CHAPTER 7

The fact is that income inequality is real—it’s been rising for more than 25 years.

—PRESIDENT GEORGE W. BUSH, 20071

So far in this book, we’ve explored the concept of the greatest good. It’s time now to consider the second leg of Gifford Pinchot’s stool: the greatest number. What do you think that means? For political economists like Jeremy Bentham and the Utilitarians as well as for Pinchot, the greatest number came from a notion that in a good society, the good things would be broadly distributed so that as many people as possible could enjoy them. This was harder in poor societies, where even necessities were in short supply and comforts or luxuries almost nonexistent. But in wealthy societies like our own, it is materially possible for the great majority of people to have access to a quality of life far beyond subsistence.

The concept of the greatest number is really about fairness, the moral sense that everyone has reasonable and similar access to the good things in life. So how do we know if a society is fair, if our own society is fair?

Well, first of all, we can look at the gap between rich and poor in any society. Let’s put this one in simple terms: the gap between rich and poor in America is the widest in any industrial country; wider even than in poor Latin American nations like Guyana and Nicaragua.2 And that chasm is getting wider all the time. Despite continued economic growth, poor and middle-income Americans have seen little if any increase in their real purchasing power for the past three decades, while the incomes of the richest Americans have skyrocketed. A rising tide of GDP was supposed to lift all boats; it instead floated the yachts and swamped the rowboats.

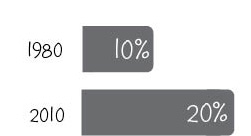

In 1915, when Wilford King at the University of Wisconsin estimated that the richest 1 percent of Americans earned 15 percent of national income, the country reacted in shock; now we seem to yawn at a wider gap. Here’s how big it has become: In 1980, the richest 1 percent of Americans earned less than 10 percent of the national income. By 2008, they were earning more than 20 percent of the national income; indeed, they earned more income than the bottom 50 percent of Americans all put together.3

The top 20 percent of Americans earn fourteen times as much as the bottom 20 percent, up from eight times as much in 1980. Despite productivity gains of 80 percent since 1972, the median American worker in 2008 earned only eighty-three cents for every dollar he or she earned then. During the same period, average CEO pay increased from being thirty-five times that of the average worker to as much as four hundred times as great.4

There’s a problem here: Traditional free-enterprise economics suggest that the marketplace works well because people vote with their dollars. This so-called consumer sovereignty supposedly ensures that the market democratically produces what people actually need and want. But in our schoolrooms, we learned that democracy meant “one person, one vote.” In the marketplace as it currently stands, those CEOs have 262 votes for every one their workers have. The poor might need apartments or buses or health care, but they don’t have the “votes.” So we get a run on private jets, yachts, and $5,000 handbags.

Economists use what they call the Gini coefficient to determine relative equality among nations. Absolute equality of incomes is represented by a zero, absolute inequality by a 1 (that would mean that a single individual earned all of a country’s income). Since 1980, the U.S. Gini coefficient has risen from 0.388 to 0.45. America’s Gini rating of 0.45 contrasts sharply with the ratings in much more egalitarian countries: 0.23 in Sweden, for example, very high 0.2s and low 0.3s in most of Europe and Japan. In other words, the distribution of income in the United States is about twice as unequal as in Sweden.5

Ignoring Louis Brandeis

That’s income. The gap in wealth owned by Americans is even greater. Back in 1977, John made his first documentary film, A Common Man’s Courage. It was the story of John Toussaint Bernard, an immigrant from Corsica who came to the United States at the age of twelve in 1905. A tiny man, but tough and sinewy, with magnetic oratorical powers, Bernard had tried to start a union in Minnesota’s iron mines. He was fired and blacklisted. Later, he became a New Deal–era congressman, elected as a candidate of the populist Farmer-Labor Party, which later merged with Minnesota’s Democrats. In most of Bernard’s many speeches throughout his life, he quoted the late Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis: “We can have democracy in this country or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we cannot have both.”6

You are free to decide for yourself whether Brandeis was right, but one thing is certain: the United States has concentrated great wealth in the hands of a few, more so than in any other industrial nation and more than at any time since the late 1920s. Consider the following facts.

• The United States has a far greater percentage of people living in poverty than any other industrial nation.

• In 1960, the top 20 percent of the American population owned thirty times as much wealth as the bottom 20 percent. Now they own seventy-five times as much.

• By 2001, the top 1 percent of Americans owned forty-four hundred times as much wealth per person as the bottom 40 percent!7

• By 2005, the top 20 percent of Americans earned 47 percent of our national income and owned 84 percent of its wealth.8

Our inequality falls particularly hard on certain groups of Americans. For example, the median white family in America owns eleven times as much wealth as the median black family. At the time of the civil rights movement, black Americans were 1.6 times more likely to die in childhood than whites. Today, a black child is 2.4 times more likely to die.9 The good news: in 1968 black Americans earned fifty-five cents for every dollar that whites earned; by 2001, they were earning fifty-seven cents for every dollar. Progress?

Share of Total U.S. Income Received by Top 1 Percent of Americans

Women are in a similar position: a single twenty-something woman working full-time earns 90 percent of what her male counterpart earns. Sounds good, but when the gender expert Joan Williams of the University of California compared all women’s income with men’s, she found that they earn only fifty-nine cents for every dollar earned by men.10

Americans are not unaware of this inequality in wealth. According to a 2007 Pew poll, 73 percent believe that “today it’s really true that the rich just get richer and the poor just get poorer.”11

Who Won the Class War?

Some would keep it that way. In 2008, at a presidential campaign stop in Toledo, Ohio, Barack Obama was confronted by one Samuel Wurzelbacher, also known as “Joe the Plumber.” Joe challenged Obama’s advocacy of higher taxes for the richest Americans. Obama replied that in his view we’d all be better off if we “spread the wealth around,” by ending income tax cuts for the very rich. In fact, though Obama retreated from his position, the evidence (which we’ll get to later in this chapter) shows that he was actually right.

But Joe, and the right-wing radicals for whom he became a hero, screamed loudly that spreading the wealth around was socialism, and Obama was a socialist, and we all know what that means. It’s a word meant to scare the daylights out of us.

Obama has called for a slight increase in the highest marginal tax rates—the richest would pay 39 percent, as they did under Bill Clinton, rather than the 35 percent they paid under Bush the Second. Some radical conservatives label Obama’s call for such a tax increase class warfare. But in fact, that has been going on for at least thirty years, during which time the wealthiest Americans gobbled up by far the lion’s share of new wealth. Warren Buffett put it simply: “Yes, there is a class war and my class is winning.”12

Equality Matters

Let’s put it plainly: In our view, growing inequality is not good for America, period. In more equal societies, everybody does better. That’s the surprising conclusion, supported by an impressive marshaling of the evidence, that Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett reach in The Spirit Level. That evidence (also presented on their Web site, www.equalitytrust.org.uk) shows that inequality exacerbates a host of social problems and that the more equal countries perform better on almost every social indicator.

Wilkinson and Pickett consider twenty-nine different areas of life, including longevity, infant mortality, mental health, crime, incarceration, life satisfaction, education, teen pregnancy, and drug abuse. And while there are some exceptions—Singapore, one of the world’s most unequal industrial nations, has its lowest infant mortality rate, for example—the general trends are unmistakable.

The United States, the most unequal of industrial nations, ranks near the bottom for every indicator except gross domestic product, while the most egalitarian countries, especially the Nordic countries, are on top. What is especially important about these findings is that in the more egalitarian countries, even the rich live longer and are more satisfied with their lives. Equality seems to be a win-win proposition. As Barack Obama told Joe the Plumber, we all do better when we spread the wealth around.

In many ways, the evidence from American states mirrors that of countries around the world. The least equal states, primarily in the South, exhibit far worse physical health, mental health, and other social indicators than more egalitarian states; rates of violent crime and homicide are much higher and children fare worse in less equal states.

In August 2010, Newsweek magazine ranked the world’s one hundred “best countries.” The rankings were remarkably similar to Gallup’s national happiness surveys. Australia and Canada joined a host of small European countries at the top of the list, while the United States came in a respectable eleventh, buoyed by its score in the category of “economic dynamism.” All of the top ten nations (Finland, Switzerland, Sweden, Australia, Luxembourg, Norway, Canada, the Netherlands, Japan, and Denmark) are relatively egalitarian, certainly much more so than the United States. With the exception of debt-stressed Iceland, all of the Nordic countries made the top ten.

The number one nation was Finland, a country which ranks near the top of happiness polls and at the top in educational success (as we will see in the next chapter). Finland ranks high in every indicator considered by Newsweek. Its economy, led by the cell phone giant Nokia, has consistently been rated one of the planet’s most competitive by the World Economic Forum. Poverty is nearly nonexistent, and the gap between rich and poor in Finland is narrow. The Finns are inwardly happy, and they are outwardly prosperous.

Finland’s Secrets of Success

The Finnish professor Hilkka Pietilä argues that it was equality that made Finland’s prosperity possible: “The common belief is that a country must first become rich, and then it can provide welfare for its people. The history of the Nordic societies tells a different story; here, wealth has been built by building welfare for people.”13

Pietilä points out that “Finland was not a wealthy country in the 1940s and 1950s.” The country was devastated during World War II—“the whole of northern Finland was burned down by the Germans”—and was forced to pay reparations to the Soviet Union after the war. Fearful of offending its powerful Soviet neighbor, Finland rejected Marshall Plan assistance from the United States and remained neutral during the Cold War.

As recently as the 1960s and ’70s, the Finns actually had a reputation for unhappiness. One segment on the TV newsmagazine 60 Minutes described them as the most depressed people on Earth. But while some Finns still do battle seasonal affective disorder and alcoholism due to their dark winters, comparing the old, poor, and morbid Finland of legend (and a fair amount of truth) with the happy, wealthy country it has become is like comparing night and day.

Led by a very active women’s movement, and a commitment to being self-reliant and sustainable as a nation, the Finns found a middle way to progress, avoiding the economic extremes of the West, but without the restrictions on freedom of the Soviets. According to Pietilä: “Despite its poverty, Finland began to create one of the world’s most generous social welfare systems. The aim was to build the economy while eradicating poverty. The aims supported each other; the growing well-being of people provided a healthy and trained labor force, and the economic growth was redistributed to people as social benefits.”

As social benefits. The Finns didn’t simply redistribute cash. Well-funded public services (including child support allowances, forty-four weeks of paid parental leave per child, defined benefit pensions, free education through university, free health care, free school meals, subsidized public transportation, free day care, and subsidized elder care, plus a high minimum wage and generous unemployment benefits) helped create the world’s largest middle class (as a percentage of the population) and a skilled workforce. Finland is one of only two countries that have outlawed compulsory overtime, and Finns have the world’s longest paid vacations. Yet they are remarkably productive. Pietilä continues:

The welfare system here is a lifelong social insurance, a guarantee that whatever may happen, children will not lose access to education, people will not be left at the mercy of relatives or charity organizations, no one will be abandoned in case of illnesses, accidents, unemployment or bankruptcy, and everyone will have old-age income and care no matter what … This success was built on a notion of welfare entirely different from welfare as understood in the United States. In the US “being on welfare” is humiliating, and welfare benefits often depend on the recipient’s relationship to something or someone else. What is radically different about the Finnish system is that here welfare benefits and services are rights that everyone living permanently in the country is individually entitled to.

Healthy and well educated, the Finns are highly productive when they work. But they value families and leisure; the sauna is never far away, nor are the tiny cabins where they relax during summer holidays. But being the “world’s best country” doesn’t come cheap. “Finland has financed its welfare system mainly through highly progressive taxation on salaries and wages,” writes Pietilä.

Is Small Size Key to Nordic Success?

Moderate American conservatives do acknowledge Nordic success. But they write it off as simply the result of countries like Finland being small and homogeneous. “Can’t work here, not in a big and diverse country like ours,” they say. Case closed. Or is it?

It’s true that Finland, Sweden, and Denmark are small countries and, until recently, have seen little ethnic or racial diversity. There is some evidence that due to the persistence of racism, homogeneous societies find it easier to cooperate, and harder to scapegoat immigrants or other “others” for economic failures. Yet these nations also lack some of the advantages enjoyed by the United States and other larger countries.

Americans often hear that the United States is a victim of globalization, the race-to-the-bottom supposedly required by the integrated economy of Thomas Friedman’s “flat” world. But countries like Finland are far more susceptible to globalization’s threats. The United States has an immense domestic market—86 percent of its products are sold at home. The economist John Schmitt points out that European and Japanese companies open plants here simply to save transportation costs in selling to the American market. But the Nordic countries have small domestic markets, so far more of their production must be sold abroad. They have to be competitive to do that. According to the World Economic Forum, they are. All rank in the top twenty among the world’s “most competitive” countries (those whose products compete most effectively on the world market), and Sweden ranks ahead of the United States.14

The Nordic nations must import many resources since they have few of their own—Norway’s oil is an exception. They are cold and dark much of the year, requiring more energy for heating and lighting. They speak languages no one else speaks, so they must learn English, or perhaps German, to be understood in global commerce. They have smaller populations than even many American states, so they have smaller risk pools to share the uncertainties of insurance.

Instead of racing to the bottom, these countries have raced to the top, creating healthy economies on a base of social welfare—or, as Steven Hill calls it, workfare—that, according to advocates of American-style capitalism, should leave them unable to compete.

The “T” Word

It’s tempting to say that greater equality and a stronger social safety net and all of those things folks like the Finns take for granted may sound appealing, but there’s no free lunch. Those things cost money, and the United States doesn’t have any. It’s broke. Its states are broke: California is offering IOUs to its workers. Hawaii is dramatically shortening its school year. Michigan is ripping up its paved roads and turning them into gravel because it can’t afford to maintain them. U.S. cities are broke: Colorado Springs, for example, just turned off a third of its streetlights. The federal deficit is frightening. How can Americans possibly pay for this stuff ?

First of all, it’s probably unnecessary to mention that Germany, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, and other such countries provide these things even though their per capita GDPs are smaller than America’s. They fund them and create their livable societies in no small part through higher taxes than we pay here and through a different mix of taxes.

It is necessary to point out federal tax bills for Americans are now at their lowest level since 1950. Americans pay an average of 9.2 percent of their incomes in federal taxes, only three quarters of the average for the past half century.15 In the era BR (Before Reagan) many Americans understood that, as the great Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes put it, taxes were the price of civilization. Taxes were seen as investments in our future. Taxes allowed for social insurance, allowed us to buy that insurance in bulk, provided the services the market did not deliver, and provided them well. (More about this in chapter 10.) Today, we are conditioned to think of taxes as burdens and their elimination as relief.

As the linguist George Lakoff points out, these are loaded words; from the beginning the concepts of the tax burden and tax relief create an ideological frame—taxes are a bad thing, and the less of them the better. All too often, even progressives fall into this language trap. They announce that they will provide middle-class tax relief. And indeed, though it may sometimes be helpful to reduce taxes, this is far from always the case.

Most Republicans in Congress want more tax cuts for the rich, who, they say, pay all the taxes while lower-income Americans pay none. This is simply nonsense: Lower-income Americans may pay little or no federal income tax, but their share for payroll, property, excise, and state and local sales and other taxes is actually higher as a percentage of income than that of the rich.

The top 1 percent of American income earners pay about 29 percent of their incomes in taxes, while the bottom 50 percent pay 24 percent of theirs. Warren Buffett points out that his secretary actually pays a higher percentage of her income in taxes than he does.16

Here is the overal breakdown.

• Federal income tax. The top 1 percent pay 22 percent of incomes. The bottom 50 percent pay 3 percent.

• State and local taxes. The top 1 percent pay 5 percent; the bottom 50 percent pay 10 percent of their incomes.

• Social Security. The top 1 percent pay 2 percent of incomes; the bottom 50 percent pay 9 percent.

• Other taxes. The top 1 percent pay less than 1 percent; the bottom 50 percent pay 2 percent.17

Tax cuts at the top in no way guarantee an increase in jobs. Indeed, American businesses earned their highest quarterly profits in history in 2010, while making almost no effort to reduce unemployment. Businesses invest and produce not simply because they have money to do so, but because there is effective market demand for their products. The rich spend far lower percentages of their money to create such demand. Indeed, it is jobs, including government jobs—and the wealth they share—that create jobs, because workers spend most of their discretionary income and create more effective demand.

In the two years following the economic collapse of 2008, the top five hundred American corporations saw a large increase in profits, and by 2010, were actually sitting on $1.8 trillion of new wealth. But instead of adding jobs, they cut them.

The subject of what kind of taxes work best is huge and complicated, and we cannot do it justice here. Because of frequent changes in parts of the economy, a “diversified portfolio” of taxes is most reliable, as is diversity in stock holdings. There are some lessons to learn from others countries about taxes.

• In many European countries, corporate income taxes are lower in principle than in the United States, but they are more consistently collected; here, loopholes allow many companies to escape taxation entirely. For example, the largest U.S. company, General Electric, paid no taxes in 2010 on a profit of $14 billion.18

• Personal income taxes in Europe generally have higher top marginal rates than in the United States and fewer loopholes for the wealthy.

• Value-added taxes (VAT) play a major role in European tax systems. They are similar to sales taxes. Whenever you buy something in a European country, the price already includes the VAT, which has been paid at each level in the production of a product. For example, VAT would be paid on the raw materials and machinery used to make a car, on the car itself when it goes from manufacturer to dealer, and again when it is sold to the final customer. Such taxes are very hard to evade so they produce consistent revenues. They are sometimes kept lower on necessities and higher on luxuries—serving as what the economist Thomas Frank calls a progressive consumption tax. Dave and John do not completely agree on the usefulness of VATs. Dave believes that like sales taxes, they are regressive and fall more heavily on the poor. John agrees that this is true, but believes they serve a positive purpose because they ensure that everyone who consumes contributes to social investments. And the poor are the greatest beneficiaries of what the VATs make possible—free health care, higher education, transportation subsidies, housing subsidies, and so forth—because they are least able to pay for these things in the market.

• Property tax revenues rise and fall sharply with housing bubbles, but if properly targeted, these taxes can help prevent sprawl and encourage smarter building practices.

• Payroll taxes such as Social Security, health insurance, Medicare, unemployment insurance, pensions, and some other benefits come out of your check before you receive it. They ensure that everyone pays in for what they will or may use later and are applied in all industrial countries. In the Netherlands, money is even taken out for vacations; this vakantiegeld, or vacation pay, is then returned to workers in full right before summer begins so they will have the money to take a vacation. One problem with payroll taxes in the United States is that they are assessed for each worker rather than on total payroll as in most European countries. This encourages American employers to hire fewer employees and work them longer hours so as not to pay another set of benefits. Many part-time workers receive no benefits at all as a result.

• Excise taxes, such as gasoline taxes or taxes on alcohol and cigarettes, are also higher in Europe and help direct the market to provide more socially useful, sustainable, and healthy products while discouraging unsustainable consumption. In most other industrial countries, gasoline taxes are at least double what they are in the United States.

• Estate taxes help improve economic mobility by reducing the amount of inherited wealth that can be passed from generation to generation. Dubbed death taxes by the Republicans, they are actually among the most progressive of taxes because they fall almost entirely on the richest members of the population. While many rich Americans want to repeal them, some, such as Warren Buffett and Bill Gates, see them as essential parts of a fair tax system.

The important thing to understand is Oliver Wendell Holmes’s mantra: Taxes are the price of civilization. If we want an economy that truly provides the greatest good for the greatest number over the longest run, we must invest in public goods with smarter taxes. Though tax cutting may sometimes be justified and useful, it is no panacea for our economic problems, and it has played a central role in creating many of them.

Who Is Productive?

As a whole, providing the greatest good for the greatest number does require a greater level of public provisions and social insurance, and therefore, something of a transfer of wealth from richer to poorer. Such redistribution challenges deep-set beliefs. There is no doubt that the personal responsibility philosophy extolled by conservatives resonates deeply with many Americans and remains a fundamental ideological barrier to the expansion of our social safety net and greater economic security.

In part, that philosophy has its intellectual roots in the writings of Ayn Rand, an embittered Russian émigré in the United States who argued that a very few creative, productive, and ambitious people (symbolized by John Galt, the entrepreneur hero of her bestselling Atlas Shrugged) actually make possible all the good things in life, while most people—especially in Rand’s view, paid laborers—survive only because the John Galts and other self-made men of the world provide work for them. John Galt, Rand opines, should be praised, not taxed. If he and other jobs creators stopped working to protest their oppressive taxation, the rabble would starve.

When John read Atlas Shrugged in the 1970s, he found it cold and heartless, full of cardboard characters and intellectually vacuous. But many people, obviously, feel differently. At its core, Rand’s philosophy was distilled to a few simple words when John was challenged by a conservative student during a speech he gave at Georgia Tech: “So what I hear you saying is that you would take money away from the productive people and give it to the unproductive people?” In other words, the student said, John de Graaf would take cash from John Galt and give it to John Lazy.

Our response to that charge goes something like this.

And what we hear you saying, young man, is that those people who grow your food, harvest it in the fields, and transport it to the stores, those people who clean your streets and take away your garbage so you don’t have to live in filth, those people who will teach your children if you have any, and take care of your infants and toddlers while you do your “productive” business, those people who build the cars you drive in and many other products you use, those people whose work benefits you every day of your life—those people who have seen precious little improvement in their real wages during the past generation of policies favoring John Galt—those are the “unproductive” people whose survival only the Galts make possible.

And meanwhile, those other people, the ones who have seen their incomes mushroom and their taxes wither, those “self-made” people with expensive educations whose brainpower and hard work have created such wonders as exploding derivatives and credit default swaps, whose “products” never affect your daily life except when you have to bail out the disasters they create, those people who earn far more in a week than your child care providers will earn in a year, whose year-end bonuses often equal the lifetime earnings of ordinary workers—they are the “productive” people.

And you, young man, have a problem with taxing those “productive” people to provide a little more security for the ones you consider “unproductive.” Well, we see no possible moral justification for labeling the first group unproductive and the latter productive—quite the contrary, in fact—unless you automatically assume that Group B is more productive solely because its activities earn more in the market as it presently exists. Indeed, we believe that in a moral world we would offer greater compensation to those whose labor actually makes life better. In which case, there is absolutely no moral argument at all against greater equalization of incomes. In fact, we find the distribution of earnings in this economy to be morally obscene.

In the heady heights of Randian philosophy, however, what people earn from the market is what they are really worth, and is the result of their efforts alone. Taxing them in such a situation is a theft of their property. Their efforts alone make the world better; indeed, Randians suggest that government security measures, not deregulation, are to blame for the current crises. If only we had left it all to the market, they proclaim, things would be fine.

The problem with this argument, first of all, is that no one is truly self-made—Warren Buffett points out that he would not be a billionaire if he’d been born in Bangladesh. Moreover, it is impossible to prove or disprove the claim that, if we were true to the market, things would be great, since it is totally theoretical. It is akin to the radicals of the 1960s and ’70s who dismissed criticisms of the Soviet Union by saying: “Well, that’s not real socialism. Under real socialism, you wouldn’t have these problems.” But their more conservative critics countered correctly that actual socialism was all we could truly judge, and it was a failure.

Let’s turn that on its head: Americans have now had thirty years of actual tax-cutting, deregulating, privatizing government policy. We are demonstrably less fair, less secure, less satisfied, more indebted, more stressed, less healthy in comparison to people in other countries, and less happy than we were when Ronald Reagan first took office.

For most of those thirty years, we limped toward mediocrity and greater insecurity. But finally, in the fall of 2008, after continued deregulation of Wall Street, the “you’re on your own” philosophy came crashing down, stealing the rug from under millions of Americans, not to mention the roof and walls.

The Land Opportunity Forgot

You might agree that the Grand Canyon between rich and poor in America is huge and growing, but not think that is as big a deal as we do. “No one in America ever guaranteed anyone equality of results,” you might say. “What we offer here is equality of opportunity; it’s up to everyone to grab the golden ring for herself.” There was a time when this might have been true, a time when the claim that America was classless, though not really accurate even then, was at least buttressed by our relative economic mobility: how much chance a child born among the poor had to grow into an adulthood of wealth or at least comfort, how often a child from the lowest quintile of the population ended up in the highest. The United States may not have been number one in this area, but it was always close to the top. America truly was a land of opportunity.

It is now a land that opportunity has forgotten. A 2007 Pew Charitable Trust report, Economic Mobility: Is the American Dream Alive and Well?, found that “the United States has less relative mobility than many other developed countries.” Among the rich countries studied, only in the United Kingdom was economic mobility more restricted (and only a little more than in the United States).19 In every other country, a person born poor had more chance of becoming comfortable or even wealthy than here. Danes have three times as much chance, for example; Canadians two and a half and Germans one and a half times the chance.

In spite of these damning statistics, or perhaps because they are not well understood, Americans are still twice as likely as Europeans to believe that hard work brings rewards: 69 percent believe that “people are rewarded for intelligence and skill.” If that is still true, and America still offers more opportunity than Europe, then there can be only two possible explanations for the fact that Americans are twice as likely as western Europeans to live in poverty or for that fact that fewer than half of Americans are officially middle class (their incomes fall between 60 and 150 percent of the median), while nearly two thirds of Europeans fit that category.

The first is that Americans are genetically different: they have far more stupid people as a percentage of the population than Europeans do. This seems highly unlikely; science finds no such genetic differences in IQ between different countries. The second possibility is that more Americans simply don’t work as hard as Europeans; this too seems to counter the evidence. American workers are at least as productive per hour and work much longer than their European counterparts.

Something else, then, is going on here. We would put it this way: The American economy operates in a way that creates a wider gap between rich and poor than in other wealthy countries. It’s less fair, period, less well-structured to promote the greatest good. That needs to change. The inequality gap is the most significant difference between the United States and almost all other rich countries. Yet the evidence is clear that our lack of attention to promoting the greatest good for all of us has led to a lower quality of life for almost all of us, except perhaps the very rich.

Gus Speth, former dean of the Yale School of Forestry, points out that even a cursory glance at the annual well-being statistics provided by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development reveals that the United States ranks at or near the bottom in nearly every category. No economy provides complete equality, and complete equality would end economic incentives to work hard. But Wilkinson, Pickett, and many other scholars make a powerful case that America’s growing income chasm is a recipe for failure. Indeed, as Justice Brandeis made clear long ago, the future of American democracy itself demands that the gap be narrowed.