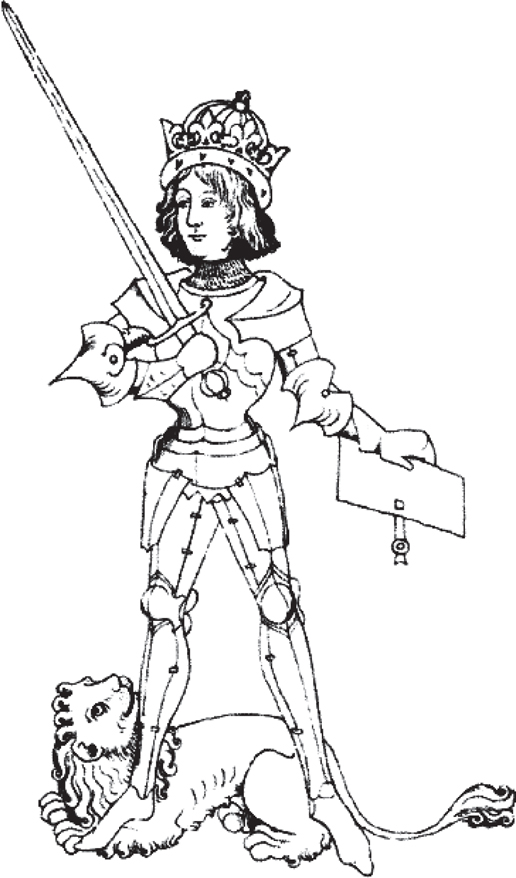

The Great Seal of King Edward IV.

During the 1450s, as we have seen, the Talbot family had become increasingly split between the rival factions of Lancaster and York. Eleanor’s half-brother, the second Earl of Shrewsbury, had become a moderate supporter of the Court Party. Her mother and her brother, Humphrey, by a kind of magnetic repulsion, moved slowly but surely towards support of the Yorkist cause.

Of the members of Eleanor’s family by marriage, Lord Sudeley, at least, remained a Lancastrian. The Botelers, however, like the Talbots, were awkwardly poised between the dividing loyalties of the age. Lord Sudeley (and perhaps also his son) may have borne arms for Henry VI, but Lord Sudeley’s sister, Lady Say, was godmother to the Duke of York’s eldest son, Edward, Earl of March. One of Lady Say’s sons, Thomas Montgomery, was to be knighted in 1461 by Edward (by then, King Edward IV) as a reward for his strenuous exertions on the Yorkist side at the battle of Towton. Unfortunately the same king was also obliged to execute Thomas Montgomery’s younger brother, John, at about the same time, for his exertions in the opposite direction.

The Great Seal of King Edward IV.

Perhaps Lord Sudeley and his son were with the royal army that marched from Nottingham into Shropshire in 1459 to prevent the union of the Neville forces from the north with the army of the Duke of York. As things fell out this force was not engaged in battle, for another Lancastrian army, under the nominal command of the young Prince of Wales (and actually led by Lord Audley) encountered the Earl of Salisbury’s men first, at Blore Heath, and was defeated by them. As we have seen, it is conceivable – though by no means certain – that Sir Thomas Boteler was killed or fatally injured at Blore Heath. At all events, he died at about this time.

Meanwhile, as a result of the battle of Blore Heath, Salisbury’s men were able to join up with the Duke of York’s army at Ludlow. Nevertheless, York was deserted by his strongest contingent, the men from the Calais garrison, who refused to fight against the king. Consequently the Duke of York fled back to Ireland, while the Nevilles, together with York’s eldest son, the Earl of March, took ship for Calais.

From all these events John Mowbray, third Duke of Norfolk (the father-in-law of Eleanor’s sister Elizabeth) held aloof. He attended the parliament held by Henry VI at Coventry towards the end of the year and, when required, took the oath to the Lancastrian succession. It was perhaps to persuade Norfolk to this oath that on 11 December Henry VI made him a grant of £50 a year for life.1 When the Yorkist lords returned in 1460, the Duke of Norfolk kept a fairly low profile. By July 1460, when the Yorkists entered London, Elizabeth Talbot’s father-in-law, the Duke of Norfolk, may have bestirred himself to more active support of his uncle’s cause. However, Norfolk took no part, apparently, in the battle of Northampton on 10 July 1460 – a battle in which Eleanor’s half-brother, the second Earl of Shrewsbury, was killed fighting for Henry VI.

In any case, the weather that summer was not such as to inspire anyone to take the field. Like Eleanor, the heavens were in mourning. It rained incessantly, flooding mills and sweeping away bridges. The sodden crops rotted in the fields and roads were deep in mire.2 At this time, the Duke of York’s eldest son, Edward, Earl of March, was in the eastern counties. In August 1460 he seems to have been staying with the Duke of Norfolk’s cousin, John Howard esquire (as he was at that time) at Stoke-by-Nayland in Suffolk. On 27 August, Edward was named as a feoffee, together with Howard and well-attested members of the latter’s household such as Thomas Moleyns and Robert Cumberton, in respect of a messuage and land at nearby Higham and Stratford-St-Mary.3

Although the Mowbrays’ ducal title related to Norfolk, the principal Mowbray seat of Framlingham Castle was, in fact, also located in the county of Suffolk. Therefore it is just possible that Edward met Eleanor somewhere in Suffolk during the summer of 1460. Eleanor had already been a widow for more than seven months by that time, and might perhaps have spent part of the summer of 1460 visiting her sister. The month of August contained a key feast of the Blessed Virgin Mary (the Feast of the Assumption), and the eastern counties contained many celebrated Marian shrines. In spite of the Lancastrianism of her father-in-law (and perhaps also of her dead husband), if Eleanor was visiting the Mowbrays at the same time as Edward was staying with their cousin, John Howard, she would have encountered no difficulty in being presented to the young Yorkist prince. But unfortunately Eleanor’s precise movements after becoming a widow are not on record.

Obviously, since no historian has ever questioned that a relationship of some kind did exist between Edward and Eleanor (see below), the couple must have met at some stage. There are a number of possible dates and locations for such a meeting. As we have already seen, if Eleanor happened to have visited France with her mother in her childhood, she could potentially have first seen a very young Edward, Earl of March, in Rouen. A second possibility is that she had met Edward when he was about to enter his teens and was living at the Castle of Ludlow. Eleanor’s own family owned a chain of estates along the Welsh border and during much of her childhood she had moved up and down between them. Her subsequent residence at Sudeley Castle, as the young bride of Thomas Boteler, would also have placed her in a location not too far from where the young Edward was resident at that period. But of course, at that time Eleanor was married.

Much more precise dates and locations for possible meetings present themselves in 1460 and 1461. For example, in November 1460, Edward would have passed by Eleanor’s Warwickshire manors as he travelled from the Welsh border to London. The couple might also have met after the battle of Mortimer’s Cross during the second week of February 1460/1, when Edward repeated his journey from the Welsh border to London – this time to claim the throne.

Both November 1460 and February 1460/1 offer very strong possibilities for Edward and Eleanor to have spent time together. However, the couple could not have contracted their marriage on either of those occasions. This is because the evidence shows that their marriage was celebrated by Canon Robert Stillington – a former servant of the government of King Henry VI, who only entered the service of Edward IV after the latter had been proclaimed king in London.

We also have several contenders for the possible role of introducing Eleanor to Edward. Thanks to her connection with the Duke of Norfolk, Eleanor’s sister, Elizabeth, would have been persona grata with the Duke of York and his family. At the same time, Eleanor’s uncle, the Earl of Warwick, was another of the Duke of York’s key supporters. So too was her late husband’s cousin, Thomas Montgomery. Any one of these three people might well have assisted in bringing about the fateful encounter between Eleanor and Edward.

On the basis of the evidence presently available, the couple had almost certainly met by the end of 1460. Probably neither the person who introduced them, nor indeed, Eleanor herself, foresaw any particular purpose behind the introduction, for ‘the scope of accident in human affairs is always far greater than can be ascertained’.4 What precisely occurred at their first meeting is not on record and must therefore remain a matter of speculation. As we shall see shortly, however, Edward probably found Eleanor attractive and attempted to seduce her. Confronted in response by her religious and other scruples, he may then have proposed marriage. The subsequent 1484 Act of Parliament stated that Edward and Eleanor had been married for a ‘long tyme after’ 1464. Since Eleanor died in 1468, in this context the words ‘long tyme’ apparently implied approximately four years. Since the act also stated that they were married a ‘long tyme bifore’ 1464, the couple must have married in 1460 or 1461.

We may try to picture the two young Talbot sisters – Eleanor just 24 years old and Elizabeth aged 17 – as they would have been in the summer of 1460. No positively identifiable portrait of Eleanor now survives. We know that she was once depicted, together with her brothers and sister, as a mourner, on her mother’s lost tomb at old St Paul’s Cathedral. It is possible that she was also later depicted, together with her mother, her sister, and her aunt, Anne, Countess of Warwick, on the surviving Coventry tapestry, made in about 1500. (For the relevant images, see below, chapter 15.) As for Elizabeth Talbot, the only definite surviving representation of her dates from a later period, when she would have been approaching the age of 40 (see plate 17). However, it seems likely that Elizabeth had her father’s dark colouring. This colouring was also exhibited by others of John Talbot’s descendants, and Eleanor probably shared it.

We may therefore imagine Eleanor and Elizabeth with dark brown or black hair, and brown eyes. Both girls probably also had aquiline noses, a combination of the genes inherited from their father and mother. As we have already noted, Elizabeth is reported to have been beautiful.5 Probably Eleanor was too. At all events, it is clear that her appearance was sufficiently striking to attract the young Earl of March. The skeleton in Norwich that may be Eleanor’s is that of a healthy young woman, who in life stood some 5ft 6in tall.

Edward, at this point (November 1460–February 1460/1), was 18 years old, 6ft 2in in height and had brown hair.6 At this stage of his life he appears to have been attracted by women older than himself. Possibly he also preferred brunettes. Both Eleanor Talbot and Elizabeth Widville were slightly older than Edward. Moreover, despite a persistent legend that she was fair, one portrait of Elizabeth Widville at Queens’ College, Cambridge, shows dark auburn hair under the front edge of her headdress.

Fortunately for them, neither the Earl of March nor the Duke of Norfolk were anywhere near the battle of Wakefield, at the end of December, when the Duke of York, his second surviving son the Earl of Rutland, and the head of the Neville family, the Earl of Salisbury, were all killed by Queen Margaret’s men. At the time of this battle, which then appeared to mark the complete destruction of the Yorkist cause, Norfolk was safe in London with Eleanor’s uncle, the Earl of Warwick.

In the following months, however, the situation in England suddenly changed. The new Yorkist leader, the young Earl of March, won a victory at Mortimer’s Cross. Unfortunately, the Duke of Norfolk, still with the Earl of Warwick, had the misfortune to fight instead at the second battle of St Alban’s, on Tuesday 17 February 1460/1, when the Yorkists were defeated once again. Norfolk escaped from the battlefield and made his way safely back to London.

There, a fortnight later, on Tuesday 3 March, Norfolk and his brother-in-law, the Archbishop of Canterbury, attended a council of Yorkist lords held at Baynard’s Castle, which was then the London home of Cecily Neville, the dowager Duchess of York. This meeting supported the proclamation of the Earl of March as King Edward IV. Norfolk also attended the new king’s enthronement at Westminster on the following day. Thereafter the duke marched north with the new king, and on Palm Sunday, 29 March, fought bravely at the bloody battle of Towton, which secured Edward’s position on the throne of England.

The young King Edward IV.

In the first edition of this book, I suggested that, after the battle of Towton, Edward IV returned south by an eastern route and may have secretly married Eleanor in the Norwich area, in April 1461. This suggestion was based on the fact that a document was issued in Norwich in the king’s name in that month. However, it is now clear that Edward’s journey south did not include Norwich. On his way back to London the new young king actually rode via Coventry, Warwick and Daventry.

At the start of the second week of June, travelling between Warwick and Daventry, Edward IV once again passed close by Eleanor’s manors of Fenny Compton and Burton Dassett. As we have seen, the first of these manors had now been granted to Eleanor absolutely by her former father-in-law, Lord Sudeley, while the second of the two manors was held by Eleanor for life, as part of her jointure. Therefore, if a formal secret marriage between Edward and Eleanor did indeed take place, the most likely date for it can now be pinpointed as Monday 8 June 1461. The secret marriage was probably very quietly celebrated at one of Eleanor’s two Warwickshire manors – just as Edward’s later secret marriage with Elizabeth Widville was privately celebrated at the Widville family manor in Northamptonshire. More than a year had now passed since Sir Thomas Boteler’s death, and by June 1461 Eleanor would have been out of mourning for five or six months.

At this point it is important to establish with absolute clarity two essential points about the story of Edward and Eleanor. First, a relationship undoubtedly existed between them. For political reasons, the later Tudor writers entirely omitted Eleanor from their histories.7 But since the seventeenth century, when Eleanor’s existence was once again generally acknowledged, not one single historian has ever questioned her association with Edward IV. We may therefore assert with absolute confidence that they were partners. The chronology of the king’s love affairs also implies that his association with Eleanor must have begun either in the summer of 1460, when he was still Earl of March, or early in 1461, very soon after he attained the throne. We have already explored what may have taken place between Edward and Eleanor between the summer of 1460 and the summer of 1461. As for what happened subsequently, possibly as early as the autumn of 1461 the king was already moving on to pastures new. There are later accounts which suggest that he may have taken a mistress at about that time, who then bore him a daughter in the following year.8

Second, it was formally claimed in 1483–1485 that Edward and Eleanor had been married, and this claim was accepted by Parliament. It is possible that this marriage claim had been advanced earlier. For example, it may have been publicised in about 1475, by supporters of George, Duke of Clarence. Such a claim on his behalf could well have been one of the factors which ultimately led to his execution. At all events, it is definitely recorded by Domenico Mancini that in 1475 Elizabeth Widville herself began to express concern regarding the validity of her own secret marriage of 1464 with King Edward IV. It appears that she also began to fear that her children by the king would ultimately find themselves legally excluded from succession to the throne. Later, of course, any reference to a legal relationship between Edward and Eleanor was firmly pencilled out of history in England by Henry VII and his government from August 1485. Nevertheless, reports of the existence of such a marriage remained on record in other European countries well into the sixteenth century.

It is only the precise nature of Eleanor’s relationship with Edward that constitutes the point at issue, for no one has ever disputed that a relationship existed between them. Given that context, both Eleanor’s high rank and her notable piety clearly militate against the notion that she would willingly have accepted the role of royal mistress. At the same time Edward’s subsequent conduct in respect of Elizabeth Widville (with whom he undoubtedly contracted a secret union) makes it entirely plausible that he may have pursued a similar course earlier with Eleanor. And of course, fifteenth-century sources exist which report that he did so.9 Moreover, the great nineteenth-century historian James Gairdner argued firmly that ‘no sufficient grounds’ have been brought forward for regarding such a secret marriage between Edward IV and Eleanor Talbot as ‘a mere political invention’.10 This leads logically to the conclusion that the relationship between Edward IV and Eleanor Talbot was neither more nor less than marriage. The Act of Parliament of 1484 is quite explicit on this point (see appendix 1).

Unfortunately, the widespread use of the term precontract in relation to this union is unhelpful, because the meaning of this term is very widely misunderstood. The word is often taken to imply something like ‘betrothal’. But in fact, precontract is a legal term which can only be applied retrospectively. In other words, it was never possible to actually enter into an agreement called a precontract. The contract to which the term refers is (and was) precisely a contract of marriage. Such a marriage contract could only become pre- retrospectively, in relation to a subsequent second (and necessarily bigamous) contract of marriage with a third party. In the case of Edward IV the second and bigamous contract of marriage was the one with Elizabeth Widville, which dated from 1464.

Thus at the time when it was made – probably on 8 June 1461 – any contract between Edward IV and Eleanor Talbot would simply have been a contract of marriage. To refer to it from its inception as a precontract is therefore both misleading and inaccurate. Indeed, it is tantamount to implying that, at the time of his relationship with Eleanor, Edward IV already envisaged a subsequent second contract of marriage with Elizabeth Widville – an implication which is certainly unjust to all three of the people involved.

It has always been the Church’s teaching that marriage is a self-conferring sacrament, effected by the free consent of the parties and confirmed by consummation. In the Middle Ages (when marriage had not yet become a civil contract) the logic of this argument led ineluctably to the conclusion that no form of public ceremony was therefore essential. Thus, a simple promise per verba de futuro – that is to say, marriage by means of a promise couched in the future tense, as in ‘I will marry you’ – consolidated by subsequent sexual intercourse, constituted a valid marriage. Such marriages were recognised (if not greatly favoured) by the Church, and had been formally acknowledged by decretals of Pope Alexander III.11 Some writers have therefore suggested that Edward and Eleanor made an informal marriage contract of this kind.

There seems to be absolutely no doubt that Edward found Eleanor attractive. It also appears certain that she responded to his advances with acceptance once those advances were couched in a form which was morally acceptable to her. Since Edward IV is reputed to have had a strong sex drive, he would probably have found it hard to accept a rejection of his advances. If Eleanor did not immediately respond to his lovemaking in the manner he had hoped for, did he therefore utter those dangerous words ‘I’ll marry you’ simply in order to achieve his sexual objective? A number of historical novelists have proposed precisely this scenario to explain the story of Edward and Eleanor. However, this superficially enticing picture does not match the surviving evidence.

The problem is that such a scene could only have been enacted in private – in which case it would have remained a secret forever. But in the case of Edward’s relationship with Eleanor there was reportedly at least one witness. Moreover, this witness was not a layman, but an ecclesiastic who was an expert in canon law, and therefore able to evaluate very precisely the significance both of the event and the words uttered. This witness – who is even described by one source as the clerical celebrant of the marriage – was Canon (later Bishop) Stillington. His presence indicates clearly that whatever words were exchanged between Edward IV and Eleanor cannot possibly have consisted only of promises uttered on the spur of the moment. If Edward had simply been attempting to persuade Eleanor to come to bed with him he would hardly have arranged for a priest to witness his seduction! In other words, the presence of a witness – particularly a clerical witness – shows that at some stage a formal exchange of vows took place between Edward and Eleanor. Such an event can hardly have taken place in a spontaneous manner. It must have had some advance planning.

Moreover, the notion that Edward IV thoughtlessly uttered words that he did not mean, merely to ensure that he could have sex with Eleanor, would imply a callously indifferent relationship between the couple. But this is not consistent with the broader evidence. Although the couple never lived together for a period of months or years, Eleanor’s subsequent conduct in respect of Edward IV was tactful and discreet. It more closely resembles that of Maria Smythe (Mrs Fitzherbert), the undoubted secret wife of George IV, than that of Lucy Walter, the probable mistress of King Charles II. For Eleanor never made any attempt to establish her marriage publicly, by means of the Church courts. At the same time, while he never acknowledged her as his wife, Edward IV appears to have felt certain obligations in respect of Eleanor. Thus he probably gave her property, and he treated her, her feelings and her relations (including her father-in-law, Lord Sudeley) with a degree of respect while she was alive.

All these factors considered together imply that the alleged secret marriage between Edward and Eleanor comprised something more than a mere casual uttering of unmeant promises on the part of a youthful king, eager for sexual fulfillment. Even when their sexual partnership had ended, both parties continued to treat each other, and their relationship, with a degree of respect. It therefore appears that what took place between them must have included a serious, if private, exchange of marriage vows – very similar to the ceremony later said to have been secretly conducted between Edward IV and Elizabeth Widville.

Given the essential nature of a secret contract, together with Edward IV’s later behaviour, and Eleanor’s subsequent decisions in respect of her own life (see below), it is not surprising that the sources available to us are not precisely contemporary with the event. They date from twenty years later, when both parties to the contract were dead. Nevertheless, given that during the second half of the fifteenth century Edward IV’s marriage with Eleanor Talbot was asserted, that the reality of this marriage was accepted as a fact by Parliament, and that no evidence to disprove its existence was subsequently produced by Henry VII – despite his very urgent political need to reverse the parliamentary decision of 1484 – it is not unreasonable to accept that such a marriage existed.

Historians have certainly accepted working hypotheses in respect of other reputed medieval royal marriages that rest on much less solid evidence than three almost contemporary written sources, one of which is an Act of Parliament. For example, the documentary evidence in support of an alleged marriage between Henry V’s widow Queen Catherine and Owen Tudor is both less full and chronologically later (in relation to the alleged event) than is the case in respect of Edward IV’s Talbot marriage. Thus, in respect of Catherine’s union with Owen it has been observed that ‘the pot-pourri of myth, romanticism, tradition and anti-Tudor propaganda surrounding this match is rarely borne out by historical fact’.12 In fact, the chief evidence for the Tudor–Valois union seems to be the birth of offspring – a circumstance that is of course lacking in the case of Edward IV and Eleanor Talbot.

It is not clear why secrecy might initially have been seen as an essential element of Edward’s alleged contract with Eleanor. There are three possible explanations for this. The first possibility is that Edward had not yet sought or obtained the approval of his parents. The second is that a deliberately secret marriage was merely Edward’s dishonourable way of tricking and deceiving Eleanor. The third possibility is that Edward was following an ancient tradition by coupling first and awaiting results. If Eleanor had become pregnant perhaps he would then have acknowledged their marriage. Incidentally, this may also have been how he handled things in connection with his subsequent secret marriage with Elizabeth Widville.

In respect of the first suggestion, if Edward and Eleanor met in the summer of 1460 (before Edward became king, and while the Duke of York was still living), and if Edward made a promise of marriage at that stage, it is possible that the element of secrecy arose initially from the fact that Edward had not had the opportunity to discuss the matter with his parents. Edward may well have feared that his father and mother would regard a marriage to an English earl’s daughter as sacrificing the opportunity for a political alliance with a foreign princess. It is known that an earlier attempt had been made to marry Edward to one of the daughters of King Charles VII of France.13

Regarding the second possibility, theoretically the fifteenth-century chivalric code placed a high importance on the keeping of one’s word. In general it was held that ‘an honourable man was bound to be true to his word – so long as it was publicly and honestly given, not made in secrecy, nor extorted, and in harmony with the true intention of the speaker.’14 In the present instance, however, we are dealing with a clandestine promise, possibly made under a degree of pressure (at least in Edward’s eyes) and where the king’s true intentions are a matter for speculation.

Edward IV was undoubtedly capable of telling lies and squaring such behaviour with his honour. He was to do so famously on his return from exile in 1471. On that occasion it was considered that ‘the lies that he told were mere “noysynge”, necessary to fulfill his true intention, which was in itself validated … by his true claim to the throne’.15 It is perfectly conceivable, therefore, that Edward would not have regarded himself as bound by any promise he may have made to Eleanor if he later found it inconvenient.

One surviving account of their first meeting does initially appear to support the view that Edward was playing a trick in order to get his own way. This account implies that he played out with Eleanor a scene remarkably similar to the one he subsequently enacted with Elizabeth Widville. According to Commynes, Edward ‘promised to marry her, provided that he could sleep with her first, and she consented’.16 But Commynes also tells us that Edward ‘had made this promise in the Bishop [of Bath]’s presence. And having done so, he slept with her.’17 Elsewhere, Commynes states explicitly that Stillington ‘had married them’.18 As we saw earlier, Stillington’s reported presence implies that the marriage must have post-dated Edward’s accession to the throne. It also implies that the marriage ceremony had been planned in advance – presumably at some earlier meeting between the couple.

Although a priestly officiant was not essential for a valid marriage, officially ‘priests were forbidden to participate in any clandestine marriages.’19 But despite this ecclesiastical prohibition, we know for certain that a priest did subsequently officiate at Edward IV’s clandestine marriage with Elizabeth Widville in 1464. As for Canon Stillington, he was not only an expert in canon law, but also a man of the world whose career was first and foremost that of a servant of the government. Indeed, he himself had several illegitimate children and during the course of his episcopate seems to have visited his diocese rather rarely.20

In point of fact, a private marriage required neither a priest nor any third party to be present, but in this case Stillington, as reported by Commynes, claimed a) that he had witnessed Edward’s contract of marriage with Eleanor, and b) that he had acted as the priestly celebrant. This would certainly explain how Stillington came to be aware of the existence of the marriage and was later able to publicise it. In addition to Commynes’ evidence, both Mancini and Vergil (neither of whom mentions Eleanor by name) refer to Edward IV’s involvement with a member of the Earl of Warwick’s family, and Mancini speaks specifically of a marriage promise.

It is, of course, quite possible that Edward had initially expected to make Eleanor his mistress. Doubly armoured in her strong religious principles and in her multiple noble and royal descent, however, she clearly considered herself far above this dubious honour. This outcome may well have surprised Edward, but since both she and Edward were unattached, from Eleanor’s point of view no impediment stood in the way of a more honourable resolution.

In the face of Eleanor’s presumed rejection of his initial advances, the king would have been faced with only two possible choices: either to accept defeat, or to accept her terms. He accordingly offered her marriage. For a young widow of her social class a second marriage would have been entirely normal. More than 45 per cent of such women remarried.21 Nor was there any legal impediment to prevent an English monarch from marrying a widow. An earlier fifteenth-century instance of such a royal marriage was that of Henry IV with Joanna of Navarre.

The alleged marriage of Edward and Eleanor is hypothetical only in that, while it is entirely plausible that Edward behaved as Commynes stated, no precise evidence is now available to prove that he did so. Since such evidence of the marriage was reportedly available in 1483 and 1484 (though it was later suppressed by Henry VII), it is clearly on the basis of the lack of surviving evidence that modern sceptics argue against a valid marriage between Edward IV and Eleanor Talbot. But, ironically, we know (because he himself said so) that the reason the evidence does not survive is because it was subsequently destroyed by Henry VII for his own political reasons. Certainly, in the nineteenth century, as we have seen, James Gairdner (by no means a credulous historian) concluded that there were no grounds for dismissing this marriage as ‘mere political invention’.22

The marriage therefore remains entirely credible. In addition to the explicit written sources, there is also clear circumstantial evidence that it existed, or at least, that some people believed it to exist. Why else, for example, should Elizabeth Widville herself have later expressed doubts concerning the validity of her own marriage with the king? As we have seen, when the Duke of Clarence appeared to be a threat to her sons, Elizabeth is said to have been particularly anxious because of ‘the calumnies with which she was reproached, namely that according to established usage she was not the legitimate wife of the king’.23

Moreover (as we have also seen) there was even, ultimately, a public acknowledgement of the marriage, though not by either of the partners, nor during their lifetimes.24 No one, either at the time of that public acknowledgement or later, ever came forward with evidence that the account of the Talbot marriage was a fabrication. No member of the house of York or of Eleanor’s own family spoke against the Act of Parliament of 1484. Some readers may consider that during the reign of Richard III this was scarcely surprising. Nevertheless, the situation changed entirely in 1485. Henry VII would have welcomed evidence undermining the Talbot marriage claim. Yet despite the fact that some members of the Talbot family were prominent amongst Henry’s supporters, no evidence was forthcoming. In these trying circumstances Henry could only seek to supress all mention of Eleanor and of her relationship with Edward IV, and that is precisely what he did.

Philippe de Commynes seems to have been of the opinion that Edward’s promise of marriage was merely his means of getting Eleanor into his bed:

King Edward had promised to marry [her] ... because he was in love with her, in order to get his own way with her ... and having done so he slept with her; and he made the promise only to deceive her.25

As we have seen, this interpretation does not coincide with the evidence Commynes himself presents for the presence of Canon Stillington. Yet even if Edward had not really meant what he promised, even if he was deliberately attempting to deceive Eleanor, that would have been immaterial in terms of the outcome. By virtue of the words uttered, together with the fact that both parties were free to make such promises, and followed by their subsequent consummation of their union, the couple were married.

Nor need we assume, with Commynes, that Edward’s intentions were nefarious from the outset. It may be that he meant his promise at the time and only changed his mind later. As we have seen, it is possible that he gave Eleanor estates in Wiltshire.26 We must remember that Eleanor was an earl’s daughter and a lady of royal descent. By birth she was the equal in rank of Edward’s own mother, Cecily Neville. She was therefore by no means a non-starter for the role of queen. She was at least as well born as Elizabeth Widville, whom Edward subsequently (and bigamously) married – also in secret. Moreover, one of Eleanor’s first cousins, Anne Neville, later became the queen consort of Edward IV’s younger brother, Richard III.

Eleanor’s story and that of Elizabeth Widville have obvious similarities. Both were widows from Lancastrian backgrounds, both were attractive, both were a little older than the king. And in both cases, apparently, Edward’s solution was the same. He went through a clandestine form of marriage and initially kept the affair quiet. Only the final outcomes differed.

One key distinction between Eleanor Talbot, (who failed to get the king to honour his contract with her) and Elizabeth Widville (who succeeded), was the latter’s proven fecundity, which Edward is said to have considered a great point in her favour. Although Buck later suggested that Edward and Eleanor may have had a child, there is absolutely no evidence to support this contention.27 In fact, the wording of Richard III’s Act of Parliament of 1484 explicitly rules out the possibility that Edward had children by Eleanor (see below, appendix 1, note 20). It seems unlikely that Eleanor ever conceived by either of her husbands. Moreover, her sister, the Duchess of Norfolk, also seems to have had some difficulty in conceiving. Another key difference was Elizabeth Widville’s great determination and strength of character. It is plausible that a third difference may lie in the possibility that Eleanor herself ultimately decided that marriage with Edward was not what she wanted. This point will be explored in greater depth shortly.

Let us now briefly look forward in time, to June 1483, when the question of Eleanor’s marriage at last became a public issue. In respect of the actions of Richard, Duke of Gloucester at that time, the objection has been raised that he should have referred the dispute in respect of Edward IV’s marriage to the church courts. As the present writer has pointed out previously, however, Richard himself was not a party to the marriage dispute, and his right to bring such a case would have been questionable. What had actually been raised in June 1483 was an issue concerning the succession to the throne of England. It is apparent that in instances where some other legal outcome (in this case, the inheritance of the crown) was contingent upon a disputed marriage, but where the validity of the marriage itself was not the main point at issue, civil courts unhesitatingly passed judgement without referring the marriage dispute to canon law.28 Moreover, in this case, the fact that the chief witness was a canon law expert may well have convinced Parliament that the Church had, in effect, already passed judgement on the question of the validity of the Talbot marriage.

Many records do survive of medieval women in Eleanor’s situation who successfully sought legal remedy in the Church courts to substantiate their married status. For Eleanor, however, such an action may never have seemed a realistic and practical possibility, given that she would have been challenging her sovereign. Noblewomen ‘were at a particular disadvantage when they disagreed or quarrelled with their husbands’.29 If the man in question also happened to be the king the disadvantage would, of course, have been considerably increased. It is also difficult to see when Eleanor might have taken action. For some months, at least, she probably expected Edward to keep faith with her. A further indeterminate period of doubt and confusion may then have followed. Also, the secrecy surrounding the king’s second and bigamous Widville marriage effectively precluded any protest against it on Eleanor’s part.

Meanwhile, in the summer of 1461 another and much more immediate matter was preoccupying the minds of the nobility of England. Early in June, the Duke of Norfolk and his family set out from Framlingham for Westminster to attend Edward IV’s coronation. The young Earl and Countess Warenne were presumably members of the party.30 It is even feasible that Countess Warenne’s widowed sister, Eleanor, also attended the ceremony. It was the Duchess of Norfolk’s brother, Archbishop Bourchier, who set the crown upon Edward’s head, while the Duke of Norfolk officiated at the ceremony as earl marshal. After the coronation the Mowbrays returned to Framlingham Castle, although the duke came up to London again in October, to attend the king at Greenwich Palace. By the end of that month at the latest, however, he was back at Framlingham again, and there, suddenly, on Friday 6 November, he died. It was not quite two months since he had celebrated his 46th birthday. His son and heir, John Mowbray, now fourth Duke of Norfolk, was still a minor, only a few weeks past his 17th birthday. The year 1461 had brought significant changes: a new king; a new dynasty ruling in England. Now Elizabeth Talbot had assumed the coronet of a duchess. Before the year ended would her sister Eleanor be wearing the queen consort’s crown?