CHAPTER

2

WHAT’S YOUR BODY TYPE?

IF YOU’RE LIKE MANY PEOPLE, YOU MIGHT ANSWER THIS QUESTION with a response like “hot,” “weak,” “strong,” “flabby,” “curvy,” or another adjective. In your defense, trying to evaluate your own body type in the abstract is a loaded proposition because there’s a good chance you’re judging it based on what you wish it looked like, rather than how it actually looks right now. But there are ways to ditch the subjective judgments and figure out what your natural-born body type is, objectively speaking. If you were to talk to your doctor about your weight and body type, the conversation would inevitably gravitate toward Body Mass Index (BMI), which indicates if you are underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obese. In my opinion, BMI is a vague, outdated measurement because it doesn’t account for your body composition—variables such as muscle, water, fat, hormones, or bone size, all of which are important. Based on the BMI charts, I fall somewhere between the overweight and obese categories, but my excess weight is all muscle (I have 9.5 percent body fat). Healthcare professionals use BMI because it’s the only standardized way to compare people’s bodies and create some sort of database regarding a person’s height-to-weight ratio.

To get a more precise assessment of your body composition, you could go to a lab and have your body fat, bone, and muscle mass measured, then have various ratios calculated, which would give you a scientific result. But there’s an easier, more accessible (and less expensive) way to gauge your body type at home. And I’m about to walk you through it. So grab something to write with and let’s get to it.

Read each of the following questions or statements thoroughly and choose the option that best describes you. Be honest in your responses (you won’t be graded on this!). If you’re not sure which of two responses applies to you, trust your instincts or choose both (you’ll see why later).

1. From an objective point of view, which of the following issues seems most prominent (or dominant) on your body when you look in the mirror?

a. Bone

b. Muscle

c. Body fat

2. How do your shoulders compare to your hips?

a. My shoulders are narrower than my hips.

b. They’re approximately the same width as my hips.

c. My shoulders are wider than my hips.

3. Which of the following objects best describes your body shape?

4. If you encircle one wrist with your other hand’s middle finger and thumb, what happens?

a. My middle finger and thumb overlap a bit.

b. My middle finger and thumb touch, but just barely.

c. There’s a gap between my middle finger and thumb.

5. When it comes to your weight, which of the following patterns best describes your history?

a. I have trouble gaining muscle weight or body fat.

b. I can gain and lose weight without too much difficulty.

c. I gain weight easily but have a hard time losing it.

6. Think about what your body looked like, before you corrupted it with poor dietary and exercise habits, once you reached your full height as a teenager or young adult. How did you look?

a. I looked long and lanky.

b. I looked strong and compact.

c. I looked soft and full bodied.

7. If you’d been exercising regularly and you were to take a break for a few months, what would happen to your body?

a. I would lose muscle and strength quickly.

b. My body wouldn’t change that much.

c. My body would soften up significantly and I might even gain weight.

8. Put on a pair of form-fitting jeans—where on your body do they get extra clingy or even stuck?

a.They don’t. In fact, I can’t keep them up without a belt.

b. With a bit of work, I can wriggle my way into them over my muscular thighs.

c. They get caught on my butt or belly.

9. When you have a serious carb-fest (think: heaping plate of pasta or multiple slices of pizza), how do you feel afterward?

a. The same as I usually do—normal, really.

b. I generally feel good, though I notice my ab muscles are extra hard or my belly feels full.

c. More often than not, I feel tired or bloated for a few hours after the meal.

10. How would you describe your body’s bone structure?

a. I have a small frame.

b. I have a medium frame.

c. I have a relatively large frame.

TIME FOR SCORING

Add up the number of times you answered A, B, or C. If you chose mostly A’s, you’re an ectomorph; mostly B’s, you’re a mesomorph; mostly C’s, you’re an endomorph. If your responses were divided fairly equally—as in 5 and 5 or even 6 and 4—between two different letters, you likely have a hybrid body type. To be specific, if your responses were split between A’s and B’s, you’re an ecto-mesomorph; if they’re spread between B’s and C’s, you’re a meso-endomorph; and if you found your responses in a 50–50 or 60–40 split between A’s and C’s, you’re an ecto-endomorph. If you end up with a 7–3 division between two different types, it may mean that you’ve strayed off course from your true type with poor dietary choices, in which case the hybrid approach will steer you back on the right track.

Here’s what this form of typecasting really says about you:

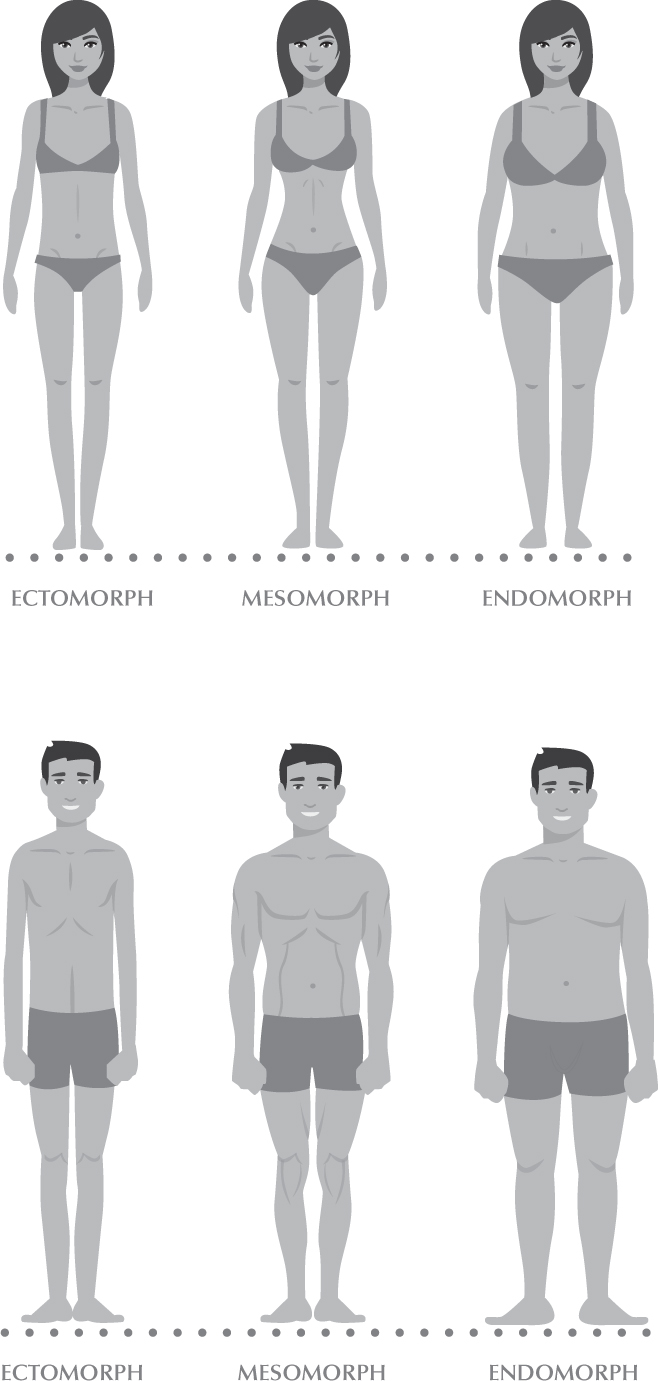

ECTOMORPHS: Generally thin and lean, ectomorphs tend to have slender waists, narrow hips and shoulders, small joints, and long legs and arms. They tend to be slim, without much body fat or noticeable muscle mass. Because they have fast metabolisms, they burn calories quickly, so ectomorphs may find themselves hungry frequently throughout the day; yet, regardless of what, how often, or how much they eat, they don’t gain weight or muscle easily.

MESOMORPHS: Naturally muscular, mesomorphs typically have moderate-size frames, with wider shoulders and a narrow waist, strong arms and legs, and modest amounts of body fat. They are genetically predisposed to build muscle so mesomorphs often require a slightly higher calorie intake (since muscle requires more calories to maintain it) and more protein than the other types do (again, for muscle maintenance). Generally, mesomorphs are able to lose or gain weight easily.

ENDOMORPHS: Because they have a medium-to-large bone structure and more body fat than the other types, women who are endomorphs are often described as curvaceous or full-figured, while endomorphic men might be considered stocky, doughy, or round. Endomorphs usually have narrow shoulders and wider hips and carry any excess weight in the lower abdomen, hips, and thighs. It’s often challenging for them to lose weight but with the right diet and training approach, it can be done.

ECTO-MESOMORPHS: These hybrids are increasingly common, especially in the athletic world where this physique is prized for being aesthetically appealing. In fact, for men and women alike, ecto-mesomorphs tend to have the “fitness model” look. Often muscular with V-shaped torsos (think: wide upper back, developed chest and shoulders, narrow waist), ecto-mesomorphs are lean and agile, with strong-looking (but not bulky) arms and legs. (Btw: I’m an ecto-mesomorph. I’ve always been naturally long and lean, and I was able to build significant muscle with the right diet and exercise regimen.)

MESO-ENDOMORPHS: Including variations where people have more predominantly mesomorphic or endomorphic qualities (rather than a truly even split), this is the most common hybrid, according to research. Many bodybuilders and contact sports athletes (like football players) have this body type. Characterized by thick arms and legs and a boxy chest and mid-section, this type looks powerful but it isn’t chiseled. (This may be partly because people with this body type tend to retain water and a layer of fat on top of their muscles.) People with this kind of build who want to get a leaner physique should be prepared to take a more refined approach to resistance training, cardio workouts, and diet, so they can prioritize fat loss.

ECTO-ENDOMORPHS: Usually, this is a behaviorally acquired body type—basically, someone who is really an ectomorph has added significant body fat, whether it’s from poor eating habits, sedentary ways, or a combo of these less-than-stellar habits. With long limbs and a smaller bone structure, ecto-endomorphs often have soft midsections, droopy chests, and flabby upper arms and legs from sheer neglect. To improve fitness, body composition, and health, the most efficient plan for this type involves resistance training and high-intensity cardio, both of which promote muscle growth and stimulate metabolism. Since ecto-endomorphs may have developed some insulin resistance, their bodies may not be as efficient at burning carbohydrates so I recommend a dietary plan that’s suited to endomorphs—with a slightly higher protein intake, a medium fat intake, and lower carb levels—until the excess body fat comes off and metabolic function is optimized; then, these hybrid types can switch to more of an ectomorph approach (adding in more carbs).

WHAT ALL THIS MEANS FOR YOU

Now that you have a greater understanding of your body type, you’re in a better position to alter your diet and fitness regimens to suit your body’s needs. Remember: generally, body types lie on a spectrum, rather than being distinct points on a grid or graph. Chances are, you have either a dominant body type with characteristics of another one or a true combination body type that’s evenly split between two different ones. Already, this increased awareness and knowledge probably put you a few steps ahead of where you were. If you’re like many people, you’ve probably misjudged your body type in the past, whether it was because you didn’t understand the different somatotypes, you had general body insecurities, or you were excessively critical about your body. Let’s face it: it’s a common phenomenon. In my experience, about 50 percent of people get their body type wrong, and the media and social media can lead any of us to compare our bodies to unrealistic standards and come up with skewed perceptions of our own physiques. But remember: the body ideals portrayed in the media are often digitally altered or enhanced with special filters, lighting, or other forms of manipulation, which means they’re not natural or real. Which means you’ve been comparing yourself to an illusion, really. Alternatively, you might misclassify your body type based on comments your parents or other influential adults made to you over the years or phantom body-image issues you have now (if you used to be heavier or had an eating disorder, for example). It could be that you’re discounting the proportion of muscle you have on your body and erroneously equating size with body fat, or that you have a mental health condition such as body dysmorphia (an obsessive focus on a perceived flaw in your appearance). Whatever is at the root of your past body misclassification, it could mean that you’ve been training the wrong way because you’ve been viewing and treating your body the wrong way.

Or, maybe you had an accurate sense of what your body type is but you jumped on the latest fitness fad or diet du jour, regardless of whether it was appropriate for your physique. The problem is, that’s like trying to rebuild or maintain your car’s engine using the wrong manual (such as the one from your motorboat or moped). At best, it’s ineffective and a waste of time; at worst, it can bite you in the a**.

I’ve met plenty of people who know they’re endomorphs but they defiantly believe they can out-exercise their lousy diets and their body’s natural physiology. Or, they concentrate on crash diets and cardio workouts and end up eating too little, restricting their calories and carbohydrates excessively and continuously riding the yo-yo-diet rollercoaster with peaks, valleys, and binges along the way; meanwhile, they’re surprised when they don’t end up building muscle definition or reaching their long-term fitness goals.

Similarly, there are ectomorphs out there who have slipped into the ecto-endo zone over time and come to perceive themselves as pure endomorphs because of the excess pounds they’ve added to their frames (essentially they’ve become “skinny-fat” with slim arms and legs and a rounder midsection). At the gym, some of them will spend 45 minutes a day on the treadmill or the elliptical; they might restrict their carb intake and avoid eating anything after 6 p.m.—and still be unable to transform their physiques the way they want to. What they should be doing is ditching the immediate gratification of cardio-intensive, calorie-burning workouts and focusing on the big picture instead: adding lean muscle mass to their physiques through the right pattern of resistance training and following the optimal dietary plan (with enough calories) to fuel their muscles and their metabolism, as you’ll see in the chapters that follow.

GETTING AND KEEPING IT REAL

When I start working with a new client, the first step is usually for us to get to know each other in person, usually over coffee, outside of the gym. I like to get a sense of what clients’ lives are like at work and home, how high their stress levels are, what their eating and exercise habits are like, what their weight history is, and what their current fitness goals are. This way, I can get a sense of what real-world challenges might end up creating roadblocks or ultimately derailing their best intentions. In other words, I’m trying to gauge what’s realistic for us to do in an efficient manner. After all, most people can’t completely reorganize their lives to make body transformation their top priority, nor do they have the financial resources to hire the trainers, nutritionists, personal chefs, and other assistants who can support the cause (the way many Hollywood people do).

Hot tip: if you’ve been using a particular diet or workout approach for a month and nothing about your body has changed, it’s not right for you. It’s that simple. Let’s say a client tells me she gets bloated after eating certain foods (such as dairy products, items with lots of sugar or refined flour, fried foods, and other pro-inflammatory foods) or another client shows me his “soft” body and says he eats 100 percent vegan and has been doing body-weight workouts three times per week to try to gain muscle definition and tightness to no avail. Between hearing either history and doing a quick visual assessment of the person, I would probably have an “aha” moment—realizing that she or he is a pure ectomorph, in which case the approach the person was taking wouldn’t deliver the desired results for her or his body type.

With the right approach, can I help you look like Henry Cavill in Superman or Gal Gadot in Wonder Woman? Sure, but it will take a heckuva lot of hard work and discipline so it’s important to get a reality check about what you are willing to do to reach your goals before moving forward. The truth is, consistency trumps nearly everything else when it comes to body transformation, which is why it’s essential to figure out what’s realistic for you to commit to; that way, I can develop a workout and meal plan that make sense for you and your life.

Part of this assessment process involves evaluating a client’s body type. After training people for so many years, I often have an instinct for what a person’s natural body type is, but as we all know, looks can be deceiving. And sometimes my initial hunches may be off base, especially if the person has significantly changed his or her body through dieting, exercise, or even surgery.

Since you and I can’t meet for coffee (though I wish we could), it’s up to you to gauge your body type so that you can then choose the approach that seems to best suit your physique’s natural tendencies and your personal goals. My aim with this book is to help you become your own personal trainer and nutritionist. So take yourself out for coffee, think about what your life is like at work and home, how high your stress level is, what your past weight history has been (it can help to look at old photos), and consider what your current goals are. Next, think about how hard you’re willing to work to reach them, then go home and map out a plan of action.

When I first bring a client into the gym, I’ll take body measurements—weight, height, and body fat percentage, as well as measuring his or her chest, waist, thigh, and arm circumference. Since I can’t do this for you personally, enlist a friend or partner’s help or go ahead and DIY (but keep in mind: having someone help you really does improve accuracy). Don’t be scared away from doing this—it provides a baseline assessment of where you are now so you can track your progress. Taking measurements is an especially good way to do it because losing inches arguably counts more than the number on the scale (especially since muscle weighs more than body fat does but it looks tighter, more compact, and, well, just better).

You’ll want to take four main measurements: around mid-biceps in your upper arms, at the thickest part of your upper thighs, around your bust/chest (at the fullest part), and around your natural waist (the narrowest part of your torso between your belly button and your breastbone). It’s essential to measure yourself correctly or you’ll get a distorted sense of what’s happening with your body; in other words, your measurements are only as accurate as your technique. So don’t pull the tape too tightly or let it dig into your skin; also, don’t flex your muscles, suck in your gut, or hold your breath while taking your measurements. Hold the tape straight and flat as you wrap it around each body part. Write down your measurements (in inches or centimeters, your choice) or keep a log on your smartphone and retake them every couple of weeks to gauge your progress. Trust me, numbers don’t lie, so this is a great way to monitor your progress.

Whether you want to slim down or simply add definition to your muscles, the underlying goal is to harden your body, which means the numbers will generally shrink as you embark on the body-type program that’s best for you. This means you’ll be losing body fat and gaining lean muscle mass, which is probably just what you want. Even better, adding muscle mass to your frame through resistance training, which you’ll do in some fashion with each of the body-type regimens, will increase the efficiency of your hormones (including testosterone, thyroid hormone, and growth hormone) as well as the function of your endocrine system (including insulin production and sensitivity and blood sugar regulation). What’s more, your metabolic rate will pick up its pace once you have more muscle on your body, which means you won’t have to sweat your calorie intake as much as you may have in the past.

Sounds promising, right? Let’s get started! In the chapters that follow, you’ll discover the best workout and dietary approaches for your body type, strategies that will help you achieve your long-term slim-down, get-toned, or shape-up goals. This will help you create a roadmap that will bring you to a destination where you’ll feel and look fitter and function better than ever—and be able to sustain those benefits. Along the way, you’ll come to understand the perks and challenges that are unique to your body type and figure out how to refine some of the nutrition and exercise aspects of your program so they’re more effective for your body and your life. In that sense, this approach will become truly personalized—as in, just right for your type.