CHAPTER 6

Managing Process Improvements

Understanding processes so that they can be improved requires the application of basic methods, practices, and approaches. These, in turn, require that an appropriate organizational structure exists that can guide improvement efforts and ensure that activities are managed in a meaningful and harmonious manner. This includes tools for individuals who operate processes, those who manage and execute Process Improvement initiatives, as well as leaders who guide the enterprise and prescribe strategic imperatives and policies. This chapter outlines the components that make up a Process Improvement framework and the relationship of Process Improvement to strategic planning efforts. It discusses several methods that are used to conduct Process Improvement and provides a concrete model for discussing, implementing, and assessing the practice of continuous Process Improvement within a team or organization to meet growing customer demands. This chapter is organized around the following ten topics:

• Process Improvement Framework: What is a framework? What are the various components that make up a comprehensive Process Improvement Framework?

• Environmental Factors and Organizational Influences: What internal and external environmental factors surround or influence Process Improvement efforts?

• Organizational Profile: What is an Organizational Profile? How can it assist with assessing an organization’s environmental factors?

• Leadership: What role does leadership play in Process Improvement activities?

• Strategic Planning: What is the definition of Strategic Planning? How does Hoshin Planning assist with these efforts?

• Process Management: What are the various Process Improvement methodologies? When should each methodology be used?

• Performance Management: What is Performance Management and how does it benefit an organization? How is performance monitored and communicated?

• Workforce Management: What is Workforce Management? What tools can be leveraged to effectively manage an organization’s people?

• Quality Management: What is Quality Management? What defines a quality-focused organization?

• Knowledge Management: How is Knowledge Management defined? What tools are used to realize the benefits of Knowledge Management?

Process Improvement Framework

Since Process Improvement requires simultaneous changes in the process system, technical system, behavioral system, and management system, implementing a Process Improvement philosophy is a continuing and long-term goal. It can deliver results quickly, but can also take longer periods of time before becoming a core aspect of an organization’s culture. Implementing a cohesive Process Improvement framework is a means of guiding organizations toward truly engraining Process Improvement in all aspects of operations.

In general, a framework describes the rationale of how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value. It is a structure intended to guide or steer an organization toward building particular practices or philosophies into its culture and operations. It provides a broad overview or outline of interlinked items such as strategies, tactics, and methods that support a particular approach and serves as a guide that can be modified as required.

Ten categories are involved in building a culture of Continuous Improvement and define the Process Improvement framework. These categories are placed together to emphasize the importance of aligning organizational strategy with customers and environmental factors. They also illustrate how an organization’s workforce and key processes accomplish the work that yields overall performance results. Each element is critical to the effective management of an organization that wishes to continually improve performance and competitiveness. Figure 6-1 depicts the ten basic elements of the Process Improvement Framework.

FIGURE 6-1 Process Improvement Framework

Within the framework, all actions point toward results, which is a composite of environmental (action 1), management (actions 2, 3, 4), and workforce (actions 5, 6, 7, 8, 9) results. The larger two-headed vertical arrow in the center of the framework links the management triad to the workforce quintet, which is the linkage most critical to organizational success. A management team that works closely with its workforce ensures that employees are engaged, aligned, and informed. The larger single vertical arrow indicates the central relationship between the workforce and results, as the workforce is paramount in achieving organizational goals. All other arrows in the framework are two-headed arrows that indicate the importance of continuous feedback in an effective performance management system.

Environmental Factors and Organizational Influences

Enterprise environmental factors refer to both internal and external factors that surround or influence an organization’s, a department’s, or a project’s success. These influences may come from multiple categories or entities, can enhance or constrain improvement efforts, and may have a positive or negative influence on an organization’s activities. Example environmental factors and organizational influences include

• External driving forces: Customer, Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Legal, Regulatory, Marketplace, Shareholder, Media, Infrastructure (e.g., government or industry standards, regulatory agencies, codes of conduct)

• Internal driving forces: Culture, Structure, Processes, Communication Channels, Resourcing (e.g., staffing guidelines, training and skills, knowledge, employee morale, facilities)

Despite efforts to assess any and all environmental influences, disasters, economic shifts, and other unforeseen events, these negative factors can affect an organization at any point in its strategic road map. To the extent that they can, organizational leaders should be observant of the potential for unexpected environmental impacts and put contingency plans in place to ensure the least possible negative impact on the organization’s success.

Organizational Profile

An Organizational Profile provides a high-level overview of an organization’s environmental factors and influences. It addresses an enterprise, a department, or a project; its key relationships; its competitive environmental and strategic context; and its approach to improving performance. It also provides critical insight into the key internal and external factors that shape an organization’s operating environment. These factors, such as the corporate vision, mission, core competencies, values, strategic challenges, and competitive environment, impact the way an organization is run and the decisions it makes. As such, the Organizational Profile helps organizations better understand the context in which they operate; the key requirements for current and future business success; and the needs, opportunities, and constraints placed on the organization’s management systems.

Super System Map

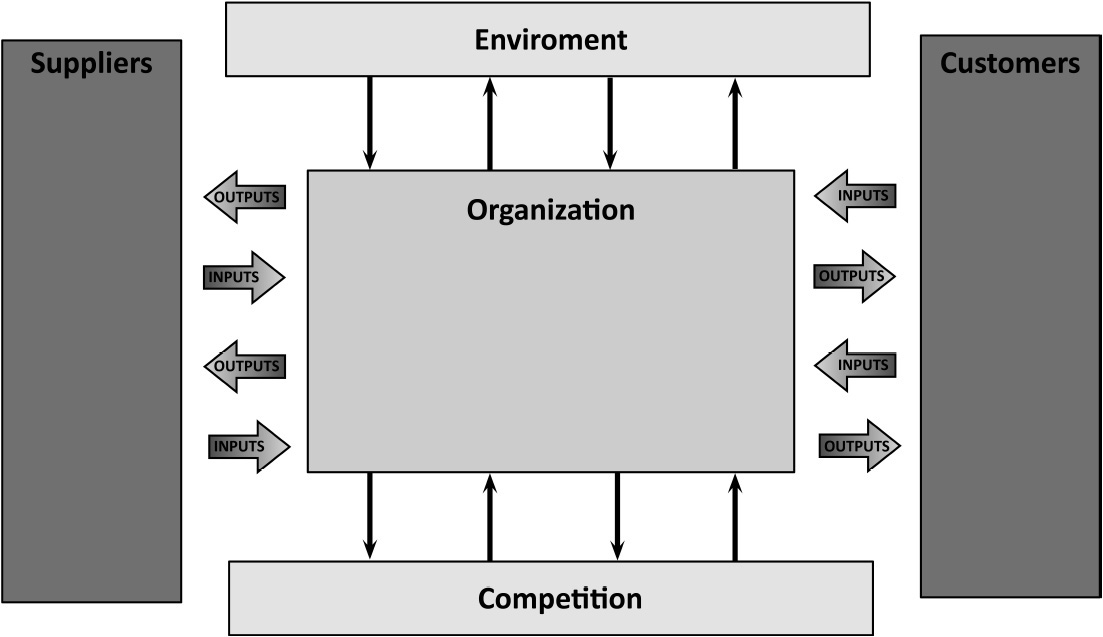

Among the most widely used tools for creating an organizational profile is the Super System Map developed by the Rummler–Brache Group. The Super System Map is a picture of an organization’s relationship to its business environment and helps to understand, analyze, improve, and manage these relationships. Management teams use this diagram to perform systematic strategic reviews. This is done by working through all key components of the organization’s operating environment in order to analyze its current state and predict future scenarios. It can help to make strategic thinking more visible and can communicate a common view of the enterprise to all employees and stakeholders.

The Super System Map includes the following six key components, which are discussed in the following paragraphs:

• Organization

• Customers

• Suppliers

• Competitors

• Environmental influences

• Shareholders/Stakeholders (if applicable)

In addition to each component listed above, the map shows the organization’s relationship with these components. These are displayed as arrows that show the flow of key inputs and outputs, including products, services, money, people, regulations, and information. Figure 6-2 depicts a basic Super System Map Template.

FIGURE 6-2 Super System Map

Organization: This box addresses the key characteristics and relationships that shape an organization’s environment. Often populated with purpose, vision, mission, values, or core competencies, this section provides a clear understanding of the essence of the organization, why it exists, and where senior leaders want to take it in the future. This clarity enables leaders to make and implement strategic decisions that will affect the organization’s future and its processes. Examples of other information placed in this section include Organization Charts, Hoshin Kanri information, and Business Plan information.

Suppliers: In many organizations, suppliers play a critical role in processes that are pertinent to running the business and to maintaining or achieving a sustainable competitive advantage. There is often a significant or complex give-and-take relationship between a supplier and an organization, and documenting these relationships and understanding their complexities helps to ensure positive business outcomes. Suppliers listed in this section may include staffing providers, Information Technology (IT) suppliers, professional service providers, supply chain partners, outsourced services, research firms, and lending institutions.

Competitors: This box provides an understanding of who an organization’s competitors are, how many there are, and their key characteristics. It is essential to list and document competitors in order to determine an organization’s competitive advantage in the industry and marketplace. Leading organizations have an in-depth understanding of their current competitive environment, including the factors that affect day-to-day performance and factors that could impact future performance. Types of competitors that may be listed in this section include Traditional (same products, same markets, mature), New (new and growing), Emerging (disruptive technology, lurkers).

Environment: The environment in which an organization operates (regulatory or otherwise) places requirements on the organization and its processes and impacts how business is run. Understanding the organization’s environment helps with making effective operational and strategic decisions. It also allows organizations to determine whether they are merely complying with the minimum requirements of applicable laws, regulations, and standards of practice or exceeding them. Environmental contributors include inputs from the Industry, the economy, and the general public.

Customers: This section lists any relevant customers of an organization. Knowledge about customers, customer groups, market segments, and potential customers allows organizations to tailor processes, develop a more customer-focused workforce culture, and ensure organizational sustainability. This section also addresses how the organization seeks to engage its customers, with a focus on meeting customers’ needs, building relationships, and demonstrating the value of processes and services. Understanding the customer’s voice provides meaningful information not only about a customer’s view but also about a customer’s marketplace behaviors and how these views and behaviors contribute to the organization’s sustainability in the marketplace. Customer types may be listed by product type, user category, geography, type of buyer (individual, corporate, small business), distributor, and/or end-use customer.

Understanding an organization’s profile, its strengths, vulnerabilities, and opportunities for improvement is essential to the success and sustainability of an organization and its processes. With this knowledge, organizations can identify their unique processes, competencies, and performance attributes, including those that set them apart from other organizations, those that help to sustain competitive advantage, and those that they must develop in order to sustain or build their market position.

Leadership

Leadership is defined as the art of motivating a group of people to act toward achieving a common goal. Leaders serve as the inspiration and directors of the actions within an organization and help pave the way for Process Improvement efforts. Senior leadership’s central role in Process Improvement is to set values and directions, communicate goals and objectives, identify resources, and provide time and materials to execute improvement activities.

Responsibilities of senior leadership include

• Setting directions and creating a customer focus

• Setting clear and visible values for the organization

• Creating strategies and systems for achieving performance excellence

• Stimulating innovation and building knowledge and capabilities

• Ensuring organizational sustainability

• Inspiring the workforce to contribute and embrace change

• Ensuring appropriate governance bodies are in existence

Senior leaders should serve as role models through their ethical behavior and their personal involvement in planning, communicating, coaching the workforce, developing future leaders, reviewing organizational performance, and recognizing members of the workforce. As role models, they can reinforce ethics, values, and expectations while building leadership, commitment, and initiative throughout an organization. In highly respected organizations, senior leaders are committed to developing the organization’s future and to recognizing and rewarding contributions by members of the workforce.

Strategic Planning

In most organizations today, some sort of structured planning is necessary to advance the organization’s objectives. Strategic Planning is an organization’s process of defining its strategy or direction and making decisions on allocation of its resources to pursue this strategy, including its capital and people. In essence, strategic planning is the formal consideration of an organization’s future course and gathers senior leaders, managers, and any necessary process owners within the organizations in order to

• Determine key strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT)

Strengths: Characteristics of the organization that give it an advantage in the market

Strengths: Characteristics of the organization that give it an advantage in the market Weaknesses: Characteristics of the organization that put it at a disadvantage in the market

Weaknesses: Characteristics of the organization that put it at a disadvantage in the market Opportunities: Items the organization could exploit to its advantage

Opportunities: Items the organization could exploit to its advantage Threats: Items in the businesses environment that could cause difficulty for the organization

Threats: Items in the businesses environment that could cause difficulty for the organization• Determine core competencies and the ability to execute strategy

• Optimize the use of resources to ensure the availability of a skilled workforce

• Bridge short- and long-term requirements that require capital expenditure, technology development, or new partnerships

• Ensure that deployment of any vision will be effective

• Achieve alignment on all organizational levels: (1) the organization and executive level, (2) the key work system and work process level, and (3) the work unit and individual job level

• Ensure that organizational plans and requirements are communicated

• Ensure Process Improvement efforts are progressing and are using industry best practice

Process Improvement emphasizes the following three key aspects of strategic planning, which are critical to ensuring effective outcomes:

• Customer Focus: Focusing on the drivers of customer engagement, the customer experience, new markets, market share, key factors in competitiveness, profitability, and organizational sustainability.

• Operational Performance Improvement Focus: Focusing on short- and longer-term productivity growth and cost/price competitiveness. This focus helps to build operational capability, including speed, responsiveness, and flexibility and represents an investment in strengthening organizational fitness.

• Organizational and Personal Learning Focus: Focusing on the necessary strategic considerations in today’s environment and the training and learning needs of the workforce, thereby ensuring that improvement and learning reinforce organizational priorities.

The primary role of strategic planning is to guide an organization’s actions and decisions over a specific period of time. A strategic plan that is continually reviewed helps an organization’s employees stay on track with tasks that are critical to long-term objectives. Many organizations are able to achieve this kind of routine, but many suffer from negative conditions that can prevent success. Common pitfalls organizations should steer clear of when conducting Strategic Planning efforts are

• Establishing too many priorities

• Not providing sufficient detail

• Not continually reviewing, planning, and prioritizing

Hoshin Kanri

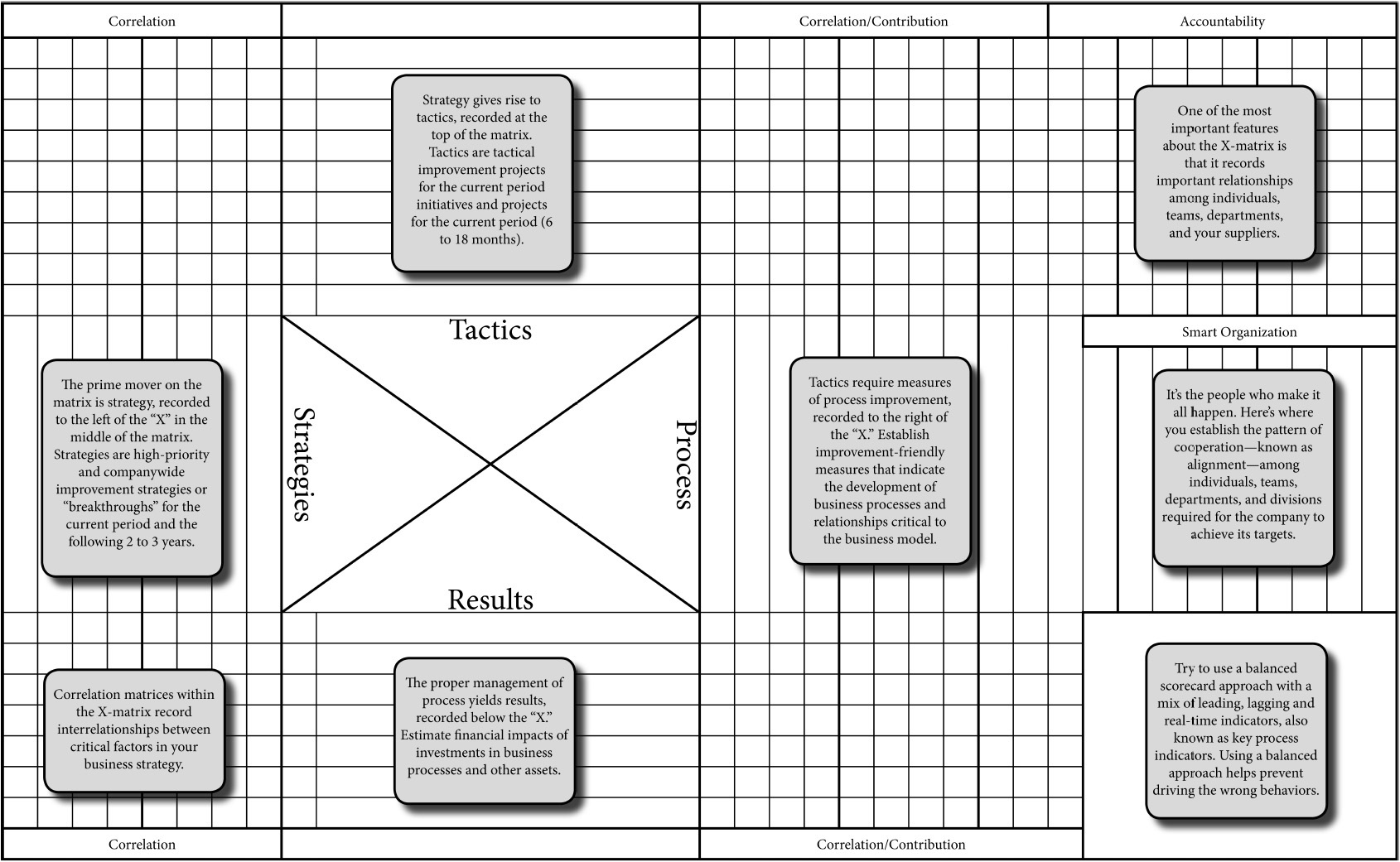

Among the most widely used tools for strategic planning is a model known as Hoshin Kanri, also termed Policy Deployment or Hoshin Planning. Hoshin Kanri was devised to capture and cement strategic goals about an organization’s future and what it means to bring these to fruition. Popularized in Japan in the late 1950s, Hoshin means compass or pointing the direction and Kanri means management or control. The name suggests how planning aligns an organization with accomplishing its goals. It is a system in which all employees participate, from the top down and from the bottom up, so that everyone in an organization is aware of their own and management’s Critical Success Factors (CSFs) and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). Proposed changes are usually identified to either improve the competitive performance of a process or to increase the competitive attractiveness of an organization’s products or services to its targeted market. Strategic objectives in both dimensions are essential in order to have a globally competitive organization. Hoshin Planning is intended to help organizations

• Identify specific opportunities for improvement

• Identify critical business assumptions and areas of vulnerability

• Set or quickly revise strategic vision

• Involve all leaders in planning to set business objectives in order to address the most imperative issues

• Set performance improvement goals for the organization

• Develop change management strategies for addressing business objectives

• Communicate the vision and objectives to all employees

• Hold participants accountable for achieving their part of the vision

• Align and leverage key departments

• Align and leverage suppliers

• Gain and keep customers

• Gain and keep investors

A critical challenge for organizations is often aligning objectives with employee work systems so that they are unified in their pursuit of strategy attainment. Alignment must include linking cultural practices, strategies, tactics, organizational systems, structure, pay and incentive systems, job design, and measurement systems in order to ensure that all elements are working together. At the beginning of the Hoshin cycle, executive leadership sets the organization’s overall vision and the annual strategic objectives and targets. At each level moving downward within the organization, managers and employees contribute to that vision and participate in the definition from the overall vision and their annual targets, to the strategy and detailed action plan they will use to attain these targets. They also define the measures that will be used to demonstrate that they have successfully achieved their targets.

Another key principle of Hoshin Planning is to deploy and track only a few priorities at each level of the organization. Given all of the rapid changes and increasing distractions organizations face, individuals must be able to focus on those things that offer the greatest advantage to the organization. The clearer the priorities, the easier it is for people to focus on what truly delivers the most value at any given time.

There are seven steps for effective Hoshin planning:

1. Identify your critical objectives (five-year vision and one-year action plan).

2. Ensure each objective is Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic, and Time Sensitive (SMART).

3. Evaluate any constraints.

4. Establish performance measures.

5. Develop an implementation plan.

6. Assign ownership of goals.

7. Conduct regular reviews.

NOTE SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic, and Time Sensitive) is a mnemonic used to guide organizational leaders toward setting specific objectives over and against more general goals. Ultimately, it serves to ensure that all goals are clear, unambiguous, and without vagaries or platitudes. For a goal to be specific it must tell an organization’s workforce exactly what is expected, including why it is necessary, who will be involved, where it will happen, and which elements are most pertinent.

A key technique when using the Hoshin Method is called Catchball. Catchball is a tool used to manage group dialogue and gather ideas. In Catchball, managers and front-line workers develop the strategies, tasks, and metrics to support the accomplishment of the overall Hoshin. This is where the organization and its management team consider what actions are required to achieve each goal. The output of the Catchball process is a detailed action plan for implementation.

Other Hoshin Planning Techniques used to gather ideas and help set targets include:

• Stop listing: This is the act of creating a list of things the organization should no longer do. These may be projects that are not realizing value and should be cancelled, markets to get out of, or products that should be discontinued.

• Voice of customer analysis: The voice of the customer (VOC) is an extremely valuable part of an organization’s planning process. It allows organizations to find valuable insights into what their customers want or need and use those findings as a marketing advantage.

• Bowling charts: These are visual depictions of measures and progress toward organizational goals. They are usually monthly measures that outline goals versus actual metrics with stoplight color-coding. In many cases, goals that have not been completed in previous iterations are carried over into the new planning cycles if they are still deemed necessary.

• Five-year outlook: The five-year outlook plan is used to help leaders think beyond the organization’s current fiscal year. It serves to remind individuals of the longer-term strategic direction the organization wishes to take and which Process Improvement efforts need to be launched in order to achieve these targets.

The Hoshin Planning approach also aims to ensure that insight and vision are not forgotten as soon as planning activities are completed. Plans, once confirmed, are kept alive, acted on daily, and are not abandoned as soon as they have been completed. Regular and iterative reviews take place to identify any progress, discuss any issues, and initiate any needed corrective action. Hoshin Planning implements daily, weekly, monthly, and yearly points of review. Accountability lies with each employee to ensure their goals and targets remain aligned and up to date with the level above them. Sound Hoshin Planning involves continuous communication. Organizations often incorporate feedback systems that allow bottom-up, top-down, horizontal, and multidirectional communication of suggestions, issues, concerns, and impediments.

In closing, Hoshin Planning provides an opportunity to continually improve performance by disseminating and deploying the vision, direction, and plans of corporate management to all employees so that all job levels can continually act, evaluate, study, and provide feedback on the organization’s future and its processes. Figure 6-3 is an example of a Hoshin Kanri.

Process Management

An organization with a logical structure will be ineffective if it is not managed appropriately. Process Management is the ensemble of planning, engineering, improving, and monitoring an organization’s processes in order to sustain organizational performance. It is a systematic approach to making an organization’s workflow more effective, more efficient, and more capable of adapting to an ever-changing environment. A business process can be seen as a value chain or a set of activities that will be used to accomplish a specific organizational goal in order to meet customer requirements. Consequently, the goal of process management is to reduce human error and miscommunication in these processes and to focus stakeholders on improving their operating environment using Process Improvement methods. Process Management and Improvement efforts may be initiated from a business or operational unit or the IT organization. These efforts can focus on innovation, transformation, organizational development, change management, enterprise architecture, performance, compliance, and so on.

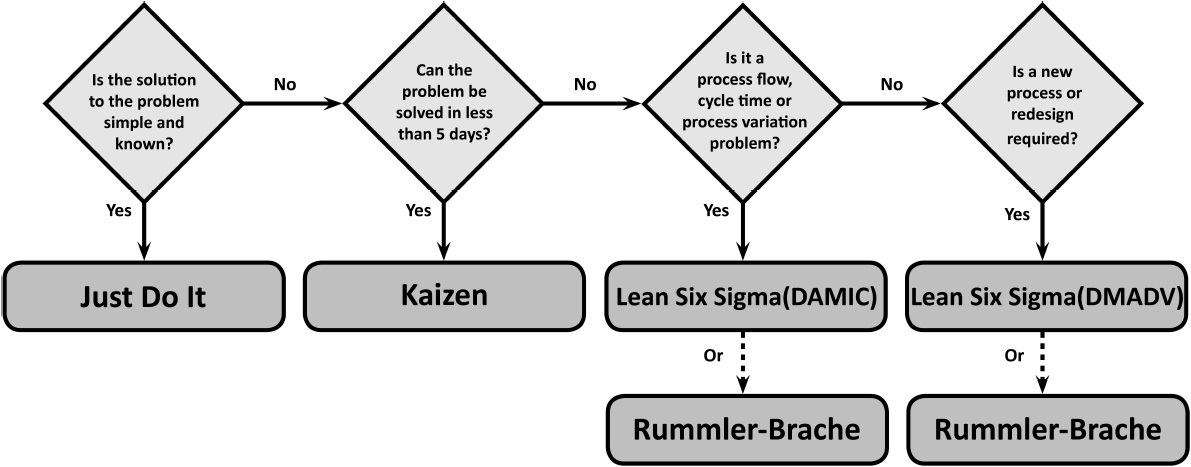

There are several kinds of Process Improvement methodologies being practiced in the market today. Some of the more common methods or management paradigms include Just Do It, Kaizen, Lean Six Sigma, and Rummler–Brache, and are discussed below.

Just Do It

Just Do It is the most basic concept of Process Improvement. This model is used primarily when a problem with a process has been identified, the solution is known and understood, and very little effort is required to implement the change. Often, process issues that fall into this category can be completed within hours or by holding a meeting with key stakeholders to resolve a particular issue. Although Just Do It is a convenient and straightforward method for improving a process, ongoing process monitoring is still required.

Kaizen

Kaizen is a methodology that was established shortly after World War II by the infusion of US quality principles and Japanese philosophies and concepts. Kai, meaning to take a part and make new, and Zen, to think about in order to help others, make up the philosophy and approach that is the basis for all Process Improvement initiatives.

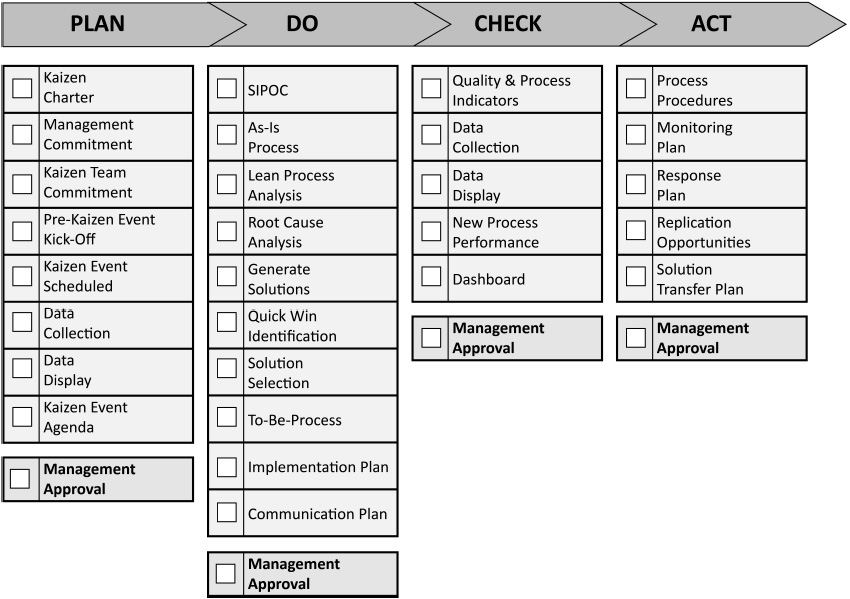

Kaizen Events are intensely concentrated, team-oriented efforts that are initiated to rapidly improve the performance of a process. A Kaizen Event involves holding small workshops attended by the owners and operators of a process in order to make improvements to the process, which are within the scope of the process participants. Effort is coordinated over a short period of time, usually less than five days, and involves deliverables and activities that must be completed prior to and immediately following the event in order to ensure successful execution. Any solution or task that requires action during or after the Kaizen Event should be easy to implement and not cause significant disruption to the organization. This will demonstrate immediate success and help generate momentum for ongoing improvement efforts.

Purpose of Kaizen Events

The purpose of a Kaizen event is to gather operators, managers, and owners of a process in one place in order to

• Map the existing process

• Use qualitative analysis techniques to determine problems

• Rapidly improve the existing process

• Solicit buy-in from all parties related to the process

• Implement solutions and hold further events for Continuous Improvement

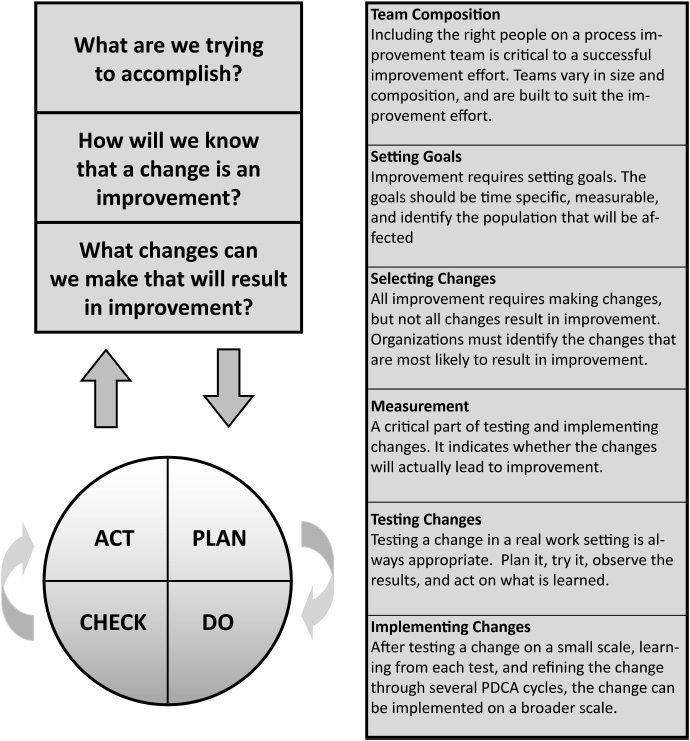

Plan-Do-Check-Act

Among the most widely used tools for Kaizen events is a model known as the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle, also known as the Plan-Do-Study-Act or Deming Improvement Model. The PDCA cycle is a simple, yet powerful, tool for accelerating improvement. The ability to develop, test, and implement change is essential for any individual, group, or organization that wants to continuously improve. The PDCA model is not meant to replace change models that organizations may already be using. Rather, PDCA models accelerate improvement. This model has been used successfully by organizations to improve many different processes and outcomes.

The PDCA model has the following two parts (Figure 6-4):

• Three fundamental questions, which can be addressed in any order:

What are we trying to accomplish?

What are we trying to accomplish? What changes can we make that will result in improvement?

What changes can we make that will result in improvement? How will we know that a change is an improvement?

How will we know that a change is an improvement?• The PDCA four-step cycle to test and implement changes. This cycle guides improvements through testing in order to determine if the change is appropriate through to implementation.

The PDCA cycle involves the following four steps:

1. Plan: Plan the Kaizen event.

• Determine the objective and gather information regarding resources, management, and customer complaints about the process in question

• Gather any current performance data that are available

• Make predictions about what will happen and why

• Estimated time frame to complete: 1–3 weeks

2. Do: Facilitate the Kaizen Event.

• Document and analyze the current process

• Document problems and unexpected observations

• Determine what modifications should be made

• Implement improvements to meet management and customer objectives

• Estimated time frame to complete: 2–5 days

3. Check: Set aside time to analyze the data and study the results.

• Complete analysis of the data related to improvements and overall process performance

• Compare the data to predictions

• Summarize and reflect on what was learned

• Present results to management and the organization

• Estimated time frame to complete: 1–2 weeks

4. Act: Document and standardize new processes and create a monitoring plan to ensure improvements are sustained

• Prepare a plan for another Kaizen Event if necessary

• Implement improvements on a wider scale, if appropriate

• Estimated time frame to complete: 1–2 weeks

NOTE Although Kaizen is specifically outlined as a technique or method for Process Improvement in this chapter, improvement is not the sole purpose of a Kaizen event. Ultimately, Kaizen is meant to teach people how to solve problems (process or otherwise) and engage members of the workforce in doing so. Self-organization around problem solving and infusing a culture where staff members regularly confront and solve problems as a primary part of their job is at the root of the Kaizen approach.

Roles and Responsibilities for Kaizen Events

This section lists the roles and responsibilities involved in a Kaizen Event.

Process Improvement Manager: The Process Improvement Manager is the primary contact for all improvement efforts surrounding a process that has been selected for improvement using the Kaizen method. The Process Improvement Manager leads all Kaizen activities, facilitates the Kaizen Event, and is accountable for reporting progress and coordinating communication to stakeholders. Other responsibilities include

• Training team members in Kaizen principles and techniques

• Working with management to define the process area, resources, and problem and goal statement for the Kaizen improvement effort

• Scheduling all meetings for completing Kaizen deliverables

• Clearly defining desired outcomes of Kaizen activities with leadership and project team members

• Managing the implementation of solutions and ensuring the transition of the improved process to the business

• Maintaining all documentation from the event and preparing and submitting all deliverables

Kaizen Team Members: Kaizen Team Members are the primary resources assigned to the initiative and are responsible for completing the tasks listed in the action plan, both during and immediately following the Kaizen Event. They are usually operators from the various departments within a process and are considered spokespersons for the Kaizen methodology. They participate in all Kaizen activities as representatives of their operational units. As a rule of thumb, most Kaizen teams do not exceed six members. Other responsibilities include

• Providing process expertise and feedback during all Kaizen activities

• Delivering regular updates to the team and management on the status of deliverables

• Helping to manage the implementation of solutions and ensure the transition of the improved process to the business owner and various operational teams

• Acting as a change catalyst

Subject Matter Experts: A Subject Matter Expert (SME), often called domain expert, is an expert in a particular process, area, or topic. They have significant knowledge or skills in a particular area or endeavor relevant to the process in question. They participate in Kaizen Events as needed and are also considered spokespersons for the Kaizen methodology. Other responsibilities include

• Providing process expertise and feedback during all Kaizen activities

• Helping to manage the implementation of solutions and ensure the transition of the improved process to the business owner and various operational teams

• Acting as a change catalyst

Management Team: The Management Team is comprised of department managers, executives, and the owner of the process being improved. This team works with the Process Improvement Manager (Kaizen Lead) to identify the areas that require improvement and to determine the objectives of the Kaizen activities. Their primary function is to direct the team toward a goal and approve any deliverables. Other responsibilities include

• Driving Kaizen and the Continuous Improvement culture

• Attending all Kaizen Events as needed and providing approval/feedback to the team

• Identifying resources and providing time and materials to execute activities

• Publicly endorsing Kaizen improvement activities

• Removing barriers to any Kaizen activities

Guidelines for Kaizen Events

Kaizen events should

• Focus on quality or efficiency problems

• Focus on processes with no more than two outputs

• Focus on processes with no more than two customers

• Require no external resources (e.g., outside customers)

• Fall within the immediate span of control of the Kaizen team

• Be narrowly scoped to include no more than seven to eight stakeholders

Key Kaizen Deliverables

Figure 6-5 outlines several common deliverables for the Kaizen process:

FIGURE 6-5 Key Kaizen Deliverables

Lean Six Sigma

Lean Six Sigma, which was started in the early to mid 1980s, is a problem-solving and continuous process improvement method that is used to reduce variation in manufacturing, service, or other business processes. Sigma is a Greek letter as well as a statistical unit of measurement used to define the standard deviation of a population. In industry terms, Sigma is a name given to indicate how much of a process’s output falls within customers’ requirements. The sigma scale ranges from 1 to 6, where the higher the sigma value, the fewer defects that are occurring, the faster the cycle time, and the more effective process outputs are at meeting customer requirements.

Lean Six Sigma projects measure the cost benefit of improving processes that are producing substandard service to customers and primarily focuses on reducing variation. The goal of each successful Lean Six Sigma project is to produce statistically significant improvements in a process. Over time, multiple Lean Six Sigma projects produce virtually defect-free performance and produce substantial financial benefit to an operating business or company.

Lean Six Sigma also focuses on eliminating the seven kinds of wastes, or Muda (pronounced “moo-duh”; a Japanese term that means uselessness, idleness, or wastefulness). A commonly use mnemonic for identifying various wastes within a process is TIMWOOD. The seven waste categories are

• Transportation

• Inventory

• Motion

• Waiting

• Overproduction

• Overprocessing

• Defects

Lean Six Sigma is an amalgamation of Lean’s waste elimination characteristics and Six Sigma’s focus on the critical to quality characteristics of a process. Formal training does exist for Lean Six Sigma and is provided through the belt-based training system that endorses various levels of expertise and experience from novice to practitioner: White, Yellow, Green, Black, and Master Black. An excellent organization that certifies individuals in Six Sigma practices is the Acuity Institute (www.acuityinstitute.com).

Purpose of Lean Six Sigma

The purpose of a Lean Six Sigma project is to gather operators, managers, and owners of a process in order to

• Ensure that the voice of the customer (Customer Requirement) is understood

• Identify root causes of a problem and initiate improvements

• Identify non–value-added activities in processes

• Standardize existing business processes

• Identify any new process needs

• Coordinate metrics among teams, suppliers, and customers

• Improve customer satisfaction

• Ensure corporate, industry, and government compliance

Define-Measure-Analyze-Improve-Control and Define-Measure-Analyze-Design-Verify

Lean Six Sigma projects follow two models inspired by Deming’s Plan-Do-Check-Act Cycle. These models are composed of five phases and bear the acronyms DMAIC (Define-Measure-Analyze-Improve-Control; pronounced “duh-may-ick”) and DMADV (Define-Measure-Analyze-Design-Verify; pronounced “duh-mad-vee”).

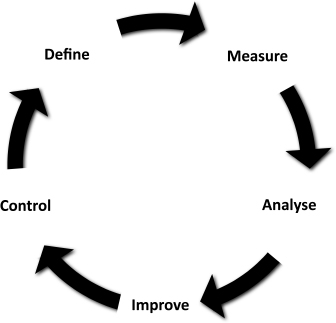

The DMAIC model is used primarily to improve existing processes that are not meeting customer requirements or business objectives. Because these processes often contain several non–value-added activities, a DMAIC project is initiated to identify the root causes of the problem and remove waste from the process. DMAIC consists of the following five phases (Figure 6-6):

FIGURE 6-6 The DMAIC Cycle

• Define: Identify customer requirements (voice of the customer) as well as the project goals

• Measure: Identify and measure performance of the current process and collect any necessary data

• Analyze: Analyze the data to investigate and verify cause-and-effect relationships, determine what the relationships are, and seek out the root cause of the defect under investigation

• Improve: Optimize the current process based upon data analysis and design a new, future state process; execute pilot runs to assess process capability

• Control: Monitor the newly deployed process to ensure that any deviations from the target are corrected before they result in service issues, implement control systems such as statistical dashboards, and continuously monitor the process

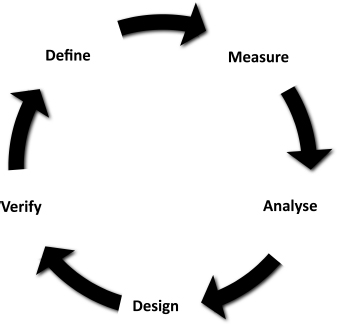

The DMADV model, also known as DFLSS (Design-For-Lean-Six-Sigma), is used primarily to create new processes or improve processes that have been significantly degraded and require enormous effort to improve. A DMADV project is initiated when a new process is needed or when an existing process requires significant architectural changes. DMADV consists of the following five phases (Figure 6-7):

FIGURE 6-7 The DMADV Cycle

• Define: Design goals that align with customer demands and the enterprise strategy

• Measure: Measure and identify CTQ (characteristics that are Critical to Quality), process capability, and risks

• Analyze: Develop alternatives in order to create high-level designs and evaluate design capabilities to select the best design

• Design: Optimize the design and plan for its verification; this may require the use of simulations

• Verify: Verify the design, set up any necessary pilots, implement the process in production, and transition it to the process owner(s)

Roles and Responsibilities for Lean Six Sigma Projects

Six Sigma roles are structured to support project success and drive business performance results. It is critical to gain agreement regarding roles and time commitment early in the process so that teams can establish chemistry and focus on project deliverables.

Executive Leadership: Executive Leadership provides and aligns resources for any improvement initiative, specifically at the sponsor level. The executive leadership team defines the business strategy and establishes improvement priorities and targets and is often organized within a formal steering committee. Other responsibilities include

• Monitoring internal and external factors that are affecting the business

• Communicating the plan for overall business success

• Championing the Lean Six Sigma vision

• Establishing accountability for results

• Setting the tone, serving as role models who display appropriate behaviors, and acting as change leaders

• Integrating Lean Six Sigma into business direction and plan

• Marketing Lean Six Sigma programs and results

Process Owner: The Process Owner’s role exists to provide expertise on a process and to provide resources to serve as team members and SMEs on projects. They are the primary proprietor of any items related to the process in question and assist with determining Lean Six Sigma projects and goals. Other responsibilities include

• Approving and supporting Six Sigma projects

• Approving changes in project scope and removing barriers

• Owning the solution being delivered by the project team

• Supporting the implementation of improvement actions

Project Sponsor: The Project Sponsor’s role exists to provide and align resources, ensure that project deliverables are being maintained, and ensure that the project is delivered on time and on budget. They also ensure that the project is aligned with department and strategic objectives and establish improvement priorities, targets, and accountability results. Other responsibilities include

• Ensuring cross-functional collaboration

• Role modeling appropriate behaviors

• Acting as a change leader

• Approving all phases of a Lean Six Sigma project

• Approving changes in project scope and removing barriers

• Marketing Lean Six Sigma programs and results

NOTE In many cases, the Process Owner and Project Sponsor are the same person supporting a Six Sigma Project.

Process Architect: The Process Architect provides expertise on Lean Six Sigma tools and techniques as well as process architecture and change management principles. They are responsible for ensuring that any changes made within a particular process conform to Process-Oriented Architecture (POA) principles and do not disrupt the Process Ecosystem in a negative manner. This position can vary from full-time to part-time assignment depending on an initiative’s complexity. These individuals train and coach process improvement managers and project team members and guide them on how to properly design processes that meet the enterprise’s strategic objectives. They are considered advisors to project champions, sponsors, and process owners. Other responsibilities include

• Providing strategic direction to leadership and project teams

• Identifying projects that are critical to achieving business goals and sustaining an organization’s process ecosystem

• Serving as the main champion during change implementation

• Ensuring cross-functional and cross-team collaboration

• Ensuring that all appropriate process architecture principles and standards are followed

Process Improvement Manager: The Process Improvement Manager provides direction and leadership for project teams, directs interproject communications, and manages the day-to-day activities of a Lean Six Sigma Process Improvement project. This is a full-time position that is accountable for reporting project progress and coordinating communication to stakeholders. These individuals directly manage the implementation of solutions and ensure the transition of improved processes to the business. Other responsibilities include

• Maintaining all documentation for a project and preparing and submitting deliverables

• Delivering results through the application of the Lean Six Sigma methodology

• Providing skills training when needed

• Acting as a change catalyst

Project Team Members: Team members are the primary resources assigned to the initiative and are responsible for tasks within the project’s action plan. They are considered spokespersons for the Lean Six Sigma methodology and participate in project activities as needed. Other responsibilities include

• Providing process expertise and feedback during all Process Improvement activities

• Delivering regular updates to the team and management on the status of action tasks

• Helping to manage the implementation of solutions and ensuring the transition of the improved process to business owners and operational teams

• Acting as a change catalyst

Subject Matter Experts: As with Kaizen Events, SMEs are assigned to Lean Six Sigma Process Improvement projects and are considered domain experts or persons with significant knowledge or skills in a particular area of endeavor relevant to the process in question. They participate as needed in Lean Six Sigma projects and are crucial for understanding the true dynamics within the operational units involved with a process. Other responsibilities include

• Providing process expertise and feedback during any necessary project activities

• Helping to manage the implementation of solutions and ensuring the transition of the improved process to business owners and operational teams

• Acting as a change catalyst

Financial Analyst: The Financial Analyst is responsible for providing financial support to Lean Six Sigma projects. They are involved on an as-needed basis and have the primary function of providing financial savings forecasts for deliverables and changes within a process or the project as a whole. Other responsibilities include

• Providing standard and consistent guidelines for project valuation

• Estimating project savings during project execution

• Tracking and validating actual project savings after project closure

Guidelines for Lean Six Sigma Projects

Lean Six Sigma projects should

• Focus on business value

• Be linked to the enterprise strategy and support specific business-centric objectives

• Be viable, visible, and verifiable

• Contain Goals and a vision for the improvement effort that is endorsed by leadership

• Conduct frequent and iterative reviews of goals and timelines

• Ensure that proper resource planning (top-down or bottom-up) occurs

• Hold leads and participants accountable for their deliverables

• Utilize proper governance and decision criteria for decision-making

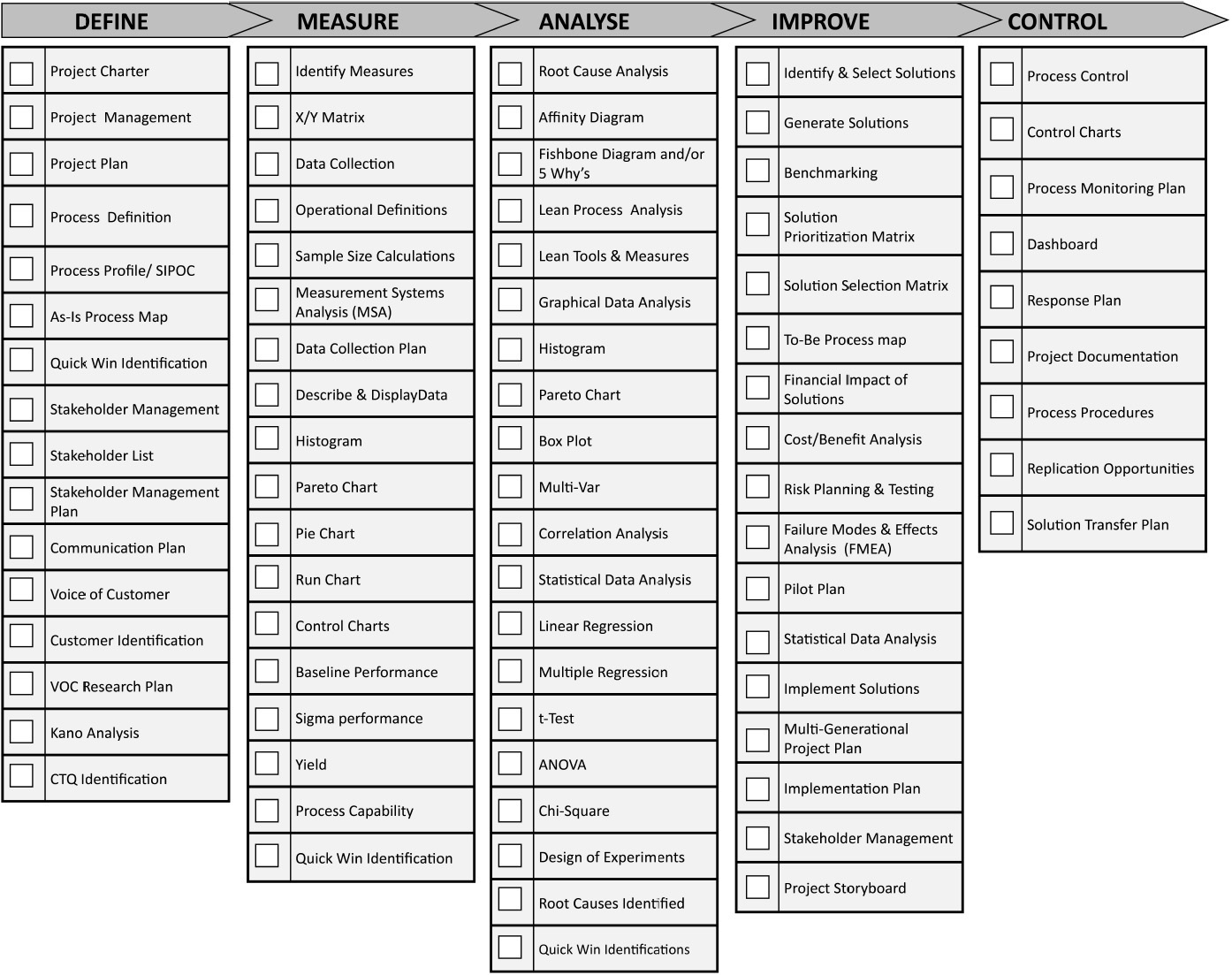

Key Lean Six Sigma Deliverables

Figure 6-8 outlines several common deliverables for Lean Six Sigma Projects:

FIGURE 6-8 Key Lean Six Sigma Deliverables

Rummler–Brache

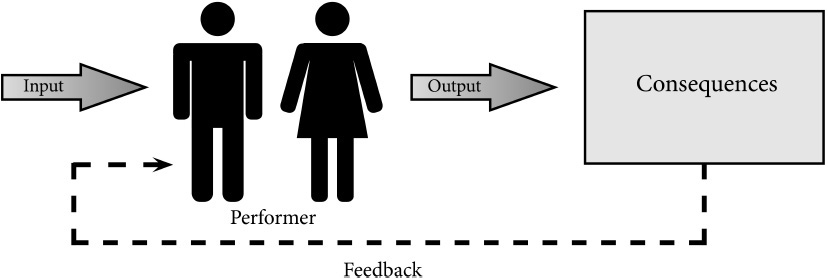

Geary Rummler and Alan Brache defined a comprehensive approach to organizing companies around processes, managing and measuring performance, and redefining processes in their book, Improving Performance: How to Manage the White Space on the Organization Chart. The Rummler–Brache Methodology is a systematic approach to business process change. It is a step-by-step set of instructions on how to make changes to the way in which work is completed across an organization. The primary differentiator of the Rummler–Brache model is the premise that all organizations behave as adaptive systems with three levels of focus (the organization, its processes, and its workforce), whereby any change being proposed in an improvement effort must take into account all three variables during process analysis and design.

Purpose of Rummler–Brache

The purpose of a Rummler–Brache Project is to gather operators, managers, and owners of a process in order to

• Address performance in a comprehensive (rather than piecemeal) fashion

• Identify disconnects within a process (people, process, technology) and their root causes in order to initiate improvements

• Ensure the supplier, customer, employee, and shareholder experience is understood

• Identify new process needs

• Improve customer satisfaction and ensure that measurable results exist for customers and stakeholders

• Identify and improve how the workforce interacts and contributes to processes and ensure that the human component is at the forefront of any proposed change (user-centric design)

The Rummler–Brache methodology is based on the following two core concepts:

• Three Levels of Performance: These levels are the organization, process, and performer, or people, levels. To effect change in an organization, it is necessary to understand the potential impacts to all three levels. For example, a process change could mean significant changes to job responsibilities and skills required to execute those responsibilities. Failure to adequately account for these interrelationships is a leading cause of failed process improvement implementations.

• Three Performance Dimensions: These dimensions are goals, design, and management. Having clear goals at each level ensures alignment with desired results; having robust design at each level maximizes the efficiency of operations; and having good management systems at each level ensures that the organization can survive and adapt to changes in the business environment. A failure in any of these dimensions will lead to performance problems.

Rummler–Brache Model

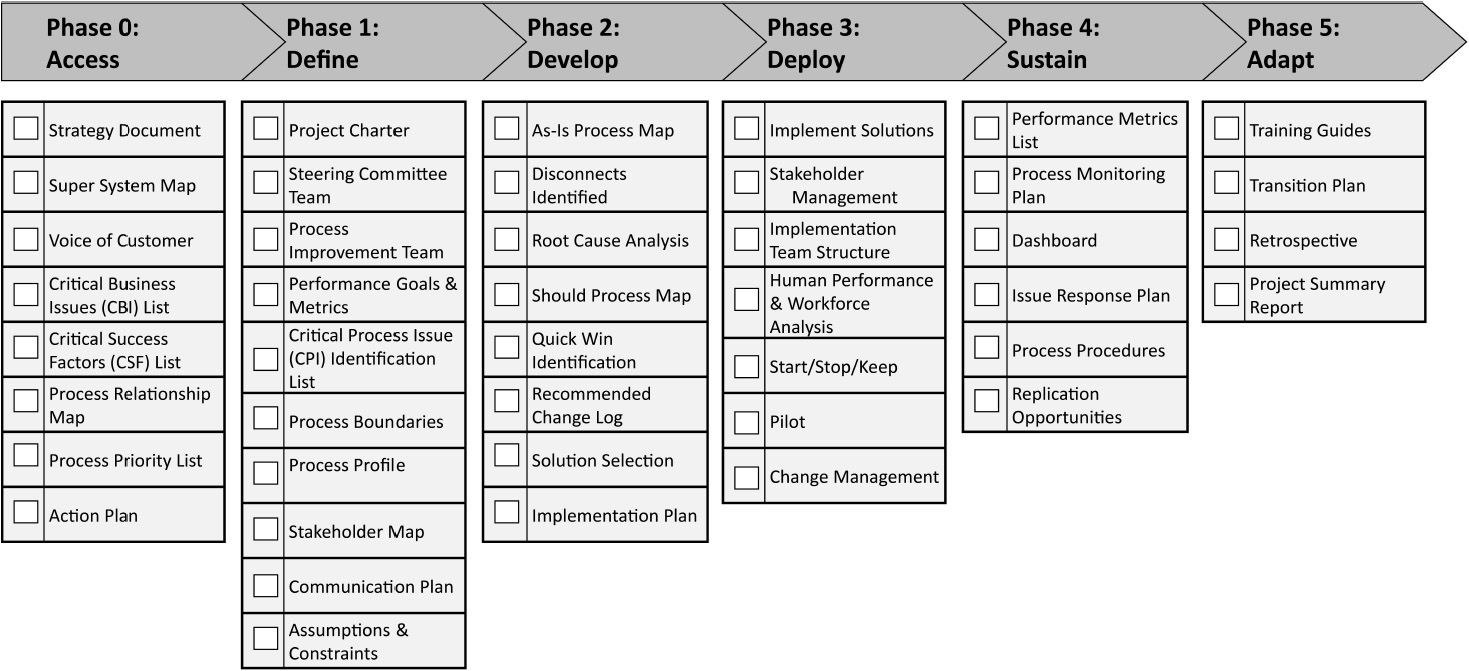

Rummler–Brache projects follow a model inspired by Deming’s Plan-Do-Check-Act Cycle. This model is composed of the following five phases and bears the acronym ADDDSA (Assess-Define-Develop-Deploy-Sustain-Adapt; pronounced “Ad-sah”):

• Phase 0, Assess: The Assess phase seeks to understand the customer’s voice and the customer’s true requirements for the organization. It also examines the organization’s processes to determine which processes require intervention and which processes simply need to be maintained based on these requirements.

• Phase 1, Define: The Define phase determines the boundaries of the process or system of processes that will be worked on. It sets performance targets and lays out a road map for achieving these targets. This information, plus information about stakeholders and change management strategies, is captured in the Define phase.

• Phase 2, Develop: The Develop phase designs and tests modifications to processes. These modifications can range from basic streamlining to a green field approach where new processes are created. The two main requirements are the analysis and mapping of the existing process (as-is) and the design of the future-state process (should). Disconnects in the current-state or as-is process are clearly listed, prioritized, and defined prior to future-state solution design.

• Phase 3, Deploy: The Deploy phase manages the adoption, stabilization, and institutionalization of a new process and/or any changes needed to rectify disconnects found in the Develop phase. This can be done in iterations to maximize adaptability and minimize risk. Key activities of the Deploy phase include executing the implementation plan as well as focusing on communication and change management. Special attention is put on Human performance and the effects of change on the organization’s workforce.

• Phase 4, Sustain: The Sustain phase confirms that what has been implemented is achieving the expected results and continues to improve any remaining disconnects. The activity in this phase primarily involves process monitoring.

• Phase 5, Adapt: The Adapt phase transitions the process to the necessary business owner or operations team and trains owners and operators on how to monitor the process on an ongoing basis. It ensures that metrics are created and in place and that they align with the organization’s strategic goals.

Roles and Responsibilities for Rummler–Brache Projects

The Rummler–Brache life cycle is similar to that of most Process Improvement methods and, as such, its project makeup is comprised of the following key roles:

Executive Leadership: Executive Leadership provides and aligns resources for any improvement initiative, specifically at the sponsor level. The executive leadership team defines the business strategy and establishes performance goals and improvement priorities.

Project Sponsor: The Project Sponsor’s role exists to ensure project deliverables are being maintained and that the project is delivered on time and on budget. They also ensure that the project is aligned with department and strategic objectives as well as any improvement priorities. The project sponsor is ultimately accountable for a project’s results.

Process Owner: The Process Owner’s role exists to provide expertise on a process and to provide resources to serve as team members and SMEs on projects. They are the primary proprietor of any items related to the process in question and assist with determining Rummler–Brache projects and determining the goals for them.

Process Architect: The Process Architect provides expertise on the Rummler–Brache method as well as process architecture and change management principles. They are responsible for ensuring any changes made within a particular process conform to POA principles and do not disrupt the organization’s Process Ecosystem in a negative manner. These individuals train and coach process improvement managers and project team members and are considered advisors to project champions, sponsors, and process owners.

Process Improvement Manager: The Process Improvement Manager leads the process owner and executive team in defining the scope of the process improvement and its goals, boundaries, staffing, and timetable. The role demands a high degree of planning and organizing skills and the ability to advise and coach senior members.

Project Team Members: Project Team Members are the primary resources assigned to the initiative and are responsible for tasks within the project schedule. They are considered spokespersons for the Rummler–Brache methodology and participate in project activities as needed.

Guidelines for Rummler–Brache Projects

Rummler–Brache projects should

• Focus on improving overall performance

• Ensure that all disconnects within a process, including people and technology gaps, are identified and considered

• Be linked to the enterprise’s strategic objectives

• Be endorsed by leadership

• Conduct frequent and iterative reviews of goals and timelines

• Ensure that proper resource planning (top-down or bottom-up) occurs

• Hold participants accountable for their deliverables

• Utilize proper governance and decision criteria for decision-making

Key Rummler–Brache Deliverables

Figure 6-9 outlines several common deliverables for Rummler–Brache projects:

FIGURE 6-9 Key Rummler–Brache Deliverables

Selecting a Process Improvement Methodology

Professionals have often debated or questioned when to initiate a full-scale Six Sigma or Rummler–Brache project and when to initiate smaller-scale improvement efforts such as Kaizen Events. Although the models are similar, there are distinct reasons for initiating one methodology over the other. Kaizen is usually used for small-scale or urgent Process Improvement initiatives where the root cause of a problem is widely understood, but the solution is unknown. A two- to five-day Kaizen workshop is initiated to analyze this process and to plan and implement improvements to it. Lean Six Sigma is used to create new processes or to analyze existing processes where the problem is not yet understood. Lean Six Sigma determines the root cause of a problem and uses statistical analysis to determine the most optimal way to improve the issue. Rummler–Brache is also used to create new processes or to analyze existing processes where problems are not yet understood. Where Lean Six Sigma places heavy emphasis on statistical analysis and measurements, Rummler–Brache focuses more on workforce or human performance indicators. Ultimately, the methodology that is chosen depends on the complexity of the business problem, what the organization’s focus is (workforce or metric), and what method best suits the stakeholders being serviced. In many cases, practitioners often combine several techniques from multiple methods in their performance planning and improvement efforts. Figure 6-10 identifies the key decisions involved when selecting a methodology for improvement.

FIGURE 6-10 Selecting a Process Improvement Methodology

Other Process Improvement Methodologies

Most Process Improvement methods contain several valuable philosophies and approaches that can be used in any Process Improvement project. In many cases, certain philosophies can be combined with other methods to achieve greater process excellence. Beyond the more common methods outlined in detail in this chapter, there are several other methodologies that exist in the industry today, including

• Total Quality Management. Total Quality Management (TQM) is a Process Improvement approach with a primary focus on customer satisfaction. Conceived from the various works of W. Edwards Deming, Kaoru Ishikawa, and Joseph M. Juran, TQM involves all members of an organization when improving its processes, products, services, and culture. It infuses the following basic principles into the culture and activities of an organization:

Customer focus: The customer determines the definition of quality for an organization.

Customer focus: The customer determines the definition of quality for an organization. Employee involvement: All employees participate in Process Improvement activities and work toward common goals.

Employee involvement: All employees participate in Process Improvement activities and work toward common goals. Process centered: The organizations focuses on process thinking.

Process centered: The organizations focuses on process thinking. Integrated system: An organization’s departments are viewed as interconnected.

Integrated system: An organization’s departments are viewed as interconnected. Strategic approach: The organization strategically plans its vision, mission, and goals.

Strategic approach: The organization strategically plans its vision, mission, and goals. Fact-based decision-making: Process performance data are viewed as necessary.

Fact-based decision-making: Process performance data are viewed as necessary. Communication: Effective communication is critical to maintaining morale and motivating employees.

Communication: Effective communication is critical to maintaining morale and motivating employees.• Theory of Constraints. Theory of Constraints is a Process Improvement approach that focuses on identifying the most significant bottleneck in a process and rectifying the issue. It includes the following five-step process:

1. Identify the constraint. The first step is to identify the weakest link in a process.

2. Exploit the constraint. The second step is to find a solution to the problem in order to increase process efficiency.

3. Subordinate everything else to the constraint. The third step is to align the whole organization to support the solution.

4. Elevate the constraint. The fourth step is to make any other changes needed to increase the constraint’s capacity.

5. Go back to step 1. The final step is to review how the process is performing with the fix that has been implemented. If the issue has been resolved, the process can be repeated.

• Streamlined Process Improvement (SPI). SPI, sometimes called process redesign, focused improvement, process innovation, or process streamlining, is a step-by-step method for improving business processes created by H. James Harrington. It is a systematic way of using cross-functional teams to analyze and improve the way a process operates by improving its effectiveness, efficiency, and adaptability. SPI’s primary focus is on upgrading major organizational processes using a five-step approach known as PASIC. Where traditional methods focus primarily on continuous process improvement, SPI believes in a combined organizational strategy to Process improvement that includes both traditional continuous improvement tactics and radical redesign efforts. When breakthrough improvement and continuous improvement are combined, the result is often significant improvement in process performance over continuous improvement alone. Other benefits of Streamlined Process Improvement include

Lowering organizational costs

Lowering organizational costs Moving decision-making closer to the customer

Moving decision-making closer to the customer Shortening return on investment cycle

Shortening return on investment cycle Increasing market share

Increasing market share Improving productivity

Improving productivity Minimizing the number of contacts that customers have

Minimizing the number of contacts that customers have Increasing profits

Increasing profits Improving employee morale

Improving employee morale Minimizing bureaucracy

Minimizing bureaucracy Reducing inventory

Reducing inventory Improving quality

Improving qualityThere are five phases of SPI, which are known as PASIC, and they consist of 31 activities.

Phase I: Planning for Improvement

Phase I: Planning for Improvement• Activity 1: Define Critical Business Processes

• Activity 2: Select Process Owners

• Activity 3: Define Preliminary Boundaries

• Activity 4: Form and Train the PIT

• Activity 5: Box in the Process

• Activity 6: Establish Measurements and Goals

• Activity 7: Develop Project and Change Management Plans

• Activity 8: Conduct Phase I Tollgate

Phase II: Analyzing the Process

Phase II: Analyzing the Process• Activity 1: Flowchart the Process

• Activity 2: Conduct a Benchmark Study

• Activity 3: Conduct a Process Walk-Through

• Activity 4: Perform a Process Cost, Cycle Time, and Output Analysis

• Activity 5: Prepare the Simulation Model

• Activity 6: Implement Quick Fixes

• Activity 7: Develop a Current Culture Model

• Activity 8: Conduct Phase II Tollgate

Phase III: Streamlining the Process. Refining the process

Phase III: Streamlining the Process. Refining the process• Activity 1: Apply Streamlining Approaches

• Activity 2: Conduct a Benchmarking Study

• Activity 3: Prepare an Improvement, Cost, and Risk Analysis

• Activity 4. Select a Preferred Process

• Activity 5: Prepare a Preliminary Implementation Plan

• Activity 6: Conduct Phase III Tollgate

Phase IV: Implementing the New Process. Installing the new process

Phase IV: Implementing the New Process. Installing the new process• Activity 1: Prepare a Final Implementation Plan

• Activity 2: Implement New Process

• Activity 3: Install In-Process Measurement Systems

• Activity 4: Install Feedback Data Systems

• Activity 5: Transfer Project

• Activity 6: Conduct the Phase IV Tollgate

Phase V: Continuous Improvement. Making small-step improvements

Phase V: Continuous Improvement. Making small-step improvements• Activity 1: Maintain the Gains

• Activity 2: Implement Area Activity Analysis

• Activity 3: Qualify the Process

• Toyota Production System. The Toyota Production System, often referred to as the Lean Manufacturing System or Just-in-Time System, is a Process Improvement approach that strives to eliminate overburden (Muri), inconsistency (Mura), and waste (Muda). It abides by several principles that, together, form the Toyota Way of Thinking. These principles are the basis for the company’s Process Improvement efforts. They are

Base your management decisions on a long-term philosophy, even at the expense of short-term financial goals.

Base your management decisions on a long-term philosophy, even at the expense of short-term financial goals. Create a continuous process flow to bring problems to the surface.

Create a continuous process flow to bring problems to the surface. Use pull systems to avoid overproduction.

Use pull systems to avoid overproduction. Level out the workload.

Level out the workload. Build a culture of stopping to fix problems in order to get quality right the first time.

Build a culture of stopping to fix problems in order to get quality right the first time. Realize that standardized tasks and processes are the foundation for continuous improvement and employee empowerment.

Realize that standardized tasks and processes are the foundation for continuous improvement and employee empowerment. Use visual control so that no problems are hidden.

Use visual control so that no problems are hidden. Use only reliable, thoroughly tested technology that serves your people and processes.

Use only reliable, thoroughly tested technology that serves your people and processes. Grow Leaders who thoroughly understand the work, live the philosophy, and teach it to others.

Grow Leaders who thoroughly understand the work, live the philosophy, and teach it to others. Develop exceptional people and teams who follow your company’s philosophy.

Develop exceptional people and teams who follow your company’s philosophy. Respect your extended network of partners and suppliers by challenging them and helping them improve.

Respect your extended network of partners and suppliers by challenging them and helping them improve. Go and see for yourself in order to thoroughly understand the situation.

Go and see for yourself in order to thoroughly understand the situation. Make decisions slowly by consensus, thoroughly considering all options, and implement decisions rapidly.

Make decisions slowly by consensus, thoroughly considering all options, and implement decisions rapidly. Become a learning organization through relentless reflection and continuous improvement.

Become a learning organization through relentless reflection and continuous improvement.• Business Process Reengineering. Business Process Reengineering (BPR) is a Process Improvement approach that prescribes totally rethinking and redesigning processes in order to achieve improvements. It advocates that organizations go back to the basics and reexamine their beginnings. BPR is not usually seen as a continuous improvement method but rather as a method for organizations that need dramatic and exponential improvement in short order (Reinventing). BPR also focuses on processes rather than on tasks, jobs, or employees. It endeavors to redesign the strategic and value-added processes that exist within an organization.

Agility and Process Improvement

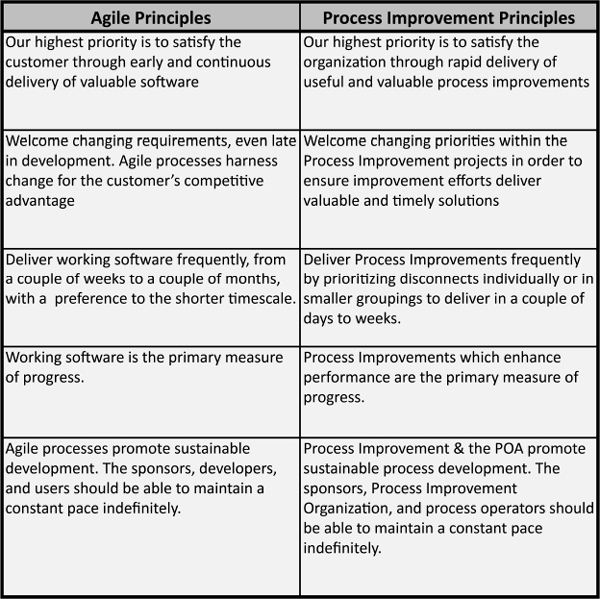

To remain competitive, organizations, regardless of industry segment, must produce products and services that are of consistently high quality and that continually meet the needs of an ever-changing market. In order to do this, organizations must possess the ability to continuously monitor market demand and quickly respond by improving or enhancing processes in order to provide new products, services, and/or information. Agility is a way to assist organizations in this effort and is an iterative method for delivering projects, products, and services faster. The most popular Agile methodologies include Scrum, Extreme Programming, Lean Development, and Rational Unified Process; all have been primarily focused on software development initiatives to date. The primary objective of Agile is to incorporate iteration and continuous feedback in order to drive project efforts and successively deliver solutions. This involves continuous planning, continuous testing, continuous integration, and other forms of continuous evolution of both the project goals and the project’s deliverables. Agility also focuses on a series of principles such as empowering people to collaborate and make decisions together quickly and effectively, delivering business value frequently, and promoting self-organizing teams.

Many of the practices promoted by Agile development can also be applied to Process Improvement activities. For example, one of the most significant reasons for the failure of improvement projects is that project teams focus significant attention on completing tasks in a waterfall-like fashion, whereby all deliverables from one phase of a project must be completed before a project can move into the next phase. This practice can significantly slow down improvements and hinder organizational progress. Application of Agile techniques in a Process Improvement project allows project sponsors and improvement teams to regularly prioritize improvement activities and allows teams to focus on individual improvements or group-related improvements into packages for faster resolution.

Upon analyzing Agile, many of the principles from the Agile Manifesto can be repurposed for Process Improvement and can address many key pitfalls of improvement projects. Figure 6-11 displays several key operating principles from the Agile Software development manifesto and several commonalities and comparative uses in Process Improvement activities.

FIGURE 6-11 Agility and Process Improvement

Performance Management

Performance Management is the basis for sound and rigorous Process Improvement efforts. In order for an organization to have good process and improvement controls, it must be able to see where the organization is truly performing. Having a well-defined set of performance metrics provides management with the means to measure the performance of current processes and measure the success of prior improvement efforts. It also allows management to determine what new areas require consideration in order to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of processes within an organization. More concisely, Performance Management is the ongoing process of ascertaining how well or, how poorly, an organization and its processes are performing. It involves the continuous collection of information on progress made toward achieving objectives as well as the determination of the appropriate level of performance, the reporting of performance information, and the use of that information to assess the actual level of performance against the desired level.

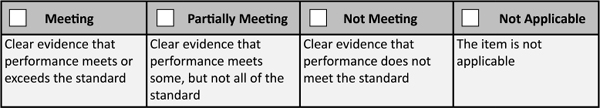

Ongoing Performance Management helps answer the following five key questions:

• What is the current process performance level and is it meeting customer requirements? A sample performance rating scale is outlined in Figure 6-12.

FIGURE 6-12 Performance Rating Scale

• Has performance changed?

• Do we need to adjust the process?

• Do we need to improve the process?

• How will the process perform in the future?

Key Performance Metrics

A performance metric is a specific measure of an organization’s activities. Performance metrics support a range of stakeholder needs, from customers and shareholders to employees. Although many metrics are often financially based, inwardly focusing on the organization’s performance is also critical to ensuring customer requirements are being met. Likewise, an organization can measure almost anything within its processes and operations. Some examples include quantity of defective products produced, cycle time to process an order, and number of outstanding invoices.

Performance metrics can be broken down into the following four distinct levels:

• M0: The Organization Level. These metrics measure the achievement of strategic goals and monitor the organization’s overall return on investment.

• M1: The Process Level. These measures ensure processes deliver the required value at the required efficiency to meet strategic goals.

• M2: The Subprocess Level. These metrics ensure optimum performance of key value-added process steps and alignment with downstream process steps.

• M3: The Performer Level. These measures ensure that the workforce is aligned with the overall process and business goals.

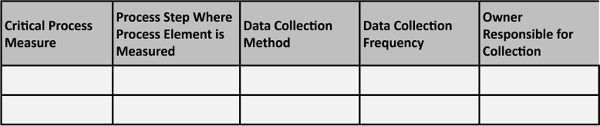

Process Monitoring Plans

Perhaps the most vital tool used for performance management and monitoring is the Process Monitoring Plan. The monitoring plan clarifies how the process performance will be continuously monitored, who will be notified if there is a problem, how that will happen, and what response is required.

The first part of the monitoring plan specifies the metrics that will be tracked to summarize process performance. It also specifies the process steps, where the process will be measured, how the process will be measured (a popular method is to use control charts to display causes of variation), and how often they will be tracked. Another critical step is to clarify who is responsible for conducting this effort; although the responsibility usually falls to the process owner. The monitoring plan also indicates what constitutes satisfactory performance and what should be considered a red flag, indicating possible problems. Figure 6-13 illustrates an Process Monitoring Plan.

FIGURE 6-13 Sample Process Monitoring Plan

Other questions to be answered when creating a comprehensive monitoring plan include

• Why is the organization interested in this variable? What decisions or actions will it inform?

• What activities or events generate potential data points?

• What should be the unit of measurement?

• How frequently should the data be reviewed?

• Are there hidden variables that can have a significant impact on the value of a metric over time?

• Should the data be drilled down to a deeper level?

The measures or indicators selected by an organization should best represent the factors that lead to improved customer, operational, and financial performance (a Balanced Scorecard approach). A comprehensive set of performance measures that is tied to customer and organizational performance requirements provides a clear basis for aligning all processes with organizational goals. Quite often, measures and indicators are needed to support decision-making in corporate environments.

Measurements should originate from business needs and organizational strategy, and they should provide critical performance data and information about an organization’s key processes, outputs, and results. Several types of data and information are required for performance management including product, customer, and process performance; comparisons of market, operational, and competitive performance; supplier, workforce, partner, cost, and financial performance; and governance and compliance outcomes. Regular analysis and structured reviews of performance data should be conducted and may involve changes to better support an organization’s goals as time goes on.

NOTE A Balanced Scorecard (BSC) is a structured dashboard that can be used by managers to keep track of the execution of activities by the staff within their control and to monitor the consequences arising from these actions.

Process Dashboards

The Process Dashboard is a key communication tool that an organization uses to summarize process performance. It indicates the overall health of a process in a concise manner by providing a visual picture of the process through data diagrams and charts. It is primarily used for executive reviews but also serves as an excellent tool for management and process owners. The Process Dashboard provides the means for detecting defects and problems and for troubleshooting any variation that may exist in a process. The indicators and gauges used on Process Dashboards should tie to process goals, customer requirements, and strategic objectives. Process Dashboards help effectively communicate process performance to operators, champions, and stakeholders. Figure 6-14 outlines a basic Process Performance Dashboard.

FIGURE 6-14 Sample Process Performance Dashboard

In planning for the design of a process dashboard, practitioners should select the charts that best display process performance and results. To do this, practitioners must first decide what the process dashboard should say or describe about the process it is monitoring. Some key questions to consider when developing a Process Dashboard are

• Is my process capable and is it meeting customer requirements?

• If it is not meeting customer requirements, what might be driving the lack of capability?

• How much variation is in my process?

• What types of metrics should I include (e.g., cycle times, sales figures, accuracy rates, sigma levels, defect rates, repetition rates)?

• How do I want the information displayed to my stakeholders and my leadership team (Steering Committee)?

• To what level do I want to drill down in the information?

• How might I want to segment the information for making critical decisions?

• Who should have access to the information?

Once the basic format for the performance dashboard has been decided, it is time to gather the relevant data. Figure 6-15 provides an overview of some of the general charts and tools used for displaying information in a performance dashboard.

FIGURE 6-15 Performance Dashboard Charts and Tools

Process Enablers

In order to truly assess and improve process performance, process stakeholders must understand why a process might be performing in a particular manner. Once measures have been established and owners and monitoring plans have been implemented, organizations can then begin to determine the reasons for process performance and initiate subsequent improvements if necessary. The following six common process enablers are used to determine how a process behaves:

• Process Design: The activities, sequence, decisions, and handoffs within a process

• Technology: The systems, information, applications, data, and networks used within a process

• Morale and motivation: The organization’s systems that are concerned with how people, departments, and processes are measured and the associated consequences (reward and punishment) that go along with them

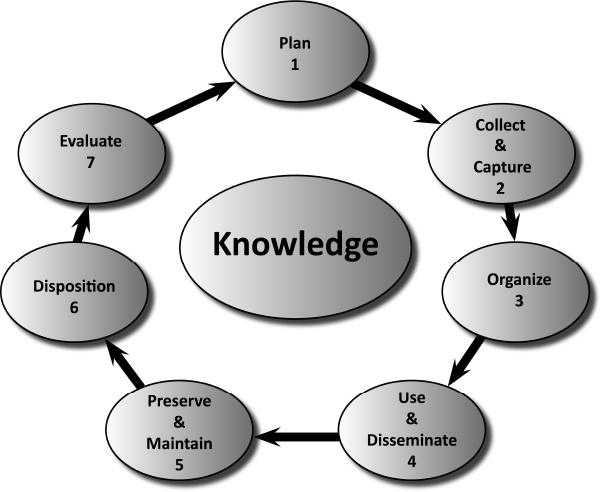

• Workforce: The knowledge, training, competencies, skills, and experience of the workforce as well as the organizational structure and job definitions of employees