CHAPTER TEN

The

WATCHDOGS

“In next to no time, the fighting over the new drug laws that had been going on for five or six years suddenly melted away.”

—Frances Kelsey

In the 1950s, a German company developed a drug called thalidomide and sold it as a sleeping pill. Thalidomide also turned out to ease nausea in pregnant women. The company called the medicine “non-toxic” and “completely harmless even for infants.” It was sold over the counter without a doctor’s prescription.

To expand its market beyond Europe, the German manufacturer and its American partner asked the FDA to allow the drug’s sale in the United States.

“TOO GLOWING”

In 1960, Dr. Frances Kelsey was hired by the FDA to review new drugs. After only a month in her new job, she was assigned the task of determining whether thalidomide should be approved to market.

Well-qualified and experienced, Kelsey had doctoral degrees in medicine and pharmacology. As a graduate student at the University of Chicago in 1937, she had been on the team of scientists that identified diethylene glycol as the deadly ingredient in Elixir Sulfanilamide.

After Kelsey reviewed the materials submitted by the German and American drug companies, she was “very unimpressed.” She thought the testing of thalidomide was flawed and unscientific. She even wondered whether the results had been falsified. “The claims made…for thalidomide were too glowing,” she said later.

The pressure from the drug companies to grant approval mounted, but Kelsey and others in the FDA insisted on getting more information about the tests. Each time the companies resubmitted their application with the additional facts, the sixty-day approval period restarted. Kelsey’s requests for data about the medical effects of thalidomide delayed the drug’s sale in the United States for months.

Then the shocking reports emerged from Europe. Babies had been born without arms and legs. Some infants had defects in their internal organs, including the heart and intestines. By 1961, it was clear that the babies’ mothers had one thing in common. They had taken thalidomide during pregnancy. The drug companies apparently suspected trouble earlier and never informed the FDA.

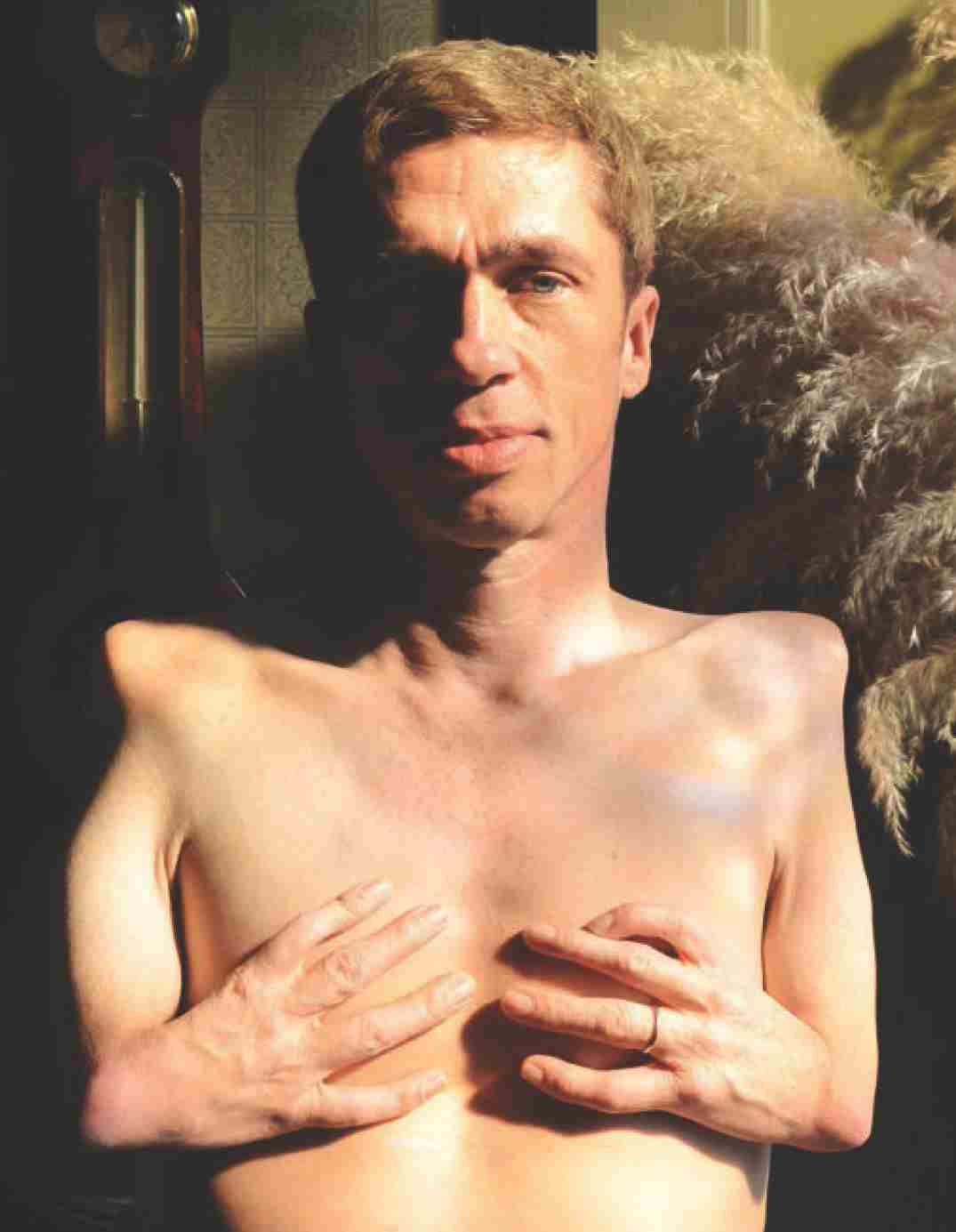

Thalidomide caused malformations, such as this victim’s feet.

HEARTBREAKING

Because Kelsey and the FDA moved slowly in granting approval, thalidomide was never sold in the United States. Unfortunately, the companies had already been testing the drug on American mothers before asking for FDA permission to market it here. According to the 1938 Act, they were allowed to distribute the drug if it was part of an experiment. Doctors participating in the test had given thalidomide to pregnant women. None of the mothers had a clue about the risk.

Thalidomide had been sold in forty-six countries. At least eight thousand babies were born with serious abnormalities, most in Germany and the rest of Europe. Five to seven thousand more died before their birth from damage caused by the drug. These are estimates, however, and some experts think the numbers were much higher. In the United States, about twenty affected babies were born. Up to two dozen others died before birth.

Photographs of the deformed children appeared in newspapers and magazines. The images were heartbreaking, and the American public demanded action. Once again, a tragedy had revealed weaknesses in a law meant to protect the nation’s health.

The mother of this British man, born in 1962, took thalidomide during her pregnancy. He is an actor and drummer.

Concerns about drug safety had been simmering in Congress for several years. Yet a bill addressing the issue failed to make headway. The dramatic publicity about the thalidomide babies brought the issue to a boil.

In October 1962, Congress passed the Kefauver-Harris Amendments to the 1938 Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, updating the procedure for drug approvals. Companies had to demonstrate that a drug was safe and effective by using a new standard of well-designed scientific studies. If a company knew of problems with the drug, it was obligated to inform the FDA. The sixty-day review limit was gone. A drug could not be marketed to the public until the FDA granted its approval.

DR. FRANCES KELSEY (1914–2015) wears the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service after President John Kennedy (1917–1963) presented it to her at the 1962 ceremony. Kelsey’s skepticism about thalidomide prevented its sale in the United States. Later, Kelsey said of the award, “This was really a team effort.”

RULES CHANGE

Today, the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act continues to guide the FDA. The 1962 Kefauver-Harris Amendments are among dozens of new laws passed since 1938 that are designed to close loopholes and increase the FDA’s duties.

The agency now has strict guidelines for human testing. An investigation like Wiley’s Poison Squads would have to be quite different.

To safeguard participants, a review board must okay the study. Animal experiments will likely be required first, and perhaps a human study won’t be permitted at all. Subjects must be given details about the experiment and its risks, and they must be told that they have the option of not participating. The expectant mothers who took thalidomide never had this information.

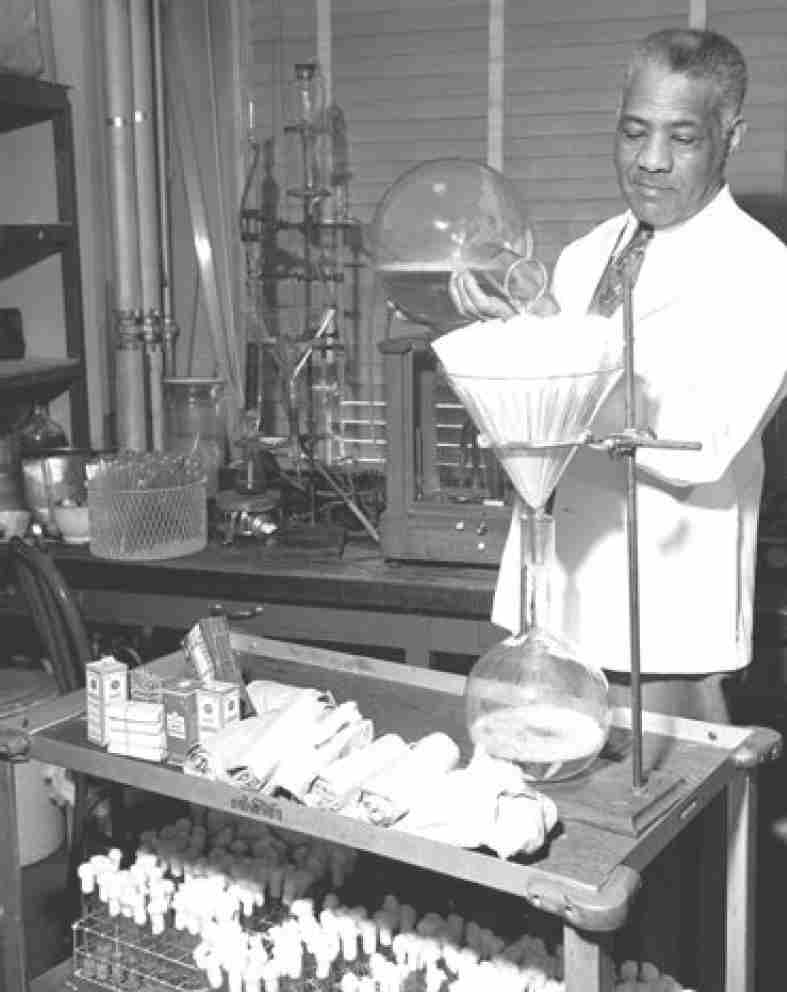

William Carter, who once cooked for the Poison Squad, later studied pharmaceutical chemistry and worked in FDA laboratories. He retired after more than forty years at the agency.

Unlike Wiley’s experiments with only young male subjects, males and females of various ages and races are tested. Special rules protect children and pregnant women. Ideally, an experiment is designed to minimize bias, even if unintentional. There are control groups. Whenever possible, subjects and researchers don’t know who is a control and who is receiving the test substance.

Researchers also look for long-term effects, something Wiley didn’t do. Will the drug or food additive cause cancer, gene damage, harm a developing baby?

EXPANDING…

When Harvey Wiley became head of the Division of Chemistry in 1883, he had fewer than a dozen people on his staff. After 135 years, more than seventeen thousand employees work at the FDA, which is part of the Department of Health and Human Services. A commissioner appointed by the president heads the agency. The FDA regulates products that make up a quarter of the money Americans spend each year. (See sidebar on this page)

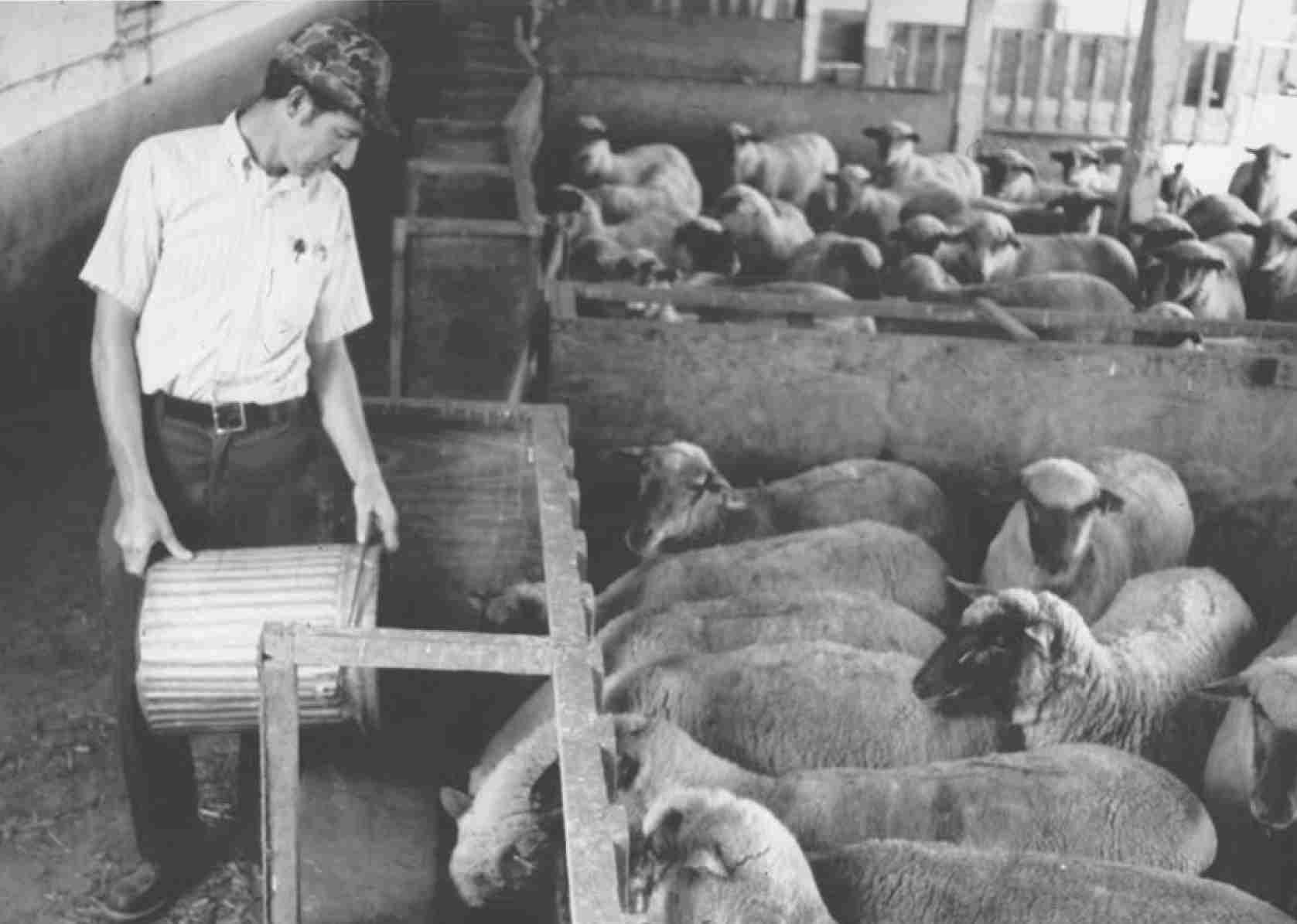

The FDA is responsible for the safety and effectiveness of food, drugs, and medical devices used with animals.

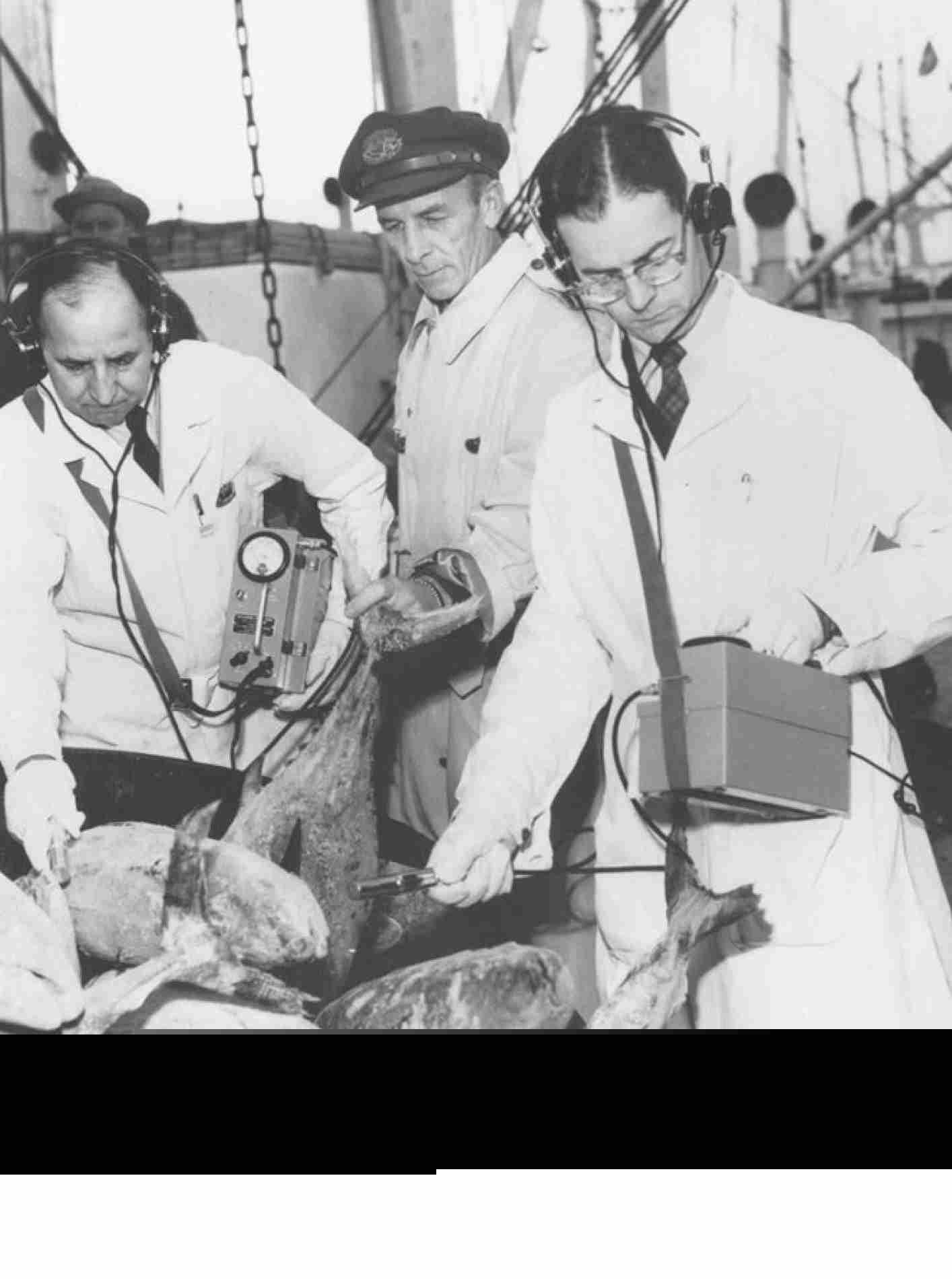

After nuclear bombs were tested in the atmosphere in the 1950s and 60s, FDA inspectors checked for unsafe levels of radiation in food, drugs, and cosmetics. In this photograph from about 1954, inspectors use a Geiger counter to measure the radioactivity of tuna that had been caught in the Pacific Ocean near the bomb-testing site. Today, the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health is in charge of radiation safety.

Besides prescription medicines for both humans and animals, the FDA oversees over-the-counter drugs like aspirin, cough syrups, sunscreen, and fluoride toothpaste.

It still doesn’t approve new cosmetics for safety and effectiveness before they’re sold. But the products aren’t allowed to include ingredients known to be unsanitary or harmful when used according to the label’s directions. Some consumer advocates think cosmetics contain too many toxic chemicals and the FDA hasn’t done enough to stop their use. They want Congress to pass a new law that requires the agency to evaluate the safety of these chemicals.

The FDA’s responsibility for food safety has become more complicated than it was when Wiley focused on additives. Today’s manufacturers no longer depend on large quantities of chemical preservatives. Modern methods of preserving and processing food include improved pasteurization, ultraviolet light, and electrical current. Researchers continue to pursue other approaches.

But other food hazards involve contamination by pesticides and by bacteria such as Salmonella, Listeria, and E. coli that cause foodborne illnesses. Each year, about forty-eight million Americans get sick from something they’ve eaten. That’s more than one in seven people. To monitor these dangers, the FDA cooperates with the states and other federal agencies, particularly the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

WHAT DOES THE FDA DO?

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration regulates products used every day by everybody. Congress has changed the agency’s responsibilities several times since 1906. As of 2019, the FDA oversees:

|

|

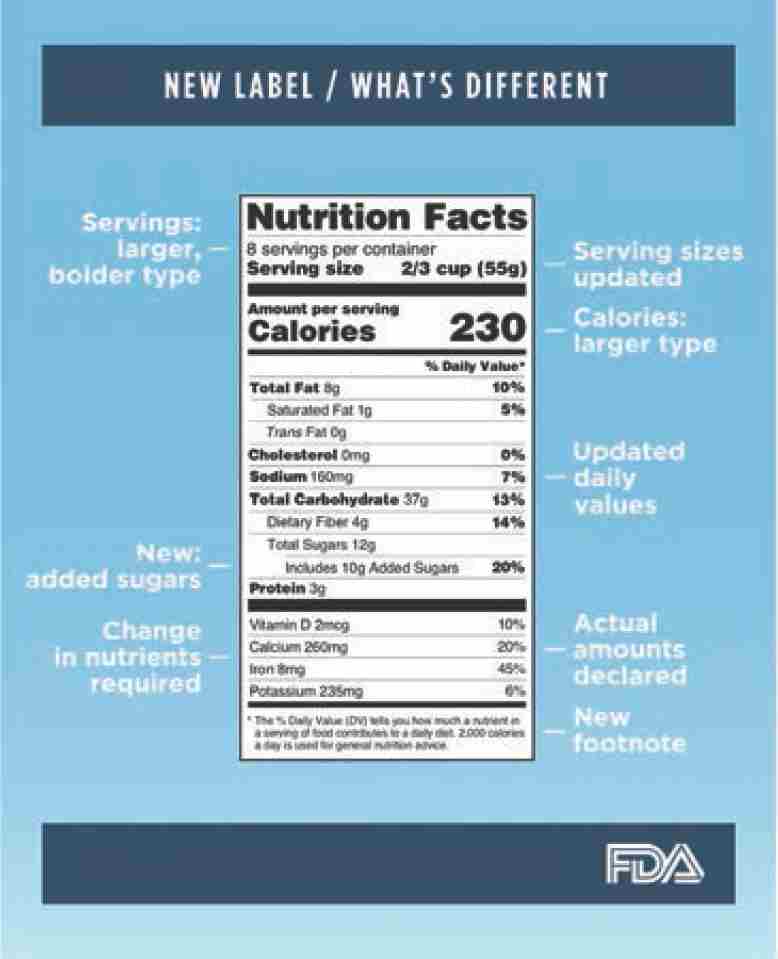

The FDA oversees nutritional labels on food, which include serving size, calories, and nutrient and vitamin content. Beginning in January 2020, food companies must replace existing labels (top) with new ones that are based on updated nutrition research (bottom). Larger serving sizes on the new labels better fit the amount people today actually eat. |

Recent presidential administrations have proposed putting the oversight of food safety into a single agency—the USDA—leaving the FDA to focus on non-food issues, including drugs, cosmetics, and medical devices. Proponents of the change argue that this reorganization, by being more efficient, will better protect the nation’s food. As of 2019, Congress has not approved this change.

FRAUDSTERS

In 2017, Hyland’s teething tablets were taken off the market by the manufacturer after an FDA warning about harmful levels of belladonna.

Fraud continues, despite laws and regulations. Dishonest companies dilute beverages and add unapproved additives to food. They sell counterfeit products: a cheap fish species sold as an expensive one; inexpensive city tap water sold in a bottle as pricey mountain-spring water.

Some labels are misleading, such as bread identified as whole wheat when it contains corn flour. In fall 2019, the FDA warned a Massachusetts company to stop listing “love” as an ingredient in its granola. The product was misbranded because love doesn’t qualify as a standard ingredient in granola…or in any other food.

Just as Wiley’s first inspectors did in 1907, today’s FDA inspectors search for these deceptions. They check facilities throughout the country that prepare foods and drugs. They also visit manufacturing plants in foreign countries that send products to the United States.

Inspectors find filthy factories contaminated by toxic chemicals, bugs, rats, and workers who wipe their noses while handling food. The FDA issues official public warnings about violations. If a company doesn’t correct the problem immediately, the agency can seize products and stop their sale. Thousands of unsafe or fraudulent products are recalled each year after an FDA investigation.

Companies still try to entice consumers to buy worthless or harmful drugs. A century after Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup endangered children, the FDA discovered a similar product on the market in 2016. A California company was illegally adding morphine to its non-prescription Licorice Coughing Liquid. The agency forced the company to recall the medicine.

A case from 2017 involved Hyland’s Baby Teething Tablets, a non-prescription product sold online and in stores. The label claimed that the tablets eased infant discomfort in a “100% Natural” way with “No Side Effects.” The FDA had not approved the product as safe or effective.

After receiving complaints from the public about children having bad reactions, the FDA investigated. Its chemists analyzed the tablets and found harmful levels of belladonna (also known as deadly nightshade). In certain doses, this toxic chemical can cause high heart rate, hallucinations, and seizures in young children. The agency issued safety alerts to warn parents.

In the wake of the FDA’s formal request, the company recalled the tablets and stopped selling them in the United States. It continued to say on its website that the amount of belladonna was not dangerous. The tablets, it assured customers, “have been safely used by millions of children since being introduced to the U.S. market in 1945!”

To monitor contamination and nutrient levels in the food supply, the FDA regularly analyzes groceries typically bought by consumers.

GUARDING THE NATION’S HEALTH

A government agency with as much power as the FDA is certain to have critics.

Some of them point out that there are thousands of new drugs and food additives and the FDA can’t possibly check the safety of all. They believe that the agency is too quick in giving the green light to new products and is too slow in recalling harmful ones. As a result, the public is at risk.

Other critics charge that the FDA is too big and controlling and wastes taxpayer money. They object to the government preventing people from making their own decisions. Some detractors say the FDA takes too long to approve new drugs and vaccines that could help people. And others accuse the agency of being too tough on businesses when it does inspections and issues recalls.

Dr. Harvey Washington Wiley, Father of the FDA

Harvey Wiley heard similar complaints about his Bureau of Chemistry in the early twentieth century. But Old Borax kept up his fight “toward improving the nutrition, and consequently the health of the nation.”

After more than a hundred years, the results of his Poison Squad experiments have been questioned. Some of the chemicals he called toxic are safely added to food today. His understanding of the effects of preservatives on digestion was incomplete. Science advanced, and discoveries in nutrition and chemistry expanded our knowledge.

Yet Wiley started a tradition of using scientific research to determine the safety and effectiveness of food and drugs. Current laws reflect his view: chemicals should only be added when necessary; they should be labeled for the consumer; and manufacturers should prove a substance’s safety before being permitted to add it.

A few months before his death, Wiley looked back on his life with satisfaction. He knew he had helped lay the foundation for the 1906 Food and Drugs Act. “Certainly it is important,” he wrote of the day the law was signed, “in that long and proud record of legislation seeking to guard the well-being of men, women and children.”