Thanksgiving for God’s Work in Thessalonica

1 Thessalonians 1:1–10

Ever since Paul was torn away from the new Christians at Thessalonica he longed to return to them and encourage them in their newfound faith. Here in the letter’s opening we see him doing what he had wanted to do in person. He reassures them by reminding them of his ongoing prayers on their behalf. He also recounts the astonishing work of God among them that has enabled them to set out on a new way of life in service to God.

Letter Opening (1:1)

1Paul, Silvanus, and Timothy to the church of the Thessalonians in God the Father and the Lord Jesus Christ: grace to you and peace.

NT: Acts 15–17; 2 Thess 1:1–2

Catechism: the Church, 751–52; grace, 1996–2005

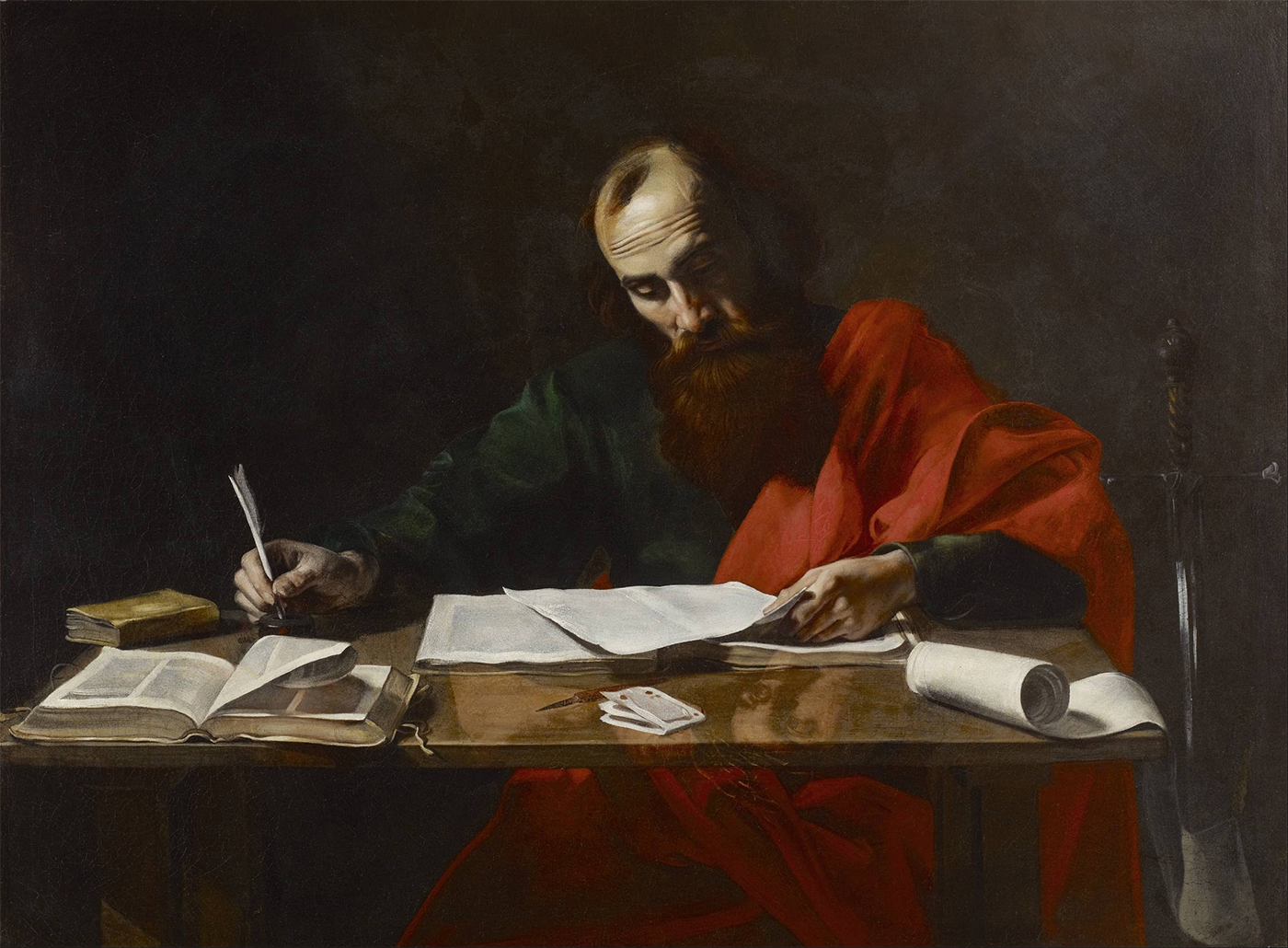

Artists have often imagined Paul alone at a desk, pen in hand, thoughtfully writing to his churches. Deservedly famous works such as Rembrandt’s St. Paul at His Writing Desk or Valentin de Boulogne’s Saint Paul Writing His Epistles continue to shape the way we imagine the apostle at work. Yet right from the beginning of 1 Thessalonians we notice a problem with the image of Paul as solitary genius, for this letter says that it is from Paul, Silvanus, and Timothy. Paul is working as part of a team here, as he does in five of his letters. The Latin name “Silvanus” almost certainly refers to the companion of Paul known as Silas in the book of Acts. According to Acts, Silas was one of the leaders of the Jerusalem church (Acts 15:22) who had accompanied Paul to Thessalonica (17:1–10). Timothy, the other coauthor mentioned in this letter, was one of Paul’s closest companions. In his letter to the Philippians Paul says that Timothy served alongside of him “as a child with a father” (Phil 2:22). Paul also refers to him as a “beloved and faithful son in the Lord” (1 Cor 4:17), “co-worker” (Rom 16:21), and “brother” (1 Thess 3:2). It is with these trusted companions that Paul writes to the Thessalonians. Also, Paul would not have been holding the pen. Instead, he would have dictated to a scribe.1

Figure 2. Saint Paul Writing His Epistles by Valentin de Boulogne (1591–1632). [Public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

Did Silvanus and Timothy help Paul compose the letter? Scholars are divided on this question. It is clear that Paul is the principal author. His name is listed first, and in 2:18 he refers to himself in the first-person singular (“We decided to go to you—I, Paul, not only once but more than once”). At the same time, the very fact that Paul singles himself out in 2:18 suggests that the rest of the letter is from Silvanus and Timothy as well. Moreover, Paul frequently mentions coworkers who are with him without mentioning them as authors in the opening address.2 He also dictated to scribes who were present but not listed as authors (Rom 16:22; 1 Cor 16:21; Gal 6:11). This shows that Paul did not list his companions as coauthors simply because they were nearby when he was writing. Though we will never know precisely what role Silvanus and Timothy played in composing the letter, we should presume that the Thessalonian Christians read it as if it were from all three men, but with Paul as the leading voice.

The letter is addressed to the church of the Thessalonians. In all of Paul’s other letters, with the exception of 2 Thessalonians, Paul describes the church in terms of its location. For instance, in 1 Cor 1:2 he writes “to the church of God that is in Corinth.” When writing to the Thessalonians, however, Paul describes the church in terms of the people who belong to it. His words could be paraphrased, “to the church that is made up of people who live in Thessalonica.”

Paul describes the church of the Thessalonians as being in God the Father and the Lord Jesus Christ. Only here and in 2 Thess 1:1 does he describe Christians as being “in God,” usually preferring to speak of being “in Christ” (Rom 6:11, 23; 8:1–2; 1 Cor 1:30; Gal 3:26). What does it mean for the church to be “in” God? The Greek could indicate that the Thessalonian church was brought into being by God the Father and the Lord Jesus. The Greek preposition en (“in”) could also indicate that the church has its location in God and in Jesus. Regardless of how the phrase is translated, it is clear that God the Father and the Lord Jesus are responsible for the existence of this new church. The words “in God the Father and the Lord Jesus Christ” also show that for Paul those who are “in Christ” are also “in God.”3 A few verses later Paul gives thanks for the empowering work of the Holy Spirit, which has enabled the Thessalonians to become imitators of the apostles and of Jesus by rejoicing in suffering (1 Thess 1:4–6). Even though Paul does not manifest in his letters the fully developed doctrine of the Trinity that will be formulated and defined in later centuries, it is striking to note that in the very first chapter of what is arguably his oldest surviving letter, he speaks of God the Father (1:1); the Son Jesus, who was raised from the dead and who will return (1:10); and the Spirit, who empowers the Thessalonians to rejoice in the midst of suffering (1:5–6).

The words grace to you and peace are a celebrated example of Paul’s ability to rethink everything in light of the gospel. As noted in the introduction, letters in Paul’s day usually began with this formula: “the Writer, to the Addressee, greetings [chairein].”4 Paul changes the word “greetings” (chairein) to the related noun “grace” (charis) and adds the traditional Jewish greeting “peace.” In so doing, Paul indicates from the very first line of the letter that this is no ordinary correspondence between friends. The love between Paul and these new converts springs from God’s generosity.

Reflection and Application (1:1)

While preaching on the first verse of 1 Thessalonians, St. John Chrysostom discusses the extraordinary honor of being the church (ekklēsia) that is “in” God. Chrysostom was a native Greek-speaker who understood that the word ekklēsia was common in Paul’s world: “For there were many assemblies [plural of ekklēsia].” To be an ekklēsia in God “is a great honor—nothing is equal to it!” Chrysostom also sees this description of the church in Thessalonica as a challenge to his own congregation, warning that those who live in sin reject God’s embrace: “May it be, then, that this church also be so called. . . . [But] if someone is a servant of sin, he cannot be called ‘in God.’”5

Thanksgiving (1:2–4)

2We give thanks to God always for all of you, remembering you in our prayers, unceasingly 3calling to mind your work of faith and labor of love and endurance in hope of our Lord Jesus Christ, before our God and Father, 4knowing, brothers loved by God, how you were chosen.

OT: Deut 7:7–8; Ps 34:2

NT: 1 Cor 13:13; 2 Thess 1:3; 2:13

Catechism: theological virtues, 1812–19

After the greeting, Paul’s Letters usually include a word of thanksgiving to God and a description of how he prays for the addressees. His letter to the Galatians omits the thanksgiving—it seems that Paul was in no mood to thank God for them. In contrast, here we see Paul overjoyed at the Spirit-empowered reception of the gospel by the Thessalonians. The thanksgiving section of this letter goes on through verse 10 and then starts again in 2:13, finally coming to a conclusion, arguably, at the end of chapter 3. As the letter progresses, we learn why Paul is so effusive in his thanksgiving to God. Though they are a very young community—perhaps only a few months old—they are already manifesting the joy of the Holy Spirit as they experience persecution (1:6).

How is it possible for Paul to give thanks to God always and to pray for the Thessalonians unceasingly? Though there is an element of hyperbole here, these words should not be dismissed as mere exaggeration. For Paul, prayer is not cordoned off into certain parts of the day or certain days of the week. One’s whole life is to be lifted up to God in prayer through the Spirit (Rom 8:26; 12:1). He asks the Thessalonians to “rejoice always,” “pray without ceasing,” and give thanks in all circumstances (1 Thess 5:16–18). This is not to say that Paul recommends spending every moment reciting a prayer—as if that were possible. Rather, for Paul, prayer and life are coextensive. Every moment is to be caught up in praise to God. As Col 3:17 puts it, “Whatever you do, in word or in deed, do everything in the name of the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God the Father through him.”

The opening thanksgivings in Paul’s Letters serve a double purpose. They encourage the recipients by informing them of Paul’s prayers on their behalf, but they also indicate the subjects that Paul is going to develop over the course of the letter. In this sense, the thanksgivings are almost like a little table of contents.6 For example, Paul begins 1 Corinthians by thanking God for the spiritual gifts that have been given to the Corinthians (1:4–7). This becomes a major topic in the letter (chaps. 12–14). Philippians begins with thanksgiving for the Philippians’ partnership in the gospel (1:3–5), a subject to which Paul returns repeatedly (2:25–30; 4:10–20). Here in 1 Thessalonians he thanks God for their work of faith and labor of love and endurance in hope. This is probably the first occurrence of the trio of faith, love, and hope in Christian literature, and it anticipates much of what Paul goes on to discuss.

What does Paul mean by “work of faith”? In a homily on this passage St. John Chrysostom offers a helpful explanation: “What is ‘the work of faith’? That nothing turns you away from your constancy. . . . If you believe, suffer all things” without falling away.7 The Thessalonians had responded to the gospel with faith, but since then they experienced hard times (1 Thess 1:6; 2:14; 3:3), and Paul was worried that their faith would be shaken (3:2–5). When Timothy returned from visiting them, Paul was overjoyed to learn that they continued to trust in God in their suffering (1:6; 3:6–10). Paul gives thanks to God that the Thessalonian Christians’ faith continues to manifest itself in works, and he prays for the opportunity to visit them again and strengthen their trust in God even more (3:9–10).

The phrase “labor of love” in contemporary English refers to work done because of the pleasure derived from the task, such as meticulous detailing of a cherished old car. Paul’s use of the phrase, however, could be paraphrased “acts of love.” It refers to the deeds the Thessalonians have done because of the love they have been given by God. Timothy returned from Thessalonica with the happy news that they were manifesting love (1 Thess 3:6). It is likely that they have provided for one another financially (4:9–10). They have also endured in hope of our Lord Jesus Christ and his return in glory despite experiencing hardships (3:1–10; 4:13).

Paul’s use of the word brothers (NRSV: “brothers and sisters”) is so familiar that it would be easy to miss its significance. The most common meaning of the Greek word for “brother” (adelphos) was the same as the English word, but it could also be used to refer to more distant relations (1 Chron 23:21–22), fellow Hebrews (Exod 2:11), or fellow members of various other kinds of religious or political groups.8 In the teaching of Jesus, the primacy of biological relations is challenged when he defines those who do the will of God as his mother, sisters, and brothers (Matt 12:49–50; Mark 3:34–35; Luke 8:20). When Paul calls Gentiles his “brothers,” as here, it suggests that the bond between Christians transcends ethnic dividing lines.

The language of family is more important in 1 Thessalonians than in any other of Paul’s Letters. The occurrence of the word “brothers” dwarfs its use in every other letter, occurring at an average of once almost every four verses. First Corinthians, which is often noted for its family language, mentions “brothers” only once every eleven verses. In 1 Thessalonians Paul also compares his relationship with them during their short time together to a nursing mother cherishing her dear children (2:7) and to a father with his sons (2:11). Being torn away from the Thessalonians has left Paul “orphaned” (see 2:17), but when they were together Paul was like a little child (2:7).9 He also exhorts them to “brotherly love” (see 4:9–12). And of course God is called the Father and Jesus is his Son. This dense web of familial language reminds the Thessalonians that they have been “adopted”—as Paul would put it in later letters (see Rom 8:15, 23; Gal 4:5; Eph 1:5)—into the family of God.

Paul gives thanks because the Thessalonian Christians were chosen (eklogē) by God. The only other time that Paul uses the word eklogē is in Rom 9–11 while discussing how God chose Israel from all the nations. It is striking that he uses it here to describe a congregation that consisted of former pagans. This shows that God’s election has extended beyond the boundaries of Israel to embrace the nations as well. Paul’s language of the Thessalonians being both loved and chosen by God echoes Moses’s explanation of Israel’s election in the book of Deuteronomy:

It was not because you [Israel] are more numerous than all the peoples that the LORD set his heart on you and chose you; for you are really the smallest of all peoples. It was because the LORD loved you and because of his fidelity to the oath he had sworn to your ancestors, that the LORD brought you out with a strong hand and redeemed you from the house of slavery, from the hand of Pharaoh, king of Egypt. (Deut 7:7–8 [italics added])

As Gordon Fee puts it, “The point, of course, is that Israel did nothing to deserve God’s redemption from slavery and election as his people; it was God’s doing altogether.”10 Just as divine love is the root cause of Israel’s election and subsequent deliverance from Egypt in the exodus, so too it is divine love that has brought the Thessalonians into the family of God.

Reflection and Application (1:3–4)

This mention of faith, love, and hope is probably the earliest written occurrence of what later Christian tradition would identify as the three “theological virtues.” This triad appears again in 5:8 and in Paul’s subsequent letters (Rom 5:1–5; 1 Cor 13:8–13; Gal 5:5–6; Col 1:4–5). Faith, love, and hope are known as theological virtues because they are gifts from God that make it possible for “Christians to live in a relationship with the Holy Trinity” (Catechism 1812). Though Paul does not use the phrase “theological virtue,” this is a deeply Pauline insight. Paul describes faith as a gift from the Spirit (Gal 5:22) that comes through the word of Christ (Rom 10:17). Hope comes by God’s grace (2 Thess 2:16) through the Spirit (Gal 5:5). Love is poured into our hearts by the Holy Spirit (Rom 5:5; Gal 5:22) and compels us to live no longer for ourselves “but for him who for their sake died and was raised” (2 Cor 5:15).

Though faith, hope, and love are pure, undeserved gifts from God, it would be a mistake to conclude that they require no effort on our part. To think so would be to fail to recognize just how good these gifts are. When faith, love, and hope are received, they become truly ours. As Charles Cardinal Journet puts it, “God gives us, in Christ, the power to assent to him.” Yet “it is my own assent. . . . At times it will have caused me real anguish, will have entailed victory over my passions—it is indeed my own. But it is due even more to God than to me, and the first thought that will come to my mind will be to say, ‘Thanks be to you, my God, for having given me the power to answer your call; to you be the glory.’”11

Joy in Suffering (1:5–8)

5For our gospel did not come to you in word alone, but also in power and in the holy Spirit and [with] much conviction. You know what sort of people we were [among] you for your sake. 6And you became imitators of us and of the Lord, receiving the word in great affliction, with joy from the holy Spirit, 7so that you became a model for all the believers in Macedonia and in Achaia. 8For from you the word of the Lord has sounded forth not only in Macedonia and [in] Achaia, but in every place your faith in God has gone forth, so that we have no need to say anything.

NT: Matt 16:21–28; 1 Cor 4:15; 11:1; Eph 5:1

Catechism: the Holy Spirit, 686–747

The thanksgiving that began in verse 2 continues in verse 5. Paul gives thanks to God because the Thessalonians were chosen by God, and in verse 5 Paul explains how he knows this. A paraphrase of verses 4–6 will help illuminate Paul’s point:

How do we know that God chose you? Because our preaching wasn’t just talk. God enabled us to preach with power, by means of the Holy Spirit, and with confidence. We also know that God chose you because you became imitators of us and of the Lord by receiving the word in the midst of great affliction with joy from the Holy Spirit.

Paul believed that there were clear signs of divine assistance when he was working in Thessalonica. He did not come in word alone. God displayed power and filled the apostles with conviction.12 It is possible that this “power” refers to God working through Paul’s preaching (Gal 3:1–5), or it may refer to miracles that accompanied his words. Paul describes himself as a miracle-worker on other occasions, such as when he tells the Romans that it is his duty to “lead the Gentiles to obedience by word and deed, by the power of signs and wonders, by the power of the Spirit” (Rom 15:18–19; see also 2 Cor 12:12). Theodoret of Cyrus puts it this way: “We didn’t just offer you instructive words. We demonstrated the truth of the words by performing wonders.”13

The Thessalonians were gripped by the Holy Spirit, who empowered them to become imitators of the apostles by accepting the gospel with joy, though they were suffering great affliction at the hands of other inhabitants of the city (2:14). For Paul, joy in the midst of suffering for the gospel is a clear sign that God is at work in a person (see 2 Cor 8:1–2). Through their joy in suffering the Thessalonians became imitators not only of the apostles but also of the Lord himself.14 What does this mean? St. John Chrysostom notes that Paul must be referring to Jesus’s willing self-emptying in his passion: “How were they imitators of the Lord? Because he also endured many sufferings but did not grieve. Rather, he rejoiced, for he came to this gladly. For our sakes he emptied himself [Phil 2:7].”15 Paul does not retell here the full story of how Christ emptied himself for our sakes, but it is important to note that his words presuppose that the Thessalonians understand what he means. The new Christians in Thessalonica know that those who rejoice in suffering imitate Jesus, who “died for us” (1 Thess 5:10). This was part of the gospel message that they received when Paul was with them, as was the news that those who follow Jesus will also experience suffering (3:2–3).

Figure 3. St. Catherine of Siena by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. [Public domain / WikiArt.org]

The Thessalonians have not been Christians for long, but already the news of their joyful reception of the gospel has spread all over Greece and in every place. Even if we assume that Paul is exaggerating a bit in his exuberance—“Everyone is talking about it!”—we understand that the young Thessalonian church has made a big impression. They have become a model for all the believers in the region. The word translated as “believers” is one of Paul’s favorite ways of describing members of the church. By choosing this translation, the NABRE highlights the importance of “believing” in the claims of the gospel. The word translated as “believe” is pisteuō; the corresponding noun is pistis. “Believe” is one possible translation of pisteuō, but pisteuō can also denote faith, trust, or faithfulness, among other things. There is a world of difference between mere belief—simply thinking that something is true—and faithfulness, which requires not just belief but faithful action as well. The only way to decide how these Greek words should be translated in a given case is to study their context. Paul sometimes uses pistis and related words to refer to belief or intellectual assent (Rom 10:9). There are many occasions, however, when Paul’s pistis language is best translated with the word “trust.” When we say we trust someone—say, a friend or a spouse—we mean that we rely on that person to be good to us.16 To trust someone is to give oneself over to that person and (to one degree or another) make oneself vulnerable to him or her. A good example of pistis as trust appears in 1 Cor 10:13, where Paul uses the adjectival form pistos while warning the Corinthians not to fall into idolatry: “God is trustworthy [pistos]: he will not leave you to be tempted beyond your strength but with the testing he will make a way out so that you will be able to endure it” (my translation). Paul encourages the Corinthians to trust God to stand by them in their times of temptation. Here in 1 Thessalonians Paul describes the church as those who rely on God in times of suffering. Arguably, then, “the faithful” or “the trusting” would be a better translation here than “believers.”

Reflection and Application (1:5–8)

For modern people, it is an insult to be called an imitator. We are frequently told how important it is to “be yourself.” As Ralph Waldo Emerson puts it, “Insist on yourself; never imitate.”17 In striking contrast, Paul reminds the Thessalonian church how they learned to imitate him (1 Thess 1:6) and the churches in Judea (2:14). Did Paul expect the Thessalonians to be pleased when they heard this? Isn’t this tantamount to calling them weak-minded followers with nothing to offer? How would the people in your local church respond if the pastor commended them for “imitating me”?

In order to understand Paul, we must grasp an important difference between his culture and ours. In Paul’s day popular teachers frequently appealed to imitation as a path to growth in virtue. In contrast, since the late eighteenth century, Westerners have been increasingly convinced that everyone must find his or her own way. To discover your own unique path, we are told, you must search inside yourself rather than conforming to expectations imposed on you from the outside, whether from religion, family, or the wider society. To quote Emerson once again, “No law can be sacred to me but that of my nature. . . . The only right is what is after my constitution; the only wrong what is against it.”18 Or, as ads for cars, clothing, and beer sometimes put it, “Express yourself.”

There are serious problems with the “be yourself” approach to life, one of which is a naïve individualism that imagines that we can live good lives on our own. The Thessalonian Christians were embarking on a new life of worshiping the living God. Having only recently turned from a life of “lustful passion” (4:5), they needed to learn new habits to sustain a life of chastity (4:1–8), sobriety (5:1–8), and care for the weak (5:14), but they couldn’t do this on their own. Like us, they needed examples to show them what it means to follow Jesus. This is what they found in Paul, Silvanus, and Timothy. Today we have many similar examples both among those we know personally and through the lives of the saints, a “great cloud of witnesses” (Heb 12:1) that has continued to grow.

The Living and True God (1:9–10)

9For they themselves openly declare about us what sort of reception we had among you, and how you turned to God from idols to serve the living and true God 10and to await his Son from heaven, whom he raised from [the] dead, Jesus, who delivers us from the coming wrath.

OT: Ezek 7:19; Zeph 1:15–18; Sir 5:6–7

NT: Matt 3:7; Luke 3:7; Rom 1:18–32

Catechism: the living God, 205

This short description of what people are saying about the Thessalonians is packed with important hints about the identity of the Thessalonian converts and about the gospel message that they received from Paul. The mention of turning away from idols suggests that the converts were Gentiles or non-Israelites. We don’t know as much about religious life in ancient Thessalonica as we would like because the bustling modern city of Thessaloniki makes archaeological research difficult. We do know that Thessalonica was the home of many cults dedicated to a number of different deities, such as Isis, an Egyptian goddess and giver of immortality, or Dionysus, the Greek god of wine and fertility.19 Among the deities that arguably would have caused the most trouble for the new Christians in Thessalonica were the Roman emperors themselves. When Augustus became emperor of Rome, he had his adopted father, Julius Caesar, declared divine. As Caesar’s son, Augustus was called the son of a god. Thessalonica traditionally was loyal to Rome, and the city seems to have embraced worship of both deceased and living emperors. Coins from Thessalonica bear the image of Caesar and the word “God” (Greek theos). During Augustus’s reign a temple was built in Thessalonica for the worship of the emperor. An inscription from the time refers to the appointment of a priest of “Emperor Caesar Augustus son of god.”

Figure 4. Divus (Divine) Julius Caesar with ΘEOC inscription (obverse) and Octavian with ΘECCAΛO-NIKEΩN (reverse). Struck circa 28/27 BC in Thessalonica, Macedon.[Lot 23296 / Numisbids.com]

Figure 5. Divus Julius Caesar with ΘEOC inscription (obverse). Struck circa AD 14 in Thessalonica, Macedon. [Lot 208 / Numisbids.com]

Figure 6. Divus Julius Caesar with ΘEOC inscription (obverse). Likely struck in Thessalonica, Macedon, between 27 BC and AD 14. [CNG 108, Lot: 449 / CNGcoins.com]

Paul heightens the difference between Jewish monotheism and pagan worship by contrasting idols with the living and true God. In biblical and postbiblical traditions, the phrase “the living God” is used to express God’s superiority to pagan deities, which are by implication dead or false gods. In Dan 14:5, King Cyrus asks Daniel why he refuses to worship Bel. Daniel responds, “Because I do not revere idols made with hands, but only the living God who made heaven and earth and has dominion over all flesh.”20 The phrase “the living God” also frequently connotes God’s power to punish those who oppose Israel. For instance, before crossing into the promised land Joshua tells the Israelites, “By this you will know that there is a living God among you: he will certainly drive out before you the Canaanites and the Hittites and the Hivites and the Perizzites and the Girgashites and the Amorites and the Jebusites” (Josh 3:10 [my translation]).21 The mention of coming wrath hints at something similar here. Paul warns that at an unknown time a day of judgment will arrive (1 Thess 5:1–5), calling to account all evildoers.

Paul’s description of the one he calls God’s Son in verse 10 shows that he had taught the Thessalonians that Jesus, a flesh-and-blood human being who had recently been killed in Judea, was God’s Son (1:5–6; 2:14–15; 5:9–10). God raised Jesus from the dead, and Jesus now resides in heaven with God, where he acts jointly with God the Father on behalf of the Church (1:1; 3:11). The Thessalonians accepted this message, turned from idolatry, and now have the privilege of serving God while they await the return of Jesus from heaven. By reminding the Thessalonians of their shared belief, Paul prepares them for his further instruction on the fate of those who die before the Lord’s return (4:13–18).

Reflection and Application (1:9–10)

It is difficult for many of us to know how to feel about Paul’s insistence that God’s “wrath” is coming. Paul mentions it almost in passing here, but he picks up and develops this theme repeatedly in the letters to the Thessalonians. How could a good God be the source of wrathful judgment? How is it possible to worship such a God? One way of thinking about this question is to imagine its opposite. What would it mean if God never brought judgment? What if God’s final response to all human behavior was a shrug of the shoulders—or, worse, an affirmation that all the evil we have inflicted on one another is just fine? It is curious that we have become uncomfortable with divine wrath in an age in which humans have unleashed evils on one another unlike any the world had seen before. C. S. Lewis gets to the heart of the matter:

When Christianity says that God loves man, it means that God loves man: not that He has some “disinterested,” because really indifferent, concern for our welfare, but that, in awful and surprising truth, we are the objects of His love. You asked for a loving God: you have one. . . . Not a senile benevolence that drowsily wishes you to be happy in your own way, not the cold philanthropy of a conscientious magistrate, nor the care of a host who feels responsible for the comfort of his guests, but the consuming fire Himself, the Love that made the worlds, persistent as the artist’s love for his work and despotic as a man’s love for a dog, provident and venerable as a father’s love for a child, jealous, inexorable, exacting as love between the sexes.22

If there is no divine wrath, it is hard to see how there could be divine love. The scandal of God’s wrath is inherent to the gospel itself.

1. The scribe could have been a fourth, unnamed person. See, e.g., Rom 16:22, where the previously unnamed scribe Tertius greets the Romans. Some have suggested that Silvanus himself was the scribe, noting that 1 Pet 5:12 names a Silvanus as the one through whom that letter was written.

2. Rom 16:21–23; 1 Cor 1:1; 16:19–21; Phil 1:1; 4:21–22; Col 1:1; 4:7–14.

3. Michael J. Gorman, Inhabiting the Cruciform God: Kenosis, Justification, and Theosis in Paul’s Narrative Soteriology (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009), 115.

4. See, e.g., the letter of the Jerusalem church in Acts 15: “The apostles and the presbyters, your brothers, to the brothers in Antioch, Syria, and Cilicia of Gentile origin: greetings [chairein]” (v. 23).

5. Homiliae in epistulam i ad Thessalonicenses (PG 62:393 [my translation]).

6. Beverly Roberts Gaventa, First and Second Thessalonians, IBC (Louisville: John Knox, 1998), 14.

7. Homiliae (PG 62:394 [my translation]).

8. BDAG.

9. In 2:17 the NABRE translates the verb aporphanizō as “we were bereft” rather than “we were orphaned.” There is an important †textual variant in 2:7. Paul may have described himself as “gentle” rather than as an infant. See the commentary on that verse for a discussion of the variant and of the surprising image of Paul as an infant.

10. Gordon D. Fee, The First and Second Letters to the Thessalonians, NICNT (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009), 30.

11. Charles Cardinal Journet, The Meaning of Grace, trans. A. V. Littledale (New York: P. J. Kenedy, 1962), 58–59.

12. The words “much conviction” might refer to the Thessalonians’ conviction. See Abraham J. Malherbe’s argument to the contrary in The Letters to the Thessalonians: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, AB 32B (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 112–13.

13. Interpretatio in xiv epistulas sancti Pauli (PG 82:629 [my translation]).

14. On “imitation,” see also 1 Cor 4:16; 11:1; Gal 4:12; Eph 5:1; Phil 3:17.

15. Homiliae (PG 62:395 [my translation]).

16. When a bank extends someone credit—from credo, the Latin word that frequently translates pisteuō in the Vulgate—it does so because it has reason to trust that person to pay it back.

17. Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Self-Reliance,” in Emerson’s Essays on Manners, Self-Reliance, Compensation, Nature, Friendship (New York: Longmans, 1915), 54.

18. Emerson, “Self-Reliance,” 31. For an illuminating discussion of how the sentiments expressed by Emerson and other Romantics have become ubiquitous in the last fifty years, see Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), 473–504.

19. Karl P. Donfried, “The Cults of Thessalonica and the Thessalonian Correspondence,” NTS 31 (1985): 336–56.

20. See also 1 Sam 17:26, 36.

21. See also Deut 5:26; 2 Kings 19:4 // Isa 37:4.

22. C. S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain (1940; repr., New York: HarperCollins, 2009), 39–40.