Foreword

The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee year of 2012 has shone light not just on Elizabeth II and her sixty years on the throne, but also on the institution she heads. Over the years, many books have been written about this, the grandest and best-known of the world’s monarchies, and its individual members, both past and present. Almost without exception, their authors have concerned themselves exclusively with events – and people – on this side of the Channel, venturing across the water only in so far as it is necessary to describe the Germanic origins of the House of Windsor. By contrast, most Britons know little about Europe’s other monarchies, whether the Scandinavian, Belgian, Dutch or Spanish, beyond the occasional mentions of their sexual or financial indiscretions that appear in glossy magazines or on the foreign pages of newspapers.

Yet these Continental royal families have much more in common with ours than we might think, and not only because of the manner in which they are linked by intermarriage. True, there are considerable national variations, yet the fundamental issues facing the different monarchies are similar – whether their political roles, the way they are financed, their relationship with the media or their position in society. So too are the challenges they face – chief among them the need to ensure the continued relevance of the institutions they head in the twenty-first century.

If opinion polls are to be believed, they have all succeeded in this task. A series of recent events – from the marriage in June 2010 of Crown Princess Victoria of Sweden and in April the following year of Britain’s Prince William, through to 2012’s Jubilees, not just of Queen Elizabeth but also of Queen Margrethe II of Denmark, who in January marked forty years on her throne – have served to underline the continuing importance of Europe’s royal families in the lives of their respective countries – as well as to demonstrate the enormous affection they inspire among their subjects.

It is the aim of this book to put the Windsors into this broader, European context, comparing and contrasting them with their Continental counterparts. I hope it proves illuminating – and will lead you to look at our own royal family in a different light.

– Peter Conradi, London, April 2012

Introduction

It was just after nine a.m. on a cold and wet January day in 1793 that they came for the King. At his own request, Louis-Auguste, king of France and Navarre, had been woken by his valet, Jean-Baptiste Cléry, four hours earlier and celebrated Mass for the last time in a room of the Tour du Temple, the medieval fortress in what is now the 3rd arrondissement of Paris, where he had been held since the previous August. The ornaments had been borrowed from a nearby church; a chest of drawers served as the altar. His prayers finished, the King gave Cléry a series of objects to pass to his wife and children.

“Cléry, tell the Queen, my dear children and my sister that I had promised to see them this morning, but wanted to spare them the pain of such a cruel separation,” he told his valet. “How much it makes me suffer to leave without receiving their last embraces.”

Then Louis was led outside, where a guard of 1,200 horsemen stood ready to escort him on the journey to his place of execution. Seated with him in the carriage was Henry Essex Edgeworth, an Irish-born priest brought up by the Jesuits in Toulouse, who had became confessor first to the King’s sister, Élisabeth, and then to the King himself. It was Edgeworth who had conducted the service in the fortress.

Louis, then thirty-nine, had been dauphin since the death of his father when he was just eleven, and had succeeded to the throne in 1774 at the age of twenty. Weak and indecisive, he had mishandled the growing political and economic crisis in which he became enveloped. France was declared a republic on 21st September 1792, and in December of that year he went on trial before the National Convention accused of high treason and various crimes against the state. The guilty verdict was a foregone conclusion, but Louis’s fate was not. A sizeable minority of members of the Convention argued for imprisonment or exile, but the majority prevailed: the King must die.

When the carriage stopped in the Place de la Révolution (now the Place de la Concorde), Louis knew his end was near. “We are arrived, if I mistake not,” he whispered. Edgeworth’s silence confirmed it. Surrounded by gendarmes, he was led to the scaffold, brushing off all attempts to tie his hands.

The path was rough and difficult to pass, and the King walked slowly, leaning on Edgeworth for support. When he reached the last step, he let go of the priest’s arm, his pace quickened and, with one look, he silenced the ranks of drummers opposite him. Speaking loudly and clearly, he declared: “People of France, I die innocent. It is on the brink of the grave and ready to appear before God that I attest my innocence. I forgive those responsible for my death and I pray to God that my blood never falls on France.”

Louis’s head was severed with one stroke of the guillotine. The youngest of the guards, who was eighteen, displayed it to the people as he walked round the scaffold, accompanying it with what Edgeworth described as the “most atrocious and indecent gestures”. The crowd were first stunned into silence, but then, cries of Vive la République! began to ring out. “By degrees the voices multiplied and in less than ten minutes this cry, a thousand times repeated, became the universal shout of the multitude, and every hat was in the air,” the priest recalled.

Nine months later, Louis’s Austrian-born queen, Marie Antoinette, went to the guillotine too, after a sham of a trial in which she was accused, among other things, of sexually abusing her son. Her last words were more prosaic than those of her husband. “Pardon me, sir, I meant not to do it,” she said to the executioner, whose foot she accidentally stepped on before she died.

The revolution of 1789 that led to the death of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette appeared to signal the beginning of a new age. As Napoleon’s armies spread revolutionary ideas across Europe, borders were redrawn, new countries appeared and kings were forced into exile. Yet far from bringing the end of the monarchy, the decades that followed the French Revolution saw the institution flourish – a reaction, in part, to the bloody excesses that had followed. This was the case even in France itself where, in 1814, the Bourbon dynasty returned in the form of Louis’s younger brother, Louis-Stanislas-Xavier, who ruled as Louis XVIII for a decade before he was succeeded by another sibling, Charles.

When new nation states came into existence in the years after the Congress of Vienna, it seemed self-evident that they should be headed by kings. The Netherlands, for centuries a republic ruled by a series of stadtholders, became a monarchy in 1815, as did Belgium and Greece when they became independent states in the 1830s. The unification of Italy in 1861 transformed Vittorio Emanuele II, ruler of Piedmont, Savoy and Sardinia, into the king of Italy; a decade later, in the aftermath of his victory over the French, King Wilhelm of Prussia was proclaimed German kaiser in a grandiose ceremony at Versailles.1 When Bulgaria was established as a state in 1878, it was as a monarchy; the same was true of Norway, which voted to establish its own dynasty when it ended its union of crowns with Sweden in 1905.

The other great monarchies of Europe also survived the upheaval of the Napoleonic wars and the revolutions of 1830 and 1848 – although they reacted to the growing clamour for democracy in different ways. In Russia, the thirty-year reign of Catherine the Great, who came to the throne in 1762, had established the country as one of Europe’s great powers – but although she was influenced by the ideas of the Enlightenment, Catherine baulked at turning them into practice, especially after the French Revolution. Her successors followed varying courses: Nicholas I, tsar from 1825 until 1855, was one of the most reactionary of the Russian monarchs, earning the sobriquet of “gendarme of Europe” for the determination with which he suppressed revolution abroad. His son Alexander II by contrast was a reformer who emancipated the serfs, reformed the army and navy and introduced limited local self-government, and would have gone further had he not been assassinated in 1881.

The Austrian kaiser, Franz Joseph I, whose sixty-eight-year reign from 1848 remains the third longest of any European monarch,2 began by granting his people a constitution, but, after suppressing the Hungarian uprising with the help of Nicholas I, moved towards a policy of absolute centralism. Spain’s rulers too oscillated between reform and autocracy: Fernando VII ruled initially according to the liberal constitution of 1812, but later abolished it; his daughter, Isabel II, also often interfered in politics in a wayward, unscrupulous way that made her very unpopular – and led to her enforced exile in 1868.

And then there was Victoria, who ascended to the British throne in 1837 a few weeks after her eighteenth birthday and went on to reign for sixty-three years and seven months, longer than any British monarch before or since, and the most of any female ruler. Victoria’s reign witnessed considerable industrial, cultural, political, scientific and military progress; it also saw a doubling of the size of the British Empire, which by the time of her death in 1901 covered a fifth of the earth’s surface and was home to almost a quarter of the world’s population.

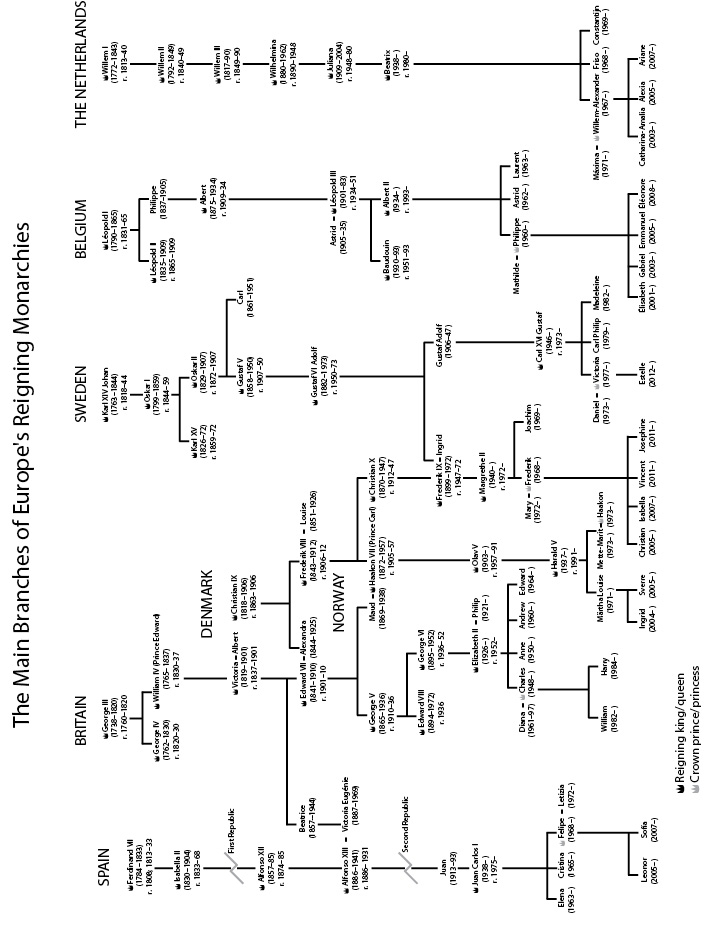

Victoria’s significance to the story of European monarchy derives also from the sheer number of her children – nine – and the energy she and Albert devoted to their marriages. Indeed, the majority of European monarchs and former monarchs today from Norway to Romania can trace their ancestry back to the royal pair.

The first years of the twentieth century were the high point of monarchy in Europe. With the exception of France – a republic again since Napoleon III’s defeat by the Prussians in 1870 – Switzerland and San Marino, every country was headed by a monarch. At King Edward VII’s funeral in May 1910 the procession included nine crowned heads and more than thirty royal princes.

Then, one by one, the monarchies began to fall, starting that October in Portugal: the young Manuel II, who had become king only two years earlier following the assassination of his father and elder brother, was ousted in a coup. Revolution claimed the throne – and then the life – of Nicholas II, the Russian tsar, executed with his family and their servants in a cellar in Yekaterinburg in 1918. Military defeat in the First World War led to the deposing of Wilhelm, the German kaiser, and Karl I of Austria, although both escaped with their lives.

The Second World War and its immediate aftermath also took its toll: in Italy, King Umberto II was forced from the throne after just thirty-four days following a referendum in June 1946 in favour of a republic. His father, Vittorio Emanuele III, discredited by his close relationship with Mussolini, had abdicated in favour of his son, but it was too late to save the house of Savoy. Umberto’s counterparts in central and eastern Europe fared no better. Stalin, whose Red Army now controlled the region, had no need for kings, and one by one, colourful King Zog of Albania, Miklós Horthy, who had ruled Hungary as regent, Petar II of Yugoslavia and King Mihai of Romania all departed the scene.

In Greece, where monarchy had been something of an on-off affair since Otto of Bavaria became king in 1832, a referendum in September 1946 confirmed royal rule, allowing Georgios II to return from exile. His nephew Konstantinos II was forced to flee in 1967, however, following an abortive counter-coup against the junta. Greece finally became a republic, apparently for good, after a plebiscite in December 1974. Spain bucked the republican trend: on 22nd November 1975, two days after the death of Francisco Franco, Juan Carlos, who had been prince of Spain since 1969, was designated king, according to the law of succession promulgated by the late dictator.

And so the royal map of Europe has stayed in the more than three decades since Juan Carlos’s inauguration: besides the Spanish monarchy, six other countries in Europe have kings or queens regnant: the United Kingdom, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden and Norway. Also with royal rulers are the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and the principalities of Liechtenstein and Monaco.3

Together, all ten nations – which are between them home to more than 150 million people4 – retain a political system in which the head of state owes his or her position to birth alone, and whose lifestyle, funded by the state, is way beyond the dreams of most of his or her subjects. Furthermore, these royal families enjoy a deference and degree of public interest that appear completely unrelated to their personal skills or accomplishments. And all this is at a time when in almost every other sphere of society the idea that someone’s lineage should guarantee them a lucrative job for life – especially one that still carries some vestige of political power – would be considered laughable.

It is the aim of this book to look at how this apparent anachronism has survived into the twenty-first century and to understand why these ten families have not been swept aside and replaced by elected heads of state. These are by no means Europe’s poorest or more backward countries. The Scandinavian nations, in particular, are some of the most egalitarian, not just on the Continent, but in the world. Nor are they politically conservative. Their democratic credentials are exemplary.

No one setting out to create a constitution from scratch today would seriously suggest such a system. Yet not only are such archaic arrangements tolerated, they are regularly supported by a clear majority of the countries’ respective parliaments and by their populations as a whole: call a referendum on the future of the monarchy in any of these ten nations today and you can be sure of a vote in favour of its retention. These, then, are the great survivors.

Attempting to explain this paradox requires a study of these royal families, of their history and of their present; of the gradual diminution of their political influence and of what remains of it; of their education and how their members are prepared for the top job; of their finances and their relationship with the media. And above all, it means examining Europe’s royals as ordinary people who are privileged – and sometimes, it seems, condemned – to play such an extraordinary role.