2. Religious Wandering in French Romantic Culture

Messieurs, je vous proteste

Que j’ai bien du Malheur,

Jamais je ne m’arrête,

Ni ici, ni ailleurs;

Par beau ou mauvais temps,

Je marche incessamment.

(Gentlemen, I swear to you

That I am truly unhappy,

For never can I rest,

Neither here, nor there;

In good or bad weather,

I walk and never stop.)

—“Le vrai portrait du Juif-Errant”

The Wandering Jew returned to France in the late eighteenth century, but he was not alone. He was accompanied by other religious wanderers, similarly perplexed about their religious identities. The Wandering Jew and his colleagues were prominent in the pages of some of the most important literary and theatrical works in the age of romanticism, testifying to the importance of their stories for French audiences anxious about the religious freedom newly available to them in the aftermath of the French Revolution. The converts we will meet starting in the next chapter lived within a culture that provided them with fictional characters who struggled, like themselves, to reconcile individual belief and romantic yearnings with family and communal solidarity. Religious liberty was now protected by French law, but how would it be thought about and felt by individuals as they explored recently opened religious borderlands? In this chapter I will probe a series of texts, some of them familiar, some less so, that answer this question through tales of religious wandering that were at the heart of French romanticism. Presented in a variety of genres and directed at diverse audiences, these stories reveal an intense emotional atmosphere and a paradoxical understanding of religious liberty, which is embraced as an individual right but also shown to have tragic consequences for individuals and their families.

The Wandering Jew Returns

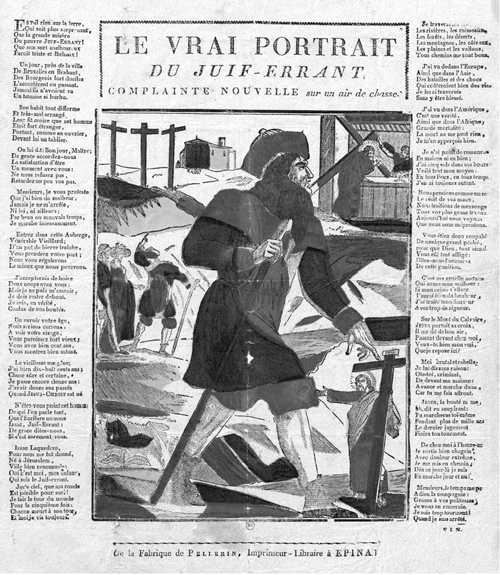

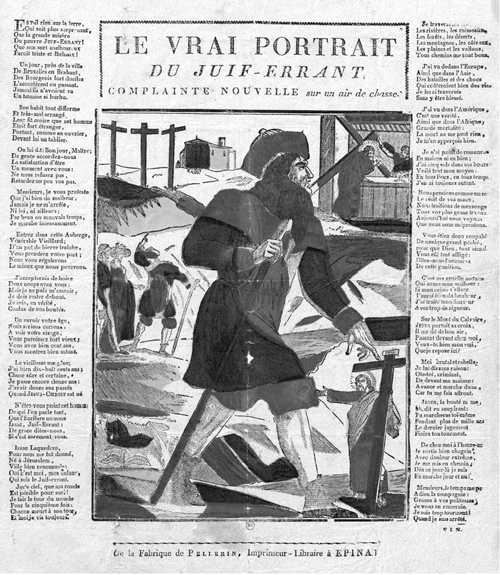

The Wandering Jew was sighted in Paris in 1773, in Brussels in 1774, and in Avignon in 1784. This, at least, is what we are told on the broadsheets announcing the news, illustrated with an old man, bedraggled, supported by a staff, and surrounded by images of Christ’s passion and a rhymed narrative known as a complainte in which he tells his lamentable story of eighteen hundred years of wandering (figure 4). The return of the Wandering Jew was greeted with an unprecedented outburst of publications, with at least two million and perhaps as many as ten million copies of the broadsheet telling his story in circulation in the early years of the nineteenth century.1 Although he began his career as a ubiquitous figure on a single sheet of paper, the Wandering Jew soon found his way into the pages of novels and poems and onto the stage of the French Grand Opera. During this journey the Wandering Jew encountered contemporary political and social issues that complicated the meaning of his tale, but he remained always a figure doomed to wander in the borderland between Judaism and Christianity. Ron Schechter has argued that the ambiguous social status of Jews in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries made them a useful symbol for the French, as they “facilitated the conceptualization and articulation of a number of ideas that were of special importance to their contemporaries.”2 I would build on this insight by suggesting that during this same period and into the nineteenth century the Wandering Jew became a crucial symbol through which the French could contemplate the possibilities and anxieties that accompanied the constitutional right of religious liberty.

The Wandering Jew had visited France before, to judge by pamphlets and broadsheets that began circulating in large numbers in the early seventeenth century.3 Literary scholars have traced his legend to Latin chronicles of the early thirteenth century, when the Benedictine monk Matthew Paris wrote of a man condemned to roam the earth until the end of time for having insulted Jesus at the time of his passion and death.4 The story evolved over the centuries, adapted by authors, most of them anonymous, for a variety of religious and social purposes. At a fundamental level the tale of the Wandering Jew provided eyewitness testimony to the truths of sacred scripture and an example of God’s justice, but also his mercy, in dealing with those who rejected his son. The tale could also serve as an explanation of the special status of Jews in Christian Europe, perceived as a marginal and rootless people condemned for turning their backs on their promised Messiah.5 These older meanings did not disappear and are clearly imbedded in the complaintes that circulated so widely throughout this period. But as he moved into other literary fields the Wandering Jew acquired psychological depth, a concern for family solidarity, and an interest in contemporary social issues, themes we will see echoing in the conversions of the Ratisbonnes, Ivan Gagarin, Félicité Lamennais, George Sand, and Ernest Renan.

Figure 4. “Le vrai portrait du Juif-Errant.” Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The most widely distributed complainte from the late eighteenth century was based on a supposed visit of the Wandering Jew to Brussels in 1774.6 Named Isaac Laquedem in this account, he speaks in his own voice for the first time, following a meeting with two bourgeois who offer him a drink and listen to his tale of woe. Laquedem is clearly a man to be pitied, whose great age, long beard, and disheveled clothes suggest a hard existence of poverty and exhaustion. When asked what sin he committed that would warrant his fate, Laquedem acknowledges that it was his own cruelty in refusing to let Jesus stop and rest on his path to Calvary. Jesus, described as “goodness itself,” delivered his sentence with a sigh: “You will march for more than a thousand years. Your torment will end with the Last Judgment.”7 Although the complainte stops short of announcing the redemption of Laquedem, it implies nonetheless that his punishment will be expiatory, that in the end he will be saved. Laquedem has not been baptized and is still a Jew, but he is also someone who has witnessed the Passion of Christ and acknowledges its central role in human history. He is a poor Jew sentenced to wander the earth, but also a Christian missionary, an eyewitness spreading the story of Jesus’s Passion to the world.

The Wandering Jew as presented in the complaintes was an object of pity, but he was also guilty and helpless, rightfully condemned to march until the end of time. In the late 1790s his character underwent a major change, becoming more sympathetic and acquiring supernatural powers that he used to protect families and their fortunes from rapacious and satanic figures. This heroic version of the Wandering Jew was first presented in Matthew Lewis’s influential gothic novel The Monk. Published in 1796, The Monk was quickly translated into French and became the basis for a number of dramatizations on the French stage.8 In Lewis’s work the Wandering Jew is an exorcist who saves the young hero Raymond from a vampire-ghost, thus assisting him in his goal of marrying the beautiful Agnes. In stage adaptations of Lewis’s novel playwrights adopted his convention of presenting the Wandering Jew with a cross emblazoned on his forehead, confirming his ambiguous religious status, even while he assumes a role as a potent and self-conscious actor in human affairs. Louis-Charles Caigniez, known as the “Racine of the boulevards” for his appeal to a broad popular audience, had a huge success with Le Juif Errant, produced at the Théâtre de la Gaité in 1812. With Caigniez the myth of the Wandering Jew took on “artistic forms particularly valued in France, the popular novel, melodrama, spectacular effects, and vaudeville.”9 Caigniez continued the tradition of Lewis in portraying the Wandering Jew as a protector of families, in this case the Algunars of fifteenth-century Spain, who are saved from a rapacious neighbor, which in turn allows the happy marriages of Theresina and Félix d’Alguna.10 The Wandering Jew’s commitment to family reaches a new level with Le Juif Errant of Pierre Merville and Julien de Mallian, produced at the Théâtre de l’Ambigu-Comique in 1834, for in this work the Wandering Jew’s mother and wife assume roles in the story. The play was a huge success based in part on its spectacular sets and special effects, on display from the opening scene of the Crucifixion to the concluding Last Judgment.11 These effects serve a story that opens with Isaac Laquedem, a shoemaker of Jerusalem, living in joy and harmony with his elderly mother, his wife, Noéma, and his daughter Esther. This idyllic life ends with Isaac’s indifference to Jesus’s appeal for help, but in this version his daughter is also condemned to wander. Isaac, however, is granted the power to raise his daughter from the dead, a gift he is forced to use several times over the centuries. In the final act he bargains with the devil for the soul of his daughter, and both are finally saved through the intervention of Michael the Archangel. As the Wandering Jew traveled from broadsheets to the Paris stage, he became a heroic figure, a deus ex machina who overcame impediments to happy marriages and saved family fortunes. He had retained his ambiguous religious status as a Jew whose endless journey testified to the truths of Christianity, but he was now someone to be looked on with awe and gratitude as well as pity, and whose redemption could be more clearly foreseen. These traits explain why George Sand, in the midst of her spiritual crisis that we will explore in chapter 6, cast herself in the role of “wandering Jew” as she pondered her religious identity in 1835.12

The heroic qualities of the Wandering Jew on display in the 1830s were accompanied by a new youthfulness, for he was presented at times as a vigorous man in his thirties rather than a decrepit pilgrim. In Ary Scheffer’s portrait of Ahasvérus (1833–1834), the Wandering Jew takes on Christ-like features as a bearded young man, troubled and thoughtful.13 The sympathetic portrayal of the Wandering Jew reaches its climax with Eugène Sue’s novel The Wandering Jew (Le Juif Errant), first serialized in Le Constitutionnel in 1844–1845.14 This title is somewhat misleading, since this work revolves not around the story of the Wandering Jew but around the machinations of the Jesuits to defraud a Protestant family, the Renneponts, of their rightful inheritance. But the figures of the Jew and of his female counterpart and sister, Herodias, the wife of Herod who had asked for the head of John the Baptist, play crucial roles nonetheless. Sue’s novel builds on the theme of family solidarity already evoked in the earlier adaptations of the tale, but in his version the Wandering Jew also becomes a spokesman for justice and equality, a critic of religious intolerance and rigid orthodoxy, and a defender of religious liberty.

Sue opens his novel with a poignant scene that emphasizes the importance of family feeling, as the Wandering Jew and Herodias greet each other across the Bering Strait, allowed only this contact because of their crimes. From this point Sue follows the lives of the seven surviving members of the Rennepont family, whose social origins range from the aristocracy to the working class. Mysterious messages draw the family toward Paris for a meeting on February 13, 1832, when the will of their ancestor, Marius de Rennepont, is to be executed, providing for the equal division of an enormous fortune left to the care of a loyal Jewish family. The Wandering Jew and his sister, distant progenitors of the family, appear miraculously throughout the novel to save their descendants from death and prison, helping them to reach Paris despite the sinister attempts of the Jesuits to stop them. In the end the Jesuits do succeed in arranging for the deaths of six of the family, but they fail to acquire the family wealth when the Jewish banker charged with managing the inheritance burns all the papers associated with it. The Wandering Jew and Herodias, no longer needed by their descendants, age and die, looking forward to a family reunion in a better world.15

Sue’s Wandering Jew was a publishing blockbuster; avidly followed by readers of Le Constitutionnel for over a year, it pushed subscriptions from thirty-six hundred to twenty thousand and won for Sue the astronomical fee of 100,000 francs.16 The success of The Wandering Jew owes much to its topicality, as Sue’s assault on the Jesuits echoed the recent work of Edgar Quinet and Jules Michelet.17 The novel also confirmed and expanded the popular appeal of feuilletons, serialized novels that ran at the bottom of the first page of newspapers, a form that relied on exotic settings, melodramatic incident, and a moralistic framework in which good and evil were defined with no ambiguity whatsoever. Sue’s passionate commitment to the working class, derived from the utopian socialism of Charles Fourier, already on display in Les mystères de Paris (1842–43), also helps explain his work’s popular appeal. Frequently reprinted and dramatized, Sue’s Wandering Jew became the basis for retelling the story of the Wandering Jew throughout the rest of the century.18

Sue’s novel is a bewildering work, with dozens of characters and subplots, all of them presented within the overarching drama that divides the perfectly malevolent Jesuits, led by the vile Rodin, from the Renneponts and their long-lived Jewish protectors. From my perspective the novel is especially valuable because of its critique of conversion as a violation of family solidarity. In the course of the novel the family feeling that links the Wandering Jew, Herodias, and the Renneponts over eighteen centuries is elevated as a supreme value, challenged by the Jesuits, who repeatedly seek to undermine the family’s love and loyalty toward each other. For Sue, religious conversion that threatens family ties is the result of crass self-interest and insidious manipulation of religious sentiment. Madame de Saint-Dizier, for example, the chief co-conspirator with the Jesuits, is an aristocratic viper who as a young woman lived a life of dissipation and political intrigue, accumulating lovers and working to undermine the Napoleonic empire. Only when her beauty has faded does she adopt an ostentatious but thoroughly hypocritical attachment to Catholicism, which allows her to establish a salon where she can continue her political intrigues.19 François Hardy, a manufacturer who runs his factory according to Fourierist principles and one of the Rennepont survivors, converts to Catholicism only after he has been isolated by the Jesuits in one of their residences. This apartment, which Hardy believes is offered in good faith, is in fact part of a complicated plot that involves destroying his factory and conspiring to end his passionate love affair with a young woman. Constantly surrounded by gloomy religious messages that disparage this world, Hardy is finally convinced by the “deplorable mystic jargon” of the Jesuits to leave Paris and “devote himself to a life of prayer and ascetic austerities.” Hardy’s conversion leads him to cede his portion of the inheritance to the Jesuits before he dies, an example of how the order despoils families.20

The religious principles of Sue’s Wandering Jew, in the portrayal of the title character and of those who side with the Renneponts, are based on toleration of religious difference and a commitment to human solidarity that transcends class and sectarian divisions. Such values are contrary to attempts to proselytize, a point Sue makes clear in reporting an incident involving Gabriel Rennepont, a family member coerced by the Jesuits into a vocation that is repugnant to him. Gabriel is regarded with great suspicion by his Jesuit colleagues, in part because he took into his home a poor Protestant, refused to try to convert him, and then buried him in consecrated ground.21 Such behavior, leaving an individual free to follow his own conscience without undue pressure, made no sense to the Jesuits but is at the heart of Sue’s understanding of religious liberty. In defending this principle Sue was repeating in the form of a popular novel a regard for the rights of individual conscience that can be traced to the philosophical debates and religious conflicts of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as we saw in the last chapter.

Sue was not the only reform-minded author to cast the Wandering Jew as a tragic figure whose story could be used to support an agenda of progressive social change. Pierre de Béranger, the most popular songwriter of the 1820s and 1830s, narrates the same basic story told in the popular complainte in his adaptation of 1831. But in the last verse the Wandering Jew declares that the sin for which he was punished was his indifference to Christ as a man, not as a divine figure: “It is not his divinity but his humanity that God avenges.”22 Béranger’s song and Sue’s novel attest to the continuing appeal of the story, even as its meaning shifted to emphasize a humanitarian message. Not all versions of the tale of the Wandering Jew were as high-minded as those of Sue and Béranger; at times his heroic behavior was subject to parody, and his story also offered an occasion for setting off spectacular fireworks on stages, effects designed to accent his supernatural powers.23 In a clear response to Sue, the Catholic apologist and occultist writer Jacques Collin de Plancy presented Isaac Laquedem as a conniving figure attempting to restore the kingdom of Zion, using the Anabaptist rebels of Münster as tactical forces. In his epilogue de Plancy depicts the Jesuits as saviors whose emergence was necessary to counter the plot of the Wandering Jew.24 However he was viewed, the Wandering Jew served always as a symbol of religious difference and its potential consequences, of ambiguous religious identity, and of the isolation and trouble this could cause. And he could serve as well as a symbol of suffering humanity, whose troubled journey might someday lead to salvation.

For Edgar Quinet (1803–1875) the redemptive dimension of the Wandering Jew extended beyond a particular character and individual families to include all mankind. Better known today for his critique of the Catholic Church and his support of a republic, Quinet was also a prominent literary figure whose presentation of the Wandering Jew in his epic poem Ahasvérus drew substantial attention when parts of it appeared in the Revue des Deux Mondes in 1833, followed by its full publication a year later.25 Quinet first learned of the story by hearing the popular complainte being sung on the street, and it was the subject as well for his first publication, Les tablettes du Juif Errant (1822), in which Isaac Laquedem comments critically on the persistence of human folly, especially as manifested in the Middle Ages, so much in fashion with Catholics during the Restoration.26 In the ambitious and confusing epic from the 1830s the Wandering Jew, now with the name Ahasvérus, is at the center of a cosmic drama that traces human history from its origins through the Last Judgment. From the time of its appearance critics expressed both admiration for and reservations about the work. Charles Magnin, writing in the Revue des Deux Mondes, praised Quinet’s poem as a work of genius, an epic that might be compared to Dante’s Divine Comedy, but he feared that its obscurity and extravagance would put off critics and readers.27 Magnin’s judgment was correct, and Quinet’s Wandering Jew never achieved the status of masterpiece. But it was noticed at the time, as evident in Magnin’s essay, and in the responses of critics who were baffled by the complexity of its organization and by the hundreds of voices given parts in the drama, including various angels and saints, historical figures, cities, mountains, rivers, the ocean, and several godlike characters: “the Eternal Father,” “Eternity,” and Christ himself.28

Critics in particular targeted the sense of despair that informed human history as observed by Ahasvérus, a point summed up by A. Lebreu in the Revue des Deux Mondes of 1843, where he wrote that in this “strange drama . . . the entire universe is full of despair, and the heavens and the earth, with their fragile gods, all bound by the same fatality, end by disappearing into the voiceless night of nothingness.”29 Lebreu here is referring to the final scene of the epilogue, where Eternity has the final word; after sending Christ back to his tomb, he declares that there is neither being nor nothingness, there is only “MOI.” Quinet defended himself against the charge that this conclusion, along with many details in the poem, represents a view of human history as a meaningless journey. He insisted that he foresaw a redemptive outcome to history, mediated by a Christ who would be “greater, and risen to a level of human intelligence.”30 But there is no mistaking the terrifying doubt that is expressed at several points in the epic. A “Choir of Dead” in the Strasbourg cathedral insist to Ahasvérus that “Christ is not risen; he is no longer with us: I say to you one more time: there is no Christ.”31 Early in the fourth and last act, “The Last Judgment,” Ahasvérus surrenders for a time to despair, admitting that “Everything dies, everything disappears. Stars and heavens, all is undone; islands, capes, distant seas, all disappear, except for the moan in my chest, the tear in my eyes.”32

Religious doubt and despair are central to the character of Sue’s Ahasvérus, themes that recur in the journeys of all the converts in this study. But like Ahasvérus they find in their wandering a sense of personal fulfillment and social progress. Quinet responded to critics by insisting on the hopeful message of his version of the Wandering Jew, displayed when Ahasvérus, with a fallen angel Rachel at his side, faces Christ on Judgment Day. After announcing that he has achieved his task of gathering up all the pain of the world Ahasvérus is asked if he would like to return to his home. He refuses this offer of domestic security and instead asks “for life, not for rest,” and to be allowed to continue to voyage upward, through the stars, accompanied by Rachel. Pushed on by his hopes and desires, he aspires to go “further, always further.” Impressed by his determination, “the Eternal Father” announces to Jesus that Ahasvérus is the “eternal man” and that the time has come to create other, newer, and better worlds. Judgment Day then concludes with an extended hymn celebrating harmony and reconciliation, summed up by the “Lyre”: “Alleluia! Alleluia! No more death! No more war! No more tears! All suffering is consoled.”33

For all its excess and obscurity, Quinet’s Ahasvérus has earned a place as an important effort to imagine a new religion emerging in the wake of Christianity, what Paul Bénichou has termed the “religion of humanitarianism.” This attempt was appreciated by Magnin in his essay in the Revue des Deux Mondes and was at the center of an extended analysis written in 1841 by Paul Bataillard (1816–1894) and Eugène Fromentin (1820–1876), young men who were later to become significant literary figures in France.34 Fromentin and Bataillard establish a contrast between Quinet’s poem and the work of Pierre Ballanche, who also proposed a vision of world history in which human progress was achieved by a series of ordeals. But with Ballanche, God’s providential presence determines in the end the upward movement of history, with Christ playing a central and redemptive role; with Quinet, humanity as represented by Ahasvérus is on its own, and his story is one of emancipation from priestly control.35 There are other possible readings of Quinet’s poem, as Fromentin and Bataillard as well as modern commentators acknowledge. It could be taken as an exercise in heresy and nihilism, but also as a tribute to human endurance and an affirmation of universal progress. “It shows us beliefs in conflict, and frightening doubts: here an assertion, but then a brutal denial. One is moved by the birth and passion of Christ, struck by the Christian adoration of the Virgin Mary; and then the page turns, the idol is broken, the image evaporates: childish credulity! You were adoring a ghost!”36 In Quinet’s hands the Wandering Jew transcends his folkloric and theatrical representations to become a symbol for religious anguish and uncertainty, feelings common in an age of advancing religious liberty.

Even as he took on a heavier symbolic load, the Wandering Jew in Quinet’s epic also retained his human dimension as a member of a family that suffers as a result of his endless journey. In the scene that follows his first meeting with Christ Ahasvérus reflects on his happy home life with his father, sister, and two younger brothers. Nathan, the father, has high hopes for his eldest son and heir; his sister, Marthe, soothes him with her singing; and his two brothers, Elie and Joel, pester Ahasvérus to let them accompany him. To ease the pain of his departure Ahasvérus tells his father he will soon return, before he is driven off forever by Michael the Archangel.37 The family then disappears, showing up again only at the Last Judgment, where they express sorrow that Ahasvérus has been forced to wander alone, without his family.38 For Quinet the family tragedy plays only a small part in the story of the Wandering Jew. For other religious wanderers, on the stages of Paris and in the pages of popular novels, the pain of separation from their families was at the heart of their conversion experience.

To Convert or Not to Convert: Operatic Questionings

Given his broad appeal, it is not surprising that the Wandering Jew was able to mount the stage of the Paris Opera. Eugène Scribe and Fromental Halévy worked together to produce Le Juif Errant in 1852, a major effort whose budget ran to more than 80,000 francs to pay for the elaborate sets and the 782 costumes needed for the spectacle.39 Scribe’s libretto, drawing on Sue’s novel and Quinet’s prose poem, paints Ahasvérus as the savior of his family in twelfth-century Flanders; he intervenes to allow his descendants Irene and Léon to marry and oversees Irene’s recovery of her rightful position as the Countess of Flanders. In its operatic form Le Juif Errant was not a success. Although Giacomo Meyerbeer thought well enough of it to attend seven performances in 1852–53, Le Juif Errant fell from the repertoire after its first production.40 Halévy’s version was not helped by a mediocre score and a bewildering conclusion, in which Ahasvérus seems at first to have won death and redemption, only to have this judgment reversed in the final scene.41 But if it was not hospitable to the Wandering Jew, French opera was nonetheless fascinated by stories about characters who faced agonizing religious choices.

When grand opera emerged as a major cultural force in Paris in the 1830s, two of its most auspicious and enduring successes centered on decisions about whether or not to convert. La juive, with a text by Eugène Scribe and music by Fromental Halévy, was a triumph when it was first produced in 1835, and it sustained its appeal, performed over five hundred times in Paris during the nineteenth century.42 A year later Scribe achieved similar success when he collaborated with Meyerbeer to produce Les Huguenots.43 The opera in Paris in the 1830s emerged as an institution where the bourgeoisie and grands notables went to be entertained by elaborate spectacles and huge emotions, conveyed by soaring voices and the lush orchestration of romantic composers.44 The stories told at the opera were extravagant concoctions of conflicting family loyalties, romantic love, and bizarre coincidences. Eugène Scribe, the most popular playwright and librettist of the era, has been criticized by the opera scholar David Conway for creating a “parallel universe, in which colorful historical or geographical milieus display a handful of characters who, as a consequence of some secret maneuverings in their own pasts and coincidences in the present, are forced to face some implausible crisis of choice or conscience, preferably accompanied by a simultaneous natural disaster and violent death (or both).” But as Conway acknowledges, Scribe is also known for his ability to catch the public mood, and to represent it on the stage.45

Readers of the texts of La juive and Les Huguenots are likely to appreciate Conway’s caustic judgment, but they will also find in these operas a searching examination of religious liberty in the crises of choice and conscience that he dismisses so quickly. As Michel Espagne has proposed, for all their extravagance, these operas can be read as “expressing at a precise moment all the aspirations and fears of Parisian society.”46 Although it annoyed some critics for its unlikely plot, and others for its harsh depiction of Catholic intolerance, La juive was nonetheless a major success, a work that helped solidify the appeal of grand opera for the Paris audience.47 Fromental Halévy, the composer of La juive, and the more famous Giacomo Meyerbeer, the composer of Les Huguenots, were both assimilated Jews, well connected to the Parisian world they inhabited and enormously successful. But neither of them converted to Christianity, and both maintained a Jewish identity. Both wrote music for the synagogue as well as the stage and were targets of anti-Judaic barbs, most famously in the case of Meyerbeer, assaulted for his commercial instincts by Richard Wagner in his notorious essay Jewry in Music (1850).48 In La juive and Les Huguenots they present musical dramas that focus on the plight of religious minorities, with climactic scenes involving fraught decisions on whether or not to convert to the religion of the majority. These works reflect an acute awareness of religious identity derived from their own situation and the broader context of post-revolutionary France. Paris audiences were drawn to the romance, spectacle, and music of La juive and Les Huguenots, but these were used to tell stories centered on the anguished feelings of individuals and their families making religious choices, embodying on a grand scale the experience of religious liberty.

Although it fell out of the standard repertoire for a period early in the twentieth century, La juive has been revived recently, with major productions in Vienna (1999, 2015), New York (2003), and Paris (2007). This interest suggests the contemporary relevance of the themes of tolerance and religious liberty central to the work of Scribe and Halévy. These themes were relevant as well for the audiences that made La juive a triumph in 1835, and one of the most frequently performed operas throughout the nineteenth century.49 Set in Constance in 1414, where a church council was dealing with the Hussite rebellion, La juive centers on a tragic love between Rachel, the Jewish daughter of the jeweler Eléazar, and Prince Léopold, the husband of Princess Eudoxie, the daughter of the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund. The final major figure in the opera is Cardinal Brogni, the leading prelate at the council, who is in fact the real father of Rachel. Years earlier, while he was living in Rome and before his ordination and clerical career, Brogni’s wife and daughter had been killed by marauding Lombards, or so he believed. In fact, his daughter had been rescued by Eléazar, who raised her as his own child, as the cardinal learns too late in the tragic closing scene. Through a series of complicated plot developments, Rachel eventually learns that Léopold, who had deceived her by adopting a false identity as a Jewish apprentice named Samuel, is in reality a Catholic prince married to a daughter of the emperor. Driven by jealousy, she denounces him in public for his relationship with her, leading Cardinal Brogni to sentence Léopold/Samuel, Rachel, and her father, Eléazar, to be boiled alive.

Decisions about whether or not Jews should convert to Catholicism are at the center of the tragic conclusion to La juive. While awaiting death, Eléazar is approached by Cardinal Brogni and told that by accepting baptism he and Rachel could be saved. He rejects this offer, and then reveals to the cardinal that his daughter still lives, but refuses Brogni’s pleas for any information about her fate. This anguished confrontation sets the stage for act 5, in which an enormous boiling pot dominates the scene. As they contemplate their imminent death Eléazar, moved by the love of his daughter, finally relents and proposes to Rachel that she convert in order to save herself. She refuses, and their last exchange concludes with an acceptance of martyrdom and mutual assertions of confidence in each other and their God:

ELE´AZAR: Their God calls you!

RACHEL: And ours awaits me!

Together:

RACHEL: It is heaven that inspires me.

I choose death!

Yes, we embrace our martyrdom.

God opens his arms to us.

ELE´AZAR: It is heaven that inspires her.

I give you to death!

Come, we embrace our martyrdom.

God opens his arms to us.50

As Brogni makes one last plea for information about his daughter, Eléazar points to Rachel, shouting “La voilà!” as she is thrown into the pot, and then follows her to his death.

La juive is a rich and complex work of art, revived recently to emphasize its critique of antisemitism, clearly a theme intended by Halévy. But La juive can also be read as a tragic depiction of individuals struggling to reconcile feelings of love and loyalty toward their families and their religious communities with competing claims that drew them across traditional boundaries. In the most famous aria of the opera, “Rachel, quand le Seigneur,” Eléazar reflects on his responsibility as a father and a devout Jew and imagines Rachel appealing for her life, an anguished moment that concludes with his declaration “Rachel, you shall not die.”51 But as we have seen, in the final scene Rachel refuses his appeal that she convert, even though it means her death. Both father and daughter here confront the competing demands of their religion, family solidarity, and personal desire. In a concluding tragic irony, the patriarch grants his daughter the freedom to convert, but she chooses to exercise this freedom by remaining a Jew.

Just a year after the enormous success of La juive Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots raised again the issues of religious intolerance and violence and, like its predecessor, closed with a climactic scene again involving a decision of whether or not to convert. The plot of Les Huguenots is equally far-fetched, pushed along by mysterious visitors and overheard conversations. But the central drama emerges clearly, driven by the love between the Protestant nobleman Raoul and the Catholic noblewoman Valentine, the daughter of the Count of Saint-Bris, a zealous leader of the Catholic League. The scene is Paris in 1572, just before the marriage of the Protestant Henry of Navarre and the Catholic Princess Marguerite of Valois, the brother of the French king Charles IX. Marguerite encourages Raoul and Valentine to marry, hoping that such a union, like her own, will lead to religious reconciliation. But the jealous Raoul refuses, suspecting Valentine of infidelity. She marries instead the Catholic nobleman the Count of Nevers; Raoul, still in love and realizing he was wrong to suspect Valentine, finds his way to her room for a final meeting. When he hears men approaching he hides and overhears plans of the Catholic Leaguers to slaughter the Protestants. Resisting Valentine’s pleas to stay with her and save himself, Raoul rushes off to warn his friends. In the last act Valentine manages to find Raoul, fighting with his friends to defend a Protestant church where women have taken refuge as the Catholic forces approach. Valentine brings with her a white scarf, the symbol of the league, which will save him if he puts it on and agrees to convert. Raoul refuses to dishonor himself and chooses to stay with his dying friend, Marcel. Faced with this situation, Valentine decides to become a Protestant; her Catholic husband Nevers has been killed in the fighting, and Marcel agrees to bless their union as man and wife. The Catholic forces enter the church, demanding that the women who have taken refuge in the church “abjure or die”; Raoul, Valentine, Marcel, and the audience learn of their decision to become martyrs when their singing comes to an end. In the final scene Saint-Bris and his soldiers find the three survivors near the Seine and murder them when Valentine refuses to reveal herself to her father. Like Cardinal Brogni in La juive, Saint-Bris, driven by religious intolerance, has murdered his own daughter.

From one perspective the message of Les Huguenots is clear: attempts to force conversions by the use of violence are condemned, and the right of religious minorities to believe and practice freely is affirmed. Raoul’s behavior also carries with it a straightforward lesson. Like Rachel in La juive he is tempted to convert to save himself, and like her refusal his exemplifies sincere religious conviction and a commitment to the freedom of conscience, even at the cost of his life. Valentine’s behavior, however, provides a more complicated perspective on conversion, for she is moved primarily by her love for Raoul. She converts so that she can marry and die with him, not because of any strong commitment to Protestantism. But Valentine’s conversion is by no means a merely practical decision to facilitate her marriage to Raoul, who has been mortally wounded in the preceding battle. In choosing to convert she understands that he will soon die and that her own life will now be at risk as well. As she awaits her death with Raoul and Marcel, Valentine joins them in looking ahead to a heavenly reunion, inspired by the courage of the Protestant women, and listening to a heavenly chorus welcoming them to a better world. Valentine may be indifferent to dogmatic distinctions between Protestantism and Catholicism, which drive men to murderous attacks on each other. But she is a sincere Christian who rejects the significance of confessional differences, especially when they form an impediment to human love.

Intermarriage across religious lines was not just an imagined problem in the 1830s. In 1830 Pius VIII issued a papal brief, Litteris acerbo, which declared that mixed marriages were a violation of both divine and natural law.52 Gregory XVI renewed this charge with encyclicals in 1832 and 1841, provoking angry responses from the French liberal press, which viewed the prohibition as an attack on the freedom of conscience and contrary to Article 5’s guarantee of the liberty of cults.53 Negotiating the tension between religious differences and family solidarity was a complex and delicate task on display at the highest level of French society as well. When Louis-Philippe’s eldest son and heir to the throne married the Protestant Duchess Hélène of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, their marriage at the chateau of Fontainebleau was in the end blessed by both a Catholic bishop and a Lutheran minister, with the understanding that any children would be raised as Catholics.54 This mixed marriage involving the heir to the French throne recalls the similar union of the Protestant Elisabeth-Charlotte von der Pfalz, the Princess Palatine, to the Duc d’Orléans, the brother of Louis XIV, in 1671. But Elisabeth-Charlotte had to convert to Catholicism before the marriage could take place, which she agreed to even while she continued to identify with her Protestant family and to express standard criticisms of Catholic belief and practice.55 Two centuries later the Duchess Hélène was free to remain a Lutheran, an indication that some degree of personal religious liberty applied within the royal family, a reflection of the new attitudes that accompanied the constitutional changes that followed the French Revolution. But this marriage took place only after long and complex negotiations, reflecting the tension that arose when families and religions exerted their claims over individuals. We have seen these tensions displayed on the operatic stage; they were a central theme as well in some of the most important works published and presented in the early nineteenth century.

Love, Religion, and Liberty in French Romanticism

Chateaubriand’s Atala is universally regarded as a seminal text in the history of French romanticism. Published in 1801, the novella went through five editions in its first year and was transformed into plays and parodies, its characters presented in wax dolls and prints. Girodet’s painting of the burial of Atala was one of great successes in the Salon of 1808 and still hangs in the Louvre.56 Chateaubriand’s story appealed to readers on several levels, with an exotic setting, fulsome descriptions of the natural beauty of North America, a melodramatic love story, and an emotionally inflected endorsement of Catholicism. But at a fundamental level Atala tells the story of a religious conversion, and of religious liberty, with a plot driven by a tragic love that forces painful choices on its hero and heroine as they face each other across religious lines. This conflict between romantic yearning and religious commitment, which shaped the operas of Scribe, Halévy, and Meyerbeer, shows up as well in other works, which in some cases rivaled Chateaubriand’s novel, La juive, and Les Huguenots in their ability to draw a public. Taken together these works suggest the central importance of religious liberty for French audiences during the romantic era, fascinated by the tragic confrontation between individual belief and communal solidarity.

In Atala Chateaubriand builds his story around the love of the young warrior, the heathen Chactas, and Atala, the Christian daughter of a Muskogee chief. As a young warrior Chactas is captured by the hostile Muskogees and sentenced to death but is saved by the beautiful Atala. But the Christian Atala is prevented from marrying Chactas because he is a pagan, and because her mother swore her to perpetual virginity. This vow was made so that Atala would survive a childhood illness and was renewed and strengthened by Atala at her mother’s deathbed. Bound by her faith and maternal loyalty, Atala is torn apart because her vow conflicts with her deep love for Chactas. After she helps him escape, they find refuge in an idealized Catholic mission led by the wise and compassionate Father Aubry, who assures Atala that her oath can be rescinded, allowing Chactas and Atala to marry. But it is too late, for Atala learns of this tolerant form of Catholicism only after she has taken poison in despair. Before she dies, however, she asks of Chactas a promise to convert; he eventually dies as a Christian.

Atala’s identity in Chateaubriand’s novella is intimately linked to her faith and family. Loyalty to her mother and her Catholic faith obligate her to resist Chactas, for to give herself to him would violate her oath, made both to God and to her mother. Chateaubriand here establishes a pattern in which family loyalty merges with religious solidarity, values in conflict with the right of individual choice about religion and marriage. Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe works a variation on this theme in presenting a dramatic religious choice by the Jewish heroine Rebecca as one of its climactic moments toward the end of the novel, though in this case with no tragic outcome. Scott was an English writer, but Ivanhoe, like his other books, was enormously popular in France, with at least five editions appearing between 1821 and 1830. Considering Scott’s novel here reminds us that the questions about conversion and liberty were not confined to France but resonated throughout Europe.57 In the novel Rebecca is saved by Ivanhoe, who wins in a trial by combat against the evil Bois-Guilbert and thus prevents her from being executed as a sorceress, a false accusation leveled by the Knights Templar. Rowena, who has recently married Ivanhoe, implores Rebecca to stay in England and consider conversion: “O, remain with us; the counsel of holy men will wean you from your erring law, and I will be a sister to you.” Faced with this offer to convert, Rebecca responds unequivocally: “No lady. . . . That may not be. I may not change the faith of my fathers like a garment unsuited to the climate in which I seek to dwell.”58 Rowena’s attempt to convert Rebecca is a well-intentioned effort, not a nefarious plot as in Sue’s Wandering Jew, nor the threat to abjure or die directed at Jews and Protestants in La juive and Les Huguenots. Scott, through Rowena, has left Rebecca free to choose and presents her refusal as an admirable act of religious faith and family solidarity, recalling the values that Halévy emphasized in the conclusion of La juive, without the accompanying tragedy.

The popularity of Scott’s Ivanhoe spawned imitators in France, such as Alexandre Dumas, whose historical novels The Three Musketeers (1844) and The Count of Monte Cristo (1845) were enormously successful. But Scott’s portrayal of Rebecca, the beautiful and exotic Jewess heroine, also generated a response from Eugénie Foa, the earliest French-Jewish writer to experiment with the novel form. Foa was part of the Jewish elite who settled in Paris in the 1820s, a group that included the composer Fromental Halévy, who married Foa’s sister in 1842.59 As Maurice Samuels has pointed out, Jewish identity was at the center of her stories, “a problem to be struggled with, a series of questions to be answered.”60 In her novel La juive, published in the same year that Halévy’s opera had its premiere, Foa tells a similar story of a Jewish woman, Midiane, who falls in love with a Christian, André de Prezel. Such a relationship was illegal in the eighteenth-century and her patriarchal father, Schaoul, condemns it. Despite the paternal and social prohibition, Midiane and André run off together and have a child. In the end they die isolated and impoverished, but a daughter survives, to be raised by Schaoul’s two sisters, who grant her the right to marry either a Jew or a Christian.

In Foa’s novel the barrier raised between Christians and Jews is condemned, with Schaoul as its principal guardian. But as with Eléazar in the opera La juive, the patriarchal Jewish father is not presented in exclusively negative terms. While Schaoul forcefully affirms his Jewish identity, he also acknowledges the value of all religions and concludes that all of them can be reduced to the Golden Rule: Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.61 Schaoul accepts the principle of religious toleration, but not of religious liberty; he refuses to acknowledge that his daughter has the individual right to choose her own religion at the expense of family tradition and communal solidarity.

Foa’s interest in conversion was personal as well as professional. In the early 1840s she began writing saints’ lives, and in 1846 she converted to Catholicism under the direction of the abbé Théodore Ratisbonne, a Jewish convert whom we will meet in the next chapter.62 We do not have any direct evidence that Foa’s own decision was accompanied by anguish and conflict, though her brother described their family as “ravaged by idiotic renegades and by shameless apostates.”63 But La juive and her work in general show us an innovative author from within the Jewish community appealing both to her own people and to a broader audience for “personal freedom against the constraints of religious intolerance and patriarchal authority.”64

The psychological and social dilemma of individuals who were aware of their religious freedom but also of their family and communal ties provided material rich with potential for a romantic generation of artists fascinated by the tension between individual will and collective pressure to conform. The romantics were not, however, the first to see the dramatic and aesthetic potential in issues of complex religious identity and the lure of conversion. Corneille’s Polyeucte (1643) and Racine’s Esther (1689) both take up these themes, though in different registers, and both were revived to great acclaim, in 1839 and 1840, with the Jewish actress Rachel in the leading female roles.65 Corneille’s play revolves around the decision of a Roman official in Armenia to convert to Catholicism in the third century. In the play Polyeucte’s decision leaves his new wife, Pauline, and his father-in-law, Félix, distraught and angry, but he asserts that his duty to God requires him to abandon all other loyalties: “To please God we must neglect wife, property, and rank.”66 In Corneille’s treatment, however, this argument does not go unanswered, as the playwright gives Pauline and Félix several long and forceful speeches in which they try to persuade Polyeucte to reconsider his decision for the sake of his family and his state.67 The situation is aggravated because of the public nature of Polyeucte’s conversion, which led him to destroy the pagan idols in the local temple. In the face of all their pleas Polyeucte is adamant: although he loves and honors his family and community, his first duty is to God, and to his own salvation. He refuses as well the offer to feign attachment to the pagan gods while remaining a Christian in his inner life. Although tortured by the decision, Félix is compelled by his anger, and by his duty to the empire, to send Polyeucte to his death. This is not the end of the story, however, for Pauline, in witnessing the execution of her husband, is herself suddenly converted to Catholicism and returns to her father to plead that he have her killed as well, so she might join Polyeucte:

In death my husband left his light to me.

His blood, in which thy executioners bathed me,

Hath now unsealed mine eyes and opened them.

I see, I know, and I believe.68

Félix responds by acknowledging Christianity in turn, converted like his daughter through his act of martyrdom, though he cannot fully understand what has happened to him:

I made of him a martyr.

His death has made of me a Christian.

I ushered him to his bliss; he now seeks mine.69

The conclusion of Polyeucte is surprising if we keep in mind the earlier scenes, when Pauline and Félix were so determined in their opposition to Polyeucte’s conversion, and so hostile to the religion that drew him away from his family and his community. But the closing scene, while implausible, manages to reconcile Polyeucte’s stubborn commitment to his new religion, the forceful act of an individual will, with the value of family solidarity. The surprising conversions of Pauline and Félix reunite the family as converted Christians, reflecting the quest for religious unity in the seventeenth century, when Protestants challenged the hegemony of orthodox Catholicism. Corneille’s reconciliation of individual will and family solidarity resonated with audiences in nineteenth-century Paris, but as we have seen in considering Scott’s Ivanhoe and Halévy’s La juive, in the nineteenth century it had become possible to imagine such loyalty within a Jewish as well as a Christian family.

In Esther Racine tells the story of the queen of Persia who becomes the savior of her people when she finally admits openly to her husband that she is a Jew. Esther makes this decision after learning from her uncle and protector, Mordecai, that King Ahasvérus, deceived by the evil Aman, is about to have all the Jews of his empire murdered for disloyalty. Esther at first hesitates to declare herself a Jew, fearing for her own life, but Mordecai angrily insists that she put the welfare of her people over her own self-interest:

What! When you see your people perishing,

Esther, you hold your life to some account!

God speaks; and yet you fear the wrath of man!

What am I saying? Is your life your own?

Is it not due to them from whom you’ve sprung?

Did He not destine you to save His people?70

Esther, persuaded by Mordecai, reveals her Jewish identity to Ahasvérus and proves to him the Jewish people have always been loyal subjects. In the closing scenes he sends Aman to his death, grants to the Jews the same rights as all Persians, and allows them to rebuild their temple. Esther does not revolve around a conversion, but it does confront the issue of religious liberty, of the right of individuals to acknowledge and practice their faith even if they are in the minority. Racine had in mind the relationship of Protestants and Catholics, with Ahasvérus acting in a manner that recalls Henri IV’s granting of rights to Protestants in the Edict of Nantes. The revival of Esther in 1840 shows how this message embracing both tolerance and religious solidarity resonated in the nineteenth century, with an added dimension based on the starring role of the Jewish actress Rachel.

Although critical reaction was not unanimous, the productions of both Esther and Polyeucte were popular with audiences, part of the broader revival of French classical theater in the late 1830s, a development closely associated with the career of Rachel.71 With Esther and Polyeucte audiences were engaging with characters who were exploring the same tension between individual religious identity and familial and communal solidarity that I see as a general preoccupation in French culture during this period. The starring roles of the Jewish actress Rachel in these plays underlines this conflict, which emerged explicitly in the responses to her performances, and to her career in general. As Rachel Brownstein has written, “Debate about who Rachel really was, and what she stood for, and whether she had a claim to stand for anything, raged right alongside arguments about the quality of her art.”72 Rachel’s performance in Polyeucte led some to foresee her conversion, and rumors about her attraction to Catholicism circulated throughout her career. But Rachel, born Elisa Félix in 1821, explicitly denied these rumors, and at several points in her career went out of her way to affirm her Jewish identity. Stories circulated that she, the daughter of Jewish peddlers, made her earliest impression on her family as a potential artist by reciting the tale of the Wandering Jew. In assuming her stage name in 1836, Rachel evoked both Jewish history (Rachel was the second wife of Jacob) and the contemporary cultural milieu, echoing the name of the heroine of Halévy’s La juive, whose music was still in the air a year after its premiere. On one occasion, Rachel was asked in the Catholic salon of Madame Récamier to recite the speech in Polyeucte in which Pauline announces her conversion with the assertion “I believe.” Rachel refused and instead chose a text from Esther in which the character affirms her Jewish identity.73 Angered by the rumors that she might convert, Rachel arranged for a formal denial to be published in L’Univers Israélite, which praised her for her “faithfulness to her religion,” making her one of the glorious representatives of the Jewish nation in France.74

When placed in the context of the other works considered here, the successful revivals of Esther and Polyeucte confirm the fascination of Parisian audiences of this period with characters who represented the divided loyalties that could come into play when individuals pondered their religious identity and the possibility of conversion. This theme shows up in a variety of genres, in popular and elite fiction, in the theater and on the opera stage, and it is presented from a variety of perspectives, some with melodramatic simplicity, others more attentive to the psychological depth of the characters. While linked by a common theme, these stories produce different outcomes: Chactas converts, but Rebecca does not, nor do the Rachels in Halévy’s and Foa’s different versions of La juive, nor Raoul in Les Huguenots. In Corneille’s play the conversion and martyrdom of Polyeucte lead his wife and father-in-law to the baptismal font, but only after substantial resistance. There is a powerful erotic element in these stories, as men and women find themselves caught between their love for each other and their ties to their families and communities. The Jewish women fall into the broad tradition of la belle juive, the beautiful Jewess whose appeal is due in part to her status as exotic and out of bounds for a Christian man.75 The Wandering Jew, hovering as a cultural backdrop to these stories, endures in an ambiguous status, somewhere between Judaism and Christianity. These stories vary in context and outcome, but all of them use religious difference and conversion as a way to explore the fraught and potentially tragic relationship between an individual and his or her family and religious community. The theme of conversion was clearly well-suited to an age in which romantic artists were preoccupied with individual struggles to define themselves against the constraints of social institutions and conventions. But the romantic evocation of conversion suggests as well that questions about belonging to and wandering from a religious home define a transitional moment in the history of religious liberty.

Heinrich Heine’s Paris Wanderings

As Heinrich Heine (1797–1856) prepared to move to Paris in 1831 he imagined himself engaged in a religious quest: “Every night I dream that I am packing my trunk and travelling to Paris to breathe fresh air, to give myself up entirely to the sacred feelings of my new religion, and perhaps to receive the final consecration as a priest of it.”76 Heine relished the freedom he found in Paris, his home for the rest of his life, where he maintained his reputation as the leading German poet of his generation and assumed a “preeminent position in the Parisian press.”77 Through his essays in the Revue des Deux Mondes and in the German press Heine became the most important intermediary of his time between French and German culture. In both his poetry and his journalism Heine dealt frequently with questions of religious difference and identity. A Jewish convert to Protestantism, Heine identified with the Wandering Jew, but also for a time with the cult of Saint-Simonianism, before finally settling into a renewed but complex relationship with Judaism.78 Taking advantage of the religious liberty he found in Paris, Heine wrote about the religious choices he faced with a combination of engagement, humor, and irony that resonated with a European audience and that illuminates the spiritual landscape within which he lived.

Heine’s religious journey began in his native Düsseldorf, where Jews experienced a taste of liberty when the city was made the capital of Napoleon’s short-lived Duchy of Berg (1805–1813). With the Restoration Berg was attached to the Prussian state, which began “systematically restoring the pattern of discrimination that had been relieved during the time of Napoleon.”79 Acting from prudential reasons rather than religious conviction, Heine converted to Protestantism in June 1825, just after finishing his studies at the University of Berlin. This was a common tactic at the time for German Jews who were anxious “to conform, escape stigma, gain professional rights, bolster social status, win a government or academic post, marry.”80 Heine was anxious to win an appointment in the German university system, but a recent prohibition against hiring Jews in such positions made this impossible. His decision failed to convince the authorities to appoint him and made him subject to attacks for insincerity and duplicity. For the rest of his life, Heine struggled with his Jewish identity, which accompanied him even when he sought to put it aside.81

Heine’s regret and bitterness about his conversion is evident in “To an Apostate,” a poem written not long after his baptism. In it Heine condemns an unnamed convert as a fickle and spineless hypocrite: “You have humbled yourself before the cross, the very cross that you despised, that only a few short weeks ago you sought to tread into the dust.”82 Although there is clearly an element of self-loathing in “To an Apostate,” the poem may have been targeted at Edward Gans, one of the founders in 1821 of the Society for the Culture and Science of the Jews, which Heine joined in 1822.83 Although short-lived, this institution marked an important stage in Heine’s life, and in the history of Jewish studies. During its brief existence it pursued a serious examination of Jewish history, conducted according to the standards of contemporary academic scholarship. But it was at the same time a project designed to elevate the understanding of and respect for Jewish tradition, to bridge the gap between Jewish and gentile culture, while still preserving a unique Jewish identity. Heine’s own religious education had been minimal, but his association with the society brought him into contact with scholars such as Gans who looked to create a new kind of Judaism that could be reconciled with modern reason. The society collapsed following the abandonment of Judaism by Gans, but Heine remained deeply concerned with the relationship of Jews to a modern society that wavered between policies of toleration and exclusion. Heine’s engagement with Judaism in the 1820s expanded to a broader interest in religion that he explored on both a personal and philosophical level during his Paris years.

Heine was at best a lukewarm Lutheran, but in one of his most famous essays, “The History of Religion and Philosophy in Germany,” which first appeared in the Revue des Deux Mondes in 1834, Luther is given a generous though critical review as “the poor monk chosen by Providence to destroy the world empire of Rome.”84 For Heine the direction of history was clear: the world moved from a gloomy, “spiritualist,” medieval Catholicism that was intellectually repressive and disdainful of our material selves, through the Reformation, which destroyed Catholic hegemony and promoted the critical spirit, and into a modern age of Enlightenment, in which dogmatic and repressive religions were replaced by a rationalized philosophical outlook that would “vindicate the natural rights of matter against the domination of the spirit.”85 Heine acknowledged the influence of Hegel, one of his teachers at Berlin, in shaping his view of history, but in defending bodily experience and pleasure Heine was also embracing a key idea in the newest religion he found in Paris, Saint-Simonianism. Like a number of other Jews, including Fromental Halévy and his brother Léon, Heine was drawn for a time to this movement, even after its condemnation in 1831; Heine dedicated the French edition of his essays on Germany to Père Enfantin, the leader of the cult.86 Heine admired the affirmation of the physical body in Saint-Simonianism and embraced as well its pantheistic and progressive elements, declaring in another of his essays in the Revue des Deux Mondes that “everything is not God, but God is everything. God does not manifest Himself in like manner in all things; on the contrary, He manifests Himself in various degrees in the various things, and each bears within it the urge to attain a higher degree of divinity.”87 As is always the case with Heine’s religious choices, he stopped well short of identifying fully with Saint-Simonianism, which he reported on with sympathy, but from behind a “transparent mask” that both revealed and veiled his religious persona.88

Heine summarized the religious principles he adopted in the 1830s in a brilliant and controversial essay on Ludwig Börne, also a convert from Judaism to Protestantism, and also committed to political and social reform. Heine and Börne had been close for a time, especially in the early 1830s, when they were in Paris together. But personal grievances and Börne’s sense that Heine was a dilettante and not enough of a revolutionary drove them apart. Although he continued to admire Börne’s support for movements of liberation, Heine identifies his former friend as a “Nazarene,” his term for a Judeo-Christian position comparable to “spiritualist” in its denigration of the body. On the other side of the religious barrier Heine sees “Hellenes,” “men with a realistic nature, with a cheerful view of life, and proud of evolving.”89 Heine’s appreciation of Saint-Simonian attitudes toward the material body was thus reinforced by an attachment to the exiled gods of the ancient world, driven away by an ascetic Christianity.90

Heine’s conviction that the Roman Church was a dreary and oppressive force crushing both spirit and body helps explain his vituperative response to the circle of Germans who converted to Catholicism, such as Friedrich Schlegel, or returned to the faith after a sojourn in the Enlightenment, such as Joseph Görres and Clemens Brentano. In commenting on German culture for his French audience, Heine condemned all of these men for “crowding back into the old prison of the mind.”91 Heine’s aversion to converts could apply as well to those who chose Protestantism, such as Gans and himself, as seen in “To an Apostate.” In the essay on Börne Heine criticizes his former friend for ridiculing rich Jewish converts as “old lice, who still hail from Egypt, and suddenly imagine they are fleas and hop around as Christians.” Heine does not directly challenge Börne for making this hostile comment, which resounds now as an antisemitic slur, but offers a modest demurral, reflecting on the fact that both of them were also converts: “In the house of the hanged, I interrupted him, one does not talk about ropes, my dear doctor.”92 Heine was critical of conversions that reflected reactionary political views or religious insincerity, though he realized that he was not on the most solid ground in taking this position. But unlike other artists and writers of the time Heine did not raise the issue of paternal authority or family solidarity as arguments against conversion, a reflection of his profound commitment to individual liberty.

Heine never abandoned his commitment to radical political and social reform, but his religious ideas changed dramatically in the last years of his life, when he constructed for himself an idiosyncratic Judaism that was far from orthodoxy but also from the Saint-Simonian and Hellenist ideas that he had preached for most of the 1830s and 1840s.93 Heine presented his final conversion to an attentive audience through poems and essays that traced the evolution of his religious ideas with passion, humor, and irony. Heine’s account of this last stage of his spiritual journey fascinated his readers at the time, providing them with a unique but telling example of the range of religious choices available to them. For readers then and now it offers a brilliant and exhilarating celebration of religious liberty.

Heine’s return to religion occurred during the last years of his life, when he was struck by a debilitating disease that left him paralyzed, confined to what he called his “mattress-grave” from 1848 to his death in 1856.94 His conversion was a much-discussed topic among his friends and enemies, as he acknowledges in the postscript to Romanzero, his last great collection of poems, published in 1851: “Yes, I have made my peace with the creation, and the Creator, to the great distress of my enlightened friends, who reproached me for this backsliding into the old superstitions, as they preferred to call my return to God.” In defending himself Heine embraced the idea of a personal God, in contrast to the God of the Pantheists, “who stares at you without will and without power. . . . If one desires a God who is able to help—and that after all is the chief thing—one must accept his personality, his transcendence, and his holy attributes, his goodness, his omniscience, his justice, and the like. The immortality of the soul, our persistence after death, is then thrown into the bargain just as the butcher throws some good marrow-bones into the shopper’s basket gratis if he is pleased with his customer.”95 Heine’s closing aside shows that even as he found his way back to Judaism he did not abandon his sense of humor.

Some of the poems of Romanzero look back with nostalgia on younger days and romantic conquests, but in a group of poems he labeled “Hebrew Melodies,” Heine celebrates Jewish history and explores the relationship between suffering and belief. In “Jehuda ben Halevy,” the most famous of these poems, Heine reviews the life of a poet who, like himself, lived and wrote in a city dominated by another religion. Jehuda was a Jewish scholar of twelfth-century Toledo who defended Judaism in the Kuzari, The Book of Argument and Truth in Defense of the Despised Faith.96 But Heine admires Jehuda more for being “a great and mighty poet,” a “star and beacon for his age, light and lamp among his people.” “Jehuda ben Halevy” opens with a quotation from Heine’s favorite Hebrew text, Psalm 137, the song of Jewish exiles in Babylon in which they weep as they remember their lost homeland. Although Jehuda is an exile in Toledo, he is steeped in Jewish culture, a student of both the Torah and the Talmud. From these texts he learned both “the science of polemic,” which allowed him to defend his people, and “the art of poesy,” a gift of God, a grace that makes the poet a “monarch in the realm of thought.” Jehuda hears from Jewish pilgrims sad stories of the devastation of Jerusalem that inspire him with love and longing and lead him as an old man to travel there as a pilgrim. In Jerusalem he mourns the city’s destruction with a “wild song of anguish” before being murdered by a Saracen who happens to be passing by. But as he dies Jehuda

tranquilly . . . sang his song out

To the end, and his last dying

Sigh breathed out: Jerusalem!

Jehuda’s pilgrimage and final words can be read as mirroring Heine’s own relationship to Judaism, a homeland for poets but also a site for their tragic deaths.

“Jehuda ben Halevy” is a moving historical account of Jehuda’s return to Jerusalem, but in a typical move Heine weaves into his somber reflections on Jewish exile an incident from his own life. Interested to learn the origins of the term “schlemiel,” Heine consults the writer Hitzig, a Jewish convert, who hems and haws, embarrassed about his knowledge of Jewish legends, until an exasperated Heine forces him to explain its history.97 According to Hitzig, “schlemiel” derives from the story of Phineas and Zimri, when the Jews were wandering in the desert after their flight from Egypt. In the biblical account (Numbers 25: 1–16) Phineas followed the orders of Moses in killing Zimri for fornicating with a Canaanite woman. In Heine’s poem, however, Hitzig reports an oral tradition in which Phineas mistakenly murders “Schlemiel ben Zuri-shaddai,” an innocent bystander. Heine sees the Jews of modern Europe as innocent victims, descendants of “Schlemiel the First,” still threatened by the spear of Phineas “ever with us, And we constantly hear it, Swishing round above our heads.”98 In “Jehuda ben Halevy” Heine reverentially invokes the history of Judaism, but he also ridicules contemporary converts and condemns priestly attempts to enforce a religious boundary between Jews and others.

In “Disputation,” the third and last of the “Hebrew Melodies,” Heine explicitly takes up the issue of conversion in imagining another scene from medieval Spain, in this case a debate between a Franciscan friar and a Jewish rabbi, with the price of defeat a move to the religion of the winner. In the early sections of the poem the rabbi seems to have the better of the argument, employing Voltaire-like logic to ridicule Christian dogma and defending an austere God based on the Old Testament. But the debate descends eventually into a disheartening exchange of insults, and Queen Blanche, designated to judge the results, concludes that “Who is in the right I do not know—but it seems to me . . . I think . . . /that the rabbi and the monk . . . that both of them stink.”99 This anticlerical jab aligns with Heine’s insistence in his last will and testament that no minister of any religion should be present at his burial. But he asserts as well that this position in no way reflects “free-thinking prejudice.” Instead, he renounces “all philosophical pride” and declares that he had “returned to religious ideas and sentiments. I die in the faith of one God, the eternal creator of the world, whose mercy I beseech for my immortal soul.”100 Heine’s return to religion was clearly an arrangement on his own terms, a diverse array of religious thoughts and feelings that range from conventional reverence and belief to a more ambivalent posture that challenges and affirms God at the same time.

As his disease continued to weaken him, and as rumors spread about his conversion, Heine decided to explain his religious transformation in the Revue des Deux Mondes. In introducing the Confessions of a Poet (Les aveux d’un poète) the editor called attention to the extraordinary position that Heine had achieved in France. Beyond the particular topics he addressed, Heine’s audience was drawn by the “personality of the poet, whose work is marked by a contrast between satire and sadness, bitter irony and emotion. . . . Placed alongside his firm political commitments, what do his jokes and skepticism mean?” Given this fascination with Heine, his decision to enlighten the public on the course of his ideas invoked “a lively interest.” Now readers would be able to follow the “principal changes in his inner life,” to learn “the secret of his hates and sympathies, joy and anger. . . . M. Heine has told us the story of his entire life.”101

Heine’s religious journey is at the center of the life he recounts in his Confessions, in which he claims inspiration from both Augustine and Rousseau. After opening with reminiscences of his first days in Paris and his attachment to the heterodox ideas of German idealism Heine turns to his recent years and reports that he has “returned to the cradle of faith, and willingly recognized the omnipotence of a Supreme Being, who rules the destiny of the world.” Heine, however, goes well beyond a commitment to a God who presides over human history from afar, for after five years of being confined to his bed, he finds a “great relief in having someone in heaven to whom I can address my moans and lamentations during the night. . . . How terrible to be alone and sick, with no one to bother with the litany of your complaints. How stupid and cruel are those philosophers, those cold dialecticians who insist on denying to those who suffer their divine consolation, the only relief that remains to them.”102 In his Confessions Heine reaffirms the position he took in Romanzero, embracing a personal God who will listen to someone wracked with pain, suffering, and close to death. He leaves open the question of how God responded to his “moans and lamentations.”

Heine’s return to religion was a subject of public conversation, with rumors circulating that he had converted to either Protestantism or Catholicism. In the Confessions he denies any such conversion and affirms that he has “never been taken by any dogma, nor any cult.” Heine mentions Christ briefly, but Moses draws most of his attention, as the “great emancipator, valiant priest of liberty, opponent of all slavery.”103 In addressing the issue of his religious identity Heine acknowledges the source of the rumors that he had converted to Catholicism: his marriage to his wife, Mathilde, in a Catholic ceremony in the church of Saint-Sulpice. But Heine insists that he made this concession only to avoid “troubling a pious soul who wished to stay faithful to the religious traditions of her father.” Heine denies converting to Catholicism but takes a benign view of those who were drawn to this “pious illusion.” Their intentions were honest, he writes, and “whatever reproach one might make to these Catholic zealots, one thing is certain: they aren’t selfish; they’re concerned with their neighbor, unfortunately sometimes a little bit too much so.” Following this train of thought, Heine proceeds to a series of positive comments on the education offered by the church and the clergy, particularly the Jesuits, which leads in turn to his recollection of his secondary education during the French occupation of Düsseldorf. It is at this moment in the Confessions that Heine breaks into one of the surprising humorous turns that fascinated his readers, as he imagines living an entirely different life, which would have brought him to Rome, and not Paris.

As a student in the lycée established in Düsseldorf during the French occupation Heine was taught by its rector, a Father Schallmeyer, “who exposed us to Greek thought, including the most dangerous skepticism so thoroughly opposed to the orthodox dogmas of Catholicism. And yet he was a priest of this religion, who said Mass before its altar.” Impressed by his student, Father Schallmeyer approached Heine’s mother to see if she would consent to sending him to study in a Roman seminary. Schallmeyer assured Heine’s mother that with his connections at Rome her son would achieve a prestigious position in the church. Madame Heine refused this offer, though Heine reports that she regretted this decision after she saw the difficulties put in the way of his secular career. But Heine seizes the opportunity of this memory to imagine a leap into a Catholic life. What would have happened, he wonders, had his mother accepted the offer, and had Heine gone to Rome? Heine answers this question by spinning out a fantasy in which he would have risen high in the church, becoming one of those cultivated prelates who serve not only the church but “Apollo and the Muses.” He would have pursued poetry and the arts, flirted with divas at the opera, and made “delicate observations on the anatomy of the models of artists when I visited their studios.” In preaching to the most distinguished congregations of Rome Heine would have combined a preaching of “moral severity” with language that would not be “too austere,” and would not “offend the ears of delicate consciences.” He would have flattered the right women so that he would climb ever higher, and in the end, although insisting that “I am not naturally ambitious,” he admits that he “would not be able to refuse the pontificate, if the conclave were to choose me.” In a climactic moment Heine pictures himself carried in triumph through the arcades of St. Peter’s, and then, “with absolute seriousness, because I can be very serious when it’s absolutely necessary,” he would give to the enormous crowd kneeling before him the urbi et orbi papal blessing.104

Robert Holub is certainly right to describe Heine’s Confessions as an “unusual text . . . a strange performance” that indicates he “had trouble confronting or processing [conversion] mentally.”105 He is right as well to see this late work as “invaluable if we hope to understand the complex workings of Heine’s mind,” but these points might well be extended beyond Heine to cover a broader French public. From this perspective the image of Pope Heine blessing Rome and the world is a testament to his sense of humor and his wit, but also to the extraordinary range of religious possibilities that could be imagined in Paris in an age of religious liberty.