9 • The Post-Classic Period: Rival States

Of all peoples of Mexico, the Zapotecs were among the most fortunate, for they had long been undisturbed in their beautiful valley by troublemakers from outside. This state of affairs was ended, however, when Monte Albán was abandoned at the end of the eighth century AD and a new force was spearheaded by a people infiltrating the Valley of Oaxaca from the mountainous country lying to the northwest. But more of this later.

In the early Post-Classic, a new center of Zapotec civilization sprang up at Mitla, about 25 miles (40 km) southwest of Oaxaca City. The name is derived from the Nahuatl Mictlan, or “Land of the Dead,” but to the Zapotecs it was known as Lyobaá, “Place of Rest.” Not very much is known of the archaeology of Mitla, but it is thought to have been constructed in the Monte Albán V period, corresponding to the Toltec and Aztec eras; it was still in use when the Spaniards arrived.

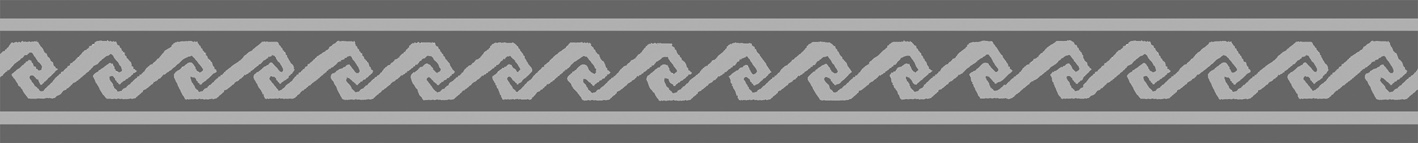

Mitla is one of the architectural wonders of ancient Mexico – not grandiose, not a mighty city it is true, but of unparalleled beauty. Five architectural groups are scattered over the site, three of which are Post-Classic palaces, while the remaining two are Classic-period temple precincts, reused in the Post-Classic. During this latter period the ensemble was guarded by a fortified stronghold on a nearby hill. A Colonial church is built into one of the palaces and during fiestas native Zapotec ceremonies are still carried out within its precincts, side by side with Christian rites. Most remarkable among these complexes is the Group of the Columns, comprising very long masonry halls arranged on platforms around the four sides of a plaza. Here and elsewhere at Mitla long panels and entire walls are covered with geometric stonework mosaics, the intricate arabesques of which are almost entirely based on the step-and-fret motif, each piece of veneer being set into a red stucco background. From the descriptions handed down from the Colonial period, it is known that the spacious rooms of the palaces had flat roofs supported by huge horizontal beams of wood.

136 North facade of the Building of the Columns, Mitla, Oaxaca. Late Post-Classic period. Overall height about 26 ft (8 m).

137 Portion of inner chamber in Palace II, Mitla, Oaxaca. Late Post-Classic period.

If we can believe the somewhat sensational but highly detailed account of pre-Spanish Mitla given us by Father Burgoa, who visited the district in the seventeenth century, this was once the residence of the High Priest (Vuijatao, or “Great Seer”) of the Zapotec nation, a man so powerful that even the king bowed to his commands. Mitla’s groups of buildings were apparently precincts, one for the holy man himself; one for secondary priests; one for the Zapotec king and his court when on a visit; and one for the officials and military officers of the king. Priests carried out the ceremonies garbed in white robes and figured chasubles, amid clouds of perfumed copal incense. Hidden from vulgar eyes in an inner chamber of his palace, the High Priest ruled from a throne covered by a jaguar skin; even the king, when in his presence, took a lesser seat. Kept scrupulously clean and covered by mats, the floors were the place of repose for all occupants at night.

Burgoa asserts that gruesome sacrifices took place there continuously: numberless captives had their hearts torn out and offered to the High Priest and the Zapotec gods. Somewhere underneath Mitla was supposed to be a great secret chamber where the Zapotec kings and nobles, as well as heroes killed on the battlefront, were interred, accounting for the name of the site. The exact location of this catacomb is not known, but according to Burgoa the passage leading to it was found in his day and entered by some enterprising Spanish priests, who were soon forced by the horror of the place to scurry out again and seal it up as an abomination against God.

“A succession of very small, rather prosperous valleys surrounded by large areas of nearby desert” is how Ignacio Bernal once characterized the homeland of the Mixtec people. This is the rugged, mountainous land in western and northern Oaxaca called the Mixteca. Archaeological survey carried out by Ronald Spores of Vanderbilt University has shown that initially, during the Classic, Mixtec settlements were located on hilltops; but by the outset of the Post-Classic, they had moved down into the valleys, where (as John Pohl and Bruce Byland have demonstrated) they were organized into multiple kingdoms or polities, with no large-scale political integration and no large cities. Each kingdom was under the domination of one independent lord. Since arable land was scarce in this precipitous landscape, there was fierce competition for it along the borders between kingdoms, and warfare was endemic.

Miraculously, there have survived four pre-Conquest codices which, through the researches of Alfonso Caso, have carried Mixtec history back to a time beyond the range of any of the annals of other Mexican, non-Maya peoples. Analysis of this material by Emily Rabin has established that it covers a 600-year time span beginning about AD 940. These codices are folding, deerskin books in which the pages are coated with gesso and painted; they were produced late in the Post-Classic for the Mixtec nobility. As Jill Furst notes, “they are concerned with historical events and genealogies, and present records of births, marriages, offspring, and sometimes the deaths of native rulers, and their conflicts to retain their lands and wars to extend their domains.” The one exception is the front, or obverse, of the Vienna Codex, which she has found to be a land document that begins in the mythical “first time” (when the ancestral Mixtecs sprang from a tree at a place called Apoala), and establishes the rights of certain lineages to rule specific sites through the approval and sanction of the gods and sacred ancestors.

The reader is taken through these largely pictorial texts by means of red guidelines (generally horizontal), but there is no standard layout for the entire codex: some texts proceed from right to left, and some from left to right. Dates are given only in the 52-year Calendar Round; the year itself is given with a sign that looks like an interlaced A and O, accompanied by the Year Bearer (i.e. 12 Reed, 7 House, and the like), followed by the day in the 260-day count. There is no attempt at portraiture, and there was no need for it, for each personage in the histories is indicated by his or her birthdate in the 260-day count, plus an iconic “nickname,” so there is little ambiguity. Each individual received further specificity through detailed renderings of costume, which for the Mixtecs often identified precise offices or ceremonies.

Compared with the Maya script and the Zapotec writing system from which it may have sprung, Mixtec writing was fairly rudimentary. This was a deliberate strategy used to communicate beyond the Mixtec language area. Neighboring peoples such as the Chocho, Zapotecs, and Nahua could understand this simple writing system without mastering the spoken language. In addition, a great deal of information was encoded in the images that inevitably accompanied the writing. Here the emphasis was on rather schematic human figures with clearly delineated costume and jewelry that spoke to the figure’s identity and station. Although the art style is often referred to as “Mixtec” or “Mixteca-Puebla”, its origins are still hotly debated. It is certain that variations on this style could be found across ancient Mexico and much of the Maya area by the fourteenth century, allowing elites from those areas to share information effectively across a large portion of Mesoamerica. This style and symbol system achieved an even wider distribution than the earlier Toltec system.

That the Mixtecs managed to bring under their sway not only all of the Mixteca proper but also most of Zapotec territory by Post-Classic times is a tribute to their statecraft. Incorporating a territory could involve military conquests, strategic marriages, or both. Since there were several powerful lords ruling in the Mixteca at any one time, expansionist policies could spark profound internecine strife. To counter this, the Mixtec nobility shared an adherence to certain oracular shrines as well as other cult practices that served to cement their relationships. By the time the Spanish arrived, the Mixtec nobility was so thoroughly intertwined that all could claim descent from a handful of common ancestors whose exploits, often centered around the shrines and cult practices that bound the Mixtec elite, made up a heroic saga known throughout the region.

The heroic sagas come down to us by way of the four pre-Conquest codices mentioned above. These relate that by the beginning of the Post-Classic period, the leading power in the Mixteca was a town called Hill of the Wasp, a Classic-period hilltop settlement in the southern Nochixtlan Valley, where it is still referred to today by its codiacal name in Mixtec, Yucu Yoco. When it was overthrown in the late tenth century, its rulers were sacrificed, and an epic cycle of conflict referred to as the “War Of Heaven” commenced. According to the codices, three Mixtec factions fought for sixteen years, eventually founding the Mixtec political landscape of the Post-Classic period. Scenes of these battles in the codices are highly schematized, with capture indicated by grasping the hair, and defeat by the burning of mummy bundles. The bundles were very important to the Mixtec, for it was through access to the divine ancestors in the form of bundles that family tradition and prestige were upheld. Supernaturals like the Mixtec culture hero 9 Wind also played an important role in the indigenous account, giving the results a divine sanction. The War of Heaven ends with the establishment of the first dynasty of Tilantongo (its Mixtec name means “Black Town”); this jointly ruled several valleys with a place called Xipe Bundle, until it too fell.

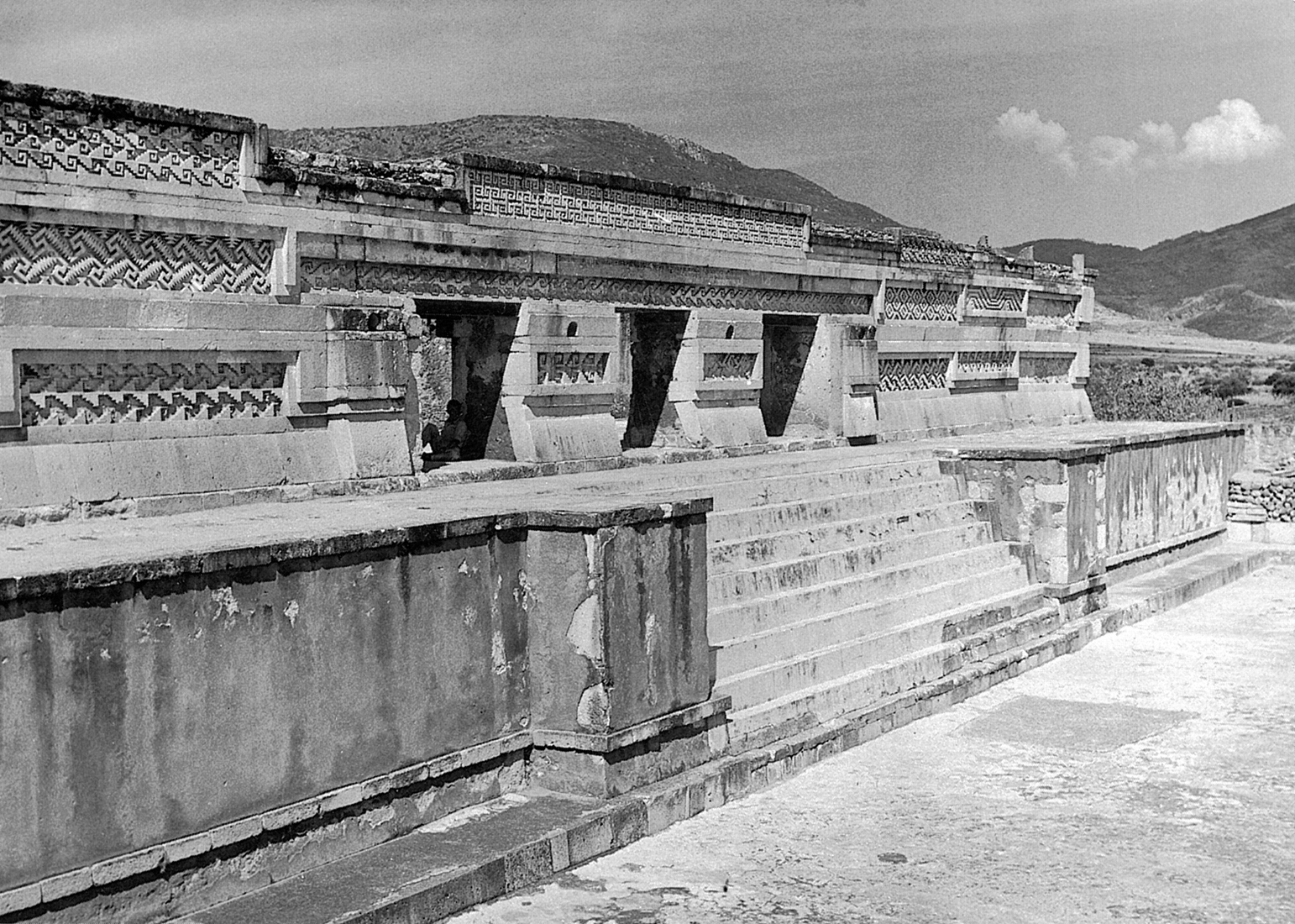

In the second dynasty of Tilantongo, the codices have much to tell about a great warlord named 8 Deer “Jaguar Claw,” who lived during the Calendar Round which began in AD 1063 and ended in 1115. When he rose to power, he attacked a town known as Red and White Bundle, located to the east of Tilantongo, sacrificing both the lord of that place and (somewhat unchivalrously) his wife Lady 6 Monkey, who had been a princess of Mountain of the Place of Sand. In 1097, 8 Deer “Jaguar Claw” seems to have made a journey to Tollan (a place of the rushes, or place of legitimacy), where he was invested with the Toltec nose button under the auspices of the Toltec king himself, a man called 4 Jaguar; this probably marks his accession to the throne of Tilantongo, the ruler of the Toltec capital fulfilling the same function as the pope who crowned the Holy Roman Emperor.

We follow in the books the machinations of 8 Deer “Jaguar Claw,” as he tries to bring rival statelets under his sway: marrying no fewer than five times, all his wives were princesses of other towns, some of whose families he had subjected to the sacrificial knife (or had shot with darts while strapped to a scaffold, another Mixtec way of dispatching captives). “Who lives by the sword dies by the sword” goes the European saying, and this formidable warrior was ultimately killed by Lady 6 Monkey’s son. This latter personage became ruler of a town called Place of Flints, and married the daughter of 8 Deer “Jaguar Claw” himself! 8 Deer’s exploits were so fundamental to Mixtec history that they still served to legitimize claims for several Mixtec royal houses when the Spanish arrived, 400 years later.

138 Scenes from the life of the Mixtec king, 8 Deer, from the Codex Nuttall. Right, 8 Deer has his nose pierced for a special ornament in the year AD 1045. Center, 8 Deer goes to war. Left, town “Curassow Hill” conquered by 8 Deer.

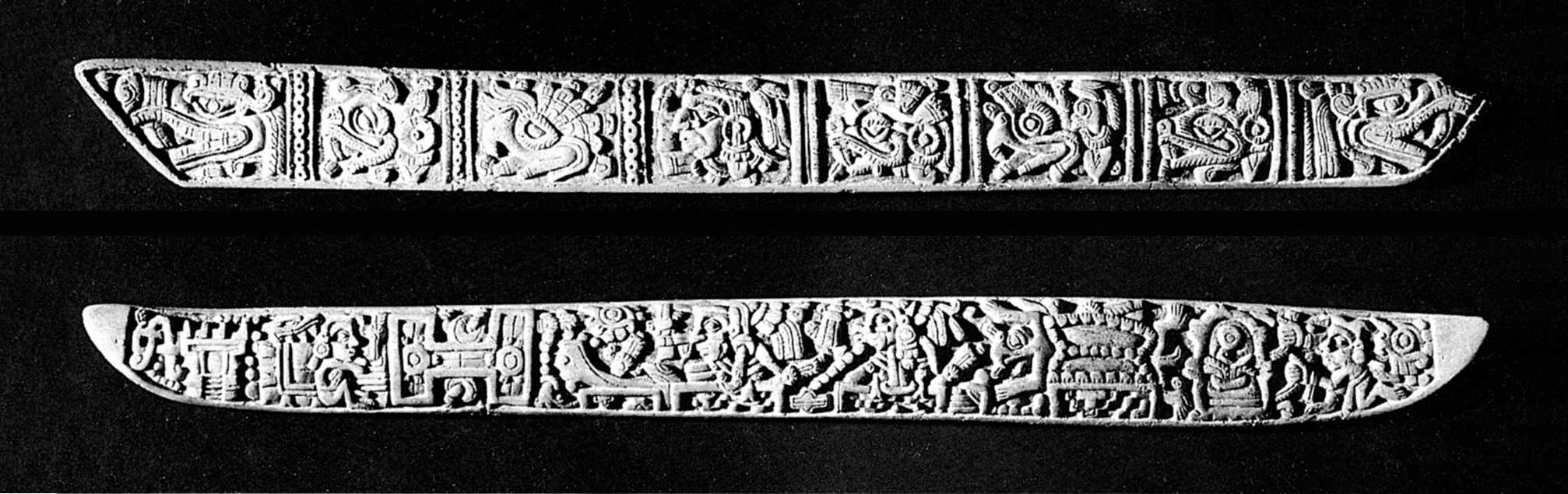

By approximately AD 1350 the Mixtecs began to infiltrate even the Valley of Oaxaca by the usual method of state marriage, Mixtec royal brides insisting on bringing their own retinues to the Zapotec court. By the time the Spaniards arrived, practically all Zapotec sites were occupied by the Mixtecs. Of their great wealth and high artistry – for they were the finest goldsmiths and workers in turquoise mosaic in Mexico – the fantastic treasure from Tomb 7 at Monte Albán is eloquent testimony. Here, in a Classic period tomb, the Mixtecs laid the remains of one of their nobles, accompanied by slaughtered servants, some time in the mid-fourteenth century. Accompanying the central figure were magnificent objects of gold, cast in the lost-wax process, and silver; turquoise mosaics; necklaces of rock crystal, amber, jet, and coral; thousands of pearls, one as big as a pigeon’s egg; and sections of jaguar bone carved with historical and mythological scenes. While Alfonso Caso and his team had identified the central skeleton as male, other evidence, especially the presence of a weaving kit with battens, picks, spindle whorls, and spindle bowls, suggests strong female associations. Certainly the Mixtecs had a tradition of politically powerful females, and several of these are featured in the codices, but there is as yet little firm evidence to suggest that the skeleton was female. It is likely, however, that the central figure was a female deity impersonator. Both the Mixtecs and the Aztecs had important political and ritual posts based on female deities, the costumes of which often contained spinning and weaving implements.

139 Gold pendant from Tomb 7, Monte Albán, Oaxaca. The pendant was cast in one piece by the lost-wax process. The uppermost elements represent, from top to bottom, a ball game played between two gods, the solar disk, a stylized butterfly, and the Earth Monster. Mixtec culture, Late Post-Classic period. Length 28 ⅔ in (22 cm).

140 Two carved bones from Tomb 7, Monte Albán, Oaxaca. The representations are calendrical and astronomical in meaning. Mixtec culture, Late Post-Classic period. Length about 7 in (18 cm).

Zaachila, a Valley town still bitterly divided between the descendants of the Zapotecs and the Mixtecs, was a Zapotec capital after the demise of Monte Albán, and had a Zapotec king, but its culture was Mixtec. One of its structures has produced two tombs with a treasure trove of Mixtec-style objects almost equal to those in Tomb 7, including some of the most remarkable polychrome pottery ever discovered in the New World: the ceramic gem in this case is a beautifully painted cup with the three-dimensional figure of a blue hummingbird perched on its rim.

Not only to the south, but as far north as Cholula, Mixtec artistic influence was felt, resulting in the hybrid Mixteca-Puebla style which produced some of the finest manuscripts, sculpture, pottery, and turquoise mosaics of latter-day Mexico. Although, like several other rival states in Mexico, the Mixtecs were marked down for conquest in its aggressive plans, they were never completely vanquished by the Aztec empire. They united successfully with the Zapotecs against the intruder and thus avoided the fate of so many other once independent nations of Post-Classic Mexico.

Another important Post-Classic group was the Huastec, located in northeastern Veracruz and adjacent regions, where they continue to live. The Huastec speak a Mayan language, although all other major Mayan languages are found far to the south and east in Guatemala and the Yucatan Peninsula, making Huastec an interesting linguistic outlier.

The Huastec had their own material and artistic culture from at least the Late Preclassic. During the Classic period they continued to develop the ceramic vessels and figurines that first appeared in the Preclassic, but we know of little monumental architecture and art that may be firmly dated to this period. Towards the end of the Epiclassic it is clear that groups with Huastec culture were visiting the regional capital of El Tajín and exchanging fine ceramics with that site.

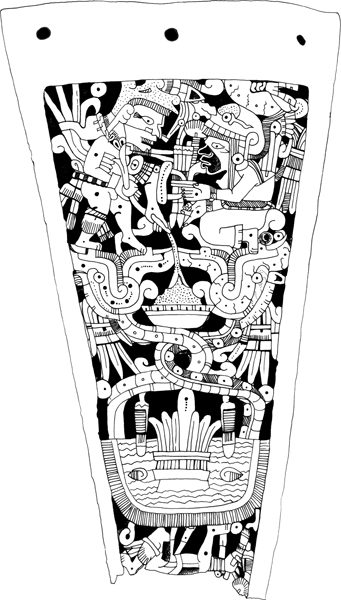

Post-Classic Huastec elite would wear shell ornaments including finely carved shell pectorals. In the upper left of the scene in ill. 141, a figure engages in the same auto-sacrificial ritual seen on a relief panel found at the ball court at El Tajín (see ill. 113), and there are other direct correspondences with Tajín imagery. Surely these Huastec carvers were aware of the artistic tradition of El Tajín, and indeed the Huastec would leave sculpture and other offerings at El Tajín as the latter declined at the beginning of the Post-Classic period.

141 Incised shell object worn on the chest. The elaborate imagery includes two deities emerging from the maws of serpents. The male on the left is engaged in a sacrificial ritual, while the female on the right offers him a bundle of weapons.

The Huastec site of Tamuín is well known for its rich artistic remains, including striking Post-Classic murals. These are exclusively red on white and depict figures with deity markings and elaborate costumes. Some deity markings are reminiscent of the shell pectoral iconography referred to above. The painting style is a regional variant of that seen throughout the Mesoamerican Post-Classic. Tamuín was also the source of the famous Post-Classic sculpture of a young man with extensive body paint or tattooing, called the “Adolescent,” now in the National Museum in Mexico City.

The Aztecs called the territory of the Tarascans, whom they were never able to conquer, Michoacan, meaning “the place of the masters of fish.” This is a fitting name, for much of Tarascan history centers on Lake Pátzcuaro in western Mexico, which abounds in fish. The Tarascans’ own name for themselves and for their unique language is Purépecha. While very little field archaeology has yet been carried out in Michoacan, we fortunately have a long and rich ethnohistoric source, the Relación de Michoacan, apparently an early Spanish translation of one or more original documents in Tarascan, which gives important details of their past and of their life as it was on the eve of the Spanish Conquest.

In the Late Post-Classic, the Tarascan state was bounded on the south and west by areas under Aztec control, and on the north by the Chichimeca. The people were ethnically mixed, but dominated by the “pure” Tarascans, who made up about 10 percent of the population; many of the groups within their territory were in fact Nahuatl-speakers. The Relación tells us of migrations of various tribes into Michoacan, among whom the most important ethnic group was “Chichimec” – probably semi-barbaric speakers of Tarascan, who established themselves on islands in the midst of Lake Pátzcuaro, and who called themselves Wakúsecha. Their first capital was the town of Pátzcuaro, which was “founded” about AD 1325 under their hero-chief Taríakuri; from there they imposed their language and rule on the native peoples and on the other tribes.

Eventually, the Tarascans conquered all of present-day Michoacan and established a series of fortified outposts on their frontiers. Ihuátzio, located on the southeastern arm of the lake, became the capital, to be succeeded by Tzintzúntzan, the royal seat of power when the Spaniards arrived on the scene in 1522.

At the top of the Tarascan hierarchy was the Kasonsí, the king; he acted as war chief and supreme judge of the nation, and was the ruler of Tzintzúntzan. Under him were the rulers of the two other administrative centers, Ihuátzio and Pátzcuaro, and four boundary princes. The Kasonsí’s court was large and attended by a wide variety of officials whose functions give a good idea of the division of labor within the royal household. For instance, there were the heads of various occupational groups, such as the masons, drum-makers, doctors, makers of obsidian knives, anglers, silversmiths, and decorators of cups, along with many other functionaries including the king’s zookeeper and the head of his war-spies.

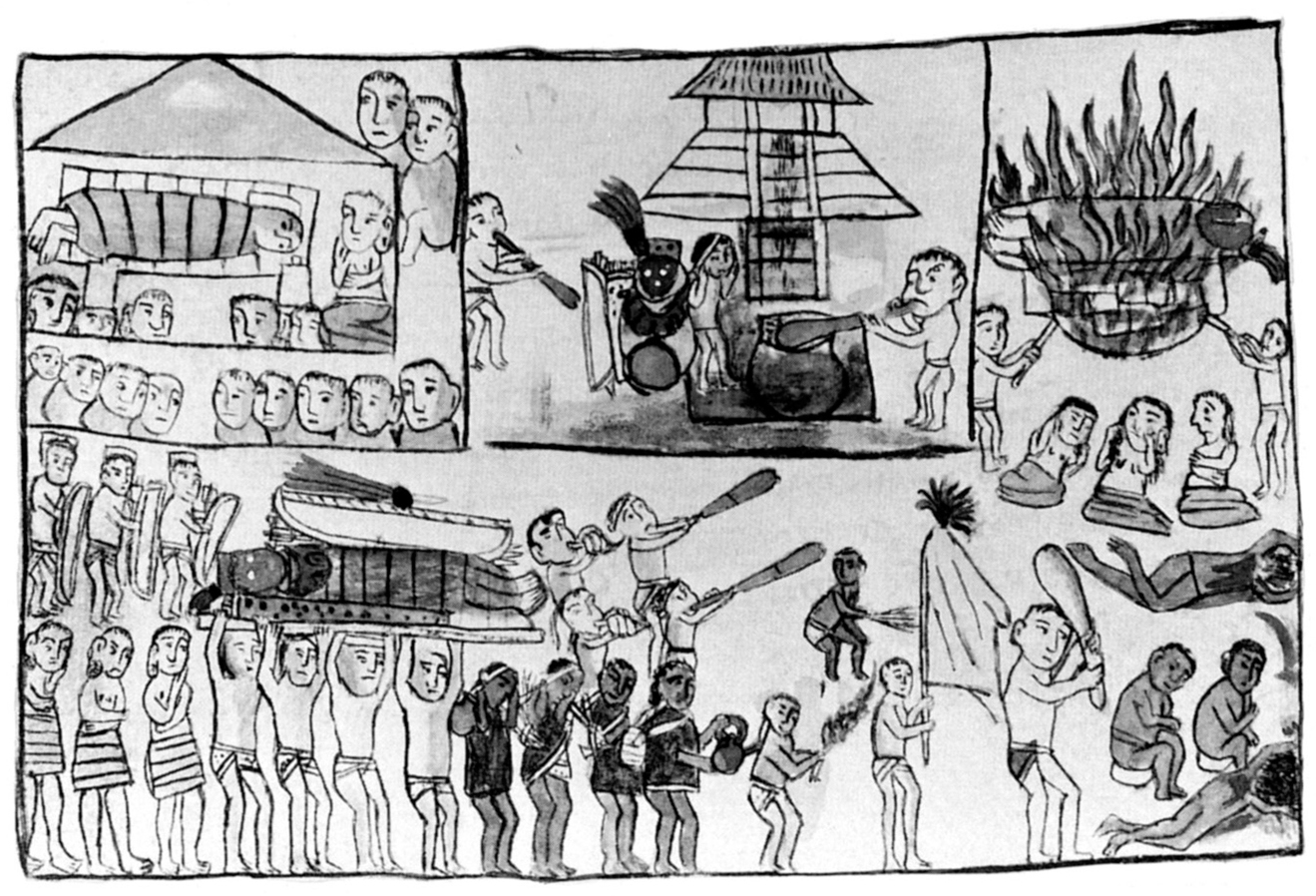

The chronicler of the Relación spends many pages on the funeral of the Kasonsí, which was indeed spectacular, but probably not very different from that of any other Mesoamerican ruler of the time. He was borne to his final resting place attended by Tarascan and foreign lords, with elaborate rites and music. Accompanying him in death were seven important women from his palace, such as his “keeper of the gold and turquoise lip-ornaments,” his cook, his wine-bearer, and the “keeper of his urinal.” Also sacrificed were forty male attendants, including the doctor who had failed to cure him in his last illness! Quite clearly the Kasonsí’s palace was to be replicated for him in the land of the dead.

142 Funeral ceremonies for the Tarascan Kasonsi or king, from the Relation de Michoacan.

Unlike the Aztec (but like the late pre-Conquest Maya), the Tarascan priesthood was not celibate; the badge of the priests was the gourd container for tobacco which was strapped to their backs. At the top of the religious organization was the Supreme High Priest, heading a complex hierarchy with many ranks of priests divided as to function.

The Tarascan state religion, which was probably codified within the last 150 years of the pre-Conquest era, seems remarkably un-Mesoamerican. There was no rain god analogous to Tlaloc, and no Feathered Serpent. Even more remarkable was the absence of both the 260-day count and the use of the calendar for divinatory ends. They did, however, have the approximate solar year of 18 months of 20 days each, plus the five “extra” days. Ball courts were apparently rare, and none are known for Tzintzúntzan itself.

According to data gathered by anthropologist Helen Perlstein Pollard, the universe was made up of three parts: 1) the sky, associated with eagles, hawks, falcons, and the Wakúsecha elite; 2) the earth, viewed as a goddess with four world-directions; and 3) the Underworld, the place of death and caves, inhabited by burrowing animals like mice, gophers, moles, and snakes. The sky was the domain of Kurikaweri, the Sun God, the most important deity in the state cult; his worship demanded huge offerings of firewood which, along with agricultural clearances, must have resulted in extensive deforestation of the Michoacan landscape. Kurikaweri was also the tribal god of the Wakúsecha and a war god, in whose honor there was performed not only human sacrifice but also auto-sacrifice (the shedding of blood from one’s own body), and his earthly form was the Kasonsí himself.

Like the gods on the Greek Mount Olympus, the Tarascan deities were considered to belong to one large family. Kurikaweri’s consort was Kwerawáperi, the earth-mother, a creator divinity from whom all the other gods were born; she controlled life, death, and the rains and drought. The most important fruit of the union between the sky and earth deities was Xarátenga, the goddess of the moon and the sea; her domain was in the west (towards the Pacific Coast), and she could take the form of an old woman, a coyote, or an owl. Naturally, there were many local cults, and each of the ethnic groups subdued by the Tarascan war machine had its own tutelary supernaturals, but these were all subsumed in the cosmological kinship system of the official state religion.

There was no formal education for Tarascan boys, who were trained by their fathers for a particular profession or calling, but young women of the Wakúsecha aristocracy were educated in a special communal house; these were considered “wives” of the tribal god Kurikaweri, and usually married off to army officers.

The ruins of the final Tarascan capital, Tzintzúntzan, rest on a terraced slope above the northeast arm of Lake Pátzcuaro. An enormous rectangular platform, 1,440 ft (440 m), long supports five of the superstructures known as yákatas; each yákata is a rectangular stepped pyramid joined by a stepped passageway to a round stepped “pyramid.” The yákatas were once entirely faced with finely fitted slabs of volcanic stone that recall the perfection of Inca masonry in South America. Those that have been investigated so far contained richly stocked burials, and it is probable that the primary function of these structures was to contain the tombs of deceased Kasonsís and their retainers.

143 View of one of five yákatas or rectangular platforms at Tzintzuntzan, Michoacan, looking north. Tarascan culture, Late Post-Classic period.

What little archaeological evidence we have suggests that the Tarascans were extraordinary craftsmen; many luxury objects in collections that are ascribed to the Mixtecs may well come from Michoacan instead, and it has been suggested that the Tarascans may have taken over some of the northern Toltec trade routes, in particular the commerce in Southwestern turquoise, after the downfall of Tula. The most astonishing of their productions were paper-thin obsidian earspools and labrets, faced with sheet gold and turquoise inlay, but they were master workers in gold and silver, and in bimetallic objects using both of these precious substances.

Casas Grandes and the northern trade route

By the Post-Classic, the southwestern region of what is now the United States had been home to complex cultures for several centuries. There is little doubt that the contact with Mesoamerica already noted for the Epiclassic was continued through this period. While turquoise continued to be traded south to Mesoamerica, we now know that Mesoamerican chocolate made its way to the Southwest by the eleventh century, as witnessed by the discovery of theobromine (a chemical signature of chocolate) in the remains of several ceramic vessels at Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon (northern New Mexico).

Copper bells were also imported in small quantities from West Mexico to the Southwest at the same time or slightly earlier than the appearance of chocolate. It is probably at this time that the people of the Southwest also developed a ritual need for the feathers of tropical birds from Mesoamerica, especially the scarlet macaw. These birds may have been traded north with chocolate as the turquoise flowed south.

Central to any interaction with the Southwest during this period would have been Casas Grandes, Chihuahua, not far south of the border with New Mexico. The site, also referred to as Paquimé, may now be dated to c. 1200–1475. While the population lived in Southwestern-style apartment houses, the Mesoamerican component can be seen in the presence of platform temple mounds, I-shaped ball courts, and the cult of the Feathered Serpent. Warehouses filled with rare Southwestern minerals, such as turquoise, were found by Charles Di Peso, the excavator of Casas Grandes. While it is now clear that the regional elite consumed large quantities of these precious materials, a substantial amount must also have found its way south, where turquoise especially continued to grow in importance for the Tarascans and other Mesoamericans.

The beginnings of the Aztec nation, as we know them from their own accounts, were so humble and obscure that their rise to supremacy over most of Mexico in the space of a few hundred years seems almost miraculous. It is somehow inconceivable that the magnificent civilization witnessed and destroyed by the Spaniards could have been created by a people who were not many generations removed from the most abject barbarism, yet this is what their histories tell us.

But these histories, all of which were written down in Nahuatl (the Aztec language) or in Spanish early in the Colonial period, must be considered in their context, and rigorously evaluated. First, given the nature of central Mexican chronology during the Post-Classic, which was based on the 52-year Calendar Round, it is clear that at least some of the supposedly historical data we are given in the chronicles is cyclical rather than linear: that is, an event which occurs at one point in a given cycle could also have taken place, and will take place, at similar points in other such cycles. Secondly, given the above, there were ample opportunities for the Aztec royal dynasty to rewrite its own history and the history of the nation as changing times demanded; we are told that this was done in the reign of the ruler Itzcoatl, but it apparently was done on a far larger scale during the course of the sixteenth century to cope with the cataclysm of the Spanish invasion and Conquest. The fully developed Aztec state had a cosmic vision of itself and its place in the universe which demanded a certain kind of history, and we now realize that even royal genealogies could be tailored to fit this vision.

It is thus no easy task to reconcile the often-conflicting native chronicles into a coherent story of Aztec origins and rise to power; yet there is considerable agreement on the broad outlines. The story begins with events which followed Tula’s destruction in the twelfth century. Refugees from this center of Toltec civilization managed to establish themselves in the southern half of the Valley, particularly at the towns of Colhuacan and Xico, both of which became important citadels transmitting the higher culture of their predecessors to the savage groups who were then streaming into the northern half of the Valley. Among the latter were the band of Chichimeca under their chief Xolotl, arriving in the Valley by 1244 and settling at Tenayuca; the Acolhua, who founded Coatlinchan around the year 1160; the Otomi at Xaltocan by about 1250; and the powerful Tepanecs, who in 1230 took over the town of Atzcapotzalco, which much earlier had been a significant Teotihuacan settlement. There is no question that all of these with the exception of the Otomi were speakers of Nahuatl, now the dominant tongue of central Mexico. Thus, by the thirteenth century, all over the Valley there had sprung up a group of modestly sized city-states, those in the north founded by Chichimec upstarts eager to learn from the Toltecs in the south.

According to Edward Calnek, this was a time of relative peace in the Valley. The Toltec refugees, occupying the rich lands in the south and west, introduced the organization and ideology of rule by the elite (called pipiltin in Nahuatl); its guiding principle was that only someone descended from the ancient royal Toltec dynasty could be a ruler or tlatoani (“speaker,” a term that will be explained in the next chapter). Those who lacked such descent could demand – if they were powerful enough – women of royal rank as wives. As time passed, the pipiltin came to hold a nearly complete monopoly of the highest offices in each city-state. As for the non-Toltec groups, some adopted the system sooner than others; the Aztecs were to prove the last hold-outs.

Into this political milieu stepped the Aztecs themselves, the last barbaric tribe to arrive in the Valley of Mexico, the “people whose face nobody knows.” The official Aztec histories claimed that they had come from a place called “Aztlan” (meaning “Land of White Herons”), supposedly an island in a lake in the west or northwest of Mexico, and thus called themselves the “Azteca.” One tradition says that they began their migration toward central Mexico in AD 1111, led by their tribal deity Huitzilopochtli (“Hummingbird on the Left”), whose idol was borne on the shoulders of four priests called teomamaque. Apparently they knew the art of cultivation and wore agave fiber clothing, but had no political leaders higher than clan and tribal chieftains. It is fitting that Huitzilopochtli was a war god and representative of the sun, for the Aztecs were extremely adept at military matters, and among the best and fiercest warriors ever seen in Mexico.

Along the route of march, Huitzilopochtli gave them a new name, the Mexica, which they were to bear until the Conquest. Many versions of the migration legend have them stop at Chicomoztoc, “Seven Caves,” from which emerge all of the various ethnic groups which were to make up the nascent Aztec nation. There is a further halt at the mythical Coatepec (“Snake Mountain”) where, somewhat confusingly, Huitzilopochtli is miraculously born as the sun god – a supernatural tale of supreme importance that we shall examine in Chapter 10.

It needs no saying that none of the above is to be taken literally: like many other Mesoamerican peoples, such as the highland Maya, the Aztecs had myths and legends describing a migration from an often vague land of origin to a historically known place where they settled, inspired by the prophecy of a god. Similar legends can be found in the Book of Genesis and among a number of tribal states in Africa and Polynesia. Their function seems clear: to tell the world that the rule by a particular elite was given by history and supported by divine sanction.

Exactly when these Aztecs arrived in the Valley of Mexico is far from clear, but it must have already taken place by the beginning of the fourteenth century. Now, all the land in the Valley was already occupied by civilized peoples; they looked with suspicion upon these Aztecs, who were little more than squatters, continually occupying territory that did not belong to them and continually being kicked out. It is a wonder that they were ever tolerated since, with women being scarce as among all immigrant groups, they took to raiding other peoples for their wives. The cultivated citizens of Colhuacan finally allowed them to live a degraded existence, working the lands of their masters as serfs, and supplementing their diet with snakes and other vermin. In 1323, however, the Aztecs repaid the kindness of their overlords, who had given their chief a Colhuacan princess as bride, by sacrificing the young lady with the hope that she would become a war goddess. Colhuacan retaliated by expelling these repulsive savages from their territory.

We next see the Aztecs following a hand-to-mouth existence in the marshes of the great lake, or “Lake of the Moon.” On they wandered, loved by none, until they reached some swampy, unoccupied islands, covered by rushes, near the western shore; it was claimed that there the tribal prophecy, to build a city where an eagle was seen sitting on a cactus, holding a snake in its mouth, was fulfilled. By 1344 or 1345, the tribe was split in two, one group under their chief, Tenoch, founding the southern capital, Tenochtitlan, and the other settling Tlatelolco in the north. Eventually, as the swamps were drained and brought under cultivation, the islands became one, with two cities and two governments, a state of affairs not to last very long.

The year 1367 marks the turning point of the fortunes of the Aztecs: it was then that they began to serve as mercenaries for the mightiest power on the mainland, the expanding Tepanec kingdom of Atzcapotzalco, ruled by the unusually able Tezozomoc. One after another the city-states of the Valley of Mexico fell to the joint forces of Tezozomoc and his allies; sharing in the resulting loot, the Aztecs were also taken under Tepanec protection.

Up until this time, the Aztec system of government had essentially been egalitarian, and there were no social classes: the teomamaque and the other traditional leaders had remained in control. But in 1375, Tezozomoc gave them their first ruler or tlatoani, Acamapichtli (“Bundle of Reeds”), although during his reign there was still a degree of tribal democracy, in that he was not allowed to make or execute important decisions without the consent of the tribal leaders and the assembly. During these years, and in fact probably beginning as far back as their serfdom under Colhuacan, the Aztecs were taking on much of the culture that was the heritage of all the nations of the Valley from their Toltec predecessors. Much of this was learned from the mighty Tepanecs themselves, particularly the techniques of statecraft and empire-building so successfully indulged in by Tezozomoc. Already the small island kingdom of the Aztecs was prepared to exercise its strength on the mainland.

The consolidation of Aztec power

The chance came in 1426, when the aged Tezozomoc was succeeded as Tepanec king by his son Maxtlatzin, known to the Aztecs as “Tyrant Maxtla” and an implacable enemy of the growing power of Tenochtitlan. By crude threats and other pressures, Maxtlatzin attempted to rid himself of the “Aztec problem”; and in the middle of the crisis, the third Aztec king died. Itzcoatl, “Obsidian Snake,” who assumed the Aztec rulership in 1427, was a man of strong mettle. More important, his chief adviser, Tlacaelel, was one of the most remarkable men ever produced by the Mexicans. The two of them decided to fight, with the result that by the next year the Tepanecs had been totally crushed and Atzcapotzalco was in ruins. This great battle, forever glorious to the Aztecs, left them the greatest state in Mexico.

In their triumph, and with the demotion of the traditional leaders, the Aztec administration turned to questions of internal polity, especially under Tlacaelel, who remained a kind of grand vizier to the Aztec throne through three reigns, dying in 1475 or 1480. Tlacaelel introduced a series of reforms that completely altered Mexican life. The basic reform related to the Aztec conception of themselves and their destiny; for this, it was necessary to rewrite history, and so Tlacaelel did, by having all the books of conquered peoples burned since these would have failed to mention Aztec glories. Under his aegis, the Aztecs acquired a mystic-visionary view of themselves as the chosen people, the true heirs of the Toltec tradition, who would fight wars and gain captives so as to keep the fiery sun moving across the sky.

This sun, represented by the fierce god Huitzilopochtli, needed the hearts of enemy warriors; during the reign of Motecuhzoma Ilhuicamina, “the Heaven Shooter” (reigned 1440–1469), Tlacaelel had the so-called “Flowery War” instituted. Under this, Tenochtitlan entered into a Triple Alliance with the old Acolhua state of Texcoco (on the other side of the lake) and the dummy state of Tlacopan in a permanent struggle against the Nahuatl-speaking states of Tlaxcala and Huexotzingo. The object on both sides was purely to gain captives for sacrifice.

Besides inventing the idea of Aztec grandeur, the glorification of the Aztec past, other reforms relating to the political-juridical and economic administrations were also carried out under Tlacaelel. The new system was successfully tested during a disastrous two-year famine which occurred under Motecuhzoma Ilhuicamina, and from which this extraordinary people emerged more confident than ever in their divine mission.

Given these conditions, it is little surprise that the Aztecs soon embarked with their allies on an ambitious program of conquest. The elder Motecuhzoma began the expansion, taking over the Huasteca, much of the land around Mount Orizaba, and rampaging down even into the Mixteca. Axayacatl (1469–1481) subdued neighboring Tlatelolco on trumped-up charges and substituted a military government for what had once been an independent administration; he was less successful with the Tarascan kingdom of Michoacan, for these powerful people turned the invaders back. Greatest of all the empire-builders was Ahuitzotl (1486–1502), who succeeded the weak and vacillating Tizoc as sixth king. This mighty warrior conquered lands all the way to the Guatemalan border and brought under Aztec rule most of central Mexico. Probably for the first time since the downfall of Tula, there was in Mexico a single empire as great as, or greater than, that of the Toltecs. Ahuitzotl was a man of great energy; among the projects completed in his reign was a major rebuilding of the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan, completed in 1487, and the construction of an aqueduct to bring water from Coyoacan to the island capital.

Ahuitzotl’s successor, Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin (“The Younger”) (1502– 1520) is surely one of history’s most tragic figures, for it was his misfortune to be the Aztec ruler when Mexican civilization was destroyed. He is described in many accounts, some of them eye-witness, as a very complex person; he was surely not the single-minded militarist that is so well typified by Ahuitzotl. Instead of delighting in war, he was given to meditation in his place of retreat, the “Black House” – in fact, one might be led to believe that he was more of a philosopher-king, along the lines of Hadrian. Like that Roman emperor, he also maintained a shrine in the capital where all the gods of captured nations were kept, for he was interested in foreign religions. In post-Conquest times, this was considered by Spaniards and Indians alike to have been the cause of his downfall: according to these ex post facto sources, when Cortés arrived in 1519, the Aztec emperor was paralyzed by the realization that this strange, bearded foreigner was Quetzalcoatl himself, returned from the east as the ancient books had allegedly said he would, to destroy the Mexican peoples. All of his disastrous inaction in the face of the Spanish threat, his willingness to put himself in the hands of Cortés, was claimed to be the result of his dedication to the old Toltec philosophy. The triumphant Spaniards were only too glad to spread the word among their new subjects that this was Motecuhzoma’s destiny, and that it had been foretold by a series of magical portents that had led to an inevitable outcome. We shall examine the life and death of the Aztec civilization in subsequent chapters.