Surprisingly cozy, ten counter seats and thirteen table seats. When the guests arrive, Jiro carries tane bako ingredient boxes made out of plain wood from the back and puts them down on the room-temperature tsuke dai counter.

The restaurant is located in the basement of a building close to the Tokyo Metro Marunouchi Line Ginza Station.

When you enter through the sliding door, there is a hanging lantern and washbasin made out of Izu stone.

<SPRING> DISH

From bottom row left:

Tori Gai/ cockles (Atsumi)

Shako/mantis shrimp (Koshiba)

Anago/conger eel (Nojima)

Tamagoyaki/Japanese omelette (Okukuji)

Second row:

Aka Gai/surf clam (Yuriage)

Kohada/gizzard shad (Saga)

Kuruma Ebi/prawn (Yokosuka)

Aji/horse mackerel (Futtsu)

Third row:

Chutoro/medium-fatty tuna (Noborito)

Fukko/young sea bass (Joban)

Aori Ika/bigfin reef squid (Kyushu)

Fourth row:

Tekka Maki/ tuna roll (Noborito)

Plate: Hagi Yaki

*The locations of the catch and landing were noted as the areas of origin of the fish. However, if the origins were noted as Hokkaido, Kyushu, etc., at the market, then we conformed to them.

MAGURO TANE BOX (Tsushima)

From bottom row left: Chutoro/medium-fatty tuna, Otoro/fatty tuna (marbled), Otoro/fatty tuna (bellows belly)

Top: Lean Meat

<SPRING> BOX ONE

From the bottom: Katsuo/bonito (Boshu Katsuura), Iwashi/sardine (Nagai), Aji/horse mackerel (Futtsu), Shako/mantis shrimp (Koshiba), Kohada/gizzard shad (Kyushu), Kuruma Ebi/prawn (Tokyo Bay)

<SPRING> BOX TWO

Bottom: Inada/young yellowtail (Misaki) From top left: Aori Ika/bigfin reef squid (Nagasaki), Mako Garei/marbled sole (Joban), Fukko/young Japanese sea bass (Joban)

<SPRING> BOX THREE

From bottom row left: Aka Gai/surf clam (Yuriage), Aka Gai no Himo/string of surf clam (Yuriage)

Second row: Nama Awabi/raw abalone (Iwawada), Tori Gai/cockles (Ise)

Third row: Kobashira/small scallops (Hokkaido), Miru Gai/geoduck clam (Atsumi)

ANAGO BOX

(Nojima, Tokyo Bay)

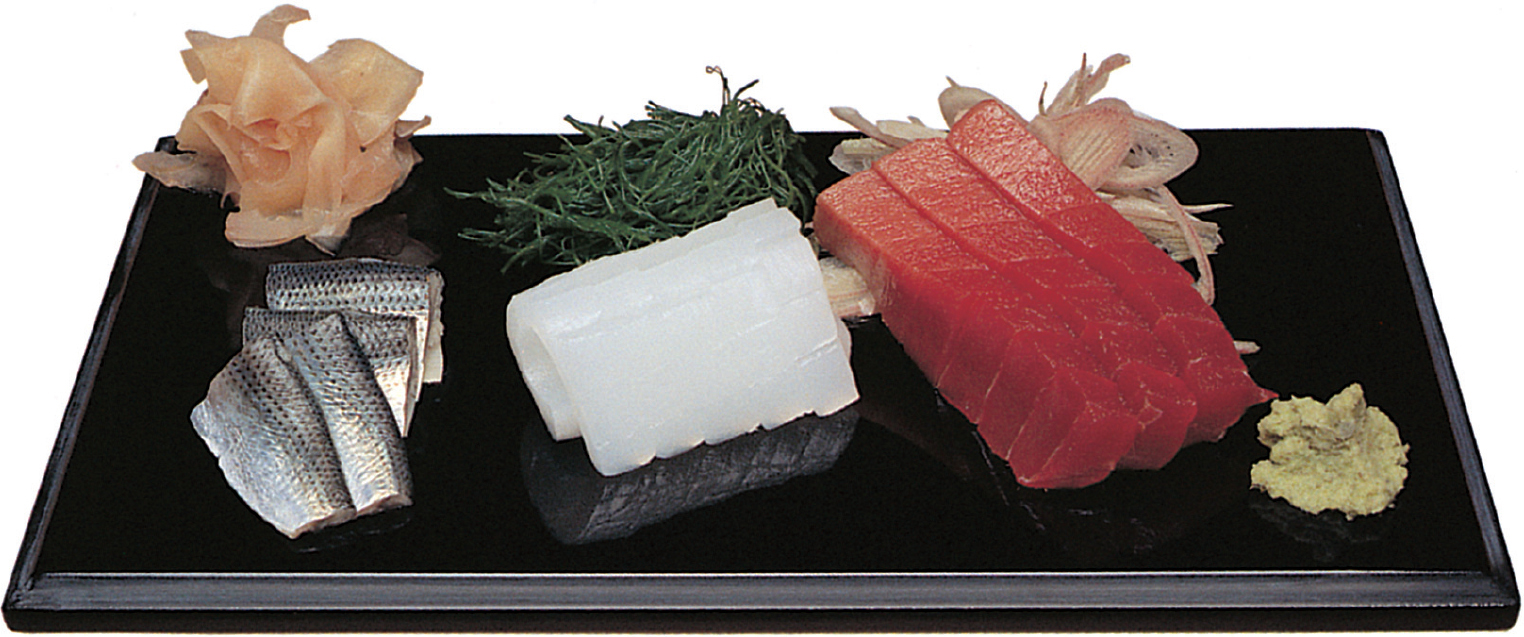

<SPRING> NAMA TSUMAMI: THREE KINDS

From left: Kohada/gizzard shad (Kyushu), Aori Ika/bigfin reef squid (Nagasaki), Chutoro/medium-fatty tuna (Sanriku)

From left: Kohada/gizzard shad (Kyushu), Aka Gai/surf clam (Yuriage), Aori Ika/bigfin reef squid (Nagasaki)

From left: Chutoro/medium-fatty tuna (Sanriku), Mako Garei/marbled sole (Joban)

(sake side dish)

<SPRING> SHUKOU : broad beans When you order sake, seasonal “greens” are served.

<SUMMER> DISH

From bottom row left: Suzuki/Japanese sea bass (Joban), Anago/conger eel (Nojima), Tamagoyaki/Japanese omelette (Okukuji)

Second row: Shima Aji/striped jack (Boshu Katsuyama), Kuruma Ebi/prawn (Tokyo Bay), Nama Awabi/raw abalone (Iwawada), Koika/small squid (Izumi), Mako Garei/marbled sole (Joban)

Third row: Kyuri Maki/cucumber roll, Aka Gai/surf clam (Ise), Shinko/young gizzard shad (Ariake Sea)

Plate: Seiji Kakuzara

<SUMMER> BOX ONE

From bottom left: Koika no Geso/small squid tentacles (Izumi), Kuruma Ebi/prawn (Tokyo Bay)

From top left: Iwashi/sardine (Choshi), Shinko/young gizzard shad, maruzuke (one per nigiri) and nimaizuke (two per nigiri) sizes (Ariake Sea), Aji/horse mackerel (Futtsu, Tokyo Bay)

<SUMMER> BOX TWO

Bottom: Koika/small squid (Izumi) From top left: Suzuki/sea bass (Joban), Mako Garei/marbled sole (Joban), Shima Aji/striped jack (Boshu Katusyama)

<SUMMER> BOX THREE

Bottom: Uni/sea urchin (Hokkaido)

Second row: Nama Awabi/raw abalone (Iwawada), Kobashira/small scallops (Hokkaido)

Third row: Aka Gai/surf clam (Kyushu), Aka Gai no Himo/string of surf clam (Kyushu)

(sake side dish)

<SUMMER> SHUKOU : Edamame

<SUMMER> NAMA TSUMAMI (raw hors d’oeuvre)

From the front: Shinko/young gizzard shad (Ariake Sea), Koika/small squid (Kyushu)

Back: Shima Aji/striped jack (Boshu Katusyama)

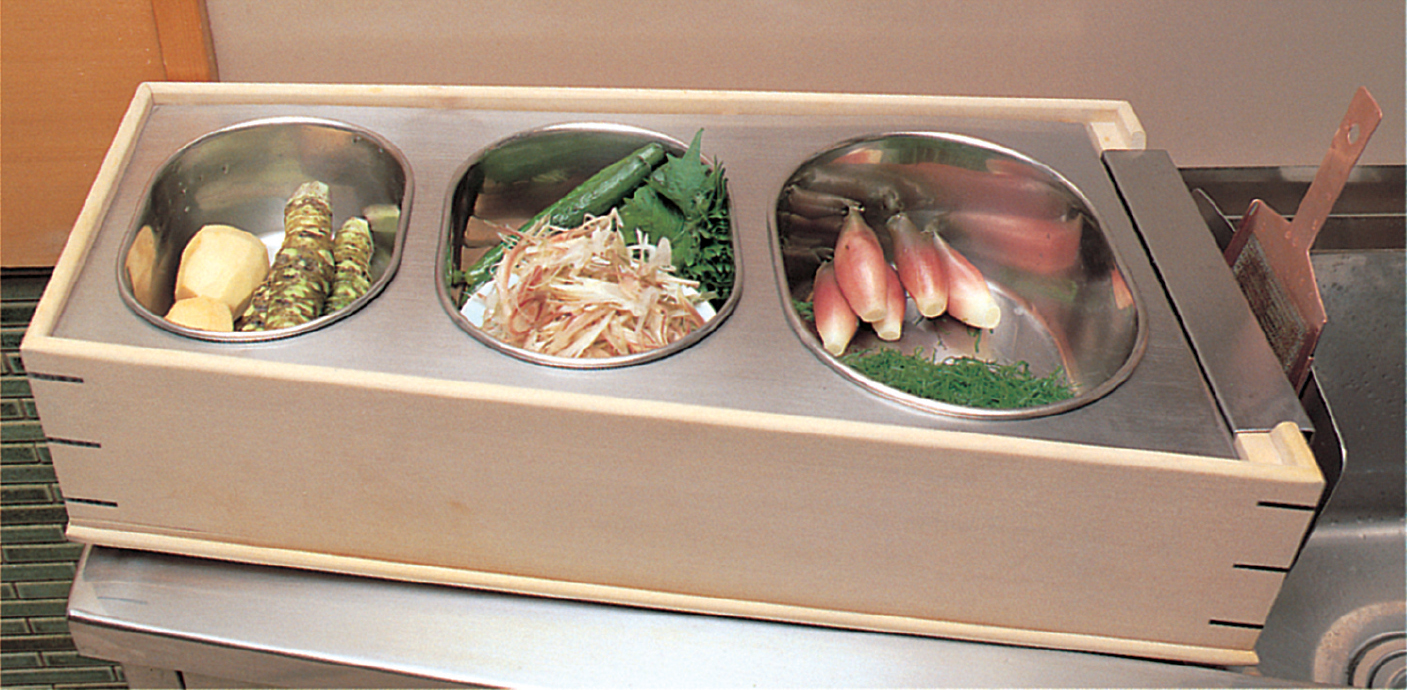

Tane boxes arranged on the counter

Tesu (hand-dipping vinegar), sabi choko (small wasabi bowl), nitsuke (reduction sauce), nikiri (thin and sweet glaze)

Tsuma Ire (containers for sushi accompaniments): shoga (ginger), wasabi, kyuri (cucumber), myoga (Japanese ginger), oba (perilla), etc.

Flowers from the field which decorate the entrance from March to September. One can feel nature’s seasons from the flowers, too.

Gui nomi (sake cups) made by artists line up on the display shelf next to the counter.

<AUTUMN> DISH

From bottom row left:

Anago/conger eel (Nojima)

Hamaguri/hard clam (Ise)

Tamagoyaki/Japanese omelette (Okukuji)

Second row:

Saba/mackerel (Fukuoka)

Kohada/gizzard shad (Atsumi)

Sayori/halfbeak (Futtsu)

Aka Gai/surf clam (Yuriage)

Third row:

Soge/young flounder (Joban)

Otoro/fatty tuna (Oma)

Shokko/young greater amberjack (Boshu)

Back row: Oboro Maki

Plate: Tenryu Yaki

<AUTUMN> BOX ONE

From the bottom: Kuruma Ebi/prawn (Futtsu), Sayori/halfbeak (Futtsu)

From top left: Kohada/gizzard shad (Yamaguchi), Iwashi/sardine (Futtsu), Saba/mackerel (Fukuoka)

<AUTUMN> BOX TWO

From the bottom: Tako/octopus (Sajima), Sumi Ika/squid (Ise), Shokko/young greater amberjack (Boshu), Engawa (little flesh on the fin) of Soge/young flounder (Aomori), Soge/young flounder (Aomori)

<AUTUMN> BOX THREE

From the bottom left: Aka Gai/surf clam (Yuriage), Aka Gai no Himo/string of surf clam (Yuriage)

Second row: Miru Gai/geoduck clam (Atsumi), Hamaguri/hard clam (Ise)

Third row: Kobashira/small scallops (Hokkaido), Nama Ikura/raw salmon roe (Sanriku)

In October, the restaurant is redecorated. The lighting becomes slightly brighter. When you make a reservation, they assign your seat, set chopsticks on the counter, and pull out the chair a little.

(raw hors d’oeuvre)

<AUTUMN> NAMA TSUMAMI

From left: Tako/octopus (Sajima), Saba/mackerel (Fukuoka), Shokko/young greater amberjack (Boshu)

(sake side dish)

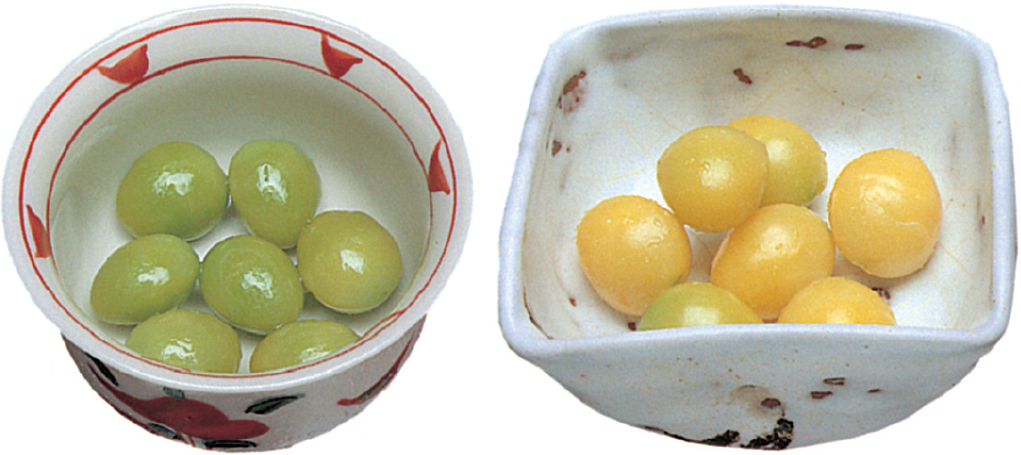

<AUTUMN> SHUKOU

At the beginning of autumn comes ao ginnan (green ginkgo nuts), and eventually you see yellow ginnan.

<WINTER> DISH

From bottom row left: Aka Gai/surf clam (Yuriage), Anago/conger eel (Nojima), Uni/sea urchin (Hokkaido), Tamagoyaki/Japanese omelette (Okukuji)

Second row: Kohada/gizzard shad (Kyushu), Sumi Ika/squid (Nagasaki), Inada/young yellowtail (Tateyama), Saba/mackerel (Choshi)

Third row:

Otoro/fatty tuna (Sado), Akami/tuna lean meat (Sado), Hirame/flounder (Aomori)

Back row:

Kanpyo Maki/dried gourd roll

Plate: Tenryu Yaki

<WINTER> BOX ONE

From the bottom: Kuruma Ebi/prawn (Futtsu), Sayori/halfbeak (Oarai)

From top left: Kohada/gizzard shad, maruzuke (one per nigiri) and katamizuke (one side per nigiri) sizes (Saga), Saba/mackerel (Choshi)

<WINTER> BOX TWO

From left: Hirame/flounder (Aomori), Engawa (little flesh on the fin) of Hirame/flounder (Aomori), Back and belly of Inada/young yellowtail (Tateyama)

<WINTER> BOX THREE

From the bottom: Tako/octopus (Sajima), Nama Ikura/raw salmon roe (Sanriku), Uni/sea urchin (Hokkaido), Hamaguri/hard clam (Ise)

<WINTER> BOX FOUR

From the bottom: Wasabi (three years old, Tenjo), Kobashira/small scallops (Hokkaido), Sumi Ika/squid (Choshi)

From top left: Miru Gai/geoduck clam (Atsumi), Aka Gai/surf clam (Yuriage), Aka Gai no Himo/string of surf clam (Yuriage)

(raw hors d’oeurve)

(sake side dish)

<WINTER> NAMA TSUMAMI AND SHUKOU

From the left: Aka Gai/surf clam (Yuriage), Aka Gai no Himo/string of surf clam (Yuriage), Inada/young yellowtail (Tateyama), Sayori/halfbeak (Oarai)

NIGIRI-DANE IN SPRING AND SUMMER

Seafood in this chapter

Kohada (gizzard shad), Shinko (young gizzard shad), Iwashi (sardine), Aji (horse mackerel), Mako Garei (marbled sole), Fukko (young sea bass), Suzuki (Japanese sea bass), Shima Aji (striped jack), Inada (young yellowtail), Koika (small squid), Aori Ika (bigfin reef squid), Tori Gai (cockles), Awabi (abalone), Anago (conger eel), Shako (mantis shrimp), Katsuo (bonito)

“The tastes of first bonito and returning bonito are as different as fresh greenery and autumn foliage, cherry blossoms and chrysanthemums. So I don’t make nigiri with it in autumn.”

When the plum flowers begin to blossom here and there, the tane box at the sushi restaurant is spring at its height. Not long after the tori gai’s flesh gets thick and soft, long-awaited hatsu gatsuo (the first bonito of the season) come on stage. Shako, aji, mako garei and awabi season is near. And when shinko and koika start to appear, it’s high summer. In these months, how is Sukiyabashi Jiro master Jiro Ono making nigiri with seafood in season?

Kohada (gizzard shad) is the “Yokozuna (sumo wrestling champion) of Nigiri.” My throat squeaks when I eat it. Everyone laughs at me when I say this, but when I chew on kohada nigiri and swallow it, my throat really squeaks. Especially when the kohada on top and the sushi rice at the bottom are perfectly in sync.

And that feeling of “Oh … so good!” really starts to sink in.

Of course I think our other nigiri are delicious too. But I just don’t get the same level of feeling because my throat’s never squeaked while eating other nigiri. Kohada is the cheapest fish among all sushi neta (sushi ingredients, typically fish), but if you prep it well, it turns into the “Yokozuna of Nigiri” that makes my throat squeak.

To prep it well, I examine the nature of the kohada thoroughly, then determine how much salt and vinegar I should use. Especially in the case of shinko (young gizzard shad), every second matters while prepping. There are differences in fat content, thickness, and the fish’s size. If you put them all together and soak them for the same amount of time, I guarantee that we won’t be making throat-squeaking nigiri. Precisely because shinko is so small, we prep to make it all taste exactly the same by catering to the individual fish, each slightly different in size and form, soaking it in vinegar even a couple of seconds shorter or longer.

I repeatedly tell my apprentices how important this is. Up to this point in the process, you can achieve good results with effort alone.

If my apprentices don’t make the fish taste consistent, and if we’re not satisfied ourselves, then I’m in trouble as the one who makes the nigiri. Because beyond that, it’s inside the guest’s mouth, and there’s nothing left that I can do.

Speaking of which, when I was traveling in Kyushu, I tried kohada nigiri at a sushi restaurant. It smelled fishy; the kohada was not pickled well, and it just tasted really bad. My friend and I were whispering, “How did they manage to make this nigiri taste so messed up?” The sushi master mistook our murmurs for compliments and proceeded to proudly explain his prepping process: “I seasoned it with salt for this many minutes and pickled it with vinegar for that many minutes.”

The sushi master must not have tried it himself. Clearly, because he hadn’t fine-tuned the flavor to a satisfactory level through tasting, the kohada nigiri turned into something foul. You don’t have to prep them yourself. You can have your apprentices prep them. But you must taste it yourself after the prep. If it starts to taste strange, then you have to tweak it.

It’s a big mistake to say, “I’m absolutely certain about what I’m doing.”

It’s true with everything. Over the years, a small gap, as tiny as the tip of your nail at the outset, ends up as a gaping one.

It works if you create the taste you like and say, “This is it!” and then, “Here you go!” But you’re making a mistake if you mindlessly keep serving something that tastes strange and say, “I’m not making a mistake. It’s just that our customers have poor taste buds.” I keep telling this to my apprentices over and over.

Something like this happened this morning. It seemed like the shinko wasn’t pickled quite enough. I confirmed it after tasting it. So I told my apprentice, “Sprinkle more salt,” because the balance was off with the sushi rice. And I just wasn’t satisfied after many adjustments. I kept telling them to try “one more time, one more time,” and we ended up running out of it for the lunch service. This sort of thing happens often.

People often tell me, “Why do you keep eating so much shinko that’s so expensive in season?” I think it would be rude to the guest if I weren’t able to say, “This is good!” after tasting it, confident in its quality. We don’t make nigiri for free. We charge our guests.

This is why I taste our neta repeatedly throughout the day.

Especially with kohada, I taste it in the morning, at noon, and in the evening. Then to see how it’ll be pickled the next day, I try it again after I close. If I keep tasting it until I’m satisfied, then our customers will never say, “It tastes bad.”

However, if I’m feeling a little hungry, I prefer to quickly make nigiri with our kohada, which is far more delicious that way. If a guest orders it just to pick on it while drinking sake, I can’t help but mumble, “Kohada is better as nigiri.” Raw seafood like maguro (tuna), ika (squid), aka gai (surf clam), and whitefish don’t taste all that different as nigiri or sashimi. But for our kohada, we prep it to balance well with our sushi rice, so it’s definitely best to have it as nigiri.

It’s not only about the balance with sushi rice; we also account for the flavor of the nikiri shoyu* that we brush onto the kohada right before serving. When I eat our prepped kohada with our sushi rice and nikiri, I can’t but utter, “Wow, this is so good!”

*Every sushi restaurant has its own unique recipe for nikiri shoyu (nikiri for short), adding ingredients such as sake to pure soy sauce. It’s known as the Edomae-style to serve nigiri after putting nikiri on the tane with a brush. Refer to the Sukiyabashi Jiro nikiri recipe.

Back in the day in Tokyo, at sushi restaurants, chefs switched from using kohada to koaji (small horse mackerel) as it got warmer. It was still the same way when I started my apprenticeship at Yoshino at the late age of twenty-six, in 1951, after working at a small restaurant in Hamamatsu after World War II.

I wonder when sushi chefs started to use kohada in the middle of summer.

I think there is a desire on the customers’ side to eat delicious kohada all year round. Moreover, there is an illusion that they can eat tasteful ones in summer; that’s outside of its season. Supply has to follow demand. Therefore, we as sushi chefs have no choice but to search endlessly for ones that are delicious all year round.

In the days when I started my apprenticeship, in the season when koaji started to appear, kohada from the sea near Tokyo grew into the konoshiro size. So they used koaji. Back then, sushi chefs in Tokyo got their kohada from Chiba. The northern limit of the kohada they went for was Chiba; I’d never heard of the ones from Ibaraki.

For shinko, the furthest they were transported was from Atsumi Peninsula in Aichi Prefecture, and not only that, they appeared much later in the market than they do now.

Back then, it would have taken such a long time to ship from Kyushu, and it wouldn’t have lasted even on ice. Even the shinko from Atsumi was transported after they grew bigger, so the beginning of August was the earliest we could make them into nigiri.

Lately, they appear in the middle of July. The first ones are from Maisaka (Shizuoka). Sometimes, there is nigiri with four very small shinko, but back in the day, people must have trashed them at the market since they didn’t know what to do with such tiny ones. By the time these small fish got to the Tsukiji market, their stomach had melted, and they were useless.

But now, it’s the motorization era. After 1970, styrofoam came into wide use, and it does a great job of keeping the contents cool. And if it’s early shinko, then you can sell just one box for a surprisingly high price. That’s why they transport it even if it’s one kilogram. If it were iwashi (sardine), then no matter how much the market price rose, they’d have to sell many boxes to make the same amount of profit.

That’s why shinko’s arrival is rapidly getting earlier.

By the way, first shinko at its most expensive cost 60,000 yen per kilogram, on July 12, 1996. One shinko at that cost-price is roughly 600 yen. And this was a two-slice-topping size, so for two pieces of nigiri, the cost was four times that. Of course, we don’t add any fee for the hassle, which is ten times worse than for one-slice-topping kohada.

So when a guest who’s a stickler about shinko comes to my restaurant, I’m tempted to joke about how much it cost.

“This is a real season-first, so when I calculate the cost, it comes out to 2,400 yen for a pair of nigiri. And that’s just for the neta.”

Of course, I don’t actually say that.

“Oh, then I won’t order.”

That conversation would be a killjoy.

Well, it’s not like we charge that much. This is a true statement. We charge 500 yen for one kan (piece) of shinko or kohada as always. We can’t possibly charge more for a mere kohada nigiri.

“Why do you make them if you’re losing money?” people often ask me, but it concerns my pride as a craftsman, and I ignore whether we’re making or losing money in this case. Because the year’s kohada starts with the shinko today.

“Goddamn it, here we go, this is this year’s shinko!”

I make it with that kind of resolve.

In fact, regarding shinko prices, they were very expensive in 1995 as well. It was in the 60,000-yen range per kilo two years in a row. But the first shinko of the season in 1997 was 35,000 yen per kilo, so there must have been many restaurants that made shinko nigiri. It was still expensive, but I was relieved that I wasn’t being as pigheaded as a result.

I just said that “Kohada is around all year,” but as you know, its season is early autumn to winter. So why is it that delicious kohada comes to market all year around?

That’s a true mystery. Japan is a narrow and long country; there’s such a thing as “it’s in season here,” “not yet in season there,” but the spawning season is very close everywhere. There is no way that kohada spawns in August in Hokkaido and March in Kyushu.

I would understand if the kohada from Mikawa (Aichi), which I consider to be the best in Japan, appears half a month later than the ones from Kyushu in the south. But when the ones from Mikawa come in, the ones from Kyushu haven’t even materialized yet.

Lately, the first ones are from Maisaka, then the next are from Bentenjima, which neighbors to the west, but you can’t continuously catch them. After they appear once or twice, somehow it’s Mikawa or Atsumi. There is no way fish that tiny travel in a stream from somewhere around Lake Hamana to the ocean in Aichi. And a little while later, they appear farther offshore of Mikawa, and by then they’ve grown to their one-slice-topping sizes.

However, in Kyushu right around the same time, it’s still shinko. From an amateur point of view, it should be the opposite. Because the seas around Kyushu are far warmer.

I pondered why it ends up being that way.

The conclusion after thinking it out very hard is as follows.

“Kohada is a semiannual-crop fish.”

If kohada spawn twice a year following this theory, it makes sense. It does make sense, but then shinko should appear twice a year. If not, then the “double crop theory” doesn’t hold up.

When it comes to the logic, to be honest I don’t get it at all. Once the ones from Mikawa appear, the next ones are from Kyushu, but then it’s strange that the ones from the interim don’t come in so much.

On top of that, it’s incomprehensible that there are kohada from Kyushu of a size I can make into one-slice-topping nigiri almost all year round.

“It’s gotten colder, so why are we seeing such cute little ones around now?”

“Fish usually have a set spawning period, but to tell you the truth, this one must have been born late and out of wedlock.”

I’m being silly saying stuff like that, but I don’t see any rhyme or reason at all.

I still have a lot to learn, even now that I’m over seventy.

![]()

I haven’t heard of any sushi restaurant in Tokyo that features nigiri with phenomenal raw iwashi (sardine) as its selling point. The higher class the sushi restaurant, the more strongly they must feel that “We can’t serve such a low-grade fish.”

Another reason they wouldn’t want to serve iwashi is because it’s hard to keep it fresh. And you can’t charge too much for mere iwashi, so the cost doesn’t balance out with the hassle.

Iwashi goes bad really quickly in any case. If we just throw it into the neta case, the red muscle oxidizes and turns black, so first thing in the morning, we finish frantically taking care of the head and the innards, then painstakingly wash it with salt water and soak it in ice. If we don’t work on it that much, we can’t keep it fresh until nighttime.

Also, refrigerators dry the fish and make it lose its freshness. Therefore, we put it in a hyozoko (box with a large block of ice). You remember when Tokyo had the water shortage, and there was a commotion that “We can’t get ahold of ice.” That time, we bought a special fridge that prevents dryness. There is no other fish whose care is so troublesome.

There is yet another tough condition: I can’t serve it to our guests unless it’s the finest quality iwashi, matching that of our kinkai hon maguro, anago, aka gai, and such. The discrepancy would be an issue.

So I chose maiwashi caught by day-trip boats that leave the port in the morning and return in the evening. To sum up, they are medium and large ones landed on Choshi (Boso Peninsula) and Misaki (Miura Peninsula). Especially the large ones have to be fat like Konishiki (a popular sumo wrestler from overseas), otherwise we can’t use it, so without exception our customers who see our neta box say, “This is the first time in my life I’ve seen it so fat.”

However, the one in the neta box is for display. After we receive an order, we take out iwashi that’s been soaked in ice cubes in the hyozoko. It’s only then that we open the fish with our hands and make nigiri.

With plump in-season iwashi, the fatty layer in between the skin and the flesh is amazingly thick. Despite that, it neither smells fishy nor tastes greasy. The contrast between the pure white of the fatty layer and the bright red of the dark meat is remarkably beautiful when I slice the freshest ones. After I make the nigiri and brush nikiri on it, the colors are brought to life even more.

“What’s going to happen to the display fish in the tane box?” our guests often ask us.

We cook it and eat it later.

When it’s simmered, it’s so delicious that I think this particular joy is the reason I continue to be a sushi chef. I can taste the fish especially well when it’s simmered. If I cook one out of season, it tastes only salty, but for in-season iwashi that has put on fat, the deliciousness is brought out so much that I tilt my head and wonder, “Why in the world does it taste so good?” A different flavor is brought out compared to when it’s raw.

Every time I finish eating hot simmered iwashi, I feel from the bottom of my heart: “This is the privilege of a sushi restaurant owner.”

By the way, no other fish’s taste changes so drastically in and out of season. You can find it at the market throughout the year, but I only make nigiri when it is in season. In a typical year, medium-sized ones that taste better start to appear in Tokyo Bay around mid-April. They stay medium-sized for about two and a half months. The fatty layer is still thin around this time; they have a smooth and soft taste. They start to gain a lot of fat right before entering the rainy season and grow into their round and plump large size. They taste the best right after the rainy season.

Of course the large ones have a stronger taste, but if you ask me which one tastes better, I don’t think there is much of a difference. Large as large, medium as medium, they both have plenty of their own flavors and umami.

Iwashi finishes decorating our neta box in November. We don’t use it after the beginning of December. It becomes skinny when it’s in the spawning phase, and only the head is big. If you eat fish like that, small bones keep sticking inside your mouth—not good at all.

![]()

While the currently popular seki aji (’seki horse mackerel from Saganoseki, Oita) has started to come into Tsukiji Market, what I really want to make nigiri with is aji (maaji), which is much smaller and tastes lighter.

Aji from Odawara (Sagami Bay) is the best that I can get ahold of in Tokyo. However, they barely come into Tsukiji lately. Even if they do, it’s only a handful.

They do land. They land a little, but the local Japanese restaurants and dried food stores buy them out. They can sell them for a lot even as dried fish. One slice of a domestic wild one costs 400 yen. But the ones from Sagami Bay cost 800 yen. No wonder it’s “the Phantom Aji.”

The aji from Odawara are known for their slight sweetness, light aroma, and refined fat. Because the fat is spread equally, the flesh is whitish, so you know it’s from Sagami Bay just from slicing it. It’s superb fish.

And yet, it’s not greasy. When you chew on it, the umami fully spreads in the mouth. One time, I made nigiri saying “so good, so good” and had thirteen pieces and still didn’t tire of the taste.

However, sushi restaurant masters can’t make nigiri with “the Phantom.” What I use at the moment is mainly from Futtsu (Boso Peninsula)—the best quality if you don’t count the ones from Odawara. Tokyo Bay and Sagami Bay are very close, so there is not much difference in taste.

Its season is from April to June, and it tastes the best in Tokyo over the summer. Aji starts to appear later in warmer Kyushu, just like kohada.

We don’t pickle it. If you make nigiri with pickled aji and raw aji and ask me which one tastes better, there’s no question I’ll declare raw the winner. That’s what I believe from comparing the tastes.

The reason sushi restaurants in the past pickled it is because it wouldn’t be fresh. They salted it for half an hour with its skin on, pickled it in vinegar for half an hour, and when it came to making nigiri, they always paired it with the oboro (ground and cooked flesh) of whitefish or shrimp. Aji has a soft texture and soaks up vinegar quickly. Having pickled it for half an hour, the sourness stood out too much. That’s why they sandwiched sweet oboro.

Raw aji is a very difficult neta to make nigiri with. Because of the grated ginger juice that accompanies it, the compatibility between neta and shari (vinegared rice) declines, and they start to fight, by slipping, when I try to make nigiri. It would be easy if I drained the excess liquid. Even a greenhorn could do it then. But the gritty fiber texture would remain on the tongue and the flavor would skip town. It’s the nigiri pro who can make it right with juicy ginger in between.

Sukiyabashi Jiro master Jiro Ono never stops putting in the effort to serve the best nigiri.

He works in silence, but he actually likes to talk.

There is no better whitefish than mako garei (marbled sole) from Joban (Fukushima) in the warmer months. I believe in this. Hoshi garei (starry flounder), considered “the King of Whitefish,” is in season too, but the drawback is that its flesh tightens quickly.

For instance, let’s say, in the morning, there are mako and hoshi garei here, and we prep them the same. The mako’s meat is so resilient that in the evening, it’s still live and fresh. However, the hoshi starts to turn white from its tail. The meat starts to die quickly. So I can’t agree that hoshi is worthy of all the buzz.

Suppose we asked a hundred people who like whitefish, “Which one is mako and which one hoshi?” after letting them try both. I don’t think there are many people who can discern the difference and say, “The mako’s flesh has a masculine texture and is on the plain side. In comparison, the hoshi tastes a bit over-rich and is slightly greasy, although of course it’s whitefish, so it’s not too strong.”

There may not be any other sushi craftsman who values mako garei as much as I do. Because hoshi garei is a phantom fish that barely comes into Tsukiji, customers around Ginza probably know that it’s very pricey and exclusive. However, if I, who’ve been running Sukiyabashi Jiro since 1966, am asked which I use in spring and summer, my answer is definitely “Mako garei!”

I valued mako even before anyone was using it. I’ve always thought, “This is good!” When I was entrusted to run Yoshino’s Sukiyabashi branch in the late ’50s, the whitefish in the warmer months were fukko (young sea bass), suzuki (Japanese sea bass), kochi (flathead), and soge (young flounder). Because I’ve been like this, I may be overrating it.

You know, it’s not like I don’t value hoshi garei. I think highly of it, but if it’s a question of which one to use, then …

I guess that’s what evaluating means.

Of course, the mako, whose meat is more than sufficiently robust, also has a weakness. Unlike hirame (flounder), the mako’s engawa (little flesh on the fin) tastes bad. It has a grassy and fishy flavor. And it would be rude to serve that to our guests, so we don’t. We store them in the freezer and only the restaurant staff eats it.

I try to finish using mako on the same day while its meat is still live and fresh. It’s the responsibility of the sushi maker, but especially with whitefish we need to make nigiri while it’s at its prime to eat. And we have to change the thickness of the slice between those that are too fresh and those that taste mature after a little while. With the ones that are too fresh, if you don’t slice them thin, they get chewy, and on the other hand, the mature ones’ umami is only brought out by being sliced slightly thicker. This slight thickness is a matter of one millimeter. But the subtle difference decides the taste of whitefish.

I do make nigiri with fukko (young sea bass) in early spring. If mako is a masculine fish, then fukko, with its soft tissue, is feminine. Fukko that time of year is not cheap at all. But you see, when I make nigiri with fukko and then with mako, everyone says, “The mako tastes better.” Same thing with suzuki (Japanese sea bass), but in that case, they must be responding to the pushy flavor as soon as they put it in their mouth.

Fukko is somewhat pushy not only on the belly but also on the back, where it’s supposed to taste plain. There are not many fish that can live in both seawater and freshwater that taste good. This, of course, applies to raw suzuki too. I completely understand why people of old invented arai (slicing whitefish very thin and soaking it in either cold water or ice). If you eat it with sumiso (miso with vinegar), the pushiness disappears, and you don’t balk at the flavor.

On the contrary, mako garei doesn’t have a shortcoming like that. It has a smooth and natural flavor.

There is a problem with shima aji (striped jack). Well, actually the problem is not with the shima aji but the guests who order it. What I mean to say is that back in the day, they only ate wild-caught fish so they knew its real flavor.

Meanwhile, what today’s guests remember on their tongue is farm-raised fish, so even if I make nigiri with the most delicious wild shima aji, their reaction is: “Too plain, not satisfying.”

The same is true of inada (young yellowtail), so young customers especially say, “It doesn’t taste good. It doesn’t have any flavor. It’s just chewy.” People nowadays are used to eating ikezukuri (raw fish prepared alive) of farmed hamachi. It’s firm to the bite and yet very fatty. This is why when I make nigiri with wild inada, they react with, “What the heck is this?”

It’s not fatty, but it’s chewy, it’s sinewy, and thus hard to eat for them. But that’s not it, at all. The same goes for shima aji (striped jack), but we could almost call it shiromi (whitefish) for its plain and delicious taste though its flesh has color and is categorized as iromono (colored fish).

And so, once in a while, when I see inada I like, I make nigiri with it. It has a clean, plain, and light flavor; you can enjoy the taste in season twice a year, in spring and early winter.

![]()

The koika (small squid—offspring of sumi ika, “ink” squid) that start to appear in August remind sushi chefs that autumn is approaching.

That’s because sumi ika’s growth rate is very fast. In the small squid period, its size is small enough for maruzuke, one squid for one nigiri, and later warizuke, one squid for two pieces of nigiri, but by the time summer is over and autumn deepens, it’ll grow to be as big as the sumi ika you find in the fish section. So if you miss the chance, you won’t be able to eat it until the following year. And this is why many people wait anxiously, saying, “Is it here yet? Is it here yet?”

When I make nigiri with koika’s translucent and thin flesh, you can see the green color of wasabi to whet your appetite. It certainly lacks the sumi ika’s characteristic firmness and rich flavor, but instead it has a fragile texture and sweetness, and it is also beautiful in its nigiri form when I use it as maruzuke.

To take advantage of these characteristics, it’s important to keep it fresh. For that, prep it quickly in the morning and use it up on the same day. If you keep it until the next day, the nice translucent flesh turns pure white, and it becomes chewy.

Regardless, I don’t like the price. It’s not like shinko in 1996, which cost 60,000 yen per kilo for the first catch of the season, but it gets more expensive as the years pass by.

Sumi ika is the best as a sushi topping for its mouthfeel and balance with the vinegared rice. I think so.

Expensive aori ika (bigfin reef squid) is delicious as sashimi. Hence it’s called “the King of Summertime Ika,” but how about when we think of it as a nigiri topping?

At our restaurant, we use live aori that’s been swimming in the ikesu (a fish tank), so the flesh is extra firm. When I make nigiri, it doesn’t curve softly along the shari (vinegared rice). That squid sweetness isn’t brought out until you chew on it for a while in its sashimi form, cut in thin, string-like pieces. The umami finally comes out then. That’s what I think, so unless it’s a specific order, I use sumi ika for shari-hugging nigiri, and aori ika as a sake side.

For geso (tentacles), I only use koika. And in addition, I only make nigiri with very small ones. One piece of tentacle for one piece of nigiri. If it’s bigger than that, it doesn’t taste good when I make nigiri with it. It doesn’t taste good even grilled. I’d decline serving it, saying, “Yes, we do have it, but I wouldn’t recommend it.”

We could make money if we obediently offered our guests what they want. However, I don’t want to recommend something that I know doesn’t taste good, telling them, “How about sumi ika’s geso? It’s a bit firm, but the flavor will start to come out as you chew more.”

This is the reason a lot of geso go into the stomachs of our young staff in autumn. Come to think of it, tons of it were served at lunch yesterday.

I don’t make nigiri with aori ika’s geso. We broil it with soy sauce and serve it as a snack. It’s better to broil it quickly than to make nigiri with it. I think so.

I don’t refuse if a customer insists, “I still want you to make nigiri with it.” But I can’t make nigiri with it as is. It’s too big to be a sushi neta, so I open it and then make nigiri with it. If it’s too big, geso’s flavor is too strong and it overwhelms the shari.

Koika (small squid)

Offspring of sumi ika (squid)

Body length: 7 centimeters

Warizuke size (one squid for two nigiri)

Weight: 50 grams

Sumi Ika (squid)

Body length: 13 centimeters

Ones that are tasty and easy to use weigh about 300 grams

Aori Ika (bigfin reef squid)

Body length: 38 centimeters

Length to the tip of the tentacles: 98 centimeters

Weight: 2.4 kilograms

The place that produced the best-tasting shellfish in Japan back in the day was Tokyo Bay. But the habitat of shellfish is now all reclaimed. The same thing with Kemigawa in Chiba, where since the Edo period we used to catch aka gai (surf clam). Kemigawa used to be synonymous with aka gai.

We used to be able to catch miru gai (geoduck clam), too, as well as hamaguri (hard clam) and baka gai (aoyagi/yellow tongue surf clam). They tasted far better than the ones from any other places. The kobashira (small scallops) were also the best.

Well, Edomae-style kobashira still taste good, even now. But the pieces have gotten smaller. I don’t mind that they’re smaller, but they also have sand, and we can’t seem to get rid of it no matter what. We end up ruining half of it as we try to get rid of the sand, so we switched to using ohoshi (bigger kobashira) from Aomori or Hokkaido.

I can’t seem to forget about the Edomae-style tori gai (cockles). The big ones were as thick as 1.5 centimeters, and they were fluffy like a carpet. Tori gai nowadays at its biggest comes at six pieces per box, but it used to be just three. That’s how magnificent they were. I couldn’t make nigiri with it unless I sliced it into three pieces, but it was so soft. When shellfish gets too big it’s usually very firm, but these weren’t tough at all. They also had plenty of sweetness and aroma.

We have only one guest left who’s tasted it. When the tori gai season comes, this guest, who’s more than a dozen years younger than me, always says, “Tori gai nowadays …” There are only two of us who remember that taste—just the gentleman and myself.

It’s all in the past, but not ancient times. I’m talking from about 1970 to 1975.

What I mainly use now is from the Atsumi Peninsula. Although it’s not as great as the Edomae catches from the old days, I can start to get big, good-quality ones in late April. I can’t make nigiri with it as is, so I slice it into two pieces. It’s that big.

In any case, the staff at shellfish stores are skilled professionals. They lightly boil the tori gai and finish them so they feel a bit raw, soft and sweet. Shellfish from other places are a bit firmer, so I always end up buying the ones from Atsumi.

When handling tori gai, you have to peel it without losing the unique coloring on the surface, and then bring out its inherent sweetness and texture by adjusting how much to boil it. This is how the flavor is set, and why the peeling and boiling method is a trade secret. When the fishmongers get to work, they lock the shack and don’t allow in any strangers.

It must be a somewhat bizarre sight.

The traditional work done by sushi chefs to awabi (abalone) is nikkorogashi. When you roll it around in the pot with boiled-down soy sauce and sake, it turns into shiny, red-and-black simmered shellfish. But if you make it that way, good awabi becomes too hard.

That’s why I slice it thinly and make nigiri. But whether it’s hard or soft, if you brush on the strongly flavored nitsume* that’s the standard accompaniment for simmered neta, two-thirds of the subtle and sensitive aroma will be gone. If you were to make nigiri with nikkorogashi, you wouldn’t have to look desperately for scarce awabi from Boshu or Ohara like me.

* Nitsume typically is a broth that comes from simmering anago (conger eel). Back in the day, they used a combined nitsume made from hamaguri (hard clam), anago (conger eel), awabi (abalone), etc., for the same gamut of nimono-dane (simmered toppings), but today, it’s common to use nitsume made with anago for all of them. Find the Sukiyabashi Jiro recipe here.

However, my steamed awabi couldn’t possibly be made without using the soft female shellfish from Ohara, the so-called biwakkai. Why?

“I feel like I’m tasting a supremely blissful extract of the ocean. Its overwhelming deliciousness and sweet aroma wash away everything bad that I’ve ever tasted in the past.”

A familiar face at my restaurant even put it in such a literary way, because the tender mouthfeel, the moistness when it goes down the throat, and the sweet aroma as if it’s the milk of the sea are by far the best with biwakkai from Ohara.

As a sushi ingredient, awabi must be cooked and not used raw. That’s what I think. Especially with the firm aokkai (male shellfish), it’s nice to eat as mizugai, which is cut in cubes and then soaked in ginger vinegar, but it’s too crunchy for nigiri. So if a customer orders a raw nigiri, then I use biwakkai, which has the soft flesh and the strong aroma of the sea.

If you have it raw, it doesn’t make a big difference whether it’s from Boshu or other places. It’s when you cook it that you feel a huge difference. If you simmer awabi from other places, all of its inherent character and the rich flavor escape, and it becomes hollow. On the other hand, the ohara turns indescribably moist when cooked.

Whenever I slice the ohara, I wipe the knife every time. The blade becomes dull because the ohara’s amazingly rich gelatinous layer sticks to the knife. I think it’s this gelatinous layer that creates the world of difference in taste.

My steamed awabi has a similar taste to the mochi awabi that they make in kappo (high-end traditional cuisine). But I don’t actually steam it, I simmer it in a half-sake, half-water sauce for about three and a half hours, which brings out the flavor. So it’s like sakani (simmering in sake), and what matters is how to bring out the natural flavors of the ingredient.

I want to prioritize preserving the aroma of the milk of the sea over everything else, so I brush not the thick and sweet nitsume, but the light nikiri shoyu on nigiri.

I’m not certain why or when I started to make it that way. I remember experimenting with it, trying to make it a bit fluffier or to bring out more of the aroma. But because I’m the master of a sushi restaurant, not a scientist, I don’t have lab notes as in “when I did this, this happened.”

There are many people who say:

“Your awabi nigiri is immensely mysterious.”

“I’ve never seen a nigiri with a steamed awabi that hugs the rice so perfectly.”

“Normally, they put nori around it so it doesn’t fall apart.”

But I do think it’s the natural way. Shari and neta together become one as nigiri. Am I wrong?

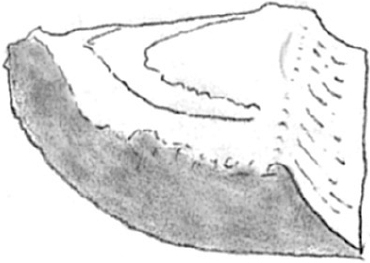

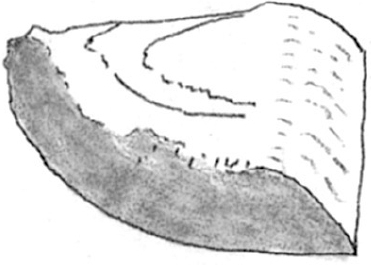

How to cut a steamed awabi

To use it as nigiri-dane, carve a concave edge.

A few minutes after carving it, the surface starts to form a convex curve. You then have to slice according to the convex shape.

To reveal a trick, when I cut at the surface, I use the knife to carve a concave shape so that it’ll curve along the shari. And this is the mysterious part, but the flesh of the steamed awabi with a dent in the center starts to bend powerfully back out, as if it’s alive. The heat was applied to it for three and a half hours to four hours, so there is no way it’s still alive. The ohara is a very mysterious awabi.

Unfortunately, they instituted a fishing ban on the ohara in 1995, effective for five years, until 1999.* It got too popular and became scarce.

I was thinking, “This is a problem,” but then I found out that with biwakkai caught in Iwawada, which is very close to Ohara, I can make sakamushi (a dish cooked in sake) that compares favorably. Maybe because the biwakkai eat kajime (ecklonia cava) like the ohara does, even their shells look very similar. I just don’t believe they aren’t related.

However, only a little comes around to Tsukiji, so even the iwawada has become scarce.

The awabi used to make the sakamushi is best for its flavor and softness at around 800 grams, and up to a one-kilogram weight, we can make delicious ones. If it’s smaller, then it won’t absorb the aromatic flavor of the broth, and if it’s bigger than one kilo, then even if it’s from Ohara or Iwawada it becomes too hard after simmering.

At this point in 1997, a reasonably sized awabi costs around 18,000 to 20,000 yen per kilo. In terms of how many pieces we can get out of it, we can’t quite manage twenty, but after getting rid of the adductor, we end up with enough for about seventeen.

It’s expensive, but there isn’t much we can do about it since the ohara can’t be fished. If I cared too much about the price, then I couldn’t get ahold of it. For now, my priority is to secure the goods.

“If you have the iwawada, please share.”

“How many do you want?”

“All of it.”

*They normally remove bans after confirming the restoration of natural resources, but the fishing ban was extended after an investigation in 1999.

To make the sakamushi, I have to simmer at least three or four pieces of awabi to get the flavor, but lately, one or two pieces is all I can get ahold of. Back in the day, if I said, “I want ten pieces,” it was easy to obtain them, but now that’s a bygone dream.

![]()

Throughout the year, we use live anago from Nojima (Tokyo Bay, Kanagawa). The nojima is in a league of its own among Edomae; it’s our huge attraction. It doesn’t change much in taste throughout the four seasons, but from June to July it gets extra fatty and delicious.

After boiling it, we lay it on a tray on the counter and make nigiri at room temperature, then use it up on the same day. If we stored it in the fridge, the soft nojima turns hard.

No, we never broil it. If we broiled it, then the grilled aroma overwhelms its inherent delicate flavor. Plus, we don’t finish our anago as something to be broiled.

It’s really soft, so if we skewer it, the flesh falls apart. And if we were to broil it, we’d have to put it on a grill. We might be able to grill one side, but then it’d stick. If we peeled it off, then it would crumble. So this kind of argument occurs more than once a year: “Can you please broil it?” “I’m sorry, but we can’t broil it.” “Oh, don’t say that, please broil it.” “We can’t broil it.” “Then I don’t want it.” “Agreed, you’re better off not ordering it.” However, very occasionally I might suggest, “Would you like me to broil it?” That’s when anago from another location jumped into the fish tank for the nojima at the market.

In early autumn, in the wee hours of the morning, he rides his bike from Ginza to Tsukiji. The first job of the day is to purchase ingredients; inevitably, he grows focused and tense.

Let’s say there’s a fish tank for the nojima, and a fish tank for anago from another domestic location, and both anago are swimming. If an energetic domestic one jumped into the fish tank for the nojima, even a pro who has dedicated his life to anago won’t be able to tell the difference. Because there won’t be any writing on its body saying, “I’m not a nojima.”

Stare at it at the broker’s fish tank—I don’t know yet.

Touch a round, fat, and lively one.

I still don’t know.

Choose.

I still don’t know.

Drain blood from it.

I still don’t know.

Open it after returning to the restaurant.

I still don’t know.

The moment I know clearly is right after I boil it. The flesh is hard. Because there isn’t much fat on it, it gets hard after being boiled for the same amount of time as the nojima.

The nojima is really soft, so if you don’t gently lift it up with both hands, it falls apart. If the anago isn’t from Nojima, then you can dangle it holding its tail, and it’ll be fine. They’re that firm sometimes. On days when such anago come my way and I know it won’t stick to the grill and I can broil it just fine, the conversation goes smoothly: “Please broil it.” “Yes, yes.”

However, even on days when we don’t have anago we can broil, there is this particular longtime customer who shows up and adamantly insists, “I absolutely want you to broil it!” Not only has he been our patron since the opening of our restaurant, but he’s older than me. Guests like him are like gods. And I can’t disobey the oracle, so although it’s extremely rare, it’s not that I never broil the nojima.

But to be honest, I broil one from the day before that’s been stored in our fridge for making side dishes. It’s already tightened and firm, so even when I put it on strong flames, it doesn’t fall apart.

I don’t make nigiri with broiled anago. I slice it into thin strips, put it in a small bowl, and sprinkle a little bit of wasabi shoyu and toasted nori and serve it as a sake side.

“The grilled aroma goes very well with sake,” the god, who imbibes a glass before having nigiri, squints his eyes with delight.

We have another older customer who is extremely fond of broiled anago, and he gets cranky if we don’t broil it no matter what. If we don’t have anago we can broil on the day of his reservation, then when we prep and boil anago, we take some out to broil before it’s ready.

We normally boil our anago for about twenty-five minutes, but we take it out after fifteen minutes. That way, we can broil it without it sticking to the grill.

We already know that they’re going to order it, and they’re longtime regulars who’re also older than me, so I give them special treatment. If I don’t obey, I’ll face divine punishment.

So the days I broil anago are the days I happen to grab anago that’s not the nojima and those days when the scary gods visit. In short, it’s an exception among exceptions.

![]()

Our shako (mantis shrimp) is extra large, plus it contains roe.

I select shako with roe because I like the soft and flaky texture myself. So I assume our guests aren’t satisfied either if it isn’t soft and flaky.

At the market, they sell male and female shako mixed in a small box. How, then, do we serve only female ones with roe?

The secret is I only pick the ones with roe. You can tell at a glance if they have roe or not, so I sort them: “the ones with roe in this box, and the ones without in that box.” I’ve had a very long relationship with the shako fishmonger, so he lets me be.

It hasn’t led him to say, “Jiro is overbearing.” Because there must be more than a few sushi masters who think the opposite—“male shako that curves along shari is better for nigiri”—and also, whether it has roe or not, there are customers who just like shako as is. In fact, even at our restaurant, there are occasional guests who say, “It’s nice as a sake side, but the roe’s out of place on a nigiri.”

So what I do when I take such an order is to touch the shako and pick one with little roe, or if it happens to be a day when I only have plump ones, I pretend that I didn’t hear them. After many years as a sushi restaurant pops, you come by a certain level of guile.

Oh, by the way, a customer said something like this a while ago: “You specialize in making nigiri with shako with the roe, but there must be many male shako in the box too. Do you eat the leftover male shako for lunch?”

No, of course not.

One box contains seven to ten extra-large shako, and out of it, three at the most are female, and sometimes just one. So on average, two per box. If I bought ten boxes containing ten each for instance, only twenty would be with roe. We’d have to eat eighty males for lunch on a daily basis.

I wouldn’t like that.

Shako should be marinated. There is shako that’s more roe than meat, so it’s more delicious to have it marinated than as is after the shako fishmonger boils it.

Umami first comes out of the crumbly roe after it’s seasoned. So to bring out the Edomae soft and flaky texture, we marinate it in a subtly flavored combination of shoyu (soy sauce), mirin (sweet rice wine), and sugar. We call this process tsukekomi. But because the finished color is light, a lot of people think that it’s just boiled.

Shako that’s been marinated has to be drained. If it’s too watery, then the foundation shari (vinegared rice) gets slippery and the neta won’t align with it. The shako nigiri requires technical skill.

Koshiba (Tokyo Bay, Kanagawa) is the only place I get it from. Of course the ones from other places come to market, but they lack the umami the Edomae shako has. There is shako in this world that doesn’t even taste good at all. The horrible ones neither feel crumbly in the mouth nor have the aroma of shako, which makes me want to complain, “Hey, you must be related to tofu!” There is sloppy shako that’s like some king of snails. We have to select carefully based on where it’s from and its quality.

![]()

The only katsuo (bonito) nigiri I make is with hatsu gatsuo (the first bonito of the season) in spring, and I don’t use modori gatsuo (returning bonito) in autumn, because modori gatsuo is too greasy. But when it starts to appear in the spring, the fatty layer is thin, and it has its characteristic light aroma that’s very appealing.

Of course, without its fat, katsuo is rubbish. However, katsuo that doesn’t have the delicate and refreshing aroma doesn’t taste good, either. Modori gatsuo has a unique aroma to it, too, but it lacks the refreshing quality of the ones from early spring. That’s the definitive difference, and it’s like fresh greenery and autumn foliage, or cherry blossoms and chrysanthemums.

The hatsu gatsuo fished off the Boso Peninsula in mid-April has a slight, cherry-blossom-like “this is spring!” aroma. Modori gatsuo is too fragrant, like chrysanthemum.

Well, it’s not that I’m saying, “Modori tastes bad.” I think it does taste delicious with its fatty layer. I do think so, but katsuo’s charms aren’t limited to its fat. Plus, there isn’t any sense of novelty, just like edamame beans in September. There, it falls short of katsuo caught in early spring. And that’s why I don’t use modori gatsuo.

Also, when autumn arrives, the lean meat of choice is maguro (tuna).

Katsuo from early spring not only has a clean taste and the aroma of very brightly colored lean meat, but also a light fatty layer in between its skin and flesh as an asset. So I smoke the surface quickly, using brand-new straw, to soften its skin.

With a powerful gas stove, it gets cooked through, and the nice fat melts. The flame from straw, on the other hand, has a gentle heat, so only the skin gets cooked. The smoke also gets rid of the slightly fishy smell. But we have to use brand-new straw, because with older straw, the mildew smell will transfer.

The challenge with hatsu gatsuo is that we can’t tell the quality until it’s opened. It’s not like the modori gatsuo with consistent fat layers. Often, I get a good quality one today, and then tomorrow, I come across one where the fat is gone and it’s just hard.

I decided only to buy one per day, so when I open it, and it’s not up to par, we won’t have any to make nigiri with that day. We eat it in the kitchen instead.

We buy one the next day and open it, and it’s bad.

Nope. Have it in the kitchen.

We open one the day after that, and it’s bad.

Nope. Have it in the kitchen.

We open one the day after again, and it’s bad.

Nope. Have it in the kitchen.

However, we’ve been on a streak the past two years, and our batting average exceeded, hear this, .900. While the year before that it was .100 or .200 and we could only use three katsuo over the season, it decorated our neta box almost every day for the month and a half when hatsu gatsuo lands on Katsuura in Chiba or Choshi, from early April to mid-May.

The shinko (young gizzard shad) from Mikawa was good, the mako (marbled sole) from Joban was good, the tori gai (cockles) from Atsumi was good, the iwashi (sardine) from Choshi and Misaki was good—it was a really great spring for the master of a sushi restaurant.

Sukiyabashi Jiro Nigiri-dane Calendar

*The arrows in the chart show when the tane is acquired in season. The quality of nigiri-dane (topping) depends greatly on natural conditions each year. When a season arrives but the neta (ingredient) quality is bad, then no purchases are made, and there are times when a neta’s season arrives earlier or later than usual. Please think of this chart as an approximate guide.

NIGIRI-DANE IN AUTUMN AND WINTER

Seafood in this chapter

Saba (mackerel), Sayori (halfbeak), Sumi Ika (squid), Kuruma Ebi (prawn), Miru Gai (geoduck clam), Aka Gai (surf clam), Madako (common octopus), Hamaguri (hard clam), Hirame (flounder), Soge (young flounder), Aoyagi (yellow tongue surf clam), Hotate Gai (scallop), Taira Gai (razor clam), Buri (yellowtail), Tai (sea bream)

“Since the old days, at sushi restaurants in Tokyo, whitefish in the colder months has meant flounder. I don’t make nigiri with sea bream.”

Kuruma ebi, tako, saba, hamaguri—the originality of a sushi restaurant is demonstrated first and foremost by its boiled and pickled tane, which are worked on with care. Excessive consumption of salt has gained attention as an issue lately, and sodium use has to be kept to a minimum. At the same time, the taste buds of regulars, who are mainly seniors with a discerning palate, need to be satisfied. A sushi restaurant master doesn’t have it easy. Autumn, and then winter. The seasons are blissfully captured with a mouthful of seafood with plenty of fat on it.

Saba (mackerel) from Wakasa is a superior-quality item, on a different level from any other saba. However, it’s considered to be a low-grade fish in Tokyo. Because everyone thinks this, only a few sushi restaurants pitch their saba. Even if they have it, it’s like, “If you want, I’ll make nigiri with it.”

Fatty shime saba (pickled mackerel) is really delicious. I truly believe in this, so kan saba is one of our specialties. The neta is so popular that there’s even a regular customer who finishes one side of the fish by himself like it’s nothing.

At sushi restaurants in Tokyo, chefs normally leave the inside semi-raw, but I pickle it all the way through, much like kizushi (pickled sushi) from Kansai.

Of course, if I asked our guests how pickled they prefer it to be, I’m sure I’d get many different answers.

“I like it when the skin also feels raw.”

“I prefer only the inside to be raw.”

“I like it almost too pickled.”

As a rule, I make nigiri with saba that I pickled the night before. With silver-skinned fish, if you don’t let it rest for a certain amount of time after pickling, the inherent flavor won’t come out. That’s the cardinal rule for setting the flavor.

However, even though it’s pickled, it’s only good to eat for so long. The second day after it’s pickled is good, and then it feels like it may be pickled a bit too much on the third day, and on the fourth day, it’s not good anymore. The fat starts to oxidize, so we have it in our kitchen.

We actually had some for lunch yesterday. When we grill fish that’s been pickled for too long and is sour, it has a different taste, and it’s really delicious. I learned this yaki shime saba (grilled pickled mackerel) from someone from Tosa (Kochi Prefecture).

I only make nigiri with saba in the cold months, from November to February. In March, they start to have offspring, and their flavor declines. So they only decorate the neta box for at most four months. It’s one of the neta that we have to stick to using in its season.

With saba, you don’t need to bother where it’s from all that much. In western Japan, you’d want it to be from Wakasa, but saba doesn’t have much difference in quality in the first place. They swim in schools, and when you catch them in a net, if one is round and fat, then the whole batch is fat. You can catch good-quality saba in one swoop.

The best ones that come into Tsukiji are from off Choshi or the Miura Peninsula. In the past, good-quality saba came from the Sea of Japan, but we barely see them now. Their catches have dwindled, and supplying the Kansai region is probably the best they can do.

It’s easy to evaluate its quality. Unlike katsuo that you have to open to assess, with saba, as long as it’s stocky, round, and fat, it has a sufficient fatty layer. So we may eat the leftovers in our kitchen because we didn’t sell them, but never because we chose wrong.

At a glance without opening it, I already know that a slim one’s flesh is dry. If they only have saba like that, then we’d say, “We’re not serving any today.”

Although saba is one of our attractions, we only use one or two a day. I can’t buy a whole box like fishmongers do, so I carefully choose the fattest fish out of the box. As long as I’m picking out just one, they won’t say, “Jiro is a tyrant.”

Say a whole box of premium-quality saba costs 20,000 yen for six to seven fish. If I paid 7,000 or 8,000 yen for two fish I like, then the cost of the box goes down.

The same thing can be said for iwashi (sardine) in the summertime. I only use up to ten iwashi per day, so I have to pick one by one. And even though it’s only iwashi, a round fat one can cost 800 yen. Buying and serving loose fish is more expensive. If I buy ten iwashi for 8,000 yen, then the numbers end up uneven, but the price per box improves for them. That’s why I’m not causing any troubles to fishmongers even when I pick the fish out one by one.

And that’s why they say, “Jiro isn’t being a tyrant.”

I don’t use seki saba (mackerel from Saganoseki, Oita), which isn’t suited for pickling.

![]()

Noshi Sayori

Layer the dyed ground flesh on the open sayori and roll it together. Skewer it and grill. When it’s sliced after grilling, the cross-section resembles the letters “no-shi” (the word for a traditional Japanese ceremonial decoration).

There are two seasons for sayori (halfbeak), spring and autumn. But there is a difference in fish size between the seasons, and the larger ones start to appear early in the year right before spawning. We call them kannuki, but there isn’t much difference in taste.

Sayori is beautiful to look at. Some people may say its season is winter because, in some regions, it’s indispensable as an item to bring good fortune for the New Year. That’s the case for my hometown (Tenryu, Shizuoka Prefecture). We open the fish, debone it, roll it with ground flesh dyed red and blue, grill it in the shape of noshi (a traditional Japanese ceremonial decoration), and pack it in a jubako (a set of stacked boxes). For suimono (clear soup), we tie a thin strip of sayori and put it in.

Sayori has a blue back, so in the sushi restaurant categorization it’s considered to be a silver-skinned fish, and in the past they prepared it with vinegar. However, the level of freshness now is different from the past. There is no need to kill its inherent plain yet rich flavor with vinegar, so I sprinkle salt on it, rinse it with water, and then peel its skin right before making nigiri with it, raw. When it’s raw, the tough skin stays in your mouth, so I peel it to make it easier to eat.

However, there are surely sushi masters who think that taking advantage of its beautiful silver skin is a must. On the day you buy the fish, you peel the skin and use it raw, and if there are leftovers, you put it through vinegar and make nigiri with the skin on. When sayori is rested overnight, the skin becomes softer, you see. That’s one way. But I only use it raw, the day it’s still live and fresh.

Sometimes a guest orders, “Sandwich some oboro (ground and cooked fish).” But our sweet oboro, made out of shiba ebi (shiba shrimp), needs to be paired with a well-vinegared silver-skinned fish, so it won’t go well with raw sayori. What goes well with it, of course, is wasabi.

![]()

Koika (small squid) that’s born in the height of summer grows bigger as it rains more. When it first appears, it’s too frail to be used whole on nigiri, but as it grows to be the neta size for two to three pieces of nigiri, its sweetness and texture grow to match the typical characteristics of sumi ika (the “ink” squid).

As I mentioned, as a sushi neta, sumi ika surpasses summertime aori ika (bigfin reef squid). I do think so. It has a great texture because its fiber is so soft. If you chew on it a little, the neta and shari (vinegared rice) melt into each other for a refined flavor. When I place it onto our small black lacquered tray, the slightly blueish white nigiri glows. Wasabi showing through the translucent flesh is also appetite-stimulating. The sumi ika comes from Mikawa or Kyushu, and I choose ones that are as small as possible. A whole squid for six to eight pieces of nigiri would be the biggest. I don’t use ones that are bigger than that.

I start using koika in mid-August, they grow to be sumi ika, and I stop using them after April. Until koika are born again, the aori ika (bigfin reef squid) takes center stage.

We don’t use yari ika (spear squid), aka ika (neon flying squid), or surume ika (Japanese flying squid). Their flesh is too firm to make nigiri with them raw. We don’t have niika (simmered squid) either. Nor do we do inrozume, which is stuffing rice mixed with kanpyo (dried gourd) and gari (pickled ginger) into a simmered yari ika (spear squid). It’s probably because these items aren’t traditionally Edomae-style. The master of Kyobashi did not teach me these things.

![]()

A lot of great-quality sushi neta is caught in Tokyo Bay on the Kanagawa side: shako (mantis shrimp) from Koshiba, anago (conger eel) from Nojima, and the best kuruma ebi (prawn) from off Yokosuka. Futtsu on the opposite shore is not bad, but unfortunately their catches vary in quality and fall short in quantity.

The reason Edomae-style ebi (shrimp) is by far the best is that it’s superior in criteria such as sweetness, aroma, and the color after boiling.

This is probably because there’s plenty of food for them.

The seawater needs to be somewhat dirty for the kuruma ebi’s food to grow. “If the water is clean, ebi won’t live there,” so Tokyo Bay became its perfect habitat.

Although the seafood is back, it’s true that Tokyo Bay still smells like oil. We can’t use fukko (young sea bass) or suzuki (Japanese sea bass) that swim at the surface. As for bora (striped mullet), there is no way we could use it at all. However, kuruma ebi, which lives on the bottom of the ocean, doesn’t smell like oil.

They are in season twice a year: in spring, when they become active after the seawater gets warmer, and from autumn to winter, when they start to absorb a lot of food to hibernate. I think the ones from spring are especially delicious.

When I peel the shell, if the fat from its miso (tomalley) gets on the cutting board, it’s extremely difficult to wash off. The fat becomes that rich.

Some sushi chefs say, “Its season is summer.” When the weather gets colder, ebi bury themselves in the sandy mud and hibernate, so these chefs say the season is summer based on the greater yield. For some reason, the Edomae ebi stopped hibernating, so they appear even in winter—I can make Edomae-style all year round.

The fishing method has also improved. In the past the fishermen used a tool that resembled a rake and caught ebi as if they were shoveling snow off a street. Sometimes we chefs couldn’t use the ebi because their backs were scratched all over. But more recently, the fishermen stun the ebi, using electrodes to deliver a current in their habitat. They catch them in one swoop when ebi that were buried in the sand are startled and jump up.

So maybe it’s not that the Edomae kuruma ebi doesn’t hibernate, but instead it’s forced out of its relaxing slumber by the electric shock.

After all, we’re talking about a natural resource. We can’t avoid days when we can’t catch any, and then my go-to is from Lake Hamana. Until kuruma ebi returned to Tokyo Bay around 1985, I used the ones from Lake Hamana, which I believed to be the best in Japan. Compared to others, the wild ebi from Lake Hamana is still far better.

On a stormy day when there isn’t even any catch from Lake Hamana, I use ones from Kyushu, for instance Shibushi Bay. But they just don’t have as vivid a color as the ones from Tokyo Bay after boiling. When farmed ebi is boiled, the color comes out closer to yellow than red, and the wild ebi from Kyushu look similar to the farmed ones. And naturally, their sweetness and aroma are also faint.

Typically, at sushi restaurants in Tokyo, they make nigiri with maki ebi (small kuruma ebi) and use it whole, one per nigiri. But if I could say something, you can’t taste the real deliciousness with maki, so I make nigiri with oguruma (large kuruma ebi). Or else, you can’t enjoy the unique aroma and succulent sweetness and richness. It’s so big that even a man can’t put the whole piece in his mouth at once, so I slice one nigiri into two pieces before serving.

First and foremost, there is a difference in impact between serving maki and kuruma. I want to emphasize that it is the “bona fide authentic item.” That is my thinking.

Kuruma ebi has become our big main attraction, but the reason I insist on using the wild variety, especially Edomae catches, is that I wanted to overturn the theory that “Ebi served in sushi restaurants don’t taste good.”

We can’t do without ebi for saramori (plate of sushi) or demae-zushi (delivery sushi). However, everyone believes, “The taste doesn’t matter as long as it’s red, since they just need the red and white pattern of ebi to make moriawase (a plate of assorted sushi) look colorful.” I didn’t like this.

Of course, it has to do with the budget, too, but for some chefs, as long as it looks like ebi, it doesn’t matter even if it’s frozen. It doesn’t matter even if it’s finished (dead). It doesn’t matter even if the tail is pitch black. Even if they use fresh maki from a tank, it doesn’t matter if it’s cold from being boiled once in the morning and nigiri is made with it late at night. Because of these practices, ebi became synonymous with dreck.

In truth, ebi is a supreme nigiri neta that deserves the best spot in saramori, because it’s something that’s naturally delicious. It’s a great feast when you fry fresh saimaki (young kuruma ebi) into tempura.

This is why I thought long and hard about how I could bring out its inherent flavor to the maximum as a nigiri neta.

“Kuruma ebi becomes a delicious neta after being cooked.”

This is what was taught to me during my apprenticeship. But we also feast with our eyes with Edomae-style nigiri. So I wanted to perfect this beautiful neta with an even more vivid contrast of its red and white pattern.

I’ve tried many things, including different sources and altering the amount of time I boil it, and decided that Edomae is the best for boiling. Of course, even if it’s Edomae, dead won’t do. If it’s not fresh and full of life, the natural ebi colorings won’t come out.

The challenge is how to bring out its inherent flavor. I used to make nigiri twice a day with the ones that I boiled: at noon and at night. I thought that was the most delicious.

But five or six years ago, I was shocked when I happened to eat body-temperature ebi. It had a pronounced aroma and the rich sweetness. I couldn’t believe that it was the same old ebi.

After that, I started to boil it after taking an order. It’s done after five or so minutes of boiling, so all the guest has to do is to wait a little. This way, they can eat an extraordinarily delicious kuruma ebi nigiri.

When boiling, cook it through to its core and bring out all of the umami. And after boiling, blanch it to keep the coloring. But you mustn’t chill it to its core. By the time the surface chills, the core is at body temperature.

This is the trick to bringing out the inherent flavor of Edomae kuruma ebi to the fullest.

After prepping it in the back, I bring it to the counter. It’s boiled to a magnificently beautiful ebi coloring. These are the authentic natural colors created by nature. After peeling the shell and opening it, I make nigiri with it, and its flavor at body temperature, neither warm nor cool to the touch, is unparalleled. Its tomalley is especially delicious.

The boiled ebi in our neta box is for display. I don’t make nigiri with it. We don’t even eat it in our kitchen. We freeze it and mix it into our shiba ebi (shiba shrimp) oboro. With the natural coloring of Edomae catches, oboro’s color palette becomes even more vivid.

I don’t make nigiri with odori (raw). Not even when one of our regulars orders it. Of course, if someone says, “I really want it no matter what,” then we won’t refuse to make nigiri with it. We keep all of our kuruma ebi alive and fresh. But for Edomae, it’s more delicious to eat it boiled than raw. Naturally, food preferences are diverse. And since my business is about serving customers, I should make nigiri without giving lip. I do think so, but I also know that boiled ebi tastes far better, so I can’t help but talk back and say, “Please have it boiled, not raw.”

Saru Ebi (hardback shrimp)

It was used for oboro until 1955. Not caught at all these days. The flesh was tougher than shiba ebi, but the coloring was vivid.

Shiba Ebi (shiba shrimp)

Used for oboro and tamagoyaki (Japanese omelette). Its distinctive feature is that the flesh doesn’t get too hard after cooking.

Maki Ebi (prawn)

A type of kuruma ebi (prawn) that’s typically said to be the best suited as nigiri-dane. Around 14 cm long.

Kuruma Ebi (prawn)

Used for chirashi (variety of toppings, mainly seafood, on a bed of rice) at Jiro. Around 17 cm long.

Oguruma Ebi (prawn)

Around 22 cm long. Weighs 50 grams. Used for nigiri at Jiro. The biggest ebi to be eaten as boiled shrimp.

If it’s awabi (abalone) that’s exceptional in the summertime, then for the current season the Ryo Yokozuna (the two top sumo wrestling champions) of nigiri neta are miru gai and aka gai. They split the popularity at the counter as well. When you broil them quickly and make tsukeyaki (a marinating and grilling technique), they’re peerless sake sides.

But if I may say so, miru gai looks faded in color, so when I make nigiri with it, it doesn’t look good. The fresher it is, the more the meat bends backwards and the worse the nigiri shape.

There is also an issue with its unique aroma, and some guests avoid it saying, “The smell of the sea and the twang are too strong and don’t go well with shari.” But on the other hand, there are guests who like it so much that they order many pieces. It’s a nigiri neta that you either love or hate.

And also, there is no other shellfish that produces so much waste. First of all, its himo (string) doesn’t taste good. If I made tsukeyaki with shoyu (soy sauce), then it’s somewhat edible, but at our restaurant, we trash it along with the hashira (“pillar” or adductor muscle) and don’t use it. We don’t even have it in our kitchen. I have never seen our young guys eat it either.

Plus, it’s gotten surprisingly expensive. I use ones from either the Atsumi Peninsula, Okayama, or Kyushu, but eight nigiri-worthy miru gai weighing 800 grams cost over 10,000 yen at times. Since an incident when a diver was attacked by a shark, they’ve had low stock, but that can’t be the only reason it’s priced that high. I believe someone is manipulating the price.

If stormy days continue for three to four days and no aka gai come into Tsukiji, even the miru gai that they keep in fish tanks somewhere disappear completely. As soon as it starts to come in intermittently, the price hikes up to 10,000 yen.

It’s expensive enough on a regular day. Even when I think, “It’s reasonable today,” it costs about 7,000 to 8,000 yen and doesn’t get cheaper than that. In any case, it’s turned into a nigiri neta that’s expensive and rare. But it’s a popular neta. I can’t not have it at our restaurant.

![]()

My overall evaluation is that aka gai is superior to miru gai as a nigiri neta by a whole notch or two. Its nigiri shape is better. Its shiny coloring is better. Its texture is better. The aroma, better. The flavor, better. Above all, its himo (string) surpasses its parent. It’s delicious as nigiri. Wrapped in nori, delicious once again. Sandwich it with cucumber, even more delicious.

Out of the aka gai that we can get ahold of at Tsukiji, the ones from Yuriage (Miyagi) are the best, and I can distinguish them just by looking at their shells. Also, no others have such plump flesh.

It’s extremely thick, yet it’s mysteriously soft. Its coloring is natural and elegant. Its texture and its aroma when you chew on it are wonderful. As soon as I slice into it, the aroma of the ocean fills up the air in the kitchen. At any rate, all the criteria are filled three and fourfold. And it’s an appropriate size to make one piece of nigiri.

Its season is winter. However, we serve it all year round since there are a lot of requests. This didn’t just start; ever since I began working at Kyobashi, sushi restaurants in Tokyo have used it in the summertime as well. There are seas where their fishing doesn’t get prohibited.

In July and August, when fishing them is banned in Yuriage, the ones from Kyushu come into Tsukiji. The aka gai from Kyushu can’t compete quality-wise or fetch high prices, so they only send it in the summertime when Yuriage is off-limits.

So in the summer, I use the ones from Ise or Kyushu, but the ones in 1997 were especially, unexpectedly good. The coloring of the flesh was beautiful, and with those hues, most people wouldn’t have caught on if I said, “This is from Yuriage.” But of course, the flesh is a bit thin. Even right after they’ve laid their eggs and the ban is lifted, the yuriage never comes in that thin. They simply don’t taste the same.

I don’t put it through vinegar. As soon as the order comes in, I peel its shell, then use it raw to make nigiri to keep the flavor. If it’s pickled in vinegar, then the nice aroma of the sea will disappear. Before the war, to avoid food poisoning, they put all the nigiri neta through vinegar. They made nigiri with maguro (tuna) after marinating it in zuke (soy sauce marinade), and even whitefish was pickled in vinegar or with kobu (kelp). But by the time I started working at Kyobashi, we no longer put it through vinegar and made raw nigiri.

At any rate, it was aka gai from Tokyo Bay, which was right in front of us. It was at the best freshness. Around 1955, plenty of aka gai that was fluffy and soft landed. It was easy to chew on and was moist with no firmness and highly aromatic; the aka gai from Edomae had a wonderfully dreamy flavor.

Even against the Tokyo Bay catches back then, the yuriage compared favorably in terms of its coloring and the flesh’s firmness, and it got increasingly popular. Just like the Berkshire pork from Satsuma that’s lined up in supermarkets, now every store claims, “Our aka gai is from Yuriage.”