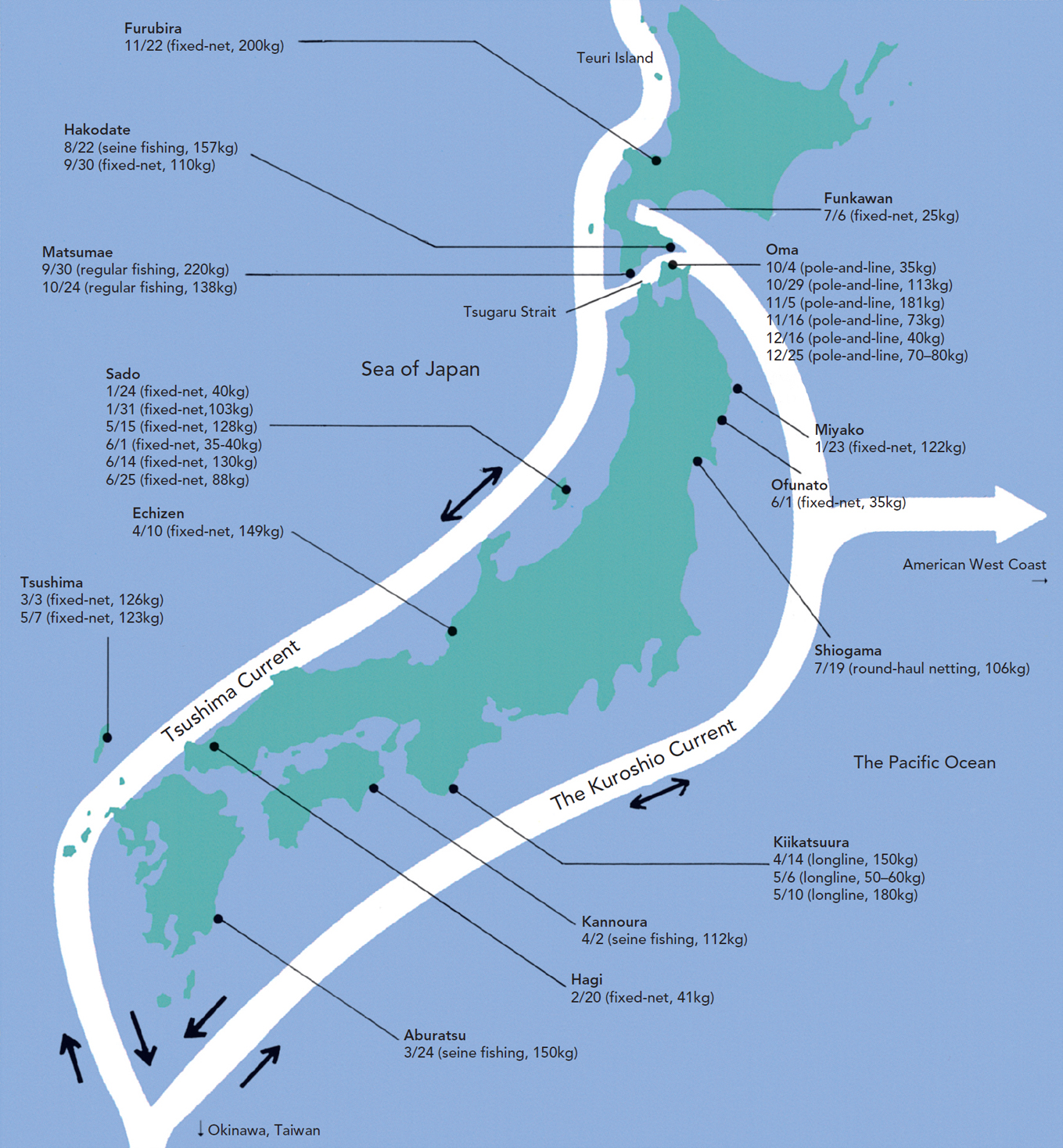

Map of Hon Maguro Migration around Japan

*The record is from May 1993 to Jan 1994 and Jun 1996 to Aug 1997.

Hon maguro from the seas near Japan spawn in the area between Taiwan and Okinawa and swim northward along the coast of Japan. They eat plenty in the seas around Hokkaido rich in food, and the early ones start to swim south around October. There are a few that migrate toward the American west coast, crossing the Pacific Ocean while swimming northward. The locations on this map are the sources of kinkai hon maguro used at Sukiyabashi Jiro, and the dates note when the restaurant stocked them. By following the dates, the migration route of the kinkai hon maguro becomes clear.

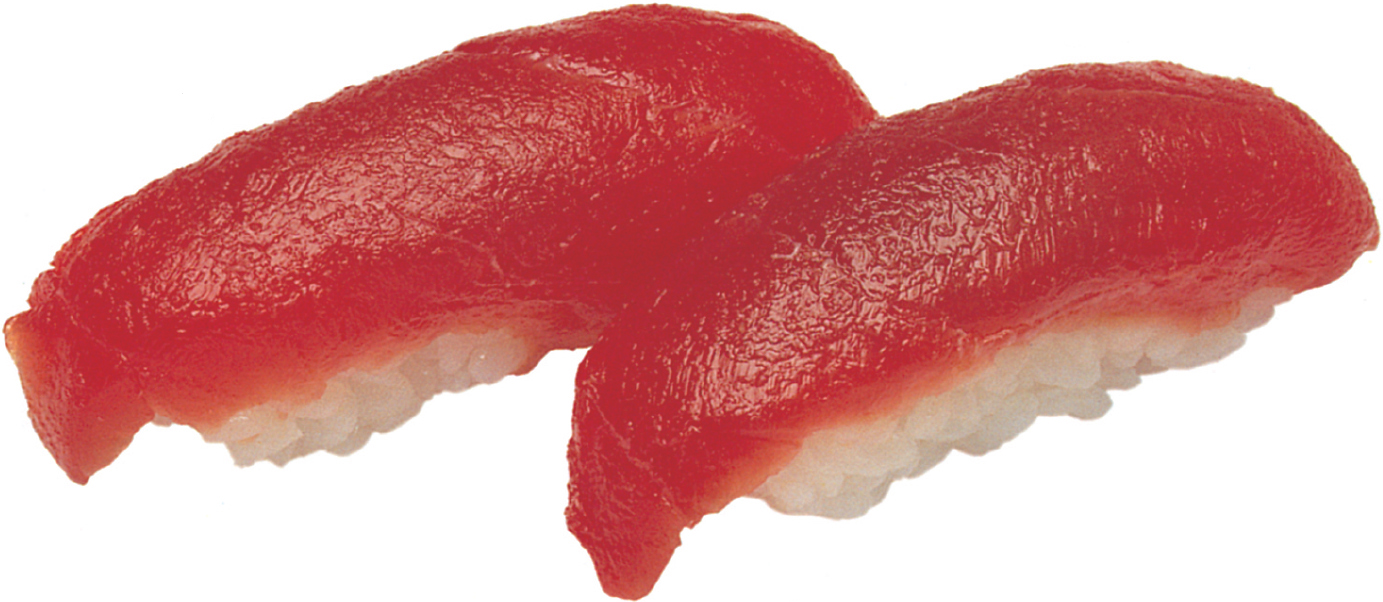

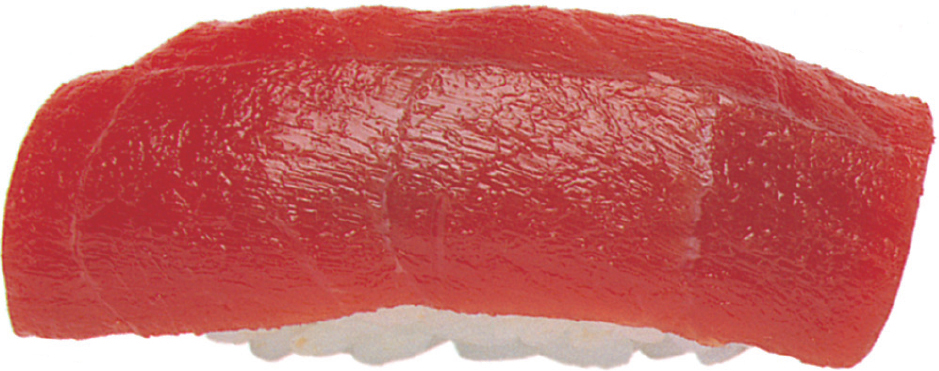

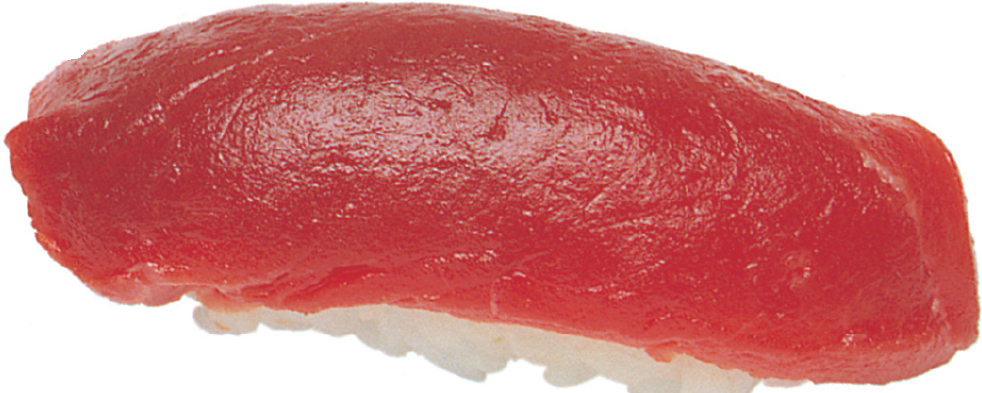

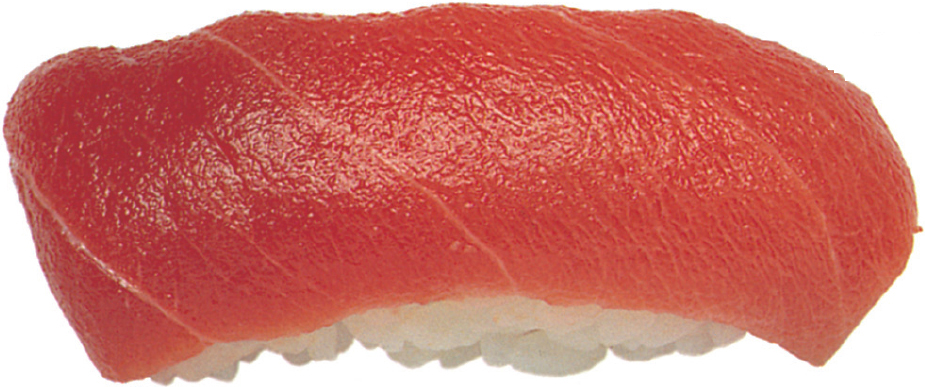

Otoro (Jabara/bellows belly), November, Oma

Out of otoro, “the bellows underbelly” is especially greasy. But its sinew is strong, so it’s matured on ice. It takes skills to calculate when to use it. Rested for too long, its color, which is essential, starts to look dull, and moreover, the softened bellows belly’s sinew stretches too much, which makes it hard to make nigiri with.

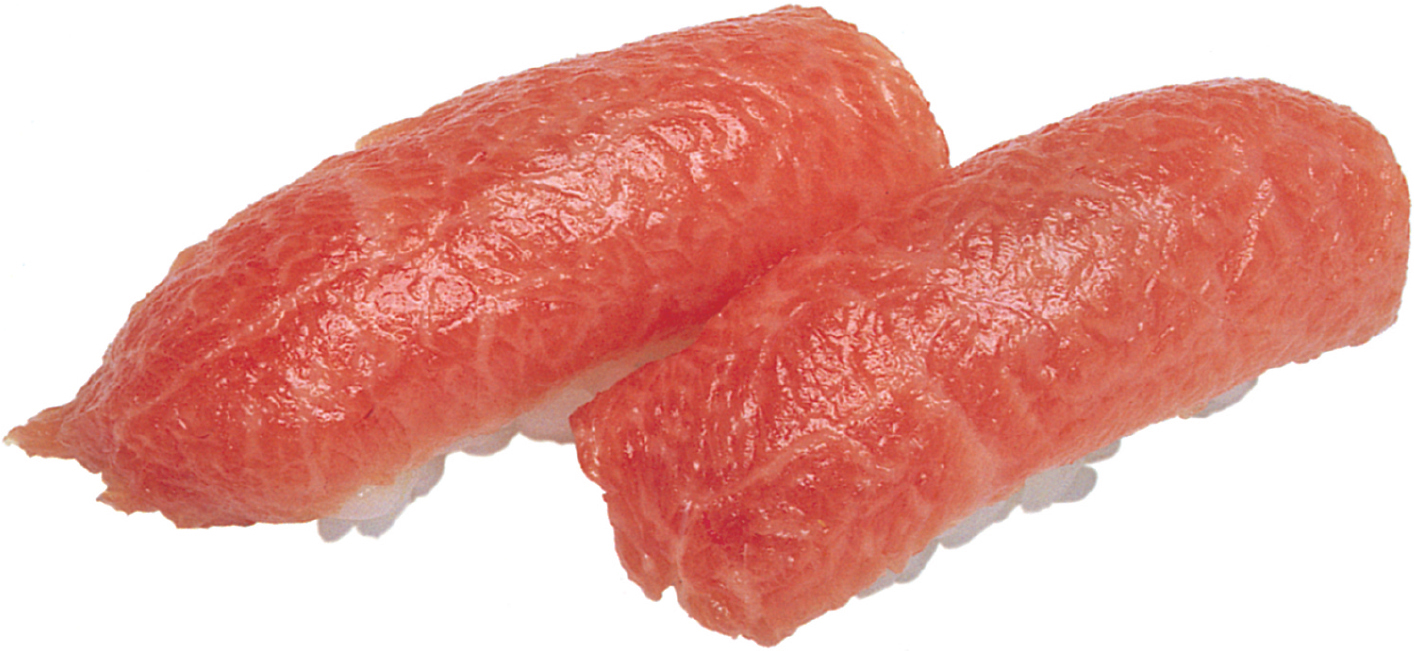

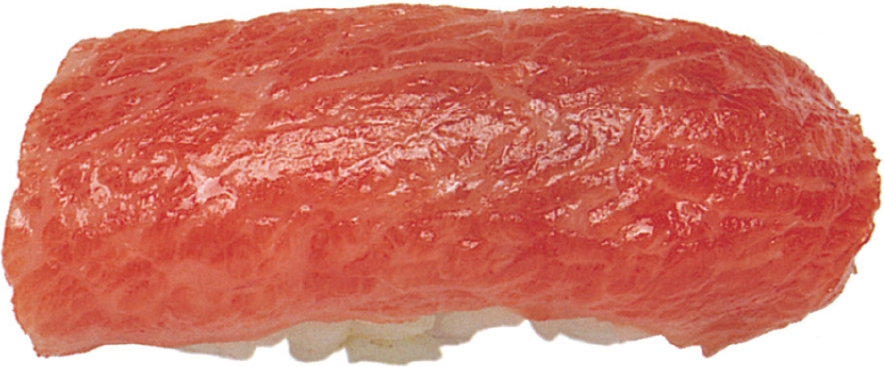

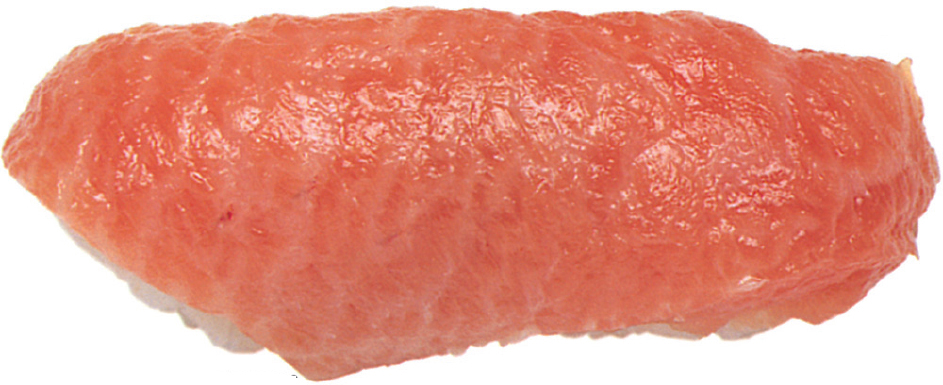

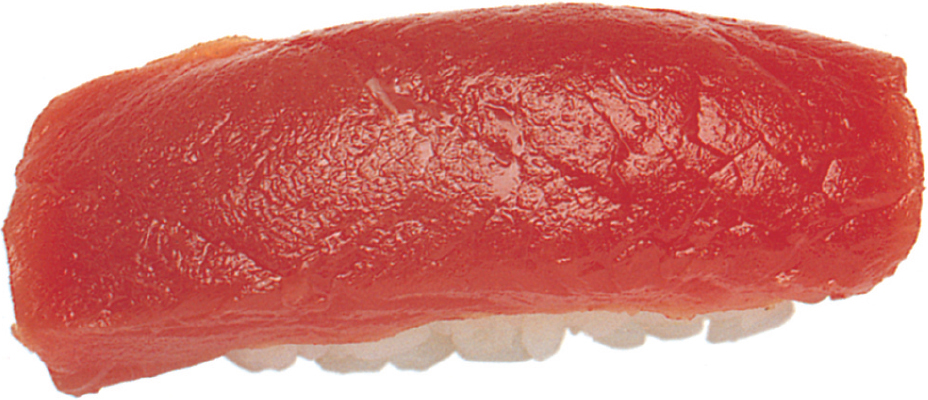

Otoro (Shimofuri/marbled flesh), April, Echizen

“Marbled flesh” is a rare nigiri-dane, but it’s easier to make nigiri with than the bellows belly. The marbled flesh of a maguro that weighs under 150 kg has a light and refined taste like the chutoro of a larger maguro.

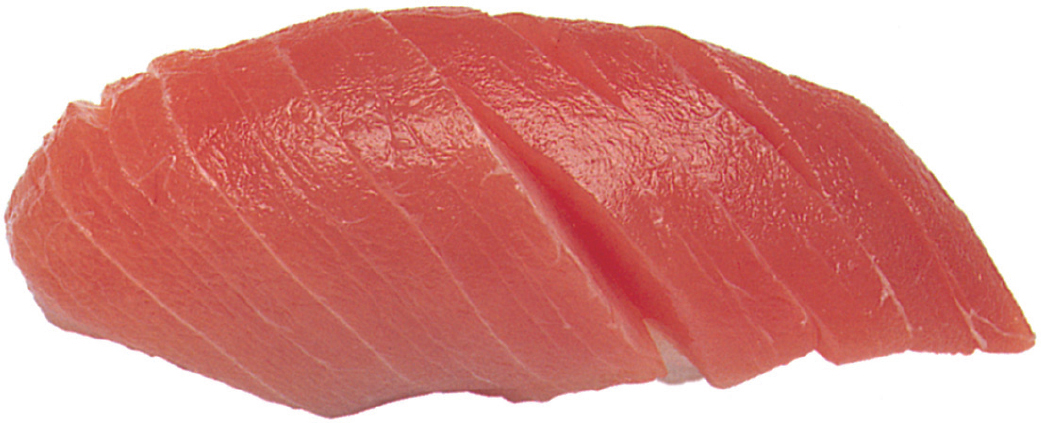

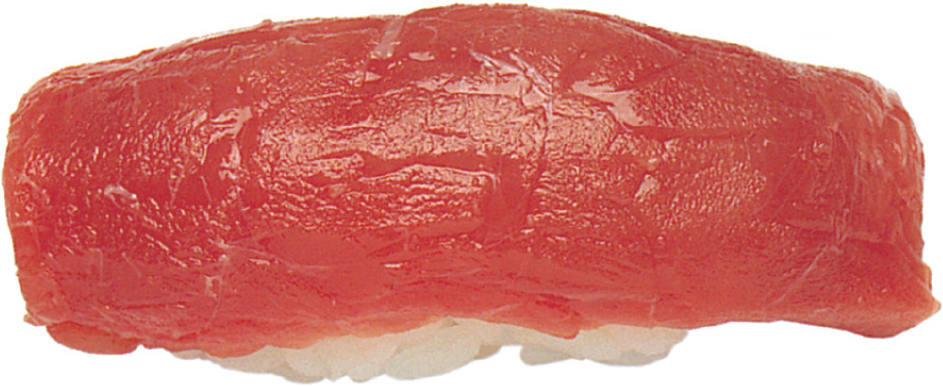

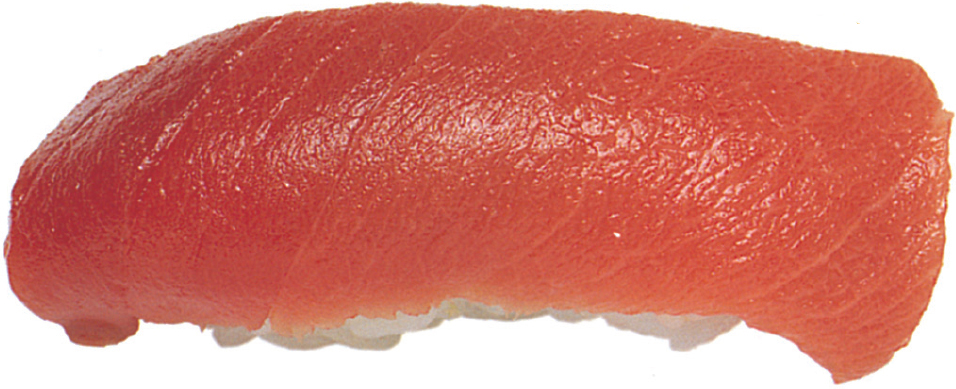

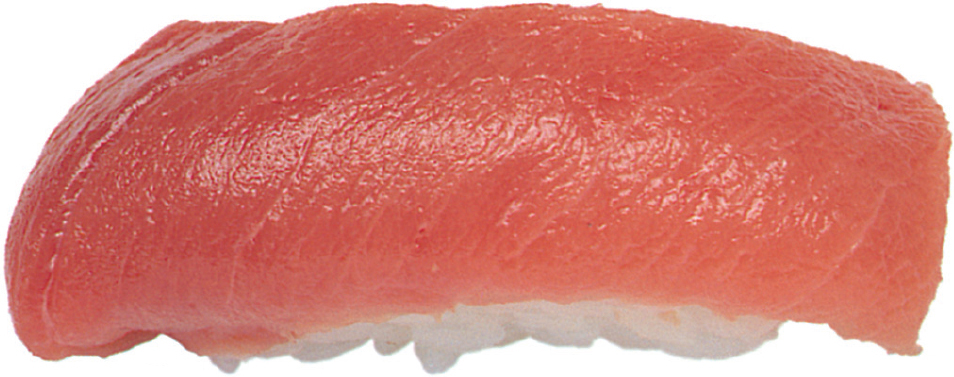

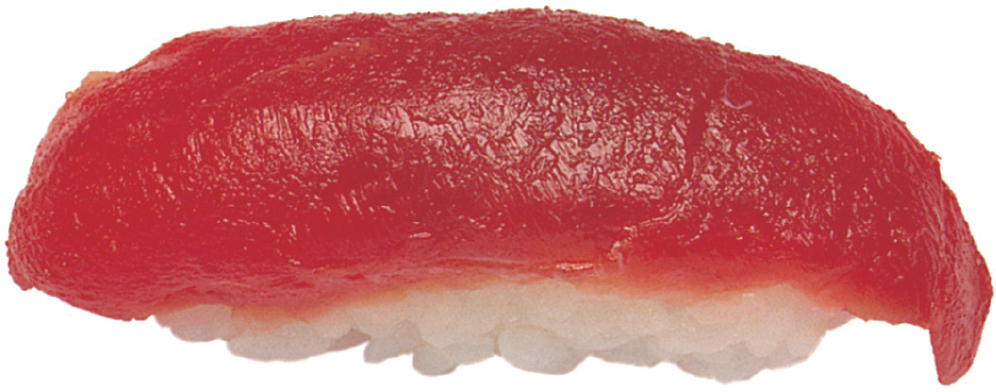

Chutoro July, Shiogama

Chutoro is the best liked. It offers a range from parts where you can enjoy the contrast of fat and lean meat to parts with strong fat.

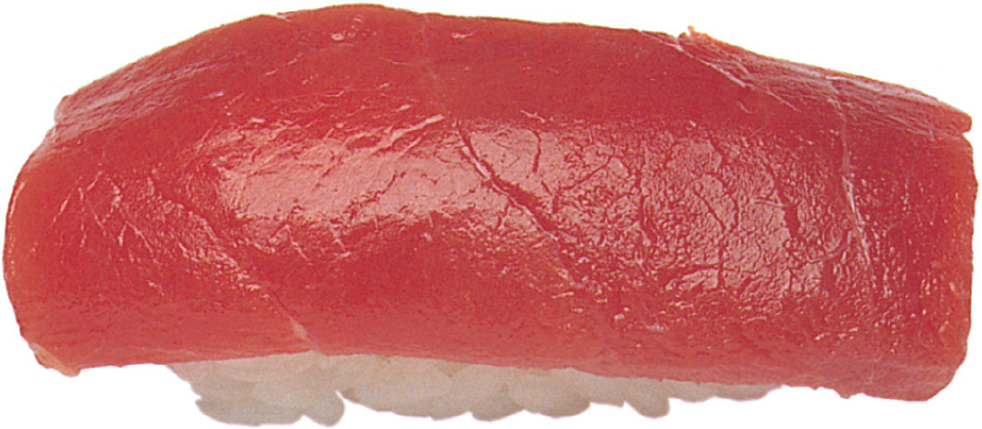

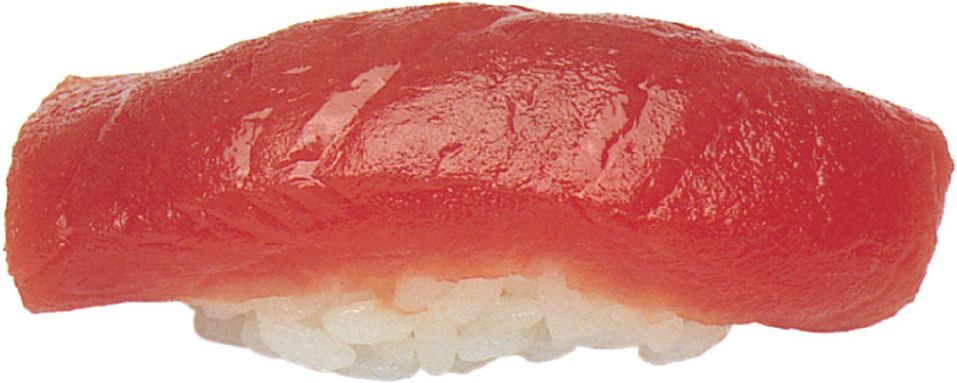

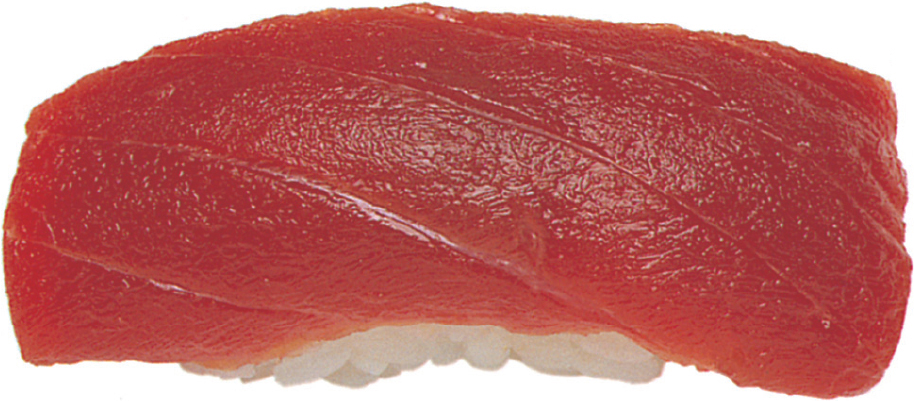

Lean Meat, June, Sado

There are more orders for lean meat lately, more customers who appreciate the pleasant “smell of blood” and the umami brought about by its unique acidity. Lean meat that’s fatty over autumn to winter is extra tasty.

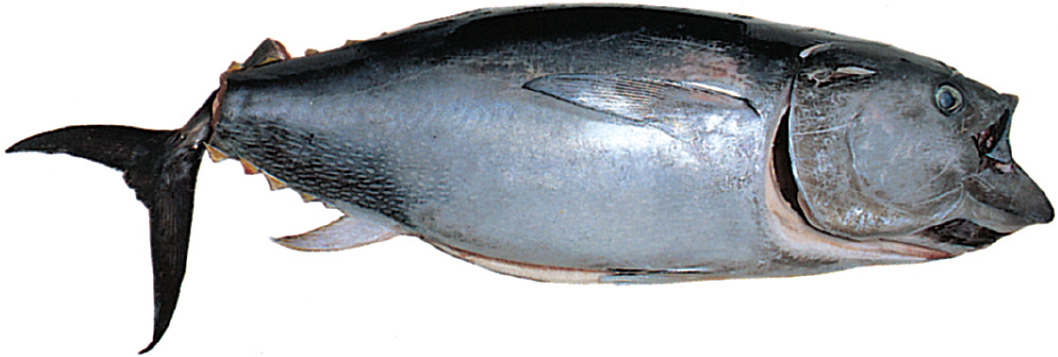

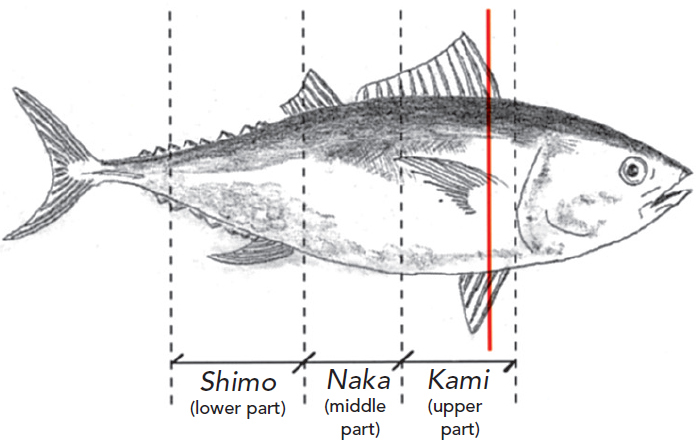

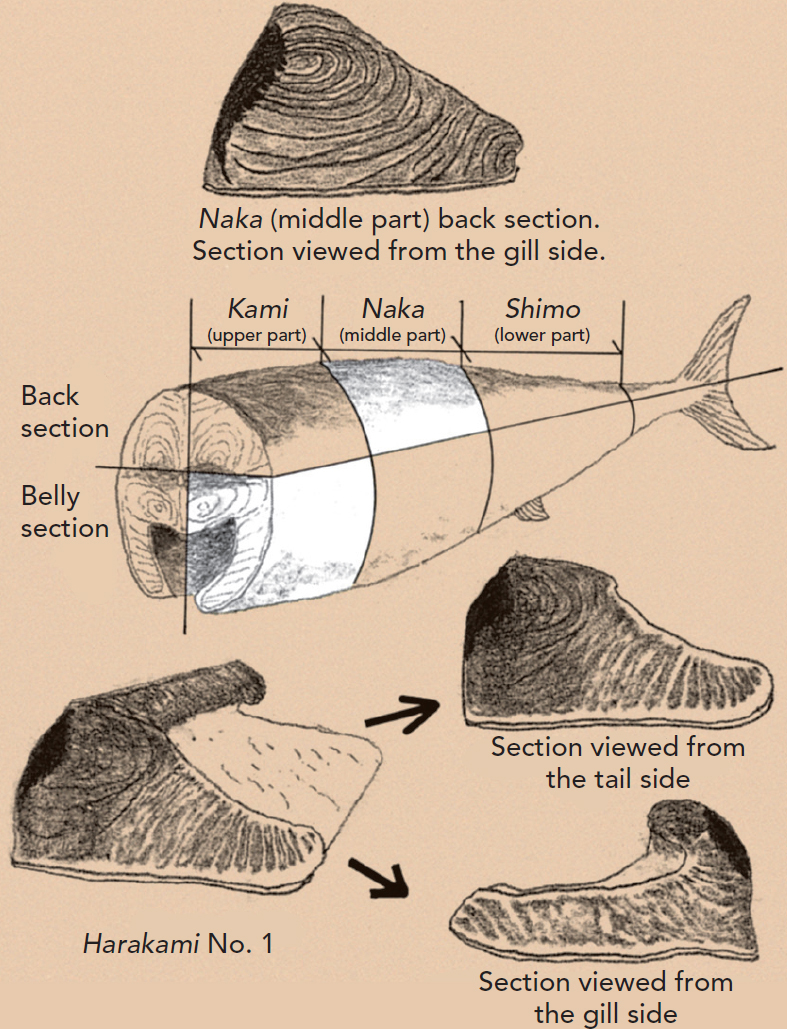

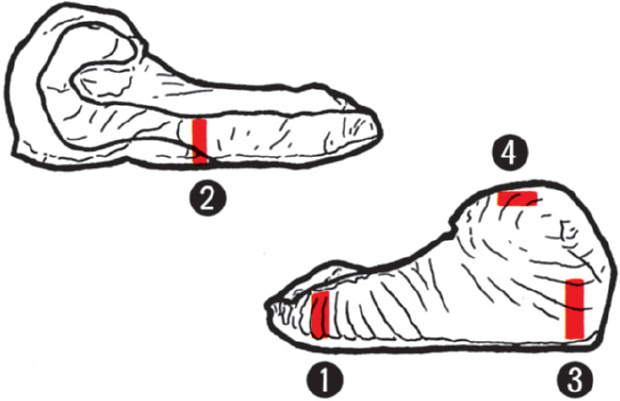

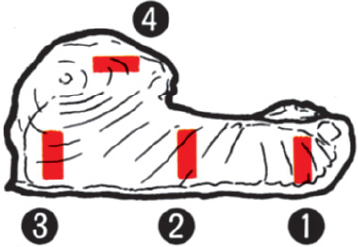

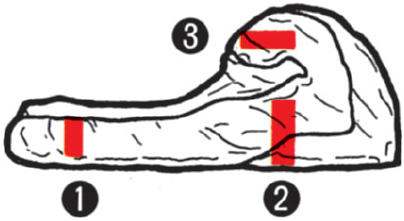

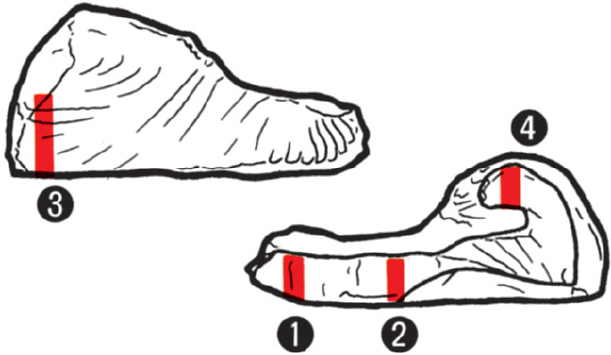

If you start under kamashita (behind the gills) of kinkai hon maguro and divide it in three—kami (upper part), naka (middle part), and shimo (lower part)—you can clearly see the fat, sinew, and coloring. When you make nigiri with it, the difference in the texture of flesh becomes even clearer.

Origin: Oma

Weight: 35 kilograms

Body length: 145 centimeters

Body height: 34 centimeters

Circumference: 93 centimeters

Fishing method: Pole-and-line fishing

Day caught: October 4th

Day photographed: October 7th

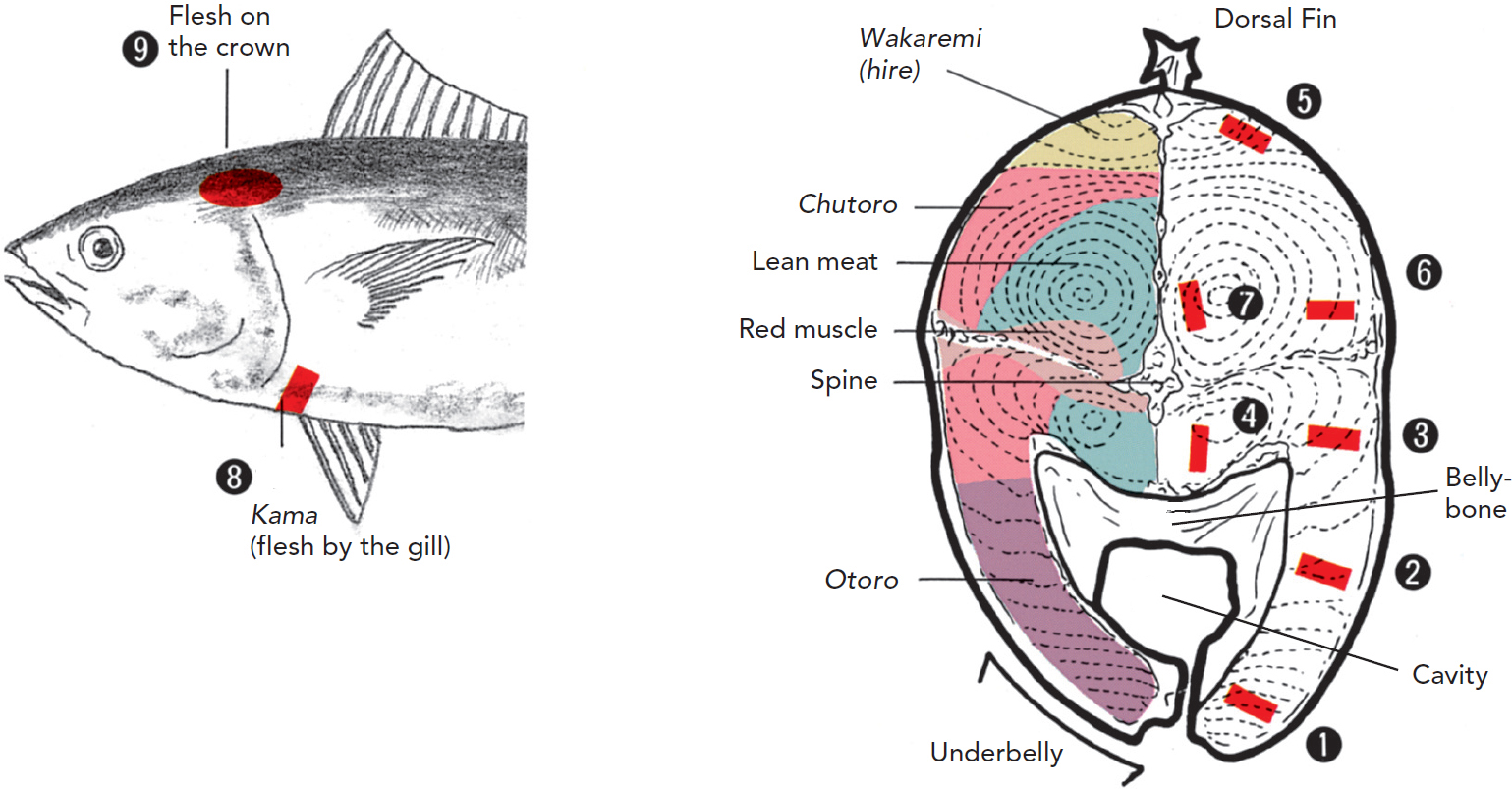

The sliced kami location

Maguro at the market is divided into four parts: upper, lower, belly, and back. So it’s hard to tell the otoro, chutoro, and lean parts. Thus, we bought a whole fish and asked the broker Ishizuka at Tsukiji to cut it into round slices and then photographed them. It’s an unprecedented project. Right after being caught, the color of the lean meat is similar to that of red muscle. But as time passes and it matures, it starts to brown and turn dark and dull. As maguro gets bigger, it gains fat not only on the belly side but also on the back side.

Kamashita (behind the gills). Kami has the most fat on it. The hollow part used to contain internal organs.

1 Kami (upper part), belly section, otoro (jabara/bellows belly)

Underbelly close to the kama side. There’s sinew in a bellows pattern. When it matures, the sinew softens to the point of melting in the mouth.

2 Kami (upper part), belly section, otoro (shimofuri/marbled flesh)

The fat is marbled throughout, and there is no sinew. The fatty content is somewhere between the bellows belly of otoro and chutoro. It’s a rare item for which you get only one to three saku (slab) out of a whole fish.

3 Kami (upper part), belly section, chutoro

There is only a little chutoro in the belly section. It has moderate fat and is liked by everyone.

4 Kami (upper part), belly section, lean meat

Lean meat can be found on top of the belly-bone. The smell of blood gets stronger as the lean meat gets closer to red muscle.

5 Kami (upper part), back section, wakaremi

The back section of kami is found at the root of the dorsal fin. It’s a rare item for which you get only one to two saku out of a whole fish. It’s considered to be more premium than chutoro. It has a smooth and unique flavor that’s in between chutoro and lean meat, but the drawback is that its color changes quickly.

6 Kami (upper part), back section, chutoro

Its fat is weaker than chutoro’s belly section. Especially with smaller maguro, the flesh in this section is easy to split, so it’s common to use it for tekka maki (tuna roll).

7 Kami (upper part), back section, lean meat

You get only three to four saku of lean meat from the belly section, but six to seven from the back section. Those from the back section are better in aroma and acidity than those from the belly section.

8 Kama (flesh by the gill)

Commonly called “the otoro of all otoro,” but the sinew is tough, and it tends to smell fishy. Not appropriate as nigiri-dane.

9 Flesh on the crown

The maguro brokers at the Tsukiji market eat this part at home. It’s the flesh that’s on the bones inside of the head. Softer than the soft kami chutoro in the back section, it has a creamy texture.

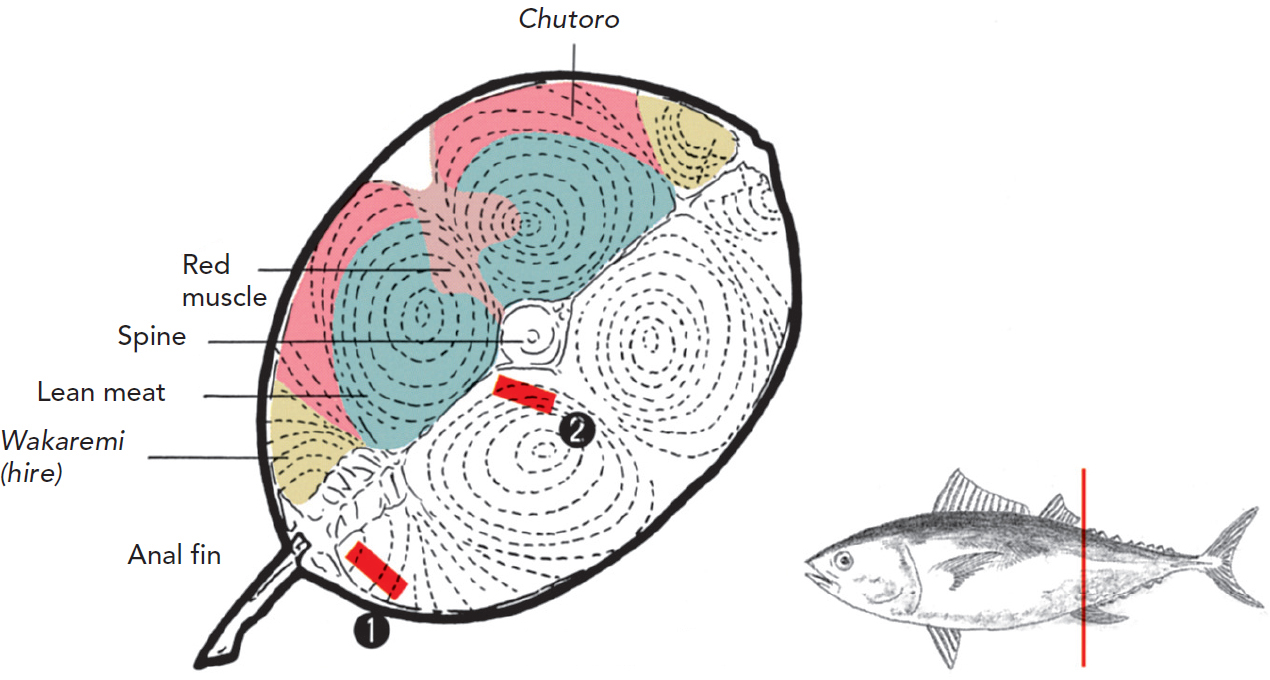

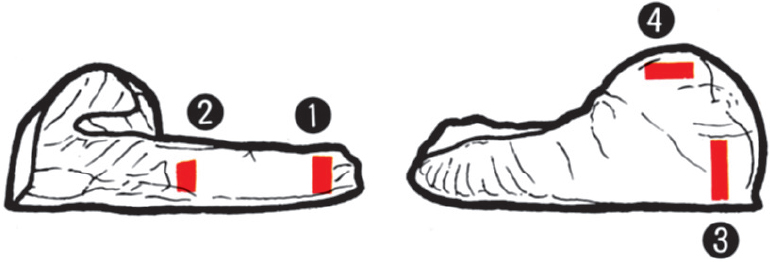

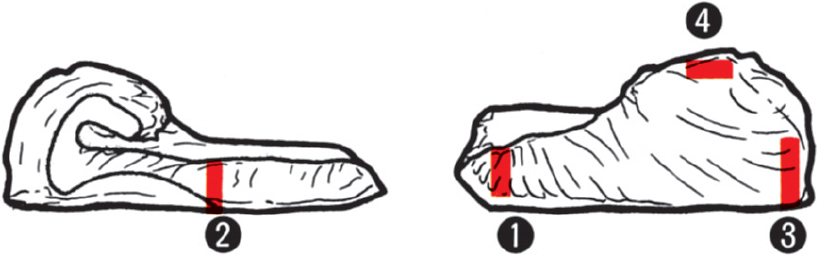

Compared to kami (upper section), any part of naka has a lighter flavor. They say, “For the back, it’s easier to use naka,” because the sinew is softer than in kami.

The sliced naka location

1 Naka (middle part), belly section, otoro (bellows belly)

Compared to otoro of kami, it’s redder and the fat is weaker.

2 Naka (middle part), belly section, otoro (marbled flesh)

The marble texture is finer, and it’s half chutoro. If it’s a small maguro, you barely get one saku (slab).

3 Naka (middle part), belly section, chutoro

The belly of naka has a higher percentage of chutoro. The chutoro of chiaigishi (flesh right by the red muscle) declines in freshness very quickly and should be used as soon as possible.

4 Naka (middle part), belly section, lean meat

A weaker red, the flavor and the aroma also weakens.

5 Naka (middle part), back section, chutoro

In naka, the chutoro close to the back has tough sinew, and the flesh is likely to split.

6 Naka (middle part), back section, chutoro

The flesh right by the red muscle is moderately tight, so of all the chutoro, it’s the easiest part to make nigiri with.

7 Naka (middle part), back section, lean meat

The back section of naka has a greater percentage of lean meat than kami. As it gets closer to shimo (lower part), the sinew gets thinner and harder.

Sliced surface right above the anal fin. There is a little fat in between its skin and its flesh. Because the sinews spread finely throughout, it doesn’t feel smooth on the tongue.

The sliced shimo location

1 Shimo (lower part), belly section, hire (fin)

The flesh found on both sides of the anal fin. Similar to the dorsal fin, it’s fatty because it’s at the root of the fin.

2 Shimo (lower part), belly section, lean meat

Section close to the spine. It’s close to the tail fin so the muscle is developed, and it has umami.

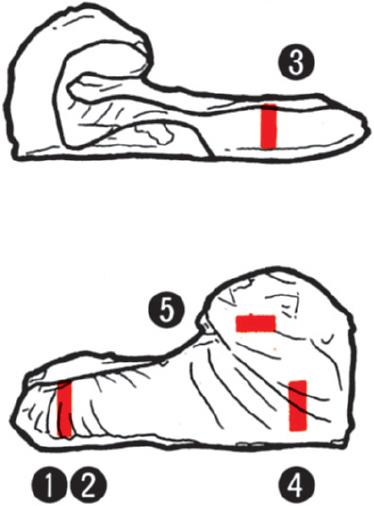

How to peruse “The Sections and Nigiri of Hon Maguro” from here to here

Maguro that they stock at Sukiyabashi Jiro is mainly kami (upper part) of the belly section (harakami No. 1), to make otoro nigiri, and a block from naka (middle part) of the back section, to make chutoro and lean meat nigiri. Section pictures that unfold from the following page show a total of thirteen pieces that include twelve pieces of kami of the belly section from over twelve months, and one piece of naka of the back section from October. Out of them, the belly section from February, November, and December and the back section from October are in their actual sizes. All nigiri are printed in their actual sizes as well.

• Data showed next to the section pictures

Origin: The locations of the catch and landing

Size: Weight of maguro including the head at the time of arrival

Part: Harakami is the belly section close to the head

Fishing method: Affects the quality of meat of maguro

Day photographed: Date purchased by Sukiyabashi Jiro (It’s either the day of arrival at Tsukiji Chuo Market, or a couple of days after.)

• About uwami and shitami (top and bottom flesh)

When you place fish with its head facing left and its belly to you, we call the flesh on top uwami and the flesh on the bottom shitami. In the case of maguro, they determine which side of the flesh is the top or the bottom soon after it’s caught by how it lay on a fishing boat. Because the flesh on top weighs down on the flesh on the bottom, causing it to fall apart, the flesh on top is considered to be of better quality. However, depending on where they were caught, sometimes maguro get flipped around, so the difference in quality is not always clear. Here, for the sake of convenience, we determined the flesh on top to be when the head is facing left.

• Looking at the photos

For the section photos of maguro, as a rule, the section viewed from the tail side is enlarged, and the section from the gill side is reduced.

Shoot period: From June 1996 to August 1997.

From November to December 1993.

Also for the first time in history:

A Complete Exploration of Kinkai Hon Maguro

that they use throughout the year at Sukiyabashi Jiro!

When summer is gone, and autumn arrives, there is a switch: from mako garei (marbled sole) to hirame (flounder) with whitefish, and from aji (horse mackerel) to saba (mackerel) with silver-skinned fish. The kohada (gizzard shad) that they use throughout the year also gradually gets bigger and fattier. This is what the “season” is about. Of course, there is a season for maguro, too. However, no one has tried to compare and examine the pictures of maguro in and out of its season. We followed the kinkai hon maguro that they actually used at Sukiyabashi Jiro over the course of a year, and compared the fattiness, changes in colors, and the condition of the sinews.

January

Size: 122 kilograms

Part: Harakami No. 1 (shitami)

Fishing method: Fixed-net fishing

Day photographed: January 23rd

A much-awaited top-notch specimen that arrived right after New Year’s in 1997. At a glance, you can tell, “This is good. It’s fatty.” Judging from the whiteness of the film on top of the belly bone, you can tell that it’s a “young” (recently caught) maguro. It becomes good to eat after letting it mature over a bed of ice for four to five days.

1 Otoro (bellows belly)

The second saku (slab) from the underbelly. It has hard sinews, so it’s used after resting for five days.

2 Otoro (bellows belly)

It’s now good to eat. Compared to the nigiri on top, the sinews have softened.

3 Otoro (marbled flesh)

Kama-side section closer to chutoro. The fat melts slowly on the tongue.

4 Chutoro

The second saku (slab) from the red muscle. You can enjoy the flavor contrast between toro to lean meat in this one piece.

5 Lean Meat

It has plenty of fat on it. If you let it rest for four to five days, the acidity and the aroma become richer.

February

Size: 41 kilograms

Part: Harakami No. 1 (shitami)

Fishing method: Fixed-net fishing

Day photographed: February 20th

Maguro that was in the middle of swimming southward in the Sea of Japan. It has a plain smooth flavor, because it’s small. Three to four days had passed since it was caught. The day of the purchase and the following day was the best time to eat it. It wasn’t taken care of well after it was caught, so the maguro’s body temperature didn’t decrease, which resulted in the flesh burning a bit.

1 Otoro (bellows belly)

It has strong fat, but there is no greasiness to it. You can see thin veins on the surface. A characteristic of small maguro.

2 Chutoro

The quality of the flesh is soft, it has a solid flavor, and there is no greasiness to it.

3 Lean Meat

There is an acidity to the flavor as if this is a larger version of meji (young maguro). Because it’s small maguro, the redness is faint.

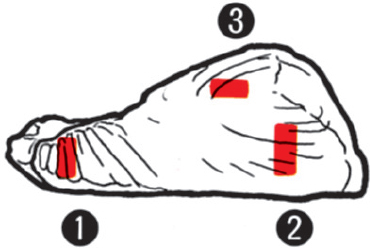

Origin: Tsushima

Size: 126 kilograms

Part: Harakami No. 1 (uwami)

Fishing method: Fixed-net fishing

Day photographed: March 3rd

In a typical year, this is a time when most of the hon maguro are caught off Tosa, Kiikatsuura and Miyazaki, but in 1997, many came from the Sea of Japan. The form and the fattiness were not any worse than the one from Miyako in January. It was a bit young, so it became good to eat after three to four days.

1 Otoro (bellows belly)

The saku from the area close to the skin has a narrower gap in between sinews, so slice into it as if you’re cutting off the sinews before making nigiri with it.

2 Otoro (marbled flesh)

The marbled patterns are more distinct with maguro that weigh over 100 kilograms.

3 Chutoro

The second saku (slab) from the red muscle. The lean meat and the fatty part create a vignette of colors.

4 Lean Meat

It’s aromatic and has a slight sweetness and acidity. According to Jiro Ono, “It tastes much better than the 41-kg maguro that I used in February.

April

Size: 149 kilograms

Part: Harakami No. 1 (shitami)

Fishing method: Fixed-net fishing

Day photographed: April 10th

April saw steady stock: a 112-kg from Kannoura, Kochi and a 150-kg from Kiikatsuura. But then, maguro that the brokers put a stamp on—“the colors turn fast, but the flavor is the best”—came in. It’s rare to find maguro this fatty in this season.

1 Otoro (bellows belly)

It’s young, so the sinews are hard. It becomes good to eat after three to four days, but the bellows belly stretches loose, so it becomes hard to make nigiri with it.

2 Otoro (marbled flesh)

Unlike bellows belly otoro, the flesh is firm so all you have to do is to tighten both sides to make nigiri with it. It has strong fat, so slice it thin.

3 Chutoro

Good quality maguro is distinct in its moist feel to the touch. The redness becomes stronger as it gets closer to red muscle.

4 Lean Meat

The one that arrived two days before couldn’t be used because it was “bald maguro” with no umami at all. With this lean meat with fat, the colors may turn fast, but it has a great aroma and umami.

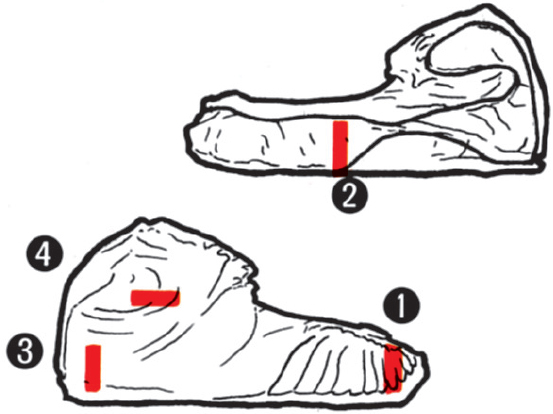

Origin: Tsushima

Size: 123 kilograms

Part: Harakami No. 1 (uwami)

Fishing method: Fixed-net fishing

Day photographed: May 7th

A lot of maguro is caught with hikinawa (seine fishing), and this maguro was the only one that was caught with teichiami (fixed-net fishing). It has the same origin as the maguro from March, and the shape is almost identical. But it doesn’t have too much fat on it, so the lean meat is prominent. Overall, it tasted young like meji (young maguro).

1 Otoro (bellows belly)

The stamina of maguro caught in seas around Japan tends to decline in May, but this one has a decent fat layer. Its colors may fade quickly because it wasn’t handled right subsequent to its capture.

2 Otoro (marbled flesh)

It has become good to eat. The fat spreads as soon as you put it in your mouth.

3 Chutoro

In the plain smooth fat is a strong sweetness.

4 Lean Meat

The acidity and the aroma are light. Jiro Ono was impressed saying, “Even though it’s maguro from May, it has so much umami.”

June

Size: 130 kilograms

Part: Harakami No. 1 (shitami)

Fishing method: Fixed-net fishing

Day photographed: June 14th

In June, chubo (medium-sized maguro) arrives from Sanin. And mixed with large-sized maguro that were caught with makiami (round-haul netting) from off Choshi and Sanriku, the “teichiami” (maguro caught with fixed-net fishing) comes in from Sado. Still skinny, it was on its way north to Hokkaido, chasing after food. Out of seven kinkai maguro that were auctioned at Tsukiji Market that day, this one was evaluated to be the best.

1 Otoro (bellows belly)

Despite its large size, the belly flesh is thin, and the fat is weak. It tastes plain.

Kama section of the area close to the red muscle. Out of chutoro, this is a section with a strong blood aroma.

3 Lean Meat

Because it only has a little fat, the colors hardly turn with lean meat.

Origin: Shiogama

Size: 106 kilograms

Part: Harakami No. 1 (uwami)

Fishing method: Round-haul netting

Day photographed: July 19th

There aren’t too many good quality hon maguro in the summertime. Even when brokers win bids thinking they were good maguro, there are times when after it’s opened it’s all black inside and can’t be used. This one from Shiogama a day or two after the catch is fatty for summer maguro. With maguro in the summertime, if you let it rest for two or three more days, the umami will increase, but the colors fade quickly, so it’s hard to determine the timing.

1 Otoro (in between bellows belly and marbled flesh)

Because it doesn’t have strong fat, it’s not greasy and has plenty of umami.

2 Chutoro

This nigiri is from a section next to the clavicle, which bites into the flesh, at the border of otoro and chutoro on the kama side. Because it’s summer maguro, it’s skinny and has less fat.

3 Lean Meat

It’s moist and smooth. When you let it rest, its flavor deepens, but it doesn’t make as much of a difference as with otoro. The color fading is the bigger issue.

Origin: Hakodate

Size: 157 kilograms

Part: Harakami No. 1 (Shitami)

Fishing method: Seine fishing

Day photographed: August 22nd

Although the ones from Oma and Matsumae that came in at the beginning of August looked nice and red, they were just okay fattiness-wise. After July 15th, a bountiful twenty-two maguro came in from Shiogama and Kesennuma. But they were all too skinny. Out of the ten maguro from Hokkaido in the next batch, this one from Hakodate was of the best quality. Even the broker who won the bid was surprised, saying, “This is superlative summer maguro. I haven’t seen one with a belly this thick in recent years.”

1 Otoro (marbled flesh)

It’s fatty like an oma from the beginning of autumn. At this level, even if you let it rest until it’s good to eat, you don’t have to worry about the colors fading.

2 Otoro (bellows belly)

From the kama side of an underbelly saku (slab). Compared to bellows belly otoro on the tail side, it has strong and hard sinews. Typically, you carefully get rid of them after cutting out the saku.

3 Chutoro

The saku (slab) next to red muscle. Tane has been sliced on the long side, but instead of chopping off the excess, fold in while making nigiri. The flavor of chutoro is only complete when the range from lean to fatty is featured.

4 Lean Meat

From saku (slab) next to bone, sliced from the tail side. Unlike typical summer maguro lean meat, you can clearly see that it’s fatty.

Size: 110 kilograms

Part: Harakami No. 1 (uwami)

Fishing method: Fixed-net fishing

Day photographed: September 30th

The first delivery of the season in 1996. This one was caught around the Tsugaru Strait, and according to Jiro Ono, “Maguro should be from Hokkaido, after all. When I make nigiri with it, I can tell the difference.” It’s on the smaller side, but the belly flesh has an extra thickness to it. A “young” maguro has nice colors and a glossiness but doesn’t produce enough umami. If you let it rest for three more days, the flavor will increase, but the colors may dull down a bit.

1 Otoro (bellows belly)

When you cut into the tane, a knife hits hard on the sinews of maguro imported from overseas. However, a knife can move smoothly through kinkai maguro.

2 Otoro (marbled flesh)

You can only get two or three “shimofuri (marbled)” saku (slabs) from this block. If you let it rest for two days, the flavor deepens enough to make you purr.

3 Chutoro

Chutoro from the area close to the red muscle. The gradual transition from lean meat to toro strikes a nice balance.

4 Lean Meat

It’s glistening because it’s fatty. If you don’t slice it on the thicker side, lean meat feels like its mouthfeel is lacking.

October

Size: 138 kilograms

Part: Harakami No. 1 (shitami)

Fishing method: Regular fishing

Day photographed: October 24th

According to Jiro Ono, “When caught with ipponzuri (pole-and-line fishing), tsuri (fishing) or ami (net), the flesh quality of maguro is plain and smooth. On the other hand, ones caught with nawa (rope, or a long line with many hooks) have too strong fat and their burnt colors bother me as well.” This maguro from Matsumae has vivid colors. The quality of flesh was moist and it also had good fattiness.

1 Otoro (bellows belly)

Because it’s too young, the sinews are hard. If you slice it thick, you can’t chew it off. Let it rest and mature for three to four days.

2 Otoro (marbled flesh)

It looks crunchy and hard. When the flesh is this young, when you cut out the saku (slab), you don’t have to worry about the color fading right away.

3 Chutoro

Chutoro from near red muscle has a strong aroma of blood. It’s aromatic like lean meat but also fatty.

4 Lean Meat

Compared to catches from Matsumae (pole-and-line), “There was something missing from the flavor,” says Jiro Ono.

Origin: Furubira

Size: 200 kilograms

Part: Harakami No. 1 (shitami)

Fishing method: Fixed-net fishing

Day photographed: November 22nd

Lately, there are fewer large kinkai maguro that weigh over 200 kilograms. This one was caught off the coast of Shakotan Peninsula, and the belly part is plump with a nice fatty layer. When it gets this big, the sinew starts to appear clearly in the kama section too. After letting it rest for a week, it’s good to eat starting with the exposed parts.

* This spread folds out to three pages. Enjoy it in the actual size, in all its grandeur.

1 Otoro (bellows belly)

Dense but clean fat. It has a rich taste unique to omaguro (large tuna).

2 Chutoro

While it’s a chutoro with evenly spread fat, out of a large block you get only three to four saku (slabs).

3 Lean Meat

It loses its glossiness after maturing, but softens while maintaining a firm texture.

Size: 40 kilograms

Part: Harakami No. 1 (uwami)

Fishing method: Pole-and-line fishing

Day photographed: December 16th

Maguro from Oma keeps rising in reputation. The quality is good, and it’s taken care of skillfully, so they can charge a high price as soon as it’s labeled an oma. Although small, this one was the best in recent years. No hon maguro has appeared to surpass this “40-kg oma” yet.

1 Otoro (bellows belly)

Because it’s a small maguro, the gaps between sinews are narrow. But there is no greasiness to the flesh.

2 Chutoro

Light flavor gradation.

3 Lean Meat

Plenty of aroma and sweetness, and a depth to the flavor.

Back Portion

Origin: Oma

Size: 113 kilograms

Part: Naka (middle) back (shitami)

Fishing method: Pole-and-line fishing

Day photographed: October 29th

The Harakami No. 1 block has a lot of otoro. A back portion is also purchased in order to have enough chutoro and lean meat. The back portions from the upper and tail parts have hard sinews, so Sukiyabashi Jiro uses naka (middle) blocks. If it’s the same maguro, lean meat from the back is much better, flavor and color-wise, than lean meat from harakami.

|

Naka (middle) section of maguro |

Red part (left) |

1 Chutoro

Harakami has richer fattiness, but the back portion has better aroma and umami.

2 Wakaremi (hire)

The meat flanking the fin is called “wakaremi.” Stronger fat and aroma compared to lean meat, and more depth in flavor than chutoro, but you only get one or two saku (slabs).

3 Lean Meat

Plenty of aroma and umami. With a little more time, the flavor will deepen.

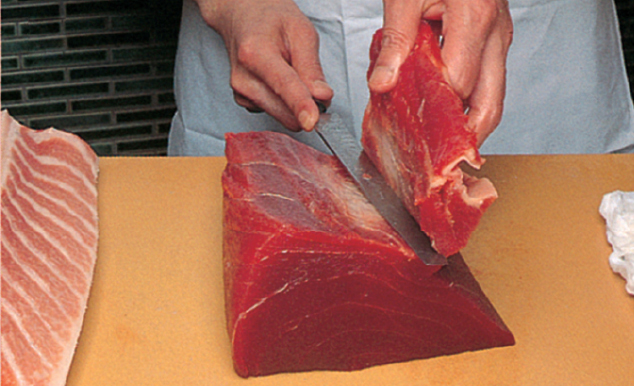

1 Insert the knife in between the red muscle and lean meat.

2 Carve out the red muscle as if you’re peeling it.

3 Insert the knife parallel to the cutting board and according to the thickness of the bellows part.

4 Separate the lean meat.

5 Using the collarbone on the kama side as a guide, divide and slice apart otoro and chutoro.

6 From the left: lean meat, chutoro, and otoro. For harakami no. 1 from a 180-kg maguro, the ratio is 2:3:4.

7 Slice apart one saku of marbled otoro. The thickness should be 2.5 cm (an inch).

8 Slice apart one saku of bellows belly on the underbelly side. The white fat right by the skin has a smell, so remove and discard.

9 Slice apart one saku of chutoro by the red muscle. It has a vivid contrast ranging from lean meat to toro.

10 Slice off the membrane of the abdominal cavity that remains on the block of lean meat.

11 Slice the first saku of lean meat as if you’re cutting off the sinews vertically.

12 From the left: lean meat, chutoro, marbled otoro, and bellows belly otoro.

(soy sauce-marinated tuna)

Zuke of maguro, March, Aburatsu

Adding umami by marinating maguro that has started to look dull in nikiri (thin and sweet glaze) originated in the past. The refreshing sanguine aroma inherent in lean meat disappears, but the richness unique to zuke comes forth. Sukiyabashi Jiro marinates enough for three to four people. Reservation required.

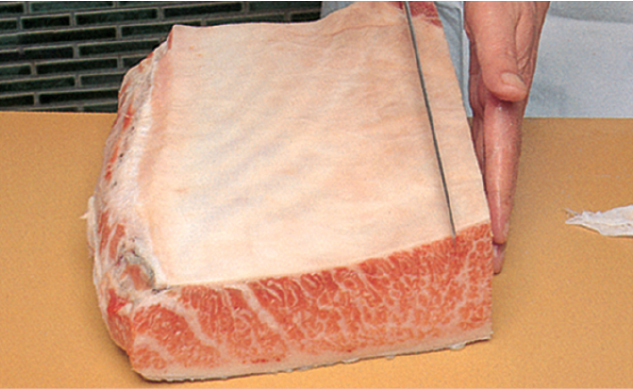

1 A 150 kg from Aburatsu—get a saku (slab) out of the naka back portion. The first saku next to the edge is too soft and not the best for zuke.

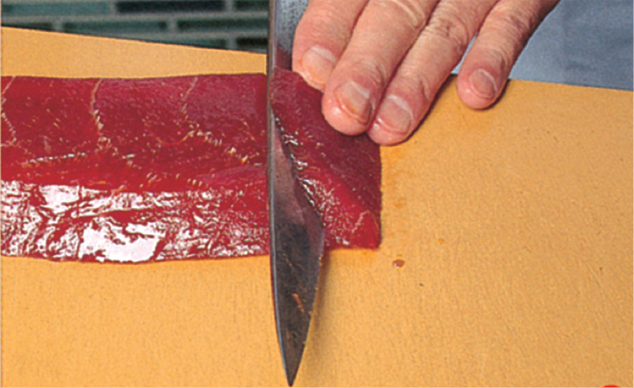

2 Run the knife through as if you’re cutting off the sinews vertically.

3 Slice off a slab at the regular thickness for lean meat.

4 The part doesn’t determine how the saku is scored, but depending on the quality, how much it marinates differs. The richer the fat, the less absorbent.

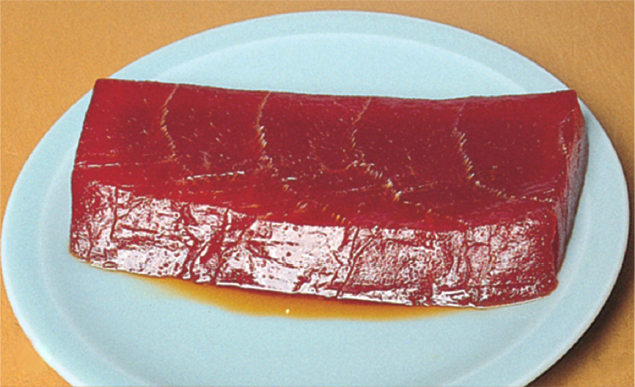

5 Marinate the maguro saku (slab) in nikiri (cooled down reduction sauce of sake and soy sauce).

6 Marinate it at room temperature for half an hour, and it’s done.

7 Slice as thick as normal lean meat. If the nikiri hasn’t soaked in enough, then after making nigiri with it, brush some on the middle.

MAKING NIGIRI WITH HON MAGURO

“I’ll tell you what the pops of a sushi restaurant who insists on ones from nearby seas really thinks.”

The appeal of kinkai hon maguro (bluefin tuna from “near” or Japanese seas), a.k.a. shibi (adult tuna), is the sweet smell of its blood. And the beautiful colors of the nigiri. But hon maguro (bluefin tuna), especially its otoro (fatty tuna), is expensive. It’s expensive, but sushi chefs still make nigiri with it, prepared to be in the red. This is a story of pride about “the King of Nigiri.”

Ever since Edomae-style sushi was created, “the Yokozuna (sumo wrestling champion) of Nigiri” has been kohada (gizzard shad) and “the Yokozuna of Makimono (roll)” kanpyo (dried gourd). And shibi (adult bluefin tuna), good to make nigiri with and good to roll, is surely worthy to be called “the King of Sushi.”

As shibi gets more delicious, making nigiri with it feels different to the touch, especially during the season when it gets extra fatty, from late autumn to winter.

And when you bite into it, a subtle sweet and sour aroma wafts through the nose, and an unobtrusive, light sweetness and bitterness spread in the mouth. This precisely is the aroma and flavor of the blood of red-fleshed fish that swim around the vast ocean. At a glance, it looks shiny with its fat spread evenly, but it feels quite greasy. Even the sinew that’s supposed to be hard melts once it touches the tongue.

I think we can say that the appeal of kinkai hon maguro is the refreshing aroma and flavor of its blood. But since they’re ever so subtle, the only time you clearly feel them is the moment you put it in your mouth, and then as you chew, you can’t identify it any longer.

Not only for maguro but also for other neta, you can discern the subtle differences in aroma by pushing the neta onto your palate the moment you put it in your mouth. Ascertain the aroma by letting the smell travel up through the nose. You can’t tell just with your tongue; there are different parts of the taste buds that are sensitive to sweetness, sourness, saltiness, bitterness, and spiciness, so don’t taste with your tongue but with your nose. This technique is not taught by anyone but is something you have to learn naturally as a chef.

Having said that, with maguro the color is essential. The vivid shine, as if it’s dripping, does much to stimulate your appetite. The glossy and deep-colored lean meat. The little fatty droplets that shine on the neta’s surface with chutoro (medium-fatty tuna) and otoro (fatty tuna). The white shari (vinegared rice) foundation. Facing the beautiful contrast of red and white and thinking “oh, it looks so good” deepens your experience of the flavor.

For a sushi restaurant master, bringing these colors and umami to life and making them coexist is a chance to show off.

Young maguro that has just been caught may have a nice coloring, but the flesh still feels crisp, and its sinew is too hard to chew. Its blood has a fishy smell that’s far from a nice aroma.

So if a maguro you buy is “young” (just caught), you have to wait for it to mature on ice. Once it’s matured, the sharp and fishy smell turns into a refreshing aroma. The fat spreads gently around the sinews of the otoro, and they soften. Its flavor and aroma reach their peak after it matures, and the fresh red meat starts to turn dark and dull. It’s true, especially for the otoro and chutoro portions. Much like beef, the stage before it starts to oxidize is when the flavor deepens; there are many maguro that challenge me to decide between the delicious flavor and aroma, on the one hand, and the beautiful appetite-whetting hues on the other.

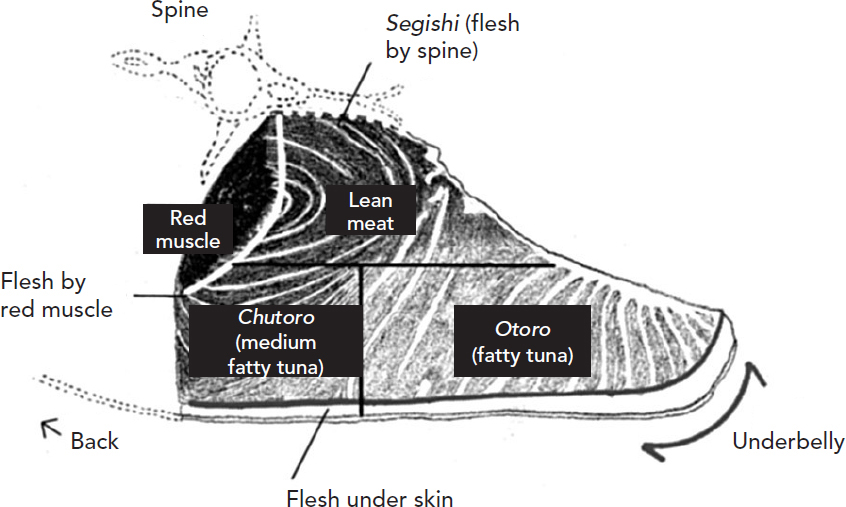

Maguro

parts (harakami profile from tail side)

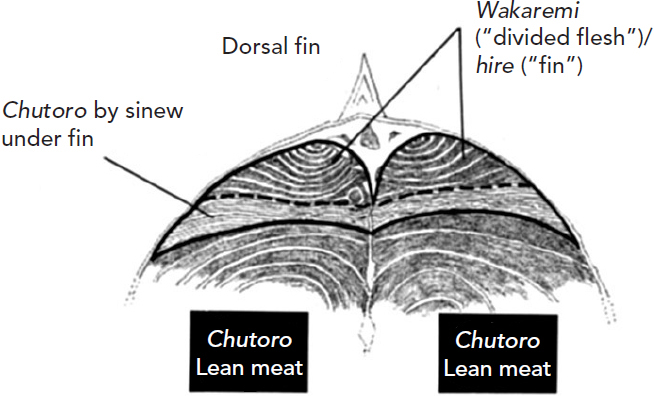

Chutoro by sinew under fin

![]()

What I especially like is a part called the marbled harakami that melts in the mouth like light snow. I always gaze with fascination at the kanoko (traditional Japanese dotted pattern), which looks like premium beef loin. The bellows underbelly is delicious beyond compare. Kamashita (the part under the gills) that has strong sinew is called “the otoro of otoro,” but because it has a strong fishy smell, people’s preferences may be divided.

The most delicious part of chutoro is said to be the hire, the divided flesh right by the dorsal fin. I agree. It has no sinew, and its fat is smooth and light, and there is no greasiness to it. The drawback is the limited quantity. You only get one or two slabs off the back portion, so it’s not something we can have all the time. It’s “the Phantom Chutoro” so to speak.

In fact, there is another gem that surpasses “the Phantom Chutoro.”

When I slice into wakaremi (divided flesh), there is sinew, and in between, there is a tiny amount of flesh. In general, the flesh around bones or sinew is delicious, but even amongst them, this one tastes extraordinary. However, this particular sinew is tough and very difficult to remove.

This is why we make tekka maki (tuna roll) with it—because once it’s diced, you can’t feel the texture of the sinew. But it’s far more delicious to remove the wakaremi and make nigiri with it. I compared them by eating it both ways and came to this conclusion, so I work on it, although it takes a lot of effort.

If there is even a little bit of sinew, you can feel it in your mouth. When I painstakingly try to remove it with a younger chef, even with two of us it takes at least half an hour. So we calculate the time and start to work on it a little bit after 6 p.m., when it’s not so busy, then start to make nigiri with it for the guests who arrive around 7 p.m. This is a part whose color changes drastically, so after an hour or so, it starts to darken.

The parts under the fin that are removed vary in richness of flavor from those of chutoro, which is closer to lean meat, to those of otoro, which is very fatty. So I put them in the refrigerator while dividing the parts, remembering “the one with the stronger flavor is for this guest” and “the one with the lighter flavor is for that guest.” This is a rare item from which I can make only fifteen to sixteen pieces of nigiri. It’s not a neta that I can always serve, so I only make this nigiri if I really want a guest to taste it. It’s a chutoro “specially tailored to regulars,” if you will.

There are other neta that I don’t serve unless you’re a regular.

When I cut and remove saku (slabs) from a fatty, plump maguro, the chutoro saku always end up wide. When I slice them into nigiri-dane to match the size of shari (vinegared rice), I have to cut off the excess. In this case, I thinly slice off the fatty part right by the skin, not the lean meat. If I don’t leave the lean meat, I can’t bring out the gradation of flavors from plain to rich, which is the true pleasure of chutoro.

The part I remove is about two to three centimeters tall and wide and looks like a thick and long square pencil. It has soft fat spread all around, so when you put the neta on your tongue, it melts without any resistance and becomes one with the shari. Only umami remains in the mouth.

So my satisfied regulars who like chutoro always say without exception: “This is the king of chutoro.”

When I share this kind of thing, some people may get angry, saying, “What the heck, you only give special treatment to your regulars.”

That’s not the case. Since I want my guests to enjoy eating nigiri, I can’t just casually serve everything without knowing their preferences.

Because even if I made scarce shimofuri (marbled flesh) or enpitsu (the pencil-shaped cut described previously) nigiri, first-time customers might prefer plain lean meat. Meanwhile, I know for sure that my regulars, who arrive an hour later, get super happy when I serve them these. So it’s human nature to say, I’ll keep it for them. As the master of a sushi restaurant.

Also toro, compared to other attractions such as kohada (gizzard shad), saba (mackerel), and anago (conger eel), is far more expensive, so unless they order it, I can’t just go ahead and make it.

This is why I tell my younger guys, “If you want to eat delicious things, then become a regular.” It’s okay until you find your favorite restaurant, but if you always keep searching for new restaurants—“I tried ten restaurants out of twenty on the restaurant guide, now I’ll go visit the remaining ten”—you’ll never be able to eat a rare neta like chutoro on the sinew under the fin. Then you’re missing out.

The best time to encounter supreme shibi is the middle of autumn. Usually, the last good catch of shibi in Hokkaido or Aomori comes in late November to early December, and in December maguro start to swim south toward the Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Japan off the mainland.

Thus, the main fishing location from January to April is off the coasts of Kyushu and Shikoku. Maguro caught in these areas is transported to Kiikatsuura or Aburatsu (Miyazaki), but I can’t find the kind that I like, and there are days that I’m at my wits’ end. Some people may disagree, but I think it may be because they catch them with haenawa (longline fishing gear).

He doesn’t buy every day but visits the maguro fishmonger every morning. Pictured is an air-transported maguro. His eyes are stern as he tries to evaluate the fatty content and the flesh quality.

Around early autumn, when they start to recover from the spawning season in April to May, all the fat is gone, to the point that it feels cruel. I respectfully avoid these sleek skin-and-bone shibi. Conveniently, chubo (midsized shibi) that start to get caught in fixed nets off the coast of Sanin in late spring taste decent, so for a while, they decorate our neta box. Good-quality ones are also caught in Sado and Ofunato.

August is the worst. The shibi does retain its red coloring, but it’s flavorless like when you chew on konnyaku (yam cake). There is no fat. There is no richness to it. Or, maguro that have turned a dull color due to the heat line up at the market. But I am somewhat at ease since there are many off days during August. And by the time September comes around, the flavor starts to return to shibi, and the best season arrives shortly.

![]()

Lately, there are more orders for lean meat. Occasionally there are orders for zuke (marinated), made after dipping it in nikiri shoyu (a thin and sweet soy sauce glaze). But if they said “two kan (pieces) of zuke” on the spot, they won’t be delicious zuke.

If I lightly score the nigiri-dane, it gets marinated after just five minutes or so. However, I marinate it as a saku (slab) because the inherent aroma of maguro would disappear if the nikiri flavor penetrated all the way. If I receive a reservation—“I’d like to order zuke and will arrive at such and such an hour,” then I observe the lean meat saku’s thickness and quality. And then I count backwards from the guest’s arrival and marinate it for twenty to thirty minutes.

Of course, if it’s delicious lean meat, then I think it’s best to make nigiri with it as is to bring out the inherent aroma of maguro. It’s not necessary to marinate it in nikiri.

After all, it’s a delightful phenomenon that people are starting to prefer lean meat. There were close to no guests who ordered lean meat à la carte seven to eight years ago.

Sixty percent of the back flesh is lean meat, and the other forty percent is chutoro. So chutoro went quickly and the lean meat remained. It used to be, “So … what shall we do with this mountain of lean meat?” We couldn’t possibly have it in the kitchen day and night, day in and day out, just because it was left over.

As a desperate measure, we used to deliver tekka don (tuna bowls) for lunch. We could easily accommodate huge orders—“Please bring fifty bowls right away”—because there was more than a great deal of lean meat. We just had to make the shari.

As someone who went through such trouble, I have to be very deeply grateful for food critics who passionately preached, “The essence of maguro lies in the lean meat. Sushi lovers, eat your lean meat.” They increased the number of people who like lean meat. I sincerely think so.

If you want to know why customers back then ate so much toro, it’s because it wasn’t super expensive like it is now. They say, “People only started to prefer toro after the war and had lean meat in the old days,” but that’s towards the end of the shogunate or the Meiji period; by Taisho and Showa (the entre-guerre years), chutoro was eaten very often.

Kyobashi’s master chef once told me a story. When he was younger, long before World War II, it was challenging for him to slice the bellows belly of otoro because it was sinewy. Yet a beginner could slice chutoro and lean meat without difficulty, so even for delivery nami sushi (the regular-grade assortment), he used chutoro that cut like yokan (sweet jellied azuki-bean paste). When his master found out, he was severely scolded: “You bastard! Why don’t you use the cheap otoro?” Even back then, chutoro was a premium neta for customers who ordered à la carte.

Also, shibi was never a fish that was so expensive that we had to hold it reverently over our heads. According to my memory, in 1955, it cost two to three thousand yen per kanme, or five to eight hundred yen per kilo. Kuruma ebi (prawn) or aka gai (surf clam) was far more expensive. Shibi was a very familiar, common neta. So customers didn’t make a fuss chanting, “Hon maguro, hon maguro.”

On top of that, when summer came, shibi was half-priced. Back then, they used to migrate off Mt. Kinka (at the tip of the Oshika Peninsula in Miyagi Prefecture) to the waters near Choshi, so Edomae-style maguro sushi was from Mt. Kinka and Choshi, but shibi in the summertime was so sleek that you couldn’t eat it. People back then didn’t even bother.

So what the fishermen targeted was the medium-sized chubo. When it grew to a certain point, it had a decent fatty layer. Plus, we were able to get ahold of endless amounts of harakami (the belly portion closest to the gills), which tasted good.

They didn’t have to use the sinewy tail part like we do nowadays; it’s like a joke when I come to think of it.

This is why Kyobashi’s master chef used to say, “Sell maguro at the same price throughout the year. We might not make a profit during winter, but it’s half-priced during the summer. It comes out even over the course of the year.” However, it’s the other way around now. Lately, in the summertime, the price goes up, not down. Coming out even profit-wise is a pipe dream.

It makes sense. They used to treat shibi as “the King of Nigiri” only in Tokyo, so there was a balance between demand and supply.

When I was working as a master-for-hire at a sushi restaurant in Osaka, the fish markets in the Kyoto-Osaka area didn’t sell hon maguro. They had delicious whitefish, so the red meat maguro was considered to be a low-grade fish.

I used to reluctantly fly in harakami from Tsukiji, but it became pricey because of the transportation fee. So there were many customers who didn’t order it, saying, “I don’t like maguro because it’s so expensive.” Now, even in Osaka, maguro has become “the King of Nigiri.”

It’s not only Osaka. All the first-class sushi restaurants around the country compete to make nigiri with hon maguro, so even if fishermen do catch the same amount in seas near Japan, no wonder they don’t have enough.

Moreover, the number of shibi is declining. We only got one in ten years from off Mt. Kinka, once considered the supreme kind by sushi restaurants in Tokyo. And actually that was bad quality. They say perhaps it’s because they’re caught in Hokkaido or the Strait of Tsugaru in the autumn before shibi start to migrate. Or that they don’t get caught in fixed nets in Yoichi (Sea of Japan, Hokkaido) because too many are caught in early summer off the Sanin coast. Or that the currents have changed. There are people who try to come up with various reasons, but there are fewer shibi in the seas around Japan. What’s more, the ones that make your heart skip a beat are getting rarer and rarer.

![]()

The best chubo that I made nigiri with was from Oma on the Strait of Tsugaru and was caught by pole-and-line fishing in 1993. It had a smooth, unforgettable deliciousness with a subtle aroma and soft sweetness that’s different from large shibi.

The oma’s popularity is increasing drastically lately. Before the great earthquake that hit southwest offshore Hokkaido, shibi from Teuri Island (in the Sea of Japan) had a good reputation, but we can no longer seem to catch any, maybe because the course for the fish at the bottom of the sea has changed. Now if it’s called “oma,” then regardless of its size, the bid price hikes up.

That’s because the fishermen in Oma use poles and lines to catch maguro that have feasted on squid off the coast of Hokkaido and gained plenty of fat and are now prowling the strait for more food. After landing one, the gents immediately haul it to port, so they get paid well. This is why the freshness, fattiness, and coloring is good, but that forty-kilo chubo was the best by far.

There is a clear difference in taste between ipponzuri (pole-and-line fishing) and the predominant haenawa (longline) method of catching maguro. I compared them with my palate and came to this conclusion.

That’s to say, those maguro swimming in shallow waters that aren’t too big are the ones caught by ipponzuri (pole-and-line fishing), hikinawa (seine fishing), makiami (round-haul netting), and teichiami (fixed-net fishing). I prefer smallish maguro that weigh under 150 kilos that are landed by pole-and-line fishing. It’s not too fatty and has a nice aroma and tastes smooth. It will be impeccable if it’s from Hokkaido or Aomori in season. The fishermen around that area know what to do with their catch.

After the red muscle is removed, a maguro block is wrapped in water-absorbent paper and again in another sheet of paper, placed in a plastic bag, and buried in a bed of crushed ice. You wait for the flesh to mature while it rests this way.

On the other hand, haenawa (longline fishing) sets hooks to target big ocean maguro. This is why it tends to have too much fat and tastes greasy.

I have other reasons why I don’t like ’nawa.

Maguro doesn’t breathe by opening and closing its gills. Like katsuo (bonito), it swims with its mouth half open and forces seawater into its gills to take in oxygen. It can’t survive unless it keeps swimming.

So when it gets caught by a hook, it dies after struggling and suffering. I will omit a detailed explanation, but when this happens, its body temperature rises drastically and apparently burns its own flesh.

With haenawa, they set a long line over a 100-to-150-kilometer-wide area of the sea, so from the time they set the first hook to the last hook, we’re talking about over twenty hours. There is no way maguro caught on an early hook can remain in good condition.

When I cut out a saku (slab), the coloring of the lean meat looks better than expected. It looks good, but when I try it, it’s slick and tastes too plain, as expected. The only fat is oddly greasy. There is no umami whatsoever to the point that I begin to wonder why.

When they haul in the ’nawa, if the last hooks yielded a catch then it’s been only four to five hours, and the freshness is fine then, but that’s a pretty low percentage. In any case, I think there are many bad-quality maguro caught by ’nawa.

However, it’s true that in this day and age we don’t have the luxury to prefer “fishing” over “longlines.” They can’t catch any in the seas near Japan, so it’s eye-poppingly expensive.

Everyone says, “There is no question that it tastes good, but it’s way too expensive.” I agree, but because of demand and supply, the price continues to rise.

![]()

The highest price reached in Tsukiji Market was the first bid of the year in 1996: 9,040,000 yen for one maguro. It was for a 238-kilo one from off the coast of Kishu. Back then, for two weeks including the New Year’s off days, we couldn’t get ahold of kinkai hon maguro at all, so I was half ready to concede on January 5th, the first day of work—“I have no choice but to go for frozen.”

On a day like that, one shibi came into the market, so there was a big commotion. Two brokers who specialize in premium maguro held their ground and kept hiking up the bids.

Their top customers aren’t high-end traditional restaurants, but a small number of sushi restaurants that can’t open without kinkai hon maguro. They don’t deal just with Sukiyabashi Jiro. There are a few chefs. This is why the brokers come on strong.

In any case, sushi restaurants with whom they have long relationships desperately want it, so neither side is willing to lose. And this is why in no time, the price exceeds 9,000,000 yen.

However, even the maguro broker who wins isn’t happy with the high price.

Leading brokers have several stores, so no matter how big the shibi is, they can easily sell it. It’s easy, but to put aside the math, the minimum unit for sushi restaurants will be 500,000 yen. No matter which block you buy, from harakami, which includes otoro, to the tail part that’s sinewy, it costs 500,000 yen.

The broker divides the fish, the buyers draw lots, and they’re paired up, but no matter how desperate, no sushi chef buys such astronomically expensive shibi, especially the sinewy tail part, with a smile on his face.

So the broker who emerges victorious will have to sell at a discount. He’s ready to forgo profit as he bids up the price. “I don’t want to lose to my rival.” “I want to make my sushi restaurant clients happy.” It’s sheer professional pride. He’s disregarding profit and loss from the outset.

It’s not just brokers—all those concerned are crying. To have caught only one in two weeks means most of the tens and hundreds of maguro fishing boats that set sail on the winter ocean came back empty-handed. The captains of the boats buy expensive fuel and live bait, then pay their fishermen, and then they only caught one fish.

To begin with, that maguro wasn’t worth the “new record” price at all. There was no shibi during those two weeks. It was extremely scarce. That was the only reason the cost shot up to 9,040,000 yen.

Because if it’s that big, then the sinew in the belly is too strong to chew off. And that sinew takes up a third of the otoro portion. Once all the sinew is removed, the neta’s price climbs to 5,000 yen to 6,000 yen per piece. Peel the skin off. Debone it. Remove the red muscle. If the lean meat is too sleek and can’t be used, then things get even bleaker. If we were to charge the market price, it’d be 10,000 yen per nigiri. For a pair, 20,000 yen.

We can’t charge that kind of price for mere nigiri. Hence, no matter how high the cost, I only charge 2,500 yen, as usual. I’m ready for a big loss. The master of a sushi restaurant has his pride, too.

“Do you have otoro?”

“Well, I couldn’t afford it because it was stupidly expensive. I’m sorry, but we are out of it today.”

There is no way I can say this as someone who hawks his kinkai hon maguro.

“I see, I see. But such-and-such was making nigiri with it. Hahahaha.”

At 7 a.m., after stocking the restaurant, he attaches an 80-kg load onto the carrier and heads back. He has continued this every day for over thirty years.

If I were mockingly laughed at like that, where would it leave me?

At that time, what we won from drawing lots was the middle of the back portion. The part called “se no naka” doesn’t include otoro. So I wonder how much we lost. A huge amount, I’m sure.

But we already knew that. “Even if we sold all of it, it’d add up to only this much in revenue.” A ballpark estimate. Times like that, you can’t do detailed accounting. It just feels stupid. I am, after all, a business manager, and it’s not that I don’t think about profit. But there is nothing you can do when scarce shibi fetches a crazy price. I decided not to do the math.

If you estimate the ratios of otoro, chutoro, and lean meat for a saku (slab), tally how many saku each comes out to, and consider that the selling price of lean meat is a fifth of otoro … you can calculate the cost that way. You can, but if that’s what’s on your mind, the slices keep getting thinner and the shari keeps getting bigger, and you can’t make delicious nigiri.

I don’t like to talk about prices. Once we who’re making the nigiri start to worry about that, we end up getting all stingy.

Let’s say one maguro saku normally costs 10,000 yen. But then you learn, “It costs 40,000 yen today.”

“Okay, it costs four times more. Let me make the neta thinner and make two or three pieces extra.”

It could get that way. Of course, there’s a huge difference between 10,000 yen and 40,000 yen. If you sliced four extra pieces out of a saku and sold them for 2,000 yen apiece, you’d make an extra 8,000 yen. Then, even if the cost is four times higher, the margin of error shrinks.

If you keep calculating that way, then of course the maguro slices get thinner.

When I make nigiri with toro, I prioritize the balance between neta and shari and adjust the thickness of the slice. This is because I’m considering how to make the best-tasting nigiri. If I make nigiri with otoro of the same thickness as chutoro, then it might be too rich. I might slice it thinner for that reason.

That’s why when a customer sticks around forever and blithely orders only the maguro, shinko (young gizzard shad), kuruma ebi (prawn), and uni (sea urchin) that I’m serving at my “bleeding price,” to be honest, I’m fuming at heart. Even now that I’m over seventy.

“Bastard! You have no idea how I feel.”

I’m no spring chicken, but I still run a business.

But don’t be surprised by 9,040,000 yen. There is always something that’s more expensive.

That shibi from off Kishu cost 39,140 yen per kilo. That’s surely expensive, but it’s actually not startling.

The highest price per kilo at Tsukiji was 46,350 yen on November 20, 1996. After removing the skin, bones, and red muscle tissue and simply calculating the yield rate at sixty percent, you reach the unreasonable cost-price of 7,725 yen per 100 grams, but I’m sure this record will be renewed continuously.

![]()

There is one more troubling issue. Some people say, “Maguro from the seas near Japan is delicious” and “The imported ones taste bad.” This “kinkai hon maguro supremacy” is rampant.

“Why do they praise kinkai (nearby seas) so much, and in contrast, regard imported ones, especially frozen maguro, as inferior?”

Even I, who insist on kinkai hon maguro, feel that this deep-rooted trend, prevalent among customers and also sushi craftsmen, is something we could almost call a creed. This belief that “If it’s not kinkai, then it’s not hon maguro (blue fin tuna) at all” came about gradually, maybe led on by sushi restaurants or the maguro brokers. It’s really a strange story.

What I mean is, when we say “imported,” for instance, the ones that land in Los Angeles are the exact same authentic hon maguro that were swimming in the seas near Japan. It’s just that it swam across the Pacific Ocean from Japan to Los Angeles and got caught there.

As soon as the same maguro is labeled as being “from off the coast of Los Angeles,” people say, “Heck, it’s imported,” so it’s troubling. This is what I tell them: In the summertime, when the ones around Japan are skinny after the spawning season, the ones over there are fat and taste good.

Even people who understand this in their heads might be thinking, “LA? No way,” deep down. As sushi chefs, then, we have no choice but to desperately search for kinkai.

This is why the fate of kinkai hon maguro as a natural resource is a severe and dire issue for the master of a sushi restaurant.

In the past, when the brokers had low stock, they offered kinkai hon maguro that had been frozen in season. However, lately they sell out while they are fresh, leaving none for the warehouse. So almost all the frozen maguro are from overseas.

Even if they’ve been frozen, Pacific maguro and minami maguro (southern bluefin tuna) are far superior to the domestic mebachi (bigeye tuna) or kihada (yellowfin tuna).

People have said for a long time, “Nyubai mebachi (bigeye tuna in mid-June) is in season so it’s delicious.” But I don’t agree with that. I actually ate them to compare them. Mebachi doesn’t have strong fat at all, even in the bellows belly of otoro—it has grease, but not richness of flavor. It’s like drinking bland hot water instead of tea. Only a dry and unsatisfied feel remains in the mouth. Just like with boiled barley rice.

Kihada is a fish that’s popular in Kansai. But as a nigiri neta, it’s like “reheated porridge” and not on the same level as hon maguro, which is like “freshly cooked rice.” Whether it’s fresh or frozen, from the Pacific Ocean or the Atlantic Ocean, or even the Mediterranean, no matter where it was landed, hon maguro is still “the King of Sushi.”

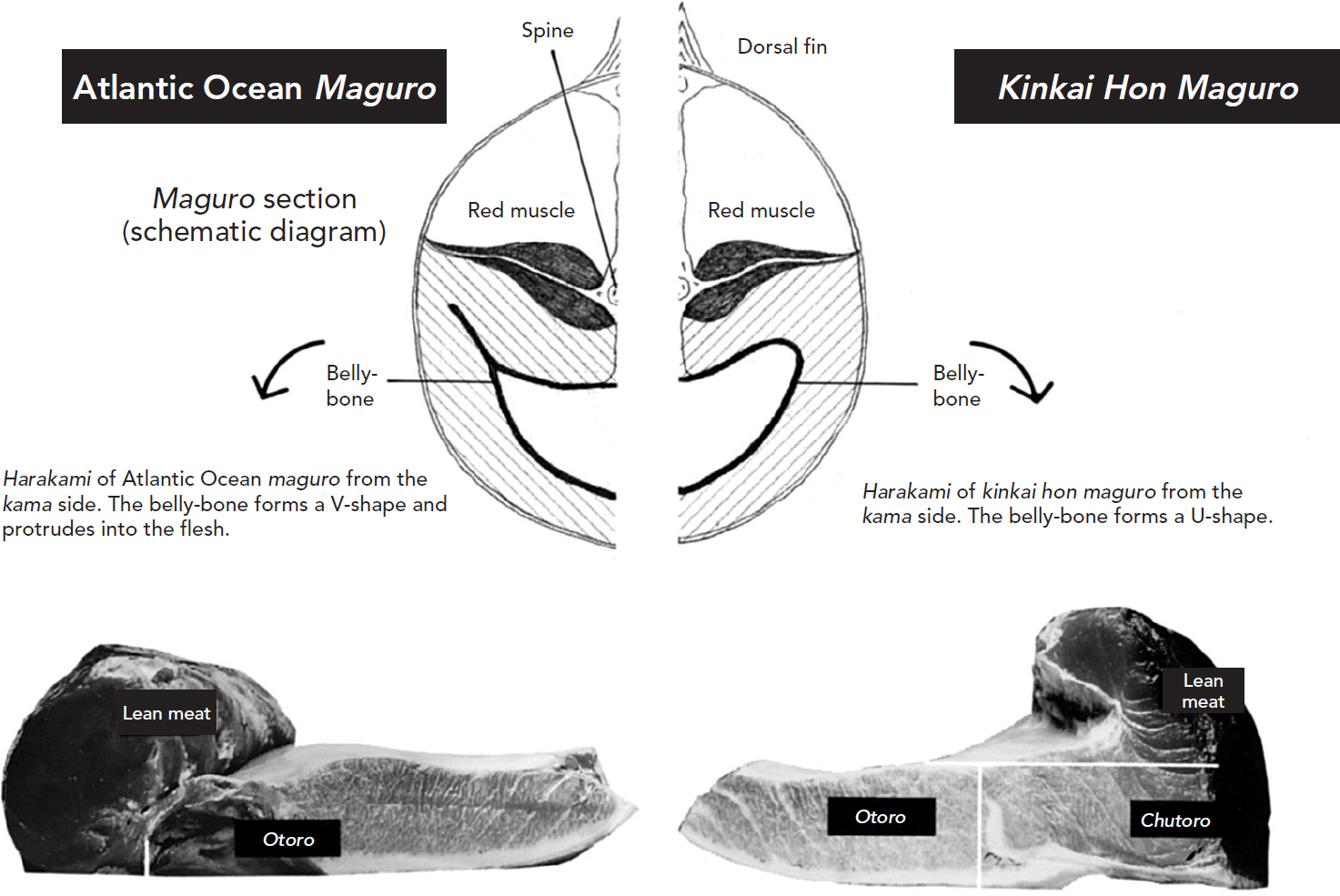

Behold, the difference between kinkai hon maguro and maguro from the Atlantic Ocean!

Both kinkai hon maguro and Atlantic Ocean maguro (commonly known as jumbo maguro) are “bluefin tunas” and look the same to the common eye. However, when you examine their sections, you can clearly see the difference. The schematic diagram above shows the section behind the gills, and when you compare them, the belly-bone of Atlantic Ocean maguro forms a V-shape and protrudes at a sharp angle deep into the flesh. In other words, the belly-bone of Atlantic Ocean maguro divides the toro and lean meat, and you can’t obtain any chutoro, with its contrast of fat. You can see this from the cross sections of harakami. Chutoro is a part unique to kinkai hon maguro. The belly-bones of Mediterranean maguro and Indian maguro protrude in the same way as the Atlantic Ocean variety’s.

For instance, in the winter when good-quality kinkai shibi is scarce, if I make nigiri with defrosted imported maguro, well, I wonder how many people have the discerning palate to call it and say, “This isn’t kinkai hon maguro.”

Even if it’s frozen, fatty in-season maguro tastes far better than kinkai shibi that’s out of season and skinny. It doesn’t even have to be the ones from Los Angeles that swam from Japan or the jumbo raw ones that fly in from New York.

Even though they are both hon maguro, kinkai hon maguro and foreign maguro are different types. In particular, the Atlantic hon maguro is different in its bone structure.

The kinkai has a sleek, elongated trunk. The ones from the Atlantic Ocean are pudgy. And whether it’s from Oma or Los Angeles, once its head is cut off, you see a continuous harakami (upper belly portion) that includes chutoro and shimofuri (marbled flesh)—but not so with the Atlantic variety. The belly-bone in the harakami sticks out into the lean meat, so the chutoro that exists in kinkai hon maguro isn’t there. All of a sudden, it’s otoro.

Of course, they have different flavors. It’s almost as different as vegetable oil and lard. You can tell if you actually eat and compare them. The fat is strong in kinkai hon maguro, but it tastes smooth. It’s not greasy, and it has a nice aftertaste.

However, the fat of hon maguro from the Atlantic Ocean and minami maguro (southern bluefin tuna) tastes very rich, like lard. It lacks the refreshing, mouth-cleansing aroma. The flesh is hard. The sinew is tough.

It depends on the maguro’s size, but if you let kinkai rest for a while, the sinew disappears. But with the other ones, no matter how long you let it rest, the sinew remains.

So if it’s too greasy, slice it thinner. If it’s too tough, remove the sinew. If not, carve out the flesh between the sinews. That’s how you could make nigiri with it, even though there’s more waste for sure that way.

Customers who are used to eating kinkai hon maguro that’s like “vegetable oil” might think, “What? This is a bit too greasy” in the beginning. But once they get used to it, they won’t mind the richness of “lard.” You can take away the discomfort by going the extra mile with your craft.

I think so.

After all, shibi is “the King of Sushi.” Without its appetite-stimulating color, our neta box will look dumb.

“When kinkai hon maguro is gone for good, Jiro will close,” some regulars worry in earnest. But these days, this is how I answer them: “Nope—like I’d take down my Sukiyabashi Jiro sign so soon.”

How to turn “lard” into smooth “vegetable oil.”

I’ll have you know that I’ve started studying extra hard about imported maguro.