I. INTRODUCTION

Throughout the decades of Hitchcock’s career, the Mexican film industry constituted the strongest, most productive counterpoint to Hollywood in Spanish-speaking Latin America. As Paulo Antonio Paranaguá states in Tradición y modernidad en el cine de América Latina (Tradition and Modernity in Latin American Cinema, 2003), ‘the Mexican film industry was the principal cinematographic phenomenon in Latin America during the first half of the twentieth century; such primacy would belong to Brazil’s New Cinema in the second half’ (2003: 15). That its cinema represented a high level of expertise evoked considerable national pride in Mexico, often precisely because it kept the Colossus of the North at bay, although according to Seth Fein in ‘Myths of Cultural Imperialism and Nationalism in Golden Age Cinema’, during World War II the actual relationship was more ‘collaborative’ than confrontational.1 Regardless of the particularities of US-Mexican interactions at intergovernmental levels, the processes at play on screen signalled profound social changes. According to Jesús Martín-Barbero, Mexican cinema connected with ‘the hunger of the masses to become socially visible’ (1987: 181). Hitchcock entered the Mexican market as a wedge – associated with Hollywood because of English-speaking familiar stars, but different from Hollywood as a representative of British/European filmmaking. To look ahead in our study, the enduring importance of British Hitchcock, for which the Mexican director Guillermo del Toro expressed a specific preference in his book Alfred Hitchcock (1990), constitutes one of the most fascinating parts of the Mexican reception story. Furthermore given the early representational triangulation, how and when Hitchcock crossed over to represent Hollywood in Mexico also marks an important transition in Latin American film history that we will explore and interpret in this chapter.

Many scholars and critics, including Paolo Antonio Paranaguá, Carlos Monsiváis, Emilio García Riera and Guillermo del Toro to name just a few, have written extensively not just on Mexican cinema, but also on world cinema. However, while they place Hitchcock in a global perspective – understood here more accurately as universal or standardising – they have not addressed his reception within a specifically Mexican context. Del Toro, for example, never mentions any premiere of a Hitchcock film in Mexico nor does he cite any critic writing in Spanish. His references are French – Truffaut, Chabrol and Rohmer – and American – principally, Spoto – whom he is introducing to his Spanish-speaking audience. The Argentinean critic Nestor García Canclini, who works and publishes in Mexico, in his chapter on Latin American cinema in Diferentes, desiguales y desconectados: mapas de la interculturidad (Different, Unequal and Disconnected: Maps of Interculturality, 2004) notes that he never respected Hitchcock’s work until Truffaut wrote about him. As a response to García Canclini’s call to examine hybridity in local inflections of global popular culture, this chapter will explore the initial reception of Hitchcock’s films through a case study of their premieres in Mexico City.

Not only were most of Hitchcock’s films released in Mexico, first in the capital, but also they were commented upon contemporaneously within the context of a vibrant film culture, and within the context of local interpretations of world events. As Humberto Mussacchio documents in Historia del periodismo cultural en México (The History of Cultural Journalism in Mexico, 2007), the dialogue around cinema extended across diverse popular and literary magazines and included such titles as Revista Elhers in the 1920s, the sports magazine Esto and Cine Mundial from 1953, and the controversial Nuevo Cine in 1961, after which a veritable plethora of new film magazines appeared, Premiere, Cinemanía and 24 por Segundo, oriented towards the more commercial offerings, as well as Cine, Intolerancia Divina, Primer Plano, Nitrato de Plata and Estudios Cinematográficos of UNAM, which focused on art cinema as well (2007: 142–3). However, these journals and magazines appeared sporadically. In order to trace Hitchcock’s Mexican reception more consistently in its historical context, this chapter focuses on the two most important daily newspapers in Mexico City during Hitchcock’s lifetime, El Universal and Excelsior. Although both periodicals, which are still in existence today, received some government support, they were considered independent voices. By looking at film reviews, advertising and caricatures, as well as editorials and general reporting of news in these papers of record, our approach repeats the model of the Spanish case study of the Madrid newspapers ABC and Vanguardia in chapter one, and hence invites comparisons between Spain and Latin America. Furthermore, studying the initial reception history of Hitchcock’s films in Mexico City lays the groundwork for appreciating the context in which the contemporary Latin Hitchcock directors arose and for highlighting local differences. Subsequent chapters will explore whether the traits in evidence at the original release of his films found echoes in the work of later Latin American auteurs.

II. PREMIERE DATES AND A COMPARISON OF SPANISH TITLES

Knowing the dates for the premieres of Hitchcock’s films is a precondition for studying the reaction to them in a contemporaneous context, but this information is not easy to find. No searchable electronic database yet exists for any major Latin American newspaper for the period of Hitchcock’s career.2 These newspapers are only accessible on microfilm. Neither do the movie archives in the US where Hitchcock papers are held, the Warner Archives or the Academy of Motion Pictures Archives among others, have an independent record of release dates for Latin American capital cities. Thankfully, Mexico City is a singular exception because significant research supported by UNAM on film release dates has already been done on the capital.3 The following chart of premieres of Hitchcock’s films is based on the four-volume series of books Cartelera cinematográfica, which documents the release of films in Mexico City during the periods 1930–1939, 1940–1949, 1950–1959 and 1960–1969.4 Information for the original titles and premieres is from Jane E. Sloan, Alfred Hitchcock: The Definitive Filmography.

| Original Title |

Mexican Title |

Original Opening |

Mexican Opening |

Cinema in Mexico City |

| Champagne |

Champaña |

August 1928 |

4 April 1930 |

Cine San Juan de Latrán |

| The 39 Steps |

Treinta y nueve escalones |

Sept. 1935 |

14 Nov. 1935 |

Cine Palacio |

| The Secret Agent |

Cuatro de espionaje |

Jan. 1936 |

18 Sept. 1936 |

Cine Rex |

| Sabotage |

Sabotaje |

Dec. 1936 |

11 Feb. 1937 |

Cine Palacio |

| Jamaica Inn |

La posada madita |

May 1939 |

2 May 1940 |

Cine Alameda |

| Rebecca |

Rebeca |

March 1940 |

1 August 1940 |

Cine Alameda |

| Foreign Correspondent |

Corresponsal extranjero |

August 1940 |

23 Oct. 1940 |

Cine Alameda |

| Mr. and Mrs. Smith |

Casados y descasados |

Jan. 1941 |

12 April 1941 |

Cine Magerit |

| Suspicion |

La sospecha |

March 1940 |

25 Dec. 1941 |

Cine Olympia |

| The Lady Vanishes |

La dama desaparece |

Oct. 1938 |

16 July 1942 |

Cine Rex |

| Saboteur |

Saboteador |

April 1942 |

4 August 1942 |

Cine Teresa |

| Shadow of a Doubt |

La sombra de una duda |

Jan. 1943 |

8 April 1943 |

Cine Alameda |

| Lifeboat |

Náufragos |

Jan. 1944 |

4 Jan. 1945 |

Cine Alameda |

| Spellbound |

Cuéntame tu vida |

Oct. 1945 |

13 June 1946 |

Cine Alameda |

| Notorious |

Tuyo es mi corazón |

July 1946 |

12 Feb. 1947 |

Cine Alameda |

| The Paradine Case |

Agonía de amor |

Dec. 1947 |

24 June 1948 |

Cine Cosmos (inauguration); Orfeón |

| Rope |

La soga |

August 1948 |

19 May 1949 |

Cine Palacio Chino |

| Under Capricorn |

Bajo el signo de capricornio |

Sept. 1949 |

19 Jan. 1950 |

Cine Alameda |

| Strangers on a Train |

Pacto siniestro |

June 1951 |

7 Dec. 1951 |

Cine Alameda |

| Stage Fright |

Desesperación |

Feb. 1950 |

25 Dec. 1951 |

Cine Alameda |

| I Confess |

Mi secreto me condena |

Feb. 1953 |

30 Dec. 1953 |

Cine Las Américas |

| Dial M for Murder |

Con M de muerte |

April 1954 |

11 Nov. 1954 |

Cine Alameda |

| Rear Window |

La ventana indiscreta |

July 1954 |

5 May 1955 |

Cine Chapultepec |

| To Catch a Thief |

Para atrapar al ladrón |

July 1955 |

22 Dec. 1955 |

Cine Chapultepec |

| The Man Who Knew Too Much |

En manos del destino |

May 1956 |

8 Nov. 1956 |

Cine Chapultepec |

| The Wrong Man |

El hombre equivocado |

Dec. 1956 |

25 April 1957 |

Cine Las Américas |

| The Trouble with Harry |

Al tercer tiro |

Oct. 1955 |

25 April 1957 |

Cine Chapultepec |

| Vertigo |

De entre los muertos |

May 1958 |

5 March 1959 |

Cines Alameda y Polanco |

| North by Northwest |

Intriga internacional |

July 1959 |

2 Oct. 1959 |

Cines Roble y Ariel (prem); Roble (normal) |

| Psycho |

Psicosis |

June 1960 |

29 March 1962 |

Cine Chapultepec |

| The Birds |

Los pájaros |

March 1963 |

18 July 1963 |

Cine Chapultepec |

| Marnie |

Marnie |

June 1964 |

28 Jan. 1965 |

Cines Latino y Continental |

| Torn Curtain |

Cortina rasgada |

July 1966 |

2 Feb. 1967 |

Cine Chapultepec |

This information suggests that many of Hitchcock’s early British films – Woman to Woman, The Lodger, The Ring, Blackmail, Waltzes from Vienna, The Man Who Knew Too Much, Young and Innocent – which did open in Madrid, Spain, did not receive any comparable, contemporaneous screenings in Mexico. On the other hand, the early Sabotage, which did not open in Spain in its original version until 1983, was released more or less on schedule in Mexico in 1937.

The interval between the British or American release and the Mexican release is generally under a year for those films in the above chart. Subtitling, and later dubbing studios in Mexico efficiently prepared the copies for national release. Dubbing, initially called ‘duplicación’, was first introduced theatrically with the premiere of La Luz que Agoniza (Gaslight) starring Charles Boyer and Ingrid Bergman on 3 January 1945. According to the film scholar Fernando Peña, Gaslight was also the first film to appear dubbed in Buenos Aires.5 There are a few Hitchcock films that were released more than a year and a half after they opened in the US: Champagne, The Lady Vanishes, Suspicion, Stage Fright and Psycho. Why their Mexican release was delayed beyond a year merits further study, particularly in the case of Psycho, since it was an enormous box office draw in Spain where it opened much closer to the time of its US release.

For half of Hitchcock’s films the titles in Spanish are considerably different in Mexico and Spain, as the following chart illustrates:

| Original Title |

Mexican Title |

Spanish Title |

| The Secret Agent |

Cuatro de espionaje |

Agente secreto |

| The Lady Vanishes |

La dama desaparece |

Alarma en el expreso |

| Mr. and Mrs. Smith |

Casados y descasados |

Matrimonio especial |

| Spellbound |

Cuéntame tu vida |

Recuerda |

| Notorious |

Tuyo es mi corazón |

Encadenados |

| Under Capricorn |

Bajo el signo de capricornio |

Atormentada |

| Strangers on a Train |

Pacto siniestro |

Extraños en un tren |

| Stage Fright |

Desesperación |

Pánico en la escena |

| I Confess |

Mi secreto me condena |

Yo confieso |

| The Man Who Knew Too Much |

En manos del destino |

El hombre que sabía demasiado |

| Dial M for Murder |

Con M de muerte |

Crimen perfecto |

| The Wrong Man |

El hombre equivocado |

Falso culpable |

| The Trouble with Harry |

Al tercer tiro |

Pero…¿Quién mató a Harry? |

| North by Northwest |

Intriga internacional |

Con la muerte en los talones |

Generally one Spanish-speaking market opted for a more direct translation from English than the other. The exceptions – that is, those films whose Spanish titles highlighted different aspects of the respective films – were North by Northwest, whose narrative reference few English-speaking audiences understood, and Notorious. In these cases the Spanish-language titles referred to the respective genres. Correspondence in the Warner Archives at USC documents that there was considerable discussion within the studio over the choice of appropriate Spanish titles for these five films Hitchcock made for Warner Bros. – Rope, Stage Fright, Strangers on a Train, Dial M for Murder and The Wrong Man.

Of Hitchcock’s silent films the only one for which I have evidence of release in Mexico is Champaña (Champagne). It received no significant reviews. Its ads were positioned in Universal alongside of those for La dama más inmoral (A Most Inmoral Lady) and hence marketed like a version of the Follies Bergère, a type of live entertainment also found in Mexico City in the 1930s. Champagne was overshadowed, both in the placement of its ad in Universal, and in sensationalist, nationalist copy – ‘triumph of the language!’ – by the innovation of the day, Sombras de Gloria (Shadows of Glory, 1930), the first foreign-language feature produced in the US with live dialogue in Spanish. Nonetheless, the box office hit and most significant film of the day was the sound film directed by Alfred Santell El romance del Río Grande (The Romance of the Río Grande)(US, 1929), ‘an exceptionally beautiful plot developed in Mexico and among Mexicans in which our characters and customs are not ridiculed, but on the contrary are presented with complete justice compared to what has happened until now in cinema’ (Universal, 4 April 1930). It is certainly ironic that the first Hitchcock film to be promoted in Mexico City, as in Madrid, Spain, was the lightweight Champagne, whose plot and aesthetics Hitchcock himself scorned and whose reception was blithely removed from the cross-border developments of the day. However, if one pays attention to the immediate period of its release one notes how nationalist identity framed the reception of US cinema despite its transnational complexity and it allows one to understand how his more aesthetically significant movies of the 1930s were received as British once they were inserted into the narrative of Mexican history.

Sexy ad for Champagne with no mention of Hitchcock in El Universal (4 April 1930) but with the tagline ‘romantic story with exciting adventures in a torrent of champagne and love.’

III. HITCHCOCK’S BRITISH SPY FILMS: THE THIRTY-NINE STEPS, SECRET AGENT AND SABOTAGE AND THE NEWS OF THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR AND TROTSKY IN MEXICO

We tend to forget when we think of Hitchcock in terms of his most influential films, such as Vertigo and Psycho, that his British sound films of the 1930s – The Thirty-Nine Steps, Secret Agent and Sabotage – were spy movies that had at least a skeletal relationship to the geopolitics of the moment. From 1935 to 1937 a Hitchcock film opened annualy in Mexico City and was announced in the two major city papers against the backdrop of headlines of news of unrest, then war in Spain, that was to lead to the most important wave of Spanish immigration to Mexico since the Discovery of the New World or ‘the Encounter’.

In Mexico City in the 1930s there were already sizeable expatriate and business communities who were interested and involved in world events. Reflecting their presence as well as the proximity of the US, both El Universal and Excelsior carried a regular section in English that was not merely a translation of articles in the respective papers. In the 1930s the English section included cultural news, whereas in later decades it evolved into a current events synopsis with classified ads about accommodation. In El Universal, whose English section was called ‘News of the World’, columns about Hitchcock appeared on the front page of the English section alongside news of the Spanish Civil War. The rest of the paper in Spanish included different reviews and ads for his movies.

When The Thirty-Nine Steps, the first Hitchcock movie to receive major coverage in Mexico City, opened, Mexican movie theatres were in the midst of a fiscal crisis according to coverage in El Universal. Fewer European films, including Spanish films, were being made due to wartime conditions. To compensate theatrical runs were extended and the public’s interest would wane by the end of the run. As a sign of Mexican nationalism, the fanaticism for American/Hollywood stars was blamed, too, both for aberrations at the box office and for encouraging too thin a body type for women, whereas European movies were praised for representing a healthier body image. In 1935 to stimulate the film exhibition sector in Mexico a new law was passed that lowered taxes on film exhibition by sixty per cent. The law also included a new prohibitive tax on the importation of ‘discos para cinematógrafo’, or movie records, to force movie theatre owners to buy modern equipment to be able to show talkies. Some Mexican exhibitors resisted the equipment change since sound film stock deteriorated faster. Problems with new technology reoccurred as a theme in the published reports regarding Hitchcock, too. A Universal review in English for Woman Alone quoted Hitchcock imagining the sound equipment breaking down:

The creed that I chalk up in front of me today is that we are making motion pictures. Too many men forget that I try to tell my story so much so in pictures that if by any chance the sound apparatus broke down in the theatre, the audience would not fret and get restless, because the pictorial action would still hold them! Sound is all right in its place, but it is a silent picture training which counts today. (11 February 1937, Section 2: 8)

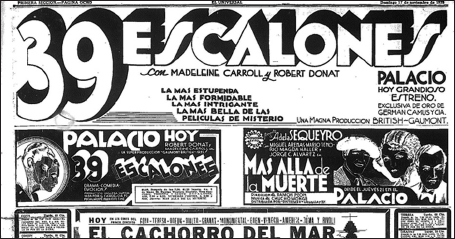

For Hitchcock the possibility of a technical glitch justified the primacy of the visual over the aural in ‘making a Hitchcock picture’. The 1935 film law regarding the modernisation of equipment implies that Hitchcock’s scenario had indeed occurred in Mexico. As a sound film and a British import The Thirty-Nine Steps represented a turn to the modern. Superlatives abound in the ad for the ‘mystery’ film, which was stylised in a black reverse image (Universal, 17 November 1935, Section 1: 8). El Universal film critic Fidel Solis felt the publicity hype proclaimed in superlatives in the ad was justified as he effusively praised the film:

39 Steps is an exciting film, full of mystery, with a great deal of subtlety to the action and plot.

But truly at this moment we can’t come up with the exact phrase to describe this movie. The word emotion is right when one speaks of 39 Steps.

Modern stylised reverse ad for The Thirty-Nine Steps in El Universal (17 November 1935).

It isn’t a concept most used in the publicity, but it’s a reality plastered all over the screen.

It succeeded – cleverly, with technical perfection – to follow the tangled action in an interesting way. It isn’t a crime film in which fantasy exchanges punches with reality, but rather it’s a logical process, stupendously realized in such a way that it holds the audience’s attention for extended periods.

The locations where the action unfolds, the characters, the photography, with great technical advances, all of this stands out in the film we are reviewing. (‘La pantalla y sus artistas’, El Universal, 17 November 1935, Section 1: 5)

Solis does not interpret The Thirty-Nine Steps as a solo directorial triumph for Hitchcock, who is never mentioned in the substantial featured review, but rather as a sign of the cutting-edge quality of British cinema in contrast to Hollywood’s product:

British filmmaking – in this new creative phase – is showing us its great advances. Its laboratories don’t produce crime films like those we’re accustomed to seeing from Hollywood, but rather film reels full of interest, with great visual attributes, with perfect coherence in all the scenes.

The objective of the production, so unexpected for the audience, is a demonstration of what cinema can achieve when one has such an attractive plot at hand as well as when one manages to find the exact manner to realise it. (Ibid.)

After praising the acting, too, Solis concludes by again identifying The Thirty-Nine Steps as ‘a demonstration of the progress of British cinematography’ (ibid.).

Cuatro de espionaje (Secret Agent) was Hitchcock’s next film to open in Mexico City. When it premiered in September 1936, it had stiff competition from MGM’s Academy Award-winning Motín a bordo (Mutiny on the Bounty, 1935) at whose opening night gala British and American ambassadors appeared. Next to Spanish War News telling of the defence of Madrid and the rebel occupation of San Sebastián, Cuatro de espionaje received coverage with articles both in Spanish and in English. John Gielgud, who was featured throughout, lauded ‘Alfred Hitchcock’s brilliant technique’ in direction (El Universal, 19 September 1936, Section 2: 8) but none of the other coverage mentions Hitchcock. The review, though not on the society pages, assumes that tone: ‘An exclusive audience filled the hall of the elegant theatre on Madera Avenue, and the movie was very entertaining’ (ibid). The ad for the film showing the aerial bombing of a train as well as the embrace of the male and female spies along with the line ‘The most passionate and strange film that has been made to this day’ seems to indicate that the film defied generic classification.

Wartime advertising of Secret Agent in El Universal (19 Sept. 1936).

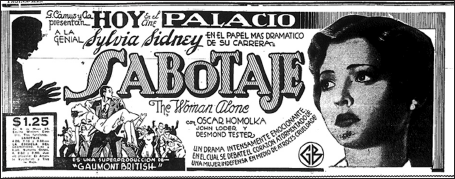

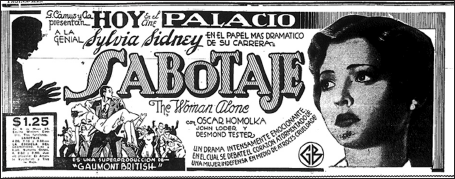

When Sabotaje, promoted bilingually with the US English title Woman Alone in Mexico, not the UK original title Sabotage, opened in Mexico on 11 February 1937, to the day’s headline of ‘Alcalá de Henares Bombed’, it was advertised as a war movie. Several articles that day speculated about Germany’s intentions to invade Poland imminently. For the first time in the Mexican promotion and reception of his films, Hitchcock’s name now figured front and centre in the coverage. Internationally, Sabotage was one of the more controversial of Hitchcock’s movies because of his manipulation of the audience’s reactions through suspense. In the film a twelve-year-old boy unwittingly carries a bomb that goes off and kills him. To recall Sabotage in more detail, Madame Verloc and her husband run a movie theatre, his cover for his anarchist political activities. In an act of sabotage the power goes out across the city of London and customers angrily demand their ticket money back. When Mr. Verloc comes under scrutiny of Scotland Yard, and their undercover agent Ted who is falling in love with Mrs. Verloc, Mr. Verloc hands the task of delivering a package with a ticking bomb along with film canisters to Mrs. Verloc’s young brother Stevie. The boy’s errand is so fraught with delays that the package explodes and kills him. At dinner Mrs. Verloc intuits her husband’s guilt and kills him with a knife. An explosion of another bomb, hidden in a birdcage in their apartment, destroys the evidence of her crime.

Hitchcock later admitted to Truffaut that making a child die in a picture was ‘a grave error’. He elaborated:

I made a serious mistake in having the little boy carry a bomb. A character who knowingly carries a bomb around as if it were an ordinary package is bound to work up great suspense in the audience. The boy was involved in a situation that got him too much sympathy from the audience so that when the bomb exploded and he was killed, the public was resentful. (Truffaut 1984: 109)

Yet none of the contemporary Mexican newspaper criticism of Sabotage criticised the plot, or the killing of a child. In fact, like Guillermo del Toro who wrote in 1992 in Alfred Hitchcock, republished in Hitchcock por Guillermo del Toro (2009), ‘of having made purée out of Verloc’s little brother-in-law … for me personally it is one of the film’s greatest achievements’ (2009: 81), the reviews celebrated the tension created in the film. The Excelsior review, entitled ‘The Movie “Sabotage”: Indelible Impressions on the Soul’, praised the film, and British cinema in general, for its economical but effective exposition, including the child’s fateful mission:

With an entirely British reserve, with an atmosphere of crime, of mystery played out through the facial expressions and technical artistry of the principal actor Oscar Homolka, the movie Sabotage deserves to be given a top ranking. It doesn’t have the popular tricks of most crime films. It reaches the soul of the spectator in ways that are natural and humane, such as in that scene of wandering through the streets without knowing that he is carrying a deadly bomb, which creates moments of intense emotion. Nonetheless, the technique is simple, but it causes remarkable effects. (Excelsior, 12 February 1937: 6)

The only criticism the reviewer has is that Mrs. Verloc does not cry more over her brother’s death, but rather impassively kills her husband: ‘The scene of the murder of her husband is carried out with a masterful hand, and it is a shame that the suffering for the death of the younger brother is not shown in those moments. It isn’t the fault of the actress, but of the situation’ (ibid.). Perhaps a Mexican interpretation required more melodrama, a good cry over the little brother. Yet overall the reviewer judges the film ‘a good type of sensationalism, of those which enslave the audience, such that no one can take his eyes off the screen, which is the great secret of good movies’ (ibid.). Indeed Sabotage was judged to be setting the standards for contemporary cinema. Excelsior’s English reviewer gives particular credit to the director by name: ‘Again must the reviewer pay his compliments to director Hitchcock who seems to have that master’s touch in bringing to the screen real people with appropriate sets and surroundings. “The Woman Alone” is a vital and human document’ (Excelsior, 12 February 1937). It occasioned the publication in the English section of Excelsior one of the most comprehensive presentations of Hitchcock’s cinematographic philosophy found at any time in these newspapers. In the article, ‘Thorough Emotional Shake-Up is What Alfred Hitchcock Aims to Give Public in His Thrillers’, Hitchcock notes the importance of comedy in the film’s balance:

Next to reality, I put the accent on comedy. Comedy, strangely enough, makes a film more dramatic. A stage play gives you intervals for reflection on each act. These intervals have to be supplied in a film by contrasts, and if the film is dramatic or tragic, the obvious contrast is comedy. (Excelsior, 11 February 1937, Section 2: 8)

This pronouncement on the importance of comedy in a film’s balance becomes one of the key tenets of Hitchcock’s Latin reception from the 1990s onwards. Likewise in the film review in Universal, ‘La pantalla y sus artistas’ (‘The screen and its artists’), which appeared next to even more extensive coverage of bullfighting, Fidel Solis remarked on the public’s enthusiastic response at the film’s premiere and noted: ‘With this film [Hitchcock] has crystallised his great knowledge of technique as a director … The principal characteristic of this film lies in the excellent interconnections achieved in order to present … a harmonious whole, blending the tragedy of passions with human suffering’ (Universal, 15 February 1937). Putting this review next to bullfighting coverage may be one of the most appropriate placements for any review of this film. Hitch felt the ‘best scene’ was Mrs. Verloc’s killing of her husband. Truffaut compared it to the dramatic process of Mérimée’s staging of Carmen’s death, ‘with the victim thrusting her body forward to meet the slayer’s final stab’ (1984: 110); Hitchcock concurred and explained how he created the scene’s tension around the attraction of the knife. Hitch makes Mr. Verloc seem like the bull in his description:

Verloc stands up and walks around the table, moving straight toward the camera, so that the spectator in the theater gets the feeling that he must recoil to make way for him. Instinctively, the viewer should be pushing back slightly in his seat to allow Verloc to pass by. Afterward, the camera glides back toward Sylvia Sidney, and then it focuses once more on the central object, that knife. And the scene culminates, as you know, with the killing. (Truffaut 1984: 111)

Hitchcock felt it was important that Sylvia Sidney not show her inner feelings on her face. Perhaps for this reason, critics, including Solis, had a hard time reading her. Solis makes one of the strangest comments anywhere about Sidney, noting her ‘extraña atracción mezcla de china y europea’ (‘strange attraction [due to her] mixture of Chinese and European [looks]’) (ibid.). This is bizarre ethnic stereotyping, but less cruel than Truffaut’s later observation that the actress reminded him of Peter Lorre because of her eyes (ibid.).

On less of a tangent, Solis nonetheless agreed with what Hitchcock left out of the adaptation from Conrad’s novel: ‘In the film adaptation it was necessary to eliminate superfluous material, and in so doing the work turned out perfectly balanced’ (Universal, 15 February 1937). This directly conflicted with Jorge Luis Borges’ view of the film that appeared in Sur, one of Borges’ rare film reviews in that journal, and only one of two of Hitchcock’s films. Borges pithily and dismissively opined, ‘Destreza fotográfica, torpeza cinematográfica: tales son los juicios tranquilos que me “inspira” el último film de Alfred Hitchcock’ (‘Photographic skill, cinematographic blunder: such are the assured judgments that the latest film of Alfred Hitchcock “inspires” in me’).6 Overall Solis saw Hitchcock’s films, as British products, as economical in their exposition. Borges, on the other hand, expressed a more conservative, literary view and preferred Conrad’s novel.

The headlines during Sabotage’s run described the siege of Madrid. On February 12 the main news was ‘All Foreigners Can Leave Madrid’. Yet in the mid-1930s Mexico had its own share of clandestine activities going on that were intertwined with the actions in Europe. The very week of Sabotage’s Mexican City opening Trotsky began his exile there. Excelsior’s coverage of Trotsky’s arrival, which Mexico City denizens excitedly followed, was extensive. Although Trotsky spoke of freedom, as Excelsior headlined its interview with him ‘Trotsky now knows what freedom is’ (12 January 1935), he and his family still faced peril and continued pursuit. Three days before Hitchcock’s Sabotage opened in Mexico City, El Universal reported on its front page that Trotsky’s son Sergio was arrested without known cause. On 10 February, the day before the film’s opening, a headline read ‘Trotsky “Disappears” While Audience in Hippodrome Waits’. The lack of explanation for these events only underscored for the general reader or potential moviegoer their probable connection to Mexican and European intelligence activities. On the day after Sabotage opened, a regular cultural column in Excelsior, ‘Ayer, Hoy y Mañana’ (‘Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow’) gave a particularly Mexican spin on sabotage in its commented on the long delay before Trotsky’s appearance at the Hippodrome lecture, then known to have occurred because he was waiting for a phone call:

Ad for Sabotage/The Woman Alone from Excelsior, showing the foreign look of the actress Sylvia Sidney.

Wartime framing in the ad for Sabotage/The Woman Alone in El Universal.

There is no mystery about why Trotsky wasn’t able to talk on the phone with his New York supporters the night of the announced speech. Managers of the telephone company are clarifying things, by saying the following, ‘Some machines on the line weren’t working right. There wasn’t any sabotage or intervention of any kind. It was only a technical defect in the main office in Mexico. When it was fixed it was too late to continue. It was nothing more than one of those unfortunate things that go wrong at the most inopportune time.’

That is to say, ‘things’ happened the Mexican way. There was a blunder [torpeza], that’s the way the failure is explained.

The public here is already accustomed to ‘the lines are not working right,’ precisely when they ought to work well; but for people in New York these ‘things’ aren’t understandable. (Excelsior, 12 February 1937: 5)

Through the Trotsky commentary Sabotage became associated with Mexicans’ gripes about their inferior phone system. This Hitchcock film vividly demonstrates how different Hitchcock’s initial reception was in Latin America. Not only did Sabotage become enmeshed in a historical/political narrative, but also many key elements of Hitchcock’s aesthetic reception in Mexico came to light through it: the recognition of the place of comedy in his films, as well as the foreshadowing – in the lament over the impassive, perhaps Asian Mrs. Verloc – of the filter of melodrama through which Hitchcock’s movies of the 1940s and 1950s were seen.

IV. HITCHCOCK’S FILMS OF THE 1940s AND EARLY 1950s: FLYING DOWN TO MEXICO CITY, JOUSTING FOR A PLACE WITHIN THE GOLDEN AGE OF MEXICAN CINEMA

How was the reception of Hitchcock’s films unique to Mexico in the 1940s and 1950s? Did his move to Hollywood have an impact, and if so, when? These decades coincided with the Golden Age of Mexican cinema, although scholars vary in setting its exact parameters.7 Internationally Mexico exported its films throughout the Western hemisphere and challenged Hollywood’s hegemony. Domestically the rise and evolution of Mexican cinema, particularly in a growing acceptance of a capitalist model, and in its aesthetics, which showed an increased emphasis on melodrama, strongly affected the reception of Hitchcock’s films during this period. Carlos Monsiváis interprets the place of melodrama in these dynamics:

The founding project of the Mexican cinema was the ‘nationalisation’ of Hollywood. Although imitation was unavoidable, differences between the two industries abound. For example, certain Hollywood genres were impossible to translate: the screwball comedy, the thriller and, in the last instance, the western. Melodrama was more important in Mexico than in the USA because, traditionally, Mexican popular culture is premised on the perennial confusion between life and melodrama and the corresponding illusion that suffering, to be more authentic, must be shared publicly. (1995: 117)

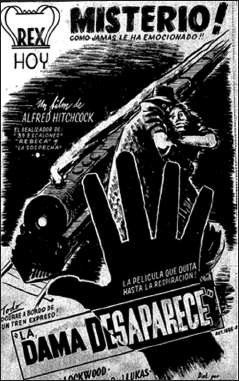

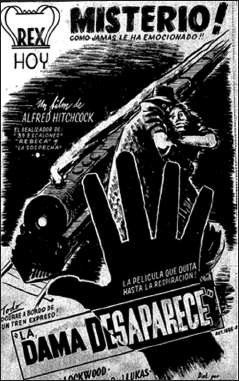

Though Monsiváis’s thesis describes how Mexican cinema selectively adapted Hollywood genres, it could equally be applied to explain how Hitchcock’s films during the Golden Age were positioned generically for a Mexican audience. When Hitchcock’s La dama desaparece (The Lady Vanishes), which was still one of his British spy period films that preceded his move to Hollywood, opened in Mexico in the early 1940s, generically it was given a different treatment than his other British films had received. By the time that The Lady Vanishes opened, Hitchcock had already moved to Hollywood and Mexican cinema was in its ascendance. Although the ad in Universal on 16 July 1942 promised a sensationalist mystery film, with Hitchcock’s name prominent in the selling, the featured review in that same paper, entitled ‘Cuando un joven penetra a la alcoba de una dama’ (literally, ‘When a young man penetrates a lady’s bedroom’), was about sex and social mores, a version dripping with melodrama. The ad came from the main office; the review copy was local.

One of the more important ways to gauge the Latin reception of Hitchcock is to study how his move to Hollywood was framed, especially to note when this move to become what we now call a crossover director was celebrated. The marketing of The Lady Vanishes only reveals a small part of the overall picture. As seen in chapter one, in Spain Rebecca was the flashpoint for a celebration of modernising aesthetics and for a debate over questionable morals. Yet in Mexico City newspapers Rebecca barely caused a stir. There were ads but it did not receive any commentary either in Universal or Excelsior. On the other hand, Casados y descasados (Mr. and Mrs. Smith), a comedy regarded today as one of his lesser films, Hitchcock’s second film after Rebecca, was the centrepiece of a huge event that transformed his reception in Mexico and definitively associated him with Hollywood. Mr. and Mrs. Smith premiered on 12 April 1941, Sábado de Gloria (Easter Saturday) and opened to the general public on Easter Sunday. The religiosity of Mexicans was reflected in the titles of other movies that opened during the same Easter period: Creo en Dios (Believe in God) by Fernando de Fuentes, and even El cielo y tú (All This and Heaven Too) starring Bette Davis and Charles Boyer. Mr. and Mrs. Smith fell from above as their secular counterpoint. Universal’s headlines read, ‘A Rain of Stars Fell Upon Mexico Yesterday’ with the subtitle ‘Existe una vía rápida de conexión’ (‘There’s a rapid air connection’). Three Pan Am planes filled with Hollywood stars flew down in a trip that lasted only twelve hours to inaugurate the air connection between Mexico City and Los Angeles. Both major newspapers covered their stay for days with copious photos and lists of the stars. For Universal the event presaged the rise of international tourism: ‘The transcendence of this trip is enormous if one takes into account that it shows in the US the existence of a rapid route to connect the two countries and with this the advantages for international tourism become abundantly clear’ (Universal, 12 April 1941). Although the stars’ official programme included High Mass at the Cathedral, the main event was a reception at the Cine Magerit where the programme for the stars featured the premiere of Mr. and Mrs. Smith.

Mystery like you’ve never felt it before, it will take your breath away: Sensationalist ad for The Lady Vanishes in El Universal (16 July 1942).

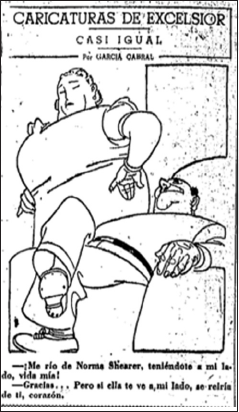

Allusions to the film’s plot were woven into the coverage. For instance, the public was compared to ‘los descasados’, or the unmarried, for they were as impatient waiting for the stars to appear as Mr. and Mrs. Smith were acting out their marital disagreements: ‘This same public showed signs of impatience to see the “luminaries” of North American cinema as soon as possible’ (ibid.). When the stars finally came out, Mickey Rooney tried to speak Spanish, and Norma Shearer made the crowd swoon. Excelsior reported on 13 April, ‘Norma Shearer Conquered the Sympathies of the Metropolitan Public through her Refined Manners’; on 14 April 1941 the exchange, and the consciousness of Hitchcock’s film in a Mexican context, even made it into the featured satirical cartoon in the Excelsior, a fixture of the editorial, on page 4, in which Mr. and Mrs. Smith became a long-time Mexican married couple sniping at each other. The husband sinks back in his easy chair and wistfully remembers the Easter weekend, ‘Me río de Norma Shearer, teniéndote a mi lado, vida mía’ (‘I’m laughing at Norma Shearer, having you by my side, my dear’). The wife retorts, ‘Gracías … Pero si ella te ve a mi lado, se reiría de tí, corazón’ (‘Thanks … But if she sees you by my side, she’d laugh at you, sweetheart’). The events of this Easter weekend helped define radical cultural changes. Whereas one part of the city reenacted ‘The Traditional Burning of Judas’, another new movie theatre, Cine Estrella, with the cutting-edge kinetoscope technology was ‘presented to the Mexican people’. Mexicans celebrated their progress and global connections. Although Hitchcock himself was not on any of those planes flying down to Mexico City, his boss David O. Selznick was. It was this publicity event, and the self-imaging of Mexicans in the comedy Mr. and Mrs. Smith, that shows first, that Hitchcock in 1941 was seen as representing Hollywood, and then, that his films were integrated into a contemporary Mexican narrative, too.

A list of the visiting stars and Hollywood bigwigs headed the ad for Mr. and Mrs. Smith in Excelsior (12 April 1940).

Garcá Cabral’s cartoon ‘Casi igual’ (‘almost equal’) in El Excelsior satirizes the typical Mexican couple by referring to the visit of the Hollywood star Norma Sherrer.

Nationalist discourse in the 1940s celebrated innovation, particularly technical advances, such as regular air connections. In contrast to Spain’s main newspapers of this time, ABC and La Vanguardia, which carried conventional movie reviews on a regular basis, film commentary during this same period was more truncated in Universal and Excelsior and seldom rose to the level or length of what could be called a review. Instead, brief paragraphs captioned stills from the featured films. Newspaper reporting on cinema primarily took two forms – either political or policy news that affected the film industry, which often appeared on the front or editorial pages, or in Universal a regular column called ‘Nuestro Cinema’ (‘Our Cinema’) penned by the pseudonymous Duende Filmo, roughly ‘Film Phantom’. In both cases, and as the title ‘Our Cinema’ indicates, the perspective was nationalist. Hence when El Duende Filmo wrote about Hitchcock, which he often did, he represented a localised reception of Hitch’s filmography.

From the point of view of the papers of record during the Golden Age of Mexican cinema, where Hitchcock’s films opened was as significant, or more so, than their content or aesthetics. This tendency skewed the coverage and made the appraisal of his films considerably different than how world film history now generally evaluates his films and ranks them according to importance.

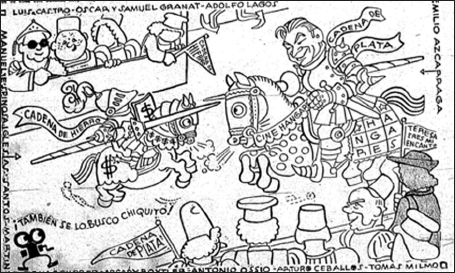

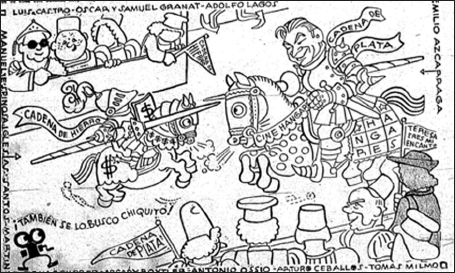

Not only did Mr. and Mrs. Smith take top billing as we have seen, about which Robin Wood opined: ‘Even the most dedicated auteurist is unlikely to claim it among Hitchcock’s successful, fully realized works’ (2002: 247), but perhaps even more surprisingly, so did Agonía de amor (The Paradine Case). McGilligan calls this film ‘a lifeless picture’ and ‘a permanent loser’ and quotes Gregory Peck, one of the film’s stars, who said it was the picture of his that he’d ‘like to burn’ (2003: 396). Again the film’s Mexican title, literally ‘Agony of Love’, evokes melodrama, whereas the English title sounds like a spy story. There were also full-page photo shoots of Louis Jordan, Agonía de amor’s leading man, an unusually strong ad presence. Importantly, the film inaugurated the Cine Cosmo. Full-page ads congratulated the owners with stylised letters, ‘for having provided our capital with a movie theatre worthy of it due to its sumptuousness, splendid comfort and capacity’ (Universal, 24 June 1948). It even had a car park, an American phenomenon. As El Duende Filmo explained in ‘Nuestro Cinema’, however, the Cine Cosmo represented an exhibitors’ war, in which Cine Cosmo was the opening salvo from the upstart ‘Cadena de Hierro’ (‘Iron Chain’) as seen in this caricature of a joust that accompanied his article (El Universal, 26 June 1948). Hitchcock’s films until then usually opened at the Cine Alameda. The Alameda was part of the Cadena de Plata or Silver Chain owned by Emilio Azcárraga Vidaurreta, depicted in the cartoon as the opposing knight. Azcárraga, a true media mogul, was a major investor in RKO in Mexico. He founded and until his death in 1972 headed up Televisa, Mexico’s pre-eminent television network throughout the twentieth century. It remained a family fiefdom.8 Hitchcock did not alienate Azcárraga. His films never played the Cosmo again but continued to premiere at the Alameda and other Mexico City movie theatres.

The Knight of the Silver Chain of movie theatres and founder of Televisa, Emilio Azcárraga Vidaurreta, charges in a joust against the Knight of the upstart Iron Chain in a political cartoon in El Universal (26 June 1948).

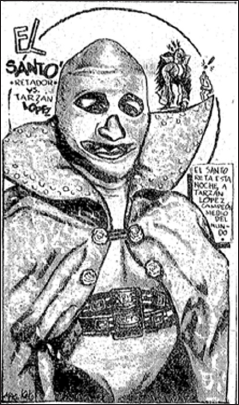

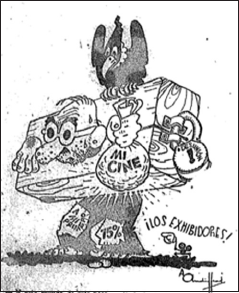

Many other industrial changes – and resentments – affected the positioning of Hitchcock in Mexico. When Sombra de una duda (Shadow of a Doubt) opened at the Alameda on 8 April 1943, the big story that whole week was that Bette Davis was vacationing in Acapulco. In other theatres María Félix in María Eugenia and Pedro Amendáriz in Soy puro mexicano (I’m a Real Mexican, 1942) enjoyed successful runs. The Coliseo arena, a new venue constructed specifically for Mexican wrestling contests, had just opened three days before with a world championship fight between El Santo and Tarzán, as seen in this illustration (El Universal, 5 April 1943, Section 1: 14). El Duende Filmo admitted he had not yet seen Shadow of a Doubt, but he recommended it nonetheless because of Hitchcock’s reputation ‘even though this Phantom hasn’t seen it the film is one THAT SHOULD BE SEEN because the director is Alfred Hitchcock, creator of Rebecca and Suspicion’ (El Universal, 8 April 1943). Yet the film industry was in turmoil. Excelsior editorialised against members of the cinematographic unions committing acts of sabotage, damaging the films they were showing, and against Hollywood for sending too many war movies. Ironically there was high demand but a scarcity of movies to fill all the venues, particularly the second-run theatres. El Duende Filmo predicted, ‘El derrumbe de los salones de cine se vislumbra’ (roughly, ‘the collapse of movie theatres is on the horizon’). Moreover in ‘Nuestro Cinema’ he railed against the exploitation of Mexico City exhibitors whom he depicted as captives of foreign/Yankee distributors and price collusion:

National movies have begun to create a following for the movies among people who before used to look at this entertainment with indifference, which has benefitted foreign movies. The Yankee distribution companies are opening annexes in strategic cities of the Republic and send back huge sums of money to their main offices in New York. They justify their attitude because there is a national distribution company, overseen by an Israeli who is notorious for his abusive practice of taking 75% off the top of ticket sales for their films. (El Universal, 4 April 1943)

Advertisement for the Mexican wrestling championship bout between El Santo and Tarzán that inaugurated the Coliseo Arena in El Universal (5 April 1943).

The anti-Semitism of the comments is striking. If the exploitation of exhibitors were not enough, however, the US had already begun to ration virgin film stock across all of Latin America. In Mexico this situation not only limited the number of movies made but also led to a government decree that only movies with Mexican themes could be made. The juxtaposition of the ads for Sombra de una duda (Shadow of a Doubt) and Soy puro Mexicano (I’m a Real Mexican), in which their respective casts moreover face opposite directions, gave El Universal readers a sense of the nationalist tension in the air (4 April 1943, Section 2: 6).

Political cartoon depicting the fate of ‘Our Cinema’ held prisoner to foreign exhibitors who take 75% of the box office in El Universal (4 April 1943).

By the time Hitchcock’s next movie Naúfragos (Lifeboat) opened in Mexico City the news again was ‘Lowered production of national movies – the US has reduced its shipment of raw material by 30 per cent’ (El Universal, 5 April 1945). The paper editorialised ‘Danger for National Cinema’. Neither Hitchcock’s aesthetics nor the film’s plot received any attention. It is ironic that these newspapers so decried the cutbacks in film stock shipments to Mexico without mentioning the hemispheric politics, for Mexico received more such material than any other Latin American nation. In fact, as Seth Fein points out, US foreign policy was directly intervening to develop the Mexican film industry as a ‘counterweight to Argentinean production’ in an effort to block the possibility of Axis propaganda originating from Argentina (2001: 167). Yet the often myopic nationalist discourse of the war years did acknowledge one new technological development positively. The day after Lifeboat opened on 4 April 1945 so did La Luz que Agoniza (Gaslight) with Ingrid Bergman and Charles Boyer that was ‘all in Spanish, no subtitles’. Patrons were asked to vote on whether they liked ‘duplicación’ – dubbing – or not. El Duende Filmo devoted two columns to the subject concluding that the experiment ‘ha ido de perlas’ (literally, ‘had a pearly start’) or went superbly. Subsequently Hitchcock movies were shown dubbed, too.

Casts for Shadow of a Doubt and I’m a Real Mexican face off in opposing ads in El Universal (4 April 1943).

The presence of Ingrid Bergman in his next film, Cuéntame tu vida (Spellbound) was exploited way beyond the star discourse for any other of his films in Mexico. Unusually for the serious newspapers at the time there were full-page fashion spreads for local stores that promoted the film and her image as appropriate for the Mexican woman. Ironically Bergman is not glamorous in Spellbound; she dresses like the psychiatric doctor she plays. Generally, and certainly now in the Costume Museum in Madrid, Bergman is seen as a fashion plate in Notorious or Tuyo es mi corazón, but when that film opened in Mexico City in 1947 it received no fashion coverage. Spellbound received feature commentary in El Universal and had a long run in Mexico City. But unlike in Spain, Dalí’s participation was never mentioned.

Another example of the way in which the Mexican reception of Hitchcock’s films of the 1940s and 1950s differs from than of Spain, for example, is seen in how Para atrapar a un ladrón (To Catch a Thief) was discussed in 1955. In Europe and the US To Catch a Thief, since it was set on the French Riviera and starred the glamorous pair of Grace Kelly and Cary Grant, represented a moment to advertise luxury. These aspects were crammed into the newspaper ad, which appeared both in Universal and Excelsior (20 December 1955). Yet whereas the ad touted cinematographic innovation, star power and romance, the newspaper review expounded on the topic of thievery. El Duende Filmo began his ‘Nuestro Cinema’ column in which he commented on To Catch a Thief recalling how honeymooning tourists had been assaulted in Mexico City:

Ad for To Catch a Thief in El Universal touts an exotic setting, cinematographic advances, star power and romance.

You will remember not so long ago that there appeared in the police blotter the notice of a scandalous assault, which a pair of newlyweds were victims of robbery, in the outskirts of Teotihaucán, when in broad daylight two hoodlums led by a woman, climbed into the car of the frightened North Americans and made them return to the city to their lodging on a very busy street where they were staying. The husband stayed in the car under the guard of the woman and one hoodlum, while the other one went up to the rooms with the wife to get the money. Certainly there must have been some among you who upon reading this news must have thought that the tourists who were robbed were spineless and that they let themselves be easily intimidated, because how could it have been that they didn’t call out for help anywhere along the way, when they passed by a policeman or when they were in the midst of so many cars? (El Universal, 20 December 1955, Section 1: 5)

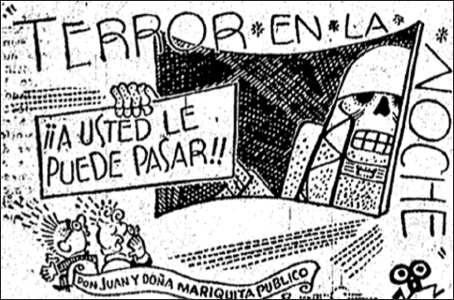

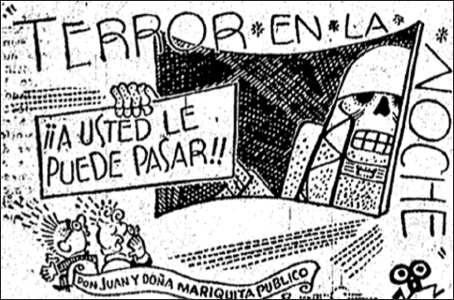

Letting his readers imagine themselves as tourists abroad, he then suggested their experience seeing the movie Terror en la noche (Terror by Night, 1946) would be ‘a similar assault’. He ended the piece giving his opinion on Hitchcock’s film about a robbery at a tourist spot – not as good as Rear Window or Rope. What constitutes at best a superficial appraisal of To Catch a Thief also exposes continued fissures around the legacy of Miguel Alemán Valdés (Presidential term, 1946–1952) who endeavoured to consolidate and modernise Mexican tourism, having come to the Presidency from the Ministry of Gobernación that supervised national tourism.9 By the mid-1950s the scenario of movie-going, if not tourism, was a generalised consumer behaviour for the Mexican Don Juan and Doña Mariquita Public. Hitchcock was enveloped in the discourse and was key to the experience.

It can happen to you, Don Juan and Doña Mariquita, Public!: Illustration to accompany El Duende Filmo’s review of Terror by Night and To Catch a Thief in El Universal (20 December 1955).

V. HITCHCOCK’S FILMS OF THE LATE 1950s AND 1960s: STANDARISED PUBLICITY WITHIN A NEW MORAL CODE AND LOCALISED EXPRESSIONS OF FEAR

In the late 1950s and 1960s the marketing and discussion of Hitchcock’s films in Mexico in both El Universal and Excelsior followed a more standardised global model that took its cues from Hollywood. Although Hitchcock continued to be touted as an example of the latest advances in technology, Vistavisión and Technicolour, which had not yet penetrated Mexican national cinema, there was less variance from the now standarised judgement and publicity line that Hitchcock was ‘el amo del suspenso’ (‘the master of suspense’). Little direct mention was made of either humour or melodrama. His films became bound to comments on terror and suspense, which had appeared in a more arbitrary, but localised fashion regarding Atrapar a un ladrón in El Duende’s discussion of tourist assaults. These papers featured production stills or well-known publicity photos, such as the famous stills of Hitch holding birds, before and during that particular film’s theatrical run. However, their captions did hint at a more local history. They noted the long lines at the theatres or tellingly lamented that the films had only opened in Mexico after a considerable delay.

Nonetheless three films in particular – En manos de destino, Psicosis and Los pájaros – received more specialised attention and generated a more local commentary. En manos del destino (The Man Who Knew Too Much), Hitchcock’s remake of his 1930s spy film, opened in Mexico at the same time as a major reworking of the Mexican movie code. The new ‘C’ classification for adult films was controversial. Excelsior published extensive excerpts of a letter from Luis B. Varela, President of the Mexican Institute of Intellectuals entitled ‘Nos Están Moralizando’ (‘They are moralising us’). Varela derided the new code as a symptom of a widespread moralising atmosphere:

Recently all entertainment venues are broke because of this so-called moralisation of the environment. National cinematographic production is stalled and it’s boring with traditional charros, mariachis, fairs and country ballads. There’s enough material to make something great, but we’re frozen. For this reason the audience is still literally cramming itself in to see the mutilated films that come to us from abroad in spite of the fact that the budget-minded censors leave them in an artless condition. (Excelsior, 8 November 1956)

Varela further deems the new movie code unnecessarily puritanical. He compares the situation to Prohibition in the US, a misdirected experiment only befitting the United States that fomented tourism to Mexico.

In Mexico alcoholic intoxication is not subject to censorship; everyone can drink until they drown. On the other hand, the angle ‘of the different vision,’ the ocular and auditory relaxation that doesn’t intoxicate anyone, finds itself strictly censored and rationed by the organisms that acting like a mafia are trying to brainwash the minds of the race with paralysing shots of stupidly ‘redeeming’ mescaline. (Ibid.)

Eschewing the alcoholic analogies, El Duende Filmo in El Universal nonetheless shared Varela’s views against the new censorship standards. Writing his ‘Nuestro Cinema’ column about Los Amantes (The Lovers), the first Mexican film to receive the new ‘C’ classification – ‘which shows danger and indicates that only those adults who may wish to risk contamination with immorality ought to see them’ – El Duende argues for the artistic merits of the film, which deals with prostitution, but decries the salaciousness of the publicity campaign for the film.

What bothers me is that in the ads that they make for the film good taste gets lost in order to attract the public’s attention. The chords of morbid curiosity are strummed by underscoring that special classification of the Directorship of Cinematography and by noting that people are scandalised, but it doesn’t take away the desire to go see what scandalised the censor. For a movie like ‘The Lovers,’ which is a work of art, the appropriate publicity ought to be different although it may not get the market results that are sought after. After all how the movie is sold resembles how its protagonists traffic in love. (El Universal, 13 November 1956)

The movie ads on 8 November 1956, the day The Man Who Knew Too Much opened, illustrate El Duende’s point about creeping salaciousness in advertising. The ads all included their classifications. Those for Las zapatillas verdes (The Green Slippers) and Los Héroes Están Fatigados (Les héros sont fatigués, 1955) with María Félix and Yves Montand, as seen below, suggest a Mexican celebration of eroticism. The contrast in modesty could not be greater with the publicity for En manos de destino (The Man Who Knew Too Much) with Doris Day and James Stewart, as parents searching for their kidnapped child. Hitchcock was touted not only as the latest in technology, for Vistavision and Technicolour, but also as recommended family entertainment. This attitude contrasts with his positioning in Spain during the 1950s that emphasised how he tweaked the censors.

Provocative ads in El Universal for Los zapatillos verdes and Les héros sont fatigues with the rating code ‘C’ (8 November 1958)

The publicity campaign for Psicosis (Psycho) in Mexico carried through with the innovative, though globally standarised, warning that latecomers would not be admitted to the theatres, although sometimes with Hitchcock’s softer admonishment:

You don’t begin a book at the end, or dinner with dessert and Psycho is a genuine banquet of emotions. My aim is, naturally, to help you to deeply enjoy this movie. See it from the beginning!

Psycho’s admonishment or change in exhibition rules was not discussed. What was in the news – ‘La permanencia voluntaria queda abolida’ (‘Voluntary stay is abolished’) – was that Spartacus (1960), an unusual 70mm film, would only be shown in two screenings with an hour to empty the theatre between them. Also tickets would be available four days in advance. Apparently in Mexico City the problem was not that moviegoers arrived late, but that they stayed on.

Shocked parents, Doris Day and Jimmy Stewart, in the ad for The Man Who Knew Too Much, appropriate for adults and children (El Universal, 8 November 1958)

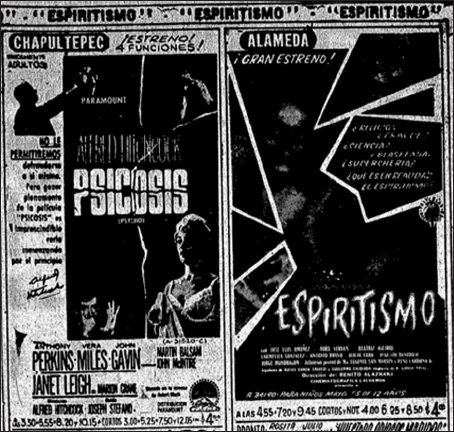

If on the one hand Psycho was overshadowed in exhibition rules by the luxurious exclusivity of Spartacus, it was even more significantly coopted by two other Mexican contexts. It was paired in ads and reviews with the Mexican horror film Espiritismo that opened the same day.10 The caption for the still from Benito Alazraki’s Espirtismo read in part, ‘interminable minutes of true anguish and authentic suspense parade across the screen’ while to its right on the page the still of Vera Miles screaming in Psycho was titled ‘In “Psycho” Suspense Reaches its Climax’. The ads for the two films were prominently juxtaposed.

Juxtaposition of ads in El Universal for Psycho and Espritisimo.

Espiritismo copied the graphic style of the torn page from Psycho. Yet El Universal carried the theme from this Mexican/Hollywood dialogue to editorialise on the state of Mexican cinema in ‘Expectación y “Suspenso” en el Paréntesis Espectacular del Cine’ (‘Expectation and “Suspense” in the Spectacular Pause in the Cinema’) that the government had to respond to Mexican movie producers who were running out of funds. The article concluded:

The way that some producers found to make movies in collaboration with the workers is good: but it is only a temporary measure for the moment. Because of this it is urgent to hear the response of Mr. Secretary of Government, for the cinematographic industry is in his hands. (El Universal, 29 March 1962, Section 3: 7)

Although the co-opting of Psycho in Mexico, to sell or save national cinema, on the one hand may have diminished its impact, more likely it reaffirmed the reputation of Hitchcock in that he could serve as a fulcrum for a discussion of a national cinema crisis.

Although De entre los muertos (Vertigo) and Intriga nacional (North by Northwest) – nowadays among Hitchcock’s most highly regarded films – played Mexico City to respectable runs and good crowds, neither of these films could be considered blockbusters during their release based on the news reports. The Hitchcock film that received the most attention, and blockbuster status, was Los pájaros (The Birds). It opened in multiple theatres and played to big audiences. As the Universal reporter notes, Hitchcock was by then even more popular due to his television series. Moreover most people had already heard of the film from reports on its US release:

A lot has been said about this movie, its presentation on Broadway was a reason for scandal because of the anticipation that it generated and the effects seen after the film finished, which have been discussed a lot. To create this state of anxiety producing emotion it turned to two elements for which the public feels sympathy and attraction: children and birds. Birds taken in isolation, except for predators, are innocent and cause no harm, but in a swarm and furious for whatever reason, they are terrifying. (El Universal, 18 July 1963, Section 3: 7)

Again these newspaper commentaries wove a story of the crisis in Mexican cinema, ‘Una sección puede paralizar el cine’, (‘A sector of a union can paralyse the movies’), around their Hitchcock review. In fact a union strike of cinematographic workers was forecast for the day The Birds opened. The next day El Universal published a survey of comments of the people who saw the premiere. Most proclaimed astonishment along with their endorsement, as did Mr. Moisés García, a businessman: ‘Me trajeron a la fuerza, pero oiga usted ¡qué peliculón!’ (‘They forced me to come, but listen, what a blockbuster!’). The article emphasised the opinion of Mr. Justino Blas Henríquez:

Si lo que pasa por la pantalla fuera realidad algún día, ¡qué bomba atómica ni ‘qué hacha’! Esto sí que es realmente pavoroso. Con solo pensar que eso le pudiera pasar a mi familia, ‘se me pone la carne de gallina’… (If what happens on screen were to become reality some day, what an atomic bomb, or blow! This really is something dreadful. Only thinking that it could happen to my family makes my hair stand on end… (El Universal, 19 July 1963)

This reminds us that in 1963 the final scene in The Birds could be thought of in terms of nuclear war, an interpretation that is seldom evoked for the film today.11 The Universal headlines of 22 July 1963 – ‘Advierte el Papa la Esperanza de que Haya una Tregua Nuclear’ (‘The Pope Expresses Hope for a Nuclear Treaty’) – confirm that Mexicans were indeed aware of the nuclear threat.

Hitchcock’s films of the late 1960s – Marnie and Torn Curtain – were mostly discussed in terms of the delay in their opening in Mexico. El Universal captioned one Torn Curtain still with this complaint: ‘This much-anticipated film today receives the prize for the long time its opening was postponed. Such an event will happen today Thursday in the Chapultepec, finally putting an end to the public build-up that anticipates the success that this film will receive in Mexico’ (Universal, February 2, 1967). Although in other eras delays signalled censorship, these probably reflected diminished expectations for these films’ commercial potential.12 When Torn Curtain, the more political of the two films opened, most attention was dedicated to Sophia Loren in Judith (1966) and the excitement around and countdown to the Mexico City Olympics: ‘617 days are left.’ Marnie, and all other entertainment news, was rather lost in the extensive coverage of Churchill’s death, mourning and funeral that coincided with Marnie’s release and opening week. For the ex-pat Hitchcock, then perceived to be in decline, this was perhaps fitting.

VI. CONCLUSIONS

Our readings of the historical and cultural record in El Universal and Excelsior have brought to light important trends in the Mexican reception of Hitchcock’s films. First, his films of the 1930s, that is, British Hitchcock, had a significant impact in Mexico and even entered into the political discourse of those years of the Cárdenas administration (1934–1940) as events from Trotsky’s exile in Mexico were envisioned as Sabotage. In this period, moreover, Hitchcock’s films were viewed as generic hybrids and praised for their humour as well as for their spy or police plots. Second, during the subsequent decades of the 1940s and early 1950s, the reception changed as Hitchcock’s films were inflected by the context of the Golden Age of Mexican cinema and its emphasis on melodrama. Most significantly, Hitchcock’s crossover to Hollywood was framed differently in Mexico than in Spain. Whereas Rebecca, a pseudo-Old World drama, marked the transition elsewhere, Mexico celebrated Casados y descasados (Mr. and Mrs. Smith), a comedy of modern marriage, in a Hollywood extravaganza that promoted the new aerial link between Mexico City and Los Angeles. Third, throughout his career Hitchcock was synonymous in Mexico with innovation and progress, such as improvements in sound or the advent of colour, which became increasingly important as upscale theatres expanded in the capital. Fourth, especially later in Hitchcock’s career, from the 1960s on, his advertising was copied to market Mexican film and serious newspaper commentary grabbed onto the now familiar, reductive vision of Hitchcock as ‘master of suspense’ to create interest in their headlines about the financial crisis in Mexican cinema. Overall our analysis here has shown that the appraisal of Hitchcock’s films in newspapers was far more widespread and its characterisation most distinctive in the earlier part of his career than in what we now consider his mature period.13

Finally, it is important to reiterate that what constituted film criticism or film commentary in Mexican newspapers throughout Hitchcock’s career was different from what was practiced in other Latin American capitals, or what we expect and understand today from major news sources. For instance Buenos Aires had and continues to have a strong tradition of film criticism including bylined reviews in La Nación. With rare exceptions in Mexico City film critics were anonymous. Film commentary was a popular service like a restaurant review. Serious commentary was devoted to the discussion of national policies or the financial state of the industry, seldom to aesthetic or narrative cinematographic interpretation. This type of commentary, however, situated Hitchcock within the cinematographic industry and often identified him as an industrial model.

Further study of contemporaneous literary and popular magazines, many of which began during the 1960s, a decade which marked a mini-boom in cinema magazines, would complement our focus on major newspapers and would likely reveal other aspects of Mexican reception of late Hitchcock. They may provide reasons for the delay in the release of several Hitchcock films, which newspapers lamented. Likewise it would be important to discover if Hitchcock’s classic films such as Psycho, Vertigo and North by Northwest, later The Birds and Frenzy, received significant attention in Mexican cinema magazines or whether they were shunted aside as too ‘commercial’.

To begin to expand our analysis to these other sources, we can conclude by turning to Francisco Sánchez Aguilar, a screenwriter and film critic, and above all the well-respected film critic for Esto (1972–1980), a high circulation sports paper, and consider his remarks on Hitchcock in Cinefilia es locura (2004), a memory of his cinema-going experiences. In Cinefilia, which includes Sánchez’ published interviews, he praises Psycho and Rear Window, but finds his pet peeve with Hitchcock’s kisses:

I’ve never understood why Hitchcock liked kisses so much. A kiss always stops the action. Buñuel detested them as kitsch; I, because they’re anti-cinematographic. Juan Antonio de la Riva understood it very well.14 Hitchcock, on the other hand, never understood it. (2004: 210)

Sánchez is an important Buñuel scholar, author of Todo Buñuel (1978) and Siglo Buñuel (2000), among other film books, so it is not surprising that Hitchcock ranks below Buñuel in Sánchez’s estimation here. Nonetheless, even a Buñuel scholar, who says ‘La pasión por el cine es mi tema’ (‘Passion for cinema is my obsession’) when asked to choose an example of a kind of film about which he feels passionately, cites not Buñuel, but Hitchcock.

I tend to like boxes that contain a box, which contains another box, etc. To give them a name, I’ll call them matrioska movies. These are the ones that excite me. An example: The Birds. This notable film by Alfred Hitchcock encompasses at least three schemes: the birds’ attack, the love story and the transposition of feminine personalities. Not satisfied with that, the filmmaker even adds parables like the following: The hero (a term which with respect to this film has to go between quotation marks) is a lawyer and his little sister calls him a defender of crooks. There are protests and the young girl counters with her point of view: ‘Now you’re defending – she says – a guy who killed his wife with six shots to the head.’ And she adds, ‘It´s something terrible! An outrage!’ There’s a pause. Everybody in the room supposes that the girl is justifiably terrified, but – oh, surprise! – the reasons for her anxiety are of a more pragmatic sort, for as she right away explains: ‘I think two shots were more than enough.’ Tippi Hedren in turn asks for the reason why the man killed his wife so savagely. With his touch of black humour, the answer is as simple as it is eloquent: ‘Because she turned off the television while he was watching a baseball game.’ (2004: 201–2)

Sánchez’s passionate choice, and defence of The Birds underscores the importance that this film had in Mexico City. His comments on the film’s dialogue moreover bring into relief the enduring role of humour in the reception of Hitchcock in Mexico, whose presence the Mexican filmmaker Guillermo del Toro was to note and exploit in his own films in subsequent decades.

NOTES