Individuals, groups, and organizations confronted with threats to their well-being will experience stress. Rowney and Cahoon (1988) noted that the burnout scores among individuals who work in the same unit are more similar than those of individuals who work in different units doing similar kinds of work. In many instances, the available leadership makes the difference in the prevention or occurrence of stress and burnout. Leadership can be the source of increased stress, negative emotions, and negative outcomes. But leadership can provide for avoiding stress or coping with it. Thus Graham (1982) found that with professional employees of a county extension service, job stress was lower when the leaders of their district program were described as higher on the Leader Behavior Description Questionnaire (LBDQ)1 in both initiation of structure and consideration. Leadership can also be the source of positive emotions; when, threats are converted to opportunities, stress may yield positive outcomes (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2000).

Rodney Lowman advised that signs of stress in the work-place that need to be recognized by the leader include: (1) absenteeism, whether due to illness or other reasons; (2) workers who have become more irritable and hard to get along with; (3) more confusion is appearing and mistakes are more frequent on tasks that usually are performed well; (4) stress is felt by the leaders and felt and expressed by the workers (Perry, 1999).

Stress symptoms include increased emotional arousal, frustration, defensiveness, faulty decision making, and physiological symptoms like sweating, heavier breathing, and increased heartbeat. A state of anxiety is a perceptual manifestation of such objective conditions of stress (Spielberger, 1972). Well known is the extent to which stress is generated in subordinates by hostile, abusive superiors (Roberto, 2002). The hostile, abusive leader who uses power to bully, humiliate, intimidate, and threaten subordinates is a major source of stress (Aquino, 2000; Tepper, 2000). Deadlines are set that are impossible to meet. There are inordinate pressures to produce and constant unnecessary disruptions of work by the supervisor. The stress shows itself in subordinate dissatisfaction, negative emotional reactions, moods, and feelings, and psychosomatic and physical symptoms, particularly if quitting is not possible. Anxiety, anger, depression, negativity, and loss in self-esteem may be further consequences of the continuing stress.

Assessments. Among many assessments of stress and anxiety, the anxiety state was measured on the job by Schriesheim and Murphy (1976) with the 20-item State Anxiety subscale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger, Gorsuch, & Lushene, 1970). The Job Stress Survey (Spielberger, 1994) was applied by Spielberger and Reheiser (1994) to measure job stress in business, university, and military organizations. The Maslach Burn out Inventory (1986) assessed stress and burnout in MBAs, professionals, and employees.

Faulty Decision Making. Decision making under stress becomes faulty. Instead of careful analysis and calculation or the effective use of the intuition of the expert based on learning and experience, stressed decision makers fall back on nonproductive intuitive reactions that satisfy their immediate personal emotional needs rather than the objective requirements of the situation. As Simon (1987, p. 62) noted, “Lying, for example, is much more often the result of panic than of Machiavellian scheming.” When Sorokin (1943) examined reports of the reactions of groups and communities to the calamities of famine, war, and revolution, he found that a calamity tended to intensify emotional arousal, distort cognitive processes, focus attention on the dangers and away from other features of the environment, hasten disintegration of the self, and decrease the rationality of decision making. The erroneous decision that resulted in the shooting down by the U.S. Navy ship Vincennes in the Persian Gulf of an Iranian commercial jet liner was attributed to the stressed personnel misreading and misinterpreting their radar displays as a descending attacking aircraft instead of a plane taking off on a routine commercial trip between Iran and Saudi Arabia.

The ordinary healthy reaction of an individual, group, or organization to dissatisfaction with the current state of affairs is to examine fully what prevents the attainment of the more desired state, then to consider various alternative courses of action, and finally to take appropriate steps to achieve the goal. But if motivation is high, if obstacles are severe, or if remaining in the current state is threatening to one’s welfare or survival, malfunctions in the coping process occur. There may be no time to deliberate about choices among actions. There may be communication outages or severe information overloads. The mobilization of autonomic energy occurs with the felt emotional arousal and related symptoms of stress. Such arousal narrows perceptions and limits the ability to think creatively (Lazarus, 1966). Memory and cognitive functions become impaired (Weschler, 1955). Stress is an evolution-based reaction that prepares the individual for fight or flight in the face of danger and threat. When one is unable to cope with the threat, the autonomic symptoms appear. A year after the Katrina disaster of 2005, more than 100,000 residents who fled have been unable to rebuild because of the severity of the flooding or lack of personal resources. They have not returned to New Orleans. Those still in temporary shelters remain depressed.

Stress may generate positive emotional arousal. With personal control, prolonged distress may be reduced when those affected can focus on the good in the situation by reappraising it or finding humor in it; by viewing the situation as a problem to be solved; or by taking a time-out to concentrate on some positive emotional arousal or finding humor in it to provide relief from the stress (Moskowitz, Folkman, Colette, et al., 1996).

Frequency of Felt Stress among Managers. In response to 17 questions, such as how much in the last month they had felt nervous and stressed (0 5 never to 4 5 very often a problem), several hundred each of Japanese managers registered an overall mean of 1.59; Indian managers, a mean of 1.37; and American managers, a mean of 1.33. The average manager in the three countries experienced a stressful experience at least once a month (Ivancevich, Schweiger, & Ragan, 1986). The figures for U.S. managers were much lower in response to questions about their experiencing stress daily, somatic symptoms, anxiety, and social dysfunctioning and much higher for their reports of job-induced stress (“I am not sure exactly what is expected of me”) and the discharge of job tension off the job (Matteson & Ivancevich, 1982). The use of tobacco, alcohol, tranquilizers, sedatives, and other drugs is commonly an effort by managers and professionals to cope with job stress, as are physical exercise, socializing with friends, and recreational activities (Latack, 1986). In an Indian study, workers were found to be subjected to significantly more stress (boredom, frustration, bereavement, and physical stress) than their supervisors and managers (Biswas, 1998).

Causes of Stress. Stress occurs to individuals, groups, and organizations when their situation is overly complex, ambiguous, unclear, and demanding in relation to the competence, resources, or structural adequacy available to deal with the demands. Compared to Europeans, U.S. workers work longer hours to maintain higher output than elsewhere. Higher productivity due to technological advances is accompanied by the insecurities of layoffs and unemployment. The same insecurities accompany the movement of factories and offices to regions with lower labor costs, less taxation, fewer environmental controls, cheaper energy, and government subsidies. In order to remain competitive, management pushes for faster and more efficient production. Currently the shibboleth is continuous improvement.

Continuous improvement means continuous change. Organizational change is stressful. In a Swedish survey, Arvonen (1995) found psychosomatic reactions of stress in employees under supervisors who were change-oriented if the employees lacked commitment. As Stuart (1996, p. 11) surmised, “having one’s department reorganized, one’s responsibilities outsourced, and several tiers of one’s peer managers taken out … would stress a manager in the same way as a natural or man-made catastrophe.” The threat of downsizing and actually being laid off is an important source of insecurity and its accompanying fears and anxieties. Additionally, the survivors of an organizational downsizing, although perhaps relieved for the moment, are also likely to reveal feelings of fear, anxiety, and distrust. Less well known are the effects of denial of their feelings of guilt and the depression that denial can cause (Noer, 1993). A sudden unexpected promotion might be stressful in a positive way. Roskies and Lewis-Guerin (1990) found that 1,291 Canadian managers who were insecure in their jobs reported poor health. Their health was worse depending on their level of insecurity. They mainly were anxious about the long-term threat to their jobs and the deterioration of their positions. According to Judge, Boudreau, and Bretz (1994), among 1,309 executives using a search firm for possible opportunities to change jobs, job stress correlated −.21 with life satisfaction, −.29 with job satisfaction, −.26 with family matters that caused conflicts at work, and −.44 with job conditions that caused conflicts in the family.

The need to make changes in themselves and their work is often a source of stress to managers as well as their employees. They may be stressed by feeling that they increasingly need to face unfamiliar products, services, and situations and that they will increasingly need more skills (Rago, 1973; Frew, 1977). The pressure for change correlated .46 with stress for 88 Tennessee state government supervisors (Rohricht & Rush, 1977).

The most commonly reported sources of stress in the working environment are lack of good relations and lack of support from supervision, according to a Job Stress Survey of 209 managers reported by O’Roark (1995). (Arvonen (1995) reported the same effect.) The results were the same for all personalities as assessed by the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). Conversely, Crawford (1995) noted that the socially supportive leader mediated the effects of stress. O’Roark also found that for executives in a regional medical center, the difficulties that generated the most stress for them were meeting deadlines, frequent interruptions, dealing with crises, and having to make on-the-spot decisions. Among 781 Swedish personnel, creative leaders were found by blue-collar workers to generate more stress (Arvonen, 1995).

This was consistent with Seltzer, Numerof, and Bass (1987), who observed that burnout among employees was higher when their leaders were more intellectually stimulating. The Swedish managers and white-collar workers felt more stressed if they described their immediate managers as bureaucrats. This fitted with Crawford’s (1995) opinion that stress among their followers was likely to be generated by transactional leaders.

Workplace violence, such as shooting incidents in the U.S. Postal Service, is an extreme case of the effects of stress resulting from the confluence of stressed-out employees, autocratic and punitive leadership, and a high degree of tension in the environment. Simple, repetitive tasks have often been replaced by complex job demands, yet employees remain under a high degree of control. The perpetrators felt a sense of injustice and had low self-esteem and paranoid tendencies. They came from unstable families, had few outlets for rage, called for help many times but did not receive any, and felt poorly treated by their supervisors. Most unfortunately, they were fascinated by guns and the military (DeAngelis, 1993). The symptoms of aggression begin early. Garcia and Shaw et al. (2000) observed aggression in two-year-old boys engaged in a clean-up task with mothers whose parenting style was rejecting, critical, hostile, and physically punitive.

A variety of different antecedent conditions may give rise to stress in groups. To some degree, the observed and appropriate leadership behavior will depend on the particular antecedents that were involved. Bass, Hurder, and Ellis (1954) identified four emotionally arousing stress experiences with different antecedents: (1) frustration is likely to be felt when highly prized positive goals are unattainable because of inability or difficulties in the path to the goals; (2) fear occurs when escape from noxious conditions is threatened by obstacles in the path; (3) anxiety is aroused when these paths, obstacles, and goals become unclear (fear and frustration turn to anxiety with increasing uncertainty); and (4) conflict arises when one faces incompatible choices of goals. Potentially high risks and costs compete with the anticipated benefits of a course of action.

After examining the physiological reactions and the cognitive and psychomotor performance of 200 college men under experimentally induced frustration, fear, anxiety, and conflict, Bass, Hurder, and Ellis (1954) concluded that performance under these various stress conditions would decrease or increase in contrast to a stress-free condition depending on which tasks and skills were involved, which type of stress was imposed, and the initial level of arousal of the participants. Differences among the men were also large.

Leader-subordinate dyadic analysis would seem particularly important in understanding leadership in threatening situations. What one subordinate may see as an invigorating challenge, another may perceive as a stress-laden threat. It is all in the eye of the beholder. As McCauley (1987, p. 1) put it, “A challenging, rewarding task for one person may be flooded with stress and anxiety for others. How one appraises self and situation makes all the difference.”

According to Bunker (1986), less stress in the same threatening conditions are felt by those who are generally optimistic, who believe that such conditions are matters of their own fate and not controlled by external forces, who can tolerate ambiguity and uncertainty, and who feel they can improve their own abilities. In agreement, Spector, Cooper, and Aguilar-Vafaie (in press) found that among both Iranian and U.S. managers, those with higher locus of control reported less strain from job pressures. Such confidence is enhanced with experience. The effects of stress and anxiety are reduced as experience is gained with the same threats (Benner, 1984). The effect of experience is similar to the effects of preparation, overlearning, and overtraining. Smith (1994) notes that managers and business leaders are most often thinking-judging (TJ) personality types on the Myers-Briggs Type Inventory (Myers & McCaully, 1985). TJs are likely to be more comfortable in a structured and organized environment. But those who are not TJs—artists who emphasize feeling-sensing, for instance—are more likely to be stressed by the manager’s role.

Stress can also vary from one individual to another as a consequence of deep-seated feelings of inadequacy that surface in aggression or overdependence when real or imagined threats occur. People differ from each other in this intrapsychic tension.2 Levinson (1980) conceived of stress as a consequence of such intrapsychic tension—the increased gap between one’s ego ideal (the partly conscious image of oneself at one’s future best) and one’s current self-image. Among both U.S. and Iranian managers, those who had a greater internal locus of control showed less feelings of strain due to the pressures of their roles, work-family conflict, constraints, and lack of support (Spector, Cooper, & Aguilar-Vafaie, in press).

To some extent, the loss of 5 of a party of 23 climbers on Mount Everest in 1996 could be attributed to the overconfidence of the leader, expectations of continuing good weather, lack of cooperation, failure to observe the rule to turn around before reaching the top if it was 1 or 2 p.m. to avoid being caught descending to camp in the dark. But a sudden storm came up, changing the situation.

Resilience. People differ in their ability to restore their equilibrium after an event or period of stressful adversity. They learn to grow out of their adversity (Bonanno, 2005). Many handicapped and disadvantaged children overcome their handicaps and disadvantages to become successful and effective adults. Eleanor Roosevelt, for example, was treated as an “ugly duckling” by her family. She overcame her shyness and thin voice to become a world-class leader.

The study of leadership under stressful conditions has often treated stress as a homogeneous situation. Yet the same stressful experience can stem from a variety of precipitating conditions, and the variety of possible reactions to it may depend on the different precipitating conditions. Thus, research on disasters has found systematic differences in community reactions to warnings of tornadoes and warnings of floods. Communities react much more quickly to threats of tornadoes than to threats of floods.

Other Situational Stressors. The pace of work can become a source of stress, particularly if the operators are inexperienced novices. Workplace relocations can be disruptive and stressful, as shown when supermarket personnel were transferred from one store to another (Moyle & Parkes, 1999). Downsizing is stressful not only to the employees who lose their jobs but also to the survivors. About half of the survivors after downsizing, according to Cascio (1995), reported feelings of anxiety and insecurity. The volatility and instability of family incomes have increased substantially since the 1970s. Instability was five times greater in the 1990s than the 1970s. Stability peaked in 1972. The spread between the rich and the poor increased. Lower-paid workforce income failed to keep up with inflation. Many families faced a new level of insecurity and stress as they became two-earner households to maintain the same standard of living as was once possible with just the single wage earner (Lind, 2004).

Frequent business and government travelers reveal emotional upset, physical strains, irritability, and impaired performance before, during, and after trips (De-Frank, Konopaske, & Ivancevich, 2000). Many face an overstimulating lifestyle. Before the trip there are the distractions of planning the trip, making suitable work and family arrangements, and preparing to visit different cultures and climates. Almost 75% of married people and 50% of travelers on business say it is difficult to be away from home for extended periods. Fifty percent say they worry about what is happening at home and in the office (Fisher, 1998). Particularly stressful are airline delays and cancellations, needing to visit numerous locations in one or two days in a single city with heavy traffic, a lack of opportunity for healthy exercise, sleep deprivation, and eating too much or too little while on the road.

Reactions to changing time zones and jet lag are often discomforting aspects during and after travel. On re-turning home, travelers have to make up for what they missed. On returning to their office, they are faced with an overloaded in-box, finding out what happened during absence, catching up with changes, and completing expense account reports (DeFrank, Konopaske, & Ivancevich, 2000).

Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, et al. (1964) showed that two distinct sources of stress could be identified in organizations: role conflict and role ambiguity. Each has different antecedents and consequences. Role conflict involves contradictory requirements, competing demands for one’s time, and inadequate resources. Role ambiguity involves lack of clarity about tasks and goals and uncertainty about the requirements of one’s job.3 Latack (1986, p. 380) noted how managers and professionals tried either to control role ambiguity, role conflict, and role overload or to escape from them. To control role ambiguity, they “try to see the situation as an opportunity to learn and develop new skills” (p. 380). To escape from role ambiguity, they “try to do their best to get out of the situation gracefully.” To control role conflict, they “work on changing policies which caused this situation.” To escape from role conflict, they “separate themselves as much as possible from the people who created this situation.” Deluga (1989) found that 106 to 109 employees in a metal-fabricating firm who experienced role conflict in the demands their jobs placed on them used upward influence tactics on their supervisors to alleviate the stress. Specifically, as the role conflict increased they first tried to influence their supervisors to change the conflicting demands on their jobs with friendliness, bargaining, reasoning, assertiveness, appeals to higher authority, and coalitions with other employees. When the attempted influence failed, they resorted a second time to assertiveness, friendliness, and coalition efforts.

Role Overload. To role conflict and ambiguity, Latack (1986) added role overload as a source of stress. To control role overload, managers and professionals “try to be very organized so they can keep on top of things.” To escape from role overload, they “set their own priorities based on what they like to do.” When the Job-Related Tension Index of Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, et al. (1964) was completed by 113 Canadian managers for R. E. Rogers (1977), four factors were extracted from the results. These factors were (1) too heavy a work load, (2) self-doubts, (3) sense of insufficient authority and influence upstairs, and (4) need to make unpopular decisions against their better judgment.

Shaw and Weekley (1985) also found actual qualitative overload to be stressful. Nonetheless, other investigators did not conclude that work overload was necessarily stressful to managers. S. Carlson (1951) found that it was normal for most Swedish executives to report being overloaded and having little time for family or friends.4 A business management survey of 179 company presidents and board chairmen obtained results indicating that the average executive worked approximately 63 hours per week but did not feel overworked, although more than 70% thought they did not have enough time for thinking and planning (Anonymous, 1968). But W. E. Moore (1970) observed that detailed chores involving problems in communication and operations interfered with the managers’ effective use of their time. Yet Jaques (1966) noted that hard work and long hours were not sufficient conditions for producing stress symptoms in executives. Rather, stress conditions are generated from within the manager as responses to impossible standards of achievement or tasks that are perceived as overly difficult.

The conclusions about work overload are seen in the extent to which some harried executives are aggressively involved in achieving more in less time. As discussed in Chapter 8, such executives habitually have a sense of urgency (Friedman & Rosenman, 1974). They are labeled Type A personalities; many are highly stressed, as is evidenced by their proneness to heart disease. Nevertheless, many other harried Type As are not under such stress. The difference is that those Type As who are subject to heart disease are also depressed, tense, and generally prone to illness. They are not generally healthy, talkative, self-confident, and in control of their situations (Friedman, Hall, & Harris, 1985).

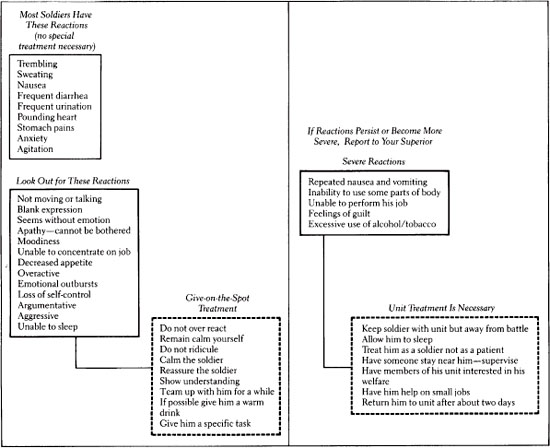

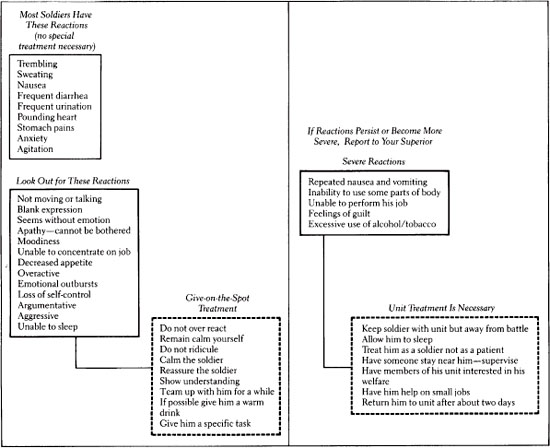

Combat Conditions. Military combat is illustrative of both the situational and personal elements that are of consequence to the generation of stress and the reactions to it. The actions and coping of soldiers in conditions of combat stress are responses to a situational and personal complex of antecedent and mediating variables. Whether soldiers and their leaders actively carry out their duties, become passive, or collapse will depend on the amount of surprise and uncertainty in the battle; the weather and terrain; and particularly whether the operations are mobile and offensive or static and defensive. Stress is likely to be higher in the enforced passivity of the static or defensive condition, which generates a feeling of helplessness (Gal & Lazarus, 1975). Again, individual differences in personality, family problems, and prior exposure to combat will be of importance. Active “fighters” are more intelligent and masculine and have more leadership potential (Egbert, Meeland, Cline, et al., 1957). Winners of medals are more persevering, decisive, and devoted to duty (Gal, 1983).

One’s role in combat makes a difference. The higher physiological responses of Israeli officers compared with those of enlisted men are coupled with fewer somatic complaints and breakdowns among the officers. Leaders are more emotionally aroused but appear to suffer much less decrement in their performance during combat than do enlisted men, although in general, as in the Israeli-Arab confrontations, the officers were much more at risk than were the enlisted personnel. Gal and Jones (1985) suggest that one’s perceived role as a leader provides a sense of mastery and control and causes one to concentrate on tasks that distract attention from the realistic dangers.

As already noted, stress occurs when the group’s drive is too high for the demands of the task. When members are blocked from obtaining a goal or from escaping from a noxious condition, their stress increases with their increasing motivation to obtain the goal or escape the situation. Tjosvold (1985b) found that although executives made effective decisions under moderate levels of motivation, when faced with a crisis, their performance deteriorated and quick solutions requiring the least effort were chosen instead of high-quality ones.

Since cohesiveness and commitment imply heightened motivation to attain goals, more stress should be seen in cohesive than in noncohesive groups. When J. R. P. French (1941) frustrated groups of cohesive team-mates and groups of strangers who were lower in cohesiveness, the more cohesive teams experienced greater fear and frustration. Similarly, Festinger (1949) reported that more complaints that were suggestive of stress appeared among more cohesive groups. Also, M. E. Wright (1943) found that more cohesive pairs of friends exhibited more aggression when frustrated than did pairs whose cohesiveness was lower.

Given a high degree of group drive, the group members’ sensed inability to obtain the group’s goals or to escape from danger increases the likelihood of stress. Groups that are unable to interact easily or that do not have the formal or informal structure that enables quick reactions are likely to experience stress (Bass, 1960). Panic ensues when members of a group lack superordi-nate goals—goals that transcend the self-interests of each participant. Mintz (1951) found that when members of an experimental group in a crisis sought uncoordinated individual reward (or the avoidance of individual punishment), panic was likely to ensue. If the group was organized and perceived a single goal for all, such panic did not materialize. Similarly, in an analysis of anxiety in aerial combat, D. G. Wright (1946) concluded that an aircrew could cope with stress when a common threat was perceived and when a common goal and action toward it were maintained under an apparent plan of action. Clearly, the leader who can transform a group of members with different self-interests into a group with goals that transcend their own self-interests will make it possible for the group to cope more effectively with potentially stressing circumstances.

An individual is stressed when he or she is highly motivated to escape threat or to obtain highly valued goals but is unable to respond adequately, unready to react, untrained, and inexperienced. Increased preparedness and overlearning are ways of helping the individual to cope with anticipated stressful situations. At the group or organizational level, the reliability and predictability of the group’s response become essential. Everyone needs to know what everyone else is likely to do. Roles must be clear and free of conflict and ambiguity. Structure, through an informal or formal organization, becomes important. Thus, Isenberg (1981) demonstrated, in an experiment with four-person groups who were making decisions under the stress of the pressure of time, that the structure of relations increased and leadership became more salient. Differences in how much time the members were able to speak increased. Again, Gladstein and Reilly (1985) found that when stress was induced in a business simulation by introducing threats and time pressure, decision making became centralized. A small number of members had much more influence than did others in the group than when time pressure and threatening events were absent.

When a group does not have the necessary structure to meet emergencies and threats, the initiation of such a structure by a strong leader is seen as needed and useful to the group. Path-goal formulations5 examine such requisite leadership behavior when the roles of workers are unclear. When subordinates have clear perceptions of their work roles, the leader’s initiation of structure is redundant. However, the leader’s initiation of structure should help highly motivated subordinates with less clear role perceptions to perform their jobs and thus increase their satisfaction and performance. Schriesheim and Murphy (1976) found that job stress, like the lack of structure, moderated the initiation of structure–job satisfaction relationship, as expected. In J. R. P. French’s (1941) previously cited investigation, eight organized groups (with elected leaders) and eight unorganized groups were studied. Frustration was produced by requiring the groups to work on unsolvable problems. Unorganized groups showed a greater tendency to split into opposing factions, whereas the previously organized group exhibited greater social freedom, cohesiveness, and motivation. The greater the differentiation of function that occurred with organization, the greater was the interdependence of members and unity of the group as a whole.

The need for structure at the macro level, as well as at the individual level, was seen by Sorokin (1943). In times of disaster, ideal human conduct depends on a well-integrated system of values. The values conform to the ethics of the larger society. There is little discrepancy between values and conduct. But individuals who engage in antisocial and delinquent behavior (murder, assault, robbery, looting, and the like) tend to be guided by self-centered, materialistic, disillusioned ideologies. They are not integrated into a larger organized effort. The wanton massacre of inmates of a penitentiary in New Mexico in early 1980 by berserk fellow prisoners was partly attributable to the lack of organization in the prisoners’ rebellion and the sudden complete availability of drugs (Hollie, 1980).

Gal and Jones (1985) noted that a strong informal structure within a military unit helped reduce the perceived stress of combat. Elite units, with strong bonds between comrades and leaders, were found to suffer less stress, as evidenced by much lower psychiatric casualty rates, despite greater exposure than ordinary units to the risks of high-intensity battle.

Janis and Mann (1977) looked at responses under stress that were induced by conflict in the face of an impending threat and the risks and costs of taking action to avoid stress. They argued that the completely rational approach to an authentic warning of impending danger would be a thorough examination of objectives, values, and alternative courses of action. Costs and risks would be weighed. A final choice would be based on a cost-benefit analysis. Included in the effective process would be development, careful implementation, and contingency planning. But such vigilance, thorough search, appraisal, and contigency planning are likely to be short-circuited as a consequence of emotional arousal and the socio-emotional phenomena generated by the impending threat. Various defective reactions to the warnings of danger are likely to occur. These reactions include adherence to the status quo, too-hasty change, defensive avoidance, and panic.

One inadequate reaction is the hasty decision that dealing with the threat involves more serious costs and risks than doing nothing. The threat is disbelieved and disregarded. People remain in their homes despite slowly rising floodwaters and warnings to evacuate. An inadequate analysis, in which appropriate information is ignored, sees the costs of evacuation as greater than the risks of remaining. This response is less likely in the case of sudden threats, such as tornado warnings. Analogously, the energy crises of 1973 and 1979 had built up for 20 years in the face of inertia to cope with them adequately. The threats to the environment of the depletion of the ozone layer, acid rain, and the greenhouse effect likewise failed in the 1980s to mobilize the necessary public support for a political effort to deal with the threats. But in 1941, full national commitment and mobilization to deal with the Japanese threat, signaled by the attack on Pearl Harbor, was instantaneous.

Staw, Sandelands, and Dutton (1981) pointed to the increased rigidity in organizations when they are threatened. Consistent with this, Gladstein and Reilly (1985) engaged 128 MBA students in a full six-day business simulation to show that threatening events and the pressure of time each systematically constrain decision-making processes by reducing the amount of information used by the groups before they reach their decisions.

If the costs and risks of taking action to deal with a perceived threat are thought to be low, a new course of action is adopted, often too hastily, without an adequate examination of the threat, risks, and long-term implications. People who experience a high degree of tension from an intense structural strain in the social or political fabric become susceptible to the influence of rebel leaders who promise to restructure the situation quickly, particularly if the established leadership fails to do so (Downtown, 1973). A field investigation by Torrance and staff (1955) reported that air crews who were “forced down” and faced simulated difficulties of surviving in “enemy” territory tended to turn to immediate but ineffective solutions to their problems and to concede more to comfort as their stress level increased. For example, as the hardships increased, they chose to travel on roads in “enemy” territory instead of traveling over routes where they were less likely to be seen.

Rapid, decisive leadership is valued highly under conditions of perceived threat to the group. Executives and politicians incrementally “put out one fire after another,” drifting into a new policy to cope with each successive threat, rather than formulating a new policy based on a thorough search, appraisal, and plan (Lindbloom, 1959).

When the risks of change are seen to be high and the current course of action is maintained because of fatalism and a sense that no better course can be found, the various Freudian mechanisms, such as rationalization, displacement, fantasy, and denial, provide psychological defenses to avoid the threat, rather than to cope rationally with the danger. Particularly common to managers in large organizations, according to Janis (1972), are procrastination, shifting responsibility (buck passing), and bolstering—providing social support for quickly seizing on the least objectionable choice. These are defective ways of dealing with a threat.

If the threat contains time pressures and deadlines and if individual motivation to escape the threat is high, hypervigilance (panic) may set in. Defective search is illustrated by the failure to take the time to choose a satisfactory escape route from a fire. Instead, a person in panic, in a highly suggestible state, simply starts imitating what everybody else is doing, failing to anticipate the consequences of blocking common exits. According to a review by A. L. Strauss (1944), the major factors in panic are: (1) conditions that weaken individuals physically; (2) reduced mental ability and lessened capacity to act rationally; (3) heightened emotionality, tension, and imagination, which facilitate impulsive action; (4) heightened suggestibility and contagion, which may precipitate flight; and (5) loss of contact with previous leaders and a predisposition to follow those at hand.

When disaster strikes, panic is not most people’s first reaction. Acute fear and attempts to flee the disaster occur only when immediate danger is perceived and individuals see their escape routes blocked (Quarantelli, 1954). Exascerbating the panic reaction is a strong sense of isolation. For some, the unadaptive reaction is to freeze in place or to become blinded to the events occurring around them. (When the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, many people ceased to feel [Lifton, 1967].) Nevertheless, despite their sense of panic, some people do begin trying to cope with the disaster if they receive no formal directions from authorities.

Informal leadership and temporary groups may emerge if the formal authorities and emergency services cannot deal with the crisis (Mileti, Drabek, & Haas, 1975). The direct removal of the threats and obstacles that are the source of stress may be facilitated. Drive and anxiety may be reduced by providing informal and formal leadership support and an increasing sense of security. Individuals, groups, and organizations that are frozen into inertia and disbelief when they are seriously threatened may be aroused and alerted. Faced with hasty, poorly thought-out decisions, leaders may delay the premature disclosure of options and call for a reconsideration of proposals. When their followers are engaged in defensive avoidance, leaders may bring them back to reality. Panic can be reduced or avoided by strong leadership that points the way to safety.

Thus, leaders can help their groups to cope with stress in many ways. Nonetheless, they also can cause more of it. Yet, as shall be seen, in general, groups with leaders are likely to cope better with stress than are those without leaders. Groups and organizations that are under stress expect and desire more directiveness from leaders. Moreover, whoever takes the role of leader during times of social stress will be expected to revise goals, define common objectives, restructure situations, and suggest solutions to deal with the sources of stress and conflict (Downtown, 1973). But, as shall also be seen, although directive leadership is most expected, desired, and successful when stress is high, it may not always be the most effective style.

The personality-leader linkage will be affected by stress. Under conditions with short, unpredictable time pressures in which unusual physical and emotional exertion is required, such as in military combat, more charismatic leadership will be seen, in contrast to military leadership in noncombat operations (Bass, 1985a). Personal assertiveness may be a stronger determinant of emergence as a leader under stress. It may be less important in determining emergence as a leader in unstressed circumstances.

Unfortunately, as noted above with abusive leaders, leadership may be the cause, rather than the amelioration, of stressful conditions that result in emotionally driven actions by the followers and poorer long-term outcomes. And the leaders who emerge are likely to be different from those in unstressed situations. They may actually contribute to the stress. Political leaders manufacture crises to enhance their own power, to divert public attention from the real problems, and to gain public support for their arbitrary actions.

Those who are elected to office may be more prone to stress themselves. Sanders and Malkis (1982) manipulated the importance and difficulty of a problem and external incentives involving recognition of esteem and success. They found that Type A (stress-prone) personalities were nominated more often as leaders than were Type B personalities. However, the fewer Type Bs who were chosen as leaders tended to be more effective as individuals in the assigned task than were the Type As (Bass, 1982, p. 135).

Many studies have reported that for subordinates, their immediate supervisor is the most stressful aspect of their work (e.g., Herzberg, 1966). The tyrannical boss is the most frequently mentioned source of stress (McCormick & Powell, 1988). Shipper and Wilson (1992) obtained a correlation of .49 in supervisory goal pressure behavior and perceived tension, according to their 85 hospital employees. Supervisory controlling of details and time emphasis also contributed to tension. Numerof, Seltzer, and Bass (1989) unexpectedly found that when other transformational factors6 were held constant, intellectually stimulating leaders increased the felt stress and job “burn-out” of their subordinates. Misumi (1985) reported the results of a series of experiments that showed that production-prodding leaders giving instructions such as “Work more quickly,” “Work accurately,” “You could do more,” and “Hurry up, we haven’t much time left” generated detectable physiological symptoms of stress. The systolic and diastolic blood pressure of experimental subjects increased, as did their galvanic skin responses. In similar laboratory experiments, such production-prodding leaders caused feelings of hostility and anxiety about the experiment.

In a sample of police officers, half of their “harmful stressors” were the administrative styles of their superiors (Griggs, 1985). Stressful conditions affect what is expected of a leader, who attempts to lead, and who emerges as a leader. In stressful conditions, leaders differ in the extent to which they promote the attainment of goals, the satisfaction of members, and the survival of their groups.

Nystrom and Starbuck (1984) suggested that top managers can guide organizations into crises and intensify the crises by blindness, rigidity, and the inability to unlearn their inadequate old ways of doing things. In the same way, Sutton, Eisenhardt, and Jucker (1986) thought that the Atari Corporation’s decline and imminent collapse was due to its management’s rigidity in continuing to market products that no longer were selling and their failure to develop new products.

Sometimes the decrement in leadership performance may be a consequence of the external imposition of handicaps on the leaders. Thus, loss of support from a higher authority may weaken the leaders’ influence, control of needed resources, and continued attention to the organization’s purposes. During the early years of the Reagan administration, under James Watt, a director who emphasized deregulation and showed a lack of sympathy for environmental concerns, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), came under both clear and unclear threats to its mission from its own leadership, coupled with serious staff and budget cuts. A survey of 181 EPA managers and staff showed a consequential deterioration in their optimism, satisfaction, and identification with the organization and in the quality of supervisor-subordinate relations (Morganthau & Hager, 1981). Again starting in 2001 under the George W. Bush administration, the EPA once again suffered a loss of much of its experienced staff and performance effectiveness.

Prolonged stress from internal or external challenges that are too great for the group to deal with can result in the group’s demise. What leads to the death of some groups and the survival of others over a long period of time? Survival of a group, organization, or community under prolonged stress is closely dependent on leadership that is able to maintain the group or organization’s integrity, drive, and goal direction. Such leadership needs to work with increasing the cohesion and dealing with the reduced performance of tasks by groups that are under continued threat.7 But instead of helping to stave off decline and death, ineffective leaders contribute to the prolonged stress of the group, organization, or community and to its eventual demise.

F. E. Parker (1923, 1927) sent questionnaires to some 3,000 consumer cooperative societies. Among those that had failed, the most frequent reasons were: (1) inefficient leadership and management; (2) declining interest and cooperative spirit among the members; (3) factional disputes among the members; and (4) members’ interference with the management. Blumenthal (1932) attributed the decline of social and fraternal groups in small towns to the departure of young people (the towns’ best leadership potential) for the cities.

Munro’s (1930) study of community service organizations found that ineffective organizations that were less likely to survive were characterized by ineffective leadership, lack of political sagacity, unwise policies and tactics, spasmodic work, and overorganized and duplicated services. Kolb (1933) and Sorokin (1943) observed that without religious purposes and a commitment to an integrative ideology of religion, such as were fostered by leadership, rural communities were less likely to survive disasters. In reviewing the decline and fall of special-interest groups in rural communities, Kolb and Wileden (1927) pointed to factional competition for leadership and irreconcilable differences between leaders and followers.

Most communes cannot survive for any considerable period without strong leadership to maintain discipline and control (Gide, 1930; May & Doob, 1937). Conversely, a whole commune can commit suicide when led to it by a highly charismatic, paranoid leader, as was the case in Jonestown, Guyana, in 1978. The same situation almost occurred in Germany in 1945, when Hitler pleaded for a Götterdämmerung for all Germany, turning in frustration from his fantasy of being Odin the Savior to becoming Odin the Destroyer.

In Chapter 21, we noted that charismatic leaders emerge in times of crisis. They successfully influence their followers but may lead them astray. The leadership that succeeds in influencing followers may not be most effective in stressful situations, particularly in the long run. It may result in faulty decisions made too hastily or defensive reactions, although it is likely to contribute to escape from panic situations. In crises, political leaders and politically adept executives often win the plaudits of their constituents in the short run, but their decisions may turn out to be ineffective and unsatisfying in the long run:

succeeding in … managing stressful organizational environment is … partially due to the exceptionally good political skills possessed by many executives … manifested in social astuteness and … behaviors (foster in followers) feelings of confidence, trust and sincerity. … Executives with political skills … (allow) … followers to interpret the stressors in less aversive ways. (Perrewé, Ferris, Frink, et al., 2000, p. 115)

Crisis provokes a centralization of authority (Hermann, 1963). Berkowitz (1953b) found that both governmental and industrial groups were more likely to accept leadership when the problem was urgent. When followers are under stress, they are likely to accept readily the speedy decisions of directive, task-oriented, structuring leaders. However, Goldstein and Hoffman (1995) suggested that followers in crises who see themselves as efficacious may not accept directive leadership as readily. Additionally, speedy decisions do not necessarily provide the best solutions to the problems facing the followers.

It is not the speed of the decision or the leader’s directiveness that may result in inadequate solutions to the stressful circumstances. It is rapid decision making without the opportunity for careful structuring and support in advance. For, as shall be seen, rapid decision making is generally sought in crises and disasters but is effective if the decisions are not hastily made at the last minute but are based on advance warning, preparation, and organization, along with commitment and support.

As Janis and Mann (1977) noted, when a threat is finally perceived, it generates the desire for prompt, decisive action. Leadership becomes centered in one or a few persons, who gain increased power to decide for the group. The price of the rapid, arbitrary dictation is abuse, corruption, and the loss of freedom when power is placed in the hands of the dictator. Hertzler (1940) examined 35 historical dictatorships and concluded that they arose during crises and when sudden change was desired. In addition, Downton (1973) suggested that followers who are stressed by ambiguity become easily influenced by aggressive, powerful leaders who promise to reduce the ambiguity and restructure the situation.

Alwon (1980) argued that administrators of social agencies must adopt a strong, directive style (even if it means changing their leadership style) during times of crisis to avoid dangers and to seize opportunities. In emergencies, when danger threatens, subordinates want to be told what to do and to be told in a hurry. They perceive that they have no time to consider alternatives. Rapid, decisive leadership is demanded (Hemphill, 1950b). Five hundred groups were described on questionnaires by members on a variety of dimensions formulated by Hemphill. The adequacy of various leadership behaviors was correlated with the groups’ characteristics. Hemphill concluded that in frequently changing and emerging groups, leaders who failed to make decisions quickly would be judged inadequate.

Considerable evidence is available to support the contention that leaders speed up their decision making as a consequence of stress. Their failure to do so leads to their rejection as leaders (Korten, 1962; Sherif & Sherif, 1953). Acceptance of their rapid, arbitrary decisions without consultation, negotiation, or participation8 is also increased. A leader who can react quickly in emergencies will be judged as better by followers than one who cannot.

Flanagan, Levy, et al. (1952) found that, according to respondents, “taking prompt action in emergency situations” was a critical behavior that differentiated those who were judged to be better military officers from those whose performance was judged to be worse. Large-scale surveys by Stouffer, Suchman, DeVinney, et al. (1949) of American soldiers during World War II confirmed that particularly at lower levels in the organization, the military stressed rapidity of response to orders from a higher authority despite the fact that a unit actually operated under battlefield conditions relatively infrequently.

When rapid decisions are needed, executives are likely to become more directive than participative (Lowin, 1968). Consistent with this finding, the more organizations wish to be prepared for emergency action, the more they are likely to stress a high degree of structure, attention to orders, and authoritarian direction. Fodor (1976, 1978) demonstrated that industrial supervisors who were exposed to the stress of simulated, disturbing subordinates became more autocratic in dealing with the situation. College students did likewise (Fodor, 1973b). Half to two-thirds of 181 airmen, when asked for their opinions about missile teams, rescue teams, scientific teams, or other small crews facing emergencies, strongly agreed that they should respond to the orders of the commander with less question than under normal conditions. In an emergency, the commander was expected to “check more closely to see that everyone is carrying out his responsibility.” A majority felt that “the commander should not be ‘just one of the boys’ ” (Torrance, 1956–1957).

In a survey of Dutch naval officers’ performance by Mulder, de Jong, Koppelaar, and Verhage (1986), the officers were more favorably evaluated by their superiors if they were seen to make more use of their formal power in crisis situations than in noncrisis situations. In crisis conditions, both the superiors and the subordinates of the officers looked for more authoritative direction from the officers. At the same time, the officers were evaluated more favorably by their subordinates if they were seen to be more openly consultative in noncrisis situations than in crisis situations. Moreover, the referent power of the officers in the eyes of the subordinates correlated .55 with their consultativeness under noncrisis conditions, but the corresponding correlation was .10 in crisis conditions. The officers relied more on formal and expert power in crisis conditions than in noncrisis conditions, according to their subordinates.

Similarly, militant, decisive, aggressive leadership is demanded during the unstable period of a labor union’s organization as it goes from one emergency to the next. Under stress, strength and activity take on more importance for leadership. After the struggle for survival is over and the union is recognized, the leadership is required to change. Now it must exhibit more willingness to compromise and to cooperate (Selekman, 1947). Confrontation must change to consultation.

Individuals who are more predisposed toward direction and the initiation of structure are more likely to try to take charge when their groups are stressed. They will preempt the leadership role from members who would consult with others before taking action. Given the authoritarian-submissive syndrome, authoritarians who are assigned to the roles of subordinates will be more ready to submit unquestioningly to the dictates of whoever has been assigned the role of leader. Lanzetta (1953) found that aggressive members were more likely to emerge as successful leaders when laboratory groups were stressed by harassment, space, and time restrictions than when no stress was induced. Along similar lines, Ziller (1954) concluded that leaders who accepted responsibility for their groups’ action under conditions of uncertainty and risk were also relatively unconcerned about what the groups thought about the issues.

The same results appeared in still a different context. Firestone, Lichtman, and Colamosca (1975) showed that initially leaderless groups with assertive leaders responded more frequently and more rapidly to a confederate member’s “diabetic reaction” than did groups whose leaders were less assertive. In such emergencies, unassertive leaders tended to be replaced. The holding of the American embassy staff in Teheran in 1979–1980 is a classic example of how an external threat dramatically increased the followers’ (in this case, the American public’s) support for strong leadership to deal with the threats. Ranks were closed, dissension was muted, and rapid decision making was sought from President Jimmy Carter with little examination of the causes, intensity, and risks of the threats or of the costs of taking actions to deal with them. If anything, President Carter failed to come on as strongly and decisively as demanded, although he was effective in ultimately obtaining the release of the hostages. In the face of crises, nations condemn the vacillating, indecisive leader and applaud the would-be hero-savior (Hook, 1943). President Ronald Reagan was much more popular for being seen as bold and decisive in dealing with the Lebanese crisis in 1983, yet his actions were disastrous. Again, George W. Bush’s boldness and decisiveness after the World Trade Center calamity of September 11, 2001, gave him soaring popularity, with more than 90% public support. But when, in the five years that followed, his reactions led to the quagmire in Iraq, his popularity plummeted to only 30%.

When calamity threatens, followers want immediate action to escape. The leader’s attempts to influence them will be accepted and complied with more readily than when such stress is absent. Although a participative discussion may make for better solutions, holding one to generate a high-quality decision to which the group is committed may be unacceptable. The commitment will come from the followers’ restriction of the options they think they have. The leader who shows initiative, inventiveness, and decisiveness is valued most (Barnard, 1948). Helmreich and Collins (1967) observed that participants who faced a fearful experimental situation showed less of a preference for the company of peers and favored being in a leader-dominated group. Polis (1964) also found that under stress, individuals tended to manifest a need for strong leadership and to continue their association with the group. Again, Wispe and Lloyd (1955) concluded that of 43 sales agents, those who generally were less secure and more anxious were also more in favor of their superiors making decisions for them.

One reversal of the call for rapid-decision leadership in crisis conditions was found by Streib, Folts, and LaGreca (1985) in 36 retirement communities. Most residents were ordinarily satisfied to let others make decisions for them, but they wanted the chance to be involved in decision making if crises arose or the stability of the community was threatened. Another contingency was demonstrated in an experiment by Goldstein (1995). When followers had high self-efficacy, they desired less directive leadership no matter how they perceived the leaders’ efficacy. But if the followers were low in self-efficacy, they sought mainly a directive leader when they perceived that the efficacy of the leader was high.

When stress is chronic or prolonged, the same tendencies toward directive leadership and acceptance of it are observed. During World War II, Japanese-American residents of California were interned and subjected to isolation, loss of subsistence, threats to loved ones, enforced idleness, and physiological stress. As a consequence, the internees were apathetic and blindly obedient to influence (Leighton, 1945). Similarly, Fisher and Rubinstein (1956) reported that experimental participants who were deprived of sleep for 48 to 54 hours showed significantly greater shifts in autokinetic judgments, which indicated that they were more susceptible than normal to the social influence of their partners.

Hall and Mansfield (1971) studied the longer-term effects of stress and the response to it in three research and development organizations. The stress was caused by a sudden drop in available research funds, which resulted in strong internal pressures for reduced spending and an increased search for new funds. As would be expected, the response to the threat was to increase the control and direction by the top management and to reduce consultation with the researchers. Subsequently, the effect on the researchers over two years was to decrease their satisfaction and identification with the organization. However, their research performance was unaffected.

To conclude, directive leadership is preferred and will be successful in influencing followers under stress. But such leadership may be counterproductive in the long run.

As was already noted, often it is the political leadership that contrives the threats, crises, and ambiguities. For centuries, political leaders have used real or imagined threat to increase the cohesiveness among their followers and to gain unquestioning support for their own dictates. The common scenario begins with economic weakness and dislocation, followed by international complications, revolution and sometimes civil war, and finally a breakdown of political institutions. The dictator organizes ready-made immediate solutions that soothe, flatter, and exalt the public but do not promote its well-being. Blame is directed elsewhere.

When business and governmental leaders are seen to consult and share decisions with subordinates in times of crises (Berkowitz, 1953b), it is often because they seek bolstering from their subordinates about the wisdom of their already-chosen solutions. Also, they would like to spread the responsibility for the decision from themselves to their group.

We-They Relations. “We-they” discrimination is encouraged by leaders of groups that are in competition and conflict with each other. In-group and out-group differences are magnified. The power of the leaders of the groups is strengthened. Deviants are not tolerated. Thus, Mulder and Sternerding (1963) found, as expected, that when individuals feel threatened from outside, they tend to depend on strong leaders. The leaders, in turn, promote a variety of defense mechanisms as pseudosolutions to the stressful problems facing their constituents, Scapegoats are found to account for the social malaise and economic failures. Fanciful promises of a bountiful future are put forth and accepted. Real social, economic, and political issues are avoided and imagined dragons are slain.

Avoidance can be accomplished by physical self-segregation. This was observed by Hayashida (1976) in the in-group and out-group relations of leaders in organizations under the stress of conflicting ideas with outsiders. The leaders of 146 students in an evangelical Christian organization, whose stated beliefs diverged from the cosmopolitan culture of the campus, isolated themselves formally and informally from the rest of the campus. They coped with intergroup conflict by avoiding it.

The ready acceptance of leadership, which may encourage maladaptive hasty decision making and defensiveness, is also seen in panic conditions. But here, leadership generally seems to offset maladaptive reactions to the panic. Kugihara, Misumi, Sato, and Shigeoka (1982) simulated a panic situation of 672 undergraduates in groups of six. In each group, one student was elected leader. Successful escape from the panic was more likely when the leader was in the same room as the other members than when the leader was placed in another room and was unable to determine the disposition of the members. Conceding to others was higher, and less jamming and aggression occurred, when the leader was present. Other Japanese experiments with simulated panic demonstrated that the greater the ratio of trained leaders to followers, the faster was the escape and the less the jamming and aggression (Misumi & Peterson, 1987).

Hamblin (1958b) found that followers were more willing to accept the influence of leaders during crises than during noncrisis periods. They gave leaders more responsibility and were seen as more competent in coping with the panic that had been induced experimentally. In the same way, A. L. Klein (1976) observed, in an experimental study of panic conditions of too many people trying to escape through the same door, that the stress group preferred a strong leader rather than a leader who was elected under low stress and was more highly acceptable. Acceptance and election, which gave the accepted legitimate leader control of the group’s fate under conditions of low stress, was replaced under conditions of high stress by the group’s choice of a less legitimate but stronger leader, whom the members thought was more competent.

Leadership that is effective in coping with stress implies leadership that results in rationally defensible, high-quality decisions; the appropriate use of available information, skills, and resources; and the enhanced performance of followers in reaching their goals, despite the threats and obstacles to doing so. Reducing stress in the workplace increases productivity (Perry, 1999). House and Rizzo (1972b) and Gillespie and Cohen (1984), among others, showed the importance of leaders in helping their groups cope effectively with conflict and stress. In this respect, individual differences among managers are apparent. Lyness and Moses (1989) were able to separate 258 high-potential AT&T managers by the managers’ comfort in ambiguous environments. According to Moses and Lyness (1988), adaptive managers cope far better with stress in assessment centers than those who are overwhelmed by ambiguity. They have a broad perspective, are sensitive to feedback, and use both intuition and logic to deal effectively with ambiguity. They are comfortable in doing so. Managers who are inflexible in their approach also react to ambiguity but are uncomfortable and ineffective in dealing with it. Still other managers ignore or are overwhelmed by ambiguity.

Among the many ways the leader can effectively reduce stress among followers are: (1) identifying sources of stress and encouraging followers to speak up; (2) encouraging positive language and making affirmative thinking contagious among them; (3) organizing flexibility in the followers’ schedules and arranging for them to maintain control of what they do; (4) organizing the followers in high-risk groups such as nuclear plant operators, hospital trauma teams, and aircraft carrier flight deck crews into high-reliability teams whose members engage in “heedful interaction,” share responsibilities for each other’s safety, cross-monitor each other’s performance, and track each other’s focus of attention (Weick & Roberts, 1993; Weick, Sutcliffe, & Obstfeld, 1999; Xiao, 2002). Among hospital employees using Wilson’s Survey of Management Practices to rate their 85 managers, Shipper and Wilson (1992) found that their tension was significantly lower when there was upward communication and participation (r = −.54), orderly work planning (r = −.55); control of details (r = −.24) and emphasis on time (r = .31); when the manager was expert (r = −.64), delegative (r = −.48), and facilitative (r = −.59); and when the manager provided feedback (r = −.59), recognized for good performance (r = −.58), and made goals clear and important. On the other hand, tension was rated significantly higher with goal pressure (r = .49). Some of these results may have been attributable to the hospital setting. Decreased tension among 46 employees a year later was associated with highly committed managers who practiced instrumental leadership.

Constent with what we have already noted, Burgess, Riddle, Hall, et al. (1992) concluded from a review of 13 articles on the subject of leadership and stress that increased workload, increased time pressure, and increasing task difficulty degrade team performance, communications, team spirit, coordination, and cooperation. But effective team leaders offset these effects with acceptance of input from other members; collecting performance information; and planning, coordinating, facilitating, and structuring the team to work together. Also, the leaders are approachable and unintimidating. They justify and explain their decisions and actions. They use strategic communication to prepare for crises. They justify and explain their actions. The converse was found for ineffective leaders with stressed teams.

Summing up earlier research, Zaccaro, Rittman, and Marks (2001, p. 471) declared that “team members are likely to display less emotional reactions to stressors if leaders provide clear team goals, clear specifications of member roles, … unambiguous performance strategies … and foster a climate where disagreements about team strategies can be aired constructively.”

Leadership that deals effectively with stress cannot be summed up in one simple proposition. For instance, anxious groups and groups that are in conflict call for different types of responses from the leader. For anxious personnel, the leader needs to direct attention to the specifies of their problems. For groups that are facing severe conflicts, the leaders must make possible a full analysis of the costs and benefits of pursuing one goal rather than another. Although active, directive, structuring, and transformational leadership are needed, the nature of conflict—socioemotional, interpersonal, or task-related—may make some difference in the extent to which initiation of structure by the leader will contribute to effectiveness (Guetzkow & Gyr, 1954; R. Likert & J. Likert, 1976). But if the leader has the ability and authority and if the situation generates stress, pressure, and tension to achieve success, directive leadership is still the most likely to be effective (Rosenbaum & Rosenbaum, 1971).

In dealing with inertia or defensive avoidance among followers, the leader must challenge outworn decisions and stimulate the followers to rise beyond their own self-serving rationalizations. Followers need to be made aware of their rationalizations and defense mechanisms that conflict with their true values and interests (Reed & Janis, 1974; Rokeach, 1971). Radical speakers attempt to do so by confronting audiences with the contradictions and inconsistencies of popular, accepted points of view.

In dealing with layoffs, managers can help deal with the stress by fair, equitable treatment, employees’ participation, advance notification, and taking care of the employees to be laid off with severance pay and outplacement programs. The survivors may also be helped by their leaders through empowering, listening, and coaching (Noer, 1993).

Tsur (2003) demonstrated in a content analysis of 202 speeches that the six Israeli prime ministers between 1949 and 1992 used anesthetic rhetoric in Knesset speeches to calm the public in times of Arab-Israeli crises. They pointed out that the causes of the stress were under control and that the leader knew best how to handle the situation. They tended to use only carefully examined, selective information. During such crises, the rhetoric was likely to be less informational about past or future events, mobilizing of support for actions and policies, motivating for future action, apologetic to explain mistakes, or ceremonial to influence identification with common values.

The task makes a difference in the effects of leadership in groups under the pressure to reach decisions quickly. Dubno (1968) assembled experimental groups, some with fast-decision-making leaders and others with slow-decision-making leaders. Congruent groups were those with fast-decision-making leaders and tasks that required speed and quick decision making. Incongruent groups were those with slow-decision-making leaders but with tasks that still required speedy performance and quick decisions. With appointed leaders, the most effective groups were those with slow-decision-making leaders who urged the members to arrive at high-quality solutions under the pressure of speed. For groups with emergent leaders, the most effective were those with fast-decision-making leaders who emphasized the high quality of the members’ performance.

Butler and Jones (1979) also saw that the task made a difference for 776 U.S. Navy ship personnel. They found that when the risks of accidents were high and hazards from equipment were evident (as among engineering personnel), leadership was unrelated to the occurrence of accidents (presumably, structure was already very high). But in the work setting of deck personnel, in which environmental hazards were less evident and personnel were less experienced and hence less clear and competent about tasks, hazards, and goals, the occurrence of accidents was lower when leaders emphasized goals and facilitated interaction. More of any kind of leadership (support, emphasis on goals, and the facilitation of work and interaction) seemed to reduce multiple accidents for deck personnel but was irrelevant to the accident rates of engineering personnel.

Among 84 randomly selected faculty members from 20 departments of two universities, R. Katz (1977) found that the amount of affective and substantive conflict in departments contributed to the felt tension (.49 and .47) and the department’s perceived lack of effectiveness (−.28 and −.29). At the same time, for departments that were in conflict, the leader’s initiation of structure correlated more highly with the department’s effectiveness than when such conflict was absent. The correlation between the leader’s initiation of structure in a department and its effectiveness was .63 when affective conflict was high and only .29 when affective conflict was low. The correlation between initiation of structure and effectiveness was .51 when substantive conflict was high and .38 when substantive conflict was low. In an experiment to confirm these findings, participants were hired to perform routine tasks. For a routine coding task, initiation of structure correlated .46 with productivity when conflict was high and −.62 when conflict was absent. Less clear results materialized with a cross-checking task. Consistent with these findings, Katz, Phillips, and Cheston (1976) demonstrated that more directive, structured, peremptory forcing can often be more effective in resolving interpersonal conflicts than more leisurely problem solving.

Although many studies have found that task-oriented leadership is most likely to be effective under stressful conditions, more often, both task-oriented and relations-oriented performance make for effective leadership under stress. Thus, Numerof and Seltzer (1986) showed that having a superior who scored high on the LBDQ in both initiation of structure and consideration was associated with lower felt stress and burnout among subordinates. And as will be seen, leaders who were high in both task-and relations-orientation were most effective in coping with stress conditions in a series of Japanese experiments. At the same time, task-oriented leaders, those who scored low on Fiedler’s Least Preferred Coworker (LPC) Questionnaire, were found by Kim and Organ (1982) to be more sensitive to choosing competent subordinates when stressed by the pressure for effective task outcomes. Sample and Wilson (1965) also found that groups with task-oriented leaders performed better than those with person-oriented leaders under conditions of stress but not under routine conditions. Long-term psychosomatic stress reactions among workers were found in Arvonen’s (1995) Swedish survey when immediate supervisors lacked a relations orientation. However, reversed results were obtained by Fiedler, O’Brien, and Ilgen (1969), in a study of American volunteers in Honduras, who found that low-LPC, task-oriented leaders were more effective in relatively stress-free villages, whereas high-LPC, relations-oriented leaders exerted a more therapeutic effect in villages that were under more stress. The reversal may be a function of how task orientation was measured. It may be that in both stressed and nonstressed situations, although relations-oriented, supportive, considerate leadership generally contributes to adaptive performance and satisfaction in the groups and organizations that are led, task-oriented, instrumental, structuring leadership becomes essential, especially when stress and conflict are high. Such task structuring may still contribute to performance in the nonstressed condition, but it may be less essential.

Bliese, Ritzer, and Thomas (2001) pointed out that the reason that evidence is mixed about the importance of leader behavior such as leader support as a buffer against stress among followers is due to: (1) the lack of statistical power in the studies using too few subjects, (2) the lack of connection between the support and the specific source of stress, and (3) the need for WABA analysis to tease out the individual personalities of the stressed raters. They obtained ratings of both commissioned officer and noncom support from 2,403 U.S. Army personnel from 31 companies in two brigades. The assessed stress perceived was interpersonal conflict.

Soldiers in units with a high degrees of leadership support had high continuance commitment to the army even when they perceived a high degree of stress in their work. Cummins (1990) showed that the job stress in their workplace of 96 business students was buffered by supportive (high-LPC) supervisors.

In coping with conflict with their own superior officer, subordinate leaders’ experience and intelligence appear to have opposite effects (Fiedler, Potter, Zais, & Knowlton, 1979; Potter & Fiedler, 1993).9 Among 158 infantry squad leaders who perceived a very high degree of stress in their relations with their immediate superiors, the squad leaders’ experience, but not their tested intelligence, correlated with their rated performance as leaders (Fiedler & Leister, 1977b). When perceived stress was low, experience correlated between −.20 and .00 with rated performance. When perceived stress was high, experience correlated between .39 and .66 with rated performance. For 45 first sergeants in the U.S. Army who were studied by Knowlton (1979), correlations between their rated performance and their intelligence were between .51 and .78 when they perceived little conflict between themselves and their superiors. The correlations ranged from −.04 to .24 when such perceived conflict was high. Similar findings were obtained by Zais (1979) for line and staff officers in nine army battalions; by Frost (1983) for 123 first-level and second-level superiors in an urban fire department; by Potter (1978) for 103 Coast Guard officers; and by Borden (1980), who collected data from 45 company commanders, 37 company executive officers, 106 platoon leaders, 42 first sergeants, and 163 platoon sergeants in a combat infantry division. Here, the leaders’ intelligence correlated .44 with their performance when their conflict with their own superior was low; .31, when the conflict was moderate; and −.02, when the conflict was high.

Given the importance of preparedness in coping with stress, the positive impact of experience in dealing with conflict is not unexpected, but the reverse effects for intelligence are yet to be explained. In a bureaucracy, the highly intelligent subordinate leader may be a threat to his or her superiors, who, in turn, downgrade the subordinate’s performance. Conflict with superiors appears to be more disturbing to the potentially creative, intelligent, subordinate leader. The leader who is in conflict with higher authority is likely to have less “influence upstairs,” which reduces the leader’s likely effectiveness and ability to use his or her intelligence.

Fiedler’s (1982) cognitive resource theory is an effort to explain the findings. Fiedler assumed that the intelligent leader’s contributions to the group’s effectiveness depend on his or her direction of plans, decisions, and ideas. But under stressful conditions, the quality of such plans, decisions, and ideas is associated more highly with the leader’s experience than with his or her intelligence. The highly intelligent leader will focus on problems that are not directly relevant to the task and will rely on intellectual solutions to tasks, when the tasks may not be amenable to intellectual solutions. A nondirective intelligent leader will make even less of a contribution to groups under stress, primarily because he or she will prolong the decision-making process, be inactive, or perform poorly.