual right. In his speech at the Athénée Constant focused in particular on the political and commercial dimensions of liberty, but his reflections in Principles of Politics establish the same contrast between ancient and modern, collective and individual liberty in the religious sphere.

Constant was a prominent defender of religious liberty throughout the Restoration, defending the principle both in his writings and in the National Assembly.116 He was not alone, of course, with fears of excessive state control of religion and a return to Catholic predominance finding expression in the popular press. Charles X in particular became an object of caricature, presented as a tool of the Catholic clergy, crushing all other religions.117 On an intellectual level Constant found important support in the Society for Christian Morals, a group organized in 1821 that brought together Protestants and liberal Catholics to promote Christian morality, a task they would pursue without engaging in dogmatic or theological disputes. The society took a special interest in the subject of religious liberty, which was the topic of two essay competitions it sponsored in 1825 and 1827. In the first, which drew more responses than the second, authors were asked “to determine with precision the meaning of the words liberty of cults.”118 The prize committee was unanimous in choosing as the winner Alexandre Vinet’s essay, which was published the following year.119 The enthusiasm for Vinet’s work was based on the remarkable clarity with which it defined and linked the terminology on religious liberty that had evolved since the sixteenth century. Vinet identified two aspects of “freedom of conscience,” one involving the capacity for each individual to make moral judgments and the other to choose what kind of relationship, if any, to have with divinity. The social nature of mankind, however, meant that this last sense of conscience would flow naturally into a particular form, a “cult.” These two freedoms were thus distinct, one adhering in individuals and the other in communities, but they were also organically related and taken together constituted “religious liberty.” “I believe myself authorized to state that freedom of conscience and freedom of cults are one thing, which I call religious liberty.”120

Figure 3. Ngram of terms referring to religious liberty, 1801–1850. Search conducted on Google Books in June 2016.