Although one can argue to some extent that the culture evinced through the Indo-Persian literature continued until the beginning of the British Raj in 1858, the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries marked a time of enormous political turbulence and musical change. After the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, the Mughal Empire began to crumble. Petty wars of succession and puppet emperors led eventually to a power void that the British gradually filled. Artistic patronage from the imperial court weakened and there was widespread migration as musicians and dancers sought support from the increasingly autonomous regional courts including Bhopal, Rampur and particularly Lucknow. In the north-central principality of Awadh, a short succession of wealthy and cultured princes culminating with the pleasure-loving aesthete, Wajid ‘Ali Shah, created what is often considered as the last flowering of Mughal culture. Contemporary musicians and dancers certainly thought so, and significant migration to Awadh during this time made its capital, Lucknow, a centre of artistic ferment for over half a century. Yet not all patronage was indigenous, and the growing presence of the British as trade partner, economic and military power, and eventually as colonial occupier also affected performance practice and performers during this period.

There is a wealth of indigenous and colonial documentation on dance practice from this time. By the late nineteenth century, early musicologists were beginning to add to the observations of the Orientalists with books on Indian music that included contemporary observations. A group of indigenous treatises from the mid-nineteenth century documented music and dance from what was seen as the end of an artistic era in Lucknow at the same time as the British were producing increasingly detailed census reports and attendant ‘Tribes and Castes’ volumes. The curious European travellers also provided history with 150 years of travelogues, personal letters and diaries. Finally, there is a detailed iconographic record including both Indian and European material and offering some of the most consistent and valuable information from the late eighteenth through the nineteenth centuries. Combining an analysis of this visual record with the documentation available in the indigenous treatises and colonial travel writings provides a convincing and multi-faceted picture of dance during this period.

Although the abundance of paintings and early photos of music and dance from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in North India forms an important part of the documentation of music and dance, most books, websites and promotional material about kathak use these images as colourful illustrations with little if any systematic analysis of their content. Ethnomusicologists seem to have a tacit agreement that a universal method for iconography in historical research should not be pursued, but rather that the methodologies of Western art history (see below) can be tailored to take the types of visual sources and the aesthetics of the particular culture into consideration (Seebass 1992). In the case of kathak, a careful examination of the iconography of North Indian dance seems once again overdue, not only because of the information it contains about the dances of the past, but also because, like much of the information in the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century literary sources, it has been largely passed over in favour of ancient sculptures (as in Narayan 1998). Furthermore, my own curiosity about kathak’s past began in large part through a study of dance images and their comparison with written and oral historical sources. I began my inquiry by learning the methodology developed by art historian Erwin Panofsky (1939), which has been adopted and adapted by many researchers in all fields of performance iconography (de Vries 1999 and Seebass 1992). With some further adaptations, I found this tripartite approach of pre-iconographic, iconographic and iconological analysis both useful and enlightening and, although I have since examined many more images, this initial study is worth presenting in some methodological and statistical detail.

Panofsky’s ‘pre-iconographic description’ seeks to describe each picture’s formal qualities. This is straightforward work, consisting merely of observations and their arrangement into statistical tables and charts. As a first step in this inquiry, my pre-iconographic work included identifying which available pictures from North India dating between 1700 and 1900 contained dancers, and then categorizing these images according to context or performance venue, subject matter, number of dancers and musicians, perceived movement patterns and the dancer’s placement within the painting’s composition. My investigation included hundreds of prints of Persian, Mughal and Indian miniature paintings and scores more European reproductions. I focused on paintings containing dancers produced in North India between 1700 and 1910 as Bonnie Wade’s colourful publication, Imaging Sound (1998), undertakes a study of Mughal miniatures produced until the death of Aurangzeb in 1707 and provides many observations based on this visual record. As the early data explored in the previous chapter shows only skeletal evidence of kathak-like dances, I began my search where Wade’s book ends, taking my investigation up to the changes in technology, society and the status of music and dance that marked the turn of the twentieth century.

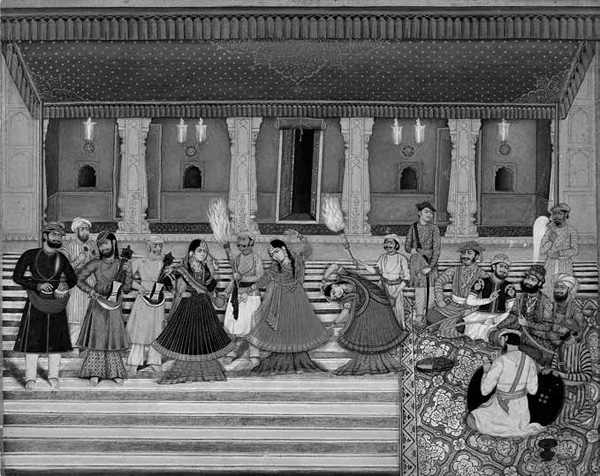

Eighty-eight pictures in the initial study met these criteria, allowing detailed analysis. Within these, eight paintings were various mythological scenes, most commonly Radha-Krishna vignettes or scenes depicting Krishna’s circle dance with the milkmaids or gopīs. Fourteen pictures were portraits of dancers, usually identified by name. This genre is paralleled in the photographic record, as for example in the album The Beauties of Lucknow (1874). Eight other pictures contained small groups of figures, usually both dancers and musicians, without any background or context. Two scenes depicted village festivals. Fifty-six paintings were illustrations of performances in court scenes, princely processions and salon or party settings, and two of the mythological paintings also depicted court scenes, peopling secular settings with celestial beings. All but six or seven paintings contained exclusively female dancers and four paintings showed dancing boys. Only six paintings showed groups of four or more dancers and in the remaining scenes or groups, there were 29 paintings containing groups of two or three female dancers and 34 with soloists. Only seven paintings clearly did not contain accompanying musicians and in seven others, the accompanists were all female. The rest of the pictures showed exclusively male accompanists, most often trios or quartets. Thus one can generalize that the majority of paintings examined were court or salon scenes containing up to three female dancers usually accompanied by a small ensemble of male musicians.

Figure 5.1 A nobleman and his guests watching a nautch, ca. 1830, India, Delhi. Robert and Lisa Sainsbury Collection, University of East Anglia, UK. Photographer: James Austin

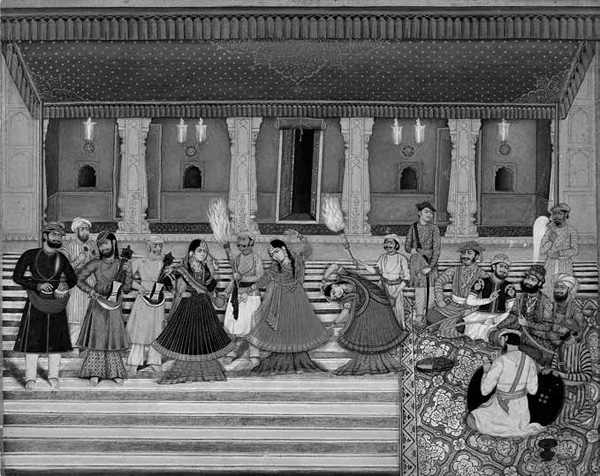

Omitting the circle dances and portraits, 67 figures (64 women and three boys) were in positions that could be compared to today’s kathak dance. Slightly over half of these figures were in postures with one arm raised or extended forward with the other extended to the side, placed on the hip or holding the performer’s skirt or veil in some way. Two figures were performing salām, and two others had their right hands across their chests. Twenty-two figures performed gestures with their veils, drawing them over their heads, or holding one end out to the side (see Figures 5.2, 5.3 and 5.4). Eleven dancers performed similar gestures with their skirts, with seven in particular pulling the folds of very full skirts out laterally right up to their head level (see Figure 5.4). Four dancers were depicted seated and making gestures with their hands (see Figure 5.5) and two others were shown seemingly executing slow turns. A number of the dancers had slightly flared skirts, but it is unclear whether this indicated movement. It was difficult to identify discernible footwork; occasionally a figure had one foot crossed over or behind the other, but most dancers were either still or seemed simply to be walking.

Figure 5.2 ‘A Nautch’ from Charles d’Oyly’s Scrapbook, 1828–1831. © The British Library Board. Shelfmark P2481

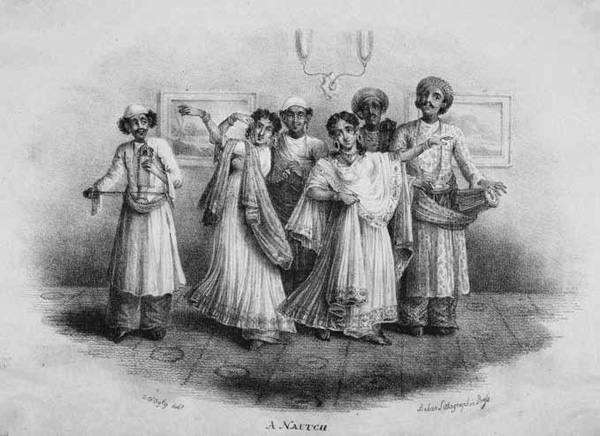

Figure 5.3 ‘Nautch or Dancing Girls’ from The Delhie Book, 1844. © The British Library Board. Shelfmark Add.Or 5475

Figure 5.4 ‘Three Dancing Girls of Hindostan’ by Mrs Belnos, 1832. © The British Library Board. Shelfmark LD.31.b.1758

Figure 5.5 ‘Nautch at Cawnpoor’ from Captain Smith’s Journal, 1830. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

This survey of postures and genders becomes much more meaningful when compared with the other evidence available. This is ‘iconographical analysis’, which places the images within their stylistic context, taking artistic and cultural conventions, historical information and the circumstances surrounding the paintings’ production into consideration. The pictures’ graphic content needs to be verified through external sources before it can be accepted as documentary material (Katritzky 1999: 68). Recognizing the styles of painting and connecting them with the flow of Indian history provides important contextual information about both the various performance environments and the circumstances of the paintings’ production. In my initial project, the iconographic stage began with an investigation of secondary sources in both the history of India and of Indian art. I then rearranged the pictures into stylistic categories and compared the paintings’ content across stylistic boundaries. The analysis of the content in comparison with the contemporary historical descriptions found in the travel writings and treatises formed the final part of the study, reaching far beyond my doctoral work as I uncovered previously untranslated treatises and was able to examine further images.

As discussed in the previous chapter, successive waves of migrants and invaders from West and Central Asia had added to the South Asian cultural mosaic since at least the twelfth century, culminating in the rule of the first ‘great’ Mughal emperor, Akbar (r. 1556–1605). The Muslims brought with them not only West Asian music and dance traditions, but also the Persian practice of illumination. Pre-Mughal Indian painters had used first palm leaves then paper, which was introduced in the fourteenth century, for their brightly coloured and opulent style. The almond-eyed and highly stylized figures in these rectangular paintings were heavily outlined against flat, symbolic portrayals of nature (see Chakraverty 1996). Persian tradition, on the other hand, combined elegant calligraphic techniques with an interest in portraiture in artistic albums of illuminations and calligraphy called muraqqa‘s. Importing the techniques and traditions of Persian artists, Akbar not only patronized the art of illumination, but set up an imperial atelier of painters and calligraphers to produce illustrated manuscripts that documented his achievements and reinforced his power. Although the vigorous crowd scenes of Akbar’s time change to an emphasis on portraits and nature scenes during the subsequent reigns of Jahangir and Shah Jahan, a substantial and striking visual record of the days of these ‘Great Mughals’ remains (Wade 1998). Akbar’s great-grandson Aurangzeb (r. 1658–1707), however, in his desire to conform more strictly to the orthodox Islamic law of the sharī’a, ended imperial patronage of the atelier with its twin artistic functions of chronicle composition and illustration (Richards 1993: 173; see also Brown 2003).

After the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, the empire and its centralized traditions began to decline allowing regional courts to flourish. Mughal aristocratic culture continued at the courts of Muslim and eventually North Indian Hindu princes and nobles. The shift of power to smaller courts is in part documented in the colourful Rajput style of painting. These Hindu warrior-princes, concentrated in what is now Rajasthan and the Panjab, had fought, married, paid tribute to and co-existed with their Mughal conquerors for a few hundred years. Although their owners were heirs to vigorous cultural and artistic traditions, by the beginning of the eighteenth century Rajput palaces had absorbed such Mughal characteristics as pavilions, courtyards, gardens and darbār halls. Mughal fashion was also followed in court dress and manners (Beach 1992: 174). Rajput painting, although retaining distinctive use of colour and lack of perspective, gradually adopted some of the subtlety of Mughal style and also some of its secular subjects. Before 1700, Rajput paintings illustrated primarily symbolic and religious subjects: scenes of gods and goddesses, illustrations for the Hindu epics and the Rāgamala collections (studied in Flora 1987). In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries court scenes abound (see Figure 5.6). Nineteen of the paintings chosen for this study were Rajput court scenes, compared to only seven in the Mughal style. Rajput style is recognizable through its conscious lack of perspective, its strong colours and bold use of line and form. But nevertheless it absorbed and traded stylistic influences with Mughal art. Indeed, by the mid-eighteenth century, the two styles become less and less distinctive, sharing subject matter, composition and even artists (Beach 1992: 178).

Figure 5.6 Raja Ajit Singh of Bundi, ca. 1780. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

One further influence and patron of Indian art remains. Since initial contact through the spice and silk trade routes, Europeans had become a constant presence in Indian court and commercial circles. Akbar, in his search for knowledge and culture, had invited Portuguese missionaries to debate with Hindu, Islamic and Buddhist scholars at his court. Mughal artists made studies and copies of European paintings, and adapted some of the ideas of perspective into their works. Rajput artists created a few paintings completely in shades of grey, a surprising departure from their usual style, in imitation of European prints (Beach 1992: 175). But as European, particularly British, commercial and administrative power grew, a new style of Indian painting emerged. Indian artists had been experimenting with European artistic style and technique for a few hundred years. In the nineteenth century, however, the interests of British patrons and purchasers gave rise to what is most often called ‘Company Style’: an Indian approach to figures and colours with a touch of European realism, perspective, and scale (see Figures 5.3 and 5.7). There is a range of style, composition and subject matter in these paintings and it is important to realize that the change in Indian art at this time reflected not a sudden exposure to new ideas and techniques from the annexing entrepreneurs but a change in patronage. The new purchasers were interested in the exoticism of the sub-continent, but presented in more familiar visual terms than offered by Rajput or Mughal styles. Indian painters, finding an additional source of patronage to the increasingly powerless courts, readily obliged.

European commercial expansion and British Imperial annexation brought one further approach to the visual record of India. As the colonies grew and travel became easier, European artists, both professional and amateur, increasingly visited India. Their works represent Indian lives and landscapes in oils, watercolours, lithographs, engravings and pencil sketches. There is no one style of European painting in India just as there is arguably no single style of Company painting. The colonial images range from orientalist oils in which exotic figures are dwarfed by massive architectural backdrops to sketches hastily executed by amateurs at an evening’s get-together. Some illustrations are carefully rendered with an eye for accuracy, but others include fair-haired dancers in European shoes and instruments that look anything but Indian. The British, however, seemed to have a fascination for the ‘nautch’ as they called the Indian dance performances they viewed, and provided posterity with a varied yet extensive record (Figures 5.2, 5.4, and 5.5). Furthermore, the colonial images often accompany written accounts, which in turn offer detailed ‘outsider’ testimony.

Figure 5.7 A group of dancing-girls and musicians performing beneath a canopy, ca. 1830. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Their dances require great attention, from the dancer’s feet being hung with small bells, which act in concert with the music. Two girls usually perform at the same time; their steps are not so mazy or active as ours, but much more interesting; as the song, the music and the motions of the dance, combine to express love, hope, jealousy, despair, and the passions so well known to lovers, and very easily to be understood by those who are ignorant of other languages. The Indians are extremely fond of this entertainment and lavish large sums on their favourites (Forbes, Oriental Memoires, 1813; quoted in Dyson 1978: 337).

The voluminous quantity of letters, diaries and published accounts written by European travellers in India forms a literary genre in its own right (Dyson 1978: 2) and these travel writings contain a surprising number of descriptions of dance or ‘nautch’. Because they are personal documents, however, the information within them is always presented in words that preserve the individual reactions and prejudices of the writer. Some, like James Forbes above, were positive, but other writers were much less taken with the performances:

… he brought forward an odious specimen of Hindoostanee beauty, a dancing-woman, for my special gratification, but such a wretch … The musicians then commenced a native air, merely a repetition of four notes; she advanced, retreated, swam round, the while making frightful contortions with her arms and hands, head and eyes. This was her ‘Poetry of motion’; I couldn’t even laugh at it (The Journal of Mrs. Fenton, 1826–1830, 1901, p. 243; quoted in Dyson 1978: 340–41).

Probably in part because they are often interpreted simply as a record of Western prejudice and misunderstanding, but also certainly because they offer no support to the dominant narrative of male, devotional dance, these sources have by and large not been included in histories of kathak. They are, nevertheless, a rich resource and important part of the historical record documenting music and dance during this period (Bor 1986/7 and Brown 2000).

The ‘dancing-women’ in the colonial literature are certainly never called ‘Kathaks’, nor is their dance ever referred to by that name. Yet, one of kathak dance’s most contentious issues has long been the question of its connection to the so-called ‘nautch’. The term ‘nautch’ is an Anglicization of the Hindi word nāc which means dance, but its application by the Europeans to all types of Indian dance performed by professional women resulted in a stigma that still clings to North Indian dance today. ‘Nautch girls’ and the ‘nautch dance’ they performed were associated with prostitution and loose behaviour, although one searches in vain for such descriptions in the letters and diaries. The observers occasionally seemed relieved or even disappointed that what they saw could not be called immoral and the most suggestive part of the dance described in these letters and journals seems to be the dancers’ use of seductive glances. The role of women in North Indian music and dance and the female presence in kathak will be explored at more length in Chapter 7. What emerges of immediate interest from these colonial documents is the striking pervasiveness of female dancers and the realms of details concerning the dance itself.

The first European sources are the letters and reports of explorers and traders which date from as early as the seventeenth century. In these reports, the opulence and luxury of the Mughal courts and the activities of the exotic  aram vie for space with more mundane information concerned with the maintenance of European habits and various military and mercantile issues. Observations of Indian life include description and commentary of music and dance events, and these, like the citations above, are a mixture of appreciative and critical, objective and personal (for more information see Gupta 1916, Spear 1963 [1932], Brown 2000 and Bor 1998). By the late eighteenth century the personal letters, diaries and travelogues, in which the new Anglo-Indian aristocracy recorded its personal reactions to the new and exotic surroundings, appeared. A fascination with the ‘picturesque’ combined with occasional genuine attempts to understand Indian culture produced a surprising number of detailed depictions of dance performances. The colonists were largely unable to discriminate between competent and incompetent presentations or the social status of the women dancing. Yet because of their unfamiliarity with the art form and interest in its seemingly exotic differences, they recorded many details that the Indian writers may have thought obvious.

aram vie for space with more mundane information concerned with the maintenance of European habits and various military and mercantile issues. Observations of Indian life include description and commentary of music and dance events, and these, like the citations above, are a mixture of appreciative and critical, objective and personal (for more information see Gupta 1916, Spear 1963 [1932], Brown 2000 and Bor 1998). By the late eighteenth century the personal letters, diaries and travelogues, in which the new Anglo-Indian aristocracy recorded its personal reactions to the new and exotic surroundings, appeared. A fascination with the ‘picturesque’ combined with occasional genuine attempts to understand Indian culture produced a surprising number of detailed depictions of dance performances. The colonists were largely unable to discriminate between competent and incompetent presentations or the social status of the women dancing. Yet because of their unfamiliarity with the art form and interest in its seemingly exotic differences, they recorded many details that the Indian writers may have thought obvious.

The British observers during this period found that a dance performance was a regular and expected part of a dinner or party given by an Indian host. The dancers were sometimes the object of attention, but at other occasions danced and sang in the background, partially obscured by fans or other guests (Dyson 1978: 338 and Laird 1971: 299). Although some European writers described ‘a set of dancing-girls’ (Laird 1971: 241), most were more specific. ‘Two girls usually perform at the same time’, wrote James Forbes in his Oriental Memoires (1813; quoted in Dyson 1978: 337), and Miss Emma Roberts confirmed that the performance entourage ‘usually consists of seven persons [of whom] two only … are dancers, who advance in front of the audience, and are closely followed by three musicians, who take up their posts behind’ (Roberts, Scenes and Characteristics of Hindostan, 1835, I, 248; quoted in Dyson 1978: 346). A number of other accounts identify a single dancer as the ‘prima donna’ (Dyson 1978: 347) dancing a ‘pas seul’ (Dyson 1978: 353). The dancers sang as well and were accompanied by a small ensemble of male musicians who stood behind them and moved around the room as they danced. The accompanying instruments are described in various imaginative ways, but accounts agree on ‘a band of two or three musicians, generally consisting of a kind of violin [sāra gī], a species of mongrel guitar [sitār] and a tom-tom, or small drum, played with the fingers [tablā]: sometimes a little pair of cymbals are added [manjīra]’ (Captain Mundy, Pen and Pencil Sketches, etc., 1832, I, 88–92; quoted in Dyson 1978: 344). The musicians, ‘a debauched looking set of fellows’ (Dyson 1978: 343), reacted to the dancers’ performances by making ‘the most ridiculous grimaces’ (Dyson 1978: 336) and ‘horrible faces of the most intense excitement’ (Dyson 1978: 350) yet ‘apparently in a state of enchantment’ (Dyson 1978: 347).

gī], a species of mongrel guitar [sitār] and a tom-tom, or small drum, played with the fingers [tablā]: sometimes a little pair of cymbals are added [manjīra]’ (Captain Mundy, Pen and Pencil Sketches, etc., 1832, I, 88–92; quoted in Dyson 1978: 344). The musicians, ‘a debauched looking set of fellows’ (Dyson 1978: 343), reacted to the dancers’ performances by making ‘the most ridiculous grimaces’ (Dyson 1978: 336) and ‘horrible faces of the most intense excitement’ (Dyson 1978: 350) yet ‘apparently in a state of enchantment’ (Dyson 1978: 347).

The colonial observers were also in great accord regarding the dancers’ dress. Dancing girls are depicted as magnificently attired in luxurious fabrics with rich embroidery and vast quantities of jewellery. As well as toe-rings, nose-rings, necklaces, bracelets, finger-rings and jewels in their hair and on their foreheads, they wore anklets of small bells. Their clothing is described most frequently as ‘drapery’; they wore ‘enormous quantities of … cloth petticoats’, ‘cumbersome trousers’, ‘voluminous folds’ and ‘multifarious skirts’ (Dyson 1978: 338–56). It is difficult to turn some of these passages into useful descriptions because the writers used Western terminology, like ‘petticoat’, or misused Indian terms: one dancer is depicted as having a ‘sort of sarree’ over her head. Other writers, thankfully, provided clearer accounts, and one is left with a picture of dancing girls dressed in silk pyjamas (usually very loose at the ankle), full skirts consisting of many yards of often semi-transparent fabric and trimmed with a wide and ornate border, small vests, bodices or jackets open at the chest, and large veils worn over the head and across the chest (see in particular Captain Skinner, Excursions in India, etc., 1832, I, 70–74; quoted in Dyson 1978: 342–3 and Miss Roberts, Scenes and Characteristics of Hindostan, 1835, I, 248–53: quoted in Dyson 1978: 346–8).

The dances themselves were considered equally curious and, to many British spectators, simply boring. ‘As dull and insipid to European taste as could be well conceived’, wrote Bishop Heber (Laird 1971: 299) and Honoria Lawrence found the dance ‘monotonous’ (Lawrence and Woodiwiss 1980: 233). Not all the Europeans were so narrow-minded: Emily Eden admitted that she liked ‘to look at the nautching, which bores most people’ (Eden 1983: 536), and Miss Roberts actually seemed to be aware that the problem was with the audience, saying: ‘the performances are precisely the same, European eyes and ears being unable to distinguish any superiority in the quality of the voice or the grace of the movements’ (quoted in Dyson 1978: 347). Many of the writers began their tiny essays by maintaining that what they were watching was not really dance at all. Yet because the whole context – decor, sound and movement – was so foreign, so exotic and so ‘picturesque’, the performance descriptions are filled with evocative if not always complimentary details.

It is difficult to give you any proper idea of this entertainment; which is so very delightful, not only to black men, but to many Europeans.

A very large room is lighted up; at one end sit the great people who are to be entertained; at the other are the dancers and their attendants; one of the girls who are to dance comes forward, for there is seldom more than one of them dance at a time; the performance consists chiefly in a continual removing [of] the shawl, first over the head, then off again; extending first one hand then the other; the feet are likewise moved, though a yard of ground would be sufficient for the whole performance. But it is their languishing glances, wanton smiles, and attitudes that are not quite consistent with decency, which are so much admired; and whoever excels most in these is the finest dancer (Mrs Kindersley, Letters from the Island of Teneriffe, Brazil, the Cape of Good Hope and the East Indies, 1777, 231–2; quoted in Dyson 1978: 336).

Other letters give similar descriptions:

… their only movement is the shuffling forward three or four paces, then retiring in the same way, sometimes extending a stiff arm with the fingers spread, sometimes bending the arm on the head; their highest elegance in winning airs appears to be the slipping off and putting up again the part of the mantel or veil which is thrown over the head (The Private Journal of the Marquess of Hastings, 1858, I, 145–6; quoted in Dyson 1978: 338).

The dancing is even more strange, and less interesting than the music; the performers rarely raise their feet from the ground, but shuffle, or to use a more poetical, though not so expressive a phrase, glide along the floor, raising their arms, and veiling or unveiling as they advance or describe a circle (Miss Roberts, 1835; quoted in Dyson 1978: 348).

At length they began, not to dance, but to move gracefully, and slowly, throwing their arms about and waving their drapery, which they twisted round them, or let fall in becoming folds …

They afterwards acted, or rather moved a sort of play, representing a courtship … (Mrs Elwood, Narrative of a Journey, etc., 1830, II, 81–2; quoted in Dyson 1978: 341).

At the close of each stanza of the song, the girl floats forward toward the audience, by a sort of ‘sidling, bridling’, and, I may add, ‘ogling’ approach, moving her arms gently around her head, the drapery of which they are constantly arranging and displacing (Captain Mundy, 1832; quoted in Dyson 1978: 344).

From behind this screen [of their veils] they performed all the ‘coquetterie’ of their dances, which indeed is all the dance seems designed for; covering the face with it one moment, the head turned with a languishing air on one side, then drawing it away with an arch smile, and darting the glances of their dark eyes full upon you. After coming forward a little distance, their arms moving gracefully in concord with their feet in a species of ‘glissade’, for all their steps are sliding, they sink suddenly and make the prettiest pirouêtte imaginable; their loose petticoat thrown by a quick turn out of its folds, and born down by the weight of its border, encircles them like a hoop; they gently round their arms, affect to conceal their faces behind their screens of gauze, and then rising, bridle up their necks, as conscious that they had completely overcome you (Captain Skinner, 1832; quoted in Dyson 1978: 342–3).

There is certainly much here that can be connected with today’s kathak dance, the fragments in the earlier treatises and my observations from the iconography. Certainly Captain Skinner’s description of a dancer turning, encircled by her heavy bordered skirt seems a perfect match for the cakkars that are such an integral element of kathak today and also provides a link back to the bhramarīs found in the late Sanskrit treatises. Mrs Elwood’s ‘sort of a play representing courtship’ seems to show the dancers performing abhinaya of some sort; she did not mention whether a song accompanied this pantomime, but one should perhaps assume that it did. Furthermore, the picture of dancers moving with their hands and feet gracefully coordinated and their steps punctuated with the sound of ankle bells reminds one of the gentle yet rhythmic section called  hā

hā h that is rendered near the beginning of a kathak solo and also parts of the dance item gat nikās. The descriptions of dancers shuffling forward and back, extending their arms, and alternately covering and uncovering their heads and faces with their veils evoke gat nikās even more strikingly, and one can also once again contemplate a link between these dances, the jakka

h that is rendered near the beginning of a kathak solo and also parts of the dance item gat nikās. The descriptions of dancers shuffling forward and back, extending their arms, and alternately covering and uncovering their heads and faces with their veils evoke gat nikās even more strikingly, and one can also once again contemplate a link between these dances, the jakka ī dance of the Persian women in Nartananir

ī dance of the Persian women in Nartananir āya and the ‘stylized walking’ of the courtesans in Muraqqa‘-yi Dehlī.

āya and the ‘stylized walking’ of the courtesans in Muraqqa‘-yi Dehlī.

Today however, although the gliding steps of the cāl are still danced, kathak dancers do not wear veils in the same manner as the women of the past. In dance class, female dancers in India most often wear their dupa

ās placed over one shoulder with one end draped modestly over the front of the body and the other twisted around the waist. In performance, dupa

ās placed over one shoulder with one end draped modestly over the front of the body and the other twisted around the waist. In performance, dupa

ās are worn over one shoulder and across the body on an angle like a sash, or pinned securely on the shoulders and perhaps the head so as not to interfere with the dazzling spins and footwork that are such an important part of any performance. All the movements involving fabric described in the English letters cited above, flowing skirts, full sleeves and especially veils, are now shown by mimetic gestures and also performed by both men and women.

ās are worn over one shoulder and across the body on an angle like a sash, or pinned securely on the shoulders and perhaps the head so as not to interfere with the dazzling spins and footwork that are such an important part of any performance. All the movements involving fabric described in the English letters cited above, flowing skirts, full sleeves and especially veils, are now shown by mimetic gestures and also performed by both men and women.

This brings us to the question of male dancers, rare in both travel writings and iconography. One finds the description below in Burton:

Conceive, if you can, the unholy spectacle of two reverend-looking greybeards, … dancing opposite each other dressed in women’s attire; the flimsiest too, with light veils on their heads, and little bells jingling from their ankles, ogling, smirking, and displaying the juvenile playfulness of ‘– limmer lads and lassies –’ (Burton, Scinde, 1851, II, 247; quoted in Dyson, 1978: 355).

Although displaying a lack of understanding, not to mention unconcealed scorn, about indigenous theatrical traditions, Burton’s observation of male dancers dressed and dancing like women is worth noting. Cross-dressing is common in many North Indian performance genres including the folk theatre Nautankī (see Hansen 1992), in which men dress as women, and the devotional drama Rās Līlā (see Awasthi 1963, Thielmann 1998, Mason 2002), in which pre-pubescent boys dress as the milkmaids (gopīs) who dance with Krishna. There are clear choreographic connections between kathak and the dances of Rās Līlā, and occasional claims of a shared descent (Banerji 1982: 63) so it is perhaps not surprising to find in Thomas Duer Broughton’s travelogue The Costume, Character, Manners, Domestic Habits and Religious Ceremonies of the Mahrattas, dancing boys called ‘Kuthiks’ who dress like dancing girls and perform similar dances at holidays like Holi (Broughton 1813: 94). Four images in my initial study of iconography showed dancing boys, and I have seen further examples since then. In Platts’ dictionary, moreover, one of the definitions of a ‘kathak’ is a dancing boy. Finally, Louis Rousselet, in his description of travels in Central India, observed adult male dancers he called ‘Catthaks’ performing dressed as women in the court of Bhopal (Rousselet 1877: 548–51). The general dearth of male dancers could be explained through suggesting that the colonial observers were not interested in or present at performances by men, but the presence of male dancers or dancing boys called or calling themselves Kathaks dressing and dancing like women suggests a connection both to vernacular theatre like Rās Līlā or Nautankī and to male courtesans like the ones in Muraqqa‘-yi Dehlī.

Other male performers included in the letters and diaries are musicians and most often the accompanists of the dancers. Some writers described these men as minstrels or jongleurs, but others were able to identify the groups they saw as Mirasis (Wilson 1911: 233–44) or Bhats (Laird 1971: 268–70) and to provide a considerable amount of information about their activities. One might assume that if the British writers had generally seen other male dancers (Kathak or otherwise), they would have written about them too. The obvious response in defence of the dominant narrative is that of course they did not see them: why would Brahman dance-preachers who recounted sacred epics be performing at dinner parties for curious memsahibs? Yet the literature does not support this, but rather connects the Kathaks to the nautch dancers by maintaining that the Kathaks were the women’s teachers (Devi 1972: 166 and Narayan 1998: 22), claiming that the women borrowed elements from the dance of the Kathaks (Chatterji 1951: 131–2 and Baijnath 1963: 19) or describing the nautch as a debased or degenerate form of kathak (Singha and Massey 1967: 131 and Khokar 1984: 134). This brings us to one of the central paradoxes in kathak’s history: there are undeniable connections between the dances of the nautch girls and present-day kathak, yet in the colonial travelogues and the iconography the Kathaks themselves are barely in evidence. The explanations insisting that the female dancers learnt, adopted or changed a pre-existing ‘kathak’ dance are further compromised not only by the lack of credible evidence demonstrating what this dance was, where it was danced and by whom, but also because the few fleeting glimpses we have from the European travel-writings of men called Kathaks, they are dressed as and dancing like the women who supposedly stole their material. If, by the 1800s, the Kathaks had migrated to the courts and were teaching the dancing girls, they are not generally in the colonial evidence unless they were the dancers’ accompanists. This is quite possible, but once again undermines the claim that Kathaks were Brahman narrators of sacred epics and equates them instead to other communities of hereditary tablā and sāra gī players.

gī players.

The answers to this paradox are not in the colonial travel writings or the iconography, although both certainly contain valuable information about nineteenth-century dance practice in North India and clear choreographic connections to today’s kathak dance. The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, however, did see widespread migration of musicians and dancers in response to changing patronage and social instability caused in large part by the invading British. One legendary destination was the court of Lucknow in the province of Awadh in North-Central India. Artists flocked to Lucknow for what is still remembered as a dazzling centre of music and dance. The annexation of Awadh by the British in 1856, deportation of Wajid ‘Ali Shah to Matiaburj near Kolkata, and subsequent dismantling of the Nawab’s court signalled the beginning of the end of court patronage for music and dance in North India. Although many performers found further employment in some of the smaller remaining establishments including the homes of the aristocratic landowners, or zamīndārs, there was a general lament for the loss of Lucknow as a centre of culture and art. This in part manifested itself in a sudden need to document the music and dance of the era, and there are five extant treatises about music and dance dating from the last years of Wajid ‘Ali Shah’s rule and the decades following his exile and published as lithographed books. In them one finds both dance material that corresponds to today’s kathak and professional dancers and musicians called Kathaks.

The five treatises date between 1852 and 1877 and contain detailed information on melody, rhythm, dance, musicians and dancers. The first and last of these were ostensibly written by Wajid ‘Ali Shah himself:  aut al-Mubārak, only five years before his removal and exile, and Banī, 20 years later at his pseudo-court in Matiaburj. The other three are Maūdan al-Mūsīqī, written in 1856 by Muhammad Karam Imam, Ghunca-yi Rāg, written in 1862–3 by Muhammad Mardan ‘Ali Khan, and Sarmāya-yi Iśrat, written in 1875 by Sadiq ‘Ali Khan. Of these Maūdan al-Mūsīqī is probably the best known as the two initial chapters were translated into English from the original Urdu by Govind Vidyarthi and published in the Sangeet Natak Akademi Bulletin in 1959 under the titles ‘Melody through the Centuries’ (Vidyarthi 1959a) and ‘Effect of Ragas and Mannerism in Singing’ (Vidyarthi 1959b). The attention given to dance and dancers varies between volumes, but all describe what seem to be contemporary practice and performers. Adding the data found in these indigenous writings to the descriptions in the travel literature and observations from the iconography provides a rich understanding of nineteenth-century dance practice.

aut al-Mubārak, only five years before his removal and exile, and Banī, 20 years later at his pseudo-court in Matiaburj. The other three are Maūdan al-Mūsīqī, written in 1856 by Muhammad Karam Imam, Ghunca-yi Rāg, written in 1862–3 by Muhammad Mardan ‘Ali Khan, and Sarmāya-yi Iśrat, written in 1875 by Sadiq ‘Ali Khan. Of these Maūdan al-Mūsīqī is probably the best known as the two initial chapters were translated into English from the original Urdu by Govind Vidyarthi and published in the Sangeet Natak Akademi Bulletin in 1959 under the titles ‘Melody through the Centuries’ (Vidyarthi 1959a) and ‘Effect of Ragas and Mannerism in Singing’ (Vidyarthi 1959b). The attention given to dance and dancers varies between volumes, but all describe what seem to be contemporary practice and performers. Adding the data found in these indigenous writings to the descriptions in the travel literature and observations from the iconography provides a rich understanding of nineteenth-century dance practice.

Worthy of particular note are the performers themselves. Here, among Dharis, Kalawants, Bhands and Naqqals, are finally performers called Kathaks, and several are identifiable as the ancestors of present-day dancers. In the first chapter of Maūdan al-Mūsīqī, one finds the surname Kathak for nine performers: Prashaddu Kathak of Benares was a singer, Jatan Kathak of Benares was a sāra gī player, and the remaining seven, Ram Sahai Kathak of Handia, Beni Prasad and Prasaddoo Kathak of Benares, Lallooji and Prakash Kathak, and Prakash’s nephew Durga and son Mansingh, were all dancers and Ustads ‘proficient in … bhāv’ (Vidyarthi 1959a: 20 and 25). There are also female singers and dancers identified, among whom the women of Benares, ‘a centre where a style of singing, dancing and Bhāv-batana flourishes’, stand out (Vidyarthi 1959a: 25). A search of the dance chapter in Sarmāya-yi Iśrat is not as productive, but one still reads that ‘Prakash Kathak’s son is an accomplished master of nritt and is very famous’ (Sarmāya-yi Iśrat: 153). There are also several references to Kathaks as a group being expert performers of dances such as parmilū (Sarmāya-yi Iśrat: 158–160 and 172–3). Wajid ‘Ali Shah’s books

gī player, and the remaining seven, Ram Sahai Kathak of Handia, Beni Prasad and Prasaddoo Kathak of Benares, Lallooji and Prakash Kathak, and Prakash’s nephew Durga and son Mansingh, were all dancers and Ustads ‘proficient in … bhāv’ (Vidyarthi 1959a: 20 and 25). There are also female singers and dancers identified, among whom the women of Benares, ‘a centre where a style of singing, dancing and Bhāv-batana flourishes’, stand out (Vidyarthi 1959a: 25). A search of the dance chapter in Sarmāya-yi Iśrat is not as productive, but one still reads that ‘Prakash Kathak’s son is an accomplished master of nritt and is very famous’ (Sarmāya-yi Iśrat: 153). There are also several references to Kathaks as a group being expert performers of dances such as parmilū (Sarmāya-yi Iśrat: 158–160 and 172–3). Wajid ‘Ali Shah’s books  aut al-Mubārak and Banī, on the other hand, contain no mention of people called Kathaks at all, which is rather startling considering not only the context but also the claim that one of the Kathaks taught the Nawab how to dance (see Kothari 1989: 24). The longest chapter in Banī is about, not dance or kathak, but naqqāl (plays) performed by entertainers identified as Naqqals, Bhands and Bhagats. The final chapter includes a number of names of musicians and dancers, but they are all Muslim and do not include any of the names connected with the Lucknow gharānā (Shah 1987 [1877]: 176 and 184).

aut al-Mubārak and Banī, on the other hand, contain no mention of people called Kathaks at all, which is rather startling considering not only the context but also the claim that one of the Kathaks taught the Nawab how to dance (see Kothari 1989: 24). The longest chapter in Banī is about, not dance or kathak, but naqqāl (plays) performed by entertainers identified as Naqqals, Bhands and Bhagats. The final chapter includes a number of names of musicians and dancers, but they are all Muslim and do not include any of the names connected with the Lucknow gharānā (Shah 1987 [1877]: 176 and 184).

These sources also contain very thorough descriptions of current dance practice, much of which corresponds to kathak today. There is considerable material in all five sources that can be connected directly to kathak’s rhythmic items, including the dance bols ta, thei and tat and compositions like  uk

uk ā, tora, paran, gintī, and parmilū. Furthermore, all five books contain lists of dances called gat which are described in great detail and clarified further in Banī and Sarmāya-yi Iśrat by the inclusion of illustrations. Each gat is in essence a posture, although not a static one and the descriptions also contain instructions on moving the body, when to face the audience, and how to use the eyes expressively. There are 14 gats described in

ā, tora, paran, gintī, and parmilū. Furthermore, all five books contain lists of dances called gat which are described in great detail and clarified further in Banī and Sarmāya-yi Iśrat by the inclusion of illustrations. Each gat is in essence a posture, although not a static one and the descriptions also contain instructions on moving the body, when to face the audience, and how to use the eyes expressively. There are 14 gats described in  aut al-Mubārak, which are reproduced in both Maūdan al-Mūsīqī and Ghunca-yi Rāg. Their titles are largely evocative and feminine, and include the faryād or pleading gat, the parī or fairy gat and the ghū

aut al-Mubārak, which are reproduced in both Maūdan al-Mūsīqī and Ghunca-yi Rāg. Their titles are largely evocative and feminine, and include the faryād or pleading gat, the parī or fairy gat and the ghū gha

gha or veil gat. Maūdan al-Mūsīqī adds seven more gats to these 14. Six are in keeping with the feminine character of these originals, but the list begins with an addition, the Krishna gat, which ‘is practised among the Kathaks’ (Maūdan al-Mūsīqī: 5). Sarmāya-yi Iśrat, which lists 20 gats, and Banī, which contains 19, do not precisely reproduce the list from

or veil gat. Maūdan al-Mūsīqī adds seven more gats to these 14. Six are in keeping with the feminine character of these originals, but the list begins with an addition, the Krishna gat, which ‘is practised among the Kathaks’ (Maūdan al-Mūsīqī: 5). Sarmāya-yi Iśrat, which lists 20 gats, and Banī, which contains 19, do not precisely reproduce the list from  aut al-Mubārak, but it is clear that these dances are part of the same tradition and they also present inarguable correspondences to some of today’s kathak dance items. For example, the Janaśīn ki gat (Heir’s Gat from Sarmāya-yi Iśrat: 165), which is taught to beginners, instructs the dancer to sway rhythmically with her right hand above her head and her left arm out to the side (Figure 5.8; see also Figures 1.1 and 5.3). In the Mardāni ki gat (the Male Gat, also from Sarmāya-yi Iśrat: 173), which is danced by Kathaks and Bhands, the dancer folds his arms across his body and stamps his feet in the rhythm of the drum. Furthermore, the striking number of gats that describe gestures with skirts and veils provides a clear link to the descriptions of dance in the travel writings and the iconography and some gat nikās still danced today (Figure 5.9).

aut al-Mubārak, but it is clear that these dances are part of the same tradition and they also present inarguable correspondences to some of today’s kathak dance items. For example, the Janaśīn ki gat (Heir’s Gat from Sarmāya-yi Iśrat: 165), which is taught to beginners, instructs the dancer to sway rhythmically with her right hand above her head and her left arm out to the side (Figure 5.8; see also Figures 1.1 and 5.3). In the Mardāni ki gat (the Male Gat, also from Sarmāya-yi Iśrat: 173), which is danced by Kathaks and Bhands, the dancer folds his arms across his body and stamps his feet in the rhythm of the drum. Furthermore, the striking number of gats that describe gestures with skirts and veils provides a clear link to the descriptions of dance in the travel writings and the iconography and some gat nikās still danced today (Figure 5.9).

Figure 5.8 Janaśīn ki gat from Sarmāya-yi Iśrat, 1875: 165. © The British Library Board. Shelfmark MS 14119.f.27

To the nineteenth-century lithographs another source should be added. Possibly the best-known account of the cultural life of Lucknow under Wajid ‘Ali Shah is a series of articles written by Abdul Halim Sharar between 1913 and 1920. Collected together and published as Gu ashta-yi Lakhnau, the complete book was translated into English under the title Lucknow: The Last Phase of an Oriental Culture (Sharar 1975). Five chapters in Sharar deal with music, dance, and theatre. Chapter 23 in the English translation is entitled ‘Dance and the Development of the Kathak School’ but it is important to realize that the chapter headings are not original to Sharar so the use of the term ‘kathak’ in the sense of a ‘school’ or style of dance is anachronistic (Sharar 1975: 25). One must also remember that although he was describing the same court and city culture as the other nineteenth-century documents, Sharar was in actual fact writing some 50 years later. He did not include any of the detailed choreographic information found in the treatises, but emphasized the role played by the Kathaks and included more information about them than any documentation thus far. According to Sharar, the Kathaks came to Lucknow from Ayodhya and Benares, and he differentiated between the Hindu Kathaks and the Muslim Bhands, who are associated in Sarmāya-yi Iśrat, identifying the Kathaks as the ‘real dancers’. Sharar did not use ‘Kathak’ as a surname: one can only assume from his introductory sentence – ‘there have always been accomplished Hindu Kathaks in Lucknow’ (which seems to contradict his earlier claim that they came from Ayodhya) – that the 10 dancers subsequently listed are all Kathaks. Several of the names of the ancestors of the present-day Lucknow gharānā appear here, as in Maūdan al-Mūsīqī and Sarmāya-yi Iśrat: Parkashji, Dayaluji, Durga Prasad, Thakur Prasad and the sons of Durga Prasad, Kalka and Bindadin (Sharar 1975: 124).

ashta-yi Lakhnau, the complete book was translated into English under the title Lucknow: The Last Phase of an Oriental Culture (Sharar 1975). Five chapters in Sharar deal with music, dance, and theatre. Chapter 23 in the English translation is entitled ‘Dance and the Development of the Kathak School’ but it is important to realize that the chapter headings are not original to Sharar so the use of the term ‘kathak’ in the sense of a ‘school’ or style of dance is anachronistic (Sharar 1975: 25). One must also remember that although he was describing the same court and city culture as the other nineteenth-century documents, Sharar was in actual fact writing some 50 years later. He did not include any of the detailed choreographic information found in the treatises, but emphasized the role played by the Kathaks and included more information about them than any documentation thus far. According to Sharar, the Kathaks came to Lucknow from Ayodhya and Benares, and he differentiated between the Hindu Kathaks and the Muslim Bhands, who are associated in Sarmāya-yi Iśrat, identifying the Kathaks as the ‘real dancers’. Sharar did not use ‘Kathak’ as a surname: one can only assume from his introductory sentence – ‘there have always been accomplished Hindu Kathaks in Lucknow’ (which seems to contradict his earlier claim that they came from Ayodhya) – that the 10 dancers subsequently listed are all Kathaks. Several of the names of the ancestors of the present-day Lucknow gharānā appear here, as in Maūdan al-Mūsīqī and Sarmāya-yi Iśrat: Parkashji, Dayaluji, Durga Prasad, Thakur Prasad and the sons of Durga Prasad, Kalka and Bindadin (Sharar 1975: 124).

Figure 5.9 Ghū gha

gha ki gat from Sarmāya-yi Iśrat, 1875: 171. © The British Library Board. Shelfmark MS 14119.f.27

ki gat from Sarmāya-yi Iśrat, 1875: 171. © The British Library Board. Shelfmark MS 14119.f.27

All the information dating after the thirteenth century examined thus far describes dance solely in the context of Muslim court culture and culminates with the sudden flood of documentation from the court of Wajid ‘Ali Shah. In many ways, this is no surprise. When one sets the claims of Vedic origins aside, the predominant oral history of kathak places its genesis in the Mughal courts and its maturation in the court of Lucknow, where Prakash or his forebears migrated only a few generations earlier (Banerji 1982, Narayan 1998). There is, however, a less detailed but parallel history which places kathak in Rajasthan, either as a separate but equal tradition (Kothari 1989) or as the place of origin for Kathaks who then migrated to Varanasi and Lucknow (Khokar 1963 and Devi 1972 among others). Unfortunately, history has not provided us with the same level of documentation regarding Kathaks and their performances in Rajasthan or Rajputana, as the British called it. There seem only to be the records of the Gu ījankhānā, the musical establishment in the Jaipur court, which include performers called Kathak-Bhands in the lists between 1883 and 1933 (Erdman 1985: 81–2, also see Chandramani 1979) but do not provide any details of their performance practice.

ījankhānā, the musical establishment in the Jaipur court, which include performers called Kathak-Bhands in the lists between 1883 and 1933 (Erdman 1985: 81–2, also see Chandramani 1979) but do not provide any details of their performance practice.

The lack of detailed documentation from Rajasthan is undoubtedly because, rather being seized and occupied like Awadh, Rajputana became a tributary state under the Raj and thus retained a certain degree of political independence including a largely uninterrupted palace culture. The outpouring of documentation after the annexation of Awadh expressed a sense of cultural loss and nostalgia that extended into the early-twentieth-century works of Sharar, and provided fertile ground for subsequent cultural mythologies. Lucknow’s misfortune was history’s gain, however. It is during these 200 or so years of migration and political change following the death of Aurangzeb in 1707 that most of the now characteristic instruments and genres of North Indian music appeared, and the richly descriptive material from Awadh documents this to some extent. Sitār, sarod, sāra gī, tablā, and the vocal genres of khyāl and

gī, tablā, and the vocal genres of khyāl and  humrī all began to take the forms we recognize today through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (see Bor 1986/7, du Perron 2007, Kippen 1988 and 2006, Manuel 1989, Miner 1993, Rao 1990 and 1996, Qureshi 1997 among others). It makes sense that the dance we now know as kathak did also, although the items that emerge in the documentation are still not yet part of a single performance form nor necessarily danced by Kathaks.

humrī all began to take the forms we recognize today through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (see Bor 1986/7, du Perron 2007, Kippen 1988 and 2006, Manuel 1989, Miner 1993, Rao 1990 and 1996, Qureshi 1997 among others). It makes sense that the dance we now know as kathak did also, although the items that emerge in the documentation are still not yet part of a single performance form nor necessarily danced by Kathaks.

Kathak dance, as we know it today, closely resembles some of the dances and other performance genres from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Although none of these genres are actually called kathak, many of the assorted choreographic trails lead clearly to today’s dance. The trajectory of the Kathaks, on the other hand, is less clear. Once one accepts the premise that the connections to the ancient Kathakas are manufactured and cannot be verified by historical evidence, one is struck by the Kathaks’ seemingly sudden appearance in the travel writings and treatises. They also appear in the British census reports and attendant ‘Tribes and Castes’ volumes around the same time. One then finds a hundred years of consistent documentation of a ‘caste’ of hereditary performers called Kathaks who are most often identified as the teachers and accompanists of dancing girls. The descriptions of the Kathaks, their activities and their status vary somewhat through the years, and will be analysed in detail in Chapter 6. The contextual and choreographic evidence, on the other hand is considerable and worth summarizing at this point.

Although the brief glimpses of Kathaks in the British travel writings show men or boys dressed and dancing as women, much of the material from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries indicates a gender division between male and female dancers and dances. Women dominate the colonial material and iconography, and multiple examples in the Rajput, Company and British artwork of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries combined with the descriptions from the British letters give a reliable picture of performances presented by professional female singer-dancers with a consistent choreographic vocabulary and accompanying ensemble. In the paintings examined in this study, most of the scenes are set in a court or salon and contain one, two or three female dancers with a small group of male accompanying musicians. Although the instruments do not always precisely resemble their late-twentieth-century counterparts, they are nonetheless easy to identify. The most common ensemble comprises two men playing sāra gī and one playing tablā, the barrel-shaped dholak or a pakhāvaj. Often, in addition to the few who are obviously dancing, there is a small entourage of women who are seemingly clapping and singing or merely seated nearby. Indeed in many of the images with three dancers, one woman is in front of her ‘sisters’ and portrayed in a more active pose. This not only matches the descriptions from the letters, but the uniformity of this ensemble through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in all four styles of painting suggests that the various shifts of patronage did not result in any noticeable change in performers.

gī and one playing tablā, the barrel-shaped dholak or a pakhāvaj. Often, in addition to the few who are obviously dancing, there is a small entourage of women who are seemingly clapping and singing or merely seated nearby. Indeed in many of the images with three dancers, one woman is in front of her ‘sisters’ and portrayed in a more active pose. This not only matches the descriptions from the letters, but the uniformity of this ensemble through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in all four styles of painting suggests that the various shifts of patronage did not result in any noticeable change in performers.

The colonial travel writings most frequently describe a dance characterized by gliding or shuffling steps, slow turns and expressive gestures involving the dancers’ full skirts, sleeves and veils. About 80 percent of the paintings show dancers in poses with one arm extended or raised, gesturing with their veils or skirts or both. Some of these clearly show dancers covering their faces with veils made of see-through gauze, and in many pictures the dancers seem to be walking. The connections between past and present dances are undeniable; all the evidence here points to a continuity, of movement vocabulary if not choreography, linking the Persian jakka ī in the court of Akbar, the ‘stylized walking’ of Delhi courtesans in the mid-1700s, the shuffling steps and waving drapery of the nautch girls, and the ghū

ī in the court of Akbar, the ‘stylized walking’ of Delhi courtesans in the mid-1700s, the shuffling steps and waving drapery of the nautch girls, and the ghū gha

gha or veil dances in the five treatises and the gat nikās repertoire in kathak today. In addition, images of four women identified as dancers are not dancing, but sitting, singing and gesturing, an activity also described in the writings of colonial scholars Willard (in Tagore 1882: 36) and Pingle (1989 [1898]: 285–7) and matching the performance style of the now rarely-presented ‘seated abhinaya’.

or veil dances in the five treatises and the gat nikās repertoire in kathak today. In addition, images of four women identified as dancers are not dancing, but sitting, singing and gesturing, an activity also described in the writings of colonial scholars Willard (in Tagore 1882: 36) and Pingle (1989 [1898]: 285–7) and matching the performance style of the now rarely-presented ‘seated abhinaya’.

The British descriptions also include detailed descriptions of the dancers’ dress. The ‘nautch girls’ wear wide-legged pyjamas, layers of fabric, full skirts, tight vests and ‘screens of gauze’. The paintings support this and it is common in all four styles of paintings to see dancers with transparent veils or shawls. It is the photographic record, however, that offers the strongest support: photographs of courtesans from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries show women dressed in layered luxurious outfits, very full skirts with wide embroidered borders, glittering jewellery and elegant dupa

ās (see Nevile 1996: 110–11 and Kothari 1989: 31 and 48–9). On the contemporary concert stage, clothes like these would make much of the repertoire impossible to execute. The ‘Mughal’ costume, however, has preserved the full skirt with the embroidered border and the small vest described in the travel writings, and its most traditional jewellery includes the jhūmar ornament worn on the side of the head. Both ‘Mughal’ and ‘Hindu’ costumes feature the gauzy veils and copious jewellery appearing in the photographs and made much of in the travel writings.

ās (see Nevile 1996: 110–11 and Kothari 1989: 31 and 48–9). On the contemporary concert stage, clothes like these would make much of the repertoire impossible to execute. The ‘Mughal’ costume, however, has preserved the full skirt with the embroidered border and the small vest described in the travel writings, and its most traditional jewellery includes the jhūmar ornament worn on the side of the head. Both ‘Mughal’ and ‘Hindu’ costumes feature the gauzy veils and copious jewellery appearing in the photographs and made much of in the travel writings.

But what of the other characteristic elements of kathak, the virtuosic footwork, rhythmic compositions and dazzling spins? One could claim that the postures in many of the Indian paintings might represent dancers who had just finished a series of spins, and there are certainly descriptions in the travel writings of dancers executing ‘pirouettes’. Footwork, however, is clearly difficult both to depict and to discern in a visual medium. An alternate answer, however, is that the professional women performers of this time probably did not dance fast, virtuosic repertoire. In a very practical sense the clothing they wore would have made the swift spins and drut lay compositions like the  uk

uk ās and parans performed today impossible. Fast footwork would probably have been ineffective, not only due to the loose pyjamas that covered the feet of some dancers, but also because the iconography in all styles shows many of the women performing on carpets.

ās and parans performed today impossible. Fast footwork would probably have been ineffective, not only due to the loose pyjamas that covered the feet of some dancers, but also because the iconography in all styles shows many of the women performing on carpets.

But if the women did not dance these items, should they be connected to male dancers, like the Kathaks? In the literature the Kathaks appear in British census reports as the accompanists and teachers of female performers, and their names can be found in the nineteenth-century treatises Maūdan al-Mūsīqī and Sarmāya-yi Iśrat. They do not seem to be in any of Wajid ‘Ali Shah’s books, but are clearly present in the early-twentieth-century articles by Sharar. In Sarmāya-yi Iśrat, the Mardāni gat, wherein the ‘bols are played out by the feet and the ghu grūs are set to the pakhāvaj’ is ‘the style and kind [belonging] to Bhands’ and dancing it is the ‘job of the Kathaks’ (Sarmāya-yi Iśrat: 173). The Krishna gat in Maūdan al-Mūsīqī, which is a virtuosic spin on the knees that is today part of the dance section of the devotional folk theatre Rās Līlā, is ‘practised among the Kathaks’ (Maūdan al-Mūsīqī: 5). Rhythmic items like tora, gintī and parmilū, and the dance bols ta, thei, and tat still in use today appear not only in the Urdu works, but also in B.H.A. Pingle’s book Indian Music (1898). Sharar also differentiates between male and female dance, contrasting the expression of ‘amorous dalliance’ in the performance of women to the ‘sprightliness and vigor’ [sic] in the movements of men. He further points out that ‘although there is a certain relationship in the arts of both groups, male and female, there is a palpable difference between them’ (Sharar 1975: 141–2). One of the first articles in the twentieth century about ‘the dance of the Kathaks’ supports this assertion as well, stating that ‘certain “torahs” are set apart for men and others are for women’ (Zutshi 1937).

grūs are set to the pakhāvaj’ is ‘the style and kind [belonging] to Bhands’ and dancing it is the ‘job of the Kathaks’ (Sarmāya-yi Iśrat: 173). The Krishna gat in Maūdan al-Mūsīqī, which is a virtuosic spin on the knees that is today part of the dance section of the devotional folk theatre Rās Līlā, is ‘practised among the Kathaks’ (Maūdan al-Mūsīqī: 5). Rhythmic items like tora, gintī and parmilū, and the dance bols ta, thei, and tat still in use today appear not only in the Urdu works, but also in B.H.A. Pingle’s book Indian Music (1898). Sharar also differentiates between male and female dance, contrasting the expression of ‘amorous dalliance’ in the performance of women to the ‘sprightliness and vigor’ [sic] in the movements of men. He further points out that ‘although there is a certain relationship in the arts of both groups, male and female, there is a palpable difference between them’ (Sharar 1975: 141–2). One of the first articles in the twentieth century about ‘the dance of the Kathaks’ supports this assertion as well, stating that ‘certain “torahs” are set apart for men and others are for women’ (Zutshi 1937).

The documentation up to the turn of the twentieth century nevertheless leaves us with several unsolved mysteries. The evidence from Chapter 4 clearly supports the assertion that the Kathakas in the early Sanskrit sources are storytellers with no connection to today’s dancers. But if this is so, then the Kathaks as a community of performers seem quite suddenly to appear in the historical record in the 1800s. Afterwards, there is copious supportive documentation that leads reasonably smoothly into the twentieth century. But the questions remain – why is there no mention of a group of hereditary performers called Kathaks in sources like Ā’īn-i Akbarī that include detailed lists of musicians and dancers? Why are there no Kathaks in Wajid ‘Ali Shah’s books? The other Urdu treatises identify the Kathaks as respected masters of their art and the British censuses describe them as music and dancing masters. Where, then, did they come from? The Kathak-Misra birādarī described in Chapter 3 comprises musicians, dancers and actors, which seems in keeping with the information in the censuses and with the activities of the Kathaks named in Maūdan al-Mūsīqī. When did part of the community become solely associated with a dance style? Finally, there are a great number of undeniable associations between ‘nautch’ dance and today’s kathak, yet also descriptions of separate repertoires for male and female dancers. How and why did the male dancers become the authoritative ‘owners’ of all these items and gestures in the twentieth century? The next step in finding some answers is to look once again at the community called ‘Kathak’.