I. INTRODUCTION

Were Hitchcock’s films greeted with enthusiasm when they were first seen in Spain and Latin America? Was he an instant sensation? Well, no. Hitchcock’s relationship to the Spanish-speaking world evolved over the course of the six decades of his long career; his visits to Spain bracketed two important stages of that career. In the early 1920s when he was first setting out he scouted Spanish locations for the silent film The Spanish Jade for Famous Players-Lasky. Later in the 1950s at the height of his creative output he launched Vertigo and North by Northwest in San Sebastián, site of the premier film festival of the Spanish-speaking world.1 There in August 1958 the press compared Hitchcock to Santa Claus. Despite his almost universal name recognition, the reception history of Hitchcock’s films is neither well studied nor uniform worldwide. The sequence and circumstances under which his films opened in Spain reveal significant differences from the conditions of their releases elsewhere in the world. For instance, certain films – Lifeboat (1944) and Psycho (1960) – were substantially cut in Spain. Others – Rebecca (1940) and Spellbound (1945) – immediately impacted on cultural politics and served as rallying cries for a new type of cinematic aesthetics. The ‘Latin Hitchcocks’ of the 1980s and 1990s, who are the subject of subsequent chapters, arose from this specific historical and cultural terrain. We will explore whether, and if so how, humour, aesthetic innovation and a moral tone reflective of Hitchcock’s Catholic background – elements that became fundamental to these post-Franco directors – factored into the initial public response in Spain.

To survey the reception of all of Hitchcock’s 53 films and TV programmes in Spain and Latin America is a topic worthy of one or more doctoral dissertations, or at least a book-length guide similar to Jane E. Sloan’s Alfred Hitchcock: The Definitive Filmography (1993). A comprehensive answer lies beyond the scope of this chapter. Hence, as a first step to narrowing our focus, we will examine the range of Spanish or Latin American locations or motifs in his films. Whenever Hitchcock represented the Latin world throughout his career he laid the foundation for a unique dialogue with the viewing public. In effect the selection of a Latin location privileged the film’s reception history for that area. As a second step, in order to highlight and analyse the impressions Hitchcock’s films first created, we will turn to Spain as a case study, since all the directors subsequently studied in this book have at very least intervened in the Spanish market at one time, if not worked out of that country as their primary base of operations. This approach, moreover, will allow for an overview of important sources for reception studies in Spain for the period of Hitchcock’s active career.

II. LATIN LOCATION, LOCATION2

Alfred Hitchcock did work in Spain in his early years when he was getting into the film business and climbing the ladder at the British Famous Players-Lasky studio from errand boy, then significantly to art director, then director. As Patrick McGilligan notes in his biography Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, Hitchcock’s third project as an art director was the silent film The Spanish Jade (directed by John S. Robertson) in 1921 – Hitch was then 22 – for which ‘cast and crew traveled to Spain’. McGilligan comments that ‘overseas travel became routine in the Islington years’ (2003: 51). More important than the location, however, is Hitchcock’s career path, as McGilligan argues: ‘In all of film history only a small percentage of directors have come from the ranks of production design. This foothold gave Hitchcock a distinct advantage when thinking in pictures. From the start, the “right look” – for people and places – was integral to his vision’ (ibid.).

He knew, for example, when in 1956 he took on the project to adapt and modernise the French novel D’entre les morts for Vertigo, that San Francisco was the perfect location. He thought the city, which he had loved since he first came to California, sufficiently European in character. Part of this European background was its Spanish heritage. The picturesque Mission Dolores was chosen as a location from the earliest stages of the project. The climatic scenes of the film would take place in the most Spanish of sites, Mission San Juan Bautista, south of San Francisco. McGilligan, incidentally, confuses the two Spanish missions in his biography of Hitchcock, saying ‘Hitchcock had picked the Mission Dolores for its picturesque quality, even though the church didn’t have a bell tower’ (2003: 541). Dolores includes a more baroque church that indeed has a bell tower.3 According to Dan Aulier in Vertigo: The Making of a Hitchcock Classic (1998), Hitchcock’s longtime Director of Photography Robert Burks did not want a site that was ‘too obviously pretty’ and Hitchcock himself ‘wanted a location that looked abandoned’ (1998: 64). Since this mission’s church no longer had a bell tower when it was chosen, an enormous set, the largest single expense in the film’s budget, was created at the studio. Hence, for Vertigo ‘Spanish’ meant an austere site of history, religion and judgement. In an interview in July 1958, published in Spanish translation in El cine británico de Alfred Hitchcock (The British Films of Alfred Hitchcock, 1974), Carlos Fernández Cuenca, the Director of that year’s San Sebastián Film Festival in which Vertigo was entered, asked Hitchcock whether he had been concerned with religious problems or themes in any films other than I Confess (1951) and The Wrong Man (1957). Hitchcock immediately recalled that he and Burks in fact had counted Catholic churches in fifteen of his films. Hitchcock called their presence, including that in Vertigo, ‘un fruto claro del subconsciente, un deseo de amparar los conflictos humanos bajo la sombra de los símbolos de la religión’ (‘an obvious product of the subconscious, a desire to shelter human conflicts under the shadow of symbols of religion’) (1974: 36). Furthermore Hitchcock added: ‘No hago cine concreta y deliberadamente católico, pero me parece que nadie dudará de que mis películas están hechas por un católico’ (‘I don’t make Catholic cinema concretely and deliberately, but it seems to me that no one will doubt that my movies are made by a Catholic’) (ibid.).

Hitchcock was almost forced to address the Spanish Civil War when he was making Foreign Correspondent (1940), but he never quite had to. In the film a green American press correspondent is sent to Europe to cover the war in August 1939. The producer Walter Wanger believed film could ‘change the course of human events’ (Spoto 1999: 222), calling motion pictures, in his own words, ‘almost as important as the State Department’ (ibid.). Hence, Wanger’s vision for Foreign Correspondent was both idealistic and highly topical. He insisted on rewrites to incorporate the most up-to-date information on the war, including at one stage references to the Spanish Civil War, but events followed in fast succession so that the specific war references with which the film ends are to the bombing of London, not Guernica. Overall Hitchcock tried to avoid politics in his films, officially at least because it was bad box office. In the case of Foreign Correspondent he merely humoured his producer, did not do the suggested retakes and kept the film as general as he could. As Foreign Correspondent turned out to be ‘not a piece of anti-Nazi, anti-war propaganda’, as Wanger had hoped, but ‘a picaresque story, a romantic melodrama with considerable comic tone’ (Spoto 1999: 227), it has stood the test of time better for it. The Spanish may have prevailed in this gesture to the origins of the picaresque. Donald Spoto describes the shift to the generic well: ‘The finished film (except for the last minute) has about as much to do with the politics of the war as Tosca has to do with Napoleon’s campaign in Italy: the historical setting provides a distant background for a personal story of adventure, love and betrayal’ (1999: 230).

Although Notorious (1946) was filmed almost entirely on studio sets in Los Angeles, with the notable exception of the projection shots of Rio de Janeiro taken from an aeroplane, it spans the Americas in its Latin locations. This sweep to crisscross the globe was integral to Hitchcock’s new business plan. Hitchcock conceived the film as the first project of his dream company ‘Transatlantic Pictures’, named to suggest the collaboration between Europe and America. According to McGilligan, the story of Transatlantic Pictures is ‘a chapter in Hitchcock’s life [that] has been inadequately reported, and misunderstood’ (2003: 365). He emphasises that the ‘prescient’ choice of locales – Miami and South America – for Notorious was entirely Hitchcock’s decision, one that aimed to attract a global audience with important world issues. Hitch at that time, moreover, was genuinely concerned about world security, including the future of Nazis and Nazi sympathisers. At the end of 1944 he had pitched a short film called Watchtower over Tomorrow about threats to peace to the State Department. Its imaginative scenario ‘alarmed US officials’.4 Some precedent already existed for Hitchcock thinking Latin when it came to complex war scenarios. His first Latin character had been ‘the Mexican’, an Armenian professional assassin who tries to pass as a Mexican general, in Secret Agent (1936), a World War I spy film.5

This political and economic back story shows how far Notorious moved away from the original New York City locale of the serial called ‘The Song of the Dragon’ upon which the film was based. Nonetheless although the new Latin locations implied a link to real international intrigue and current events, if not futuristic predictions, the drama that unfolded in Hitchcock’s film, in Miami and Rio, recalled time-worn Latin stereotypes of wild parties and ill-gotten wealth.

Notorious opens at a courtroom in Miami. A distraught Alicia Huberman (Ingrid Bergman) witnesses the reading of the final guilty verdict at her father’s trial, then rushes out. Later at a party in her apartment she drowns her sorrows in booze and establishes her image as a Miami party girl. Her sparkly beach stripe shirt and bare midriff, which Devlin (Cary Grant) later humorously covers with a scarf when they leave for a drive, enhance the look. The Latin theme of the party is further underscored when a footloose yachtsman, played by the real life intelligence agent Charles Mendl, tries to get her to sail with him to Cuba. Shortly after the farewell party she leaves town to fly down to Rio as an undercover spy on the trail of the film’s MacGuffin, uranium stored in a wine bottle, owned by the fascist-in-exile, Alexander Sebastian (Claude Rains), she is sent to seduce. The party scene at Sebastian’s mansion in Rio today ranks as one of Hitchcock’s most famous sequences for his invention of a massive crane shot that sweeps down to show Alicia’s hand holding a key. In subsequent chapters on their careers we will explore the effect these Latin party scenes in Notorious had on Guillermo del Toro’s Cronos (1993) and on Juan José Campanella’s Love Walked In (1997).

A humorous rebuke to her Miami party girl image: Devlin minimally covers Alicia’s bare midriff with a scarf before they go out for a drive in Notorious.

Nonetheless, the reception of Notorious has more often foregrounded mise-en-scène in all its aspects – set and wardrobe especially – than cinematographic innovation, or even narrative. At the opening of Encadenados (Notorious) in Madrid in 1948, for example, Donald, the reviewer for the newspaper ABC, did not think much of the film’s emotional impact, writing ‘that plot is poorly realised in the sets and situations that they provoke. Despite the intensity that they want to convey, they don’t manage to excite’ (1 October 1948: 15). Indeed he found the effect of the dialogue rather comic – ‘what the characters say causes unexpected effects that become comical’ (1948: 16). However, the film’s glamour, the essence of the party scene, did impress him: ‘On the other hand one could say that Hitchcock has limited himself this time to achieving a vivid series of fashion plates, for the most part worthy of appearing in a luxurious high-end magazine whose pages show exquisite feminine clothes for every hour of the day and homes and mansions of the rich’ (ibid.). To convey the essence of Ingrid Bergman’s image, the illustrator even included her her suit and fedora hat in the caricature that accompanied Donald’s review. That image contrasted vividly with the Bergman caricature the same artist did for Spellbound the previous year that shows her ample wavy hair and come-hither expression.

Precisely because they represented fashion plates, the iconic images of their times, as Donald noted, Hitchcock’s films enjoy a prominent place today in Madrid’s new Museo del Traje (Costume Museum), which opened in 2004. In the galleries, which are organised by decades, large video screens play film clips of several Hitchcock films, which include one featuring Bergman in Notorious. Another film of love and betrayal like Notorious, Topaz (1969), based on Leon Uris’s novel of the same title, is the only other Hitchcock film with a Latin American location. Focused on espionage during the Cuban missile crisis, Topaz shares a distinctly political scenario with some of his other films, such as Notorious and Torn Curtain (1961). The Cuban scenes, which McGilligan considers ‘among the best in the film’ (2003: 689), are both the most tragic and the most visually inspiring. I will discuss the impact Topaz had on Almodóvar’s Flor de mi secreto (Flower of My Secret, 1995) in the chapter ‘Pedro Almodóvar’s Criminal Side’.

Conceivably Hitchcock’s most direct contact with a Spanish location was his difficult, and ultimately unhappy, collaboration with Salvador Dalí’s imagination for the dream sequence of Spellbound. In fact the Spanish government officially recognised the Spanish connection to this film when King Juan Carlos and Queen Sofía opened the exhibition of the original backdrop paintings Dalí made for the sequence in the Dalí Theater-Museum in Figueres, Spain. In 2004, in anticipation of the 2005 Dalí centenary, the main image of the San Sebastián Film Festival, was a backdrop of huge eyes reminiscent of Dalí’s Spellbound sequence. Significantly, on its main poster San Sebastián chose to feature a photo of Hitchcock touting his career total of 53 films to mark its own 53rd edition in 2005.

Although Hitchcock made only three films (Notorious, Vertigo, Topaz), or stretching it five (with Foreign Correspondent and Spellbound), with a Spanish or Latin American location, a great majority of his career total of 53 films were shown in Spain and Latin America. In Spain they were almost always dubbed into Spanish. On the other hand, in Latin America they were more frequently shown with Spanish subtitles in their initial release. Chapter five, ‘Latin American Openings: The Reception History of Hitchcock’s Films for Mexico City’, will address the transition from subtitling to dubbing as we explore in detail how Hitchcock’s films were first received in Mexico. Either way, dubbed or subtitled, Hitchcock’s films became an integral part of the Spanish and Latin American culture and what we have termed in light of the cultural imaginary of the region, Latin Hitchcock.

III. HITCHCOCK IN SPANISH ONLY: A VIEW FROM THE ARCHIVES OF RELEASE DATES AND DUBBING

In order to construct a history of the reception of Hitchcock’s films in Spain it is necessary to know if and when each of his films debuted there. This information is not easily found. The traces of Hitchcock’s silent period, or even of his early British sound films in contemporaneous Spanish newspapers, for example, are faint and infrequent. One important source from that period for some of this information, especially from the 1930s onwards, is Carlos Fernández Cuenca’s card catalogue of individual films that had Madrid openings. As Head of the National Department of Cinematography, Fernández Cuenca (1904–1977) founded the Spanish National Film Archives, where this catalogue is stored, and served as the Archives’ first Director from 1953 to 1970. Fernández Cuenca was a key cultural authority, even a political kingpin, for his times. He was a member of Movimiento and SEU, as well as head of the Sindicato Nacional del Espectáculo (National Entertainment Union). He was Director of the Escuela Oficial de Cine (Official Cinema School) and of the San Sebastián Film Festival. He served on the juries of the Venice Film Festival in 1954 and 1958. Besides six film books, stories and screenplays, he regularly wrote for the magazines La Época, La Voz, El Nacional and Marca. He was film critic for the newspaper Ya and editor of the journal Primer Plano.

The last book Fernández Cuenca wrote was a small tome, El cine británico de Alfred Hitchcock which culminated a career of watching Hitchcock in Spain. He even appended a previously unpublished personal interview he had with Hitchcock in San Sebastián in 1958. For him Spanish critics lagged behind their American and French counterparts in Hitchcock criticism. Coming from the pen of someone who always meticulously noted where and when a film debuted – finally, he was a librarian – the details of reception history frame Fernández Cuenca’s text. They were integral to his very being as a critic. For instance, he explains that a retrospective of American films at the French Cinémathèque in 1956 inspired the French reassessment of Hitchcock’s place in world cinema. With customary detail Fernández Cuenca even tells the reader the times of the multiple daily sessions of the extended series that left French spectators ‘day after day sacrificing their dinner hour’ (1974: 13). He concludes the introduction to El cine británico… again referring to Hitchcock’s reception history:

He who has written it knows almost all the films in question: at their precise hour he saw the ones which were shown in our country and he wrote about the majority of them in various Madrid newspapers; he has been able to screen others in London and in Paris, thanks to the generosity of the British Film Institute and the French Cinémathèque, taking pertinent notes during those screenings which I am now revising. It has seemed useful to me to point out in each case the criticism that the movies merited from contemporaneous critics, from those afterwards, and from Alfred Hitchcock himself. (1974: 14)

Fernández Cuenca writes about himself in the third person with Biblical certainty. Given his pledge to tell the whole Truth, the gaps in his appended Hitchcock filmography about screenings in Spain for certain early Hitchcock films leave in doubt whether all these films were even shown there. Unlike other Spanish authors of books on Hitchcock, who aimed at a global audience, and a universal interpretation of Hitchcock’s films such as Diego Montes in La huella de Vértigo (The Trace of Vertigo, 2004), an analysis that references art history, Fernández Cuenca had a keen sense of interpreting essentially for a national audience and acknowledging the particular Spanish reception of Hitchcock.

Most distinctively Fernández Cuenca explains, after quoting Truffaut on the subject, what the English word ‘suspense’ means in Spanish. As befits someone educated in philology, who would expect the same background from his audience, he first evokes classical rhetorical analysis:

The good technique of ‘suspense’, the way that Hitchcock uses it, consists in that that feeling is conveyed from the characters who feel it to the spectators. In classical treatises of eloquence one speaks of ‘attentional suspension’ as a device that by drawing out paragraphs and even elongating the syllables of each word creates anticipation in the audience given the absolute certainty that they must wait. In rhetoric there is a figure called ‘suspension’ that consists in postponing, in order to heighten the interest of the listener or the reader, the statement of the concept that a sentence is heading towards or which will wrap it up when it is said or written. ‘Suspense’ in Spanish has the meanings of ‘surprised’ or ‘perplexed’; this last one can fittingly describe the effect that certain Hitchcock scenes have on our mind. But any Anglo-Saxon dictionary will tell us that the most exact equivalents of the word ‘suspense’ are ‘uncertainty’ and ‘anxiety’. (1974: 11–12)

Fernández Cuenca explains for his Spanish audience that the word ‘suspense’, used to refer to the ‘master of suspense’, really doesn’t have an exact translation in Spanish. Ads and reviews of Hitchcock repeatedly used the English, most often in quotes.

The following chart is based on Fernández Cuenca’s data, a composite of his catalogue notes and the filmography in El cine británico de Alfred Hitchcock. It compares the opening date of Hitchcock’s films in Madrid, and the running time of the Spanish dubbed copy, to the information about the original release of each film as noted in Sloan’s Alfred Hitchcock: The Definitive Filmography.

Hitchcock’s films were presented in Spanish. The intertitles of his silent films were translated. As Spanish law mandated from the 1930s onwards, all of Hitchcock’s sound films – that is, beginning with La muchacha de Londres (Blackmail, 1931), were dubbed into Spanish for their initial exhibition. ‘Versión doblada’ is almost always noted on Fernández Cuenca’s index cards although he does not make these notations in his book. The dubbing process alone explains the delay of approximately a year from the film’s initial release to its opening in Madrid. By the 1960s the gap was down to about six months. Though the table based on Fernández Cuenca’s data only represents 22 of Hitchcock’s 53 films, it does show that his films were shown with great regularity in Spain. All of the above films opened at major movie theatres in Madrid, most often at the Palacio de la Música, but also at the Avenida, Roxy B, Gran Vía, Lope de Vega, Carlos III and Callao. The British films opened most often at the Avenida and later at the Palacio de la Música, but also at the Princesa, Ideal, Palacio de la Prensa, Figaro and Cinema Palace. Comparing the original running times in the chart based on Cuenca’s catalog shows that Lifeboat and Psycho were cut or censored substantially for their Spanish showings.

| Spanish Title |

English Title |

Madrid ‘Estreno’ (Opening) |

Original Release Date |

Spanish Running Time |

Original Running Time |

| De mujer a mujer |

Woman to Woman |

18 Nov. 1927 |

1923 |

2,274 metres |

|

| Champagne |

Champagne |

22 April 1929 |

August 1928 |

2,434 metres |

104 min. |

| El enemigo de las rubias |

The Lodger |

1 March 1930 |

Sept. 1926 |

2,336 metres |

100 min. |

| El Ring |

The Ring |

21 July 1930 |

Oct. 1927 |

2,553 metres |

110 min. |

| La muchacha de Londres |

Blackmail |

5 March 1931 |

June 1929 |

85 min. |

80 min. |

| Valses de Viena |

Waltzes from Vienna |

15 July 1935 |

1933 |

80 min. |

80 min. |

| El hombre que sabía demasiado |

The Man Who Knew Too Much |

18 Nov. 1935 |

Dec. 1934 |

84 min. |

85 min. |

| Treinta y nueve escalones |

The Thirty-Nine Steps |

6 Jan. 1936 |

Sept. 1935 |

81 min. |

81 min. |

| Agente secreto |

Secret Agent |

27 Nov. 1939 |

Jan. 1936 |

83 min. |

83 min. |

| Posada Jamaica |

Jamaica Inn |

24 Feb. 1941 |

May 1939 |

99 min. |

100 min. |

| Alarma en el expreso |

The Lady Vanishes |

9 March 1942 |

Oct. 1938 |

97 min. |

97 min. |

| Rebeca |

Rebecca |

10 Dec. 1942 |

March 1940 |

130 min. |

130 min. |

| Matrimonio original |

Mr. and Mrs. Smith |

17 Sept. 1943 |

Jan. 1941 |

95 min. |

95 min. |

| Sospecha |

Suspicion |

10 Dec. 1943 |

Sept. 1941 |

99 min. |

100 min. |

| Inocencia y juventud |

Young and Innocent |

10 July 1944 |

Nov. 1937 |

80 min. |

80 min. |

| Sombra de una duda |

Shadow of a Doubt |

29 Jan. 1945 |

Jan. 1943 |

108 min. |

108 min. |

| Sabotaje |

Saboteur |

27 Dec. 1945 |

April 1942 |

108 min. |

109 min. |

| Recuerda |

Spellbound |

30 Sept. 1946 |

Oct. 1945 |

111 min. |

110 min. |

| Naúfragos |

Lifeboat |

1 July 1947 |

Jan. 1944 |

76 min. |

96 min. |

| Ventana indiscreta |

Rear Window |

3 Oct. 1955 |

July 1954 |

112 min. |

112 min. |

| De entre los muertos |

Vertigo |

29 June 1959 |

May 1958 |

|

|

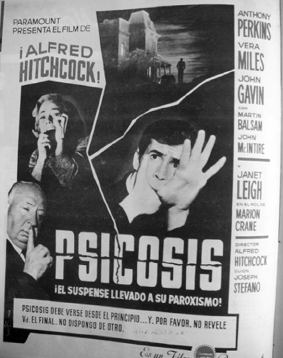

| Psicosis |

Psycho |

2 April 1961 |

June 1960 |

103 min. |

110 min. |

As Virginia Higginbotham notes in Spanish Film Under Franco, American movies flooded Spanish screens even before the Spanish Civil War, and ‘the Hollywood star system literally outshone the home product, so that Spaniards deserted their national cinema in droves’ (1998: 4). According to Higginbotham, American incursion into Spanish cinema ‘reached alarming proportions in the 1950s’ (ibid.). In 1941 a law was passed, reaffirming the policy already in effect since the early 1930s, that made it illegal to show foreign films unless they were dubbed into Spanish. Foreign films, including Hitchcock’s, entered into the ideological equation of supporting the dictatorship in a particularly pernicious fashion. Spanish producers were granted import and dubbing licenses for the more lucrative foreign films, depending on how well the native films they produced passed the Spanish censors. Higginbotham notes that an undercover trade of import licenses was rampant in the 1950s. Part of the attraction of Hollywood films for Spanish audiences was that even though they went through the dubbing process, which significantly delayed their release, foreign films were censored less than the native product. Even when the absolute requirement to dub foreign films was lifted on 31 December 1947, the practice continued because, as Higgenbotham observes, ‘dubbing, now a small industry within Spanish cinema, had become expected by the Spanish public’ (1998: 9). In an extensive interview in the film magazine Fotogramas in 1946, the Spanish director Florián Rey came out vigorously against dubbing. He insisted that it gave American films, like Hitchcock’s, an unfair commercial advantage that they would not have had if Spanish moviegoers had to read subtitles. Responding to the interviewer’s query ‘And does dubbing damage our production so much?’, Rey states:

Naturally; we contribute the only value, our language, so that they compete with us, who are and will be technically inferior. Without dubbing, the public would be wanting to hear Spanish. And as long as foreign films speak in Spanish, our cinema will be stunted. (15 December 1946: n.p.)

The film journal Triunfo questioned the practice of dubbing more from aesthetic rather than commercial grounds. In 1961 Triunfo prominently featured letters from readers who wrote in favor of V.O. or ‘versión original’. E.R.T. from Madrid asserted that its absence was a sign of Spain’s provinciality when compared to other European countries: ‘I can’t understand why Madrid, having the importance that it has as a great city, doesn’t have any movie theatre dedicated to the exhibition of movies in their original version’ (5 January 1961: 1) Another reader, J. M. Hernández Lucas, rails against the absence even of original titles: ‘Could it be possible for the foreign films that are screened to show the original title next to the Spanish title? A lot of confusion will be avoided this way for those of us that see foreign films and also some “impostors” operating a bait and switch (offering movies that “seem” important and really are unbearable “ripoffs”)’ (4 May 1961: 1). The advent of V.O. theatres in Spain, which arose as art-house phenomena, and hence not the logical exhibition space for a Hitchcock film, comes after the release of Hitchcock’s last film in 1976. With the important exception of the San Sebastián Film Festival, Hitchcock’s films debuted in Spain dubbed into Spanish. Most received wide commercial distribution.

IV. HITCHCOCK FOR THE TRADE: ASSESSING VIABILITY AND RATINGS BEGINNING IN THE 1950S

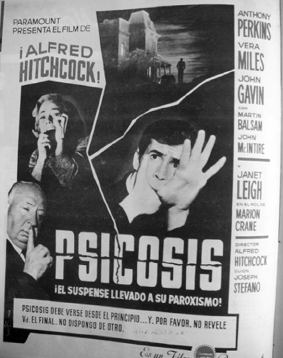

Another principal source that documents the reception in Spain of Hitchcock’s films post-1950 – that is, at the height of his commercial success – is Cine asesor, or ‘Movie Assessor’, a trade journal for movie theatres. By monitoring the reception of each film at its Madrid opening, the journal projected the box office potential of the film. It also suggested promotional blurbs for press ads and for theatre marquees as the film opened in the rest of the country. Each entry in Cine asesor includes the Madrid opening date, the theatre’s name, the running time of the Spanish print of the film and the approved rating code. Entries also give brief quotes from five or six Madrid newspapers, a paragraph synopsis of each film, and most interestingly a paragraph assessment of the film’s quality and earning potential. Most, but not all, of Hitchcock’s films after 1954 were reviewed in Cine asesor. Through Cine asesor we know for example that for Psicosis (Psycho) theatre owners were encouraged to imitate Hitchcock’s innovative marketing campaign, used in the US: ‘The “extra” publicity, which ought to be done, will include as an advertising slogan the prohibition against entering the movie theatre once the movie has begun, in addition to Hitchcock’s request that no one reveal the ending’ (1961: 2432). Psycho more than any other Hitchcock film consolidated his reputation as the master of suspense in Spain.

Cine asesor only obliquely acknowledges the existence of censorship which, as we shall see shortly, was significant in the case of Psycho; usually it listed running time as ‘Tiempo de proyección sin cortes’ (‘Running time without cuts’) and included the official rating for each film. Nonetheless, a comparison of the times in Cine asesor and those listed in Sloan’s filmography shows that of the eight films reviewed in Cine Asesor only two – The Birds (1963) and Frenzy (1972) – did not have their running time shortened for Spanish release. These cuts were the marks of the censors. Even after these cuts most of Hitchcock’s films that Cine asesor reviewed, which are listed in the table below, received a rating classification of ‘Rosa’ (3) – that is, for a public 18-years-old or above. Dial M for Murder (1954) and Torn Curtain (1967) received a rating of ‘Rosa (3) – Provisional,’ for a public years 16-years-old or above. The rating for Frenzy was put at ‘Rosa (3)’, but a possible further restriction of ‘Rosa (4)’ was suggested.

Hitchcock’s admonitions for Psycho were prominent in Spanish ads.

The following table is derived from the entries in Cine Asesor:

| Spanish Title |

Original Title |

Madrid Opening |

Original Release |

Spanish Running Time |

Original Running Time |

Entry No. & Rating |

| Crimen perfecto |

Dial M for Murder |

23 Dec. 1954 |

April 1954 |

102 min. |

123 min. |

836 Rosa (3)-Prov. |

| La ventana indiscreta |

Rear Window |

3 Oct. 1955 |

July 1954 |

108 min. |

112 min. |

1036 Rosa (3) |

| Psicosis |

Psycho |

2 April 1961 |

June 1960 |

103 min. |

110 min. |

2432 Rosa (3) |

| Los pájaros |

The Birds |

7 Oct. 1963 |

March 1963 |

120 min. |

120 min. |

285–63 Rosa (3) |

| Marnie, la ladrona |

Marnie |

22 Oct. 1964 |

June 1964 |

111 min. |

120 min. |

260–64 Rosa (3) |

| Cortina rasgada |

Torn Curtain |

13 April 1967 |

July 1966 |

92 min. |

120 min |

98–67 Rosa (3)-Prov. |

| Topaz |

Topaz |

30 Nov. 1970 |

Dec. 1969 |

122 min. |

126 min. |

298–70 Rosa (3) |

| Frenesí |

Frenzy |

21 Dec. 1972 |

May 1972 |

115 min. |

115 min. |

318–72 Rosa (3), can be 4 |

The entry in Cine asesor for Crimen perfecto (Dial M for Murder), the first Hitchcock film reviewed by the trade journal, gives a sense of what Spanish distributors thought of a Hitchcock film in the 1950s and hence how a Hitchcock film was initially presented to the Spanish public:

The director of this film has a well-earned reputation in the crime genre, and combine that with the fact that the general plot of this work is well known, already staged theatrically in several Spanish locations, to complete the appropriate advertising. Made in good ‘Warner Colour’, this feature film isn’t boring in spite of the fact that it happens almost completely in an interior space – the apartment of the protagonist couple. Given the masterful direction and the magnificent acting, interest grows as the climactic scenes near, fulfilling the wishes of the audience in the triumph of justice, a good solution for the emotional ‘suspense’ of the plot. We project that, due to its qualities and interest, this film will get the public’s approval, being able to bring in a GOOD RETURN at the box office at any locale at which it is shown. For audiences more interested in action films it could turn in a MEDIUM profit due to the fact that it takes place almost totally in one location and with excessive dialogue. It can be programmed for regular weekends in any locale. (Cine Asesor IV: 836)

This commentary on Dial M for Murder reveals more about the sophisticated cultural scene into which Hitchcock entered than about the film itself. His public was an affluent crowd that went to the theatre and the movies, and read ABC. Most Madrid newspaper critics excerpted here wrote about the differences bet-ween play and film since the play upon which the film is based had already made it to the Spanish stage when the film opened. ABC’s judgement represents a majority opinion, albeit phrased in a circumlocution: ‘we can’t say that what we are offered is photographed theatre’ (ibid.). Marca’s unimpressed reviewer dissents from the others, writing: ‘Detective plot without mystery but with surprises, written for the theatre and transplanted to the movies without changes’ (ibid.).

Although there are gaps in Cine asesor – some Hitchcock films of his later productive period were not reviewed – the documentation for the openings of his films of the 1950s until his death is the most extensive, however localised, overview of their initial reception in Spain. If this approach comes to the topic in medias res, it describes a mutually reinforcing relationship. Cine asesor appears on the scene because the movie market, in which Hitchcock’s films participated, showed tremendous growth in Spain in the 1950s. We should also look back upon what preceded this peak period.

V. FIRST STEPS, MANY FEWER THAN THIRTY-NINE STEPS

Although current books in Spanish that survey the whole of Hitchcock’s career, such as Guillermo Balmori’s edited critical anthology El universo de Alfred Hitchcock (The Universe of Alfred Hitchcock, 2007), look upon his British period, both of silent films and later talkies, as predicting the narratives, themes and aesthetics of his later career, it is hard to make the argument that in their initial showings in Spain any of the characteristics for which ‘British Hitchcock’ was eventually celebrated radically stood out in the cultural landscape. These movies were judged by different criteria then or barely at all. The initial reception record of this period in Madrid or Barcelona, as can be discerned in reviews in the major metropolitan newspapers, is a matter of minimal, though positive paragraphs. The first mention of one of his films to be shown in Madrid, his co-directorial silent film debut De mujer a mujer (Woman to Woman, 1923), was praised more for the elegance of the Princesa movie theatre and the beauty of the actress Betty Compton. The film received ‘sincere laudatory comments’ afterwards from the spectators. When Champagne (1928) debuted as the second film of a double bill at the Palacio de la Prensa on 23 April 1929, the ABC reviewer lauded British comedies in general, calling the film ‘a magnificent cinematographic comedy, British brand, that completes the programme of this theatre and that has achieved outright and definitive success, like all of those of this brand that have been shown this season’ (1929: 45). Champagne is also the first film for which Fernández Cuenca serves as an original source since he attended the premiere. Throughout El cine británico de Alfred Hitchcock Fernández Cuenca rails against ‘the youth of the Positif group’ and their disparagement of Hitchcock’s British films in that journal after the 1956 Cinematheque series. He uses his recollections as eyewitness to the first screenings in Madrid to set the record straight. It puts him, however, in the difficult position of defending Champagne, one of Hitchcock’s minor works:

Peter Nobel considers it one of the most disappointing works of Hitchcock and the director himself would recognise later, according to what he told Truffaut that ‘it is probably the lowest ebb in my output’. The members of the Positif group come to the conclusion that the first and last frame of the film, ‘of a Hitchcockian virtuosity, are ridiculous’. Absolute falsehood, because there is nothing ridiculous in Champagne. I remember its premiere in Madrid very well and that we all enjoyed ourselves a lot with this comedy, which is quite pointless and doesn’t go into any depth about anything it comes up with, made somewhat in the American style, but with a perfect and refined technique, with an abundance of photographic effects like double images, deformations and fast motion. It wasn’t a great movie, not even a good movie; perhaps we Madrid fans wouldn’t have paid much attention to it had we not had absolute proof of Hitchcock’s merits, but we did feel deceived although not annoyed. (1974: 39–40)

Fernández Cuenca is claiming that his Madrid chums already intuited Hitchcock’s merit in 1929. Certainly he became a fan early on. However, more research is needed on how a more general public opinion was shaped regarding his British films that today we view as more significant, such as El enemigo de las rubias (The Lodger, a Story of the London Fog, 1926) or Hitchcock’s first talkie, La muchacha de Londres (Blackmail). Since as Fernández Cuenca notes the process of dubbing did not exist at the advent of sound film, Blackmail may have been the only Hitchcock film to have debuted in Spain in its original version with Spanish subtitles. Curiously Fernández Cuenca notes its running time as five minutes longer than the time Sloan gives for the American version.

A search of the Spanish titles of the films in ABC and La Vanguardia yields no other paragraph-long reviews, and no mention of Hitchcock in the 1930s until Valses de Viena (Waltzes from Vienna, 1933), which is also the first Hitchcock film that Fernández Cuenca records in his card catalogue as opening in 1935. The review of this period film in ABC is brief and bland. To extend the dance metaphor, this represents an insecure, and hence supremely tentative, first step since speaking of Waltzes from Vienna, a bio-pic of Strauss father and son, Hitchcock despaired to Truffaut: ‘It had no relation to my usual work. In fact, at this time my reputation wasn’t very good, but luckily I was unaware of this. Nothing to do with conceit; it was merely an inner conviction that I was a filmmaker. I don’t remember ever saying to myself, “You’re finished; your career is at its lowest ebb.” And yet outwardly, to other people, I believed it was’ (Truffaut 1984: 85). Fernández Cuenca, who had more opportunities to see Hitchcock films than most people, for instance travelling to London in 1931 to see The Skin Game (1931), which never opened in Spain, writes of his contemporaneous impression of Waltzes from Vienna: ‘We critics who already felt admiration for the powerful personality of Alfred Hitchcock felt disappointed when faced with a routine work that didn’t contain even the minimum spark of that personality’ (1974: 59).

By 1935, when El hombre que sabía demasiado (The Man Who Knew Too Much, 1934) debuted in Madrid, there was no doubt that Hitchcock was viewed positively as an auteur in Spain. Fernández Cuenca not only saw it shortly upon opening but immediately went back to see it again:

I keep a vivid memory of this movie: I saw it in the afternoon session of the Madrid Avenida theater and was left so taken in and even bewildered that before writing my review I went back to see it again in the evening session in order to appreciate, now free of the sorcery of its disturbing accelerating action, the strictly cinematographic qualities of the story. And I came to the conclusion that it was an extraordinary film. (1974: 64–5)

Fernández Cuenca in particular praised the use of projection slides in the Albert Hall sequence for giving the effect of an immobilised backdrop of engaged spectators. For him, moreover, The Man Who Knew Too Much inaugurated ‘a new genre: the spy melodrama with strong intrigue and many elements of suspense’ (1974: 64). Much later he mocked the ‘absurd opinions’ of Positif group critics who found the film ‘incredibly poorly constructed’ (1974: 65). He remained a passionate defender of the The Man Who Knew Too Much throughout his career, perhaps even more so as the years went by because in San Sebastián in 1958 he asked Hitchcock himself if he preferred his British original or his Hollywood remake. Always cognisant of his audience, Hitchcock obliged and answered without missing a beat, ‘La primera, claro, porque es la más locamente imaginativa’ (‘The first one, of course, because it is the most crazily imaginative’) (ibid.). Since this interview was never published it is worth pausing for a moment in our chronological presentation of Hitchcock’s initial Spanish reception to note for posterity what else Hitchcock said to Fernández Cuenca in 1958 about the two versions and what shifting to make films for a US audience meant:6

Hubo que sustituir la fantasía por el sentimentalismo, que en América es fundamental. No olvide usted que es femenino el ochenta por ciento del público que en los Estados Unidos va al cine. Esto obliga a aceptar compromisos que a veces no son buenos. (We had to replace fantasy with sentimentality, which is fundamental in America. Don’t forget that eighty per cent of the public that goes to the movies in the US is female. That forces one to make compromises that sometimes aren’t good.) (1974: 65)

For Hitchcock, then, his crossover to Hollywood meant adjusting to a primarily female audience and becoming more melodramatic. Since this shift in tone and genre had a major impact in how Hitchcock’s crossover was received in Mexico, we will come back to this topic again in chapter five.

To return to our chronological survey of the Spanish reception, Treinta y nueve escalones (The Thirty-Nine Steps, 1935) received a substantial review in ABC when it opened in Madrid on 8 January 1936. Importantly in praising the film the reviewer Alfredo Miralles points to the balance between humour and intrigue:

Alfred Hitchcock has chosen to base this movie on Jack Buchan’s novella entitled The Thirty-Nine Steps, not for its more or less crime theme, but since it is one of so many stories whose plot offers a good director, like him, the chance to produce a good, interesting film, more interesting still since there is intrigue in it besides the main event. And thus, he has begun making it his film, treating it to first-rate refined comedy, encrusting its scenes with great expressive force, which is as much comic as dramatic; employing an excellent photographer and some magnificient natural locations – the desolate and wild mountains of Scotland – that add to the events a very fitting atmosphere for the adventures of spies, counterspies and counter-counterspies whose impenetrable schemes were the original object of attraction for the author. (8 January 1935: 49; emphasis in original)

For Miralles, Hitchcock’s incorporation of both comedy and drama is one of the signatory characteristics and great positives of his filmmaking. As a first impression of Hitchcock, moreover, we may say that at least one influential Spaniard appreciated his humour especially when taken against the backdrop of scenarios of desolation and intrigue.

Miralles perceived defects in The Thirty-Nine Steps, too. Although he argued against interpreting the film realistically, he critiqued its plot for ‘the popular method of hastening towards the climax through channels lacking in originality’ (ibid.). Nonetheless, the film kept Miralles thinking long after it ended, for as he concluded his review, ‘after all in a mystery film it can’t surprise us that certain things remain enveloped in the shadows of the inexplicable’ (ibid.). It is not hard to imagine that the world of spies and counterspies, or ‘the shadows of the inexplicable’ that Miralles saw in The Thirty-Nine Steps, resonated with the uncertainties of the Civil War that shrouded the country.

To recall, Madrid was under siege from November 1936 to March 1939. Although the Battle for Madrid spared the movie theatres concentrated along the Gran Vía from serious damage, Hitchcock’s British films made during those years – Inocencia y juventud (Young and Innocent, 1937), Alarma en el expreso (The Lady Vanishes, 1938), Posada Jamaica (Jamaica Inn, 1939) – opened in Spain after the Civil War. The Lady Vanishes, which opened at the end of 1941 in Madrid and Barcelona, received the most notice of his British films after The Thirty-Nine Steps. The ad from La Vanguardia (20 Dec. 20, 1941: 4) shows how aesthetics and entertainment, as well as Hollywood prizes, were used to launch the film with the Catalan public.

To complete our listing of Madrid openings of Hitchcock’s films, and fill in the dates for the films not recorded either by Fernández Cuenca or in Cine Asesor, we turn to the opening day reviews in ABC, the principal newspaper of Madrid and the national paper of record until the launching of El País after Franco’s death. Ideologically opposed to the dictatorship due to its monarchist stance, ABC was well respected by the intellectual elite for its cultural criticism. The caricatures of the female and male protagonists of Hitchcock’s films that accompany many of these reviews, upon which I will comment intermittently throughout this chapter, indicate how significant these films and their stars were for the Spanish readership of the times since only a select few cultural events, let alone films, were illustrated on any given day by the paper’s signature artist.

Ad for The Lady Vanishes from La Vanguardia.

| Spanish Title |

Original Title |

Review Date in ABC (Madrid) |

Original Release |

Madrid Theatre(s) |

| Treinta y nueve escalones |

The Thirty-Nine Steps |

8 Jan. 1936 |

Sept. 1935 |

Figaro |

| Enviado especial |

Foreign Correspondent |

1 Dec. 1944 |

August 1940 |

Palacio de la Música |

| Encadenados |

Notorious |

1 Oct. 1948 |

July 1946 |

Coliseum |

| La soga |

Rope |

18 Nov. 1951 |

August 1948 |

(Not listed) |

| Atormentada |

Under Capricorn |

4 Nov. 1952 |

Sept. 1949 |

Palacio de la Música |

| Yo confieso |

I Confess |

26 Feb. 1954 |

Feb. 1953 |

Avenida |

| Atrapa a un ladrón |

To Catch a Thief |

18 Nov. 1958 |

July 1955 |

Lope de Vega |

| Falso culpable |

The Wrong Man |

17 June 1959 |

Dec. 1956 |

Carlos III, Roxy B |

| Con la muerte en los talones |

North by Northwest |

29 Dec. 1959 |

July 1959 |

Palacio de la Prensa, Carlos III, Roxy B |

| El hombre que sabía demasiado |

The Man Who Knew Too Much |

26 July 1960 |

May 1956 |

Palacio de la Prensa, Roxy B |

| Pero…¿Quién mató a Harry? |

The Trouble with Harry |

15 Nov. 1960 |

Oct. 1955 |

Popeya, Palace, Gayarre |

| Pánico en la escena |

Stage Fright |

9 May 1961, Sevilla; 12 July 1961, Barcelona |

Feb. 1950 |

|

| El caso Paradine |

The Paradine Case |

7 July 1967 |

Dec. 1947 |

Palacio de la Prensa, Bilbao, Progreso, Velazquez |

| La trama |

Family Plot |

14 Oct. 1976 |

March 1976 |

Amaya |

| Blackmail, Murder, Number Seventeen, Rich and Strange |

|

V. O., 10 Dec. 1981 |

|

Alexandra |

| La mujer solitaria |

Sabotage |

V.O., 4 August 1983 |

|

Capitol |

VI. WHAT ESCAPED CENSORSHIP AND WHAT DID NOT: LIFEBOAT AND PSYCHO

Although both Fernández Cuenca and Cine asesor are incomplete in noting which Hitchcock films played in Spain and when – cards for The Thirty-Nine Steps or for The Birds are missing in Fernández Cuenca’s catalog, and Cine asesor has nothing on To Catch a Thief (1954) or Family Plot (1976) – the record of all films that were reviewed in contemporaneous Spanish newspapers, taking together the perspective of a film scholar and that of an industry specialist, shows which Hitchcock films were judged noteworthy in their times.

The charts above from Cine Asesor and Fernández Cuenca point to which Hitchcock films were cut, and even on that they do not always agree, and they do not tell us what was removed when the film was first shown. Spanish Film Archives do not contain prints of foreign films. To ascertain what was actually cut is, regrettably, beyond the scope of this project.7

Although this chapter concentrates on what happened in Madrid, it bears noting that under Franco the pattern and policies that were set in Madrid, especially as concerned film censorship, were hegemonic. How censorship was subsequently even further exercised throughout the country, however, was extremely arbitrary. In 1963 José María García Escudero, head of Dirección General de Cinematografía y Teatro, codified Spanish censorship and spelled out the list of prohibited topics – ‘those favoring divorce, abortion, euthanasia, and birth control and those appearing to justify adultery, prostitution, and illicit sexual behavior’ (Higginbotham 1998: 12). Though not explicitly noted on this 1963 list, the prohibition of nudity and of any satirical depiction of the military were constants of film censorship from the 1930s until after Franco’s death.8 Before 1963 censorship had been much more arbitrary. Film research is only now beginning to note, if not unravel, its effects. One key document is the recent collection of articles from the journal Secuencias, edited by Laura Gómez Vaquero and Daniel Sánchez Salas, El espíritu del caos: Representación y recepción de las imágenes durante el Franquismo (The Spirit of Chaos: Representation and Reception of Images During Franco’s Era, 2009). In his article in this volume ‘El espíritu del caos: Irregularidades en la censura cinematográfica durante la inmediata postguerra’ (‘The Spirit of Chaos: Irregularities in Cinematographic Censorship during the Immediate Post War Period’) Josep Estivill studies the correspondence in 1940 with Metro Goldwyn Mayer Ibérica. He quotes from a letter of an MGM representative to the Under Secretary for Press and Propaganda in the Government Ministry in which the former complains with exasperation of the impossible situation for movie distributors if ‘the campaigns by the press, certain organisations like Catholic Action and certain provincial authorities continue to be tolerated as they have been up to now’ (2009: 83–4). Though Hitchcock was not produced or distributed by MGM at the time, but rather by Selznick and Universal, or Warner Bros., this statement provides a list of shared woes of the most bothersome, if not effective sources of censorship in Spain for American movies. Estivill notes that what was actually shown outside of Madrid in the provinces differed because each movie theatre went its own way in doctoring the print shown. Estivill’s laments demonstrate how little we know about what was actually screened: ‘We also don’t know exactly what relationship was forged between the censor and some of the most emblematic films of the period, such as The Great Dictator (Charles Chaplin, 1940), Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1940) or Battleship Potemkin (Sergei Eisenstein, 1925)’ (2009: 63). Simply put, much remains to be learned about whether Hitchcock’s films were censored or not, and if so, how.

Lifeboat provides one case in which we know for certain that Hitchcock’s film was censored. According to Fernández Cuenca’s catalog it was severely cut by ten minutes from its original running time. I have not been able to see the censored version for a comparison, but I surmise that the presentation in the film of the suicide of Mrs. Iggley after realising her baby was dead was one likely cut. Still, when Lifeboat opened in 1947 in Barcelona, H. Saenz Guerrero, writing in La Vanguardia, called the film ‘one of the most significant movies that we have seen in recent times’ (15 January 1947: 2). On the same page of La Vanguardia as this laudatory review there was an ad for Casablanca, so Saenz Guerrero’s estimation was high praise indeed in 1947. Lifeboat’s topos of isolation could well have spoken to the particular condition of Spain as a country cut off from Europe and the rejuvenating stimulus of the Marshall Plan. Yet the contemporary newspaper reviews in ABC and La Vanguardia, which praised the film highly, spoke of the clash of universal values rather than of an allegory of Spanish marginalisation. Luis Mariano González González, in his book on historical films under Franco, Fascismo, Kitsch y el cine histórico en España (1931–36) (Fascism, Kitsch and Historical Movies in Spain (1931–36), 2009), notes that the official film policy in fact encouraged films that depicted Spaniards as courageous underdogs, as a way of rallying public opinion against international sanctions of the Franco regime, such as its exclusion from the League of Nations. To turn to a contemporaneous voice, in 1947 the regular columnist Floristán of Fotogramas in an article entitled ‘Alfredo Hitchcock y Ricardo Wagner’ (‘Alfred Hitchcock and Richard Wagner’) does present an interpretation of Lifeboat which addresses marginalisation:

Why a Wagnerian melody for a black man’s flute? This music is associated with the German in a situation in which he is every one’s enemy. We can’t believe that Hitchcock picked this music at random. He must have had his reasons. The black man, racially excluded from that community of white men, is the one who is best situated above the fray. He finishes the prayer that another has begun; he and the German sing Schubert’s ‘Wild Rose’ together. The boat, wracked with anxiety, slips away over the silent ocean, and a black man plays the marvelous Wagnerian melody that speaks of immutable beauties and of a world of poetry and dreams that knows nothing of cruelty. Afterwards, much later, when in a fit of anger everyone throws themselves onto the enemy, he watches the horizon. It seems as if he is asking himself: What kind of men could there be to come to save us? (15 February 1947: n.p.)

Floristán’s analysis, which links musical appreciation to racial politics, privileges the position of the black man in Lifeboat. The query ‘Who may be coming for us next?’ appears to justify a climate of fear and reaffirm a stance of isolation. The black man’s non-intervention indeed may signal nostalgia for Germanic ideology, a position that would have been entirely consistent with the Franco regime.

Overall, as far as we know today, the censorship of Hitchcock’s films in Spain through extreme excision was infrequent. It was nothing compared to that endured by the greats of European art cinema like Ingmar Bergman whose films were not only cut but also reorganised like jigsaw puzzles to present an ideological argument directly opposite to the original version’s. No Hitchcock film was ever banned like Rossellini’s or Buñuel’s. For this reason Hitchcock’s witty evasions of the US movie code, including his depictions of homosexuals, reached a Spanish audience, too. Even in the high-minded review of Lifeboat quoted above Hitchcock’s humour was also noted.

A recent book by Alberto Gil, La censura cinematográfica en España (The Cinematographic Censorship in Spain, 2009) illuminates the breadth of censorship of Hollywood films in Spain. He addresses censorship in Spain of films of all nationalities in terms of three thematic blocks: love and sex, morality and religion, and politics and society. Gil confirms that although Hitchcock had laboured long for the Psycho shower scene to pass US movie censors, the implied depiction of nudity even when carefully framed, did not pass muster in Spain. Nonetheless Cine asesor expected the film to be profitable for exhibitors: ‘GOOD YIELD that will reach VERY GOOD among fans of the genre: “With all its horrors and artifices it is one of those films that are viewed with bated breath and that cause an impact of hallucinatory “suspense” until you get to the surprising ending”’. (1961: 2432). The cuts to Psycho did not affect either the film’s popularity in its initial runs or its iconic status, which is seen in the repeated reference to Psycho in reviews of subsequent Hitchcock films. Psycho became the single most important reference point in defining Hitchcock’s artistry in the Spanish-speaking world.

VII. TRANSFORMATIONAL MOMENTS: REBECCA AND SPELLBOUND

Although Vertigo represents the cinephile’s Hitchcock, Psycho brings forth the Jeopardy answer (always in the form of a question) ‘What is a Hitchcock film?’ in most parts of the world. How then is the reception of Hitchcock culturally unique to Spain? Rebecca and Spellbound provide two keys to understanding these divergences. For one, Rebecca is immensely important as it represents a transnational moment on multiple fronts. It was Hitchcock’s first Hollywood film, and thus constitutes his crossover moment from British to American, and a huge leap for him in production values. Likewise it inaugurated the first Berlinale, thus heralding the era of European film festivals and delineating a place for some Hollywood films in them as well. In fact, Hitchcock reentered Europe with a film that relied on an essentially British ambience. Rebecca represents a new hybridisation that was closely studied in Spain. For another, Spellbound, or Recuerda (literally ‘Remember’) as it was known in Spain, is significant for the collaboration of Dalí whose minor intervention had a long-term impact. Psychoanalytical complexity, especially when represented as a dream sequence, became recognised as a key element in Hitchcock’s films.

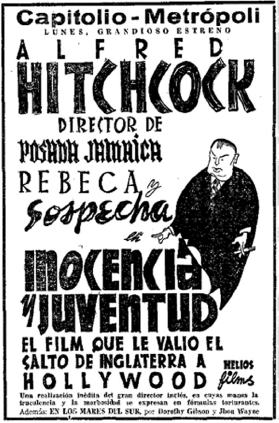

One of the legendary ironies of Hitchcock’s career, which is often evoked to show how true greatness is ignored during the time in which the artist lived and worked, is that Hitchcock was nominated five times for an Academy Award as Best Director but never received this accolade. He won the Best Picture Academy Award only once, for Rebecca; and Selznick symbolically snatched that honour away in Hollywood because Selznick, not Hitchcock dominated the news for his feat of producing the winning Best Picture two years in a row, first with Gone with the Wind (1939), then with Rebecca. These statistics are often evoked to console someone who has lost out on a prize. Martin Scorsese became sick of hearing it at Academy Award time.9 There is some truth to the lesson of Hitchcock’s history of disappointing award results and we need to keep it in mind as we survey the initial reaction to his films in Spain. Curiously, though not everyone got the facts right, Hitchcock’s move to Hollywood was widely celebrated at the time. In 1944 a large ad in La Vanguardia for the opening of Inocencia y juventud (Young and Innocent, 1937), touts this British period Hitchcock, considered today one of his minor works as ‘El film que le valió el salto de Inglaterra a Hollywood’ (‘The film that made possible his jump from England to Hollywood’) (2 July 1944).

The advertiser knew that the jump to Hollywood was a big deal that could sell films. Hitchcock’s crossover moment – which Rebecca, not Young and Innocent, represents – set the pattern. It received a slew of Academy Award nominations in all categories, won for Best Cinematography and Best Picture, but not for Best Director. Hitchcock pleased the public, but not those who voted for prizes. This provided the evidence that defined him as a commercial director, but not a great artist, the paradigm that Truffaut later deflated. The reception history of Rebecca in Spain, however, has come to symbolise the complex significance of spectatorship in Spanish political and cultural history that goes beyond merely tagging Hitchcock as commercial or tallying prize lists.

Marsha Kinder in the chapter, ‘Micro- and Macro-Regionalism in Catalan Cinema, European Coproductions, and Global Television’ in Blood Cinema interprets the case of the Catalan filmmaker Lorenzo Llobet Gracia and his film Vida en sombras (Life in Shadows, 1946–7) to illustrate how the film’s celebration of Hollywood style, and most particularly that of Hitchcock in Rebecca, fits into a dynamic of regional resistance. Kinder writes: ‘During the Francoist era, any difference in verbal or filmic language in Catalan cinema carried subversive implications, even when the plot seemed more personal than political’ (1993: 394). She further observes that Catalan cinema subverted Castilian dominance ‘by exposing it as marginal (and regional) within the international context, thereby allying itself with other dominant cultural centers, like Paris or Hollywood’ (1993: 395).

Ad for Young and Innocent from La Vanguardia touts Hitchcock’s jump to Hollywood.

To provide some background, Life in Shadows tells the story of a filmmaker and movie-lover called Carlos Durán, who was literally born in a movie theatre. He becomes a documentary filmmaker. While filming the action at the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, he witnesses the death of his wife by a stray bullet. He blames himself for her death and subsequently quits his film career. Yet watching the scene in Rebecca in which Max de Winter (Laurence Olivier) and his second wife (Joan Fontaine) themselves watch home movies of their honeymoon together, Durán becomes inspired to make movies again.

The particular sequence from Rebecca that allows the character Durán to resume making films has been interpreted as homage to Hitchcock’s own home life in which Alma and he happily bantered over movies. This slice of life, however, is a part of the film that had no connection to Du Maurier’s novel. Hitchcock chafed at Selznick’s insistence that he keep closely to the book in his adaptation. McGilligan calls Mr. de Winter’s line in the home movie sequence (‘Oh look, there’s the one where I left the camera running on the tripod, remember?’) ‘far and away the purest Hitchcock moment in Rebecca’ (2003: 243). Significantly, the moment Llobet Gracia selected for inspiration was that rare sign of humour in Rebecca, which Hitchcock himself told Truffaut was his most humourless film. Kinder describes the adapted scene in Life in Shadows:

After watching the scene from Rebecca in which Joan Fontaine and Laurence Olivier are looking at home movies from their own happier past, Durán (who physically resembles the young Olivier) returns to his room to watch home movies of himself and his dead wife. This act of double spectatorship enables him to find a way out of his own entrapment. Gradually, the close-ups of him as spectator replace his screen image in the home movie. He is able to suture himself into the imaginary scene from the past and as an empowered spectator to actively draw a blessing from the ambiguous image and words of his dead wife. Like the scene in John Ford’s Young Mr. Lincoln (1936) in which the hero consults his dead love about whether to study the law, Durán uses the recorded words of his dead wife (‘What do you want me to say?’) to authorize his own desire to resume his pursuit of cinema. (1993: 410)

Although Llobet Gracia does not maintain the light-hearted tone of Hitchcock’s original scenario, still it is important to note that Hitchcock inspired Spanish filmmakers, and that these same filmmakers recognised and adapted Hitchcock’s originality and humour.

For the filmmaker Llobet Gracia seeing Rebecca after the end of the Spanish Civil War, in which his father had fought on the Republican side and died, was a life-changing experience. Just as in the film the character Durán overcomes his grief over his wife’s death through watching Rebecca, in his own life Llobet Gracia resumed filmmaking, perhaps putting aside his grief over the death of his father in the war, through a similar act of spectatorship of Hitchcock’s film. Because Life in Shadows realistically depicted the Spanish Civil War on screen, and moreover sympathised with the Republican side, the film was heavily censored and virtually unknown for decades. Even after Franco’s death there were only occasional screenings in film clubs in the 1970s until the Spanish Filmoteca or Film Archives reconstructed the film in the 1980s. Even then it was only seen at limited festival screenings and is still known mostly through the writings of critics such as Marsha Kinder and John Hopewell. Nonetheless Rebecca has come to represent a gesture of opposition or liberation in Spanish cultural history. Kinder argues that emulating Hollywood, and Rebecca in particular, had the positive effect of stimulating not just Llobet Gracia, but the whole Catalan film industry as a micro-regional force in opposition to the xenophobic national policies, which emanated from the centre, Madrid. Above all she finds Life in Shadows to be ‘a model for how to use a personal romantic/sexual discourse to talk about political topics that were otherwise suppressed’ (1993: 409).

Llobet Gracia’s exceptional case of spectatorship is only one sign of the localised significance of Rebecca in Spanish cultural history. Hitchcock’s melodrama touched a nerve in Spain as no other Hitchcock film had before. It became an ideological flashpoint from the moment it opened. A comparison of the reviews of the major newspapers of Barcelona and Madrid shows the strong impact that Rebecca, which was shown uncensored, had throughout the country. Reviewers sparred in hyperbolic language that bordered on Biblical exegesis as much as film criticism. To begin on the political right, on the premiere of Rebecca in Madrid the ABC film critic Rodenas came close to invoking Old Testament wrath upon Hitchcock for the moral turpitude of the character of Rebecca and for the tacit acceptance of suicide that the film’s conclusion implied:

The title of this movie, that recalls the name of that woman who was the wife of the patriarch Isaac, doesn’t have anything to do with the protagonist. Rebecca is a phantasmal shadow, a being that lived the life of a libertine, perhaps to gain notoriety and at the same time stir up the hate and scorn of her husband, a nobody Mr. Winter, who still has issues of considerable magnitude to settle against his – seriously scatterbrained – wife.

It’s important to recognise, in spite of the award that this ‘film’ received from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences of North America, that the subject matter isn’t decent because the tacit agreement between husband and wife to carry out her suicide goes against our sensibility, against our criterion as Christians, and seems inconceivable and monstruous to us. (16 December 1942: 16)

Continuing his review, Rodenas begrudgingly mentions the film’s Academy Award and then is forced to acknowledge the masterful hand of Hitchcock as auteur despite the film’s subject matter. Hitchcock, as he had in Lifeboat, implicitly condoned suicide, which was a moral taboo. Although the immorality of it all – accessible to those with ‘sick’ imaginations – sticks in his caw, Rodenas still has to admit the film is superlative on all other accounts.

We have set forth our due judgement on the merits of Daphne du Marier’s story, which actually is crude, excessively strong, based on feverish morbose lucubrations of its author. Now then: the production is admirable, because in a matter such as this, so accessible to sick imaginations, there is no more fitting technical display, nor more beauty, nor more artistic sensibility than that which Alfred Hitchock [sic] has used in making ‘Rebecca’. In this regard all the praise seems sparing, poor to us. The atmosphere is captured with impeccable subtlety. The echo of the voice in the garden and abandoned castle is of a great symbolic force, and the moment of the fire is impeccably done. Everything else about ‘Rebecca’, including the most insignificant details, which are the enchantment of the movie, show the marks of a masterful hand, who is the one who has given emotionality and liveliness to a matter accessible to any troubled mind. (ibid.)

After having noted the appropriate Christian reaction to Rebecca – that is, first to condemn the acceptance of suicide in the film – Rodenas has to admit, twice, that the film is ‘impeccable’ even in the smallest details. But one can almost hear him cringe and not be able to articulate the unspeakable – that is, that this film gave life to ‘a matter accessible to any troubled mind’. These circumlocutions show that Rodenas did not miss the full range of Hitchcock’s sexual representations in Rebecca, including Mrs. Danvers’ lesbian attraction to her former mistress. Rebecca’s full import as a lesson in the representation of gender in Spain, though significant from its first showing, remained unspoken for many decades. Only recently Boris Izaguirre cogently analysed this significant aspect of Hitchcock’s Rebecca in his book El armario secreto de Hitchcock (The Secret Closet of Hitchcock, 2005).

On the political left, the reviewer in La Vanguardia of the Barcelona opening of the film, a few weeks later than the Madrid opening, also chooses Biblical language, as had Rodenas, but the La Vanguardia reviewer writes of miracles, to gush about Rebecca.

There is something in the movies that is irreplaceable because definitively it is its basic force – that is to say, it is everything: technique. But technique put in service, subordinated at every moment to something even less irreplaceable: the immanent talent of its own filmmaker. These two sides, technique and talent, can work – excuse us the hyperbole – miracles. There it is giving credence to our assertion, one of the best movies that in these times American cinema has offered us is: ‘Rebecca’.

‘Rebecca’, which ‘United Artists’ has produced and Alfred Hitchcock has directed, is purely what has been noted: a prodigy, a miracle of the technique of a cinematographer in absolute maturity and above all, of an acute and intelligent vision put into service for this technique. And it is that it was truly difficult, very difficult to translate a vulgar and in certain moments melodramatic novel, as is the work of Daphne du Maurier, into a very beautiful symphony of rigorously cinematographic images.

It was also difficult to manage time and time again for the camera to be positioned in the exact, just, precise angle, such that in a lesson of good cinematic practice, there would be captured on film everything that needed to be shown and nothing more than what needed to be shown. (9 January 1943: 7)

The reviewer, F. G. S., then expounds at length about the acting and concludes his report seconding the judgement of the Academy Award bestowers: ‘But overall we find that first prize for acting, very just, very legitimate, so deservingly awarded to the protagonists of “Rebecca” in Hollywood’ (ibid.). Although the reviewer got it wrong, since no actor or actress won an Academy Award for Rebecca, his enthusiasm for the film, which did win Best Picture in 1940, is unbridled. He expresses none of the moral reservations of the ABC reviewer and praises Hitchcock for dealing so masterfully with the ‘vulgar’ material that he had to work with from Du Maurier’s novel. The Vanguardia review confirms the overwhelmingly positive reception that Hitchcock through Rebecca had as an artistically liberating force in Catalan film culture, if not among the Spanish left in general.

Hitchcock’s other transformational film also involved Catalonia through its native son Salvador Dalí. In a different take on the macro/micro regional politics then we saw with Llobet Gracia’s Life in Shadows, Dalí’s collaboration in Spellbound marked it on a more macro or national scale as the most Spanish of Hitchcock’s films. The role that Dalí played in the film’s conception would be repeatedly evoked in Spain whenever a special Hitchcock event was staged in that country. Today, because much of what Dalí created for Spellbound was never used in the film or ended up on the cutting room floor, the general impression is that the Hitchcock/Dalí collaboration was not just rocky, but unsuccessful. Although years later Hitchcock did describe Dalí as ‘really a kook’ in an interview for the BBC (quoted in McGilligan 2003: 364), a blunt assessment that many nonetheless share, that judgement does not diminish Hitchcock’s appreciation of Dalí’s artistic vision, or specifically of his painting. The attention paid to Dalí globally has not waned over the years. As Sara Cochran states in the catalogue for the exhibition Dalí and Film, a transnational venture between the Tate, MoMA and the Fundación Dalí, Hitchcock not only requested Dalí’s participation in the design for the dream sequence but also had a clear concept of how he, too, would innovate in filming Dalí’s product to ‘give his sequence a sharper focus than the rest of the film – almost ironic ultra realism’ (2007: 178). In a later TV interview, quoted by Cochran, Hitchcock explained his vision:

I requested Dalí. Selznick, the producer, had the impression that I wanted Dalí for the publicity value. That wasn’t it at all. What I was after was … the vividness of dreams … [A]ll Dalí’s work is very solid and very sharp, with very long perspectives and black shadows. Actually I wanted the dream sequence[s] to be shot on the back lot, not in the studio at all. I wanted them shot in bright sunshine. So the cameraman would be forced to do what we call stop it out and get a very hard image. This was again the avoidance of the cliché. All dreams in the movies are blurred. It isn’t true. Dalí was the best man for me to do the dreams because that is what dreams should be. (2007: 178)

Closer to the truth is that Hitchcock and Dalí ‘got on well’ but that the transformation of some of Dalí’s designs onto the Hollywood set never worked out. One vignette intended to have ornate pianos suspended over immobilised dancers: Cochran says Selznick ‘decided to make miniature pianos and suspend them from the ceiling’ (2007: 181); McGilligan claims ‘Hitchcock substituted miniature pianos dangling over the heads of live dwarfs’ (2003: 362). Whether the cost-cutting design came from Selznick or Hitchcock himself, when Dalí and Hitchcock viewed the filming together in August 1944 they concurred that, in Dalí’s words, ‘one saw, simply, that they were dwarfs’ (Cochran 2007: 181) and that the segment had to go.

Much of the lore around the most extensive vignette for Spellbound that went unused, the ballroom sequence in which Ingrid Bergman was to become immobilised into a classical statue, focuses on how Dalí’s vision actually fulfilled Hitchcock’s own sexual fantasies of capturing the unassailable Nordic star. Indeed Hitchcock and Dalí were kindred spirits and Dalí praised Hitchcock as ‘one of the rare personages I have met lately who has some mystery’ (McGilligan 2003: 361). Their collaboration on Spellbound transcended what was used in the film. What hit the cutting room floor of what Dalí drew or painted has not been lost but has become legendary. Its cultural history was rewritten many times over in Spain and elsewhere. To evoke Benedict Anderson’s concept from Imagined Communities (1991), the Dalí/Hitchcock collaboration forms part of the ‘imaginary museum’ of Hitchcock in Spain. It was widely reported that King Juan Carlos and Queen Sofía opened the exhibition of the Dalí Spellbound backdrops at the Museu-Fundación Dalí in Figueres in 2004. Even if a Spaniard has never seen Spellbound or seen Dalí’s work, he or she has general knowledge of this part of Spanish cultural history. The Dalí museum is the second most popular tourist destination in Spain, second only to the Prado in Madrid.

Although Hitchcock sought out Dalí for reasons beyond the latter’s publicity value, an idea onto which Selznick immediately grasped, that there was a lot of mileage to be gained by the association with Dalí particularly in Spain, is undeniable. It went beyond the publicity for Recuerda (Spellbound). Dalí was called upon again for the launching of Vertigo in Spain, even though he could claim no direct credit for film’s artistic conception as he had received for Spellbound. The recent exhibition and book, edited by Matthew Gale, Dalí and Film lists Vertigo in ‘A Cinematic Cronology of Dalí 1941–1989’ (2007: 160–1) as one of the most important films Dalí saw in the late 1950s. It is not surprising that at least in Spain Dalí would make an appearance to support the film, for Vertigo’s nightmare sequence recalls the stylised fall in Spellbound’s dream sequence.