Congruent Election: Understanding Salvation from an “Eternal Now” Perspective

Richard Land

When preaching God’s Word, a preacher might as well aim high. This essay will suggest a conceptual model that I believe provides a better way to understand the scriptural doctrine of election than some other traditional theological models offer.

God’s inerrant and holy Word never changes, and this inerrant and infallible Word of God does not contradict itself. However, human understanding of God’s Word is not infallible, and, as our Baptist forefathers believed, God always has yet more truth to break forth from His holy Word to those who are receptive to the Holy Spirit’s leading.

God’s Word is cast in stone, but no human formulation, confession, or doctrine should be. Christians must delve in as deeply and as humbly as they can and pray for as much knowledge, discernment, and insight as the Lord will grant them in their zeal to resolve any apparent difficulties. Christians must always seek an ever deepening and widening grasp of a totality of doctrine that is as congruent with as much of scriptural revelation as is possible. What understanding of a doctrine of election is in accord with the entire body of revealed Scripture—not just with certain proof texts?

Southern Baptist Beginnings: The Birth of a Theological Tradition

My understanding of the doctrine of election as I now conceptualize it comes from my immersion since infancy in the Sandy Creek heritage that permeates the Southern Baptist heritage and tradition. In recent decades some have attempted to abscond with our Southern Baptist history and heritage. Consequently, taking a short excursion into the history of the Baptist movement in the South is advisable in order to understand how in God’s providence we have arrived at the present situation.

John Leland, both a product and predominant leader of the Separate Baptist movement that swept across colonial America in the middle decades of the eighteenth century, was a circuit-riding preacher who personally baptized more than 20,000 people during his more than 20-year ministry in Virginia and North Carolina before going back to his native Massachusetts in 1791.1 Leland, a friend of both Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, played a key role in the First Amendment’s inclusion in the United States Constitution.

Why is Leland so important? As the most significant of the Separate Baptist leaders in the South, he had enormous influence because the Separate Baptists overwhelmed the other Baptist groups in the South within just a few years of their North Carolina Sandy Creek revivals in the 1750s.

In 1791, Leland said,

I conclude that the eternal purposes of God and the freedom of the human will are both truths, and it is a matter of fact that the preaching that has been most blessed of God and most profitable to men is the doctrine of sovereign grace in the salvation of souls, mixed with a little of what is called Arminianism.2

Leland’s statement is as good a short summary of the Baptist Faith and Message’s soteriology as you will find. Leland went on to say,

These two propositions can be tolerably well reconciled together, but the modern misfortunate is [some things never change!] that men often spend too much time in explaining away one or the other, or in fixing the lock-link to join the others together; and by such means have but little time in a sermon to insist on these two great things which God blesses.3

Sydney Ahlstrom, the renowned, prize-winning Yale historian, who, as a Lutheran, has no dog in this fight, surveyed the history of eighteenth-century Baptist development in America, particularly the South, and concluded, “The general doctrinal position of the resulting Baptist tradition was distinctly Reformed, a modified version of Westminster.”4 The ultimate result “was a blending of revivalistic and ‘orthodox’ tendencies, along the lines suggested by John Leland’s compromise.”5 With the passage of time, the New Hampshire Confession (1833) “came to express this majority view.”6 The New Hampshire Confession is the progenitor of the Baptist Faith and Message—its most famous and influential descendant.

Prior to the First Great Awakening, Baptists were a small, persecuted sect throughout Colonial America, with the South perhaps the least populated with a Baptist presence. Then came the mighty spiritual wind of the Great Awakening and the miracle of Sandy Creek in North Carolina. The exponential growth of Baptists in the South, resulting from the Great Awakening, and the consequent rise of the Separate Baptist movement numerically overwhelmed the other Baptist traditions. By 1790, as the new nation began, Baptists had become the largest denomination in the South and joined with the Methodists as the largest denominations in the country. They remained so until massive waves of Catholic immigration from Europe in the middle decades of the nineteenth century propelled Catholicism into first place.

Noted Baptist historian William Lumpkin explained how the Separate Baptist Movement, enormous both in size and energy, “greatly advanced the cause of religion in America and shaped the character of Protestantism in the South.”7 The Separate Baptists

provided the antecedents for the Southern Baptist Convention in such things as their aggressiveness and evangelical outlook, their centralized ecclesiology that was influential in 1845 when Southern Baptists chose their type of organizational structure, and many other aspects, such as their self-conscious attitudes, their hymnody, their lay leadership, many ecclesiastical practices, and their strong biblicism.8

Robert Baker, the doyen of Southern Baptist historians, surveyed the historical record of the period and concluded that

there seems to be a providential element in the mingling of the Separate Baptist distinctives with those of the older General and Particular Baptists in the South. Taken alone, any one of these three large Baptist movements possessed many weaknesses. In the uniting of the three movements, Southern Baptists were prepared fundamentally for the remarkable development that came in the next two centuries.9

“The General Baptists,” Baker explained, “provided emphasis on the necessity for human agency in reaching men with the gospel.”10 They gave Baptists in the South a deep and abiding commitment to doing the work of the Great Commission to go to all men with the gospel witness. The Regular Baptists (the Calvinists) contributed “doctrinal stability and a consciousness of the divine initiative.”11 They were a constant reminder that men can preach all they want, but if God’s Holy Spirit does not convict and call, men are not going to respond. The Separate Baptists embraced “some of the best features of both” and emphasized “structural responsibility” and “the necessity of the presence and power of the Holy Spirit.”12

Ahlstrom, Lumpkin, and Baker all identified in the historical record of the last half of the eighteenth century the emergence of a clear, discernible Southern Baptist theological tradition at least a half century before the Southern Baptist Convention was founded in 1845. This Southern Baptist theological tradition was characterized by a soteriology that John Leland best describes as the preaching of “sovereign grace in the salvation of souls, mixed with a little of what is called Arminianism,” for “these two propositions can be tolerably well reconciled together.”13

This distinctive Baptist soteriology was neither fully Calvinist nor remotely Arminian. It was, and is, different and distinctive from both. It found confessional expression in the New Hampshire Confession, which first declared under “God’s Purpose of Grace” that “election is the gracious purpose of God, according to which he graciously regenerates, sanctifies, and saves sinners; that being perfectly consistent with the free agency of man.”14

This distinctive Baptist soteriology follows the New Hampshire Confession’s declaration that

we believe that the blessings of salvation are made free to all by the Gospel; that it is the immediate duty of all to accept them by a cordial, penitent, and obedient faith; and that nothing prevents the salvation of the greatest sinner on earth except his own inherent depravity and voluntary refusal to submit to the Lord Jesus Christ, which refusal will subject him to an aggravated condemnation.15

The New Hampshire Confession, adopted by the Baptists of that state in 1833, quickly became widely popular among Baptists, North and South, as it reflected a significant shift away from the more Calvinistic eighteenth-century Philadelphia Confession of Faith. With minor revisions, J. Newton Brown, editorial secretary of the American Baptist Publication Society, published it in The Baptist Church Manual in 1853.16 This publication ensured an even wider distribution and popularity for the New Hampshire Confession, direct progenitor of all three versions of the Baptist Faith and Message—1925, 1963, and 2000.

The fact that the New Hampshire Confession, with its distinctive Separate Baptist-inspired soteriology, became “the confession” among nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Southern Baptists is vividly illustrated by the Southern Baptist Convention’s Sunday School Board reproducing that confession in various books.17 Most notable among these was O. C. S. Wallace’s What Baptists Believe, first published in 1913. Wallace, pastor of Baltimore’s First Baptist Church, wrote an article-by-article exposition of the New Hampshire Confession, which was widely circulated in thousands of churches as a study course book. It sold 191,118 copies (in a much smaller Convention numerically) before it finally went out of print after the Baptist Faith and Message (1925) became the Convention’s confession.18

Why did Wallace choose the New Hampshire Confession in 1913? He says it “was chosen . . . because it is the formula of Christian truth most commonly used as a standard in Baptist churches throughout the country, to express what they believe according to the Scriptures.”19 He also pointed out that the recently founded (1908) Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary had adopted the New Hampshire Confession “as a suitable expression of its doctrinal character and life.”20 Wallace did provide for “helpful comparison and study” Southern Seminary’s “Abstract of Principles” as an appendix.21 He further dedicated What Baptists Believe to James P. Boyce, “First President, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary,” and B. H. Carroll, “First President, Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary,” both “MIGHTY MEN in the Kingdom of Christian Teaching.”22 Wallace, by selecting the New Hampshire Confession for the What Baptists Believe’s confession, acknowledged it as the majority confessional statement of the era, with the “Abstract of Principles” as a minority statement.

Why delve into Southern Baptists’ history in such detail? First and foremost, the record must be set straight. Ever since the First Great Awakening, the Separate Baptist Sandy Creek Tradition has been the melody for Southern Baptists, with Charleston and other traditions providing harmony. Southern Baptists are immersed in Sandy Creek. If the average Southern Baptist is “scratched,” he or she will bleed Sandy Creek. Separate Baptists are the stock, and the other traditions, the seasoning in the Southern Baptist stew.

The theological model of election I espouse today I partially caught by osmosis growing up in Southern Baptist churches. I learned it by reading my daily Bible readings, studying my Sunday school and Training Union quarterlies and church study course books, participating in the Royal Ambassador program and Bible drills, and going to church camps. I was led to the Lord, nurtured in the faith, and called to preach in the context of Southern Baptist church and denominational life. This theology, neither Calvinist nor Arminian, was part of the air I breathed, the water I drank, and the food I ate as my soul and spirit were fed and nurtured in our Southern Baptist Zion. I had to leave home and go to college in New Jersey before I knew that some currently living Southern Baptists believed some people could not be saved, as well as discovering other Southern Baptists who believed the Bible had errors and mistakes in it.

So what does this Sandy Creek Southern Baptist believe about election and free will? I believe in election. I do not believe you can put yourself under the authority of Scripture and not believe in election. I further believe that election “is consistent with the free agency of man.”23 I also believe that the New Testament reveals God as dealing differently with the “elect” and the “non-elect.”24

A Suggested Conceptual Model: Congruent Election

So what is congruent election, and how does it differ from unconditional election? Why is congruent election a better model?

If our goal is to preach “the whole plan of God” that we may be “innocent of everyone’s blood” as the apostle Paul declared to the Ephesian elders (Acts 20:26–27), then we should be seeking a biblical theology that is in harmony with all scriptural revelation.

We must seek a conceptual understanding of each doctrine of the faith, including election, that allows us to preach on every passage of Scripture without contradiction, confusion, or hesitancy, and without ignoring some “problem” passages in favor of others more easily harmonized with our particular doctrinal model. The goal should always be “both/and” not “either/or” when it comes to harmonizing Scripture.

If I am going to seek to emulate the apostle Paul’s example to preach “the whole plan of God” and if literally every individual Scripture verse is theopneustos (“God-breathed” or “God-exhaled,” 2 Tim 3:16), then my doctrinal formulation should ignore no Scripture and seek to harmonize all revelation.

My theology should allow me the freedom to preach from Paul’s Epistle to the Romans that those God “foreknew He also predestined to be conformed to the image of His Son . . . and those He predestined, He also called; and those He called, He also justified; and those He justified, He also glorified” (Rom 8:29–30 HCSB). Here the objects of His grace are so secure and certain in their destiny that He can speak of their ultimate heavenly glorification as a past, completed event.

It should also allow me to preach with equal conviction that “God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish but have everlasting life” (John 3:16 KJV) and “the Spirit and the bride say, Come. And let him that heareth say, Come. And let him that is athirst come. And whosoever will, let him take the water of life freely” (Rev 22:17 KJV).

My theology should make me equally comfortable preaching Eph 1:3–5 and 1 Tim 2:3–6. Ephesians declares: “Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, . . . for He chose us in Him, before the foundation of the world, to be holy and blameless in His sight. In love He predestined us to be adopted through Jesus Christ for Himself, according to His favor and will” (Eph 1:3–5 HCSB). On the other hand, in his first epistle to Timothy, the apostle Paul declares that “God our Savior . . . wants everyone to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth” (1 Tim 2:3–4 HCSB). In these verses God’s “desire” for everyone to be saved is thelo, “speaking of a wish or desire that arises from one’s emotions.”25 Wuest explains that the “literal Greek is, ‘who willeth all men’ ” and “marks a determinate purpose.”26 God, Paul reveals, strongly desires that all men be saved and come to an epignosis or “advanced or full knowledge” of the truth.27 The Timothy passage further declares that Jesus gave Himself as a substitutionary atonement, “a ransom for all” (1 Tim 2:6 HCSB).

How do I harmonize these together? Many years ago, when I was teaching theology full-time, I found that one of the best arguments for the existence of God was the “argument from congruity”—what theory, model, or answer harmonizes the most known facts? The Intelligent Design movement illustrates this argument. When one examines the irreducible complexity and intricate balance and design of even primitive, single-cell organisms, an intelligent designer is the answer far more “congruent” with the known facts than the Darwinian theory of evolutionary origins.

Is there a conceptual model for election that fits the entirety of the biblical revelation better than the Calvinist model of unconditional election? I think so—it is “congruent election.”

The Congruent Election Model

Understanding congruent election first requires recognizing that Scripture reveals two different types of election—Abrahamic election and salvation election. Abrahamic election explains how God chose the Jews to be His chosen people (Gen 12:1–3). Salvation election pertains to God’s elective purpose in how He brings about the eternal salvation of individual human beings, both Jew and Gentile, in both the Old and the New Testaments.

Abrahamic election refers to the status of the Jews as a special, chosen people, not to their salvation. Not all the people of the Abrahamic covenant were saved—only those within the covenant people who were also the objects of salvation election and who understood and appropriated in their souls the saving truths taught in the Old Testament’s sacrificial system. These objects of salvation election genuinely looked forward to Christ’s substitutionary atonement on the cross in the same way Christians look back to that one-time propitiatory sacrifice by Christ the Great High Priest.

There was always a saved remnant within the covenant nation, the chosen people (Rom 11:1–10). Such individuals, exemplified by Abraham in the Old Testament and the apostle Paul in the New Testament, were the objects both of Abrahamic election and salvation election.

The first significant difference between Abrahamic election and salvation election is that Abrahamic election refers to special status as a people of God and salvation election refers to eternal salvation. The second significant difference between the two, but related to the first, is that Abrahamic election is a corporate action, dealing with an ethnically and genetically defined people (“the seed of Abraham”), while the objects of Salvation election are individuals from “every tribe, and tongue, and nation.”

In God’s providence He has chosen to explain and reveal His dealings with His people more fully in the New Testament. In doing so, a third difference between Abrahamic (corporate) election and salvation (individual) election has been underscored. As God has chosen to deal with individuals concerning election to eternal salvation in Christ, as opposed to corporate election to the status as a special covenant people, something called “foreknowledge” becomes a prominent factor. God has revealed in the New Testament that salvation election is somehow intertwined with, and connected to, foreknowledge in a significant way (Rom 8:29–30; 1 Pet 1:2).

Indeed, as Paul anticipated Jewish objections to the preaching of the gospel of grace to Gentiles (Romans 9–11), he explained that God always had “a remnant chosen by grace . . . His people whom He foreknew” (Rom 11:1, 5 HCSB)—those such as Abraham in the Old Testament and the apostle Paul in the New Testament, who experienced salvation election as well as Abrahamic election.

I want to suggest as gently as possible (because historically they have understood a lot more correctly than they have understood incorrectly) that the reason Calvinists formulated their doctrine of election incorrectly is they defined their ecclesiology incorrectly. Having failed to discern the distinction between Israel and the church (perceiving Israel as the people of God in the Old Testament and the church as replacing Israel in the New Testament), they were not attuned to the significant differences between the election of Israel (corporate) and the election to salvation (individual) in both the Old and New Testaments. When differences between Abrahamic election (corporate) and salvation election (individual) are as significant as those outlined above, conflating the two differing types of election or assuming they are the same—they are not—is unwise and misleading.

No better illustration can be found of the theological confusion and mayhem caused by confusing Abrahamic election and salvation election than interpretations of Romans 9–11. Whenever objections are raised to the Calvinistic understanding of election, voices are immediately raised, crying, “What about Jacob and Esau?” (cf. Rom 9:11–13). In his Lectures on the Epistle to the Romans, H. A. Ironside explains the difference between Abrahamic election and salvation election and how they should be differentiated, not conflated:

There is no question here of predestination to Heaven or reprobation to hell; in fact, eternal issues do not really come in throughout this chapter, although, of course, they naturally follow as the result of the use or abuse of God-given privileges. But we are not told here, nor anywhere else, that before children are born it is God’s purpose to send one to heaven and another to hell. . . . The passage has entirely to do with privilege here on earth.28

I challenge all interested parties to read Romans 9–11 carefully and think about two types of election, Abrahamic (corporate) and salvation (individual), remembering that “not all who are descended from Israel are Israel. Neither are they all children because they are Abraham’s descendants” (Rom 9:6–7 HCSB). When you view these chapters from that perspective, previous understandings of election are challenged and changed.

God and “Time”

The key to a new and more comprehensive understanding of salvation election is a deeper and more complete understanding of God’s relation to and experience of “time.” While God experiences “time” in the linear time-space continuum or chronological sense as a function of His omniscience and omnipresence, He alone is not bound by its constraints or parameters. Unlike man, God has always existed in what C. S. Lewis termed the “Eternal Now.”29

God has always experienced the totality of time and everything before time (eternity past) and after time (eternity future) as the present. The New Testament scholar Geoffrey Bromiley bases God’s foreknowledge on His omniscience: “Past, present, and future are all present to God.”30 Herschel Hobbs explained it this way: “The foreknowledge of God is based upon his omniscience, or all knowledge. Since the Bible views God as present at all times and all places contemporaneously in his universe, he knows all things simultaneously.”31

Thus God is described as living in the “Eternal Now,” the “present,” and knowing “all things simultaneously.” What if the Bible is telling us in the concept of “foreknowledge” that God does not just know all things that have or will ever happen as if they are the present moment to Him, but that He has, and always has had, the “experience” of all things, events, and people as a punctiliar present moment? That, I believe, is precisely what is suggested by the biblical concept of foreknowledge. From God’s perspective there can never have been a single moment when God has not had the totality of His experience (their acceptance and after, or their rejection and after) with each and every human being as part of His “present” (i.e., eternal) experience and knowledge.

Romans 8:29–30 declares that God “foreknew” individual human beings, and these same individuals He “predestined” and “called” and “justified” and “glorified,” speaking of the end result (far in the future for at least the first official recipients involved) as a settled, past event—which it always has been for God.

“Foreknowledge” (prognosis, noun; proginosko, verb form) by its New Testament usage “in relationship to God” has “acquired an additional content and meaning.”32 Used as it is in Rom 8:29, Wuest concludes that it “means more here than mere previous knowledge, even though that knowledge be part of the omniscience of God.”33

If that additional New Testament usage is perceived as “pre-experience with,” meaning there is no moment in eternity when the sum total of God’s experience with each person was not God’s present, then the pieces of salvation election and the Scripture passages upon which that concept is founded fall into place in a most convincing and congruent fashion.

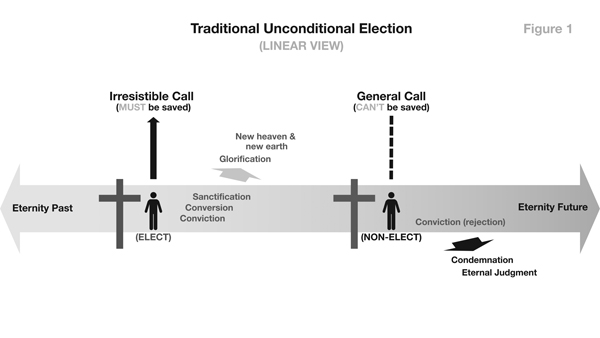

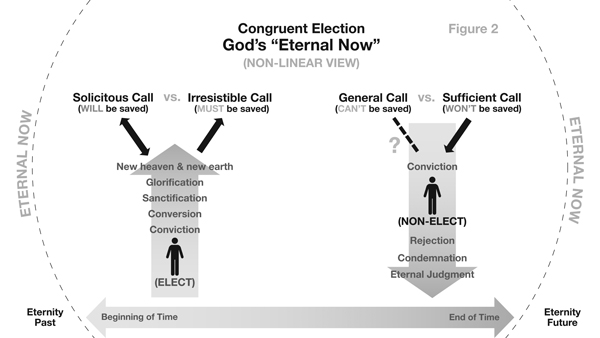

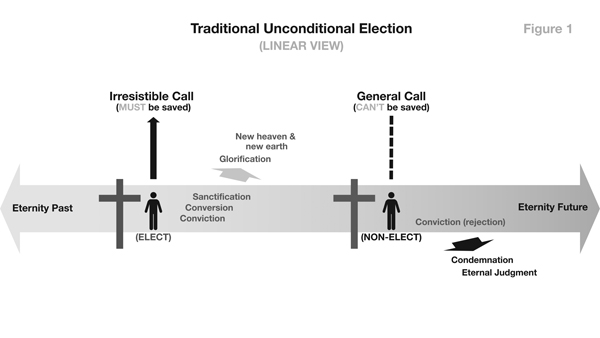

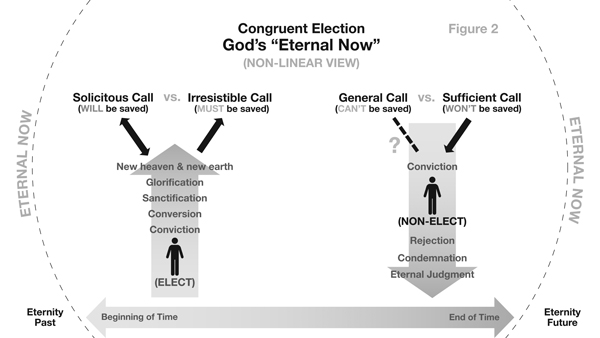

In the old traditional model of unconditional election (fig. 1), the “elect” must be saved because they are the objects of God’s irresistible grace, and the “non-elect” cannot be saved because they are only the recipients of a “general call” (which may or may not involve the Holy Spirit, but which is never sufficient for salvation). According to the Reformed view, from eternity past it has been decreed that the elect must be saved and the non-elect cannot be saved, and it will thus unfold in human history just as God has decreed it.

This view has presented problems to many seeking to exegete such passages as 1 Tim 2:1–6; Rev 22:17; and John 3:16. Scripture affirms “that by God’s grace He might taste death for everyone” (Heb 2:9 HSCB). Giants of the faith have struggled with how the unconditional election of figure 1 is “consistent with the free agency of man.”34 The great nineteenth-century Baptist preacher Charles Haddon Spurgeon, far less optimistic than John Leland, questioned whether Bible teaching on these subjects could ever be reconciled: “I am not sure that in heaven we shall be able to know where the free agency of man and the sovereignty of God meet, but both are great truths.”35

Zoom Image

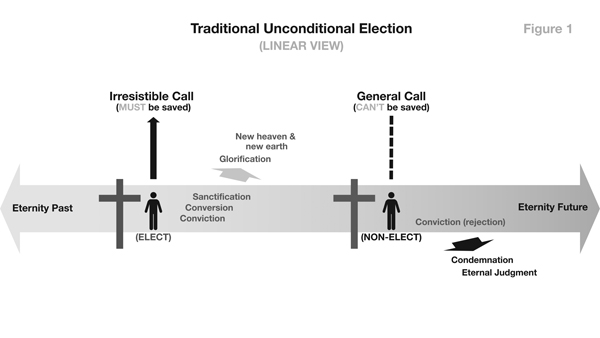

However, if one affirms the belief that foreknowledge means “experience with eternally—from before eternity past and into eternity future,” then congruency of the biblical passages emerges. In congruent salvation election (fig. 2), you have a vertical emphasis, as opposed to the horizontal figure 1. This is to emphasize the punctiliar, “eternal now” aspect of election within in the larger “Eternal Now” concept. If God lives in the Eternal Now, then He has always had not just the knowledge of but experience with every individual. So there has never been a moment in eternity when God has not had the experience of every elect person being convicted, accepting God’s completion of their faith, conversion, sanctification, glorification, and their eternal praise and worship in the new heaven and the new earth.

Conversely, God has always had the experience of the “non-elect”—their rejection of the Spirit’s conviction, their rejection of Him, their increasingly hardened heart, and their ultimate condemnation and eternal judgment. In the congruent election model, while the vertical model symbolizes the simultaneous nature of the totality of God’s experience with the person, elect or non-elect, the linear time represented across the bottom of figure 2 accommodates our need to understand that the events that comprise God’s experience with us occur for us across linear time.

Zoom Image

I had a conversion experience at age six. I was baptized Easter Sunday, 1953. In the years since, I have grown in grace, responded to a call to full-time ministry; and at some point in the future, I will be called home to be with my heavenly Father to worship and praise Him forever. The entirety of that experience has always been part of God’s experience with me while it is still unfolding in space and time.

What an experience it is! Revelation 21:7 reveals God declaring that in the new heaven and the new earth concerning those who belong to Him, “I will be his God, and he will be My son” (HCSB). This is not mere corporate fellowship. This is individual, personal, and intimate relationship with each of us. As His children we will have Him to enjoy and worship personally forever. It lies in the future for us. It has always, eternally been part of God’s experience of us. God’s experience of my response to, and relationship with, Him has always caused Him to deal differently with me than He does with a person with whom God’s eternal life experience has been rebellion and rejection.

Thus, I would posit a distinction between unconditional election’s “irresistible call” (one must be saved) and congruent election’s “solicitous call” (one will be saved). There is a similar distinction to be made for unsaved persons between unconditional election’s (one can’t be saved) and congruent election’s (one won’t be saved). I, for one, see a big difference between “must” and “will” and an even bigger difference between “won’t” and “can’t.”

If God had chosen to do it the way Calvinists say He did, He would still be a merciful and gracious God. If God were merely fair, all men would deserve condemnation. However, the congruent model of election harmonizes the largest number of Scripture passages. Congruent election allows its adherents to preach all the Scriptures on the subjects of foreknowledge, calling, election, and whosoever will.

Congruent election maintains the serious, eternal difference between how God deals with the elect and the non-elect. It rejects the woeful underestimation by some Arminians of the ravaging effects of the sinful nature on the human ability to respond to God apart from prevenient, enabling grace. However, in arguing that the solicitous call to the elect and the sufficient Call to the non-elect, while different, are both sufficient and that both are based upon God’s eternal experience with, not just prior knowledge of, individual beings (and not solely on God’s decree in eternity past), congruent election gives deeper and fuller meaning to God as “fatherly in His attitude toward all men” as the Baptist Faith and Message declares Him to be.36

This, then, is the congruent conceptual model of election. Abrahamic election (corporate) and salvation election (individual) differ from each other in definitive and important ways. Additionally, salvation election, though close to Calvin’s unconditional election indeed differs, since it is based on God’s eternal (present) experience with each human being. I believe God led me to this understanding of election, and it was but a journey of a small distance to this doctrinal destination for a Sandy Creek Baptist. Some would say it was no distance at all.

NOTES

1. J. Leland, “A Letter of Valediction on Leaving Virginia, 1791,” in The Writings of the Late Elder John Leland, ed. Louise F. Green (New York: G. W. Wood, 1845), 172, quoted in S. E. Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 322.

4. Ahlstrom, A Religious History, 322.

7. W. L. Lumpkin, Baptist Foundations in the South: Tracing Through the Separates the Influence of the Great Awakening, 1754–1787 (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1961), 154.

8. R. A. Baker summarizes Lumpkin’s assessment in The Southern Baptist Convention and Its People 1607–1972 (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1974), 56–57.

13. J. Leland, “A Letter of Valediction,” 172. The historical record indicates that the Separate Baptists were giving altar calls for people to respond to the gospel preaching from the 1750s onward.

14. W. L. Lumpkin, “The New Hampshire Confession,” in Baptist Confessions of Faith (repr.; Valley Forge: Judson Press, 1959), 363.

17. J. E. Carter, “American Baptist Confessions of Faith: A Review of Confessions of Faith Adopted by Major Baptist Bodies in the United States,” in The Lord’s Free People in a Free Land: Essays in Baptist History in Honor of Robert A. Baker (ed. W. R. Estep; Fort Worth: Evans Press, 1976), 59–74.

19. O. C. S. Wallace, What Baptists Believe (Nashville: Sunday School Board, Southern Baptist Convention, 1913), 4.

23. H. Hobbs, “God’s Purpose of Grace,” in The Baptist Faith and Message (Nashville: Convention Press, 1971), 64; c.f. C. S. Kelley Jr., R. Land, and R. A. Mohler Jr., The Baptist Faith and Message (Nashville: LifeWay, 2007), 77.

24. Rom 8:29–30; Eph 1:3–6; 1 Pet 1:2.

25. K. S. Wuest, The Exegesis of I Timothy, in Wuest’s Word Studies from the Greek New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1973), 2:40.

28. H. A. Ironside, Lectures on the Epistle to the Romans (Neptune, NJ: Loizeaux Brothers, 1928), 116.

29. C. S. Lewis, Miracles (New York: Macmillan, 1947), in The Best of C. S. Lewis (ed. H. Lindsell; Washington, DC: Canon, 1974), 375. J. Cottrell discusses eternal concepts of time in relation to God in his article “The Classical Arminian View of Election,” in Perspectives on Election: Five Views (ed. C. Brand; Nashville: B&H, 2006), 112–15, but draws significantly different conclusions than the ones proposed in this article.

30. G. W. Bromiley, “Foreknowledge,” in The Evangelical Dictionary of Theology (ed. W A. Elwell; Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1984), 320.

31. H. Hobbs, What Baptists Believe (Nashville: Broadman, 1964), 24.

32. Wuest, Studies in the Vocabulary of the Greek New Testament, in Wuest’s Word Studies, 3:35.

33. Wuest, Romans in the Greek New Testament, in Wuest’s Word Studies, 2:144. See also Wuest, First Peter in the Greek New Testament, in Wuest’s Word Studies, 2:16.

34. “The New Hampshire Confession,” in Baptist Confessions of Faith, 363; “God’s Purpose of Grace,” Article 5 in the Baptist Faith and Message 2000, cited in Kelley, Land, and Mohler, The Baptist Faith and Message, 77.

35. C. H. Spurgeon, The Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit (Pasadena, TX: Pilgrim Publications, 1978), 51: 50, quoted in Kelley, Land, and Mohler, The Baptist Faith and Message, 77.

36. This quote has been taken from Article 2a of the Baptist Faith and Message 2000, “God the Father,” which reads as follows: “God as Father reigns with providential care over His universe, His creatures, and the flow of the stream of human history according to the purposes of His grace. He is all powerful, all loving, and all wise. God is Father in truth to those who become children of God through faith in Jesus Christ. He is fatherly in His attitude toward all men”; cited in Kelley, Land, and Mohler, The Baptist Faith and Message, 31.