Paul’s Behavior in Thessalonica

1 Thessalonians 2:1–8

In this section Paul continues to retell the story of his relationship with the Thessalonians.1 In these verses and on into 2:9–12, Paul has much to say about what he, Silvanus, and Timothy were not like in Thessalonica, denying that they were greedy, deceptive, pushy, or sycophantic, among other things. Paul insists that he and his companions treated the Thessalonians like family. Scholars have not come to a consensus regarding why Paul spends so much time explaining what he did and did not do. There are two main explanations on the table. The first, which was dominant in modern scholarship until about thirty years ago, argues that Paul is defending himself against some unnamed detractor, an opponent from within the church or outside it.2 The second view, which owes much to the work of Abraham Malherbe, reads 2:1–12 as †paraenesis, reminding the Thessalonians of how the apostles behaved and exhorting them to follow the apostolic example.3 Which interpretation has the better argument? Though it certainly is possible that there were rumors around the city of Thessalonica that Paul was a charlatan, there are good reasons to doubt that Paul’s principal concern is to defend himself against attacks. This passage is quite similar to other first-century descriptions of how a good teacher should behave (see sidebar, “Dio Chrysostom,” p. 53), and the rest of the letter gives no indication that Paul is on the defensive. On the contrary, Timothy reported that the Thessalonians continued to hold the apostles in high regard (3:6). Perhaps the strongest evidence that this section should be read as moral exhortation is the fact that most of the behaviors described in 2:1–12 resurface later in the letter when Paul discusses the areas in which the Thessalonians need to improve. He highlights the apostles’ courage despite persecution (2:1–2), their attempt to please God and be found blameless (2:4, 6, 10), their avoidance of “impurity” (see 2:3), their hard work to avoid being a burden on others (2:9; see also 2:5), and their love for the Thessalonians (2:8) and gentle admonishment of them (2:7–8, 11–12). All of these issues come up again in the letter—often using the very same words—but in reference to the Thessalonians’ own moral progress.4 When reading 2:1–8 as well as 2:9–12, therefore, one ought not imagine Paul feeling hurt and defensive (see 2 Cor 11 for a good example of that). Instead, it is best to read this passage like the rest of the letter—that is, as an attempt to build up the Thessalonians’ faith by strengthening his relationship with them and by giving them an example to imitate.

Preaching amid Opposition (2:1–2)

1For you yourselves know, brothers, that our reception among you was not without effect. 2Rather, after we had suffered and been insolently treated, as you know, in Philippi, we drew courage through our God to speak to you the gospel of God with much struggle.

NT: Acts 16:11–17:10

Paul’s mission to Thessalonica was among his most successful ventures, but it did not begin without difficulties. Before Paul arrived in Thessalonica he suffered and was insolently treated in nearby Philippi. Readers of Acts will think of how the chief magistrates of the city had Paul and Silas stripped, beaten, flogged, and thrown into prison for “advocating customs that are not lawful” (Acts 16:20–24). His difficulties continued in Thessalonica, where he faced much struggle. According to Acts 17:5–10, Paul was accused of treasonous behavior and was forced to flee Thessalonica during the night. In spite of these difficulties, Paul and his companions drew courage through our God and spoke boldly. Paul’s point is not that they were unusually brave but that God was working in them to enable them to speak the gospel despite the difficulties they encountered.

God was at work in Paul to ensure that his time in Thessalonica was not without effect. The words “without effect” (kenē) could also be translated as “in vain” or “empty.” On a number of occasions Paul speaks of his confidence that he is not laboring or running “in vain” (see especially 1 Cor 15:58; Gal 2:2; Phil 2:16). In 1 Thess 3:5 Paul reveals that he had been worried that the Thessalonians had fallen away and that his work had been “in vain” (eis kenon). This language echoes Isa 65:17–25, where God promises to create a new heavens and new earth, in which God’s chosen “shall not toil in vain.” Paul believed that this new creation had already broken into this world through the death and resurrection of Jesus, and that the efficacy of his preaching was due to the power of Christ. As he told the Corinthians, “Be firm, steadfast, always fully devoted to the work of the Lord, knowing that in the Lord your labor is not in vain” (1 Cor 15:58). His confidence was based not on his own speaking abilities or anything else of his, but on the Holy Spirit (1 Thess 1:5), who was at work.

The Character of Paul’s Ministry (2:3–8)

3Our exhortation was not from delusion or impure motives, nor did it work through deception. 4But as we were judged worthy by God to be entrusted with the gospel, that is how we speak, not as trying to please human beings, but rather God, who judges our hearts. 5Nor, indeed, did we ever appear with flattering speech, as you know, or with a pretext for greed—God is witness— 6nor did we seek praise from human beings, either from you or from others, 7although we were able to impose our weight as apostles of Christ. Rather, we were gentle among you, as a nursing mother cares for her children. 8With such affection for you, we were determined to share with you not only the gospel of God, but our very selves as well, so dearly beloved had you become to us.

NT: Luke 22:24–30

Catechism: ministers are servants of all, 876

Lectionary: 1 Thess 2:2b–8; Memorial of Saint Augustine of Canterbury; Memorial of Saint Pius X

Paul denies that he preached out of delusion, impure motives, or deception. The first word of the three, planē, probably refers to a mistaken belief (see Rom 1:27; 2 Thess 2:11). The third word, “deception” (dolos), refers to leading others into a mistaken belief. By combining “delusion” and “deception,” Paul denies that he was deceived and also that he was deceiving. The word translated as “impure motives” is akatharsia, which means “impurity” or “uncleanliness.” This word could refer to impure or immoral behavior in general, but in Paul’s Letters akatharsia usually refers to sexual immorality (Rom 1:24; 2 Cor 12:21), including one instance later in this letter (1 Thess 4:7). Then as now, there were teachers who used their influence to coerce others into sexual relationships. Paul was confident that the Thessalonians would attest that he was not one of those teachers.

Instead of speaking deceitfully or with ulterior motives, they preached in a manner appropriate for those judged worthy by God to be entrusted with the gospel. One might compare this description to an employer who first tests a potential employee to see if she or he has what it takes to do the job and then continues to watch the new hire to ensure that good work is done. God has tested Paul and his companions and found them worthy of being “entrusted” with the gospel. Though they have received this trust, Paul is keenly aware that God continues to test his work. St. Basil the Great cites this verse along with Matt 6:1–2 to argue that Christians should do their work as if they were standing before God: “We should not wish to put ourselves on display . . . but should instead act as if we are speaking for the glory of God in his presence.”5

Paul denies that he used flattering speech. Aristotle defined a flatterer as someone who pleases others for the sake of self-advantage.6 In Paul’s own time, Dio Chrysostom complained about the abundance of flatterers among those who purported to be teachers (see sidebar, “Dio Chrysostom,” p. 53). A pretext for greed goes hand in hand with flattery. The word “pretext” (prophasis) refers to an excuse for bad behavior, such as a preacher who pretends to have the listeners’ best interests at heart, while really “preaching for money,” as Theodoret of Cyrus puts it while commenting on this verse.7 Paul denies that he was after their money, a claim that he can back up on the fact that he supported himself through manual labor. Similarly, Paul did not seek praise from people, either from the Thessalonians or from others. The word translated as “praise” (doxa) can refer to complimentary words, gifts, or special honors bestowed on someone important. St. John Chrysostom argues that apostles deserved “praise” beyond that of royal emissaries because they were sent by God, yet they thought it better to remain humble.8

In 2:5 Paul says that God is witness to his upright behavior in Thessalonica. In 2:10 he refers to both the Thessalonians and God as “witnesses.” The word “witness” (martys) was common in legal or contractual settings referring to those who could testify to something, such as the requirement in Deut 19:15 that two or three witnesses are necessary to convict someone of a crime. In 1 Sam 12 the prophet Samuel looks back on his career leading Israel and calls God to witness to the fact that he was honest and upright as a leader. Samuel says, “The Lord is witness [martys] among you . . . that you have found nothing stolen in my hand” (LXX 1 Sam 12:5 [my translation]).9 Similarly, Paul is confident that God will testify to his upright behavior with the Thessalonians. How can God be a witness? Did Paul expect God to testify on his behalf? Other references to God as witness in Scripture provide hints as to what Paul means. Naming God as a witness expresses the belief that God knows our actions and thoughts. As Wis 1:6 puts it, evil words will be punished because “God is the witness [martys] of the inmost self / and the sure observer of the heart / and the listener to the tongue” (see also LXX Mal 3:5; Jer 36:23 [ET 29:23]; 49:5 [ET 42:5]). By calling God as witness, then, one expresses confidence that God knows the truth, even if others do not.10

As apostles of Christ, Paul and his companions had authority given to them by Jesus himself (1 Cor 9:1; 15:1–11). As bearers of this authority, Paul says that they were able to impose our weight, or, as we might put it, they could have “thrown their weight around,” but they thought it better to be humble. In the Greek this phrase is connected to the preceding verse, where Paul denies that he sought glory from human beings. Then as now, authority figures often wore their power on their sleeves by seeking praise and by reminding those around them of their special status. Paul may also be referring to the way he, Silvanus, and Timothy worked hard so as not to place financial burdens on the Thessalonians. The word translated as “weight” is baros. Paul uses a related word a few verses later when he recalls how they worked “not to burden [epibareō] any of you” (1 Thess 2:9 [see also 2:5; 2 Thess 3:8]). Apostles had the right to expect financial assistance from the churches, a right that was based on a command of Jesus (see 1 Cor 9:1–18, especially v. 14). Paul, however, frequently chose not to accept financial assistance because, as he puts it in 1 Cor 9:12, “We endure all things rather than give hindrance to the gospel of Christ” (my translation). He gave up his right to payment in order to “offer the gospel free of charge” (1 Cor 9:18).

This is the earliest occurrence of the word “apostle” (apostolos) in a Christian text, and the only occurrence in the Thessalonian correspondence. Does the plural “apostles of Christ” indicate that Silvanus and Timothy were also considered apostles? The answer to this question depends in part on whether one thinks that the letter is from all three men or only from Paul. As noted in the commentary on 1 Thess 1:1, there is good reason to suppose that the Thessalonians would have read the letter as if it were from all three men, with Paul as the principal voice. Nevertheless, it is highly unlikely that Timothy was considered an apostle. In later letters of Paul, Timothy is not given the title “apostle” in the opening address (see 2 Cor 1:1). It is harder to judge in the case of Silvanus. At the conclusion of 1 Thessalonians Paul alone solemnly commands his audience to read the letter to “all the brothers” (5:27), which could indicate that they recognized that Paul had a unique authority.

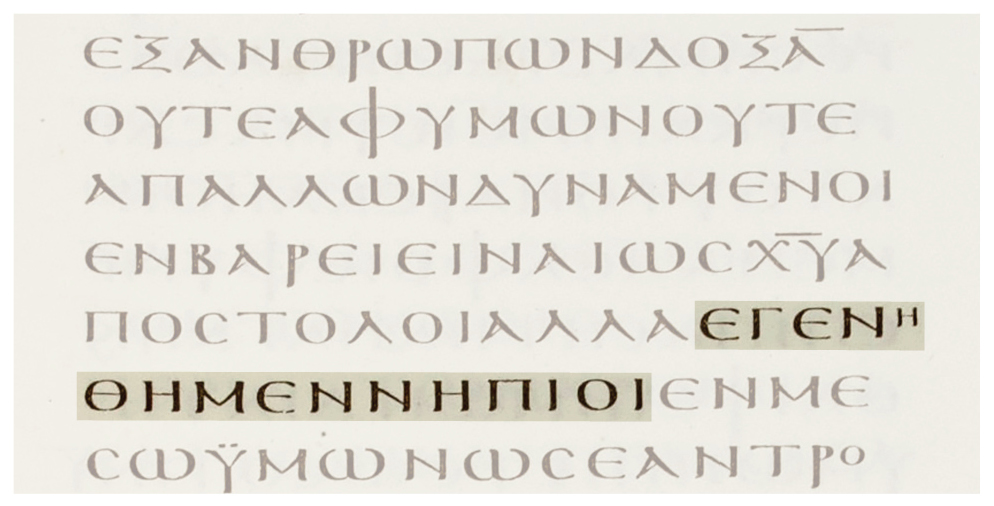

Verse 7 contains a famous †textual variant. Some ancient manuscripts have “we were infants among you” rather than we were gentle among you. In Greek the difference between “we were infants” (egenēthēmennēpioi) and “we were gentle” (egenēthēmenēpioi) is only one letter, so it would have been easy for scribes to change one into the other unintentionally. Scholars are divided on the question of which of these is more likely to have been written by Paul. This may seem like a technical question of relevance only to scholars, but this one letter makes an enormous difference for how one reads the entire passage.

The most reliable ancient manuscripts tend to support “infants.” Despite this evidence, some find it hard to believe that Paul would have said, “We were infants among you, as a nursing mother cares for her children.” That would be an abrupt shift of imagery, even by Paul’s standards.11 Those who think that Paul wrote “infants” respond by arguing that the NABRE and other translations have incorrectly punctuated this passage. Verses 2:1–8 feature a series of “not X but Y” contrasts.12 Following this pattern, verses 5–8 should be punctuated like this:

Sentence 1: Nor, indeed, did we ever appear with flattering speech, as you know, or with a pretext for greed (God is witness), nor did we seek praise from human beings, either from you or from others (though we were able to impose our weight as apostles of Christ), but we became infants among you.

Sentence 2: Just as a nurse cares for her own children, so, in our deep longing for you, we were pleased to share with you not only the gospel of God but also our very selves, because you have become beloved to us. (my translation)

Paul doesn’t say “we were infants like a nurse.” Rather, the phrase “we became infants among you” completes the thought that began in verse 5. Then, in the second half of verse 7, Paul picks up a new image: the apostles were like a nurse cherishing her children. The shift from “infants” to nursing mother is somewhat abrupt, but this is not unusual for Paul (see Gal 4:19).

Figure 7. First Thessalonians 2:7 in Codex Vaticanus, which says (in highlight), “We became infants.” [Image used by permission from the Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts (www.csntm.org).]

If Paul wrote “gentle,” he would be explaining that he did not throw his weight around as an apostle, preferring instead to be kind to the Thessalonians. If, as I suggest, Paul wrote “infants,” his point would be that he was humble and innocent.13 Rather than making his weight felt in Thessalonica, Paul humbled himself and became like a child. The Church Father Origen saw a link between this verse and Jesus’s teaching that those who want to be great must become like children. After discussing Matt 18:1–6 and Luke 9:48 (“For the one who is least among all of you is the one who is the greatest”), Origen writes, “He who humbles himself and ‘becomes an infant in the midst’ of all the faithful, though he be an apostle or bishop . . . is the ‘little one’ pointed out by Jesus.”14 In other words, by making himself small, Paul shows the path to greatness for all who would follow the crucified Messiah.

The image of apostles as children is followed by the even more surprising maternal image of apostles as nurses. The NABRE translates the end of verse 7 as a nursing mother cares for her children. The word trophos (“nursing mother”) could refer to a nursing mother, but usually it referred to a woman who was hired to breastfeed or otherwise nourish a child.15 Wet-nurses were common in the ancient world, and the children they nourished frequently remembered them fondly.16 Indeed, though this image may seem bizarre to us, for those with firsthand experiences of wet-nurses, Paul’s language would have painted a vivid picture of how he carried himself as an apostle. St. John Chrysostom used the image of the nurse to summarize all of 2:1–8: “As a nurse cares for her own children, so it is necessary for a teacher to be. The nurse does not flatter that she may obtain glory. She does not ask her little children for money. She is not burdensome or severe with them. Are not nurses even more kind than mothers?”17

The vividness of Paul’s self-description is better understood in light of the alternate punctuation suggested above. Though the NABRE puts a period at the end of verse 7, in Greek it is likely that the sentence continues into verse 8 and provides further explanation of what Paul means by comparing himself to a nurse: “Just as a nurse cares for her own children, so, in our deep longing for you, we were pleased to share with you not only the gospel of God but also our very selves, because you have become beloved to us” (my translation). Paul gave his whole self to the Thessalonians, just as a nurse nourishes her children from her own body. He did not simply tell the Thessalonians about the gospel. He lived it by giving himself to them in imitation of Jesus, “who died for us, so that . . . we may live together with him” (1 Thess 5:10).

Reflection and Application (2:3–8)

These verses are an incisive description of common errors that have destroyed the credibility and effectiveness of many ministers. Greed, love of the limelight, and superciliousness have derailed many who wanted to serve the Church. Paul was already guarding against these dangers in the Church’s earliest days, and two thousand years later we are all too aware that these problems have not gone away. Paul’s description of leadership through patient, self-giving care, humility, and even vulnerability remains a powerful corrective to the human tendency to dominate others and work for personal gain. His teaching echoes that of his Lord, who had taught that one must become like a child in order to enter the kingdom (Matt 18:3) and that leaders in the Church must assume a lowly status, just as he did (Matt 20:24–28; Luke 22:24–27). While preaching on 1 Thess 2, St. Augustine makes a comment that gets to the heart of the matter: “There is no greater proof of charity in Christ’s church than when the very honor which seems so important on a human level is despised.”18

Ultimately, however, a Christian’s confidence rests not on the ability of authority figures to heed Paul’s and Jesus’s teaching, but on the faithfulness of God. Though the failures of ecclesiastical leaders are no small matter (Matt 18:6; 24:45–51; James 3:1), the weaknesses and failings of the Church’s ministers serve to show forth the power of God, who works both through our obedience and in spite of our disobedience. As Paul puts it when describing his own ministry, “We hold this treasure in earthen vessels, that the surpassing power may be of God and not from us” (2 Cor 4:7).

1. The recounting of their relationship doesn’t end until 3:10.

2. Some cite Acts 17:1–9 as evidence that the opponents were certain Jews in Thessalonica. Recent advocates of the view that Paul is defending himself include Jeffrey A. D. Weima, 1–2 Thessalonians, BECNT (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2014), 121–25.

3. Abraham J. Malherbe, “‘Gentle as a Nurse’: The Cynic Background to 1 Thessalonians 2,” in Paul and the Popular Philosophers (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1989), 35–48; see also Malherbe’s other works on 1 Thessalonians, including his commentary The Letters to the Thessalonians: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, AB 32B (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 153–63.

4. On enduring persecution, see 1:2–6; on pleasing God and being found blameless, see 3:13–4:1 and 5:23; on avoiding impurity, see 4:7; on working so as not to burden others, see 4:9–12; on love for others in the church, see 3:12; on the gentle admonishment of others in the church, see 5:14.

5. Regulae morales 31.836 (my translation). See also Regulae morales 31.720.

6. Nicomachean Ethics 2.7.

7. Interpretatio in xiv epistulas sancti Pauli (PG 82:633 [my translation]).

8. Homiliae in epistulam i ad Thessalonicenses (PG 62:402).

9. See also LXX Gen 31:44; 1 Sam 20:23; 20:42; Acts 5:32.

10. Matthew V. Novenson, “‘God Is Witness’: A Classical Rhetorical Idiom in Its Pauline Usage,” NovT 52 (2010): 355–75.

11. See the footnote in the NABRE: “Many excellent manuscripts read ‘infants’ (nēpioi), but ‘gentle’ (ēpioi) better suits the context here.”

12. Verses 1–2 say that their reception was not in vain, but rather (alla) the apostles were emboldened to speak. Verses 3–4 say that their exhortation was not from impure motives, and so on, but rather (alla) they spoke as those entrusted by God. Verses 5–7 continue this pattern: the apostles did not use flattering speech, and so on, but rather (alla) they were like infants. The NABRE ignores this pattern in order to accommodate the poorly attested “gentle.” For an extended argument, see Gordon D. Fee, The First and Second Letters to the Thessalonians, NICNT (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009), 65–72.

13. See the similar use of the related verb in 1 Cor 14:20: “In respect to evil be like infants [nēpiazō], but in your thinking be mature.”

14. Commentarium in evangelium Matthaei 13.29 (my translation). See the use of “infant” (nēpios) to define the attitude of those who understand Jesus and will enter the kingdom in Matt 11:25; Luke 10:21. See also Matt 21:16.

15. LSJ; BDAG. In the Septuagint trophos translates a Hebrew word that means “one who gives suck.”

16. Keith R. Bradley, “Wet-nursing at Rome,” in The Family in Ancient Rome: New Perspectives, ed. Beryl Rawson (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1986), 220; Beverly R. Gaventa, “Apostles as Babes and Nurses in 1 Thessalonians 2:7,” in Faith and History: Essays in Honor of Paul W. Meyer, ed. John T. Carroll, Charles H. Cosgrove, and E. Elizabeth Johnson (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1990), 201.

17. Homiliae (PG 62:402 [my translation]). In Greek this is a series of rhetorical questions. The implied answer is obvious in Greek but not in English, so I have taken the liberty of translating loosely for clarity’s sake.

18. Sermons 10.8. Cited in Colossians, 1–2 Thessalonians, 1–2 Timothy, Titus, Philemon, ed. Peter Gorday, ACCS 9 (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2000), 65.