Events Presaging the Day of the Lord

2 Thessalonians 2:1–17

The Thessalonian Christians seem to have worried that the day of the Lord had already come. One of the main reasons Paul wrote 2 Thessalonians was to address this confusion, and his response presents some of the most puzzling and fascinating material in all his letters. He assures them that certain events must take place prior to the Lord’s return: a great apostasy, and the revelation of “the lawless one,” a figure opposed to God who deceives many. After these events have played out according to the preordained timetable, Jesus will return.

Confusion about the Day of the Lord (2:1–2)

1We ask you, brothers, with regard to the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ and our assembling with him, 2not to be shaken out of your minds suddenly, or to be alarmed either by a “spirit,” or by an oral statement, or by a letter allegedly from us to the effect that the day of the Lord is at hand.

NT: 1 Thess 4:13–5:11; 2 Tim 2:14–19

This section continues the discussion of the Lord’s return, which Paul refers to here as Jesus’s parousia (coming) and as the day of the Lord (see commentary on 1 Thess 5:1–2). As in 1 Thessalonians, Paul links Jesus’s return to the faithful being gathered to him (1 Thess 4:17; 5:10), which he describes here as our assembling (episynagōgē) with him. For Paul, the hope of the Lord gathering his people would have recalled the traditional belief that God would someday reunite the scattered people of God (2 Macc 2:7; Mark 13:27), but he does not elaborate on this point here.

Paul asks them not to be shaken out of your minds suddenly or alarmed by a certain false teaching. The word translated as “suddenly” (tacheōs) could refer to how quickly after his last letter the Thessalonians accepted false teaching (see Gal 1:6) or to their lack of careful deliberation in accepting this new idea. The NABRE renders Paul’s summary of this erroneous belief as the day of the Lord is at hand (enistēmi), which would mean the Lord is about to return. A translation that better reflects the grammar and Paul’s use of the word elsewhere would be “the day of the Lord has come” (see NRSV, NIV).1 In other words, the Thessalonians seem to have thought the †parousia had already occurred! When one considers the global spectacle of Jesus’s return as described in 1 Thess 4:16–17, one might wonder how they could fall for such a silly error. But the idea that the parousia had already come was not as ridiculous as it first sounds. Throughout Paul’s Letters †eschatology is characterized by both future hope and present realization. For Paul, Jesus’s death and resurrection mark God’s decisive victory and the beginning of the end of all things. Those who belong to Christ already taste the life of the world to come because they are united to their risen Lord. In some of Paul’s Letters this current sharing in Jesus’s victory is very strongly emphasized, while always affirming the future day of the Lord (e.g., Rom 6:1–14). In 1 Thessalonians, Paul says that the Thessalonians must live even now as “children of the day” (5:2–5).2 Similar affirmations that the resurrection is in some sense already present are well attested in early Christianity. John’s Gospel says that judgment and new life have already come (John 3:18; see 1 John 3:14), and in Luke, Jesus says, “The coming of the kingdom of God cannot be observed, and no one will announce, ‘Look, here it is,’ or, ‘There it is.’ For behold, the kingdom of God is among you” (Luke 17:20–21). Some pushed this idea even further and denied that there was any future coming. In the Gospel of Thomas (second century) the disciples ask, “When will the repose of the dead take place? And when will the new world come?” Jesus replies, “What you are looking for has come, but for your part you do not know it” (51).3 Second Timothy 2:18 warns against certain men who “deviated from the truth” by claiming that “[the] resurrection has already taken place.”4 It is not hard to imagine how a congregation still new to Paul’s theology could become confused about the timing of the parousia, even to the point of thinking that it had already occurred.5

Why is Paul so concerned that they might accept this teaching? In addition to the fact that he regarded it as false, there are some hints that he worried that the Thessalonians would despair if they lost hope in the coming day of the Lord. As John Chrysostom puts it, “The faithful, having lost hope for anything great or splendid, might give up because of their troubles.”6 According to 2 Thess 1:3–10, the Thessalonian converts were experiencing significant afflictions because of their faith. If they came to believe that there was nothing more to hope for, no “justice” (see commentary on 2 Thess 1:6–7), then they would have had good reason to be “alarmed.” To quote Chrysostom once more: those who teach that the day of the Lord has already come “might even catch Christ in a lie, and, having shown that there is to be no retribution, nor court of justice, nor punishment and vengeance for evildoers, they might make evildoers more brazen and their victims more dejected.”7

Paul doesn’t seem to be certain about who has been spreading the idea that the day of the Lord is already present, but he has suspicions. He warns them against becoming rattled by accepting this idea, whether delivered by a “spirit,” or by an oral statement, or by a letter allegedly from us. The “spirit” here probably refers to a spirit of prophecy. Early Christian prophets were sometimes said to speak by means of spirits (1 John 4:1). Whatever is meant by the NABRE’s quotation marks around the word “spirit”—they do not correspond to anything in the Greek—Paul did not doubt the reality of divinely aided prophecy in the Church (1 Cor 14). He encourages such activity, but he is anxious that it be done appropriately and subject to the discernment of the whole community (1 Cor 14:29). In 1 Thessalonians he says, “Do not quench the Spirit. Do not despise prophetic utterances,” but also, “Test everything; retain what is good” (5:19–21). Someone might claim to have a prophetic word, but it is necessary to test such messages to see if they are genuine. As 1 John puts it, “Do not trust every spirit but test the spirits to see whether they belong to God, because many false prophets have gone out into the world” (4:1). Paul also warns against being deceived by an “oral statement” (literally, a “word”), which refers to Christian teaching or preaching. Finally, Paul warns them against receiving this idea from a letter. Some take this to mean that Paul is aware of forgeries circulating in his name, but the vagueness of Paul’s warnings in verse 2 suggest that he is concerned about the possibility—perhaps he has even heard a rumor about letters written in his name—but not that he knows about a particular forgery.8

Events Presaging the End (2:3–12)

3Let no one deceive you in any way. For unless the apostasy comes first and the lawless one is revealed, the one doomed to perdition, 4who opposes and exalts himself above every so-called god and object of worship, so as to seat himself in the temple of God, claiming that he is a god— 5do you not recall that while I was still with you I told you these things? 6And now you know what is restraining, that he may be revealed in his time. 7For the mystery of lawlessness is already at work. But the one who restrains is to do so only for the present, until he is removed from the scene. 8And then the lawless one will be revealed, whom the Lord [Jesus] will kill with the breath of his mouth and render powerless by the manifestation of his coming, 9the one whose coming springs from the power of Satan in every mighty deed and in signs and wonders that lie, 10and in every wicked deceit for those who are perishing because they have not accepted the love of truth so that they may be saved. 11Therefore, God is sending them a deceiving power so that they may believe the lie, 12that all who have not believed the truth but have approved wrongdoing may be condemned.

OT: 1 Macc 1:41–61; Dan 8:9–11

NT: Mark 13:14–23; 1 John 2:18–23

Catechism: the Church’s ultimate trial, 675–77

Paul explains how the Thessalonians can be certain that the day of the Lord has not yet come: certain other events must take place first. Paul says that he already taught these things while in Thessalonica (2:5), and indeed he does not attempt to explain them clearly or systematically here. The sequence of events is out of order, and the bewildering names and events come thick and fast; the lawless one, the restrainer, the mystery of lawlessness, and the rebellion. Here are the events described in this section rearranged in chronological order. Those who find the verse-by-verse commentary disorienting may want to turn back to page 163 for clarification.

- At present, someone or something is holding back an enemy of God called “the lawless one,” preventing him from doing evil. Though the lawless one is currently being restrained, the “mystery of lawlessness” is already at work in the world, and eventually the restraining power will be removed.

- After the restraining power is removed, “the apostasy” will take place and the lawless one will be revealed. The lawless one will pretend to be God, taking his seat in the temple, and, aided by the power of Satan, he will do mighty deeds that deceive many people. God allows this deception to take place as a form of judgment for those who do not love the truth.

- Finally, Jesus will return and destroy the lawless one.

The words Let no one deceive you in any way might indicate that Paul isn’t completely certain about the source of the error, but they also warn against any possible future confusion. Two events must occur before Jesus’s return: the apostasy and the revelation of the lawless one. The Greek word apostasia refers to rebellion against authority, whether human or divine. The use of the article (the apostasy) and the fact that Paul has already instructed them about this (v. 5) suggest that he is describing an event they are already expecting, an event not fully described here. Many ancient Jewish and Christian texts describe a penultimate period in history when people will rebel against God (e.g., 4 Ezra 5.1–13). In the Gospels, Jesus warns that prior to his return lawlessness will increase, with false prophets and messiahs appearing and deceiving many (e.g., Matt 24:3–13). We find similar warnings elsewhere in the Pauline Letters: 1 Timothy warns that “the Spirit explicitly says that in the last times some will turn away from the faith by paying attention to deceitful spirits and demonic instructions” (4:1), and 2 Timothy says that “there will be terrifying times in the last days” because of an increase in rebellion against God (3:1–5).9 Paul seems to have something similar in mind here. Prior to Jesus’s return he expects a widespread rebellion against God, including the defection of many to the lawless one because of the marvels he works (2 Thess 2:9–12).

The other event that will occur before the Lord’s return is the revelation of the lawless one. It is not clear whether Paul expects the apostasy first and then this event, or if he expects them to happen together. The fact that this figure is to deceive many suggests that Paul sees these events happening at the same time prior to Jesus’s return. For the sake of clarity I will combine everything that Paul says about this figure in verses 3–4 and 9. This figure is called “the lawless one” and the one doomed to perdition. A more wooden translation would be “the man of lawlessness [anomia], the son of perdition [apōleia],” titles that echo biblical descriptions of evil. In Greek Isaiah, Isaiah excoriates the wickedness of the people, calling them “children of perdition [apōleia], lawless [anomos] offspring” (57:4). Daniel prophesies that in the last days many will be “lawless” (anomos) (12:10). The lawless one will be the culmination of human wickedness and opposition to God, a uniquely wicked person who leads others to wickedness (2 Thess 2:9). The title “son of perdition” indicates that he is destined to be destroyed, and perhaps also that he will bring about the destruction of others.10

The manner of the lawless one’s appearance suggests that he appears as an imitation or parody of Jesus, a sort of “antichrist,” though Paul never uses that word.11 Three times Paul describes this figure being revealed (apokalyptō [2:3, 6, 8]), just as he spoke of the revelation (apokalypsis) of Jesus in 1:7. It would be equally accurate to describe the lawless one as “anti-God” because he opposes and exalts himself above every so-called god and object of worship (compare Dan 11:36–38). This figure exalts himself above all the gods of the nations and their shrines. Not content to stop there, he desires to take the place of the one true God, so he takes his seat in the temple of God, presenting himself as God.12 Many of the “low points” in Scripture describe attempts to usurp God, beginning with our first parents’ attempt to “be like God” (Gen 3:5 NRSV). The prophet Isaiah denounces the king of Babylon for saying, “I will ascend above the tops of the clouds; / I will be like the Most High!” (14:14). The prophet taunts him for his punishment at God’s hands: “How you have fallen from the heavens, / O Morning Star, son of the dawn! / How you have been cut down to the earth, / you who conquered nations!” (14:12). Later Christians read this passage as a description of the fall of Satan and made the Latin translation of “morning star” (lucifer) into one of his names (see also Ezek 28:2–19). The Gospels portray the devil tempting Jesus to worship him (Matt 4:8–10; Luke 4:6–8), and the book of Acts portrays Herod being struck down by God for receiving divine honors (12:20–23). For worshipers of the one true God, any attempt to take God’s place is the height of evil.

More directly relevant to this passage, there was a series of disasters in Jewish history involving rulers who interrupted or desecrated the temple in some way. In 167 BC the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes, whose name suggested that he was a manifestation of the divine, sought to interrupt Jewish worship and caused a pagan altar to be erected on the altar of burnt offering (1 Macc 1:41–61). In 63 BC the Roman general Pompey entered the holy of holies, though he did not take anything or attempt to set up false worship.13 Perhaps the threat to Jewish worship that most closely resembles the lawless one came from the Roman emperor Caligula. Claiming to be divine, he sought to have his own image placed in the temple in Jerusalem in AD 40, not that long before 2 Thessalonians was written.14 Inasmuch as images of deities represented their presence, this would have been tantamount to “seating himself in the temple of God, claiming he is God.”

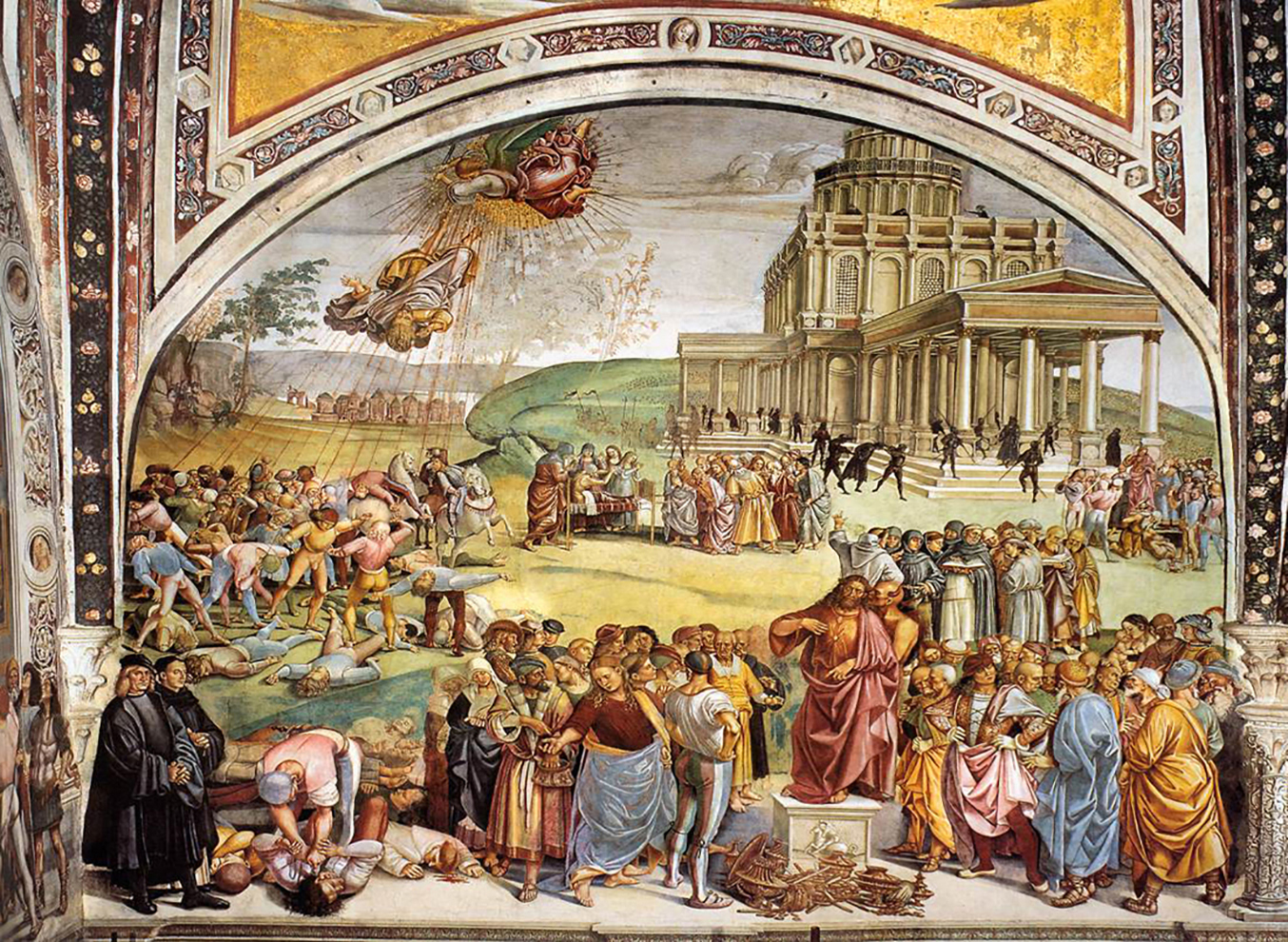

Figure 10. Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist by Luca Signorelli. [Public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

These events as well as later ones, such as the destruction of the temple in AD 70, left a deep imprint on the Jewish and Christian imagination, often forming the template for consummate evil.15 Speaking of Antiochus Epiphanes, the book of Daniel describes a king desecrating the temple (8:11; 9:27; 12:11), “exalting himself and making himself greater than any god; he shall utter dreadful blasphemies against the God of gods” (11:36). The noncanonical Psalms of Solomon describes a certain Gentile ruler as a “lawless one” (anomos) who entered Jerusalem and perverted the people.16 The Gospels take up the prophecy from Daniel, warning of the day when “the desolating abomination spoken of through Daniel” would be seen standing “in the holy place” (Matt 24:15; see Mark 13:14). As a reader of Daniel and a recipient of oral traditions about Jesus, Paul would have had good reason to expect a final, definitive version of these attempts to usurp God. The recent attempt of Caligula to be worshiped in the Jerusalem temple would have been a terrifying reminder of these prophecies.

“The temple of God,” where the lawless one is to enthrone himself, could refer to the temple in Jerusalem, which was still standing during Paul’s life, though since antiquity some have suggested that it refers not to a particular building but to the Church, which Paul refers to as God’s temple (1 Cor 6:19).17 The identification of the temple with the Church eventually led early Protestants to identify the pope as the antichrist, one who enthrones himself in the Church as divine. Most modern commentators, however, conclude that this passage refers to the Jerusalem temple.18 The historical analogues listed above all concern the Jerusalem temple, as do the parallel prophecies in Daniel and the Gospels (see Matt 24:15; Mark 13:14), and the description of this figure sitting down lends itself more naturally to the physical temple in Jerusalem. Moreover, the threat to worship in Jerusalem from Caligula was a very recent memory for Paul.

This description of the lawless one opposing God in the last days by entering “the temple of God” raises a number of questions. Did Paul still think of the structure in Jerusalem as God’s place of residence, even after coming to believe that those in Christ are the temple of God? Readers of Paul after the temple was destroyed faced another question: How could the lawless one fulfill Paul’s end-time scenario if there was no temple left to desecrate? While interesting to ponder, these questions may attach too much literal, predictive weight to Paul’s description. The image of a supremely wicked person opposing God in this way is the traditional image, and it need not possess strict predictive accuracy (see Reflection and Application on 2 Thess 2:3–12).

Just when we would expect Paul to finish his sentence by describing the return of the Lord (“For the apostasy comes first . . . then the Lord will return”), he interrupts himself to chide the Thessalonians for so quickly forgetting what he had taught them: do you not recall that while I was still with you I told you these things? This is a rhetorical question: the Greek grammar assumes a positive answer. He knows that they must remember his previous instruction on this matter. He is therefore frustrated that they have been rattled by the claim that the day of the Lord is already present. The tense of the verb translated as “I told you” (legō) suggests that he repeatedly spoke on this matter when he was in Thessalonica. This fact may also help to explain the somewhat disjointed and elliptical nature of this passage. Paul is reminding them of the implications of things they have already been taught. He is not sketching this †eschatological scenario for the first time.

In the present time, something—or someone—is keeping the revelation of the lawless one at bay.19 The Thessalonians know what it is because Paul has already told them. This leaves it to us to try to work out what he means. Paul describes this restraining activity using both a neuter participle, to katechon (what is restraining), and then a masculine participle, ho katechōn (the one who restrains). This thing or person (or both) has the task of restraining the lawless one until it/he is removed from the scene, and then the lawless one will be revealed. The idea that †eschatological scenarios play out according to a mysterious preordained schedule is well attested in the New Testament (e.g., Mark 13:32; Titus 1:3; 1 Tim 2:6). The million-dollar question is the identity of the restraining force. Tantalizingly vague biblical passages tend to encourage speculation, and this one is no exception. Modern commentators can hardly hope to improve on Augustine’s approach to this passage:

Since the Thessalonians know the reason for Antichrist’s delay in coming, St. Paul had no need to mention it. But, of course, we do not know what they knew; and, much as we would like, and hard as we strive, to catch his meaning, we are unable to do so. The trouble is that the subsequent words only make the meaning more obscure: “For the mystery of iniquity is already at work; provided only that he who is at present restraining it, does still restrain until he is gotten out of the way. And then the wicked one will be revealed.” What is to be made of those words? For myself, I confess, I have no idea what is meant. The best I can do is to mention the interpretations that have come to my attention.20

Augustine wrote this sixteen hundred years ago, and today we are no closer to a definitive identification of the restraining power. All the commentator can do is, like Augustine, “mention the interpretations that have come to my attention.” Here are four of the best interpretations of the restrainer, in ascending order of plausibility.21

- The Roman Empire and the Roman emperor are “what is restraining” and “the one who restrains,” respectively.22 This view assumes that Paul had a positive view of the empire and its authority as a divinely instituted means of restraining evil. Though this view had some patristic support and Paul does tell the Roman Christians to respect the governing authorities (Rom 13:1–7), it would be odd, to say the least, just a few years after an emperor attempted to install an idol of himself in the temple, to identify the Roman emperor as the one who holds such behavior in check. Similar passages in early Jewish and Christian literature tend to cast Rome as a tool of evil (e.g., Rev 13).

- The preaching of the gospel and Paul prevent the coming of the lawless one. Citing Matt 24:14 (“This gospel of the kingdom will be preached throughout the world as a witness to all nations, and then the end will come”), some since antiquity have argued that the gospel must be preached to all nations before this event can occur. This suggestion is on thin ice in taking a line from the Gospels and using it to solve an obscure statement from Paul without any support in Paul’s Letters. Also, at this point in his life Paul probably believed that he would live to see the Lord’s return (see commentary on 1 Thess 4:17) and would therefore not expect to be “removed from the scene.”

- Citing Augustine’s agnosticism with approval, Eugene Boring argues that “the restrainer” refers to nothing in particular: “The author of 2 Thessalonians himself probably did not have in mind a specific power, principle, or person that was presently restraining the advent of the Lawless One. He likely intended his depiction to be provocatively obscure.”23 In support of this view is the fact that after two millennia of trying we still don’t know what Paul meant. Boring’s suggestion is much more persuasive if one takes the view that Paul is not the author and that the reference to teaching the Thessalonians about this matter (2:5) is fiction for the sake of verisimilitude. If Paul is the author, however, he probably taught the Thessalonians about the restraining power and expected them to remember what it was.

- Others argue that the restraining force is probably supernatural and that there is only one figure that fits: an angel, probably the archangel Michael. God could not be “removed from the scene,” and the devil would not be expected to restrain the power of evil. Angels, however, are often assigned important tasks in eschatological scenarios, including opposing Satan and defending God’s people. The archangel Michael is mentioned more than others (see commentary on 1 Thess 4:16). In the book of Daniel, Michael opposes evil forces, keeping them from amassing too much power (10:13, 21; 12:1), and in the †Septuagint version of Dan 12:1, Michael is said to “pass by” or “disappear” just before the final tribulation: “At that hour, Michael, the great angel who stands over the sons of your people, will disappear [parerchomai]” (my translation).24 In 2 Thess 2:6–7, the neuter participle (“what is restraining”) would refer to Michael’s restraining activity, and the masculine participle (“the one who restrains”) to Michael himself. I suggest that this is the best proposal available, but, since we were not there when Paul instructed the Thessalonians face-to-face, we cannot know for certain.

Though the final onslaught of evil is currently held at bay, even now the mystery of lawlessness is already at work. The Latin translation of “mystery of lawlessness,” mysterium iniquitatis, has come to refer to the mystery of the existence of evil in God’s good creation.25 The original meaning of the phrase is related but has important differences. In this passage, lawlessness is not said to be a mystery in the sense of a truth beyond human comprehension. Instead, lawlessness is currently a mystery in the sense that it is currently hidden but will be revealed. For Paul, “mystery” typically signifies a reality that has been revealed to the faithful by the Spirit, but not to the rest of humanity.26 In this passage, this means that with the eyes of faith, the Church recognizes its current sufferings as “labor pains” (Mark 13:8) of the final tribulation. The Thessalonians know—or they ought to know—that the evil they currently experience is not a sign that the end has come but rather a sign that forces opposed to God are moving in the world.

And then—that is, after the present period during which the lawless one is held back—the lawless one will be revealed (apokalytpō), only to be destroyed by Jesus. This verse compresses events, failing to mention for the moment the period during which the lawless one masquerades as God and deceives many. In verse 9, which is part of the same sentence in Greek, Paul goes on to describe the lawless one’s activity. But here his appearance is described in terms of his inevitable doom: he appears only to be destroyed. This is one reason why he is the “son of perdition” (see 2:3): the victory has already been won. The †eschatological events will play out as preordained, but the powers of evil will fall to divine omnipotence.

Jesus’s appearance is described as the manifestation (epiphaneia) of his coming (parousia).27 The word “epiphany” is best known today from the Feast of the Epiphany, which celebrates the manifestation of Jesus to the world, including the adoration of the magi (Matt 2:9–11), his baptism (Matt 3:13–17 and parallels), and his first sign at the wedding in Cana (John 2:1–11). In the ancient world, epiphaneia often described the conspicuous and powerful appearance of God or gods.28 It is language that would have already been very familiar to recent Gentile converts. For instance, Paul’s younger contemporary Plutarch speaks of the goddess Rhea saving a man by appearing to him in a dream, which is described as the “epiphany of the goddess.”29 Stronger than parousia, epiphaneia was often associated with the display of extraordinary power. The addition of this word stresses the visibility of the event.30 Jesus will be made visible to the world, unmasking the lie of the lawless one. By stressing the splendid conspicuousness of Jesus’s coming, Paul soothes the Thessalonians’ worry that the event has already occurred.

Jesus will rout the lawless one effortlessly, with the breath of his mouth, not because of the weakness of evil, but because of Jesus’s incomparable might (see Rev 19:11–16). This description echoes Isa 11’s prophecy of a coming king from the line of Jesse, King David’s father:

But a shoot shall sprout from the stump of Jesse,

and from his roots a bud shall blossom.

The spirit of the LORD shall rest upon him:

a spirit of wisdom and of understanding,

A spirit of counsel and of strength,

a spirit of knowledge and of fear of the LORD,

and his delight shall be the fear of the LORD.

Not by appearance shall he judge,

nor by hearsay shall he decide,

But he shall judge the poor with justice,

and decide fairly for the land’s afflicted.

He shall strike the ruthless with the rod of his mouth,

and with the breath of his lips he shall slay the wicked. (11:1–4 [italics added])

Though the Messiah had already come, Paul still searched the Scripture to understand his future coming, finding in this passage a description of Jesus’s future, public triumph.

After rushing to describe the destruction of the lawless one, Paul backs up to say more about the deceit that will precede ultimate victory. At his appearance or coming (parousia), the lawless one wields diabolical power. More precisely, Satan works in him to enable him to do mighty deeds, signs, and wonders. Paul was proud of his own mighty deeds, signs, and wonders (Rom 15:19; 2 Cor 12:12—the same three Greek words) because he saw them as markers of apostolic ministry, and of course Jesus’s ministry was distinguished by the performance of miracles. Yet the New Testament also describes miracles as part of the deceptive strategy of end-time impostors. Jesus warns that in the last days false christs and false prophets will perform deceptive wonders (Mark 13:22; Matt 24:24; see also Rev. 13:11–13). The purpose of the lawless one’s wonders is to lie and seduce people to their ruin. This does not mean that the signs will be mere parlor tricks—those do not require diabolical assistance. They will target those who are perishing (apollymi), drawing them to the son of perdition (apōleia). These people are vulnerable because they have not accepted the love of truth. The phrase “have not accepted” or “have not received” implies that “the love of truth” was offered but turned down. By rejecting the divine offer, those who are perishing condition themselves to accept lies that will destroy them. What was offered was not merely “the truth” in the sense of a few facts or a bit of information but “the love of truth”—that is, a commitment to the truth that orders one’s life and also shields one against deleterious lies.

In response to people’s love of falsehood, God sends them a deceiving power so that they may believe the lie and so be condemned. The present tense God is sending them could indicate that Paul has shifted focus from the future coming of the lawless one to the present, but it is more likely that he is speaking from the perspective of the event itself. These people accept “the lie”—that is, the deception of the lawless one. There is individual choice—people opt for “the lie” rather than the truth—but God also seems to work to confirm this choice in order to bring these people to judgment. This description does not fit the “free will” versus “determinism” dichotomy often discussed today, but it follows a familiar biblical pattern: people turn away from God, and in return God causes them to suffer the full weight of their decision. For instance, in Rom 1:18–27 Paul says that God hands idolaters over to be enslaved by their sexual passions. In Ps 81 God says, “My people did not listen to my words; / Israel would not submit to me. / So I thrust them away to the hardness of their heart” (vv. 12–13).31

How could God, who is Truth itself (John 14:6), be an agent of deceit?32 Wouldn’t we expect Paul to say that God wants to rescue those who believe the lie (1 Tim 2:4)? Throughout his letters Paul assumes that people are responsible for their actions, that evil is at loose in the world and is capable of seducing people to their ruin, and that God is sovereign over all things. Paul never reflects in a philosophical-theological mode on how to hold these things together. Holding to divine sovereignty does require him to see every diabolical deception as taking place with divine permission. The Catholic tradition maintains that God never forces people to sin but only allows it. As Augustine puts it while commenting on this passage, “‘God will send’ [mittet] means that God will allow [permittet] the devil to do these things.”33

Reflection and Application (2:3–12)

Two main paradigms have dominated interpretation of this passage since antiquity.34 The first, favored by many in the ancient Church, reads this passage as a straightforward prediction of a distinct historical event that will occur in the days shortly before the Lord’s return, including a single historical lawless one or antichrist. Some who follow this approach have sought to identify the lawless one with particular figures in history such as the emperor Nero and various other emperors, or various ancient heretics. Martin Luther and John Calvin accused the pope of being the antichrist.35 Some Catholics returned the favor by alleging that Luther was himself the leader of the great apostasy and therefore a good candidate for being the antichrist.

The second paradigm of interpretation, associated most of all with Augustine, focuses on the existence of antichrists in the present day: everyone who opposes Christ by inciting apostasy and demanding from others the loyalty owed only to God is a lawless one.36 Augustine accepted that there will be trials in the last days, but he avoided attempts to predict what the last days will be like, noting that there is hostility toward God throughout history. These two streams of interpretation reflect two aspects already present in 2 Thessalonians and related biblical passages. Paul speaks of a future lawless one, but he also says the mystery of lawlessness is already at work. First John says the antichrist is coming, but also that many antichrists have already appeared (2:18). After two thousand years of mistaken attempts to identify the antichrist with particular individuals, one could certainly argue that it is safer to stick to the Augustinian approach, regardless of what is revealed in days to come.

Recent magisterial teaching maintains that “before Christ’s second coming the Church must pass through a final trial that will shake the faith of many believers (cf. Lk 18:8; Mt 24:12),” but also stresses the presence of antichrist today: “The Antichrist’s deception already begins to take shape in the world every time the claim is made to realize within history that messianic hope which can only be realized beyond history through the eschatological judgment.”37 In other words, whenever human powers, whether secular or religious, claim to bring to fruition the final ends of humankind, they are setting themselves up in God’s place, in effect “claiming to be God.” One example of this identified by the Catechism is political ideologies that claim to fulfill every need of humankind, offering, as it were, “salvation.”

Hold Fast to the Traditions (2:13–15)

13But we ought to give thanks to God for you always, brothers loved by the Lord, because God chose you as the firstfruits for salvation through sanctification by the Spirit and belief in truth. 14To this end he has [also] called you through our gospel to possess the glory of our Lord Jesus Christ. 15Therefore, brothers, stand firm and hold fast to the traditions that you were taught, either by an oral statement or by a letter of ours.

NT: 1 Thess 2:13–14

Catechism: Tradition, 74–83

As in 1 Thessalonians, Paul repeats his thanksgiving (see 1 Thess 2:13–14; 2 Thess 1:3).38 Throughout this section there is also a conspicuous repetition of language from 1 Thess 2. He addresses them as brothers loved by the Lord, words reminiscent of Moses’s description of the tribe of Benjamin (Deut 33:12), which was Paul’s own tribe. God chose them, which recalls the formal reaffirmation of the relationship between God and Israel in Deuteronomy: “The Lord chose you today that you should be his peculiar people . . . to keep all his commands” (LXX 26:18 [my translation]). It is unlikely that the Thessalonians would have caught the biblical echo, but this suggests once again that Paul considered these former pagans to be recipients of the inheritance of Israel.

In some important ancient manuscripts it says not that God chose them as the firstfruits [aparchēn] but rather that God chose them “from the beginning [ap’ archēs].” The difference in Greek is only one letter. If the latter reading is right, Paul is saying that God had chosen them from the very beginning of creation to belong to him, despite the fact that this surprising reality had only recently been revealed. If the NABRE is correct to accept the former reading, Paul’s point is that the Thessalonians are like a portion of a harvest that is the first or the best and is offered to God. There are reliable ancient manuscripts attesting to both readings. One can never be certain in such cases, but there is good reason to think the NABRE got it right. Though it is no doubt true according to Pauline theology that God chose the Thessalonians from before creation (e.g., Eph 1:4), nowhere else does Paul use the phrase “from the beginning [ap’ archēs].” He does, however, apply the label “firstfruits” metaphorically on a number of occasions (Rom 8:23; 11:16; 16:5; 1 Cor 15:20, 23; 16:15).39 His point here would be that they are but the beginning of a larger harvest of converts who will be holy, devoted to God. Though they are currently a beleaguered minority, Paul hints that there will be (or are already) more who follow in their path. Paul draws here, as elsewhere (Rom 11), on the Old Testament teaching on firstfruits, but it was also common in pagan antiquity to set aside firstfruits to the gods, so Paul’s encouragement would have been understandable regardless of their knowledge of the Scriptures.40

Paul says they are the firstfruits for salvation (see commentary on “salvation” in 1 Thess 5:9) and mentions two means by which God set them aside for this end: their salvation is through sanctification by the Spirit and belief in truth. God’s sanctifying Spirit has been given to them (see commentary on 1 Thess 4:3–8) to make them holy so they will be found worthy when the Lord returns. They in turn offer their “belief” or “trust” in the truth, in contrast to those mentioned in 2:9–12, who prefer lies. The main idea of the second half of verse 13 is restated in a slightly different way in verse 14: God called you through our gospel. “Through our gospel” means here “through Paul’s preaching,” as Thomas Aquinas paraphrases.41 The call comes from God (1:11; see also 1 Thess 2:12; 4:7; 5:24) through the instrument of Paul’s missionary activity. As Paul puts it in 2 Corinthians, “We are ambassadors for Christ, as if God were appealing through us” (5:20).

In the Thessalonian correspondence the language of divine calling is always linked to sanctification—it is a call to become like God—and this passage contains perhaps the most arresting articulation of this idea (see also 1 Thess 2:12; 4:7; 5:23–24; 2 Thess 1:11). The purpose of the call is for them to possess the glory of our Lord Jesus Christ.42 What does the “glory” of Christ refer to here, and how could the Thessalonians come to possess it? In the Old Testament the glory (Greek doxa) of God is God’s visible radiance, the splendor that surrounds him in the heavenly throne room (Isa 6:1; Ezek 1:28) and that will one day be revealed to all people (Isa 40:5), though the earth is already full of divine glory (Isa 6:3; Ps 8) in the sense that it attests to the greatness of the Creator. In 2 Thess 1:9 Paul describes the fate of the damned as being estranged from the “glory” of the Lord, cast away from his brilliance (Rom 3:23). This verse adds to this idea, claiming that the saved come to possess Christ’s glory for themselves, which would mean that they participate or share in that glory. This could mean sharing in the honor of his rule over all things, but the link to sanctification suggests that it means what later Church Fathers would call “theosis” or divinization, being transformed to become like God. Theosis is already implied by sanctification, and Paul’s later letters often link salvation to participation in divine glory (Rom 2:7; 2 Cor 3:18; Phil 3:21).43

Sometimes verse 15 is quoted as a freestanding statement about the importance of tradition, but it is important at least in the first instance to read it for what it was originally: a final instruction designed to protect the Thessalonians from wandering into error again. After reassuring the Thessalonians that the day of the Lord has not yet come (2:1–12) and that they are on the path to salvation (2:13–14), Paul attempts to prevent this sort of confusion from taking root again: stand firm and hold fast to the traditions that you were taught. The word translated “tradition” (paradosis) can have the sense of handing something down, such as the traditions handed down (paradidōmi) about Jesus’s death (1 Cor 11:23–26) and resurrection (1 Cor 15:1–11) in the early years of Christianity. Paul saw the traditions he handed down as having divine origins because they came ultimately from the Lord (see commentary on 1 Thess 2:13). Standing firm and holding fast suggests a contrast to the Thessalonians’ current “shaking” with fear (2 Thess 2:2). By holding lightly to what they had been taught, they made themselves vulnerable to the idea that the day of the Lord had already come, and in 3:6–13 we discover another tradition to which the Thessalonians need to cling: working to support oneself.

Paul specifies two forms of tradition that they should hold to, either by an oral statement or by a letter of ours. The phrase “oral statement” translates logos (“word”), referring to Paul’s preaching and teaching. The Thessalonians are to hold fast to what Paul taught regardless of whether they received it when he was with them or by letter. Paul’s oral teaching and his letters are to be the authoritative guards against possible sources of confusion mentioned in 2:2: spirits, oral teaching from other sources, and letters supposedly from Paul. One of the three sources of information mentioned in verse 2 is conspicuously absent here: the utterances of “spirits.” Why doesn’t Paul ask them to hold fast to authentic prophetic utterances as well? In 1 Thess 5:20–21 he instructed them not to despise prophecies but to test all things and hold on to the good. Since that time the Thessalonians do not seem to have done well at weighing ideas and holding to the good. It may be that he preferred to direct the “shaken” converts to the truths that would help them discern true prophecies from false in the first place.

Reflection and Application (2:13–15)

Scripture and Tradition. Catholics have sometimes appealed to 2 Thess 2:15 to defend the view that there are two sources of revelation: Scripture (written tradition) and oral tradition.44 Since the Second Vatican Council, Catholic teaching has stated strongly and repeatedly that there is only one source of revelation—God—and that Scripture and Tradition are the two modes of transmitting divine revelation.45 Why does this matter? A 1962 lecture given by a young Joseph Ratzinger on the eve of the Council helps to explain what is at stake.46 For one thing, speaking of Tradition as a discrete “source” of revelation encourages the erroneous idea that all Church teaching was already formulated in the first century and was then passed down orally to be defined publicly at some point in the future. Professor Ratzinger rightly objects, “History can name practically no affirmation that on the one hand is not in Scripture but on the other hand can be traced back even with some historical likelihood to the Apostles.”47 In other words, it is impossible for historians to defend the view that everything the Church now teaches was known by Tradition in the apostolic period. It is clear that doctrine has developed in the Church through the centuries “through the contemplation and study made by believers, who treasure these things in their hearts” (Dei Verbum 8). Moreover, treating Scripture and Tradition as the “sources” of revelation can lead to a serious theological error. This approach narrows the concept of revelation to a finite list of truths, whereas the Fathers and medieval theologians taught that revelation is divine self-gift that always exceeds our knowing.48 As the Council’s declaration on divine revelation, Dei Verbum, would go on to put it, there is one “divine wellspring” of revelation from which flows both Scripture and Tradition.49 This is why sacred Tradition is rightly said to be “living”: it reflects the people of God’s ongoing search for the face of the Lord.

Tradition and Traditions. Broadly speaking, the New Testament describes two kinds of tradition (Greek paradosis): traditions that distract from the truth, and holy traditions that guide one into it.

Stand firm and hold fast to the traditions [plural of paradosis] that you were taught. (2 Thess 2:15)

We instruct you . . . to shun any brother who conducts himself in a disorderly way and not according to the tradition [paradosis] they received from us. (2 Thess 3:6)

I praise you because you remember me in everything and hold fast to the traditions [plural of paradosis], just as I handed them on to you. (1 Cor 11:2)

You have nullified the word of God for the sake of your tradition [paradosis]. (Matt 15:6)

In her book on the importance of tradition in Scripture, Edith Humphrey points out that English Bibles since the King James Version tend to use the word “tradition” only in negative contexts.50 When Jesus condemns paradosis that nullifies the word of God, the KJV and many English Bibles since are happy to use the translation “tradition.” But when the same Greek word is used in a positive context, it is translated as “instruction” or “teaching” or some other word. The New International Version largely follows the KJV in casting a sinister light on “tradition,” as does the New Living Translation.51 The tendency of English Bibles to make “tradition” something to be avoided arises from and reinforces a Reformation suspicion of tradition, and it also obscures the fact that these passages speak not just of “teaching” but of something handed down and treasured. It would be a mistake, however, to assume that traditions are always a good thing. As Thomas Aquinas notes in his commentary on 2 Thessalonians, traditions are not to be kept if they are contrary to the teaching of the faith.52 Indeed, Paul himself tells the churches in Galatia not to listen to anyone who teaches something contrary to the gospel (Gal 1:8).

Prayer for Strength (2:16–17)

16May our Lord Jesus Christ himself and God our Father, who has loved us and given us everlasting encouragement and good hope through his grace, 17encourage your hearts and strengthen them in every good deed and word.

NT: 1 Thess 3:11–13

Lectionary: 2 Thess 2:1–3a, 14–17; Memorial of Saint Augustine

In a prayer very similar to 1 Thess 3:11–13, Paul asks our Lord Jesus Christ and God our Father to console the Thessalonians and empower them to do good deeds.

The prayer states that God has already loved us and given us everlasting encouragement and good hope through his grace. The encouragement or consolation is “everlasting” in the sense that it is has already been given but will never end. The “good hope” refers to the hope of their final salvation. Though this phrase does not appear elsewhere in Scripture, it was used occasionally by Jews and pagans to refer to the hope of life after death.53 The words “through his grace” indicate again that this is a divine gift. Paul prays that God would encourage your hearts and strengthen them in every good deed and word. In modern English, “heart” refers to the source of a person’s emotions, but “heart” here and in the Bible generally refers to the center of a person’s being, the source of thinking and willing as well as feeling. God will strengthen them to speak the word, which could refer to their own evangelizing efforts. The encouragement and strength he prays for contrasts with their current state of confusion, and the mention of good deeds foreshadows the coming rebuke of those who have been idle.

1. See the discussion in Jeffrey A. D. Weima, 1–2 Thessalonians, BECNT (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2014), 501–2.

2. Abraham J. Malherbe, The Letters to the Thessalonians: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, AB 32B (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 429.

3. Bart D. Ehrman and Zlatko Pleše, The Apocryphal Gospels: Texts and Translations (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 323.

4. See also Acts of Paul and Thecla 14; Irenaeus, Against Heresies 1.23.5.

5. This passage reads very differently on the assumption of non-Pauline authorship. See, e.g., M. Eugene Boring, I & II Thessalonians, NTL (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2015), 259–81.

6. Homiliae in epistulam ii ad Thessalonicenses (PG 62:469 [my translation]).

7. Homiliae (PG 62:469 [my translation]). See also 2 Pet 3:3–4.

8. Weima, 1–2 Thessalonians, 504–6.

9. See also 2 Pet 3:3–4; Jude 1:17–19.

10. This same phrase refers to Judas in John 17:12.

11. In Scripture only the Johannine Epistles use the word “antichrist” (1 John 2:18, 22; 4:3; 2 John 1:7), where it refers to a coming figure (1 John 2:18) as well as to all who deny that Jesus is the Christ (1 John 2:22) or that he came in the flesh (2 John 1:7).

12. The NABRE’s “claiming that he is a god” is grammatically possible but contextually unlikely. From a Jewish perspective, pretending to be the One who resides in the temple is a claim to be God.

13. Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 14.4; Jewish War 1.7.6; Tacitus, Histories 5.9.

14. Josephus, Jewish War 2.184–85; Tacitus, Histories 5.9; Philo, The Embassy to Gaius. Caligula’s assassination prevented his wish from being carried out.

15. Naturally, those who read 2 Thessalonians as the product of a later follower of Paul will put more weight on these later events.

16. See chaps. 2, 8, and 17. The figure spoken of is probably Pompey.

17. Béda Rigaux, Saint Paul: Les Épitres aux Thessaloniciens, EBib (Paris: Lecoffre, 1956), 660–61.

18. See the discussion in Weima, 1–2 Thessalonians, 518–23.

19. I take “now” (nun) to modify “what is restraining,” not “you know” as in the NABRE. See Gordon D. Fee, The First and Second Letters to the Thessalonians, NICNT (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009), 286–87.

20. The City of God 20.19, in The City of God, Books XVII–XXII, trans. Gerald G. Walsh and Daniel J. Honan, FC 24 (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1954), 298.

21. For longer discussion including more proposals, see Weima, 1–2 Thessalonians, 567–77.

22. See Tertullian, The Resurrection of the Flesh 24.

23. Boring, I & II Thessalonians, 276.

24. On this point and in support of this reading generally, see Colin Nicholl, “Michael, the Restrainer Removed (2 Thess. 2:6–7),” JTS 51 (2000): 27–53, esp. 42–50. Weima (1–2 Thessalonians, 574) notes that Rev 20:1–3 likewise speaks of an angel temporarily restraining evil (in this case, the devil) that will be unleashed in the final days.

25. See Catechism 385, 675.

26. E.g., 1 Cor 2:7; Col 1:26. See T. J. Lang, Mystery and the Making of a Christian Historical Consciousness: From Paul to the Second Century, BZNW 219 (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2015).

27. See the discussion of parousia in the commentary on 1 Thess 4:15.

28. E.g., 2 Macc 14:15. The Pastoral Epistles use epiphaneia to describe Jesus’s future coming, as well as his past coming. See 1 Tim 6:14; 2 Tim 1:10; 4:1, 8; Titus 2:13.

29. Lives: Themistocles 30.3. Antiochus IV, mentioned above, took the name “Epiphanes” to claim that he was a manifestation of the divine. Second Maccabees describes the Jews praising God because he “always comes to the aid of his heritage by manifesting [epiphaneia] himself” (14:15).

30. Malherbe, Letters to the Thessalonians, 434.

31. See also 1 Kings 22:23; Ezek 14:9; compare 2 Sam 24:1 and 1 Chron 21:1.

32. God as Truth is a Johannine description, but the Pauline Letters assume that truth characterizes God.

33. City of God 20.19 (my translation). The Catechism of the Council of Trent says of biblical texts such as Exod 7:3 and Rom 1:26, 28, in which God is said to hand people over to sin, “These and similar passages, we are not at all to understand as implying any positive act on the part of God, but his permission only” (trans. Theodore Alois Buckley [London: George Routledge, 1852], 574).

34. This reflection is indebted to Kevin L. Hughes, Constructing Antichrist: Paul, Biblical Commentary, and the Development of Doctrine in the Early Middle Ages (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2005). See also Anthony C. Thiselton, 1 & 2 Thessalonians through the Centuries, BBC (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011), 213–17.

35. According to Thiselton (1 & 2 Thessalonians, 217), Joachim of Fiore (1135–1202), a Catholic, had already suggested that a pope would be the lawless one.

36. See especially City of God 20.

37. Catechism 675–76.

38. On the obligation to give thanks (“ought”), see commentary on 2 Thess 1:3. On praying “always,” see commentary on 1 Thess 1:2 and 5:17.

39. For a longer argument, see Fee, First and Second Letters to the Thessalonians, 301–2.

40. E.g., Plutarch, De Pythiae oraculis 16.

41. Super ad Thessalonicenses II reportatio 2.3.58 (my translation).

42. The word translated as “possess” (peripoiēsis) appears in 1 Thess 5:9 (“gain” salvation).

43. See Catechism 456–60, 1996–99.

44. Rigaux, Les Épitres aux Thessaloniciens, 689.

45. See especially Dei Verbum (Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation) 9; Catechism 74–83.

46. Translated into English by Jared Wicks, “Six Texts by Prof. Joseph Ratzinger as peritus before and during Vatican Council II,” Gregorianum 89 (2008): 233–311.

47. Wicks, “Six Texts by Prof. Joseph Ratzinger,” 274.

48. See Henri de Lubac’s explanation of the quotation of 1 John 1:1–4 in the opening of Dei Verbum in his commentary on the latter in La Révélation divine, 3rd ed., Traditions chrétiennes (Paris: Cerf, 1983).

49. See Matthew Levering, Engaging the Doctrine of Revelation: The Mediation of the Gospel through Church and Scripture (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2014).

50. Edith Humphrey, Scripture and Tradition: What the Bible Really Says (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2013), 25–44.

51. To be more precise, the 1984 NIV exacerbates the tendency of the KJV by leaving no positive uses of “tradition.” The 2011 NIV contains one positive use of “tradition” (1 Cor 11:2). The NLT contains one positive use (2 Thess 3:6).

52. Super ad Thessalonicenses II reportatio 2.3.60.

53. See Povl Otzen, “‘Gute Hoffnung’ bei Paulus,” ZNW 49 (1958): 283–85.