CHAPTER 5

No man is an island, entire of itself.

—JOHN DONNE

Consider the full-page ad for Harley-Davidson motorcycles that ran in USA Today on August 27, 2009. IT’S A FREE COUNTRY, the headline proclaimed, BUT HAVE YOU FELT LIKE THAT LATELY? Then, in smaller print, but still in caps: IS IT STARTING TO FEEL CLAUSTROPHOBIC INSIDE THE SAFETY NET? It seemed to us like a strange ad to place at a time when the economy was reeling and polls showed Americans were feeling very insecure indeed. But in its own way, it beautifully summarized a dominant American idea: freedom trumps security.

Yet much evidence suggests that a sense of security actually provides the foundation for risk-taking, freedom, and individualism, much as discipline, patience, and knowledge of music fundamentals provide the basis for free-wheeling jazz. Happiness polls have found that in countries like Denmark, where the safety net is tightly woven, respondents are most likely to say that they feel “free to do the things I want to do.”1 Sure, it’s possible to go too far and remove too much of the risk and adventure from life. No doubt that was the case in the former Soviet Union. But that’s hardly the case in this economy, where the safety net has been getting weaker for the past thirty years.

Somewhere in the middle of his long reign, George W. Bush offered a glimpse of his vision for our future. Bush called it the Ownership Society.2 In his view, John Donne was wrong, and probably a wimp. Indeed, Bush declared in effect, “Every man is an island, fully responsible for himself.” Every American, Bush made clear, should provide for his or her own social security, health care, retirement plans, and a host of other forms of insurance. Americans were told to say good-bye to the concept of social insurance and pooled risk, to the idea that they are all in this together.

Bush might have called it the You’re on Your Ownership Society. But this idea didn’t originate with him. It was the culmination of a generation of policies directed at stripping Americans of security guarantees they had become accustomed to since the New Deal.

“You know how to spend your money better than government does,” said Bush.3 Clever phrase; countless heads must have bobbed in affirmation. But when it comes to economic security, it’s not as easy as it sounds.

Social Insurance: Buying in Bulk

The problem with on-your-ownership is a thing called a risk pool. Consider health care: When a government program like Medicare insures millions, prices can be kept low because actuaries know that only a small portion of the pool members will require hugely expensive treatment. But as a lone individual, solely responsible for your health care, you can’t buy into a big risk pool like that.

You can buy into a smaller risk pool—a private health insurance plan. But because of their smaller size, private insurance providers and medical institutions must protect themselves against the calamity of too many of their claimants suddenly needing costly care. To cover this possibility, they jack up prices. If big costs occur, they are ready; if not, they make enormous profits. It’s a win-win for them, but not for you. In cases like this, government can spend your money for you more efficiently.

Every red-blooded Costco shopper knows the value of buying in bulk; in effect, that’s what government does when it comes to health care. Moreover, a big insurer like the government has the clout to negotiate prices, and you don’t. That’s why other countries with universal health care can cover everyone at much less cost and with consistently better outcomes.

Being insured against the vicissitudes of life is an important stress reliever and contributes mightily to happiness. When we asked random individuals about what the good life means to them, one young college student responded quickly: “Everything stable, nothing burning down financially,” she said.

Indeed, security is an essential component of the greatest good. An economy designed to make people happy should make people feel more secure, financially and otherwise, over time. Ours does not.

Children at Risk

For too many Americans, insecurity starts in childhood.

A startling report, Homeland Insecurity, by the Every Child Matters Education Fund,4 pointed out that as of 2007 (before the current recession made things even worse), 8 million American children were without health insurance, nearly 2 million had parents in prison, and 13 million lived in poverty. More than 3 million were abused and neglected each year. The United States’ child abuse death rate is the highest among rich countries, three times as high as Canada’s and eleven times as high as Italy’s. According to the report, the effects of child abuse cost American taxpayers more than $100 billion annually.

The report suggests that American children don’t share “homeland insecurity” equally. Ailis Aaron Wolf, analyzing the report in the Boston Edge, writes,

Living in a “red” state appears to be more hazardous to the health of millions of American children … The factors weighed in the “Homeland Insecurity” ranking include such diverse indicators as inadequate pre-natal care, lack of health care insurance coverage, early death, child abuse, hunger and teen incarceration. Based on a diverse range of eleven child-related statistical measures, nine of the ten top states with the best outcomes for children today are “blue” states.5

Those states included Wisconsin, Iowa, New Jersey, Washington, Minnesota, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Vermont, and top-ranked New Hampshire, with Nebraska being the sole “red” state in the group.

Blue states were defined as those that voted Democratic in the 2004 presidential election, while red states voted Republican. All ten of the states with the worst outcomes were “red” states: Wyoming, Georgia, Arkansas, Alabama, South Carolina, Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Louisiana, and, in last place, Mississippi.

According to Michael R. Petit, the former commissioner of Maine’s Department of Human Services and lead author of Homeland Insecurity:

The bottom line here is that where a child lives can be a major factor in that youth’s ability to survive and thrive in America. The reason why this is the case is no mystery: “Blue” states tend to tax themselves at significantly higher levels, which makes it possible to reach more children and families with beneficial health, social and education programs. “Red” states overwhelmingly are home to decades-long adherence to anti-government and anti-tax ideology that often runs directly contrary to the needs of healthy children and stable families.6

“Blue” states also tend (with significant “red” exceptions, such as egalitarian Utah and the Dakotas) to have much smaller gaps between rich and poor, a subject we return to in chapter 7. They generally score higher in such key measurements of quality of life as life expectancy, educational levels, and freedom from violent crime, often approaching and sometimes even surpassing western European levels of success.

Risk Shifting

But America’s risks don’t end in childhood. In fact, the United States today is a far less secure place economically than it was a generation ago, thanks to what the Yale political scientist Jacob Hacker calls “the great risk shift.”7 Hacker points out that “over the past generation, the economic instability of American families has actually risen much faster than economic inequality” (italics his).8

Where the laissez-faire economist Milton Friedman once claimed that cutting back government left Americans “free to choose,” Hacker contends that they have become free to lose instead, as a result of “a political drive to shift a growing amount of economic risk from government and the corporate sector onto ordinary Americans in the name of enhanced individual responsibility and control.”9

Here are some of Hacker’s gleanings from government data.

• Personal bankruptcies rose from less than three hundred thousand per year in 1980 to more than 2 million in 2005. (Half of the bankruptcies result from medical bills as companies cut back on health insurance.)10

• During the same period, mortgage foreclosure rates quintupled. (They are even higher now after the 2008 crash.)11

• Eighty-three percent of medium and large employers offered defined benefit plans in 1980. “Today,” Hacker points out “the share is below a third.” Defined benefits, such as pensions, provide a guaranteed level of payment when eligibility begins, as opposed to defined contribution plans which may be lost in the stock market. Defined benefits are inherently less risky for the recipients. (We provide more details on benefit plans later in this chapter.)12

• By 2005, the number of Americans worried about losing their jobs was triple what it was in 1980. (Sadly, many were right and lost their jobs in 2008.)13

• In 1970, only 7 percent of American families saw their income fall by more than 50 percent due to layoffs or other factors. Thirty years later, the figure was 17 percent.14

These last points are particularly significant. Losing something brings greater long-term reduction in happiness than gaining something adds to happiness. In general, people understand this and are “risk averse.” According to a George Washington University survey, Americans are not exceptional in this respect: By a margin of more than two to one, they favor stability of income over risky opportunities to make more.15 Yet despite such preferences, there has been a constant push to increase the economic risks of ordinary Americans in return for a shot at the golden basket. The result is a few big winners, but a multitude of losers, or at least people whose fortunes are ever more precarious.

Does Security Mean Greater Unemployment?

In general, the social safety net for working people is tighter in the capitalist democracies of western Europe than in the United States, where a tuna might easily slip through. Rates of poverty are lower by about half; the rich-poor gap is far smaller (more on this topic in chapter 7); all Europeans in every country are covered by national health insurance; retirement pensions are more available, more secure, and more generous; and unemployment and welfare benefits usually extend for longer periods. Europeans call their more generous welfare approach the social contract.16

Since the 2008 recession began, American and European unemployment levels have been similar, though levels in Europe generally have not risen as much as in the United States. In Germany, they actually fell. But before that, official unemployment levels in western Europe were higher than in the United States, especially in the larger countries. American conservatives charged that the social contract and more rigid rules protecting labor rights were responsible for the earlier gap and that greater job security here would actually lead to more unemployment as in Europe. But even before the crash, this argument was flawed; U.S. unemployment figures were systematically underreported.

Since early in the Clinton administration, the official unemployment rate in the United States has not included those workers who give up looking for a job. Even earlier, in the 1980s, an underclass of Americans, with few skills or opportunities for employment and without support from the welfare system, turned to illegal activities such as the sale of drugs. Many of them are now behind bars and also not counted in the unemployment figures. Counting those who have given up looking for work, and our prison population, would actually have added at least two points to the official unemployment rate, bringing it roughly to European levels even before the recession.

In their book, Raising the Global Floor, Jody Heymann and Alison Earle examine the impacts of generous social benefits for workers on unemployment rates.17 Comparing the world’s richest countries, they find no correlation between stronger safety nets and greater unemployment. It is true, as some conservatives argue, that in several European countries, especially Germany and France, rigid labor rules make it hard to fire or lay off workers. In such cases, employers may be more reluctant to hire. But it’s not impossible to provide greater security for workers and flexibility for businesses under the social contract model.

Here, the world’s happiest country points the way forward. The Little Mermaid in Copenhagen harbor knows a secret or two.

Flexicurity

Since as far back as 1899, the Danish government has provided generous benefits to its workers. But by the 1970s, high wages had made Denmark uncompetitive in foreign markets and led to balance-of-trade deficits and inflationary pressures. Yet austerity programs to cut wage demands and increase savings met strong public opposition, including repeated strikes and the frequent collapse of ruling coalition governments. High unemployment and harsh economic conditions followed, exacerbated by the 1970s energy crisis. Danish unemployment continued to rise, and Danish businesspeople complained of difficulties in remaining globally competitive until 1994, when the Danes first introduced their flexicurity model for the labor force.

Today, Denmark has one of the most competitive economies in Europe and one of the lowest unemployment rates in the world, while guarding and even improving its strong safety nets. In 2009, the European Council reported that “flexicurity is an important means to modernize and foster the adapability of labor markets.”

The Danish concept of flexicurity rests on three legs.

1. Flexibility in the labor market. Danish businesses are given great leeway in hiring and firing workers. Regulations for starting businesses are relaxed. In 2008, the conservative Forbes magazine ranked Denmark as the number one country in the world for business. The equally conservative Heritage Foundation ranked it ninth, just below the United States, with this comment: “The non-salary cost of employing a worker is low, and dismissing an employee is relatively easy and inexpensive.”

2. A strong social safety net. Though it’s not hard for businesses to lay off or fire workers in Denmark, dismissed employees enjoy excellent benefits during periods of unemployment. They can be covered by unemployment benefits nearly equal to their previous salaries for two years or more. During this period, they receive thorough assistance in finding new work. After that, if they cannot find a job, they are offered one by the government. They must take it or lose their benefits. But such make-work jobs are rarely needed; most Danes find regular reemployment long before benefits run out.

3. Lifelong training. During periods of unemployment, Danish workers receive extensive training in new skills to make sure they are employable and to prepare them for technological changes in the economy.18

Thus flexicurity provides relief to employers from rigid labor rules and, at the same time, supplies income security, job-finding assistance, and useful education for employees. All of this does not come cheaply, however; the Danes pay among the highest taxes in the world, and of all rich countries, the percentage of GDP produced by the public sector is highest in Denmark. On the other hand, wages in Denmark are very high, with even the lowest-paid workers earning the equivalent of about twenty U.S. dollars per hour in 2010.19

Trust

With Denmark’s high degree of social solidarity, reflected in its strong social contract and support for working families, Danes, along with citizens of other Nordic countries (Sweden, Finland, Norway, and Iceland), are among the most likely people on Earth to trust their fellow citizens. The sense that “most people can be trusted” enormously increases personal feelings of security.

The focus on equality in Nordic countries discourages status and consumer competition and encourages concern for community well-being. As a Republican state senator once told John, she discovered during a trip to Norway the feeling that “everybody isn’t trying to get filthy rich.” The Nordic “we’re all in this together” ethic leads to a high valuation of honesty and sharing. Nordic countries understand the importance of both trust and generosity in improving levels of happiness.

Research shows the Nordics have good reason for their high levels of trust. Wallets filled with money left deliberately on streets in Nordic countries are more likely to be returned intact than anywhere else in the world, and residents know this. In surveys, they are more likely to say they expect their wallets and money to be returned than people elsewhere, about twice as likely as Americans, for example.20

But if trust and generosity are important contributors to happiness, unemployment most assuredly is not. Happiness researchers find that the loss of a job hurts far more than the drop in income alone. Productive work, with reasonable work hours, contributes greatly to self-esteem. That esteem takes a big hit when a job is lost. Not even the Danes can prevent job losses, but they view unemployment as an economic and social, rather than personal, failing. The social support and educational opportunities the Danes provide to their unemployed help to strengthen laid-off workers’ sense of self-worth and minimize the blow to personal well-being.

Work-sharing or Kurzarbeit

Yet policies like those in Denmark are not as effective in maintaining well-being as programs that actually prevent the job losses in the first place. Perhaps the most successful strategy, especially in recessionary times, is the idea of work-sharing. In his inaugural addresss, President Obama congratulated workers who freely chose shorter hours and lower pay in order to prevent fellow workers from being laid off during the recession. But words are one thing and actions another. Obama might have done more by actively promoting a policy initiative pioneered in Germany.

The economist Dean Baker, director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, argues that any further economic stimuli to reduce unemployment should include Kurzarbeit, or “short work,” a German policy that encourages employers to reduce hours rather than lay workers off when times are tight, by making unemployment funds available even when workers do not lose their jobs.21 Instead of cutting 20 percent of its workforce, a German company might reduce each worker’s load by a day. Unemployment benefits kick in for the reduced work-time, so workers earn roughly 90 percent of their former incomes for 80 percent of the work.

Other countries have followed suit, and a bill sponsored by Democratic senator Jack Reed of Rhode Island and Democratic representative Rosa DeLauro of Connecticut would allow federal unemployment benefits to be used to top off salaries of reduced-hour workers in the United States. (Some seventeen states already allow this with their own unemployment dollars but cannot use federal unemployment funds to support such policies.) The business Web site 24/7 Wall St. ranked the idea number two in a recent editorial, “The Ten Things the Government Could Do to Cut Unemployment In Half.”22

When the bill was discussed in Congressman Barney Frank’s House Financial Services Committee, Dean Baker testified in favor—no surprise since he’s a liberal—but so did Kevin Hassett, an economist with the conservative American Enterprise Institute. Hassett pointed out that even though the German economy tanked like ours did in 2008, Germany’s unemployment rate didn’t rise—thanks to Kurzarbeit. The law allows companies to retain workers instead of having to rehire later, he said. It’s good for them, good for the workers, and doesn’t really cost any more than traditional unemployment payments. It’s a win, win, win. Nonetheless, not a single Republican has supported the Reed/DeLauro bill and not all Democrats do either, so it remains in limbo.23

Good-bye Golden Years

As noted earlier, we Americans aren’t living as long as we could. However, we are living longer than we used to. Currently, we can expect ten years of retirement or more. But the security of that retirement is increasingly under threat.

In 2010, Social Security, perhaps the most popular of all government programs, celebrated its seventy-fifth anniversary. Most Americans can still expect to receive Social Security when they retire, but that money only goes so far, making up 30–40 percent of the income lost upon retirement. Retirees have had to supplement their Social Security with private pensions.

After World War II, most companies and government agencies began putting people on pension plans, deducting a small amount from their salaries to ensure a defined benefit payment after retirement. As with Social Security, working Americans had a good idea of how much they’d receive from their pensions.

In 1974, Republican senator Jacob Javits introduced the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. Its passage insured privately financed defined benefit plans and guaranteed that workers would receive their full pensions when they retired. ERISA was a law workers could applaud. With it, they felt far more secure. Only a generation ago, 80 percent of Americans could count on defined benefit plans to provide for them in old age. Today, less than one third of workers are covered by such plans.24

More of them now have 401(k) plans, which make defined contributions into pension plans that are invested in the stock market and rise and fall with it. An early hallmark of the Ownership Society, such plans were lauded as giving workers more control over their retirement and more opportunity to strike it rich as the stock market climbed in value.

But, as Jacob Hacker points, out, the plans were “dirt cheap” for employers, whose contributions to them were cut drastically from what they had been under the defined benefit plans. And the plans were risky. Sometimes, as in the case of Enron and WorldCom, the money was invested in the company’s own stock. When these companies went belly up, workers saw near total losses of their pension savings. Hacker tells of one WorldCom employee who built up almost $1 million in his 401(k). After WorldCom’s bankruptcy, precipitated by the illegal activities of its CEO, the employee received a final retirement check for $767.14!25

Worse yet, as defined contribution plans became the rage, fewer companies offered any pension plans at all. And cutbacks in Social Security benefits actually resulted in an 11 percent drop in retirement wealth for the median family between 1983 and 1998, a time when the stock market was soaring.26 During the same period, the American personal savings rate fell from more than 10 percent of take-home incomes to less than 4 percent. Today, at least 60 percent of American families feel unprepared for retirement. Millions more are overly optimistic about their own retirement prospects, not accurately estimating the amount of money they’ll need when they stop working.

Michael Pennock, the statistician from the Vancouver Island Health Authority who developed Bhutan’s happiness survey, recently returned to Canada from a visit to the Oregon coast. “It’s just amazing for us Canadians to see the number of senior citizens, some of them very old, who are working as clerks at Walmart or McDonald’s or other stores in the United States. You don’t see that here in Canada. People that age have pensions to provide for them.”27

Despite all this, when President George W. Bush announced his plans for the Ownership Society in 2004, a key plank was the privatization of Social Security. Conservatives claimed the Social Security system was near financial collapse, even though it was running a surplus that Republicans wanted to draw from to finance new tax cuts. Bush advocated shifting Social Security contributions into 401(k)s. Fortunately, public opposition stopped the idea in its tracks. We can only imagine what the retirement situation would look like for millions of Americans had their Social Security contributions evaporated in the stock market crash of 2008. But that hasn’t stopped the Right from continuing to advocate privatization.

Social Security Plus

Steven Hill, the author of Europe’s Promise, suggests an alternative that in our opinion would do far more to enhance the greatest good for the greatest number over the longest run. He believes that because defined benefit pensions are disappearing and other sources of savings such as home values and stock ownership have proven notoriously unstable, we must actually strengthen Social Security so that it pays more, not less, as many budget cutters have advocated.28

Hill says we should double Social Security benefits from about one third of annual income upon retirement to about two thirds, or roughly the European benefit level. He points out that 40 percent of Americans depend on Social Security for 84 percent of their retirement income. Even the top 40 to 20 percent of income earners depend on Social Security for a majority of their retirement income. Only the richest 20 percent can get along without it.

Hill’s idea—he calls it Social Security Plus—would cost $650 billion a year, not chump change. Some revisions would be needed to keep Social Security performing effectively and securely in the black, while expanding its payout. The most obvious is to lift the cap on required contributions. Currently, Americans only pay Social Security taxes on up to $106,000 of their earnings, and none at all on income derived from interest and dividends. Collecting the Social Security tax on all incomes would bring in about $377 billion a year in added revenue and make possible improved Social Security payouts while helping ensure the system’s health for many more years.

Moreover, Hill points out that if Social Security payouts were roughly doubled, those employers who do provide pensions would no longer need to do so. Currently, corporations receive $126 billion a year in tax deductions for these provisions, money that could go into the Social Security system. He also suggests eliminating some other tax deductions that overwhelmingly benefit wealthier taxpayers. Together, Hill says, “these three revenue streams would raise 100 percent of the revenue needed for doubling the payout of Social Security Plus.”

Hill believes his plan would be fairer and more secure while making retirement benefits fully portable and eliminating a benefit provision that actually does make American companies less competitive. We agree.

Winding Down Work, Winding Up Retirement

Typically, Europeans retire earlier than Americans do, and on a much larger percentage of their previous salaries—about 67 percent, according to the OECD. Indeed, their situation is so generous that it has become too costly even for the European welfare states, some of which must provide five or ten more years of retirement benefits for workers than we do, since their citizens retire earlier and die later. Moreover, in Europe, even more than in the United States, an ever-larger group of seniors means greater demands on a smaller population of younger workers. So efforts to reduce pensions and increase the retirement age are at the top of the conservative agenda in Europe and have been passed in Germany and the Netherlands, though not yet in France, where thousands filled the streets to protest a raise in the retirement age from sixty to sixty-two.

But in our view, an economy concerned with the greatest good over the longest run would consider more creative solutions to this dilemma. Surely, the most reasonable is phased retirement. Instead of having workers fully retire at sixty or sixty-five or seventy, we should encourage them to retire in stages, with a larger portion of their retirement benefits kicking in at each stage.

They might first reduce work by one day a week, then in a couple of years, by two days a week, and so forth. Or their vacations might be lengthened—to two months, four months, six months, and so on. With workers in all countries living longer and in many cases staying fit longer into their lives, there is no reason they should be completely retired so early. Initially, this might cause some workflow confusion, so it will require some advance planning, but many companies and universities have found ways to do this effectively.

Partial retirement allows workers to stay attached to what is meaningful in their jobs and to the co-workers who are often their best friends. It allows room to be opened for younger workers to enter the company and the opportunity for older workers to mentor them. It allows older workers to find more time for exercise at an age when they need it most and to make new friends and find new hobbies outside the workplace. It can reduce financial pressures on the retirement system, be it Social Security or other pensions.

It is not for everyone—some workers can’t wait to leave their workplaces completely, especially those “used up” by hard labor. But such an idea has wide appeal, and many businesses and institutions such as universities already take advantage of it. Targeted government incentives, including changes in tax policy and Social Security take-up rules, could spur greater use of phased retirement.

Incarceration Nation

Here’s some good news on the security front. Rates of crime in the United States have mostly been falling over the past generation, despite what chronic television news viewers believe. Indeed, some crimes of theft, such as pickpocketing, are more common in European cities than here.

On the other hand, rates of violent crime in America are among the highest in industrial countries, and the United States has the dubious distinction of leading the murder-per-capita pack by plenty. Indeed, Americans are about five times as likely to be murdered as residents of other rich countries.29

Availability of guns and a different cultural attitude toward their use may have something to do with the mayhem we’re subjected to. So passionate are some about their guns (and so beholden are their politicians to the National Rifle Association), that we watched with a yawn while Oklahoma senator Tom Coburn attached a rider to a recent credit card oversight bill overturning nearly a century of law and allowing visitors to our national parks to carry loaded and concealed weapons, an idea considered crazy by almost everyone who works for the National Park Service, including Fran Mainella, former director of the NPS under George W. Bush.30

By contrast, the same Congress still feels no need to mandate any paid vacation time so Americans can actually visit their parks. (More on this in chapter 6.)

One answer to the murder rate, say conservatives, is the death penalty. On June 17, 2010, the state of Utah shocked the Western world when it executed a prisoner by firing squad. Texas, whose license plates might well read THE DEATH PENALTY STATE, has lethally injected 460 alleged murderers since 1982. The United States is alone among industrial countries in using the death penalty. But the results, as alluded to above, are less than stellar. Threat of death is no deterrent: Murder rates in America are actually highest in death penalty states.31

The decline in overall crime in the United States comes in part from a change in demographics: fewer Americans are in the age bracket most likely to commit crimes. But to be fair to the conservatives, it may also stem from the fact that we’ve locked so many people up.

“Never in the civilized world have so many been locked up for so little,” reports the Economist magazine. Home to about a quarter of all the world’s prisoners, the United States now holds 2.3 million people behind bars, more than half of them nonviolent offenders. The “war on drugs” and a flurry of “three strikes and you’re out” legislation have resulted in a 500 percent increase in the prison population in the last three decades.32 According to the Homeland Insecurity report: “Imprisonment has become a costly and ineffectual substitute for addressing substance abuse, poverty, mental illness, and educational failure. It also jeopardizes the life chances of millions of children who have a parent in prison.”33

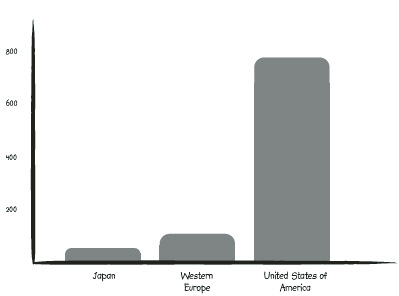

The United States locks up people at twelve times the Japanese rate, nine times the German rate, and about seven times the European rate overall, with about 750 prisoners per 100,000 Americans.34 Free meals, free rent, free health care. It would be cheaper to put them all through college. Black males account for 44 percent of all U.S. prisoners, despite making up only 6 percent of our population. They wind up in prisons four times more often than black males did during the height of South Africa’s apartheid regime.35

By contrast, many European countries have actually been shedding prisoners in recent years. France has fewer than it did in 1980, and in the Netherlands, the number of prisoners has fallen so fast, the Dutch had to close eight prisons and would have had to close more if they didn’t import a few prisoners from Belgium. Forty percent of criminal trials in the Netherlands end up with community service rather than jail.36

The upside to the American “lock ’em up” approach is that some communities now survive on their prisons and spending for incarceration boosts the GDP significantly. When John spoke a few years ago at Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, Texas (population 35,000), he was surprised to find that the college employed nearly half the people in town, and Huntsville’s eight (!) prisons—from minimum security to death row—employed most of the rest. The click of prison keys means the ka-ching of cash registers. In the upside-down world we inherit, more jails mean more GDP.

Global Security

For a couple of decades, especially during the 1980s, American insecurity centered on fear of domestic crime. It was almost an obsession, and politicians built careers on exploiting such fear. But ever since September 11, 2001, much of America’s insecurity has been redirected toward fear of foreign terrorism. Increasingly, the world is a scary place—will Iran get the bomb; will the Taliban poison our water supply?

The United States’ response to all of this is what you might call a Dirty Harry foreign policy. Americans will protect themselves through the use of overwhelming force, even, as they’ve discovered, against people who never harmed them in the first place. The United States has had troops in Iraq since 2003, and the war in Afghanistan is now the longest in U.S. history. Our nation has bases in dozens of other countries, including places like Okinawa, Japan, where the locals have long demanded that the Americans go home. All of these bases cost a bundle.

The current U.S. “defense” budget stands at nearly $700 billion a year (about the cost of Obama’s stimulus package) and consumes over 20 percent of its total federal budget.37 A portion of this money is actually spent for weapons even the Pentagon says it doesn’t need. Direct costs for the Iraq and Afghan wars now exceed $1 trillion.

Ironically, many Republicans, who now recoil in terror at the prospect of deficit spending, never complained when Bush (and Reagan before him) massively increased war spending while slashing taxes for the rich, a one-two punch that produced the greatest deficit increases in American history. “Deficits don’t matter,” Vice President Dick Cheney said then. Now, apparently, they do. But advocating defense cuts to decrease the deficit is likely to get you called a traitor.

In his final speech as president, one such traitor, former general Dwight D. Eisenhower, warned us to beware the increasing power of the “military-industrial” complex and to consider that dollars spent on weapons came from the mouths of the hungry.38 They still do.

A few years ago, John produced Silent Killer, a television documentary about ending world hunger. While researching the film, he learned that thirty thousand children die of hunger and hunger-related diseases every day, one every three seconds. This is a daily holocaust—ten September 11s every day. Experts say the hunger crisis could be ended completely for as little as $13 billion a year, less than what the U.S. military spends in one week.39

We know that generosity is an important contributor to happiness and that a world without poverty-stricken, desperate people, whose children die before the age of five, would be a safer world. A true national security policy would look to repairing a broken world where anger and resentment fester. It would transfer a significant portion of the dollars spent on bombs and guns to the provision of safe and adequate food, clean water, and the control of disease. It would seek the greatest good for the greatest number over the longest run.

For Americans ever to feel truly secure, they must build a world that is secure for all humans. But right now, as we have seen, it’s not even secure for all Americans.