Chapter 22 NURSING ASSESSMENT: integumentary system

1. Describe the structures and functions of the integumentary system.

2. Outline age-related changes in the integumentary system and differences in assessment findings.

3. Identify the significant subjective and objective data related to the integumentary system that should be obtained from the patient.

4. Outline specific assessments to be made during the physical examination of the skin and appendages.

5. Explain the critical components for describing a lesion.

6. Describe the appropriate techniques used in the physical assessment of the integumentary system.

7. Explain the structural and assessment differences in dark skin colour.

8. Differentiate normal from common abnormal findings in a physical assessment of the integumentary system.

9. Outline the purpose, significance of results and nursing responsibilities related to diagnostic studies of the integumentary system.

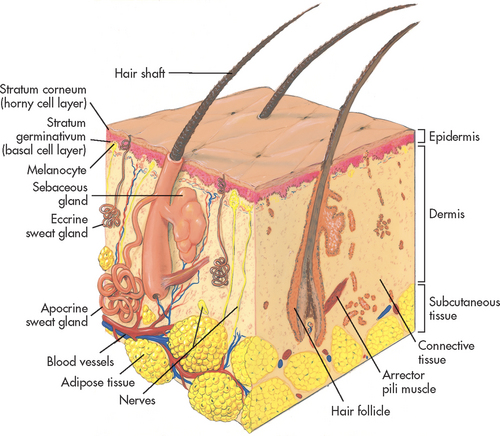

The integumentary system is the largest body organ and is composed of the skin, hair, nails and glands. The skin is further divided into three layers: epidermis, dermis and subcutaneous tissue (see Fig 22-1).

Structures and functions of the skin and appendages

STRUCTURES

The epidermis is the outermost layer of the skin. The dermis, the second skin layer, contains a framework of highly vascular connective tissue. The subcutaneous tissue is composed primarily of fat and loose connective tissue.

Epidermis

The epidermis, the thin avascular superficial layer of the skin, is made up of an outer dead cornified portion that serves as a protective barrier and a deeper living portion that folds into the dermis. Together these layers measure 0.05–0.1 mm in thickness. The epidermis is nourished by blood vessels in the dermis and is replaced with new cells every 30 days. The two types of epidermal cells are the melanocytes (5%) and the keratinocytes (95%).1

Melanocytes are contained in the deep, basal layer (stratum germinativum) of the epidermis. They secrete melanin, a pigment that gives colour to the skin and hair and protects the body from the damaging effects of ultraviolet (UV) sunlight. Sunlight and hormones stimulate melanin production. The wide range of skin and hair colours is caused by the amount of melanin produced; more melanin results in darker skin colour.2

Keratinocytes are synthesised from epidermal cells in the basal layer. Initially these cells are undifferentiated. As they mature (keratinise) they move to the surface, where they flatten and die to form the outer skin layer (stratum corneum). Keratinocytes produce a specialised protein, keratin, which is vital to the protective barrier function of the skin. The upward movement of keratinocytes from the basement membrane to the stratum corneum takes approximately 4 weeks. If dead cells slough off too rapidly, the skin will appear thin and eroded. If new cells form faster than old cells are shed, the skin becomes scaly and thickened. Changes in this cell cycle account for many skin problems.

Dermis

The dermis is the connective tissue below the epidermis. Dermal thickness varies from 1 mm to 4 mm. The dermis is highly vascular and assists in body temperature and blood pressure regulation. It is divided into two layers: an upper thin papillary layer and a deeper, thicker reticular layer. The papillary layer is folded into ridges, or papillae, which extend into the upper epidermal layer. These exposed surface ridges form congenital patterns called fingerprints and footprints. The reticular layer contains collagen and elastic and reticular fibres.

Collagen forms the greatest part of the dermis and is responsible for the mechanical strength of the skin. Elastin fibres, nerves, lymphatic vessels, hair follicles, and sebaceous and sweat glands are also found in the dermis. The primary cell type in the dermis is the fibroblast. Fibroblasts produce collagen and elastin and are important in wound healing.

Subcutaneous tissue

The subcutaneous tissue is below the dermis and is not part of the skin. The subcutaneous tissue is typically discussed with the skin because it attaches the skin to underlying tissues, such as the muscle and bone. In addition, loose connective tissue and fat cells provide insulation. The anatomical distribution of subcutaneous tissue varies according to sex, heredity, age and nutritional status. This layer also stores lipids, regulates temperature and provides shock absorption.

Skin appendages

Appendages of the skin include the hair, nails and glands (sebaceous, apocrine and eccrine). These structures develop from the epidermal layer and receive nutrients, electrolytes and fluids from the dermis. Hair and nails form from specialised keratin that becomes hardened.

Hair grows on most of the body except for the lips, the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet.3 The colour of the hair is a result of heredity and is determined by the type and amount of melanin in the hair shaft. Hair grows approximately 1 cm per month. On average, 100 hairs are lost each day; the rate of growth is not affected by cutting.2 Baldness results when lost hair is not replaced. This absence of hair may be disease- or treatment-related, or due to heredity, particularly in men.

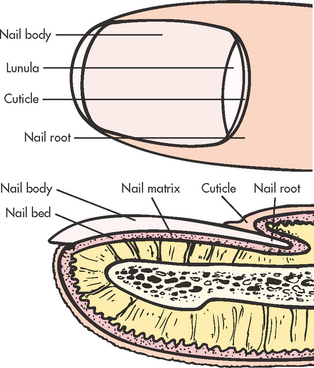

Nails grow from under the lunula, which is the white crescent-shaped area nearest the nail root (see Fig 22-2). The cuticle is part of the stratum corneum, which covers the nail root. The viable part of a nail is called the nail body. Nails grow at a rate of 0.5 mm per week, with toenail growth somewhat slower. Nails can be injured by direct trauma. A lost fingernail usually regenerates in 3–6 months, whereas a lost toenail may require 12 months or more for regeneration. Nail growth may vary according to the person’s age and health. Nail colour ranges from pink to yellow or brown depending on skin colour. Pigmented bands occur in the nail bed in approximately 90% or more of all people with dark skin (see Fig 22-3).

Two major types of glands are associated with the skin: sebaceous and sweat (apocrine and eccrine) glands. The sebaceous glands secrete sebum, which is emptied into the hair follicles. Sebum prevents the skin and hair from becoming dry. Sebum is somewhat bacteriostatic and consists mainly of lipids. These glands depend on sex hormones, particularly testosterone, to regulate sebum secretion and production. Sebum secretion varies across the life span according to sex hormone levels. Sebaceous glands are present on all areas of the skin except the palms of the hands and soles of the feet, and are most abundant on the face, scalp, upper chest and back.

The apocrine sweat glands are located mainly in the axillae, breast areolae and anogenital area. These sweat glands secrete a thick milky substance that becomes odoriferous when altered by skin surface bacteria. These glands enlarge and become active at puberty due to the effects of reproductive hormones. The eccrine sweat glands are widely distributed over the body, except in a few areas, such as the lips: 25 mm2 of skin contains about 3000 of these sweat glands. Sweat is a transparent watery solution composed of salts, ammonia, urea and other wastes. These glands function to cool the body by evaporation, to excrete waste products through the pores of the skin and to moisturise surface cells.

FUNCTIONS OF THE INTEGUMENTARY SYSTEM

The primary function of the skin is to protect the underlying tissues of the body by serving as a surface barrier to the external environment. The skin also acts as a barrier against invasion by bacteria and viruses and prevents excessive water loss. The fat of the subcutaneous layer insulates the body.

The skin, with its nerve endings and special receptors, provides sensory perception for environmental stimuli. These highly specialised nerve endings supply information to the brain related to pain, heat and cold, touch, pressure and vibration. The skin controls heat regulation by responding to changes in internal and external temperature with vasoconstriction or vasodilation. Related to heat regulation is the skin’s function of excretion. Between 600 and 900 mL of water is lost daily through insensible perspiration. In addition, sebum and sweat are secreted by the skin and lubricate the skin surface. Endogenous synthesis of vitamin D, which is critical to calcium and phosphorus balance, occurs in the epidermis. Vitamin D is synthesised by the action of UV light on vitamin D precursors in epidermal cells.

The aesthetic functions of the skin include the mirroring of various emotions, such as anger or embarrassment, as well as displaying the individual identity of a person. The role of absorption at the cutaneous level is a subject of ongoing research and an increasing number of drugs are effectively delivered via patches applied directly to the skin.

Assessment of the integumentary system

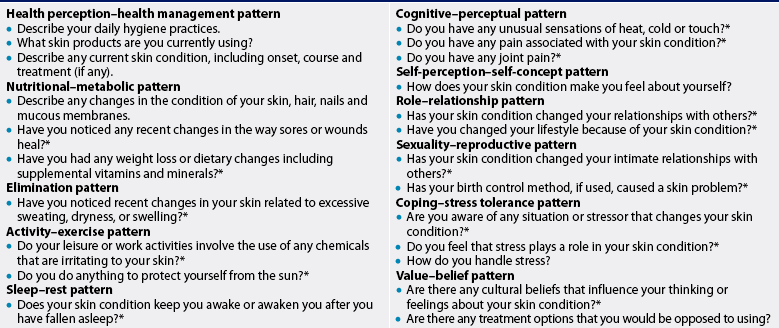

Assessment of the skin begins at the initial contact with the patient and continues throughout the examination. Specific areas of the skin are examined during examination of other areas of the body unless the chief complaint is that of a dermatological nature. A general statement about the physical condition of the skin should be recorded (see Box 22-1) and specific problems should be noted under the appropriate system. In addition, health history questions (see Table 22-2) should be asked when a skin problem is noted.

BOX 22-1 Normal physical assessment of the integumentary system

Skin: even-toned and warm; good elasticity; no petechiae, purpura, lesions or excoriations.

Nails: pink, round and mobile with 160° angle.

Hair: shiny and full; amount and distribution appropriate for age and sex; no flaking of scalp, forehead or auricle.

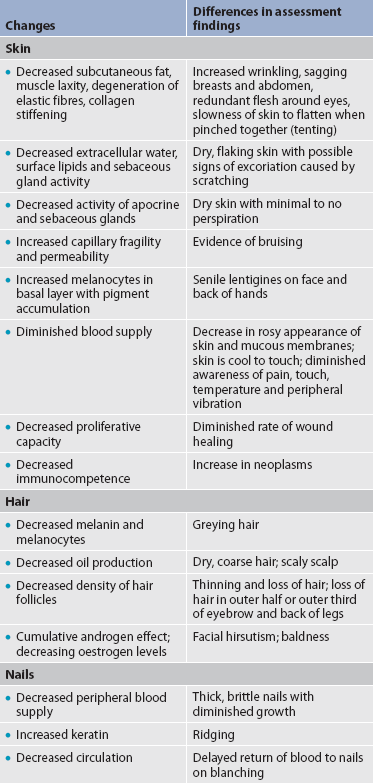

Gerontological considerations: effects of ageing on the integumentary system

There are numerous changes in the skin of the ageing person. Although many changes are not serious except for their cosmetic effects, others are more serious and need careful evaluation. Age-related changes of the integumentary system and differences in assessment findings are listed in Table 22-1.

The rate of age-related skin changes is influenced by heredity and a personal history of sun exposure, hygiene practices, nutrition and general state of health. Skin changes that are related to ageing include decreased firmness and flexibility, dryness, roughness, wrinkling and benign neoplasms.

The junction between the dermis and the epidermis becomes flattened with age and the epidermis contains fewer melanocytes. In addition, the dermis loses volume and has fewer blood vessels. Scalp, pubic and axillary hair becomes depigmented and thinner. A loss of melanin results in grey or white hair. The nail body thins and nails become brittle, thicker and more prone to splitting and yellowing.

Chronic exposure to UV rays is the major contributor to the wrinkling of skin. Sun damage to the skin is cumulative (see Fig 22-4).4 The wrinkling of sun-exposed areas, such as the face, is more marked than in sun-shielded areas, such as the buttocks. Poor nutrition contributes to ageing of the skin, resulting from a decreased intake of protein, kilojoules and vitamins. With ageing, collagen fibres stiffen, elastic fibres degenerate and the amount of subcutaneous tissue decreases. These changes, with the added effects of gravity, lead to wrinkling.

Figure 22-4 Photoageing. Bleeding occurs with minor injury to the sun-damaged surfaces of the hands.

Benign neoplasms related to the ageing process can occur on the skin. These growths include seborrhoeic keratoses, cherry angiomas and skin tags. A common premalignant lesion is an actinic keratosis, which appears on areas of chronic sun exposure, especially in the person who has a fair complexion and light eyes (blue, green or hazel). These cutaneous lesions place an individual at increased risk of squamous cell carcinomas. The ageing person is more susceptible to skin cancers because there is a decline in the capacity to repair cellular (especially DNA) damage caused by sun exposure.

Decreased subcutaneous fat leads to an increased risk of trauma injury, hypothermia and skin shearing, which may lead to pressure ulcers. With ageing, the eccrine and apocrine sweat glands atrophy, causing dry skin and decreased body odour. The growth rates of the hair and nails decrease as a result of atrophy of the involved structures. Vitamin deficiencies can cause dry, thin hair that has a tendency to fall out.

The visible effects of ageing on the skin and hair may have a profound psychological effect on many people. A youthful look may be tied to a person’s self-image. Although wrinkling skin, thinning hair and brittle nails are normal changes with ageing, they may result in an altered self-image.5

SUBJECTIVE DATA

Important health information

Past health history

Past health history will indicate previous trauma, surgery or prior disease that involves the skin. The nurse should determine whether the patient has noticed any dermatological manifestations of systemic problems, such as jaundice (liver disease), delayed wound healing (diabetes mellitus), cyanosis (respiratory disorder) and pallor (anaemia). Table 23-12 lists diseases with dermatological manifestations. Specific information related to food, pets and drug allergies, and skin reactions to insect bites and stings should also be obtained. A history of chronic or unprotected exposure to UV light, as well as radiation treatment, should be noted.

Medications

The patient should be questioned about skin-related problems that have occurred as a result of taking prescription or over-the-counter medications. A thorough medication history is important, especially in relation to vitamins, corticosteroids, hormones, antibiotics and antimetabolites, because these medications may often cause side effects that are manifested in the skin. The nurse should document the use of prescription or over-the-counter medications used specifically to treat a primary skin problem, such as acne, or a secondary skin problem, such as itching. If a preparation is used, the name, duration of use, method of application and effectiveness of the medication should be recorded.

Surgery or other treatments

It is important to determine whether any surgical procedures, including cosmetic surgery, have been performed on the skin. If a biopsy was done, the result should be recorded. Any treatments specific for a skin problem, such as phototherapy, or for a health problem, such as radiation therapy, should be noted. In addition, treatments undergone for primarily cosmetic purposes, such as tanning booth use or cosmetic peels, should also be documented.

Functional health patterns

Health perception–health management pattern

The nurse should ask about the patient’s health practices related to the integumentary system, such as the usual self-care habits related to daily hygiene. The frequency of use and sun protection factor (SPF) number of sunscreen products and clothing should be documented. Assessment of the use of personal care products (e.g. shampoos, moisturising agents, cosmetic products), including brand name, quantity and frequency, should be noted. A description of any current skin problem, including onset, symptoms, course and treatment, should be recorded. Medications used for treating hair loss must also be noted.

Information should be obtained about family history of any skin diseases, including congenital and familial diseases (e.g. alopecia [partial or complete lack of hair] and psoriasis) and systemic diseases with dermatological manifestations (e.g. diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, cardiovascular diseases and immune disorders). In addition, a family and personal history of skin cancer, particularly melanoma, should be noted.

Nutritional–metabolic pattern

The nurse should question the patient about any changes in the condition of skin, hair, nails and mucous membranes, and whether they are related to dietary changes. A diet history reveals the adequacy of nutrients essential to healthy skin, such as vitamins A, D, E and C, dietary fat and protein. Food allergies that cause a skin reaction should also be noted. Obese patients should be asked if they have areas of chafing or maceration in intertriginous (overlapping) areas, where skin surfaces overlap and rub on each other (e.g. below the breasts, in the axillae and groin). The amount and frequency of sweating should be noted. Question the patient about any poor or delayed wound healing, and record this information if it has occurred.

Elimination pattern

The patient should be questioned about conditions of the skin, such as dehydration, oedema and pruritus, which can indicate alterations in fluid balance. If urinary or faecal incontinence is a problem, the condition of the skin in the anal and perineal areas should be determined.

Activity–exercise pattern

Information should be obtained about environmental hazards in relation to hobbies and recreational activities, including exposure to sun, known carcinogens, chemical irritants and allergens. The patient should be asked if any changes occur in the skin during exercise or other activities.

Sleep–rest pattern

The patient should be questioned about disturbances in sleep patterns caused by a skin condition. For example, pruritus can be distressing and cause major alterations in normal sleep patterns. Also, poor sleep and resulting tiredness are often reflected in a patient’s face by dark circles under the eyes and a decreased firmness in the facial skin.

Cognitive–perceptual pattern

The nurse should ascertain the patient’s perception of the sensations of heat, cold, pain and touch. Discomfort associated with a skin condition should be noted, especially when observed in intact skin. Joint pain related to the patient’s skin condition should also be recorded.

Self-perception–self-concept pattern

Assessment should be made of any feelings of sadness, anxiety or despair in relation to the patient’s skin condition. The patient should be observed for signs of decreased self-esteem and a poor or altered body image.

Role–relationship pattern

It is important to determine how the patient’s skin condition affects relationships with family members, peers and work associates. Assessment should be made of the changes in lifestyle that have occurred as a result of the skin condition.

The patient should also be questioned regarding the effect of environmental factors on the skin, such as occupational exposure to irritants, sun and unusually cold or unhygienic conditions. Contact dermatitis caused by allergies and irritants is a common skin problem associated with occupation.

Sexuality–reproductive pattern

The nurse should tactfully question and assess the effect of the patient’s skin condition on sexual activity. The nurse should also make note of the reproductive status of the female patient with regard to possible therapeutic interventions. For example, isotretinoin, which is used to treat cystic acne, is a teratogenic drug that may cause abnormal fetal development and consequently should not be used by a woman of child-bearing age unless adequate contraceptive measures are taken.

OBJECTIVE DATA

Physical examination

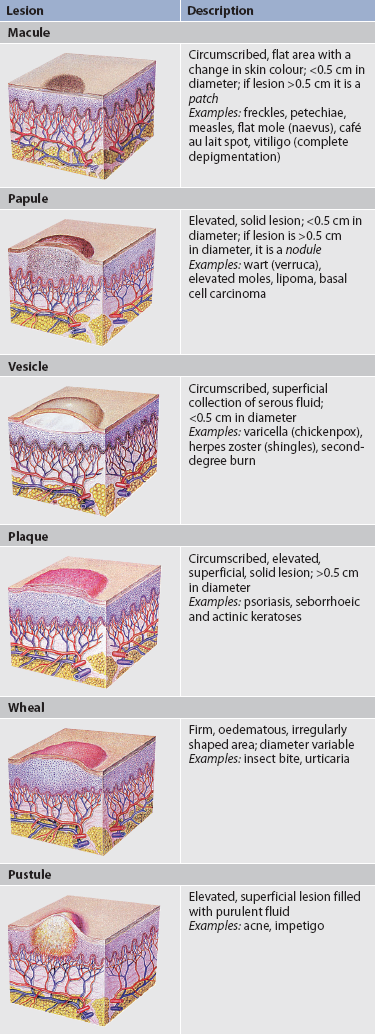

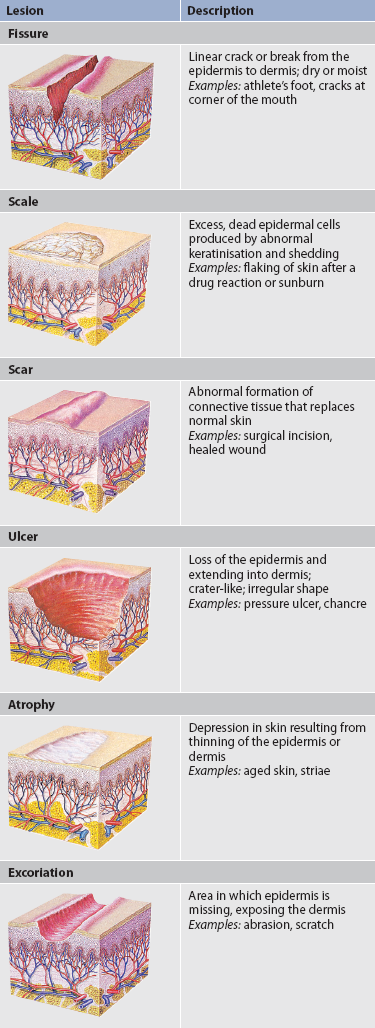

Primary skin lesions develop on previously unaltered skin. The common characteristics of primary skin lesions are shown in Table 22-3. Secondary skin lesions are lesions that change with time or because of a factor such as scratching or infection. Secondary skin lesions are shown in Table 22-4. General principles when conducting an assessment of the skin are as follows:

1. Have an appropriate examination room of moderate temperature with good lighting; a room with exposure to daylight is preferred.

2. Ensure that the patient is comfortable and in clothing or a dressing gown that allows easy access to all skin areas.

3. Be systematic and proceed from head to toe.

5. Perform a general inspection and then a lesion-specific examination.

6. Use appropriate terminology and nomenclature when reporting or documenting.

Photographs are important for accurate reporting and monitoring of healing.

Inspection

The skin is inspected for general colour and pigmentation, vascularity or bruising, and the presence of lesions or discolouration. The critical factor in assessment of skin colour is change. A skin colour that is normal for a particular patient can be a sign of a pathological condition in another patient. The colour of the skin depends on the amounts of melanin (brown), carotene (yellow), oxyhaemoglobin (red) and reduced haemoglobin (bluish-red) present at a particular time. The most reliable areas in which to assess colour are the areas of least pigmentation, such as the sclera, conjunctiva, nail beds, lips and buccal mucosa. Activity, emotions, cigarette smoking and oedema, as well as respiratory, renal, cardiovascular and hepatic disorders, can all directly affect the colour of the skin. Table 22-5 describes assessment variations in light- and dark-skinned individuals.

TABLE 22-5 Assessment variations in light- and dark-skinned individuals

| Clinical sign | Light skin | Dark skin |

|---|---|---|

| Cyanosis | Greyish-blue tone, especially in nail beds, ear lobes, lips, mucous membranes, and palms and soles of feet | Ashen or grey colour most easily seen in the conjunctiva of the eye, mucous membranes and nail beds |

| Ecchymosis | Dark-red, purple, yellow or green colour, depending on age of bruise | Purple to brownish-black; difficult to see unless occurring in an area of light pigmentation |

| Erythema | Reddish tone, possibly accompanied by increased skin temperature secondary to localised inflammation | Deeper brown or purple skin tone with evidence of increased skin temperature secondary to inflammation |

| Jaundice | Yellowish colour of skin, sclera, fingernails, palms of hands and oral mucosa | Yellowish-green colour most obviously seen in sclera of eye (do not confuse with yellow eye pigmentation, which may be evident in dark-skinned patients), palms of hands and soles of feet |

| Pallor | Pale skin colour that may appear white or ashen, also evident on lips, nail beds and mucous membranes | Underlying red tone in brown or black skin is absent. Light-skinned Indigenous people may have yellowish brown skin; dark-skinned Indigenous people may appear ashen or grey |

| Petechiae | Lesions appear as small, reddish-purple pinpoints, best observed on abdomen and buttocks | Difficult to see; may be evident in the buccal mucosa of the mouth or conjunctiva of the eye |

| Rash | May be visualised as well as felt with light palpation | Not easily visualised but may be felt with light palpation |

| Scar | Generally heals, showing narrow scar line | Higher incidence of keloid development, resulting in a thickened, raised scar |

The skin should also be examined for possible problems related to vascularity, such as areas of bruising, and vascular and purpuric lesions, such as angioma (benign tumour of blood or lymph vessels), petechiae (tiny purple spots on skin) or purpura (bleeding disorder causing ecchymosis or petechiae). Reaction to direct pressure should be noted. If a lesion blanches on direct pressure and then refills, the redness is due to dilated blood vessels. If the discolouration remains, it is the result of subcutaneous or intradermal bleeding. Any pattern of bruising, for example in the shape of the hand or fingers or bruises at different stages of resolution, should be noted. These may be indications of other health problems or abuse and should be investigated further.

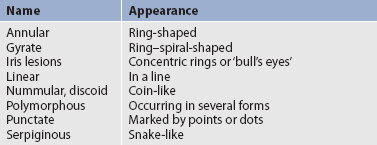

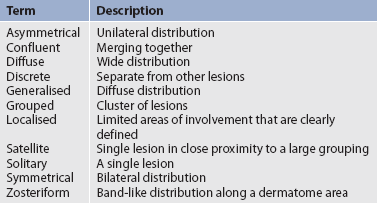

If lesions are found on the skin, the colour, size, distribution, location and shape should be recorded. Skin lesions are usually described in terms related to the lesions’ configuration (pattern in relation to other lesions; see Table 22-6) and distribution (arrangement of lesions over an area of skin; see Table 22-7).

During systematic inspection it is important to note any unusual odours. Colonised lesions and overgrowth of yeast in calluses or intertriginous areas are often associated with distinctive odours. Tattoos and needle-track marks should be examined and noted for location and the characteristics of the surrounding skin area.

Inspection of the hair should include an examination of all body hair. Note the distribution, texture and quantity of hair. Changes in the normal distribution of body hair and growth may indicate an endocrine disorder. Inspection of the nails should include a careful examination of nail shape, thickness, curvature and surface. Any grooves, pitting or ridges should be noted. Changes in nail smoothness or thickness can occur with anaemia, psoriasis, thyroid problems and decreased vascular circulation.

Palpation

The skin is palpated to provide information about temperature, turgor and mobility, moisture and texture. Temperature of the skin is best assessed by using the backs of the hands. The skin should be warm without being hot. The temperature of the skin increases when blood flow to the dermis is increased. There will be a localised temperature increase with burns and local inflammation. A generalised increase in temperature will result from fever. A decreased body temperature may occur when shock, chilling or emotional distress is present.

Turgor and mobility refer to the elasticity of the skin. The nurse assesses this by gently pinching an area of skin under the clavicle. Skin with good elasticity should move easily when lifted and should immediately return to its original position when released. There is a loss of elasticity with dehydration and ageing that often causes tenting (see Table 22-8).

COMMON ASSESSMENT ABNORMALITIES

| Finding | Description | Possible aetiology and significance |

|---|---|---|

| Alopecia | Loss of hair (localised or general) | Heredity, friction, rubbing, traction, trauma, stress, infection, inflammation, chemotherapy, pregnancy, emotional shock, tinea capitis, immunological factors |

| Angioma | Tumour consisting of blood or lymph vessels | Normal increase with ageing, liver disease, pregnancy, varicose veins |

| Carotenaemia (carotenosis) | Yellow discolouration of skin, no yellowing of sclerae, most noticeable on palms and soles | Vegetables containing carotene (e.g. carrots, squash), hypothyroidism |

| Comedo (blackheads and whiteheads) | Keratin, sebum microorganism and epithelial debris within a dilated follicular opening | Acne vulgaris |

| Cyanosis | Slightly bluish-grey or dark purple discolouration of the skin and mucous membranes caused by the presence of excessive amounts of reduced haemoglobin in the capillaries | Cardiorespiratory problems; vasoconstriction, asphyxiation, anaemia, leukaemia and malignancies |

| Cyst | Sac containing fluid or semisolid material | Obstruction of a duct or gland, parasitic infection |

| Depigmentation (vitiligo) | Congenital or acquired loss of melanin resulting in white, depigmented areas | Genetic, chemical and pharmacological agents, nutritional and endocrine factors, burns and trauma, inflammation and infection |

| Ecchymosis | Large, bruise-like lesion caused by collection of extravascular blood in dermis and subcutaneous tissue | Trauma, bleeding disorders |

| Erythema | Redness occurring in patches of variable size and shape | Heat, certain drugs, alcohol, ultraviolet rays, any problem that causes dilation of blood vessels to the skin |

| Haematoma | Extravasation of blood of sufficient size to cause visible swelling | Trauma, bleeding disorders |

| Hirsutism | Male distribution of hair in women | Abnormality of ovaries or adrenal glands, decrease in oestrogen level, familial trait |

| Intertrigo | Erythematous irritation of opposing skin surfaces caused by friction | Moisture, obesity, Candida infection, friction |

| Jaundice | Yellow (in light-skinned people) or yellowish-brown (in dark-skinned people) discolouration of the skin, best observed in the sclera, secondary to increased bilirubin in the blood | Liver disease, red blood cell haemolysis; pancreatic cancer, common bile duct obstruction |

| Keloid | Hypertrophied scar beyond margin of incision or trauma | Predisposition more common in dark-skinned individuals |

| Lichenification | Thickening of the skin with accentuated skin markings | Repeated scratching, rubbing and irritation |

| Mole (naevus) | Benign overgrowth of melanocytes | Defects of development; excessive numbers and large, irregular moles; often familial |

| Petechiae | Pinpoint, discrete deposit of blood less than 1–2 mm in the extravascular tissues and visible through the skin or mucous membrane | Inflammation, marked dilation, blood vessel trauma, blood dyscrasia that results in bleeding tendencies (e.g. thrombocytopenia) |

| Telangiectasia | Visibly dilated, superficial, cutaneous small blood vessels, commonly found on face and thighs | Ageing, acne, sun exposure, alcohol, liver failure, corticosteroids, radiation, certain systemic diseases, skin tumours; normal variant |

| Tenting | Failure of skin to return immediately to normal position after gentle pinching | Ageing, dehydration, cachexia |

| Varicosity | Increased prominence of superficial veins | Interruption of venous return (e.g. from tumour, incompetent valves, inflammation) |

Moisture of the skin is the dampness or dryness of the skin. Moisture increases in intertriginous areas and with high humidity. The amount of moisture on the skin varies with environmental temperature, muscular activity, body weight and body temperature. The skin should be intact with no flaking, scaling or cracking. Skin generally becomes drier with increasing age.

Texture refers to the fineness or coarseness of the skin. The skin should feel smooth and firm with the surface evenly thin in most areas. Thickened callus areas are normal on the soles and palms and relate to weight-bearing. Increased thickness is often work related and is a result of excessive pressure.

The Clinical practice box can be used to evaluate the status of previously identified integumentary problems and to monitor for signs of new problems. Common assessment abnormalities of the skin are described in Table 22-8.

Many assessment and classification tools have been developed to assist nurses to collect systematic, reliable and objective information about particular integumentary problems. Examples of tools that are commonly used by nurses include the Braden Pressure Ulcer Scale (see Ch 12) and the STAR Classification for skin tears (see Resources on p 517).

Integumentary system: focused assessment

CLINICAL PRACTICE

Use this checklist to make sure the key assessment steps have been done.

Subjective

Ask the patient about any of the following and note responses.

| Hair loss (unusual or rapid) | Y N |

| Changes in skin (e.g. lesions, bruising) | Y N |

| Nail discolouration | Y N |

Objective: diagnostic

Check the following for results and critical values.

| Biopsy results | ✓ |

| Albumin | ✓ |

ASSESSMENT OF DARK SKIN COLOUR

A normal range of differences exists in the physical examination of skin, hair and nails. Genetic factors determine the skin colour of the individual, which can vary from white to dark brown with overtones of yellow, olive and red. The darker skin tones result from the reflection of light as it strikes the underlying skin pigment. An increased amount of melanin pigment produced by the melanocytes results in the darker skin colour. This increased melanin forms a natural sun shield for dark skin and results in a decreased incidence of skin cancer in these individuals.

The structures of dark skin are no different from those of lighter skin but they are often more difficult to assess (see Table 22-5). Assessment of colour is more easily made in areas where the epidermis is thin and pigmentation is lighter, such as the lips, mucous membranes, palms and nail beds. Rashes are often difficult to observe and may need to be palpated.6 Light-skinned individuals wrinkle at a younger age than dark-skinned individuals due to sun exposure.

Indigenous Australians are more prone to discoid lupus erythematosus than non-Indigenous Australians. This occurs typically on the lips and can be complicated by squamous cell carcinoma.7 Keloid scarring, which is overgrowth of collagenous tissue at a site of skin injury, and Mongolian spots, which are benign bluish-black macules, are also more common in the Polynesian and Australian Indigenous populations. Because of the darkness of the skin of some individuals, colour often cannot be used as an indicator of systemic conditions (e.g. flushed skin with fever). Cyanosis may be difficult to determine because a bluish hue commonly occurs in dark-skinned persons.

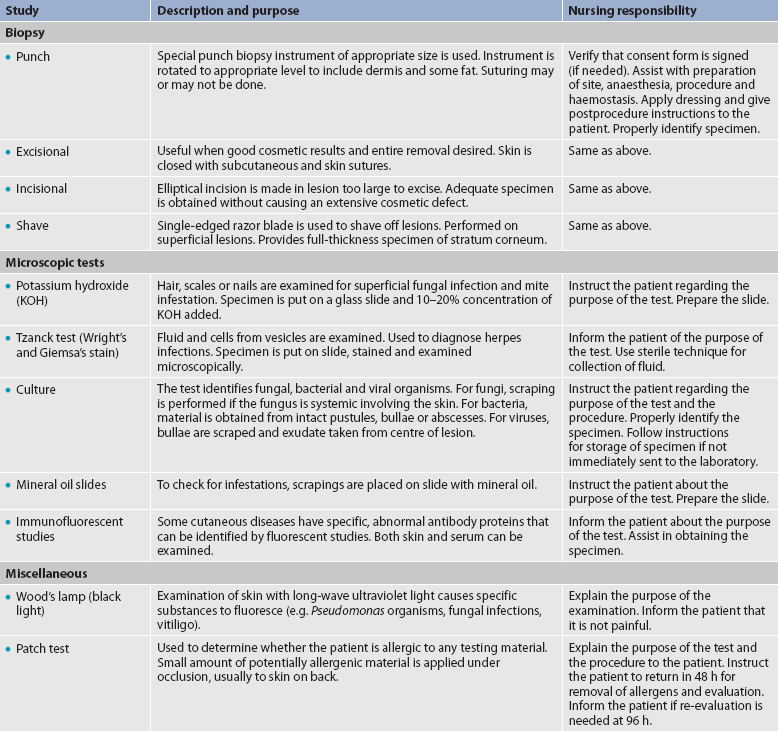

Diagnostic studies of the integumentary system

Diagnostic studies provide important information to the nurse in monitoring the patient’s condition and planning appropriate interventions. These studies are considered to yield objective data. Table 22-9 lists diagnostic studies common to the integumentary system.

The main diagnostic techniques related to skin problems are inspection of an individual lesion and a careful history related to the problem. If a definitive diagnosis cannot be made by these techniques, additional tests may be indicated.

Biopsy is one of the most common diagnostic tests used in the evaluation of skin lesions. A biopsy is indicated in all conditions in which a malignancy is suspected or a specific diagnosis is questionable. Techniques include punch, incisional, excisional and shave biopsies. The method used is related to factors such as the site of the biopsy, the cosmetic result desired and the type of tissue to be obtained.

Other diagnostic procedures used include stains and cultures for fungal, bacterial and viral infections. Immunofluorescence is a special technique used on biopsy specimens and may be indicated in certain conditions, such as bullous diseases and systemic lupus erythematosus. Patch testing and photopatch testing may be used in the evaluation of allergic contact dermatitis and photoallergic reactions.2

1. The primary function of the skin is:

2. Age-related changes in the skin include:

3. When assessing the sleep–rest pattern in relation to the skin, the nurse questions the patient regarding:

4. During the physical examination of a patient’s skin, the nurse would:

5. Skin lesions found by the nurse and described as firm, oedematous and irregularly shaped areas of varying diameter are called:

6. To assess the skin for temperature and moisture, the most appropriate technique is:

7. Individuals with dark skin are more likely to develop:

8. On inspection of the patient’s skin, the nurse notes the complete absence of melanin pigment in patchy areas on the patient’s hands. This condition is called:

1 Patton KT, Thibodeau GA. Anatomy and physiology, 7th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2010.

2 Freedberg I, et al. Fitzpatrick’s dermatology in general medicine, 7th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008.

3 Thibodeau GA, Patton KT. Structure and function of the body, 13th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2008.

4 Helfrich Y, Sachs D, Voorhees J. Overview of skin aging and photoaging. Dermatol Nurs. 2008;20:177.

5 Jarvis C. Physical examination and health assessment, 5th edn. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2008.

6 Wilson S, Giddens J. Health assessment for nursing practice, 4th edn. Louis: Mosby, 2009.

7 Green AC. A handbook of skin conditions in Aboriginal populations of Australia. Melbourne: Blackwell Science Asia, 2001.

STAR Classification for skin tears. www.silverchain.org.au/assets/files/STAR-Skin-Tear-tool-04022010.pdf

See also Chapter 23.