the sabbats and

the wheel of the year

A Witch’s High Holidays

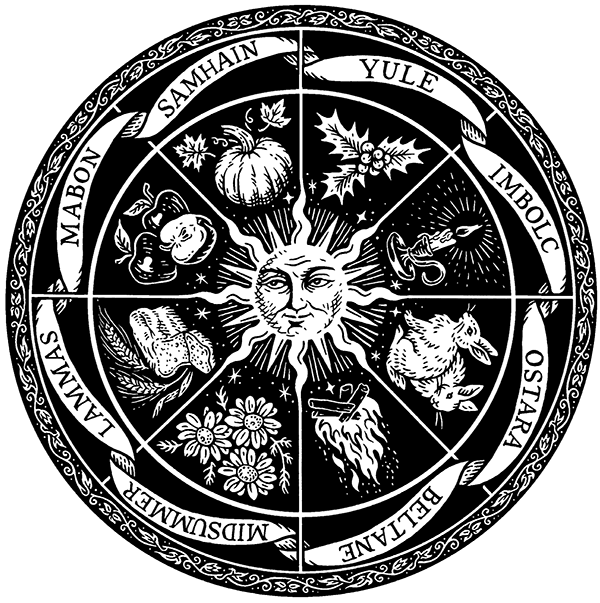

While the Wheel of the Year sounds rather complicated and flashy, it’s really just a term for one calendar year. During that period of time, it’s possible to watch the world go from life (spring/summer) to decline (autumn) and finally to death (winter), before beginning the cycle all over again. This is probably easiest to see in trees, with their annual shedding and regrowth of leaves, but it also applies to most flowering plants. In addition to life and death, there’s also the annual increase and decrease in daylight during one calendar year. (And depending on where one lives, this might be the best way to keep in touch with the turning of the seasons.)

Throughout the course of the Wheel of the Year, most Witches celebrate eight sabbats (figure 1). Those eight holidays include the Winter and Summer Solstices, the Spring and Autumn Equinoxes, and four cross-quarter days, which occur at approximately the midpoint between each solstice and equinox. While eight sabbats are the most common way to divide up the Wheel of the Year, a Witch can choose to celebrate as many sabbats as they wish. If you want more holidays, go for it, and if you want to celebrate fewer holidays, that’s fine too. The Pagan tradition of Feraferia, for instance, celebrates a ninth sabbat in the month of November near the US holiday of Thanksgiving.

The word sabbat most likely comes from Old French and derives from the Hebrew Shabbath, which means “to rest.” 7 If the word sabbat reminds you of the word Sabbath, that’s not a coincidence. During the Middle Ages and the early modern period, Witch celebrations were often called witch’s sabbaths, the term referring to any alleged gathering of Witches. In most English books detailing the activities of Witches printed before the 1950s, Witch gatherings are almost always referred to as sabbaths.

In Dr. Margaret Alice Murray’s (1863–1963) highly influential book The Witch-Cult in Western Europe (1921), she refers to gatherings of Witches as sabbaths.8 However, her book includes material from the French Witch trials in French, including the word sabbat, which is where the earliest Modern Witches most likely took the word from. By 1954, Gerald Gardner (1884–1964), the world’s first modern, public, self-identifying Witch, was using the word sabbat exclusively as a name for the holidays of Witches in his book Witchcraft Today. We’ve been using it ever since.

In Witchcraft Today, Gardner lists the four great festivals of Witchcraft as “May eve, August eve, November eve (Hallowe’en), and February eve.” He then notes that they correspond to the four Gaelic fire festivals of “Samhaim or Samhuin (November 1), Brigid (February 1), Bealteine or Beltene (May 1), and Lugnasadh (August 1).” 9 Because these four holidays were among the first to be celebrated by public Witches, they are often known today as the greater sabbats, though most Witches today don’t call them “May eve,” “August eve,” etc.

The four greater sabbats as we know them today are often thought of as “Celtic” holidays, which is both right and wrong at the same time. There’s no evidence suggesting that all of the Celts in the ancient world celebrated the sabbats, but we know that at least the Celts in Ireland did (and possibly those in Wales, since similar holidays are referenced in Welsh mythology and tradition too). Samhain, Imbolc, Beltane, and Lughnasadh were all originally Irish-Celtic holidays and were eventually imported into the rest of the British Isles, where they’ve been celebrated to varying degrees ever since.

By the close of the 1950s, many Witches had begun celebrating the equinoxes and solstices in addition to the four greater sabbats, but these holidays were generally seen as somehow “lesser” and were often celebrated on the full moon nearest to their actual date. By way of contrast, the greater sabbats were generally celebrated on their actual date and, according to Gardner in his 1959 book The Meaning of Witchcraft, were typically occasions for large gatherings of Witches. (He writes that “all the covens that could gather together would do so” at the greater sabbats.10 )

In the late 1950s, the names of the greater sabbats began to evolve as well, with Gardner giving their names as “Candlemass, May Eve, Lammas, and Halloween.” 11 Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, those names would continue to evolve, with the Irish-Celtic names becoming more and more common. In 1974 Raymond Buckland used the names (and spellings) Samhain, Imbolc, Beltane, and Lughnasadh for the greater sabbats in his book The Tree: The Complete Book of Saxon Witchcraft, and as the years progressed, those names became more and more widely used. (Buckland was not the first person to use those names, but having them in print certainly helped popularize them.)

Today the greater sabbats are generally known as Samhain (October 31), Imbolc (February 2), Beltane (May 1), and Lammas or Lughnasadh (August 1), though the names and even dates of the sabbats sometimes vary from Witch to Witch and group to group. It’s also worth pointing out that the cross-quarter dates for the greater sabbats are often a little off. October 31 is not exactly between the Autumn Equinox and the Winter Solstice. For this reason, there are some Witches who celebrate the sabbats astrologically, meaning on the date closest to the actual midway point between the solstices and equinoxes.

The equinoxes and solstices, or the lesser sabbats, continued their own evolution. In 1958 a Witch coven wrote to Gardner and asked if the equinoxes and solstices could be moved to their actual dates and given the same level of importance as the cross-quarter sabbats. Gardner agreed and thus ended up creating the standard eightfold Wheel of the Year cycle, and this pattern was later adopted by dozens of Pagan groups around the world.12 (This change obviously did not occur early enough to affect Gardner’s book that would be published the following year.)

By the early 1970s, the solstices were commonly being referred to as Midsummer and Yule by most Witches, and for good reason. Yule is a genuinely old Germanic holiday originally celebrated on the winter solstice, while summer solstice rites can be found in the historical record all across Europe. In England, the Summer Solstice was often called Midsummer, and this made sense to many Witches. (If Beltane is the start of summer, then by extension the Summer Solstice would be in the middle of summer.) Because there are no ancient celebrations of the spring and autumnal equinoxes, those holidays were simply called the Spring Equinox and the Autumn (or Fall) Equinox. (That’s right, there were no specific holidays celebrated on the equinoxes, a fact that surprises many people.)

Today, the equinoxes are most commonly referred to as Mabon and Ostara, names first suggested by American Witch Aidan Kelly in 1974. Kelly was looking to do two things with his new names for the equinoxes. The first was to come up with something more poetic than Autumn/Spring Equinox, and the second was to use names that matched up better with the Irish-Celtic names used for the greater sabbats. While working on a Witchcraft calendar that year, Kelly added Litha as the name of the Summer Solstice for good measure.13 (We’ll come back to Kelly’s names later in this book when we look at the individual sabbats.) Kelly’s names were reprinted over the years in various Pagan magazines, and by 1979 (just five years later) they appeared in Starhawk’s seminal work The Spiral Dance. (Surprisingly, though Starhawk mostly uses the Irish-Celtic names for the greater sabbats, she uses Brigid for Imbolc.)

Though there are many Witches today who object to Kelly’s terms for the Summer Solstice and the equinoxes, they are impossible to escape. Most every Pagan I know refers to the Fall Equinox as Mabon, and while I may not like the name too much myself, people know exactly what I’m talking about when I say it. For that reason, I use the words Mabon and Ostara in this book generally when writing about the equinoxes, even if there are some Witches who frown upon their use.

As this book progresses, we’ll spend a little more time with each sabbat, but that’s the evolution of the modern Wheel of the Year in a nutshell. It all happened fairly quickly and it all seems to make sense to a great many Witches around the world.

The Witches’ New Year

Ask most Witches when their new year begins and the great majority of them will say at Samhain. There are a couple of reasons for this, the most obvious being that late autumn is a great time for new beginnings. The harvest has been taken in and the world (mostly) lies fallow, waiting for its rebirth in the spring. It’s also when many of us begin to turn inward and find ourselves spending more time indoors.

But perhaps the biggest reason so many Witches celebrate the new year at Samhain is because we’ve been taught that it’s the Celtic New Year. This assertion comes up in dozens of Witch books and is a frequent theme at Samhain rituals. However, the idea that Samhain is the Celtic New Year dates back only to the start of the twentieth century. The idea was first put forward by Welsh scholar Sir John Rhys (1840–1915), who interpreted many of the goings-on in early November as being related to the idea of new beginnings. In his book Celtic Folklore: Welsh & Manx, Rhys writes that “this is the day when the tenure of land terminates, and when servantmen (sic) go to their places. In other words, it’s the beginning of a new year.” 14

Rhys’s assertion that Samhain is the Celtic New Year is not one shared by most scholars, but it’s an idea that resonates in Witch circles because it simply makes sense to people. (When was the actual Celtic New Year? No one really knows for sure, so in that sense Samhain is as good a guess as any.) However, not every Witch looks to Samhain as the start of their new year. The Wheel of the Year, after all, is a wheel, and that means that its start and end points are rather arbitrary. Any sabbat (or day) could potentially be the start of a new year or a new turn of the wheel.

After Samhain, Yule and Imbolc might be the two most common “other new year” sabbats. They both make sense as the start of a new year because of their focus on the light of the sun. At Yule, the sun is “reborn” and the days begin to grow longer. By Imbolc, the days have become noticeably longer, making this sabbat a great candidate for fresh beginnings. (Imbolc is my personal preference as the start of the year.)

There are a multitude of reasons to consider Ostara the start of the Witches’ new year. The astrological year begins at the spring equinox, when the sun enters the constellation of Aries, the first sign of the zodiac. For this reason, Persians celebrate their new year on the first day of spring. Ostara is also traditionally associated with rebirth and new growth, perfect trappings for the new year. For similar reasons, some Witches see Beltane as the start of the year. (When I lived in Michigan, this always made much more sense to me than Ostara, when it was often still very cold!)

There are even a small number of Witches who use Midsummer as the start of their new year. If the longest night works as a starting point, then why not the longest day? I have yet to meet any Witches who celebrate the start of the new year at Lammas or Mabon, but who knows? There might be someone out there doing just that.

Just when a Witch celebrates the new year is up to them. There are no specific rules regulating such things. In fact, the idea of a new beginning or a new year can be used multiple times over the course of the Wheel of the Year. In the fall, I often rid myself of thoughts and tendencies that are holding me back, giving me a clean slate for the new year. Winter is a time for new beginnings, as we start fresh like the reborn sun. Spring is a time to plant what it is we wish to bring into our lives and then see those things grow as the world around us comes back to life. All or none of these ideas can be part of your rituals, and whatever day you see as the Witches’ New Year is worth celebrating.

It’s also worth noting that the secular start of the new year, January 1, was invented by a Pagan who worshiped the old gods (just like many of us do!). And there are many Witches who celebrate the start of the year with parties and other goings-on, just like a lot of other people do. I’ve always believed that the more opportunities we have for milestones and parties, the better it is for all of us!

Wheel of the Year Myths

Many Witches like to connect the turn of the wheel to specific myths. In these myths, goddesses and gods reenact certain events yearly, and in many cases they age from youth to senior citizen before dying and being reborn. The most common myth cycles among Witches often overlap with one another and in many instances are combined, depending on the need of a specific ritual. Over the course of one year, a Witch might use varying and conflicting myth cycles in order to express particular ideas at their sabbat celebrations.

In many of these myth cycles, the deities being honored, celebrated, or mourned match the energy of a particular season. For example, the Horned God who dies in the fall is mimicking what’s happening in the natural world. We often associate the rapid growth common in the springtime with youthful energies, so it’s said that the Maiden Goddess presides over that time of year. None of this is meant to imply that only certain deities are around at certain times of the year, but only that we might feel their energies more acutely at certain points of the wheel. The deities we honor and have relationships with are always with us.

Maiden, Mother, and Crone

The most common myth associated with the Wheel of the Year is that of Maiden, Mother, and Crone (MMC). In most MMC stories, the Maiden Goddess emerges near Imbolc and grows in physical maturity as the seasons turn, becoming a Maiden, Mother, and Crone over the course of twelve months. She is then reborn to repeat the cycle. In many versions of this story, she’s paired up with a version of the Horned God who progresses physically in a similar manner. There are a growing number of people who find the MMC model incomplete. Not all women will become mothers, for instance. But this model is still commonly used at many sabbat celebrations.

Often the Maiden/Mother/Crone myth is connected to themes of fertility and sexuality. In most versions of this story, the Maiden Goddess becomes sexually aware at Ostara (this sometimes includes flirtation with the young Horned God) and sexually active at Beltane. The two are sometimes said to get married at Midsummer, with the Goddess displaying a very visible “baby bump.” The Horned God generally sacrifices himself for the good of the harvest near Samhain, only to be reborn at Yule when the Goddess gives birth. Though rarely articulated as such, this would require the Crone to be the one to give birth, giving the tale one last magickal twist.

While the concept of the Goddess as Maiden, Mother, and Crone feels legitimately ancient, the idea is a relatively modern one and was first completely articulated in 1949 by the poet Robert Graves (1895–1985) in his book The White Goddess. Of course, there were Maiden goddesses in ancient paganisms, along with Mother goddesses and Crone goddesses, but in mythology these goddesses weren’t reborn annually. Goddesses generally didn’t age much past prime adulthood either. It’s certainly possible to create a version of the Maiden, Mother, Crone myth by creatively adapting existing mythologies, but that doesn’t make the MMC historical.

I have met many Witches who use the tale of Demeter and Persephone to illustrate the MMC story. In the classic version of the tale most familiar to Western audiences, the goddess Persephone, daughter of Demeter, is kidnapped and forced to marry Hades, the god of the Underworld. Distraught over the loss of her daughter, Demeter neglects her duties as the goddess of agriculture, and all fertility in the world ceases. Eventually the Titan goddess Hecate intervenes and persuades Zeus, the king of the gods, to allow Persephone to leave the Underworld and return to Demeter. Zeus then dispatches Hermes, the messenger of the Greek gods, to retrieve Persephone from Hades. Persephone, overjoyed to be leaving the land of the dead, eats between four and six pomegranate seeds before leaving the world of her husband. Sadly, for every pomegranate seed she ate in the Underworld, Persephone must spend one month in the home of her husband each year.

Thus, the seasons are explained by Persephone’s eating of the pomegranate seeds. Demeter lets the world whither in the fall and winter while Persephone is away, only to bless it in the spring when her daughter returns to her once more. This myth is super adaptable too. If you live in a cold climate, perhaps Persephone ate six seeds instead of four in your version, while those of us on the California coast can build our myth around the idea that she ate only three seeds.

When using this story to illustrate the MMC myth, the problem is that Demeter is not Persephone; they are separate entities. When Hecate is added to the mix, the story becomes even more garbled. Hecate is not a Crone goddess, and again, is not Demeter or Persephone. There’s nothing wrong with creative license, but I’m not sure it’s okay to fundamentally alter the very nature of a goddess.

With the often strong emphasis on fertility and reproduction in MMC myths, there are many who feel left out. It’s common today to see additional layers being added to the MMC model (such as Warrior or Hunter), along with the removal of some aspects. My wife and I have no children and don’t plan on having any. This makes the idea that my wife is a “Mother” rather silly. Women are more than their ability to give birth.

The female-male dynamic in the MMC story also bothers some people. I’m a firm believer that the deities I honor in my circle honor every aspect of human existence, meaning that a Beltane ritual where the Horned God is replaced by a goddess is just fine with me. The most important part of any myth cycle is that it speaks to the people who are using it. If your coven loves the MMC model, by all means use it! And if it leaves people in your group cold, you are free to throw it out.

Despite some people being uncomfortable with the MMC model, it’s still one of the most common seasonal motifs in the sabbat rituals of Modern Witches, and because of its flexibility, adaptability, and popularity, it will probably remain so long into the future. Despite its shortcomings, it’s still a great starting point for ritual, and much of its language is firmly embedded in many covens as well. (It’s hard not to use the term Mother Goddess in ritual, for instance.)

Perhaps the most magickal part of the MMC myth is that the Goddess never dies, nor is she ever reborn on a specific date. She simply reappears in the late winter or early spring and resumes her work in this world. In most versions of the MMC cycle, the God is completely dependent on his wife and mother, while the Great Goddess needs no helping hand.

The Dying and Rising Sacrificial God

Often honored on the Wheel of the Year side by side with the Goddess as Maiden/Mother/Crone is the dying and rising sacrificial god. In this myth, the Horned God sacrifices himself annually for the good of the people and the earth and is then reborn with the sun at the winter solstice. The dying and rising sacrificial god is a mixture of both ancient and modern mythology. Gods certainly sacrificed themselves for the good of others in tales and legends, but the idea of a god dying and being reborn on a yearly basis can only be inferred through ancient myth.

In most myths, gods are either alive or dead; that is, they exist in the realm of the gods and/or earth (alive) or in the Underworld (dead). Periodically souls are allowed to move between the two planes of existence (as was the case with the Greek Adonis), but they do not have to be “reborn” from the womb in order to do so. The idea of the annual rising and dying sacrificial god was made popular thanks to the work of the English anthropologist Sir James George Frazer (1854–1941), who articulated the idea quite explicitly in his multivolume work The Golden Bough.

The sacrificial god myth is most often used from Lammas to Samhain, and I’ve seen the God “die” at both of those sabbats as well as Mabon. Just how the God dies varies from ritual to ritual. Sometimes he’s cut down by adversaries, his death enacted in such a way that it parallels the grain harvest. I’ve been a part of Samhain rituals where it’s the Goddess who kills her love, knowing that he must die for the life-giving energy of the world to be renewed. If the God dies before Samhain, he is sometimes honored in late October as the god of death.

The Holly and Oak Kings

A clever twist on the story of the sacrificial god is that of the Oak and Holly Kings, originally articulated in Robert Graves’s The White Goddess. The Oak and Holly Kings are frequent visitors at many solstice rituals. The story of the Oak and Holly Kings is that of two brothers who continually battle for world supremacy.

The Oak King generally rules during the waxing half of the year, from Yule to Midsummer, growing older as every month passes. On the Summer Solstice, the Holly King comes for his older brother’s throne and defeats his sibling in hand-to-hand combat. The Holly King then takes the throne, while the Oak King goes off to lick his wounds and be reborn beyond time and space. The Holly King then grows older, and the cycle is repeated over and over every six months.

I’ve seen some creative uses of this myth over the years. At one especially powerful Midsummer ritual, two of my friends went toe to toe with real swords in an epic battle. When the Oak King eventually fell, it was a grieving Goddess who appeared at his side and drew out her dagger to finish the deed begun by the Holly King. As she killed the Oak King, she said she was doing so in order to ensure the world’s continued fertility.

Most of us are probably not skilled enough with a sword to reenact this biannual confrontation between two brothers; however, swords are not really required. A Harry Potter–esque battle involving wands is one way around the use of steel. Other ways of “slaying” one of the brothers might include riddles or even a dance-off. The only real limit here is one’s imagination.

My only concern with confrontations between the Oak King and the Holly King at large sabbat celebrations is that they often don’t leave much for the other participants to do. The best types of rituals are those that get everyone involved, and that can sometimes be hard to do with this myth.

The Sun God

Many Witches see the annual waxing and waning of the sun as an expression of their God. In this myth, the God of the Sun is reborn at Yule, reaches the peak of his power at Midsummer, and then begins his decline. In some versions of this tale, he might sacrifice himself at Samhain, or simply die of old age at Yule. This myth is usually used in conjunction with others throughout the course of the year, and is especially prevalent at Yule celebrations.

Aphrodite/Persephone/Adonis

One of my favorite Wheel of the Year myths is based on one involving Aphrodite and Persephone, who find themselves fighting over the soul of Adonis, a beautiful young man whom Aphrodite is in love with. When Adonis is killed in a hunting accident, Aphrodite asks Zeus to release his soul from the Underworld so that he might live with her on Mount Olympus.

When Persephone spots Adonis in her domain, she immediately falls in love with him and refuses to give up his soul so that he might reside with Aphrodite. Eventually a compromise is reached and Zeus decrees that Adonis will spend six months a year with Aphrodite and six months with Persephone. When Adonis is with Aphrodite, she makes the world bloom, and while he’s away, she neglects it and causes it to whither. In a bit of a modern twist, we like to imagine that when Adonis returns to reside with Persephone, the goddess of the Underworld becomes happy once more, thus allowing the dead to be reborn in the world of the living.

Note that it’s the goddesses here who hold all the power and not Adonis. It’s not his power that transforms the world but that of Aphrodite. When my coven uses this myth, we celebrate the return of Adonis to Aphrodite near the spring equinox, with his return to Persephone thus coinciding with the start of autumn. Though not an extremely common Wheel of the Year myth, it’s a fun one and often surprises people.

7. Guiley, The Encyclopedia of Witches & Witchcraft, 283.

8. We don’t have the space in this book to do a full overview of history, but Murray’s writings on Witches positioned Witchcraft as an organized religion in opposition to Christianity. This was new at the time. Many of the ideas contained within her books were later incorporated into the practices of Modern Witches.

9 . Gardner, Witchcraft Today, originally published in 1954 and available in dozens of different editions today. This information is from the very beginning of chapter 12.

10. Gardner, The Meaning of Witchcraft, 18.

11. Ibid.

12. Hutton, The Triumph of the Moon, 248.

13. Aidan Kelly, “About Naming, Ostara, Litha, and Mabon,” Including Paganism (blog), May 2, 2017, https://www.patheos.com/blogs/aidankelly/2017/05/naming-ostara-litha-mabon/.

14. Rhys, Manx Folklore & Superstitions (originally published as Celtic Folklore: Welsh & Manx in 1901), 9.