1

Of all the spiritual practices discussed in this book, meditation is the most inward. When meditating, people withdraw from normal activities and usually sit still with their eyes closed.

In this chapter, I start by discussing what meditation involves. Then, after a brief history of meditation, I discuss research into its effects on physical and mental health, and how it affects the physiology of meditators and the activity of their brains. I then look in more detail at the experience of meditation and its implications for our understanding of consciousness, both human and more than human.

To an outside observer, someone sitting quietly with closed eyes could be praying rather than meditating, and indeed, one kind of prayer, contemplative prayer, is a form of meditation. But the internal experience is very different. Most kinds of prayer engage the mind in outward-directed attention, as in praying for other people and making requests. These kinds of prayer are about something. They express intentions. Meditation is not about intentions or requests: It has to do with letting go of thoughts.

I both meditate and pray, and I think of the difference between them as being like breathing in and breathing out. Meditation is like breathing in, directing the mind inward; prayer is like breathing out, directing the mind outward. Meditation involves a detachment from normal, everyday concerns, with inward-directed consciousness; petitionary and intercessory prayer links the life of the spirit to what is happening in the outer world, and as such is outward directed.

There are many techniques of meditation, and various forms are found in all the main religious traditions. Most are practiced while sitting, but some involve moving rather than sitting still, as in Zen walking meditation and qigong, a series of slow, flowing movements combined with deep, rhythmic breathing.

The most widely used practices in the modern Western world are derived from the Hindu and Buddhist traditions, and usually involve silently repeating a mantra—a word or phrase—or paying attention to breathing. What happens is that one part of the mind is involved in repeating the mantra or attending to the breathing, while other parts of the mind continue their normal activities. A continuous flow of thoughts and sensations usually engages and preoccupies us. But having an alternative focus of attention on the mantra or the breath interrupts this flow by providing another reference point for the mind.

In this process, meditators notice that thoughts and sensations flood into their minds, one after another, and that they engage with these thoughts, forgetting all about the mantra or the breathing—until they come back to it again. Then the process begins afresh.

The practice of repeating the mantra or observing the breath relativizes and helps detach the meditator from this continual mental activity that otherwise fills the mind. Through practice, it is possible to watch thoughts come and go like clouds passing through the sky or fish swimming through the water.

Why is this helpful? What’s the point? For people who lead busy, action-oriented lives, meditation can seem like a waste of time. It is the opposite of our usual Western tendency to follow the slogan, “Don’t just sit there: Do something!” It is more like, “Don’t just do something: Sit there!”

One of the effects of meditation is an increase in self-knowledge, a greater awareness of the workings of our minds. We might assume that we are fully in charge of our thoughts and our attention. But even a slight acquaintance with the practice of meditation makes us aware of how many thoughts insert themselves into our minds and how little control we have over this process. Even people who have practiced meditation for many years do not slip instantly into a bliss-filled state of mental stillness. Their minds continue to generate thoughts and images, and their bodies and senses continue to generate sensations, even if they can avoid feeding them with attention and energy.

Meditation is a spiritual practice because it is about living in the present, which can also be experienced as living in the presence of a mind, consciousness, or awareness greater than one’s own. By contrast, the thoughts that continually flow into our minds take us out of the present, into memories, or desires and fantasies, or resentments about past wrongs, or intentions for future activities, or worries about what we ought to have done or ought to do next, or fears about what might happen in the future. All these kinds of thoughts take our minds away from here and now. The practice of the mantra, or the awareness of our breathing, brings us back to the present.

Meditative practices can lead to an enhanced state of consciousness that is experienced as ineffable, too powerful or beautiful to be described. Attempts to translate this experience into cultural and religious frameworks have led to many different terms, including Buddha consciousness, cosmic consciousness, God consciousness, Christ consciousness, true self, formless void, and undifferentiated beingness.1

Although techniques of meditation grew up within Hindu, Buddhist, Jain, Christian, Jewish, Islamic, Sikh, and other religious traditions, meditation can also be practiced in a secular spirit, without any religious framework. In the modern Western world it is commonly used in this nonreligious form, either through various derivatives of Hindu meditation, such as Transcendental Meditation, or of Buddhist meditation, as in mindfulness meditation. These techniques are now taught widely in schools, to business people, to members of the U.S. and other armed forces, to prisoners, and to politicians. Dozens of British members of parliament have learned mindfulness techniques and meet weekly to meditate together.2 Because of its therapeutic benefits, mindfulness meditation is now recommended within the British National Health Service for people suffering from mild or moderate depression, because it has been found to be as effective, and cheaper, than long courses of antidepressant drugs.3

A Brief History of Meditation

The word meditation comes from the same Indo-European root as medicine, measure, and meter. The basic meaning of its Latin ancestor is “to attend to,” with the related meanings “to reflect upon” and “to apply oneself to.”4

This modern usage arose only in the nineteenth century through translation of Eastern spiritual writings. In traditional Catholic Christianity, meditation mainly referred to a meditative reading of the scriptures; the closest equivalent to the modern meaning of meditation was contemplative prayer, a form of silent prayer that went beyond thoughts and images.

No one knows when meditation practices first began. Some people speculate that they started among hunter-gatherers sitting around fires and gazing into the flames and the embers. If so, they could be very ancient indeed, since humans began to use fire at least a million years ago.5 The first actual evidence for meditative practices dates back to about 1500 BC, with an image of a figure seated in the lotus position on a seal found in India.6 It seems reasonable to assume, as many Indians do, that protoyogis were meditating in the Himalayas and elsewhere for several thousand years before texts referring to meditation, such as the Upanishads, were written down, starting around 800 BC.

The Buddha was born and lived in India and spent years in ascetic and meditative practices with yogis before he finally achieved enlightenment while sitting under a bodhi tree. Buddhism became a mass movement in India from the fifth century BC onward, and in numerous monasteries the monks spent part of their time meditating. Meditation may have evolved independently in China and other parts of Asia, but was much influenced by the spread of Buddhism through the establishment of monasteries. In China, Japan, and Korea, meditative practices were established long before the Christian era, and after Tibet was converted to Buddhism in the eighth century AD, meditation techniques evolved in several new ways in remote, high-altitude caves and monasteries. These techniques included spending long periods in complete darkness and isolation, the practice of elaborate visualizations, and dream yoga, involving the cultivation of lucid dreaming, in which the dreamers become aware that they are dreaming, as if waking up within the dream state.

Some Jewish scholars think that meditative practices of some kind were well established very early in Jewish history, even at the time of the patriarchs, and a verse in the book of Genesis about Isaac, the son of Abraham, could refer to a meditative practice. In the King James Bible, the translation of Genesis 24:63 reads: “And Isaac went out into the field to meditate at eventide.” Meditation has also been practiced within the Jewish mystical tradition, Kabbalah, for over a thousand years.

With the growth of Christian monasticism, starting with the monks in the Egyptian desert in the third century AD, most notably Saint Anthony of the Desert, a range of meditative practices became part of Christian tradition. In the Eastern Orthodox churches, these methods were widely diffused, especially in the form of the “prayer of the heart” or the “Jesus prayer,” a very short prayer that calls on the name of Jesus. The repetition of these prayers is very similar to the repetition of mantras in the Hindu and Buddhist traditions. The repetitive use of mantra-like prayers is a common practice in the Roman Catholic tradition, especially using rosaries.

In the Islamic world, Sufi groups encouraged meditation, especially using one of the names of God, repeated over and over again like a mantra. This practice is called zikr or dhikr.

Some Westerners learned meditative practices in India and in Buddhist countries in the nineteenth century, or were taught them within esoteric movements like the Theosophical Society. Meditation spread more widely in the West in the twentieth century through a series of Asian teachers, notably the Indian yogi Paramahansa Yogananda (1893–1952) and the Japanese teacher D.T. Suzuki (1870–1966), who aroused much interest in Zen Buddhist meditation, especially after he settled in New York in the 1950s.7

A new era of interest in meditation began in the 1960s as a result of the psychedelic revolution, the rise of the counterculture, and the hippie movement. After the Beatles met the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (1918–2008) in 1967, organizations teaching meditation became increasingly popular and successful, not least the Maharishi’s own Transcendental Meditation movement. In the early 1990s, one of the Maharishi’s personal physicians and close associates was the Indian American doctor Deepak Chopra.8 After his break with the Maharishi in 1993, Chopra continued to spread the message of meditation to millions of people in the West. In addition, the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1950 drove many Tibetan monks and teachers into exile, including the Dalai Lama, with the result that Tibetan Buddhist teachings have been widely dispersed.

Many different forms of meditation are now taught in Western countries, including a range of Hindu-derived techniques and many Buddhist methods, among them Tibetan, Zen, and Theravada Buddhist meditation, which encompasses vipassana, whose modern form originated in Burma. Vipassana means “insight into the true nature of reality” and involves being mindful of breathing, feelings, thoughts, and actions. Secularized meditation techniques are now very widely taught and are used therapeutically in healthcare systems. Meanwhile, several forms of Christian, Jewish, and Muslim meditation have been revived and popularized.9

One of the pioneers of scientific research on meditation was a cardiologist at Harvard Medical School, Herbert Benson, who began studying Transcendental Meditation in the late 1960s and summarized his results in the influential book The Relaxation Response.10 Another pioneering researcher, Jon Kabat-Zinn at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, combined vipassana and Zen practices with yoga to form a training regime called “mindfulness-based stress reduction.” In the U.S., there are now hundreds of stress-reduction clinics based on these procedures. They are located in hospitals and health centers, and doctors can refer patients to them.11

There are also many teachers of mindfulness meditation, and countless newspaper and magazine articles advocate meditation as a stress-reduction and life-enhancement technique. Popular books tell how meditation has changed the authors’ lives and the lives of the people they know, and these books encourage their readers to change their own lives by meditating. One of the most engaging is A Mindfulness Guide for the Frazzled by the comedian Ruby Wax. Several prominent atheists have also become advocates of meditation, including Susan Blackmore in her book Zen and the Art of Consciousness.12 Sam Harris, a New Atheist best known for his anti-religious polemics, now teaches meditation in online courses. His book Waking Up: Searching for Spirituality Without Religion13 is intended as “a guide to meditation as a rational spiritual practice informed by neuroscience and psychology.”

Enormous numbers of people now meditate. In one of the largest and most comprehensive surveys, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) found that in 2012, approximately eighteen million adults—8 percent of the adult population of the U.S.—and one million children were practicing meditation.14

I first began to meditate in 1971, after learning how to do so from a Transcendental Meditation teacher in Cambridge. I was an atheist at the time, and I liked the fact that this practice did not involve any overt religious beliefs. I could think of it as purely physiological and psychological. However, when I moved to India in 1974 to work at ICRISAT in Hyderabad, I realized that meditation practice was part of a much wider religious and philosophical context, and I became increasingly interested in Indian philosophy about the nature of consciousness. When I was living in Hyderabad, I also came to know a Sufi teacher and started meditating with a mantra-like wazifa. Later, from 1978–9, I lived in a Christian ashram in Tamil Nadu, where I adopted a Christian form of meditation with the Jesus prayer and generally meditated for an hour in the morning and an hour in the evening, sitting on the bank of the sacred Cauvery River. I also learned the vipassana technique.

I gave up meditating when I had young children. Sitting quietly in the morning was impossible with lively boys around. But I started meditating again when they had grown up. I use a Christian mantra and usually meditate for twenty minutes in the morning.

Like millions of other people, I find that meditation has a calming effect, helps me to think more clearly, and makes me more aware of my mind’s workings. From time to time, unpredictably, I have moments of great peace and joy.

The Relaxation Response and Stress Reduction

Meditation practices have attracted much scientific attention, precisely because they have been secularized. This would not have happened, or at least not so soon, if they had been seen as primarily religious.

The pioneering research by Herbert Benson and his colleagues at Harvard Medical School in the 1970s focused primarily on the “relaxation response.” Benson interpreted this response as a reduction in the fight-or-flight reaction to danger, which is associated with the activation of the sympathetic nervous system.15 Despite its name, the sympathetic nervous system is not about sympathy, but is one part of the unconscious or autonomic nervous system. The other part is the parasympathetic nervous system, sometimes called the rest-and-digest or feed-and-breed system. The two sides of the autonomic nervous system are complementary. The sympathetic system is activated when there is something to be afraid of, the parasympathetic system when there is nothing to be afraid of. At the most basic level, the parasympathetic system has to be dominant if we are to eat, cry, have sex, urinate, or defecate.

In acute stress, the fight-or-flight response is triggered by the release of adrenaline, which causes an increase in heart rate and blood pressure; a decrease in blood flow to the extremities, including the sexual organs; and a slowing of digestion. The fight-or-flight response also increases the level of the hormone cortisol, which reduces the activity of the immune system. (In medicine, cortisol is called hydrocortisone, and it plays a useful role in the temporary reduction of inflammation.) When the danger has passed, these systems return to normal in the relaxation response. However, in chronic stress, this physiological arousal persists, which can lead to a decrease in the activity of the immune system and continual anxiety.

Benson’s group investigated a range of techniques for inducing the relaxation response, including meditation, breathing exercises, yoga, and muscle relaxation. They also tested the effects of hypnosis, which could elicit the relaxation response when the hypnotist suggested that the subject had entered a state of deep relaxation. All these methods led to decreases in oxygen consumption, respiration rate, and heart rate. In patients with high blood pressure, the blood pressure went down.

In some ways, the relaxation response resembled sleep, but whereas in sleep oxygen consumption declined gradually over several hours until it was about 8 percent less than during wakefulness, in meditation it declined by 10–20 percent within a few minutes. There was also a decrease in the level of lactic acid in the blood, falling by around 40 percent within ten minutes of starting to meditate. Lactic acid is normally produced as a result of muscular activity, and in people prone to anxiety, it increases the likelihood of anxiety attacks.

In addition to these physiological changes, the relaxation response induced altered states of consciousness that people described as “feeling at ease with the world,” “peace of mind,” and a “sense of well-being” like that experienced after a period of exercise, but without the fatigue. Most people described these feelings as pleasurable.16 More recent research, discussed below, has revealed how meditation and the relaxation response affect the activity of various regions of the brain, including a deactivation of the default mode network, which is associated with rumination and being lost in thought.

Benson’s methods were disseminated very widely through health centers, clinics, and church groups, reaching millions of people from the 1970s onward. In addition, his book The Relaxation Response, first published in 1975, was a bestseller that sold millions of copies.

Benson recommended the use of a focus word or mantra, and advised people to use a word, phrase, or short prayer that was personally meaningful, depending on their own religious tradition. He encouraged secular or nonreligious people to focus on “words, phrases or sounds that were compelling to them, such as the words love, peace, or calm.”

Here are Benson’s instructions:

The other main strand of the modern meditation movement was popularized by Jon Kabat-Zinn, who was introduced to Zen meditation as a student. He went on to study meditation with other Buddhist teachers, most importantly Thich Nhat Hanh, a Vietnamese Buddhist monk, and Seung Sahn, a Korean Zen master. Kabat-Zinn was Jewish by birth but did not identify with any religion, even Buddhism. Instead, he deliberately secularized the Buddhist teachings he had received. He launched his stress reduction and relaxation program in 1979. This evolved into the practice he called mindfulness-based stress reduction, which has spread worldwide.

The main difference between the work of Benson and Kabat-Zinn is that Benson’s recommended technique stems from the Hindu tradition of mantra-based meditation, which is a focused-attention method. Kabat-Zinn’s mindfulness procedure is sometimes called open-monitoring meditation, because it involves the nonreactive monitoring of experience from moment to moment. Benson’s method involves mantras; Kabat-Zinn’s does not.

What both kinds of meditation have in common is that they focus attention on the present moment. They create an alternative center of attention in the form of the mantra or the awareness of bodily sensations, which has a distancing effect on thoughts, feelings, ruminations, fantasies, and worries. These continue to arise, but insofar as meditators return to the mantra or pay attention to breathing and other bodily sensations, they can come back to present awareness. They are once again in the moment.

Another kind of meditation is derived from the Buddhist technique of metta, wherein the meditator focuses on developing compassion or a sense of care for living beings. In its secularized form, it is called loving-kindness meditation. Thich Nhat Hanh calls the practice of compassion “engaged Buddhism” and draws strong parallels with the Christian tradition of loving-kindness. He also links the Christian understanding of the Holy Spirit to the experience of mindfulness: “We have the capacity to recognize the presence of the Holy Spirit wherever and whenever it manifests. It too is the presence of mindfulness, understanding and love.”18

Various forms of meditation are still taught within religious traditions, for example by Tibetan lamas, by Hindu, Jain, and Sikh gurus, by Sufi masters, and by Jewish and Christian teachers. Indeed, all forms of meditation are derived from religious traditions.

Health Benefits of Meditation

Since the 1960s, scientific journals have published thousands of papers on the effects of meditation on health and well-being.19 These effects include a reduction of anxiety, a reduction in allergic skin reactions, decreased incidence of angina and cardiac arrhythmias, relief from bronchial asthmas and coughs, reduced problems with constipation, fewer problems with duodenal ulcers, less dizziness and fatigue, lower blood pressure in people suffering from hypertension, alleviation of pain, reduction of insomnia, improved fertility, and help in mild to moderate depression.20

Studies of schoolchildren and college students who meditated showed significant positive effects on social competence and well-being. Even the U.S. Marine Corps tried using “mindfulness-based mind fitness training” to enhance the performance of troops. A journalist who visited a training camp in Virginia described how the rigorous training procedure was interspersed with periods of total silence: “You’d see men sitting in the lotus position in their field uniforms with rifles across their backs.” The training they received was designed to lower stress, increase mental performance under the duress of war, and improve the capacity for empathy.21 But this shows how far secular mindfulness meditation has moved from its Buddhist roots. It is hard to imagine how increased military effectiveness can be combined with loving-kindness toward enemies.

Meditation is also helping U.S. military veterans. One study found an impressive reduction in symptoms of post-traumatic stress and depression,22 and in 2015 meditation was being offered at fifteen Veterans Affairs centers.23

Many studies have shown that mindfulness meditation is at least as effective as, if not more effective than, antidepressant drugs for treating mild to moderate depression.24 It is also cheaper, and of course has no drug-induced side effects.

This is not to say that meditation is without danger. Out of the many people who try meditating, a small minority have adverse reactions. According to the official NIH guidelines in the U.S., “Meditation is considered to be safe for healthy people. There have been rare reports that meditation could cause or worsen symptoms in people who have certain psychiatric problems.”25 This is not a new issue. Most spiritual traditions have long recognized that there can be periods of difficulty on the spiritual path, which the sixteenth-century Christian mystic Saint John of the Cross called the “dark night of the soul.” This is one reason why religious traditions put a strong emphasis on guidance by a competent teacher. In the secular context, meditation is often portrayed as a self-improvement practice, good for stress reduction and enhanced productivity. In the interests of spreading it quickly, it is often taught through books and online courses, and the personal help of experienced teachers is less readily available.26

Nevertheless, for millions of people, meditation brings both subjective and objective, measurable benefits. In the modern Western world, the most persuasive measure is money. A recent large-scale study compared thousands of people who received training in a “relaxation response resiliency program,” which included meditation, with thousands of otherwise comparable people who did not have this training, and looked at the medical expenditures they incurred. Over a median period of 4.2 years, those who had received the relaxation training had 43 percent fewer medical bills per year, an effect that was highly statistically significant. They also made half as many visits to emergency rooms.27 Meditation can save people billions of dollars a year.

Changes in Brains Induced by Meditation

Meditation tends to reduce ruminations, obsessions, cravings, fantasies, and being lost in thought. Not surprisingly, these changes in the activity of the mind are associated with changes in the activity of the brain.

During rumination and when we are lost in thought, a linked set of brain regions becomes active. These are called the default mode network, made up of interacting brain regions that become active by default when someone is not involved in an outward-directed task. This network is involved in daydreaming, mind wandering, self-centered thinking, remembering the past, planning for the future, and also thinking about other people. As meditation proceeds, and as meditators become more experienced, there is a decrease in the activity of the default mode network.

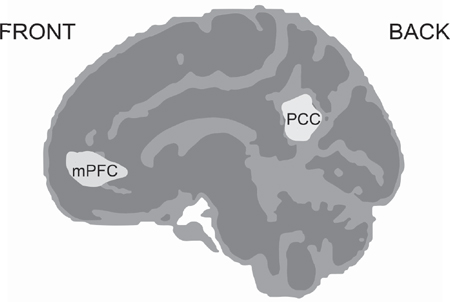

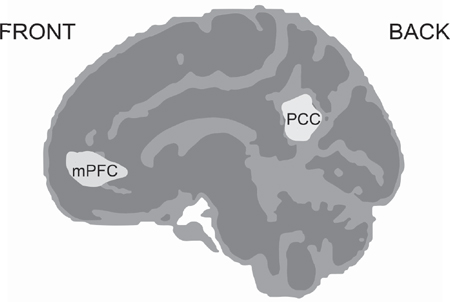

One of the key areas of the brain involved in the control of attention seems to be the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), which is near the back of the head. Another important part of this network is the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC; fig. 1). When attention is focused on a specific task, these areas of the brain are deactivated. When the brain is not in a state of focused attention, they are activated and link up with the default mode network.

Figure 1. A cross section of the human brain showing the location of the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC)

Meditation is not the quickest way of shutting down the default mode network. Engagement in physically or mentally challenging activities shifts the mind very quickly, focusing attention in the moment. Here is an example, from my friend Gifford Pinchot:

In my forties, I was so intensely involved in my work I could not stop thinking about it, not even after work. Meditation did not change this. However, when rock climbing, after getting above fifty feet up, I thought about nothing but the next moves, if I thought at all. Often it was just a flow of motion in which my body seemed to know what to do next.28

Not only rock climbing but also a great many sports or other activities bring people into the present. Engagement in physical work, playing music, looking after children, singing, dancing, and many other activities switches attention to the present moment. And all of these can play a role in spiritual practices, as I discuss elsewhere.

In many ways, meditation is the easiest spiritual practice for scientists to investigate. Meditators are literally sitting (or lying) targets for brain researchers. Either this research involves fitting sets of electrodes to people’s skulls to measure the electrical activity in their brains, as in electroencephalography (EEG), or else they have to lie down and be slid into large, noisy scanning machines, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machines, in which they must stay very still. People who are mobile are much harder to study. It would not be possible to put someone who is rock climbing into an fMRI machine, nor someone who is surfing or snowboarding, nor a golfer making a shot, nor a member of a football team playing in a game.

Not surprisingly, experienced meditators show bigger changes in their brains when meditating than novices. In a collaborative study with the Dalai Lama, the neuroscientist Richard Davidson arranged for eight experienced Tibetan monks to be tested in his laboratory at the University of Wisconsin. These monks had been trained for an estimated ten thousand to fifty thousand hours each, over fifteen to forty years. As a control, ten student volunteers with no previous meditation experience were tested after only one week of training. The participants were fitted with EEG sensors containing 256 electrodes and asked to meditate for short periods.

Davidson was especially interested in measuring gamma waves, some of the highest-frequency brain impulses detectable by EEGs. Gamma waves range between twenty-five and one hundred cycles per second, and are usually around forty.

The electrodes picked up much greater activation of fast-moving and unusually powerful gamma waves in the monks, and found that the movement of the waves through their brain was far better organized and coordinated than in the students. The meditation novices showed only a slight increase in gamma-wave activity while meditating, but some of the monks produced gamma-wave activity more powerful than any previously reported in healthy people.29

The changes in brain activity that occur when people are meditating are not merely temporary; they seem to lead to changes in brain structure as well. In a study at Harvard Medical School by Sara Lazar and her colleagues, the brains of long-term meditators were compared with those of a control group. The meditators turned out to have more gray matter in the auditory and sensory cortex.30 As Lazar remarked, this “makes sense. When you’re mindful, you’re paying attention to your breathing, to sounds, to the present moment experience, and shutting cognition down.”

There was also more gray matter in the frontal cortex, which is associated with working memory and decision-making. Lazar said, “It’s well documented that our cortex shrinks as we get older—it’s harder to figure things out and remember things. But in this one region of the prefrontal cortex, 50-year-old meditators had the same amount of gray matter as 25-year-olds.”31

Was this simply because of some selection bias in the people that Lazar’s team studied? To find out, they recruited participants who had not meditated before and arranged for them to have eight weeks of training and practice in mindfulness meditation. They then compared the changes in their brains with a control group that did not meditate.

Astonishingly, in just eight weeks, there were measurable changes in the brains of the meditators, with increases in the density of gray matter in the PCC (fig. 1), the left hippocampus, the temporoparietal junction (TPJ) at the side of the cortex, toward the back of the brain, and a region of the brain stem called the pons.32 The researchers speculated that the changes in the hippocampus might be associated with improved regulation of emotional responses, and in the PCC and TPJ with “the perception of alternative perspectives.” The PCC, as we’ve seen, is involved in the control of attention.

We are not surprised when exercises such as weightlifting lead to physical changes in muscles. Changes in brains as a result of specific mental activities are only surprising because neuroscientists used to believe that brain structures were more or less fixed in adults. But there is now a widespread recognition of neuroplasticity: Brains can change.

All these studies tell us about brains but do not tell us what is going on in consciousness. Are the conscious changes that occur during meditation all located inside the head? Or do they involve the connection of the meditator’s consciousness with a far greater mind, the source of consciousness itself?

What Meditation Shows Us About Minds

In the modern world, all sorts of people meditate, including atheists and agnostics. Probably everyone who meditates agrees about its benefits in reducing stress and in revealing something of the nature of the mind. But opinions differ greatly when it comes to interpreting the moments of calm and joy that go beyond our normal experiences.

For materialists, meditation is nothing but an activity of the brain, and therefore all its effects are confined to the brain, including the highest states of mystical experience. At first sight this seems plausible. The practice of meditation does indeed change the physiology and activity of the brain and other parts of the body. It also leads to structural changes in the brain tissue. But this does not prove that the experience is confined to the brain. If I look out my window at a tree, specific changes occur in my retina, optic nerves, and in the visual-processing parts of the brain. But these changes in the brain do not prove that the tree is nothing but a product of brain activity. The tree really exists, and it is outside my brain.

The crucial question is whether meditation enables our minds to connect with a mind or consciousness vastly greater than our own. This is what meditators have traditionally believed, and this has been one of the principal motives for meditation. It can help us to transcend our own minds and our own beings. The experience of bliss, nirvana, or samadhi is not just about well-being, but about experiencing the nature of reality more deeply.

One of the key insights of the rishis, or seers of ancient India, was that our minds are of the same nature as the ultimate consciousness that underlies the universe. For example, in the Kena Upanishad, we read:

What cannot be spoken with words, but that whereby words are spoken: know that alone to be Brahman, the Spirit; and not what people here adore.

What cannot be seen with the eye, but that whereby the eye can see: know that alone to be Brahman, the Spirit; and not what people here adore.

What cannot be heard by the ear, but that whereby the ear can hear: know that alone to be Brahman, the Spirit; and not what people here adore.33

We know about consciousness by experiencing it. Brahman—or God, or ultimate reality—is not proved by scientific observations of external reality, that which is “seen by the eye.” Rather, our very ability to speak, to see, and to hear comes from our participation in this ultimate mind, from which all other minds are derived. One often-used analogy is buckets of water reflecting the sun. We see a reflection of the sun in each bucket, and each reflection seems separate from the others, but they are all reflections of the same sun. Likewise, our minds seem separate, but they are all reflections of the same ultimate mind or consciousness.

Buddhists differ from Hindus in their interpretation of this ultimate reality. Hindus think of it as Brahman, the Lord—or God or the Spirit—whereas Buddhists avoid calling it God. When the Buddha achieved enlightenment sitting under the bodhi tree, he entered a conscious state of nirvana, of ultimate peace and blessedness beyond all the changes of this world. Nevertheless, in both traditions, this ultimate reality is vastly greater than our brains, and it is not confined to the insides of our heads. Similarly, for Jewish, Christian, and Muslim mystics, a mystical experience of God is not merely happening inside our brains, but is a direct connection with God’s being.

Saint Thomas Aquinas (1225–74) saw the human experience of blessedness or joy as a sharing in God’s being:

But good in the highest degree is found in God, who is essentially the source of all goodness. And so it follows that the final perfection of human beings and their final good consists of adhering to God . . . Blessedness or happiness is simply the perfect good. Therefore, all sharers in blessedness are necessarily blessed only by sharing in the blessedness of God, who is essential goodness itself.34

From this point of view, the benefits of meditation are not simply physiological. Meditation helps bring our minds closer to ultimate reality, which is conscious, loving, and joyful. Our minds are derived from God and share in God’s nature. Through meditation we can become aware of our direct connection with this ultimate source of our consciousness, when we are not distracted by thoughts, fantasies, fears, and desires. And this contact with the ultimate consciousness is inherently joyful.

Yet the practice of meditation does not necessarily lead to this conclusion.

The Ambiguity of Secular Buddhism

There is an inherent ambiguity in the modern meditation movement. At one extreme is the use of meditation as a learnable technique to reduce blood pressure, diminish stress, help healing, prevent depression, and give greater psychological insight. Meditation can help people who live frazzled lives. There is plenty of scientific evidence for all this. Mindfulness seems fully compatible with the philosophy of scientific materialism, which locates the mind inside the head. From this point of view, meditation is rather like going to a mental gym for a regular workout.

On the other hand, both the Hindu and Buddhist traditions start from a completely different conception of reality. They see the world as full of suffering, pain, and conflict. The only way to get free is through spiritual liberation. Practitioners can escape from the world of suffering through a kind of vertical takeoff, leaving the cycles of birth and death behind them. When liberated or enlightened, the consciousness of the seer becomes one with the consciousness that underlies the universe. But in the Mahayana Buddhist tradition, as in Tibet, those who attain this state of liberation, or Buddhahood, are encouraged to become bodhisattvas, voluntarily returning after death to another human life, through rebirth, to help liberate all sentient beings.

Hindus think of this consciousness as the consciousness of God or Brahman. The ultimate reality is sat-chit-ananda. Sat means being; chit, consciousness or knowledge; and ananda, joy. This ultimate consciousness includes the knower, the conscious ground of being; the known; and the joy of knowing and being. Insofar as practitioners experience their minds as absorbed into the being of God, they are joyful because God is joyful.

The Buddhist description of ultimate conscious reality is nirvana, enlightenment, or liberation from embodied existence, and absorption into joy and freedom. Meditation is not an end in itself, but part of a path that can lead to liberation.

The Hindu and Buddhist traditions, like other religions, take for granted the existence of realms of consciousness far beyond the human. They see human consciousness as derived from and connected with an ultimate conscious source. By contrast, for materialists, it is all in the brain. There is no such thing as a vast realm of consciousness beyond the human level. This is an illusion, an irrational belief system.

Most secular practitioners of meditation may not notice this conflict. Their focus is primarily on their own lives. But the secular Buddhist movement makes this ambiguity explicit. Secular Buddhists are practitioners who use Buddhist techniques, but reject Buddhism as a religion. They dissociate themselves from myths about the Buddha’s birth and from beliefs in numerous bodhisattvas, dakinis, and other spiritual beings. They reject the idea that nirvana is in any sense “out there” and exists independently of human minds. They interpret the life of the Buddha as that of a philosopher teaching a way of life, rather than a religious leader.35

One of the most extreme exponents of the secular Buddhist movement is Sam Harris, whom I mentioned earlier. After a secular upbringing and experiences with psychoactive drugs as a student, he dropped out of college and went in search of self-understanding to India, where he studied with a series of gurus for more than two years. He then went back to America, resumed his studies, and did a PhD in neuroscience, before launching a new career as a militant atheist. With his first book, The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Reason, he achieved international fame as one of the New Atheists. He is now going further than other anti-religious crusaders. He has found a new way of attacking religion. Instead of denying spirituality, he wants to take it over and remove it from the realm of religion. In his book Waking Up: Searching for Spirituality Without Religion, he writes, “My goal is to pluck the diamond from the dunghill of esoteric religion.”36

Harris’s principal teacher was Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, a Tibetan master who lived for more than twenty years on retreat in a hermitage. His title tulku meant that in the eyes of Tibetans and in his own eyes, he was a reincarnated master, or more precisely the “emanation” of a deceased master called Nubchen Sangye Yeshe, a ninth-century student of Guru Padmasambhava. Urgyen Rinpoche was a teacher in the Dzogchen tradition, able to transmit the experience of self-transcendence directly to a student. Harris received this transmission from him, and in only a few minutes his life was changed.37

However, he denied that there was anything “supernatural, or even mysterious, about this transmission of wisdom from master to disciple.” Instead, he said, “Tulku Urgyen’s effect on me came purely from the clarity of his teaching . . . I didn’t have to accept Tibetan Buddhist beliefs about karma and rebirth or imagine that Tulku Urgyen or the other meditation masters I met possessed magic powers.”38 But if this astonishing Dzogchen transmission is nothing but a matter of clear teaching, then why cannot Harris, or anyone else, transmit it through books or online courses? In the Tibetan tradition, transmission involves more than words. It needs a living contact. It is a kind of resonance whereby the master is able to induce something of his own conscious state in the person he is initiating.

Harris rejects many of the beliefs of his own teachers as superstitious.39 He believes that even the Dalai Lama is fundamentally mistaken, because, like many other Tibetans, he believes in rebirth and consults oracles. Unlike Harris, he has not plucked “the diamond from the dunghill of esoteric religion.”

Harris’s default position is the materialist theory of consciousness advocated by most of his atheist colleagues. Materialists believe that consciousness is nothing but brain activity. However, Harris says that he is not fully committed to this theory. He admits the possibility of consciousness beyond the brain, which all religions accept, but he remains hostile to all religions:

I remain agnostic on the question of how consciousness is related to the physical world. There are good reasons to believe that it is an emergent property of brain activity, just as the rest of the human mind is. But we know nothing about how such a miracle of emergence might occur. And if consciousness were irreducible—or even separate from the brain in a way that would give comfort to Saint Augustine—my worldview would not be overturned. I know that we do not understand consciousness.40

Harris is a sophisticated atheist, and he admits that we do not understand consciousness. But then how can he be so sure that human (and animal) consciousness is all that there is, and that there are no trans-human realms of conscious being? Surely this is no more than an assumption, a belief, an atheist leap of faith.

Most meditators probably just do what they do and are not motivated to engage in this debate. But this is not solely a theoretical question: It affects people’s motivation. Is meditation only about improved health and fitness, increasing a person’s ability to get what they want in the world? Is my meditation simply about me? Or is it about linking to a higher, more-than-human realm of consciousness?

The same questions arise in relation to the physical and mental benefits of meditation. Are these purely because of the physiology of the relaxation response and changes in brain activity and anatomy? Or, in addition, do some of these benefits flow from connecting with a ground of conscious being beyond individual humans? Religious people acknowledge this connection to a greater consciousness and its transformative potential. Atheists and secular humanists do not. But as they continue to meditate, their understanding may change, as I found myself.

Mystics in all religious traditions have had direct experiences of being connected to, or absorbed into, more-than-human consciousness. Atheists claim that these experiences are illusions produced inside brains and assume that they cannot refer to anything beyond the human level. But why not trust rather than reject these direct experiences? After all, the only way we can know about consciousness is through consciousness itself. And we know that one consciousness can link with other consciousnesses, as in our relationships with each other. Through meditation and through mystical experiences, our conscious minds connect with more-than-human conscious minds, and ultimately with the source of all consciousness. Just as we can come into a kind of resonance with each other through love and through taking part in shared activities, so we may come into resonance with more-than-human minds when we are not preoccupied with our own desires, fantasies, and fears.

Two Meditative Practices

MEDITATION

If you already practice meditation, I have no suggestion to add. If you used to practice meditation and have given it up, I suggest starting again, with a daily routine.

If you have never practiced meditation, you can try it by following the procedure for the relaxation response (pp. 19) or the methods in one of the many books on meditation. Or you can look for a teacher you respect, preferably one who is consonant with the rest of your spiritual or religious life. If you are an atheist, you can follow Sam Harris’s41 or Ruby Wax’s42 instructions, or find one of the many secular teachers. If you are on a religious path, then you will probably feel most comfortable following the instructions of someone in your own tradition. There are meditation teachers in all the major religious traditions: Jewish,43 Christian,44 Muslim,45 and many Hindu and Buddhist. But above all, make a commitment to practice and try to create a regular routine. If you do not, your practice is likely to be squeezed out by all the demands of your busy life.

If you meditate regularly, you will start on a journey that can take you far beyond your existing beliefs and limitations, as well as making you happier and healthier.

SPENDING TIME IN SILENCE

The modern world crowds out silence with noise and distractions. We are used to being busy, with our minds racing. In addition, most people are perpetually accompanied by a source of endless distraction in the form of a cell phone. Meditation is one way of being silent, but there are others. For example, if I am walking in the countryside and talking to someone, I notice much less than if I am walking silently. If I am in a garden, I barely see the plants and hardly hear the birds when I am chatting. If I go to an art gallery, I do not see the pictures as well if I am looking at them while I am talking to other people, because I am bound up in words. Silence helps us to be more open to sights, sounds, and smells, to the world around us.

Hindu yogis and Tibetan sages traditionally meditate in remote caves in the mountains. Jesus used to go to the hills to pray, and Jewish prophets went into the wilderness. Christian hermits and monks often lived in places remote from towns and cities, and some still do. There have always been wild, silent places, and there still are, especially at night. Within towns and cities, many Anglican and Roman Catholic churches are open during the daytime, when there are no services going on, and provide oases of quiet. The streets outside may be intense and busy, but there is often a remarkable stillness and peace within these sacred buildings.

Finding times and places to be silent is one of the simplest ways to expand our sensory and spiritual awareness.