The North Atlantic trade circuit, the racial contract, encountering others’ pasts

This, the second of four chapters of film analysis, explores two films about intercultural encounters across the Atlantic which meditate on colonial modernity’s origins and contemporary form: Como Era Gostoso o Meu Francê s/How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman (Brazil, 1971), and Tambié n la lluvia/Even the Rain (Spain/Bolivia/Mexico/France, 2010). The films cover early Sixteenth Century colonial interactions between Europeans and indigenous Americans, with implicit resonances for the then Cold War present (How Tasty), and the neo-colonialism of contemporary globalisation (Even the Rain). These films are characterised by the time-images of the opsign and the crystal of time, respectively. They both conclude with an affection-image in which a direct address to the viewer breaches the fourth wall. The five-hundred-year transnational history on display in these time-images is that of the North Atlantic trade circuit. The films together explore how the entangled histories of white Europeans and indigenous cultures from 1492 onwards – histories integrally linked to the exploitation of the environments and natural resources they traverse (specifically brazil wood (How Tasty) and water (Even the Rain)) – have been rendered ‘lost pasts’.

The encounter with these lost pasts enables viewer hesitation with regard to what Charles W. Mills calls the racial contract, the role of which in determining this period of world history continues into the present. In How Tasty, the encounter with an eradicated indigenous past momentarily turns the racial contract on its head, as those typically excluded by it usurp the place occupied by the coloniser. The viewer is thus, perhaps unsettlingly for many, aligned with the position of the colonised. Even the Rain, similarly, emphasises the difficulty Europeans have engaging with the other (during the history of colonial modernity, as today), whilst foregrounding the crystal histories though which access can be granted to the lost pasts of world memory. In neither film do we learn about the history of the North Atlantic trade circuit per se. Rather, we encounter the awareness that it has denied coevalness to the people upon whose exploitation the global centrality of Europe was built after 1492.

Time-images: Others’ pasts

In How Tasty, the encounter between a would-be European coloniser in the early Sixteenth Century and an indigenous tribe of Tupi Indians in what is now Brazil occurs in a pure optical situation (or opsign). Opsigns are discussed by Deleuze amongst his time-image categories, to describe situations in which characters are unable to act so as to influence their destiny. Opsigns are actual images, but in them we see the passing of time for itself because they do not function within a sensory-motor oriented progression of images. In opsigns we encounter situations in which the continuity from perception to action has been suspended. Thus the inhabitant of the interval between the two becomes a (hesitant) seer, unable to act decisively upon what is perceived (as might a doer in the movement-image (1985, 1–2)). Tellingly, this suspended temporal moment, in which the European discoverer of the New World finds himself without the capacity to construct history, is positioned at the origins of colonial modernity.

In Even the Rain, the defining time-image is the crystal of time, which encapsulates the coexistence of an actual present that passes and a virtual past that is preserved (1985, 66–94). A film-within-a-film conceit is used to indicate how present-day events under globalisation mirror those of the initial colonial encounter between Europeans and the New World. Whilst corporations have replaced conquistadores, the struggles over ownership of natural resources (gold in the Sixteenth Century, water in the Twenty-First), and the resistance of the indigenous population against exploitation, are indiscernible.

Both of the time-images introduce an uncertainty to history – European colonisation inverted, with a Frenchman enslaved and eaten by indigenous Americans (How Tasty); globalisation’s exploitation of the Global South as a resistance struggle which (albeit temporarily) includes Europeans (Even the Rain). The hesitation which this viewing experience creates culminates each time in an affection-image in which the persistence of the possibility of another’s past is emphasised. However, there is a marked difference in the type of affection-image, and the way it functions, to that of the any-space-whatever explored in the previous chapter. Here, an affection-image directly confronts the viewer with the gaze of an indigenous American, representative of all those from the underside of colonial modernity. The affection-image confronts us with the knowledge that another past exists (more concretely, that other pasts exist) subsumed within colonial modernity. In this case, a past in which European and indigenous cultures were – and are – intertwined.

As noted in Chapter 3, the close-up of the face typically belongs to the anthropocentric sensory-motor regime of Cinema 1. In the movement-image, the most rudimentary of cinematic journeys into the past, the flashback (conventionally commencing with a facial close-up) affirms a linear timeline. This is a temporal regime distinct from the more associative, non-linear slippages between the virtual sheets of the past of the time-image. Yet, what these close-ups do in the films analysed here, appearing at the close of stories in which Europeans encounter indigenous Americans, is to confront viewers with the moment of the (re)emergence of a lost past, its virtual, latent possibility, before it is reterritorialised into any one (or anyone else’s) history, as it would be in the movement-image.

As Amy Herzog clarifies with regard to the temporal uncertainty in the affection-image, it ‘exists as a kind of tableau vivant, vibrating immobility, in a perpetual state of inbetween-ness. [… ] The face as affection-image marks a threshold between worlds, a moment of forking time where various potential paths, actions and lines of flight intersect’ (2008, 68–69). Hence, what looks out at us from the screen in How Tasty and Even the Rain is a temporal hesitation, a possibility of another history which by definition cannot actualise. This is because, by definition, affect is something forming, but not formed. As Gregory Flaxman and Elena Oxman indicate: ‘in cinema [… ] the face can become a hesitation, an affective intensity that prolongs itself in an expression in relation to something “as yet” to be seen’ (2008, 46). Yet, more specifically, these affection-images cannot actualise by definition, both because the faces emerge at the end of the films (leaving no narrative time left for actualising the potential of the pasts), but – more crucially – because of the exclusion of the people whose faces we see from Eurocentric history. Hence, in these films the faces of indigenous Americans provide an encounter with the possibility of the myriad human pasts of world history which belie the recent destructive past of colonial modernity.

From these faces we do not learn much, if anything, of the excluded histories they represent: only that such (lost) pasts exist. The faces staring back at us from colonial history, then, deny the denial of coevalness by indicating the possible, virtual histories which subsist along with the accepted history of colonial modernity. Hence these two time-image films provide different examples of a similar process of historical reconsideration, undertaken from different geographical and geopolitical perspectives, on the history of the North Atlantic trade circuit.

Transnational history: The North Atlantic trade circuit

From the Fifteenth Century onwards, the North Atlantic trade circuit altered the world system in favour of European dominance (Dussel 1992, 11, 88; 1998a, 5).1 The circuit was a triangular route. Ships leaving Europe would find port on the coast of Africa, take on board slaves, and sail on the trade winds to the Americas. Their cargoes were sold and the holds filled with the mineral wealth mined from the ground, along with the tobacco, sugar, cotton and other such fruits of slave labour. Westerly winds and the current of the Gulf Stream propelled their return to Europe. The raw materials of the Americas were manufactured into goods (textiles, rum, etc.) destined for the next fleets leaving for Africa. This triangular route was the engine which moved the world system, facilitated the Columbian Exchange, and commenced the Anthropocene (see Introduction).

The study of Atlantic history is widespread (Shannon 2004; Egerton et al. 2007; Canny and Morgan 2011, et al.), propelled by post-war work on colonial history and the African diaspora in particular (Egerton et al. 2007, 3). One of the most famous texts remains Paul Gilroy’s The Black Atlantic (1993), in which he explores this ‘intercultural and transnational formation’ to reveal the complexities of how the slave plantations of the Americas (as such ‘inside modernity’) remained connected to premodern histories (e.g. via oral histories of African ancestry) ‘outside’ modernity. Accordingly, the Black Atlantic is, for Gilroy, at once inside and outside of modernity (57–58). Thus Robert Stam and Ella Shohat explore the term ‘Atlantic Enlightenment’ (2012, xiii) to indicate how post-World War Two ‘culture wars’ across the postcolonial Atlantic can be understood as part of a struggle over colonisation/decolonisation of the region, which stretches back to 1492 (1). Not only the Black, but also the White and Red Atlantics, respectively, all indicate a history of being influenced by, and influencing, colonial modernity: transnational histories intertwining Europe, Africa, and the Americas in the North Atlantic trade circuit. In this chapter, the focus remains primarily on (how the films explore) the White Atlantic.

Aní bal Quijano argues that the discovery of America brought new ‘intersubjectivities’ (2000, 547), new relationships between European, American and other peoples. European wealth based on the exploitation of labour and resources from Africa and the Americas ensured that new, intertwined identities emerged between ‘modern’ Europeans and ‘primitive’ non-Europeans. As noted in the Introduction, the claims to legitimacy of the former position relied entirely on the maintenance of the supposed veracity of the ‘primitivism’ of the latter, a view built upon hierarchical racial cartographies which emerged after 1492. Hence, for Quijano, the Americas and Europe have a shared history of development as modern geocultural entities, Europe’s emergence as a new global centre being intertwined with the encounter between Europeans and others in the exploited global periphery. ‘[S]tarting with America, a new space/time was constituted materially and subjectively; this is what the concept of modernity names’ (2000, 547; 2008, 195).

It is this intertwined Atlantic history which is negotiated in the two films under discussion. Thus, whilst they can be grouped with period films about Atlantic discovery or encounter – Aguirre, der Zorn Gottes/Aguirre, Wrath of God (West Germany, 1972), The Mission (UKI/France, 1986), Black Robe (Canada/Australia/USA, 1991), 1492: Conquest of Paradise (France/Spain, 1992), Sankofa (USA/UK/Ghana/Burkina Faso/Germany, 1993), Brava gente brasileira/Brave New Land (Brazil/Portugal, 2000), The New World (USA/UK, 2005), Embrace of the Serpent (Colombia/Venezuela/Argentina, 2016), The Lost City of Z (USA, 2016) – the two under discussion, which focus on the intertwining of European and indigenous histories (the White – experience of the – Atlantic), actually belong with a different trend that considers intertwined subjectivities under colonial modernity much more broadly (see further below). In a context wherein the intertwining of cultures from centre and peripheries which characterises the history of the Atlantic is now played out globally, this trend focuses on the intertwining of histories, as much as people, all over the world (Global North and South now co-existing, globally). It does not solely concern the historical nature of the North Atlantic trade circuit, then, even if the two chosen films here do, but the racial contract which underpins the history of colonial modernity more broadly (encompassing the Atlantic initially, but then spreading globally as per the world system). The two films explored herein are just the most explicit in connecting globalisation’s rendering precarious of Eurocentrism (and its attendant white supremacy) to the origins of the rise of Europe via the North Atlantic trade circuit.

Encountering the other: The racial contract

This particular transnational history is marked by what Caribbean philosopher Charles W. Mills considers the (unacknowledged) racial contract which underpins (or more accurately, undermines) the social contract. Mills, like Dussel, opposes the developmental narrative which sees the West’s centrality to the globalised present as the result of European exceptionalism. After all, the Enlightenment, the industrial revolution, the emergence of democracy with the French Revolution and the American Wars of Independence (as well as the idea that the social contract elevates humanity out of a supposed state of nature and the introduction of ‘race’ as a category (the idea of modernity)), all coexist with the chequered history of European colonialism (1997, 62–64). Instead, then, Mills details how the racial contract privileges white people over all others (7). It effectively uses the idea of a preceding state of nature to delineate between those humans who are deemed to have left it, and those (more akin to animals) who still dwell within it. For Mills, the racial contract is thus ‘the truth’ of the social contract (64).

Like Dussel, Quijano and others, Mills considers the racial contract to be ‘clearly historically locatable in the [… ] events marking the creation of the modern world by European colonialism and the voyages of “discovery” now [… ] more appropriately called expeditions of conquest’ (1997, 20). It is the underside of modernity, precisely, which is subjugated by the Christian, supposedly civilising mission emanating from Europe after 1492 (22).

[W]e live in a world which has been foundationally shaped for the past five hundred years by the realities of European domination and the gradual consolidation of global white supremacy. Thus not only is the racial contract ‘real’, but – whereas the social contract is characteristically taken to be establishing the legitimacy of the nation-state, and codifying morality and law within its boundaries – the racial contract is global, involving a tectonic shift of the ethicojuridicial basis of the planet as a whole, the division of the world, as Jean-Paul Sartre put it [… ] between ‘men’ and ‘natives’.

(20)

In 1492, just as Spain was expanding Westwards though colonialism, it was equally securing the borders of Christian Europe with the Reconquista, a military campaign imbricated as it was in ‘Judeophobia and Islamophobia’ (Shohat 2013, 51). For Ella Shohat, the way of considering otherness in the behaviour of the conquistadores towards the indigenous peoples of the Americas was not very different from that shown towards those ‘from’ areas to the East of Europe (50–55). For this reason, as Mills notes, the racial contract should be understood as global, and as spreading historically with the growth of the Eurocentric world system.

The racial contract enables a more distinct interpretation than is typical when films about encounters with the New World are explored – even when diverse examples are considered from a world of cinemas with a view to engagement with pasts silenced from official historical accounts.2 Usually, the emphasis remains on how American history was impacted upon by the intertwining of cultures brought about by European colonisation (e.g. McAuley 2013, 515). Even when the Columbian Exchange is visualised in a film like The New World, scholarly engagement typically explores its re-imagining of not the transnational history of the phenomenon, but of American history (e.g. Burgoyne 2010, 120–142). By contrast, the chosen films are analysed with respect to a proliferation of contemporary movies about encounters between different cultures under globalisation (far too numerous to enumerate in full) as diverse as Calendar (Armenia/Canada/Germany, 1993) and La Promesse/The Promise (Belgium/France/Luxembourg/Tunisia, 1996) in the 1990s, through to Un cuento chino/Chinese Take Away (Argentina/Spain, 2011) and Le Havre (Finland/France/Germany, 2011) in the early 2010s. Such films illuminate the intertwined nature of human histories (from colonial pasts to neoliberal presents), in our contemporary, global border-crossing world. Hence, in the two examples focusing on Atlantic history, we see the historical depth which belies this feature of globalisation, in the normative construction of Eurocentric/other (world) histories characterising colonial modernity.

How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman

How Tasty is set in 1557, in what is now the State of Rio de Janeiro. The protagonist, if he can be called that, is Jean (Arduí no Colassanti), a French sailor. On his arrival in the New World without a wife, Jean attempts to become friendly with the indigenous Americans. For this impropriety he is accused of mutiny by his puritanical brethren and dumped into the sea in chains. Miraculously, he re-emerges onto dry land (see Figure 4.1) and is captured by Tupiniquim Indians, allies of the Portugese. Forced to fight alongside them due to his expertise with cannon, he is recaptured by rival Tupinambá Indians (allies of the French), who believe him to be Portugese. The Tupinambá decide to keep Jean alive for eight months before sacrificing and eating him. During this time, he is the lover of Sebiopepe (Ana Maria Magalhã es) whose husband has been killed in battle. Jean integrates into the tribe, using his skill with cannon to fight alongside the Tupinambá against the Portugese, but he is unable to escape. Amusingly, his attempts to hijack Tupinambá myths of ancestral origin to establish himself as a god-like figure (emulating the mythical ancestor Mair, who taught the use of fire, food and weapons (Peñ a 1995, 197; Sadlier 2003, 66)) are spurned by the tribe. Similarly when Jean murders a French trader in a squabble over a stash of gold and jewellery taken from the grave of another murdered trader, his attempts to escape with it are foiled by Sebiopepe, who shoots him in the leg with an arrow.

FIGURE 4.1 History hesitates, before it is washed away as by the tides of time, in Como Era Gostoso o Meu Francê s/How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman (Nelson Pereira dos Santos, 1971).

The final scenes see Jean sacrificed in a ritual for which he is prepared by Sebiopepe. Yet, with his last words Jean refuses to play his allotted role as sacrifice, and instead foretells the coming eradication of his Tupi hosts at the hands of the Europeans. The final credits are preceded by intertitles in blood-red lettering, containing a letter from the Governor General of Brazil, Mem de Sá , proudly detailing the (historical fact of the) extermination in battle of the Tupiniquim. Between Jean’s death and the intertitles, however, is one of the most distinctive endings in the history of cinema. Sebiopepe, gnawing with relish on Jean’s barbequed neck, breaks the fourth wall and stares directly at camera (see Figure 4.2). Her dark eyes fill the screen in close-up, framed by colourful ceremonial face paint. Then, the camera lingers over a tableau of the Tupinambá , paying homage to their existence – and genocide – in this historical moment. Finally, there is a shot of an empty beach. This location is integral to the film because it provides the pure optical and sound situation which Jean encounters at the start of the film and reappears here to bear testimony to the passing of the Tupi. In the letter that follows in the closing intertitles, just such a shoreline is described by the Governor General as littered with the dead Tupiniquim he has vanquished.

FIGURE 4.2 Having an old friend for dinner, in Como Era Gostoso o Meu Francê s/How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman (Nelson Pereira dos Santos, 1971).

Nelson Pereira dos Santos is one of Brazil’s most influential directors. He spent an influential two months in Paris in 1949, where he saw several neorealist films (Traverso 2007, 173). In the 1950s he made socially committed films like Rio, 40 graus/Rio, 40 degrees (Brazil, 1955) and became one of the key members of Cinema Novo movement with Vidas sêcas/Barren Lives (Brazil, 1963). But How Tasty stands out from these earlier films, both for its dark humour and its direct engagement with colonial history. There are various ways in which How Tasty, which appeared in the same year as the Uruguayan Eduardo Galeano’s Open Veins of South America (1971) and the Cuban Roberto Ferná ndez Retamar’s Caliban (1971) (both reconsidering Latin America’s history and its relationship to Europe), can be explored in relation to history. In this, the film’s original literary source is important to consider.

How Tasty is based on the diary of a German, Hans Staden, who claimed that he lived for a while as a captive of indigenous Americans, in 1556, awaiting his fate in the same manner as Jean. Unlike the protagonist of Dos Santos’s film, Staden, if his story has credibility, escaped to tell the tale. He frames his account, in fact, as one in which his Christian God intervenes to save him, describing the sickness which carries off many indigenous people as an act of God working towards his (Staden’s) salvation (tacitly indicating precisely how the horror of colonisation comes to be re-written as a supposedly civilising mission (1557, 69)).

Existing scholarship typically notes that How Tasty changes Staden’s identity from German to French to recognise that the French colonised the areas seen in the film (Stam 1997, 248–249) and to reflect the role of French culture in Brazil since the early Nineteenth Century, in spite of the initial, predominantly Portugese, colonisation (Sadlier 2003, 63). We can add that the Portugese and the French were fighting in this part of the world over trade in brazil wood (Staden 1557, ix). Thus, Frenchman Jean is pushed off the map in the first place due to his desire to profit by transforming nature (see Jason W. Moore, in Chapter 1). This historical reimagining relates directly to the moment of the film’s making. The film conflates the discovery of the Americas with the shifting political moment of the Cold War, and in particular the economic expansion favouring the global marketplace at the expense of national assets like the Amazon and its indigenous cultures (in the devastation wrought in the building of the Trans-Amazonian Highway (Sadlier 2003, 70–71)), in which Brazil under military rule was embroiled. As was the case with colonialism, it was evident that such Cold War developments were intended to enrich the few at the expense of the many. This understanding of the film is evident in the extensive existing literature, from which two indicative arguments can be highlighted (Xavier 1993; Peñ a 1995; Stam 1997; Young 2001; Sadlier 2003; Nagib 2007; Gordon 2009; Pé rez de Miles 2013).

Firstly, How Tasty is indebted to Tropicalismo, which impacts on its depiction of Brazilian history. The Tropicalist Movement of late 1960s Brazil reacted against the military government (1964 onwards), resurrecting aspects of the Cannibalist Movement of the 1920s, as typified by Oswald de Andrade’s ‘Manifesto Antropofago/Cannibalist Manifesto’ (1928). Andrade advocated cultural cannibalism, in which Brazilian identity is constructed through the consumption (cannibalist consumption, that is) of cultural aspects from inside and outside the nation. These aspects are then incorporated into the autonomous national culture. In How Tasty, cannibalism is used as a metaphor that turns on its head the previous labelling of native Brazilians as primitive and therefore justifiably exterminated by European colonisers. Indeed, Staden’s book was first published in Brazil in 1900, and was an influence on de Andrade, so it is not surprising that – coming later on in this legacy of rethinking the past – the film actively debunks the notion that Staden might have escaped due to his Tarzan-like ability to transcend the indigenous culture with the help of his Christian God (Staden 1557, x–xvi). Instead, as per the notion of cultural cannibalism, in How Tasty, Brazilian cannibals enslave and then eat the European, their bodies becoming intertwined just as their identities were in the founding of Brazil. This is one apparent meaning of the film’s final images, of Sebiopepe staring out at us as she eats Jean’s neck, inviting audiences in Brazil to consider their identity as Brazilians in the eating of ‘my’ (or ‘our’) little Frenchman. How Tasty, then, aims to engage the audience in its construction of a people, just as the Tropicalist Movement did (Peñ a 1995, 194; Stam 1997, 250; Nagib 2007, 68–69).

Secondly, How Tasty is typically interpreted at the convergence of broader Latin American reconsiderations of the continent’s history and the experience of Brazilians under the military regime. It critiques the recurrence of the same uneven power structures of colonisation under the Brazilian economic policy and military crackdown enacted by the US-backed dictatorship. Here, the film’s opening scene is much discussed for its deconstruction of colonial history formations, the myth-making they involve, and the casual loss of life on which they are built. This it does by juxtaposing ironically conflicting image and voiceover accounts of the arrival of Europeans under Nicolas Durand de Villegagnon, the leader of the French Protestant settlers of Guanabara Bay. The voiceover history we hear is at odds with the images we see – the film contrasting two different accounts of historical events (Sadlier 2003, 61), to humorously undercut the veracity of the historical record, both with regard to colonisation and the contemporary treatment of political opponents of the military regime (Stam 1997, 250; Sadlier 2003, 70–71; Nagib 2007, 71). Looking back from an era of fake news, what we recognise here is a playful engagement with cognitive dissonance in the enunciation of official history.

What can be added to this existing body of work on the film’s playful questioning of the veracity of history, then, is the role of the time-image in situating such a narrative within Atlantic history, itself part of a world cinematic history of intercultural encounters during colonial modernity which continues under globalisation.

Opsign, off the colonial map

The time-image appears early on in the film, and is used to express the moment of European encounter with the New World. The film’s ill-fated French protagonist, Jean, emerges from his attempted execution at the hands of his European comrades and wanders along the shore, accompanied by the sounds of native flutes, his movements impeded by the ball and chain attached to his ankle. In this moment, after being pushed off the colonial map, he meanders along alone in a pure optical and sound situation (opsign). After his effective banishment from the settler community, Jean encounters a situation to which he is unable to adequately react, and becomes instead a seer. Jean has lost his ability to perpetuate a linear historical narrative, lost the mastery of the world which accompanies Eurocentrism. Indeed, his banishment from the temporality of the European settlers is a punishment for fraternizing with the indigenous in the first place, for abhorring his place within the colonial order by attempting to enter into a more intertwined relationship with the naked native women. It is not a coincidence that, at this point, Jean is captured by the indigenous Americans.

In How Tasty, then, it is very explicitly the discovery of America – as a moment out of history – which is expressed through the use of a time-image. This also indicates, by turns, how European identity is grounded on the establishing of one dominant view of time at the expense of myriad others. In How Tasty, Jean’s life becomes intertwined with that of the Tupinambá in a manner that expresses Quijano’s view of modern intersubjectivities, albeit in an inverted parody as Jean is the Tupinambá ’s slave. In this time-image, Jean, the seer, is a witness whose sensory-motor interruption illustrates precisely the intertwined (albeit, unbalanced) mutuality of the experience of colonial modernity. However, Jean, wandering along the beach on his arrival, explores the same space which we know, from history, will soon be littered with dead Tupi. Thus this opsign encapsulates the existence of other times to that of European modernity, but simultaneously recognises the reality of the death of the other (and other times) that this encounter brings.

For Deleuze, the time-image has the ability to demonstrate the temporal division of the self, the realisation that time is a labyrinth in which ‘I is another’ replaces ‘Ego = Ego’ (Deleuze 1985, 129). How Tasty, by focusing on the time-image of the empty beach at the beginning and end, asserts the temporal division of the self-same that occurs in the intercultural colonial encounter so as to undermine the Cartesian certainty upheld by Eurocentric versions of history. The resurgence of the opsign of the deserted beach shows how only the eradication of the other (the dead, absent now, but historically littering the beach) can create the illusion of a singular self and a singular linear history. Prior to this, however, history hesitated. It was initially suspended in the opsign, when other possibilities still existed (Jean’s stay of execution, his life with the Tupi). In How Tasty the encounter between Jean and Sebiopepe demonstrates how the Eurocentric myth of the unassailable ego, based on the relegation of all others and their times to the primitive past (with the discovery of the Americas) is at odds with the reality of the intertwined histories of the Atlantic and the world system more broadly. It demonstrates the unstable, illusory position of the Western ego by juxtaposing the myth of its historical construction (in the initial colonial encounter) with the reality of its intertwined history of development along with the Americas.

Face to face with Sebiopepe

This time-image narrative, providing a shorthand way of thinking about five hundred years of colonial modernity, sets up the closing affection-image in which the ethical encounter with a lost past is offered. In the film’s most iconic moment, Sebiopepe eats Jean’s neck, the most sought-after part of the human by the Tupi. As she chews hungrily, her gaze directly to the camera challenges viewers to consider their relationship to this history and their role in the process by which the other becomes consumable material. At the time of the film’s release this image was primarily intended to address Brazilian spectators, engaging directly with the cannibalism of the Tropicalismo movement. It questions Brazilian identity in relation to the indigenous American, as opposed to the European coloniser. As Stam notes, How Tasty asks the viewer to consider whether the cannibalism of the Tupinambá is anything like as devastating as the economic ‘cannnibalism’ of colonisation (1997, 251). Yet, as the focus of recent scholarship on this scene with respect to the film’s portrayal of women indicates (Gordon 2009; Pé rez de Miles 2013), this image of Sebiopepe also offers an unusual viewing experience in contrast with the usual Eurocentrism, or rather, globalcentrism, of metropolitan audiences. Sebiopepe’s gaze suggests that the viewer takes the position of the powerless European, Jean, unable to assert a meaningful identity in the time-image. Instead they are confronted with alteriority: pre-modern, indigenous, woman, cannibal. All that Tarzan should be able to command is eating Tarzan, and with relish. The historical construction of the looking/looked-at relationship of Europe and the Americas over several centuries of Western art (of the clothed European man imposing his history upon the unclothed body of the indigenous American woman (Beardsell 2000, 14)) is not only inverted, but openly ridiculed. The import of this realisation is given an even stronger temporal dimension in the images that follow.

After Sebiopepe’s confronting gaze, the film offers a stylised moment of contemplation, a striking tableau in which the Tupi tribe stand still in ranks, and the camera pans across them, whilst loud chanting is heard on the soundtrack. This image is immediately followed by the end titles, which describe De Sá ’s massacre of the Tupi: ‘I fought on the sea, so that no Tupiniquim remained alive. Laid along the shore the dead covered almost a league.’ This ending provides an encounter with an indigenous American history which was first relegated to the past, then all but extinguished through massacre (in this specific instance by the Portugese), in order that the European ego could become the dominant form. What the viewer encounters, then, is not solely another identity, but – as per the potential of the time-image to enable a becoming-other via the connection to another (lost) past – an occluded history. This image provides a chance to encounter this lost past, intertwined as it is in Atlantic history.

The temporal dimension of this ethical encounter ties together the Deleuzian time-image with a Dusselian ethics, to illustrate how the construction of the self-same European ego is founded upon the denial of the intertwined histories of the world system. The affection-image here includes, literally, the ‘tableau vivant’ which Herzog discusses as indicative of its potential as ‘a threshold between worlds, a moment of forking time where various potential paths, actions and lines of flight intersect’ (2008, 68–69). It is so effective because it arrives at the culmination of a film in which the expected conventions of the encounter movie (in which a Tarzan-like coloniser subdues primitive natives) are inverted (Peñ a 1995, 193; Stam 1997, 249). Jean’s captivity does not provide the space for a masterful anthropological observation of the other, but rather situates him at a distance from his usual place within a narrative of teleological progress. As Nagib indicates, this is apparent in the way that the film is edited, so as to avoid privileging any one unified point of view throughout (2007, 71–72). For instance, early on Jean is observed from the perspective of a Tupi crouching in the jungle, making him the object of the gaze which controls that territory. This is precisely because, when falling off the colonial map, he encounters an opsign and lives his remaining months as a seer in a situation which he is not able to act to change. Instead, he can only witness the possibility of another history, which relativises the supposed centrality of his own.

Thus the affection-images, of Sebiopepe devouring Jean, and the tableau of the now exterminated tribe who held him captive, offer a glimpse of the other pathways through history denied coevalness by colonial modernity. Of course, Jean’s final prophecy at the moment of his execution does come true (‘my friends will come, to revenge me. No one of yours will remain upon this land’), as we are shown in the opsign of the now deserted beach which was, soon after Jean’s death, laid end-to-end with dead Tupi. Colonial action, decidedly, replaced the uncertainty of the seer, as the opsign was conquered by a narrative of progress offered by the Europeans’ civilising mission. Nevertheless, the reason for Jean’s arrival, as a sailor involved in the international wood trade, emphasises the coincidence of colonial modernity with the Anthropocene, and the correlation between European denials of coevalness (the destroying of other possible pathways through history) and the attendant practices of colonial enslavement and extermination in the North Atlantic trade circuit.

How Tasty, as well as negotiating what was a shifting economic and ecological historical moment, adds the ethical shift, which was occurring simultaneously. The affection-image that concludes the film asks us to consider, how were societies organised along lines of mutual endebtedness, prior to the racial contract? As David Graeber argues of the rise of capitalism in the Fifteenth Century (which he effectively aligns with the growth of the world system), along with Europe’s exploitation of Peruvian and Mexican precious metals, the conquistadores like Herná n Corté s were often deeply in debt and sought New World plunder as a result (2011, 307–325). Both the human toll of the murderous intent of colonial modernity and the ecological damage caused by extracting profit from nature are therefore inextricably intertwined in the origins of the Anthropocene. The arrival of Europeans in the Americas destroyed or irrevocably transformed societies in which people were connected in networks of mutual indebtedness, through the imposition of impersonal relationships of credit and interest, including those extended to would-be adventurers on foreign soil (332). This was, for Graeber, the result of capitalism’s rise along with colonisation (with colonial modernity, in fact), which rendered people strangers to one another (slaves, for example, become objects once removed from their embeddedness in societies of networked obligations (347)), and through the establishing of relations of credit/interest which encouraged slavery, genocide and ecological devastation in the service of transforming nature into profit (307–360). The North Atlantic trade circuit, after Graeber, can be understood as a ‘giant chain of debt obligations’ (347).

Jean’s time with the tribe, and his execution, indicate the very different sense of contractual reciprocity (including a mutuality to being in balance with the world) upon which pre-Columbian indigenous American societies were often ethically aligned (Graeber 2011, 136; Maffie 2013). For Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, a voice surprisingly unreferenced in existing discussions of the film, the cannibalism of the Tupinambá society is not to be understood as simply a vengeful measure providing a restorative function to society (i.e. one warrior is sacrificed to replace another). This is too simplistic. Rather, the physical incorporation of Jean in the ritual cannibalistic act can be understood, after Viveiros de Castro, as part of a wider social relationship of reciprocity amongst the Tupi – who were intertwined through their mutually defining relationship to war and the consumption of the flesh of their enemies (1986, 273–306).

Cannibalism for the Tupi had a creative function. It was only possible to reach the status of an adult man able to procreate by killing another in battle (279). Thus society could only reproduce because of the reciprocity, amongst tribes, of death – death of others, and at the hands of others (283). For this reason, being killed and eaten in such a ritual was not considered as unpleasant a form of death as was, for example, passing away peacefully at home (288–289). This was because, through warfare and cannibalism, ‘individual death’ served as ‘the fuel for social life’ (290). In a situation where ‘one is always and before all else the enemy of someone, and this is what defines the self’ (284), what is eaten in the ritual in which Jean is consumed (albeit, tellingly, he refuses to play the allotted role in it, foreshadowing the destruction that Europeans would bring to such reciprocally intertwined cultural norms) is the very position of being an enemy: of enmity (286). The role which the sacrificial victim should have played, and in which Jean was instructed (Sebiopepe taught him to say, at the point of death, ‘when I die my friends will come to revenge me’), suggests precisely the ongoing nature of this reciprocal intertwining. The victim is almost reassuring his captors that the vengeance which will follow (although it may mean the death of his captors) will nevertheless ensure the continuation of the Tupi.

Tellingly, this role is refused by Jean in favour of a different idea of revenge, one which validates instead the dominance of the European ego over the indigenous. His ‘friends’, as he predicts, in a proclamation in French which his captors cannot possibly understand, do indeed return to avenge him and, as Jean prophesises, to the point where no Tupi are left alive. Thus in the extermination of the Tupi, whose fate has disappeared from the empty beaches of the closing opsign, the Europeans establish the inequality of worth (one European life can be avenged by millions of indigenous lives) that is the racial contract, founding it directly upon the very eradication of this former, more reciprocal, ethics of cannibalist consumption.

What the racial contract also excludes from history, then, as How Tasty illustrates by situating its story in an opsign, is the possibility that society might be organised differently, ethically. This, whether in the specific manner of the Tupinambá which Viveiros de Castro outlines, or more broadly, as it was when, as Graeber argues, endebtedness was a way of organising mutually reinforcing community relationships, rather than of accruing personal wealth (2011, 207–208).3 Noticeably, due to this very different functioning of the society which Jean encounters in the opsign, in which a contrasting idea of contractual obligations exists to that of the racial contract (one in which Jean can live with the dead man’s wife as if she were his own), he is unable to know how to act so as to change his situation.

Finally, who does this affection-image address nowadays? At the time of the film’s production, the title of the film indicates with its emphasis on ‘my’ little Frenchman, the intended target of this gaze was Brazilians. The film attempts to make Brazilian audiences complicit in the consumption of an alternative origin that might inform national history, an intertwining of cultures, rather than a colonial imposition.4 Yet, even at the time of its release in Brazil, the film, which was subtitled because the dialogue is either in Tupi-Guarani (the country’s dominant language prior to the arrival of Europeans) or French, would have seemed to represent the old adage that the past is a ‘foreign country’, even to Brazilian audiences (Stam 1997, 250; Nagib 2007, 69). Nowadays, as we can no longer be so sure of the film’s contemporary audience, as it circulates globally on DVD and online, the viewer who is stared at, as they look in on the past, has been pushed off the colonial map. Like Jean, they must wander in the opsign, there to encounter a forgotten history of the Atlantic. They can but recognise, in Jean’s failed attempts to impose himself upon the tribe as their coloniser, the historically constructed nature of the normative position of the European ego which forms after 1492. Sebiopepe’s gaze, in fact, returns us to the origins of the Anthropocene, in the story of a European caught up in a historical moment in which the escalating tensions between indigenous tribes caused by the arrivals of the Europeans (and the competition to source brazil wood) led to the destruction of another society, another ethics.

Jean’s murder of a fellow Frenchman who makes his living by trading with the Tupinambá , over a small quantity of jewels and gold, suggests something of the greed for mineral wealth of the conquistadores. Yet this is to obscure the greater worth of the natural world being stolen by the Europeans. If we view How Tasty with an ‘ecological eye’ (see Chapter 3), for much of the film we are watching events set in a natural world, where trees are omnipresent, and a human environment constructed entirely from wood. Brazil wood, then, is the resource for which the Europeans will commit genocide. With the inter-tribal warfare that accompanied the European demand for brazil wood, the desire for gunpowder would grow amongst the Tupi tribes

into a sort of dependence as tensions between the indigenous American tribes – in this case the Tupiniquim and the Tupinambá – were exacerbated by the Europeans. This creation of a dependence economy, based upon the technological superiority of the Europeans, gave them the upper hand in commercial dealings with the tribespeople.

(Peñ a 1995, 195)

Thus it is in Jean’s mastery of cannon (which saves his life for a time, rather than Staden’s Christian God) that the equation between colonial modernity and the Anthropocene is most evident. Via the trading of gunpowder for brazil wood, How Tasty alludes to the reorganising of nature via what Moore calls the ‘Four Cheaps’ of the capitalist world ecology emerging after 1492 (see Chapter 1). Sebiopepe stares at us from out of the past, then, to request a remembrance of this lost past, a reminder of indigenous genocide, of ecological imperialism, but also of another possible (lost) past and its equally lost ethics.

Even the Rain

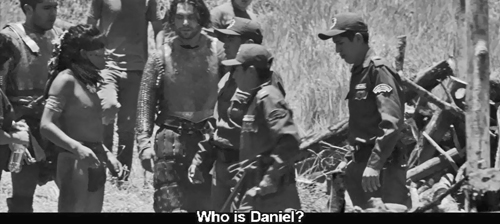

The second film provides a European perspective on the transnational history of the North Atlantic trade circuit. The encounter it offers is also with the inglorious European past of colonisation and (indigenous) American resistance to it, but with a focus on how this past is reflected in present-day struggles and how this can be realised from a European perspective (see Figure 4.3). Even the Rain (written and directed by Paul Laverty, from Scotland, and Icí ar Bollaí n, from Spain)5 is set during the water war which erupted due to the privatisation of water in Bolivia. It takes place during the riots in Cochabamba, in April 2000, between protestors (the Coalition in Defence of Water and Life) and the police and army (Laverty 2011, 7–8). The film is structured in mise-en-abyme. A Spanish film crew arrives in Bolivia to shoot a historical drama about the discovery of the Americas by Columbus in 1492, and gets caught up in the demonstrations and violence against the people. The crew learns first-hand about the events they become embroiled in, a process which also provides the viewer with access to knowledge about the actual historical events of the water war.

FIGURE 4.3 Colonial modernity – then as now, in Tambié n la lluvia/Even the Rain (Icí ar Bollaí n, 2010).

Once again, this story of colonial modernity, exploring the transnational history of the Atlantic, has a strong ecological dimension. Even the Rain examines how the latest phase in colonial modernity (that marked by neoliberal economic doctrine, during which multinational corporations exclude local populations from their own natural resources with the complicity of an elite political class) is intricately linked to the global environmental changes of the Anthropocene which commenced with Spanish desire for gold in 1492. In Bolivia, in line with the US-backed exposure of Latin American economies to global market forces during the latter stages of the Cold War, the New Economic Policy established in 1985 opened the door to the privatisation of state industries and natural resources, with the approval of the IMF and World Bank. Water war activist Oscar Olivera, a spokesman for the Coalition in Defence of Water and Life, argues that such neoliberal activities cost the Bolivian people more in terms of debt accrued than any of the previous dictatorships (2004, 12–15). The title of the film, then, alludes to the capping of private wells and banning of the use of water tanks to collect rain water, under laws passed by the government in support of the purchase of the nation’s water by a multinational consortium (Aguas del Tunari – renamed Aguas de Bolivia in the film – which included the US corporation Bechtel) (Olivera 2004, 58–60). Ordinary Bolivians found themselves facing exorbitant prices for water (even rainwater was not theirs by right) and took to the streets in protest. Ultimately the water war ended with the deal with Bechtel cancelled, a rare but now touchstone success in the resistance of organised people, united against neoliberalism and multinational corporations controlling their natural resources.

Whilst turn of the Twenty-First Century Bolivia is not a part of the North Atlantic trade circuit as it would be understood historically – albeit there was plenty of trade from the West coast of South America during the same period – even so the point the film makes, by having the filmmakers choose to set their recreation of the discovery in Bolivia due to the reduced costs it offers, is that the same exploitation occurs under globalisation as it did during former phases of colonial modernity. All that has changed is that arrival is by aeroplanes not caravels, the exploitation by multinationals not colonial states. The effect, however, remains the same: the struggle against inequality (increasingly, for survival, as the Earth’s natural resources grow scarcer), which defines existence for those excluded from colonial modernity, means that the attempted eradication (or reassertion in the present) of indigenous history is a battle that recurs down the centuries.

Even the Rain has already received considered critical attention, typically as a Spanish film, due to Bollaí n’s role as director. Its foregrounded reconsideration of colonial history leads many scholars to focus on transatlantic history, the potential transformation of Eurocentric viewpoints through encounters with different cultures under globalisation, ethics (as a result of the former), human rights, and ecology (Santaolalla 2012; Cilento 2012; Hageman 2013; Wheeler 2013; Hulme-Lippert 2015; Weiser 2014). Whilst conclusions drawn with respect to the film’s appeal to Spanish audiences are useful (e.g. Duncan Wheeler argues that ‘Bollaí n is trying to make Spanish audiences more aware of their trespasses in the past and present in order to inculcate an ethics of humility’ (2013, 251–252)), of particular relevance are two pieces which consider the film’s transnational appeal in ways which approach my own conclusions.

Firstly, Santaolalla, noting the film’s place amidst a longer heritage of Spanish films to consider Spain’s relationship with the Americas and its place in Bollaí n’s career trajectory (which sees similar concerns with intercultural exchanges under globalisation in films like Flores de otro mundo/Flowers from Another World (Spain, 1999)), discusses Even the Rain’s self-consciousness with respect of its ‘transatlantic imperialism’, and how it questions the ‘assumptions and positions of dominance’ of Costa and its other European protagonists (Santaolalla 2012, 211–212). Santaolalla argues that ‘with the fusion of Daniel and Costa, of white European and Latin American Indian perspectives, the film tries to appeal to transatlantic as well as to peninsular audiences. Very importantly, Tambié n la lluvia is not just neutrally transnational. Its transnationalism is inspired by its concerns with socially conscious, postcolonial sensibilities, and variations on perspective’ (219). Secondly, Andrew Hageman analyses the film alongside others that depict the water war, considering it a work of ‘ideological ecocriticism’ that offers ‘a glimpse of capital in desperation’ (2013, 75). The failure of events in the neo-colonial present to entirely match with those in the colonial past (the multinationals fail where the Conquistadores previously succeeded in their exploitative projects) indicates for Hageman something of the breaking point of global capitalism due to ‘catastrophic unemployment and ecological devastation’ (75).

Whilst sharing common ground with these predecessors, my interpretation is a little different. Although the film’s headline star is arguably Mexican Gael Garcí a Bernal, playing director Sebastí an, Even the Rain primarily focuses on the reconstruction of the film’s Spanish producer, Costa (Luis Tosar). He learns that the colonial history they are recreating for the film is one he himself is involved in perpetuating in the present. The film-within-a-film is intended to redress Eurocentric visions of world history. The film’s depiction of Columbus as a gold-obsessed, insatiably cruel soldier reconsiders a long history of cinematic depictions of this legendary European explorer.6 Moreover, the film crew is repeatedly shown recreating the exploitative power dynamics of colonialism and historical revisionism: for instance, by brushing over the casting of Quechua-speaking Andean Indians as Taí no Indians (from the Caribbean), which language to use, how much the language will have changed in the interim, and so on. In this way, the mise-en-abyme structure meditates openly upon the difficulty of depicting the initial moment of colonial contact as a historical drama (Laverty 2012). But it also enables the narrative arc of Costa’s reconstruction, key moments of which take place in time-images in which the film formally contrasts past and present in a crystalline manner.

Costa is initially depicted as the most cynical of all the film crew, happy to exploit the local populace in order to produce his film cheaply. He describes Bolivia as ‘full of starving Indians’, who are ‘all the same’. Ultimately, however, Costa decides to help the Bolivians in their struggle for the right to their own water, including Daniel (Juan Carlos Aduviri), an Andean indigenous American, and his family. Daniel is a leader of his people in the water war and is also chosen by the filmmakers to play Hatuey, a Taí no Indian leader in the film-within-a-film (historically, Hatuey led a rebellion against the Spanish and was burnt at the stake for it in 1512). As rioting erupts and the film crew flee for their safety, Costa returns to Cochabamba to use his privileged position as a Westerner to bring Belé n (Milena Soliz), Daniel’s daughter (who has been badly injured during the protests), through the roadblocks to medical assistance. As Isabel Santaolalla notes, in spite of the Judeo-Christian imagery and references interwoven throughout the film, Costa actually plays ‘a secular redemptive role’ (2012, 212–213). His reconstruction, then, speaks to ideas of liberation as a historical, rather than spiritual or transcendent, condition by its framing within the history of colonial modernity. In part for this reason, the film deliberately indicates that the reconstruction of Costa is likely a temporary one, as he returns to Spain at the film’s conclusion and indicates an unwillingness to return. Like so many films set in the Americas, a Western perspective is thus offered as an entrance point to the film for viewers from beyond the region where the film is set. Yet for Costa, like Frenchman Jean before him, what promises to be a potentially Tarzan-like entry point ultimately becomes that of one whose control over the land he encounters falters, in his realisation of the intertwined nature of his history with its. In this way, the assumed centrality of Eurocentric world history to his personal worldview is challenged.

The difference between this reading and the existing field can now be seen. Firstly, it places as much emphasis on Laverty’s influence as scriptwriter as it does on Bollaí n as director, because of the resonances between Laverty’s influences and this book’s Dusselian-inspired interpretation of a world of cinemas. Secondly, whilst – like Hageman – my cross-border analysis creates a distant view, unlike his broader rationale for grouping films around a contemporary event like the water war and a concern with ecology, here the taxonomising is propelled by the uncovering of how different films depict transnational history. This is also what distinguishes my focus on transatlantic history from Santaolalla’s perspective on the film within Spanish or Hispanic traditions. Indeed, whilst I also examine the film in terms of an ethics, I do not consider this to necessarily be a matter solely for Spanish audiences, as in Hageman’s position. More important than any of these differences, and where I commence my argument, is that this analysis focuses on the film’s deployment of a time-image in the construction of transnational history on film.

Crystal, Sixteenth Century colonial/Twenty-First Century neoliberal

The time-image that characterises Even the Rain is that of the crystal of time in which is glimpsed the coexistence of past and present. The film uses its crystalline structure to repeatedly draw parallels between the events in the historical past and those in the present. The virtual image of the history of the European conquest of the Americas and the resistance of the indigenous Americans (the film-within-the-film) comes to oscillate with the actual present-day protests of the water war so as to demonstrate their indiscernibility (Deleuze 1985, 66–121). Then, as now, this equation indicates, it was a struggle for wealth derived from the natural resources of the Americas in which different cultures, histories, and times become intertwined.

There are many examples of this in the film. Columbus’s meeting with Hatuey and other indigenous Americans (in which he announces the levying of a tax in gold on every indigenous ‘Indian’ over fourteen) is reflected in confrontations between Daniel’s community and corporation workers sent to cap their well. Similarly, the recreation of the Dominican Friar Antonio de Montesinos’s famous sermon of 1511 – in which he denounced the Spanish for their mistreatment of indigenous Americans and questioned, rhetorically, ‘Are these not men? Do they not have rational souls?’ (Pagden 1992, xxi) – is immediately mirrored in the present by Daniel’s speeches during the water war in which he stirs up his countrymen, saying, ‘What are they going to steal next? The vapour from our breath? The sweat from our brows? All they’ll get from me is piss!’ Again, the depiction of the Spanish conquistadores’ use of attack dogs to hunt down and kill the indigenous Americans in the Sixteenth Century finds its present-day mirror in the presence of dogs accompanying the Bolivian police and military as they run through the tear gas clouded streets to engage the water war protestors.

Of all such instances, the pivotal scene (its most direct image of time), occurs when shooting is disrupted by the arrival of the police in the present, to arrest Daniel on the set (see Figure 4.3). Here, the previous technique of cross-cutting between past and present events gives way to a more general confusion between virtual and actual layers of time, such that they become indiscernible. In the film-within-a-film, Daniel is playing Hatuey, the indigenous American who led a rebellion against the Spanish colonisers, and the scene in question is his public execution by immolation, along with twelve of his co-conspirators. His verbal defiance of the Spanish engenders solidarity and resistance amongst the assembled indigenous Americans, who chant his name as he dies. Then, as the shoot wraps, the Bolivian police arrive to arrest Daniel, who is still dressed as Hatuey. Their modern-day police van seems incongruous against the lush green setting (filmed in the Chapare jungle (Santaolalla 2012, 201)), in which signs of contemporary civilisation are absent from the film crew’s viewfinders.

Continuing this surreal effect, as Daniel/Hatuey is bundled into the back of the police van, the rest of the cast, also dressed as Sixteenth Century indigenous Americans, come to his rescue, tipping over the van so that he is released. As Costa and Sebastí an intervene to stop the scared police from shooting anyone, Daniel/Hatuey is aided in his escape by his friends. In this scene, more than any other, the conflation between events in past and present foregrounds how the ‘policing’ of the indigenous Americans by the Spanish conquistadores in the past is recreated by the actions of the anonymous police serving the elite (who profit from collaboration with the multinationals, in the present). The rebellion by the indigenous Americans is likewise literally repeated in the present, as the extras aid Daniel/Hatuey in his escape. In a nutshell, the crystal shows, the struggles of the Bolivians to retain access to their water is the same as that of the indigenous Americans to retain control of their land and natural resources over five hundred years ago.

Sebastí an and Costa are complicit in Daniel’s near-arrest, as it is they who convinced the Bolivian police to release him temporarily, to enable them to shoot the final scenes of their movie. This implication of the film crew in the exploitation of the indigenous Americans is crucial for the film’s conclusion, in which Costa finally develops empathy for the struggle of Daniel and his family. The crew’s realisation of their own actions as, effectively, slave traders in the Americas, is integral to the film’s contention that the history we glimpse in the present is the same global struggle which followed the discovery of the Americas: that between the multitude and the ‘counterrevolution on a global scale’ (Hardt and Negri 2000, 77) (see Introduction and Chapter 2).

It is not coincidental that a key figure in the execution scene in question is Bartolomé de Las Casas. Las Casas was a Dominican Friar who arrived in the Americas in 1503, was ordained a priest in 1510, but was initially involved in obtaining wealth from colonial oppression. He later went against the Catholic Church and began to argue against the devastation that the colonial project caused to the indigenous American tribes (Pagden 1992, xviii–xxii). Accordingly, he remains a historical precursor to contemporary liberation theology and philosophy (Dussel 1996, xviii–xxii). The film references events described in Las Casas’s Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies (1542), which details his experiences during the initial colonial encounters. This work provides a stark account of the genocide (the slaughter, torture, slavery and disease) wrought on the indigenous Americans by the Spanish. The film dramatises and condenses certain of the events detailed in Las Casas’s account, including the dramatic scene of the thirteen sacrificial pyres to represent Jesus and his twelve apostles (which precedes the bungled arrest of Daniel/Hatuey), Hatuey’s last words (that he would prefer to go to hell than reside in heaven with the Christians) and the use of attack dogs to kill indigenous Americans (Las Casas 1552, 15–17, 28). Indeed, in the film-within-a-film, the character Las Casas (Carlos Santos) appears prominently at the execution of Hatuey, in the film’s pivotal time-image.

The appearance of Las Casas in the film can be traced to various origins: he features in the first chapter of Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States (1980), the original inspiration for the film, and Laverty’s personal background included formative years spent in Latin America during the 1980s, during which he encountered trades unionists and human rights activists influenced by the theology of liberation (whose courage to act on their conscience he found in the outspoken critics of colonialism amongst the Dominican priests, like Las Casas (Laverty 2012)). Key to understanding the ethics of the concluding affection-image, however, is that the decolonial critique of Las Casas was influential in the formulation of both Gustavo Gutié rrez’s theology of liberation in the late Twentieth Century, and, as a result, Dussel’s development of his philosophy of liberation. For Dussel, the ‘first head-on critic of modernity’ (2006, 16) Las Casas refused to deny the indigenous Americans their status as equals, refused to deny their coevalness (1992, 69–72). As a figure to appear in the film, then, Las Casas is indicative of the centuries of intertwined histories (domination/revolution) of colonial modernity, which are caught up in the crystal of time in Even the Rain.

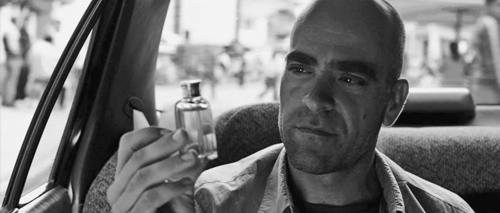

Face to face with an anonymous taxi driver

The encounter with the past offered in the final stages of Even the Rain is more indirectly rendered than in How Tasty. The finale of Even the Rain takes place in a taxi, and shows two gazes that do not meet. Moreover, the gaze which breaks the fourth wall is, very deliberately, heavily mediated. As a result it confronts the spectator rather obliquely. By rendering the frontal gaze in this way, Even the Rain dramatises the unequal nature of the conflict, domination/revolution, the intertwining of peoples it entails, the global inequality it fosters, and – most especially – the lack of recognition it provides for the many histories which it excludes from the official record. Unlike the confrontational optimism of How Tasty, confident in its assertion that there is another history, another way into the labyrinth of time which can be signalled by the presence of a direct gaze to camera in the affection-image, in this case the access to this past is given as, literally, a glimpse. Just a glance, in fact, which the European, Costa, misses in his preoccupation with his own reconstruction. Thus Even the Rain is scrupulously honest in its depiction of this particular perspective on the legacy of the North Atlantic trade circuit. It illuminates that there is a forgotten history to be uncovered, but emphasises that it is one which speaks to the unthinking of Eurocentrism precisely for Eurocentrics. Some more detail is needed at this point.

The final scene in the taxi directly follows a scene in a warehouse, in which one of the film’s many crystals of time is repeated so as to demonstrate the completed reconstruction of Costa and his previously Eurocentric understanding of history. The first such scene takes place around thirty minutes into the film, when Costa speaks to Daniel in the warehouse. There, the filmmakers have constructed a replica of an early Sixteenth Century Spanish caravel, of the type Columbus sailed in. The framing of Costa in dialogue with Daniel conflates his initial attitude with that of the Eurocentric legacy of colonisation. Costa is trying to persuade Daniel to withdraw from his role as a leader of protestors in the water war until the film is over. He is interrupted by a phone call from one of the film’s backers. The camera tracks Daniel moving through the props, which include the guns, knives and cannons of the colonisation, as Costa, speaking in English (which he assumes that Daniel cannot understand), boasts about how cheaply he can make his film in Bolivia. ‘It’s fucking great [… ] two fucking dollars a day, they feel like kings. You can throw in some water pumps, some old trucks when you’re done and hey presto, two hundred fucking extras!’ Daniel understands English, having spent time working in the US, and angrily confronts Costa. As he leaves with Belé n, Costa, crestfallen at being caught out, is framed from Belé n’s point of view, with the caravel and a large crucifix behind him. As he then turns to leave, the film cuts twice in quick succession, firstly to a shot of the entire warehouse of props, the caravel taking up the middle ground, and then again to the recreated scenes of the indigenous Americans panning for gold – precisely the two hundred extras of which Costa boasted. In this way, through the use of cinematography, mise-en-scè ne and editing, Costa’s exploitative position on the Bolivian workers, and indeed the reality of cross-border labour in the present day, is positioned as part of a five-hundred-year-old legacy. Costa in the present is effectively equated with the conquistadores in the past.

This scene is then replayed just before the film’s final moments, set in the taxi. Costa and Daniel repeat their face to face encounter in the same warehouse, which is now abandoned except for the remains of the model Spanish caravel (see Figure 4.4). In this instance, Costa and Daniel share genuine emotion and friendship, and Costa’s conversion from his previous Eurocentric position, due to his interaction with Daniel and his family, seems complete. They exchange parting gifts: Costa a print-out of a headline from the Spanish newspaper El Correo, which includes a photo of Daniel, declaring the victory of the Bolivian people in the water war, and Daniel, a small wooden box. As they do so, Costa is framed with the caravel behind him, once again conflating him with the history of colonisation and modernity, but this time in tatters.

FIGURE 4.4 The ruins of Costa’s (unthinking) Eurocentrism, in Tambié n la lluvia/Even the Rain (Icí ar Bollaí n, 2010).

When Costa first spoke to Daniel in this scene, he was surrounded by the armaments of colonisation, which Daniel fingered gingerly, and flanked by the imposing Spanish caravel. The second time, however, this informing milieu is in ruin. As a time-image it precisely illustrates that Costa’s informing virtual history of colonial triumph (which the film earlier equated with Costa’s mistreatment of the Bolivian actors in the film) has been ‘ruined’ by his acknowledgement of his connection to Daniel, his family, and his rights. Costa now has to rebuild his informing history (that which had previously framed his arrogance towards Daniel, as seen in the image of Costa framed by caravel and crucifix), due to the loss of his Cartesian self-same self. This loss, noticeably, he has experienced through his Dusselian ethical encounter with the intertwined histories of European self and indigenous American other. Put simply, Costa can no longer act in a manner as though he is informed by an unproblematic acceptance of his colonial past. Having entered into an ethical relationship with Daniel, that particular labyrinthine pathway through time, alone, cannot inform his actions. The mise-en-scè ne shows that his previously informing past is now in tatters, due to the present-day realisation of the ongoing historical reality of European entanglement with indigeneity.

Daniel, for his part, has been provided with a positive, fictional, virtual past by the arrival of the film crew (his is also a labyrinthine powers of the false), when his Hatuey side escaped from the Bolivian authorities in the present and replayed the past differently. After all, this is just as the Bolivians did when they won the water war, defeating the multinationals being a standout success in the centuries of colonial modernity. Daniel’s words to Costa evoke the history of the colonial struggle of modernity as one of constant battle. He states that it: ‘Always costs us dear, every time. It’s never easy. I wish there was another way.’ When Costa then asks him what he will do next, Daniel responds: ‘Survive, like always. What we do best.’

Yet the seeming stoicism of these words does not do justice to how the film portrays the refusal on the part of the Bolivians to accept the role or history of a colonised, subjected people. The sentiment, visually, seems more akin to Dussel’s point, that the indigenous of the Americas were never conquered, and revolt against colonial modernity (Hardt and Negri’s perpetual revolution/counterrevolution) is ongoing precisely due to the structural inequality inbuilt into the system (2003a, 225). After all, in both film-within-a-film (where the extras refuse to recreate actual moments from their history of colonisation, and where Daniel escapes from the authorities in a refusal of the fate of Hatuey who died at the stake) and the film itself, a postcolonial powers of the false is activated in the present so as to rewrite a Eurocentric history of domination as, instead, one of perpetual struggle and intertwining of cultures. Thus, from the time-image, another history is seen to emanate, one in which Daniel/Hatuey survives the past in order to lead his people to victory in the water war. This newly emerging other history impacts directly upon Costa’s liberation. When Belé n is injured during the protests, her mother, Teresa’s (Leó nidas Chiri) actions in seeking out Costa’s assistance provide the present-day counterpart to the refusal on the part of the Indians acting in the film to repeat past events (such as sacrificing their infants by drowning). Costa, then, becomes an integral part of this new history of liberation, in which the colonial forces of neoliberal multinationals are overthrown by protest movements which have been described, again echoing Hardt and Negri, as a ‘flexible organizational network’ able to mobilise the various people who constitute ‘multitude’, in opposition to neoliberalism (Linera 2004, 74).

This brings us back to the scene in the taxi, following immediately after the touching scene in the now deserted warehouse. As Costa leaves for the airport in the taxi, he opens the gift given to him by Daniel. Inside the box is a small vial of water. Significantly it is about the same size as the containers which the conquistadores (in the film-within-a-film) force the indigenous Americans to fill with a quota of gold on pain of dismemberment. Previously, during their several interactions, Costa has only ever discussed money with Daniel. Daniel’s gift is chosen to teach Costa that the war for water is the same war that has been waged since 1492, only with gold replaced by an arguably more significant natural resource. When Costa sees the vial of water, he speaks a Quechua word for the first time: ‘yaku’ (water). This is significant because, previously, whilst certain members of the crew were keen to learn Quechua, Costa held himself back from engagement with the indigenous culture he was exploiting.

FIGURE 4.5 Fleetingly realising that another(’s) history exists, in Tambié n la lluvia/Even the Rain (Icí ar Bollaí n, 2010).

Along with the perhaps more trite interpretation that offers itself (that Costa has learned that some things are more valuable than money), Daniel’s gift indicates the significance of water for Bolivians, which is held to be a sacred right, rather than a commodity, in a tradition related to community preservation that stretches back to the Incas (Laverty 2011, 10–11 (see Figure 4.5)). Here, the evocation of the former levy of gold imposed by the conquistadores, in an equation with the small vial of water, illustrates the greater spiritual dimension of colonisation and the devaluing of indigenous American culture and tradition by Western thinking. As Costa speaks the film’s final word in Quechua, the anonymous taxi driver looks into his mirror, and we see his eyes in close-up as he reacts to Costa’s use of Quechua (see Figure 4.6). In this moment Costa, by speaking a Quechua word which has a meaning that he has come to understand to mean life (Daniel’s gift is to thank Costa for saving Belé n), has an opportunity to enter into an ethical relationship with the other. However, Costa does not spot this opportunity. He is thinking about what has happened to him and looks out of the window as the taxi drives through the streets of Cochabamba. This returns Costa to his initial position, at the very start of the film, of newly arrived (colonial) observer of Bolivian life through an automobile window, the imperialist tourist-like gaze, isolated from those upon which it lands. The potential of this affection-image to offer an entrance to another understanding of the past, one of interaction between cultures, is thus lost.

Noticeably, the gaze that regards Costa, and briefly also the viewer, is mediated through a mirror, playfully foregrounding once again the virtual/actual temporal relationship with which the film has been toying in its exploration of colonial modernity. The look of the taxi driver comes from the virtual history of the colonial encounter. Costa, however, fails to notice or return the gaze. Ultimately, then, Even the Rain’s European perspective on this transnational history is – as stated above – an honest one. Despite focusing on Costa’s reconstruction, the film foregrounds the limitations of European involvement in Bolivia, noting that only because of Costa’s privileged position can he assist Daniel’s family. After all, he does not play any active role in the Bolivians’ struggle during the water war, and departs soon afterwards. Although Costa, perhaps like the European film viewer, can temporarily inhabit the crystal of time, his actions ultimately maintain the difference between European and Bolivian worlds. As Olivera notes, the water war was won, but this was only one small step in an ongoing struggle against neoliberalism in Bolivia. A giant victory against the odds, it is true, but all that was won was the maintenance of a basic natural resource (2004, 46). Costa’s departure shows, ultimately, that whilst there may have been some unthinking Eurocentrism, some reconsideration of the national, colonial past, for many Europeans this is a past conceived of as having taken place hundreds of years ago. The actions of the multinationals, now, can therefore appear rather disconnected from any sense of ongoing responsibility. Costa does learn that it is wrong to oppress others (as it was in colonial history, so too is it now under globalisation) or turn his face away when others need help – hence his return during the rioting. Even so, the film emphasises, his ethical encounter is limited to a (temporary) unthinking of his own Eurocentrism.

FIGURE 4.6 Ephemeral ethical encounter, in Tambié n la lluvia/Even the Rain (Icí ar Bollaí n, 2010).

In Even the Rain as in How Tasty, an attempt is made to indicate how the entangled histories of white (European) and indigenous cultures from 1492 onwards illustrate a lost past, so often forgotten by Eurocentric history. It is for Europeans, and their diaspora, that these films provide an encounter with the lost past which was, and is, intertwined with theirs in colonial modernity. The history of the exploitation of the Global South, which necessitates such entwining, and upon which the exploitation of which the Global North depends, is ‘unseen’ by the Global North due to its Eurocentric view of history.