A world of cinemas, incorporating films from all around the globe, is trying to tell us a story: several stories in fact. These stories belong to the world history which we all share. I refer to them here as transnational histories in that they are histories which pre-exist, or impact across, national borders, within this much larger, encompassing, world history.

What is remarkable is that these transnational histories are being examined by filmmakers from disparate locations worldwide in similar ways aesthetically. In Chapters 3–6, I outline how the stories of the following transnational histories are being told across a world of cinemas: the planetary history of the Earth (Loong Boonmee raleuk chat/Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (Thailand/UK/France/Germany/Spain/Netherlands, 2010) and Nostalgia de la luz/Nostalgia for the Light (Chile/Spain/France/Germany/USA, 2010)); the North Atlantic trade circuit (Como Era Gostoso o Meu Francê s/How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman (Brazil, 1971), and También la lluvia/Even the Rain (Spain/Mexico/France, 2010)); the Cold War (The Act of Killing (Denmark/Norway/UK, 2012) and Al pie del á rbol blanco/At the Foot of the White Tree (Uruguay, 2007)); and neoliberal globalisation (Carancho/Vulture (Argentina/Chile/France/South Korea, 2010) and Chinjeolhan geumjassi/Lady Vengeance (South Korea, 2005)). Before I turn to these examples, however, I will outline the book’s argument in this Introduction, unpacking it in full in the chapters which follow.

Encountering lost pasts

Firstly, we need to consider how we watch. To illuminate this pattern, trend, or certain tendency towards the telling of the story of transnational histories across a world of cinemas, requires that we recalibrate how we group together films (how we categorise) when we analyse them. It necessitates a refocusing of our viewfinder away from individual nations, as is already the case with the transnational turn in Film Studies generally, but – as has yet to be the case – towards a broader conception of world history as the ground for such a hermeneutics. In this book, the worldview offered by influential Latin American philosopher Enrique Dussel (known for his work on ethics in relation to liberation philosophy; see Chapter 1), which draws upon world systems analysis, enables a greater understanding of how what is depicted on screen does not relate solely to a national-historical ground, but also to the transnational history (or histories), which traverse world history.

With focus thus newly racked we can also see how cinematic depictions of the past – specifically lost pasts (disappeared, censored, forgotten, eradicated) – are aesthetically structured like ethical encounters with others. A world of cinemas thus offers us encounters with lost pasts. In this way, what is revealed is not only that there are myriad other pasts submerged within world history (even if we may not feel they directly inform our present), but so too that the ethics required of us by recognition of these pasts is one which involves us all, as peoples of the world.

These encounters are most visible when staged between characters onscreen, as they are in many of the films discussed. But as importantly, they also offer an encounter to the viewer. This is not a cinematic encounter with an other necessarily (another human or even another species for example), as the status of self and other will depend on who is watching. Rather, it is an encounter which offers the realisation that such a person, or even species, has a history (in fact, a lost past) which belongs to the broader world history we all inhabit. What is important is that this realisation provides the viewer with the chance to hesitate, and potentially to recognise the relative centrality of their own place in world history.

For some, typically those closer to the location of filming, this may not be a world changing revelation. This, even if the process of considering the still-smouldering ‘embers’ of a lost past may be most crucial in such places (Sanjiné s 2013). But for others, even if viewing from much further afield, this will create hesitation with respect to formerly held beliefs as to the place, perhaps even primacy, of the viewer (or their culture) within world history. In fact, this potential to hesitate with respect to what is believed to be normal regarding the past is open to all, and it is debateable whether it is felt more strongly by those nearer to, or further from, the film.

Acknowledging the existence of such lost pasts – histories now recalled only as memories, times, fabulous beings, songs, myths, fables – renders histories previously thought to inform the present, universally, now only one amongst many: whether human or nonhuman. For this reason, the transnational histories on film examined in this book are not understood to offer an ethical encounter with an other, but with another (lost) past. The reappearance on screen of these lost pasts challenges the hegemonic nature of Eurocentric views of history (whether this is a revelation to the viewer or not), and accordingly may make some feel uncomfortable in their own skin.

We may or may not be able to know these pasts. Indeed, for many viewers the experience may be, precisely, the realisation of an inability to know another, or another’s past. Yet for others, such films offer a chance to hesitate with respect to what is known, via an encounter with a lost past.1 A world of cinemas thus offers a hesitant ethics which seeks to address the historical foundations of global structural inequality – the perpetuation of capitalism via a deliberately unequal distribution of wealth, worldwide, which has persisted since at least 1492. Structural inequality is not solely the norm under neoliberal globalisation (today, even in the USA, the world’s richest nation, there are 41 million people living in poverty, 9 million without cash income (Pilkington 2017)), but is inherent to a several hundred-year-old process which I discuss here, after Dussel and others, as colonial modernity (Coronil 2000, 369–370). As Chapters 3–6 illustrate via world cinemas, whilst, since the 1990s, the fall of the Soviet Union signalled freer trade across borders (and thus the period is pivotal in certain definitions of the emergence of globalisation), even so, the roots of the contemporary economic situation lie in the Cold War’s ‘Pax Americana’ (a conflict which itself grew out of the last decades of the era of Western imperialism), a regress thereby taking this particular story of colonial inequality back at least as far as 1492 and the European discovery (for Dussel, ‘invention’ (1992b)) of the Americas. Thus, world history after this date, for Latin American philosophers like Dussel, is one of the intertwined nature of modernity with its propellant, coloniality – and this continues even today, under neoliberal globalisation. As a world of cinemas also indicates, the exploitation of the globe by the latter force, coloniality, is that from which the gains of modernity proceed, both historically and now.

For this reason, I claim that cinema is against doublethink. Doublethink is the Orwellian reduction of the myriad pasts of the world history to a singular narrative (such as that of the Hegelian view of history, discussed below) which retroactively bolsters the seeming legitimacy of the current world order, obscuring in the process the inequality via which it is fostered (the other lost pasts of world history).

The question is, why is this important?

The non-fascist life: Introduction to, or conclusion of?

George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) famously imagines a bleak dystopian world in which the past is perpetually re-written in the present, so as to maintain authoritarian one-party rule at the expense of the lives and happiness of society’s inhabitants. One of the most important literary works of the Twentieth Century, in the Twenty-first it has become an extremely pertinent text for Western society. Sales spikes occurred after the Edward Snowden leak of 2013 (revelations concerning the US National Security Agency’s secretive monitoring of its own populace) and the 2016 US presidential election, specifically after the appearance of the term ‘alternative facts’ in the wake of the presidential inauguration (Stelter and Pallotta 2017).

In the conclusion of Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell outlines what doublethink means with respect to how the past is remembered, or, to how the story of history is told. As Winston Smith is tortured by party member O’Brien, he is confronted with a photograph which depicts an image from the past. The party now proclaims that the past never happened in the way the image evidently portrays. O’Brien incinerates the photograph and the following conversation ensues:

‘Ashes,’ he said. ‘Not even identifiable ashes. Dust. It does not exist. It never existed.’

‘But it did exist! It does exist! It exists in memory. I remember it. You remember it.’

‘I do not remember it,’ said O’Brien.

Winston’s heart sank. That was doublethink.

(Orwell 1949, 283)

Doublethink, then, concerns the ability to convince ourselves that two contradictory statements are, simultaneously, true (40–41). It is how authoritarian regimes censor the past, leaving only one official story of history left, in spite of peoples’ lived experiences to the contrary. The populace must adhere to the official story on pain of torture and death.

Examples of doublethink have been prevalent throughout recent colonial history. Remaining in a literary vein, Gabriel Garcí a Má rquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967) famously evokes the United Fruit Company’s massacre of striking workers in Colombia in the 1920s (and its disappearance from history) as a stand in for a longer, often undocumented, history of such violence (298–319). The only surviving witness of the murders and the disappearance of all evidence of it is told: ‘There haven’t been any dead here [… ] Since the time of your uncle, the colonel, nothing has happened in Macondo’ (313–314). The soldiers wiping out all remaining trace of organised political opposition repeat the same doublethink mantra: ‘Nothing has happened in Macondo, nothing has ever happened and nothing ever will happen. This is a happy town’ (316).

In fact, doublethink has never been far away, and was especially apparent during the Cold War. It was a feature of Eastern European regimes, as per Orwell’s fear for a future Britain in his novel, and spread throughout many parts of the so-called third world. Unsurprisingly, then, in the wake of the dictatorship in Argentina, for example, the film La historia oficial/The Official Story (1985) made precisely the point I am making here. Now, increasingly, doublethink is an everyday reality in Western liberal democracies. Whilst our eyes tell us that the US president’s inauguration in 2017 was sparsely attended, the press and public are officially informed that it was the most well-attended inauguration ever. This is, precisely, the bracketing off of what we know to be true, in favour of an ‘alternative fact’ which we are told we must believe. This is what the term ‘post-truth’ often refers to, the prevalence of doublethink.

Framing this book is the spectre of this Orwellianism, which is explored via an analysis of how encounters with lost pasts create hesitation over the sense of our place within world history. This is because of a very specific cinematic feature of all of the films discussed, the similarities between the functioning of what Gilles Deleuze called the ‘time-image’ (1985) in what I am claiming is a hesitant cinematic ethics, and doublethink.

So, what is the time-image?

Deleuze’s taxonomy of movement-images and time-images is now an integral part of the mainstream in Film Studies.2 Deleuze’s time-image categories (see Chapter 2) depict the temporal existence of the world directly (in the sense of, without subordination to movement through time, which produces a less direct, or spatialized form of time, or ‘movement-image’). In Deleuze’s time-image, especially in the concept of the crystal of time (in which we are able to glimpse the infinitely divisible nature of time, its perpetual splitting into a present that passes, and a past that is preserved), there is hesitation over the veracity of history. The crystal of time, by definition, contains the potential to offer an alternative view of the past, one which contrasts with that which we believe informs the present (see Chapter 2). I state ‘by definition’ because if time is forever splitting in this way, then what is stored in the (virtual) past is the infinite possibility of alternative histories to that of the one informing the (actual) present. Thus the crystal is a potentially destabilizing, deterritorializing, ungrounding force within history. Its purpose is to make us hesitate about the veracity of the present, by reminding us of alternative (or, lost) pasts.

Until recently this was thought to be a celebratory revelation, due to the challenge that the time-image poses to established histories. After all, the term ‘alternative’ has only very recently taken on the negative connotations it now has in the so-called ‘post-truth’ era. A brief example can show why the time-image’s power to unground history was celebrated until now.

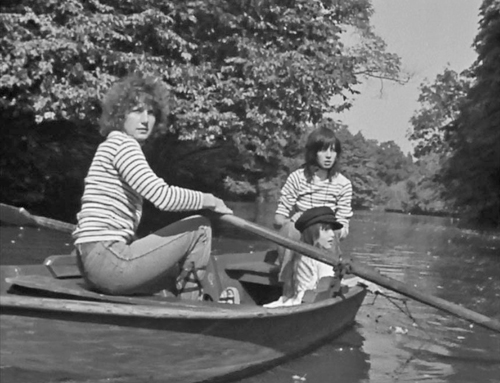

In Jacques Rivette’s Cé line et Julie vont en bateau/Celine and Julie Go Boating (France, 1974), history is revealed to be a patriarchal conspiracy that excludes women. This history is challenged by the two eponymous heroines, a magician, Cé line (Juliet Berto) and a librarian, Julie (Dominique Labourier). They save a little girl from being murdered by returning to the past (see Figure 0.1). This past, dubbed the ‘House of Fiction’, is figured as both symbolic and societal, as well as informing of the personal histories of the heroines. It is, then, the virtual store of the past as totality, from which the official story of history emanates, but within which is also contained its alternatives – its other (lost) pasts – and, accordingly, its potential for change. Their travel to this past is undertaken via magic sweeties (candies) which enable an Alice in Wonderland style entrance into, or rather, passing through of, the crystal of time. The perpetually splitting nature of time is revealed to them in this way, such that they realise how the telling of this story of history can change: as they state succinctly, once upon a time can become ‘twice upon a time’. To figure this out, however, is a work of historical detection on the part of the heroines, who must first of all hesitate with respect to the veracity of the truth of the story of history which they have known up to this point.

FIGURE 0.1 Saving the girl revives the lost past ‘murdered’ by patriarchy, in Cé line et Julie vont en bateau/Celine and Julie Go Boating (Jacques Rivette, 1974).

Ultimately, Cé line and Julie are able to save the girl from a ‘murder’ symbolic of woman’s entrapment in patriarchy from childhood. They thus enable the girl, and, by extension, themselves, to escape this fate and imagine a different future. Emerging during the second wave of feminism in the West, then, Cé line and Julie explores the possibility that an alternative history can be offered to that of patriarchy. Hesitation, the time-image shows, is what happens in a moment where the veracity of history comes into question, allowing new futures to emerge.3

What is very apparent from this example, however, is that the operation involved, the positing of an alternative past which can inform the present, is not substantially different from that of doublethink. Albeit, we might argue that whilst doublethink attempts to obscure the reality of the past, the time-image actually attempts the opposite: the revelation of pasts that are obscured. Put another way, doublethink reduces history to one, the party line, whereas the time-image asks us to contemplate that history is multiple, labyrinthine, and potentially falsifying of the present (as opposed to fake). Even so, for those on opposing sides of this operation, there may well be an equal sense that what is being revealed or obscured (the effectively falsifying nature of the operation) is done with the best of intentions. Or at least, we can give actors at either end of the political spectrum the benefit of the doubt, for argument’s sake. So, is the time-image any different, let alone any better, than doublethink?

Ultimately, the only difference between doublethink and the time-image is one of political intent. In an internet era which sees political discourse influenced by fake news in a deliberate attempt to create cognitive dissonance (Pynchon 2003, x) in the minds of voters (if we are unable to tell which of the ‘alternative facts’ presented is true, then how can we know who to vote for?), creating hesitation is now a political strategy used most effectively by the right to foster disengagement with the political process. Hence, it is now more important than ever to clarify how the time-image’s political potential remains useful to our understanding of how the story of world history is told cinematically. To what extent can we still claim that the hesitation fostered by the time-image is ethical, in the face of doublethink, alternative facts, and fake news?

This discussion, of course, has some pedigree already (Corner 2017). Long before President Donald Trump’s election led to claims that the right have stolen the crucial tools of philosophy in their surrounding of the truth with fake news (Williams 2017), in the wake of 9/11 and the resulting ‘War on Terror’, Bruno Latour had already noted the political right’s capacity to hijack critical theory’s tendency to debunk, deconstruct, unmask, and otherwise falsify accepted truths with alternative views of reality. Latour emphasised, especially, that purposefully maintaining a lack of scientific certainty (spreading doubt, effectively), in spite of the facts to the contrary, had already been established as a right wing tactic to deny climate change (Latour 2004, 226–227; Klein 2017, 67). Herein, then, lies the distinction between the importance of hesitation in the time-image, and in the cognitive dissonance fostered by fake news. For Latour, ‘confidence in ideological arguments posturing as matters of fact—as we have learned to combat so efficiently in the past’ (combatted, we can say, for example, via the time-image as challenge to patriarchal history in Cé line et Julie) is now replaced by ‘distrust of good matters of fact disguised as bad ideological biases’ (as propagated by fake news denials of climate change) (227).

Yet, when Latour identifies the extinguishing of the lights of the Enlightenment, which had previously debunked so many older beliefs, by this ‘same debunking impetus’ (232) he is really, perhaps unwittingly, indicating the problem inherent to the news/fake news debate – namely, that the history of colonial modernity (which includes the typically lauded Enlightenment) builds its legitimacy upon doublethink.

So, what is colonial modernity?

Colonial modernity is a term used throughout this book to describe the history of global capital since the growth of Europe and the West (from the late Fifteenth Century onwards) to its present position of world dominance. It describes the emergence of modernity after 1492 on the back of colonial genocide, enslavement, torture, theft on an imperial scale, and the devastation caused by environmental exploitation for profit: all to provide the West with the wealth which accumulates from the managerial control of the resources and trade of the world system (Dussel 2003a, 62). As Walter Mignolo, indebted to Dussel, summarises, ‘there is no modernity without coloniality’ (2000, xii–xiii and 43), they being ‘two sides of the same coin’ (50).4 The term ‘coloniality’, in fact, has a very specific meaning. It is drawn from Aní bal Quijano’s argument that, distinct from colonialism as a historical category, the structure of domination which emerges with the rise to global dominance of Europe after the conquest of the Americas illuminates the ‘coloniality of power’ (2008, 101). ‘Coloniality’ includes colonialism’s ‘social classification of the world’s population around the idea of race’ within a global capitalist structure for controlling labour (Quijano 2008, 181), which remains ongoing under globalisation.5

It is for this reason that the eradicated histories which doublethink suppresses perpetually threaten to derail it, just as the ungrounding force of the time-image indicates the unstable nature of the Eurocentric view of world history – its instability being due to the subsisting histories which it has banished to the past. As Garcí a Má rquez so succinctly notes, after all, empires have always hidden their crimes, justifying them in the name of the advances they supposedly bring.

For Western thought, it is the emergence of decolonial and postcolonial thinking, around the world, in particular after World War Two, which disturbs this orthodoxy.6 Accordingly, the ungrounding of the history of colonial modernity via the time-image took place in the West at a moment when the left sought to uncover this great deception. It is no coincidence that May 1968, and second wave feminism, occurred as the global power of Europe’s imperial nations waned, nor that Deleuze (perhaps erroneously), considers the time-image a post-war European invention in part for this reason. Yet, although the above subheading concerning a non-fascist life references Michel Foucault’s preface to Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus (1972), a book which Foucault believed provided an introduction to a life without fascism, looking back from the present under neoliberalism, this hope of a non-fascist life now seems, at best, optimistic.

Simultaneous to the intellectual development of the European left in the 1960s and 1970s, the CIA also realised the potential of French theory to boost the right’s political project of deepening wealth inequality globally (Rockhill 2017). The attack on the young, which was a feature of the Cold War in many parts of the world, saw the right eradicating the potential for political opposition to capitalism across the third world, and preparing the ground for the global expansion of precarity which characterises neoliberal globalisation. With post-Cold War proclamations of a supposed ‘End of History’, there would no longer seem to be any alternative to neoliberalism, an economic model which – as was evident, for instance, in the 2016 US presidential election and the UK’s referendum on its place in the European Union of the same year – fosters the conditions for a right wing populism verging on fascism. Noticeably, Orwell’s doublethink, as Jonathan Beller observes, ‘represented the collapse of any dialectical thought by the real, practical imposition of what he has already glimpsed as the end of history – the eternal domination of humanity by an immortal, relatively static, and ultimately unconceptualizeable totalitarian society’ (2006, 288). So, under neoliberal globalisation, are we still able to realise a non-fascist life, and can a hesitant cinematic ethics help us to do so? Or has that potential been closed off by the right and the clock reset, perhaps forever, to a moment before the advances made by socialism and communism?

In this book I argue that all is far from lost. Neoliberalism suggests that if history cannot be known, all that remains is for people to adapt to the political status quo, accommodating themselves as best they can to a system which is the root cause of the quotidian exhaustion which distracts them from political engagement (Chandler and Reid 2016, 5). By contrast the time-image shows that people have the potential to react anew, to imagine a different future (different ways to inhabit society) by drawing on different ideas of history: hesitation, not to stultify, but to empower.7

This fine grain of difference is crucial to the political intent behind this use of hesitation. It is the same kind of understanding as that of the subtle differences between lying, sarcasm, irony, disingenuousness, etc, which we must learn to distinguish as children. This distinction is so difficult to explain to children because even though they are all the same operation – words spoken in a falsifying relationship with the truthfulness of their literal meaning (as any child will tell you, this is still basically lying) – they all have entirely different agendas with respect to the target recipient (deceit, hurtfulness, humour, gentleness, or as appropriate to context). As they all create cognitive dissonance, it is this intention which is the key to their difference. Whilst it might seem tempting to consider the playful tone of certain practices to work against their deceitful intent (i.e. to argue that only lying is really lying, and that the rest are all more innocent activities), in fact with all such practices there is the potential to wilfully deceive in line with a political agenda (e.g. irony can equally be a weapon of the right (Wilson 2017)). It is not tone that makes the difference, then, but the intent behind the use of what we might consider, after Mikhail Bakhtin, double voiced discourse (1981, 324–327).

The right may have co-opted thinking from the left to its own ends, but the idea that this nullifies the potential of the time-image to keep alive – and provide ethical encounters with – the lost pasts of world history should be treated with scepticism: it may well be right-wing spin. After all, the Eurocentric history of colonial modernity is, although the official story, also the ultimate in fake news. It is enunciated in the face of common sense and at the expense of the people it excludes – O’Brien requires Winston to believe that he is holding up five fingers even though Winston can clearly see four, or, the press are informed that the presidential inauguration was the most well attended ever, even though it very apparently was not. For contemporary thinkers like Naomi Klein, it may be possible to defeat such ‘shock politics’ (which seek to work via cognitive dissonance to open up a gap between ‘events and our initial ability to explain them’), if we ‘tell a different story from the one the shock doctors are peddling, a vision of the world compelling enough to compete head-to-head with theirs’ (2017, 7–8). This includes, she notes, a vision of history which can expose the ‘role played by the politics of division and separation’ during the last five hundred years of colonial modernity (100). It is this process, of proposing a positive alternative (or alternatives), which a world of cinemas has been involved in for decades. Specifically, using time-images it seeks to create a hesitation with respect to the official story of Eurocentric world history: cinema against doublethink.

The time-image, that which Deleuze thought to express the potential for a new political cinema from the Global South (1985, 207–215), has the potential to speak for the underside of modernity (those excluded by colonial modernity). This is what the analyses of transnational histories in Chapters 3–6 variously illustrate. Rumours of the time-image’s death, then, are greatly exaggerated.

To answer my earlier question: what is so important about cinema being against doublethink is that its opposition speaks with political intent to the heart of the struggle over global structural inequality. With this in mind, I now leave contemporary politics, and delve into cinema: to move from what is important about this, to how we can see it on screen.

For the remainder of this Introduction, I firstly detail this argument in more depth, signalling the theoretical areas which I will engage with in the two following chapters. I then provide one key example of what I am discussing, El abrazo de la serpiente/Embrace of the Serpent (Colombia/Venezuela/Argentina, 2016). This recent film clearly indicates what is at stake in the analysis found in Chapters 3–6, wherein are outlined different stories of transnational history being told across a world of cinemas.

Denying the denial of coevalness

What does it mean to encounter another past, even a lost past, on screen? This is not to say that we see someone else’s past in its totality, and certainly not just by encountering a character with a potentially different background to that of the viewer. These are not pristine histories, if such a thing even exists. These are not ‘prosthetic’ memories, of pasts never experienced by the viewer but which can, once seen on screen, inform the viewer’s present (Landsberg 2004; 2009). Nor are they quite the ‘post memories’ which we may try to invent to recuperate eradicated pasts, such as those of parents ‘disappeared’ by repressive political regimes (Hirsch 1997). Neither do they quite function as evocatively affective memory images of state terror, aesthetically rendered so as to resonate with similar memories, irrespective of the specificities of national experiences of torture and disappearance (Chaudhuri 2014, 84–114; see Chapter 2). Rather, in the films discussed herein, what is foregrounded is our inability to connect with someone else’s history, or just, history, in a way that can inform the present (the inability of a lost past to function as prosthetic or post memory). What is glimpsed, instead, is something of the vastness of the world history in which we are immersed (hinted at by the fleeting encounter with the lost past), and therefore of the relative centrality of our own informing past within what we might consider a global, planetary, ‘world memory’ (Deleuze 1985, 95 and 113).

At best, encounters with other pasts are offered as fragments, stories, myths, hints or allusions, the sum of which are the leftover glimpses of a totality we will likely never recover: the virtual past, world memory. Even so, these encounters can be extremely powerful, and through them a world of cinemas is thus attempting to deny what Johannes Fabian terms ‘the denial of coevalness’ (1983). In this oft-quoted phrase, Fabian describes the refusal – attendant on colonial practices, but equally apparent in how the world is generally viewed from its privileged centres – to recognise that the histories of others are the same ‘age’ as those of the colonisers, ethnographers (and so on) who set out to conquer or observe otherness.

Fabian charts how a hegemonic conception of time – as progressive and linear – culminates in the naturalising of time by evolutionary thought with Charles Darwin (26). This creates a ‘stream’ of time, with some cultures ‘upstream’, some ‘downstream’ (17), effectively distancing the other from the (as it were, present point in) time of the observer (25). This view, of one time within which some cultures are more developed than others, has accompanied Western dominance of the world since ‘“universal Time” was [… ] established concretely and politically in the Renaissance in response to both classical philosophy and to the cognitive challenges presented by the age of discoveries opening up in the wake of the earth’s circumnavigation’ (3).

Fabian’s return to the Renaissance origins of colonial modernity, when Europe reoriented with respect to other cultures from a position relative in space to one relative in time (Mignolo 2003, xi) – is not coincidental. As Quijano notes of the way that Europeans categorised the indigenous Americans they encountered after 1492, banishing them to a primitive, under-developed past:

Their new racial identity, colonial and negative, involved the plundering of their place in the history of the cultural production of humanity. From then on, there were inferior races, capable only of producing inferior cultures. The new identity also involved their relocation in the historical time constituted with America first and with Europe later; from then on they were the past [… ] and because of that inferior, if not always primitive.

(2008, 200)

The denial of coevalness, in the case of the Americas the expulsion of such sophisticated civilizations as that of the ‘Aztecs, Mayas, Chimus, Aymaras, Incas, Chibchas’ (Quijano 2000, 551) to the past, was the temporal dimension to the colonial exploitation which followed after 1492. As Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri argue, it was in the context of Renaissance humanism’s confrontation with the discovery of the Americas that ‘Eurocentrism was born as a reaction to the potentiality of a newfound human equality; it was the counterrevolution on a global scale’ (2000, 77). Structural inequality, then, is at the dark heart of the last five centuries of the world history of colonial modernity, and it is justified by a view of time that banishes others to the past.

Now, however, due largely to decolonial and postcolonial thought, amidst a world of cinemas we are increasingly asked to decolonise such thinking by situating our own past in relation to the complexities of world history. We are challenged, five hundred years later, to refuse to see other pasts as backwards, primitive, or lost somewhere in the past: challenged to observe – as Mignolo has it – ‘the denial of the denial of coevalness’ (2003, ix). Whilst decolonial and postcolonial thought brings this to the foreground, in addition the idea of the time-image (which Deleuze considers to emerge in post-war Europe) indicates that for many decades there has been a struggle over the eradication/remembrance of pasts across a world of cinemas. This is increasingly a ‘trending’ issue for scholars of a world of cinemas because of the importance of the Deleuzian idea of ‘world memory’ which underpins such scholarship (see Chapter 2). Even so, this is not universally acknowledged in the field. This is because, I believe, how we conceive of modernity directly influences how we understand cinema to negotiate the transnational histories stored away in world memory.

For example, consider Mary Ann Doane’s rightly famous and illuminating exploration of how, under ‘capitalist modernity’ (2000, 4), film helped Western societies of the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century negotiate the contrary pulls between the rationalisation of time (the uniform standardisation of time by technological means in the realms of work, travel and communication) and temporal contingency (the heterogeneous nature of time which erupted in newly packed urban areas in chance or ephemeral encounters (10-11)). By contrast, we can equally understand these contrary pulls within cinematic time to negotiate the much larger concern of the perpetual disappearance of contingent histories from world memory, due to the rationalising forces of colonial modernity (the ‘counterrevolution on a global scale’). As has already been explored with respect to specific postcolonial locations globally (e.g. Lim 2009), it is not the historically recent Western urbanisation of the Nineteenth Century, resulting from the industrial revolution, which created this struggle. Rather, it was the rise to global prominence of the West since the Fifteenth Century, via the eradication of the histories of all those from whom it took its wealth: colonial modernity. Thus the field of Film Studies may not universally recognise the wider issue, of the struggle over eradication/remembrance of world history, due to the worldview underpinning the analysis of some scholars.

The histories which are encountered in a world of cinemas are not necessarily those of others, then (as this depends on where you are looking from), but they do belong to the whole world, to world memory. They emerge in time-images which indicate the perpetual struggle that exists between the eradication of histories (forgetting), and the hesitancy with respect to what we believe to have been history under such circumstances (remembrance). This is the potential that the time-image has to keep alive the remembrance of lost pasts, with histories planetary, indigenous, political, and economic being illuminated (in Chapters 3–6) from across a world of cinemas. Together such different examples of pasts, ‘bigger’ than that of the nation, illustrate the international occurrence of current world cinematic engagements with transnational histories on film. But, as noted at the start of this Introduction, it depends on our worldview as to whether or not this is immediately apparent.

The closeness between these transnational histories and the planetary or world history which encompasses them is evident once considered in relation to colonial modernity. This is due to the convergence of ideas like that of the modern world system (from sociology) with those of the Columbian Exchange (environmental history), certain views on the Anthropocene (geology), the Capitalocene (ecology), all (like Latin American Philosophy) focusing around the pivotal date of 1492 (see Chapters 1–4). Even so, this is not to construct an, as it were, transnational universalism around colonial modernity.

Why not? How are we to be sure that this pitfall is avoided?

G. W. F. Hegel’s Nineteenth Century notion of world history is now notorious. For Hegel, the ‘development’ of the consciousness of freedom, by the ‘spirit’, proceeds from supposedly primitive Asian origins to its apex in Western (surprise surprise, Hegel’s own Northern, Protestant, Germanic) modernity’s realisation of universal freedom in the nation-state (1837, 103). America, or European settler colonist America at least, is thus identified as the ‘land of the future’ (86). Hegel’s denial of coevalness, intrinsic to his inability to appreciate the irony of a discussion of freedom in the context of massive global colonisation, is apparent in his negative estimation of the development of the indigenous peoples of the Americas. Noticeably, this argument emphasises military technology as measure: ‘The weakness of the human physique of America has been aggravated by a deficiency in the mere tools and appliances of progress – the want of horses and iron, the chief instruments by which they were subdued’ (82). Such a denial elides both the historical facts surrounding the advancement of African, Asian and American civilisations prior to the Fifteenth Century (for example, the indigenous peoples’ of the Americas knowledge of zero long before it was known in Europe (Shohat and Stam 1994, 55–61; Mann 2005, 215–216)), and refuses to recognise, in the case of the Americas, the imported diseases (smallpox, malaria, yellow fever) which ravaged the indigenous populations.8 Hegel, then, in line with Quijano’s argument, banishes indigeneity to (Europe’s) supposed past.

But of course, this is erroneous. As Dussel indicates, a non-Eurocentric world history focusing on migrationary patterns rather literally gives the lie to Hegel’s worldview. Humanity moved Eastwards out of a centre in the Pacific (Neolithic people migrating from Asia to the Americas), long before the arrival of Europeans (1992b, 73–90; 1998b, 9–13; see also Mann 2005, 151–158). This before we begin to consider Hegel’s denial of societal and cultural developments in the peoples that were eradicated by Europeans, conquerors so proud of the way their technology drove bloodthirsty coloniality. Yet Hegel’s position remains informing of the normative story of world history – which runs through to late Twentieth Century thinkers of the supposed post-Cold War ‘End of History’, like Francis Fukuyama and Samuel Huntington (Stam and Shohat 2012, 62).

By contrast, exploring transnational histories on film is to follow Dipesh Chakrabarty in a search for ‘a global approach to politics without the myth of a global identity’ which can address the challenge of climate change to our grasp of history, but without, in contrast to a Hegelian universal, subsuming particularities (2009, 222). Chakrabarty asks:

How do we relate to a universal history of life – to universal thought, that is – while retaining what is of obvious value in our postcolonial suspicion of the universal? The crisis of climate change calls for thinking simultaneously on both registers, to mix together the immiscible chronologies of capital and species history.

(2009, 219–220)

As I demonstrate by introducing the viewfinder of a Dusselian ethics (see Chapter 1), a world of cinemas, in its examination of transnational histories, includes human histories within a broader, encompassing planetary history (see Chapter 3). It has become the archive of the world’s memories, storing transnational histories in which the intertwined pasts of capital, humanity as a species, and the planet more broadly, are seen to be inextricably linked. This is the case whether these transnational histories predate the invention of the nation, with examples ranging from the several billion year planetary history of the Earth (in Uncle Boonmee and Nostalgia for the Light (Chapter 3)), to the several centuries’ of the North Atlantic trade circuit as engine for Europe’s rise to global centrality in the world system (Chapter 4, How Tasty and Even the Rain), or, because they involve various nations, as in the history of the Cold War (Chapter 5, The Act of Killing and At the Foot), or more recently of neoliberal globalisation (Chapter 6, Carancho and Lady Vengeance).

To glimpse the intertwined histories of capital and humanity within planetary history requires a recontextualisation of cinema’s engagement with history, globally. An approach is needed which can grasp the local and global ramifications of transnational histories of exclusion – stepping beyond the ‘limiting imagination of national cinema’ (Higson, 2000) without creating an all-encompassing transnational universal. Taken together, these different transnational histories address what Chakrabarty indicates is the ‘question of a human collectivity, an us, pointing to a figure of the universal that escapes our capacity to experience the world’ (2009, 222). It is in this way, to answer my own question, that this potential pitfall can be avoided.

To ground this interpretation of transnational histories I turn to methods drawn from various disciplines, in particular, Latin American Philosophy. Dussel’s work is not as well known in the UK as elsewhere, although his influence is evident in the works of much-discussed thinkers like Paul Gilroy, Charles W. Mills, and Mignolo. Naturally, this is far from the only possible way to proceed, but in Dussel we find an appropriate grounding for this hermeneutics due to the role of world systems analysis in his thinking. This is a paradigm, after all, which functions to ‘reorient’ us away from established Eurocentric conceptions of world history (Frank 1998). Dussel, by turns, is joined by a clamour of voices from elsewhere, including, in no particular order: Quijano, Mignolo, Chakrabarty, Gilroy, Mills, Hardt and Negri, Michel Serres, Carole Pateman, Rey Chow, Andre Gunder Frank, Arjun Appadurai, Heonik Kwon, Hannah Arendt, David Graeber, Giorgio Agamben, Maurizio Lazzarato, É tienne Balibar, Hayden White, Steven Shaviro, Alia Al-Saji, Eduardo Viveiros de Castro et al. Although the work of, to paraphrase Franco Moretti, ‘distant viewing’ (2001; 2013) undertaken herein (see Chapter 1), belongs to the heritage of Ella Shohat and Robert Stam’s Unthinking Eurocentrism (1994) (this book can be similarly understood as involving us in the unthinking of doublethink), it is the specific combination of (a reconstructed) Deleuze with Dussel (and these various other voices) which reveals how a world of cinemas offers an ethics of hesitation with respect to normative assumptions about world history. As an introductory example of this, I now turn to Embrace of the Serpent.

Encountering other worlds

The Oscar-nominated Embrace of the Serpent, an internationally distributed art film with funding from the Hubert Bals Fund (the International Film Festival of Rotterdam) and Programa Ibermedia, is a movie some might consider ‘familiar’ to the festival circuit. It is a product of the complex geopolitics of the relationship between festivals and filmmaking in the Global South (Martin-Jones and Montañ ez 2013a). Whilst it might thus be tempting to dismiss such a movie, by emphasising the potentially self-serving loop involved in the film and resulting discussions of it (i.e. the view that the international festival circuit cynically fosters such ‘views’ of the world to ‘develop’ Western thinking at the expense of the others it continues to exploit for profit), I maintain nevertheless that there is much to be gained from a considered approach to this film.

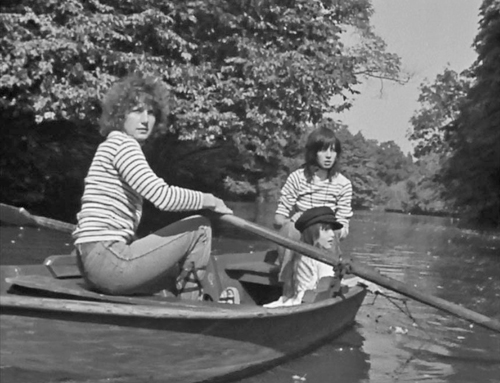

Embrace of the Serpent is based on diaries of European colonisers encountering indigenous Americans (see Figure 0.2) (as is How Tasty, discussed in Chapter 4), and like all the films discussed herein it is a time-image. The action alternates between two temporal planes (1909 and 1940), a story repeating itself of mankind’s increasing inability to communicate with the natural world due to the exploitation of nature for material gain. This topic is a feature of the contemporary life of the viewing public, with ideas about ecology dating back to the 1960s (Sessions 1995, x) through a revival of interest in indigenous views of religion, society and place in the 1970s (Deloria 1972, 146), Gaia Theory (the 1980s) and the Natural Contract (the 1990s), to the now commonplace concern with environmental sustainability, or ‘Green’ politics (2000s onwards). Embrace of the Serpent links the colonial past to the globalised present with examples of armed conflict over the control of areas where rubber can be harvested, and the search for a plant (yakruna) which grows on the rubber (with properties exploitable for purposes medicinal or military). It thus evokes viewer awareness of the contemporary operations of multinational capitalism (so-called ‘Big Pharma’), and the global reach of the military-industrial complex.

FIGURE 0.2 Encountering a lost past creates hesitation over history, in El abrazo de la serpiente/Embrace of the Serpent (Ciro Guerra, 2016).

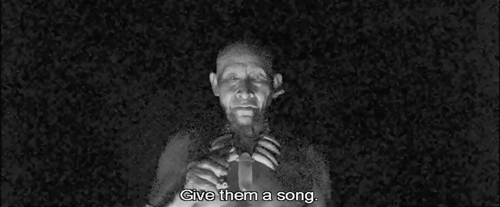

The viewer is aligned with the perspective of an indigenous protagonist,9 the shaman, Karamakate (Nilbio Torres in his younger incarnation, Antonio Bolivar Salvador as an old man), who encounters two Westerners (one German, the other, Evan (Brionne Davis) from the USA), in the two historical periods. Karamakate initially believes that it is his destiny, as one of the last of the Cohiuano people, to continue their ‘song’. At the close of the film, however, he passes it on as dream/memory/knowledge to Evan, and also, directly to the viewer. As Karamakate hands Evan the yakruna potion he speaks his realisation, that his destiny was, in fact, to pass on knowledge of his people’s ‘song’ to other people: ‘I wasn’t meant to teach my people. I was meant to teach you. Give them more than what they asked for. Give them a song. Tell them everything you see, everything you feel’ (see Figure 0.2). As he prepares to blow the powder up Evan’s nostrils, directly looking at the audience in close up, Karamakate states: ‘You are Cohiuano’.

The cinematic vision which follows commences with a helicopter shot, moving rapidly over treetops, as though Evan were flying above the rainforest. The panorama slows, as we travel along the course of a mighty river, through a ravine, into vast canyons, and across mountaintops, all accompanied by chanting on the soundtrack. Finally we catch sight of the serpent which Karamakate told Evan he would meet – the winding river, seen from above. Suddenly the landscape is replaced by Karamakate as a young man, sitting crosslegged, against a luminescent light background. As he opens his eyes, and then his mouth, the light from behind him shines out through his face, obliterating his presence. The light is used to transport us, as via a match cut, to luminescent celestial starscapes, which morph by turns into brightly coloured renditions of shapes similar to those of rock paintings, and yet seemingly at one in terms of magnitude with the starscapes of the cosmos seen previously. The most striking of these is the final one, which positions a human stick figure amongst what appears to be an expanding cosmos.

This vision offers another way of remembering, from an oral tradition, which may better inform the present (exploitative) way of being in the world perpetuated by capitalism. This affective moment seemingly demonstrates how the history, or ‘song’ of Karamakate’s people is at once of the Earth (the winding river), but also historically of the Universe (the patterns in the stars). Thus, we are shown, we can encounter the past, memory, history, myth, ‘song’ of another people (in this instance, of an indigenous tribe eradicated during armed conflict over the region’s rubber), or more accurately, in such a cinematic glimpse we can encounter the knowledge that it once existed.

The highly mediated nature of the encounter with the past is significant regarding what we can and cannot know about the past from cinema. The scene is a mixture of the opening helicopter shots of forested landscapes of Ten Canoes (Australia, 2006) mingled with the psychedelia of 2001: A Space Odyssey (UK/USA, 1968) and the cosmological emphasis of Nostalgia for the Light (see Chapter 3). The rather cliché d mashup of aesthetic elements from previous films serves to make of this history: a recognisably temporal otherness (as in the starchild sequence of 2001 evoked by the light emanating from the young Karamakate); an ethnic otherness situated in a specific place (as in the Ten Canoes-like helicopter shots); with a cosmological scale linking planet to universe (as in the celestial landscapes akin to those in Nostalgia for the Light). Indeed, the rather cinematic nature of this vision of another’s past is emphasised by Evan’s awaking the next morning in the rainforest, the sudden shift from night to day foreshadowing the emergence of the film’s viewers into the light as they exit the auditorium. Thus we are clearly not supposed to understand this history, or Karamakate’s worldview, in any detail. Only to realise its existence as different from our (or at any rate, Evan’s) own.

Admittedly, when Karamakate says ‘you are Cohiuano’ it may well be intended as a suggestion of a prosthetic memory for those audience members able to connect with this cosmology. During the film Karamakate gives various indications as to his belief in what would seem to be a dynamic relationship which his people have with both the stars and the Earth. For instance, in an induced vision Karamakate sees a meteor, which he calls Watoí ma, and afterwards relates that the Jaguar has told him that on hitting the earth it has been transformed into a boa. Both the Jaguar and the snake appear prominently in the film, in moments seemingly divorced from the human narrative – the point being, of course, that they are not disconnected from it at all even if there is no direct interaction with these species. For those who do understand these symbols, then, there may perhaps be the potential to take on Karamakate’s peoples’ memory as prosthesis – to become Cohiuano. Even so, it is not a given that such symbols will be understood, even in the region where the film was made, due to the effectiveness of several centuries of European colonial campaigns to burn all written sources of pre-Christian beliefs in the Americas (such as the Mayan sacred text, the Popol Vuh) and the reliance on oral history for the preservation of many such creation myths (Christenson 2003, 15–21). After all, one of the tactics used by the right in the USA, to create confusion surrounding climate change in the manner indicated by Latour, is to align with creationist beliefs that the Earth is only around 6000 years old. The very feasibility of such recourse to a Christian creation myth by a dominant settler colonist culture indicates the effectiveness of this systematic destruction of equivalent indigenous myths. In which case, what about those who do not have any way to connect to this history, wherever they may be? Those for whom it cannot act as a prosthesis?

It is possible to research the significance of what Karamakate says, of course. Answers might be found in ethnographic works of the period depicted, such as those of C. H. De Goeje (1943), which illuminates how, within a cosmology of eternal beings who are only encountered in dream (in which, say, the reality of a Jaguar which we may encounter in the forest is but an earthly manifestation of its associated eternal cosmic being (1-2)): Watoí ma can be the name for both a meteor and a fire-spirit (47); the Jaguar may be a divine avenger possibly capable of devouring mankind at the destruction of the world (41); and the serpent might represent the mother goddess and founder of the universe, who can also be the essence of time (26). Yet few will undertake such research, or be privileged enough to be able to do so, and those who do are only able to imperfectly grasp the actual significance of the iconography.

Alternatively, curious viewers might turn to contemporary anthropological work to learn more about the Jaguar as itseke or ‘dawn time being’ in Amazonian cosmology, including its strong association with place (Heckenberger 2005, 79; 352 n13). Or, more likely than either of these approaches, of course, they might turn to emerging works exploring the film’s attempt to reconsider how encounters with indigenous tribes in the Amazon are depicted cinematically (Berghahn 2018; Mutis 2018), or simply search the internet and uncover Peccadillo Pictures’ accompanying press notes, where they might learn of the indigenous view of time (as ‘a series of multiple universes happening simultaneously’ (Anon. 2015, 5)) and an explanation for the final vision, as:

A visual representation of the iconography of the Barasana tribe, the primitive drawings are representative of the childlike state and can only be accessed through the dreamworld therefore this scene invites the audience into a realm that merges past, present and future.

(7)

But even here, the press pack’s ‘Amazonian Glossary’ (10) does not provide a comprehensive answer to all these points surrounding animals and their possible cosmological or mythological significance. Rather, in line with the film’s central premise, all that is garnered is a glimpse of a lost past – one which we cannot know through the film.

For perhaps the majority of viewers, then, this is not a transparent window into either Karamakate’s culture or its past. What is very recognisable about the scene, rather, is the very idea that we are seeing a history being evoked cinematically. What is familiar is the cinematic encoding of such an encounter. There is a sense of enlightenment in the scene, as though a Road to Damascus conversion, of literally ‘seeing of the light’ for Evan. What he remembers is similarly coded as mythical: it takes place in a time before the present, as seen in the indicators of cosmology amidst recognisable cinematic markers of indigeneity. Thus Evan’s revelation is not that of the content of another history, but simply of its existence. The revelation, recognisable to cinematic audiences worldwide, then, is that we are seeing the encoding of history as otherness.

The potentially varied viewing experience I am describing here is perhaps rather like that of encountering an Aboriginal map in an art gallery in, say, Australia. For those who can read it, it is a map. For others, it is possible to understand that it is a map, even if it is different from what one expects of a map (for some the painting on bark may resemble more an art work), and even if one is unable to read it or to understand the terrain it refers to. The fact that another visitor could easily read the map and envisage the contours of the land only emphasises the importance of the encounter with the realisation of the existence of a history which many do not (yet) know.

Indeed, what many may be confronted with, in both such a map and a film like Embrace of the Serpent, is an altogether different idea of what history is, than that of the linear, developmental model of colonial modernity. For many, the encounter, instead, is with a history invested in place, and a cyclical notion of time informing the present not uncommon to indigeneity in the Americas (Deloria 1972, 97–111). The reason we cannot know this history is because it is not a history to be understood after a Eurocentric fashion. Indeed it is not even necessarily clear whether Karamakate’s people’s song is a history per se, or whether it is actually more akin to a religious experience of a place in the cosmos, emanating as the vision does from a sacred site harbouring the last flower of the yakruna (280–282). In any case, it is a (lost) past, rather than a history: not only because colonial modernity denies equality to such pasts, and views of history, but also because it was never meant to be recorded in a linear, teleological fashion. What Evan and the viewer realise in this cinematic vision of the song of Karamakate’s people, is another (spatial) relationship to history. So, whilst it is accurate to speak of transnational history (within the broader encompasser of world history), in a world of cinemas it is more accurate to speak of colonial modernity’s lost pasts, than its lost histories.

For many, then, Embrace of the Serpent does not offer a prosthetic memory of the history of Karamakate’s people. They have practically all been slaughtered anyway, and even Karamakate himself is concerned about how much he has forgotten of what he used to know. Rather, it is a glimpsed memory of another way of understanding humanity’s place in the world, another view of history and of the interconnectedness of the universe. This realisation of difference is the recognition of coevalness, a chance to deny its denial.

What is made obvious is that, far from being a ‘primitive’ other to the modern European travellers, Karamakate possesses botanical wisdom beyond that developed by Western civilisation. This is precisely why he is sought out. The past of his people may not have ‘developed’ towards scientific discoveries (the gramophone player which features in the jungle is purposefully incongruous, indicating Hegel’s mistaken insistence on the supposed superiority of Europe’s technological development), but it did advance coeval with Western civilisation, as is evident in Karamakate’s far superior knowledge of and engagement with the rainforest ecosystem. His Western visitors are, by contrast, ailing or incapable of completing their jobs there without him.

Thus the film seeks not to implant another memory, as prosthesis, but only to indicate the many (lost) memories which we may never know. This, so as to relativise the centrality of hegemonic Western understandings of history. As Karamakate tells Evan: ‘I was not meant to teach my people, I was meant to teach you’. But what he is able to impart to his companion, and the viewer, is not an understanding of the culture and history of his people (their ‘song’), but only the knowledge that it once existed, rendered as a cinematic ‘revelation’ of this fact.

What does this illuminate regarding a world of cinemas’ opposition to doublethink? Embrace of the Serpent indicates the distinction between the argument I am making here and Rey Chow’s analysis of what she calls ‘liberal fascism’, or ‘the fascist longing in our midst’ (1998, 15, 32), by which she describes an Orientalist binary evident in certain contemporary enunciations of multicultural difference. Like Chow, I also reconsider the history of theorising about fascism in light of the philosophical works of Deleuze and Guattari. With political events in 2017 increasingly suggesting that a non-fascist life may be more difficult to live in the near future, there is a distinct danger that the films discussed in this book might be understood to present unknowable pasts, because they bolster the mythical structure of unknowable otherness which Chow describes as emblematic of ‘liberal fascism’. It is through this process, after all, that white consciousness constructs itself in relation to otherness by maintaining the belief that ‘“we” are not “them”, and that “white” is not “other” [… ] which can be further encapsulated as “we are not other” [… ] fascism par excellence’ (1998, 31).

Yet, rather than evidencing such a ‘fascist longing in our midst’, I argue that films like Embrace of the Serpent offer us a rather different revelation. Namely: ‘other’ pasts exist which are not ours, so our past cannot be the centre of world history. This revelation, after all, leaves Western characters like Evan in Embrace of the Serpent shaken in their previous belief in themselves, and their exploitative relationship to the world: shaken in their adherence to colonial modernity as historical norm. This is not the same as the affirmation of the inviolable centrality of white supremacy via the encounter with an unknowable other. Whilst it would be idealistic (even in an age of increasingly universal precarity) to stretch this to the conclusion that, ‘we are (also) other’, nevertheless, there may even be, if only fleetingly, the revelation that ‘we are coeval.’10

Hence the argument I propose is not that we cannot know difference. Only, rather, that the first step to realising that difference is important to the self, is in acknowledging that the self exists in a relational position which challenges the contingent centrality of our own story of history. In short, these films ask us to ‘get over ourselves’ by realising our relative position in world history. As Paul Gilroy argues, emphasising the importance of remembering the blood-soaked and ransacked colonial pasts in an era when such remembrance is discouraged unless as a form of ‘whitewashed [… ] imperialist nostalgia’ (2005, 3), it is no longer sufficient to look to gain self-knowledge through exposure to strangers. Instead:

We might consider how to cultivate the capacity to act morally and justly not just in the face of otherness – imploring or hostile – but in response to the xenophobia and violence that threaten to engulf, purify or erase it. The opportunity for self-knowledge is certainly worthwhile, but, especially in turbulent political climates, it must take second place behind the principled and methodological cultivation of a degree of estrangement from one’s own culture and history.

(2005, 67)

It is precisely via a sense of estrangement from one’s own centrality to the world, brought on by encounters with otherness in cinema, that the ethics required of the history of colonial modernity can be investigated. The remembrance of lost pasts, then, is not solely of importance for the cultures whose histories these pasts inform, but also for the re-appraisal of the ‘centre’, of that which is normative, by the making strange of the official story of world history.

This is not to say that a world of cinemas is oriented towards helping a white, male, Western viewer realise the normative nature of their assumed central place in world history. It is, rather, to argue that this can be the effect upon such a person (like Evan) of exposure to a world of cinemas. This, rather than any sense that they can appropriate memories of others as one can a prosthetic past – a position which, rather, might be open to just such a critique (that such films only exist to inform Western viewers of the pasts they have eradicated).

It is likely often the case that this provincialisation of the heritage through which coevalness is unthinkingly denied to others, is temporary. Like Evan in Embrace of the Serpent, ultimately we all awake and exit the auditorium. All we can expect to understand, realistically, these films illustrate, is that otherness – more specifically, other pasts – subsist along with us: that other histories (temporalities, cosmologies) exist parallel to our own. But this revelation is not provided so as to better separate viewers from such pasts, to consolidate an Orientalist self/otherness binary, as per Chow’s observations of idealised visions of multiculturalism. Rather, together these films provide encounters with those excluded from colonial modernity, over its long and complex history, in order to foster remembrance of these lost pasts within our shared world memory.

After all, it is not necessarily the case that an indigenous audience will know the past hinted at in Embrace of the Serpent. Even in parts of Amazonia, with the ruins of pre-Columbian civilizations now lost to the jungle (Heckenberger 2005, 10), and, more generally in the Americas, so much indigenous heritage purposefully extinguished by colonisation (as noted above, through the burning of sacred texts like the Popol Vuh), the glimpse of a lost past may not serve so dissimilar a function as it does for a Western viewer. As also indicated above, the film seems to purposefully indicate this, by having Karamakate, the last of his nearly extinct tribe, observe that he has forgotten much of his own past. Indeed, indicating the complexities of how the lost pasts of the Americas can come to be ‘remembered’ via the Western invention of film (a film playing on an international film festival circuit whose biases are themselves geopolitically complex (Martin-Jones and Montañ ez 2013a, 29–30)), Embrace of the Serpent concludes with both a dedication to ‘all the peoples whose song we will never know’ and a simultaneous acknowledgement that the only record of many of these peoples may be the travel diaries of Western interlopers in the Americas (such as those which inspired the film).

The point for all viewers, then, is ultimately the same. Embrace of the Serpent indicates the former existence of the now lost past, so as to remind the viewer of the normative and naturalised (rather than normal and natural) nature of the history which they believe to be informing of their present. For those viewers willing and able to hesitate with respect to what such a revelation may mean for them, Eurocentric notions of history may become relativised, or ‘unthought’ (Shohat and Stam 1994).

Cinematic ethics, ecology, colonial modernity

The grouping of films explored here is reminiscent of the prevailing view of a world of cinemas, that it offers a ‘cinema of resistance’ to the consequences of economic liberalisation felt increasingly under globalisation. This is seen, for example, in post-Cold War festival films like La promesse/The Promise (Belgium/France/Luxembourg/Tunisia, 1996) and Xiao Wu/The Pickpocket (China/Hong Kong, 1997), through Cidade de Deus/City of God (Brazil/France, 2002) and Tsotsi (UK/South Africa, 2005), and on to the present with I, Daniel Blake (UK/Belgium/France, 2016). Such films belong to a heritage of political cinema which stretches back at least as far as the 1960s and 1970s, when third cinema (for Mike Wayne a ‘cinema of liberation’ (2016, 18)) emerged across the Global South, inspired by thinkers like Frantz Fanon (1961, 23), to resist inequalities in colonial, neocolonial and postcolonial contexts. My recourse to Dussel’s philosophy of liberation (Chapter 1), suggests a direct link to this heritage, even if such struggles of the Cold War, and again today under globalisation, are understood (after Dussel and others), to be later phases in a five-hundred-year history of colonial modernity. Nevertheless, what this cinema of resistance might be resisting, I believe, is what is not so clear-cut nowadays. How we conceive of resistance affects our ability to grasp the transnational histories which a world of cinemas is engaging with, after Chakrabarty, at the intersection of the (ecological) histories of capital and humanity on Earth.

A direct address to the spectator by a face from within the film is a feature of nearly every film explored in the book. As Embrace of the Serpent emphasises when Karamakate breaks the fourth wall in the final scenes, the faces which stare out at the viewer in many of the films analysed are evidently those of the excluded, upon whose disenfranchisement (including genocide and enslavement) the West’s global dominance was manufactured. Yet, across the films explored the list of such disappeared pasts is increasingly both human and nonhuman, and includes: animals, extinct species, spirits, mythological creatures, slaves, indigenous peoples, women, the disappeared and murdered, the poor, even the farmed landscapes and mined depths of the Earth itself. Thus, although films which use direct gazes to camera to reverse the imperial gaze have long been explored (Kaplan 1997, 154–194; Downing and Saxton 2010, 50–61),11 current debates surrounding ecology give a different meaning to what is resisted in and by a cinema of resistance. Encountering such images is still to encounter global alterity (at least, for those viewers for whom the on-screen images depict otherness), but the underside of colonial modernity is far more inclusive of the histories of the Earth than definitions of political cinema as a cinema of resistance may typically acknowledge.

As the discussion of Uncle Boonmee in Chapter 3 illustrates, a character like the once-human but now monkey-spirit Boonsong (Geerasak Kulhong) indicates that the encounters on offer in a world of cinemas do not just include the face to face inter-human interactions discussed by Emmanuel Levinas, whose advocation of ethics as first philosophy has been so influential across disciplines in the early Twenty-First Century. Perhaps ironically, Levinas was inspired by his encounter with a dog, Bobby, whilst a prisoner of the Germans during World War Two (1967). Yet, in spite of the importance of another species in providing Levinas with his sense of humanity, the ethics which he ultimately formulated was not equally inclusive of all others (see Chapter 1). To grasp the extent to which Boonsong is representative of alterity, then, other philosophical voices are required. Dussel’s ethics of liberation provides one way of realising Boonsong’s otherness with respect to the correlation between colonial modernity and the Anthropocene (the relatively recent entwinement of human history with that of the planet; see Chapter 1), indicating that, because the denial of coevalness under colonial modernity extends beyond human others, so too must our understanding of the cinema of resistance.

This is to follow the emergence of a body of work on ecocinema since the 1990s, which asks us to view with, as it were, different eyes (for instance, those of another people, or even another species) what we think we already know about cinema (Pick and Narraway 2013, 8). It is to attempt to grapple with what Timothy Morton (2013) would consider the ‘hyperobject’ of, say, the Anthropocene, a history ‘massively distributed in time and space relative to humans’ (1) with a temporality so much larger than that of human history that we are only ever able to experience a (local) aspect of the much larger whole (1–4). A world of cinemas, then, is asking for an ethical engagement with the difficulties we face in the present moment of realising hyperobjects – like climate change, or the Anthropocene – as a product of colonial modernity (Chapters 1 and 3). It does so by demonstrating how various histories (which have all impacted transnationally across nations and national histories) are histories of unevenness, histories of the denial of coevalness upon which coloniality is established.

A world of cinemas and the Global South

The importance of the voice from the Global South offered by a world of cinemas, as Garcí a Má rquez reminds us, lies in its potential to remember otherwise than the Eurocentrism of the official history of the world maintained by the West – that against which decolonial and postcolonial thought positions itself. The official story has a vested interest in forgetting this colonial legacy and its continuation in the contemporary world. Such forgetting creates the continued crises, economic and environmental, which threaten humanity’s existence in order to generate immense wealth for a global minority. It is this which a world of cinemas increasingly attempts to challenge and resist. Enabling an unthinking of Eurocentrism, what Dussel dubs the ‘superideology’ of the modern world system after 1492 (1998b, 34; 2003a, 63), a view from the Global South needs to be understood as a geopolitical rather than a geographical categorisation. As noted above with respect to the degree of poverty in a wealthy nation like the USA, the fault line of inequality now runs directly through societies regardless of hemisphere, creating the ubiquitous cheek-by-jowl coexistence of Global North and South. The memory of the world’s lost pasts is thus to be found in the cinemas of the Global South, wherever that may be.

I am not claiming that in staging the encounters with lost pasts these films are capable of liberating viewers, in the sense that liberation theology looks to liberate those excluded by modernity from conditions often equitable with misery (see Chapter 1). Before we celebrate the rejuvenative powers of world cinemas too unthinkingly, the distribution and consumption of films from around the world through portals like the international festival circuit has been critiqued, since the time of third cinema, for enabling a Western, or at least Globally Northern, consumption of misery – as though it were an option on the global cinematic menu, its realities all too soon forgotten after the credits roll (Rocha 1965). This geopolitics is not innocent, and accordingly I do not make claims for a cinema of liberation.

Rather, I argue that a world of cinemas upholds the ‘liberation principle’ by which ethical acts have the potential to transform the existing system (Dussel 1998b, 355–431; Mendieta 2003a, 13), by asking viewers to (re)consider their relationship with the excluded other of colonial modernity in a moment of hesitation. This is a pause in our lives during which past attitudes can be addressed, and the existing, normative view of history potentially relativised (see Chapter 2). By recognising the historical alterity (the lost pasts), of those excluded by modernity, a world of cinemas can thus assist in the denial of the denial of coevalness.

This realisation regarding a world of cinemas may offer something useful for our understanding of troubled times. Contemporary political events illustrate the continued relevance of liberation (in politics, ethics, theology, etc.), despite how dated the term may sound due to its association with postcolonial, Cold War, or third world origins. The political maelstrom in which parts of the West has become engulfed since the millennium is due to this longer world history which has its roots in the discovery of the Americas. In 2016 both the US presidential race and the UK’s referendum on its place in the European Union indicated continued racial tensions, and a marked degree of imperialist nostalgia, in the discourses of the right. This outrage towards otherness on the part of white privilege (despite the global minority status of whites) throws into sharp relief the waning of its historical hegemony, in some part due, paradoxically, to the universal precarity encouraged by neoliberalism.

In addition, the almost quotidian regularity with which acts of terrorism are reported globally indicate the embeddedness of the Orwellian state of total war that has emerged since the USA’s post-9/11 ‘war on terror’ (Chomsky 2016, 239–258). Yet the correlation of many of these acts with colonial histories, and the continued resourcing of capitalism from ‘peripheral’ areas of the world (not least of which are oil-rich areas of Western Asia) is rarely acknowledged in the discourses through which such violent acts are explained in Western media outlets (Chomsky 2016, 256–257). This was very apparent in the indigenous American and climate change activist opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline (which threatens sacred sites and the Sioux tribe’s water supply) at Standing Rock in 2016. It took a Facebook ‘check in’ of over a million people in support of the protestors just to compel mainstream media outlets to cover in depth a story by then long circulating online (Torchin 2016). As the political manufacturing of consent turns to the manufacturing of confusion (deliberately fostered cognitive dissonance so as to leave many unsure how, or even whether, to vote), what is revealed is how post-imperialist white nationalism typically seeks to cleanse its chequered history via doublethink (Steele 2006, 107).

This context requires a more foregrounded appreciation of the world historical events which underpin contemporary conflict, and the inequalities which foster it. A world of cinemas, whilst it may not cause any revolutions (although it has taken part in a few), can readily contribute to changing perceptions. Amidst so much that is troubling, films offer a way to consider who ‘we’ are in relation to each other, and indicate the need to ensure inclusion and a more equally distributive flow to global wealth before the continued coloniality of neoliberalism (at home as much as abroad) ferments the widespread resurgence of fascism. But to grasp this begins with which films we watch, and how we regard them: the question of how we encounter other ‘worlds’ in a world of cinemas.

A meeting of worlds

In Cinema Against Doublethink the exploration of the world memory in which so many lost pasts are stored is joined by a grounding of interpretation in world history and world systems analysis, which by turns underpin a particular viewpoint on ethics taken from a world of philosophies (i.e. Dussel). Each of these worlds offers a dimension which seeks to enhance knowledge: by taking explorations of history in film beyond national to transnational history; film-philosophical work beyond European thinkers; and study of a world of cinemas beyond comparisons with world music and world literature (an approach roundly critiqued in the 2000s (Martin-Jones 2011, 4)), to world history and world systems. Thus, it challenges any too Eurocentric viewpoint on world history which does not account for the contrasting and competing experience of it, felt around the world (Kwon 2010, 7).

Discussing the world’s memories is no longer the sole province of philosophy. For example, it is a topic emerging in history, surrounding questions over how we might consider a shared experience of ‘remembering’ world history as either ‘global memory’ or ‘transnational memory’ (Iriye 2013, 78–79), and again over the ‘form in which we think of the past’ as ‘increasingly memory without borders rather than national history within borders’ (Huyssen 2003, 4). A world of cinemas has a huge amount to offer such an interdisciplinary debate, as it can provide us with a shared experience of a history, or memory, which reaches beyond that of our collective national imaginings (Anderson 1983) towards those of our broader transnational mediascapes (Appadurai 1990).