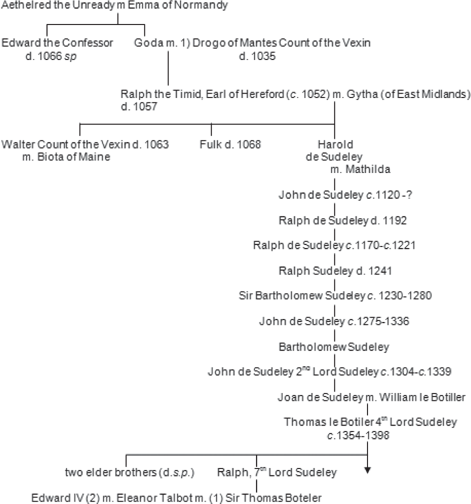

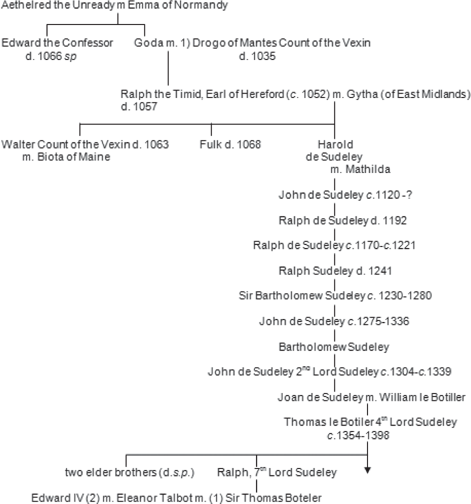

The royal descent of Sir Thomas Boteler.

So far we have explored Eleanor’s early life within the context of her birth family, the Talbots. We have found her living in the Talbot family homes. We have got to know her father, her mother, her brothers, her sister, and her cousins. From the moment of her union with Thomas Boteler the main focus of Eleanor’s life naturally shifts away from her birth family, to the Botelers, her new family by marriage. In the next four chapters we shall be exploring the various connections which resulted from this alliance. We shall meet Eleanor’s parents-in-law, her husband, and also some of the members of the wider Boteler family.

In Thomas Boteler, Eleanor Talbot was marrying a man more than twice her age, at a time when she herself was little more than a child. Whether she had ever met Thomas before her marriage, whether she had any say in the decision, it is impossible to know.

Thomas Boteler was a direct descendant of the pre-Norman Conquest English royal house of Wessex. His English royal descent was from Goda, a sister of King St Edward the Confessor. Like her brother, the penultimate Saxon king of England, Goda was also descended (on her mother’s side) from the Dukes of Normandy. Goda’s grandson, Harold, had founded the Sudeley family. As for Thomas’s Boteler (Botiler) forebears, they had settled at Wem in Shropshire, which was at no great distance from the Talbots’ home at Blakemere. Rather like the Talbots, they had risen from the ranks of the gentry. In the case of the Boteler family, their elevation had come about as a result of the marriage of Thomas’s great-grandfather William le Botiler of Wem, Shropshire, with Joan, the heiress of the de Sudeley family, a marriage that had raised the Botelers to the minor aristocracy.

The royal descent of Sir Thomas Boteler.

Through his mother, Thomas Boteler’s grandfather and namesake had inherited the title Lord of Sudeley. This earlier Thomas Boteler had died in 1398, but his wife, Alice Beauchamp, lived on until 1443. Eleanor’s Thomas may well have known Alice, and her second husband, Sir John Dalyngrygg.1

Alice Beauchamp bore her first husband three sons, who held the Sudeley title in succession. Eleanor’s father-in-law Ralph was the youngest son. Ralph’s oldest brother John had died childless and unmarried in 1410. William, the second son, was then Lord of Sudeley for seven years, before he too died childless. William’s widow Alice was a lady of some importance (although nothing is known of her family), because in 1424 she was appointed the governess of King Henry VI, with leave to chastise him when necessary – a right which she probably used sparingly, for Henry VI remembered her with affection and periodically made her gifts when he was grown up.2

In addition to his two elder brothers, Ralph Boteler also had at least two sisters. Their marriages provided Eleanor’s new husband with several cousins, the most important of whom was probably Sir Thomas Montgomery. But there were also a number of others. We shall return to them later (see chapter 9).

Lord Sudeley was a little younger than Lord Shrewsbury, having been born in about 1393.3 At the time of his son’s marriage to Eleanor Talbot, Lord Sudeley would have been about 56 years old. Thomas Boteler, his only child, was then probably 28, whereas Eleanor, the chosen bride, was only 13. However, such an age difference would not have been thought unusual at that period.

The marriage, in any case, would at first have been in name only. Consummation of a marriage where one or both parties were minors was deferred until the junior partner had reached what was seen as a suitable age – normally either 14 or 16 years.4 Until she reached such an age, Eleanor would have lived under the care of her parents-in-law (and most particularly, of her mother-in-law) and in their house. This means that Eleanor will have spent at least some of her early teenage years at Sudeley Castle.

This castle had been inherited by her father-in-law from his de Sudeley forebears. Illustrations exist which show Sudeley Castle in its pre-fifteenth-century incarnation, as a simple motte-and-bailey construction. What condition it was in when Ralph took it over is unknown, but in the 1440s he rebuilt and refurbished it on quite a grand scale.5 Perhaps because of the scale of the rebuilding, Ralph had to seek Henry VI’s pardon for having crenellated it without licence.6 Since Ralph Boteler’s time, there has been significant reconstruction at Sudeley, by Richard, Duke of Gloucester, (Richard III) and other later inhabitants, but the fundamental layout of Ralph’s work remains, as do parts of his castle building. Thus the outlines of the Sudeley Castle to which Lady Eleanor Talbot came following her marriage to Thomas Boteler can still be discerned:

The surviving buildings consist of the north or outer court, the south or inner court whose south side is missing, and the church east of the east range and the barn west of the approach to the house from the north. Boteler’s buildings must have covered much the same area as the present house and ruins. The simple gateway from the north to the outer court is his work, c.1442, and there is much masonry in the west range of the inner court that is of this time, though the appearance of this range is now largely Victorian. Whether this masonry represents a mere curtain wall enclosing the court it is difficult to determine, as none of the masonry above the ground floor appears to be early. At the two ends of the former cross range between the courts the Portmare Tower at the west end and the Garderobe Tower at the east end, together with the fragment of the undercroft of an adjacent tower, are also Boteler’s work. The most considerable remains of Boteler’s buildings however are the church and the ruins of the great barn … The great barn, which stands almost to wall-plate level with gables complete at both ends, is mid-fifteenth century. On the east side there are two entrances with four-centred arches, and towards the south end a lower four-centred arch with windows above, where originally the barn must have had two storeys. It is butressed all round and must have had eleven or twelve bays. The south gable has a curious finial like the ones on the tithe barn at Stanway.7

The Boteler Family of Sudeley – sons.

When Eleanor first saw Sudeley Castle, building work was probably still in progress. Indeed, the castle chapel (or St Mary’s Church, as it is now known) had not yet been erected. Ralph Boteler had been his parents’ youngest son, and he only inherited the family title ‘Lord of Sudeley’ in 1417, when his second brother, William, died.8 Ralph was then aged about 24, and may already have been a knight. (He is referred to as a knight in 1418, though confusingly in 1419 he is called ‘esquire’.) Ralph may have been with the young King Henry V in France when he inherited his title. If not, he must have joined the king in France shortly afterwards. In 1420–21 he received grants of land in France. In 1423 he was captain of Arques and Crotoy, and in 1425 he took musters in Calais.

Ralph’s service abroad was not uninterrupted, however. In 1419 he must have been in England at some point, for it was about then that he married the recently widowed Elizabeth Norbury, stepdaughter of his own sister Lady Say. His new wife was about the same age as her husband. It was probably a year or two later that Elizabeth gave birth to the couple’s only child, Ralph’s son Thomas.

Ralph was again in England in 1430, when he took muster of the troops going to France. He himself is not known to have returned to France until the following year. His commission to execute certain provisions of the will of Henry V might have been fulfilled either in France or in England, but his later roles of king’s knight and chief butler sound superficially more likely to have been carried out in England. On the other hand, his post as chamberlain to the regent of France, the Duke of Bedford, and his membership of the king’s councils in France and Normandy must all surely have been performed on the Continent.

The overall impression is that while Ralph clearly served in France throughout the 1430s and into the 1440s, he was probably in England rather more frequently than was Lord Talbot. In the spring of 1440 Ralph was made a Knight of the Garter, and eighteen months later, on 10 September 1441 he was created first Baron Sudeley. The following year he was charged with negotiating a treaty with the French. It was at about this time that his mother died. From 1443 to 1446 Lord Sudeley was employed in the treasury and during 1445 was High Treasurer of England. In 1450, probably soon after Eleanor’s marriage to his son, Thomas, he was sent to take charge of the defence of Calais. It may be Lord Sudeley’s absence on the Continent that in part explains his slowness in assigning property to his son and his new daughter-in-law (see below).

The Botelers had some kind of family link with East Anglia, and Lord Sudeley was certainly in the eastern counties on occasions. A 2005 metal detector find from Great Tey in Essex consists of a harness pendant in gilt and enamelled bronze alloy, showing what could be the Sudeley arms. Unfortunately the coloured enamel is now lost, which makes positive identification of the arms difficult.9 However, there is no doubt that Lord Sudeley was at Stoke-by-Nayland in Suffolk on 6 October 1466, for on that occasion he witnessed articles of agreement between Richard Wethermerssh (a gentleman of Colchester and member of Sir John Howard’s affinity) and Philip Mannok. This agreement aimed to protect Mannok’s interests, together with those of Sir John Howard himself, Ralph Chamberleyn, John Tendring and the Prior of Horkesley. The other named witnesses were local gentry: Sir Richard Waldegrave and Gilbert Debenham.10

Lord Sudeley and his second wife were also formerly commemorated in a stained-glass window at ‘Chylton Cherche’.11 The village of Chilton in Suffolk is now a suburb of Sudbury. It seems that a little of the glass commemorating Ralph and Alice Boteler, Lord and Lady Sudeley, has survived, for in the Crane Chapel ‘the east window retains two lovely little figures of late fifteenth-century glass in its tracery lights. One shows St Apollonia bearing her emblem, the pincers … [in the other] St Michael is shown with raised sword vanquishing a blue demon’12 (see plate 28). The Cranes, some of whose monuments are also in this chapel that bears their name, were presumably cousins of Lord Sudeley, for Botelers had held the manor of Chilton from 1333 until 1400, when it passed to William Crane of Stonham as part of the settlement when he married Marjorie Boteler. The Crane arms intimate a connection with Lord Sudeley’s family.

As Lord Sudeley, Ralph seems to have consistently employed a circular seal matrix engraved with his arms and style. This was of relatively modest size, with no counterseal. The single-sided, red wax impressions produced from this matrix were attached to their documents by strips of parchment in the usual way. Impressions of Lord Sudeley’s seal survive, in varying states of preservation, in the Warwick County Record Office (on L1/79, 80, 82 and 88). None is complete, but the best preserved is that on L1/82. The arms shown are quarterly 1 and 4 Boteler, 2 and 3 Sudeley. The inscription is also incomplete, but appears to run:

[sigillu]m radulphi buttiler d[om]ini [de?] s[u]del[ey]

(The seal of Ralph Buttiler, Lord of Sudeley)