In the previous chapter, we laid out the inner “logic” of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), showing that its basic features were integral to the goal of providing health insurance coverage to all Americans. Once it was politically decided that new legislation would seek “universal coverage,” the dominoes began falling and it was necessary for the ACA to include related features such as “community rating” and an “individual mandate.”

Yet just because these related features were necessary, it doesn’t mean the laws of economics stop working. There are obvious and inevitable consequences flowing from each of these measures, which critics of the legislation warned about beforehand. In this chapter we’ll illustrate some of these fatal flaws of the ACA.

Even putting aside all of the pragmatic considerations, the very principle of government-guaranteed health insurance coverage is dubious. For one thing, it reinforces the confusion between health care and heath insurance, a conflation that itself is part of the problem. Beyond this quibble, the more fundamental flaw with the entire premise of the ACA is that it is not the federal government’s responsibility to provide health care to Americans.

The classical liberal conception of government—deriving from the political philosophy of writers such as Thomas Paine and extending up through the structure of the US Constitution—was a strictly limited institution that enforced “negative” rights. In this view, the purpose of government was to protect a sphere of autonomy for the individual within which he or she could operate, free from interference. The government, if it were to retain any legitimacy at all, could only exercise those powers that the people had the natural right to delegate in the first place. For example, individuals had the right of self-defense, and therefore they could collectively delegate the task of military defense to a government for pragmatic reasons.

This classical liberal approach is utterly incompatible with so-called positive rights. No individual has the natural right to force his neighbor to pay for his cancer treatments, and so by the same token (in the classical liberal view) it is illegitimate for a government to force some citizens to provide health care to others. Once the government goes down this path of “legalized plunder”—as the great nineteenth century polemicist Frédéric Bastiat described it—there is no end to the growth of a Nanny State that provides for its citizens from cradle to grave. In the race to the bottom that such a system entails, we arrive at another of Bastiat’s famous dictums: “The State is the great fictitious entity by which everyone seeks to live at the expense of everyone else.”1

To recoil from government-guaranteed universal coverage is not the same thing as opposing aid to the poor. Regarding medicine in particular, there was a long tradition for doctors and hospitals to provide care for the poor either at no charge or reduced prices. Furthermore, if Americans want to ensure that nobody dies on the street from lack of medical care, they can contribute to churches and/or secular charities that provide basic services for the truly needy. The objection that “the private sector lacks the resources” for such undertakings is unfounded: the government doesn’t have any resources—to fund the ACA, for example—that it doesn’t first take from the private sector. And to those who retort that “the free market was tried in health care and failed,” we remind you of everything we documented in Part I of the book: the United States government has been ramping up its interventions in the health care and health insurance markets since the early 1900s. What would US history need to look like for us to conclude that government intervention was tried in health care—and failed?

Just as the progressive left in general—and President Obama in particular—are associated with wealth redistribution, the ACA at its core rests on health redistribution. That is, the very nature of the ACA seeks to erase genuine differences among the health status of individuals, and tries to force the entire health care system to treat people as if they were all “equals” in this dimension. As with economics, so with health: pretending people are the same, when in fact they are vastly different, is inherently unfair and produces undesirable consequences.

The most obvious manifestation of the ACA’s reliance on health redistribution is the so-called “community rating” principle, by which the government forces health insurance companies to charge different applicants the same price for the same policy. Currently, the only four types of (limited) exceptions are pricing differentials based on age, geography, smoking status, and family size (for family versus individual plans).2 Even here, there are limits on pricing flexibility: insurers can only charge a maximum of three times as much to older applicants as to younger ones, and they can only charge a smoker a maximum of 50 percent more for the same policy offered to a nonsmoker of the same age.

The unfairness of (mandatory) community rating is that it implicitly forces the healthy and young to subsidize the sick and the old. The point is obvious enough when it comes to people with pre-existing conditions that require expensive treatment; forcing insurers to offer coverage to a 45-year-old with a serious heart condition—while only charging the same price as they must charge all healthy 45-year-olds— clearly implies a subsidy to the heart patient and a “tax” on the healthy members of the pool.

A similar principle holds for the constraint placed on pricing differences between young and old. To repeat, the ACA only allows insurers to charge a maximum of three times as much on policies issued to older applicants versus those issued on younger ones. This too sets up an implicit subsidy, because pre-ACA, the industry norm was closer to a 5-to-1 gap. Thus, once health insurers adjust their overall premium structures in light of the new constraint, premiums for younger applicants will be higher than they otherwise would have been, while premiums for older applicants will be lower than they otherwise would have been. To illustrate the size of this effect, a 2013 study estimated that if the ACA allowed a range of 5-to-1 (rather than the actual limit of 3-to-1) in policy premiums according to age, then premiums for 21-to 27-year-olds would fall by $850 per year, while premiums for applicants aged 57 to 64 would be $1,770 higher.3 Going the other way, then, the fact that the ACA does not allow a 5-to-1 range, but instead mandates a narrower 3-to-1 range, means that the younger group is charged $850 more (before considering government assistance), while the older group enjoys premiums that are $1,770 lower.

Besides the unfairness of the implicit “tax” and “subsidy” scheme involved, the principle of community rating also leads to undesirable consequences. For example, moral hazard refers to the problem of individuals taking bigger risks because of faulty incentives. In the context of auto insurance, the principle of moral hazard refers to the possibility that a motorist will not drive as carefully if he knows he will be indemnified for any damage to his vehicle. Obviously, the point isn’t that people with auto insurance go out and intentionally get in car accidents, but that they tend to drive a bit more recklessly—perhaps going slightly faster, or fiddling with the radio just a little bit longer—than if they had no auto insurance and had to bear the full cost of any vehicle damage out of pocket.

In the context of health insurance—particularly when the highest premiums are being artificially suppressed—the principle of moral hazard asserts itself when individuals engage in riskier behavior that could cause health problems. By limiting the ability of insurers to charge higher premiums for higher-risk clients—including conditions that are exacerbated by lifestyle choices—the ACA fosters poorer diet and exercise decisions in the aggregate.

“I’m not doing much, how ‘bout you?”

Besides moral hazard, economists also warn that improper pricing in insurance markets can lead to adverse selection. In our context, the problem is that community rating may induce young and healthy people to drop out of the insurance market altogether, raising the average health care costs of the people remaining in the pool. Depending on the numbers, this process in theory could lead to a “death spiral” in which the premiums rise so much that only the very sick remain to apply for health insurance, causing private-sector health insurance to become unviable: no insurance company can stay in business if all of its clients have serious conditions. Adverse selection shows that the principle of “community rating” isn’t just a zero-sum game—in which the government forces young and healthy people to implicitly subsidize the older and sick—but is actually a negative-sum game, chasing some people out of the market altogether and leaving the remainder worse off.

The problem of adverse selection is partially addressed by the ACA’s individual mandate, but as of this writing, it is still an open question whether the escalating fines will be high enough to induce enough young people to obtain health insurance, particularly as the full brunt of the ACA has yet to be implemented.

One of the biggest PR disasters associated with the Affordable Care Act was President Obama’s broken pledge that “you can keep your plan,” which won PolitiFact’s “Lie of the Year” award in 2013. To understand just how duplicitous President Obama and his subordinates were, it’s worth quoting from PolitiFact’s explanation of the award:

It was a catchy political pitch and a chance to calm nerves about his dramatic and complicated plan to bring historic change to America’s health insurance system.

“If you like your health care plan, you can keep it,” President Barack Obama said—many times—of his landmark new law.

But the promise was impossible to keep.

So this fall, as cancellation letters were going out to approximately 4 million Americans, the public realized Obama’s breezy assurances were wrong. …

For all of these reasons, PolitiFact has named “If you like your health care plan, you can keep it,” the Lie of the Year for 2013. …

The Affordable Care Act tried to allow existing health plans to continue under a complicated process called “grandfathering,” which basically said insurance companies could keep selling [pre-ACA] plans if they followed certain rules.

The problem for insurers was that the Obamacare rules were strict. If the plans deviated even a little, they would lose their grandfathered status. In practice, that meant insurers canceled plans that didn’t meet new standards.

Obama’s team seemed to understand that likelihood. US Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius announced the grandfathering rules in June 2010 and acknowledged that some plans would go away. Yet Obama repeated “if you like your health care plan, you can keep it” when seeking re-election [in 2012]. …

But what really set everyone off was when Obama tried to rewrite his slogan, telling political supporters on Nov. 4, “Now, if you have or had one of these plans before the Affordable Care Act came into law, and you really liked that plan, what we said was you can keep it if it hasn’t changed since the law passed.”

Pants on Fire! PolitiFact counted 37 times when he’d included no caveats, such as a high-profile speech to the American Medical Association in 2009: “If you like your health care plan, you’ll be able to keep your health care plan, period. No one will take it away, no matter what.”4

The reason the ACA led to the cancellation of so many previously issued health insurance policies is that they were deemed too stingy. In particular, millions of people who bought their own insurance (perhaps because they were self-employed) would opt for “catastrophic” plans with high deductibles that didn’t include dental or vision benefits.

Such plans are illegal under the ACA.5 As the government’s website explains:

The Affordable Care Act ensures health plans offered in the individual and small group markets … offer a comprehensive package of items and services, known as essential health benefits. Essential health benefits must include items and services within at least the following 10 categories: ambulatory patient services; emergency services; hospitalization; maternity and newborn care; mental health and substance use disorder services, including behavioral health treatment; prescription drugs; rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices; laboratory services; preventive and wellness services and chronic disease management; and pediatric services, including oral and vision care.6

The requirement of these “essential” benefits leads to absurdities such as men and post-menopausal women being forced to buy insurance plans that cover maternity leave. This is another example of the health redistribution that characterizes the ACA; policyholders who obviously won’t be receiving reimbursements for maternity care are implicitly subsidizing women who (in a free market) would have chosen plans with such coverage.

Beyond the silliness and the unfairness, the requirement of essential health benefits also creates moral hazards. For example, we have to ask why many health insurance plans had such high deductibles, co-payments, and other “undesirable” features before passage of the ACA. One reason, of course, is that this limited the payments that the insurance company had to make for a given procedure, but this structure also provided the critical feature of making people more conscious of their health care decisions. Someone with a catastrophic insurance plan that had, say, a $10,000 annual deductible, high co-payments for routine care, and no dental or vision benefits, is typically going to consume a lot less in total “health care services” per year than someone with a much smaller deductible, no co-payments for preventive services, and full vision. Thus, by making such catastrophic plans illegal, the ACA ironically destroys some of the checks on excessive health care spending that the system previously had.

In the previous chapter, we explained why the logic of the ACA required an individual mandate, in which everyone (with some exceptions) is legally required to buy health insurance. Yet even though there is a perverse “logic” to the mandate, it nonetheless should offend anyone who believes in a limited role for the State. If Thomas Jefferson or James Madison were transported to our times, they would presumably be fascinated by the Internet and space travel, but they would also be shocked to learn that the US government was now forcing every citizen to buy health insurance.

IS THE INDIVIDUAL MANDATE A TAX? DEPENDS ON WHO’S ASKING

The only way the Supreme Court could even pretend to reconcile the ACA’s individual mandate with the US Constitution was by treating it as a tax (conditional on whether the taxpayer happened to have health insurance for the tax year in question).7 Conservative critics of the ACA had a field day with the Court ruling, because proponents of the legislation—including President Obama himself—had assured Americans that the individual mandate involved a penalty, not a tax.

Beyond the abstract affront to liberty is the fact that the individual mandate fines people who consider health insurance too expensive. Remember, the penalties on individuals who commit the sin of failing to purchase health insurance become quite steep: by 2016, the penalty for an individual is 2.5 percent of income or $695 per person, whichever is more.

Now the defender of the ACA might retort that such a stiff penalty is largely for show, a mere formality as it were, because the Affordable Care Act will provide good options for every American, such that very few people in practice will actually pay that stiff fine.

Alas, that’s not what the federal government itself thinks about the matter.

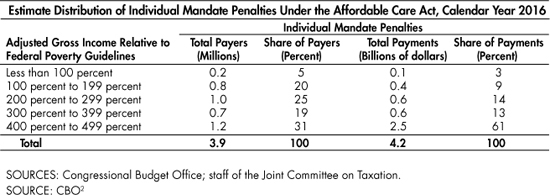

Table 6-1. CBO Estimate of 2016 Individual Mandate Penalties Under ACA

As Table 6-1 indicates, the CBO’s latest estimate (as of this writing) projects that when the ACA’s individual mandate reaches its maximum level in 2016, there still will be 3.9 million Americans who actually pay the fine. (More people will technically owe the fine—because they lack health insurance and are not exempt from the mandate—but simply will not pay it.) These 3.9 million Americans will pay a total of $4.2 billion to the IRS for the calendar year 2016 alone, meaning they will prefer to pay more than $1,000 on average to not obtain health insurance—which makes us wonder just how “affordable” it will be.

Finally, note that Table 6-1 shows that these fines are not restricted to the affluent. The CBO estimates that 200,000 people with an income below the federal poverty line will be assessed the penalty, along with an additional 800,000 people who make less than twice the poverty line.8 For these one million people, the Affordable Care Act—according to the government’s own projections—will be doing the exact opposite of what its supporters believe: these are low-income people who still will lack health insurance, and on top of that will pay an additional fine (of at least $695 for adults) to the IRS.

As we explained in the previous chapter, there are various subsidies embedded within the ACA in order to (ostensibly) make insurance affordable. Yet along with adding more than a trillion dollars in federal spending over its first decade—spending that US taxpayers ultimately must finance—the ACA’s subsidies will lead to millions more Americans who are utterly dependent on the government for health care. Furthermore, these subsidies will distort work incentives to a degree that may surprise even some of the ACA’s critics.

Before relaying the size estimates of this effect on work incentives, we should spend a moment to explain how it works. Most people intuitively understand that if the government levies a high tax rate on additional income, then it reduces the incentive for people to work more to earn it. For an exaggerated example, if the government taxed income up to $100,000 at 10 percent, but then taxed income above $100,000 at 99 percent, then someone who originally made $90,000 probably wouldn’t take a promotion to a more stressful and time-demanding position even if it paid double. That’s because most of the big jump in the (pre-tax) salary would end up going into the coffers of the IRS.

There is a similar mechanism at work, but in reverse, when it comes to government subsidies (in the form of refundable tax credits, for example) at the low end of the income scale. Again, this effect is easiest to see if we use an exaggerated numerical example. Suppose the government pays for $5,000 in health insurance premiums for an individual who makes $15,000 or less in annual income, but gives zero in subsidies to anyone who makes above $15,000. Now suppose an individual starts out working part-time earning $12,000 annually, paying for his own health insurance through a government exchange and enjoying the full subsidy. Then the individual gets an offer to take a full-time position that pays $16,000 in salary, but at a small company that will not provide health insurance. It’s obvious with our exaggerated numbers that it would be foolish for the man to take the new job and work more hours, because the $4,000 increase in earnings would be more than offset by the loss of the $5,000 subsidy for health insurance. Thus, in this case, our hypothetical individual would perversely be “trapped” working part-time because moderate improvements in his employment status would actually make him worse off financially—unless of course he took the pay raise and dropped his health coverage.

To be clear, this example uses the rule of a stark cutoff in a generous subsidy for health coverage above a particular income threshold; the actual subsidy structures in the ACA are more complex. Nonetheless, the obvious disincentive effect in our simple thought experiment translates to the real-world impact of the ACA: because it offers so many “generous” subsidies for health insurance coverage tied to income level, the ACA reduces the incentive for low-income workers to earn more money.

In its February 2014 updated forecast, the CBO shocked the pundits by more than doubling its estimate of the job reduction due to the ACA. Here is how the CBO report explained its new projections:

CBO estimates that the ACA will reduce the total number of hours worked, on net, by about 1.5 percent to 2.0 percent during the period from 2017 to 2024, almost entirely because workers will choose to supply less labor—given the new taxes and other incentives they will face and the financial benefits some will receive…. [T]he largest declines in labor supply will probably occur among lower-wage workers….

The reduction in CBO’s projections of hours worked represents a decline in the number of full-time-equivalent workers of about 2.0 million in 2017, rising to about 2.5 million in 2024.9

To repeat, this new projection (made in February 2014) of two million fewer “full-time equivalent” jobs10 by 2017 was more than double the original figure of a “job cost” of 800,000 from the legislation. Most of the jump was due to the CBO’s revised modeling of the disincentive effects of the ACA’s subsidies on lower-income workers. When the news of the updated CBO estimate broke, naturally the critics of the ACA had a field day, saying “I told you so” about the devastating impact the big-government plan would have on the economy.

What was surprising, however, was how the defenders of the Obama Administration tried to spin the higher estimates of labor force reduction as a good thing, at least for the workers in question, who now could spend more time with their family or pursue other vocations because of the new options that the ACA provided to them. For example, here’s how Paul Krugman tried to do damage control from his blogging perch at the New York Times:

So the CBO estimates that the incentive effects of the ACA will lead to a voluntary reduction in labor supply of around 1 1/2 percent, the equivalent of 2 million full-time jobs….

[The implied drop in the size of potential economic output is] a clear overstatement of the true economic costs of the program.

Why? Because when workers voluntarily withdraw 1 percent of their hours, it’s very different from what happens when 1 percent of workers lose their jobs and become involuntarily unemployed.

When workers lose their jobs, it’s almost always a terrible experience: not only does it cause financial hardship, it eats away at the soul….

When workers choose to work less, by contrast, they presumably do so because they gain something that is, to them, worth more than the foregone income: more time with their children, an earlier retirement, etc. Now, in making these choices they won’t take into account the spillovers to the rest of society that come from their paying less in taxes or receiving more in benefits; so you probably don’t want to think of the reduction in labor supply as a net economic good. But it’s surely a smaller cost than the headline effect on GDP.11

We have selected Krugman’s attempt at damage control because he— as a Nobel Prize-winning economist—gave the CBO bombshell the most adequate pushback possible. In addition to Krugman’s nuanced defense, there were plenty of lesser pundits and Obama spokespeople who were uttering abject nonsense, trying to convince gullible Americans that the news was somehow another feather in the cap of the new legislation and that the long-run reduction in the workforce of 2 percent was actually a good thing for the country.

These attempted spins of the CBO’s bombshell fail. First let’s explain what’s wrong—or at least very misleading—about the argument that these worker withdrawals from the labor force are “voluntary” and hence must be good, at least for the low-income workers in question.

The crucial fallacy here, as economist David R. Henderson pointed out when the CBO story broke,12 is to focus only on the subsidies for low-income people in the ACA, while ignoring the individual mandate and other restrictions. Krugman and other apologists were correct in saying that the subsidies gave options to low-income workers and thus were good compared to the rest of the ACA without any subsidies, but that’s an entirely different claim from saying the ACA as a whole package helped low-income workers compared to the situation without the ACA at all.

Henderson clarified the point with an analogy about cars, which we’ll slightly adapt here. Suppose the government forced every citizen to buy a new car with a price tag of $15,000, but recognizing that this would be a large burden to some citizens, the government simultaneously offered to pay the full cost of the new car for anybody making less than the federal poverty line. We can easily imagine in this (contrived) scenario that there would be hundreds of thousands of Americans who originally worked at jobs that paid a little bit above the poverty line, and who drove a beat-up old car or perhaps took the bus. Then, facing the new situation of being mandated to buy a new $15,000 car and having a full subsidy conditional on being in poverty, these hundreds of thousands of low-income workers could quite rationally choose to cut back their hours in order to reduce their income and hence qualify for the subsidy. When the dust settled, these low-income workers would be driving a new car and earning below the poverty line, rather than the original scenario of taking the bus and making an income above the poverty line. It’s not obvious that every single one of these hypothetical workers would be better off in the new scenario, even though their narrow choice of choosing to reduce their hours was “voluntary.” Some probably would be quite happy with the new arrangement, but we can easily imagine that others would be miserable—for example, a guy who used to drive a beat-up car but worked at a job that placed him $8,000 above the poverty line.

In his article, Henderson pointed out that the situation facing low-income workers after passage of the ACA parallels our hypothetical car scenario. Workers who originally chose not to carry insurance (because it was too expensive), or who had catastrophic plans with no bells and whistles, are now being forced by the ACA to buy plans that are far more expensive than what they would have chosen on their own. In order to receive means-tested federal subsidies to pay for these expensive (and mandatory) policies, some low-income workers are now “voluntarily” reducing how much they work and earn. As in our hypothetical car scenario, here too we can admit that some low-income workers may prefer the new arrangement, but many may have preferred the pre-ACA status quo—when they worked more hours to earn a higher income, and had the option of buying a cheaper, no-frills health insurance policy or even to go without health insurance at all.

So we see that, arguments over “voluntary” work reductions notwithstanding, it’s unclear how many recipients of these subsidies are actually better off after passage of the ACA. But besides these technical quibbles, there is the overarching absurdity in the debate that none of the ACA’s champions ever mentioned the big drop in the workforce before the legislation was passed. All of these problems surfaced only after the ACA had become law.

This point was made in biting fashion by Casey Mulligan, a Chicago School economist whose work on the disincentive effects contained in the ACA was one of the chief reasons that the CBO changed its forecast. After the CBO bombshell, and the ensuing efforts at damage control by the Obama Administration and its allies, the Wall Street Journal interviewed Mulligan and asked for his reaction to this development in the policy debate:

A job, Mr. Mulligan explains, “is a transaction between buyers and sellers. When a transaction doesn’t happen, it doesn’t happen. We know that it doesn’t matter on which side of the market you put the disincentives, the results are the same…. In this case you’re putting an implicit tax on work for households, and employers aren’t willing to compensate the households enough so they’ll still work.” Jobs can be destroyed by sellers (workers) as much as buyers (businesses).

He adds: “I can understand something like cigarettes and people believe that there’s too much smoking, so we put a tax on cigarettes, so people smoke less, and we say that’s a good thing. OK. But are we saying we were working too much before? Is that the new argument? I mean make up your mind. We’ve been complaining for six years now that there’s not enough work being done…. Even before the recession there was too little work in the economy. Now all of a sudden we wake up and say we’re glad that people are working less? We’re pursuing our dreams?”

The larger betrayal, Mr. Mulligan argues, is that the same economists now praising the great shrinking workforce used to claim that ObamaCare would expand the labor market.

He points to a 2011 letter … signed by dozens of left-leaning economists including Nobel laureates, stating “our strong conclusion” that ObamaCare will strengthen the economy and create 250,000 to 400,000 jobs annually….

“Why didn’t they say, no, we didn’t mean the labor market’s going to get bigger. We mean it’s going to get smaller in a good way,” Mr. Mulligan wonders. [Bold added.]13

In summary, the ACA’s enormous subsidies to defray the cost of health insurance for low-income Americans are problematic not only because they involve a redistribution from the taxpayers, but also because they reduce the incentive to work. This is not a controversial point; even the ACA’s staunchest defenders, such as economics Nobel laureate Paul Krugman, admit it—though it would have been nice if they had admitted it before the ACA was passed into law.

In the previous chapter, we explained that the ACA was estimated to carry with it some trillion dollars in net tax revenue increases over the first decade. The defenders of the legislation of course portray this as mere nibbling at the crumbs falling from the tables of the super rich. For example, Paul Krugman—in a post ironically titled “Beyond the Lies”—described the redistribution in the ACA in this way:

[T]he attack on Obamacare depended almost entirely on lies, and those lies are becoming unsustainable now that the law is actually working. No, there aren’t any death panels; no, huge numbers of Americans aren’t losing coverage or finding their health costs soaring; no, jobs aren’t being killed in vast numbers. A few relatively affluent, healthy people are paying more for coverage; a few high-income taxpayers are paying more in taxes; a much larger number of Americans are getting coverage that was previously unavailable and/or unaffordable; and most people are seeing no difference at all, except that they no longer have to fear what happens if they lose their current coverage.14

Needless to say, Krugman’s description stretches the truth to a degree that would impress a yoga instructor. When Krugman says “a few high-income taxpayers are paying more in taxes,” he presumably is referring to the individuals making above $200,000 (and married couples more than $250,000) who now pay an additional 0.9 percent on the Medicare payroll tax as well as a very misleadingly named “Medicare” surtax of 3.8 percent on investment income. Far from being “a few” people, IRS data indicate that (in 2012) there were more than 5.2 million taxable returns with adjusted gross income higher than $200,000.15 Furthermore, Krugman’s breezy discussion completely ignores the one million Americans making less than double the federal poverty line, whom the CBO anticipates will pay a fine for not having health insurance in 2016.16

Yet there is a far more insidious problem with the ACA’s new revenue streams, of which even the fiercest critics of the Obama Administration seem unaware. Although the explicit tax rate increases embedded in the ACA legislation are indeed limited to “the rich,” nonetheless hundreds of billions of dollars in extra revenue are projected to occur from the ACA’s effects working through the pre-existing tax code.

What can happen is this: through various mechanisms, the ACA will cause some employers to reduce the quality (and expense) of the insurance plan they provide to their employees (particularly because of the 40 percent excise tax on so-called “Cadillac” plans), and it will cause some employers who are currently offering health insurance to simply abandon the practice altogether, so that their employees obtain insurance themselves—perhaps through the government exchanges. This change won’t translate to a complete loss for the workers involved; the force of competition in the labor market will lead the employers to offer higher wages in lieu of paying for health insurance. However, under the current tax code, when an employer spends money on health insurance premiums for an employee, that is not taxable income for the employee. But if the employer reduces (or eliminates altogether) spending on the employee’s insurance, and increases monetary compensation instead, then the extra wages are taxable income. Therefore, even though the ACA doesn’t contain explicit income tax rate hikes for all workers, the government nonetheless anticipates that it will derive large revenues from all types of workers, not just “the rich.”

To get a sense of just how big this effect may be, let us quote from the CBO’s April 2014 updated estimates. In the excerpts that follow, note that the CBO breaks up the effect as due to the so-called tax on “Cadillac” plans specifically, versus the more miscellaneous effect resulting from the rest of the ACA’s provisions:

According to CBO and JCT’s [Joint Committee on Taxation] estimates, federal revenues will increase by $120 billion over the 2015–2024 period because of the excise tax on high-premium insurance plans. Roughly one-quarter of that increase stems from excise tax receipts, and roughly three-quarters is from the effects on revenues of changes in employees’ taxable compensation…. In particular, CBO and JCT anticipate that many employers and workers will shift to health plans with premiums that are below the specified thresholds to avoid paying the tax, resulting generally in higher taxable wages for affected workers. …

The ACA also will affect federal tax revenues because fewer people will have employment-based health insurance and thus more of their income will take the form of taxable wages. CBO and JCT project that, as a result of the ACA, between 7 million and 8 million fewer people will have employment-based insurance each year from 2016 through 2024 than would have been the case in the absence of the ACA… ….

Because of the net reduction in employment-based coverage, the share of workers’ pay that takes the form of nontaxable benefits (such as health insurance premiums) will be smaller—and the share that takes the form of taxable wages will be larger—than would otherwise have been the case. That shift in compensation will boost federal tax receipts. Partially offsetting those added receipts will be an estimated $7 billion increase in Social Security benefits that will arise from the higher wages paid to workers. All told, CBO and JCT project, those effects will reduce federal budget deficits by $152 billion over the 2015–2024 period. [Bold added.]17

According to these estimates, the ACA will yield the government some $240 billion in extra tax receipts over a ten-year period paid by workers because their compensation packages will reduce or eliminate health coverage and will increase wage or salary.

To reiterate, these modeling effects and revenue estimates aren’t coming from the Heritage Foundation or another group hostile to the Obama Administration. On the contrary, these figures come from the Congressional Budget Office, and indeed form about one-quarter of the means by which the ACA “pays for itself.” Yet we sure don’t remember any of its cheerleaders stressing these particular effects when they proudly announced the CBO’s verdict that the ACA would “reduce the deficit.”

In the previous chapter, we outlined some of the major provisions through which the government shared the risk with the health insurance companies for policies issued during the first few years of the new ACA regime. This aspect of the new legislation is dangerous for a few reasons.

In the first place, as with every other element of the ACA, it violates the principle of limited government. Just as the federal authorities have no business ordering citizens to buy health insurance, Uncle Sam shouldn’t act as a giant reinsurer for the major health insurance companies, putting taxpayers on the hook in case the claims come in higher than expected.

There is also the serious matter of corruption. With many billions of dollars flowing around, surely decisions have been and will continue to be made behind closed doors that have little to do with providing quality care to the poor. Indeed, many progressive voters—who initially had such high hopes for the new President—became disillusioned at the backroom dealing that characterized the drafting of the ACA itself, rather than the “most transparent Administration in history” that Senator Obama had promised on the campaign trail.

Finally, the hidden taxpayer bailouts of the health insurance companies serve to mask the true economic distortions of the Affordable Care Act—a topic we will explore more fully in the next section. Simply put, if the federal government had not stepped in as a “backstop” to the health insurers for (at least) the transition period as the ACA’s provisions were phased in, then some of the insurance companies may have exited the market altogether, or at least increased their premiums more aggressively in response to the legislation.

For example, the CBO estimated that “reinsurance payments scheduled for insurance provided in 2014 are large enough to have reduced exchange premiums this year by approximately 10 percent relative to what they would have been without the program”.18 By transferring some of the actual cost of the ACA away from the health insurance companies (and their customers) to the taxpayers in the first few years, the hidden bailouts will make it harder for the voters to diagnose what’s happening. In particular, had premiums increased to fully reflect the new legislation in 2014 when the individual mandate went into effect, more Americans would have realized just how burdensome the ACA would prove to be. As it is, the defenders of the ACA are running victory laps over how “surprisingly affordable” the exchange-provided policies are.

As we have seen, various measures of the ACA will ultimately cause employers to reduce the health insurance coverage they offer to their employees, with some seven to eight million fewer workers having employer-provided coverage through 2024, according to a CBO estimate.19 Yet as we explained in the previous chapter, the architects of the ACA wanted to minimize the number of employees who were kicked off of their employers’ plans, for obvious political reasons. Therefore, the ACA contains an “employer mandate,” with stiff fines for certain employers who choose not to offer coverage for full-time employees.

To review from our last chapter: the ACA mandates that large employers—defined as those who have 50 or more “full time equivalent” employees, where “full time” is defined as working 30 or more hours in a week—provide a qualifying health insurance plan to their full-time employees. If the employer does not provide a qualifying health insurance plan to a given full-time employee, then the employer owes the IRS an annualized fine of either $2,000 or $3,000 for each such employee.20

These fines for employers are quite hefty. If the health insurance provided by the ACA were indeed “affordable,” one would expect that relatively few employers would decide to deny coverage and pay the fine. Yet as with the individual mandate, here too it will be very instructive to look at the government’s own estimates of how many employers will in fact choose to pay either a $2,000 or $3,000 fine per applicable employee, rather than paying for the “affordable” coverage.

Specifically, the latest CBO report estimates that from 2015 through 2024, employers will pay $139 billion in penalty payments to the government for failing to provide their employees with qualifying health insurance. As with the other revenue streams, it is once again worth noting that this is yet another large chunk of the roughly trillion dollars necessary for the ACA to “pay for itself,” and yet is not what most Americans probably have in mind when chalking up the needed revenue to “tax hikes on the rich.”

It is worth dwelling on this astounding figure to grasp its full significance. When the government expects employers to decide it is more profitable to pay either a $2,000 or $3,000 fine and not offer health insurance to millions of their employees, this is very revealing as to how expensive these plans will be. The comparison is not “pay $2,000 as a fine, or pay a little more for health insurance for my employee.” When an employer pays a fine to the government, that payment in no way benefits the employee who isn’t being offered health insurance. In contrast, if an employer does spend, say, $5,000 on a health insurance policy, then that expenditure makes the position more desirable and can attract a higher quality candidate.

Therefore, in the same way that it should be shocking that millions of Americans will choose to pay a stiff fine and not have health insurance, it is also shocking that many employers will pay large fines and not include health insurance as part of their compensation packages for millions of employees. If these projections were coming from scholars who had a political ax to grind, they might be dismissed as paranoid criticisms of Obama. But to repeat, these projections come from the government’s own estimates of how much revenue the ACA will bring in.

“Sorry, but it’s cheaper for us to pay a $3,000 fine for each of you than to give you adequate health insurance. But we have free donuts every Friday!”

Besides the tax hike on employers, the employer mandate has another perverse effect: it provides a very large incentive for small firms to remain small, and for large firms to keep their workers part-time rather than full-time. These observations don’t require a PhD in economics; the employer mandate only applies to firms with 50 or more full-time equivalent employees, and even for those employers, the fine is only applied for full-time employees.21

A naïve inspection of the employment data certainly seems to confirm the worst fears about this consequence of the mandate, because the proportion of part-time workers in the overall labor force has indeed risen dramatically with passage of the ACA. However, it is difficult to disentangle the effect of the ACA itself from the deep recession that began in late 2007. (It is normal for part-time employment to rise during recessions, as employers do not wish to commit themselves to the bigger responsibility of hiring a full-time worker.) On the other hand, the employer mandate aspect of the ACA has been pushed back at least twice due to complaints from business that the requirement is too onerous to be implemented while the economy is still weak. (Even major labor leaders sent an open letter to Democratic leaders warning that the ACA as originally passed could “destroy the foundation of the 40-hour work week that is the backbone of the middle class.”22) It’s therefore likely that the employer mandate’s full effect on part-time versus full-time employment has not yet manifested itself.

In the previous chapter, we showed that by its very nature, the government’s desire to legislate universal health insurance coverage also required several other interventions, including community rating, essential health benefits, an individual mandate, government subsidies for the poor, tax hikes (especially on “the rich”), government guarantees for the health insurers, and an employer mandate.

In this chapter, we showed that each component of these additional (yet necessary) features of the Affordable Care Act carries its own specific and undesirable consequences. The combination of universal coverage, community rating, and essential health benefits will yield a massive health redistribution by which the young and healthy implicitly subsidize the old and those using extensive care. This arrangement distorts incentives in the market for health insurance, weakening the motivation for people to monitor their health care expenditures and reducing personal financial consequences of health conditions that are not merely the result of genetics or uncontrollable circumstances, but can be influenced through lifestyle choices. Furthermore, by “over-charging” the healthy and frugal while “undercharging” those responsible for most of the health care spending, the framework also encourages relatively healthy individuals to drop out of the insurance pool altogether, raising premiums for those who remain.

The individual mandate adds insult to injury for what may be millions of Americans who will still lack health insurance but will pay stiff penalties on top of it, along with those who obtain coverage but will be forced to buy more expensive policies than they would have voluntarily selected. The combination of massive subsidies for low-income individuals to receive coverage, higher tax rates, and the employer mandate will—among other things—grossly distort the labor market. These influences lead to a “voluntary” reduction in labor effort, both by the relatively poor in order to qualify for the subsidies and by the relatively affluent to minimize their tax liability, as well as an effort of employers to substitute part-time workers for full-time. Finally, the hidden government bailouts for the health insurance companies will foster corruption and mask the true economic impact of the ACA for several years, making repeal that much more difficult.

“Get ready!

The next wave of legislation is rolling in.”