Dealing with conflict has been recognized as of particular importance in leadership. In organizational life, the typical manager may spend 25% of his time dealing with conflicts (Thomas & Schmidt, 1976). A common conflict occurs between the manager’s boss, whose paramount concern is for productivity, and the manager’s subordinates, whose paramount concern is for consideration.

The leader’s personality affects his or her rational and emotional feelings about conflict and what to do about it. One president, Lyndon Johnson, wanted every American to love him; another president, Harry Truman, concluded that, “If you can’t stand the heat, stay out of the kitchen.” National leaders must settle for less than universal affection. They must be willing to be unloved and they must deal with conflict (J. M. Burns, 1978). And so must most other leaders, for conflict often attends the leadership role. No leaders can be successful if they are not prepared to be rejected (T. O. Jacobs, 1970). Nonetheless, Levinson (1984, p. 133) pointed out that executives go to great lengths to avoid conflict because of their discomfort with feelings of anger. He observed that “much of the irrational in management practices arises because of people’s efforts to cope with their own anger and to avoid the anger of others. … But the very fact that they have angry feelings, when they often feel it is wrong to be angry, leaves them feeling guilty.” To contend with these feelings of anger and guilt, they make irrational decisions to deny their anger and to appease their conscience. Or they may avoid making or announcing the decision to avoid the conflict implied. Many leaders are like President Nixon, who had to rely on subordinates to relay the bad news to someone whom he wanted to fire or whose actions had been displeasing to him.

Appointed leaders with appropriate competencies and styles may still find their attempts to lead stymied because of numerous possible conflicts with their subordinates. The appointed leader may be resented as a representative of higher authority (Seaman, 1981), or subordinates may favor the appointment of someone else. The leader and the subordinates may have different opinions about the means and ends of their efforts, as well as other ideas. For example, college presidents and vice presidents may disagree about their institutions’ goals, although they generally are more likely to agree about means (Birnbaum, 1987a). A superior’s and a subordinate’s differences of opinion about the difficulty of achieving competence in the superior’s job may be another source of conflict. In an eight-country sample of 1,600 managers, the average time that senior executives thought it would take their subordinates to learn the senior executive’s job was 18 months; their subordinates estimated it would take them less than six months (Heller & Wilpert, 1981).

A conflict is mainly cognitive in nature when, say, executives disagree about the legality of an action and then call on the legal department to inform them about the law or regulation involved. A conflict is mainly emotional if, say, executives disagree on whether or not they have been disparaged and ignored by the CEO and should or should not tell him so. According to an analysis of conflict among 72 supervisor-subordinate dyads, cognitive and emotional conflict form a two-factor structure. One factor is purely emotional; the second factor is a combination of emotional and task conflict (Xin & Pelled, 2003). Generally, if a conflict is mainly cognitive, the outcome could lead to better understanding, affective acceptance, and a higher-quality decision, but more often does not. Making conflict constructive will be discussed later in the chapter. If a conflict is mainly emotional, the outcome will be less well understood and will result in a less emotionally acceptable decision. The resulting decision will be poorer (Amason, 1996). Xin and Pelled’s (2003) data revealed that both emotional, and a mix of emotional and task conflicts, were negatively related to supervisory leadership behavior—more strongly in the case of emotional conflict. In agreement, Carsten and Weingart (2002) conducted a meta-analysis, which showed that in studies of task conflicts the average correlation was —.27 with individual satisfaction (12 studies) and —.26 with team performance (25 studies). The corresponding correlations in studies of socioemotional conflicts were –.48 (14 studies) and –.22 (24 studies). From 1,048 to 1,808 individuals were involved.

Sources of role conflict for leaders include the ambiguity of a role, personal inadequacy to meet the demands of a role, incompatibility among several roles, conflicting demands, mixed costs and benefits associated with playing a role, and discrepancies between actual and self-accorded status. Role ambiguity occurs when leaders’ roles are not clearly defined and the leaders cannot determine what they are expected to do (Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, et al., 1964). Also, leaders may not be able to meet the demands of a task or the interpersonal demands of their role (D. J. Levinson, 1959). An incongruence occurs when, for instance, old, experienced workers are assigned to young, inexperienced supervisors. The workers are likely to perceive a discrepancy between their seniority and their rank in the status hierarchy (S. Adams, 1953). Interrole incompatibility occurs when an individual plays two or more roles in a group and the demands of these roles may be incompatible. For example, the role of group representative may be incompatible with the role of enforcer of discipline (Stouffer, 1949). Or there may be within-role conflict. That is, when different followers make conflicting demands on a given leadership role, the occupant of the role will find it difficult to take any course of action that will satisfy the various sets of expectations (Merton, 1940).

Conflict can occur if one would lose power, esteem, autonomy, or self-determination by joining or forming another group. For example, group members may reject an opportunity to join suggested coalitions with others in three-way bargaining situations even if that would be otherwise rewarding, because joining would cause loss of esteem in relation to the other members (Hoffman, Festinger, & Lawrence, 1954). Holt (1952a, 1952b) inferred from analyses of French cabinets and college interfraternity councils that otherwise mutually rewarding coalitions were rejected because a loss of autonomy or self-determination was involved.

Conflicts and disagreements may arise in the legitimatization process—in the right to function as a leader. Thus, when kingdoms were reconstituted in the nineteenth century in such countries as Belgium, Bulgaria, Greece, and Sweden, outsiders from Germany and France were legitimated as kings to avoid internal dissent. Selection of a presumably impartial outsider as constitutional monarch is consistent with the tendency for a leader of an organization to be acknowledged as the one organizational member with the legitimate power to play the role of final arbitrator, the superordinate whose judgment can settle disputes among political factions. This function was often believed to be critical for the avoidance of anarchy. The maintenance and security of the state depended on the existence of a legitimate position at the top whose occupant could arbitrate conflicts among all followers. Daum (1975) looked at the impact of internal promotion versus bringing in an outsider to lead the group. The results were as expected. The selection of a leader from within the group tended to cause the remaining members to express lower overall satisfaction and to reduce their voluntary participation following the change.

If members can agree on the leadership structure, they are more likely to be satisfied with the group, according to results obtained by Shelley (1960b). Similarly, Bass and Flint (1958a) found that early agreement about who shall lead increases a group’s effectiveness. Heslin and Dunphy (1964) noted that the satisfaction of members was high when the degree of consensus about one another’s status was also high.

Role Ambiguity. One’s location in an organizational hierarchy will make a difference in how much role ambiguity one experiences. Culbert and McDonough (1985) suggested that much of the conflict observed in organizations starts at the top with excessive competition among senior executives with special interests vying for power. Without their awareness, a domino effect is created; the competitive conflicts at the top set off conflicts at each echelon below. Culbert and McDonough (1985) attributed much of the conflict in industry to the failure of those who are in conflict to recognize that they actually have compatible interests. Sometimes they did not acknowledge one individual’s contributions to another or to the organization, and sometimes they did not achieve “a common frame of reference so that each could see that the other’s efforts made organizational sense.”

More role ambiguity occurs among lower-level managers. The responsibilities and authority of first-line supervisors and middle managers are less clearly defined than those of top management. Uncertain about what they are allowed and expected to do, they experience more tension than the top managers and feel less satisfied with their jobs. Thus D. C. Miller and Schull (1962) reported that middle managers registered more role stress than top managers and more frequently stated that they were unclear about the scope of their responsibilities and what their colleagues expected of them. Likewise, Brinker (1955) reported that first-line supervisors in industry worked under constant frustration because they were not given enough authority to believe they were part of management or to solve the problems presented by their subordinates. Supervisors of 140 management clubs wanted to be more closely identified with higher management because most of them felt that they did not know the company policy on many important matters and, as a result, they had to work in the dark (Mullen, 1954). Moore and Smith (1953) found that in the military, non-commissioned officers rather than higher-ups felt constant pressure because of their inadequate authority, a lack of distinction between supervisors and technicians, and conflicts among the leadership philosophies of different levels of organization. Consistent with all these findings, Wispe and Thayer (1957) found less consensus about the functions of the assistant manager than about those of the manager. The assistant manager’s role was ambiguous in that neither the manager nor the assistant manager knew whether certain functions were obligatory or optional. Strain and tension were higher for the assistant manager in the more ambiguous role.

Different Assignments. Conflict arises between managers and professionals; between people in boundary-spanning activities that link activities outside and inside an organization, such as marketing, and people in internal operations such as manufacturing. Interviews have established that boundary spanners had interpersonal and cooperative orientations, whereas line managers emphasized authority, power, and rationality (Anonymous, undated). Conflict arises between staff and line workers and between individuals, in general, who work in different parts of the same organization. For example, there is continual tension between university administrators and faculty members and between hospital administrators and community physicians. Much of this tension is due to their differences in perception (Browne & Golembiewski, 1974), attribution (Sonnenfeld, 1981), and cognitive orientation (Kochan, Cummings, & Huber, 1976). Nystrom (1986) found systematic significant differences in the work-related beliefs of middle managers who were responsible for the supervision of line personnel and those in the same manufacturing organization who were responsible for designing the work processes and specifying outputs and controls. Middle-line managers believed more strongly in the desirability of structuring people’s work activities than the technical design managers, who had a stronger belief in internal rather than external loci of control. The middle managers also were more motivated to manage than the technical design managers.

Different Perspectives. A mail survey of 155 organizations indicated that divided or unclear support by senior management for employees’ involvement resulted in resistance by middle management to such involvement. The expected benefits to the firms of employees’ involvement failed to appear when management was in conflict about the practice (Fenton-O’Creevey, 1998). Those at the bottom and top of their union hierarchy may have unflattering opinions about each other. S. M. Peck (1966) found that union stewards saw corruption in their top union officials but justified the unethical activities of the top officials on the grounds that strong methods were required to cope with existing conditions and that corruption was endemic. Miles and Ritchie (1968) reported that high-ranking union officials “agreed” that shop stewards and rank-and-file members should be encouraged to participate more in decision making and that such participation would result in improved morale, better decisions, and willingness to accept the goals of bargaining. Nonetheless, they were uncertain whether stewards and rank-and-file members would set reasonable goals for themselves if given the opportunity.

Another source of continuing conflict is the limited control that managers have over the resources they need to get their work done (Pfeffer, 1981a). In a study of laboratory directors at hospitals, Jongbloed and Frost (1985) found that the laboratory directors were constrained by numerous individuals and groups outside the laboratories, including the physicians who were responsible for ordering the laboratory’s tests; by the hospital’s higher administration; and by the head of the department of pathology, as well as accreditation councils, labor unions, and professional societies. One laboratory director coped satisfactorily with this conflict; another did not. The successful laboratory director devoted a lot of energy to lobbying for increased resources and gained more needed funding. The unsuccessful director concentrated on the technical aspects of the laboratory operations and was forced to continue with a less adequate budget.

Pfeffer and Salancik (1978) examined the amount of discretion mayors had in determining items for their cities’ budgets. They found that mayors who dealt with powerful organized interest groups, such as businesses, professional societies, and labor unions, had less discretion over the budgets than mayors whose cities had a higher proportion of nonwhites, governmental employees, and construction workers, and a lower median income.

Conflicts between work and family—particularly conflicts over child care and home care—have become major issues since the movement of large numbers of women into the workforce (Lerner, 1994). Imbalance between work and life has become a major source of stress at the workplace and in the family (Kozek 1998). Fisher-McAuley, Stanton, Jolton, et al. (2003) calculated the path analysis for 603 physical fitness professionals (89% female, mean age close to 41). Their opportunity to balance their work and life revealed a path coefficient of .50 with their job satisfaction, which in turn correlated –.61 with their intention to quit.

To some extent, role conflict and its effects are in the eye of the beholder. Maier and Hoffman’s (1965) study of role-playing groups found that some discussion leaders perceived interpersonal conflict as a source of lower-quality decisions. Other leaders saw disagreement as a source of innovation and new ideas. But more often, role ambiguity and role conflict tend to be deleterious to leaders’ performance and satisfaction. Uncertainty about whether one’s performance is adequate is a symptom of role ambiguity and a source of ineffectiveness, according to Pepinsky, Pepinsky, Minor, et al. (1959), who studied experimental groups working on a construction problem. The leaders of half the groups were required to work with a superior officer whose approval or disapproval of transactions could be predicted. The leaders of the other groups were required to deal with a superior whose behavior could not be predicted. The researchers found that the productivity of the team was higher under conditions of high predictability than under conditions of low predictability.

Rizzo, House, and Lirtzman (1970) found that with more perceived role ambiguity and conflict, less overall leadership behavior and less job satisfaction were reported in two industrial firms. Tosi (1971) also obtained results indicating that role conflict was negatively related to job satisfaction but not necessarily to the effectiveness of the group. Supervisors seemed able to tolerate role conflict better if they did not have to interact much with their own immediate bosses. In a study of seven companies, supplemented by a national survey, R. L. Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, et al. (1964) found that role conflict increased as the ambiguity of the situation increased and the rate of communication with one’s superiors was high. Job satisfaction decreased under these same conditions. They inferred that the source of most role conflicts is in interactions with one’s immediate superiors. Subsequent studies corroborated this, reporting that as much as 88% of all role conflict was with one’s boss.

In all, anyone in an organizational hierarchy needs to act both cooperatively and competitively. Roberts (1986) surveyed 350 managers from three levels of management in two business firms and two universities. In all four organizations, managers reported using both cooperative and competitive styles in their relations with their bosses, peers, and subordinates. This is likely to be one reason why successful performance in an initially leaderless group discussion is a valid predictor of success in management positions (Bass, 1954a): both situations call for cooperating and competing with others.

Conflicts within and between individuals arise when there are incongruities or mismatches among their levels of status and esteem, their rules, roles, influence, competence, personality, and expectations.

Status-Status Incongruence. Ordinarily, people have multiple roles and positions and are accorded status for each. Each status may be matched in value with the other statuses, or it may be incongruent. In organizations that are a mix of bureaucracies and collegial entities, conflict arises because the same individuals must play roles with various degrees of status and importance, depending on the decisions involved. For example, in a university hospital, the university president, the vice president for health sciences, and the medical school faculty will have more influence than the hospital’s governing board over the selection of the dean of medicine, the hospital director, and the chief of the medical staff; but the reverse will be true of issues related to the financial integrity of the hospital. Among 26 such decision-making issues, Wilson and McLaughlin (1984) found that with regard to influence there was little correlation between the medical school department head, the dean, and the hospital director. The influence of the incumbent of a particular position in the hospital depended mainly on the issue.

Conflict results if there is an incongruity between one’s status in one situation and in another. For example, military enlisted personnel who had high-status civilian positions were more dissatisfied with their officers than were enlisted personnel who came from civilian jobs of lower status. Former engineers were more critical of their officers than former truck drivers were (Stouffer, Suchman, De Vinney, et al., 1949). Conflict is less and performance more effective when there is congruence between two sources of a leader’s status. Knapp and Knapp (1966) studied elected officers and nonofficers who served as group leaders in a verbal conditioning experiment. Groups led by officers exhibited a higher rate of response and conditioned more readily than groups led by non-officers. The official status of the leaders facilitated the groups’ learning.

Search for Congruence. People tend to try to increase status-status congruence. In class-conscious Britain, 156 first-line supervisors varied in the social class to which they felt they belonged. Those who perceived themselves as higher in social class more readily identified with their senior managers. And the more they thought that their role as supervisor was lower in status than the status of their social class, the more they identified with the senior managers (Child, Pearce, & King, 1980). Jaques (1952) observed much anxiety and confusion when a British worker (low status) was assigned to chair (high status) a conference with management. Relief and satisfaction came only after the managing director took the chair. Trow and Herschdorfer (1965) found that groups with incongruent status structures that were free to change did so, whereas those with equal freedom but with congruent structures did not change. Furthermore, groups with high degrees of status incongruency were rated low in the performance of tasks and in the satisfaction of their members. Similarly, in a study of 50 workers in one department of a firm, Zaleznik, Christensen, and Roethlisberger (1958) found that members with high status congruence were most likely to meet the productivity standards of management. Likewise, S. Adams (1953) demonstrated that group members were better satisfied when leadership and other high-level positions were occupied by persons who ranked high in age, education, experience, and prestige. The group’s productivity tended to suffer when the high-status positions were occupied by persons who ranked low in other aspects of status (age, education, experience, and social position). Yet Singer (1966) found that although status incongruence in groups was associated with tension, disorganization, and hostile communications, it did not result in lower productivity by the group or in the dissatisfaction of the group members.

Two Leaders. Two consuls were appointed each year to lead the Roman republic to avoid the possibility of dictatorship by one. Groups with two appointed, elected, or emergent leaders are inherently likely to generate conflict. Osborn, Hunt, and Skaret (1977) looked at potential conflicts between two leaders whose duties overlapped—the fraternity chapter adviser and the elected president—in each of 33 local chapters of a national business fraternity. The authors concluded that organizational effectiveness would be enhanced if only one leader played an active role in influencing subordinates and exchanges with other units. Similar conclusions about the inherent conflict in the overlapping roles of two leaders were reached by Whyte (1943), who examined two-leader configurations in mental institutions.1 When coleaders are appointed as joint heads of social work training groups, conflicts between the leaders will block the groups’ development. But if the two leaders can work together and resolve their potential disagreements, advantages will accrue in the greater opportunities to vary their roles, the wider perspectives for solving problems, and better management of and support and reinforcement for the group (Galinsky & Schopler, 1980). Such duality is built into German firms, which are led by a technical director and a commercial director and—unlike U.S. firms—have no single president. Again, although conflicting loyalties may be created, the benefits of this organizational design include equal attention to the quality of the products and to commercial success. Co-directors and co-presidents of organizations can conflict, and this will block an organization from successfully functioning.

Formal-Informal Incongruence. Mismatched formal and informal structures in any organization may be a threat to the organization (Selznick, 1948). Moreno (1934/1953) noted that the formal groupings which a higher authority superimposes on informal, spontaneous groupings are a chronic source of conflict. Roethlisberger and Dickson (1947) associated workers’ dissatisfaction with discrepancies between the formal and informal organizations in an industrial plant.

Cause and effect may be reversed. Inadequacy of and dissatisfaction with the formal organization may give rise to an unrelated informal organization that is at variance with the formal one. The informal organization emerges as a means to resist the coercive demands of high-status members of the formal organization (Shartle, 1949b). Such an informal organization may arise if the formal organization cannot provide the members with rewards like recognition or opportunity (Pfiffner, 1951), and may bypass incompetent, high-status members in order to achieve the goals of the formal organization (Lichtenberg & Deutsch, 1954). When the formal and informal structures are remerged, however, conflict is lower and the group’s performance is better. Stouffer, Suchman, DeVinney, et al. (1949) observed that discussions were more satisfying to the participants when the informal leaders were given higher status by being placed in the position of discussion leaders. Haythorn (1954a) reported that the performance and cohesiveness of bomber crews were highly related to the extent to which the aircraft commander (the formal leader) performed the informal leadership roles usually expected of the formal group leader.

Role-Role Incongruence. Playing a variety of roles is not necessarily stressful. The average individual learns to play the role of child, sibling, parent, subordinate, peer, and superior without apparent effort. However, some individuals play only dependent roles well, and others are content only when they play the role of superior. Professionals tend to assume the role of authoritative, independent agents. Professional actors seem to enjoy enacting a great variety of roles but can experience personal conflict in separating their real selves from the parts they play: that is, in separating their private life from their public image. Although we may not be accomplished actors, we can play a variety of roles without apparent stress if the different roles are compatible. Nevertheless, we may find different roles incompatible with each other and, therefore, a source of conflict for us. Thus Getzels (1963) found that schoolteachers were expected to maintain a socioeconomic role that was higher than their salaries could sustain. On the one hand, in their role as citizens, they were often expected to be more active in church affairs and less active in political affairs than the average citizen; on the other hand, in their professional roles, they were expected to be certified as experts in various fields of knowledge, but they could be challenged by any parent or taxpayer. Thus teachers were subject to several sources of conflict in each of several incompatible roles. Getzels and Guba (1954) also studied individuals with two or more roles that were subject to contradictory or mutually exclusive expectations. They found that such role conflict tended to increase when one of the individual’s roles was perceived as illegitimate. Moonlighting workers would be an example if their daytime bosses frowned on their workers taking a second job or if taking a second job was illegal.

Status-Authority Incongruence. Evan and Simmons (1969) studied students who were hired to work as proofreaders. In the first experiment, their pay (supposedly an indicator of the worth and importance of their position) was inconsistent with their acknowledged level of competence. In the second experiment, their pay was inconsistent with their level of authority. Incongruity, particularly the underpayment of students in relation to their authority, resulted in a reduction in the quality of work and in conformity to the organization’s rules.

Status-Esteem Incongruence. Conflict ensues and a group’s performance is adversely affected when the group members who are in positions of importance (high status) are not esteemed (Bass, 1960). J. G. Jenkins’s (1948) study of two naval air squadrons—one with high morale and one with low morale—found that in the high-morale group, the squadron commander and executive officer were most often nominated as individuals with whom others would want to fly (that is, they were esteemed as well as high in status); but in the low-morale squadron, the commander or executive officer was not the most esteemed member. Palmer and Myers (1955) found a correlation of .38 between the effectiveness with which 40 antiaircraft radar crews maintained their equipment and the extent to which they esteemed their key noncommissioned officers. Similarly, Bass, Flint, and Pryer (1957b) obtained a correlation of .25 between the extent to which status was correlated with esteem in an experimental group and the subsequent effectiveness of the group. Gottheil and Vielhaber (1966) also observed that groups performed more effectively when their leaders were esteemed. Using interview studies, Shils and Janowitz (1948) concluded that German enlisted soldiers’ high morale and motivation to resist surrender during World War II seemed primarily due to their esteem for their officers. It continues to be true that German workers esteem their supervisors (Fukuyama, 1997). Among those Israeli soldiers in Lebanon in 1982 who believed the incursion to be immoral, morale remained high only if they highly esteemed their officers (Gal, 1987).

Firestone, Lichtman, and Colamosca (1975) had college students elect their own group leader after participating in an initially leaderless group discussion. The groups that were subsequently most effective in an emergency were those led by the elected member with the highest ratings for performance in the leaderless group discussion. Those that were worst in the emergency were led by the person they believed had the lowest ratings for performance in the preceding leaderless group discussion.

Status-Influence Incongruence. Ordinarily, those who are higher in status more frequently emerge and succeed as leaders. It becomes a source of conflict if a person of low status attempts to lead. Watson (1982) coded the taped interactions of 16 leader-subordinate dyads in a goal-setting discussion to discern their specific effects on each other. The dyads were made up of an elected leader of a student team and one randomly chosen subordinate team member. When the elected leaders attempted to dominate by abruptly changing the topic, by challenging a previous comment, or by making an ideational or personal challenge, the subordinates were most likely to respond with deference and a willingness to relinquish some but not all behavioral options. When the subordinates tried to dominate, however, the leaders resisted and competed for control of the situation. Thus when persons of higher status, the elected leaders, acted in congruence with their status, the subordinates complemented and completed the interaction with deference and simple agreement; but when the subordinates with lower status tried to dominate, the leaders resisted.

Inversions can occur in which those who are lower in status are able to be more influential than those who are higher in status. Such inversions can be a source of continuing resentment and hidden conflict when the high-status figures grudgingly acquiesce to those who are lower in status. Obviously, subordinates can be more influential over leaders who abdicate their role. Pettigrew (1973) gave examples of situations in which subordinates or those who are otherwise lower in status have influence over those who are higher in status. Generally, in these situations, higher-status superiors became dependent on their subordinates (Mechanic, 1962). Physicians can become so dependent on attendants in hospital wards that the attendants can block reforms. Prison guards can become dependent on the inmates for the inmates’ good behavior. Although guards can report prisoners for disobedience, too many such reports from the same guards create the impression among their superiors that they are ineffective. As a consequence, guards agree to let certain violations by prisoners go unreported in exchange for the prisoners’ cooperation in other matters. Experts can keep their superiors dependent on them for information, particularly about risky innovations, and thereby maintain power over their superiors (Crozier, 1984). Subordinates in the Soviet Union held their superiors hostage with their knowledge of illegal acts the superiors committed in order for the group to meet its production quotas (Granick, 1962).

Status-Competence Incongruence. If those with high status are incompetent for their role assignments, the group will be less productive, less successful, and less satisfied; and more conflict will be generated within the group. But strong positive associations between competence and effective leadership have been found in surveys and experiments. Woods (1913) related the judged ability (strong, mediocre, or weak) of 386 European sovereigns to their states’ performance from the eleventh century to 1789. A correlation of .60 was found between judged ability of a sovereign and ratings of the political, material, and economic progress of the state the sovereign headed. Similarly, Rohde (1954c) reported correlations up to .63 between the success of groups learning to go through a maze and the adequacy of the pretest performance of the person in charge of each of the groups. Furthermore, in a comparison of nine orientation discussion groups, Stouffer, Suchman, DeVinney, et al. (1949) observed that members were much more likely to say they “got a lot out of the discussion” when the member of the group who was chosen to lead the discussion was better educated. Bass (1961c) found that successful leadership was more highly related to ability in effective groups than in ineffective groups.

The choice of a competent leader is a major determinant of the effectiveness of a team and stimulates effective mutual influence among team members (Borg, 1956). Thus after analyzing a large number of small-group studies, Heslin and Dunphy (1964) concluded that group members are most likely to achieve consensus on the status structure of the group when: (1) the leader is perceived to be highly competent; (2) a leader emerges who is high in both group-task and group-maintenance functions; or (3) two mutually supportive leaders emerge, one specializing in task functions and the other in group-maintenance functions. (But two leaders of a single group may present problems, as was noted earlier.)

The mismatching of status and competence in a group is likely to result in the downgrading of the group leader. Thus Ghiselli and Lodahl (1958a) found that a supervisor was likely to be poorly regarded by higher management if he led a group containing a worker whose supervisory ability was superior to his. Goldman and Fraas (1965) noted the importance of matching competence and status in their comparison of groups whose leaders were elected, appointed for competence, or appointed randomly. They found that groups with leaders who were appointed for competence did best; groups with elected leaders did next best; and groups without leaders or whose leaders had been appointed randomly did the worst.

Effects of Loyalty. Ordinarily, we would expect that competent groups would produce higher-quality decisions. But Dooley and Fryxell (1999), in a study of 86 strategic decision teams in hospitals, found that the quality of these teams’ decisions was higher—according to independent judges—only when the members were seen as more loyal (they did not try to take advantage of each other) and expressed many differing opinions. The quality of decisions suffered when the team members expressed many different opinions but were low in loyalty (tried to mislead each other). For high-quality decisions and commitment, both competence and willingness to disagree were necessary.

Incongruence of Competence and Power. Exline and Ziller (1959) assembled groups in which members held positions that were incongruent in competence and power, and other groups in which competence and power were congruent. The participants rated the congruent groups as significantly more congenial, as exhibiting stronger agreement between members, and as involving less overlap of activities.

Incongruence of Personality Traits and Roles. As might be expected, effectiveness is reduced by incongruities between the organization or group members’ personality traits and the roles required of them. Smelser (1961) selected students who scored either high or low on a personality test of dominance. The least productive dyads were composed of pairs in which the partner assessed as submissive was assigned to a role that required dominance and the partner assessed as dominant was given a role that required submissiveness. The most productive dyads were those in which role assignments were consistent with personality assessments.

Requisite personality may be a matter of expectations. Violated expectations generate conflict. Lipham (1960) tested the hypothesis that personality traits compatible with expectations about a leadership role will be related to the leader’s effectiveness. In a study of school principals, Lipham found that those who scored high on expected characteristics, such as drive, emotional control, and sociability, were rated more effective than those who scored high on unexpected characteristics such as submissiveness and abasement. In a study of insurance agencies, Wispe (1955, 1957) found that successful agents were characterized by a strong drive for success. But the same attitude toward success, when exhibited by the agency manager, was at variance with the agents’ expectation of a more humane, considerate orientation toward their problems. Thus the characteristic that was perceived to contribute to successful selling was not necessarily expected to contribute to effective supervision.

Overt conflict was avoided (at a price) when those of lower status hid their abilities from those of higher status. Before the social revolution of the 1960s, college women often used to “play dumb” on dates, just as black subordinates did in dealing with white superiors. Ordinarily, a better way for an organization to avoid conflict and to enhance satisfaction and performance is to develop suitable promotional policies that match the competence of employees with their status (Bass, 1960).

The failure of individuals to align their own needs for personal meaning, identity, and success with what they believe the organization needs to receive from those in their roles is at the heart of individual members’ conflicts within an organization (Culbert & McDonough, 1980). Organizational and personal needs must be fused to allow both the individual and the organization to reach high levels of achievement and satisfaction (Lester, 1981).

Within-Role Expectations. The negative effect of within-role expectations in groups, organizations, and society is largely attributable to discrepancies between what the members expect they should do and what others expect them to do. They experience conflicts when others make contradictory demands on their roles in the group, organization, or society that cannot be satisfied by any compatible course of action (Brandon, 1965). The man or woman in the middle is a well-known example.

The Man or Woman in the Middle. This is a common dilemma. Like everyone else at each successive level in an organizational hierarchy, the supervisor is a man or woman in the middle. Such persons face conflicting role demands from at least two sources: their superiors and their subordinates. Although the person in the middle is likely to be subjected to competing demands from numerous other sources—peers, higher authority, rules, suppliers, and customers—most attention has been paid to the conflicting demands on supervisors from superiors and subordinates (Gardner & Whyte, 1945; Smith, 1948). Superiors expect results, initiative, planning, firmness, and structure. Subordinates expect recognition, opportunity, consideration, approachability, encouragement, and representation (Brooks, 1955). Thus Pfeffer and Salancik (1975) demonstrated that superiors expected more task behavior from first-line supervisors whereas subordinates expected more socializing from them. Likewise, Snoek (1966) found that supervisors “in the middle” experienced more conflict than operatives “at the bottom.” Supervisors had a wider diversity of interactions than the operating personnel, and the conflicting demands placed on them led them to experience more role strain.

In military organizations, officers above and enlisted personnel below disagree on what characterizes the good noncommissioned officer in between them (U.S. Air Force, 1952). Factor-analytic studies by J. V. Moore (1953) showed, for example, that subordinates wanted noncoms to be less strict whereas superiors emphasized noncoms’ military bearing and ability. Halpin (1957b) found that commanders of aircrews who highly emphasized consideration were most highly rated by their subordinates, whereas those who most often initiated structure were more likely to be rated effective leaders by their superiors. Similarly, Zenter (1951) noted that 87% of the officers studied thought that a good noncommissioned officer follows orders while only 44% of the enlisted men accepted this idea. At the same time, 49% of enlisted men believed that a good noncommissioned officer has to gain popularity, but only 7% of officers agreed. One discordant note in these findings was that Graen, Dansereau, and Minami (1972b) failed to find the expected discrepancy between subordinates’ and superiors’ role expectations of executives in the middle.

Nonetheless, Lawler, Porter, and Tannenbaum (1968) found that interactions with superiors were more valued than those with subordinates. In addition, the managers reacted more favorably to interactions that their superiors initiated than to those initiated by others. Porter and Kaufman (1959) devised a scale for determining the extent to which supervisors described themselves as similar to top managers. Self-perceptions that were similar to those of top managers were associated with patterns of interaction that peers perceived to be similar to those of managers in high-level positions.

Subordinates whose attitudes and role perceptions were similar to those of their superiors were preferred by their superiors (Miles, 1964a) and rated by them as more effective (V. F. Mitchell, 1968). In turn, subordinates who resembled their superiors in the personality traits “sociable” and “stable” were better satisfied than those who resembled their superiors less closely. Henry (1949) and others found that rapidly promoted executives particularly tended to identify themselves with their superiors. On the other hand, Pelz (1952) found that first-line supervisors who were subordinate oriented tended to be evaluated positively by their workers, but only if they were perceived to have sufficient influence with superiors to satisfy the workers’ expectations.

Balma, Maloney, and Lawshe (1958a, 1958b) studied more than 1,000 foremen in 19 plants. They found that foremen who identified themselves with management were rated as having significantly more productive groups than those who did not identify with their superiors. However, the employees’ satisfaction with a foreman was not related to the foreman’s orientation. R. S. Barrett (1963) discovered that foremen who perceived that their approach to problems was similar to the approach of their immediate superiors tended to feel free to do things their own way. Fleishman and Peters (1962) observed that top-level managers tended to connect the effectiveness of lower-level managers with that of these managers’ immediate middle-level superiors.

Customers and Management. Employees who are in contact with customers face competing expectations from customers and management. Management expects these employees to follow the rules while providing high-quality service. The customers may have requests that require bending the rules. Customers may exacerbate the situation by rewarding the contact employees with tips. Such employees need to balance the competing expectations of customers and managers (Eddleston, Kidder, & Litzky, 2002).

Conflicts between Organizational Levels. Neuberger (1983) viewed the supervisor as the focus of multilateral expectations that could be ambiguous, conflicting, and contradictory. Rules, regulations, and structure do not necessarily provide solutions to such conflicts, which can result in political behavior and unstable leadership behavior. Conflict may arise because there are decided differences in what members at different levels of the organization expect is appropriate behavior for them. L. W. Porter (1959) reported that first-level supervisors viewed themselves as careful and controlled in their approach to the job and to other people. Their second-level managers, in contrast, described themselves as enterprising, original, and bold. First-level supervisors differed from line workers as much as they differed from higher-level managers; they perceived themselves to be significantly more careful and controlled than the workers saw themselves. The first-level supervisory role imposed demands for behavioral patterns that differed from those of superiors and subordinates. A form of conflict that has long been recognized (Coser, 1956) is superior-subordinate conflict involving viewpoints, opinions, and ideas about the task being performed and, on the other hand, tension, animosity, and annoyances—socioemotional, interpersonal incompatibilities (Jehn, 1995). D. E. Frost (1983) reported that for 121 first-level supervisors, perceived conflict in their own role correlated .27 with their boss’s emphasis on production and .35 with conflict with their boss. Consistent with the multiple-screen model of Fiedler, Potter, Zais, et al. (1979), experienced first-level supervisors’ performance was greater if conflict was high with their bosses and declined when conflict was low. The reverse was true of the relationship between the first-level supervisors’ intelligence and their performance.

The conflicts of middle management were reflected in an opinion research poll of 1982, which found that over half the respondents had “lost confidence in their superiors”; 69% saw too many decisions being made (and made poorly) at the top by persons who were unfamiliar with the particular problems (Fowler, 1982). Adding to the middle managers’ malaise was job insecurity, brought on by drastic reductions in middle-management positions in the 1980s (Clutterbuck, 1982a)—a development predicted 30 years earlier by Leavitt and Whisler (1958), who foresaw that dramatic improvements in information processing would substitute for this level of management. The trend continued into the early twenty-first century, when many plants and offices closed because of foreign competition and the movement of companies offshore.

Conflicts with the Boss. Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, et al. (1964) found that 88% of all organizational role conflict involves pressure from above. D. E. Frost (1983) discovered that the boss’s behavior created most of the role conflict and ambiguity for first-and second-level leaders in an urban fire department. Managers were the overriding reason for the role ambiguity and conflict experienced by 123 salaried employees of a metal fabricating firm who were surveyed by Deluga (1986). Jambor (1954) found that when supervisors’ perception of their role differed from their superiors’ perception of it, the supervisors experienced more anxiety than when their role perception differed from their subordinates’ perception of it. Fiedler (1984) amassed considerable evidence to show that when experienced leaders are in conflict with their boss, they tend to be able to maintain productive groups. But intelligent leaders without such experience are handicapped by conflicts with their boss. Experience, not intelligence, helps leaders deal with the stress engendered by conflicts with their own superiors.

Conflicts with Subordinates. Using clinical observation and psychoanalytical theory, Zaleznik (1965a) conceived of four types of malfunctioning subordinates, each representing a type of personality that is in conflict with the demands of a higher authority:

(1) Impulsive subordinates rebel and strive to overthrow authority and its symbols; unconscious motives may be to displace parental authority or to deal with painful loneliness;

(2) Compulsive subordinates also want to dominate the struggle with authority, but they do so passively. Their behavior is rigid, and they avoid making decisions. Underneath, there are doubts, rapid shifts in feelings about interpersonal encounters, hidden aggression, and denial of responsibility, coupled with a power conscience and strong guilt feelings;

(3) Immature early development results in masochists, illustrated by accident-prone employees who evoke sympathy when hurt. Their performance is inadequate and invites criticism and shame. Their identity is with the oppressed, helpless, and weak;

(4) Withdrawn subordinates turn their interests inward and passively submit to a perceived malevolent world and untrustworthy superiors. Although they may handle routine tasks well, they make little effort to be innovative.

Zaleznik’s advice for supervising these four types of subordinates is to avoid being trapped into their dynamics—for example, by reinforcing the doubts of compulsive subordinates or losing control to the impulsive, rebellious subordinates. Conflict with such subordinates needs to be objectified, and conflicting issues need to be broken into their components. Realities need to be recognized.

Discordant Expectations. Discrepancies between people’s expectations about assignments, jobs, or positions and the expectations of their subordinates, peers, superiors, and clients about these assignments, jobs, or positions have been studied extensively as fundamental sources of conflict. Similarly, conflicts arise as a consequence of discrepancies between what is done by people and what ought to be done. Thus Colmen, Fiedler, and Boulger (1954) reported little agreement among 45 leaders in the U.S. Air Force in evaluating their own duties. Further confusion resulted from a discrepancy between what potential leaders thought they ought to do and what they actually did. Halpin (1957b) found little relationship between how aircraft commanders and school superintendents said they might behave and how their subordinates said they actually behaved.

Stogdill, Scott, and Jaynes (1956) asked officers at various levels of a large naval organization to describe what they did and what they ought to do. In addition, their direct reports described what the immediate superiors did and ought to do. The subordinates’ self-expectations were much more highly related to their expectations for their superiors than were their self-descriptions to their descriptions of their superiors. Subordinates entertained similar expectations for themselves and for their superiors, but their descriptions of their own and their superiors’ behavior were not as similar. Except for handling paperwork and other forms of individual effort, they did not perceive that their own behavior resembled that of their superiors. Discrepancies between superiors’ self-descriptions and self-expectations were highly related to their level of responsibility.2 Superiors who obtained high scores from their subordinates on level of responsibility perceived themselves as having too much responsibility and as acting as representatives of their followers more extensively than they should. They also reported spending too little time inspecting the organization and too much time on paperwork and engaging in all forms of leadership behavior. Discrepancies between subordinates’ self-descriptions and self-expectations were greater at higher organizational levels where their superiors were recipients of frequent interactions. Under these conditions, the subordinates perceived themselves to be doing more than they should in attending conferences, interviewing personnel, handling paperwork, and representing their own subordinates. When a superior delegated a great deal, the subordinates thought that they had been given too much responsibility, and spent less time than they should on coordination and professional activities.

Along similar lines, Triandis (1959a) found that the smaller the discrepancy between workers’ ideal supervisor behavior and actual descriptions of their supervisors’ behavior, the better the supervisor was liked by the workers. Results obtained by Holden (1954) indicated that the more a leader’s behavior conformed to the group members’ expectations, the more productive the group was. Havron and McGrath (1961) suggested that the leaders of highly effective groups either behave as expected or are successful in inducing group members to form ideals that are similar to the leaders’ actual behavior. Thus Foa (1956), who studied supervisors and workers in Israeli factories, found that these supervisors and workers agreed on the ideal behavior for a supervisor, but that they did not agree on what the supervisor actually did. The more agreement there was between the ideal and perceived behavior of the supervisor, the better satisfied the workers were with their supervisor. Workers who identified with their supervisor tended to attribute to the supervisor the ideals that they held. Ambivalent workers attempted to conform to the ideal attributed to their supervisor but were aware of the supervisor’s deviation from it. Indifferent workers felt less inclined to accept the ideal of the supervisor in their own behavior and were also less likely to notice discrepancies between the supervisor’s ideal and real behavior. However, F. J. Davis (1954) failed to corroborate these effects among U.S. Air Force officers: in his study the successful adjustment of the followers did not depend on their agreement with the leader about the leader’s role.

Other Sources of Within-Role Conflict. Differences in perceived needs, values, interests, and goals are structural sources of conflict among managers at different hierarchical levels as well as between leaders and followers in the community. For example, Fiedler, Fiedler, and Camp (1971) found that whereas community leaders thought poor government, neighborhood disunity, and the failure of public services were the concerns of consequence, householders believed that crime, immorality, traffic, and unemployment were the issues that needed attention. Managers and union leaders both generally overemphasize the importance of pay as a source of dissatisfaction of employees and underemphasize the importance of such concerns as security, job satisfaction, and opportunity (Bass & Ryterband, 1979).

Contradictory demands may stem from discrepancies between one’s immediate work group and one’s reference group. At some colleges, professors may be caught between the demands of their cosmopolitan, professional, research-oriented reference groups and the role demands of their local campus for high-quality teaching and good relations with students. Industrial scientists may be caught between their professional reference groups’ demand that they get their work published and their business firms’ demand for secrecy. These conflicts are a source of dissatisfaction, as was illustrated in an industrial study by Browne and Neitzel (1952), who found that workers’ satisfaction declined as the disagreement between what their leaders demanded of them and what was wanted by their reference groups increased. Jacobson (1951) and Jacobson, Charters, and Lieberman (1951) studied foremen, union stewards, and workers. The fore-men expected the stewards to play a passive role in the organization, whereas the stewards and the workers expected the stewards to play an active role on behalf of employees and the union. Foremen and stewards whose expectations deviated from the norm of their reference group got along more easily with each other.

Supervisors in training are often caught in a conflict when their managers are opposed to what the supervisors are being taught by their trainers. Furthermore, trainers are more likely to succeed in modifying the supervisors’ behavior if their bosses show interest in the training program, participate in its development, and take the training course first (W. Mahler, 1952). Politicians must continually cope with conflict between what they must do and what they would prefer to do. They must choose between what they find expedient and what they know is right. Personal integrity has to be sacrificed to unholy alliances. Henry IV of France, a Protestant Huguenot, converted to Catholicism because “Paris is well worth a mass.” For Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin, making a deal with each other in 1939 bought them time. For President Dwight D. Eisenhower, keeping silent in the face of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s virulent attacks on George Marshall, Eisenhower’s close friend, was justified as a means of maintaining the Republican coalition. Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush both embraced the agenda of the far right while campaigning for election but tended to give a lower priority to many of the right wing’s demands once they were elected.

Punctuality. Some celebrities, such as Madonna and Elizabeth Taylor, have been noted for being chronically late for appointments. Politicians such as Bill Clinton and Jesse Jackson were likewise known for showing up late for meetings. According to Janine Braier, “Being late is a statement; if you are chronically late … it’s a way of saying ‘you need me but I don’t need you.’ … I never want to have the experience of needing someone. I always want them to want me.” People who are habitually late usually are overloaded with tasks and somehow schedule impossibilities into their workdays. They deny the reality that by being late they are delaying others. They feel omnipotent and in complete control. Being late may be a way of deliberately manipulating time to emphasize one’s own importance and others’ dependence (Jennings, 1999, p. 18).

Identification. Racial, ethnic, and national identification is well known as a source of conflict. Conflict may then be exacerbated by divergent beliefs based on historical memories, “we-they” polarization, religious intolerance, and economic, social, and political privileges (Rouhana & Bar-Tel, 1998). But Kelman (1999), in discussing the continuing Israeli-Palestinian confrontation and each side’s negative identification with the other, is realistic, also noting positive interdependence (Palestinians are a source of labor for Israel; Israelis are a source of jobs for Palestine). The leaders of both sides must work to change the beliefs of their own people that they are the victims and the other side are the aggressors.

Identification with superiors or subordinates appears to be a key to understanding the man or woman in the middle. Potential conflicts with supervisors and subordinates depend on with whom identification and similarity are sought. Thus Pfeffer and Salancik (1978) observed that when leaders were more responsive to their subordinates’ demands, the leaders’ characteristics and activities were more like those of their subordinates. The leaders were more responsive to their bosses’ pressure to produce when the leaders’ activities were more like those of their own superiors. A second study found that supervisors who were required to engage in a great deal of peer-oriented interdepartmental coordination were less likely to be responsive to their subordinates.

D. T. Campbell and his associates developed various methods of measuring identification with superiors and subordinates. Of the variety of independent sub-scales that emerged (Campbell, Burwen, & Chapman, 1955), the most promising were identification with discipline, superior-subordinate orientation, and eagerness for responsibility and advancement. Identification with superiors rather than subordinates correlated .21 with authoritarianism, .25 with identification with discipline, and –.20 with cooperation (Chapman & Campbell, 1957a). Paradoxically, those of higher rank appear to be less concerned about their superiors and more concerned about their subordinates. Campbell and McCormack (1957) found that colonels in the U.S. Air Force were significantly less oriented toward superiors than were Air Force majors or college men, and majors were less so than Air Force cadets or their instructors. Furthermore, Air Force majors and lieutenant colonels were significantly more subordinate-oriented than the other groups tested.

Generational Conflict. A generational conflict resulting in a lack of identification with senior leadership was suggested as a cause of an expected 13% attrition of U.S. Army captains in just one year, 2001. The captains were members of the cohort called Generation X, who were born between 1960 and 1980. Above them in rank from major to general was the baby-boomer generation, whose members were born between 1943 and 1960. The Generation Xers tended to have more divorced, two-career parents, more disruptive families, and less idyllic childhoods than the baby boomers, whose families were more stable, with parents in more traditional roles. Compared with Generation Xers, baby boomers value work and promotion as more important. Baby boomers are more likely to be workaholics. In contrast, Generation Xers value having more free time, more friendships, and a better family life (Wong, 2000).

Both the leader and the led determine whether conflicts can be readily reduced or resolved. Among the six factors that identified the effective manager, Morse and Wagner (1978) found one that involved the ability to deal with conflict among colleagues and associates and to avoid continuing conflicts that got in the way of completing assignments. Walton (1972) noted that effectiveness as a leader was associated with the ability to convert conflicts of interests among subordinates and colleagues into accommodation, conciliation, compromise, and, better yet, consensual agreement. Effective leaders did not run away from conflict or try to deal with it arbitrarily.

In contrast with transactional leaders, transformational leaders seem to have more ability to deal with conflict. They are less readily disturbed by it, possibly because they are “more at peace with themselves.” Gibbons (1986) reached this conclusion on the basis of in-depth interviews with 16 senior executives in a high-technology firm identified as transformational or transactional by peer nominations and by subordinates’ descriptions of them on the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (Bass & Avolio, 1989).

In organizational mergers, a source of considerable conflict, the acquired employees are more satisfied with the merger when their leaders are transformational (Covin, Kolenko, Sightler, et al., 1997). Followers also make a difference. Lien, Kottke, and Agars (2003) found that emotional conflicts among 84 employees of public organizations in southern California were lessened by collectivistic rather than individualistic attitudes and by tolerance for multicultural diversity.

Conflicts may be resolved or lessened if the leaders and the led have dual loyalties. They may be loyal both to the management and to the union in conflict. They may have interests in both the organization and its members. They may want to remain concerned about the feelings of both their superiors and associates who may be in conflict.

Conflicting interests may be overriden by multiple identifications and allegiances. Potential conflicts may be reduced, avoided, and even resolved because people who are members of two groups or organizations with conflicting interests may consider themselves loyal to both. For example, Stagner (1954) obtained a correlation of .33 between the favorableness of workers’ attitudes toward their company and toward the union. Purcell (1954) found that although more workers identified with the company than with the union, 73% of the men and women surveyed expressed loyalty to both. Supervisors and stewards each identified with the organization that they represented officially, but both supervisors (57%) and stewards (88%) generally felt favorable toward the others’ organization. In a case study of 18 supervisors at a British shoe factory, Armstrong (1983) was chagrined (because of his Marxist orientation) to find that despite the supervisors’ resentment about their deteriorating income and status relative to the workforce, they remained loyal to the senior management. For Armstrong, this continuing loyalty to senior management meant that the supervisors failed to recognize their interests as members of the working class who were exploited by the capitalist senior management.

Obrochta (1960) obtained results indicating that supervisors and workers were most similar regarding their attitudes toward the company and least similar regarding their attitudes toward union leaders. The supervisors’ attitudes toward both the union leaders and the company were more favorable than those of the hourly workers, and the attitudes of the hourly workers toward the union were more favorable than the supervisors’. Obrochta also found that the workers’ attitudes toward their foreman were somewhat more favorable than the supervisor’s attitude toward them. Further evidence on reciprocity or the lack of it was gathered by Derber, Chalmers, Edelman, et al. (1965) in a study of 37 industrial plants. The results indicated that managers’ attitudes toward the union and union leaders’ attitudes toward the management were positively and significantly correlated; each group was moderately favorable in its attitude toward the other. Obviously, there are variations and exceptions. For instance, Stagner, Chalmers, and Derber (1958), using separate scales for measuring attitudes toward the company and the union, found no relation between the management’s attitudes toward the union and the union’s attitudes toward the management. Yet in many firms, managers and union officials regard each other in generally favorable terms, despite the conflict between them about substantive issues, particularly issues involving their respective powers. Investigating managers in a southern city, Alsikafi, Jokinen, Spray, et al. (1968) suggested that unfavorable managerial attitudes toward the union tended to be connected with the inclusion in labor contracts of union security clauses that the managers perceived as challenging their authority to manage. Spillane (1980) noted that in contrast to a survey done in 1959, a survey done in 1978 found that the gap between the attitudes of Australian union leaders and Australian business executives had narrowed substantially. Both groups in the later survey strongly supported arbitration as a way of resolving industrial disputes. On the other hand, Edwards and Heery (1985) noted that when the interests of shop floor democracy in 35 British collieries came into conflict with the interests of union officials or national interests the local leaders upheld the concern for shop floor democracy.

In a plant of 3,400 employees, in which top management and union leaders espoused cooperation and mutual confidence, one-fourth of the shop stewards did not share information with the shop supervisors, and half of the supervisors held back from sharing information with the stewards. Yet in a survey of 263 U.S. firms, information exchange was reported as the most frequent form of union-management cooperation.

As elected officers appealing to their constituents, union leaders need to publicly enunciate more extreme points of view than their counterparts in management (Bass, 1965). To study perceptual distortions between 76 union officers in a central labor council and 108 human resources executives, Haire (1948) showed photographs of two middle-aged men to half of a sample: one photo was identified as secretary-treasurer of a union, the other as the local manager of a small plant. The identifications were switched for the other half of the sample. The union officials used a checklist to describe the photo identified as a union secretary-treasurer as that of a man who was conscientious, honest, trustworthy, responsible, considerate, cooperative, fair, and impartial. The human resources executives were even more complimentary in describing the same photo as that of a plant manager.

Differences in communication behavior show up when union stewards are compared with counterparts who are plant supervisors. Nonetheless, dual allegiance to the union and the company is the rule rather than the exception. This was seen in interviews with 202 employees in the garment, construction, trucking, grain processing, and metalworking industries. If the employees had favorable attitudes to either the union or the company, they had favorable attitudes toward the other as well. Dual allegiance was found in 73% of packinghouse employees, 88% of union stewards, and 57% of company supervisors (Purcell, 1953).

Three of every four first-line supervisors who were rated as promotable by their superiors were described by their subordinates as pulling for both the employees and the company. Only 40% of those seen as less worthy of promotion were so described (Mann & Dent, 1954b). Simultaneous upward and downward orientation and sensitivity are required of the effective supervisor, as a person in the middle. Sarbin and Jones (1955) reported that a successful supervisor not only is competent in the eyes of superiors but fulfills the expectations of subordinates. According to Wray (1949), this is not an easy task, since superiors and subordinates present conflicting expectations that are difficult to reconcile. Nonetheless, in his study of an industrial plant, H. Rosen (1961a, 1961b) found that managers could have an upward orientation toward the demands of their superiors while remaining sensitive to the demands of their subordinates. The experience of supervisors in their subordinates’ jobs has been found to be of consequence. Maier, Hoffman, and Read (1963) compared managers who had previously held the jobs of their subordinates with peers who had not held these jobs. Subordinates trusted mutual agreements about their current problems only when the agreements were made with managers who had previously been in the subordinates’ jobs, although a manager’s previous assignment to a subordinate’s job did not facilitate effective communication.

Conflict has a tendency to escalate and to be exacerbated by mirror imaging—attributing opposite qualities to the opposition in a conflict. Thus, “we” are honest, just, rational, and benevolent; “they” are dishonest, unjust, emotional, and malevolent. Leaders of groups, organizations, and nations tend to exploit and exaggerate these opposing attributions, as was seen among Americans who exhibited mirror imaging of Iranians soon after the American hostages were seized in Tehran in 1979 (Conover, Mingst, & Sigelman, 1980). However, McPherson-Frantz and Janoff-Bulman (2000) found in an experiment with college students about parent-adolescent conflict that partisanship could be ameliorated to the extent that partisans liked the opposing party. Instructions to be fair and unbiased resulted in reducing attention to arguments from both sides but also bolstered original partisan perspectives.

The marked decline in union membership in the United States in the past half century has been paralleled by a decline in studies of union-management relations. Furthermore, there has been a shift in unionization from industrial business to governmental agencies. Despite mirror imaging, K. F. Walker (1962) found that managers and union leaders were accurate in predicting each other’s attitudes, but both perceived more conflict than actually existed. Supervisors and shop stewards who wanted the company and union to coexist amicably experienced more stress than normal and tended to hold favorable attitudes toward each other (Purcell, 1954). However, the underlying bases for evaluating the management and the union differed. Stagner, Derber, and Chalmers (1959) surveyed the attitudes of two labor leaders and two managers in each of 41 establishments. When they computed a composite score for each establishment for each of 35 attitude and satisfaction variables, they found that the management’s evaluation of the union emerged as a single general factor but that the union’s evaluations were denoted by two factors, one involving union-management relations and the other concerned with the union’s achievements (1949). Miller and Remmers (1950) examined the attitudes of managers and labor leaders toward human relations–oriented supervision. Managers tended to overestimate labor leaders’ scores, whereas labor leaders underestimated managers’ scores. In a comparative study of managers and union officials, Weaver (1958) found, as expected, that union officials exhibited strong prolabor attitudes. But not as obviously, managers were neutral about grievances, arbitration, the labor movement, and working during a strike.

Schwartz and Levine (1965) compared the interests of managers and union officials in the same companies. The managers scored higher on interest in supervisory initiative and production, and the union officials scored higher on interest in seeking power and in propaganda, bargaining, arbitration, and disputation. Similarly, Bogard (1960) compared the values of management trainees and labor leader trainees and found that management trainees scored higher in aggressiveness and lower in altruistic values than the union trainees.

The management of conflict is an important component of most leadership roles. Thomas and Schmidt (1976) reported that middle managers spent more than 25% of their time dealing with conflict with their colleagues. The figure was even higher for first-line supervisors. Often, managing a conflict may involve gaining the acceptance of a resolution by persuading the conflicting employees, groups, or organizations that the proposed settlement will bring more benefits and less cost to both parties than continuing the dispute.

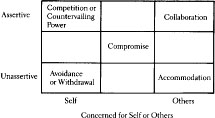

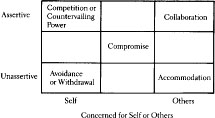

Leaders can manage conflict with supportive, friendly, obliging, compromising, and integrative efforts to move the parties from a competitive to a cooperative stance (Musser & Martin, 1988). The conflict between the felt security of employees in the old ways of doing things and changes required by new demands can be managed by a leader who instills pride in the past coupled with a need to meet the challenges of the future (Tichy & Devanna, 1986). According to Oscar Arias, a former president of Costa Rica, reelected in 2006, who has frequently been involved in international negotiation of conflicts, the negotiator needs patience but not passivity, perseverance but not inflexibility, commitment and respect for others’ viewpoints, skills in building trust, and the ability to compromise in good faith.

Diagnosis of the causes of a conflict is a rational way to begin to manage it. For example, if a conflict is due to a failure to match status and esteem, it can be reduced by incorporating the results of subordinates’ evaluations of esteem into promotional policies or building up the esteem of those with high status. If conflict is anticipated because of a rise in status of one member at the expense of the others, it can be avoided by bringing in an outsider to lead the group (Bass, 1960). Kabanoff (1985a) proposed a typology of conflict situations. Each type suggested a relevant rationale for its management. For instance, if a diagnosis showed that the team members’ esteem was lower than their actual ability and expertise, public praise could be used to increase their esteem. In addition, counseling could help peers increase their acceptance of expert but unesteemed members.

Kabanoff (1985a, 1985b) provided a list of diagnosed intrapersonal conflicts, such as conflict between one’s status and esteem, with implied or self-explanatory strategies for handling them. In addition, tactics were suggested for dealing with conflicts of status and esteem, when conflicts arose between low esteem and high-needed ability, low committment and high centrality, low popularity and high status, incompatability and required collaboration, low ability and required-high ability, low ability and high status, and low ability and a highly critical task.