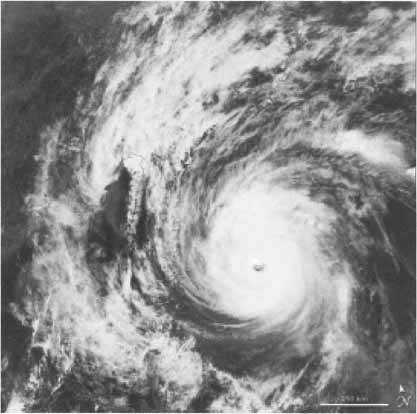

Typhoon Nock-Ten hit Taiwan in October 2004.

(Photo Courtesy of NASA)

The Elective Presidencies of Lee Teng-hui and Chen Shui-bian

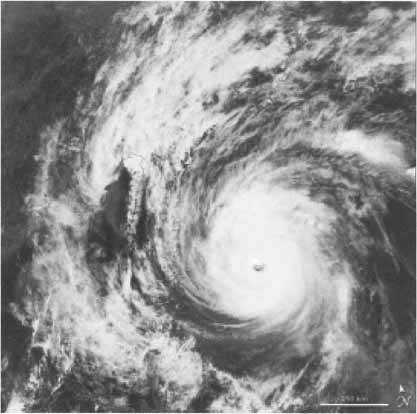

Typhoon Nock-Ten hit Taiwan in October 2004.

(Photo Courtesy of NASA)

The presidential election of 1996 in the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan could be taken as a watershed event marking the considerable success of the island’s evolution during the postwar era. Politically, the first-ever direct election of the president represented the culmination of Taiwan’s democratic transition from the late 1980s through the early 1990s, which had been far more peaceful and consensual than almost anyone had foreseen. In particular, President Lee Teng-hui, who won a convincing victory at the polls in 1996, had transformed the ruling Kuomintang (KMT) or Nationalist Party from a widely perceived instrument of domination by minority Mainlanders to a Taiwanese party that was actively seeking ethnic reconciliation and justice. Moreover, the election of the Democratic Progressive Party’s (DPP) Chen Shui-bian as president in 2000 underlined the success and “consolidation” of Taiwan’s democratic transition.

Economically, Taiwan’s extremely rapid growth of the 1960s through the 1980s had decelerated somewhat, but the country was still numbered among the East and Southeast Asian “miracle economies.” The one major outstanding problem was Taiwan’s lack of international status due to the pressures on the international community of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) which claimed sovereignty over Taiwan. Even here, though, Lee Teng-hui’s “pragmatic diplomacy” had proven effective in enlarging the ROC’s “political space.” For example, China’s attempt to intimidate Taiwan by “missile diplomacy” during the 1995–96 Taiwan Strait crisis quickly ended after the election.

Taken together, therefore, Taiwan’s success in politics, economics, and foreign policy at the time of the 1996 presidential election might not too fancifully be termed the “Three Triumphs.” Certainly, Lee won the election quite handily with 54 percent of the vote, compared to just 21 percent for the candidate of the leading opposition party, and 15 percent for a KMT defector who ran as an independent. Yet, as indicated in Table 17.1, these Three Triumphs would soon turn into a corresponding set of “Three Threats.” Politically, Chen’s victory in the 2000 presidential election created a magic moment for many in Taiwan, but the magic soon disappeared in the face of continuing feuding with the KMT majority in the Legislative Yuan. Politics in Taiwan soon became marked by bitter partisanship, political gridlock, and the re-emergence of bitter conflict over the highly emotional national identity issue. Economically, Taiwan suffered through a sharp recession in 2001–2 that ignited fears of the “hollowing out” of its industrial economy and of the dangers inherent in the island’s growing economic dependence on and integration with China. Most ominously, the threat from China grew as both governments became increasingly hostile toward each other, at least in part because of rising nationalism on both sides of the Taiwan Strait.

Consequently, Taiwan’s seeming success of the Three Triumphs in the mid-1990s was not a prelude to “living happily ever after.” Still, despite the Three Threats, during the late 1990s and early 2000s, Taiwan did not suffer any catastrophes in politics, economics, or foreign affairs. Rather, both domestic politics and cross-Strait relations were marked by continuing tensions, which remained unresolved (and perhaps were irresolvable in the short run) but which also appeared to be well short of inevitably becoming destructive to the polity and society that have developed in postwar Taiwan. This chapter, hence, discusses the second presidential term of Lee Teng-hui (1996–2000) and the first presidential term of Chen Shui-bian (2000–2004) in terms of two tensions: between growing political institutionalization and the rise of symbolic politics internally; and between the stability of the diplomatic status quo and the growing pressures in both Taipei and Beijing to challenge that status quo.

Triumphs and Threats in Recent Taiwan Politics

Area |

Triumphs |

Threats |

Political |

Fairly easy democratic transition; Lee’s success in promoting ethnic justice and reconciliation; victory of DPP’s Chen Shui-bian in the 2000 presidential election suggests “democratic consolidation” |

Growing gridlock and inflamed conflict over highly “symbolic issues,” such as national identity during Chen’s first term |

Economic |

Rapid growth and several structural transformations from 1950s through 1990s |

Hollowing out of industrial economy; 2001 recession threatens even high-tech economy |

International status |

Ability of “pragmatic diplomacy” to gain more “face” for Taiwan in international community beginning in late 1980s |

Growing threat from PRC, exacerbated by rising nationalism in both China and Taiwan after the 1995–96 Taiwan Strait crisis |

The significant level of political stress in Taiwan’s domestic politics at the turn of the twenty-first century can be seen as the result of the tension (or perhaps race) between two ongoing trends. One is the growing “institutionalization” of political competition and conflict, while the other is the rise of “cultural symbolic politics.” Political institutionalization means that there are regularized procedures both for selecting officials and making policy decisions. These procedures, in turn, help to legitimize governments and the decisions that they make and to reduce political conflict to manageable proportions. Thus, political institutionalization is often seen as a key component of political development and democratization.1 In contrast, cultural symbolic politics refers to issues that are highly emotional and focus on the fundamental status and well-being of particular groups in a society:

The cultural style of politics is symbolic, not technical. … Because of the tendency of practitioners of cultural politics to occupy an issue space that is nonnegotiable, divisive political conflict often ensues. … If an issue can be framed to carry enough fundamental moral weight, then compromise or support of a candidate holding the “wrong” position is unthinkable.2

Consequently, cultural and symbolic issues are almost impossible to resolve no matter how well institutionalized a government might be. The fact that even the best political institutions may not be able to handle certain issues very well or even adequately raises two other points as well. First, while democratic institutionalization may be an important component of political development, there is no guarantee that particular political institutions will function well, and too much institutionalization can bring rigidification in decision making, which can often be counterproductive.3 Second, while political institutions are often conceived primarily in terms of constitutionally or legally constituted organizations (e.g., legislatures and cabinets) or procedures (electoral laws), informal practices can also be considered institutions and have profound implications for political, economic, and social outcomes.4

Taiwan’s democratization illustrates all of these more abstract theoretical points. The democratic transition of the late 1980s and early 1990s seemingly completed the political institutionalization of the country. Previously, the ROC was widely credited with having a well institutionalized executive bureaucracy that was quite effective in foreign affairs and promoting economic development.5 Yet, the authoritarian government structure left the process for making major policy decisions rather shadowy, arbitrary, and certainly uninstitutionalized. Democratization promoted political institutionalization in two important ways. First, the selection of officials became institutionalized through regular elections in a process that Shelley Rigger terms “Voting for Democracy.”6 Second, policy making became regularized through the actions of democratically selected governmental bodies and officials (e.g., the president, Legislative Yuan, etc.).

Taiwan’s democratic transition and the political institutionalization that accompanied it brought several real and potential problems along with them. Some of Taiwan’s central political institutions, such as the hybrid presidential-parliamentary system, had depended on the authoritarian dictatorship of the KMT party-state. Thus, democratization exposed how imprecise and, therefore, potentially unstable some of these institutional relationships were. Taiwan also faced the fairly serious possibility that cultural symbolic politics in the form of conflicts over national identity could tear the society apart. The KMT’s association with the “white terror,” most especially the horrendous tragedy of the murderous repression of the February 28, 1947, uprising (for a detailed discussion see Chapter 10 by Steven Phillips), made many fear that democratization would unleash ethnic conflict that had earlier been contained only by authoritarian controls.

Democratization certainly brought serious challenges to Taiwan that involved numerous political institutions. Probably the key institution for meeting these challenges was the political party system. The first part of this section, therefore, provides an overview of the evolving nature of the party system during the presidencies of Lee Teng-hui and Chen Shui-bian. This is followed by two sections discussing how Lee and Chen shaped political competition and conflict on the island. As will be seen, the party system first seemed to be promoting political institutionalization and integration, but then began to be associated with polarization and gridlock in the face of the growing centrality of symbolic politics in Taiwan’s campaigns.

The nature of the political parties that compete for power in a democracy has important implications for that nation’s political life. Party systems are generally distinguished by the number and size of the significant parties in the polity and by whether some or all of these parties appeal to the broad middle of the electorate or to more extreme ideological niches. The major distinction in the number of parties is between two-party and multiparty systems; another important distinction is between whether there is a dominant party, or whether the major parties are fairly competitive and similar in size. There is clearly some relationship between the number and size of parties on the one hand, and their electoral strategies on the other. When a fairly even balance between two major parties exists, they tend to pursue “catch-all” strategies aimed at appealing to the “moderate middle” of the electorate. In contrast, small parties, especially in multiparty systems, are more likely to make highly ideological appeals.7

Taiwan went through its democratic transition with a two-party system in which the old ruling party, the Kuomintang, remained dominant. Real two-party competition commenced with the founding of the DPP in 1986 in direct defiance of martial law. As Table 17.2 shows, Taiwan clearly had a two-party system, with the KMT holding a dominant position early in its democratic transition. For example, the KMT outpolled the DPP by two-to-one margins in the late 1980s and at the beginning of the 1990s. Starting with the 1992 elections for the Legislative Yuan, which the KMT won by the considerable margin of 53 percent to 31 percent, this situation evolved toward more even two-party competition for two reasons. First, the DPP raised its level of support markedly from 25 percent in 1986 to just under 40 percent in most elections by the mid-1990s. Second, the New Party split off from the KMT in 1993 and won about 15 percent of the vote in several elections in the mid-1990s, although its popularity dropped precipitously thereafter. Consequently, by the late 1990s, Taiwan appeared to have a primarily two-party system, in which the KMT had a significant but far from overwhelming advantage in most elections. Indeed, the DPP actually won the 1997 elections for city mayors and county magistrates (chief executives), beating the KMT 43 percent to 42 percent and, much more important, winning twelve of these twenty-three positions compared to eight for the KMT and three for independents.

Table 17.2

Electoral Support of Major Parties and Blocs

I. Original Party System: Primarily KMT vs. DPP |

|||

KMT (%) |

DPP (%) |

New Party (%) |

|

1986 National Assembly |

64 |

24 |

— |

1986 Legislative Yuan |

67 |

25 |

— |

1989 Legislative Yuan |

59 |

29 |

— |

1989 Magistrates/Mayors |

56 |

30 |

— |

1991 National Assembly |

71 |

24 |

— |

1992 Legislative Yuan |

53 |

31 |

— |

1993 Magistrates/Mayors |

47 |

41 |

3 |

1994 Provincial Governor |

56 |

39 |

4 |

1995 Legislative Yuan |

36 |

33 |

13 |

1996 President |

54 |

21 |

15 |

1996 National Assembly |

50 |

30 |

14 |

1997 Magistrates/Mayors |

42 |

43 |

2 |

1998 Legislative Yuan |

46 |

30 |

7 |

II. The Old Party System Fractures Chen Soong Lien |

|||

DPP (%) |

IND (%) |

KMT (%) |

|

2000 Presidential |

39 |

37 |

23 |

III. The Revised Party System: The PanGreen (DPP and TSU) vs PanBlue (KMT, PFP, and NP) Blocs |

|||

PanGreen (%) |

PanBlue (%) |

||

2001 Legislative Yuan |

41 |

50 |

|

2001 Magistrates/Mayors |

45 |

37 |

|

2004 President |

50 |

50 |

|

2004 Legislative Yuan |

46 |

50 |

|

2005 National Assembly |

50 |

45 |

|

2005 Magistrates/Mayors |

43 |

52 |

|

Sources: Cal Clark, “Democratization and the Evolving Nature of Parties, Issues, and Constituencies in the ROC,” in Taiwan’s Modernization in Global Perspective, ed. Peter C.Y. Chow (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2002), p. 142. Central Election Commission, Government of Taiwan, www.cec.gov.tw.

The 2000 presidential election then provided a major shock that transformed the party system. The election quickly turned into a three-candidate race among DPP nominee Chen Shui-bian, KMT nominee Lien Chan, and James Soong who ran as an independent after failing to get on the KMT ticket. For the last several months of the campaign, the race became extremely close among the three leading candidates. In the last few days of the election, many voters evidently decided that the uncharismatic Lien Chan could not win, and the standard bearer of the “ruling party” garnered only 23 percent of the vote. Chen won with 39.3 percent to Soong’s 36.8 percent. The aftermath of the election proved to be even more disastrous for the KMT. Hostility between Soong’s supporters and KMT’s loyalists led Soong to create a new party, the People’s First Party (PFP). Moreover, Lien Chan pushed out his former patron Lee Teng-hui as KMT chairman to take responsibility for the election loss. Lee was soon at war with the KMT establishment and became the “godfather” of another new party, the Taiwan Solidarity Union (TSU).8

Taiwan’s party system then moved quickly to one based on two competing blocs or coalitions of parties. The DPP and TSU became allied in the PanGreen coalition (named for the primary color in the DPP’s flag), while the KMT, PFP, and New Party formed the PanBlue bloc (named for one of the colors associated with the KMT and its symbols). As the bottom half of Table 17.2 indicates, these two coalitions competed quite evenly over the next few years. Chen Shui-bian retained the presidency for the Greens in 2004, by the razor-thin margin of 50.1 percent to 49.9 percent, while the Blues won narrow margins in the 225-seat Legislative Yuan in 2001 (115 to 100) and 2004 (114 to 101). The results of the 2001 city and county executives elections were somewhat contradictory in that the PanGreen candidates received more votes than the PanBlue ones (45 percent to 37 percent), but the Blues won more contests (12 to 9). More recently in 2005, the PanGreen Coalition won the May National Assembly elections 50 percent to 45 percent, while the PanBlue bloc won the elections for county magistrates and city mayors in December 52 percent to 43 percent. Even though the latter was widely viewed as a major defeat for the Greens and President Chen,9 the overall vote totals were almost exactly the same as those in the 2001 Legislative Yuan elections. Thus, while the support levels for the two blocs have fluctuated a little during this decade, the party system remains fairly evenly balanced and quite competitive.

In addition, the shake-up of the party system in 2000 clearly worked in the favor of the DPP and the PanGreen bloc since it ended the era of Kuomintang domination of Taiwan’s elections. For example, in 2000 Lien and Soong combined won 60 percent of the vote to Chen’s 40 percent, suggesting that the DPP won only because of the split between the opposition candidates. Yet, Chen won re-election in 2004 in a two-party race against a PanBlue ticket of Lien for president and Soong for vice president, and the PanBlue margin over the PanGreen parties in voting for the Legislative Yuan dropped substantially from 53 percent to 30 percent in 1998 as compared to 50 percent to 41 percent in 2001 and 50 percent to 46 percent in 2004.10 Clearly, the split between Lee and the KMT hurt the Blues and created an extremely competitive political environment.

By the middle of the decade, the nature of the party system did seem to be changing again in a significant fashion. As was noted earlier, during Chen’s first administration the party system was marked by competition between two blocs, each having one larger and one smaller party. Perhaps because of the fairly even partisan balance, the political battles were intense and polarizing; and the ongoing division between the Green executive and Blue legislature resulted in policy paralysis and gridlock that were widely decried across the political spectrum.11 Many analysts believed that Taiwan’s party and electoral systems were at least partially to blame for this political hostility and polarization. The minor parties (the TSU in the Green bloc and the PFP in the Blue bloc) were more radical on the divisive national identity question and pressured the major parties away from moderate stances. Moreover, Taiwan’s large multimember electoral districts, in which only a fairly small percentage of the vote was necessary for victory, encouraged radical candidates whose victories made it harder for the parties to compromise.12

Both constitutional reform and practical politics in 2005 appeared, at least initially, to hold the potential for attenuating this polarization and gridlock. However, little changed in the short term, and in early 2006 Taiwan’s politics were as divisive and vicious as ever. Constitutionally, the amendments adopted by the National Assembly in 2005 included a major change in the electoral system that abolished the multimember legislative districts and replaced them with a combination of single-member districts and a central party list for proportional representation, and cut the size of the Legislative Yuan in half. This reform had the backing of both the DPP and KMT, which is not surprising because it would help the major parties at the expense of their smaller allies.13 Still, its actual effects, if any, must await the future. Even so, there are some signs the minor parties are fading somewhat. They did not do very well at the polls in 2005, getting 6 to 7 percent of the voting in the May National Assembly elections and only 1 percent in the December vote for the chief executives of local government. The PFP appears especially vulnerable to disintegration because a quarter of the PFP members of the Legislative Yuan defected to the KMT in late 2005 and early 2006.14 Thus, Taiwan may well be heading back to an essentially two-party system.

In terms of practical politics, leadership changes in both the DPP and KMT during 2005 seemed to give some potential for moderating extreme partisanship, but in actuality had little impact. In the DPP, the mayor of Kaohsiung, Frank Hsieh, assumed the premiership in early 2005 and indicated that he wanted to pursue a policy of “coexistence” that would de-escalate tensions with the Blue-controlled Legislative Yuan, while Ma Ying-jeou, with a reputation for avoiding vicious politics, won the KMT chairmanship in July 2005 with an overwhelming 72 percent of the vote in what could only be described as a strong rejection of old-style KMT politics. Yet, there was little change in Taiwan’s polarized partisanship, and Hsieh resigned as premier in January 2006, citing both gridlock with the Blue bloc and less than harmonious relations with President Chen (as well as being tarnished by the Kaohsiung scandal that had hurt the DPP at the polls in the December 2005 elections).15

One of the key factors determining how a party system operates is the nature of the major political issues in a nation. Table 17.3 presents an overview of the KMT’s and DPP’s positions on the major issues in Taiwan’s politics since the country’s democratic transition commenced in the mid-1980s. These data clearly indicate two central facets of the issue divisions or cleavages in Taiwan. First, Taiwan’s politics has evolved over the last two decades toward a concentration on the single issue of national identity. Second, the party system worked to weaken the emotional and symbolic effects of the national identity issue during the 1990s. Following the 2000 presidential election, the partisan divide on this issue became increasingly heated and intransigent.

Table 17.3

Party Positions on Major Issues in Taiwan

Late 1980s |

1990s |

Early 2000s |

|

Democracy |

KMT old guard trying to hold back reforms pushed by DPP and KMT reformers |

Largely achieved |

Moot |

Black and gold politics |

Fairly marginal on political agenda |

KMT seen as most tainted, issue clearly helps DPP |

DPP Administration undercuts its ability to use this issue |

Social welfare policy |

Specific issues (e.g., environment and women’s rights) pushed by social movements |

DPP takes lead in pushing for expansion of welfare state; yet, KMT also co-opts popular DPP policies |

Fairly secondary at present |

National identity and ethnic justice |

Growing DPP challenge to KMT’s “one China” policy and to considering Taiwanese as Chinese |

Polarization between pro-Independence DPP and pro-Unification KMT evolves when first KMT under Lee Teng-hui and then DPP take more moderate and nuanced stances |

Growing polarization over PanGreen’s appeals to Taiwanese nationalism and PanBlue’s rage after 2004 vote |

A number of issues have been important in Taiwan politics over the last few decades but only for limited periods of time. The first central issue in Taiwan was democratization, which dominated the political agenda in the ROC from the early 1970s through the late 1980s.16 Yet, Taiwan’s successful democratic transition rendered this issue moot by the mid-1990s. Moreover, the partisan implications of the democracy issue were not entirely clear cut because both the opposition DPP and reformers within the KMT had strongly pushed for political reform. Thus, both parties could realistically claim credit for Taiwan’s “political miracle.”

Two other issues have also affected at least some elections in democratic Taiwan, but now have generally faded in importance. One of these is corruption or what has been called “Heijin” or “black and gold politics” (black signifying gangsters and gold rich businessmen). Under the KMT authoritarian regime, corruption and crime had remained fairly limited at what might be termed “first world” rather than “third world” levels. Democratization unfortunately unleashed burgeoning corruption as both business and gangsters were able to gain access to the increasingly expensive political processes.17 As the party in power, the KMT was obviously by far the most tainted by “black and gold politics.” In contrast, the DPP and initially the New Party undoubtedly benefited from their much “cleaner” images. For example, the Soong scandal during the 2000 presidential elections, in which the KMT accused Soong of mismanaging huge slush funds when he had been the party’s secretary general, played a major role in that campaign.18 Yet, the election of Chen Shui-bian created a DPP administration, thereby making it much harder for the PanGreen forces to use this issue. More recently, for example, several scandals, especially the one concerning the Kaohsiung Rapid Transit Corporation, were seen as important factors in the Greens’ poor showing in the 2005 elections for county magistrates and city mayors.19

Second, while social welfare policy has been less contentious on Taiwan than in most developed nations, significant party differences did emerge during the 1990s in this area. During the authoritarian era, Taiwan’s social welfare programs were quite modest; and the government repressed the labor movement to help the island maintain its niche in the global economy as a source of low-cost industrial goods. Consequently, the DPP took some interest in criticizing the regime on these issues; and, in fact, Yun-han Chu and Tse-min Lin argue that the DPP’s appeal on these issues contributed considerably to its electoral success in the early and mid-1990s.20 Yet, the opposition party’s principal interest in the national identity question limited the aggressiveness of its policy thrusts in these areas. Instead, independent “social movements,” such as environmental groups and farmers’ and women’s associations (but perhaps surprisingly not labor unions), took the lead in bringing these issues to the national agenda during the 1980s.21 Furthermore, once social welfare policies, such as medical insurance were developed, they created strong bureaucratic and popular constituencies that cut across party lines.22 Correspondingly, the KMT moved to take reformist positions on most of these issues once the popularity of the positions espoused by the social movements and the DPP was established. Thus, social welfare policies now seemingly have little play in Taiwan politics.

In contrast to these “issues of the past,” the question of national identity or “ethnic justice” has long been seen as perhaps the overriding concern in the polity, even when the direct expression of the issue was repressed by martial law. Taiwan’s democratization, therefore, was widely expected to unleash Taiwanese nationalism on two interlinked but distinct issues: (1) rejection of the Mainlander dominated political regime; and (2) growing hostility toward and the absolute rejection of China’s claim to sovereignty over Taiwan which was ironically, at least tacitly, supported by the Kuomintang’s policy of “Mainland Recovery.” At the onset of the 1990s, both the DPP and KMT seemingly placed opposing bets on how the citizens of Taiwan, who were being increasingly empowered by the country’s democratization, would respond to this issue. The DPP bet that the end of authoritarian controls would permit Islander resentments to be expressed, winning over voters to the DPP as the champion of Taiwanese nationalism. For example, the DPP added support for Taiwan Independence to its Charter in 1991. Conversely, the KMT bet that the satisfaction of the general population with the prosperity created by Taiwan’s “economic miracle” (see Chapter 13 by Murray Rubinstein) would make them supportive of the political status quo both domestically and in cross-Strait relations with China. Thus, the Kuomintang continued to adhere to their version of the “One China” principle that the ROC represented the legitimate government of all China.

A little thought would have suggested that neither of these bets were particularly well placed. On the one hand, the KMT’s strong performance at the polls in the late 1980s and early 1990s demonstrated that the DPP’s assumption that it could ride to power on a wave of Taiwanese nationalism was quite dubious. On the other hand, the KMT ignored signs of growing resentment against the treatment of the Taiwanese culture and language of the large majority of the population as second class and failed to realize that democratization would make the maintenance of official myths untenable and that clinging to them would also give the PRC more leverage over Taiwan. In such a situation of two less than desirable alternatives, therefore, the potential opened up for a creative policy entrepreneur to transcend the existing policy debate. President Lee Teng-hui responded to this opportunity with what appeared to be inspired statesmanship at the time of his direct election as president in 1996.

As Chapter 16 described in some detail, Lee Teng-hui’s creative leadership played a large role in the completion of Taiwan’s democratization. In particular, he used the 1990 National Affairs Conference to transcend the deadlock in the still semi-authoritarian Taiwan and to create a blueprint and momentum for establishing fully democratic institutions. Likewise, he was able to transcend the seemingly intractable divide between the DPP and old KMT on national identity, thereby promoting ethnic reconciliation and justice. However, Lee’s leadership had some drawbacks. He was associated with the rise of “black and gold politics” as he used business support to help overcome the power of entrenched KMT factions. Moreover, by the end of his presidency, he had become associated with rising tensions on national identity and cross-Strait relations.23

Lee’s consolidation of power in the early 1990s led to the ‘Taiwanization” of the Kuomintang in several key aspects. Most directly, the top levels of the party and government were no longer dominated by Mainlanders, creating a “Taiwanization” of the political elites in very literal terms. Several important policy changes followed that emphasized the “new” KMT’s commitment to Taiwan. Lee ended the ROC’s claims to Mainland China and Mongolia, symbolically indicating that the government was now one of, by, and for the citizenry living on Taiwan and its associated islands. Lee formally apologized for the horror of the “2-2-8” tragedy, and a large and attractive memorial to the incident and its victims was constructed in downtown Taipei. The “new” KMT, thus, separated itself from the White Terror of the past; and, at least on the surface, Lee seemed successful in promoting ethnic reconciliation. Lee also aggressively began to pursue Taiwan’s readmission to the United Nations, a policy previously opposed by the DPP and advocated by the KMT. This was an extremely popular policy because most people on Taiwan, whatever their partisan affiliation, felt aggrieved by the country’s lack of international status, dignity, and “face.” Lee, in fact, managed to straddle the national identity issue quite astutely, implicitly portraying himself as a moderate between the pro-Independence DPP and the pro-Unification “old” KMT. In addition, the KMT’s image of moderation on national identity was augmented after 1993 when the New Party split from it and became increasingly associated with advocating eventual reunification with China.24

For its part, the DPP began to moderate its position on Taiwan Independence in the mid-1990s as well. This was due in part to a radical image on this issue that seemed to be limiting its popularity. Thus, when DPP candidates emphasized Taiwan Independence in their campaigns, as they had done in the 1991 National Assembly, 1994 provincial governor, and 1996 presidential elections, the party’s share of the vote dropped noticeably (see Table 17.2). Consequently, some (but far from all) DPP leaders began to argue that Taiwan was already an independent nation, making a Declaration of Independence immaterial. Indeed, the evident desire of most DPP politicians to move toward a more centrist view on national identity caused several leaders and groups to defect from the DPP and to form the Taiwan Independence Party (TAIP) in 1996, claiming that the DPP had forsaken its major issue, which helped to moderate the image of the DPP.25

Following his direct election as president in March 1996, Lee again seemed poised to act as a unifying statesman in promoting Taiwan’s political and economic development. He called for a National Development Conference (NDC) in December 1996, aimed at replicating the 1990 National Affairs Conference’s ability to break through political gridlock and meet the growing challenges that faced Taiwan. Each of the three major parties appointed representatives to the conference; and President Lee also invited representatives of academia, the business community, and social interests to participate. Series of pre-conference meetings and workshops were organized to help define issues and create a basis for consensus, leading to the work of the NDC being divided into three important areas: economic and social development, cross-Strait relations, and constitutional reform.

Given the high level of party combativeness in Taiwan, it might have been surprising that consensus could have been reached in any area. Yet, all three major parties quickly agreed on the general development objectives of loosening government controls, forcing the government to adopt more fiscally prudent policies, promoting infrastructure development, and protecting the environment. What was truly astounding was the three-party consensus that emerged in the area of cross-Strait relations. The agreed-on positions, moreover, generally reflected support for President Lee’s “pragmatic diplomacy” of aggressively seeking to protect Taiwan’s sovereignty and upgrade her international status, while paying allegiance to the idea of unification with China as a goal for the indefinite future. This certainly appeared to constitute a decisive victory for Lee’s moderate or centrist approach to the national identity question.

The process was much more contentious concerning constitutional reform; President Lee and the KMT made two unilateral proposals, which circumvented the careful process of cooperation and consensus building. One was to increase the powers of the president vis-à-vis the Legislative Yuan and the other was to downgrade the provincial government substantially. Ultimately, the DPP agreed to both proposals, making common purpose with Lee. Lee would benefit from increased powers during the rest of his presidency, while the DPP believed that it had a much better chance of winning a presidential than a legislative election. Lee’s proposal about the provincial government seemed to be aimed at slapping down the popularly elected Governor James Soong who had become a rival within the KMT, and this was also consistent with the DPP’s position that Taiwan was not a part (i.e., province) of China. The New Party walked out of the NDC on the last day in protest of this KMT-DPP deal but only after approving the consensus in the other two areas. Moreover, the approval of these constitutional amendments by the National Assembly in the summer of 1997 exposed significant opposition within both the KMT and DPP that was only overcome by considerable arm-twisting on the part of Lee and DPP chair Hsu Hsin-liang.26

President Lee’s political domestic strategies continued to transcend the ethnic divide into the late 1990s. Most important, perhaps, he created the basis for a new national identity during the very high profile 1998 campaign for Taipei’s mayor in which the KMT’s Ma Ying-jeou challenged Chen Shui-bian, the popular DPP incumbent with approval ratings of 70 percent. To help Ma overcome the disadvantage of his ethnic heritage, Lee had him proclaim his loyalty to Taiwan in a manner that redefined the categories of national identity on the island:

Taiwan’s President Lee Teng-hui added drama to the Taipei mayoral campaign when he asked the KMT nominee, Ma Ying-jeou, “Where is your homeplace?” Ma, a Mainlander, replied in broken Minnan dialect, “I’m a New Taiwanese, eating Taiwanese rice and drinking Taiwanese water.”27

Lee’s concept of a “New Taiwanese” identity was open to everyone and implied that old ethnic enmities could be left in the past, creating a new approach to national identity that appeared to be widely popular across the political spectrum.28

By the turn of the twenty-first century, the political institutionalization of Taiwan’s democratic transition and the creative leadership of Lee Teng-hui in both shaping and using these institutions had prevented the question of national identity from becoming an explosive “cultural symbolic issue.” This could be seen both directly and indirectly in the functioning of the party system. Directly, as illustrated in Figure 17.1, the major parties both moved toward the middle on national identity and cross-Strait relations, leaving the extreme positions to fairly inconsequential minor parties. Indirectly, Taiwan’s parties began to treat each other in quite pragmatic, opportunistic, and cynical terms. As noted above, the National Development Conference produced a temporary alliance of the KMT and DPP. Simultaneously, however, the DPP and New Party, who were clearly opponents on national identity, were cooperating at times to harass the Kuomintang majorities in the Legislative Yuan and the National Assembly, while factions within the major parties could be very conflictual as well.29

This growing moderation even carried over to the 2000 presidential campaign in which Chen Shui-bian and James Soong were seen by many (particularly their opponents) as representing the extremes. While all three candidates certainly criticized each other and especially caricatures of each other, they all advocated the moderate position of toning down hostilities with Beijing while at the same time strongly defending Taiwan’s existing sovereignty, positions that differed from one another much more in phraseology than substance.30 Thus, political institutionalization had seemingly trumped symbolic politics. Shelley Rigger, for example described Taiwan as “post-nationalist” and clearly implied that the answer to the question “Is Taiwan Independence passé?” was “yes.”31

Yet, politics in Taiwan are always churning, and the transformation of the party system occasioned by the 2000 presidential system brought national identity and symbolic politics to the fore. One key factor here was the political transformation of Lee Teng-hui. Following his split from the Kuomintang, Lee became increasingly radical about national identity and cross-Strait relations, as he proclaimed “the sadness of being Taiwanese” rather than the joy of being a “New Taiwanese.” Indeed, the Taiwan Solidarity Union jumped over the DPP to become the leading advocate of Taiwan Independence in the PanGreen coalition. Times had changed indeed.

The 2000 presidential election brought changes Taiwan. The major change, of course, was that Chen Shui-bian and the DPP gained power. The major thrust for the rise of symbolic politics in the early twenty-first century came from the increasing Taiwanese nationalism expressed by Chen as his term progressed and especially in the run-ups to the 2004 elections for president and Legislative Yuan. Chen’s motivation is somewhat unclear, though. Did he feel freer to express his long-cherished beliefs as he gained a stronger grip on power? Or, did he become something of a prisoner to the “base constituency” of the DPP, which saw national identity and ethnic justice as the overriding issues in Taiwan? In any event, politics in Taiwan moved toward the model of recent political dynamics in the United States, where the major parties focus their appeals on their most ideologically committed supporters rather than trying to compete for moderates in the middle of the political spectrum.32

The election of the DPP’s ticket of Chen Shui-bian and Annette Lu represented a break from the past in more than one way. The DPP had finally achieved power in what could only be considered a direct repudiation of Taiwan’s (and the old KMT’s) authoritarian past. For example, both candidates had been jailed for their political activities in the 1980s (Chen for eight months and Lu for five years). The images of these two on national identity differed somewhat, presumably representing some conscious ticket balancing. During the course of the 1990s, not just the DPP but Chen Shui-bian himself moved away from Taiwanese nationalism and support for Taiwan Independence. Shelley Rigger noted that, for example, Chen had supported Taiwan Independence when he ran for the legislature in the early 1990s from a multimember district where Taiwan’s electoral system of the “single nontransferable vote” means that a fairly small percentage of the voters can elect a candidate, thereby encouraging radical stances. In contrast, when he ran for mayor of Taipei in 1994 and 1998 and for president in 2000, he took much more measured positions on national identity issues.33 As mayor of Taipei from 1994 to 1998, he pursued a successful reformist agenda, was able to work with a city council that was split in partisan terms and was highly popular. Thus, Chen, like the DPP as a party, had evidently concluded that moderation and pragmatism on national identity formed a prudent policy. In contrast, Annette Lu was much more of a firebrand, although her relations with Chen appeared a little strained throughout his first term.34

Chen Shui-bian thus faced conflicting incentives and pressures as he assumed the presidency. The DPP “base” wanted and expected major policy changes, while the political dynamics in Taiwan during the 1990s (see Figure 17.1) seemed to be working against radical policy shifts. Furthermore, the DPP only had about a third of the seats in the Legislative Yuan, which created serious political problems for Chen. Initially, he opted for a conciliatory approach. He appointed former defense minister Tang Fei of the KMT as premier, and Tang’s cabinet had a fairly large number of non-DPP members. Chen’s approach to create what he called “a government for all people” with himself as “President for all people” did not prove stable because it was undermined by both the KMT and DPP. In the Legislative Yuan, most KMT members saw Tang as representing their enemy Chen Shui-bian, and many DPP members resented the premiership going outside their party. Thus, executive-legislative relations soon moved toward gridlock.

The DPP activists, moreover, pushed Chen to be more supportive of their agenda. Here, the focus of their efforts in the summer of 2000 was not national identity but halting the construction of the Fourth Nuclear Power Plant, in line with the DPP’s traditional environmentalism. By the end of the summer, Chen switched positions on this issue, helping to precipitate Tang’s resignation. When the new DPP premier announced the cancellation of the power plant in October 2000, the KMT majority in the Legislative Yuan declared war on the Chen administration. Initially, they threatened to impeach him, but then backed down due to popular opposition and their reluctance to face the voters (because this would also have brought the dissolution of parliament). While the crisis over the nuclear plant faded, strong hostility and nearly total gridlock between the executive and legislature ensued.35

The 2001 elections for the Legislative Yuan, therefore, became a high stakes political game for several reasons. First, it was a test of power between the PanGreen and PanBlue coalitions over who would set the direction of politics in Taiwan. Second, the two new parties, the PFP and TSU, finally had an opportunity to demonstrate whether they had significant pull at the polls. Third, Taiwanese nationalism became more of an issue as the DPP sought to mobilize its base, faced more competition from the TSU advocates of Taiwan Independence in multimember districts, and hoped to secure the defection of “localized” KMT legislators who remained loyal to Lee Teng-hui after their election. In coalition terms, the elections showed mixed results. The DPP, PFP, and TSU were all winners. The DPP outpolled the KMT and became the largest party in the Legislative Yuan with 87 seats; the PFP did quite well, winning nearly a fifth of the vote and 46 seats; and the TSU had a respectable showing with 8 percent of the votes and 13 seats. In contrast, the KMT saw its number of seats cut almost in half from 123 in 1998 to 68; and the New Party was almost obliterated, obtaining just a single seat. Overall, the PanBlue bloc retained a narrow majority of 115 seats out of 225 to 100 for the Greens and 10 for independents. Despite intense speculation, Taiwanese KMT legislators did not defect to the Greens after the election, and Chen’s attempt to form some type of coalition government went nowhere. Indeed, the new TSU legislators put pressure on the DPP to take a more aggressive position on national identity. For example, they tried to pass legislation mandating that the president be born on Taiwan, which seemed aimed at raising nationalist resentments toward such PanBlue leaders as Lien, Soong, and Ma.36

The administration used its executive power to promote what it called a “Taiwanese subjectivity” that certainly was aimed at its base constituency. Wei-chin Lee, for example, argues that Chen promoted a “cultural revolution” (reference to Mao’s Cultural Revolution intentional) that included such initiatives as changing the name of many agencies and organizations to stress “Taiwan,” promoting Taiwanese in language policy, revising the official policy toward the mass media to reverse the previous KMT domination of outlets (including the encouragement of underground radio stations), and changing the focus from Chinese to Taiwanese history in education policy.37 Daniel Lynch termed this a “self-conscious nation-building project,” indicating that Chen and the PanGreen bloc were trying to create a new nation rooted in Taiwanese history and culture.38

The changed nature of the party system also promoted the rise of symbolic politics focusing on national identity. During the 1990s, as shown in Figure 17.1 above, the major parties (i.e., the KMT and DPP) had moved toward the middle, while the extremes were represented by fairly inconsequential parties (i.e., the Taiwan Independence Party and the New Party). With the fracturing of this primarily two-party system in the 2000 presidential election, parties with more extremist images became much more powerful in Taiwan politics. James Soong’s People’s First Party attracted KMT Mainlanders and others who had opposed Lee Teng-hui, as well as absorbed much of the New Party. Thus, despite Soong’s proclaimed allegiance to a “New Taiwanese” identity, it became identified as pro-Mainlander and pro-China in the minds of many Taiwanese. Conversely, the Taiwan Solidarity Union strongly supported Taiwan Independence and often chided Chen and the DPP for not being aggressive enough in this area.39 Consequently, these more powerful minor parties were able to put the national identity question much more centrally on Taiwan’s political agenda.

Chen Shui-bian’s appeals to Taiwanese nationalism intensified as preparations for the 2004 presidential election commenced. Jacques deLisle termed it the “Taiwan Yes!; (China No!)” campaign after one of its central themes and slogans.40 Part of the reason for this strong dose of Taiwanese nationalism almost certainly came from the fact that Chen clearly trailed in the polls by ten percentage points or more as the campaign got started in earnest in the fall of 2003.41 Candidates who are behind need to be aggressive and to “shake up the pot” in the hope of changing the dynamics of the election. Given the centrality of national identity and cross-Strait relations in Taiwan politics, there were few (if any) alternative issues to ride.42 Moreover, DPP campaigns have traditionally emphasized mobilizing supporters in large campaign rallies,43 and the emotionally laden national identity issue is clearly the best way to generate such enthusiasm and support among the PanGreen “base.” Thus, Chen and his Green bloc evidently made the calculation that they would get more votes by appealing to their committed constituency rather than to the “moderate middle.”

One important explicit appeal to Taiwanese nationalism was Chen’s plan to hold a referendum on policy toward China simultaneously with the presidential election, although support for referendum turned out to be considerably broader than just a reflection of Taiwanese nationalism. The DPP had initially advocated a referendum for declaring Taiwan Independence in the early 1990s. Thus, the idea of adopting legislation to allow referendum and of holding referendum strongly appeals to the DPP “base,” raises consternation in Beijing, and is viewed with some suspicion in Washington as potentially destabilizing cross-Strait relations. Referenda, of course, can be held on many issues that have nothing to do with Taiwan Independence and the island’s status and sovereignty (e.g., a township referendum that was held on whether it should get a freeway exit). Indeed, when Chen began to push for a referendum law in 2003 with the goal of holding a referendum simultaneously with the presidential election, he took more than a little care to choose issues that did not involve a direct change in Taiwan’s status or declaration of Independence (e.g., whether Taiwan should be granted membership in the World Health Organization [WHO], which appealed to the presumably large majority of citizens who were frustrated and angered over the PRC’s ability to deny Taiwan status and “face” in international affairs). As Shelley Rigger argues, this certainly appeared to have been politically motivated in terms of the upcoming election:

The theory is that referendums, especially symbolic ones like that on the WHO, will help the DPP politically by mobilizing the party base and perhaps even exciting patriotic emotions that will draw votes beyond the DPP’s traditional supporters. Holding the referendum together with the presidential election would allow enthusiasm for the referendum to spill over into the presidential race.44

Chen Shui-bian’s advocacy of a referendum turned out to have two quite distinct and separate appeals. It certainly appealed to supporters of Taiwan Independence among the PanGreen forces.45 It also had wide support among the general public who rejected Independence as too radical and provocative, presumably because referenda were seen as a way of surmounting the ongoing gridlock in Taiwan’s politics. Consequently, the politics of the referendum issue during 2003–4 turned out to be quite convoluted. The legislative enactment involved a three-sided struggle among Chen, more radical PanGreen advocates of using the referendum to achieve Taiwan Independence, and the narrow PanBlue majority in the Legislative Yuan who initially opposed passing a referendum law but came to support the idea when its strong popular support became apparent. Ironically, Chen ultimately used a referendum law that was passed by the reluctant PanBlue forces to hold referenda on two issues—whether Taiwan should build up its military in the face of the growing threat from China and whether Taiwan should negotiate with China (the subjects of the referenda that Chen proposed changed considerably over time). On election day, a PanBlue boycott resulted in only 45 percent of the electorate voting for them (as opposed to the 80 percent who voted in the presidential race), causing them to fail despite overwhelming support of the votes cast because they obviously could not get the 50 percent of the registered voters necessary for passage.46

The same logic applied to Chen Shui-bian’s campaign promise to promote major constitutional change and revision, which he initiated with a sudden announcement at the anniversary of the founding of the DPP in September 2003 that he planned to have major constitutional change finished by 2006.47 On the one hand, DPP factions and members have long advocated the need for a new Constitution to achieve, in essence, Taiwan Independence by, for example, renaming the country the Republic of Taiwan; and Lee Teng-hui and the Taiwan Solidarity Union strongly advocated a new Constitution for a new nation. On the other hand, the need for constitutional change and reform in Taiwan is very widely acknowledged as well. Consequently, just as with the referendum issue, Chen’s advocacy of constitutional reform appealed both to the PanGreen base (while raising fears in Beijing and, to a lesser extent, Washington) and to the “moderate middle” of the citizenry as well, framing the issue in a way that probably benefited Chen at the polls.

The high point of the PanGreen campaign was the “2-2-8 Hand-in-Hand” rally, which was held “to protest China’s military threats and to give the world a clear message that the people of Taiwan want peace, not war.” The rally involved a human chain of an estimated two million people that stretched from the north to the south of Taiwan, with Chen Shui-bian and Lee Teng-hui clasping each other’s hands in Miaoli County in the middle. The huge turnout certainly proved the rally to be a tremendous success in igniting PanGreen supporters. It also was highly symbolic. It was held at 2:28 p.m. on February 28, thereby commemorating the tragedy of “2-2-8.” In addition, it was modeled on a 1989 human chain in what were then the Baltic Republics of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania of the Soviet Union, protesting the Soviet occupation of what are now three independent nations. The implicit calls for “ethnic justice” internally and Independence from China externally were far from subtle. This certainly reinforced perceptions that Chen was using Taiwanese nationalism as the driving force in his campaign and was willing to “push the envelope” on the Independence issue.48

The results of the 2004 presidential race were quite dramatic as Chen won re-election by the razor-thin margin of 50.1 percent to 49.9 percent against the Lien-Soong ticket, helped to victory almost certainly by a failed assassination attempt against himself and his vice-president on election eve which created a significant jump in support for the Green ticket in tracking polls.49 This certainly validated his campaign strategy of emphasizing “cultural symbolic politics.” Not only did Chen win re-election, but public opinion on national identity and cross-Strait relations was seemingly redefined to become considerably closer to the PanGreen position. Support for this conclusion did not just come from those sympathetic to Chen and Lee Teng-hui. Rather, it was strongly validated by the actions and words of the PanBlue leadership. For example, during their final massive campaign rallies both Lien Chan and James Soong kissed the ground in Taipei and Taichung, respectively, to demonstrate their devotion and loyalty to Taiwan; and Lien Chan was quoted as saying, “There is one state on each side of the Taiwan Strait,” thereby echoing what was seen as a highly provocative argument by Chen Shui-bian just two years before.50

While there were some calls for moderation and reconciliation with the PRC after the election,51 the run-up to the elections for the Legislative Yuan in December again spurred Chen and the Green bloc to stress Taiwanese nationalism in their campaigns.52 In addition to replicating his strategy in the presidential campaign, Chen came under pressure because of competition that DPP candidates faced from TSU rivals in multimember districts who advocated Taiwan Independence.53 The outcome of the election raised questions about this strategy. The PanGreen coalition was widely expected to gain a majority in the Legislative Yuan. However, the Blue bloc retained its narrow majority by winning 114 of the 225 seats. Domestically, the electoral defeat of the Greens was widely attributed to the radicalism of their campaign.54 Thus, Chen appeared to fall victim to his own “base constituency.”

In response to this electoral setback, Chen took the polar opposite policy tack of appealing to his “base constituency” by, at least according to very public rumors, beginning to flirt with James Soong and the People’s First Party, who were detested by many Taiwanese nationalists for their allegedly pro-Unification and decidedly anti-Independence positions, in an attempt to take advantage of continuing personal strains between Soong and KMT chairman Lien Chan.55 Moreover, the new DPP premier Frank Hsieh offered the vice premiership to KMT vice chairman Chiang Pin-kung in a move that at least started some cross-party discussions.56 This stratagem proved to be extremely short-lived. The potential DPP-PFP coalition quickly foundered when the various PanBlue leaders sought to take advantage of an opening to China in the spring of 2005.57 More fundamentally, Chen Shui-bian evidently concluded that the Green loss in the December 2005 elections was the result of the alienation of his base. Consequently, unlike in the previous elections, he became more aggressive toward China after the election (see the next part of this chapter on “Cross-Strait Relations”). One of his national policy advisors, Chin Heng-wei, explained President Chen’s new policy toward the PRC. Chin said that the DPP suffered a major setback in last December’s elections because it lost many of its “core supporters” by trying to court middle-of-the-road voters. “The core supporters ended up not voting because they thought that Chen was not being loyal to them and they wanted to teach the party a lesson,” Chin claimed.58

Ever since the evacuation of Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang to Taiwan after they lost the Chinese Civil War to the Communist Party of Mao Zedong in 1949, Taiwan and China have had mutually conflicting and incompatible views on sovereignty, although the nature of this conflict changed dramatically at the beginning of the 1990s. From 1949 until 1991, Beijing and Taipei both claimed to be the legitimate government of all China that included Taiwan (and Mongolia). In 1991, Taiwan under Lee Teng-hui’s leadership redefined this situation by constitutionally abrogating the “Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Mobilization for Suppressing the Communist Rebellion.” Consequently, Lee gave up Taipei’s claim to rule the Mainland but also created a potentially stronger challenge to the PRC’s sovereignty claim to Taiwan with the implication that if the ROC did not possess or exercise sovereignty over Mainland China neither did Beijing possess or exercise sovereignty over Taiwan (see Chapter 16 by Murray Rubinstein).

As Table 17.4 demonstrates, these competing sovereignty claims have differed considerably over time in how much hostility they generated in cross-Strait relations. From the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949 until about 1980, the relations between the ROC and PRC were marked by unremitting hostility. A significant change occurred within this period in the early 1960s. During the 1950s, both sides still seemingly hoped that their legitimacy claims could be exerted through the force of arms, as indicated by the 1954–55 and 1958 Taiwan Strait Crises. By the 1960s, both Mao and Chiang evidently realized the futility of such dreams and became willing to put off the final determination of their sovereignty claims for the indefinite future. By the early 1980s, a hesitant rapprochement emerged as the two regimes appeared to be at least tacitly willing to “live and let live.” Initially in this period, China pursued a “peace offensive” by trying to get Taiwan to agree to Deng Xiaoping’s idea of Unification through “one country, two systems,” while Taiwan adamantly rejected any negotiations because of its much weaker bargaining position. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Taiwan initiated its “pragmatic diplomacy,” which tried to balance a push to upgrade its international status with some contacts with China (e.g., the Koo-Wang talks of 1993) and especially with the tremendous growth of economic and social interactions across the Strait. For most of the first half of the 1990s, this policy appeared to be working.59

However, increasing Chinese frustration over Taiwan’s “creeping officiality” in international affairs finally exploded after the United States gave President Lee Teng-hui permission to visit his alma mater, Cornell University, in the summer of 1995, setting off another period of growing tensions labeled the new battle over sovereignty, which, as noted in Table 17.4, has been renewed and intensified every few years since then. This last period can be conceptualized as a growing tension not only for Taiwan, but for China as well, between the benefits of the stable but far from desirable status quo and the dangers that pursuing the desired state of sovereignty would almost inevitably unleash. This part of the chapter analyzes this tension. The first section provides a theoretical overview explaining the political dynamics in cross-Strait relations; and two subsequent sections discuss Lee’s and Chen’s policies in this area.

Periods In Cross-Strait Relations

Era |

Approximate Time |

Policies |

|

I. |

Unremitting Hostility |

Both Beijing & Taipei claim to be sole government for all China |

|

A. Potentially Hot War |

1949–1962 |

Significant threat of war until early 1960s |

|

B. Cold War |

1963–1980 |

||

| II. | Hesitant Reapprochement |

Both seemingly willing to accept the other for indefinite future |

|

A. China’s “Peace Offensive” |

1980–1988 |

Taiwan’s “3 Nos” in face of China’s much stronger position |

|

B. Mutual Accommodation |

1989–1995 |

Taiwan’s “pragmatic diplomacy” balances reasserting diplomatic status with greater contacts with China |

|

| III. | The New Battle Over Sovereignty |

||

A. China’s Failed Intimidation |

1995–1996 |

Retaliation against President Lee’s visit to US fails to affect 1995 presidential election in Taiwan |

|

B. Cold Peace |

1996–1999 |

Return to normalcy, but greater hostility between top leaders |

|

C. Challenge & Counter-Challenge |

1999–2004 |

Both sides more assertive about conflicting sovereignty claims |

|

1. Lee’s “Special State-to-State Relations” |

1999 |

||

2. Beijing’s demand Taiwan accept “One China” |

2000 |

||

3. Chen’s “One Country on Each Side of Strait” |

2002 |

||

4. PRC Anti-Secession Law |

2005 |

||

5. Chen’s New Year speeches |

2006 |

||

Foreign policy is often likened to a game of chess in which national leaders seek to pursue their country’s national interest as defined by fairly immutable and abstract criteria.60 Other analysts argue that foreign policy is much more complex and subject to very substantial pushes and pulls from ongoing domestic politics that may be only indirectly tied to the foreign policy objectives that seem to be at stake in the “great game” of international diplomacy. In this vein, Robert Putnam conceptualizes foreign policy as a “two-level game” in the sense that events at both the domestic and international levels influence each other.61 For example, both the Lee and Chen governments in Taiwan and the communist regime in China have used nationalism to gain popular support and legitimacy.62 Domestic politics, therefore, forced both to be more confrontational in cross-Strait relations than they might otherwise be just to keep “face” before domestic audiences and constituencies. The potential for conflict was further multiplied by the highly emotional and symbolic nature of the issues involved.

Interactions of Different “Levels” in Affecting Cross-Strait Relations

Event |

Domestic politics from “below” |

National governments |

Pressures from “above” in international system |

Taiwan Strait crises of 1950s |

Little, if any, in authoritarian Taiwan and China |

Both ROC and PRC try to establish sovereignty claims by force of arms |

Both the United States and USSR seek to restrain client states, leading them to accept status quo of divided China |

PRC replaces ROC at UN in 1971 |

KMT may have feared implications of the ‘Two Chinas” compromise for domestic legitimacy |

Both ROC and PRC seek to be sole UN representative |

The United States is willing to save a UN membership for ROC, but Chiang Kai-shek rejects this effort |

Taiwan’s pragmatic diplomacy and renunciation of sovereignty over Mainland China |

Democratization shows strong support for upgrading Taiwan’s international status |

Taiwan seeks more protection for its sovereignty; PRC fears precedent being set for Taiwan Independence |

Little, if any, involvement by the United States or other nations |

Growing economic integration between Taiwan and China during the 1990s |

Domestic constituencies created in both countries who favor peaceful cross-Strait relations; in particular, Islander business people in Taiwan benefit from economic ties |

Beijing welcomes Taiwan being drawn into China’s orbit, but also constrained by its own dependence on global markets; Taipei becomes concerned about growing dependence on China |

Changing national roles in global economy stimulate large movement of industry from Taiwan to China |

This concept of a “two-level game” (if expanded to a three-level game to include the pressures emanating from “above” as well as from “below” the national governments) can be applied to explain the changing nature of cross-Strait relations outlined in Table 17.4 above. Table 17.5, for instance, provides an illustration of how a multilevel “game” was involved in four key events that shaped the current state of cross-Strait relations. First, pressure from their superpower patrons forced Chiang and Mao to rein in their military confrontation of the 1950s and, in effect, accept a stable status quo that neither found acceptable. Second, fear of the implications for its domestic legitimacy myth undoubtedly provides at least part of the explanation for why the Kuomintang regime acquiesced in the ROC’s expulsion from the United Nations in 1971 when it was replaced by the PRC. Third, growing popular pressures in Taiwan in the late 1980s almost certainly helped stimulate Lee Teng-hui’s “pragmatic diplomacy” which aimed at reducing Taiwan’s international isolation ensuing from its withdrawal from the United Nations. This included Taiwan’s decision to end its claims of sovereignty over China in 1991, which was certainly portentous in its implied claim that China did not exercise sovereignty over Taiwan. Finally, the ongoing effects of globalization or changes in the international economy stimulated growing economic integration between Taiwan and China during the 1990s, which set off a complex chain of political effects in both countries.

Initially, both sides were quite willing to continue the Chinese Civil War of the late 1940s; and, as the leaders of authoritarian regimes, neither Chiang Kai-shek nor Mao Zedong had to pay much, if any, attention to domestic political pressure. Both, however, were constrained by the need to maintain the military support of their superpower patrons, the United States for Taiwan and the Soviet Union for China. Both could only vanquish the other with the strong support and military resources of their respective patrons, while the two superpowers displayed considerable reluctance to let their client states pull them into a major conflict that could have turned into World War HI. The two Taiwan Strait Crises of the 1950s showed that superpower support for both Taiwan and China was more limited than Chiang and Mao demanded, pushing the two to de-escalate their military confrontation.63 In effect, the limited support that was forthcoming from their superpower patrons forced both sides to accept the stability of an undesirable status quo of a separate China and Taiwan, rather than pursuing their goal of a unified China under their own rule.

From the early 1960s on, Taiwan and China channeled their conflict into competition for diplomatic recognition and international support. Initially, Taiwan with the support of the United States and most of the West held a substantial advantage. During the 1960s, though, the PRC gained more support, particularly from new ex-colonial nations. The tipping point was probably the PRC’s replacement of the ROC for the “China seat” in the United Nations in 1971; during the 1970s even most of Taiwan’s closest “friends,” such as the United States and Japan, switched their formal diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing as well. The United States was willing to save a membership for Taiwan in the United Nations, although China would have gained the coveted seat in the Security Council, and U.S. diplomats felt that such an effort would have been successful.64

Yet, the Chiang Kai-shek government refused to entertain such a proposal, claiming that it violated its “One China” principle. This then put Taiwan at a very substantial disadvantage in its diplomatic competition with China, especially because membership in most international organizations is based on UN affiliation.65 From this perspective, Chiang’s decision to leave the United Nations appears both momentous and quite unfortunate. One explanation, besides a gross miscalculation on Chiang’s part, reverses the normal linkage between domestic and foreign policy in which domestic groups pressure the government to adopt policies that they advocate. Here, rather, the government may have feared that the separate representation of Taiwan in the United Nations might undercut its own legitimacy and authority by raising the question of why the people of Taiwan themselves should not determine their own political course.

As described in much more detail in Murray Rubinstein’s chapter “Political Taiwanization and Pragmatic Diplomacy,” Lee Teng-hui sought to break out of Taiwan’s at least partially imposed diplomatic isolation in the late 1980s and early 1990s with his initiative in “pragmatic diplomacy,” which clearly responded to growing popular pressures in democratizing Taiwan or reduce the country’s humiliations on the international stage. Lee sought to upgrade Taiwan’s international status with an emphasis on expanding informal contacts and activities and gaining participation in international organizations. Moreover, Taiwan’s renunciation of its sovereignty claims over China could be viewed as setting the precedent for an analogous rejection of China’s sovereignty claims over Taiwan. Lee’s success was indicated by growing Chinese complaints about Taiwan’s “creeping officiality.” Yet, at least through the early 1990s, Lee and Taiwan maintained a “delicate balance” between pursuing enhanced international support and engaging Beijing by increased contacts across the Taiwan Strait and creating an institutional framework to negotiate Unification sometime in the indefinite future. David Lampton, for one, concluded that this constituted a conscious and sophisticated policy:

I believe that the Taiwanese government is using the increased cultural, economic, and political interaction in “Greater China” (particularly between Taiwan and the mainland) to create a web of positive incentives for, and constraints on, Beijing that will induce the PRC to accept Taiwan’s drive for more international breathing space, identity, dignity, and autonomy.… This obviously is a sophisticated strategy in which one reassures Beijing of presumed long-term intentions to reunify at the same time one reassures the Taiwan populace that this is not going to happen in any foreseeable future.66

Lee’s ability to maintain a “delicate balance” in Taiwan’s relations with China was first supported and then challenged by the explosion of economic interactions across the Taiwan Strait. This occurred because of the fortuitous confluence of Taiwan’s decision to allow indirect trade and investment with the Mainland in the late 1980s and the push for globalization in both Taiwan and China during the 1990s. Taiwan’s growing prosperity forced it out of low-wage export industries that had been the core of its “economic miracle.” In contrast, in the late 1980s China decided to pursue export-led growth itself. Consequently, many Taiwanese entrepreneurs moved their operations across the Taiwan Strait because of geographic proximity and cultural familiarity, stimulating the massive export of advanced components from Taiwan to China for final assembly. By the turn of the twenty-first century, close to a quarter of Taiwan’s exports were going to China, and Taiwanese investment in China was approaching $100 billion, creating an increasingly integrated economy across the Taiwan Strait.67

This growing economic integration reverberated back through the politics of both Taiwan and China. At first, it appeared to be a “win-win” situation. At the level of the two national governments (see the third column, bottom row of Table 17.5), Beijing was pleased that Taiwan was being pulled into China’s orbit, while Taipei was pleased that these growing economic interactions placated China in regard to Taiwan’s more activist foreign policy. At the level of domestic politics (see the second column of Table 17.5), constituencies were formed in both countries which reaped large gains from the growing economic integration (e.g., the political leaders in southern coastal China whose regions’ economies were stimulated by Taiwanese investment) and which would push their national governments to maintain harmony in cross-Strait relations. In particular, Islander businesspeople from Taiwan were very prominent in this migration of capital, thereby ameliorating the normal divide in Taiwan politics between pro-China Mainlanders and anti-China Islanders. Consequently, these growing social and cultural ties across the Taiwan Strait were seen as a force that could dampen the growing conflict between Taipei and Beijing that commenced in the mid-1990s.68

Conversely, this growing economic integration ultimately began to constrain the policy options of both countries in ways that their governments considered much less of a “win-win” situation. For Taiwan, the Lee government became increasingly concerned about the asymmetric nature of the economic links between Taiwan and China that resulted from their involving a much larger share of the island’s economy than the Mainland’s. Such dependence, Lee feared, would give China the power to exercise undue economic and political leverage over Taiwan. Yet, this advantage came with some strings attached for China as well. China had clearly linked its development fate to its rapidly expanding participation in the global economy. Thus, its ability to harass Taiwan had become limited politically by the possibility that it could make itself a pariah to the international community with unilateral military action.

As Lee Teng-hui prepared his campaign for Taiwan’s first direct election for president in early 1995, he appeared to have achieved success in domestic politics, economic performance, and foreign (especially cross-Strait) relations in what Table 17.1 termed the “Three Triumphs.” Yet, the delicate balance that undergirded his pragmatic diplomacy was about to unravel, thereby threatening Taiwan’s domestic politics and economy as well. This resulted from changing perceptions in both Beijing and Taipei that made the outbreak of contention and conflict almost inevitable for two distinct reasons. Both Taiwan and China could take fairly optimistic perspectives on cross-Strait relations during the first half of the 1990s because they evidently believed that time was on their side, in the sense that existing political and economic trends were working in their favor. Beijing thought that growing economic and social ties across the Strait would gradually undercut Taiwan’s separation from the Mainland, while Taipei saw its separate international status being established and consolidated. By 1995, however, both began to fear that the other’s positive assessments were coming true. Taiwan became increasingly worried that China was successfully limiting pragmatic diplomacy and making the island dependent on the mainland, while China worried that Taiwan was on the verge of establishing Taiwan Independence.

This flip-flop from optimism to pessimism at the governmental level was exacerbated by domestic politics where pressure was growing on the two governments to act more aggressively toward the other, helping to turn the détente of the early 1990s into confrontation in the mid- and late 1990s. In Taiwan, the general population became increasingly restive over their lack of diplomatic status or “face.” For example, the DPP’s advocacy of trying to regain membership in the United Nations proved to be quite popular and was ultimately adopted by Lee Teng-hui once he had consolidated control of the Kuomintang. Domestic factors in the PRC were making Beijing less flexible and less willing to compromise on Lee’s “pragmatic diplomacy.” There was a growing “new nationalism” between the public and the government who increasingly saw Taiwan as representing the last major symbol of national humiliation from nineteenth century Western and Japanese imperialism whose reunification was essential for China’s “face”; and the military was increasingly critical of Jiang Zemin for his soft policy toward Taiwan.69

Matters came to a head when the objectives of the two governments directly clashed in 1995 and pulled the United States into their dispute. President Lee had become increasingly frustrated when his initiative to gain some type of association with the United Nations went nowhere in the mid-1990s because of Beijing’s strident opposition. The central objective of Taiwan’s pragmatic diplomacy then turned to arranging an “unofficial visit” for Lee to the United States; and this became even more important to Lee in 1995 as he began to consider his presidential campaign. In sharp contrast, the PRC strongly objected to any Lee visit to the United States, claiming that this could be construed as recognition of an independent Taiwan by America. Reportedly, Beijing was particularly worried that Lee would go to the United States after his direct election and claim a democratic mandate to govern a sovereign nation. Initially in early 1995, the Clinton administration assured Beijing that Lee would not be granted a visa. However, after Congress passed a nearly unanimous resolution supporting his visit, Clinton changed his mind and granted permission for Lee to attend a reunion at Cornell University in June 1995.