Lamennais, Catholicism, and Freedom of Conscience

In the fall of 1835 George Sand set off for Brittany, where she hoped to spend time with the abbé Félicité Lamennais at his retreat in La Chênaie. Sand was in the midst of a personal crisis that involved her marital situation, but also her political commitments and her religious beliefs.1 What did Sand expect to find at La Chênaie? Nothing less than a prophet whose privileged communications with heaven would allow him to resolve the political and the personal anxieties that she confronted. In the end, Sand turned back while on the road, fearing that she was not ready for a visit that she saw as a sacramental occasion. But in a letter to Lamennais from December 1835 she begged him to take on the role of spiritual adviser, to “extend the protective and blessing hand of the one who, living amongst us, has the gift to rebaptize in the name of Christ, and to restore faith to those who have lost it.”2

Sand was not the only person in France who looked to Lamennais for guidance in troubled times. He had achieved celebrity status for the first time in 1817 with his Essay on Indifference (Essai sur l’indifférence en matière de religion), an attack on the principles of 1789 and a critique of religious tolerance. The essay met with an enormous and unexpected response from the reading public, selling forty thousand copies and making Lamennais a principal figure in the Catholic revival of the Bourbon Restoration.3 The publication of Lamennais’s The Words of a Believer (Les paroles d’un croyant) in 1834 provoked an even greater response, with tens of thousands of copies printed and translations appearing in all the major languages. But by 1834 Lamennais was no longer a stalwart defender of the pope and the Roman Catholic Church and instead promoted a Christianity that condemned monarchy, institutional religion, and economic exploitation and called for social justice and democracy.4 After Words of a Believer was explicitly condemned by Pope Gregory XVI in the encyclical Singulari nos (1834), most of Lamennais’s disciples deserted him; by 1835 he had abandoned the priesthood and was in the final stage of his separation from the Catholic Church.

The story of Lamennais’s disenchantment with Catholicism is in an obvious way different from the conversions of the Ratisbonne brothers and Ivan Gagarin, who moved into and not away from the Catholic Church. But looking at the series of religious choices Lamennais made in his adult life allows us to explore more fully the ideological stakes involved in crossing religious boundaries. Lamennais is an important figure in the history of religious liberty, known for both defending and then condemning the close alliance of church and state. His religious choices involved personal decisions about belief and belonging, but also political commitments designed to solve the political and social problems raised by the French Revolution. The boundaries between religion and politics were not clearly perceived by Lamennais, who was confused and troubled as he moved into and away from Catholicism. Focusing on the moments when Lamennais made his religious decisions allows us to see the complicated interplay between religious liberty, understood in both its individual and collective senses, and the claims for expanded political rights and social justice that defined much of French public life in this period. Historians are familiar with the powerful role that religion played in French politics, but how was this shifting relationship experienced by someone who identified with Catholicism and came to believe that the church might be failing to live up to its own principles? Lamennais’s transformation has fascinated both contemporaries and scholars, who have seen in him a figure who embodies the religious, political, and social tensions that divided France during the Restoration and July Monarchy.5 Lamennais’s final conversion marked a decision to break once and for all with the conservative politics of the church, but it also shows him moving, hesitantly and anxiously, toward an acceptance of the rights of individual conscience that he had formerly condemned.

Lamennais has left a rich body of evidence, both published works and private correspondence, that allows us to follow him along the circuitous path he took into and away from the Catholic Church. Political judgments played a central role in Lamennais’s decisions, but these were inextricably bound up with spiritual concerns and personal relationships. In addition to polemical works on church-state relations, Lamennais translated and provided commentary for the most popular edition in the nineteenth century of the classic text in spirituality, The Imitation of Christ. From the intensely personal religion of the Imitation, grounded in direct relationship with Christ, Lamennais could find inspiration and consolation that informed both his entry into and his departure from the Catholic Church. Finally, as he grappled with his political and spiritual dilemmas Lamennais was surrounded by a circle of family and friends, people on whom he depended, many of whom, like Charles de Montalembert, regarded him as a prophet uniquely gifted to explain the tragic events that had begun with the French Revolution of 1789. Breaking with the church meant breaking as well with people who respected and even revered him, a difficult decision that reveals again the personal costs that were paid by those who chose to exercise their religious liberty.

The Making of a Catholic Apologist

In 1816 Lamennais made an agonizing decision to become a Catholic priest, following a period of almost ten years in which he struggled with himself, and with his close friends and his brother, about a vocation that both attracted and repelled him. Over the next ten years Lamennais became the most prominent spokesman for the Catholic Restoration in France, known for his vigorous defense of Catholicism as the only possible source of political legitimacy and social order in the chaos that followed the revolutionary era. The early life of Lamennais thus involved two momentous decisions, first to embrace Catholicism as a religion and a social force of inestimable value, and then to devote his life to defending it as a Catholic priest. Lamennais’s final decision to leave Catholicism clearly was an act of religious liberty, but so were the decisions he made earlier in his life to join the church, which paradoxically involved a surrender of his freedom of conscience.

Félicité-Robert de Lamennais was born in Saint Malo in 1782, the son of a prosperous merchant and shipbuilder who was ennobled in 1788. We know very little of his early years, but as for so many others of this generation, Lamennais’s education was affected by the disruptions of the revolution. After his mother’s death in 1787 Félicité and his brother, Jean-Marie, were raised by their uncle Robert des Saudrais, who gave his nephews free rein to browse in his extensive library. Féli, as he was commonly called by his family and friends, was largely self-educated, teaching himself Greek and reading widely and indiscriminately.6 Jean-Marie decided early on a vocation and was ordained a priest in 1804. For the next thirty years the two brothers would have a close relationship, damaged severely but not completely broken by Féli’s departure from the church in the 1830s. Féli, more brilliant and volatile than his brother, struggled over his future and flirted for some time with the philosophical ideas of Rousseau.7 Finally, in 1804, at the age of twenty-two he received his First Communion and from that point pursued his career as a writer preoccupied with the religious and political questions that divided France throughout his lifetime.

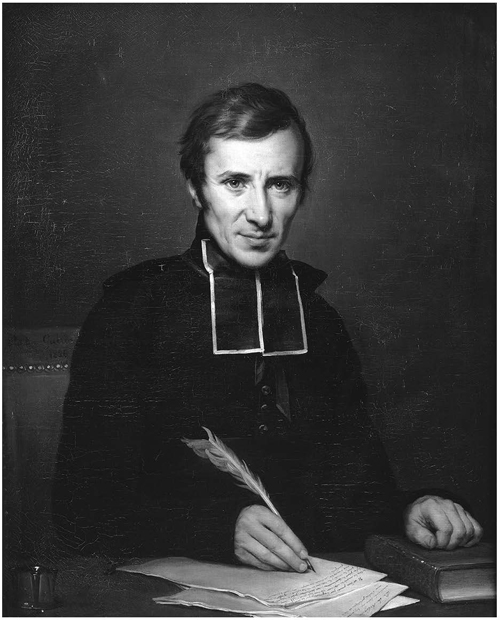

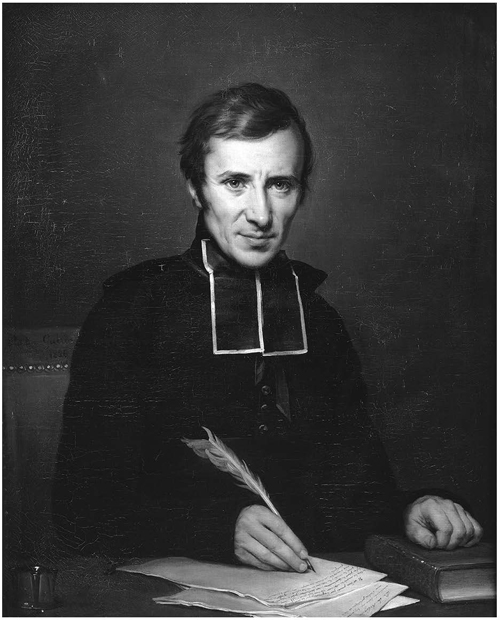

Figure 8. Portrait of Félicité de Lamennais by Paulin Guérin, 1826. Château de Versailles et de Trianon. © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY.

Lamennais’s early writings, based on a collaboration with his brother, were polemical interventions that established some of the principal ideas that he would develop throughout the next twenty years: the relationship between church and state should mirror that between soul and body, with the former having primacy over the latter, the spiritual over the material; religious authority rather than individual reason is the basis for certainty in both religion and politics; ultimate religious authority resides in the pope; and accepting Gallicanism, which advocated an independent French church, would prevent the universal church from fulfilling its regenerative role in post-revolutionary Europe.8

Lamennais’s intellectual commitments in his early career, vigorous and dogmatic as they were, did not prevent tortured reflections about his personal future. In letters exchanged with his brother and with his friend the abbé Simon Bruté from 1809 through 1816 Féli relentlessly criticized himself for pride and indecisiveness, a form of self-loathing that led him to wish for a life of prayer and solitude as the only way to find inner peace. The spiritual conflict of Lamennais throughout this period revolved around his doubts about ordination to the priesthood, a state in life that simultaneously attracted and repelled him. The first step toward ordination was taken in 1809, when Féli was tonsured, followed by his acceptance into minor orders in December. This initial decision was accompanied by bouts of self-recrimination, but also by periods of spiritual consolation, a pattern repeated over the next seven years as Féli struggled over whether or not to complete his journey. His letter to Bruté in February 1809 expresses his anxieties about his suitability for the priesthood, and how he resolved them. “When I reflect on my past life, full of crises that the most rigorous austerity and the most severe penances would not be able to expiate, and then consider my present state of half-heartedness, lack of conviction, the sensuality that exhausts me, this self-love that cannot be controlled, I am seized with a fear that is only too justified, and I wonder if such an unhappy creature should enter the sanctuary, and if I would be better off prostrating myself at the foot of the temple, like the sinner of the ancient law, less a sinner than myself. One thought nevertheless reassures me a little: I obey the advice of those I must respect, and this is for me a source of hope that a good and merciful God will grant me the help I need.”9 Lamennais’s sense of worthlessness needs to be understood in part as reflecting an Augustinian tradition of spiritual writing in which mankind is viewed as thoroughly corrupted by original sin.10 But recognizing this tradition should not diminish our sense of Lamennais’s view of himself as weak and selfish, a constant theme in his letters. Despite his hesitancy Lamennais was received as a subdeacon in December 1815 at Saint-Sulpice in Paris and was ordained at Vannes in 1816.11 How, then, did Féli manage to overcome his self-loathing and finally accept a priestly career?

Throughout the period between his tonsure and his ordination Lamennais explored in his letters a complicated psychological condition in which his will was divided between a desire to remain a layman, unworthy as he was of the priesthood, and the obligation to serve the cause of the church and of Christ by accepting ordination. In the face of agonizing self-doubt Lamennais relied on two sources of external authority to direct him: on his friends and family first of all, as suggested briefly in his letter to Bruté, but also on the figure of Christ, whose example of self-sacrifice he constantly referred to as he chose a path contrary to his own inclinations. There is a profound paradox embedded in Lamennais’s final decision in favor of the priesthood, for the apparent surrender of his own judgment about his future was at the same time a forceful assertion of an individual will, an act that could be characterized as both denying and affirming his religious freedom.

Throughout the years of indecision Féli was encouraged by his brother, Jean-Marie, and his friend Bruté to take up the cross of his vocation, an argument that they reinforced by invoking the will of God and the saints. When Féli expressed doubts prior to his tonsure in 1809 Bruté wrote that he prayed that the Holy Spirit would enlighten him about God’s will and confessed to having a “a secret fear” that restrained him from adding his “worthless and crude ideas and words to the work, so pure as it is, of the Holy Spirit.” But this was a disingenuous claim, for Bruté immediately proceeded to insist that he and Féli’s brother were joined by Christ and a long list of saints in their conviction that he belonged in the church. “I must tell you in the presence of Our Lord Jesus, of his Holy Mother, of your good angel who will read this letter with you, and mine, who sees me write it, of our patrons and those of the seminary, the great St. Charles, St. Vincent, St. Francis de Sales, I must tell you, kissing yet again the feet of Christ, that I believe you must work for the Church, not only in prayer and solitude, but by study, advice, action, and communications of every kind in support of the active Church.”12 Féli resisted such pressure for several years but never fully abandoned the ultimate goal of ordination; for a time he considered becoming a Trappist monk in Kentucky as a way of fulfilling his vocation but avoiding the role of public activist that Bruté saw as his future.13

Lamennais made the final decision to become a priest under unusual circumstances in 1815. Having fled to London during the hundred days of Napoleon, Féli came under the influence of the abbé Guy Carron, an émigré priest who had established a boarding school for girls there in 1792.14 Writing to his brother, Féli described a situation in which he was isolated from his family and friends, and totally dependent on his new spiritual adviser. Still internally conflicted, he was nonetheless determined to obey the commands of Carron.

[Providence] tears me from my fatherland, my family, my friends, and from this specter of repose that I pursued to the point of exhaustion, and leads me to the feet of his minister so I might confess my confusion and submit to his will. Glory to God, to his ineffable tenderness, to his incomprehensible goodness, to his adorable love that, among all his creatures, has chosen the most worthless of them in order to make him a minister of his Church. . . . But shame, confusion, profound humiliation to the miserable creature who fled for so long his divine Master, and with horrible obstinacy refused the goodness to serve him. Alas, even in this very moment I feel only too much that if my entire will were not in the hands of my beloved father, if his counsel did not sustain me, if I were not completely resolved to obey without hesitancy his salutary orders, I would fall back into my uncertainty and the bottomless pit from which his charitable hand withdrew me.15

Féli’s friends were delighted with his decision, even while they acknowledged the pain it caused him. Lamennais himself repeatedly compared his decision to accept ordination to Christ’s sacrifice of himself on the cross. In a letter written to Bruté just after receiving his tonsure he breaks into a prayer that expresses his attachment to Christ and his rejection of the world, two principles that at this point in life he accepted without question, even as he found it difficult to embrace them in practice. “Oh what life, what sweetness, what a happy life! My heart delights in being crucified with Jesus through the suffering, contradictions, scorn, ingratitude, hatred, outrage, persecution, and everything that could most crucify my pride and my flesh.”16

Inspired by both his friends and his attachment to Jesus, Lamennais managed eventually to overcome his doubts, though it is hard to avoid a sense that for him ordination was as much an act coerced by spiritual pressure as it was a decision reached on the basis of his own discernment. There is a conspiratorial tone and an almost ghoulish delight in the letter that the abbé Carron wrote to Bruté as Lamennais approached his final decision to become a priest: “He won’t escape me; the church will have what belongs to it.”17

In the period that followed his ordination Lamennais did not forget the spiritual crisis through which he passed on his way to the priesthood. His personal struggle with authority surfaces, covered by only the thinnest of veils, in the work that established him as major figure in French intellectual life. When the first volume of the Essay on Indifference appeared in 1817, just one year after Lamennais’s ordination, it created an enormous and unexpected sensation with the reading public. The book sold forty thousand copies and overnight made Lamennais into one of the principal figures in the Catholic revival of the Bourbon Restoration, along with Bonald, Maistre, and Chateaubriand. This was a book that, according to Monsignor Frayssinous, preacher to Louis XVIII and subsequently the grand master of the university, “would wake up a dead man.”18

The Essay on Indifference appealed to readers because of its rhetorical flair and its unequivocal condemnation of freedom and equality, the principles of 1789 that led to the catastrophes of the revolutionary era and the contemporary crisis. Only a rejection of religious indifference, and of the soft-headed tolerance of individual judgment, could restore the social order. In hammering this point in, Lamennais describes the social necessity for unquestioning submission to religious authority with language that recalls his personal crisis and final acceptance of the priesthood. The passion and power in Lamennais’s writing derives not only from his political and religious commitments but from their connection to his own struggle with authority, which continued even after his submission. “[Religion] cannot leave man free to believe and act according to his will; it constrains him to submit his reason to his faith, his desires to his duties, his body to the practices that it imposes. Now, in subjecting in this way the whole man, religion exhausts him, and drives his passions to despair. Never vanquished even when they obey, they work tirelessly to break the yoke that they bear, always murmuring against it. Pride, the father of lies, and eternal enemy of authority, suggests to the mind a crowd of sophistries.”19 To judge by this passage, even after his ordination Lamennais was not fully submissive and was engaged in a constant battle to master his pride and reject his individual impulses.

This same conflict shows up as well in his translation of The Imitation of Christ, accompanied by an extensive commentary, which appeared in 1824.20 In the history of spirituality the Imitation was a central text in the late medieval movement of renewal known as the devotio moderna. The Imitation emphasizes the importance of inner reflection on the life of Christ, and the constant struggle involved in battling with the self in pursuit of Christian perfection.21 In chapter 9 it calls for obedience and the renunciation of one’s own inclinations, a topic that led Lamennais to one of his most extended comments, which he concluded with an unqualified endorsement of external authority: “No order in the world, no life without obedience: it is the bond between men, and between men and God, the foundation of peace and the principle of universal harmony. . . . In obeying the Pope, the Prince, the father, anyone who is the minister of God for the good (Romans XIII, 1), it is God whom one obeys.” From Lamennais’s perspective, only in such apparent self-abnegation does one really become free, for “delivered from the slavery of error and passion, from the slavery of man, he enjoys the true liberty of the children of God (Romans VIII: 21).”22 Ten years after the publication of The Imitation of Christ, Montalembert would refer precisely to this passage in urging his friend and mentor to submit to the church, surrender his personal judgment, and obey the pope in acknowledging his errors. As we shall see, Lamennais refused this appeal, for he had by then come to a very different understanding of religious liberty.

Lamennais pushed very far in imagining how far the state, informed by Catholicism, could extend its reach into the lives of its citizens. At one point in the Essay on Indifference he insists that “private actions, habits, must also be regulated by laws that, penetrating to the heart of man, establish order in his thoughts and feelings; because feelings and thoughts are the principle and motive of all human actions.”23 Although Lamennais never overtly attacked the freedom of conscience as such, this passage suggests how deeply he resisted individual religious liberty, a principle he had rejected in his own life only after a long and painful struggle, and that he saw as endangering the salvation of souls and the social order.

The Making of a Catholic Renegade

Almost twenty years after the initial crisis leading to his ordination Lamennais faced another wrenching decision as he moved away from the church that he had defended so passionately for two decades. Lamennais’s religious choices continued to be inextricably tied to the political and religious context, but the situation in 1830 looked very different from that of the Napoleonic empire and Bourbon Restoration. From the perspective of both Napoleon and the Bourbons, the political and social order that dissolved during the Revolution of 1789 required the close cooperation of church and state, reflected in the concordat negotiated by Napoleon in 1801 and honored by the Bourbons after they returned to France in 1814. In the immediate aftermath of the revolution of 1830 the July Monarchy at first seemed willing to break from the alliance of throne and altar.24 As we saw in chapter 1, under the revised charter Catholicism lost its position as the official state religion, a policy that was accompanied by a great deal of popular hostility directed at the church. In Paris the archepiscopal palace was sacked by rioters during the “three glorious days” of July that brought down the Bourbons in 1830. Archbishop Quélen was forced into hiding, and for months priests were afraid to wear their Roman collars in public. Religious rioting was renewed on February 14, 1831, when the palace was sacked again, along with the church of Saint-Germain l’Auxerrois following a ceremony commemorating the death of the duc de Berry, the Bourbon prince who had been murdered in 1820. The government reacted slowly to these assaults, leading to recriminations that it was unwilling to defend the persons and property of the church.25

How might the Catholic Church understand and respond to such popular hostility? For Lamennais and his colleagues, the anticlerical violence that swept through Paris in 1830–1831 was the price being paid by the church for its bargain with the Bourbon monarchy, a choice that put it on the wrong side of history and compromised Christ’s message of equality, charity, and justice. In order to win back the people, the church would need to take up its call for liberty and abandon its traditional alliance with kings. This fundamental agenda of “God and Liberty” was proudly declared on the masthead of L’Avenir, the paper guided by Lamennais in the aftermath of the July Revolution, which attracted international attention because of the notoriety of its leader and the revolutionary nature of its appeal. From October 1830 to November 1831 L’Avenir served as a call to arms for reform-minded Catholics, and a frightening threat for conservatives desperate to maintain the social order. For Lamennais and his associates, the revolutionary movement that spread from Paris in the summer of 1830 revealed the inexorable movement of history, a providentially determined process that would overturn thrones in favor of democratic regimes. The Catholic Church had a special responsibility at this moment, to abandon its ties to decadent and oppressive power structures and to associate itself with the cause of liberty. But beyond the slogan “God and Liberty,” and the broad proposal of an alliance between Catholicism and liberal movements, what did liberty mean for Lamennais, and how was freedom in general related to the right of religious liberty? And finally, how can we explain Lamennais’s personal transformation, and what might it suggest about the experience of religious liberty in the age of revolution?

The freedom at the center of the program of L’Avenir was first of all the collective right of the church to operate without any constraint from the state.26 In the first article that appeared in the paper, Lamennais insisted on the freedom of the church as an institution, which he linked to the issues of freedom of education and the press. Religious liberty meant the separation of church and state, which in turn implied that Catholics should be allowed to open schools unsupervised by the monopoly of the state university, and to publish freely.27 Freedom of education and the press were the most important domestic issues for both the journal and the Agence générale pour la défense de la liberté religieuse, an organization formed under the same leadership as L’Avenir and dedicated to defend religious liberty in the political sphere and the courts.28 All of these freedoms defended by Lamennais and his colleagues went well beyond what the July Monarchy was willing to accept, for while the revised charter demoted the Catholic Church, it retained the concordat, the university, and the right of censorship. The state still exercised enormous control over the church through its power of appointment and control of the purse strings; it continued to enforce its monopoly over secondary and higher education; and it monitored and at times suppressed public criticism of its policies.

Freedom was more than an abstract cause for Lamennais and L’Avenir. Within two months of its first issue copies of the paper were seized for inciting hatred against the government. The articles in question challenged the right of the government to nominate bishops and condemned state officials for failing to defend churches from violent assaults. In January 1831 Lamennais was put on trial, along with Henri Lacordaire (1802–1861), a young Catholic priest who had become a principal collaborator on and one of the most frequent contributors to the journal.29 The trial was a dramatic event that drew a packed courtroom in the Palais de Justice in the heart of Paris, where the prosecutor M. Berville and Lamennais’s lawyer Eugène Janvier battled with each other over the issue of church-state relations, with frequent interruptions by the crowd. Late in the evening Lacordaire made an impassioned speech in which he described his own religious conversion from a skeptical lycéen to a Catholic priest, and then to his attachment to Lamennais and his ideas. An exhausted Lamennais was unable to speak on his own behalf, a condition that Janvier described as due to his genius, and he warned the jury as it departed “to take care that posterity not hold them to account for an unforgivable result.”30 Finally, at midnight, the jury rendered its verdict, with Lamennais acquitted and Lacordaire given a slap-on-the-wrist fine. Lamennais judged the result “a triumph for the Catholic cause.”31

The issue of freedom of education also produced a dramatic court case, when Lacordaire and Charles de Montalembert (1810–1861) opened a school on the rue des Beaux-Arts without the authorization of the university. This initiative was clearly intended to provoke the authorities, who shut down the school after just a few days and prosecuted its directors. This proved a more complicated matter than the state had anticipated, for soon after the school was closed in May 1831 the Count de Montalembert died, passing to his son Charles his title and his seat in the House of Peers. This meant that Charles de Montalembert could be tried only by his colleagues in the upper house of the French legislature. A young man, totally committed to the liberal Catholic agenda, Montalembert was devoted to Lamennais, who was his confessor as well as his political mentor. His speech in the Senate on September 19 in defense of freedom of education was a tour de force of romantic rhetoric in which he presented himself as a devout and humble young man, awed by the assembly but also driven by a fervent attachment to his Catholic faith and the freedom promised by the charter and now denied by the government.32 As with the prosecution of L’Avenir, a guilty verdict was accompanied by a modest fine, and Montalembert took his place alongside Lacordaire as a prominent public figure in the campaign for religious liberty. Through these moral victories Lamennais, Lacordaire, and Montalembert became major figures on the political stage in France as a powerful triumvirate, a mature sage supported by two impassioned young men, fighting to create a new world based on the shocking and exhilarating idea of marrying Catholicism to liberalism.33

Although this program was eventually and perhaps inevitably condemned by the institutional church, it is worth recalling that Lamennais and L’Avenir were frequently on the same side as the generally conservative episcopacy. In the aftermath of the Parisian attack on Saint-Germain l’Auxerrois, Lamennais’s paper condemned the government for its failure to defend the church, and in general for allowing “their faith, their prayers, their priests to be subjected to an inquisition by mayors and prefects, their crosses destroyed, their feast days regulated by ministerial circulars, their children brutalized by the university, their bishops named by deists, or by even more determined enemies.”34 L’Avenir was particularly outspoken in defending the authority of bishops over the administration of sacraments, most dramatically in the case of the abbé Grégoire in 1831. Grégoire had been the most prominent defender of the Constitutional Church created in the early days of the French Revolution, and unlike many of its proponents had never reconciled with Rome following the concordat. As he approached death Grégoire was living in the commune of Abbaye-aux-Bois in the diocese of Paris, under the jurisdiction of Archbishop Quélen. Despite Quélen’s prohibition Grégoire was able to find a priest who administered to him the Last Sacraments. A furious Quélen then tried to prevent a Catholic funeral service, but under the personal direction of Prime Minister Casimir Périer the church at Abbaye-aux-Bois was forcibly entered, and a Mass was said over Grégoire’s body by sympathetic clergy. L’Avenir responded to this series of events with an article condemning the state’s behavior as sacrilegious and using the scandal as another opportunity to defend the liberty of the church.35 Lamennais was eventually embittered by what he considered unfair treatment by the church hierarchy, and he was certainly naïve in his hope that the pope and the bishops would support his liberal agenda. Nonetheless, his sense of religious liberty did lead him to defend the rights of the church in terms that even his most vociferous opponents could appreciate, suggesting some common ground, though not covering the amount of territory envisaged by Lamennais.

Despite L’Avenir’s support for episcopal prerogatives, and for freedom of Catholic education, Quélen and the vast majority of the episcopacy were deeply suspicious of Lamennais and his colleagues. As Lamennais made clear in his paper, the separation of church and state would, after all, mean the abolition of the ecclesiastical budget, the end of all state financial support for the church.36 How would the clergy survive, how would churches be maintained in such a world? Would ordinary Catholics be able to provide the support needed? And weren’t clerical salaries a necessary and just compensation for the state seizure of church property during the revolution? Beyond such institutional concerns, the bishops also feared the revolutionary rhetoric of Lamennais. While he foresaw a Catholic and democratic revival, the bishops feared a return of the violence and dechristianization of the 1790s. These hopes and fears were based not only on memories of the great revolution just one generation past but on the new revolutionary wave that struck in 1830.

Catholic Freedom and Political Liberty, 1830–1833

France was not alone in facing revolutionary change in 1830. As the editors of L’Avenir looked around Europe and beyond they found several examples that proved to them that the marriage of Catholicism and liberty was already at work, generating religious fervor and mobilizing democratic movements. The signs of the time were clear: Europe had reached a providentially determined turning point that was troubled and even violent but would soon produce a revived religious and political order inspired by the Catholic principles advocated by the prophet Lamennais and developed in L’Avenir. Four years before Tocqueville analyzed the separation of church and state in Democracy in America Lacordaire praised the Catholic Church in the United States as an “unprecedented marvel,” able to flourish precisely because it was independent of all state control.37 Ireland and Belgium were other examples trumpeted by L’Avenir as examples of the successful union of Catholicism and liberalism. In the 1820s the Catholic clergy and the layman Daniel O’Connell mobilized the Irish population and succeeded in forcing the British government to grant Irish Catholics political and civil rights in 1829. To the north of France French-speaking Catholics resented the rule of William I, the Protestant king of the United Netherlands. Their rebellion that began in Brussels in August 1830 led eventually to an independent Belgium in which freedom of education was guaranteed.38 But the most dramatic and ultimately tragic example of the alliance between Catholicism and liberty was the Polish rebellion that began in November 1830. From the perspective of L’Avenir this uprising was a battle of Polish Roman Catholics against a Russian Orthodox tyrant, demonstrating the perfect congruence between the causes of political and religious liberty.

Montalembert took the lead in praising the “holy revolution of the Polish,” which succeeded at first in driving the Russian troops out of Warsaw. Freed from the “barbarous schismatic despot,” Poland would soon become a “new Catholic republic” and along with Ireland and Belgium presented a sign that “Europe will recover its political and religious balance.”39 By early 1831, however, as Russian troops advanced on Warsaw, the fate of Catholic Poland was being redefined in the pages of L’Avenir. Lacordaire adopted an apocalyptic tone as he foresaw the defeat of the Catholic revolution, which he linked to the continuing threats directed against Belgium: “Catholics! Your hour has come. You will show yourselves unshakable in your love for the faith of your fathers and for the liberty of which Belgium and Poland have made you the first-born of the nineteenth century. When the swarms of barbarians throw into the grave the civilization which you created a thousand years ago, be not afraid, and trust in your immortality. Know that great suffering is required for great accomplishments. Perhaps Europe will be crushed anew, but this will be done so that it might be brought together in a new combination, as has been written by a man of genius.”40 The genius Lacordaire referred to was Adam Mickiewicz, the Polish poet whose combination of Catholic zeal and nationalism brought him the admiration, not to say adulation, of Lamennais, Lacordaire, and Montalembert. I will come back to the Polish cause later, as it played a major role in the next stage of Lamennais’s religious crisis, when Pope Gregory XVI condemned the rebellion and called on Polish Catholics to accept the rule of Tsar Nicholas I. But in 1831 Lamennais and his circle still believed that the Catholic Church was the natural ally of Polish nationalism.

The freedom of the Catholic Church to teach and publish apart from state interference and the freedom of Catholic people to govern themselves, these were the issues that defined religious liberty for Lamennais and L’Avenir.41 Freedom of conscience, understood as the right of an individual to choose a religion, never came into clear focus throughout the lifetime of the paper. Lamennais employs the term loosely, without clearly distinguishing freedom of conscience from freedom of religion in his programmatic article on the “Doctrines of L’Avenir” from December 1831: “In order that there be no confusion over our thought, we ask first of all for the freedom of conscience or the freedom of religion, complete, universal, without distinction or privilege; and consequently, in what concerns us as Catholics, the total separation of Church and State.”42 Only one article takes up explicitly the topic of liberté de conscience, a piece by the abbé Gerbet, another of Lamennais’s intellectual soul mates, who operates on a much more abstract plane than is typical of the journal. Gerbet attempts to illuminate the admittedly obscure nature of this doctrine by distinguishing sharply between “indifference” and “toleration.” Moving very far from Lamennais’s position in 1817, Gerbet insists that “civil tolerance in no way implies religious indifference, or the negation of obligatory moral beliefs.” But the “interior obligation to profess the true religion” can be enforced only by the moral sanctions of the church, and not at all by the state, “because it is Catholic doctrine that civil penalties should never emanate from spiritual authority. To deny this would be to deny radically the very distinction of the two powers, consistently maintained in the traditions of the Church.” Beyond this philosophical position, Gerbet sketches a historical evolution in which the medieval church called on the state to enforce moral law because of the immaturity of the European people, “a regime which must cease when they have arrived at the age of maturity, that is to say, when they have become capable of doing for themselves what previously could only be done by the fathers of the great family.” Gerbet’s analysis, though implicitly based on the rights of individual conscience to be protected from state interference, nonetheless continues to focus on the relationship between church and state and, like the work of his colleagues, never engages with the issue of personal religious choice. Lamennais summed up this political preoccupation in an essay on “religious liberty” published late in the summer of 1831, as he looked back on the momentous events in Europe over the past year. The mobilization of Catholics in Ireland, Belgium, and Poland showed Lamennais that “political liberty is inseparably tied to and can only be affirmed and developed through religious liberty.”43 The phrasing here is significant, for it suggests that religious liberty, while a principle concern, is nonetheless instrumental, aimed at achieving the ultimate goal of political liberty.

Lamennais never abandoned his passion for politics, and he remained convinced that religious liberty required the separation of church and state. But between 1832 and 1836 he came to believe that religious liberty was threatened not only when the state interfered with the church but also when the church interfered with the individual conscience. This expanded view of religious liberty, however, came about precisely because of his battle with the Catholic Church over political questions. The rights of individual conscience became a prominent theme in his private correspondence, but they assumed greater importance as well in his public writings. Lamennais continued to insist on the need for political democracy and social justice, achieved through a religious and moral revolution that was first preached by Christ. But his personal and painful battle with the church led him to insist on the right of individual judgment, the principle he began his career by denying.

The story of Lamennais’s confrontation with the Catholic hierarchy has been told many times, in large part because of the personal drama involved in his prolonged effort to convince Pope Gregory XVI and his advisers to embrace the cause of liberty and popular sovereignty. Lamennais wrote his own bitter account of his break with the church in Affaires de Rome (1836), but we have as well the extensive correspondence he carried out throughout the period 1831–1836 with the pope and his advisers, and with his close friends and collaborators. These sources show how Lamennais’s final break with Catholicism did not occur all at once, nor on the basis of a single catalytic event. In his correspondence of the early 1830s Lamennais shifts back and forth, sometimes hopeful, sometimes despairing, as he sought approval from Rome and, when this was not forthcoming, pursued toleration rather than condemnation for his position. In some letters written during his several months in residence in the papal city Lamennais is deeply pessimistic, viewing the hierarchy as dominated by political interests, the same position he takes in Affaires. In February 1832 he wrote to Charles de Coux that “Russia is all-powerful at the Vatican, and its policies dominate all church affairs. It is the final stage of the degradation of the Church; and since it cannot continue to exist in this state of abject slavery, it is certain that we are bordering on an immense revolution whose result will be the liberation of Catholicism. It will be preceded by great evils and bloody catastrophes; after which will come a regenerating Pope [Pape régénérateur].”44 Austrian spies managed to intercept this letter, which was then passed on to the Vatican. This practice became common in the spring of 1832, part of a concerted effort by the Austrian chancellor Metternich to discredit Lamennais with the pope, who was apparently eager to read these private letters.45

Lamennais’s virulent critique of the Catholic hierarchy, even while he sought an audience with the pope and avowed himself a loyal subject, made him appear duplicitous and figured in the final decision to condemn his doctrines in the encyclical Mirari vos, of August 1832. But prior to the issuance of this decision Lamennais never entirely lost hope in his situation and at times believed that the pope would resist the pressure to condemn his doctrines, thus ensuring his ability to continue to work for “God and liberty” in a renewed version of L’Avenir. He was particularly upbeat following an audience with the pope on March 13, 1832. After the ritual genuflections and the kissing of Gregory’s feet the pope chatted amiably about common friends and family members, blessed some rosaries, and sent Lamennais and his friends on their way. Although the pope never came close to discussing substantive ideas and the status of Lamennais’s appeal, his friendly reception suggested that Rome would forgo an outright condemnation, leaving the editors of L’Avenir free to continue their work.46

Lamennais was thoroughly mistaken in this assessment of his case. Throughout the spring of 1832 a council of five experts convoked by Gregory XVI to formulate a response to Lamennais’s appeal for a papal judgment drafted memoranda that called for an outright condemnation of the doctrines of L’Avenir.47 In July 1832 thirteen French bishops, led by Monsignor D’Astros of Toulouse, submitted a blistering attack that condemned the principle of separation of church and state and the freedoms defended by Lamennais and accused him of sowing divisions in the French church, where the young clergy were being seduced by a false prophet. Both the Roman experts and the French bishops targeted the political dangers of Lamennais’s agenda, but the French objections also focused on Lamennais’s “common sense” theology, his view that religious certainty was based first of all on the principle of universal consent.48 In their view, this doctrine denied that the Catholic Church provided exclusive access to essential religious truths and thus made Catholicism subservient to “common sense.”

Although Lamennais was not blind to the power of the opposition, when he departed Rome in July 1832 he was convinced that his mission had at least achieved a modest success. Writing to Charles de Coux, Lamennais asserted that “our mission here is finished. It has confirmed our orthodoxy and left us perfectly free to act as we think the best.”49 After stops at Florence and Venice Lamennais and Montalembert reached Munich in August, where they were later joined by Lacordaire and greeted warmly by an imposing circle of Catholic intellectuals that included Joseph Görres, Franz von Baader, and Ignaz von Döllinger. But it was at Munich that the blow fell, when the encyclical Mirari vos arrived, accompanied by a letter from Cardinal Pacca, the secretary of the Congregation of the Holy Inquisition. The encyclical itself never mentions Lamennais by name, and not all the positions condemned by Gregory were part of L’Avenir’s agenda. For example, Lamennais never criticized clerical celibacy nor advocated the marriage of priests, positions explicitly condemned in the encyclical. Nonetheless, the absolute rejection of the separation of church and state, the condemnation of freedom of the press, and the insistence that people obey their rulers clearly targeted Lamennais. Pacca’s letter removed any doubt in the minds of Lamennais and his followers that the pope had rejected their ideas and the program of L’Avenir.50

Lamennais’s immediate reaction was to submit, a decision that was published in several journals in September 1832, after his return to Paris. The language employed in the public announcement was unequivocal in its acceptance of papal authority: “The undersigned editors of L’Avenir . . . convinced according to the encyclical of August 15, 1832 of the Sovereign Pontiff Gregory XVI that they are unable to continue their work without placing themselves in opposition to the formal will of the one whom God has charged to govern his Church, believe it their duty as Catholics to declare that, respectfully submissive to the supreme authority of the Vicar of Jesus Christ, they abandon the field on which they have fought loyally for two years.”51 Based on his private correspondence in the months following the publication of Mirari vos, there is no reason to doubt the sincerity of Lamennais’s acceptance of the papal decision. In letters to his fellow editors Lamennais even seems relieved; liberated from an exhausting public controversy, he could now take up a quiet life of study in his beloved retreat at La Chênaie, in Brittany. This is not to say that Lamennais now rejected the principles he had avowed in L’Avenir nor abandoned his prophetic tone. Writing to the Comtesse de la Senfft, he insisted as before that kings and emperors were on their way out, that the transition to a new order would be painful, and that in the end “we will see Christ again, Christ the savior, Christ the liberator, Christ who takes pity on the poor, the weak, and who breaks the sword of their oppressors.”52 On other occasions Lamennais struggled to retain his faith in a better future. To Father Ventura (1792–1861), the superior general of the Theatines and one of Lamennais’s few supporters in Rome, he wrote that “the heavens are dark, the storm approaches . . . but perhaps God himself has placed his fingers over the eyes of some, so they would not see, and the ears of others, so they would not hear, in order that what must happen will happen. Time will tell.”53 All of these sentiments, however, were expressed only in private, as Lamennais continued to honor his promise to cease publishing ideas condemned by the pope.

At first Rome was pleased with Lamennais’s acquiescence; Cardinal Pacca informed him that his statement of September had satisfied the pope, that “this measure was the one that was expected of you.”54 But if Rome was satisfied, Metternich was not, and neither were the French bishops, who were convinced that Lamennais had in no way altered his opinions. Metternich’s agents continued to pass to Rome letters intercepted from the circle of Mennaisiens, including one from Montalembert, that showed them stubbornly holding to their views, even while they kept silent in public. The bishop of Toulouse insisted that Lamennais’s statement was not a retraction, and that his followers claimed that the encyclical was not binding on Catholics because it concerned matters not of faith and morals but of politics.55 Pressure from France prodded Gregory to write to the bishops of Toulouse and Rennes, expressing his disappointment that Lamennais had not gone further in his first statement and submitted wholly and without reservation to Mirari vos.56

Lamennais was furious that his initial submission, and its apparent acceptance by the pope, had ultimately proved insufficient in the face of a concerted effort by his enemies, who were interested only in an unconditional surrender. But for all his bitterness and frustration, he continued to seek some accommodation, which at one point involved lengthy and apparently friendly conversations with Monsignor Quélen, the archbishop of Paris. In the end, however, differences on the meaning of religious liberty, in both its political and personal dimensions, made it impossible for Lamennais to remain a Catholic priest, or even a Catholic. At first it was the Roman commitment to authoritarian regimes, and in particular the papal condemnation of the Polish rebellion, that pushed Lamennais to see that the Catholic Church could not fulfill the emancipatory role he saw as its providential mission. But this profound difference on a political question was accompanied by a second conflict that in the end separated Lamennais not only from the church but also from his own past, as he struggled and ultimately failed to reconcile his duty to obey with his emerging sense of the right of individual conscience.

The papal letter to the Polish bishops of June 9, 1832, is the first of the “pièces justificatives” that Lamennais included in Affaires de Rome, an indication of how important this issue was to him as he worked out his relationship with the church. In a long and crucial letter that he wrote to Father Ventura in January 1833, Lamennais reflected on the previous six months and acknowledged that as a result of his stay at Rome “my ideas have changed in many ways, have been modified on some points, and are not entirely fixed on others. From the time I saw Rome up close, it is no longer for me what it used to be, and I am not alone in this.” Clearly Lamennais was disgusted by the ways in which rumor and innuendo shaped decisions, and by the power wielded by men for whom religious matters were secondary to politics, and to their careers. But it was the Polish question that served as the focal point for his resentment, and as the starting point for his break from Rome. “The first thing that made me reflect profoundly was the letter to the Polish bishops, gone over and corrected by the Cardinal Gagarin, the delegate of His Holiness the Emperor Nicolas, who had just sent 25,000 Catholics to the Caucasus without a single priest, and suppressed 192 Polish convents, all of the seigneurial chapels, and all the seminaries, except one, in Wilna, whose rector is a known spy.” From this reflection Lamennais went on to conclude that the church was now governed by men who, “indifferent to all principles, have temporal interests as their only goal.”57

The attachment of Rome to an old regime of despots continued to trouble Lamennais throughout 1833, with Poland as the most dramatic example of Catholic complicity with tyranny. The arrival in Paris of hundreds of Polish refugees, and in particular of the poet Adam Mickiewicz, kept the Polish cause alive for Lamennais and his colleagues, horrified by stories of Nicholas’s repression following the Russian victory of October 1832. It was sympathy for Catholic Poland that led Lamennais to break his silence and publish a “Hymn to Poland” at the conclusion of Montalembert’s translation of Mickiewicz’s Book of Polish Pilgrims (Livre des pèlerins polonais), which first appeared in May 1833. Both Lamennais and Montalembert were moved by Mickiewicz’s biblical language, and his evocation of a Poland that would redeem the nations of the world through its sacrifice, just as Christ had redeemed individual men.58 In a lengthy preface Montalembert made no reference to the papal letter that had called on the Polish people to submit to Nicolas and instead described him as a cruel and illegitimate tyrant. Moreover, Montalembert drew a direct line from Poland to France, suggesting that the suffering of the Polish exiles mirrored the experience of those in France who had also been silenced and excluded, a clear reference to Lamennais and his followers, condemned in Mirari vos: “The dominant ideas of [The Book of Polish Pilgrims] have an application more general than might at first appear, and they can be adapted clearly to the position of France and Europe. . . . Perhaps there are more exiles than one might think in modern society; perhaps it includes many pilgrims who walk sadly towards a murky future; souls banished after hard battles, from their youthful enthusiasm, their old faith, their most honorable feelings, their most legitimate hopes, and who search with uncertainty an unknown refuge.”59 The publication of The Book of Polish Pilgrims was a principal item in Gregory’s October letter to the bishop of Rennes, in which he called on Lamennais “to follow uniquely and absolutely the doctrine exposed in our encyclical letter . . . and to desist from writing or approving anything that does not conform to this doctrine.”60 Gregory’s attempt to discipline Lamennais marks an important point in which the political argument leads inexorably to one about the extent of papal authority over an individual conscience. This was familiar territory to Lamennais, who had devoted himself to the ultramontane cause throughout his career, but in the extended crisis of the early 1830s he came, after much painful soul searching, to see that papal authority could be abused. This recognition led in turn to an assertion of his freedom of conscience, the individual dimension of religious liberty that had previously remained in the background of his life and thought.

Testing the Limits of Freedom of Conscience, 1832–1836

Individual religious liberty had not been a major concern for Lamennais and L’Avenir; it figured not at all, for example, in the “mémoire” that Lamennais, Lacordaire, and Montalembert submitted to the pope in defense of their position in February 1832.61 But Mirari vos attacked nonetheless “that absurd and erroneous proposition which claims that liberty of conscience must be maintained for everyone. It spreads ruin in sacred and civil affairs, though some repeat over and over again with the greatest impudence that some advantage accrues to religion from it. . . . Experience shows, even from earliest times, that cities renowned for wealth, dominion, and glory perished as a result of this single evil, namely immoderate freedom of opinion, license of free speech, and desire for novelty.”62 However one interprets the precise meaning of “freedom of conscience” in this text, it can be seen as a justification for the pressure the hierarchy brought to bear on Lamennais, pushing him to abjure his principles. For almost a year after the submission of September 1832 Lamennais avoided both public comment on religious questions and any further communication with Rome. But in August 1833 he wrote the first of his three letters to Gregory. Lamennais’s particular goal at this point was to save the schools of the Brothers of Christian Instruction, a congregation founded by his brother, Jean, which was threatened because of its association with a possible heretic. Lamennais concluded his letter with two declarations. First, he acknowledged that “because it belongs only to the Head of the Church to judge that which is good and useful to it, I have resolved to remain in the future, in my writing and my acts, totally apart from matters that touch it.” He then avowed that “no one, thanks to God, is more submissive than me, in the bottom of his heart and without any reservation, to all the decisions that emanate from the Holy Apostolic See on the doctrine of faith and morals, as well as the disciplinary powers held by its sovereign authority.” Lamennais came to this position only after he had “questioned his conscience,” which assured him that accusations that he was acting in bad faith had no merit.63

Lamennais may have hoped that this statement would settle matters, but it was far from doing so. Instead, it was read by his enemies as an equivocation, an attempt to draw his own lines between politics and religion, and between papal authority and the individual conscience. A subsequent letter, written in November, only served to make the Vatican even more suspicious, as Lamennais combined his commitment neither to write nor approve anything that was contrary to the apostolic tradition as promulgated by the church with an assertion that carved out significant space for disagreement. Tellingly, Lamennais claimed that “my conscience makes it a duty” to draw a distinction, so that “if with regard to religion the Christian must only listen and obey, he remains, with regard to the spiritual power, entirely free in his opinions, his works, and his actions in the temporal order.”64 Between August and November “conscience” had taken on a new and more active role for Lamennais, for it was no longer being interrogated prior to an action but was now compelling him to act.

It is shocking to read the third and final letter that Lamennais wrote to Gregory XVI on December 11, given his increasingly robust sense of the duty to resist imposed by his conscience. Although he had been discussing a long explanatory note with Archbishop Quélen, in which his previous position was spelled out in more detail, he wrote instead (in Latin) a note of less than fifty words saying that he “accepted absolutely the doctrine of [Mirari vos], and would neither write nor approve anything that contradicted it.”65 By this time, however, financial stress and the opposition of his local bishop in Rennes, who suspended him from priestly functions, had brought Lamennais to Paris. Living with Gerbet in a poorly furnished apartment on the rue de Vaugirard, Lamennais was in poor health, suffering from “violent spasms, fever every night, no sleep,” as he wrote to his friend the Marquis de Coriolis.66 When a hostile letter from Cardinal Pacca arrived in late November, in the midst of his conversations with Quélen, Lamennais was exhausted and in despair. Giving up, he abjured his position because, as he wrote to Montalembert three weeks later, he sought “peace at any price.” At that point, he admitted that he would have signed any statement at all, even “the declaration that the Pope is God, the great God of heaven and earth, and that he alone must be adored.” But this “deification” of the pope “would have been invincibly loathsome to my conscience.” Reflecting on his situation, Lamennais was led to “very great doubts on several points of Catholicism, doubts which, far from weakening, have only grown stronger.”67

Throughout 1833, while Lamennais was struggling with Rome, he was also writing The Words of a Believer, the book that led to his definitive break with the church. Influenced by both the prophets of the Old Testament and Mickiewicz’s Book of Polish Pilgrims, The Words of a Believer is a series of short prose poems aimed at a popular audience, a passionate appeal for Christian solidarity as the basis for a new world of political liberty and social justice. Lamennais knew that this text would provoke a papal reaction, but “the abominable system of despotism that is developing everywhere disgusts me so much that at this moment silence on my part would be as infamous as direct approval.”68 Certainly Lamennais still had Poland in mind, but in France as well the early 1830s were years of danger in which popular movements inspired by the July Revolution pushed against an increasingly repressive regime. A republican-inspired uprising in Paris, later to be memorialized in Hugo’s Les misérables, left more than one hundred dead in June 1832. Socialist ideas circulated in the press and helped inspire a massive strike in the silk industry of Lyon in 1834, followed by an armed uprising suppressed by the army. In its efforts to gain control the government passed legislation severely restricting freedom of association and the press in 1834, measures that were particularly odious to Lamennais.69 At the same time, in March 1834, the Catholic hierarchy, through the offices of Archbishop Quélen, once again renewed its efforts to push Lamennais to declare his “perfect obedience” and “inviolable devotion” to the pope.70 Exasperated and angry at himself for his recent surrender, as well as at the church for its unrelenting assault, Lamennais resolved “to save my conscience and my honor,” as he wrote to Montalembert, by publishing his incendiary book.71

The Words of a Believer was an enormous success, surpassing even the triumph of the Essay on Indifference. Within months tens of thousands of copies had been printed, with translations appearing in all the major European languages.72 One correspondent reported to Lamennais that people were renting copies in a lending library near the Odéon and reading it by the hour.73 Franz Liszt could not contain himself in his letter to Lamennais, whom he had befriended earlier in the year: “Sublime, prophetic, divine! . . . From this moment on, it is evident . . . that the Christianity of the nineteenth century, that is to say the entire religious and political future of humanity, is in you.”74 Such over-the-top enthusiasm was matched, unsurprisingly, by the horrified response of the Catholic hierarchy. The abbé Garibaldi, chargé d’affaires of the Holy See at Paris, filed his first report to Rome on the very day that Words appeared, the first of several that pilloried the work as the result of a “profoundly malicious calculation,” condemned its democratic tendencies, and compared it unfavorably to the Koran.75 The papal nuncio at Venice, Monsignor Orsini, wrote of Metternich’s consternation, and Cardinal Lambruschini, the pope’s secretary of state, provided a scathing report that informed Gregory’s condemnation of Words in his June encyclical, Singulari nos.

Gregory XVI’s encyclical was vitriolic, accusing the “wretched author” of betraying his oath and composing a book that though “small in size is enormous in wickedness.”76 For all its venom, the analysis in Singulari nos is nonetheless accurate in identifying as principal themes of Words the condemnation of monarchy and the prediction of a popular revolution that would destroy it. In one startling scene Lamennais imagines seven kings participating in a black Mass, where they drink blood from a skull at an altar, curse Christ, and conspire to subvert the clergy to preach submission to their will.77 Monarchs will eventually fall, he contends, but only after a terrible period of “great terrors and wailing,” when “men will be seized with a thirst for blood and adoration of death.”78 Lamennais might well have pled guilty as charged to the papal complaint that Words had as its goal “to dissolve the bonds of all public order and to weaken all authority.” The papal condemnation was correct as well in its judgment that Lamennais had consciously adopted the role of prophet and used scriptures and references to Jesus and the Trinity in order to provide a religious sanction for revolution. Lamennais claimed that because he refrained from any specific reference to the Catholic Church, he was still complying with his oath not to deal with matters of faith and morals, but his political vision is nonetheless rooted in a messianic and even millenarian form of Christianity.79

The Words of a Believer is a political and religious tract that describes a decomposing monarchical system that will be replaced by a Christian community defined by mutual love, social solidarity, and justice. To judge by this text Lamennais was only marginally concerned with freedom of conscience as an individual right as he worked through his religious ideas in the critical years of 1832–1836.80 But as Lamennais expected, this open challenge to papal authority meant that, for him and his friends, the issue of freedom of conscience in relationship to the church could not be avoided. Could Lamennais still act as a priest, or even consider himself a Catholic, given his decision to flout papal authority with a book that would draw enormous attention, and raise obvious questions about his religious commitments?

Charles de Montalembert was the most devoted of Lamennais’s followers, loyal to the master even when others, including Lacordaire, began abandoning him in the aftermath of Mirari vos. Their struggle to reconcile obedience and liberty in the 1830s reveals an odd symmetry with the crisis that had led to Lamennais’s ordination twenty years earlier. Once again Lamennais was challenged by those closest to him to abandon his own will and submit to the authority of the church. And the abbé Bruté made another appearance as well, trying again to win his old friend for the church, as he had when Lamennais was pondering the priesthood. The arguments of Montalembert and Bruté recall those of the earlier crisis, and in a sense so does Lamennais’s response, made through a prolonged and painful dialogue with his friends and himself about his obligations to his conscience and his church. Their exchanges offer us a privileged position from which to observe how these individuals grasped religious liberty as an intellectual problem, but also as an existential choice at a decisive moment in their lives, and in the history of European Catholicism.

In the days just following the appearance of Mirari vos, the first condemnation of Lamennais and L’Avenir, it was Montalembert’s faith that was most severely shaken, and it was Lamennais who preached submission to the pope and resignation to God’s will. For Montalembert, the encyclical meant “the ruin of political and religious life, of my most sacred hopes, of my entire future. . . . For the first time in my life I have doubts about this religion, this Church to which I have consecrated my life!!” But Montalembert observed that in the face of this blow “M. Féli is admirable. He doesn’t hesitate for a moment on the position to take, it is submission and silence. It is not for us to save the Pope: he is the one that God has charged with directing the Church for good and for evil. Let God’s holy will be done!”81 These first responses were just the beginning of an extended conversation conducted over the next four years, as master and protégé battled with themselves and eventually with each other about the obligations they had to the church and to their own consciences.82 Of course, others were involved in this drama as well, with Lacordaire playing a crucial role, vying with Lamennais for the loyalty of Montalembert throughout 1833 and 1834. Lacordaire had walked away from Lamennais’s retreat in La Chênaie in December 1832, breaking definitively with his master over the need to submit fully to Rome. As Carol Harrison has shown, for the next two years Lacordaire sought to sustain his friendship with Montalembert in letters full of passionate concern. In Harrison’s terms, Lacordaire and Montalembert were “romantic Catholics,” drawn to each other through a shared Catholic spirituality that they saw as the basis for fraternal support and active citizenship among men.83 Lamennais and Montalembert shared a similar relationship, but the love between them was more filial than fraternal. For Montalembert, mourning his father, who died in 1831, and alienated from his mother for her meddling in his personal life, Lamennais was “my father and my mother,” someone whose love would endure even though he knew better than anyone his protégé’s many faults.84 As he reflected on the disasters of the past year in January 1833, Montalembert wrote to his guide that his one consolation was that “in this year you began to call me your child and to treat me as such. . . . I sincerely bless God for this grace. What would I do in this world if I didn’t have you, my beloved father, to tie my life to yours, to live from your faith and your hopes?”85 Lamennais was no less effusive, writing to Montalembert as his “beloved child” whose “tenderness consoles my last days, otherwise so sad, and which my heart gives back to you, believe me, with all the love in its power to give.”86 Political and religious differences eventually would drive Montalembert and Lamennais apart, but this rupture between intimate friends brings to mind the emotional pain in Jewish families when one of their members converted, considered in chapter 3.87

Freedom of conscience emerges as the crucial issue faced by Montalem-bert and Lamennais, as traced in their correspondence between 1833 and 1836. During this period, when Montalembert was traveling in Germany and Italy, they stayed in close touch, exchanging dozens of letters full of news and gossip.88 Political events in Europe were a central concern, most obviously in their collaboration on the publication of Mickiewicz’s Book of Polish Pilgrims. The reports and maneuvers of both their friends and enemies in Rome, Paris, and Vienna were another preoccupation, as they considered the gloomy prospects of their proposed marriage between liberty and Catholicism. But as the pressure on Lamennais to submit continued unabated, the two friends circled back more and more frequently, and with ever greater intensity, to the question of conscience. The publication of Words established the pivotal point that forced Lamennais and Montalembert to consult their consciences, their Catholicism, and each other in deciding how they understood the meaning of religious liberty. Montalembert had a clear premonition of the problems to come when he first read Words during a visit to La Chênaie in the summer of 1833, and he advised Lamennais not to publish it.89 As soon as he received his copy in May 1834, Montalembert knew that the decisive moment had arrived, for as he wrote to his master, after Words it would no longer be possible for Lamennais to try to protect himself by insisting that he was concerned only with temporal matters, leaving the spiritual dimension to the church. “The question will be to obey or not to obey, to be or not to be catholic. This is the infallible alternative to which you are reduced, and I tremble in thinking that the outcome of this alternative is doubtful.”90

In responding to Words Montalembert expressed some reservations about the evolution of Lamennais’s ideas. Perhaps his master had gone too far in his attacks on authority, both civil and ecclesiastical, and he was “very saddened to see direct attacks on property.”91 On this last point Lamennais himself moved quickly to distance himself from socialist ideas by writing a new chapter in defense of property within a month of the publication of the first edition.92 But Montalembert’s principal objections were practical rather than substantive; Lamennais might on the whole be right, but publishing Words, with the inevitable papal condemnation to follow, was inopportune. “I see . . . that you accept with joy these tests in order to be faithful to the voice of your conscience, which orders you to defend justice and truth. I am all the more ready to feel the truth of this objection because your conscience, I can say it, is mine; there is not one of your complaints against current society, not one of your attacks against tyranny, not one of your hopes for the future which are not etched most profoundly on my heart, that I haven’t repeated a thousand times and would repeat a thousand times again. I accept your position all the more because I am myself dominated by the force of conscience: in order to obey it I have condemned myself to solitude and exile.”93 Montalembert’s solution to his dilemma had been to live an isolated life, traveling in Germany and Italy, and keeping silent, a tactic that allowed him to preserve his conscience while avoiding a clear break with the church. This was the same path that he had hoped Lamennais would follow; when he didn’t, and instead published Words, it created a new situation that led them to a final confrontation over conscience and Catholicism.

Although the personal cost was high, in the end Montalembert surrendered his personal judgment and accepted that of the church. Standing behind Montalembert’s growing uneasiness was the sense that in the end Lamennais was betraying his own principle of obedience to authority, which he had maintained even as he moved to embrace liberalism.94 When Lamennais was faced with papal pressure in 1833, Montalembert wrote to him that “Providence led me to open [The Imitation of Christ] to Chapter IX of Book I, entitled ‘Of obedience and renunciation of one’s own sense.’ I read with profound emotion this beautiful chapter and especially your reflection on it; I immediately thought of you and wondered how it would be possible for the author of these lines ever to give a better example of the most humble and blind obedience.” A few months later, in April 1834, it was Lamennais’s first polemical masterpiece, the Essay on Indifference, that came to mind when Montalembert wrote that he “was unable to imagine how one could logically distance oneself from the Church, without separating as well from Christianity, as you yourself so admirably demonstrated in the Essai.”95

Montalembert preached obedience and consistency to his master (and to himself), but these were not issues of merely human significance, signs of personal integrity, they were also essential for the salvation of souls. Montalembert continued to affirm his commitment to Lamennais’s principles even after the condemnation of Singulari nos, but he pleaded with his master to abjure them nonetheless, because “I confess that the salvation of my soul, and of yours, are more dear to me [than these sentiments]; and I believe that this salvation can be compromised in preferring the uncertain to the certain, in obeying our reason and our own conscience rather than the inspirations of humility and submission.”96 In submitting to Rome Lamennais would be sacrificing himself, accepting humiliation and defeat from the perspective of the world, but in doing so he would be following the model of Christ, and saving his soul. “You will respond, I know, that the conscience is invincible, and I would say that after having reflected well on this point I am persuaded that the Christian must not obey exclusively his conscience and that there are cases where he must above all obey!” This was the choice Montalembert made, a wrenching decision that he both embraced and regretted. Following his formal submission in December 1834 he wrote to Lamennais that with this act he had done “great violence to my most deeply rooted convictions. . . . But I preferred this violence to the possibility of finding myself one day outside of this Church that alone offers me consolations for this intimate suffering that no political or intellectual activity would be able to relieve. I feel most profoundly the cruelty of putting myself in contradiction with myself, of destroying and denying in a sense everything that one has loved, defended, everything on which one has founded his life; but my life has already been so broken by causes outside my will that it matters little if I deliver one more blow from my own hand.”97 In the end Montalembert acknowledged that he was “Catholic above all.” He had been willing to follow his master “to the frontiers of Catholicism. But beyond these frontiers, no; because a law higher than all affection or all human conviction stopped me.”98

Lamennais was distraught by the growing separation between him and Montalembert, but he was unconvinced by the appeal to authority, even when supported by his own past arguments. Instead, in responding to his young friend he articulated with ever greater clarity his commitment to freedom of conscience, a position that led him first to abandon the priesthood, and then to cease to be a Catholic. In the face of Montalembert’s call to humble himself and submit after the condemnation of Singulari nos Lamennais responded that he acknowledged the possibility of being wrong but nonetheless was obliged to follow his conscience. “Everyone, after all, has only his opinion, and no one is so sure of his own that he can judge that of another with an unbefitting arrogance of infallibility. . . . I well know that I may be mistaken, and it is why I listen to everyone and don’t condemn those who think otherwise than I do. But at the same time, my conviction, whether it be right or wrong, is so profound that the opinion of others, without reasons which strike me, cannot shake it in any way or to any degree. What do those who blame me do? They follow their conscience and their reason. Why would I not have the same right?”99