We are accustomed to think of literature, as distinct from philosophy, history, science, and the like, as “imaginative writing.” By that we generally mean it represents particular persons, places, and events that an author has imagined, rather than actually experienced, or, at any rate, that readers must imagine without having to judge the truth or falsity of this pretend world.

My reason for introducing this uncontroversial notion here is first to endorse what I trust is by now another uncontroversial notion, namely, that imagination is a process that in many ways replicates visual perception. In my Poetics of the Mind’s Eye (1991a), which was grounded largely in the work of the cognitive psychologists Allan Paivio, Roger Shepard, and Stephen Kosslyn, as well as that of the cognitive linguists Ronald Langacker and Leonard Talmy, I attempted to show how literary texts induce us to simulate actual visual events in a format that is borrowed partly from dream, partly from episodic memory. In this chapter, which incorporates more recent research on visual cognition, I hope to add to and clarify the theory of imagination I presented in 1991. Placed just prior in this evolutionary saga to the emergence of protolanguage, this chapter will introduce preliminary evidence for another claim, one that I will subsequently spell out—that visual perception and imagination formed the basis for language and, consequently, for verbal artifacts.

Language and its artifacts evolved out of visual perception and imagination: really? Well, yes … but not quite. When it comes to describing cognitive processes, simple linear accounts often falsify reality. As Einstein advised, we should strive to make everything as simple as possible, but not simpler. I will first follow this maxim by describing the simple structure of the eye and how that contributes to our view of the world. Then, as I explore the neural anatomy responsible for perceptual processing and action governance, I will honor the “not simpler” proviso. In this deeper anatomy we will again find a coordinated doubleness, both in the circuitry of the visual brain and in the two alternate ways we have of organizing visual space. I will go on to speculate that this dyadic pattern, which governs the way we receive and process visual data, has so profoundly impressed itself on cognitive mechanisms that it marks an outer limit of our conceptual powers.

A word of caution: the topics I deal with in this central chapter do themselves challenge our conceptual powers. At any rate, they do not lend themselves to easy exposition. Much of what I discuss is neural architecture buried deep within the brain, so in this chapter, devoted to the sense of sight, most of what I talk about lies totally hidden from sight and resistant to visualization. I do, however, revisit and build on earlier introduced themes, e.g., perception and action, figure and ground, and parallel and serial processing. In portraying how these operate, I must stretch the capacity of that old technology, words, and depend on the reader’s even older brain-scanning device, the imagination.

Vision and the Visual Imagination

The eyes of a hunter-gatherer are acute. Flesh, fruit, tubers, honey hives—these are isolated, desirable objects amid a multitude of less interesting things. When those first adventurous bands of hominids, our earliest ancestors, left the safety of the forest canopy to range the grasslands of East Africa some 6 mya, they turned their binocular/stereoscopic vision toward an expanded vista. In the forest the objects they saw—and heard and smelled—had been intimately near at hand, within a hundred feet on average, but on the rolling savannahs they might make out herds and fruit trees, springs and rocky ledges, many miles away. Here was a multitudinous array of distant details that could neither be heard nor smelled but only seen, an environment that determined over time that only the best sighted among them would survive and transmit their optical acuity to succeeding generations.

A viewer’s eyes gazing fixedly ahead survey a broad field, an oval that is nearly 160 degrees from side to side and 135 degrees1 from top to bottom, though early hominids would have had a shorter visual field in the vertical axis due to their overarching brows. Thanks to binocular vision, there is considerable overlap of the right and left ocular fields. Each eye therefore reinforces the other in straight-ahead central vision. Since the two eyes are separated on the face, the two views they produce have slightly different spatial orientations, which the brain uses to compute the relative depth of objects, the 3-D effect. Our ancient ancestors would no doubt have spent some time, as we do, in unfocused vision, their open eyes taking in the environs with no particular object in mind, but in that perilous world they must have spent much more of their time intensely gazing about them, on the lookout for predators they needed to elude and for food they needed to capture.

On the basis of fossil and current primate evidence, evolutionary biologists assure us that the anatomy and physiology of the primate eye has remained virtually unchanged for at least the past 10 million years. At the center of the broad oval visual field just described, there appears a small, clear disk. This central field (about 15 degrees in diameter) has at its midpoint the smaller, even sharper foveal field (about 1 degree across). One way to demonstrate how these two fields work is to hold your hand at arm’s length, palm inward, and try to see all its lines, creases, and contours without moving your eyes. (The experiment works equally well whether you use one or both eyes.) If you focus on the center of the palm, the mounds at the bases of the thumb and fingers seem less detailed and the thumb and fingers seem progressively fuzzier as they radiate from the palm. The central field is simply too small to encompass this space. Within it, the even smaller foveal field, densely packed with contour- and color-sensitive cone cells, is used for scrutinizing minute details. If you now turn your stretched palm outward and gaze at your little finger, only its nail (approximately 1 centimeter in diameter) is acutely visible, for it projects its image on that 1-degree disk of cells at the back of the eyes.

To recognize an object that overflows the central focal field—e.g., a person’s face at a distance of 10 feet—the eyes must perform a set of rapid movements (saccades) and a set of momentary fixations. The brain then converts these part-perceptions into a complete, meaningful figure isolated from its surrounding ground. The size of this central field is necessarily small, for if the eyes could present to the optic nerves the entire visual field in perfect clarity the input would overwhelm the brain with random data. That is one good reason why, in the area outside the central field, objects appear less sharply contoured and colored.

Surrounding this 15-degree central field lies the much larger peripheral field, constructed by the motion-sensitive, but less detail-sensitive, rod cells of the retina. Yet despite its diminished acuity, the peripheral field is essential to the function of central vision, for it provides the brain with a broad, general account of the environment and of possibly important objects moving there, even in dim light and shadow. In certain circumstances, we can in fact use peripheral vision as our sole viewing mode. When, before we cross a street, we look both ways, we turn our heads only so far as to glimpse moving vehicles in our left and right peripheral fields. Consider, too, the way we search for a misplaced item—e.g., our car key, which we must have somehow dropped on the way from our parked car to our front door. If the area is too large, we do not choose to use our focal vision. That key could be anywhere, so, to save time, we shift from focal to peripheral vision by locking our eye muscles in place and slowly rotating our head, effectively suppressing the saccadic mechanism that generates sharp ocular fixations. As we broadly scan the area, we keep in our mind a generalized image of a silver-colored key and its ring. If any shape that even vaguely resembles that object registers in our peripheral field, we stop and direct our central vision upon it. In short, the peripheral field is like a broad net cast upon the world: whenever a useful object is caught in it, the spear-like central vision darts forth toward that object and transfixes it.

A common notion of folk psychology is that seeing is indeed a kind of spear throwing, but one in which the spear is made of light. According to this conceptual metaphor, known as “extramission,” the eye sends forth a “ray” or “beam.” Interestingly, both these words originally meant wooden projectiles, shafts, as in the metaphor “shafts of light,” itself a related instance of folk physics. Accordingly, we “cast a look,” “shoot a glance,” have “darting eyes,” “stare daggers,” and so forth. Though this metaphor inaccurately represents visual perception, it does correctly portray focal vision as a conscious, voluntary turning of attention to objects.2

While this ancient metaphor reminds us that central vision is indeed an action, we sometimes forget that peripheral vision can also be an active process. Though it is usually a “preattentive” process, it is sometimes intentionally preattentive when used to perceive simple shapes and faint sources of light, as my key-search situation suggested. Before optical instruments were available, astronomers used what is called “averted vision” to locate low-magnitude stars, clusters, and nebulae. Henry David Thoreau, who used this method to perform terrestrial as well as celestial searches, raised it to the status of an epistemological principle: “Be not preoccupied with looking. Go not to the object; let it come to you…. What I need is not to look at all—but a true sauntering of the eye” (Thoreau, 1962:488). When you become adept at this, you become “open to great impressions and you see those rare sights with the unconscious side of the eye, which you did not see by a direct gaze before” (592).3

Central and peripheral vision generally correlates with the figure–ground distinction. Like all animals that survive by searching for food, while avoiding becoming the food of others, we need to perceive freestanding figures as visually separate from their ambient ground. Figures, once selected, cue the associated images that we animals, bred for the hunt, still carry about in what might be called our internal “field guide”—representations of plants that are good to eat, plants that are insipid or poisonous, animals that are tasty and catchable, animals that are fierce or venomous. Whenever a set of visual data matches up with a set of visual images associated with a known object, that object seems to pop out from the undifferentiated data that surround it (Kosslyn and Sussman, 1994).

This set of distinctive visual features forms a mental prototype that identifies a category of items, such as animals, plants, or otherwise interesting objects. We still use these mental templates in object-recognition tasks, such as picking blackberries, foraging for wild mushrooms, or locating some misplaced item. When language eventually did emerge, these images became tagged as “common nouns,” verbal classifications that we store in semantic memory, the cognitive system that makes available to us our general knowledge and beliefs about our world.

Though we can now express this abstract relation of individual to class using this symbolic code, this search process was, and still is, a nonverbal visual skill. Long before language, millions of years before the emergence of our hominid ancestors, animals had evolved the ability to recognize objects by accessing mental images that matched the appearance of real objects in their environment. But the internalized images used in object recognition were not enough. Just as our eye is an organ that not only focuses on figures but also scans the ground in the peripheral field, our brain processes not only imaged objects but also their positions in space—and their movements in time relative to our own positions and movements. When, for example, our prelinguistic ancestors established a camp, however briefly, they needed not only their images of what but also the image-mediated knowledge of where and when: when the gazelles went to drink at the lake, where a grove of fruit trees once glimpsed could be found again, when rival predators were on the prowl, and where the path was that led to the safety of the home camp. For this, they needed an imagination that could draw upon episodic memory to construct a mental map of this territory. As for our near relatives, the primate apes, since they plan strategies, they presumably also form mental images of situations in advance of action (Byrne, 1999).

What sort of map could prelinguistic hominids construct? We can assume with confidence that it would not be the sort of diagram that most of us are used to, a flat territory represented as though seen from the sky—back then, only birds had a “bird’s eye view.” Our abstract model, in which all objects are simultaneously present, implies that our perception of visible arrays is purely, atemporally spatial, ignoring the fact that our real-world experience of space is one of serially exploring in time a three-dimensional terrain, while remaining inside it. Rocks, trees, caves, and hidden springs being more important to hunter-gatherers than aerial distances, their mental maps of such spaces would therefore have been sequential, space–time models. Even today there are occasions when, lost in an unfamiliar locale, we find it easier to ask for a sequential map: “How do I get to Route 17M?” “You turn left at the next stop sign, go past three traffic lights, make a sharp right at the church, follow the signs to 84 West, get on it and, in about 10 minutes, you should see the exit to 17M.”

Without language, our prelinguistic ancestors could not, of course, ask or give these sorts of directions. Their mental maps were purely visuomotor. Having been there before, they followed a set of branching paths along a sequence of landmarks or followed someone who could. Once this series of turns had been learned, they could then navigate them with no more reflective effort than we expend getting around our living quarters, finding our socks, our cereal bowl, our house keys, our way up or down our block—our way, perchance, to Route 17M. Now, if we speakers had been asked by that perplexed driver for the way to Route 17M, we would find ourselves having to fall back on our prelinguistic skills. Forced to convert our prereflective visuomotor routine into a step-by-step, wordless, visualization, we would probably cue this process with some such phrase as “Let’s see … the way to Route 17M …” before we could find the words to utter it in the form of a spoken sequence.

The way they—and we, too, for the most part—would navigate an unfamiliar environment would be to parse it into a fixed series of events, e.g., turnings left, turnings right, crossing streams, climbing hills, and so forth. Later, we would be able to sum up the separate events as a whole episode and think of it as “a day’s walk out there and back again.”

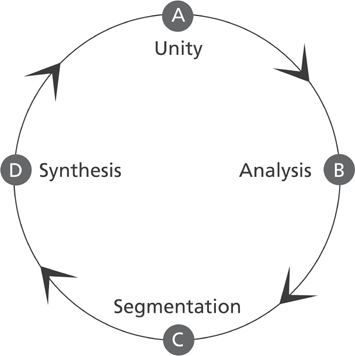

“Parsing” began as a Latin exercise in which a teacher would point to a word in a sentence and ask a pupil to identify it as a particular pars orationis, a part of speech (verb, noun, adjective, etc.), and specify its function as grammatically inflected. This parsing exercise proceeds as a cycle, as shown in figure 4.1. First, a sentence is presented as a unit (A) composed of discrete parts open to analysis. The analytic phase (B) is performed in the serial mode and ends in the complete grammatical segmentation of the sentence (C). The synthetic phase (D) begins as the parsed words are grammatically reassembled into phrases and clauses that are processed in the parallel mode. Finally the complete sentence reemerges as a meaningful unity of parts in complete parallel interrelation (A).

When the word “parsing” is applied to visual perception, it refers to the processes by which the brain takes the colors and shapes that fill the visual field and resolves this array into objects and parts of objects. That this “parsing of the visual scene into a spatial array of discrete objects” ends up producing a “unified percept of the visual world” (Milner and Goodale, 1995:5) is only half the story, however. As David Milner and Melvyn Goodale have argued, visual input systems have evolved, not for their own sake, but to assist animals’ behavioral output as they seek food and elude predators. As I proposed in chapter 2, perception and action together form the Master Dyad, essential to all sentient life forms. Since all animals, including ourselves, have perceptual systems appropriate to their particular biological niches, all animals exist in species-specific worlds, or, to use Jakob von Uexküll’s (1921) term, different Umwelte.4 An umwelt is more than a particular environment: as he defined the noun, it is the only reality that a given species has the perceptual and cognitive equipment to know. (The German word for an actual physical environment is Umgebung.) Thus, for example, the umwelts of bats, elephants, hawks, dogs, whales, bees, and humans, while partly overlapping, are each quite different in the way their perceptual systems sample and represent sound, light, smell, and other physical quanta. This idea reminds us that our specifically human reality is a biological construction formed by our unique evolutionary history and therefore merely one of an infinite set of possible umwelts. In forming our world, visual perception has been the determining factor.

I just mentioned that old folk theory of extramission. We may have abandoned that one, but we may have our own unexamined notions of visual perception. One of them, I might suggest, is the assumption that the total visual field we are aware of when we open our eyes can be accounted for by analyzing the anatomy of the eye. Were visual perception actually completed at this stage, we would not need the brain’s intricate tracery of neural paths and way stations. A more accurate explanation for the world as it visibly appears would have to begin by acknowledging that the visible umwelt is the final result of what the entire visual brain does with the photons that enter the lenses of our eyes and fall upon our retinal cells.

Figure 4.1 The parsing cycle

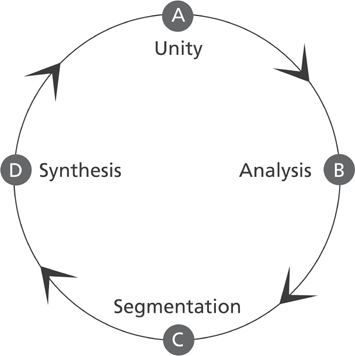

The first thing the brain does with the light patterns that excite its retinal cells is transmit these as impulses deep into itself where they are shunted off in milliseconds to be parallel-processed in a number of different areas, each specialized in extracting different kinds of information, such as color, luminance, contours, and motion (figure 4.2). While this bottom-up, feedforward process is going on, other areas of the brain are busy integrating these parsed objects into whole figures and, in a top-down, feedback operation, recognizing them in the context of prior experience. As these processes are occurring, yet other areas are adjusting the irises of the eyes to admit just the right amount of light through the pupils to the retinas, shifting the focus of the eyes in saccades (the speediest muscular reactions of which the body is capable), and repositioning the head to view objects from various angles.

Physiologists have long understood the general direction that visual information takes as it passes from each eye into the deeper recesses of the brain—how it passes along the optic nerves to the back of the brain, the visual cortex of the right and left occipital lobes, where initial representations of visual data are formed.5 But not until the 1980s was it understood how the brain subsequently processes this representation. Basing their report on their study of the visual system of the macaque monkey and accounts of patients with particular brain lesions, Leslie Ungerleider and Mortimer Mishkin (1982) identified two neural streams, or pathways, that project forward from the visual cortex. (See figure 4.2, the two arrows.) One stream culminates in the parietal lobe (the upper side region of each hemisphere), the other in the temporal lobe (the lower side region near the ear). The dorsal stream, they said, is associated with spatial perception and might be called the “where?” stream. It is this that uses mental mapping as a guide for moving about and exploring spaces. The lower, or ventral, stream, which they called the “what?” stream, is associated with object recognition (Goodale and Milner, 1992; Jeannerod, 1997, 2006) and is largely responsible for the way our species categorizes the contents of its environment. It is this stream that “transforms visual inputs into perceptual representations that embody the enduring characteristics of objects and their special relations. These representations enable us to parse the scene and to think about objects and events in the visual world” (Milner and Goodale, 2008:774). Recognizing differences that make a difference, the ventral stream thus segments the visual array into meaningful components.

Figure 4.2 The two visual streams in relation to the major areas of the brain

According to French neuroscientists Marc Jeannerod and Pierre Jacob, the parsing process of the ventral stream involves “two complementary functions: selection and recognition” (2005:302–3). As they point out, selection sorts out a complex visual array into separate objects, only after which is recognition possible. This is consistent with my biphasic parsing model (figure 4.2): the selection process corresponds to the analytic phase and the recognition process to the synthetic phase. In terming the function of the ventral stream “semantic,” they suggest how important preexisting knowledge is to visual perception in that it uses information stored in semantic memory to recognize perceived objects and understand their properties.6

For us, the semantic use of visual representations is necessarily modified by language. Unlike our prelinguistic ancestors, we have nouns to help parse our umwelt, nouns at different levels of abstraction. So, we can recognize that gray and rusty blob hopping on the lawn as a “living thing,” a “bird,” or a “robin,” and that greenish formation beyond it as a “tree,” an “evergreen,” a “conifer,” or a “pine.” Every count noun (a noun that can take a plural, e.g., “flower,” unlike a mass noun, e.g., “vegetation”) can be placed on a scale ranging from the general to the specific—from the basic-level prototype to the exemplar, or token. In the previous examples, the prototypes are “bird” and “tree,” and the exemplars are “robin” and “pine.” Despite the addition of language, our umwelt is still coded in images, as well as words (Paivio, 1971, 2007).

If the ventral stream manages the categorization of the visual array by first selecting figures and then recognizing them in the context of knowledge stored in semantic memory, we need to consider again the nature of this knowledge. According to Lawrence Barsalou, the data that constitute our knowledge of the world are grounded in the very same perceptual and motor systems through which we first experienced them and are grounded also in the thoughts and feelings that initially and over time have personalized them for us. Everything we know, whether it is a breed of dog, a fruit, a friend’s face, a melody, a speaker’s accent, a bicycle, a hammer, a swim, a dance step, even a concept such as “travel” or “justice,” is stored in its own ad hoc neural network. From each network additional branches connect to areas associated with the processing of kinds of information, including color, contour, orientation, weight, texture, pitch, volume, timbre, smell, flavor, movement, emotion, and so forth. Separate features such as these, abstracted from actual encounters with given entities, stream back into preconscious attention to constitute our recognition of them when we re-encounter them in perception or in thought. Essential to Barsalou’s theory is his assertion that our knowledge of the world is not, as narrow cognitivist doctrine would have it, stored in amodal symbols or in some “language of thought.” His counterclaim is that the brain’s semantic memory preserves a virtually infinite number of “simulators,” neural connections that, whenever circumstances require a cognitive response, become reactivated. As revealed by advanced brain-imaging technology, these simulators produce a subconscious or preconscious reenactment, a “simulation” of perception and/or action. When we are aware of this awareness, we tend to explain it by saying that we “associate” x, y, and z with that entity—and it is often some elusive emotional tone, or aura, that we identify. When these abstracted traces merge on a conscious level, we experience them not as separate strands but as a sheaf of features, a single concretized representation, a fully formed mental image (Barsalou, 2009:1281).

In formulating his simulation theory, Barsalou (2008) built on the ecological psychology of James J. Gibson, the work of mental image psychologists such as Allan Paivio, Roger Shepard, and Stephen Kosslyn, as well as on the recent findings of mirror neuron researchers. Not surprisingly, cognitive linguists have become intrigued by the implications of this simulation theory (Richardson and Matlock, 2007). As for the relevance of visual simulation to language and cognitive poetics, I will have more to say about that in later chapters. For now, though, I will return to the question of how initial visual input is processed.

While their peers have generally regarded Ungerleider and Mishkin’s findings as groundbreaking, some have questioned their interpretations of the two streams. Prominent among these latter have been David Milner of the University of St. Andrews, Scotland, and Melvin Goodale of the University of Western Ontario. In the early 1980s Milner had begun studying a patient (D. F.) who had suffered a severe brain injury that prevented her from recognizing objects. To his surprise, Milner found that, despite this impairment, she was able to perform visually guided tasks involving objects. Apparently, some part of her visual system still recognized different shapes, although she had no awareness she was making such distinctions. Goodale had earlier researched issues involved in eye–hand coordination in relation to the asymmetries of the brain’s hemispheres. Both he and Milner had become fascinated by the implications of the two-stream theory. Very much in the tradition of William James and James J. Gibson, they regarded vision as an evolved means of acting upon the world, not simply forming mental representations of it. Hence their stress on visuomotor functions and the title of their 1995 book, The Visual Brain in Action.

In the latter study they outlined the research that had led them to revise Ungerleider and Mishkin’s model, concluding that, yes, the ventral stream did access representations that could be consciously used to recognize objects, but that the function of the dorsal stream was to guide actions, such as reaching, grasping, pointing, and locomotion, in the context of objects. This stream, which, they said, should not be called the “where?” but the “how?” stream, speedily receives information from the retinas in the form of saccade-driven fixations, a series of momentary “snapshots” that it uses to update the viewer’s spatial relation to objects in the visual field. These images, held briefly in working memory, constitute what is called the “optic flow.” Unlike the ventral stream, which relies on central vision to select and recognize objects of interest, the dorsal stream has also available to it the full peripheral field. So, what it lacks in acuity, color discrimination, and consciously accessible knowledge stored in semantic memory, it makes up for in sensitivity to peripheral motion and in the speed and skill with which it can guide one’s movement within one’s immediate environment. And, as the case of D. F. strongly indicated, the dorsal stream guides the subject’s actions while concealing its own actions. This is not to say that the dorsal stream is wholly dissociated from other regions of the brain or that the overt actions it oversees are subconscious: it simply means that its own visual actions are normally performed below the threshold of consciousness (Wright and Ward, 2008; Braun and Sagi, 1990; Bullier, 2003).

These two streams represent a collaboration of narrow, sharply defined, centralized attention with broad, diffuse, peripheralized awareness. In this division of labor the ventral stream, specializing in fine-grained perceptual representations, selects and recognizes figures, while the dorsal stream, specializing in coordinated action, calculates the relative position of agent and objects in the visual ground. Once again we have an interactive duality that displays the familiar dyadic pattern.

As visual processing subsystems, both streams connect us with our light-suffused umwelt, but, as Milner and Goodale have observed, they do so using different frames of spatial reference. From their study of patients who had been left with only one functioning stream,7 they found that the ventral stream uses an allocentric frame of reference; i.e., it recognizes objects as positioned in spatial relation to one another—not to the viewer. As befits a system tasked with object recognition, the allocentric frame represents an object as viewer independent, a token of an enduring type; in accordance to the principle of perceptual constancy, it presupposes that an object’s actual size, shape, and color remain unchanged by distance, orientation, or intensity of light. On the other hand, the dorsal stream, as “vision for action,” places objects in an egocentric frame of reference: from the viewer’s central position, the location of objects is calculated in terms of left/right, higher/lower, front/back, near/far, etc., solely in relation to him- or herself.8 It also adheres to the principle of perceptual constancy, but, while the ventral discounts inconstancies, the dorsal stream treats them as vitally important: apparent size change, for example, can indicate movement toward or away from the viewer, initiated either by the viewer or the object.

While the ventral stream, being “other-centered,” views objects as one might through a windowpane, as separable figures arranged on a quasi-two-dimensional ground, the dorsal stream surveys a world of objects and the ground that wholly surrounds the viewer. At the same time, using the third dimension of depth, it calculates the distance between an object and one’s whole body, a single part (such as one’s outstretched hand), or a grasped instrument (such as a long stick). As we move ahead toward our goal, its peripheral capacity permits the dorsal stream to deal not only with the target object but also to gauge our distance from incidental obstacles that might lie in the way or otherwise interfere with our progress. This computation is achieved through motion parallax, for, as we move, the fixed objects either side of us will seem to move past us at different rates of speed: the nearer will seem faster than the farther. This index of relative distance, by the way, works perfectly well in the monocular vision that characterizes the extreme left and right peripheral fringe, since the rod cells of the retinas are just as sensitive to relative motion as they are to the motion of an object within a stable setting.9

These two complementary streams, working together as an optical dyad, construct our visible umwelt by resolving it into those representational dyads, figures and grounds. Every object that interests us out there in allocentric space, once it is selected and recognized as this-or-that by our ventral stream, becomes a closed figure, a gestalt, set forth by the ground that surrounds it. An exaggeratedly selective version of this vision is perhaps what William Blake was referring to when he said: “[M]an has closed himself up, till he sees all things through the narrow chinks of his cavern” (The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, plate 14). But, while an object-as-figure is closed on all sides, a ground is open on all sides, for, had it closure, ground would be figure. From the egocentric perspective that the dorsal stream maintains, the visual “everything” that surrounds the viewer on all sides is only seemingly bounded by the oval visual field with its progressively dim peripheral fringe. If we saw the world only with our dorsal stream, we would find ourselves grounded in boundlessness and, as Blake promised, “everything would appear to [us] as it is—infinite” (ibid.).

The two streams, each with its own spatial frame of reference, hold important implications for any theory of imagination. As a simulation of visual perception, imagination must project its iconic representations upon either an allocentric or an egocentric frame. When we simulate the function of the ventral stream, we imagine an object “out there,” in spatial relation to other objects. This observer-neutral allocentric projection changes radically when we adopt the dorsal stream perspective. Now we seem to enter the field of imagined objects as we actively engage with these mind-generated images, rather like the way we encounter figures in our dreams.

The ventral and the dorsal streams operate within yet another, larger complementary pair, the right and left hemispheres of the brain. Though each of the latter presents an anatomical mirror image of the other, each has different specialties. Over their 60 million years of evolution, the primates have been ambidextrous except for the last 2.5 million years, when one branch came to favor the left hemisphere (controlling the right side) when performing finely tuned manual tasks, a tendency that has become a defining feature of Homo, the “lopsided ape,” as Michael Corballis (1993) dubbed him. While the right hemisphere continued to take in and organize sensory information from the world about it, the left began more and more to focus on details—particular sounds, distinctive visual shapes and colors, ways of recognizing and manipulating objects and of fashioning objects to modify other objects. Undoubtedly the right hemisphere retrofitted its own circuitry over time, but its operations did not compete with the left in narrowly focused perception and finely tuned motor control.

As humans gradually incorporated what Dual-Process Theory calls “System 2” skills, it also retained their older “System 1” skills, and the dyadic pattern that was the result of this collaboration slowly restructured the bilateral brain. The parallel–serial difference became more distinct, the right hemisphere specializing in parallel processing, the left in serial processing. Being adept at integrating parallel input, the right perceives the world holistically and, adept at parallel output, governs motor multitasking. The left hemisphere, specializing in serial input, perceives the world part by part, object by object, and, adapted for serial output, came to oversee step-by-step search, tool use, and, eventually, language.

This division of labor is also evident in visual perception. Figure 4.2 represented the left hemisphere only, but we must not forget that the right hemisphere has its own V1 and its own dorsal and ventral processing streams that function in concert with the left. Each hemisphere has become specialized in a different visual function, the dorsal stream of the right hemisphere in visually guiding locomotion in egocentric space, the ventral stream of the left hemisphere in the visual selection and recognition of objects framed in allocentric space.

If we found ourselves transported back in time 1 million years to visit our early Homo erectus ancestors, we might anticipate this or that response to this or that interaction and would likely be disappointed, even dismayed, by their choice of behavior. But if we reset the controls on our time machine to 100,000 years ago and visited their East African descendants, we might find them, with or without spoken language, somewhat more amenable—more like us. They would look us in the eye, smile, offer us food and drink, and protect us while we were with them. We would conclude that, somewhere along the way, Homo had become sapient.

The traits that made us what we think of as “human,” I suggest, coevolved with our visual brain. Millions of years before our recognizably sapient ancestors first appeared, primates had evolved a visual system that became their most dependable link with one another and with the world at large. Over time, other cognitive skills emerged, each based on visuomotor coordination.

An early set of primate adaptations was supported by the mirror neuron system (MNS). This neural hook-up permits a visual perception, mediated by the ventral stream and allocentrically framed, to stimulate motor neurons in the viewer’s brain to replicate this action in an egocentrically framed simulation mediated by the dorsal stream—all this without overt action on the part of the viewer (Hesslow, 2002). This wholly internal coordination of the two visual streams, each with its own spatial frame of reference, one allocentric, the other egocentric, must have played an important part in the evolution of theory of mind, the belief that others share some of the same mental states as oneself. The two visual streams and the mirror neuron system would also have facilitated mind reading, the interpretation of others’ covert intentions, and empathy, the recognition that others share with us a common set of needs and desires and that social cohesion can sometimes be improved by satisfying them. These visually mediated social skills would have been within the capacity of the bipedal primates that preceded our first human ancestors. “Lucy” (ca. 3.2 mya) and her band of Australopithecines would doubtlessly be capable of theory of mind, mind reading, and empathy. This suite of skills, set in place during the episodic stage, would have been improved upon during the mimetic stage: that community of tool-making Homo erectus that we imagined visiting some 1 million years ago would have used them in maintaining their hunter-gatherer culture.

Among the traits that undoubtedly increased in importance during the mimetic stage must have been shared gaze, the use of the eyes to induce others to gaze in the same direction. We suspect it must have been important because our hominid ancestors evolved white scleras surrounding their irises, a directional indicator that is unique among primates. Since the sclera is usually most visible to the right and left of the iris and pupil, its horizontal shifts can be significant for cooperative land-roving hunters and gatherers. For objects on a vertical scale, head movement and pointing could also be put to use. Thus, the eyes that in mind reading were used to pick up covert intentions could now become the means of sending overt messages (Kobayashi and Kohshima, 2001; De Waal, 1982).

The availability of stored knowledge accessed as image schemas is, as we have seen, a requisite for ventral stream processing. The use of an image, stored in semantic memory and allocentrically assembled as a template, speeds the parsing of visual arrays via selection and recognition (Kosslyn and Sussman, 1994:1035–36). When coordinated with egocentrically framed locomotion, mental imagery makes goal-directed search possible, and mental mapping considerably increases its possibility of success. As I mentioned earlier, the typical mental map is a serial network of landmarks, each a recognizable figure that, once noted, recedes into the visual ground. We now have come to regard landmarks and their targets as allocentrically framed (i.e., selected and recognized) by the ventral stream. But we also understand that, as we direct our gaze and movements toward them, landmarks are also framed egocentrically by the dorsal stream. In our serial navigation through actual three-dimensional space, these landmarks serve us best at the very moment that we turn our gaze-centered, forward-moving bodies away from them and they slide off in the opposite direction into our peripheral field.

Tool use, especially the use of tools manufactured for particular tasks, was also built on the perception/action scaffolding of the primate visual system. As the two serial functions of the ventral stream, selection and recognition normally flow seamlessly from one to the other, but in tool use they are kept quite separate. Recognition may occur when choosing a tool and finding appropriate raw material. It may also occur at intervals during the production of an artifact when one stops to compare the object being shaped to a mental image of it or to a material prototype, as well as at the end when one compares the completed product with such models. This relation of artifact to prototype produces an object-to-object (allocentric) frame of reference. But during the act of tool use, the only function of the ventral stream is selection, i.e., the narrowed focus of central vision affixed to a figure—in this case the object being shaped.

In tool use it is the dorsal stream, typically in the dominant left hemisphere, that plays the major role. Here skillful action, enhanced as it is by procedural memory, tends to operate within the worker’s peripersonal foreground or the peripheral visual field. As Milner and Goodale (1995) maintain, the dorsal stream is functionally unconscious and does not require focal attention—it is in fact inhibited by such attention. Performed within a strictly egocentric frame of reference, tool use requires automatic three-dimensional calculations of the location of the object not only in horizontal and vertical coordinates but also in depth, i.e., the distance between the tool (say, the hammer) from the object (say, the head of the nail). In short, as a serial motor activity, tool use requires the parallel coordination of both visual streams, the ventral focusing on the raw material and the dorsal guiding the action of the tool user.

The visual system also provided the preadaptive means for the evolution of what are often designated the “higher cognitive” skills. Paramount among these is imagination, the voluntary manipulation of mental representations, detached from outward perception and action. For scores of millions of years our mammalian ancestors used images to support and augment perception (Kosslyn and Sussman, 1994). Stored in semantic memory, the features from which whole images are formed could only be activated by online external stimuli. Mental images could be put to other uses, however, and we appear to be the one species able to do so—namely, to access and manipulate such simulations of perception, deploy them in an inner theater of virtual reality, and with them carry on that uniquely human offline activity we know as “thought” (Suddendorf, 1999).

The special character of image-mediated thought is its independence from the spatiotemporal present. By means of it, we can visualize persons and settings that lie beyond our current perceptions. Accessing the contents of semantic memory, we can project our thought into the known past, the spatially elsewhere present, and the reasonably predictable future. But without language to mediate these projections, it would seem extremely difficult to sustain image-mediated thought about facts not personally experienced, such as events that happened before we were born or may happen to future generations. Even we, who can entertain such thoughts when considering the past and the future, feel more comfortable projecting our thoughts into our own lived past and our potentially livable future. In short, mental time travel for us is usually experienced as a simulated episode temporally labeled as past or future but having the visuomotor character of an actual present experienced from within our own egocentric frame of reference.

Just as semantic memory could become a resource for the solitary thinker, so too could episodic memory. The latter store of time- and place-specific experiences are the result of event parsing, the binding of a series of part-perceptions into a unit that we tag as a separate episode. Since an episode, if it has been stored in long-term memory, must have made an impression on us and aroused us, it is also tagged with a particular emotional tone. When we retrieve it, we place it in an egocentric perspective, one in which we seem to re-experience events in a particular place and time (Tulving, 1983). This involves a sequencing of mental representations, which, like all serial tasks, requires a degree of effort.

Another reason why retrieving episodic memories is effortful may be the fact that the dorsal stream, which mediates three-dimensional egocentric perception for action, is incapable of forming clear, recognizable, enduring images—this is the work of the ventral stream. Though it takes its egocentric frame of reference from the dorsal stream, episodic memory must rely for the detail of its visual representations on semantic memory as mediated by the ventral stream. When we recall an event from our past, its images are recoded in the ventral format and now viewed as discrete figures in a set sequence. What had been initially experienced as an ongoing, wide-angled, parallel-featured episode is now, except for its affective tone, thoroughly serial. The brain, in short, must translate imagery from the egocentric frame of the dorsal into the allocentric frame of the ventral. As with most translations, something is lost and something else inserted. For this reason, in a court of law, eyewitness testimony and “recovered memories” are routinely adjudged less trustworthy than expert testimony and forensic evidence. Current research into the neural mechanics of episodic memory holds profound implications for the poetics of narrative point of view and imagination, a topic I will return to in later chapters (P. Byrne et al., 2007; Gomez et al., 2009).

Complementarity—The Limits of Human Knowledge?

In the 1990s, the phrase “massively parallel” became a shibboleth among those who were then discovering the similarities between the brain and the computer as information processors.10 Serial processing, by contrast, connotes a rather unspectacular plodding along of impulses or thoughts. However, serial plodding is sometimes unavoidable, when, for example, one learns a skill, finds one’s way in an unfamiliar territory, or encounters new ideas. Since it must be efficient in both modes, the brain might be more accurately described as “massively complementary.” This is especially true of visual cognition, which is possible only through the complementary (dyadic) relationship of figure to ground, of ventral to dorsal streams, and of allocentric to egocentric frames of reference. Briefly summarized:

1. Figure and ground discrimination is essential to the process of selecting, prior to recognizing, the objects we encounter. The visual system uses the serial mode when it performs saccade-driven foveal fixations to determine the boundaries of an object. At the same time, it uses the parallel mode as it preattentively monitors the objects that lie in its peripheral field. These objects belong to the ground by virtue of the fact that their dissociation from the figure defines that object. In other words, the ground generates the figure and the figure generates the ground.

2. The ventral and dorsal streams are likewise complementary in their use of serial and parallel modes. The ventral cannot broadly scan an array and instantly recognize differences. Instead, it must depend on its sharply focused central vision to fixate on the details that mark each object’s boundaries before it can select that object from its ground. Moreover, since it must also depend on semantic memory to ascertain the identity of these objects, it must sometimes double-check itself, a further serial process. The dorsal stream, receiving generous input from the peripheral field of the retinas, oversees movement through space, a process that involves the parallel cognition of objects, standing or moving, and of the moving body of the viewer. By moving toward objects, it clarifies them, thus serving the purpose of the ventral stream, i.e., the selection and recognition of those objects. Separated as these two visual systems are, they do share information and, different as their functions are, they do, when necessary, actively assist one another. They are, in the words of Milner and Goodale, “different and complementary” (1995:29; see also 1995:53, 177, and 202).

3. The allocentric and egocentric frames of reference are the two very different ways we have to locate ourselves and other things in our visible umwelt. The allocentric utilizes the serial mode and does so in alignment with figural vision and the ventral stream. To help us locate where we are relative to our goal, the ventral maps the relation between objects as landmarks. At the same time that it is performing this sort of computation, its complementary stream, the dorsal, will be deriving egocentric information from the same data. In filmic terms, the allocentric combines long shots and close-ups, while the egocentric represents a scene as though taken by a hand-held camera and instantly fast-cut. The egocentric frame needs to be parallel, massively parallel, because, as the viewer moves, it must accommodate objects at different distances in a wide-angled visual periphery. Yet these two frames of reference not only share usable information with one another but do so without ever revealing to the viewer how radically different their separate versions of the world really are.

When we humans began to contemplate ourselves and our world, we did so using neuroanatomy developed over many long ages of vertebrate evolution. This bilateral body, culminating in a bone-encased sensorium, that is in turn wired into a bi-hemispheric circuitry of nerve cells, dictated the conditions under which we came to know reality—our reality, our umwelt. Having inherited this body plan, it seems inevitable that our species would have construed this reality in terms of paired opposites. It still “makes sense” to us to parse an issue “on the one hand” and “on the other hand,” and whenever we hear a dichotomy or a polarity offered to clarify a complex or murky state of affairs, it “sounds right,” at least at first. I will not claim that bilaterality is the only reason why we tend to think dualistically, but I do assume that one underlying set of opposites, the parallel and serial modes, has furnished us a template that we readily project onto any mass of initially perplexing data that comes our way.

For starters, consider space and time. Space, as it is generally understood, is that entity in which separate objects coexist in parallel at a single moment of time. Time—on the other hand—is that entity or process in which discrete actions or events occur serially in consecutive moments. We may be familiar with the theory that time is the fourth dimension of space, but for most of us this Einsteinian definition of space-time is far easier to say than to conceptualize. Instead, we live our lives as though we still believed with Isaac Newton that space and time are separate and absolute entities. These two concepts, which Kant called a priori intuitions, to us seem so self-evidently real that we entrust to them the governance of our daily lives. But, real or not, these two main coordinates of our human umwelt are, I hypothesize, simply the brain’s dyadic structures, its parallelism and seriality writ large.

Sometimes the parallel/serial dichotomy becomes an either/or issue and complementarity seems completely out of the question. Consider the early-twentieth-century controversy between the neuroanatomists who held that the central nervous system communicates by continuous networks of diffuse, filamentary nerve cells (the reticular theory, championed by Camillo Golgi) and those who maintained that nerve cells are separate and communicate by electrical charges that leap across gaps, called synapses (the later neuronal theory, championed by Santiago Ramón y Cajal). Both sides in that debate agreed on one thing only: the reticular model, essentially parallel, could never be reconciled with the neuronal model with its serial pathways. Consider, too, the more recent controversy between those who see the brain as a set of modules, each dedicated to a single cognitive function, and those who stress the brain’s “massively parallel” connectedness. Also, consider how those two terms, “pathway” and “stream,” have been applied since the early 1980s to the dorsal and ventral projections: “pathway” implies a conduit for serial locomotion, while “stream” implies a continuous movement of parallel contents.11

Then there was Niels Bohr, the scientist who in the late 1920s had introduced the concept of “complementarity.” Energy, he maintained, behaves equally as a wave and as a series of particles, a claim that provoked, at the time, a mixture of admiration and dismay from fellow physicists, including Heisenberg and Einstein. On the evening of November 17, 1962, in a taped interview with Thomas Kuhn and several others, Bohr confessed how influential to his complementarity theory had been William James’s theory of consciousness. The 77-year-old physicist then recalled how Edgar Rubin, the Danish Gestalt psychologist and his second cousin, had recommended that he read James, especially chapter IX of The Principles of Psychology, and he promised his guests that the next day “we shall really go into these things.” That promise he did not keep, for the next day he unexpectedly died (Feuer, 1974:126).

What precisely had the father of quantum physics learned from the father of modern psychology? We can only speculate on that, but it is interesting to note that in that chapter James revealed that he, too, had long struggled with two similarly competing paradigms, one parallel and the other serial. For most of the nineteenth century, the dominant philosophy of consciousness was still associationism, as Hobbes, Locke, Hume, and Hartley had formulated it. According to this doctrine, thought was constructed out of “simple ideas,” a kind of “mental atoms and molecules” (James, 1890/1950:231). This James rejects as not only empirically groundless but also as inconsistent with his introspected knowledge of thought processes: “Consciousness … does not appear to itself chopped up in bits. Such words as ‘chain’ or ‘train’ do not describe it fitly as it presents itself in the first instance. It is nothing jointed; it flows. A ‘river’ or a ‘stream’ are the metaphors by which it is most naturally described. In talking of it hereafter, let us call it the stream of thought, of consciousness, or of subjective life” (ibid.:240).

Soon afterward, however, James acknowledges that speed of processing changes the apparent behavior of thought. This stream, when it moves at a slow, stable rate, exhibits its “substantive parts,” but “when rapid, we are aware of a passage, a relation, a transition from it, or between it and something else. As we take, in fact, a general view of the wonderful stream of our consciousness, what strikes us first is this different pace of its parts.” This leads him to switch his metaphor. “Like a bird’s life, it seems to be made of an alternation of flights and perchings…. The resting-places are usually occupied by sensorial imaginations of some sort, whose peculiarity is that they can be held before the mind for an indefinite time, and contemplated without changing; the places of flight are filled with thoughts of relations, static or dynamic, that for the most part obtain between the matters contemplated in the periods of comparative rest” (ibid.:244). This second metaphor may not be the associationists’ sequential “chain” or “train of thought,” but, being consecutive, it is no less serial—no less serial than the ocular saccades and fixations that these “flights and perchings” so closely resemble. Together, James’s stream and bird-flight metaphors form a complementarity that Bohr must have recognized as a pattern consistent with his own wave/particle complementarity (ibid.:244).12

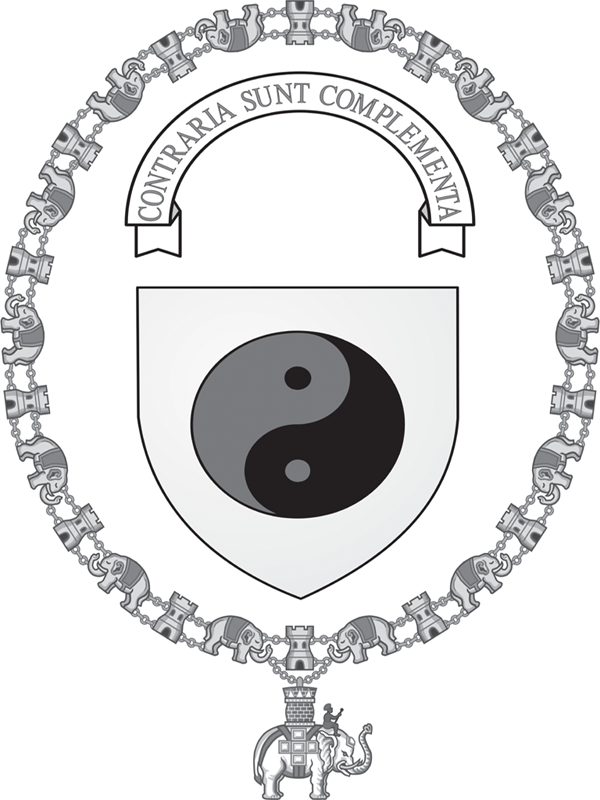

In 1947, when Bohr was honored by the Danish government with admission into the prestigious Order of the Elephant, he was required to place his coat of arms in Frederiksborg Castle. Having no family crest, he had to invent one. He chose for his motto the Latin phrase “contraria sunt complementa” (opposites are complements) and for his image the Taijitu (T’ai-Chi T’u), representing the two opposite and complementary principles, the yin and the yang (figure 4.3). This pair, enclosed in a circle, have an internally shared common border, a fact that constrains the viewer to assign figural status first to one and then to the other (Arnheim, 1961). As his cousin, Edgar Rubin, had proved with his well-known vase/face experiment, when forms share a common border, each becomes a “reciprocal” image, alternately perceived as figure and as ground—a graphic demonstration of complementarity.

Figure 4.3 Niels Bohr’s coat of arms

(From Wikimedia Commons, created by GJo, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The question remains: Is complementarity real or phenomenal? If it is real and not a product of clashing metaphors, then the nature of things is a marriage of radical opposites. Bohr’s suggestion that this might be true was what had provoked Einstein to remark that, as far as he was concerned, God did not play dice. Bohr acknowledged the paradox but also understood that, when it comes to the ultimate nature of things, human knowledge must sometimes be content with the phenomenal. The most objective cosmology that our subjective, all-too-human brain is capable of conceptualizing may, after all, be simply another dyadically constructed representation of our human umwelt.