3. Prodigal Sons and Daughters?

Jewish Converts and Catholic Proselytism

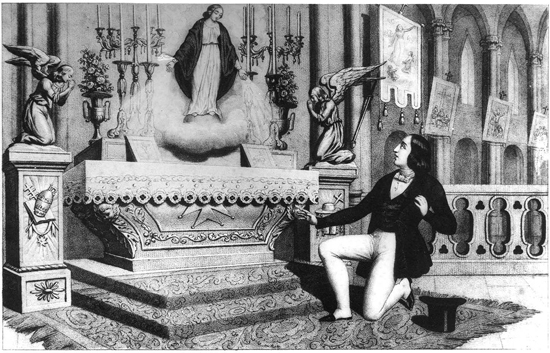

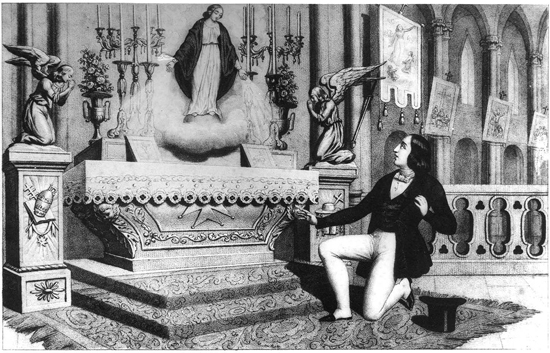

In January 1842, Alphonse Ratisbonne, a young Jewish banker from Strasbourg, was visiting Rome, a tourist stop during a visit to the Middle East designed to improve his health. By chance he ran across a school friend, Gustave de Bussières, and through him became acquainted with his brother, Théodore de Bussières, a Lutheran convert to Catholicism. Théodore was intensely devout, and his zeal led him to devote several days to Ratisbonne, showing him the sights of Rome, hoping to convert him. This might have seemed a fool’s errand, for Ratisbonne insisted that he was born and would die as a Jew, and he apparently responded to Bussières’s proselytism with ridicule. But he took up a dare offered by his new friend and agreed to wear the “Miraculous Medal,” with its image of the Virgin with outstretched arms, which had become an enormously popular talisman over the previous ten years. On January 20 Théodore and Alphonse paid a brief visit to the church of Sant’Andrea delle Fratte, so that Théodore could make arrangements for the funeral of the Count de La Ferronays, another French Catholic expatriate in Rome, who had died suddenly two nights before. Leaving Alphonse in the rear of the church, Théodore talked briefly with one of the monks and then returned to seek his new friend. He found Alphonse collapsed in tears and virtually speechless. Here is how Alphonse later described what happened to him: “I saw standing on the altar, clothed in splendor, full of majesty and sweetness, the Virgin Mary, just as she is represented on my medal. An irresistible force drew me towards her; the Virgin made a sign with her hand that I should kneel down; and then she seemed to say: That will do! She spoke not a word, but I understood everything.”1

Figure 5. The Conversion of Alphonse Ratisbonne, January 20, 1842. Archives de Notre-Dame de Sion.

Within a day the story of Alphonse Ratisbonne’s miraculous conversion was circulating in Rome, and he quickly became an object of enormous public attention. Ratisbonne was baptized just eleven days after the apparition, before an overflowing crowd at the Jesuit church in Rome, the Gesù, by Cardinal Patrizi, the vicar general of Pope Gregory XVI.2 The sermon welcoming him into the church was preached by Monsignor Dupanloup, a rising star in the French church, who happened to be in Rome at the time.3 By early February Alphonse’s brother, Théodore Ratisbonne, who had previously converted and been ordained as a Catholic priest, was preaching about the miracle to large crowds at the church of Notre-Dame des-Victoires in Paris.4 In June an investigation ordered by Cardinal Patrizi concluded that the conversion was incontestably miraculous. Over the next few years the apparition and conversion of January 20, 1842, became a central element in the Marian revival that swept through France in the nineteenth century.5

Catholics were delighted by the conversion of Ratisbonne, but his family was deeply distressed, especially because he had been engaged to marry his cousin Flore in the near future. Although it is not clear how the family first heard the news, by February Alphonse was engaged in a painful correspondence with his uncle Louis, who accused him of being “the assassin of his fiancée,” who was also Louis’s daughter.6 Alphonse’s conversion was painful for himself as well, for although his first thoughts after the apparition were of his brother Théodore, and filled him with “unspeakable joy,” he then considered the rest of his Jewish family. In thinking of them, “tears of compassion were mingled with my tears of love. Alas, that so many should go quietly down into this yawning abyss with their eyes closed by pride or by indifference! They go down and are swallowed up alive in this horrible darkness! And my family, my fiancée, my poor sisters!!! Oh! Torturing anxiety! My thoughts were of you, my beloved ones! My first prayers were for you!”7 Alphonse avoids referring to hellfire, an indication of either delicacy or denial about this particularly fearful punishment, but he makes it clear nonetheless that conversion meant salvation for Alphonse and that eternal damnation awaited his family, unless they too converted.

As we saw in the last chapter, the Wandering Jew and similar figures in French culture offered models with which the French could explore thoughts and feelings about religious liberty. The story of Alphonse Ratisbonne shows us that the pain and stress, relief and consolation displayed in books and on the stage also occurred in drawing rooms, churches, and synagogues. The public controversy that followed Alphonse’s baptism confirms as well the intense interest in conversion stories, and the questions they raised about individual religious liberty and family solidarity. In this chapter I will recount the stories of David Drach, the Ratisbonne brothers, and Olry Terquem, all of them prominent in the Jewish community, whose conversions drew public attention between the 1820s and the 1840s.8 I will also consider the work of the Congregation of Our Lady of Sion, a community of sisters founded by Théodore Ratisbonne and dedicated to the conversion of Jews, which gained notoriety in the 1840s. The stories of the young girls placed with the congregation provide another perspective on the experience of liberty among French Jews, calling attention to the ways in which age, class, and gender intersected with belief in shaping religious attachments and identities. In telling these stories I do not assume that the accounts of Alphonse Ratisbonne and others are transparent depictions of conversion; many of them suggest the influence of the melodramatic conventions explored in chapter 2; it is easy to imagine an operatic production being built around the life of Alphonse Ratisbonne. But the possibility of such influence does not mean that the emotions expressed by him and his family, and by other converts as well, should be deemed inauthentic. Understood as “emotives,” to use William Reddy’s term, the stories told by converts both shaped and expressed the hopes and fears involved in reconciling religious belief, personal liberty, and family loyalty.9 Before entering into the lives of the converts, however, we should have in mind the particular situation of Jews in a France where religious liberty was a declared but not fully realized principle.

Religious Liberty for Jews?

As we have seen in chapter 1, religious freedom as a human right expressed in written constitutions emerged in the late eighteenth century, with Article 10 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man as a key text marking this development. Despite the hopes of some Jewish leaders and their Christian supporters of the time, this right was not at first understood as applying to French Jewish communities, which were concentrated in Alsace and Lorraine in the east, in Bordeaux and Saint-Esprit in the southwest, and in Avignon and other cities in the territories of the south ruled by the pope until 1791.10 It was only in January 1790 that the Constituent Assembly agreed to grant those known as “Portuguese” Jews, the relatively assimilated Sephardic community of Bordeaux and Saint-Esprit, equal rights as French citizens. It took another eighteen months before the Assembly, in one of its last acts, accepted all Jews, including the Ashkenazic Jews from the east, as citizens of France. The basis for Jewish emancipation, famously articulated by the Comte de Clermont-Tonnerre in his speech to the Assembly in December 1789, was an understanding that rights were granted to the Jews only as individuals. Becoming French citizens equal to all others meant abandoning the corporate structures within which they had previously defined themselves. “To the Jews as a Nation, nothing; to the Jews as individuals, everything. They must renounce their judges; they must have none but ours. . . . They must not form a political corps or an Order in the state; they must be citizens individually.”11 The delay in enacting this policy into law suggests the wariness with which many legislators in France regarded the Jewish community, a nation apart, governed internally by its own leaders under the corporate system that characterized Old Regime France.

In the decades that followed their supposed emancipation French Jews continued to be regarded as a separate and suspect people. Even supporters of Jewish emancipation, such as the abbé Grégoire, saw the need for “regenerating” a community whose manners and morals were condemned as insular and greedy.12 During the Napoleonic era this reform impulse continued to intersect with traditional hostility, in the convocation of a Jewish Assembly of Notables in 1806 and of the Grand Sanhedrin in 1807. Through these assemblies Napoleon hoped to apply pressure to the Jewish elite to acknowledge the legal changes that established the French state as the supreme authority over the lives of individuals and accept a process that would eventually dissolve the Jewish community. The questions he posed to the 1806 Assembly reveal a sharp resentment of communal separation, and a desire to advance a program of assimilation. In question three, which provoked the most controversy among the notables, the emperor asked, “Can a Jewish woman marry a Christian and a Christian man a Jewish woman? Or does the law allow Jews to marry only among themselves?”13 The answer given by the notables, and confirmed by the rabbinic experts of the Sanhedrin, accepted the legality of intermarriage between Christians and Jews, because Christians were not idolaters and both religions adored the same God. But it also distinguished sharply between the civil and religious spheres, accepting that a Jew and a Christian might have a legally binding marriage but asserting that rabbis would not bless such unions, which would therefore have no religious sanction.14

Scholars have scrupulously analyzed the work of the notables and the members of the Sanhedrin, who were engaged in a delicate balancing act in which they struggled to preserve communal integrity while affirming their acceptance of a French national identity.15 From my perspective, the response to question three reveals an ambiguous attitude on the part of the Jewish elite about the relationship between an individual Jew and his or her community that might result from intermarriage. The notables and the members of the Sanhedrin were fighting back against the intent of Napoleon, and of the “regeneration” program in general, to use emancipation as a step toward assimilation and eventually conversion. Their answer discouraged intermarriage, even while it acknowledged its civil legality, thus affirming the right of individual Jews to marry outside of their faith and to retain their Jewish identity. But in trying to balance individual rights with communal integrity Jewish leaders did not and perhaps could not explain how such individuals might actually think about themselves, and how they might in fact relate to a Jewish family and community.

As a result of the Napoleonic assemblies the empire created a new set of institutions charged with organizing the Jewish communities in France, and with managing their relationship to the state. This system of consistories granted Jews a status similar to that of the other organized religions, Catholicism and Protestantism, but did not result in full equality. The “infamous decree” that was enforced between 1808 and 1818 is the clearest indication of how the state continued to discriminate against Jews, thus denying them the equal rights they had supposedly been granted. This Napoleonic ordinance severely restricted the rights of Jews to lend money and collect debts, required them to obtain a special license to engage in commerce, and prohibited them from moving into the two Alsatian departments in eastern France.16 Although the “infamous decree” was allowed to lapse in 1818, the policy of placing Jews in a special category, subject to particular laws that did not apply to other citizens, continued during the Restoration (1814–1830), despite the fact that the Catholic Bourbons promulgated a charter that affirmed religious liberty.17 While Catholic and Protestant ministers were paid by the state, Jewish rabbis were compensated only in 1831. Jews were also still required to swear a special oath in legal proceedings, the “more judaico,” an obligation that remained in force until 1846.18

The exclusion of Jews from full citizenship expressed in legal terms an animosity that contributed to an enduring social separation. According to the influential writer and political theorist Louis de Bonald, “Jews cannot be, no matter what one does, and never will be citizens in a Christian Europe without becoming Christian.”19 The July Revolution of 1830, which brought Louis-Philippe to the throne of France, seemed to offer Jews the possibility of full equality, as indicated by the state’s willingness to pay rabbinical salaries. Historians of French Judaism have judged the July Monarchy (1830–1848) as an important stage in the process of Jewish integration. Drawn increasingly to Paris, which was becoming the new center for French Judaism, Jews became prominent in the world of business and law, most notably in the careers of the famous banker Jacques de Rothschild (1792–1868) and the lawyer and politician Adolphe Crémieux (1796–1880), who served as the minister of justice for the Second Republic in 1848.20 An active Jewish press emerged, with the Archives Israélites proposing greater efforts at integration, while L’Univers Israélite adopted a more conservative posture.21 Schools grew in number and quality, with enhanced support from the state.22 In intellectual circles Adolphe Franck and Salomon Munk began careers that would eventually lead to appointments at the Collège de France. Franck’s thesis on the Kabalistic texts, published in 1843, linked this Jewish mystical tradition to principles of universal reason and established a new level of interest in Jewish religious culture.23 Salomon Munk, an immigrant from Germany, brought to France the scholarly and religious interests of the Berlin Society for Culture and Science of the Jews, the same group that Heinrich Heine joined in 1822. Munk’s scholarly career began when he was made curator of oriental manuscripts at the Bibliothèque Nationale in the 1830s, but he maintained throughout his career close ties with the Jewish community, becoming secretary of the Central Consistory in 1844. In 1862 he was called to the chair of Hebrew at the Collège de France, after Ernest Renan was dismissed because of the scandal surrounding his Life of Jesus (La vie de Jésus).24 Taken together, these achievements suggest that the Jewish community in the 1830s and 1840s successfully managed to preserve a clear sense of its identity even while it made substantial progress toward integration into the French nation.

The success that Jews experienced in France during the July Monarchy generated, as a paradoxical consequence, a reaction in which traditional resentments were recalled and refined to fit the new circumstances of the nineteenth century. In the 1840s the slogan “Rothschild, king of Jews,” became a commonplace among socialist writers such as Alphonse Toussenel, inaugurating a long line of antisemitic attacks directed at the financial and political power of Jewish bankers.25 Even more troubling was the revival of the accusation that Jews murdered Christians in order to use their blood for ritual purposes. This myth was at the center of the Damascus affair of 1840, when an Italian Capucin monk disappeared in that city, resulting in a wave of rioting directed against the local Jewish community, and a campaign of torture against Jewish suspects that resulted in false confessions. The affair drew international attention, with the French consul the Comte de Ratti-Menton in Damascus playing a leading role in fomenting an antisemitic reign of terror.26 In Paris Adolphe Thiers supported Ratti-Menton in the Chamber of Deputies, hoping to capitalize on the incident in order to gain domestic political advantage. In Europe the Jewish communities of England and France mobilized to support their fellow Jews; an international committee headed by Moses Montefiore, Adolphe Crémieux, and Salomon Munk traveled to the Middle East and managed to obtain the release of Jewish prisoners and to defuse the crisis. But the incident generated hostility across religious lines, as is evident in the response of the Catholic daily L’Univers, which insisted that the blood libel was plausible based on the Jewish hatred of Christians as documented in the Talmud. According to L’Univers Jewish integration was a sham designed to hide their primary loyalty to the Jewish community: “The adoption by Jews of the political opinions and social customs of nations that have received them in their midst does not at all indicate a complete identity. A people might well adopt new external habits, but as long as it professes a secret religion whose mysteries and beliefs cannot be penetrated, they will remain foreigners who deserve to be regarded with suspicion.”27 In this passage we hear French Catholics doubt that Jews can really become French, even if they appear to have adopted the habits and manners of their fellow citizens. As we will see, a similar suspicion emerged about those Jews who not only acted like French citizens but accepted baptism and became Catholics.

Anxiety over the issue of Jewish assimilation was based in part on a developing sense of immutable national differences.28 But individual conversions also challenged the traditional values of family honor and paternal power. As we saw in chapter 1, Emily Loveday, the Protestant convert to Catholicism, posed a problem for Catholic writers committed to the patriarchal family but also interested in promoting the interests of the Catholic Church. The importance of loyalty to family religious tradition was expressed in a popular aphorism which claimed that “an honest man doesn’t change his religion.” Joseph de Maistre addressed this issue directly in a letter published in 1824 in the Mémorial Catholique and then reprinted several times as a pamphlet. Maistre at first questioned this principle, which he acknowledged was widely accepted, as violating the right everyone had to assure his or her own salvation. But he ended by advising his correspondent, a Protestant woman who wished to convert, to be prudent, to delay baptism, and not to disrupt the family with a public break.29 Twenty years later David Drach, whose conversion I will deal with shortly, condemned the same “impious principle that an honest man doesn’t change his religion,” which was used to oppose Catholic proselytism and conversion.30 To judge by the language of Maistre and Drach, the ideal of the “honest man,” characterized by modesty, civility, and moderation, had expanded by the nineteenth century to include as well a sense of loyalty to family religious tradition. “Honesty” can be linked as well to what William Reddy has described as “the democratization of honor,” a process at work in the early nineteenth century in which nonaristocratic families became increasingly concerned with “the keeping up of appearances, the avoidance of shame by concealment.”31 Converts were in the shameful position of asserting personal convictions that broke the solidarity of their family, which explains why at times they kept their conversions secret from parents and relatives. Secrecy and shame, belief and belonging, are dominant themes in the stories of Jewish converts that I turn to now. Their decisions, and the ways in which they were communicated to the public, illuminate how Jewish-Christian antagonism was being reshaped in an age of expanding religious liberty and confirm the cultural fascination with this issue. They show as well that decisions to change religion involved real choices, ruptures, and some reconciliations in the lives of Jewish individuals and their families.

David Drach: A Rabbi Converts

The baptism of David Drach (1791–1865) on Holy Saturday of 1823 in a dramatic public ceremony conducted by the archbishop of Paris at the cathedral of Notre Dame shocked the Jewish community of Paris and delighted Catholics.32 Drach, the founding director of the first school for Jewish children in Paris, was the son of an Alsatian rabbi and the son-in-law of Emmanuel Deutz, the grand rabbi of France. In his own account of his conversion, first published in 1825, Drach described himself as a model rabbinical student who nonetheless was drawn to Christianity.33 Although Drach clearly tailored his story to his own advantage, the details of his early contacts with Christians are plausible: conversations with a Catholic servant as a child and with a Catholic priest at the age of seventeen, when he was serving as a tutor for a Jewish family in Ribeauville. This last connection took place, according to Drach, in the mayor’s home, and he praised this “estimable family [that] had the charitable discretion to keep their silence about my interest, which they no doubt attributed to my youth.”34 In this same period Drach decided to teach himself Latin and Greek, perhaps another indication of his early inclination to explore the borderland between Judaism and Christianity. This interest apparently upset his father, but he pursued his study of languages nonetheless, establishing an important base for his subsequent conversion and scholarly career. Drach’s sudden resignation and baptism in 1823 took the Jewish community by surprise, and we have only his own testimony about when and where his journey began. But there is no particular reason to doubt his narrative, and however we judge the veracity of its details it is clear that for several years prior to his baptism he was drawn to Christianity, an inclination he kept secret from his family and community.

Like many other Jews in the early decades of the nineteenth century, and like ambitious young men in general, Drach was drawn to Paris, which was emerging as the new center for French Judaism, a place where Jews could hope to forge connections with a gentile world that was offering them limited but real opportunities for advancement and assimilation. In the decade after his arrival in the capital in 1813 Drach managed to combine a promising career within the Jewish community with an active pursuit of contacts with French institutions and individuals. He became a private tutor for an elite Jewish family and the secretary to the Central Consistory and published several religious texts in French, for families who preferred to worship in the language of the nation that had recently granted them the right of citizenship. But he also earned a baccalaureate degree and a teaching credential from the Ecole normale for elementary education and taught classical languages for a time at the Institut des langues étrangères.35

Drach’s interest in scholarship and religious reform drew him in the early 1820s to the Septuagint, the translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek made in the third century BCE, a text he hoped to translate back into Hebrew as the basis for a new and purer version of sacred scripture than the one currently used by French Jews. This project brought him into contact with Silvestre de Sacy, the most distinguished orientalist of the period as well as a devout Catholic.36 With Sacy’s support Drach, along with Michel Berr, was one of two Jews nominated for membership in the newly organized Asiatic Society, where he found support for his program of translation and Jewish reform.37 Drach’s fascination with the Septuagint is at the heart of his own account of his conversion, where he claims that reading this purer version of Jewish scripture proved to him that Christ’s coming had been foretold by the prophets. This was, of course, a standard argument used by Christians to justify their belief in Jesus as the promised Messiah, but Drach pursued it with a combination of unusual linguistic skills and a passion for a microscopic examination of the Bible. Drach’s knowledge of Hebrew also led him beyond the Hebrew Bible to the other sacred texts of Judaism, the Talmud and the Kaballah, for signs of their correspondence with Christianity.38

Drach emphasized the importance of a detailed examination of sacred texts as the basis for his conversion, but in choosing Paul for his Christian name he pointed as well to God’s grace as the compelling force pushing him to abandon Judaism. “Just like Saint Paul, my blessed patron, I was raised at the feet of the doctors of Israel; like him I was converted by the voice of God, without the cooperation of any man; like him my conversion earned me the hatred and persecution of the Jews, my brothers.”39 Drach’s description of his conversion as a result of his own will, but also of God’s intervention, as based on personal study, but also divine grace, leaves open the question of how one might ultimately account for his decision. In its insistence on the role of long years of personal study as well as the infusion of grace Drach’s story mirrors Augustine’s account of his conversion in the Confessions, a case that might better fit Drach’s than Paul’s sudden illumination on the road to Damascus. And like Augustine’s account, Drach’s narrative also allows for the important role of personal connections, although in the case of Drach these involved a rupture with his family and not the reconciliation that brought Augustine and his mother, Monica, together as Christians.

Soon after his arrival in Paris Drach was taken on as a tutor in the home of Baruch Weil, who was on friendly terms with his Christian neighbors, Louis and Adèle Mertian, Catholics from Strasbourg. Drach soon began teaching Latin to the Mertian children as well as Weil’s and later described himself as “electrified by the edifying examples of a tender piety which I had the happiness to witness every day, for several years,” an experience that reawakened his earlier interest in Christianity.40 Through the Mertians Drach was introduced to the abbé Burnier-Fontanel, the dean of the Faculty of Theology at the Sorbonne, who provided him with religious instruction prior to his baptism, and who also initiated Drach into the Catholic liturgy. Sometime between his arrival in Paris and his conversion Drach assisted at a Catholic Mass on Palm Sunday at the church of Saint-Etienne-du-Mont and later recalled being deeply moved by a theatrical presentation of the Passion story, read by several voices during the ceremony. Although Drach’s own testimony cannot always be taken at face value, we have no particular reason to doubt an emotional reaction to such a dramatic representation of the death of Christ, which evoked a powerful aversion to the Jews who, according to the Gospel account, called for Christ’s crucifixion. It is telling, however, that in expressing this sentiment Drach shifts from the first to the second person, perhaps as a way of distancing himself from a growing resentment directed against his fellow Jews. In describing his response to the Passion, Drach writes, “You become indignant with the persecutors, you develop a great compassion for the victim abandoned without defense to their fury; a dark sadness takes hold of you. You suffer with the man.” Thinking back to this moment, Drach concludes that “the religion that generates such emotions, could it not be divine?”41 Drach’s narrative here reaches beyond itself to incorporate Catholic ritual as another powerful “emotive” used to navigate in the borderlands between religions.

Drach’s scholarly interests and contacts aroused some concern, but his Jewish colleagues apparently did not suspect the depth of his attraction to Christianity. Perhaps this was because his agenda seemed to fit with an emerging though controversial trend in Parisian Judaism to reform traditional practices and prayers, using French instead of Hebrew, and in general bringing Judaism in line with Christianity.42 The vast majority of reformers did not convert, but Drach’s spirit of innovation and his desire for connection with the Christian world would not have surprised or disturbed them, for it fit with their own sense of the need for change and accommodation to a Christian world.43

One final factor that Drach considered only to dismiss in explaining his conversion was professional and material self-interest. Hostile responses from the Jewish community spoke of substantial bribes, of offers for a lucrative position.44 From Drach’s perspective, such attacks were ludicrous, given the enormous personal price he paid and the opportunities that seemed to await him within the Jewish community, including the reasonable expectation that he would replace his father-in-law as the grand rabbi of France.45 But if we dismiss the cruder attacks that drew on the traditional caricature of the venal Jew, it is still plausible to see in Drach’s choice at least some element of personal ambition. He had been disappointed with some decisions of the Central Consistory, which refused to publish one of his works, and his school was constantly in dire financial straits. His contacts with Catholic friends and colleagues presumably gave him some hope that he could find success in their world, an aspiration that led eventually to a modestly successful but by no means brilliant career.46

Drach’s case raises the question of how to measure the different factors that help us understand his conversion, a problem that is common to all of the stories in this chapter, and throughout this book. Judgments about whether religious, or social, or selfish reasons were predominant can too easily be made using a template that reflects our own views and preferences. Rather than engage in such an exercise, I prefer to think about Drach’s decision as a complex, deeply personal but also socially mediated process, which by virtue of its complexity opens up to us the world of religious choice within which he lived.47 In the case of Drach and other Jewish converts, it is the rupture with the family that repeatedly comes back to the center of their stories.

However we judge the motives that led Drach to convert, his decision produced an enormous rift with his family and community. Following the advice of his Catholic friends, Drach at first continued to live with his wife, Sara, for several weeks, urging her to convert. Tearful scenes with Sara and angry exchanges with his father-in-law ensued. After three weeks of family strife, Sara fled with her three children, ending up in London, where she was hidden by a sympathetic Jewish community.48 Drach spent eighteen months trying to track his family down, a quest that led him from Paris to Metz before he finally succeeded, with the help of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in tracing them to London.49 There he made contact with his family and, with the collusion of a disloyal nursemaid and the local French community, including the ambassador, kidnapped his children and brought them back to Paris. Even then Drach’s conflict with the Jewish community continued, drawing the attention of the minister of the interior, who wrote to the prefect of police in Paris that Drach’s brother-in-law Simon Deutz and his friend, a M. Neymann, who worked for the Rothschild family, had threatened the former rabbi, made inquiries about the Mertian family, and might even attempt to kidnap the children again.50 No such attempt occurred, however, and under Drach’s care the children were raised as Catholics; the two girls eventually became nuns, while his son became a priest.51

For the rest of his life Drach pursued a career as a bibliographer and scholar in Paris and Rome, working first as the librarian for the Faculty of Theology at the Sorbonne and for the Duc de Bordeaux. The July Revolution of 1830, which reduced the power of Drach’s ecclesiastical and political connections, led him to Rome, where he worked for twelve years (1830–1842) as librarian for the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith. Drach returned to Paris in 1842, where he was associated with the publishing house of the abbé Migne, editing works of the church fathers.52 Drach’s scholarly work won him an honorable but modest place in French intellectual life, but he won more public attention for his role as a missionary to his former community, publishing a series of works explaining his own conversion and insisting on the “harmony” between Judaism and Christianity.

In a series of letters addressed to the Jewish community that began in 1825 Drach expressed the hope that his example, and the evidence he adduced from sacred scripture, would lead to a wave of Jewish conversions, even to the disappearance of Judaism as an autonomous religious community. The most promising but ultimately the most disappointing example of this movement that Drach claimed to see was the conversion of his brother-in-law Simon, baptized at Rome as Hyacinthe in 1828. This was the same Deutz, the son of the grand rabbi of France, who had reacted so violently to Drach’s conversion in 1823. In his effusive account of Deutz’s conversion Drach admitted that it was not yet possible to reveal the names of all those who had converted, out of respect for those who wished to keep their decisions private. But he insisted that the Jews who had been “regenerated in Our Lord Jesus Christ” in the past few years outnumbered all of those baptized over several centuries.53 Just four years later, however, Drach was forced to disavow Deutz, who became a universally detested figure after he was bribed into betraying the hiding place of the Duchesse de Berry during her hopeless attempt to regain the throne for the main line of the Bourbons in 1832.54 French newspapers were full of accounts that identified Deutz as a Jew, even though he had been baptized, and interpreted his betrayal as in keeping with the character of his people. Victor Hugo, already an established star in the literary world, wrote a poem condemning in the most vitriolic terms this new Judas who wandered the earth, another juif errant, who should suffer for his perfidious behavior.55 Drach was quick to disassociate himself from Deutz in an open letter published in L’Ami de la Religion in which he recalled that the family of his brother-in-law had “separated itself from me several years ago, breaking all the ties of nature, because it detests the principles of the Gospel.”56

There are complicated psychological dynamics lurking in the relationships of Drach and Deutz with their families and communities. Drach condemned Deutz for “breaking all the ties of nature,” but didn’t he act in a similar fashion when he broke with his family’s religious tradition? And was it “natural” for Drach, who had recently celebrated the conversion of this family member, to abandon him so quickly and to adopt so willingly the “teaching of contempt” directed at people that he also addressed as his “dear brothers”?57 Drach’s tortured attempts to formulate a coherent relationship with his former community come through clearly in his autobiographical writings, where he moves quickly from condemning his persecutors to forgiving them, as a good Christian must. “Very often the object of your persecution [converts], forgive the evil you do them, or which you try to do. If you disavow your relatives, they are happy to retain their ties to you; if you curse them, they continue to pray for you; if you slander them, they cover your wrongs with a veil of charity.”58 Perhaps the most shocking example of Drach’s hostility toward Jews was his public endorsement of the outlandish claims of Jewish ritual murder in the Damascus affair.59

Drach’s troubled relationship with Jews, and with Judaism, is palpable in his writings, in which he zealously embraces the beliefs and institutions of his new religion, and in particular the militant ultramontanism of the nineteenth century that invested absolute authority in the Catholic Church as represented by the pope in Rome.60 But there are suggestions as well in his private correspondence of shadows cast over his life as a Catholic because of his Jewish origins. During his time in Rome Drach was relentless in his pursuit of honors, writing constantly to add to the list that appeared prominently on the title page of L’harmonie entre l’église et la synagogue, which scrupulously listed his credentials: “Doctor of Philosophy of the Pontifical Academy, Member of the Asiatic Society, of the Faith and Light Society of Nancy, etc.; Member of the Legion of Honor of Saint Gregory the Great, of Saint Louis, Civil Order of Lucque, second class, of Saint-Sylvestre, etc.”61 Not all of Drach’s efforts, however, were successful, for in 1841 the Ministry for Foreign Affairs in France wrote him that it could not award him the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazare, which he had requested. In his response to Drach the minister wrote that “the person who aspires to receive this decoration must not only belong to the Catholic and apostolic religion, but also descend from Catholic ancestors. And as there has never been an exception to this rule established by ancient tradition, for persons having belonged to the Jewish religion, or who descended from parents who professed it, the King cannot violate it in this case, and regrets to find himself in the position of the impossibility of adhering to your request.”62 Behind its façade of bureaucratic politesse, this letter makes clear that Drach’s Jewish past kept him from full acceptance as a Catholic. As we will see with other converts as well, Jews were unable to escape their religious past, which provided them with a form of celebrity but also created barriers to their full assimilation to the Catholic world they aspired to join.

The dramatic events surrounding David Drach’s conversion caused enormous pain to his family and put him in the middle of a complicated conflict in which the stakes involved eternal salvation, free will, paternal authority, family solidarity, and communal loyalty. Drach struggled to resolve these issues in his personal life, but he dealt with them as well in his theological writings, which were collected in the massive volumes he published in 1844 that attempted to reconcile Judaism and Christianity. In this work, which expands on the material published in his earlier letters to his “dear brothers,” he both affirms and denies the differences between Judaism and Catholicism, a confused intellectual effort that nonetheless makes emotional and psychological sense given his personal situation. In the preface to L’harmonie entre l’église et la synagogue Drach insists on the identity of the “faith preached by the Messiah Jesus with the beliefs of our fathers.” In converting, Drach insists, he had not abandoned Judaism but had returned to “the true religion of Israel.” Converts were not so much changing their religion as “coming back to the paternal roof.”63 Drach thus embraced the values of family solidarity and filiopietism, despite the fact that he had left the religion of his father, a rabbi from Alsace, and of his father-in-law, the chief rabbi of France. This obvious incongruity perhaps explains why Drach combined an argument for conversion based on recovering a lost family solidarity with a contrary position that affirmed the absolute right of individual choice. To make his case Drach drew on the Gospel of Luke (14:26) where Christ calls on his followers to abandon their families: “Whoever comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, and even life itself, cannot be my disciple.”64 In his autobiographical comments designed to bring other Jews to Christianity Drach struggled to reconcile two narratives of his conversion, one that stressed fidelity to the religion of father and family and another that affirmed the obligation to follow God’s call and leave them behind. In Drach’s France religious liberty had become a constitutionally protected individual right, but Jewish converts who wandered from their original home faced suspicious and sometimes hostile reactions in both the Jewish and Catholic communities. Their complicated positions fueled controversy throughout this period that reveals the personal and communal anxieties that accompanied the arrival of religious liberty.

Théodore and Alphonse Ratisbonne: Divergent Roads to Rome

We have already met Alphonse Ratisbonne, converted by a miraculous apparition of the Virgin Mary in Rome in January 1842. Alphonse’s conversion provoked a family crisis all the more serious because it followed that of his brother Théodore, who became a Catholic in 1827 and was ordained a priest in 1830. Unlike the Drach family, religiously devout and with modest resources, the Ratisbonnes were an affluent banking family that had distanced itself from orthodox religious practice. Nonetheless, Théodore Ratisbonne’s story parallels in many ways that of David Drach. For both of them conversion followed an extended period of study, a time during which they were leading members of the Jewish community while secretly engaged to Catholicism. In both cases this ambiguous stage, straddling two religious communities, was based on an effort to reconcile the competing truth claims of the two religions and to avoid a devastating family conflict. In the end both Drach and Théodore Ratisbonne ended this liminal period by publicly accepting baptism, causing scandal in the Jewish community, celebrations among Catholics, and bitter tears and violent arguments with their families. Both spent much of the rest of their lives devoted to persuading other Jews to convert, proselytizing campaigns that had only modest success but that provoked substantial antagonism between the two communities.

Théodore Ratisbonne’s approach to proselytism was, however, quite different from the meticulous arguments of Drach, presented as irrefutable proof texts. Instead, Ratisbonne pursued an aggressive campaign of preaching and outreach through a new religious order founded in the aftermath of Alphonse’s conversion in 1842. The Congregation of Our Lady of Sion still exists today, but in the context of the Second Vatican Council of the 1960s it redefined its mission from converting Jews to encouraging interfaith understanding.65 But in the 1840s the congregation played a prominent role in aggressively pursuing Jewish converts, an initiative with consequences for Jewish-Catholic relations, and for the ways in which religious freedom was understood and experienced. As we will see, the conversion of Alphonse Ratisbonne in 1842, the contested conversion of Lazare Terquem, and the work of the Congregation of Our Lady of Sion show how in the 1840s the border between Catholicism and Judaism was being more closely guarded on the Jewish side, and more aggressively attacked by the Catholics. This process, accompanied by family conflicts similar to those in the Drach family, also involved a heightened confessional awareness that seeped into public opinion and constrained individual choices, even while religious liberty remained a constitutional right.

Théodore Ratisbonne’s journey away from Judaism toward Catholicism began when he was a young man from an elite Strasbourg family. Like other Jewish families from this milieu, the Ratisbonnes retained a Jewish identity and were in fact leaders in the community, but without adhering to orthodox practice. As an adolescent Théodore tried his hand at business in Paris, where he was associated with the Fould bank, run by family friends. Unhappy with this work, alienated, and feeling alone, Ratisbonne returned to Strasbourg in 1823, where he enrolled in courses in the law faculty of the university. But it was a series of private courses starting in 1823 with the young philosophy professor Louis Bautain that transformed Théodore’s life. Bautain had himself just come through a major intellectual and religious crisis. A brilliant student of Victor Cousin, Bautain had been appointed to the Collège Royal of Strasbourg in 1816 when only twenty years old, and to the university the following year. Bautain’s charismatic teaching quickly made him a hero among the youth of Strasbourg, but by 1820 he had become disillusioned with the eclecticism of Cousin and had begun to move toward Catholicism. By 1822 Bautain’s public lectures had become a matter of public controversy; accused of both political liberalism and proselytism directed at Protestant theological students, he was suspended from teaching.66 But he continued to meet students privately, in the home of Marie-Louise Humann, a devout woman from a prominent family who had played an important role in Bautain’s conversion. Bautain’s course in moral theology that began in May 1823 included two Jews, Théodore Ratisbonne and his friend Jules Lewel.67 Over the next few years Bautain’s circle expanded both in size and influence, drawing in other young Jews from Strasbourg as well as a number of figures who would go on to play leading roles in nineteenth-century Catholicism.68

Théodore Ratisbonne was overwhelmed by the charismatic teaching of Bautain, and by the sense of fellowship he found in his courses. “This was no ordinary teaching,” he wrote in a conversion narrative published in 1835, “but a veritable initiation into the mysteries of man and nature. We listened with surprise, with admiration, to the developments of this universal truth which the master took from its living source in the Sacred Scriptures, from which he drew strength, virtue, and power.”69 The sociability that brought together Jews and non-Jews in the Bautain circle was based on an explicit acceptance of the religious and moral value of Judaism, and an avoidance of the kind of disputation in which the claims of the two religions were compared and judged on the basis of some universal rational standard. At least in the early stages of the conversion process, it seemed possible for Théodore to contemplate a status in which he would be able to combine Catholic and Jewish identities, to live “as a Christian inside, as a Jew in my family, and as a deist in society.”70

Bautain did not, however, conclude his appreciation of Judaism by claiming it was equivalent in value to Christianity. Like David Drach, he combined his positive assessment with the traditional anti-Judaic position which held that blindness had prevented Jews from accepting Jesus as the fulfillment of the prophecies, and that their dispersal and abject condition was a justified punishment and a testimony to the truth of Jesus’s messianic role.71 According to Bautain the dogmas of Christianity are “the development, the accomplishment of the truths announced by Judaism.”72 Bautain’s teaching led Ratisbonne to a deep appreciation of Moses, the prophets, and the Psalms, but also to hostility toward the Talmud, seen as a corrupting influence that prevented the regeneration of contemporary Jews.

Even while he was drawn to Christianity Théodore Ratisbonne remained attached to his Jewish community and lived a dual identity for at least four years, accepting baptism only in 1827. From 1823 through 1827, Ratisbonne followed the advice of Bautain and became one of the leaders of the Jewish community in Strasbourg. The educational and charitable work undertaken by Ratisbonne and his friends made them key figures in the program of Jewish regeneration that drew in David Drach in Paris. With the support of his father, who was then the president of the Central Consistory, Théodore was named head of the new Jewish elementary school and was a founder as well of the Société d’encouragement du travail, a charitable group that helped young Jews acquire skills and jobs. He and his fellow disciples of Bautain, Isidore Goeschler and Jules Lewel, were actively involved in instruction, and their Saturday lessons drew a crowd of adults along with the children. Looking back on these days ten years later Ratisbonne was enthusiastic in describing how “the parents as well as the children, seemed to be entering a new era.”73

Théodore Ratisbonne’s desire to retain a Jewish identity was clearly related to a sense of family and community loyalty, a point that emerges from his descriptions of the tearful scenes in which he admitted to his father and his uncle that he was a Christian. Théodore recalled trying to reassure his father by affirming that “I am Christian, but I adore the same God as my fathers, the God three times holy, the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.” But he could not resist adding at the end of this litany that “I recognize Jesus Christ as the messiah, the redeemer of Israel.” His father tried to dissuade him by referring tearfully to the memory of his dead mother, and then shouting at him, which led Théodore to flee the room. But when Théodore wrote an affectionate note promising that he would not make a public show of himself, his father called him back for a reconciliation in which “the sentiments of his heart carried the day over the scruples of his conscience.”74 By the time of these conversations, however, public rumors had spread about Théodore’s conversion, and many congregants angrily accused him of using his role as teacher to proselytize Jewish children. In one stormy public meeting Théodore was able briefly to win public support by turning aside the question of his religious commitments and asking the congregation to focus instead on the good works that he had accomplished.75 Public pressure, and Théodore’s own discomfort with his ambiguous situation, finally led him to announce his Christianity at a meeting of the elders of the community. He then left home, was admitted to the newly founded school for advanced studies established by the bishop of Strasbourg at Molsheim, and was ordained a Catholic priest two years later, in December 1830, the same path followed by his two Jewish friends, Lewel and Goeschler. Together they formed a core group for a new religious congregation founded by Bautain, the priests of Saint-Louis, and for a time were given privileged treatment by Bishop Le Pappe de Trévern, who put them in charge of his minor seminary.

The baptism and ordination of Ratisbonne might be understood as resolving definitively the period of ambivalence that he had lived through in the middle years of the decade. But as with David Drach these steps could not efface Ratisbonne’s Jewish identity, which followed him throughout his career. In the early 1830s Ratisbonne and his fellow Jewish converts were regarded with suspicion as less than fully committed Catholics during a controversy over their teaching in the minor seminary. The Bautain circle was vulnerable because the philosophical position they defended throughout the 1820s and 1830s broke sharply with the “dry and unimaginative school-doctrine that was all that the ecclesiastical establishment seemed capable of offering.”76 By the early 1830s Bautain and his followers were being publicly accused of “fideism,” of basing their Catholicism on God’s grace as it acts on the human heart and will rather than on rational demonstrations that would yield a firm intellectual commitment to the church and to Catholic doctrine.77 As a result of this accusation Bautain and his followers, including Ratisbonne, were expelled from the minor seminary in 1834, lived several years on the margins of the church, and were subjected to a lengthy investigation both locally and in Rome.78

In the midst of the controversy over Bautain’s philosophy and the faith of the new converts, over eighty parish clergy responded with letters to an episcopal warning about the Bautain circle’s doctrines. Most responses were critical, condemning Bautain’s teachings and expressing deep reservations about Ratisbonne, Lewel, and Goeschler. Curé Schir of the canton of Benfeld was especially pointed in his comments: “Do we need men whose antecedents are more than questionable, whose improvised conversion inspires only a mediocre confidence, who slipped into the sanctuary without submitting to any of the tests prescribed by the holy canons?” He would have been happy to work with these priests, Schir claimed, “if they had not themselves raised a wall of separation between them and us, affecting an insulting contempt for anyone who was not part of their coterie.”79 From Schir’s perspective, Ratisbonne and his colleagues remained arrogant and insular, convinced of their own truths and scornful of all others. They had not, and perhaps could not, break through the wall separating Jews and Christians.

Théodore Ratisbonne was not an idle observer in the conflict involving the Bautain circle in the 1830s. He contributed a pamphlet justifying himself and his fellow Jewish converts, whose conversions had been questioned by Bautain’s critics as the result of “sentiment, taste, enthusiasm, fanaticism! Why? Because these conversions have not been achieved through syllogisms. . . . We accept, we the descendants of Abraham, and today priests of Jesus Christ, that our conversion and that of many others don’t have this basis; they are the result neither of dialectic, nor of syllogism. Are they therefore less profound, less solid? Time will tell, and it has already done so. Let [the critics] cite a single one of these conversions that has been withdrawn over the past ten years! And this despite, we must say it, very difficult circumstances. It is no thanks to our adversaries that our faith has not been scandalized, our zeal discouraged, our charity dulled.”80 The rapid rise of Bautain and his disciples to positions of authority in the diocese had produced a wave of jealousy and resentment from the majority of the clergy. Accusations directed against the Bautain circle echoed traditional attacks targeting the stubbornness and pride of Jews. “We were accused,” wrote Bautain,” of being proud, of wanting to distinguish ourselves.”81 In the face of this hostility built on the Jewish origins of Bautain’s disciples, Ratisbonne identified himself and his friends as “descendants of Abraham,” a label that recalls the earlier efforts of the Bautain circle to reach out toward Judaism. Conversion and ordination had not been sufficient fully to efface Ratisbonne’s Jewish identity, which emerged in the context of a debate involving the status of reason in Catholicism and the persistence of Jewish traits even after baptism.

Ratisbonne was also deeply resented by many Jews, and his family apparently suffered insults as a result of his conversion. But despite the pain he caused his family, and in the face of proselytizing behavior that they found insulting, Théodore Ratisbonne still managed to maintain ties with his relatives. His father apparently set the stage for this sustained relationship by refusing to disown him, which led Théodore to thank him publicly for “his noble and truly paternal conduct” in a letter published just after the public controversy over his baptism in 1828.82 Théodore was able to visit his father on his deathbed, a meeting that produced a painful confrontation when some relatives accused him of pressuring Auguste Ratisbonne to convert.83 Théodore was present again at the death of one of his nephews in 1840 and once again angered his family, particularly his brother Alphonse, when he expressed a desire to baptize the child. But as we saw at the start of this chapter, Alphonse’s antagonism toward Théodore and Catholicism in general changed dramatically in January 1842, at the church of Sant’Andrea della Fratte in Rome.

Alphonse Ratisbonne’s “conversion” took his family entirely by surprise, and in the weeks following this event his Jewish relatives reacted with a combination of disbelief and horror as they mobilized their efforts to dissuade him. Within two days of his conversion Alphonse wrote directly to his fiancée, Flore, as well as to his uncle Louis, describing his miraculous conversion and proposing that Flore join him as a Catholic so that their marriage might take place as planned. If she refused, Alphonse felt obliged to withdraw from the proposed union and announced that in such a case he would join a monastery and live a life of contemplation and prayer. In his letters Alphonse insisted that he was not insane and that he continued to love Flore and his family: “As for the affections of my heart, my love for Flore, who could doubt them? What young man has, more than I, lived so much with his family? Which of them has caused fewer concerns? Who is the beloved son, the favored nephew, the dearest uncle?”84 Ratisbonne here insisted on his family connection, even while affirming his new religious identity, but the gap between family and religion was clearly painful for everyone involved in this family crisis.

Louis Ratisbonne, Alphonse’s uncle, took the lead in the family’s response to the shocking news, insisting that his nephew leave Rome for Paris, where it was believed he would recover his senses, and his Jewish identity.85 In February Flore joined the battle over Alphonse’s religious identity with an impassioned letter to him in which she tried to shame him into returning to his Jewish family: “You’ve left the humble and the weak to go over to the proud and the powerful! What could have led you to such a sudden and unconsidered decision? Weren’t you happy in the religion of your fathers? And although a Jew, wasn’t the esteem of everyone compensation for your noble conduct?”86 The family tried cajolery as well to win Alphonse back and emphasized the pain he was causing to those he loved. All of these efforts failed, for when Alphonse traveled to Paris in early March he was welcomed by his brother Théodore into an intensely devout Catholic milieu and spent little time with his sister Pauline and her family, who were hoping to lead him back to the Jewish side of the family. During this period he became particularly attached to the prominent Jesuit preacher Father Xavier de Ravignan, to whom he wrote letters that included intensely emotional and familial language: “Pray for your son; son through the ties of the blood of Our Lord Jesus Christ, and son through the unalterable tenderness and affection that his completely broken heart will hold for you forever.”87 By the end of the year Alphonse was in Toulouse, where he had enlisted as a novice in the Jesuits.

Alphonse claimed to have found a new father, but his reference to a broken heart (coeur tout déchiré) indicates that his family ties were still affecting him. Like his brother Théodore, Alphonse was unable to leave his family behind as he crossed the religious boundary between Judaism and Catholicism. He acknowledged the pain he caused his family and, as we saw at the opening of this chapter, he described the moments after his apparition as a terrible combination of joy in his own salvation and deep anxiety about the ultimate fate of his family. But Alphonse’s letters to his family in January also include a harder edge, combining professions of love with an aggressive, threatening tone: “Laugh, laugh, impious ones, but for each of you will come a solemn hour, where you will no longer laugh, where you will think seriously about what I tell you today.”88 Alphonse’s choice of words here is telling, for no one in the Ratisbonne family was laughing. But he seems to have found it easier to face his own decision to remain a Catholic by articulating a standard critique of the disdainful Jew who resists the obvious religious truth of Catholicism, an idea that may have been lurking somewhere in his mind well before the dramatic events at Rome. Both Théodore and Alphonse Ratisbonne were intimately involved with both their Jewish family and the increasingly organized Jewish community. Théodore Ratisbonne was a founder of one of the principal Jewish charitable organizations in Strasbourg, the same group to which Alphonse became devoted in the 1830s.89 Both were inspired by a sense of family honor as well, expressing pride in their ancestors for their role in advocating Jewish rights, and in their relatives for their commitment to the family and the community. Théodore Ratisbonne’s long struggle in the 1820s, when he sought to live as “a Christian on the inside, a Jew in my family” was a religious crisis, but at the same time an attempt to avoid the dishonor that struck both him and his family when he announced his conversion. Théodore was caught in a web of competing and inconsistent value systems. His Jewish family, and Catholics generally, emphasized family religious identity as the basis of moral life and social harmony. But both Jews and Catholics also appreciated the value of religious liberty, which freed Jews from the political and civil disabilities of the Old Regime, and gave Catholics a means for approving an individual choice to leave family behind and convert.

All of these tensions were still in play in 1842, when Alphonse Ratisbonne converted, but by then both Jews and Catholics had become increasingly self-conscious of the consequences of religious liberty, an individual right they accepted in principle even while they feared its potential for disrupting families. With this tension in mind, if we look again at the conversion of Alphonse Ratisbonne, we can see how the miraculous apparition that overwhelmed him also managed to address and resolve this dilemma. On the one hand, Alphonse Ratisbonne was clearly an agent in his own conversion: he chose to go to Rome, to wear the “Miraculous Medal,” and to say the “Memorare,” and after Mary appeared to him he resisted the appeals of his uncle and his fiancée to return to his former life. It is worth noting that Théodore de Bussières also introduced Ratisbonne to two Jesuits in the days just before his conversion. Fathers Villefort and Rozaven joined the effort of Bussières to convert Ratisbonne, a detail that was suppressed in the publicity on the conversions, presumably to further emphasize its miraculous instantaneity. Nonetheless, Alphonse was not converted, like David Drach and his brother Théodore, as a result of an extended religious quest based on study and prayer; he was struck down, like Paul on the road to Damascus, and insisted that fifteen minutes before his conversion he had not the slightest impulse to become a Catholic. From our contemporary perspective, this claim might seem disingenuous, but for Alphonse Ratisbonne and his Catholic readers, a miraculous conversion avoided the extended preparations, apparent duplicity, and willful betrayal that a more gradual and intentional conversion entailed, as exemplified in the conversions of Théodore Ratisbonne and David Drach. The sudden blast of God’s grace, manifested in an apparition of Mary, that converted Alphonse Ratisbonne still left him with a complicated family negotiation, but through it all he was able to insist that in the end he had no choice in the matter, that it was God’s will and not his own that led him to Catholicism.

The Jewish members of the Ratisbonne family were, like Alphonse himself, torn between their anger, their continued affection, and their desire to see family harmony somehow maintained. With Alphonse, as with Théodore fifteen years earlier, conversion did not mark an absolute and permanent rupture in the family as it did with the Drachs. By early March Flore and the other Ratisbonnes conceded defeat, forgave Alphonse, and vowed to continue loving him as a family member. Flore’s letter of March 6 bluntly refused any possibility of her conversion and accepted that the marriage would not take place but insisted that she would still love her uncle and former fiancé as a brother: “You can’t marry unless I become a Catholic. Well, Alphonse, you must renounce me, because it is something that will never happen. Our union seems to me all the more impossible as I am sure that my mother in heaven would not bless it. Henceforth, I regard you and love you as a brother. Be happy, a Jewess knows how to forgive.”90 Flore kept her word, and despite his eventual ordination and work to convert Jews, Alphonse remained in touch with her and his family. Following Flore’s marriage to Alexandre Singer in 1846, he was a frequent and welcome visitor to her home in Paris in the 1850s and 1860s.91

Théodore Ratisbonne also struggled to reconcile his love for his family with his new faith, which divided them in the here and now, and more seriously from his perspective, in the afterlife as well. During a preaching tour that brought him to Strasbourg in 1845, he was apprehensive that his family would be hostile, but despite some tension he was able to meet on friendly terms with his brother Achille and a nephew.92 Théodore’s difficulty in accepting the possibility of eternal separation shows up clearly in sermons he delivered at the church of St. Philippe de Roule in 1847. In preaching on the theme of Catholic unity Ratisbonne took up the traditional doctrine that “out of the Church there is no salvation.” Ratisbonne struggled with this idea, which led him to equivocate, as he first affirmed it as dogma and then asked his audience to reserve judgment about the ultimate fate of nonbelievers: “And if God, in his infinite goodness, wishes to revive them in eternal life, by ways unknown to us, is it not natural to assume that they might live outside the ordinary conditions for salvation in this world?” Ratisbonne was unable to imagine the eternal condemnation of people, some of them his own relations, whom he knew to be “noble and beautiful souls, magnificent minds, superior spirits.”93 The complicated feelings of Théodore Ratisbonne toward the Jews he left behind can be seen as well in his attachment to the words spoken by Christ on the cross, just before he died: “Father forgive them, for they know not what they do” (Luke 23:34). This appeal is a central element in the prayers Ratisbonne wrote for the sisters of Notre Dame de Sion and their students, whose recitation of it affirmed the traditional accusation of deicide directed against the Jews.94 But it also opened up the possibility of forgiveness and redemption. The Ratisbonne brothers were deeply committed Catholics who became key figures in the church’s efforts to convert Jews, but they also tried, with some success, to maintain their relations with their Jewish families, to reach out across a border they could not efface. The supposed conversion of Lazare Terquem in 1845 demonstrates how difficult it could be to negotiate family relations across this religious border.

Our Lady of Sion and the Terquem Affair

Alphonse Ratisbonne’s conversion was the immediate incentive for the foundation of the Congregation of Our Lady of Sion, which established itself at the center of the Catholic campaign to convert Jews in the 1840s, an initiative favored by Rome and supported by Catholic elites in Paris and Strasbourg. Inspired by his brother’s miraculous conversion, Théodore Ratisbonne traveled to Rome in June 1842 with the abbé Dufriche-Desgenettes, the curé of the parish of Notre-Dame-des-Victoires, to seek approval to lead a mission to convert the Jews. Encouraged by Pope Gregory XVI and his secretary of state, Cardinal Lambruschini, Théodore returned to Paris and took up his work with passion, and considerable success. Théodore’s description of the early days of this new mission suggests a climate of emotional and spiritual fervor, with Catholic aristocratic women gathering at an orphanage run by the Sisters of Charity, to fuss over and celebrate the Jewish neophytes.95 By 1843 Théodore, with the help of Sophie Stouhlen, a pious woman from Strasbourg, had organized a small group of women into the Congregation of Our Lady of Sion, who were caring for eleven Jewish orphan girls by the end of the year. By 1845 the congregation had grown enough to purchase its own building on the rue du Regard, where it established a school that brought together the daughters of a Catholic elite and Jewish orphans.96

The self-confidence and aggressive proselytism of the congregation were publicly on display at the bedside of Dr. Lazare Terquem, and in the papers that reported on his death in February 1845. Terquem was a well-respected Jewish physician, originally from Metz, known for his efforts to reform the rite of circumcision in order to make it less painful, and for his work on the governing board of the rabbinic school at Metz.97 Although Terquem’s prosperity and success might have earned him a peaceful end, his final days were in fact deeply troubled, as family members battled over his religious identity in a dispute that drew the attention of the French press and eventually involved the grand rabbi of France, the archbishop of Paris, and the minister of justice. We have to struggle to hear Lazare’s own voice amid the arguments in his apartment, in the newspapers, and in the offices of religious and government officials, but in making this effort we can probe more deeply into the paradoxical situation of the post-revolutionary era, in which religious liberty was both increasingly affirmed in law and constrained by the tightening of confessional boundaries.

Catholic and Jewish relatives of Lazare Terquem disagreed sharply about what happened in his apartment on February 15, 1845, but some basic facts were accepted by everyone. On that Saturday Olry Terquem came to his brother’s house concerned about Lazare’s illness, and about the pressure his Catholic wife and daughters might exert on him as he neared death. There he found several family members gathered, including Lazare’s wife, two of their four daughters, their only son, a brother-in-law, and two sisters-in-law. The family members were equally divided between Catholic converts (the wife, the daughters, and the brother-in-law) and those who remained Jews (Olry, the son, and two sisters-in-law). The family was not alone, however, as it faced the death of Dr. Terquem. Also present at the invitation of his wife were Dr. Récamier, a Catholic physician, Father Théodore Ratisbonne, and several Catholic women, including Sophie Stahlen, the superior of the Congregation of Our Lady of Sion.

This cast of characters was clearly weighted in favor of the Catholics, but Olry Terquem was determined that his brother not be pressured to convert in his dying moments. Fearing just this, Olry talked with Ratisbonne and thought he took from this conversation a promise that his brother would be left to die in peace. But sometime during this same morning Ratisbonne entered the bedroom and, in the presence of eight Catholic women, including Lazare’s wife, baptized the moribund physician. Two days later, when the grand rabbi of France, Marchand Ennery, came to the apartment to take possession of the body and provide a Jewish funeral service, he was turned away by Terquem’s brother-in-law. Despite the grand rabbi’s protests, Lazare Terquem was buried as a Catholic.

In the days following Terquem’s death and burial Paris newspapers presented very different versions of these events. Drawing on the testimony of Olry Terquem, Le National, Le Constitutionnel, and the Archives Israélites insisted that Lazare Terquem was unconscious and therefore unable to make a reasoned choice about his baptism. In these accounts, Ratisbonne had behaved dishonestly and dishonorably, lying to Olry Terquem and violating the conscience of a dying man. The leading Catholic paper, Louis Veuillot’s L’Univers, responded that Ratisbonne’s promise to let Lazare die in peace was given after the baptism had already occurred, a promise that was kept.98 Despite these different versions of the events, I do not assume that either Théodore Ratisbonne or Olry Terquem was dishonest in their claims and counterclaims about what happened in Lazare’s home. It is easy to imagine both using selective recall and emphasizing some comments and gestures over others in order to justify their respective positions. Nor do I assume that we can know with any certainty what was going on in the mind of Lazare Terquem, whether or not as he faced death he chose Christianity, and if so, what his motives might have been. Perhaps he chose to make his death and funeral an easy matter for his wife and daughters; perhaps he was finally persuaded that his salvation was at stake. And perhaps his brother was right to claim he never recovered consciousness sufficiently to make anything like an informed decision. It is precisely the uncertainty of his religious identity and the profound anxieties this provoked in those around him that make his case worth pondering. As with David Drach and Théodore and Alphonse Ratisbonne, the story of Lazare Terquem shows us religious communities responding to conversion with mutual hostility, even while nervously accepting the conditions of liberal society that valued individual choice. But the Terquem affair illuminates as well the inner turbulence of troubled people undecided about their religious commitments and caught between communities that insisted on their exclusive claims over their identities.

As he faced death in February 1845 did Lazare Terquem wish to become a Christian, or did he retain a Jewish identity? This was the question at the heart of the dispute between Olry Terquem and Théodore Ratisbonne, and their allies. But as in the case of Théodore Ratisbonne, putting the question so bluntly oversimplifies the confusing and complex religious identities available in a French society in which people were experimenting with their newly won religious liberty. To judge by the testimony of Ratisbonne and Terquem, Lazare was deeply conflicted, drawn simultaneously to the Judaism of his family and community and to the Christianity adopted by his wife. Olry insisted, for example, that his brother expressed to him on several occasions his “lively attachment to the dogma of Israel, and a great antipathy against the dogmas, ceremonies, and liturgy of the Catholics.”99 As was the case with many Jews from the upper class in this period, Lazare no longer followed Jewish law with any rigor, but he attended services at Yom Kippur and always recited the kaddish on the anniversary of the death of his parents.100 Ratisbonne countered that Terquem “had several conversations with me in which he told me of his profound aversion to modern Judaism.”101 Both Ratisbonne and Olry Terquem assumed that the other was lying, but it seems equally plausible to take both men at their word, and to see Lazare as wavering and undecided about his religious beliefs and commitments.

The behavior of Lazare Terquem at the Catholic wedding of his daughter reveals him as conflicted in his religious identity but also opens up the question of Olry’s attitude toward Catholicism, which was similarly complex. Olry Terquem first raised the issue of the wedding when he reported in his letter to the Central Consistory, subsequently published in the Archives Israélites, that Lazare had not walked his daughter down the aisle to the altar on the day of her Catholic wedding because he refused to present himself before the crucifix. But Ratisbonne responded that both Lazare and Olry were present at the ceremony in the parish of Saint-Sulpice, where he observed the two of them on their knees. In the ongoing public exchange Olry then acknowledged that his brother was at the church but distinguished this from leading his daughter to the altar, and thus overtly participating in a Catholic ritual. But to make the situation even more complicated, Olry also acknowledged that he himself had in fact escorted Mlle Terquem to the altar, where she was married by none other than Théodore Ratisbonne. Olry claimed that he was able to present himself before the altar, and the crucifix, because he had a “profound indifference for signs,” but he insisted at the same time, and paradoxically, that he had never, at the wedding or at any other time, knelt before any image.102

The wedding of Terquem’s daughter at Saint-Sulpice, like the deathbed scene in the Terquem apartment, allows us to observe closely the painful negotiations Jews and Catholics were engaged in during this period when social integration, conversions, and mixed marriages were increasingly troublesome. Lazare would go to his daughter’s wedding but not lead her down the aisle; Olry was willing to do both but insisted that he would never kneel before a crucifix. These gestures reveal numerous and subtly different levels of cooperation in a Catholic ceremony, as the Terquem brothers sought to participate while still retaining some distance and insisting that such participation was compatible with Jewish identity.

In the course of the exchange between Théodore Ratisbonne and Olry Terquem the latter’s complicated relationship with Catholicism became increasingly evident, for Ratisbonne revealed that Olry’s wife had also converted, and that his children were being raised as Catholics. Olry’s ambiguous position is evident as well in the pamphlets he wrote during this period, when he was a leading advocate for radical reform in the Jewish community and called for the coordination of the Catholic and Jewish calendars and practices that would result in a “fusion” of the two religions.103 In a pamphlet published in 1836 Terquem asked a question that clearly reflected his own personal situation. What should a father of a Jewish family do, he wondered, if he judged that “in the course of centuries, the old cult, poorly understood, has become false, antirational, antinational, antisocial, if he sees that the religious destiny of his community is confided to men who are ignorant, presumptuous, selfish, frivolous, epicurean, impious. . . . If then such a father of the family exists, wouldn’t he show himself eminently religious, an excellent Israelite, in having his children baptized?” It is worth noting that Terquem was careful to make his point conditionally, another case in which a linguistic device is employed to create at least some distance from a forthright appeal for conversion. There is no such hesitancy in the response of the Jewish patriarch who is asked this question, and who responds cynically, “Abomination of abominations! Our children must persevere in the religion of our fathers, in which however I do not believe.”104