13 / Record Keeping

A Post-Hermeneutic Means for Charting the Space of Flows

AS DE VRIES NOTED, LARGE BREEDING EXPERIMENTS required immense record keeping. It is much too easy to overlook this development when evaluating the history of genetics. The extensive use of purebred laboratory organisms with quick breeding times hides the amount of work required to identify the passage of traits in a more diverse slow-breeding population such as humans. This is work that could not be undertaken without extensive divisions of labor and the latest in recording technologies.

It is not surprising, then, that the best example of the application of record-keeping innovations to the study of human heredity is Charles Davenport's Eugenics Record Office at Cold Spring Harbor. Davenport's task was mammoth. He needed to assemble the fragments of family secrets and stories into a rich enough pedigree that researchers could follow the inheritance of unit characters. Davenport's dream was to apply recent innovations in record keeping to the analysis of extended family pedigrees. It was to this end that he ran the Eugenics Record Office at Cold Spring Harbor and supplied it with the most up-to-date office equipment. Davenport describes its founding:

In October, 1910, The Eugenics Record Office was started at Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island, N.Y., in connection with the Eugenics Section of the American Breeders' Association in a tract of 80 acres, with a good house to which has been added a fire-proof vault for the preservation of records. Mr. H. Laughlin is its superintendent. At this place the collecting and cataloguing of records goes on apace. It is hoped to establish here a very completely indexed collection of published genealogical and town histories for the United States as well as the manuscript reports of the field investigators.1

Humans are slow breeders who have few progeny. Informal experience allows for the observations of three, perhaps four, generations of phenotypic description. The gathering of any more data, to extend the event horizon to more generations, requires the gathering of recorded observations of past generations or stories of distant relatives. Collecting, amassing, and organizing these observations was a Herculean task. Henry Laughlin, of the Eugenics Record Office in Cold Spring Harbor, implies this in his 1911 statement:

The Record Office has begun a cross-reference index of the names, traits, and localities included in the data received. It is believed that this index will be useful in tying together fragmentary pedigrees and tracing back to the earliest ancestor significant hereditary traits. The office is now prepared to index any material, no matter how fragmentary or how extensive, concerning the transmission of biological traits in man; and it seeks to become the depository of such material.2

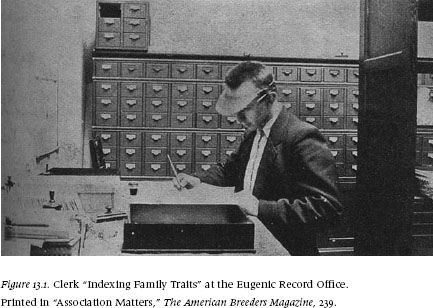

Although we currently think of cross-indexing as a mundane activity, this practice was crucial for those trying to find associations in large amounts of information. Just the fact that this practice is mentioned and highlighted in a photograph (see figure 13.1) is key for understanding how central it was for the overall project of the Eugenics Record Office. The hope in compiling this information was to establish a clearinghouse of information on the germplasm, which would help researchers view the complex inheritance patterns of a slow breeding organism that remained mostly hidden to the unaided eye. “By the nineteenth century the collective memory had expanded to such proportions that the individual memory could no longer be expected to store the contents of whole libraries,” wrote the structural anthropologist Leroi-Gourhan in his classic study Gesture and Speech. “The eighteenth and part of the nineteenth century had still made do with notebooks and catalogs. These methods were succeeded by the card index, which did not begin to be properly organized until the early twentieth century.” “A simple set of bibliographic index cards will lend itself to many adaptations in the hands of its user.… This is still more obvious in the case of card indexes containing scientific information, where each documentary component can be arranged at will in relation to all other components.”3 Filing allowed a release from the chronological linearity of the notebook. According to JoAnne Yates, “The flexibility of vertical files allowed companies to abandon the chronology of the press book in favor of a more functional arrangement. They still had to decide, however, which arrangement was more functional. ”4 Revealingly, eugenicists at this time decided upon family, location, and occupation as filing categories before settling on more purely physiological functionalities.

Obtaining such a large collection of pedigrees required the training of a large workforce for securing the data, the use of standardized forms for correlating the data after they were secured, and a list of terms for cross-indexing the correlations. All of these innovations were first found in large corporate structures where they were important for coordinating successful corporate operation. It is no coincidence that the list of cross-indexed terms was the same list as that for unit characters. These were thought to be the traits, after all, that connected humanity in all its variations. Why not use these traits to connect the data that described these connections? One of the most intriguing documents published by Davenport is his 1911 list of traits, called simply The Trait Book, with the accompanying numerical index he distributed to his collectors. A seemingly benign list of filing terms, these indexes were thought also to be the cornerstone for describing the unit characters important in human inheritance (see figure 13.2).

The historical insight provided by this little book is immense. The book elegantly presages my earlier arguments on the rise of genetics as a metadiscourse on human experience. In Davenport's book we see the unit character emerge as a higher-ordered system for describing human relationships with mass communications and corporate structures. From this perspective, genetics is a symbolic shorthand for all those environmental interactions that were only concatenated into long strings of observations in the panoramic mode. The embodied experiences of the panoramic mode had not disappeared; they just remained tucked away from view in a series of properly indexed and cross-referenced file folders. When enough of these folders are assembled, the indexical tags create a whole new conceptual space from a clearinghouse of information. Geneticists call this space the genome. Genes are therefore real and informational entities. As such they are relational entities. On the one hand, they are biological structures with a material basis (although defining the discrete nature of this basis is still difficult); on the other hand, they are a symbolic shorthand of human experiences of space accrued through the application of the tools and practice of managerial capital.

The value of this perspective comes home when evaluating the types of traits that Davenport studied. Working at a time when the phenotype/genotype distinction was just being conceptualized and understood, and thus before the role of the cytoplasm as an internal environment (often conceived of as a sort of homeostatic buffer for the nucleus) was established, Davenport appealed to the functional definitions of society, and not the functional dynamics of the cell, for the indexical terms to describe human experience.5 As figure 13.2 demonstrates, these designations unabashedly reflected the concerns of a rapidly industrializing society. Occupations in an industrial society, such as “messenger boys,” were considered an index for a biological character and given a number where each digit indicated the relation of this character to others in the list. One could easily pronounce Davenport confused about the nature of biological “function” at the cellular level. However, to do so would be to miss the lessons about this important transitional state in the adoption of Mendelism. Individuals such as Davenport had to train themselves to think in terms of the new spatial dynamics of latent characters. Others would clarify the conditions that were needed to envision these phenomena in a persistent and repeatable fashion. This would involve the adoption of two new spaces: the material space of the laboratory (which minimized the importance of environment, or “place,” in interaction with the organism) and the conceptual space of record keeping (which allowed for the documentation of heritable continuity, and thus the categorical description of variance).

Recent scholars have not hidden their contempt for the goals, methods, and results of Davenport's project.6 But we should not let these contentions diminish our insight into the importance of Davenport's faith that these new innovations would turn up interesting results. This promise is only made much more intriguing by the inability of the data-processing techniques of the time to live up to this hope. This dream was a common one for progressive institutions. Hidden under the call for more efficient institutional practice was a seemingly naïve belief that record-keeping practices were sufficient to achieve these efficiencies. Take, for example, Davenport's dream of setting up a “clearinghouse” of family histories. The clearinghouse was a form of data repository that promised new economies of scale by serving as a hub that would hook together the data with those who needed the information. The patron for Davenport's Eugenic Institute, Mary Harriman, wife of industrialist and trotting-horse breeder E. H. Harriman, also supported a philanthropic clearinghouse that sought to bring together those with money for projects with those who sought to better themselves by making themselves more efficient.7 This form of clearinghouse is roughly analogous to what we would call a database, or more traditionally a library, in the sense used by Walter Benjamin .8 One interesting thing about these extended forms for storing information is that they remain useful as long as they are not limited by the capacities of a single user and as long as one can chart multiple pathways through the data. The data then move from being a description of the action of a single individual through space and time (as in most narratives) to a repository of many different descriptions of individuals. If this repository is rich enough, and the ability to play back the information exists, it can allow for the emergence of previously unseen correlations and become a source for the discovery of new things, or surprises.

We see a similar move toward extensive documentation practices in many of the experimental breeding stations at the time. According to De Vries, it was the extensive records that the Svalöf station kept that allowed them to make sense of surprising observations. The most important of these observations involved the recognition of the significance of purebred cultures. In the past, farmers had saved a portion of the seed stock from the whole crop and then replanted this portion. According to De Vries researchers at Svalöf practiced this method of gathering seed until

an accidental observation was made which at once changed the whole aspect of the question. Some few cultures were discovered among the thousands which bore only one type. They were as uniform as the remainder were heterogeneous. Concerning the initial choice of the samples, an elaborate record had been kept, and this enabled Nilsson to discover the cause of the purity of these exceptional cases.9

Extensive record keeping allowed researchers to play games with time by allowing for a surprise observation. Not all knowledge in science proceeds from these surprises but keeping records beyond previously determined needs allows a researcher to harness the unexpected. This is especially true of any procedure where one expects results for rare and discontinuous events, such as De Vries's conception of mutation. Record keeping extends an event horizon in order to recognize rare occurrences; it does this, notably, by narrowing the focus of enquiry and abstracting experience as symbols.

Organizing a large collection of data demands finding a way to compare data from different lots. A standard of comparison had to be implemented. This meant initiating standardized practices in trait recognition and record keeping. Perhaps the most important change was the replacement of formal descriptions with measurements. According to De Vries, “instead of the personal appreciation of the qualities of the ears [of grain],” researchers at Svalöf adopted “accurate measurements.” “The length of the ears was given, their form indicated by width and breadth, and by the place where both reached their maximum value. The density could be measured by the number of nodes and spikelets, and in the latter, the number of single kernels could be noted. Other valuable qualities required separate tools and instruments, and even the degree of brittleness had to be expressed by figures.”10 This not only allowed for easy comparisons across generations and across experimental plots (not to mention from researcher to researcher), it was the cornerstone of detailed recording practices for industrial-sized experiments. Elaborate collections of prose descriptions were just too bulky to be of use in such large experiments. “An elaborate book-keeping required the statement of a large number of qualities by short indications, and figures came to be preferred to descriptions.”11 In order to be useful, these records had to be extensive enough to track observations that one could not anticipate. This meant using the abstractions of measurement and symbolic descriptions to track all phases of growth and development of individual plants. De Vries even notes that at Svalöf “the book-keeping embraces the complete botanical description of each new sort, from its germination until the time of the harvest, with all the details required for the controlling of its constancy and uniformity and for the study of all those qualities upon which the production into general agriculture will ultimately depend.”12 These records, in a sense, were the compilations of many life histories in a condensed form based on the functional criteria of industrial values.13

In order to be fruitful, a compilation of life histories needed to designate how each could be easily accessed and correlated in relationship to each other. “From its first isolation each culture is designated by a number, which it retains until it is abandoned or until it is judged worthy of introduction into commerce. Then, of course, the number is replaced by an ordinary name, as quoted above.” Each numeral indicated to researchers precise information on the initial group from which the ear was isolated, and any special type selected because of an important variant characteristic. De Vries reports: “The book numbers at Svalöf consist of four figures, the first of which is a zero, which is prefixed to avoid all confusion with other numbers. The second figure indicates the group and the two remaining ones relate to the special sort. So a dwarf Ligowo oats is called 0313, and another kind of Ligowo oats which was afterward recommended as Svalöf Ligowo, bore the number of 0353. ”14 Keeping track of enough varieties successfully to identify and follow variant characteristics with even this condensed numerical nomenclature required an incredible amount of work:

The amount of this book-keeping is almost incredible. In the year 1900, some 2600 numbers were in culture.… To these numbers must be added 138 comparative cultures of races almost ready for introduction into the trade, and among these only twelve older ones were found,… Further, the bookkeeping was increased in the same year by 431 numbers afforded by the progeny of mother plants which had been selected anew in the fields during the preceding season.15

This level of detail allowed researchers to follow the “selection of individual ears or panicles” as opposed to the “selection of samples.”16 This form of selection practice would later come to be known as pedigree or “pure culture.” Older sampling techniques were mostly mixed “from multiple samples” and were more of a selection “of groups or of families, and could even appropriately be denominated selection of crowds, an expression which would at once convey the idea that the terms of selecting simultaneously more than one individual are intrinsically contradictory. ”17 In De Vries's estimation, this mixed form of selection often practiced by horticulturalists should not be considered selection at all.

Selection at the level of the individual was also important because it allowed for the designation of specific traits at the level of the individual as well. For instance, measuring the starch content of a specific pureline of cereal is different than measuring the formal qualities of a “mixed” sample. With the mixed sample the amount of variance is increased, thus making descriptive accounts based on an evaluation of overall form more suitable. In pureline cultures variance is reduced, allowing for the more immediate application of numerical techniques. In most recent studies of the history of heredity, this atomization of the individual and the reliance on measurable criteria is often seen as an example of the reductive dimensions of genetic discourse. Although this is true, it is much too limited a conception of genetic understanding. An important first step for recovering the complexity inherent in genetic discourse is to ask, “what exactly does this conception of living beings reduce?” Modern conceptions of genetics are primarily concerned with how organisms operate and are constructed, while genetics began as a discourse for thinking about how individuals are related. Originally this had operated solely through more formal and discursive evaluations (notions of class and occupation; conceptions of place and of development and evolution). The adoption of standardized terminology, the use of standardized forms and categorical descriptors, the atomization of the individual into unit characters, and the extensive appeal for a means of cross-referencing, however, allowed characterizations to be made between individuals. It was only after the phenotype/genotype distinction had been firmly established that genetic discourse turned from an agricultural model that sought how organisms were related to a physiological model that sought how organisms functioned.18

It is this emphasis on figuring out “the key elements that individuals shared in common” that stamps classical genetics as the modernist science of “mass culture.” That it did so by appealing to a “lowest” common denominator in its efforts to establish a unified perspective from which to view and exploit these connections marks it as more similar to other turn-of-the-century developments in transportation and communication. For example, newspapers at the time were appealing to a whole new set of featured novelties (such as the printing of colored comic strips) and journalistic practices (such as sensationalized investigative journalism) that would guarantee them the widest possible audience.19 This search for the lowest common denominator was also a product of establishing new markets with new immigrant populations. New spatial practices helped substantiate novel forms of connectivity. They did this, however, by using standardized record-keeping practices to find a lowest common denominator.

That researchers of the time started with the most predominant elements of that culture (functional descriptions prevalent in an industrial society) is not surprising. Scientists applied distinctions they had at hand at the time, in the same way that scientists do today. They had only begun to integrate laboratory studies into the practice of genetics, and thus the right “tools for the job” were taken from agricultural and business practices and not the benchtop. It is only with a second generation of classical genetic research (such as Boris and Ephrussi's linking of genetics to enzymatic pathways) that the physiochemical tools were applied.20

Finally, an analysis of the rise of mass culture and the tools of information processing sheds new light on the enigma of Luther Burbank. Although Burbank was very good at utilizing the networks established by industrial infrastructures to secure samples, and he was extremely good at developing shortcuts to “scale up production” in order to find the rare hybrid that met his needs, he paid little attention to keeping accurate records. This made retracing how he identified his novelties difficult. In a lengthy report, academic scientific breeder George Shull complained at length about Burbank's inability to maintain proper records. E. Carleton MacDowell, in an unpublished history of Shull's Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, summarized Shull's Carnegie report in the following terms: “Burbank's so-called records proved utterly useless. The information was in Burbank's head; to get this recorded, he would have to dictate answers to Shull's questioning. No facts of direct scientific use could be expected.”21

This did not mean that Burbank did not keep records. He did. Burbank kept both business records and plant records. In his business records he kept track of his own personal accounts through a running savings account balance and a ledger that documented individual orders and whether he had received payment for these orders. For his plant records, Burbank kept a register of the seeds he received, roughly drawn garden plans, and descriptions of many of the plants he deemed worthy of continuing to propagate. These plant descriptions are especially interesting. Burbank would take a fruit, cut it in half, and stamp it on a piece of paper. He would then give the plant an overall evaluation based on a series of cross hatches. Each evaluation was a description of the formal characteristics of the whole plant (such as taste, smell, keeping qualities, and appearance) as opposed to an evaluation at the level of the unit character. He would then take these descriptions and make lists of comparisons (see figure 13.3). Although unit characters could be examined in overall evaluations, the lack of detail in these evaluations would not travel well from researcher to researcher. Even more importantly, a cross-indexing system, which would allow one to trace single characters across generations and lots, could not be established. The evaluation of the character remained subsumed to the evaluation of the formal qualities of the plant as a whole, emphasizing the plant's relationship to its environment. For other plants, Burbank's recording methods were even less useful. Instead of recording his results on paper, Burbank would mark the plant directly with strips of white linen (he called them “neckties”) that set out a specific plant or bud-growth in relief from its neighbors. Burbank would then choose from these the plants that he cared to raise for the next round of selection. The problem was, of course, that no one had retrospective means for evaluating why this plant had been chosen once the other plants had been destroyed. Most significantly, there was no overall explanatory key for interpreting Burbank's records. This precluded other researchers accessing Burbank's data, and it demonstrated Burbank's operating assumption that individuals other than Burbank lacked a refined enough sensory apparatus to understand his evaluations. Shull was clearly frustrated by this in his report: “It will be seen from these descriptions and extracts from the several note-books, that there is very little indeed that can be looked upon in any sense a scientific record, though it is clear that they served the purpose for which they were made, namely to aid Mr. Burbank's memory in recalling the history and the location of his plants.”22

As other scholars of modernity have demonstrated, geneticists were not the only ones using developments in recording technologies to play games with time during this period. Media theorist Friedrich Kittler has recently argued that the widespread use of electromechanical recording technologies led to a “post-hermeneutic” understanding of subjective experience. From this perspective, interpretation of experience became less important than recording experience because recording technologies reconstituted elements of experience that escaped interpretation.23

Standards have nothing to do with Man. They are the criteria of media and psychophysics, which they abruptly link together. Writing, disconnected from all discursive technologies, is no longer based on an individual capable of imbuing it with coherence through connecting curves and the expressive pressure of the pen; it swells in an apparatus that cuts up individuals into test material.24

In a sense, to be “modern” meant to suspend one's inherited interpretive framework in order to identify an underlying structure that could make sense of the many different perspectives for understanding the world.25 Technologies were often thought to supply this underlying structure. In the biological sciences, according to Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison, this led to an interpretive practice that privileged “mechanical objectivity” over the interpretive authority of the scientist.26 Under this conception, truth had to be recorded before meaning could be discerned. Or, to use a concept that I developed in chapter 11, these were the interpretive practices of memory 2, of meaning-making and the rise of industrialism.

Burbank is remarkable for his inability to document his explorations of the circuit of memory 2. Burbank used whatever records he had as a set of marks to aid his memory and not as a distinct informational entity containing the interpretive codes for understanding this information. This was a form of meaning with circuits primarily involving the object and the subject as opposed to the subject and object being a condition of the infrastructure (“memory 1” as opposed to “memory 2”). For instance, with the numbering system at Svalöf, a researcher could easily tell what lineage and what variant he or she was working with. With Burbank's system, one needed to appeal to Burbank's memory to receive comparable information. As Daston and Galison suggest, new representational practices helped standardize the observing subject and the observed object “by eliminating idiosyncrasies—not only those of individual observers but those of individual phenomena.”27 It is important to pause to fully explicate what is at stake in this case. Burbank, in a sense, was still operating from the interpretive presuppositions of a pre-mass-distribution culture. Standardized information allows for the dissemination of information to many parties without the intervention of an interpreter.

Burbank's work remained at the level of the recapitulation stories we covered in Part Three. They could provide a framework for the experiences Luther Burbank had while working in his garden; they could even help stimulate Burbank's memory through the use of mnemonic devices such as the plants' neckties. They could not provide the necessary codes for understanding the garden environment without the presence of Luther Burbank, however. Shull summarizes it thus: “The difficulties in the way of the direct utilization of his plants for scientific study are very great. It is very rare that he has on hand at one and the same time, the material of any species with which he began, and the finished results of his hybridization and selections, so that the comparative studies could not be satisfactorily made.”28 For the practitioners of the new informational practices, nature needed to “write herself” without the aid of an interpretive agent. In short, standardization allows information itself to become the wandering subject.

The problem with Burbank's records, it seems, was not only the records but also Burbank himself. One might say that Burbank still operated by the hermeneutic codes of the panoramic mode where there was no need to identify interpretive frameworks outside of the dynamic subject that linked together vastly new experiences of space and time. Even though he utilized industrial networks and systems of operation to produce his plants, Burbank was both recording device and interpretive apparatus. Thus only Burbank himself could make sense of this world. Burbank had even come to think of himself as “exquisitely sensitive” with highly refined senses, and this then allowed for him to discern characters in plants that others may not. Although this self-description may or may not be accurate, such acute sensitivity could not bring about the changes in scale needed to discern unit characters in living organisms.

Another indicator that Burbank still viewed life panoramically is his conception of the mechanics of hybridization. For Burbank, time was still subsumed to spatial experience. Hybrids were reflections of a specific place. The actions of time could not be productive in and of themselves; they could only reinforce the primacy of spatial experience. This is apparent in Burbank's fascinating use of the metaphor of photography for understanding the relationship of a plant to a specific location.

You know that the camera plate is struck with blows of light to burn into the sensitized surface the picture you want to take. If you make what is called a time exposure the blows are gentle, but sooner or later they make a dent in the gelatine. The lighter parts are burned deeply, and the shadows and black places are only just touched. But it is the steady tap, tap, tap of the rays of light that do the work.29

In this quotation, time is working as an aide to elicit “place” in a logic of a sequence—it is not considered an irreducible emergent element of experience, and thus is more akin to what I have called “memory 1.” Interestingly, the photographic analogy that would best explain a Mendelian, or memory 2, conception of heredity, would be the experiments undertaken by Stanford and Muybridge, which I discussed in Part One, for these allowed one more directly to visualize time as an irreducible variable.30 It is only through the detailed observation of time (in this case the apparent stopping of time) that we can then come to contemplate the passage of time as a quality of the world independent of space.

Gilles Deleuze's cinema studies provide a useful account of the importance of this change. Deleuze organizes his study into two types of film images: “the movement image” and “the time image.”31 The movement images of early films sought to convey time indirectly through the dynamics of a moving subject. The time image, on the other hand, used special techniques like montage to collapse space and give a sense of time independent of movement. In the time image “the only subjectivity is time, non-chronological time grasped in its foundation, and it is we who are internal to time and not the other way around. ”32 Time is no longer dependent on movement; now movement would be dependent on time. Though I concur broadly with the separation of time from space that Deleuze describes, I differ from him in my understanding of recording technologies. For me, recording technologies must also include detailed record keeping with an indexical component. This would be a cross-referencing system that could use higher order processing newly to fold the linking between space and time. In scientific practice, this means using a filing cabinet as well as a diary or laboratory notebook. In representational practice it means adding a type of descriptive practice not predicated on the dynamics of narrative, such as illustrations or graphs and the numerical processing used in statistical techniques. This is exactly the conceptual advancement that De Vries offered with his mutation theory. It was a way to think of genetic change as a product of time irreducible to spatial experience.33

The “wizardry” of Burbank then lay chiefly in a mismatch between applying the tools of industry to product development and relying too heavily on older forms of record keeping. This position was justified by the spatial practices of the panoramic mode, which upheld the sense-experience of the single individual to be the larger-than-life interpretive apparatus for a whole new flow of experiences enabled by mass production. James Beniger puts this observation into the context of the importance of record keeping for business that worked on industrial scales:

What made the Control Revolution truly revolutionary was that, for the first time, distributional and control systems including information processing, programming, and telecommunications could be sustained indefinitely on a global basis. Industrialization became revolutionary when the energy harnessed vastly exceeded that of any naturally occurring or animate source; the resulting throughput and processing speeds greatly exceeded the capability of unaided humans to control. What made the Control Revolution in fact revolutionary was the development of technologies far beyond the capacities of any individual, whether in the form of the massive bureaucracies of the late nineteenth century or the microprocessors of the late twentieth century. In all cases it was not the novelty of the commodities processed (whether matter, energy, or information) that proved decisive, contrary to Bell, but rather the transcendence of the information processing capabilities of the individual organism by a much greater technological system.34

Burbank had produced the novel commodities. What he lacked was the development of a system that allowed for the control, reproduction, and verification of these novelties. Without this, Burbank remained a “wizard” or a “charlatan,” without the means to document the new space of connectivity wrought by an industrialized society—a space we now call classical genetics.