CHAPTER 1

Saxon and Norman

Saxon and Norman

Churches

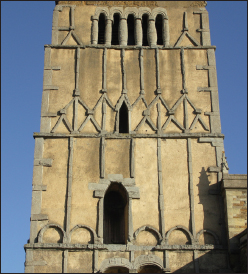

FIG 1.1 BRASSINGTON, DERBYS: This church set on the edge of the Peak District was built in the 12th century, yet as with most examples from this period the evidence is buried under later changes. The stocky, plain tower with its distinctive round-arch bell openings is the only part in this picture which is instantly recognizable as Norman.

In the closing decades of the 6th century Britain found itself under invasion on two fronts. Not from further bands of pagan Saxons who over the previous hundred years had pushed the existing Romano-British and their culture into the West, but from Christian missionaries seeking to convert the population (in effect, to reintroduce a religion which had established itself in the last century of Roman rule). St Columba, who had travelled over from Ireland and founded a monastery on Iona in AD 563, and his followers influenced the North while Augustine, sent by the Pope, had landed in Kent in AD 597 and established a base in Canterbury (London was resolutely pagan!). The inevitable differences between the two as they spread across the country was ironed out at the Synod of Whitby in AD 664 and, over the following century, a system of a regional central minster dispatching preachers to outlying field churches or open air sites was created.

Viking raids and later invasion during the 9th century ruined monastic life and crippled the Church until Alfred and his successors forced them back and established England as a single state by the mid 10th century. Under Edgar (AD 944–975) church building flourished, now not just minsters but new, smaller estate buildings, as lesser nobles sought to gain higher status by erecting a church next to their manor house, a fashion which continued over the next 200 years. At the same time the payment of tithes to support the priests was put in law and a parish from which they were to be paid was established, many following the boundary of these local estates. The majority of our medieval parish churches are likely to have been founded this way by Saxon nobles and after the Conquest by Norman barons until the late 12th century when the old minster system was virtually obsolete.

Saxon Churches

Part of the success of the early missionaries is likely to have been due to their adoption of existing pagan religious sites, and many early churches were built alongside holy wells, ancient stones, burial mounds and Roman remains. They were usually simple rectangular structures, mostly built from timber and have long since gone (an exception is in Fig 1.17); those which survive are the ones built in stone. These relied upon the bulk of their walls for stability and the thickness was exposed at the windows which were typically small with many splayed on both sides so the shutter or material used to close them off was in the centre (glass was rare).

FIG 1.2 STOW, LINCS: This outstanding example of a large Late Saxon cruciform church dwarfs the tiny village around it. Its size and dominant position are clues that it was once an important minster. These early principal churches were mainly established in the 7th and 8th centuries near important centres of the day and acted as a missionary base from which priests or monks could go out and preach to other communities within a territory. The creation of parishes from the 10th century broke down this system. Their presence is also still recorded in place-names like Kidderminster, or where they became a cathedral as at York Minster.

The main body had a distinctive tall, narrow form, most with a smaller chancel built onto the east end and a few larger churches having transepts to the sides and a tower. Where the wall had to be supported above a window, doorway or the opening between the nave and chancel, a simple round arch was used, typically narrow with tall sides. The roof above would have been steeply pitched and most likely thatched.

FIG 1.3: Churches built near ruined Roman towns or villas often raided their masonry (see Fig 1.18) for thin red bricks, then incorporated them into walls and arches as in this example at Brixworth (top). A distinctive feature of Late Saxon and Early Norman churches was the laying of stone in a herringbone pattern as in this example from Marton, Lincs (bottom).

Most of what you see today from this period will be fragmentary. Of the couple of hundred churches that display their Saxon origin, this is usually only indicated by the distinctive narrow profile of a nave or a single round headed window.

FIG 1.4: A distinctive feature of Saxon churches was long and short work, where narrow stones were alternately placed vertically and then horizontally on the corners (quoins).

FIG 1.5: Windows were usually small with a single and occasionally a twin opening (often with an elongated barrel shaped baluster in the centre). Most had a round head, smaller ones crudely carved out of a single block (top), larger examples with the arch formed out of carved segments (centre). A unique form on some Saxon churches was the triangular head (bottom).

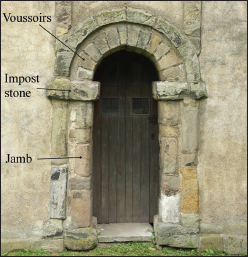

FIG 1.6: Doorways (and the chancel arch inside) were typically simple and narrow with a lack of confidence in the size of the round arch limiting their width. They have a large impost stone from where the arch springs and occasionally attached columns.

FIG 1.7: Columns and the capitals on top of them are only found in a few Saxon churches. They are simple in form, often with decorative carving (the Saxons were in some ways more skilled craftsmen than the later Normans).

Norman Churches

William the Conqueror’s bloody arrival on these shores was followed by a large-scale building of castles and cathedrals; imposing structures designed to leave the rebellious Saxon population in awe. Apart from these there were few major churches built, it was the continuing pattern of local lords erecting new places of worship alongside their manorial homes which dominates this period. Parish churches found next to earthworks of motte and bailey castles are a common remnant of this link. However, a drive for a more pious Church during the 12th century encouraged these secular owners of churches to surrender the rights they had to appoint priests and collect revenue for services (part of the motivation for many to build the church in the first place) and place them into the hands of bishops and monasteries.

These early Norman churches have much in common at first glance with the simple, narrow Saxon structures except that an apse, a semi-circular extension to the chancel, was a popular import at this time from France. Towers were not common in most areas although on major buildings a cruciform plan with a central square structure above the crossing was a popular and distinctive feature. The round arch was always used for openings; the inability to make it wider without making it higher in proportion limited the width of windows and doors although there are a few impressive attempts at large chancel arches, albeit distorted! Where a wall had to be supported over a long space (usually between the nave and side aisles) a row of round arches was supported upon thick square piers or broad round columns, the latter with crude blocks at the base and plain capitals on top.

FIG 1.8: Example of a large Norman church with labels of characteristic features. The exterior is shown covered in whitewash with colour painted around openings. Although this is just conjectural it is likely that many churches had some form of exterior coating and decoration.

By the mid 12th century these churches suddenly begin to flourish with decoration and a distinctive Norman style emerges with vibrant geometric carvings.

FIG 1.9: Some doorways had a square head with the semi-circular space above (tympanum) filled with a carved pattern or scene as in this exceptional example from Kilpeck, Hereford.

FIG 1.10: Important entrances had recessed doorways with receding arches, as in this example from Steetley, Derbys. The row of beakheads above are Norman in style but date to restoration around 1880.

FIG 1.11: Windows were either singles or in pairs under a round arch and set high up in the wall. The shutter or cloth (glass was too expensive for most parish churches at this date) was now on the outer edge so they had just a deep single splay on the inside. This example is a former belfry opening at Burford, Oxon, which has later been glazed.

FIG 1.12: The round arch was also used to decorative effect by forming a horizontal band of repeated or interlocking blank arches called blind arcading. They have been used here between the distinctive Norman belfry openings on a round tower. These feature mainly in Norfolk and Suffolk and are usually Saxon or Norman in date.

FIG 1.13: Corbels (stone brackets) were often fitted under the lower edge of a roof. These formed corbel tables or shelves (top) and are a distinctive feature of Norman churches. They were usually carved with heads and figures (bottom) as with these examples from Kilpeck, Hereford.

FIG 1.14: Later Norman churches were distinguished by decorative carving, most notably the zig zag or chevron pattern around arches. These usually point the eye towards the opening but can occasionally be found placed on their side around the arch, pointing outwards (see inner arch in Fig 1.11), a detail usually dating to around 1160. The example above shows bands from right (inner edge) to left of beakheads, chevrons, pellets (round beads) and billets (alternately spaced square blocks). Other decorative forms included diamond patterns, a band of rope design and lozenges (flat diamonds).

FIG 1.15: Norman columns were generally stocky but became gradually thinner compared with earlier types. They could be round or octagonal and sometimes alternate in the same arcade, some with patterns carved down them. Capitals usually had a square top, often with just a plain chamfered block below shaped like a cushion. This could be further decorated with scallops (left) or volutes (right) as in these late 12th-century examples from Youlgreave, Derbys.

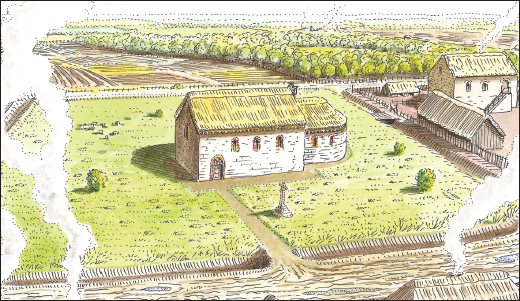

FIG 1.16 EXEMPLAR CHURCH c1100: This first visit to Exemplar church shows the simple stone building with a thatched roof adjacent to the manor house (right), the residence of a Norman baron who was responsible for initiating its construction. It replaced a smaller timber structure which had been the first church on the site and had a rounded apse added onto the end of the chancel. The only feature in the churchyard is a stone cross, as graves rarely had permanent markers at this date.

STILL OUT THERE

FIG 1.17 GREENSTED, ESSEX: A unique survivor of a wooden church of which only the shortened vertical timbers in this picture date from the Saxon period. Most churches built in this period would have been in this material and it is only when later ones are excavated that the impression of the post holes of these earlier structures are sometimes found underneath.

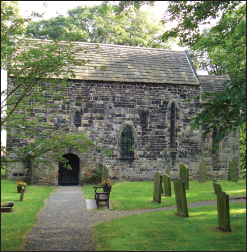

FIG 1.18 ESCOMB, COUNTY DURHAM: One of only a few examples of largely unaltered Saxon churches with its distinctive tall, narrow nave and tiny windows (the large one in the centre and the narrow ones to the right are later additions). Roman masonry from nearby Binchester Fort is thought to have been used in Escomb’s construction (note near the top of the wall it looks like they ran out and had to use smaller stones for the final courses).

FIG 1.19 BRIXWORTH, NORTHANTS: This largest surviving early Saxon church (late 7th-century) like many others suffered destruction by Vikings, typically during the late 8th and early 9th centuries. The apse in the foreground was rebuilt around AD 1000 with a polygonal shape (they could also be round or square). The main body has the distinctive tall, narrow shape although the top of the tower, the spire and pointed windows are later additions.

FIG 1.20 EARLS BARTON, NORTHANTS: One of a number of distinctive late Saxon towers with triangular and round headed openings, long and short work and decorative stone strips. These vertical pieces may be replicating a form of construction used on timber churches at the time. Towers were not common on parish churches in most areas except in East Anglia where distinctive round ones may have also played a defensive role (see Fig 1.12).

FIG 1.21 STEWKLEY, BUCKS: Later Norman churches are distinguished by a riot of carving and bold geometric decoration as in this west end of a largely unaltered church. The nave, tower and chancel in a single line with no transepts is a form associated with this period. Simple round windows as in the gable in this picture can often be found on larger Norman churches.

FIG 1.22 KILPECK, HEREFORD: This notable little church is famous for its carving but has also retained its original form, one which was typical of many smaller parish churches in the Norman period. Having the nave, chancel and apse in a line with just a belfry and no tower was repeated all across the country.

FIG 1.23 STOW, LINCS: A view from the nave looking towards the chancel at the far end of the interior of this Saxon minster church most likely dating from just before the Norman Conquest. The round arch in the foreground has the distinctive tall and narrow profile and the windows to the side are deeply splayed and high up in the walls. The space just beyond the arch is the crossing, the area under the tower, which in large Saxon churches was the climax of the building (the pointed arch you can see dates from a later period, probably when the tower was heightened).

FIG 1.24 TICKENCOTE, RUTLAND: This tiny church is a feast of Norman decoration yet most dates from an exuberant 18th-century restoration. The major part they left untouched was this huge chancel arch which despite sagging in the middle has stood for more than 800 years. It is distinctive Late Norman work with receding arches decorated with chevrons, beakheads and billets and narrow cushion capitals carved with scallops and symbols.

FIG 1.25 BAKEWELL, DERBYS:A view of the west end of the nave arcade showing on the right a narrow, round Norman arch with thick square piers and prominent impost stone and on the left a later pointed arch with much thinner columns (actually Victorian but based on medieval work). It illustrates what you will find in the next chapter, that the pointed arch helped make the interior of churches lighter and more spacious.