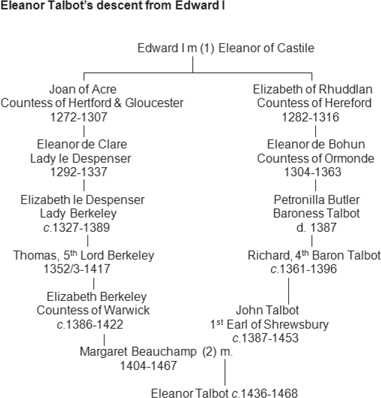

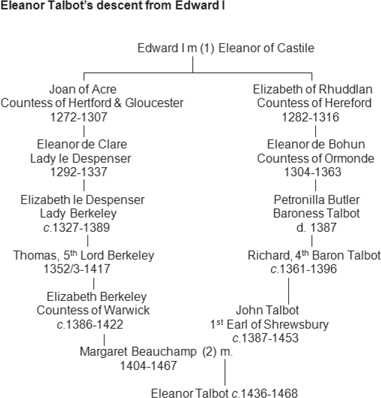

Eleanor Talbot’s two lines of descent from King Edward I and Eleanor of Castile.

At 38 years of age, Eleanor’s mother, Lady Margaret Beauchamp, was a good deal younger than her husband. Although she was unable to travel the world making war as he did, Margaret was also, in her own way, a great fighter. Her character and determination were a match for John’s. Their partnership, which has been described, possibly with justification, as a love-match,1 had proved harmonious and conspicuously successful. This may have been due in no small part to John’s prolonged absences abroad and to the fact that Margaret had, in consequence, enjoyed considerable freedom to order her own household for the greater part of her married life. Her husband evidently trusted her completely.

Margaret was clearly able and highly intelligent. She was also unmistakably a woman of action and capable of remarkable ruthlessness when she felt the occasion demanded. Despite being a woman, Margaret did travel a good deal. It is possible that she visited her husband in Normandy in April of 1441 – when a papal indult, allowing them to have mass celebrated at a portable altar in an area which lay under interdict, was addressed to them jointly there.2 The mention of Margaret’s name in this indult may, however, have been contingency planning or papal politeness. It does not necessarily prove that Margaret had crossed the Channel at that time, although she certainly did so on one later occasion.

Eleanor Talbot’s two lines of descent from King Edward I and Eleanor of Castile.

Ironic fortune, having apparently dealt Margaret an excellent opening hand of cards, had, nevertheless, negated many of her potential advantages by secretly distributing trumps to her rivals. As his eldest child, Margaret had long expected to be the senior coheiress of her father, Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, but finally his second wife, Isabel Despenser, gave him a son. Then, through her mother, Margaret had a clear claim to the honours of Berkeley and Lisle. However, her mother’s cousin, James, had laid claim to this inheritance and secured the greater part of it. Finally, Margaret had been favoured with a flourishing family of healthy children, whom she would naturally have wished to see as their father’s heirs. Maud Neville, however, had pre-empted her, producing a senior brood who would now keep Margaret’s offspring from the Talbot inheritance. Undeterred by these shabby tricks of fortune’s wheel, Margaret nevertheless fought to make the best of things for her children.

Like most of the English aristocracy, Lord and Lady Talbot were distantly related to one another. For example, they were both descendants of King Edward I. Their relationship, however, was sufficiently remote that in their case no papal dispensation was necessary before they could marry. Their patently successful union had been crowned with a brood of promising and healthy children, who seem to have been born at irregular intervals as a result of John’s periodic home leave. So far the couple had three sons and one daughter. This second Talbot family closely paralleled the one produced for John by his first wife. Maud Neville had given her husband three sons (Thomas, John and Christopher) and probably two daughters (one whose name is unknown to us, and Joan). However, Maud’s brood had dwindled. Thomas, born in Dublin in 1416, had died at the age of 6 weeks, and the nameless daughter had died not long after the death of her mother, in 1424.3 On the other hand all Margaret’s children had so far survived.

Her eldest son, John Talbot III, had been born in 1426. The influence of his father’s campaigning in France could be seen in the naming of their second son, Louis, born two years later. There had then followed a gap of several childless years, because Lord Talbot had been a prisoner of the French. Not until 1433 had he been available to father another child. Humphrey had duly made his appearance in the following year. As we have seen, he was probably named after the king’s uncle, the Duke of Gloucester, who may have been his godfather. At about the time of Humphrey’s birth, Margaret found herself for the first time raised to the rank of countess. On the vigil of the feast of St Louis (24 August) the Duke of Bedford, regent of France, had created her husband Count of Clermont.

A brief visit to England by the new count, in the summer of 1435, seems to have resulted in the birth of Eleanor, Margaret’s only daughter so far. The relationship between female members of aristocratic families in the fifteenth century was often particularly close, so that for Margaret, the birth of this first daughter may have been quite a special event.4 Margaret herself enjoyed a close relationship with her own sisters, and it is evident that she also maintained very close ties with all her children. Later the children – and especially Margaret’s two daughters – were also to keep up close links with one another.

The name selected for the little daughter of John Talbot and Margaret Beauchamp, Earl and Countess of Clermont, in itself marks the closeness of the family ties, for it was almost certainly chosen in honour of her aunt, the elder of Margaret’s two full-blood sisters. She was Lady Eleanor Beauchamp. Formerly she had been Lady Ros (Roos). However, her first husband had died, and she was currently the wife of the Earl of Somerset’s younger brother (and eventual successor), Edmund Beaufort, Count of Mortain. This aunt (who was herself pregnant at the time of Eleanor’s birth) might perhaps have become one of little Eleanor’s two godmothers. About three months later, aunt Eleanor in turn gave birth to a child of her own – her first son by her second husband. This baby boy was little Eleanor’s cousin, Henry Beaufort. He was later to become the heir to the Duchy of Somerset. Curiously, this little boy who had followed Eleanor into the world was also to follow her later in another way, when they were both grown up. Both he and Eleanor are reported to have had relationships with King Edward IV (see Chapter 13).

Herself the first child of her parents’ marriage, Margaret had been born in 1404, when her mother, Elizabeth Berkeley, was 18 years old, and her father, Richard Beauchamp (who had succeeded to the earldom of Warwick three years previously) was 22. Her parents had been married when her mother was not yet 10 years old, and for about six years the marriage had therefore remained unconsummated.5

Despite the fact that King Richard II was her father’s godfather, Margaret’s family, like that of John Talbot, had been drawn into the orbit of the house of Lancaster. Her paternal grandfather, Thomas Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, fought for John of Gaunt in Spain. Subsequently imprisoned by Richard II in that part of the Tower of London which now bears his name,6 Thomas only narrowly escaped execution. But he survived, to be pardoned and triumphantly set free by Henry IV. However, he had died before Margaret was born, so she had never known him.

Eleanor’s maternal grandfather, Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, from his tomb effigy in Warwick.

Margaret could possibly just remember her father’s mother, after whom she had been named. Margaret Ferrers, dowager Countess of Warwick, had been some years younger than her husband. Even so, she had not long survived him. Little Margaret had been barely 3 years old when her paternal grandmother had died.

Her maternal grandmother had been yet another Margaret – Margaret de Lisle. This grandmother had died twelve years before her granddaughter was born, and was therefore unknown to her except by name. The fact that she had been the heiress to the de Lisle title was not forgotten, however, and Margaret Beauchamp made use of this information in her ambitions for her own children.

As for her mother’s father, Thomas, Lord Berkeley must have been very well known to Margaret. When he had died, in 1417, Margaret was already 13 years old. Old enough, certainly, to be well aware of the unseemly wrangles over land and titles that immediately followed her grandfather’s death.

The Berkeleys were of an ancient family line. They could trace their English ancestry back to before the Norman Conquest. Elizabeth Berkeley thought she should have been her father’s heiress; an opinion in which her father had concurred. Despite this, the Berkeley title was claimed by a male cousin. From this sprang the acrimonious and long-running Berkeley inheritance dispute, in which Margaret Beauchamp, as her mother’s co-heiress, soon became a chief player.

Eleanor Talbot’s maternal great-grandparents, Thomas, Lord Berkeley and Margaret de Lisle, from their tomb brass at Wotton-under-Edge, Gloucestershire.

Margaret’s grandparents, Lord and Lady Berkeley, had been buried together in a single tomb at Wotton-under-Edge parish church in Gloucestershire. If their tomb inscription is to be believed, they had been a happy couple:

Nos quos certus amor primis conjunxit ab annis

iunxit idem tumulus, junxit idemque polus.

In youth our parents joyn’d our hands, ourselves our harts,

This Tombe our bodyes hath; th’heavens our better parts.7

As for Margaret’s father, Richard Beauchamp, he had been knighted at the coronation of Henry IV, and had succeeded to the earldom of Warwick in 1401. He had served Henry IV in Wales, and, after fighting bravely at the battle of Shrewsbury, on 21 July 1403, he had on the day following the battle, been made a knight of the Garter by the grateful king. This had been in the year preceding Margaret’s birth. Not long afterwards, the king had licensed Richard Beauchamp to travel abroad. He had been away for two years, making pilgrimage to both Rome and the Holy Land, as well as travelling elsewhere in Europe. He had returned to England by 1406, and in 1407 Margaret’s younger sister, Eleanor, had made her appearance.

On 9 May 1410, her father was appointed a member of the royal council, and he had emerged as a major figure in the reign of Henry V, at whose coronation he had served as Lord High Steward; he deputised the same role for the Duke of Clarence seven years later when Catherine of France was crowned as Henry’s queen. On this latter occasion he had presumably sampled the banquet served to her by John Talbot (then Lord Furnival).

The year after Henry V’s coronation, Warwick had been appointed deputy of Calais, and shortly thereafter he had been sent to represent England at the Council of Constance. He had probably not returned to England until 1415.8 Her father’s absences abroad as pilgrim, tourist, soldier and diplomat, had caused a hiatus in the birth of his children, but in 1417 another daughter – Margaret’s youngest full sister, Elizabeth – had been born. Elizabeth is the last known child of the Earl of Warwick by his first wife. After her birth he was abroad a great deal, in France, serving Henry V in asserting his claim to the throne of France. Thus the couple had no surviving son when Elizabeth Berkeley, Countess of Warwick, died in 1422, at the age of 36.9

At this time Warwick’s coheiresses were apparently Margaret and her two sisters. However, their father was only 40 when their mother died, so it can have come as no surprise to his daughters when, within a year or two of Elizabeth’s death, he married again. Perhaps it seemed a little bizarre to Margaret that her new stepmother, Isabel Despenser (who was also her third cousin), should be only four years older than she was herself. Naturally, however, her father’s second wife had to be young if his hopes for a son were to be fulfilled.

In fact, Isabel Despenser can never have seemed much like a stepmother to Margaret. Not only were they too close in age but also Margaret left her father’s house within a year or so of his second marriage, to marry John Talbot. She was already Lady Talbot when the news reached her that the new Countess of Warwick had succeeded where her own mother had failed. The birth of her little half-brother, Henry, in March 1424/5, robbed her of the hope of her father’s inheritance.10 Henry remained the Earl of Warwick’s only son, although the Countess Isabel bore the earl another daughter, Anne, in September 1426.11

Margaret’s own mother, Elizabeth, the late Countess of Warwick, had been laid to rest beneath a fair marble tomb in Kingswood Abbey, Gloucestershire, a house of which she had been hereditary foundress and patroness. Nothing now remains of Kingswood Abbey except the gatehouse, and even the site of the former Abbey Church is disputed, so Elizabeth’s tomb is lost. Even by the early seventeenth century no trace of it remained. However, a record of the inscription which it had once borne was preserved at Berkeley Castle:

Here lies the lady Elizabeth, late Countess and first wife of Richard de Beauchamp, late Earl of Warwick, and daughter and heiress of Thomas, late Lord of Berkeley and of Lisle (the which lordship of Lisle was held by this same Thomas according to the law of England after the death of Margaret, his late wife, mother of the aforesaid Elizabeth), the which Richard and Elizabeth had issue Margaret, Eleanor and Elizabeth. Which Countess Elizabeth died in truth on the 28th day of December in the year of the Lord 1422, on whose soul may God have mercy, Amen.12

This was less a memorial inscription than a declaration of war by the countess’s family on her cousin James, the male claimant to the honour of Berkeley. The fight for the rights enshrined in this manifesto would occupy most of Margaret Beauchamp’s life. It was a struggle which would blight her family down to the third generation, and which was destined ultimately to extinguish her male posterity.13