CHAPTER 9

The Churchyard

The Churchyard

Crosses and Memorials

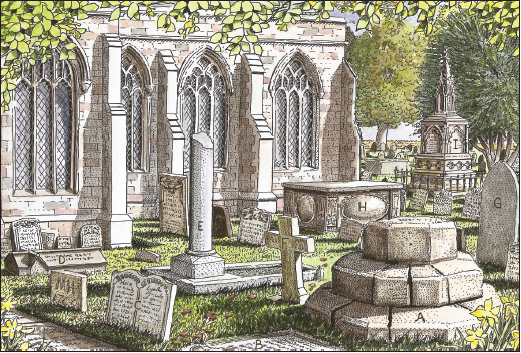

FIG 9.1: Haunting, peaceful and mysterious, the churchyard with its irregular display of tilting, ivy-clad gravestones is as memorable as the church which stands roughly in the centre of it. Some could have been used for over a thousand years and contain ten times as many graves, such a displacement of soil that the area can be many feet higher than the surrounding land! Over such a time they have also changed their appearance and use and their present form is in many cases a relatively modern creation.

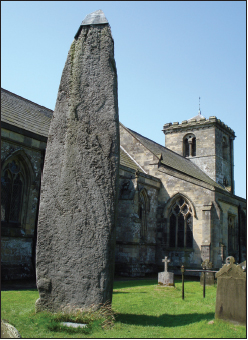

Mystery and superstition surrounds the origins of God’s Acre. Some churchyards are certainly of ancient foundation – the presence of prehistoric stones and burial mounds on a number of sites shows that they have been sacred for thousands of years and that the Christian Church is just the latest incumbent. Some of these plots have a circular plan although this shape is not conclusive proof that it was either established in prehistory or by the early Celtic converts.

The first mention of a churchyard distinct from just a cemetery was not made until the late 8th century and probably contained a minster or church, a large cross and a graveyard, the boundary of which was originally marked out by small wooden crosses. Many churchyards may have been founded before a permanent building was erected, and would have contained just a wooden or stone preaching cross and perhaps the grave of a local dignitary or founding missionary which attracted further burials around it (see Fig 9.3).

FIG 9.2 RUDSTON, YORKS: This huge monolithic stone dates from prehistory and retained such sacred value that later the church was built alongside. The churchyard is also of a roughly circular plan which it shares in common with many other early sites. Another notable example is at Taplow, Berks, where an ancient burial mound within the graveyard was opened, revealing one of the richest early Saxon graves in the country.

Throughout the Middle Ages the churchyard was a communal area and, although revered, it served a function more than just a burial ground. In many places it was the only large public space so was used for fairs, plays, sports and celebrations, usually with a religious connection. Stalls were pitched in the grounds or in the church itself and on some urban sites permanent shops were built along the edge of the churchyard by a clergy never afraid to seize a business opportunity. There would have been a number of structures within the grounds, which could include a priest’s house for the incumbent to live, a charnel house (or ossuary) in which bones from old graves were deposited, and a timber cage which would hold the bells at ground level before a tower for them became common.

The profusion of trees that characterize most churchyards today are generally an 18th- and 19th-century fashion; in the medieval period they would have appeared more open. Yews could have been found, some perhaps used as a grave marker. Willows or brambles were planted by families wishing to protect the resting place of loved ones from grazing animals kept there by the priest, a problem which seems to have been more widespread after the Reformation and included the occasional building for animals on this hallowed ground. The most notable difference, though, would have been the lack of gravestones as the few who could afford a mason chose to be buried inside the church. It is likely that there would have been a large cross and then just an open area of hummocks, only broken up by a few small wooden markers or larger grave-boards on the more recent burials, which would quickly rot away.

FIG 9.3: The most notable remnants from Saxon churchyards are stone crosses, as in these examples from Bakewell, Derbys (left), Sandbach, Cheshire (centre) and Leek, Staffs (right). The largest are most likely to have been preaching crosses, consecrating the ground and marking the site for daily worship, in some cases probably before a church was erected. Other smaller stone crosses and slabs possibly marked an important grave. Some are bursting with carvings of scenes from the Bible, designed to educate the illiterate masses as medieval wall paintings in churches would later do (centre), others are much worn with limited decoration (right). Many Saxon crosses were destroyed in the hundred years after the Reformation, while their parts eroded over time, so that today most only survive in sections and are probably not in their original location.

By the 18th century the churchyard began to take on its more familiar modern appearance; trees were deliberately planted around the outer edge and topiary became popular. Boundary walls and fences replaced earlier ditches and banks, sometimes with the names of parishioners who paid for a section carved upon them.

FIG 9.4: Although there were few gravestones before the mid-17th century most churchyards would have had a cross marking the consecrated ground. These prominent symbols were usually erected upon a stepped base but were easy targets for destruction in the century after the Restoration and few remain intact. What is commonly found, however, is the worn base on the south side of the church, sometimes with a Georgian sundial or Victorian replacement for the original cross mounted on top.

FIG 9.5 CORBRIDGE, NORTHUMBERLAND: A humble residence for the incumbent was a common feature in the medieval period before more spacious vicarages and rectories were built. Most were probably of timber and are long since gone but this notable stone example at Corbridge survives. It was a fortified tower house to protect those inside from Scottish raiders, built around 1300 and had room on the ground floor so the priest could drive in his cattle and then use the floors above for accommodation.

FIG 9.6: Lych gates are the point where the coffin bearers traditionally had to wait for the priest to welcome the deceased onto the consecrated land. Most today have a timber gable roof, gates and occasionally a bench or slab for the coffin to be placed upon, and they date from the last two centuries though some are older if only in part. This was an important feature as many remote chapels did not have consecrated burial grounds until the 19th century and the funeral procession had a five or ten mile walk along so-called ‘corpse roads’ to get to a churchyard.

Gravestones began to be erected especially after the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, of simple design at first, then by the Georgian period more elaborate until in Victorian times a wide range of monuments of more affordable price began bursting the limits of the churchyard.

The boom in the population and the still hideous death rate in some areas around the turn of the 19th century put excessive strain on urban churchyards. Graves had always been dug through older burials but now the demand was such that God’s Acre was inadequate and new sites were required. This encouraged speculators to offer private burial grounds as an alternative though many of these were no more than a chapel with hundreds and even thousands of coffins literally stacked up and rotting away in the basement. The stench was intolerable and the service provided so poor that the numerous complaints coupled with concerns about public health resulted in the banning of burials within a church from the late 1840s. The important members of the community now found themselves out in the open and so they created ever more elaborate Gothic memorials to differentiate themselves from the common gravestones around. New landscaped private cemeteries were an alternative for the better off and after legislation in the 1850s public versions set in similar parkland were laid out on the edge of most towns and cities. The problem with overcrowding was in part alleviated with the legalization of cremation after 1885.

Graves and Memorials

Like the church itself, Christian graves are aligned from east to west, a distinguishing factor when archaeologists excavate Saxon burial grounds (earlier pagan Saxon graves do not have a set orientation). One reason for this is believed to be that at the Second Coming the dead will awake and face the rising sun in the east; however, this alignment is not unique to Christian graves and there may be other long forgotten reasons associated with sun worship.

FIG 9.7 LONG MELFORD, SUFFOLK: It is common to see a rectangular field added on to the side of the original churchyard to increase burial space in the past century or two, mainly in rural locations. When the old boundary is removed between the two a bank usually remains so you have to step down into the new undisturbed plot. This has often been enhanced by the displacement of soil caused by constant reburials over maybe a thousand years, which has raised the level of the churchyard sometimes by as much as five or six feet over the surrounding land. Trenches around the church have often been created by the same action.

The cold and shaded north side of the churchyard was unpopular and associated with evil so medieval burials were rare (it is likely that this area was used for entertainment and fairs due to this lack of graves). Later it was often used for strangers, suicides and unbaptized children, until the 18th and 19th centuries when pressure for space put it into general use. The sunnier south, especially around the east end (‘as near to the altar as you could’ was just as relevant outside as within the church) was seen as the best spot and is usually where the better off were buried.

It is still the practice to reuse plots, sometimes after as little as 100 years. Although you would expect to find the oldest graves close to the building and the more modern further away, this regular digging through old graves means that Victorian memorials can often be found next to the church and then any older Georgian gravestones which were never reused a little further out.

Pre-Victorian graves could vary greatly in depth with some barely more than a foot deep. Paupers often had their coffins collected in a large shallow pit which was only covered up when sufficiently full. It was also the practice for the text on the gravestone to face away from the burial, often with a smaller foot-stone to mark the other end, until the mid-19th century when it was reversed to look over it. Foot-stones are rarely found in situ now but have been re-positioned to rest up against the headstone. To make mowing the grass easier it is common for old gravestones to be re-sited up against the boundary wall.

Gravestones

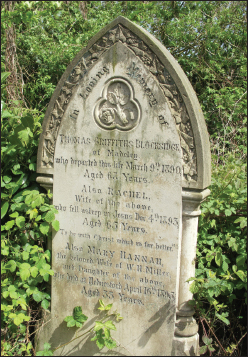

Gravestones are the most characteristic feature of the modern churchyard, packed with information about families, life expectancy and society at the time of burial. The text on some slates can seem remarkably fresh even after centuries (the best survivors are in the Midlands and South-West); other stones, however, weather and split, with the shape and size of the stone the best clues to date it (the spread of lichens can also be used to date stones as they grow so slowly).

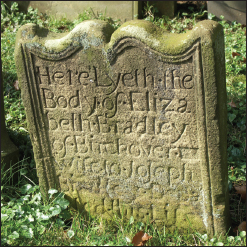

FIG 9.8 YOULGREAVE, DERBYS: Some of the earliest gravestones from the late 17th century were no more than a short thick stone with the initials and date of death. Larger ones had text as above but clumsily laid out with words split between lines.

The availability of materials and the cost of a mason made gravestones rare before the late 17th century and only common in the 19th when transport costs dropped and workshops became widespread. Even then it was still a large outlay for poorer families which could often only be achieved through clubs and societies.

FIG 9.9: The head of an early 18th-century gravestone with symbols reflecting the morbid obsession with time and mortality. A common symbol used in the late 17th and early 18th centuries is the skull and crossbones, not a pirate’s burial but a sign for mortality used at least since the medieval period on memorials (the skull and two thigh bones are believed to be the parts of the body required for the resurrection). Hourglasses remind us of our mortality and angels or a cherub’s head with wings represent the soul flying up to heaven, and sometimes a symbol of the deceased’s trade, like a sheaf of corn for a farmer, was used.

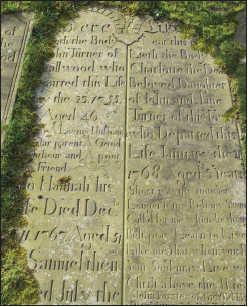

The earliest gravestones which you are likely to find in churchyards today will date from just after the Restoration in 1660, and these are rare, with many having nothing earlier than the 18th century. Most of these early stones were only a few feet high, some no more than posts or stubby, thick slabs, often with just the initials of the deceased. On more elaborate examples the head of the stone contains crude symbols associated with mortality and time under a hood mould or scrolls while the text below is often clumsily fitted in. Most will have sunken so appear shorter than when originally set and this can often obscure the dates and other information at the bottom.

FIG 9.10: Details from Georgian gravestones from Long Sutton, Lincs. Skulls and angels or cherubs’ heads remained popular in the first half of the 18th century before the full bodied variety of the latter became more common. Honour and glory could be symbolized by the crown, often with clouds, while the dove was a popular centrepiece in the last quarter of the century. The trumpet was also a widely used symbol heralding victory and resurrection.

Georgian gravestones develop from these early decorative types into a flourish of Rococo style during the mid century and later more refined Greek Revival in the Regency period. The size of the slab grew in some cases up to 6 ft tall and the profile of the head changed from elaborate curves to more simple geometric shapes by the early 19th century. Locally established masons were now more widespread and designed a wide range of beautifully decorated memorials for the better off members of society, some even coloured with paint and gilt, although this faded often in just a matter of months.

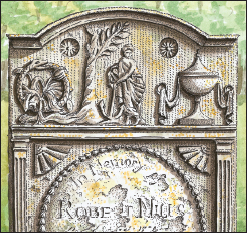

There was also a change in social attitudes towards the grave in the early 19th century; no longer was it just a place where the body was deposited but was now seen as the property of the family, which they would regularly visit, and could be defined by railings or stone kerbs. The symbols at the top became less gruesome, with elegant ladies weeping under willows and an urn often with fabric draped around it the most common from the late 18th century through to the mid 19th.

FIG 9.11: Rococo style gravestone with deep foliage and convex centrepiece.

FIG 9.12: The Greek Revival style of architecture began influencing gravestone design from the 1770s and the distinctive shallow Classical decoration with symbols like the urn, medallions and Greek key were popular through the Regency period. As in this picture, a mourning figure (still referred to as a weeper) under a willow with an urn was a common arrangement.

The reinvigorated Church of England and the Gothic Revival of the 1840s began to influence the design of memorials. They reviled the ornate Georgian classical gravestones and promoted plain slabs made from local materials and featuring the cross (something which had been absent since the Reformation for fear of Popery), accompanied by a healthy donation to the church. They had some effect in urban churchyards but less so in the country. In the new municipal cemeteries the Gothic style was incorporated alongside the Classical, but discretion was not the order of the day, and elaborate gravestones, rustic crosses, and weeping angels standing above a grave framed by a cast iron surround or stone kerb dominated. Imported white marble memorials from Italy were increasingly popular and cheaper than domestic versions, taking work from local quarries, while architect-designed gravestones were produced en masse in towns, taking trade from local masons already struggling with a shrinking rural client base (reorganization of villages meant fewer wealthy landowners).

FIG 9.13: Double gravestones with two profiled tops were usually made for husbands and wives or other family members. However, in this case the other half was never completed, making you wonder what happened to poor Augustine’s wife after his demise!

FIG 9.14: There was a wide range of Victorian gravestones although most had a steep pointed Gothic arch as above. Crosses and weeping angels were also popular. The 19th-century text is usually heavier, more regular and deeply incised than the ornate and flowing Georgian types, and highlighted in lead, black or gilt. A wide range of different stones characterizes Victorian graveyards and it was common for them to be mixed in one memorial or feature insets of brass or tiles.

Ledgers, Mausoleums and Tombs

An important grave in the past could have been marked by something more elaborate than just a gravestone, ranging from a ledger (a horizontal slab) to elaborate chest tombs or occasionally even a family mausoleum. In the Saxon and early medieval period only ecclesiastics were usually permitted to be buried within the church so there would have probably been some wooden and stone carved memorials in the churchyard for laymen. During the medieval period a stone slab with a simple cross running its full length was a common memorial for important members of the community inside and outside the church. Coped stones, resembling a squat cruciform church, with text running down the sides or raised to form gabled house tombs were used into the 17th century, and then revived by the Gothic-obsessed Victorians.

Chest tombs have a ledger raised up upon a hollow rectangular stone box with the grave in the ground below. These most splendid of churchyard memorials can be found dating back to the early 17th century and occasionally before but are commonly from the 18th century.

Some are no more than a flat ledger raised upon the chest, featuring a few pillars, but the more decorative examples can have elaborate figures supporting panels in the sides. The style of these features very much follows those of gravestones except the figures are in full rather than just the head, with deeper, richly carved work from the late 17th to mid-18th centuries followed by shallow Greek Revival patterns through to the early Victorian period. The Victorians, however, preferred the emphasis on the vertical and although there are chest tombs richly decorated with Gothic symbols, the obelisk, pillar and shrine memorials are more common, especially in cemeteries.

FIG 9.15: Flat slabs known as ledgers set horizontally over the grave can be found flush with the ground or raised upon a plinth and are common from the mid-17th century onwards. These are more likely to have most of their inscriptions exposed compared with gravestones which have usually partially sunk. This example comes from Cheshire, a county along with Lancashire where it was common for them to be laid in a row along paths. Note the different text, showing how a family has reused the plot over more than 100 years.

FIG 9.16: Late 17th- and early 18th-century chest tombs. The oldest types tend to have a large, heavy slab on top and a thin body (top) with finer examples having decorated sides. These usually have pilasters to the sides and figures surrounding a central plaque (bottom) with the details reflecting the obsession with symbols of mortality and architectural fashion.

FIG 9.17: The finest chest tombs from the 17th and 18th centuries are to be found in the Cotswolds. Those in the eastern part tend to have a peculiar semi-circular slab across the top, known as a Bale Tomb (top) from the wool-bale used by the merchants who tend to be the main occupants of the graves. However, it is more likely to represent the medieval hearse, a curved cage built over the body to support the pall (funeral cloth). In the western part the Flamboyant Tomb (bottom) is common, which has a thick plain slab but richly-carved side panels, often with a couple of scrolls at the ends.

FIG 9.18: Late 18th- and early 19th-century tombs are decorated with delicate Neo-Classical patterns and details. A table tomb, a horizontal ledger supported on stone columns, was often used in the northern counties.

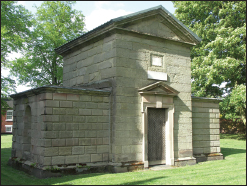

FIG 9.19: Occasionally a wealthy local family would choose to bury themselves and their heirs in a mausoleum set in the churchyard. Most of those found date from the 18th century as in this example from Stone, Staffordshire.

FIG 9.20: Victorian tombs had a clear emphasis on the vertical and were highly decorated with Gothic pointed arches, columns and capitals. They could range from the simple obelisk to ostentatious multi-tiered piles capped with a spire. Some were even made from cast iron (right) and most would have been surrounded by railings (often ripped up for scrap metal in the Second World War).