Chapter 10 Substance use and dependency

1. Describe the range of substances available, the people who use these substances and possible reasons for their use.

2. Describe substance-related intoxication, tolerance, dependence, withdrawal, craving, abstinence and planned detoxification.

3. Describe the neurophysiology of tolerance and drug dependence.

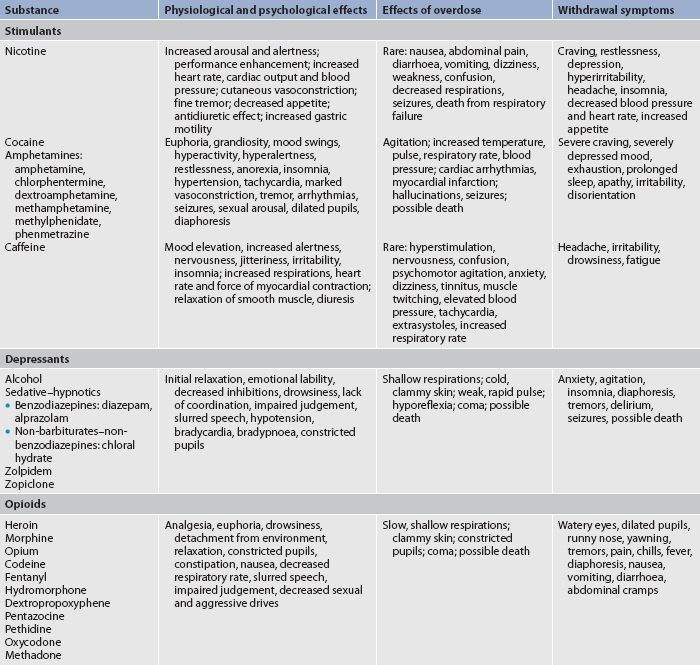

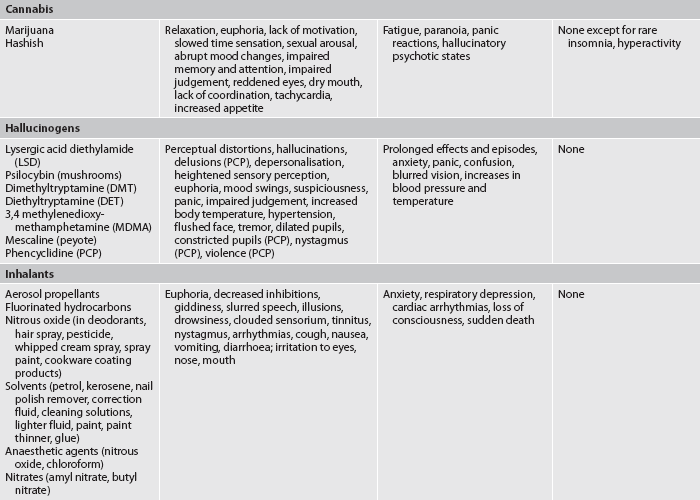

4. Describe the psychostimulant, depressant and hallucinogenic effects of common substances on the central nervous system.

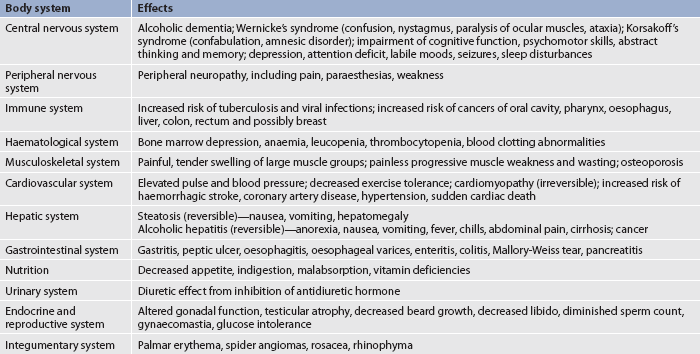

5. Identify the range of health complications linked to or associated with risky and harmful substance use.

6. Describe the nursing management of patients affected by intoxication, overdose or withdrawal from psychostimulants and depressants.

7. Describe the nursing management of the surgical patient with substance use-related health problems.

8. Describe the nursing interventions for smoking cessation.

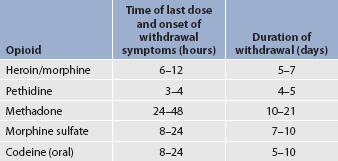

9. Describe the nursing management of pain for the patient who is tolerant of major analgesics—morphine, codeine, heroin and methadone.

10. Describe how motivational interviewing can assist a patient with substance use problems to consider changing their pattern of use, including abstinence.

Legal and illegal drugs are used by a diverse range of people from all walks of life. In Australia and New Zealand, legal drugs include alcohol, tobacco, caffeine and approved pharmaceuticals. Illegal drugs include cannabis (marijuana), psychostimulants (amphetamines, methamphetamines and cocaine), morphine, codeine and heroin.1 There have been recent increases in the use of cocaine among a widening cohort of people. The use of inhalants and hallucinogens is relatively minor compared to that of cannabis and psychostimulants.2 It is important that nurses have an understanding of the needs of people experiencing difficulties with substance use and dependency.

The use of psychoactive substances impacts significantly on the health and wellbeing of Australians and New Zealanders. The results from the 2007 national drug strategy household survey in Australia revealed that use and misuse of licit (legal) and illicit (illegal) drugs is a major health problem with wide social and economic costs. Of the 17.2 million Australians aged 14 years or older surveyed, 16.6% admitted to smoking daily. Males were generally more likely to be daily smokers than females, with the exception of the 14–19 year age group, where females were more likely to be daily smokers (8.7%) than males (6.0%).2 Tobacco smoking is the single most preventable cause of ill health and death. It is a major risk factor for coronary heart disease, stroke, peripheral vascular disease, cancer and a variety of other diseases and conditions. It has been estimated that tobacco is responsible for 7.8% of the total burden on health of Australians, with about 10% of the total burden of disease in males and 6% in females. The tangible costs of tobacco use in Australia are estimated at $12 billion, or about 1.3% of gross domestic product.2

In the Australian population, consumption of alcohol has been relatively unchanged since 1991. In 2007 about 89% of Australians over the age of 13 admitted consuming alcohol at least once in their lifetime, with 3 out of 5 drinking at low-risk levels of short- and long-term harm.2 Excessive alcohol consumption is a major risk factor for morbidity and mortality. It is estimated that harm from alcohol caused 3.8% of the burden of disease for males and 0.7% for females in 2003, ranking it sixth out of 14 major risk factors. In 2004–2005, the total tangible costs attributed to alcohol consumption (which includes lost productivity, healthcare costs, road accident-related costs and crime-related costs) were estimated at $10.8 billion, or about 1.2% of gross domestic product.2

Illicit drug use is a major risk factor for ill health and death. It is associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), hepatitis C virus, low birth weight, malnutrition, infective endocarditis (leading to damage to the heart valves), poisoning, mental illness, suicide, self-inflicted injury and overdose. It has been estimated that 2% of the burden of disease in 2003 was attributable to the use of illicit drugs, ranking it eighth out of 14 major risk factors.2

In New Zealand, the overall pattern of alcohol use is similar to that in Australia. According to the 2006/2007 New Zealand health survey, 85% of New Zealanders aged 16–64 had an alcoholic drink in the previous year, with 61.6% consuming more than the recommended guidelines for a single drinking session at least once during that time. One in six adults aged 15+ have a potentially hazardous drinking pattern.3 In terms of the health impacts, estimates indicate that between 600 and 1000 people die each year from alcohol-related causes.4,5 More than half of alcohol-related deaths are due to injuries, one-quarter are due to cancer and one-quarter to other chronic diseases.6 Between 18% and 35% of injury-based emergency department presentations are estimated to be alcohol-related, with this figure rising to 60–70% during weekends.6,7 Approximately 14% of the population are predicted to meet the criteria for a substance use disorder at some time in their lives.8 In terms of crime and violence, the New Zealand Police estimate that approximately one-third of all police apprehensions involve alcohol, half of serious violent crimes are related to alcohol, more than 300 alcohol-related offences are committed daily, and every day 52 individuals or groups of people are either driven home or detained in police custody because of intoxication.9

Problems associated with psychoactive substance use can seriously affect individuals, families, the healthcare system and society. These problems are interlinked with a range of social, legal and health problems. The problems range from one-off or occasional use to regular and harmful patterns of use. Dependence (also known as addiction; see Table 10-1) has similar characteristics to other compulsive behaviours, such as gambling, eating disorders and excessive exercising. It should be noted that dependence occurs in a minority of people who use these substances.

TABLE 10-1 Terminology of substance use problems

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Abstinence | Avoidance of substance use (or other addictions such as gambling). |

| Addiction | Compulsive, relapsing dependence on a substance or other practice to such a degree that cessation or rapid reduction causes severe emotional, mental and/or physiological withdrawal symptoms, and craving. |

| Addictive behaviour | Behaviour associated with maintaining an addiction. |

| Craving | Subjective need for a substance that is neurologically driven. It is usually experienced following decreased use or abstinence. Cue-induced craving is stimulated in the presence of experiences or situations previously associated with drug taking. |

| Detoxification | Refers to the process of physical withdrawal from the drug upon which the person is dependent. It may or may not involve the administration of medications, and will generally require support. |

| Harmful use | The use of a substance at a level known to cause long-term organ damage and/or psychological harm. |

| Rehabilitation | A process by which the person with a substance use disorder is supported in achieving an optimal state of health, psychological functioning and wellbeing. |

| Relapse | A return to problem use of a substance (or other practice) following a period of abstinence. |

| Substance use | Alcohol, tobacco or other drug that is self-administered. |

| Substance use problem | A pattern of substance use manifested by significant adverse health and/or social consequences related to repeated use of the substance. |

| Substance dependence | A classified syndrome manifested by observable physiological, cognitive and behavioural responses to the prolonged, regular use of a substance that affects the central nervous system and resulting in tolerance and psychological dependence. |

| Substance misuse | Use of a drug for purposes other than those for which it is intended. |

| Tolerance | Decreased effect of a substance that results from repeated use. Increased doses are required to achieve the effect originally produced by lower doses. It is possible to develop cross-tolerance to other substances in the same category. |

| Withdrawal | Syndrome of physiological and psychological responses that occurs with abrupt cessation or reduced intake of a substance upon which an individual is physically tolerant, or when the effect is counteracted by a specific antagonist to the drug used (e.g. naloxone is an antagonist of opioids). |

Substance-related problems, including dependence, also occur with the unsafe use of prescribed drugs. In Australia, the most commonly prescribed pharmaceuticals affecting the central nervous system (CNS) are antidepressants (47%), antipsychotic drugs (29%) and major analgesics (21%).2 The most commonly used over-the-counter pharmaceuticals include aspirin, paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The unsafe use or adverse effects of these pharmaceuticals are responsible for more significant injury, illness and death than all illicit drugs. The widely used over-the-counter drug, paracetamol, caused 5.43% of drug deaths in Australia between 1997 and 2007. This was almost equal to the number of deaths (5.78%) caused by amphetamines, and was half the number of deaths caused by heroin (10.25%) and a third the number of deaths caused by alcohol toxicity (15.09%).10

Individuals who use substances at risky and harmful levels are often in contact with the healthcare system as a result of accidental injury or concurrent illnesses. All nurses, wherever they practise, will at some time come into contact with patients experiencing the harmful effects of their substance use. This is simply due to the prevalence of substance use, the pharmaceutical effects of these substances and the high correlation with a range of serious physical and mental health problems. These patients may be drug dependent or not. In every healthcare setting the nurse has an opportunity and responsibility to identify and assist patients experiencing substance use problems, including those associated with intoxication, regular harmful use or dependence.11,12

Substance use conditions, including dependence, are considered to be specific psychiatric AXIS 1 diagnoses.13 Comprehensive discussions of dependence and related complex problems, such as mental illness, are provided in many psychiatric textbooks. Specialist management of dependence is mostly provided in general hospital-based drug and alcohol units, stand-alone drug treatment services and some mental health clinics. Specialist services can offer a range of therapies, including pharmacotherapy, 12-step abstinence-based programs, specialist counselling, general counselling, narrative therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy, social support and primary healthcare.14 This chapter addresses the nursing role in identifying and assisting people experiencing significant problems with their substance use and who are in the general ambulatory or acute care setting. Eating disorders are discussed in Chapter 39 and health problems related to addictive behaviours are discussed throughout the text.

Overview of addictive behaviours

TERMINOLOGY OF SUBSTANCE USE ISSUES

The standard terminology for the range of substance use problems in Australia and New Zealand reflects the recommended nomenclature of the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the World Health Organization.15,16 In this chapter, addiction is defined as a compulsive, chronic relapsing dependence on a substance whereby cessation is difficult and often accompanied by severe emotional, mental and physiological concerns. Craving to resume the same pattern of use is common. Various dynamics influence whether or not a person becomes dependent and, if they do, how difficult it may be for them to resolve their condition and become abstinent or at least use at a much reduced rate. These dynamics include the actual pharmacology of the drug, the reasons why they are using it, family dynamics, genetics, individual physical and psychological characteristics, and environment.17 Some additional terms used to describe harmful substance use are presented in Table 10-1.

NEUROPHYSIOLOGY OF DEPENDENCE

Dependence is a relapsing, complex disorder that for many people can be treated. Research offers increasing understanding about the various effects of psychoactive drugs on the human brain, and related conditions and behaviours. Certain psychoactive drugs, and possibly certain compulsive behaviours, increase the release of dopamine along the mesolimbic dopamine pathway in the brain. This is known as the pleasure centre of the brain. This pathway was originally designed to communicate to ancient humans, via the release of dopamine, that pursuit of food, consumption of food and sexual behaviour were vital for the survival of the species. Drugs such as opioids, alcohol and psychostimulants hijack this ancient mechanism and communicate to the drug-dependent person that consumption of the drug (rather than food and sex) is a central aim of their existence.

Normally, dopamine is released at a slow rate by neurons in the mesolimbic system, moderating normal affect or mood. Both endogenous and exogenous opiates have been found to increase the firing rate of dopaminergic neurons. Cocaine has been shown to decrease the reuptake of dopamine at the synapse, thereby decreasing its breakdown and increasing the amount of available dopamine. Nicotine, alcohol, cannabis and psychostimulants such as cocaine, methamphetamine and caffeine all increase dopaminergic neuron activity at the synapse. The resulting increase in mesolimbic dopamine levels leads to mood elevation and euphoria. This mood elevation and euphoria can, for some people, provide a strong stimulus to repeat the experience. Psychoactive drugs may also increase the availability of other neurotransmitters, such as serotonin and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), but dopamine’s effect on the pleasure centre of the brain appears to be pivotal to the dependence process.18

Physiological tolerance results from the repeated effects on the brain of daily or almost daily doses of psychoactive drugs such as alcohol, methamphetamines, nicotine or opioids. The regular, repeated use of a psychoactive drug alters the neural circuitry involving dopamine cells and reduces the responsiveness of dopamine receptors. This decreased responsiveness leads to tolerance or the need for a larger dose of the drug to obtain the original CNS effects. It also reduces the sense of pleasure (or reduction in pain) from repeated drug use that previously resulted in feelings such as euphoria. If the person then rapidly reduces their use or stops using the drug, they are very likely to experience what is known as withdrawal. This indicates that they are physically dependent on the drug. To reduce the emerging symptoms of withdrawal and hypersensitivity of the CNS, which has neuro-adapted, the person needs to continue taking the drug as frequently and at sufficient doses as previously.19

Craving to resume drug use is a major neurological symptom of dependence caused by cessation or rapid reduction in use. An important aspect of craving among dependent people is cue-induced craving. This can occur when the person who has stopped using a drug finds themselves in the company of particular people or in certain situations that they have learnt to associate with their drug use. Cue-induced craving may occur after long periods of abstinence and is a common cause of relapse. Current research indicates that cue-induced craving is accompanied by heightened activity in key brain areas involved in mood and memory, and that cue-induced craving creates a compelling urge to resume drug use. Although neurotransmitter activity is involved, it is yet to be fully determined what specific processes in the brain link people’s memories so strongly with their craving to take specific drugs.20

FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO ALCOHOL AND OTHER DRUG DEPENDENCE

It is important that dependence is perceived not only as a physical neurological condition, but also a complex psychological disorder. It is a condition that is often expressed behaviourally, and is always influenced by the location, cultural and social context of people’s lives.

No single factor has been identified that can determine whether a particular individual may experience a drug-related problem. Nor is it fully understood why some people become dependent on alcohol or drugs even though others who use the same drug do not. Some contributing factors include drug availability, family influences, peer influences (see Fig 10-1), environment, psychiatric illnesses, adverse social conditions and cultural influences.17 There is evidence that genetics play a role in nicotine dependence with possibly significant gender differences in risk. However, the presence or absence of the defective gene does not affect women’s rates of smoking.21

The Australian Institute of Health & Welfare reported that, overall, men are more likely than women to use drugs, but that young women under 25 are now matching their male peers for alcohol and other drug use.2 Women who are high alcohol users are susceptible to cirrhosis of the liver and other alcohol-related medical illnesses after a briefer period of drinking, at equivalent levels of risk (about 10 years’ difference), than male peers.15 Women are more likely than men to be prescribed sedatives, antidepressants and tranquillisers, and generally use more over-the-counter analgesics.

Cultural factors influence people’s beliefs, attitudes, choices, behaviours and substance use problems. Their problems may be associated with their living conditions, history of trauma as a child, adverse socioeconomic status, life opportunities, genetics, environment or various adverse experiences.16

Rates of alcohol and drug use differ between non-Indigenous and Indigenous Australians. Per capita, twice as many Indigenous Australians as non-Indigenous Australians smoke tobacco, but fewer Indigenous Australians consume alcohol.2,22 Interestingly, Indigenous drinkers are more likely to give up problem drinking and maintain abstinence than non-Indigenous drinkers.22 Of those Indigenous people who drink, their pattern of drinking is more likely to be at high-risk levels, resulting in many serious health consequences, such as death from accidental injury, serious mental health problems and physical illnesses, all of which are devastating. Although less prevalent than among the non-Indigenous population, cannabis use is significant, being the most used illicit drug. There have been anecdotal and some research reports of rising rates of illicit drug use among Indigenous Australians, particularly cannabis, and unsafe injecting practices resulting in hepatitis B and C.23–25 Petrol sniffing among Indigenous populations has decreased since 2000 but still represents a significant source of harm.26–28

Figures for New Zealand suggest that differences between cultural groups, while present, are perhaps not as marked as in Australia. Tobacco use is higher among Māori and Pacific Islanders than in European and other ethnic groups. Smoking is a particular hazard among young Māori women, who have the highest rates of smoking of all age and ethnic groups.29 Non-Māori are significantly more likely to have consumed alcohol in the past 12 months than Māori. Drinking patterns also vary between groups, with males significantly more likely than females to have consumed large amounts of alcohol at least once a week, and Māori more likely to have consumed large amounts at least once a week compared to non-Māori.30 Rates of abstinence are higher among Pacific Islander peoples than in the rest of the New Zealand population.29

A major concern for all culturally diverse Indigenous communities is that alcohol and other drug services need to be culturally sensitive and able to respect and accommodate the various cultural values and practices of diverse groups.12 Cultural competence and cultural safety in healthcare are discussed in Chapter 2. Internet-based resources relating to targeted New Zealand programs are available on this subject from the Ministry of Health website (see the Resources on pp 206–207).

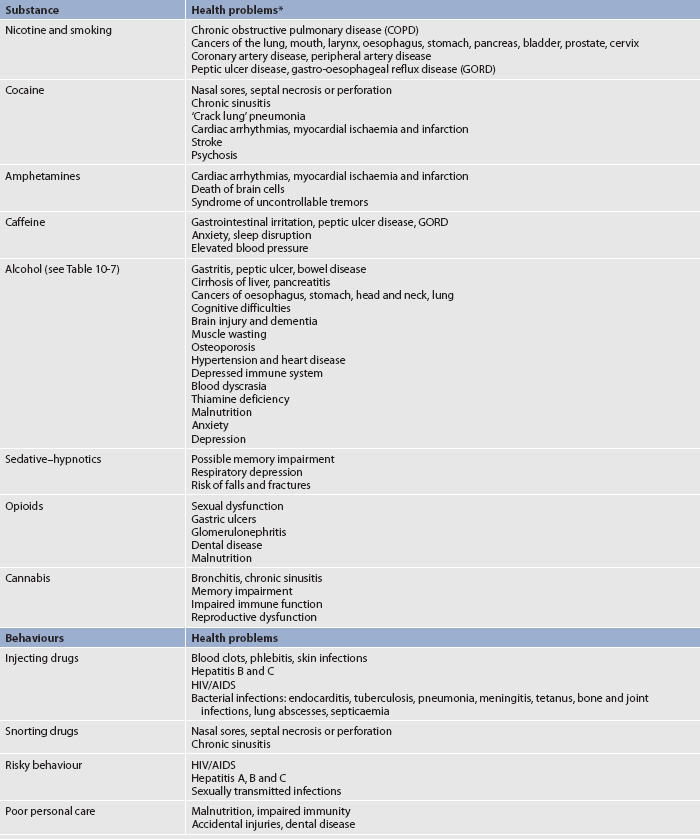

HEALTH COMPLICATIONS OF HARMFUL SUBSTANCE USE

Harmful alcohol and other drug use constitute immediate and longer term disruption to the health and wellbeing of individuals, families and the community. Depending on the pharmacological make-up, action and route of administration, alcohol, tobacco and other drugs (ATODs) adversely affect the brain and body organs. This can result in acute problems from intoxication (e.g. injury, infection, toxicity and overdose), as well as serious longer term damage (e.g. brain damage, respiratory disease, peripheral neuropathy, cancer, blood disorders, liver disease, kidney disease and heart disease).15 Mental health problems can be associated with alcohol and other drug use. The more common disorders are depression and anxiety and, for some, psychosis. Suicide is a known risk, related to the direct effects of drugs, particularly alcohol, due to altered mood, poor impulse control and problem solving. Alcohol and other drugs may also cause disinhibition, resulting in impulsive self-destructive behaviour leading to self-harm and harm of others.31

Unsafe injecting of drugs, whether occasional or regular, places people at serious risk of contracting infections. Injecting with unclean equipment (including used needles, syringes, spoons, tourniquets and swabs) and unclean hands, and using unsafe injecting techniques that damage soft tissue and veins places people at major risk of contracting and transmitting hepatitis B and C, and HIV. There is also a major risk of contracting bacterial infections that may be life threatening (e.g. pericarditis or septicaemia).

Rates of HIV transmission remain very low among injecting drug users in Australia. However, injecting drug users are still a priority population because HIV rates among injecting drug users are sensitive to even small adjustments in the availability of injecting equipment.14 In contrast to HIV rates, hepatitis C prevalence continues to be high. People who inject drugs are the highest priority for hepatitis C prevention efforts. They also comprise a significant proportion of people living with hepatitis C and are a significant priority population in terms of care, treatment and support. Approximately 90% of new and 80% of existing hepatitis C infections are attributable to injecting drug use.32 Indigenous Australians who inject drugs have significantly higher rates of hepatitis C. Their poor access to clean injecting equipment, community attitudes and fear of discrimination can severely hinder hepatitis C prevention and treatment efforts, particularly in rural and remote communities.32 Common health complications from harmful substance use are identified in Table 10-2.

TABLE 10-2 Examples of substance-related health problems

HIV/AIDS, human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

* The health problems related to substance abuse and dependence are discussed in the appropriate chapters throughout the text where addictive behaviours are identified as risk factors for these problems

Source: National Institute on Drug Abuse. Addiction and health. In: NIDA: drugs, brains, and behavior—the science of addiction. NIH pub no. 07-5605. Rockwell, MD: National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. Available at www.nida.nih.gov/scienceofaddiction/health.html, accessed 12 March 2011.

Nicotine

CHARACTERISTICS

One drug dependence that nurses will regularly encounter in their patients is nicotine dependence. Nicotine is the active chemical in tobacco. It is a CNS stimulant, being an alkaloid with a very short half-life, causing rapid escalation to physical tolerance and dependence. It is the most rapidly addictive psychoactive drug.

EFFECTS OF USE

Nicotine is rapidly absorbed when inhaled, entering the bloodstream through the alveoli in the lungs. It is absorbed more slowly through the buccal mucosa when chewed or through the nasal mucosa when sniffed. When absorbed, it produces a wide range of neurological effects on the peripheral and central nervous systems through action at nicotinic receptors. In the brain, the action of nicotine on nicotinic receptors causes general CNS stimulation, with increased alertness and arousal. These effects result in stimulation of the cardiovascular system and increased myocardial oxygen consumption. Responses include increased blood pressure, heart rate, cardiac output, coronary blood flow and cutaneous vasoconstriction. In the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, stimulation of nicotinic receptors increases GI motility and secretion. Through both peripheral and CNS effects, nicotine also causes changes in the endocrine system, including release of prolactin, growth hormone, vasopressin, β-endorphins and adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH), with a subsequent increase in cortisol.33 Although nicotine smokers report that nicotine causes relaxation and relief from anxiety, it is thought that these effects actually occur when periodic nicotine withdrawal is relieved by further nicotine.34 The effects of nicotine are listed in Table 10-3.

The strong psychological dependence associated with nicotine use is supported by the fact that it rapidly acts on the pleasure-producing mesolimbic area of the brain. Withdrawal symptoms start within the first hour or so of the last cigarette and peak in 24–48 hours, gradually fading over a few weeks to several months. Symptoms include craving, restlessness, anxiety, feelings of frustration and hyperirritability. Additional symptoms of withdrawal are presented in Table 10-3. After withdrawal subsides, cue-induced craving may cause smoking relapse months or years later.

COMPLICATIONS

The complications of nicotine use are related to the dose, frequency of use and method of ingestion. Smoking is the most deleterious method of nicotine use. Cigarette smoke contains more than 4000 chemicals and gases, such as carbon monoxide, with at least 45 cancer-causing or tumour-promoting agents and a number of hydrocarbons or solvents. Although nicotine in itself is not believed to be carcinogenic, it is addictive.

The chronic respiratory irritation caused by cigarette smoke (which contains carbon monoxide and multiple poisonous chemicals) is the most important risk factor in the development of lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The toxic gases inhaled in cigarette smoke constrict the bronchi, paralyse the cilia, thicken the mucus-secreting membranes, dilate the distal airways and destroy the alveolar walls. Tar in cigarette smoke contains several hundred chemicals, some of which are carcinogenic.

Chronic irritation from smoking is a major factor in the incidence of cancers of the mouth, larynx and oesophagus in those who smoke tobacco in any form. Carcinogens absorbed into the blood from tobacco smoke may be responsible for the increased incidence of cancers of the bladder, prostate and pancreas in smokers.

The effects of carbon monoxide in cigarette smoke, combined with those of nicotine, cause an increased risk of coronary artery disease. Carbon monoxide has a high affinity with haemoglobin and combines with it more readily than oxygen, reducing oxygen-carrying capacity. Smokers also inhale less oxygen and inhale carbon monoxide they have exhaled, adding to the decrease in available oxygen. Together with the increased myocardial oxygen consumption that nicotine causes, carbon monoxide significantly decreases the oxygen availability to the myocardium. The result is an even greater increase in heart rate and myocardial oxygen consumption, which may lead to myocardial ischaemia.

Passive, or involuntary, smoking occurs under conditions where non-smokers are exposed to cigarette smoke in areas with poor ventilation. Children whose parents smoke have a higher prevalence of respiratory symptoms and respiratory disease. In adults, involuntary or passive smoking is associated with decreased pulmonary function, an increased risk of lung cancer and increased mortality rates from coronary artery disease.33

Women appear to be at greater risk than men of smoking-related diseases. Women who smoke have almost twice the risk of myocardial infarction than men, and may also have nearly double the risk of lung cancer as men who smoke. Smoking in women is also associated with greater menstrual bleeding and duration of dysmenorrhoea, as well as greater variability in the length of their menstrual cycle. In addition, there is some evidence that breast and cervical cancer risk may be increased among women who smoke.35

Although those who use smokeless tobacco (snuff, plug and leaf) have less risk of lung disease compared with smokers, the use of smokeless tobacco is not without complications. Holding tobacco in the mouth increases the risk of cancers of the mouth, cheek, tongue and gingiva nearly 50-fold. Smokeless tobacco users also experience the wide systemic effects of nicotine.33

All users of nicotine in any form may develop complications that are directly related to the effects of nicotine itself. Such complications include an increased risk of peripheral arterial disease, delayed wound healing, reproductive disorders, peptic ulcer disease and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD). Common health problems associated with tobacco use are presented in Table 10-2.

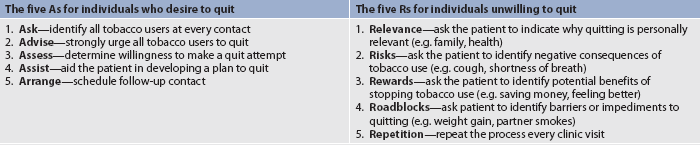

SMOKING CESSATION

A combination of medication, cognitive behavioural approaches and support is believed to be most effective in long-term tobacco cessation. A variety of nicotine replacement systems, in the form of transdermal patches, gum (nicotine polacrilex), nasal spray and nicotine inhalers, can be very effective in assisting smokers to give up by stopping or minimising cravings and withdrawal symptoms. These agents enable the smoker to reduce higher doses of nicotine obtained from cigarettes with a replacement system that offers a steady, slow and reducing delivery of the drug, while facilitating the elimination of the carcinogens and gases associated with tobacco smoke. Bupropion, an antidepressant that does not contain nicotine, can be used to decrease the symptoms of withdrawal, although caution is needed. Close medical assessment prior to use and supervision during use are essential due to the risk of serious side effects.

Participation in tobacco cessation programs can help smokers to focus on other aspects of quitting while they are receiving some relief from withdrawal symptoms through nicotine replacement. Behavioural strategies may assist patients to develop the skills needed to avoid high-risk situations for relapse. Tobacco cessation programs also promote the development of coping skills, such as cigarette refusal skills, assertiveness, alternative activities to cope with stress and use of peer support systems.21,36 The QUIT Program is one such program (see the Resources on p 207). In addition, some hospitals in Australia provide nicotine patches to inpatients to encourage smoking cessation and the federal government has added nicotine replacement therapy to the Pharmaceuticals Benefit Scheme, thus decreasing the cost to individuals.

Women are generally less successful than men in giving up smoking. Some of the reasons for this may include their concern about weight gain, lower responsiveness to nicotine replacement therapy, variability in mood and withdrawal as a function of the menstrual cycle, inadequate emotional support from others, and the possibility that smoking-associated environmental cues may be more influential in smoking behaviour in women than in men.35 The identification of factors that contribute to women’s poorer success in quitting smoking has led to the need for research into understanding this phenomenon and devising smoking cessation approaches that are better suited to women.

Cocaine

CHARACTERISTICS

While cocaine is the most used illicit psychostimulant in the US and Canada, it is less prevalent in Australia and New Zealand, where amphetamine-like substances are more widely used.2,29,37

EFFECTS OF USE

Cocaine is the most potent of the psychoactive stimulants. Its effects have been extensively studied. It serves as the prototype of an addictive stimulant substance. All psychostimulants work in part by increasing the transmission of dopamine in the brain, producing euphoria, increasing energy and prolonging alertness. This action on the pleasure centre in the brain produces a pleasurable effect and can lead to rapid tolerance and dependence.

In addition to stimulation of the CNS, cocaine and other psychostimulants affect the peripheral nervous system and cardiovascular system. Effects include adrenaline-like actions that lead to increased heart rate, blood pressure and body temperature; arrhythmias; marked vasoconstriction; tremor of the hands; nausea or vomiting; and diminished appetite. Additional physical and psychological effects are presented in Tables 10-3 and 10-4. Chronic use may lead to impairment of concentration and memory, irritability, mood swings, paranoia, depression and drug-induced psychosis.34,38 These factors generally subside following abstinence from the drug.

TABLE 10-4 Effects of cocaine and amphetamine use

| Early effects | Long-term effects | |

|---|---|---|

| Central nervous system | Excitation, euphoria, restlessness, talkativeness | Depression, hallucinations, tremors, visual disturbances, seizures, headache, insomnia, stroke |

| Cardiovascular system | Tachycardia, hypertension, angina, arrhythmias, palpitations | Arrhythmias, hypotension, congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy |

| Respiratory system | Increased respiratory rate, dyspnoea, chest pain, epistaxis | Chronic cough, inflamed throat, congestion of lungs, brown/black sputum, pneumonia, respiratory distress and/or arrest, pulmonary oedema, rhinorrhoea, rhinitis, erosion and perforation of the nasal septum |

| Reproductive system | Heightened sexual desire, delayed orgasm and ejaculation; women may have difficulty achieving orgasm | Difficulty in maintaining erection and ejaculation; loss of interest in sexual activity; women may develop aberrant sexual behaviour |

| Gastrointestinal system | Decreased appetite | Dehydration, weight loss, nausea; intestinal ischaemia may cause gangrenous bowel |

| Psychological | Behaviour changes or mood swings | Depression or suicidal thoughts |

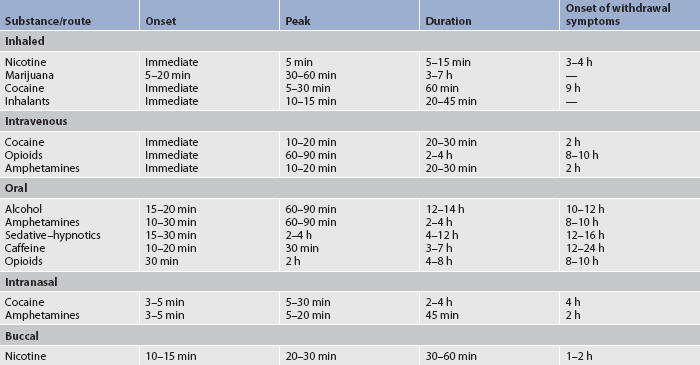

The most common method of administering cocaine is intranasal (snorting), but it may be smoked in ‘freebase’ form, injected intravenously, taken orally or absorbed through the mucous membranes. Smoking and intravenous (IV) methods result in the fastest absorption and highest ‘rush’ sensation. Peak blood levels develop within 5–30 minutes with most methods of administration, and the longest-lasting effects occur following intranasal ingestion.39

During cocaine withdrawal, people often report subtle muscular aches and pains, and an intense psychological response, in particular intense craving in the first 9 hours to 14 days. There is also marked agitation and feelings of depression, exhaustion and the need to sleep excessively (see Table 10-3). Eventually, mood can stabilise and become more normal; however, the desire to return to the drug, especially prompted by craving, is commonly intense and may continue for some time.38

COMPLICATIONS

Complications are directly related to the action of the drug, the route of administration, the dose used and individual vulnerabilities (see Table 10-2). IV administration may result in collapse and scarring of veins at the injection site, cellulitis, wound abscess, endocarditis, hepatitis B and C, and HIV infection. With intranasal use, the nasal septum and mucosa may be damaged, resulting in symptoms such as frequent sniffing and rhinitis, which are common signs of chronic intranasal use.

A psychostimulant-induced psychosis may occur with excessive use of any psychostimulant. It will generally subside with abstinence from the drug but may recur if drug use resumes. Cocaine-induced psychosis usually progresses from paranoid delusions to visual hallucinations of ‘snow lights’ (coloured lights when cocaine is administered) and tactile hallucinations of ‘bugs’ crawling under the skin. Skin excoriations from scratching, needle marks, elevated blood pressure, heart rate and temperature are physiological signs that can help differentiate a stimulant psychosis from schizophrenia.38

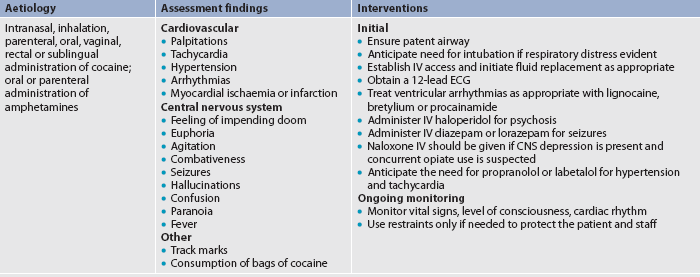

Acute cocaine toxicity may be manifested by cardiac palpitations, tachycardia, increased respiratory rate and fever. At high levels of toxicity, seizures, hypertension, arrhythmias or myocardial ischaemia can occur. The patient experiences restlessness, paranoia, agitated delirium, confusion and repetitive stereotyped behaviours. Death is usually related to stroke, fatal arrhythmias or myocardial infarction.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Individuals who are dependent on cocaine or other psychostimulants may not seek treatment for their drug use issues, but rather for problems such as acute infection, sinusitis, respiratory symptoms, septicaemia, hepatitis B or C, pericarditis, chest pain, headaches, disturbed sleep, poor appetite, depression, anxiety or psychosis. The nurse should be assessing for harmful psychostimulant drug use in any patient with dilated pupils, tachycardia, hyperactivity, fever and/or behavioural abnormalities.

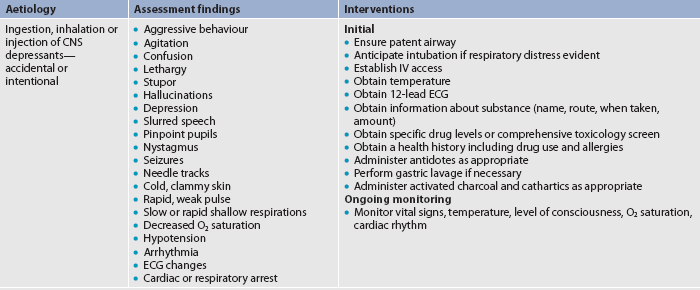

Emergency management of psychostimulant intoxication will depend on the patient’s presentation and any other acute conditions (e.g. injury or acute illness) at the time. The patient’s condition may be complicated by their combined use of the psychostimulant with other pharmaceutical or ‘street’ drugs, including alcohol, benzodiazepines, ketamine, opioids (e.g. codeine, heroin or morphine) or phencyclidine hydrochloride (PCP). Emergency management of cocaine toxicity is presented in Table 10-5.

Amphetamines

CHARACTERISTICS

Specific drugs classified as amphetamines (‘speed’) are identified in Table 10-3. Because medical amphetamines may be prescribed for the treatment of narcolepsy, attention-deficit disorder and weight control, harmful use of these pharmaceuticals can occur through increasing the frequency and amount of the prescribed dose, or procuring these medications illegally. Over the last few years, methamphetamine, including crystal methamphetamine (‘ice’), has overtaken amphetamines as the most commonly used psychostimulant in Australia and New Zealand. This is perhaps due to its strength and accessibility.

Methamphetamine is a synthetic psychoactive illicit drug. Next to cannabis, amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS)—including methamphetamine, crystal methamphetamine and methylene dioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or ecstasy)—are the most widely used illegal drugs in Australia and New Zealand. It is believed that use of these drugs among 15–19-year-olds may be higher in New Zealand than in Australia.29,37 Concern about the use of methamphetamine is related to its harmful effects in terms of health, safety and wellbeing. The manufacture and selling of illicit drugs promotes close links to organised crime. Methamphetamine is commonly identified with violence, antisocial behaviour and mental health problems.39

EFFECTS OF USE

Amphetamines are similar to cocaine in that they stimulate the CNS, peripheral nervous system and cardiovascular system to produce euphoria, hyperactivity, increased heart rate and blood pressure. Initial use results in increased alertness, increased sense of wellbeing, energy, improved performance, relief of fatigue and anorexia. As with cocaine use, amphetamines used regularly over time will cause irritability, anorexia, anxiety, paranoia, hostility, violent behaviour and, for some, amphetamine-induced psychosis (see Table 10-3).

Amphetamines can be taken orally but are often injected intravenously. Onset of action when taken orally is about 30–60 minutes, with the peak cardiovascular effect at 60 minutes and CNS effects at about 2 hours. Duration of effect is about 4–6 hours. Intranasal (snorting) produces effects within a few minutes; smoking and IV use produce even faster effects.12

Amphetamine has a longer half-life than cocaine and, when taken orally, longer lasting effects. Withdrawal symptoms are similar to cocaine withdrawal and are presented in Table 10-3.

COMPLICATIONS

Toxic reactions to amphetamines are similar to those of cocaine. Increased levels of stimulation, sometimes described as ‘overamping’, may result in amphetamine-induced psychosis, paranoia, seizures and death, even if used occasionally (see Table 10-3).10 Without medical intervention, death may occur as a result of arrhythmias, myocardial infarction, hyperthermia or cerebral haemorrhage (stroke). Any young person presenting with any of these conditions needs to be assessed for amphetamine or methamphetamine use/toxicity.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Patients may seek treatment for complications from their amphetamine use, such as injuries, related or unrelated acute illness including bacterial infections, viral infections, cardiac abnormalities, stroke, panic attacks, paranoia, psychosis, toxicity or withdrawal. Emergency management of amphetamine toxicity is the same as that for cocaine and is presented in Table 10-5.

Caffeine

CHARACTERISTICS

Caffeine is the most widely used psychostimulant in the world. As with other psychostimulants, it promotes alertness and alleviates fatigue. However, it is considered safe for most people. Although weaker than other psychostimulants, caffeine shares characteristics of intoxication, tolerance and withdrawal symptoms.

Approximately 80% of adults in North America report a regular intake of caffeine, and 20% of those using caffeine consume doses larger than 350 mg/day, enough to cause tolerance and clinical symptoms of dependence. One 200 mL cup of coffee contains approximately 90–150 mg of caffeine, with the drip preparation yielding the highest amount of caffeine. A cup of tea averages 30–100 mg of caffeine depending on the brewing method. Traditional cola soft drinks average 25–50 mg of caffeine.38 Caffeine is also found in energy drinks and in guarana, which is sometimes incorporated in these preparations.12 In addition to beverages and chocolate, caffeine is found in numerous prescription and over-the-counter analgesics, stimulants, appetite suppressants, and cold and flu preparations.

EFFECTS OF USE

Caffeine is a relatively weak CNS stimulant that is contained in coffee, tea and cocoa products, such as chocolate. It is a diuretic and myocardial stimulant. It relaxes smooth muscles, promotes vasodilation, constricts cerebral arteries, increases gastric acid secretion and enhances contraction of skeletal muscles.

Oral doses of 200 mg (two cups of coffee) can elevate mood, offset fatigue, produce insomnia, increase irritability and, for some consumers, cause anxiety. Chronic or heavy intake of 500 mg or more per day is known to cause intoxication manifested by nervousness, insomnia, gastric hyperacidity, muscle twitching, confusion, tachycardia, cardiac arrhythmias and psychomotor agitation. Ingestion of a lethal dose is extremely rare but could occur with rapid consumption of multiple high-energy drinks containing caffeine, caffeine-containing drugs or oral ingestion of 10 g of caffeine (70–100 cups of coffee).38 The effects of caffeine are presented in Table 10-3.

Physical tolerance and psychological dependence on caffeine have been found with chronic use of more than 500 mg/day. However, dependence may occur in some people at lower doses. The most commonly reported withdrawal symptoms are headache, irritability, drowsiness and fatigue, which occur within 12–24 hours following abstinence (see Table 10-3). Caffeine withdrawal may be responsible for some cases of headache after general anaesthesia. It is thought that weekend headaches may also be related to caffeine withdrawal because caffeine consumption for many individuals is higher during work times than at home.40,41

COMPLICATIONS

Chronic and heavy use of caffeine may cause GI upset, including abdominal pain, diarrhoea and dyspepsia (heartburn). Regular consumers are reported to have slightly higher blood pressure, heart rates and basal metabolic rates (see Table 10-2). Because symptoms of chronic use develop gradually, many people with caffeine dependence do not link their sleep disturbance, irritability, anxiety or other symptoms with their caffeine intake. In toxic doses, caffeine can exacerbate all the symptoms above and precipitate panic states.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Management of the patient with symptoms of caffeine dependence includes assisting them to reduce their intake gradually to a minimal level, or stop their intake of caffeine altogether, at least for a while. Decaffeinated coffee and tea contain only 2–4 mg of caffeine per cup. A list of decaffeinated products may help the patient to reduce or stop their intake by using these substitute foods and beverages. Toxic reactions and lethal doses of caffeine are managed symptomatically, with attention to maintaining normal respiration and controlling hypertension, arrhythmias and seizures (which are rare).12

DEPRESSANTS

Drugs classified as CNS depressants have common physiological and psychological effects. Drugs in this category include alcohol, benzodiazepines and opioids such as codeine, morphine, methadone and heroin. Inhalants are also CNS depressants. Depressants act by increasing GABA and/or opioid activity. GABA is the chief inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS. It can be argued that most CNS depressants are medically useful. For example, benzodiazepines (generally diazepam due to its long half-life) are the drug of choice in preventing and reducing serious alcohol withdrawal symptoms, such as seizures. However, these drugs are recognised for their potential to develop physical tolerance and psychological dependence. Medical emergencies involving this class of drugs include intoxication, overdose and withdrawal.12

Alcohol

CHARACTERISTICS

After caffeine, alcohol is the most widely consumed psychoactive substance in Australia and New Zealand.2,29,37 The use of alcohol, whether by occasional or regular risky drinkers, causes significant problems, including vehicle accidents, boating accidents, arrests, injuries through violence, work accidents, many serious health conditions, poor work performance, educational performance and social problems.12

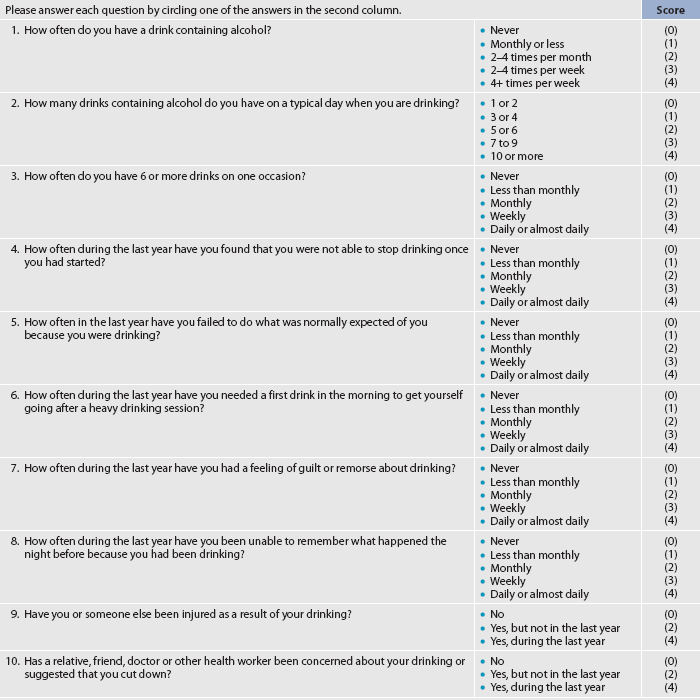

Of all drinkers, less than 10% become alcohol dependent. Alcohol dependence can be a chronic relapsing condition that is potentially fatal if untreated. Numerous factors appear to be interrelated in the development of alcohol dependence, including genetic and biological factors, psychosocial factors and cultural–environmental influences. Alcohol dependence generally occurs over years, but can occur more quickly, and may be preceded by high-risk social drinking (see Fig 10-2).

EFFECTS OF USE

Alcohol affects all organs of the body and has complex effects on the neural transmitters of the CNS.5 Like other psychoactive substances, alcohol causes increased release of dopamine. It depresses all areas and functions of the CNS. The peak action of alcohol is about 60–90 minutes after ingestion. While some alcohol is absorbed through the vascular walls of the stomach, most is absorbed through the walls of the small intestine. Absorption is a little slower in the presence of food, especially proteins and fats. Faster absorption occurs when alcohol is mixed with carbonated liquids. The metabolism of alcohol occurs in the liver; it is excreted in a healthy adult at a rate of approximately one standard drink (10 g pure alcohol) per hour, which is equal to 275 mL of full strength beer, 100 mL of wine, 60 mL of fortified wine or 30 mL of distilled spirits.15

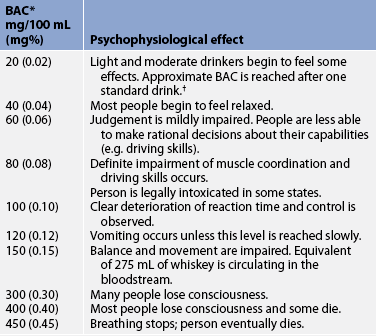

The effects of alcohol are related to the concentration (dose), age, general health status, gender and individual susceptibility of the drinker to the drug’s effects. The concentration of alcohol in the body can be determined by assessing the breath or blood alcohol concentration (BAC). Alcohol may be measured in the blood within 15–20 minutes of ingestion. BAC is affected not only by the amount consumed, but also by body size, body composition, gender and hormones. For the healthy adult drinker who has not developed CNS tolerance, the BAC should generally be predictable according to observation of their intoxicated behaviour and ability to communicate effectively and manage their environment safely (see Table 10-6).12,22

TABLE 10-6 Blood alcohol concentration (BAC) and related effects

*Blood alcohol concentration (BAC) is generally recorded in milligrams of alcohol per 100 mL of blood or milligrams per cent (mg%). Percentage is used for legal definitions of intoxication. BAC is dependent on how much alcohol is consumed, how fast it is consumed and the person’s weight.

†One standard drink is 275 mL beer, 100 mL wine or 30 mL distilled spirits, all of which provide the same amount of alcohol.

Importantly, the relationship between BAC and overt intoxicated behaviour is different in a person who has developed tolerance to alcohol’s effects, compared with a new drinker or person who drinks occasionally and is not tolerant. Someone who is tolerant to alcohol will commonly be able to drink larger amounts without obvious impairment and apparently perform relatively complex tasks at BAC levels several times higher than would be possible for a non-tolerant drinker.12,22

Intoxication is evidenced with increasing BAC and results in diminishing ability to interpret and safely manage the environment, as well as behavioural and physical changes (see Table 10-3). Behavioural effects may include relaxation, sedation, loss of inhibitions, mood swings, aggression, impaired judgement, irritability, euphoria, depression and emotional lability. Physical signs include slurred speech, poor motor coordination, nystagmus (involuntary eye movements) and flushing from dilation of peripheral blood vessels. Disturbances in memory and blackouts may occur among excessive drinkers (e.g. weekly binge drinkers) and dependent drinkers.

After excessive drinking, such as binge drinking over several hours, individuals may experience hangovers manifested by malaise, nausea, headache, thirst and a general feeling of fatigue. In people who are alcohol dependent, sudden withdrawal from ceasing or significantly reducing intake can have life-threatening effects. Withdrawal should be anticipated if a healthy adult male reports consumption of 8 standard drinks (80 g alcohol) or more daily, or almost daily, for at least 2 weeks, or 6 standard drinks (60 g) of alcohol daily for a healthy adult woman. Very young, older, frail or debilitated people may even enter withdrawal at lower regular consumption rates.12

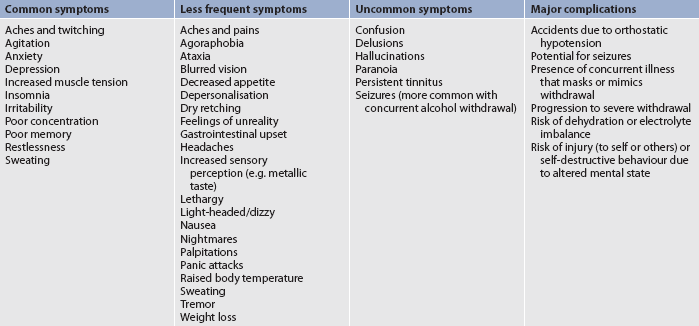

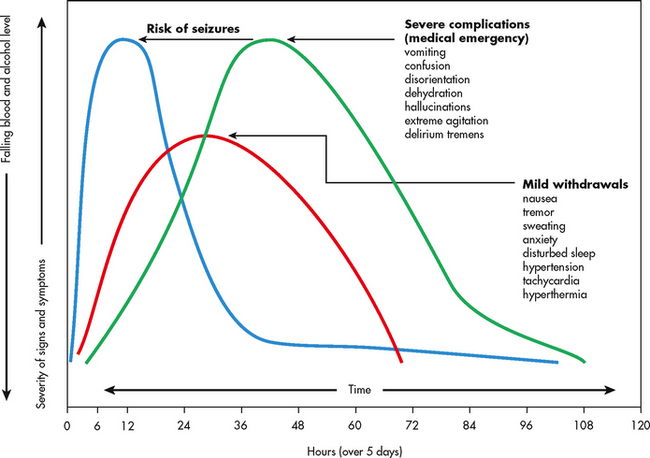

Many people who have developed physical tolerance to alcohol may experience an uncomplicated withdrawal syndrome; however, this is highly unpredictable. Uncomplicated withdrawal starts as the blood alcohol level falls, with symptoms emerging in the first 6–24 hours after the last drink. Withdrawal symptoms generally peak at 24–28 hours and then gradually subside. Acute symptoms may last up to 5 days. Characteristic symptoms include a slight rise in temperature in the early stages, increased blood pressure, increased heart rate, sweating, headache, nausea, vomiting, increasing tremor, anxiety, irritability, increasing sensitivity to light and sound, hyperreflexia and insomnia (see Table 10-3).

Four characteristic signs of severe alcohol withdrawal that is potentially fatal are: gross tremors, seizures, hallucinations and delirium tremens (DTs).12,22 Withdrawal seizures can occur 7–48 hours after the last drink and are a serious complication that must be investigated. Alcohol withdrawal delirium, or delirium tremens, is life-threatening and can occur from 30 to 120 hours after the last drink.12 Delirium components include disorientation, visual or auditory hallucinations and increased hyperactivity. Death may be caused by hyperthermia, electrolyte imbalance, organ shutdown, peripheral vascular collapse and/or cardiac failure.12

COMPLICATIONS

Acute alcohol toxicity can occur with excessive drinking as a one-off event, bouts of binge drinking (consuming 5 or more standard drinks [50 g pure alcohol] in a session of hours not days) or drinking alcohol with other CNS depressants, including pharmaceuticals such as codeine or benzodiazepines. Alcohol-induced CNS depression is life-threatening due to the increasing respiratory and circulatory failure manifested by depressed respiration, hypotension, hypothermia and unconsciousness (see Table 10-3).

Individuals who use alcohol at risky and high-risk levels can have many health problems, including injury and acute and chronic illness. If there are toxic reactions and opioids have been used in conjunction with alcohol, naloxone (an opiate antagonist) may be given. Supportive measures are used to promote ventilation and circulation until the alcohol is metabolised. The patient who is intoxicated with rising BACs should not be given any other depressants because of the risk of overdose due to their additive effects.

Complications may arise from the interaction of alcohol with commonly prescribed or over-the-counter drugs. Drugs that interact with alcohol in an additive manner include opioids, anti-hypertensives, anti-histamines, anti-anginals and salicylates (aspirin). Alcohol taken with aspirin may cause or exacerbate GI bleeding. Alcohol taken with paracetamol may increase the risk of liver damage. Potentiation and cross-tolerance with other CNS depressants may also occur. Potentiation occurs when an additional CNS depressant is taken with alcohol, increasing the overall effect. Cross-tolerance, requiring an increased dose for effect, occurs when an alcohol-dependent (or alcohol-tolerant) individual is administered another CNS depressant and there are similarly decreased effects to the normally administered alcohol.12

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Physical complications of high-risk drinking are outlined in Table 10-7 and are frequently reasons for people to seek healthcare. Treatment of any alcohol-related condition (such as serious injury or illness associated with occasional or non-dependent use), as well as alcohol dependence, requires appropriate multidisciplinary care. In regard to treating alcohol dependence, if the patient is willing, they first need to undergo voluntary, medically supervised alcohol detoxification (defined in Table 10-1) in order to clear their body of alcohol and stabilise their acute condition prior to entering treatment and rehabilitation.22

Management of alcohol withdrawal to prevent complications such as seizures and to settle the overexcited CNS includes the use of a benzodiazepine with a long half-life (e.g. diazepam). A diazepam regimen needs to be individualised to the patient’s situation and prescribed in sufficiently high doses and frequency of administration.12 Diazepam decreases the physiological symptoms and reduces psychological distress, therefore increasing the level of patient comfort and safety by preventing withdrawal seizures and reducing the likelihood of DTs.12 Unlike diazepam, lorazepam does not undergo hepatic oxidation in the liver; instead, it is metabolised in the liver by conjugation. For this reason, lorazepam is relatively unaffected by reduced liver function and may be the preferred benzodiazepine for patients with liver damage. Box 10-1 presents the clinical manifestations of acute alcohol withdrawal and the suggested medication treatment. The patient needs to be observed and monitored closely using the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale, Revised (CIWAR-Ar), as symptoms can escalate rapidly (see the Resources on pp 206–207).12

BOX 10-1 Clinical manifestations of alcohol withdrawal and suggested drug treatment

Drug treatment

Thiamine (prevents Wernicke’s encephalopathy)

Multivitamins (folic acid, B vitamins)

Phenytoin for seizures or past history of seizures

Magnesium sulfate (if serum magnesium is low)

Haloperidol for hallucinations

For DTs: may need IV fluids (do not overhydrate), cooling blanket, well-lit quiet room, consistent staff, frequent vital signs, check for hypoglycaemia, assess for any other health problems

Different treatments are effective for different people with alcohol dependence. For some people, self-modification of drinking patterns is appropriate. They modify their own alcohol use but do not see abstinence as an option. It is important to recognise that someone with dependence still has the capacity to modify their use to less risky consumption levels. For others, detoxification, rehabilitation and sustained abstinence are most appropriate. Patients can receive planned or unplanned medically supervised detoxification in the local hospital or specialist drug and alcohol medical service. They usually need to be referred to the specialist drug and alcohol service for treatment. This may include intensive inpatient or outpatient treatment with particular rehabilitation modalities, psychological therapies, prescribed medications (e.g. acamprosate and/or naltrexone to prevent craving), a relapse prevention program, counselling and social support.