Flamboyant Sevilla (seh-VEE-yah) thrums with flamenco music, sizzles in the summer heat, and pulses with the passion of Don Juan and Carmen. It’s a place where bullfighting is still politically correct and little girls still dream of growing up to become flamenco dancers. While Granada has the great Alhambra and Córdoba has the remarkable Mezquita, Sevilla has a soul. (Soul—or duende—is fundamental to flamenco.) It’s a wonderful-to-be-alive-in kind of place.

The gateway to the New World in the 16th century, Sevilla boomed when Spain did. The explorers Amerigo Vespucci and Ferdinand Magellan sailed from its great river harbor, discovering new trade routes and abundant sources of gold, silver, cocoa, and tobacco. In the 17th century, Sevilla was Spain’s largest and wealthiest city. Local artists Diego Velázquez, Bartolomé Murillo, and Francisco de Zurbarán made it a cultural center. Sevilla’s Golden Age—and its New World riches—ended when the harbor silted up and the Spanish empire crumbled.

In the 19th century, Sevilla was a big stop on the Romantic “Grand Tour” of Europe. To build on this tourism and promote trade among Spanish-speaking nations, Sevilla planned a grand exposition in 1929. Bad year. The expo crashed along with the stock market. In 1992 Sevilla got a second chance at a world’s fair. This expo was a success, leaving the city with an impressive infrastructure: a new airport, a train station, sleek bridges, and the super AVE bullet train (making Sevilla a 2.5-hour side-trip from Madrid). In 2007, the main boulevards—once thundering with noisy traffic and mercilessly cutting the city in two—were pedestrianized, dramatically enhancing Sevilla’s already substantial charm.

Today, Spain’s fourth-largest city (pop. 704,000) is Andalucía’s leading destination, buzzing with festivals, color, guitars, castanets, and street life, and enveloped in the fragrances of orange trees, jacaranda, and myrtle. James Michener wrote, “Sevilla doesn’t have ambience, it is ambience.” Sevilla also has its share of impressive sights. Its cathedral is Spain’s largest. The Alcázar is a fantastic royal palace and garden ornamented with Mudejar (Islamic) flair. But the real magic is the city itself, with its tangled former Jewish Quarter, riveting flamenco shows, thriving bars, and teeming evening paseo.

On a three-week trip, spend two nights and two days here. On even the shortest Spanish trip, I’d zip here on the slick AVE train for a day trip from Madrid. With more time, if ever there was a Spanish city to linger in, it’s Sevilla.

The major sights are few and simple for a city of this size. The cathedral and the Alcázar are worth about three hours, and a wander through the Santa Cruz district takes about an hour. You could spend half a day touring Sevilla’s other sights. Stroll along the bank of the Guadalquivir River and cross Isabel II Bridge (also known as the Bridge of Triana) for a view of the cathedral and Torre del Oro. An evening here is essential for the paseo and a flamenco show. Stay up at least once until midnight (or later) to appreciate Sevilla on a warm night—one of its major charms.

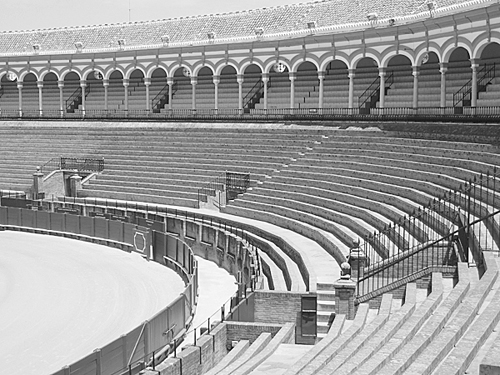

Bullfights take place on most Sundays in May and June, on Easter and Corpus Christi, daily through the April Fair, and in late September. The Museo de Bellas Artes is closed on Monday. Tour groups clog the Alcázar and cathedral in the morning; go late in the day to avoid the lines.

Córdoba is a convenient and worthwhile side-trip from Sevilla, or a handy stopover if you’re taking the AVE to or from Madrid.

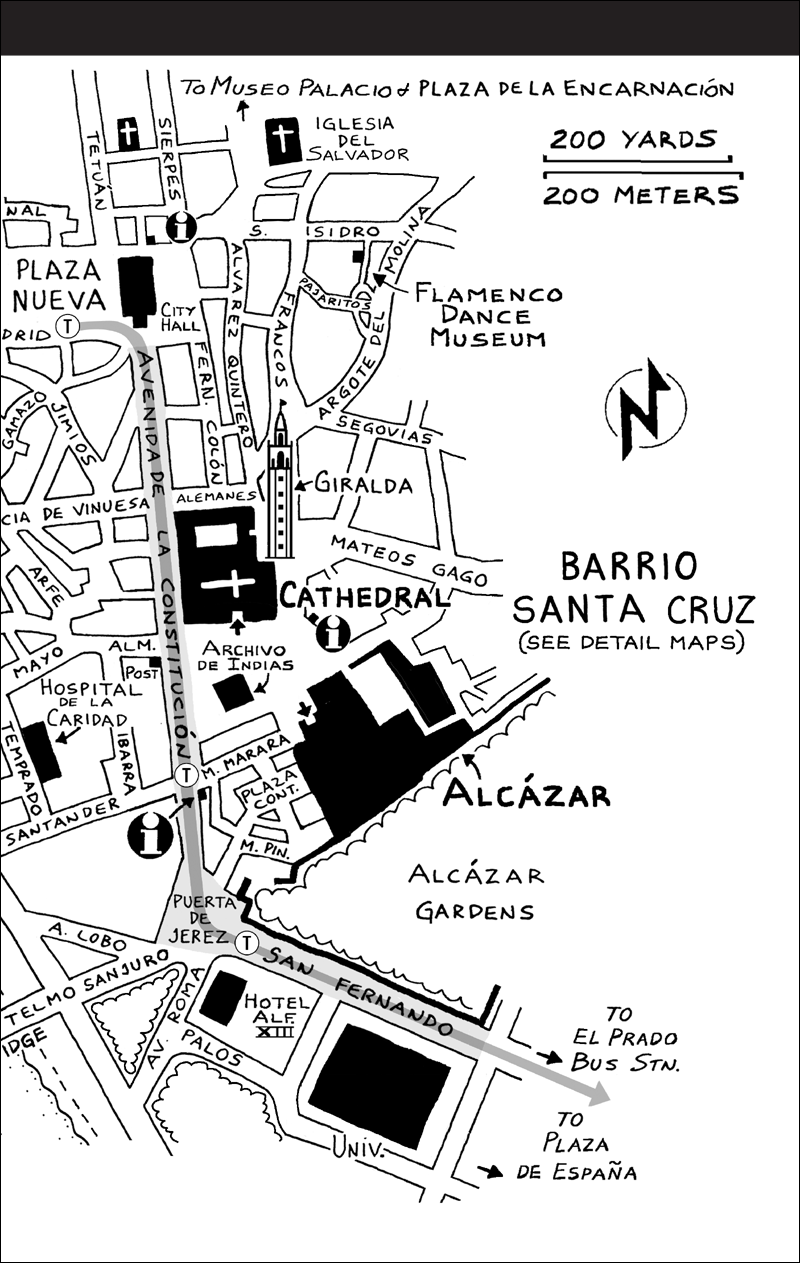

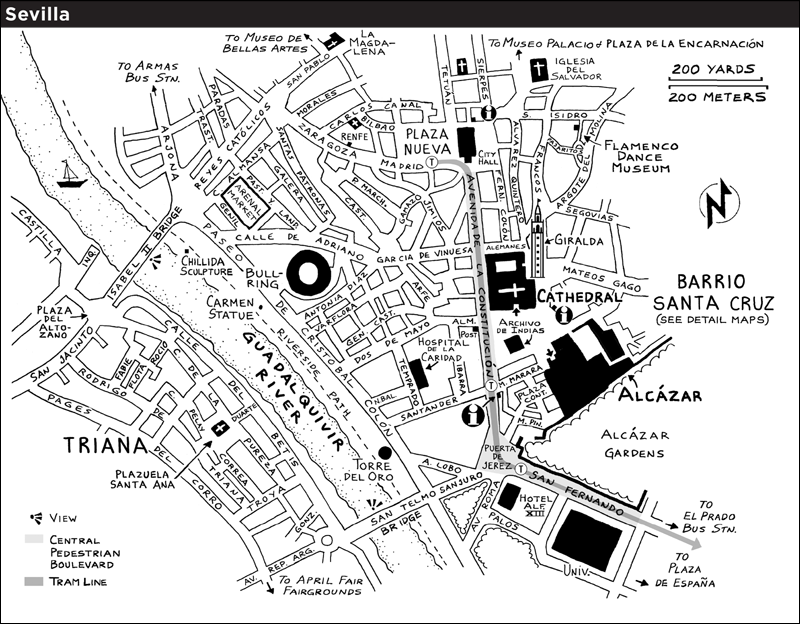

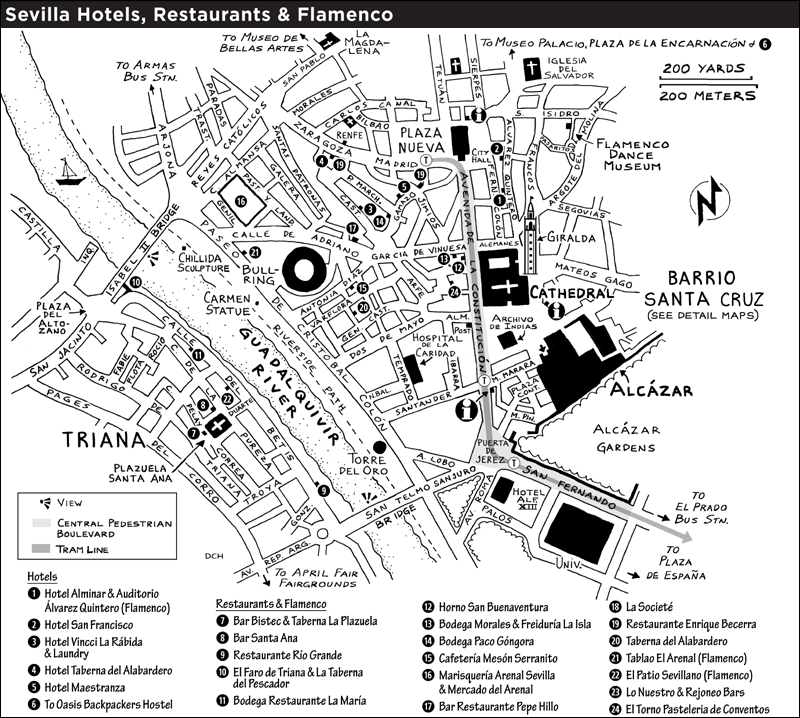

For the tourist, this big city is small. The bull’s-eye on your map should be the cathedral and its Giralda Bell Tower, which can be seen from all over town. Nearby are Sevilla’s other major sights, the Alcázar (palace and gardens) and the lively Santa Cruz district. The central north-south pedestrian boulevard, Avenida de la Constitución (with TIs, banks, a post office, and other services), stretches north a few blocks to Plaza Nueva, gateway to the shopping district. A few blocks west of the cathedral are the bullring and the Guadalquivir River, while Plaza de España is a few blocks south. Triana, the area on the west bank of the Guadalquivir River, is working-class and colorful, but lacks tourist sights. With most sights walkable, and taxis so friendly, easy, and affordable, I rarely bother with the bus.

Sevilla is an easy city to get turned around in. Be aware that city maps from the tourist office are oriented with north to the left, while this book’s maps put north on top.

Sevilla has tourist offices wherever you need them—at the airport (Mon-Fri 9:00-19:30, Sat-Sun 9:30-15:00, tel. 954-782-035), train station (overlooking tracks 6-7, Mon-Fri 9:00-19:30, Sat-Sun 9:30-15:00, tel. 954-782-003), and in central locations near Avenida de la Constitución: near the river side of the Alcázar (Mon-Fri 9:00-19:30, Sat-Sun 9:30-15:00, Avenida de la Constitución 21, tel. 954-787-578); and across the small square from the cathedral entrance (Mon-Sat 10:30-14:30 & 15:30-19:30, Sun 10:30-14:30, Plaza del Triunfo, tel. 954-210-005). Another TI, near Plaza Nueva, will likely move to a new location sometime in 2013 (Mon-Fri 9:00-19:30, Sat-Sun 10:00-14:00, across from City Hall at north end of Plaza de San Francisco, tel. 955-471-232, free Internet access for one hour at certain times—see “Helpful Hints,” later).

At any TI, ask for the city map, the English-language magazines Welcome Olé and The Tourist, and a current listing of sights with opening times. The free monthly events guide—El Giraldillo, written in Spanish basic enough to be understood by travelers—covers cultural events throughout Andalucía, with a focus on Sevilla. The Alcázar and airport TIs cover all of Andalucía as well as Sevilla; if you stop at one of these, ask for information you might need for elsewhere in the region (for example, if heading south, ask for the free Route of the White Towns brochure and a Jerez map). Helpful websites are www.turismosevilla.org and www.andalucia.org.

Sightseeing Pass: The Sevilla Card (sold at the ICONOS shop next to the Alcázar TI, Mon-Sat 10:00-20:00, Sun 11:00-19:00; or at the train station’s hotel room-finding booth overlooking track 11) covers admission to most of Sevilla’s sights (including the cathedral, Alcázar, Flamenco Dance Museum, Basílica de la Macarena, Bullfight Museum, and more), and gives discounts at some hotels and restaurants. It’s doubtful whether any but the busiest sightseer would save much money using the card (€33/24 hours—includes choice of 2 museums and river cruise; €53/48 hours—includes all sights and choice of river cruise or bus tour; €71/72 hours or €77/120 hours—includes all sights plus cruise and bus tour; www.sevillacard.es). If you’re over 65, keep in mind that even without the Sevilla Card, you’ll get into the Alcázar and the cathedral almost free.

By Train: Trains arrive at the sublime Santa Justa station, with banks, ATMs, and a TI. Baggage storage (cosigna) is below track 1 (€3-5/day depending on size of bag, security checkpoint open 6:00-24:00). The TI overlooks tracks 6-7. If you don’t have a hotel room reserved, the room-finding booth above track 11 can help; you can also get maps and other tourist information here if the TI line is long (Mon-Fri 10:00-20:30, Sat 10:00-14:30 & 16:30-20:30, Sun 9:30-14:30). The plush little AVE Sala Club, designed for business travelers, welcomes those with a first-class AVE ticket and reservation (across the main hall from track 1).

The town center is marked by the ornate Giralda Bell Tower, peeking above the apartment flats (visible from the front of the station—with your back to the tracks, it’s at 1 o’clock). To get into the center, it’s a flat and boring 25-minute walk (longer if you get lost) or about a €5 taxi ride. By city bus, it’s a short ride on #C1 to the El Prado bus station (€1.30, pay driver, find bus stop 100 yards in front of the train station), then a 10-minute walk.

By Bus: Sevilla’s two major bus stations both have information offices, basic eateries, and baggage storage. The El Prado station covers most of Andalucía (daily 7:00-22:00, information tel. 954-417-111, no English spoken; baggage storage/consigna at the far end of station—€2/day, daily 9:00-21:00). From the bus station to downtown (and Barrio Santa Cruz hotels), it’s about a 10-minute walk: Exit the station to the right, and cross the busy street at the big roundabout. Turn right and keep the fenced-in gardens on your left. At the end of the fence, duck left through the Murillo Gardens and into the heart of Barrio Santa Cruz (use the color map in the front of this book to navigate). To cut a few minutes off the walk—or to reach the hotels near Plaza Nueva—take the city’s short tram from the El Prado station (€1.30, buy ticket at machine before boarding; ride it two stops to Archivo de Indias to reach the cathedral area, or three stops to Plaza Nueva).

The Plaza de Armas station (near the river, opposite the Expo ’92 site) serves long-distance destinations such as Madrid, Barcelona, Lagos, and Lisbon. Ticket counters line one wall, an information kiosk is in the center, and at the end of the hall are luggage lockers (€3.50/day). As you exit onto the main road (Calle Arjona), the bus stop is to the left, in front of the taxi stand (bus #C4 goes downtown, €1.30, pay driver, get off at Puerta de Jerez near main TI). Taxis to downtown cost around €5.

By Car: To drive into Sevilla, follow centro ciudad (city center) signs and stay along the river. For short-term parking on the street, the riverside Paseo de Cristóbal Colón has two-hour meters and hardworking thieves. Ignore the bogus traffic wardens who direct you to an illegal spot, take a tip, and disappear later when your car gets towed. For long-term parking, hotels charge as much as a normal garage. For simplicity, I’d just park at a central garage (€15-20/day) and catch a taxi to my hotel. Try the big one under the bus station at Plaza de Armas, the Cristóbal Colón garage by the bullring and river, the Plaza Nueva garage on Albareda, or the one at Avenida Roma/Puerta de Jerez (cash only). For hotels in the Santa Cruz area, the handiest parking is the Cano y Cueto garage near the corner of Calle Santa María la Blanca and Menéndez Pelayo (open 24/7, at edge of big park, unsigned and underground).

By Plane: The Especial Aeropuerto (EA) bus connects Sevilla’s San Pablo Airport with the train station and town center, terminating south of the Alcázar gardens on Avenida Carlos V (€2.40, 2/hour, 30 minutes, buy ticket from driver). If you’re going from downtown Sevilla to the airport, ask your hotelier or the TI where to catch the bus; the stop is usually on Avenida Carlos V by the Portugal Pavilion but can change because of religious processions, construction, and other factors. (The return bus also stops at the Santa Justa train station and the El Prado bus station.) To taxi into town, go to one of the airport’s taxi stands to ensure a fixed rate (€22 by day, €24 at night and on weekends, €29 during Easter week, extra for luggage, confirm price with the driver before your journey). For flight information, call 954-449-000 (airport code: SVQ, www.aena-aeropuertos.es).

Most visitors have a full and fun experience in Sevilla without ever riding public transportation. The city center is compact, and most of the major sights are within easy walking distance (the Basílica de la Macarena is a notable exception). On a hot day, air-conditioned buses can be a blessing.

By Taxi: Sevilla is a great taxi town. You can hail one anywhere, or find them parked by major intersections and sights (weekdays: €1.26 drop rate, €0.87/kilometer, €3.43 minimum; Sat-Sun, weekends, and nights between 21:00 and 7:00: €1.53 drop rate, €1.07/kilometer, €4.29 minimum; calling for a cab adds about €2-3. A quick daytime ride in town will be at or around the €3.43 minimum. Although I’m quick to take advantage of a taxi, thanks to one-way streets and traffic congestion it’s often just as fast to hoof it between central points.

By Bus, Tram, and Metro: Due to ongoing construction projects in the city center, bus routes often change. It’s best to check with your hotel or the TI for the latest updates.

A single trip on any form of city transit costs €1.30. You can also buy a Tarjeta Multiviajes card that’s rechargeable and shareable (€6.40 for 10 trips without transfers, €7 with transfers, €1.50 deposit, buy at kiosks; for transit details, see www.tussam.es).

The various #C buses, which are handiest for tourists, make circular routes through town (note that all of them eventually wind up at Basílica de La Macarena). For all buses, buy your ticket from the driver. The #C3 stops at Murillo Gardens, Triana (district on the west bank of the river), then La Macarena. The #C4 goes the opposite direction without entering Triana. And the spunky little #C5 is a minibus that winds through the old center of town, including Plaza del Salvador, Plaza de San Francisco, the bullring, Plaza Nueva, the Museo de Bellas Artes, La Campana, and La Macarena, providing a fine and relaxing joyride that also connects some farther-flung sights.

A new tram (tramvia) makes just a few stops in the heart of the city, but can save you a bit of walking. Buy your ticket at the machine on the platform before you board, then tap it on the card reader in the tram (runs every 6-7 minutes until 1:45 in the morning). The handiest stops include (from south to north) Prado San Sebastián (El Prado Bus station), Puerta Jerez (the south end of Avenida de la Constitución), Archivo de Indias (next to the cathedral), and Plaza Nueva. Eventually the tram will reach the Santa Justa train station.

Sevilla also has a brand-new underground metro, but tourists won’t need to use it. It’s designed to connect the suburbs with the center and is only partially finished.

Festivals: Sevilla’s peak season is April and May, and it has two one-week festival periods when the city is packed: Holy Week and April Fair.

While Holy Week (Semana Santa) is big all over Spain, it’s biggest in Sevilla. It’s held the week between Palm Sunday and Easter Sunday (March 24-30 in 2013). Locals start preparing for the big event up to a year in advance. What would normally be a five-minute walk can take an hour and a half if a procession crosses your path. But even these hassles seem irrelevant as you listen to the saetas (spontaneous devotional songs) and let the spirit of the festival take over.

Then, after Easter—after taking enough time off to catch its communal breath—Sevilla holds its April Fair (April 16-21 in 2013). This is a celebration of all things Andalusian, with plenty of eating, drinking, singing, and merrymaking (though most of the revelry takes place in private parties at a large fairground).

Book rooms well in advance for these festival times. Prices can go sky-high, many hotels have four-night minimums, and food quality at touristy restaurants can plummet.

Internet Access: Almost every hotel in town has Wi-Fi, and many also have Internet terminals or loaner laptops for guests to use. The city itself is fairly Wi-Fi friendly. Find free Wi-Fi on the new tram, at the Museo de Bellas Artes, and in the Plaza de la Encarnación, among other public spaces. The TI near Plaza Nueva (close to City Hall, at north end of Plaza de San Francisco) offers up to one hour of free Internet access at eight terminals, as well as free Wi-Fi (Internet available only Mon-Fri 10:00-14:00 & 17:00-20:00, none Sat-Sun; this TI will likely move to a new location in 2013).

Post Office: The post office is at Avenida de la Constitución 32, across from the cathedral (Mon-Fri 8:30-20:30, Sat 9:30-14:00, closed Sun).

Laundry: Lavandería Roma offers quick and economical drop-off service (€6/load wash-and-dry, Mon-Fri 10:00-14:00 & 17:30-20:30, Sat 9:00-14:00, closed Sun, 2 blocks inland from bullring at Castelar 2, tel. 954-210-535). Near the recommended Santa Cruz hotels, La Segunda Vera Tintorería has two machines for self-service (€10/load wash-and-dry, €10/load drop-off service, Mon-Fri 9:30-14:00 & 17:30-20:30, Sat 10:00-13:30, closed Sun, about a block from the eastern edge of Santa Cruz at Avenida Menéndez Pelayo 11, tel. 954-536-376).

Bike Rental: Sevilla is an extremely biker-friendly city, with designated bike lanes and a public bike-sharing program (€11 one-week subscription, first 30 minutes of each ride free, €1-2 for each subsequent hour, www.sevici.es). Ask the TI about this and other bicycle rental options.

Train Tickets: For schedules and tickets, visit the RENFE Travel Center at the train station (daily 8:00-22:00, take a number and wait, tel. 902-320-320 for reservations and info) or the one near Plaza Nueva in the center (Mon-Fri 9:30-13:30 & 17:30-19:30, Sat 10:00-13:00, closed Sun, Calle Zaragoza 29, tel. 954-211-455). You can also check schedules at www.renfe.com. Many travel agencies sell train tickets; look for a train sticker in agency windows.

Warning: You may encounter women thrusting sprigs of rosemary into the hands of passersby, grunting, “Toma! Es un regalo!” (“Take it! It’s a gift!”). If you take one of these sprigs, you’ll be harassed for money in return. Just walk on by if you are approached.

Guided City Walks by Concepción—Concepción Delgado, an enthusiastic teacher who’s a joy to listen to, takes small groups on English-language walks. Using me as her guinea pig, Concepción has designed a fine two-hour Sevilla Cultural Show & Tell. This introduction to her hometown, sharing important insights the average visitor misses, is worthwhile even on a one-day visit (€15/person, minimum 4 people, Feb-July and Sept-Dec Mon-Sat at 10:30; Jan and Aug on Mon, Wed, and Fri only; meet at statue in Plaza Nueva).

For those wanting to really understand the city’s two most important sights—which are tough to fully appreciate—Concepción also offers in-depth tours of the cathedral and the Alcázar (both tours last 1.25 hours; €7 plus entrance fees, €2 discount if you also take the Show & Tell tour; meet at 13:00 at statue in Plaza del Triunfo; minimum 4 people; cathedral tours—Mon, Wed, and Fri; Alcázar tours—Tue, Thu, and Sat; no Alcázar tours Jan and Aug).

Although you can just show up for Concepción’s tours, it’s smart to confirm the departure times and reserve a spot (tel. 902-158-226, mobile 616-501-100, www.sevillawalkingtours.com, info@sevillawalkingtours.com). Concepción does no tours on Sundays or holidays. Because she’s a busy mom of two young kids, Concepción sometimes sends her colleague Alfonso (who’s also excellent) to lead these tours.

Hop-On, Hop-Off Bus Tours—Two competing city bus tours leave from the curb near the riverside Torre del Oro (Gold Tower). You’ll see the parked buses and salespeople handing out fliers. Each tour does about an hour-long swing through the city with recorded narration (€16-17, daily 10:00-21:00, green route has shorter option). The tours, which allow hopping on and off at four stops, are heavy on Expo ’29 and Expo ’92 neighborhoods—both zones of little interest in 2013. While the narration does its best, Sevilla is most interesting where buses can’t go.

Bike Tours—Really Discover takes up to 15 riders on a 2.5-hour journey around the city, stopping at—but not entering—all the major sights (€25, includes bike, one daily tour in English at 10:30, meet by fountain across street from Alcázar TI, call or email to confirm as tours may be canceled for lack of interest, www.reallydiscover.com, davidcox@reallydiscover.com, tel. 955-113-912).

Horse and Buggy Tours—A carriage ride is a classic, popular way to survey the city and a relaxing way to enjoy María Luisa Park (€40-50 for a 45-minute clip-clop, find a likable English-speaking driver for better narration). Look for rigs at Plaza América, Plaza del Triunfo, Torre del Oro, Alfonso XIII Hotel, and Avenida Isabel la Católica.

Boat Cruises—Boring one-hour panoramic tours leave every 30 minutes from the dock behind Torre de Oro. The low-energy recorded narration is hard to follow, but there’s little to see anyway (overpriced at €15, tel. 954-561-692).

More Tours—Visitours, a typical big-bus tour company, does €95 all-day trips to Córdoba (Tue, Thu, and Sat; tel. 955-999-760, mobile 686-413-413, www.visitours.es, visitours@visitours.es). For other guides, contact one of the Guide Associations of Sevilla: AUITS (tel. 699-494-204, www.auits.com, guias@auits.com) or APIT (tel. 954-210-037, www.apitsevilla.com, visitas@apitsevilla.com).

Of Sevilla’s once-thriving Jewish Quarter, only the tangled street plan and a wistful Old World ambience survive. This classy maze of lanes (too slender for cars), small plazas, tile-covered patios, and whitewashed houses with wrought-iron latticework draped in flowers is a great refuge from the summer heat and bustle of Sevilla. The streets are narrow—some with buildings so close they’re called “kissing lanes.” A happy result of the narrowness is shade: Locals claim the Barrio Santa Cruz is three degrees cooler than the rest of the city.

Orange trees abound—because they never lose their leaves, they provide constant shade. But forget about eating any of the oranges. They’re bitter and used only to make vitamins, perfume, cat food, and that marmalade you can’t avoid in British B&Bs. But when they blossom (for three weeks in spring, usually in March), the aroma is heavenly.

The Barrio is made for wandering. Getting lost is easy, and I recommend doing just that. But to get started, here’s a plaza-to-plaza walk that loops you through the corazón (heart) of the neighborhood and back out again. Ideally, don’t do the walk in the morning, when the Barrio’s charm is trampled by tour groups. Early evening (around 18:00) is ideal.

Plaza de la Virgen de los Reyes: Start in the square in front of the cathedral, at the base of the Giralda Bell Tower.

This square is dedicated to the Virgin of the Kings. See her tile on the white wall

facing the cathedral. She is one of several different versions of Mary you’ll see

in Sevilla, each appealing to a different type of worshipper. This one is big here

because the Spanish king reportedly carried her image with him when he retook the

town from the Moors in 1248. The fountain dates from 1929. From this peaceful square,

look up the street leading away from the cathedral and notice the characteristic (government-protected)

19th-century architecture. The ironwork is typical of Andalucía and the pride of Sevilla.

You’ll see it and the traditional color scheme of whitewash-and-goldenrod all over

the town center.

Plaza de la Virgen de los Reyes: Start in the square in front of the cathedral, at the base of the Giralda Bell Tower.

This square is dedicated to the Virgin of the Kings. See her tile on the white wall

facing the cathedral. She is one of several different versions of Mary you’ll see

in Sevilla, each appealing to a different type of worshipper. This one is big here

because the Spanish king reportedly carried her image with him when he retook the

town from the Moors in 1248. The fountain dates from 1929. From this peaceful square,

look up the street leading away from the cathedral and notice the characteristic (government-protected)

19th-century architecture. The ironwork is typical of Andalucía and the pride of Sevilla.

You’ll see it and the traditional color scheme of whitewash-and-goldenrod all over

the town center.

Another symbol you’ll see throughout Sevilla is the city insignia: “NO8DO,” the letters “NODO” with a figure-eight-like shape at their center. Nodo meant “knot” in the old dialect, and this symbol evokes the strong ties between the citizens of Sevilla and King Alfonso X (during a succession dispute in the 13th century, the Sevillans remained loyal to their king).

• Walk with the cathedral on your right into the...

Plaza del Triunfo: The “Plaza of Triumph” is named for the 1755 earthquake that destroyed Lisbon and

rattled Sevilla, but left most of the city intact. Find the statue thanking the Virgin,

located at the far end of the square, under a stone canopy. That Virgin faces another

one (closer to you), atop a tall pillar honoring Sevillan artists, including the painter

Murillo (see “Casa de Murillo,” later).

Plaza del Triunfo: The “Plaza of Triumph” is named for the 1755 earthquake that destroyed Lisbon and

rattled Sevilla, but left most of the city intact. Find the statue thanking the Virgin,

located at the far end of the square, under a stone canopy. That Virgin faces another

one (closer to you), atop a tall pillar honoring Sevillan artists, including the painter

Murillo (see “Casa de Murillo,” later).

• Pass through the opening in the crenellated Alcázar wall under the arch. You’ll emerge into a courtyard called the...

Patio de Banderas: Named for “flags,” not Antonio, the Banderas Courtyard was once a kind of military

parade ground for the royal guard. The barracks surrounding the square once housed

the king’s bodyguards. Today, the far end of this square is a favorite spot for a

postcard view of the Giralda Bell Tower.

Patio de Banderas: Named for “flags,” not Antonio, the Banderas Courtyard was once a kind of military

parade ground for the royal guard. The barracks surrounding the square once housed

the king’s bodyguards. Today, the far end of this square is a favorite spot for a

postcard view of the Giralda Bell Tower.

• Exit the courtyard at the far corner, through the Judería arch. Go down the long, narrow passage. Emerging into the light, you’ll be walking alongside the Alcázar wall. Take the first left, then right, through a small square and follow the narrow alleyway called...

Calle Agua: As you walk along the street, look to the left, peeking through iron gates for occasional

glimpses of the flower-smothered patios of exclusive private residences. The patio

at #2 is a delight—ringed with columns, filled with flowers, and colored with glazed

tiles. The tiles are not only decorative; they keep buildings cooler in the summer

heat. Emerging at the end of the street, turn around and look back at the openings

of two old pipes built into the wall. These pipes once carried water to the Alcázar

(and today give the street its name). You’re standing at an entrance into the pleasant

Murillo Gardens (to the right), formerly the fruit-and-vegetable gardens for the Alcázar.

Calle Agua: As you walk along the street, look to the left, peeking through iron gates for occasional

glimpses of the flower-smothered patios of exclusive private residences. The patio

at #2 is a delight—ringed with columns, filled with flowers, and colored with glazed

tiles. The tiles are not only decorative; they keep buildings cooler in the summer

heat. Emerging at the end of the street, turn around and look back at the openings

of two old pipes built into the wall. These pipes once carried water to the Alcázar

(and today give the street its name). You’re standing at an entrance into the pleasant

Murillo Gardens (to the right), formerly the fruit-and-vegetable gardens for the Alcázar.

• Don’t enter the gardens now, but instead cross the square diagonally and continue 20 yards down a lane to the...

Plaza de la Santa Cruz: Arguably the heart of the Barrio, this is a pleasant square of orange and olive trees

and draping vines. It was once the site of a synagogue (the Barrio had three; now

there are none), which Christians destroyed. They replaced the synagogue with a church,

which the French (under Napoleon) then demolished. It’s a bit of history that locals

remember when they see the blue, white, and red French flag marking the French consulate,

now overlooking this peaceful square. The Sevillan painter Murillo, who was buried

in the now-gone church, lies somewhere below you. On the square you’ll find the recommended

Los Gallos flamenco bar, which combusts nightly after midnight with impromptu flamenco.

Plaza de la Santa Cruz: Arguably the heart of the Barrio, this is a pleasant square of orange and olive trees

and draping vines. It was once the site of a synagogue (the Barrio had three; now

there are none), which Christians destroyed. They replaced the synagogue with a church,

which the French (under Napoleon) then demolished. It’s a bit of history that locals

remember when they see the blue, white, and red French flag marking the French consulate,

now overlooking this peaceful square. The Sevillan painter Murillo, who was buried

in the now-gone church, lies somewhere below you. On the square you’ll find the recommended

Los Gallos flamenco bar, which combusts nightly after midnight with impromptu flamenco.

• At the far end of the square, a one-block (optional) detour along Calle Mezquita leads to the nearby...

Plaza de Refinadores: Sevilla’s most famous (if fictional) 17th-century citizen is honored here with a

statue (see photo). Don Juan Tenorio—the original Don Juan—was a notorious sex addict

and atheist who proudly thumbed his nose at the stifling Church-driven morals of his

day.

Plaza de Refinadores: Sevilla’s most famous (if fictional) 17th-century citizen is honored here with a

statue (see photo). Don Juan Tenorio—the original Don Juan—was a notorious sex addict

and atheist who proudly thumbed his nose at the stifling Church-driven morals of his

day.

• Backtrack to Plaza de la Santa Cruz and turn right (north) on Calle Santa Teresa. At #8 (on the left) is...

Casa de Murillo: One of Sevilla’s famous painters, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1618-1682), lived here,

soaking in the ambience of street life and reproducing it in his paintings of cute

beggar children.

Casa de Murillo: One of Sevilla’s famous painters, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1618-1682), lived here,

soaking in the ambience of street life and reproducing it in his paintings of cute

beggar children.

• Directly across from Casa de Murillo is the...

Monasterio de San José del Carmen: This is where St. Teresa stayed when she visited from her hometown of Ávila. The

convent (closed to the public) keeps artifacts of the mystic nun, such as her spiritual

manuscripts.

Monasterio de San José del Carmen: This is where St. Teresa stayed when she visited from her hometown of Ávila. The

convent (closed to the public) keeps artifacts of the mystic nun, such as her spiritual

manuscripts.

Continue north on Calle Santa Teresa, then take the first left on Calle Lope de Rueda, then left again, then right on Calle Reinoso. This street—so narrow that the buildings almost touch—is one of the Barrio’s “kissing lanes.” A popular explanation suggests the buildings were built so close together to provide maximum shade. But remember this was the Jewish ghetto, where all the city’s Jews were forced to live in a very small area. That’s why the streets of Santa Cruz are so narrow.

• Just to the left, the street spills onto the...

Plaza de los Venerables: This square is another candidate for “heart of the Barrio.” The streets branching

off it ooze local ambience. When the Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, this area

became deserted and run-down. But in 1929, for its world’s fair, Sevilla turned the

plaza into a showcase of Andalusian style, adding the railings, tile work, orange

trees, and other too-cute Epcot-like adornments. A different generation of tourists

enjoys the place today, likely unaware that what they’re seeing in Santa Cruz is far

from “authentic” (or, at least, not as old as they imagine).

Plaza de los Venerables: This square is another candidate for “heart of the Barrio.” The streets branching

off it ooze local ambience. When the Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, this area

became deserted and run-down. But in 1929, for its world’s fair, Sevilla turned the

plaza into a showcase of Andalusian style, adding the railings, tile work, orange

trees, and other too-cute Epcot-like adornments. A different generation of tourists

enjoys the place today, likely unaware that what they’re seeing in Santa Cruz is far

from “authentic” (or, at least, not as old as they imagine).

The large, harmonious Baroque-style Hospital de los Venerables (1675), once a retirement home for old priests (the “venerables”), is now a cultural foundation and museum (€4.75, includes audioguide). The highlight is the church and courtyard, featuring a round, sunken fountain. The museum also has a small Velázquez painting of Santa Rufina, one of two patron saints protecting Sevilla. The painting was acquired at a 2007 auction for more than €12 million.

• Continuing west on Calle Gloria, you soon reach the...

Plaza de Doña Elvira: This small square—with orange trees, tile benches, and a stone fountain—sums up our

Barrio walk. Shops sell work by local artisans, such as ceramics, embroidery, and fans.

Plaza de Doña Elvira: This small square—with orange trees, tile benches, and a stone fountain—sums up our

Barrio walk. Shops sell work by local artisans, such as ceramics, embroidery, and fans.

• Cross the plaza and head north along Calle Rodrigo Caro into the...

Plaza de la Alianza: Ever consider a career change? Gain inspiration at the site that once housed the

painting studio of John Fulton (1932-1998; find the small plaque on the other side

of the square), an American who pursued two dreams. Though born in Philadelphia, Fulton

got hooked on bullfighting. He trained in the tacky bullrings of Mexico, then in 1956

he moved to Sevilla, the world capital of the sport. His career as matador was not

top-notch, and the Spaniards were slow to warm to the Yankee, but his courage and

persistence earned their grudging respect. After he put down the cape, he picked up

a brush, making colorful paintings in his Sevilla studio.

Plaza de la Alianza: Ever consider a career change? Gain inspiration at the site that once housed the

painting studio of John Fulton (1932-1998; find the small plaque on the other side

of the square), an American who pursued two dreams. Though born in Philadelphia, Fulton

got hooked on bullfighting. He trained in the tacky bullrings of Mexico, then in 1956

he moved to Sevilla, the world capital of the sport. His career as matador was not

top-notch, and the Spaniards were slow to warm to the Yankee, but his courage and

persistence earned their grudging respect. After he put down the cape, he picked up

a brush, making colorful paintings in his Sevilla studio.

• From Plaza de la Alianza, you can return to the cathedral by turning left (west) on Calle Joaquin Romero Murube (along the wall). Or head northeast on Callejón de Rodrigo Caro, which intersects with Calle Mateos Gago, a street lined with tapas bars.

Sevilla’s cathedral is the third-largest church in Europe (after St. Peter’s at the Vatican and St. Paul’s in London) and the largest Gothic church anywhere. When they ripped down a mosque of brick on this site in 1401, the Reconquista Christians bragged, “We’ll build a cathedral so huge that anyone who sees it will take us for madmen.” They built for 120 years. Even today, the descendants of those madmen proudly display an enlarged photocopy of their Guinness Book of Records letter certifying, “Santa María de la Sede in Sevilla is the cathedral with the largest area: 126.18 meters x 82.60 meters x 30.48 meters high.”

Cost and Hours: €8, €3 for students and those over age 65 (must show ID), kids under age 18 free, includes free entry to the Church of the Savior; July-Aug Mon-Sat 9:30-17:00, Sun 14:30-18:00; Sept-June Mon-Sat 11:00-17:00, Sun 14:30-18:00; last entry to cathedral one hour before closing, last entry to bell tower 30 minutes before closing; WC and drinking fountain just inside entrance and in courtyard near exit, tel. 954-214-971. Most of the website www.catedraldesevilla.es is in Spanish, but following the “vista virtual” links will take you to a virtual tour with an English option.

Crowd-Beating Tip: Though there’s usually not much of a line to buy tickets, you can avoid it altogether by buying your ticket at the Church of the Savior (Iglesia de Salvador), a few blocks north. See that church first, then come to the cathedral and waltz past the line to the turnstile.

Tours: My self-guided tour covers the basics. The €3 audioguide explains each side chapel for anyone interested in all the old paintings and dry details. For €7 you can enjoy Concepción Delgado’s tour instead (see “Tours in Sevilla,” earlier).

Self-Guided Tour: Enter the cathedral at the south end (closest to the Alcázar, with a full-size replica

of the Giralda’s weathervane statue in the patio).

Self-Guided Tour: Enter the cathedral at the south end (closest to the Alcázar, with a full-size replica

of the Giralda’s weathervane statue in the patio).

• First, you pass through the...

Art Pavilion: Just past the turnstile, you step into a room of paintings that once hung in the

church, including works by Sevilla’s two 17th-century masters—Bartolomé Murillo (St. Ferdinand—the king who freed Sevilla from the Moors) and Francisco de Zurbarán (St. John the Baptist in the Desert). Find a painting showing two of Sevilla’s patron saints—Santa Justa and Santa Rufina.

Potters by trade, these two are easy to identify by their pots and palm branches,

and the bell tower symbolizing the town they protect. As you tour the cathedral, keep

track of how many depictions of this dynamic and saintly duo you spot. They’re everywhere.

Art Pavilion: Just past the turnstile, you step into a room of paintings that once hung in the

church, including works by Sevilla’s two 17th-century masters—Bartolomé Murillo (St. Ferdinand—the king who freed Sevilla from the Moors) and Francisco de Zurbarán (St. John the Baptist in the Desert). Find a painting showing two of Sevilla’s patron saints—Santa Justa and Santa Rufina.

Potters by trade, these two are easy to identify by their pots and palm branches,

and the bell tower symbolizing the town they protect. As you tour the cathedral, keep

track of how many depictions of this dynamic and saintly duo you spot. They’re everywhere.

• Walking past a rack of church maps and a WC, enter the actual church. In the center of the church, sit down in front of the...

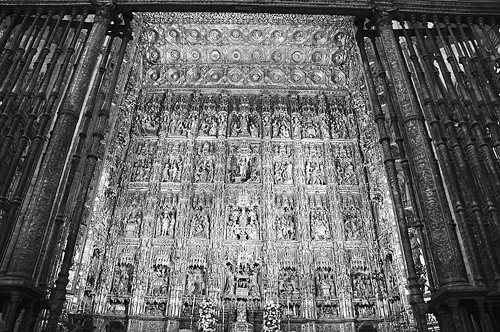

High Altar: If restoration work on the high altar is finished, you’ll be able to look through

the wrought-iron Renaissance grille at what’s called the largest altarpiece (retablo mayor) ever made—65 feet tall, with 44 scenes from the life of Jesus carved from walnut

and chestnut, blanketed by a staggering amount of gold leaf (and dust). (If restoration

is still ongoing, you’ll see a to-scale image of the altar covering the scaffolding.)

The work took three generations to complete (1481-1564). The story is told left to

right, bottom to top. Find Baby Jesus in the manger, in the middle of the bottom row,

then follow his story through the miracles, the Passion, and the Pentecost. Crane

your neck to look way up to the tippy-top, where a Crucifixion adorns the dizzying

summit.

High Altar: If restoration work on the high altar is finished, you’ll be able to look through

the wrought-iron Renaissance grille at what’s called the largest altarpiece (retablo mayor) ever made—65 feet tall, with 44 scenes from the life of Jesus carved from walnut

and chestnut, blanketed by a staggering amount of gold leaf (and dust). (If restoration

is still ongoing, you’ll see a to-scale image of the altar covering the scaffolding.)

The work took three generations to complete (1481-1564). The story is told left to

right, bottom to top. Find Baby Jesus in the manger, in the middle of the bottom row,

then follow his story through the miracles, the Passion, and the Pentecost. Crane

your neck to look way up to the tippy-top, where a Crucifixion adorns the dizzying

summit.

• Turn around and check out the...

Choir: Facing the high altar, the choir features an organ of 7,000 pipes (played Mon-Fri

at the 10:00 Mass, Sun at the 10:00 & 13:00 Mass, not in July-Aug, free for worshippers). A choir area like this one (an

enclosure within the cathedral for more intimate services) is common in Spain and

England, but rare in churches elsewhere. The big, spinnable book holder in the middle

of the room held giant hymnals—large enough for all to chant from in a pre-Xerox age

when there weren’t enough books for everyone.

Choir: Facing the high altar, the choir features an organ of 7,000 pipes (played Mon-Fri

at the 10:00 Mass, Sun at the 10:00 & 13:00 Mass, not in July-Aug, free for worshippers). A choir area like this one (an

enclosure within the cathedral for more intimate services) is common in Spain and

England, but rare in churches elsewhere. The big, spinnable book holder in the middle

of the room held giant hymnals—large enough for all to chant from in a pre-Xerox age

when there weren’t enough books for everyone.

• Now turn 90 degrees to the left and march to find the...

Tomb of Columbus: In front of the cathedral’s entrance for pilgrims are four kings who carry the tomb

of Christopher Columbus. His pallbearers represent the regions of Castile, Aragon,

León, and Navarre (identify them by their team shirts). Columbus even traveled a lot

posthumously. He was buried first in Spain, then in Santo Domingo in the Dominican

Republic, then Cuba, and finally—when Cuba gained independence from Spain, around

1900—he sailed home again to Sevilla. Are the remains actually his? Sevillans like

to think so. (Columbus died in 1506. Five hundred years later, to help celebrate the

anniversary of his death, DNA samples gave Sevillans the evidence they needed to substantiate

their claim.) On the left is a mural of St. Christopher—patron saint of travelers—from

1584. The clock above has been ticking since 1788.

Tomb of Columbus: In front of the cathedral’s entrance for pilgrims are four kings who carry the tomb

of Christopher Columbus. His pallbearers represent the regions of Castile, Aragon,

León, and Navarre (identify them by their team shirts). Columbus even traveled a lot

posthumously. He was buried first in Spain, then in Santo Domingo in the Dominican

Republic, then Cuba, and finally—when Cuba gained independence from Spain, around

1900—he sailed home again to Sevilla. Are the remains actually his? Sevillans like

to think so. (Columbus died in 1506. Five hundred years later, to help celebrate the

anniversary of his death, DNA samples gave Sevillans the evidence they needed to substantiate

their claim.) On the left is a mural of St. Christopher—patron saint of travelers—from

1584. The clock above has been ticking since 1788.

• Facing Columbus, turn right and duck into the first chapel (on your left) to find the...

Antigua Chapel: Within this chapel is the gilded fresco of the Virgin Antigua, the oldest art in

the church. It was actually painted onto a horseshoe-shaped prayer niche of the mosque

formerly on this site. After Sevilla was reconquered in 1248, the mosque served as

a church for about 120 years—until it was torn down to make room for this huge cathedral.

Builders, captivated by the beauty of the Virgin holding the rose and the Christ Child

holding the bird (and knowing that she was considered the protector of sailors in

this port city), decided to save the fresco.

Antigua Chapel: Within this chapel is the gilded fresco of the Virgin Antigua, the oldest art in

the church. It was actually painted onto a horseshoe-shaped prayer niche of the mosque

formerly on this site. After Sevilla was reconquered in 1248, the mosque served as

a church for about 120 years—until it was torn down to make room for this huge cathedral.

Builders, captivated by the beauty of the Virgin holding the rose and the Christ Child

holding the bird (and knowing that she was considered the protector of sailors in

this port city), decided to save the fresco.

• Exiting the chapel, we’ll tour the cathedral counterclockwise. As you explore, note that its many chapels are described in English, and many of the windows have their dates worked into the design. Just on the other side of Columbus, walk through the small chapel and into the...

Sacristy: This space is where the priests get ready each morning before Mass. The Goya painting

above the altar features Justa and Rufina—patron saints of Sevilla who were martyred

in ancient Roman times. They’re always shown with their trademark attributes: the

town bell tower, pots, and palm leaves. I say they’re each holding a bowl of gazpacho (particularly refreshing on hot summer days)

and sprigs of rosemary from local Gypsies (an annoyance even back then). Art historians

claim that since they were potters, they are shown with earthenware, and the sprigs

are palm leaves—symbolic of their martyrdom. Whatever.

Sacristy: This space is where the priests get ready each morning before Mass. The Goya painting

above the altar features Justa and Rufina—patron saints of Sevilla who were martyred

in ancient Roman times. They’re always shown with their trademark attributes: the

town bell tower, pots, and palm leaves. I say they’re each holding a bowl of gazpacho (particularly refreshing on hot summer days)

and sprigs of rosemary from local Gypsies (an annoyance even back then). Art historians

claim that since they were potters, they are shown with earthenware, and the sprigs

are palm leaves—symbolic of their martyrdom. Whatever.

• Two chapels down is the entrance to the...

Main Sacristy: Marvel at the ornate, 16th-century Plateresque dome of the main room, a grand souvenir

from Sevilla’s Golden Age. The intricate masonry resembles lacy silverwork (it’s named

for plata—silver). God is way up in the cupola. The three layers of figures below him show

the heavenly host; relatives in purgatory—hands folded—looking to heaven in hope of

help; and the wretched in hell, including a topless sinner engulfed in flames and

teased cruelly by pitchfork-wielding monsters. Locals use the 110-pound silver religious

float that dominates this room to parade the holy host (communion wafer) through town during

Corpus Christi festivities.

Main Sacristy: Marvel at the ornate, 16th-century Plateresque dome of the main room, a grand souvenir

from Sevilla’s Golden Age. The intricate masonry resembles lacy silverwork (it’s named

for plata—silver). God is way up in the cupola. The three layers of figures below him show

the heavenly host; relatives in purgatory—hands folded—looking to heaven in hope of

help; and the wretched in hell, including a topless sinner engulfed in flames and

teased cruelly by pitchfork-wielding monsters. Locals use the 110-pound silver religious

float that dominates this room to parade the holy host (communion wafer) through town during

Corpus Christi festivities.

• At the far end of the main sacristy, at the left-hand corner, is a door leading to our next stop. (If it’s closed, you can backtrack to the main part of the church and head next door.)

Treasury: The tesoro fills several rooms in the corner of the church. Wander deeper into the treasury

to find a unique oval dome. It’s in the 16th-century chapter room (sala capitular), where monthly meetings take place with the bishop (he gets the throne, while the

others share the bench). The paintings here are by Murillo: a fine Immaculate Conception (1668, high above the bishop’s throne) and portraits of saints important to Sevillans.

Treasury: The tesoro fills several rooms in the corner of the church. Wander deeper into the treasury

to find a unique oval dome. It’s in the 16th-century chapter room (sala capitular), where monthly meetings take place with the bishop (he gets the throne, while the

others share the bench). The paintings here are by Murillo: a fine Immaculate Conception (1668, high above the bishop’s throne) and portraits of saints important to Sevillans.

The wood-paneled “room of ornaments” shows off gold and silver reliquaries, which hold hundreds of holy body parts, as well as Spain’s most valuable crown. The jeweled crown by Manuel de la Torres (the Corona de la Virgen de los Reyes) sparkles with 11,000 precious stones and the world’s largest pearl—used as the torso of an angel.

• Leave the treasury and cross through the church to see...

More Church Sights: First you’ll pass the closed-to-tourists  Royal Chapel, the burial place of several of the kings of Castile (open for worship only—access

from outside), then the

Royal Chapel, the burial place of several of the kings of Castile (open for worship only—access

from outside), then the  Chapel of St. Peter, which is dark but filled with paintings by Francisco de Zurbarán (showing scenes

from the life of St. Peter). At the far corner—past the glass case displaying the

Guinness certificate declaring that this is indeed the world’s largest church by area—is the

entry to the Giralda Bell Tower. You’ll finish your visit here. But for now, continue

your counterclockwise circuit. Near the middle (and high) altar, crane your neck skyward

to admire the

Chapel of St. Peter, which is dark but filled with paintings by Francisco de Zurbarán (showing scenes

from the life of St. Peter). At the far corner—past the glass case displaying the

Guinness certificate declaring that this is indeed the world’s largest church by area—is the

entry to the Giralda Bell Tower. You’ll finish your visit here. But for now, continue

your counterclockwise circuit. Near the middle (and high) altar, crane your neck skyward

to admire the  Plateresque tracery on the ceiling, and take in the enormous

Plateresque tracery on the ceiling, and take in the enormous  Altar de Plata rising up in a side chapel. The gleaming silver altarpiece adorned with statues looks

like a big monstrance, those vessels for displaying the communion wafer.

Altar de Plata rising up in a side chapel. The gleaming silver altarpiece adorned with statues looks

like a big monstrance, those vessels for displaying the communion wafer.

The  Chapel of St. Anthony (Capilla de San Antonio), the last chapel on the right, is used for baptisms. The

Renaissance baptismal font has delightful carved angels dancing along its base. In

Murillo’s painting, Vision of St. Anthony (1656), the saint kneels in wonder as a Baby Jesus comes down surrounded by a choir of angels.

Anthony is one of Iberia’s most popular saints. As he is the patron saint of lost

things, people come here to pray for Anthony’s help in finding jobs, car keys, and

life partners. Above the Vision is The Baptism of Christ, also by Murillo. You don’t need to be an art historian to know that the stained glass

dates from 1685. And by now you must know who the women are....

Chapel of St. Anthony (Capilla de San Antonio), the last chapel on the right, is used for baptisms. The

Renaissance baptismal font has delightful carved angels dancing along its base. In

Murillo’s painting, Vision of St. Anthony (1656), the saint kneels in wonder as a Baby Jesus comes down surrounded by a choir of angels.

Anthony is one of Iberia’s most popular saints. As he is the patron saint of lost

things, people come here to pray for Anthony’s help in finding jobs, car keys, and

life partners. Above the Vision is The Baptism of Christ, also by Murillo. You don’t need to be an art historian to know that the stained glass

dates from 1685. And by now you must know who the women are....

Nearby, a glass case displays the  pennant of Ferdinand III, which was raised over the minaret of the mosque on November 23, 1248, as Christian

forces finally expelled the Moors from Sevilla. For centuries, it was paraded through

the city on special days.

pennant of Ferdinand III, which was raised over the minaret of the mosque on November 23, 1248, as Christian

forces finally expelled the Moors from Sevilla. For centuries, it was paraded through

the city on special days.

Continuing on, stand at the  back of the nave (behind the choir) and appreciate the ornate immensity of the church. Can you see

the angels trumpeting on their Cuban mahogany? Any birds? The massive candlestick

holder to the right of the choir dates from 1560.

back of the nave (behind the choir) and appreciate the ornate immensity of the church. Can you see

the angels trumpeting on their Cuban mahogany? Any birds? The massive candlestick

holder to the right of the choir dates from 1560.

Turn around. To the left is a niche with  Murillo’s Guardian Angel pointing to the light and showing an astonished child the way.

Murillo’s Guardian Angel pointing to the light and showing an astonished child the way.

• Backtrack the length of the church toward the Giralda Bell Tower, and notice the back of the choir’s Baroque pipe organ. The exit sign leads to the Court of the Orange Trees and the exit. But first, some exercise.

Giralda Tower Climb: Your church admission includes entry to the bell tower. Notice the beautiful Moorish

simplicity as you climb to its top, 330 feet up, for a grand city view. The spiraling

ramp was designed to accommodate riders on horseback, who galloped up five times a

day to give the Muslim call to prayer.

Giralda Tower Climb: Your church admission includes entry to the bell tower. Notice the beautiful Moorish

simplicity as you climb to its top, 330 feet up, for a grand city view. The spiraling

ramp was designed to accommodate riders on horseback, who galloped up five times a

day to give the Muslim call to prayer.

• Go back down into the cathedral interior, then visit the...

Court of the Orange Trees: Today’s cloister was once the mosque’s Court of the Orange Trees (Patio de los Naranjos).

Twelfth-century Muslims stopped at the fountain in the middle to wash their hands,

face, and feet before praying. The ankle-breaking lanes between the bricks were once

irrigation streams—a reminder that the Moors introduced irrigation to Iberia. The

mosque was made of bricks; the church is built of stone. The only remnants of the

mosque today are the Court of the Orange Trees, the Giralda Bell Tower, and the site

itself.

Court of the Orange Trees: Today’s cloister was once the mosque’s Court of the Orange Trees (Patio de los Naranjos).

Twelfth-century Muslims stopped at the fountain in the middle to wash their hands,

face, and feet before praying. The ankle-breaking lanes between the bricks were once

irrigation streams—a reminder that the Moors introduced irrigation to Iberia. The

mosque was made of bricks; the church is built of stone. The only remnants of the

mosque today are the Court of the Orange Trees, the Giralda Bell Tower, and the site

itself.

• You’ll exit the cathedral through the Court of the Orange Trees (if you need to use the WCs, they’re at the far end of the courtyard, downstairs). As you leave, look back from the outside and notice the arch over the...

Moorish-Style Doorway: As with much of the Moorish-looking art in town, it’s actually Christian—the two

coats of arms are a giveaway. The relief above the door shows the Bible story of Jesus

ridding the temple of the merchants...a reminder to contemporary merchants that there

will be no retail activity in the church. The plaque on the right honors Miguel de

Cervantes, the great 16th-century Spanish writer. It’s one of many plaques scattered

throughout town showing places mentioned in his books. (In this case, the topic was

pickpockets.) The huge green doors predate the church. They are a bit of the surviving

pre-1248 mosque—wood covered with bronze. Study the fine workmanship.

Moorish-Style Doorway: As with much of the Moorish-looking art in town, it’s actually Christian—the two

coats of arms are a giveaway. The relief above the door shows the Bible story of Jesus

ridding the temple of the merchants...a reminder to contemporary merchants that there

will be no retail activity in the church. The plaque on the right honors Miguel de

Cervantes, the great 16th-century Spanish writer. It’s one of many plaques scattered

throughout town showing places mentioned in his books. (In this case, the topic was

pickpockets.) The huge green doors predate the church. They are a bit of the surviving

pre-1248 mosque—wood covered with bronze. Study the fine workmanship.

Giralda Tower Exterior: Step across the street from the exit gate and look at the bell tower. Formerly a Moorish minaret from which Muslims were called to prayer, it became the cathedral’s bell tower after the Reconquista. A 4,500-pound bronze statue symbolizing the Triumph of Faith (specifically, the Christian faith over the Muslim one) caps the tower and serves as a weather vane (in Spanish, girar means “to rotate”—so a giraldillo is something that rotates). Locals actually use it to predict the weather. (If the wind is blowing from the southwest, it means moist ocean air will soon bring rain.) In 1356, the original top of the tower fell. You’re looking at a 16th-century Christian-built top with a ribbon of letters proclaiming, “The strongest tower is the name of God” (you can see Fortísima—“strongest”—from this vantage point).

Now circle around for a close look at the corner of the tower at ground level. Needing more strength than their bricks could provide for the lowest section of the tower, the Moors used Romancut stones. You can actually read the Latin chiseled onto one of the stones 2,000 years ago. The tower offers a brief recap of the city’s history—sitting on a Roman foundation, a long Moorish period capped by our Christian age. Today, by law, no building can be higher than the statue atop the tower.

• Your cathedral tour is finished. If you’ve worked up an appetite, get out your map and make your way a few blocks for some...

Nun-Baked Goodies: Stop by the El Torno Pasteleria de Conventos, a co-op where various orders of cloistered

nuns send their handicrafts (such as babies’ baptismal dresses) and baked goods to

be sold. “El Torno” is the lazy Susan that the cloistered nuns spin to sell their

cakes and cookies without being seen. You won’t actually see the torno (this shop is staffed by non-nuns), but this humble little hole-in-the-wall shop

is worth a peek, and definitely serves the best cookies, bar nun. It’s located through the passageway at 24 Avenida

de la Constitución, immediately in front of the cathedral’s biggest door: Go through

the doorway marked Plaza del Cabildo into the quiet courtyard (Sept-July Mon-Fri 10:00-13:30 & 17:00-19:30, Sat-Sun 10:30-14:00,

closed Aug, Plaza del Cabildo 2, tel. 954-219-190).

Nun-Baked Goodies: Stop by the El Torno Pasteleria de Conventos, a co-op where various orders of cloistered

nuns send their handicrafts (such as babies’ baptismal dresses) and baked goods to

be sold. “El Torno” is the lazy Susan that the cloistered nuns spin to sell their

cakes and cookies without being seen. You won’t actually see the torno (this shop is staffed by non-nuns), but this humble little hole-in-the-wall shop

is worth a peek, and definitely serves the best cookies, bar nun. It’s located through the passageway at 24 Avenida

de la Constitución, immediately in front of the cathedral’s biggest door: Go through

the doorway marked Plaza del Cabildo into the quiet courtyard (Sept-July Mon-Fri 10:00-13:30 & 17:00-19:30, Sat-Sun 10:30-14:00,

closed Aug, Plaza del Cabildo 2, tel. 954-219-190).

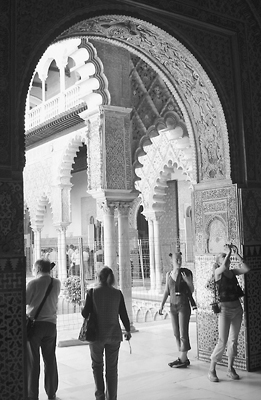

Originally a 10th-century palace built for the governors of the local Moorish state, this building still functions as a royal palace—the oldest in use in Europe. The core of the palace features an extensive 14th-century rebuild, done by Muslim workmen for the Christian king, Pedro I (1334-1369). Pedro was nicknamed either “the Cruel” or “the Just,” depending on which end of his sword you were on. Pedro’s palace embraces both cultural traditions.

Today, visitors can enjoy several sections of the Alcázar. Spectacularly decorated halls and courtyards have distinctive Islamic-style flourishes. Exhibits call up the era of Columbus and Spain’s New World dominance. The lush, sprawling gardens invite exploration. Even the palatial rooms used by today’s king and queen can be visited (reservations required).

Cost and Hours: €8.50; €2 for students and seniors over 65—must show ID, free for children under 16; ticket also includes Antiquarium at Plaza de la Encarnación, April-Sept daily 9:30-19:00, Oct-March daily 9:30-17:00, tel. 954-502-324, www.patronato-alcazarsevilla.es.

Crowd-Beating Tips: Tour groups clog the palace and rob it of any mystery in the morning (especially on Tue); come as late as possible.

Tours: The fast-moving €4 audioguide gives you an hour of information as you wander. My self-guided tour hits the highlights, or you could consider Concepción Delgado’s Alcázar tour (see “Tours in Sevilla,” earlier).

The Upper Royal Apartments can only be visited with a separate tour, reserved in advance (€4.20, includes audioguide, must check bags in provided lockers). Groups leave every half-hour from 10:00 to 13:30—if interested, book a spot as soon as you arrive at the Alcázar. You tour in a small group of 15 people, escorted by a security guard, following a 25-minute audioguide. For some it’s worth it just to escape the mobs in the rest of the palace.

Self-Guided Tour: This royal palace is decorated with a mix of Islamic and Christian elements—a style called Mudejar. It’s a thought-provoking

glimpse of a graceful Al-Andalus (Moorish) world that might have survived its Castilian

conquerors...but didn’t. The floor plan is intentionally confusing, to make experiencing

the place more exciting and surprising. While Granada’s Alhambra was built by Moors

for Moorish rulers, what you see here is essentially a Christian ruler’s palace, built

in the Moorish style.

Self-Guided Tour: This royal palace is decorated with a mix of Islamic and Christian elements—a style called Mudejar. It’s a thought-provoking

glimpse of a graceful Al-Andalus (Moorish) world that might have survived its Castilian

conquerors...but didn’t. The floor plan is intentionally confusing, to make experiencing

the place more exciting and surprising. While Granada’s Alhambra was built by Moors

for Moorish rulers, what you see here is essentially a Christian ruler’s palace, built

in the Moorish style.

• Buy your ticket and enter through the turnstiles. Pass through the garden-like Patio of the Lions and through the arch into a courtyard called the . . .

Patio de la Montería (Courtyard of the Hunt): Get oriented. The palace’s main entrance is directly ahead, through the elaborately

decorated facade. WCs are in the far-left corner. In the far-right corner is the staircase

(and ticket booth) for the Upper Royal Apartments—reserve an entry time now, if you’re

interested (see details at the end of this tour).

Patio de la Montería (Courtyard of the Hunt): Get oriented. The palace’s main entrance is directly ahead, through the elaborately

decorated facade. WCs are in the far-left corner. In the far-right corner is the staircase

(and ticket booth) for the Upper Royal Apartments—reserve an entry time now, if you’re

interested (see details at the end of this tour).

The palace complex was built over many centuries. It has rooms and decorations from the many rulers who’ve lived here. Moorish caliphs built the original 10th-century palace and gardens. After Sevilla was Christianized, King Pedro I built the most famous part of the complex. During Spain’s Golden Age, Ferdinand and Isabel and, later, their grandson Charles V lived here; they all left their mark. Successive monarchs added still more luxury. And today’s king and queen still use the palace’s upper floor as one of their royal residences.

• Before entering the heart of the palace, start in the wing to the right of the courtyard. Step inside.

Admiral’s Room (Cuarto del Almirante): When Queen Isabel debriefed Columbus at the Alcázar after his New World discoveries,

she realized this could be big business. She created this wing in 1503 to administer

Spain’s New World ventures. In these halls, Columbus recounted his travels, Ferdinand

Magellan planned his around-the-world cruise, and mapmaker Amerigo Vespucci tried

to come up with a catchy moniker for that newly discovered continent.

Admiral’s Room (Cuarto del Almirante): When Queen Isabel debriefed Columbus at the Alcázar after his New World discoveries,

she realized this could be big business. She created this wing in 1503 to administer

Spain’s New World ventures. In these halls, Columbus recounted his travels, Ferdinand

Magellan planned his around-the-world cruise, and mapmaker Amerigo Vespucci tried

to come up with a catchy moniker for that newly discovered continent.

In the pink-and-red Audience Chamber (once a chapel), the altarpiece painting is of St. Mary of the Navigators (Santa María de los Navegantes, by Alejo Fernández, 1530s). The Virgin—the patron saint of sailors and a favorite of Columbus—keeps watch over the puny ships beneath her. Her cape seems to protect everyone under it—even the Native Americans in the dark background (the first time “Indians” were painted in Europe).

Standing beside the Virgin (on the right, dressed in gold, joining his hands together in prayer) is none other than Christopher Columbus. He stands on a cloud, because he’s now in heaven (as this was painted a few decades after his death). Notice that Columbus is blond. Columbus’ son said of his dad: “In his youth his hair was blond, but when he reached 30, it all turned white.” Many historians believe this to be the earliest known portrait of Columbus. If so, it also might be the most accurate. On the left side of the painting, the man with the gold cape is King Ferdinand.

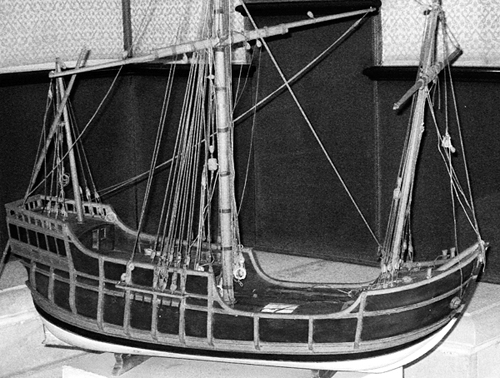

Left of the painting is a model of Columbus’ Santa María, his flagship and the only one of his three ships not to survive the 1492 voyage. Columbus complained that the Santa María—a big cargo ship, different from the sleek Niña and Pinta caravels—was too slow. On Christmas Day it ran aground off present-day Haiti and tore a hole in its hull. The ship was dismantled to build the first permanent structure in America, a fort for 39 colonists. (After Columbus left, the natives burned the fort and killed the colonists.) Opposite the altarpiece (in the center of the back wall) is the family coat of arms of Columbus’ descendants, who now live in Spain and Puerto Rico. Using Columbus’ Spanish name, it reads: “To Castile and to León, Colón gave a new world.”

Return to the still-used reception room, filled with big canvases. The biggest painting (and most melodramatic) shows the turning point in Sevilla’s history: King Ferdinand III humbly kneels before the bishop, giving thanks to God for helping him liberate the city from the Muslims (in 1248). Ferdinand promptly turned the Alcázar of the caliphs into the royal palace of Christian kings.

Pop into the room beyond the grand piano for a look at ornate fans (mostly foreign and well-described in English). A long painting shows 17th-century Sevilla during Holy Week. Follow the procession, which is much like today’s, with traditional floats carried by teams of men and followed by a retinue of penitents.

• Return to the Patio de la Montería. Face the impressive entrance facade of the...

Palace of King Pedro I (Palacio del Rey Pedro I): This is the entrance to the 14th-century nucleus of the complex. The facade’s elaborate

blend of Islamic tracery and Gothic Christian elements introduces us to the Mudejar

style seen throughout Pedro’s part of the palace.

Palace of King Pedro I (Palacio del Rey Pedro I): This is the entrance to the 14th-century nucleus of the complex. The facade’s elaborate

blend of Islamic tracery and Gothic Christian elements introduces us to the Mudejar

style seen throughout Pedro’s part of the palace.

• Enter the palace. Pass through the Vestibule (impressive, yes, but we’ll see better), and continue left through the maze of rooms and passageways until you emerge into the big courtyard with a long pool in the center. This is the...

Courtyard of the Maidens (Patio de las Doncellas): You’ve reached the center of King Pedro’s palace. It’s an open-air courtyard, surrounded

by rooms. In the center is a long, rectangular reflecting pool. Like the Moors who

preceded him, Pedro built his palace around water. The pool has four (covered) cisterns,

two at each end. They distribute water to the four quadrants of the palace and—symbolically—to

the four corners of the world.

Courtyard of the Maidens (Patio de las Doncellas): You’ve reached the center of King Pedro’s palace. It’s an open-air courtyard, surrounded

by rooms. In the center is a long, rectangular reflecting pool. Like the Moors who

preceded him, Pedro built his palace around water. The pool has four (covered) cisterns,

two at each end. They distribute water to the four quadrants of the palace and—symbolically—to

the four corners of the world.

King Pedro cruelly abandoned his wife and moved into the Alcázar with his mistress, then hired Muslim workers from Granada to re-create the romance of that city’s Alhambra in Sevilla’s stark Alcázar. The designers created a microclimate engineered for coolness: water, plants, pottery, thick walls, and darkness. This palace is considered Spain’s best example of the Mudejar style. Stucco panels with elaborate designs, colorful ceramic tiles, coffered wooden ceilings, and lobed arches atop slender columns create a refined, pleasing environment. The elegant proportions and symmetry of this courtyard are a photographer’s delight.

• Explore the rooms branching off the courtyard. Through the door at the end of the long reflecting pool is the palace’s most important room, called the...

Hall of the Ambassadors (Salón de Embajadores): Here, in his throne room, Pedro received guests and caroused in luxury. The room

is a cube topped with a half-dome, like many important Islamic buildings. In Islam,

the cube represents the earth, and the dome is the starry heavens. In Pedro’s world,

the symbolism proclaimed that he controlled heaven and earth. Islamic horseshoe arches

stand atop columns with golden capitals. Lattice windows (a favorite of Pedro’s) are

above those.

Hall of the Ambassadors (Salón de Embajadores): Here, in his throne room, Pedro received guests and caroused in luxury. The room

is a cube topped with a half-dome, like many important Islamic buildings. In Islam,

the cube represents the earth, and the dome is the starry heavens. In Pedro’s world,

the symbolism proclaimed that he controlled heaven and earth. Islamic horseshoe arches

stand atop columns with golden capitals. Lattice windows (a favorite of Pedro’s) are

above those.

The stucco on the walls is molded with interlacing plants, geometrical shapes, and Arabic writing. Imagine, here in a Christian palace, that the walls are inscribed with unapologetically Muslim sayings: “None but Allah conquers” and “Happiness and prosperity are benefits of Allah, who nourishes all creatures.” The artisans added propaganda phrases such as “Dedicated to the magnificent Sultan Pedro—thanks to God!”

The Mudejar style also includes Christian motifs. Find the row of kings, high up at the base of the dome, chronicling all of Spain’s rulers from the 600s to the 1600s. Throughout the palace, you’ll see coats of arms—including the castle of Castile and the lion of León. There are also natural objects (shells and birds) you wouldn’t normally find in Islamic decor, which traditionally avoids realistic images of nature.

Wander through adjoining rooms. Straight ahead from the Hall of the Ambassadors, in the Philip II Ceiling Room (Salón del Techo de Felipe II), look above the arches to find peacocks, falcons, and other birds amid interlacing vines. Imagine day-to-day life in the palace—with VIP guests tripping on the tiny but jolting steps.

• Make your way to the second courtyard, nearby (in the Hall of the Ambassadors, face the Courtyard of the Maidens, then walk to the left). This smaller courtyard is the...

Courtyard of the Dolls (Patio de las Muñecas): This delicate courtyard was for the king’s private and family life. Originally, the

center of the courtyard had a pool, cooling the residents and reflecting the decorative

patterns once brightly painted on the walls. The columns are different colors—alternating

white, black, and pink marble. (Pedro’s original courtyard was a single story. The

upper floors and skylight were added centuries later.) The courtyard’s name comes

from the tiny doll faces found at the base of one of the arches. Circle the room and

try to find them.

Courtyard of the Dolls (Patio de las Muñecas): This delicate courtyard was for the king’s private and family life. Originally, the

center of the courtyard had a pool, cooling the residents and reflecting the decorative

patterns once brightly painted on the walls. The columns are different colors—alternating

white, black, and pink marble. (Pedro’s original courtyard was a single story. The

upper floors and skylight were added centuries later.) The courtyard’s name comes

from the tiny doll faces found at the base of one of the arches. Circle the room and

try to find them.

• The long adjoining room with the gilded ceiling, the Prince’s Room (Cuarto del Príncipe), was Queen Isabel’s bedroom, where she gave birth to a son, Prince Juan.

Return to the Courtyard of the Maidens. Look up and notice the second story. Isabel’s grandson, Charles V, added it in the 16th century. See the difference in styles: Mudejar below (lobed arches and elaborate tracery), and Renaissance above (round arches and less decoration).

As you stand in the courtyard with your back to the Hall of the Ambassadors, the door in the middle of the right side leads to the...

Charles V Ceiling Room (Salón del Techo del Carlos V): Emperor Charles V, who ruled Spain at its peak of New World wealth, expanded the

palace. The reason? His marriage to his beloved Isabel, which took place in this room.

Devoutly Christian, Charles celebrated his wedding night with a midnight Mass, and

later ordered the Mudejar ceiling in this room to be replaced with a less Islamic

(but no less impressive) one.

Charles V Ceiling Room (Salón del Techo del Carlos V): Emperor Charles V, who ruled Spain at its peak of New World wealth, expanded the

palace. The reason? His marriage to his beloved Isabel, which took place in this room.

Devoutly Christian, Charles celebrated his wedding night with a midnight Mass, and

later ordered the Mudejar ceiling in this room to be replaced with a less Islamic

(but no less impressive) one.

• We’ve seen the core of King Pedro’s palace, with the additions by his successors. Return to the Courtyard of the Maidens, turn right, and find the staircase in the corner. This leads up to rooms decorated with bright ceramic tiles. Pass through the chapel and into two big, long, parallel rooms, the...

Banquet Hall (Salón Gótico) and Hall of Tapestries (Salón Tapices): The first room you enter is the big, airy banquet hall where Charles and Isabel’s

wedding reception was held. Tiles of yellow, blue, green, and orange line the room,

some decorated with whimsical human figures with vase-like bodies. The windows open

onto views of the gardens.

Banquet Hall (Salón Gótico) and Hall of Tapestries (Salón Tapices): The first room you enter is the big, airy banquet hall where Charles and Isabel’s

wedding reception was held. Tiles of yellow, blue, green, and orange line the room,

some decorated with whimsical human figures with vase-like bodies. The windows open

onto views of the gardens.

Next door, the walls are hung with large Brussels-made tapestries showing the conquests, trade, and industriousness of Charles’ prosperous reign. (The highlights are described in Spanish along the top and in Latin along the bottom.) The map tapestry of the Mediterranean world has south pointing up. Find Genova, Italy, on the bottom; Africa on top; Lisbon (Liboa) on the far right; and the large city of Barcelona in between. The artist included himself holding the legend—with a scale in both leagues and miles.

• At the far end of the Banquet Hall, head outside to...

The Gardens: This space is full of tropical flowers, feral cats, cool fountains, and hot tourists.

The intimate geometric zone nearest the palace is the Moorish garden. The far-flung

garden beyond that was the backyard of the Christian ruler. The elevated walkway (Galería del Grutesco—the Grotto Gallery) along the left side of the gardens provides

fine views. (Enter it from the palace end.) Descending to the lower garden, find the

entrance to the Baths of María de Padilla—an underground rainwater cistern named for Pedro’s mistress. (Renovation of the baths

should be complete by the time you visit in 2013.)

The Gardens: This space is full of tropical flowers, feral cats, cool fountains, and hot tourists.

The intimate geometric zone nearest the palace is the Moorish garden. The far-flung

garden beyond that was the backyard of the Christian ruler. The elevated walkway (Galería del Grutesco—the Grotto Gallery) along the left side of the gardens provides

fine views. (Enter it from the palace end.) Descending to the lower garden, find the