A leader is transactional when the follower is rewarded with a carrot for meeting agreements and standards or beaten with a stick for failing in what was supposed to be done. If the leader is limited to such behavior, the follower will feel like a jackass (Levinson, 1980b). Leaders must also address the follower’s sense of self-worth, one of the things that transformational leaders do. Transformational leaders motivate their followers to do more than the followers originally intended and thought possible. The leader sets challenging expectations and achieves higher standards of performance. Transformational leadership looks to higher purposes. Transformational leaders are expected to cope better with adversity (Parry, 2005). Parameshwar (2003) noted that 10 global leaders of social change developed transcendental higher purposes and went beyond the ordinary by: (1) exposing unresolved, disturbing human rights problems; (2) untangling false interpretations of the world; (3) breaking out of conventional solutions; and (4) making use of transcendental metaphors. Many leaders of world religions, such as Jesus, Mohammed, and Buddha, were transforming. They created visions, shaped values, and empowered change (Leighton Ford, 1981). Both transactional and transformational leadership were demonstrated by the Greek leaders of the Anabasis (Xenophon, c. 400 b.c.e.) marching the mercenary Greek army safely through 1,000 miles of hostile Persian territory (Humphries, 2002).

Transactional leadership emphasizes the exchange that occurs between a leader and followers. This exchange involves direction from the leader or mutual discussion with the followers about requirements to reach desired objectives. Reaching objectives will appear psychologically or materially rewarding. If not overlooked or forgiven, failure will bring disappointment, excuses, dissatisfaction, and psychological or material punishment. If the transaction occurs and needs of leader and follower are met, and if the leader has the formal or informal power to do so, he or she reinforces the successful performance.

Up to the late 1970s, leadership theory and empirical work were concentrated almost exclusively on the equivalent of transactional leadership. The exceptions were political, sociological, and psychoanalytical discussions of charisma. Today both transformational and transactional leadership have a wide range of applications, ranging from teaching and nursing to police work and personal selling (Jolson, Dubinsky, & Yammarino et al. 1993).

Freud (1922) recognized that leadership was more than a transactional exchange. The leader embodied ideals with which the follower could identify. Bernard (1938) noted in his examination of corporate executives that tangible inducements were less powerful than personal loyalties. Hook’s (1943) heroes in history made events as well as waiting for them to happen. Political leaders could be reactionary, conservative, reforming, radical, or revolutionary agents of change (Dvir, 1998).

Transformational leadership was first mentioned, as such, by Downton (1973) as different from transactional leadership. Soon after, House (1977) presented a theory of charismatic leadership with testable hypotheses. But with perspectives from Maslow’s needs hierarchy and from writing biographical studies of Presidents Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy, in a book entitled Leadership, James MacGregor Burns (1978) opened wide the impetus for research to contrast transformational leadership to transactional leadership as its opposite. This was followed by Bass (1985a), who demonstrated that empirically transformational and transactional leadership were two positively correlated dimensions. Furthermore, transformational added to transactional leadership effects.

Empirical leadership research up to the late 1970s attended mainly to observable, short-term, leader-follower relations in small groups on the micro level of organizations. There was much less empirical research about senior executives and heads of organizations at the macro level or leaders of societies at the meta-level, although much had been written about leadership at the higher levels. In the mid-1970s, the survival of the field of leadership study was seriously questioned. In 1975, a commentator was reported to have quipped, “Once I was active in the leadership field, Then I left it for about 10 years. When I returned, it was if I had been gone only 10 minutes” (Hunt, 1999, p. 130). In 1975, John Miner argued that “the concept of leadership itself has outlived its usefulness” (Hunt & Larson, 1975, p. 200). Some theorists and practitioners thought the concept of leadership might whither away. They suggested that what was attributed to effective leadership could better be explained by social, organizational, and environmental effects (Pfeffer, 1977). Leadership was thought to be a fiction of the imagination, overemphasized in the highly individualistic United States (Hosking & Hunt, 1982). According to Hunt (1999, p. 130),

the study of charismatic and transformational leadership came in to save the day. … [A] major contribution, if not the major contribution of transformational and charismatic leadership has been its transformation of the field. This transformation involves a field that had been rigorous, boring and static … examining more and more inconsequential questions and providing little added [by] the plethora of published studies.

Transformational leadership represented a seminal shift in the field of leadership (Bass, 1993).

The New Leadership. Bryman (1992) labeled as the “new leadership” the introduction of transformational leadership and related concepts such as charismatic, visionary, inspirational, values-oriented, and change-oriented leadership. House and Aditya (1997) referred to these concepts as neocharismatic. The new leadership represents a paradigm shift that moved the field out of its doldrums (Hunt, 1999). Along with reinforcing the importance of transformational leadership, Burns (2003) agreed with Thomas Jefferson about the importance of leadership in the pursuit of happiness. Evidence of the transactional and transformational behavior of leaders in a wide variety of circumstances, political, business, education, family, sports, and law enforcement (Bass & Riggio, 2006) is well documented. Less well known is street-level transformational leadership of social caseworkers with their disabled or welfare clients (Dicke, 2004)

Burns (1978) defined a transforming leader as one who: (1) raises the followers’ level of consciousness about the importance and value of designated outcomes and ways of reaching them; (2) gets the followers to transcend their own self-interests for the sake of the team, organization, or larger polity; and (3) raises the followers’ level of need on Maslow’s (1954) hierarchy from lower-level concerns for safety and security to higher-level needs for achievement and self-actualization. Transforming leadership elevates the follower’s level of maturity, ideals, and concerns for the well-being of others, the organization, and society. The content of transformational leaders tends to be optimistic (Berson, Shamir, Avolio, et al. (1998). Transforming leaders point to mutual interests with followers. They engage followers closely without using power, using moral leadership. They transform individuals, groups, organizations, and societies. Between 1980 and 1985, Bass (1985a) formulated a multidimensional theory of transformational and transactional leadership and verified it with military and civilians describing their respective leaders. Burns agreed that transformational and transactional leadership were not opposite ends of a single dimension but multidimensional.

Measurement. Seventy senior South African executives (all male, one black) described how one such leader they had known in their careers had influenced them. Their descriptive statements were sorted by 11 graduate students into transformational and transactional. Seventy-three of the 143 statements on which the judges could agree were administered to 104 senior U.S. Army officers (almost all male). The officers were asked to describe their most recent superior, using a five-point scale of frequency, from 0 = the behavior is displayed not at all to 4 = the behavior is displayed frequently, if not always.

A first factor analysis of the 73 items was completed (Bass, 1985c) The factors described the behavior and attitudes of transformational and transactional leaders in three correlated transformational leadership factors: (1) charisma, (2) intellectual stimulation, and (3) individualized consideration. Later a cluster of three items was identified as inspirational motivation. Also, two transactional factors emerged that reflected positive and negative reinforcement, respectively: (4) contingent reward and (5) management by exception. They were uncorrelated with each other. Subsequently, Bass and Avolio (1990) relabeled the charismatic factor idealized influence because of the popular meaning of charisma in the public mind as being celebrated, flamboyant, exciting, and arousing. It was often a highly publicized creation of media hype. It was also associated pejoratively with Hitler’s effects on the German people.

Charisma was the subject of Chapter 21. As Bass (1985a) and others noted, it could not be separated factorially from inspirational leadership (Hinken & Tracey, 1999). Nevertheless, the charismatic leader is likely to be transformational, but it is possible—although unlikely—to be transformational without being charismatic. A highly intellectually stimulating teacher, for instance, may transform students without their regarding the teacher as charismatic.

Although inspirational motivation could not be separated factorially from charisma because of the conceptual differences between charisma and inspiration discussed in the previous chapter, a 10-item scale of inspirational motivation was maintained in the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire-Form 5X along with the other factor scales (Bass, 1985c).

This is probably the least recognized of the transformational factors. Avolio (1999) pointed out that a majority of managers and employees believe that their intellect is underutilized, yet in the postindustrial world an organization’s intellectual capital may be more important than its physical capital. Worldwide, at least 40 idea generation methods are known, but often they remain misunderstood and mistrusted by skeptics. Some, using intuitive association, such as brainstorming, are well known; others, involving systematic variation and idea structuring, less so (Geschka, von Reibnitz, & Storvik, undated). It is an intellectually stimulating challenge to persuade a group to use any one of these methods and to teach it how to do so.

Bass (1985a) obtained a factor of intellectual stimulation in U.S. Army officers’ MLQ descriptions of their superiors. Many subsequent factor analyses replicated this finding with a variety of samples of military, industrial, and educational managers and leaders (Avolio, Bass, & Dong, 1999; Antonakis, 2000). Items of this factor included such statements as “Provides reasons to change my way of thinking about problems,” “Stresses the use of intelligence to overcome obstacles,” and “Makes me think through what is involved before taking actions.”

Personal Creativity versus the Intellectual Stimulation of Others. There is a difference between possessing competence, knowledge, skill, ability, aptitude, and intelligence and being able to translate these qualities into action as intellectual inspiration and the stimulation of others. Presidents Jimmy Carter and Herbert Hoover exemplified technically competent leaders who failed to inspire. John F. Kennedy and Franklin Delano Roosevelt are illustrations of presidents who were not as intellectually astute as Carter and Hoover but were far superior in their ability to stimulate others intellectually, to imagine, to articulate, and to gain acceptance of and commitment to their ideas. The proposals and ideas of Daniel Patrick Moynihan, the liberal Democratic senator from New York, were repeatedly ahead of his time. He introduced original and provocative ideas that often stimulated liberal opposition rather than support. His 1965 report suggested that the black family was falling apart and social legislation was needed. He was roundly attacked by blacks and liberals. It was only in the 1980s that adverse black family statistics revealed Moynihan as a visionary. In 1970, he supported a guaranteed annual income for the impoverished. It was shot down by the Welfare Rights Organization with rightwing assistance. Welfare reform had to wait until 1988, when he supported the beginnings of workfare legislation. “No politician is as good as Moynihan at generating good ideas … (but not) getting things done” (Lemann, 1990, p. 4).

Intellectual stimulation is much more than a matter of broadcasting good ideas. For instance, in the public sector, Roberts (1988) demonstrated that the intellectual generation of ideas and framing of problems were not enough. Makers of politically innovative policies have to serve as catalysts by: (1) mobilizing and building support for their ideas; (2) circulating their ideas through various media available to them; (3) collaborating with other highly visible and reputable groups and organizations; (4) creating demonstration projects; (5) sponsoring reforms in the legislature; (6) positioning and developing supporters in the government; (7) enlisting champions to introduce their proposed legislation; (8) influencing and creating public interest groups and associations; and (9) monitoring and evaluating the extent to which the legislation that is passed conforms to the policies that were promoted.

What Leaders Do To Be Intellectually Stimulating. Intellectually stimulating leaders help to make their followers more innovative and creative. They question assumptions, reframe problems, and look at old problems in new ways. Public criticism of followers and their mistakes is avoided. New ideas are sought from followers. They are encouraged to “think out of the box,” to address problems, and to consider alternative solutions (Bass, 1998). Intellectually stimulating leaders see themselves as part of an interactive creative process (Brown, 1987). Not bound by current solutions, they create images of other possibilities. Orientations are shifted and awareness of the tensions between visions and realities is increased.

Intellectually stimulating leaders are often empowering (Spreitzer & Janasz, 1998). They move subordinates to focus on some things and ignore others. A pattern is imposed on a flow of events to simplify their complexity and diversity. The real world is made easier to understand (Bailey, 1983). Intellectual stimulation can move subordinates out of their conceptual ruts by reformulating the problem that needs to be solved. Wicker (1985) provided numerous examples of what can be done to move followers to “think out of the box.” Ideas can be played with by applying metaphors and similes (e.g., interpersonal attractiveness is like a magnetic field). The scale can be changed (e.g., a sandbar can be likened to a galaxy of stars). The absurd or fantasy can be considered (e.g., suppose water floated on oil). Alternative states can be imagined, such as particles becoming a wave. Nouns can be changed into verbs. The figure and ground can be transposed (e.g., to concentrate on the space around the object instead of the object). Contexts can be enlarged or subdivided. Hidden assumptions can be uncovered (e.g., failures may be due to poor planning, not to lack of ability). Infante and Gordon (1985) noted that it was more satisfying to subordinates if their supervisors argued for their own formulations and refuted other points of view, but it was more dissatisfying if the supervisors attacked subordinates’ self-concepts. Unfortunately, some people mistake argumentation for hostility. The former is favored in leaders; the latter is not.

Quinn and Hall (1983) proposed that leaders intellectually stimulate followers in one of four ways: rational, existential, empirical, and ideological. Rationally oriented leaders emphasize ability, independence, and hard work. They try to convince colleagues to use logic and reason to deal with the group’s or organization’s problems. Existentially oriented leaders try to move others toward a creative synthesis by first generating various possible solutions in informal interactions with others and their common problems. Empirically oriented leaders promote attention to externally generated data and the search for one best answer from a great deal of information. Idealists encourage speedy decisions; they foster the use of internally generated intuition. They gather only a minimum amount of data before reaching a conclusion (Quinn & Hall, 1983).

Intellectually stimulating leaders see themselves as part of an interactive creative process (Brown, 1987). Not bound by current solutions, they create images of other possibilities. Orientations are shifted, awareness is increased of the tensions between visions and realities, and experiments are encouraged (Fritz, 1986). Intellectual stimulation contributes to the independence and autonomy of subordinates and prevents habituated followership, characterized by the unquestioning trust and obedience of charismatic leader-follower relations (Graham, 1987). Intellectual stimulation is much more than a matter of broadcasting good ideas.

Chaffee (1985) suggested that three strategies are pursued in finding solutions to the organization’s problems: linear, adaptive, and interpretive. If linear data are gathered and analyzed, alternative actions are formulated with expected outcomes if a particular action is taken. If an adaptive strategy is pursued, the effort will be to adjust the organization to environmental threats and opportunities by being particularly cognizant of the revenues and resources needed from the environment. If an interpretive strategy is pursued, reality is less important than are perceptions and feelings about it. Values, symbols, emotions, and meanings need to be addressed. Neumann’s (1987) interview study of 32 college presidents found that with experience, the presidents tended to move toward more interpretive strategies if they had not initially emphasized them. The shift of experienced presidents away from purely adaptive strategies was most evident.

Military and political planners need to be encouraged to engage in second-curve thinking. They need to develop alternative possible scenarios of what is likely to happen after the victory they have planned for. In the same way, planners for organizations need to consider looking at alternative scenarios of how the organization and its environment is likely to be affected by the success of their first-curve plans. Royal Dutch Shell executives draw up such possibilities and distribute them widely to keep its executives thinking ahead to avoid being surprised (Handy, 1994). There was insufficient and inadequate second-curve thinking by the U.S. administration about what would happen in Iraq after the initial success of its first-curve plan to bring down Saddam Hussein’s regime (Woodward, 2004).

Central versus Peripheral Routing. Intellectual stimulation takes people on what Petty and Cacioppo (1980) conceived of as the central route to being persuaded, which occurs when people are ready and able to think about an issue. It may be contrasted to persuasion via the peripheral route, which occurs when people lack either motivation or ability. Persuasion through the central route produces enduring effects; persuasion via the peripheral route lasts only if it is bolstered by supportive cognitive arguments. If persuasion is by the peripheral route, it is necessary only for the source of the persuasion to be liked. The distinction between central and peripheral processing has much in common with the distinctions between deep versus shallow processing, controlled versus automatic processing, systematic versus heuristic processing, and thoughtful versus mindless or scripted processing (Cialdini, Petty, & Cacioppo, 1981).

Individually considerate leaders pay special attention to each follower’s needs for achievement and growth. New learning opportunities are created, along with a supportive climate. Individual differences in needs are recognized. The leaders serve as coaches and mentors for their followers. They attend to the individual followers’ differential needs for growth and achievement. Followers are helped to reach successively higher levels of development. New learning opportunities are created in a supportive environment. “Walking-around management” is practiced. The individually considerate leader personalizes relations, remembering names and previous conversations. Two-way communication is encouraged. Tasks are delegated to provide experience and to develop followers. The individually considerate leader is an effective listener (Bass, 1998) and more delegative in management style (Gill, 1997).

Bracey, Rosenbaum, Sanford, et al. (1990) stated that leaders need to be caring by telling the truth with compassion, looking for others’ loving intentions, disagreeing with others without making them feel wrong, avoiding suspiciousness, and recognizing the qualities in each individual regardless of cultural differences. Greenleaf’s (1979) servant leadership heavily emphasizes individualized consideration.

When faced with changed processes making employees redundant or the need to cut costs, individually considerate management restructures the organization responsibly (Cascio, 1995). Whenever possible, employees are retrained and redeployed to avoid layoffs. Merck even arranged for temporary transfers of employees to other firms. Actually, it may be less profitable for firms to downsize to cut costs because of the expense of separations and rehiring when business turns around (McKinley, Sanchez, & Scheck, 1995).

Although they are conceptually different and form independent clusters of items, the component factors of transformational leadership uncovered by Bass (1985a) are intercorrelated. Sixty-six percent of the covariance of all the items in transformational leadership could be accounted for by the first factor of charismatic leadership (Bass, 1985c). An even larger amount was accounted for in a comparable sample of U.S. Air Force officers (Colby & Zak, 1988). Hater and Bass (1988) achieved similar results when they refactored the 70-item questionnaire that subordinates completed to describe their immediate management superiors. Onnen (1987) obtained similar findings from 454 parishioners who described their Methodist ministers. A single transformational leadership score can be meaningfully calculated for selected studies and analyses. The antecedents and effects of this transformational score have been compared with the effects of transactional leadership that is composed of the factors of contingent reward and management by exception. The results of extensive surveys of more than 1,500 general managers, leaders of technical teams, government and educational administrators, upper middle managers, and senior U.S. Army officers that were discussed earlier for charismatic leadership are also relevant for transformational leadership. Subordinates of these leaders, who described their managers on the MLQ-Form 5 as being more transformational, were also more likely to say that the organizations they led were highly effective. Such transformational leaders were judged to have better relations with higher-ups and to make more of a contribution to the organization than were those who were described only as transactional. Subordinates said they also exerted a lot of extra effort for such transformational leaders. If leaders were only transactional, the organizations were seen as less effective, particularly if most of the leaders practiced passive, reactive management by exception intervening only when standards were not met.

According to Burns (1978), transactional leadership is the exchange relationship between leader and followers aimed at satisfying their own self-interests. Its factors in Bass (1985c) were contingent reward and management by exception. The latter factor was subsequently divided into active management by exception and part of passive leadership and laissez-faire, the avoidance of leadership, delineated in Chapter 6. Contingent reward and management by exception are ways of looking at reinforcement leadership, discussed in Chapter 15. With active management by exception, the leader attends to each follower’s performance and takes corrective action if the follower fails to meet standards. With passive management by exception, the leader waits for problems to arise in the follower’s performance before taking corrective action in the belief that “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” (Bass & Avolio, 1990). “The transactional leader closely resembles the traditional definition of the manager” (Kouzes & Posner, 1995, p. 321).

Ten-item scales of transactional leadership were included with MLQ 5-R. High reliabilities (.85 and above) were routinely reported for descriptions of superiors by large samples of subordinates in military and industrial settings (Bass & Avolio, 1989). The 10 items of each scale were reduced to four in a short form (MLQ-5X) with some loss of reliabilities, as expected (Bass & Avolio, 1990).

This is a constructive transaction. The leader assigns a task or obtains agreement from the follower on what needs to be done and arranges for psychological or material rewards of followers in exchange for satisfactorily carrying out the assignment (Bass, 1998). For 207 British managers, Gill (1997) found that the managers who were directive practiced more contingent rewarding (r = .24). The psychological rewards may include positive feedback, praise, and approval. The material rewards may include a raise in salary, an award, or citation for merit.

Originally conceived as a transactional reinforcement, contingent reward correlates more with transformational than with transactional leadership. Explanations were found by Silins (1994) and by Goodwin, Wofford, and Whittington (2001). Contingent reward has two aspects. Silins found that contingent rewarding with external material rewards such as a raise in pay was transactional; contingent rewarding involving internal psychological processes such as praise was transformational. For Goodwin et al., the transactional factor was explicit reward, such as a commendation for good performance; the transformational factor was implicit, such as expressing admiration of the follower for good performance. Goodwin, Wofford, and Whittington (2001) completed a factor analysis of 154 employees describing their supervisors with the MLQ and a confirmation with MLQ data from an additional 209 employees describing their supervisors. Two CR factors were found and confirmed: explicit contingent rewarding and implicit psychological contracting. Consistent with these findings, higher-order factors unearthed in large sample factor analyses by Avolio & Bass (1999), Antonakis (2001), and others also showed that contingent reward could be both transformational and transactional. CR was transformational when the rewards were psychological, like supervisory recognition and praise for a follower’s good work. CR was transactional when the rewards were material, like increased pay.

This is a corrective transaction. If active, the leader monitors the deviances, mistakes, and errors in the performance of the followers and takes corrective action accordingly. If passive, the leader takes no corrective action before a problem comes to his or her attention that indicates unsatisfactory follower performance (Bass, 1998). The corrective action may be negative feedback, reproof, disapproval, or disciplinary action. Denston and Gray (1998) completed both qualitative and quantitative studies of MBE showing that MBE behavior fell into three categories: autocratic (directive), maintaining the status quo, and overregulation. As noted above, Gill also found that the more directive the leaders, the more they practiced MBE. Generally, MBE is lower in reliability than the other MLQ factors.

Transformational and transactional factors were conceived by Avolio and Bass (1991) as continua in leadership activity and effectiveness. Added was laissez-faire or nonleadership to the bottom of the continua in activity and effectiveness. By definition, transformational leadership was more active than transactional leadership, which was more active than laissez-faire leadership. Empirically, transformational leadership was more effective than transactional leadership, which was more effective than nonleadership. Avolio and Bass (1999) used 14 samples involving 3,786 MLQ survey participants describing their leaders to test nine factorial structures to determine the best fitting models. The best fitting models contained six lower-order factors: charisma (CH 1 IN), intellectual stimulation (IS), individualized consideration (IC), contingent reward (CR), active management by exception (MBEA), and passive avoidance (PA). Three higher-order factors emerged: transformational leadership and contingent reward, developmental exchange (IC 1 CR), and corrective avoidance (PA 1 MBEA). Antonakis (2001) and Antonakis and House (2002) found that the model of the full range of leadership remained valid, although they could point to a variety of moderators that affected results. These included the sex of leaders and followers, the risk and stability of conditions, and the leaders’ hierarchical level.

The pattern of factors that Bass (1985c) extracted provided a portrait of the transformational leader that Zaleznik (1977) had independently drawn from clinical evidence. Zaleznik’s leaders attracted strong feelings of identity and intense feelings about the leader (charisma). They sent clear messages of purpose and mission (inspi-rational leadership), generated excitement at work, and heightened expectations through images and meanings (inspirational leadership). They cultivated intensive one-on-one relationships and empathy for individuals (individualized consideration) and were more interested in ideas than in processes (intellectual stimulation). Tichy and Devanna (1986) concluded from interviews with 12 executives that transformational leadership is broader than charisma. They reported that transformational leaders were intuitive, cautious to avoid unrealistic expectations, empowering, and envisioning with clarity. Bennis and Nanus (1985, 1988) interviewed 90 public and private CEOs who said they made special efforts to inspire followers to greater productivity. Their followers said the executives raised their consciousness and provided a radiant but realistic vision of the future.

Marion and Uhl-Bien (2001) introduced complexity leadership, that enlarges transformational leadership to include catalyzing organizations from the bottom up through fostering the microdynamics of interaction among ensembles, coordinates the behavior among the ensembles. It allows for random effects and futures dependent on networks, structure, and relationships. It is based on complexity theory, borrowed by the social sciences from the physical sciences (Marion, 1999). Anderson (2000) suggested five leadership skills of increasing complexity needed by leaders to be transformational: (1) personal mastery to provide for clarity of beliefs and purpose of life; (2) interpersonal communications to build interpersonal relationships; (3) counseling on how to manage problems; (4) consulting about team and organizational development; and (5) versatility in styles, roles, and skills.

Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Moorman, et al. (1990) validated six transformational factors for the Transformational Leadership Inventory (TLI): (1) articulating a vision, (2) providing an appropriate model, (3) fostering the acceptance of group goals, (4) high performance expectations, (5) providing individualized support, and (6) individualized consideration. Podsakoff, MacKenzie, and Bommer (1996) showed that transformational leadership was generally independent of most contextual substi-tutes for leadership. Alimo-Metcalfe and Alban-Metcalfe (2000) used Kelly’s Repertory Grid Technique to elicit constructs from 48 female and 44 male middle, senior, and top managers about the similarities and differences of managers with whom they had worked in the British Health Service or local government. To form constructs, the managers were asked to chose the most and least alike leaders who had “had a powerful effect on their motivation, self-confidence, self-efficacy and performance.” The 1,464 responses were factor analyzed to yield reliable factors that generally appeared close to the transformational components of leadership described above: (1) inspirational networker and promoter; (2) encourages critical and strategic thinking; (3) empowers, develops potential; (4) genuine concern for others; (5) accessible, approachable. Other factors described the personality of the transformational leader: (6) decisiveness determination and self-confidence and (7) integrity (trustworthiness, honesty, and openness). Two transactional factors surfaced, one concerned with (8) political sensitivity and skills (in local government) and (9) clarifying boundaries. This last factor also included involving others in decisions. The nine factors were formed into the Transformational Leadership Questionnaire (TLQ).

Kouzes and Posner (1987) extracted a profile of transformational leadership from interviews asking leaders to describe their personal best leadership experience. Subsequently, they used the interview information to develop the Leadership Practices Inventory (LPI) for followers to complete. They noted that transformational leaders (1) challenge the process, constantly searching for new opportunities, ready to experiment and take risks, and remaining open to new ideas; (2) inspire a shared vision, articulating direction, ideals, and the special nature of the organization; (3) enable others to act by promoting collaboration and cooperative goals and establishing trust and empowerment; (4) model the way by behavior that is consistent with the vision and instills values supporting the vision; and (5) encourage the heart with high expectations, supporting persistence, rewarding others for success, and celebrating achievements. Carless (1999) administered the LPI and MLQ to 777 subordinates of 695 branch managers in an international bank in Australia. The LPI scales and the MLQ transformational scales were highly correlated.

Yukl (1987) initiated the Managerial Practices Survey (MPS) (Yukl, Wall, & Lepsinger, 1990) by first organizing a taxonomy of leadership and management practices based on factor analyses, expert groups, and prior theory. In the MPS scales that resulted, transformational leadership could be seen conceptually in motivating and inspiring, intellectually stimulating, problem solving, coaching, and supporting and mentoring. Transactional leadership could be seen in recognition, rewards, informing, clarifying roles, and monitoring operations. Tracy and Hinken (1998) found correlations ranging from .67 to .82 between the MLQ components and four selected MPS scales: clarifying roles, inspiring, supporting and team building. House (1997a) substituted value-based for charisma scales. Included were articulation of a vision, communication of high performance expectation, displaying self-confidence, role modeling, showing confidence in and challenging followers, integrity, and intellectual stimulation. Behling and McFillen (1996) developed scales for rating leaders on displaying empathy, dramatizing the mission, and projecting self-assurance to enhance image, to ensure competency and to provide opportunities to experience success. Jackson, Duehr, and Bono (2005) reported on the utility of using a questionnaire to measure empowerment along with a questionnaire to measure transformational leadership to predict performance, job satisfaction, and commitment. Jaussi and Dionne (2004) showed that an assessment of a leader’s unconventional behavior (e.g., standing on furniture or hanging ideas on clotheslines) added in regression analysis beyond transformational leadership to the prediction of followers’ satisfaction and perceived leader’s effectiveness.

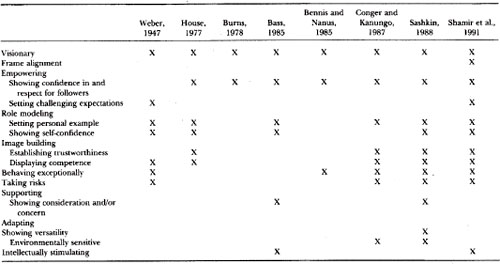

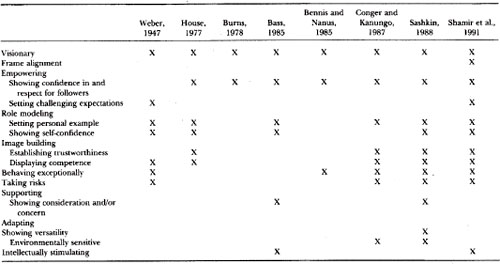

According to House and Aditya (1997), the theories of NLP include various theories of charismatic leadership (House, 1977; Conger & Kanungo, 1987; Shamir, House, & Arthur, 1993), theories of transformational leadership (Burns, 1978; Bass, 1985a), and visionary theories (Bennis & Nanus, 1985; Sashkin, 1988; Nanus, 1992). House, and Shamir (1993) provided a chart of the behaviors to be found in these theories cited by their authors (Table 22.1)

As currently defined by theorists and empiricists such as House (1999) and House and Shamir (1993), no distinction is made between charismatic and transformational leadership. They prefer to merge the two concepts as charismatic/transformational leadership. They see the same common motivational elements in charisma and transformational leadership (excluding individualized consideration). They connect the merged concept to followers’ self-concepts, internalized values, and cherished identities. The concept correlates with increasing collective efficacy and high expectations. Goals and values are linked to a sense of mission and to an ideal vision of a better future. But Bass (1998) argues that although the same leaders tend to be inspirational, intellectually stimulating, and individually considerate as charismatics, it is useful to keep the concepts separate, for they involve different behaviors and development. Although inspirational motivation and charismatic leadership are highly correlated and charismatic leaders are inspirational, inspirational leaders may not necessarily be charismatic: General Omar Bradley is an example. Napoleon and Alexander the Great were charismatic, inspirational, and intellectually stimulating but not particularly individually considerate as they grew in power and success. Horatio Nelson, the British admiral, was a transformational leader in the truest sense. He was charismatic and idealized by the En glish, he inspired his seamen and officers, and he revolutionized war at sea. He was also individually considerate and tried to meet the needs of his officers and seamen (Adair, 1989).

More rather than less differentiation is needed between charisma and transformational leadership, according to Hunt and Conger (1999). Conger (1999) and Yukl (1999) further discussed the need to maintain the distinction. Beyer (1999) asked how a charismatic leader transformed an organization.

LMX focuses on the rated quality of the dyadic relationship between superior and subordinate (Graen & Scan-dura, 1986). Since it can be a motivating exchange between two parties, it was assumed to be transactional (1989). Nevertheless, Graen and Uhl-Bien (1991) examined how quality LMX develops over time. LMX is a transactional exchange early in the process and later may correlate positively with transformational leadership. Tejeda and Scandura (1994) found a positive common correlation between supervisors’ transformational leadership and the quality of LMX between supervisors and subordinates in a health care organization. Furthermore, Dansereau (1995) argued that the quality of LMX depended on the leader supporting subordinates’ self-worth and showing confidence in the subordinate’s integrity, motivation, and ability, as well as being concerned for subordinates’ needs. Greenleaf’s (1977) servant leadership and Block’s (1993) leader as steward come to mind.

Smith, Montagno, and Kuzmenko (2004) compared transformational leadership with servant leadership. While transformational leaders share and align their followers’ interests, servant leaders put the interests of their followers before their own. Both emphasize personal development and empowerment of the followers. Both facilitate the achievement of followers.

Transformational leadership may be more relevant in a dynamic, changing environment; servant leadership may be more applicable in a stable environment.

Table 22.1 Behaviors Specified in Charismatic, Transformational, and Visionary Theories of Leadership

SOURCE: Adapted from “Toward the integration of transformational, charismatic, and visionary theories,” by R. J. House and B. Shamir, in Leadership theory and research: Perspectives and directions (p. 85), by M. M. Chemers and R. Ayman, 1993. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Copyright 1993 by Academic Press. Reprinted by permission of Academic Press, Inc.

Leadership was an important aspect of W. Edwards Deming’s 14 points for Total Quality Management. Sosik and Dionne (1994) selected five of Deming’s points for improving quality—change agency, teamwork, trust building, short-term goal eradication, and continuous improvement—and their likely linkage to the Full Range of Leadership. They proposed that in line with Deming, transformational leaders are agents of change, encourage teamwork, promote continuous improvement, build trust, and eradicate short-term goals.

Transformational leaders can be directive or participative. Charismatic leaders may direct their dependents out of crises; inspirational leaders direct their followers with slogans like “Never again.” Intellectually stimulating leaders direct their followers how to think through problems. Individually considerate leaders decide that only some followers need help. Critics see transformational leaders as elitist and autocratic. Nonetheless, charismatic leaders can be participative, for instance, by sharing in the building of visions. Inspirational leaders may listen to their followers before asking for a consensus about simplifying their ideas. Intellectually stimulating leaders may help followers to reexamine their assumptions. Individually considerate leaders may encourage followers to give one another support when they need it (Bass, 1998). After spending 27 years imprisoned by the white South African government, Nelson Mandela was directive and transformational when he declared, “Forget the past,” and showed his strong support for reconciliation. Gill (1995) reported a correlation of .29 between inspirational and participative leadership.

In the same way, the transactional leader can be directive or participative. The directive leader, practicing contingent reward, may decide to reward followers for their good performance. The directive leader can practice management by exception by taking disciplinary action for an observed violation of the rules by followers. Gill (1995) found correlations with directive leadership of .25 with contingent reward and .20 with management by exception. The participative leader may practice contingent reward by asking followers what needs to be done to achieve common goals. The participative leader can practice management by exception by asking how observed mistakes could be corrected. Nelson Mandela was participative and transactional when he campaigned for his successor as president and promised voters better housing. Gill (1995) reported a correlation of .35 between participative leadership and contingent reward but –.18 with management by exception.

Individualized consideration, as measured by the MLQ, is empirically correlated .69 with consideration of the Leader Behavior Description Questionnaire, yet they are somewhat distinct in concept (Seltzer & Bass, 1990). Consideration involves the leader’s friendliness, approachability, and participative decision making. Individualized consideration involves the leader’s concerns for each follower as an individual and with the follower’s development. It includes knowing the individual follower’s needs, raising followers to higher levels of maturity, delegating opportunities for follower self-actualization, and helping followers to attain higher moral standards. Individually considerate leadership is closely associated with quality orientation and good behavioral relations with individual subordinates, less so with relations with all the subordinates as a group. Leaders high on both scores may be either directive or participative (Bass & Avolio, 1993a).

Lipman-Blumen (1996) conceived of connective leadership as a contrast to instrumental leadership. Connective leaders intuitively focus on the interconnections among people, processes, and institutions. They make use of ethical social and political strategies to join their vision with the dreams of others. They strive to overcome mutual problems. They create a sense of community in which diverse groups can be valued members and enjoy a sense of belonging. They bring together others to encourage the assumption of responsibilities by active participants. They nurture potential leaders and successors. They build democratic institutions instead of creating dynasties and oligarchies. They dedicate themselves to goals beyond their own and demand sacrifices from others only after they have made sacrifices themselves. Connective leaders can also be instrumental. They will try to use others as well as themselves as instruments to achieve their common goals. Readers will recognize similar elements in connective leadership and transformational, charismatic, and servant leadership. Examples of connective leaders are leaders of voluntary organizations who attract dedicated workers by providing opportunities for ennobling action. They combine collaboration, nurturance, and altruism with the use of power and instrumental action. They assemble temporary creative teams of professionals for each new organizational project. They rally multiple short-term political coalitions to address diverse problems. They are dedicated activists, sacrificing careers, well-being, or even their lives for their community (Lipman-Blumen, 1996). Akin to constructive leadership, Parry (2002) validated a scale, Social Processes of Leadership (SPL). SPL was about influence, processes, relationships, interactions, and position in organized society. Parry found the scale highly correlated with various measures of transformational leadership.

A Hierarchy of Leader Effectiveness. Ordinarily, a hierarchy of effectiveness was found. Transformational leadership was more effective than contingent reward; contingent reward was more effective than active management by exception; and active management by exception might be positive or negative in effect on subordinates’ performance but was more effective than passive management by exception. Laissez-faire leadership was correlated moderately to highly negatively in effectiveness. Similar results were found for managers, project leaders, and staff professionals in a wide variety of firms and agencies (Bass, 1998) and in many developed and developing countries on five continents (Bass, 1997).

Vision arose as a leadership concept in the 1980s as a response to the need for firms to adapt rapidly to advancing technology and domestic and global competition (Conger, 2000). The concept of vision spread rapidly to nonprofit agencies and had always been of consequence to politicians and statesmen. Sashkin (1986, 1988) detailed and assessed the visionary leader. Vision is a notable correlate of the transformational process (Brown, 1993) and the transformational components of charismatic, inspirational, and intellectually stimulating leadership. As noted in Table 22.1, envisioning is included in most theories of charismatic and transformational leadership. The vision of the charismatic leader has both a stimulating and unifying effect on the follower (Berlew, 1992). Visionary leaders have a sense of identity, direction, and strategy for implementation (Nygren & Ukeritis, 1993). The vision is often a collaborative effort of a leader and colleagues and ties together a variety of issues and problems. To maintain their emotional appeal, it is better for a vision to be presented visually rather than only be posted or in writing (Hughes et al. 1993).

Purposes. Visions are goals that are forward-looking and meaningful to followers. They involve accurately interpreting trends or articulating future-oriented organizational goals. They provide a road map to the future with emotional appeal to followers. They help followers know how they fit into the organization (Bryman, 1992). They evolve in one or more of four ways from: (1) a leader with foresight who is sensitive to emerging opportunities; (2) networks of insightful organizational members; (3) the accidental stumbling onto opportunities and recognizing them; and (4) a process of trial and error with many experiences. They may be value and mission statements. According to Sashkin (1988), the cognitive skills required for envisioning are: expressing and sharing the vision with managers and employees in order to detail, revise, and review policies and programs, and to monitor their effects. Most people can envisage near futures up to one year, but few can think 10 to 20 years ahead, as might be required in a vision of the head of a large firm, political movement, or military organization.

A vision serves as a guide for interim strategies, decisions, and behavior. “Vision provides the direction and sustenance for change … and help us navigate through crises” (M. Hunt, 1999, p. 12). It is an important function in the public as well as private sectors (Berger, 1997). It is fundamental to effective executive leadership. Without the ability to define a desired future state, the executive would be “rudderless in a sea of conflicting demands, contradictory data, and environmental uncertainty” (Sashkin, 1986, p. 2). A vision integrates what is possible and what can be realized. It provides goals for others to pursue and drives and guides an organization’s development (Srivastva, 1983). Vision is a mental model of a future state of the organization (Nanus, 1992), an ideal image of the future (Kouzes & Posner, 1995). It connects beliefs about what can be done in the future (Thoms & Greenberger, 1995). Mikhail Gorbachev, in the 1980s, envisioned a unified Europe stretching to the Urals. By 2002, a step in this direction had been taken by Russia in accepting a seat as a limited partner in NATO.

Bennis (1982) called attention to the importance of vision to leaders. It was a major contributor to the success of 90 executives interviewed by Bennis and Nanus (1985). Likewise, Martin (1996) found that visionary leadership contributed to followers’ supportive attitudes. Envisioning is particularly important when the organization is facing illstructured problems (Mitroff, 1978). Conger (1999) viewed what distinguished charismatic leaders at higher organizational levels from others as the strategic decisions they formulated and articulated. The more the vision was out of the ordinary, the more it became challenging and a force for change (Conger, 1999). But for Harari (1997), “Vision must be pragmatically bifocal,” i.e., expected to encompass both current and future best opportunities. And Bruce (1986, p. 20) noted, “In the minds of CEOs … the vision is never clear, only a foggy haze and a multitude of conflicting signals. We see the future darkly, while ignorant armies of experts shout across a smoky field at one another.”

Example: J. Robert Oppenheimer. The primary source of the attractiveness of a vision to followers is their perception of the qualities of the leadership (Conger, 2000). This was illustrated by the case of J. Robert Oppenheimer, who in 1943 was appointed director of the newly founded Los Alamos National Laboratory to develop the atom bomb. I. I. Rabi (1969) said that based on his experience and personality, it was difficult to imagine a less likely choice. Oppenheimer had no administrative experience other than building the theoretical physics department at Berkeley. He was unknown to the government leaders who initiated and championed the project. He was seen as arrogant and nasty and at times made others feel foolish and inferior. It was expected that the director would be an expert in experimental, not theoretical, physics. Nonetheless, Oppenheimer succeeded brilliantly, first because he had a clear vision of the mission of the laboratory and was able to communicate that vision to organization members at every level, and second, because he was technically brilliant and outstanding in his intellectual stimulation, which helped colleagues think through problems. According to such scientists as Hans Bethe, Joseph Hirschfelder, Emilio Segre, and Edward Teller, he was “a genius in finding other people’s mistakes,” was a remarkably fast thinker, had an “iron memory,” and understood everything that was done in the lab, whether it was chemistry, physics, or machining, and then could coordinate the activities. He supported the vision by creating a laboratory environment of commitment and involvement of several thousand members, making each of them feel that he could contribute to the project. He overcame demands from higher authority for secrecy between laboratory divisions by organizing in terdivisional meetings and sharing of problems and progress. Trust in him was high because of his integrity (Ringer, 2002).

Vision Statements. An organization’s mission statement describes the activities to be performed for its clients, constituents, or customers (Yukl, 1998). It is not the same as vision. The core of a vision for the organization is its mission, but it adds meaning and purpose for the activities, arouses emotions, and is inspirational and intellectually stimulating. The vision should present an optimistic view of the future. It should express complex ideas in simple words and be a clear and credible statement of the future (Bass & Avolio, 1990). The vision should convey an image of what can be achieved, why it is worthwhile, and how it can be done (Yukl, 1998, p. 443). In a workshop for various sectors of a community, Berson, Shamir, Avolio, et al. (2001) sorted the vision statements of 141 participating leaders into 12 categories. They rated the “inspirational strength” of each vision and obtained four orthogonal factors. The first factor, optimism and confidence of the vision, accounted for 53.7% of the variance among the 12 categories. The factors were correlated with the MLQ assessments obtained prior to the workshop from the participants’ subordinates back at work. The factor of optimism and confidence correlated significantly .28, with charisma; .20 with inspirational motivation; .21 with intellectual stimulation; .15 with individualized consideration; and .15 with contingent reward. Specificity and direction of the vision correlated .15 with intellectual stimulation. McClelland and Winter’s motive imagery provided reliable and relevant measures of visionary statements. The effects of the statements were related to the expectations of government agency managers and managers in entrepreneural businesses. Their individual and unit performance in the government agencies were significantly affected by affiliative motive imagery. Power motive imagery in the vision statements correlated significantly with venture business growth in sales and profits in entrepreneurial firms (Kirkpatrick, Wofford, & Baum, 2002). Different factors emerged when a total of 672 vision statements were factored for 194 Singaporean respondents into (1) expertise, (2) strategic thinking, and (3) unconventionality (Khatri, Ng, & Lee, 2001).

The organizational culture plays a significant role. Visionary leaders turn their cultural ideals into organizational realities. In the process, they promote a philosophy that will be enacted by the vision’s policies and programs (Sashkin, 1988). Followers react positively when the vision reflects their values and provides information to direct their future behavior. The vision serves as a metagoal for the leader to pursue (Thoms & Govekar, 1997).

Vision Requirements. A new vision guides the leader in maintaining or changing the organization’s culture to redirect it into different missions (Bryman, 1992). For this, the vision needs to be properly communicated.

This can be achieved through leaders themselves acting as personifications of their visions and by proper attention to the rhetorical strategies by which the vision is communicated. … Equally, the leaders need to establish an organizational framework which will facilitate the accomplishment of the vision. … Leaders must constantly reiterate the vision and its desirability. (Bryman, 1992, pp. 137, 175)

The propagation of a vision is an important requirement of the CEO and top management. The CEO needs to align the TMT around the vision to effectively transmit it to the organization. The CEO needs to be the chief sense maker and sense giver. Although there may be negotiation, reformulation, and realignment, as the vision moves through the organization, the CEO remains responsible for its maintenance (Williams & Zukin, 1997).

Bennis and Nanus (1985) concluded, from in-depth interviews with 90 top directors and executives, that envisioning requires translating intentions into realities by communicating that vision to others to gain their support. Envisioning is the basis for empowering others, for providing them with the social architecture that will move them toward the envisioned state. It involves paying close attention to those with whom one is communicating, zooming in on the key issues with clarity and a sense of priorities. Risks are accepted, but only after a careful analysis of success or failure. Judge and Bono (2002) confirmed in surveys of 115 supervisors rated by 319 direct reports that transformational leadership was associated with vision content of higher-than-average quality.

Measurement and Correlates. Envisioning focuses more on success than on failure and more on action than on procrastination (Brown, 1993). Sashkin (1986, 1988) detailed the requirements to assess the visionary leader. The Leader Behavior Questionnaire (LBQ), developed by Sashkin and Fulmer (1985), a self-report of visionary leadership, included scales of focused attention, long-term goals, clarity of expression, caring, propensity to take risks, and empowerment. Stoner-Zemel (1988) found that visionary leadership, as measured by the LBQ, correlated with employees’ perceptions of the quality of their work lives. Ray (1989) showed that LBQ-assessed visionary leadership was related to a factory culture of organizational excellence. And Major (1988) obtained LBQ assessments in 60 high schools that linked the visionary leadership behavior of their principals with whether the schools performed high or low on various objective criteria.

Visionary leaders have a sense of identity, direction, and strategy for implementation (Nygren & Ukeritis, 1993). A 12-item Vision Ability Scale was validated by Thoms and Blasko (1999). For samples of a total of 891 college leaders attending the same national program in various locations, the scale correlated significantly .37, with self-rated MLQ inspirational motivation and .42 with the combined MLQ transformational leadership scores. Likewise, vision ability correlated .38 with LPI inspiring a shared vision. Significant positive correlations were also found with measures of optimism, positive outlook, and future time perspective. Baum, Locke, and Kirkpatrck (1998) used a longitudinal design to collect data from 183 CEO entrepreneurs and selected employees. Structural modeling confirmed that the attributes and contents of visions expressed verbally or in writing directly led to future venture growth.

Vision and the Transformation of Followers. The transformational leader concretizes a vision that the followers view as worthy of their effort, thereby raising their arousal and effort levels. However, people who seek to identify with the leader but who are distant from him or her may become only partially aroused and committed and may not take action to conform to the leader’s initiatives. Nevertheless, if they are free to act and are not constrained by other commitments or the lack of opportunity, they will actually become committed to leaders even at a distance. This was confirmed by Judge and Bono (2002) in surveys of 130 leaders’ visions, each described by their supervisor and three direct reports, that transformational leaders articulate and use visions more than do transactional leaders. Followers are more confident in the visions of transformational leaders and more committed to the visions. Downton (1973, p. 230) described this process as transformational rather than transactional, noting its greater likelihood of taking effect:

The opportunity for action is apt to be greater than strictly transactional relationships because the follower who identifies with a leader can transform his behavioral pattern without necessarily exchanging tangible goods with the leader … a new moral code … can be put immediately into practice, no matter how distant the leader and the opportunities for organizational activity.

Visions of Reformers, Revolutionaries, and Radicals. Reformers of political movements and governments such as Vicente Fox of Mexico, are able to convey to others a vision of what the society would be like, how it would look, if its ideals were supported. They espouse myths that sustain the political community and its professed ideal cultural patterns. Practices that depart from the ideals must be changed or eliminated in the desired future state. Revolutionary leaders such as Fidel Castro, on the other hand, envisage a future in which the sustaining myths and current cultural patterns have been rejected and society has been fundamentally reconstituted (Paige, 1977). The future the revolutionaries envisage in their rhetoric of the new regime is surprisingly devoid of details or mentions of justice, despite their focus on the injustices of the regime they intend to overthrow by force (Martin, Scully, & Levitt, 1988). Radicals of both the political Right and the political Left are likely to be ideologues, inflexible in their vision with everything black or white, never gray, extreme in their views, and intolerant of those who don’t share their vision (Mumford & Strange, 2002). Nevertheless, radical dissenters may contribute to transformations by disrupting fundamental assumptions and beliefs of the mainstream majority (Elmes & Smith, 1991).

Rational and Emotional Elements. Cameron and Ulrich (1986) pointed to the rational and emotional elements of envisioning. The rational element articulates a vision in which questions about purpose, problems, missing information, and available resources are answered. The emotional element articulates a vision of a holistic picture that is intuitive, imaginative, and insightful. It uses symbols and language that evoke meaning and commitment.

Strategic Planning. Other aspects of envisioning that are relevant in different ways at different levels of management in the complex organization include the formulation of strategies based on the contingencies of the threats and opportunities of the organization, its resources, and the interests of its constituencies. Leaders must be able to formulate and evaluate appropriate organizational responses and arrange for their implementation in operations and policies (Wortman, 1982). Leaders will be more effective in doing so if they are proficient in gathering and evaluating ideas, storing information, thinking logically, and learning from their mistakes (Srivastva, 1983). As they rise in their organizations, the abilities that are required of them will shift from dealing with concrete matters that have short-term consequences and for which all the parameters are known to more abstract issues with greater amounts of uncertainty and longer-term consequences (Jacobs & Jaques, 1987).

Vision and Consciousness Raising. Long-range visions need to be detailed. The leader must understand the key elements of the vision and consider the “spill-over” effects of their future development. Furthermore, the leader must be able to communicate his or her vision in ways that are compelling, make people committed to it, and help make it happen. As Bennis (1982, 1983) concluded after his interviews with 90 innovative organizational leaders, the leaders could communicate their vision to clarify it and induce the commitment of their multiple constituencies to maintaining the organization’s course. These leaders also revealed the self-determination and persistence of charismatic leaders, especially when the going got rough. Yet they emphasized their and their organizations’ adaptability to new conditions and to new problems. They concentrated on the purposes of their organizations and on “paradigms of action.” They made extensive use of metaphors, symbolism, ceremonials, and insignias as ways of concretizing and transmitting their visions of what could be. They pictured what was right, good, and important for their organization and thus contributed considerably to their organization’s culture of shared norms and values.

This arousal of consciousness and awareness in followers of what is right, good, and important, which new directions must be taken, and why, is the most important aspects of intellectual stimulation. The “mass line” leadership of Mao Zedong illustrated its application to social and political movements. The scattered and unsystematic ideas of the Chinese masses about marriage, land, and the written language were converted by the Communist Party leadership into a set of coherent, concentrated, and systematic ideas for reform, which were fed back to the masses until they embraced them as their own. Mao even seemed to practice this strategy in his one-on-one discussions with others (Barlow, 1981).

Intuitive Aspects. For Pondy (1983), envisioning begins with intuitive interpretations of events and data that give meaning to new images of the world that ultimately can be clarified into strategies for an organization. Symbols and phrases are invented to focus attention on the strategic questions that are needed to get others involved in the process. As Jim Renier, the CEO of Honeywell, suggested, although the vision that emerges may be that of the single-minded chief, it often evolves, in larger organizations in particular, out of the chief’s give-and-take with many others during repeated reviews of the possibilities of the desired future state. Renier (as quoted in Tichy & Devanna, 1986, p. 128) put it this way: “What you’ve got to do is constantly engage in iterating what you say [about the vision] and what they say is possible. And over a couple of years the different visions come together.”

With their ability to provide images of the future state, inspiring leaders provide direction. A commonly used metaphoric vision, a cliché favored by political leaders, is the path, road, or journey that must be taken that gives direction to the followers (Tucker, 1981). But metaphoric visions can boomerang into apocryphal anecdotes and reverse in meaning. For example, King Canute wanted to convey his limitations to his courtiers and used his lack of control over the ocean tides to illustrate his point. History converted the metaphor into an illustration of the king’s foolish pomposity in trying to command the sea not to roll up the beach.

Can Envisioning Be Developed? Mendell and Gerjuoy (1984) accepted the conventional wisdom that visionary leadership cannot be effectively taught. Unless the talent is there already, managers can only be prepared to anticipate possibilities. If this were true, then only recruiting and selection would ensure an adequate number of capable inspiring leaders with vision. But is it possible for managers to develop their ability to envision and to be more inspirational leaders, in general?

Exercises provide practice that engages trainees in envisioning their organization’s future. In such exercises, executives are asked to talk about how they expect to spend their day at some future date—say, three years hence—or what they expect their organization to look like. Or they may be asked to write a business article about their organization’s future. These comments are then evaluated with feedback. From these visions, leaders and managers can draw up mission statements and the specifications that must be met by such an organization (Tichy & Devanna, 1986).1

Caveat. Visions may be too abstract, too complex, unrealistic, unreachable, or impractical. They may also be too inspirational. Fulfilling a vision may become an end in itself or a distraction rather than paving the way to a valued goal (Langeleler, 1992). Meindl (1998) regarded visionary leadership as a “vague and mysterious concept.” He cited Collins and Porras (1994), who declared that the best companies have not relied on visionary leadership to sustain their competitive advantage. Additionally, Meindl (1998) argued that much of the salutary reporting about the positive effects of visionary leadership on organizational performance may be a myth, a product of the “Romance of Leadership” (Meindl, 1995). Successful organizations often attribute the outcome, incorrectly, to effective leadership. Meindl (1998) suggested that there may be more significant leadership tasks than envisioning: “We too often rely on overblown, highly romanticized images of great visionary leaders with special cognitions of the future” (p. 22). Nevertheless, at the same time, Meindl agreed that organizational members could be guided by a shared vision of a desired future state and that a leader with the necessary skills can shape and foster that vision.

What predisposes individual leaders to transformational or transactional leadership? The answers include individual differences in personality and differences in cognitive, social, and emotional competencies. Much evidence has accumulated that age, education, and experience are likely to correlate with the transformational leadership and transactional leadership of both the rated leaders and the followers. Additionally, leaders’ inventoried or tested traits and beliefs have been found to be correlated with their leadership ratings by their followers, peers, and/or superiors. In turn, these ratings have been found to be dependent on the traits of the followers.2

Personality predictors of transformational leadership have been found in a wide variety of sites, ranging from business and industry to community leaders’ programs. According to Popper and Mayseless (2002), the internal world of the transformational leader is characterized by the motivation to lead, self-efficacy, and the capacity to relate to others in a prosocial way. The transformational leader is optimistic and open to new experiences and others’ points of view. There is a disposition for social dominance, the capacity to serve as a role model, and a belief in the ability to influence others. As noted in Chapter 5, the Big 5 structure of personality with its five factors, each with several facets, has provided a widely accepted way to structure the study of personality as a predictor of performance. For example, Judge and Bono (2001) collected 14 samples of community leaders’ Big 5 NEOAC scores and their facets using the Costa and McCrae (1992) 240-item NEO Personality Inventory. Also, the 261 leaders were each MLQ-rated by one or two subordinates. The simple correlations of charisma, inspirational leadership, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration correlated with extraversion, openness, and agreeableness, respectively, as follows: extraversion, .22, .24, .14, and .23; openness, .18, .22, .10, and .21; and agreeableness, .28, .21, .24, and .23. Neuroticism and conscientiousness did not correlate with any of the transformational leadership factors. The MLQ transactional factor of contingent reward was negatively correlated –.20 with agreeableness. Passive management by exception correlated –.15 with agreeableness and –.18 with conscientiousness

Lim and Ployhart (2000) correlated the five NEOAC factors with the transformational leadership scores of the leaders of 39 Singaporean combat teams. The 202 team followers used the MLQ to rate their respective team leaders. Correlations of transformational leadership of the leaders with the five personality factors NEOAC, measured by the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP) were as follows: neuroticism, –.39; extraversion, .31, openness, –.08; agreeableness, –.29; and conscientiousness, –.09. Among the 79 studies classified in terms of the Big-Five factors in the meta-analysis by Judge, Bono, Iies, et al. (2000), reviewed in Chapter 5, 11 to 15 correlations between each of the NEOAC categories and judgments of transformational leadership were significant, as follows: neuroticism, –.21; extraversion, .25; openness, .30; agreeableness, .27; and conscientiousness, .19. In line with predictions, Bommer, Rubin, and Bald-win (2004) found that cynicism about change among 2,247 subordinates correlated –.29 with the transformational leadership of their focal leaders. This was offset by the correlation of .45 when transformational peer leadership of the 227 managers was present. Van Eron and Burke (1992) completed a survey of 128 senior executives and their 615 subordinates from a global firm and showed that the executives who described themselves as sensing rather than intuitive on the MBTI were more inspirational on the MLQ. Also, they were more judging than perceiving, according to their subordinates (r = .44; .30). They also were more likely to regard work as a strong sense of mission (r = .34; .23).

Military Studies. Clover (1988) compared on selected personality traits U.S. Air Force Academy com missioned officers who scored higher in charisma, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration on the MLQ with those who scored lower. Clover concluded that the transformational leaders were more likely to be more flexible, more compassionate, more pragmatic, and less tough. Ross and Offerman (1997) replicated the study with 40 Air Force Academy officers who completed the Adjective Checklist (ACL) (Gough & Heilbrun, 1983) and 4,400 cadets who completed a shortened form of the MLQ on the officer who commanded their squadron. Four cadets also completed the ACL on their squadron commander. The officers’ self-ratings on the ACL were combined with the four cadets’ ACL ratings to provide the personality trait measures. Transformational officers were more self-confident, more pragmatic, more nurturant, less critical, and less aggressive.

Avolio, Bass, Atwater, et al. (1994) examined the tested personality traits of junior-year cadet officers at Virginia Military Institute (VMI). MLQ ratings were provided by their subordinates. Hardiness (Kobasi, Maddi, & Puccelli, 1982) and physical fitness correlated with the cadet officers’ transformational leadership. Atwater and Yammarino (1993) correlated Cattell’s (1950) 16 PF Inventory personality assessments with MLQ ratings of 107 Annapolis midshipmen who served as summer squad leaders of 1,235 plebes. MLQ-rated transformational leadership, as appraised by the plebes’ superiors, correlated .24 with 16 PF self-discipline and .26 with 16 PF conformity. Additionally, Atwater and Yammarino (1989) found that the Annapolis midshipmen squad leaders appraised by their plebe subordinates as transformational described themselves as more likely to react emotionally and with feeling.

Community Leaders. Avolio and Bass (1994) correlated the Gordon (1963) Personal Profile (GPP), a forced-choice inventory, with MLQ ratings by subordinates of 118 leaders in their various public and private agencies and business firms in one middle-sized city in the United States. GPP ascendancy and sociability scores correlated .21 and .23 with charisma and inspirational motivation, respectively. Bass and Avolio also administered a sense of humor scale, which correlated positively but not significantly with all four components of transformational leadership. The MLQ component scores of the community leaders were also correlated with the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). Charisma and individualized consideration were predicted, respectively, by more MBTI feeling and less thinking (r = .25, .22). Inspirational motivation was predicted by intuition (r = .20) and not sensing (r = .19). The transactional factor of passive management by exception correlated with more sensing (r = .23) and less intuition (r = .28).

A meta-analysis by Lowe, Kroek, and Sivasubrahmanian (1996) compared public with private organizations and showed that leaders from public organizations were higher in mean factor scores than leaders from private ones in transformational leadership: charisma, –.61 versus –.33; individualized consideration, –.58 versus –.33; and intellectual stimulation, –.52 versus –.40. They also differed in transactional management by exception, –.41 versus –.16, and contingent reward, 1.85 versus 1.75. The meta-analysis also compared military with civilian organizations. Military leaders were higher than civilians in the factor mean scores for transformational leadership and for management by exception.

Cognitive, social, emotional, and other competencies have been found to be significant antecedents of transformational and transactional leadership, especially social and emotional competence (Bass, 2002). Older and more experienced Dutch managers, usually at higher organizational levels, saw a greater need for inspirational leadership, cognitive, and social competence. Younger Dutch respondents viewed their leaders as more transactional, especially if they were in sales or marketing (Tail-lieu, Schruijer, & van Dijck, undated).

Cognitive Competence. According to Wofford and Goodwin (1994), cognitive ability is what distinguishes transformational from transactional leaders. Subordinates’ MLQ ratings of the charisma and inspirational motivation of 782 managers correlated .13 and .16, respectively, with the Owens Biographical Questionnaire scale of intelligence (Southwick, 1998). Subordinate ratings of charisma, inspirational motivation, and intellectual stimulation correlated .33, .33, and .23 respectively, with management commitee evaluations of middle managers’ good judgment (Hater & Bass, 1988). Cattell’s (1950) 16 PF Inventory intelligence score correlated .20 with midshipmen’s transformational leadership. However, the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) failed as a significant predictor of transformational leadership among midshipmen (Atwater & Yammarino, 1993) and military cadets (Avolio, Bass, Lau, et al., 1994).

Social Competence. The use of humor was found by Avolio, Howell, and Sosik (1999) to correlate .56 with the transformational leadership behavior of 115 Canadian managers and executives and .45 with their practice of contingent reward.