7

The regicides’ revival, rise, and decline

The conscience of an honest man,

Is full as royal as a king.

John Leete, The Family of Leete (1906), 170

Talk of freedom and liberty in early nineteenth-century America did not, of course, apply to the almost 4 million African-American slaves in southern slave-owning states. As Americans continued to drive westwards, the question of whether the new states would be slave-owning or free brought North and South into a civil war that would lead to the deaths of over 600,000 combatants. Amidst such devastation, the fate of three Puritan regicides in colonial America might easily seem irrelevant. Indeed, at first sight, Mount Hope’s publication in 1851 marked the beginning of the end of interest in the regicides in American literature, with that interest disappearing totally by the outbreak of the civil war a decade later. After decades of processing the cataclysmic violence wrought during the French Revolution, perhaps authors now found it too difficult to celebrate the bloody regicide that had occurred just across the English Channel.1 We might also consider the effect of ‘angel saturation’: a popular motif had become too widespread and those authors who strived for originality would move gradually away from the increasingly stale story of Goffe and Hadley.

On the contrary, though, with the exception of the years following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in 1865, interest in Whalley and Goffe persisted. The reminder in Lincoln’s 1863 Gettysburg Address that America was a nation ‘conceived in liberty’ would have evoked memories of the circumstances of that conception, including the revolutionary inheritance bestowed on Americans by their seventeenth-century English ancestors. The process of nation-building, both as Americans continued to push westwards and as they attempted to recover from their civil war divisions, continued to feature aspects of the American colonial past. This was especially the case towards the end of the nineteenth century when America’s startling growth, the social dislocation caused by westward resettlement, rapid urbanization, and memories of the destruction augured by mechanized warfare provoked some Americans to embrace their colonial past as a simpler and more desirable time. And two figures by now inexorably associated with that colonial past were Edward Whalley and William Goffe.

America’s civil war and the regicides

At 11 a.m. on Thursday, 10 December 1863—two years into the American civil war—the Massachusetts Historical Society assembled to hear its president, Robert C. Winthrop, read an extract from the diary of William Goffe, which had been found among his family papers. The following year, John Gorham Palfrey published the third volume of his History of New England—the part that dealt with Goffe at Hadley—even though the publication process had been interrupted by the civil war. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Dr Grimshawe’s Secret, an unpublished romance written during the American civil war, features a possible regicide in its web of references to British and American history. The story takes place near a Salem graveyard and includes a character who dreams of an ancient English estate from which a regicidal Puritan fled to New England, where he started a family.2

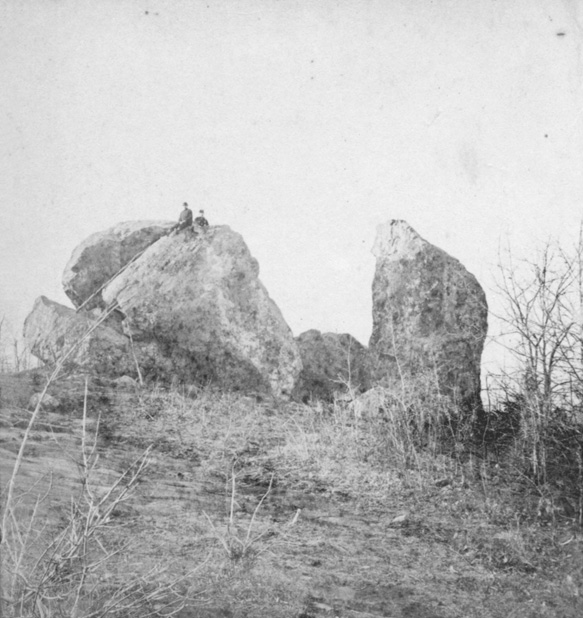

Continued interest in the regicides at this time might be explained in two divergent ways. Retreat into colonial history may have offered an escape from the miseries of America’s own civil war; the regicides’ story was devoid of slavery and the debates surrounding it. Perhaps those civil war soldiers who had their picture taken atop the Judges Cave outside New Haven were indulging in their own form of escape (see Figure 12).3 Conversely, the story of Whalley and Goffe may have been attractive to Union supporters, as it was rendered as a story about liberty—albeit a different kind of liberty from the emancipation of slaves. The way that the New England states concentrated on their own peculiar history might also have constituted an exercise in forming their own identity—either for the Union during the war years or for America as a whole in subsequent decades.

Whatever the explanation, the regicides clearly had not left the American cultural landscape by the early 1860s. It is possible that Abraham Lincoln’s assassination in 1865 temporarily reduced the American taste for literature that celebrated the deaths of national leaders. John Wilkes Booth, the assassin, claimed that he was carrying out tyrannicide, a term strongly associated with the English regicides, while Reverend Henry Smith, pastor of the North Presbyterian Church in Buffalo, New York, called the assassination ‘deeper dyed in guilt than any regicide in the history of the world’.4 The Portuguese observer Rebelo da Silva called Lincoln’s assassination ‘essentially, a regicide’.5 Caroline Hayden, in Our Country’s Martyr (1865), lamented ‘’Tis nothing new, this crime of regicide’.6 Warren Hathaway, also writing in 1865, went further and described Wilkes Booth as ‘more than a regicide’, echoing Charles I’s martyrology Eikon Basilike of 1649, by describing Lincoln as ‘sacred . . . in the estimation of Heaven’.7 This might explain why James Bayard Taylor’s The Strange Friend, arguably the only published creative piece to address the regicides in the late 1860s, had merely the faintest echoes of Whalley, Goffe, and Dixwell, as it featured a nineteenth-century fugitive hiding from the British authorities in Pennsylvania.8 Soon, though, the Colonial Revival and centenary of the American Revolution stimulated, on the page and the stage, even more interest in proto-revolutionary regicides, their lives, and their afterlives.

Centenaries and cycles

When the regicides’ letters were printed in 1868, their editor noted that this ‘revived the interest’ that had ‘always been felt’ in Whalley, Goffe, and Dixwell. But it was not until the final decades of the century that there was another surge of literature concerned with the regicides.9 There have been suggestions that, after the 1870s, authors tended to shun the legend of Hadley: a local historian, George Sheldon, had encouraged cynicism about the Angel story in 1874 and Goffe’s hoary and theatrical appearance faded from public view because of this ‘glare of realism’.10 But we should not assume that the regicides’ story as a whole disappeared from public consciousness, or that the Angel of Hadley had appeared in print for the last time.

We can explain the late nineteenth-century renewal of interest in the regicides in a number of ways. In both the North and the South, the American civil war led to a growth in nationalism: the process of reconciliation included a focus on national traditions that bound individuals and parties in a recently divided nation.11 The regicides’ story was untainted by recent debates and divisions and was one that had inspired American national pride just half a century previously. Furthermore, the regicides’ revival was part of a broader cultural movement that occurred in the late nineteenth century. The Colonial Revival looked back nostalgically to a time before the American civil war, while criticizing the cacophonous, corrupt, and commercialized tone of contemporary industrialized life. An additional purpose of the movement was to heal and rebuild the nation by remembering that the colonial period had been, it was claimed, a more peaceful time of honesty and virtue. By combining European colonial styles with the patriotism inspired by a renewed interest in the lives of revolutionary figures, both Europhile and American appetites were satisfied.12

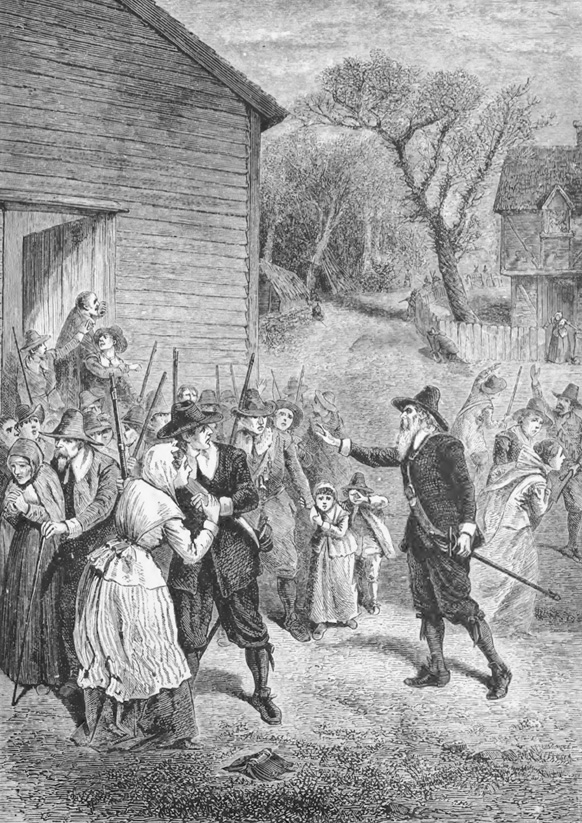

This was a potent combination and one that promoted a revival of interest in Anglo-American colonial subjects, especially those that pointed the way to American liberty like the stories of Whalley, Goffe, and Dixwell. Thus, in 1873 Israel Perkins Warren’s book—The Three Judges: Story of the Men who Beheaded Their King—was published in New York. Four years later, Robert Patterson Robins wrote about ‘Edward Whalley, The Regicide’ for the first volume of The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. Another visual representation of the ‘Angel of Hadley’ appeared in 1883 in Augustus L. Mason’s The Romance and Tragedy of the Pioneer Life. This rendering, much less intense and action-packed than The Perils of Our Forefathers or Goffe Repulsing the Indians, featured no Native Americans at all, focusing instead on the trepidation of the Hadley residents and a less distinctive or forceful, if still bearded, Goffe (see Figure 13). In 1884 the historian Henry Howe recounted the story of Whalley and Goffe hiding in their cave.13 Two years later George Bancroft published his cryptic observations about Goffe’s ignorance of the ‘true principles of freedom’.14

This interest continued into the 1890s. Perhaps inspired by Frederick Hull Cogswell’s article on ‘The Regicides in New England’ for the New England Magazine, ‘many visitors’ were reported at the cave above New Haven, in which Whalley and Goffe had sheltered in 1661.15 By 1895 Charles Knowles Bolton felt he could not write a poem of colonial romance and courtship without including a digression about Whalley and Goffe’s adventures: their hiding in New Haven, Governor Endecott’s pretended interest in their capture, towns being searched, and the regicides’ imagined evasion of Kellond and Kirke under a footbridge.16 While the regicides’ story amounted to only a small portion of the poem—approximately thirty out of 550 lines—Bolton thought he could attract readers by advertising the poem as ‘a versified narrative of the time of the regicides’. Such was Bolton’s enthusiasm for these regicides that he considered William Goffe to be one of his country’s ‘founders’ when he published a series of mini-biographies of notable individuals who had travelled from Europe to North America in the seventeenth century.17

There is another explanation for the increased attention given to the regicides in the late nineteenth century: some Americans were very interested in the cyclical nature of their past. Writers and readers of American history were sensitive to what they considered centennial parallels in New England history. John Gorham Palfrey noted what he called ‘chronological parallelisms’: between the Nichols, Carr, Cartwright, and Maverick commission of 1664–5 and the Stamp Act of 1765; between the beginning of the ‘attack’ on New England’s ‘freedom’ in 1675—the start of King Philip’s War and, it was thought, the liberating appearance of Goffe’s ‘Angel of Hadley’—and the invasion of 1775 ‘which led to [America’s] independence of Great Britain’.18 There was also a chronological convenience in Bacon’s Rebellion, a reaction to alleged British colonial tyranny, and the Declaration of Independence a hundred years later. This parallel was not lost on J.R. Musick, who called his novel based on Bacon’s Rebellion A Century Too Soon: ‘though one hundred years before liberty was actually obtained, the sleeping goddess seemed to have opened her eyes on that occasion and yawned’.19 In the late nineteenth century, then, it was not unnatural for Americans to cast their minds back a century or two and to see centennial parallels between events that had happened in the eighteenth century and those that had taken place in the seventeenth. The centennial of the American Revolution provoked reflection on the causes of that revolution and meditation on the seeds sown in a colonial American soil naturally fertile for autonomy and independence.

Reflection on the seventeenth century would have involved looking back to the regicides on the run in America; the opportunity to bring seventeenth-century history into the scope of the American Revolution furnished one reason why the regicides and their protectors retained their significance into the late nineteenth century. They provided ‘evidence’ that the American revolutionary spirit had its beginnings in the early colonists and their love of freedom. On 4 July 1883 at an Independence Day celebration at Woodstock, Connecticut, Leonard Woolsey Bacon read a poem that celebrated those colonial Americans who had anticipated the independence of America in 1776. One of them was William Leete, famed for his protection of the fugitive regicides:

And tell of Guilford’s William Leete,

Who stretched the State’s right arm to hide

In many a wilderness retreat

The vengeance hunted regicide,

And told the bearers of the ban,

Signed and broad sealed “that tender thing

The conscience of an honest man,

Is full as royal as a king.”20

Bacon was following in the footsteps of his father, Leonard Bacon, pastor of the First Church of New Haven, who had argued in his Thirteen Historical Discourses of 1839 that the New Haven colonists’ protection of the regicides was a ‘fearless yet discreet assertion of great principles of liberty’.21

Stage to page

We have already seen early nineteenth-century dramatic portrayals of the regicides on the American stage in Barker’s Tragedy of Superstition, Stone’s Metamora, and the play form of Cooper’s The Wept of Wish-ton-Wish. Whalley and Goffe once again trod the boards in the late nineteenth century, in Edward Grimm’s The King’s Judges: An Original Comedy, published in San Francisco in 1892. In this play Grimm again underlined an implicit connection between the revolutionary spirit of America’s seventeenth-century settlers and the revolutionary mood of the eighteenth-century colonists, while further twisting the actual events that had surrounded Whalley and Goffe in the 1660s and 1670s. Grimm’s New Haven inhabitants conclude that they ‘have no confidence in Kings’ and that ‘the colonies will have no peace until they hoist their own sails and steer for liberty’. When the play’s characters hear news of the executions in London of the regicides Thomas Harrison, Thomas Scot, and Hugh Peters, they declare that ‘this action of the king may cause another revolution’; indeed ‘it ought to re-kindle the republican feeling, if there is a spark left in the ashes’.22

The story of the regicides on the run would have provided sufficient drama to keep a theatre audience entertained, even if some inventive scene changes would have been required to convey the sense of the regicides travelling from place to place. Grimm’s description of his play as a ‘comedy’, however, stretches the imagination. Apart from some exchanges in Act II, scene iii reminiscent of Sir John Falstaff and Mistress Quickly in Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2, the remainder of the play is a straight history (or pseudo-history) with the odd moment of romance. The central figures are cast in familiar terms: Charles II is described as ‘a prince destitute of honor and virtue’, who threatens the New England colonies’ ‘civil and religious privileges’; ‘a trickster and deceiver’ who is ‘always ready to promise but never ready to keep his word’; and who is ‘just as stupid and as obstinate as his father, who is certainly one of the most stupid asses that ever lived’. Whalley and Goffe, however, are ‘men of uncommon talent, and, by their dignified manners and grave deportment, command universal respect’; they are ‘upright, honorable and desirable citizens’.23

There are references in The King’s Judges to genuine historical events, including the open manner in which Whalley and Goffe had arrived in Massachusetts Bay,24 and the New Haven residents’ discussion of plans to capture the regicides.25 But while the play is set in New Haven in 1661, there is a curious twist: prominent individuals in the true story of the regicides play no part and are replaced by fictional characters. Kellond or Kirke, for example, appears as a Captain Dobson, the earl of Clarendon’s former groom who is in pursuit of the regicides, is imprisoned by the colonists, and is then driven out of New Haven with the threat of a noose awaiting him, should he ever return.26 Other elements of the play have no basis in fact whatsoever: Goffe ends up buying a farm in New Haven near the cave where the fugitives can hide if any more commissions arrive from England to search for them.

As with Barker, Stone, and Cooper in the first half of the century, not all late nineteenth-century fictional accounts of the regicides were quite so sympathetic to the regicides. John R. Musick’s A Century Too Soon (1893), already noted for making the historical links between 1649, 1676, and 1776, was less optimistic than The King’s Judges about the regicides’ reception in New England. William Goffe arrives in Boston from New Plymouth with his six-year-old daughter, Ester. They try to find shelter at an inn but the inn’s owner refuses to help them. They continue searching and think they have found refuge but a man appears to tell their would-be host to ‘drive them hence. No good ever comes to one harboring such’. They arrive at a blacksmith’s house but Goffe and Ester are rejected again, as ‘to harbour a regicide might mean death on the scaffold’. They are ‘rejected at every door’, until finally a Puritan family gives them shelter.

Musick is closer to Thomas Hutchinson than Ezra Stiles in his assessment of the regicides, though his portrayal omits Whalley and overlooks the kind reception initially given them in Cambridge and Boston by Reverend Charles Chauncey, Governor Endecott, Edward Collins, Elder Frost, and John Norton. Indeed, Musick’s ambivalence towards the regicides emerges in his plagiarism of the historian George Bancroft, as he calls Goffe ‘a firm friend of the family of Cromwell, a good soldier and an ardent partisan, but ignorant of the true principles of freedom’.27 Musick also suggests that Charles II was not ‘a bloodthirsty man’, but ‘good-natured, thinking more of pleasures and beautiful mistresses than of vengeance; but it was only natural that he should feel anxious to bring the murderers of his father to the scaffold’.28 Yet despite Musick’s less sympathetic approach to the regicides and moderate assessment of Charles II, he could not avoid seeing Bacon’s Rebellion as a precursor to the American Revolution and associating those two American struggles for liberty with the principles of the English Revolution, by placing the Goffe family alongside Bacon’s ‘little army of dauntless patriots’.29

There was a curious tendency for regicide-preoccupied novelists in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to claim that their subject had been neglected. When Frederick Hull Cogswell came to write his account of the regicides, he observed that ‘for the most part the tale has slept as undisturbed as the bones of the forefathers whose living eyes looked upon the scenes and the persons involved’. His claim was not correct: his ‘tale of early colonial times’, published in 1896, followed the publication of several accounts of Whalley and Goffe, whether fictional, semi-fictional, or non-fictional. Like many of those accounts, Cogswell was determined to portray Whalley and Goffe in a positive light by imagining certain characteristics that were to be admired in both men. Whalley was ‘tall and soldierly in bearing, his venerable head adorned with snowy white hair’; his face ‘would anywhere be judged to be of scholarly taste and habit’. Goffe was ‘of firm and not too heavy build, with a magnificent head rising from a strong but graceful neck and a broad pair of shoulders’.30 Cogswell was creating pen-portraits of individuals he viewed as Anglo-American heroes.

Cogswell imagines the regicides conversing with their colonial protectors and portrays the former as stoic and honourable men who refuse to put the latter in danger. ‘If we remain here, we render thy position one of extreme danger’, they are imagined telling William Leete, ‘and we would sooner perish in the storm than betray a friend’.31 The regicides’ colonial protectors similarly are portrayed in the warm glow of admiration and adoration. Leete is described as ‘wise, learned, pious, honest and industrious’.32 In contrast, Royalist agents are cast as one-dimensional villains: Kellond is described as having a ‘nature at once grasping and insatiable’;33 Charles II is called ‘the jesting libertine’ as well as a ‘faithless despot’ and a ‘tyrant’.34 Instead of seeing the lack of interest from London in the regicides as evidence that Charles was preoccupied or pragmatic, Cogswell interpreted the quiet interludes when there were no attempts to capture them as ‘the quiet of the panther that crouches hidden until the prey is off its guard’.35 Davenport is portrayed reflecting on the regicide: ‘a cruel necessity to many minds, but right or wrong, the men who decreed it were the saviours of England’. Robert Treat is imagined describing the regicide as ‘one of the noblest acts in all history, in showing the world that tyrants can no longer trample on the rights of the people’.36 The only ‘absolute monarchy’ in the colony is the schoolhouse; ‘everywhere else the individual was sovereign, and the executive was nothing but the symbol of the universal will’.37

Like Cogswell, when Margaret Sidney wrote her own story centred on the regicides, The Judges’ Cave (1900), she claimed that the topic had ‘had too scant notice from the pen of novelist or poet’. Perhaps she had not read Scott, Southey, or the other twenty or so novelists and poets who had written about Whalley, Goffe, and Dixwell. Sidney had grown up next to the New Haven burial ground, where she had frequently visited what she thought were the regicides’ graves. She often walked to the regicides’ cave where her imagination was unleashed and her heart throbbed ‘in sympathy’ with the regicides’ cause. Sidney’s novel is an encomium to her hometown of New Haven whose own safety was jeopardized for becoming a ‘bulwark of protection’ of liberty.38 Four years later, in W.H. Gocher’s Wadsworth (1904), it was not New Haven that was the ‘cradle of democracy’, but another town through which the regicides had passed, in March 1661, and where Goffe was living by September 1676: Hartford.39

The regicides’ tale had begun as one that catered to the American taste for the supernatural, but it then became, for the most part, a tale that catered to the American taste for liberty. Stories like the Angel of Hadley satisfied both palates—a spectral figure preserving the lives and liberties of New England colonists. There were some authors like Bancroft, Barker, and Stone who were less effusive about the virtues of the regicides, but they were in the minority. Wherever and whenever there was a tyrant—preferably an English one—there was a literary regicide ready to challenge him. In the American imagination a regicide could appear in any episode interpreted as a stepping stone on the road to American independence and liberty, like Bacon’s Rebellion or resistance to Edmund Andros. Indeed, by 1882 the regicides and individuals like Bacon were considered to be so similar that the two coalesced visually into one another. In Charlotte M. Yonge’s Pictorial History of the World’s Great Nations, Chapman’s Perils of Our Forefathers (engraved by McRae) was redrawn with Nathaniel Bacon replacing William Goffe. The Angel of Hadley had become the Hero of Virginia. The replacement was exactly the same figure who inspired his followers in exactly the same way, only one had greyer hair and a beard (see Figure 14).

Bodies

Following on from the myths in Ezra Stiles’s History of the regicides, regicide myths were born from later corruptions of their story, the blending of fact with fiction, the desire for adventure consonant with heroic proto-American revolutionaries, and an appetite for caricatures of historical personalities. But such distortion did not end with histories and novels. Folklore and myth also found their way into stories about the regicides’ final resting places. This is a subject of more than morbid interest; preoccupation with the regicides’ bodies hints at continued interest in their fate among nineteenth- and twentieth-century Americans, and illustrates the distortion of historical truth by local folklore and family traditions. It furthers the idea that the regicides, alive or dead, have long been ripe for myth-making and appropriation by generations of Americans keen to associate themselves, or their localities, with these apparently revolutionary heroes.

Claims and counter-claims about the graves of Whalley and Goffe have been made and disputed for a number of reasons. First, there is little or no definitive documentation to prove their exact burial locations. Second, the regicides’ protectors had an interest in keeping Whalley and Goffe’s final resting places secret: they would not have wanted to leave the fugitives’ bodies vulnerable to punitive revenge and exhumation by Royalists, as had been the fate of the corpses of Oliver Cromwell, Henry Ireton, and John Bradshaw in London in 1661. And third, they would not wish to draw attention to their own protection of the regicides and risk harsh treatment of their own communities by Charles II and his agents in America. As the decades and centuries went by, however, and the perceived threat of retribution from London receded, a number of different localities laid claim to being the final resting places of the regicides. They took pride in their history of protecting such guardians of liberty and wished to stake their claim to an intimate association with them.

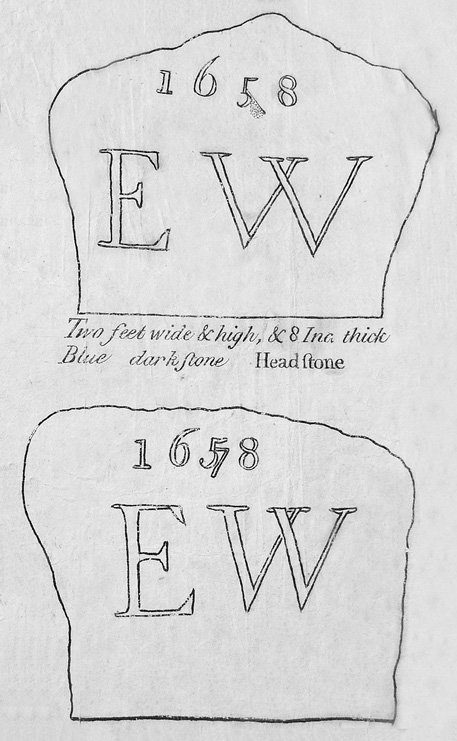

Various theories have been suggested concerning Whalley’s final resting place. Though some are plausible, few are convincing. One theory, which originated in the folklore of the young girls of Hadley, suggested that Whalley had been buried under a fence on the border of Peter Tilton’s land in the town; that way neither he nor his neighbour could be blamed for protecting a regicide, alive or dead.40 This was undermined in 1795 when the wall of the cellar under Reverend Russell’s house in Hadley was removed. About four feet underground, under the front kitchen wall, the earth was loose. Further excavation of this area uncovered some pieces of wood, some flat stones, shards of human bone, two teeth, and the whole thighbone of a tall man. The prevalent interpretation of the discovery was that these were the bones of Edward Whalley, who had died in Hadley in the mid-1670s.41 While this theory had its detractors (one thought that Whalley’s body would not have decomposed so much so quickly),42 the discovery appeared to undermine another tradition that Whalley had been buried on the green in New Haven under a stone marked ‘E.W. 1653’. This was unlikely anyway: a regicide’s grave would not have been marked in this way. The date ‘1653’ may have been a red-herring, designed to put regicide-hunters off the scent. Or it may have been a misreading of ‘1673’ or ‘1678’, more likely dates for Whalley’s death. Stiles thought the possible Whalley headstone so important that he included it as one of his plates in his History, along with a possible corruption of the ‘5’ to a ‘7’ (see Figure 15). A more likely explanation, however, is that the New Haven gravestone, with the inscription ‘E.W.’, belongs to Edward Wigglesworth, who died in the colony on 1 October 1653.43

The wrong Whalley?

The development of antiquarian history in the nineteenth century brought with it renewed interest in Whalley and Goffe, those who had assisted and protected them, and what eventually happened to the regicides’ bodies.44 In the first edition of The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Robert Patterson Robins sought to provide a new theory about Edward Whalley’s later life, attempting to pierce the ‘almost impenetrable fog of mystery’ surrounding Whalley’s final years.45 His idea was novel but wholly incorrect: Robins granted Whalley an extra-long life that carried on beyond Hadley or New Haven, or any of the other locations that had been suggested for the regicide’s death and burial. Instead, Robins suggested, Whalley had fled to the county of Somerset in Maryland, where he lived until he was 103 years old.

Even before this theory is investigated in detail, it sounds improbable. We know from the regicides’ correspondence in the 1670s that Whalley’s health was failing, and that he almost certainly died in Hadley in the course of that decade. What, then, was Robins’s reasoning? First, he suggested that the bones discovered in Russell’s cellar need not have been those of Whalley. They could easily have been Goffe’s. Second, Robins relied on a letter written by Thomas Robins of Worcester County, Maryland, in July 1769. An eager genealogist, Thomas Robins, tracked down an Edward Middleton, whom he considered to be Whalley under a pseudonym. Middleton had arrived in Virginia in 1681, where he was met by his two brothers-in-law. He then travelled to Maryland, staying first at the mouth of the Pocomoke River, before moving to Sinepuxent, where he purchased twenty-two acres and named the property ‘Genezar’. Middleton/Whalley then moved to the southernmost point of the land—‘South Point’—with his family in 1687. It was soon afterwards, Robins claims, that Middleton/Whalley felt safe enough to reveal his real name after the Glorious Revolution. Middleton/Whalley then lived at South Point with his family—including three sons and three daughters—until his death in 1718.46

Thomas Robins’s letter was a curious one. At first sight, it appeared to be the work of someone keen to associate himself with a regicide and lover of liberty. The writer was laying claim to regicidal ancestry on the unlikely basis that a regicide who was close to death in the 1670s somehow managed to live for another four decades and sire six children in America. The neglect of the available historical sources and the suspension of common sense—by both Robert Patterson Robins and Thomas Robins—would be the traits of people desperate to cement a link with regicidal heroes. But the final lines of Thomas Robins’s letter suggested that he was not so proud of the association: he noted that ‘had he received that due to him, [Whalley] would have suffered and died on the scaffold as did many of his traitorous companions’. And just in case we were unsure of his loyalty to the British monarchy, he signed off ‘Vivat rex’.47

Robert Patterson Robins was keener than his ancestor, it seems, to claim a genealogical link with Whalley the regicide. He took Thomas Robins’s letter as sound historical proof and added further points to suggest that the man who died at South Point in 1718 was indeed Whalley and that he had good reasons to settle in Maryland: first, the renewed threat of persecution after Edward Randolph’s arrival in 1686 as James II’s commissioner; second, the relative safety of a proprietary government rather than a charter province; third, the warmer climate that would have eased the pain in Whalley’s ageing body; and fourth, the presence of his family en route in Virginia. Robins also encouraged his readers to think that Middleton was Whalley because of his reluctance to stay anywhere ‘public’ where he might be discovered: first Virginia, then the mouth of the Pocomoke River.48 Indeed, there were few places to live more remote than South Point, Sinepuxent.

Only after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, allegedly, did ‘Middleton’ feel safe enough to reveal his real name. But the ‘Middleton’ pseudonym itself enables us to unpick the Robins theory and suggest that both men have the right real name, but the wrong man. Robert Patterson Robins claims that the regicide Whalley used the name ‘Middleton’ as a pseudonym because it was his wife’s maiden name. So it was; but it was also a name that might have been adopted by one of Whalley’s children who wanted to conceal his own identity. Overexcited at the prospect that the Whalley who had settled in South Point was the famous signatory of Charles I’s death warrant, both Robert Patterson Robins and his ancestor Thomas Robins overlooked the fact that there was another Whalley travelling around the American colonies in the late seventeenth century who also had reason to keep his real surname secret: because of his participation in Nathaniel Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia in 1676.

Indeed, from the moment it was published, readers of The Pennsylvania Magazine were not convinced by Robins’s theory. W.H. Whitmore wrote from Boston in June 1877, suggesting a number of improbabilities in the Robins argument. First, if it was the regicide Whalley who died in 1718, one might expect his will to make mention of his very advanced age, which it does not. Second, the will hints that his wife survived him, but Whalley’s wife (Mary Middleton) died in the early 1660s49 and none of the surviving sources suggests that he remarried in America. Third, the will of ‘Edward Wale’ of Worcester County, Maryland, dated 21 April 1718, is signed with an ‘x’ rather than a proper signature.50 According to the Robins theory, Whalley the regicide would have been around 103 by now and would have suffered decades of ill health; so perhaps he simply could not summon the strength to sign his will properly. Whalley the regicide had demonstrated in 1649 that he was perfectly capable of signing his name. Indeed, it was his signature that had got him into so much trouble in the first place. Instead, it was more likely that the Whalley who lived in South Point was a son of the regicide—Edward Whalley’s sixth child (also called Edward)—or just a man who happened to share the regicide’s name.

Perhaps the South Point Whalley did take part in Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676. After Nathaniel Bacon’s death, the rebels’ last stand took place at New Kent and an Edward Whalley Jr was one of the main fomenters of the continued disloyalty. This Whalley fled from the rebellion and escaped the capital punishment that would have befallen him, had he been captured. It is plausible that between 1676 and 1681, this younger Whalley travelled from New Kent, across or around Chesapeake Bay, to Sinepuxent. Had this been the case, the younger Whalley would have avoided using his famous and inflammatory surname, opting instead for the anonymity provided by his mother’s maiden name. Furthermore, he would have sought a remote settlement, somewhere like South Point, to avoid being discovered and brought to justice. By the late 1680s, the political climate had changed sufficiently for this Whalley to come out into the open: Governor Berkeley, who initially sought retribution for Bacon’s Rebellion, had been away from the colonies for a decade, and the accession to the British throne of William and Mary might give rise to a political amnesty for those who had been disloyal to the Stuart monarchy both at home and overseas. One of the younger Edward Whalley’s children was named Nathaniel—a tribute, it seems, to one of his former fellow rebels.51

Finding Goffe

Thomas Robins was not the only person to think that a regicide had spent some time in Virginia. Colonel Francis Willet of Narragansett, Rhode Island told Ezra Stiles that ‘Theophilus Whalley’ (who, he claimed, was actually Goffe) had moved from Hadley to Virginia. Willet then had ‘Whalley’ (Goffe) returning to New England to live among the Narragansett people. Thomas Hutchinson wrote to Stiles about this theory in June 1765, insisting that Willet was ‘certainly mistaken’. Hutchinson alluded to an ‘old woman’ in Narragansett, mentioned by Stiles, whom he would visit should he find himself in the area—an insinuation that Willet’s theory derived from an unreliable local oral tradition.52 Stiles was not so quick to dismiss the idea: he included a chapter on Willet in his history of the regicides and, faced with the weight of popular belief in Willet’s theory on a visit to Rhode Island in 1782, briefly entertained the notion that Goffe—‘Theophilus Whalley’—had travelled to Virginia and later to the Narragansetts.53 Timothy Dwight also reported the tradition that Goffe ended up in Rhode Island, but this myth had the regicide living with Whalley’s son once Goffe had left Hadley for Connecticut, and then New York, where he had apparently disguised himself by carrying ‘vegetables at times to market’.54

After 1795, as news spread of the bones discovered under Russell’s house, most observers, with the exception of Thomas Robins, were satisfied that Whalley’s final resting place had been revealed. But Goffe’s burial place was more open to speculation, as his final years were more obscure and his flight from Hadley could have taken him in many different directions. One theory suggests that Goffe actually remained in Hadley and was buried under Russell’s house around 1685, the time when Russell felt he could leave his residence without concern and travel to Boston.55 However, only one body was found under Russell’s house; so speculation about the fate of the regicides continued.

As with Whalley, it has been suggested that Goffe was also buried in New Haven, this time under a headstone marked ‘M.G. 80’: the ‘M’ was, it was argued, an upside-down ‘W’—a clever method of deception to deflect attention from the real ‘William’ lying underneath. Although this suggestion stemmed from a romantic desire to have regicides resting side by side (for those who thought Whalley was buried under New Haven’s ‘E.W.’ gravestone), even one of the theory’s earliest proponents admitted that it needed ‘a slight stretch of imagination’.56 The claim goes that Goffe fled to New Haven from Hartford in 1680 once Leete had ordered a renewed search for the regicide, but that Goffe died soon after.57 Various objections, however, undermine this ingenious theory: first, Goffe was probably dead by the time Leete had ordered the search, hence the fact that he had ordered a search in the first place; second, Goffe’s supporters would not have given him such a prominent burial site in case his body might be exhumed and exposed to humiliation; and third, the burial stone ‘M.G. 80’ almost certainly covers Governor Matthew Gilbert, who died in 1680.58

Much of the confusion about the final resting places of the regicides arose from the desire, especially in the nineteenth century, that the regicides should be close to one another in death, just as they had been close to one another spiritually and ideologically in life.59 As we saw in Chapter 6, Ezra Stiles’s grandson, Jonathan Leavitt, was almost overcome with emotion on 11 April 1819 when he chanced upon what he thought were the regicides’ graves in the New Haven burial ground: ‘Here I read the names of the judges of king Charles—men who shone in their day of glory’; beneath him, he thought erroneously, ‘lie outstretched, the bones of the mighty’.60

In the nineteenth century Middle Haddam, now an historic district of East Hampton, Connecticut, was a quiet hamlet with its own story to tell of the regicides. It has a fine episcopal church dating from 1786 and was the birthplace of James Brainerd Taylor, the evangelist of the Second Great Awakening. Because of these features, Middle Haddam was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1984. Yet Middle Haddam has an additional claim, if a rather unsound one, to historical note. The New York Times reported a long-standing tradition, still proudly upheld in the 1890s, that Middle Haddam was the final resting place of William Goffe. However, Middle Haddam’s absence from the now well-documented account of Whalley and Goffe’s travels might cause us to raise an eyebrow at the historical accuracy of this claim. Although there are still periods for which we cannot verify the regicides’ location with complete accuracy, we might be suspicious of the claim that Goffe’s grave is ‘beneath a gnarled apple tree on a grassy hillside’ in Middle Haddam, where he once lived in a log cabin ‘a stone’s throw’ from that apple tree.61 The apple tree was allegedly planted over the body to stop various groups finding the regicide and exhuming him, since medical students and gravediggers (apparently after Goffe’s diamond-hilted sword) were interested in discovering his location. It is an attractive legend but it does not ring true.

Goffe, according to this tradition, had moved to Middle Haddam after his flight from Hadley. He had avoided Weathersfield and Middletown because they had many inhabitants who were keen to surrender the fugitive to the colonial authorities. Middle Haddam was situated deep in the forest, where Goffe could hide, with a spring of clear water from which the regicide and his horse could drink. Goffe allegedly settled here with his son, Gideon, with whom he lived until his death in 1685. This tale, however, once again stemmed from family tradition and historical hearsay. A Captain Nymphas Wright claimed that he had dismantled Goffe’s log cabin as a young man and in his old age mentioned this story to Edwin A. Brainerd, who had bought what was believed locally to be ‘Goffe’s Lot’.

Yet the inaccuracy of the folklore and the manner of its presentation in The New York Times calls into question the historical veracity of this whole tale. The article reported that Brainerd was descended from the clergyman who had sheltered Goffe in Hadley, ‘Rev. Mr. Robinson’, whom we know was actually Russell. It also suggested that Whalley and Goffe were on the run with a regicide named ‘Maxwell’, clearly an inaccurate rendering of ‘Dixwell’. Finally, a son named Gideon is a curious addition to the regicide story. A man named ‘Gideon Goff’ had indeed settled in Middle Haddam by 1710,62 but evidently some overexcited locals took this ‘Goff’ to be connected with the fugitive Goffe, conveniently reinterpreting the decades before this settlement and blending together two families of similar name to suggest that Middle Haddam and its residents had an intimate connection with the regicide.

Family traditions about the regicides’ burial places continued into the twentieth century. In 1953 Eleanor Smith Teesdale wrote an account of what she believed to be William Goffe’s burial place—not, this time, in Middle Haddam, but in Colebrook, Connecticut, about ninety miles north-east of Hadley. Teesdale stated that she used to visit her grandfather’s house in North Colebrook, before it was destroyed by fire around 1930. One of her family pastimes was visiting the ‘grave of the regicide’, which involved scrambling through undergrowth and vaulting fences to reach a stone on a rocky hillside, inscribed with the words ‘William Goffe, Regicide’. Teesdale surmised that Colebrook was a likely place for Goffe to be buried because it was the closest uncultivated area to the west of the region where Goffe was being hunted: the flatlands around the Connecticut River. On his death, Teesdale suggested, Goffe was carried to a remote and inaccessible resting place safe from those who might exact revenge on the body. She had last seen the stone in 1925, but it could not be found upon further investigation in 1951.

The Teesdale family tradition is more credible than the Robins theory, but there are still reasons to be sceptical. First, there is no demonstrable evidence beyond a charming anecdote which no-one else has ever corroborated. Second, the inscription is odd: even if Goffe’s body were laid to rest in a remote location, it would still be peculiar to put his name on the gravestone, let alone his role as ‘regicide’. Goffe’s friends could not be certain that the grave would remain undiscovered or that the body, if found, would not be desecrated. Other reservations have been put forward: first, it would have been a very awkward and arduous journey to transport a bulky and conspicuous coffin some ninety miles from Hadley to Colebrook; second, no road existed until the 1760s to allow its transportation through the dense forest. Perhaps, therefore, the ‘gravestone’, discovered by the Teesdale family, was one of the stones placed in 1717 to mark the boundary between Massachusetts and Connecticut, with an inscription imagined from the lines weathered into the fieldstone.63 The Teesdale case study illustrates two points: first, the regicides were viewed in such a positive way that it was considered desirable to associate oneself and one’s family with them; and second, the regicides remained of interest to at least some people in twentieth-century America.

Rise and decline

Indeed, between the outbreak of World War I and the start of World War II, the regicides had enjoyed a renewal of interest in America. This period, the tail-end of the Colonial Revival, began with a notice in The New York Times, suggesting that the Judges Cave was a ‘Good Goal for Motorists’: ‘Good automobile roads lead to both the caves which sheltered the men, and those living in the neighborhood are always willing to point out the historic spots’.64 In 1918 the Saturday Chronicle carried an outline of Whalley and Goffe’s travels from Boston to Hartford.65 Two years later, the regicide letters were published in the journal Americana.66 In 1927 Aline Havard’s The Regicide’s Children was published in New York, advertised as a ‘thrilling life of danger that was led in the days of the Puritans . . . told in a way to hold the interest of older and younger boys’.67

It was in the 1930s, though, that Whalley, Goffe, and Dixwell enjoyed a greater revival of interest, almost entirely due to one man: Lemuel Aiken Welles. From his student days at Yale, Welles was fascinated by American colonial history and, especially, the relationship between English colonists and their home country. As an undergraduate, he wrote with respect and affection about the ‘sterling English qualities’ early colonists had brought with them, as reflected in their ‘establishment of institutions of learning, religion and government at a time when bread cost him a struggle’. The ensuing two or three centuries, though, had been characterized by what Welles saw as a diminution of these qualities: ‘although many of the first settlers were men of scholarship and culture, their children could hardly write’. Welles ascribed this deterioration to the fact that the early settlers spent more time clearing forests and listening to long Puritan sermons than they did appreciating culture, while the ‘finer families’ intermarried with ‘the inferior classes’, leading to ‘clods’ being descended from colonial governors.68 Welles himself was a descendant of Thomas Welles, governor of Connecticut between 1655 and 1656. So his Connecticut-based family interest, his time studying in New Haven, his later membership of the Sons of the American Revolution, and his evident enthusiasm for the Colonial Revival combined when he came across the story of Whalley, Goffe, and Dixwell.

Following a career in law, Welles published the first full modern history of the regicides in New England. Although New York’s Grafton Press only printed 500 copies, that it was printed in New York suggests that interest in Whalley, Goffe, and Dixwell extended further than the local historians of New Haven. (That said, it was the Tercentenary Commission of the State of Connecticut Committee on Historical Publications which, inspired by Welles’s book, commissioned him to write a short account of the regicides in Connecticut, published in New Haven in 1935.) Yet there was a certain naivety to Welles’s interpretation of the regicides. He read the available sources at face value and it was clear which side Welles supported. He called Oliver Cromwell ‘one of the bravest men who ever lived’ and implied that he did not sympathize with the errand on which Kellond and Kirke had been sent.69 Welles—again, a Son of the American Revolution—was not the first observer of the regicides to sympathize with them and the revolutionary ideas they bestowed on America. More problematic was his uncritical approach to the claims of the colonists who protected Whalley, Goffe, and Dixwell. He gave the impression that Governor Endecott had been serious in his attempts to capture the regicides. He tried to explain the delay between Endecott’s receiving the 5 March 1661 mandate and his appointment of Kellond and Kirke to pursue Whalley and Goffe, by arguing naively that the order ‘had to be sent to Cambridge to be printed’ and that Endecott could not act without first summoning his magistrates.70 Welles also believed that the wily William Leete had wanted to write out the arrest warrant that would have allowed Kellond and Kirke to look for the regicides in New Haven, but the magistrates Matthew Gilbert and Robert Treat stopped him.71 In addition, Welles read uncritically the reports of Leete’s ‘depression’ about the regicides’ episode,72 without pausing to consider whether Leete was just trying to cover his back after a period of remarkable wriggling, twisting, and turning that had allowed the regicides to retain their freedom in the New World.

Nonetheless, Welles’s book appears to have stimulated another period of interest in the regicides. Aside from Welles’s own article for the Tercentenary Commission of the State of Connecticut, The New Haven Journal Courier from June 1934 carried the tale of Whalley and Goffe and, once again, associated the regicides’ story with the American Revolution. Richard Sperry, who had sheltered Whalley and Goffe, could not be mentioned without the acknowledgement of one of his descendants, also named Richard and a ‘colonel in the Revolutionary Army’.73 Generations of Connecticut schoolchildren were taught about the regicides in Lewis Sprague Mill’s The Story of Connecticut (1932) which was still available into the late 1950s.74 There was some academic interest, too, in the origins of the Angel of Hadley, so prominent in nineteenth-century American literature.75 In the late 1930s, Laicita Worden Gregg painted a mural, Planning the Escape of Whalley and Goffe, featuring some Clark Gable-esque regicides and New Haven colonists (see Figure 16). This mural was part of the Public Works for Art Program (PWAP) which paid artists $35 per day to produce artwork accessible and visible to ordinary people. Gregg’s mural was displayed at Woolsey School in Fair Haven for generations of pupils to shuffle past and maybe glance up at. Then, in 1939, Karl Anderson painted Pursuit of the Regicides for the lobby of the Westville Post Office in New Haven.

The outbreak of World War II understandably appears to have reduced curiosity in Whalley, Goffe, and Dixwell. By 1953, when Eleanor Smith Teesdale wrote her version of Goffe’s burial, interest in the regicides had become more and more specialized, eccentric even, and the subject of hazy genealogical conjecture instead of wide public interest and healthy historical investigation. Struggling to explain the reception of the regicides to an audience unfamiliar with seventeenth-century politics, one author in 1964 invoked an historical context he thought would be more familiar: ‘imagine . . . that John Wilkes Booth [Lincoln’s assassin] escaped safely to Virginia, to be warmly greeted by Jefferson Davis [president of the Confederate States], prayed over in Richmond churches, and sumptuously dined by the president of William and Mary College’.76 Such a trend is perhaps puzzling when we read the words of Louis B. Wright, who discussed the role of British history in American culture in his lecture The British Tradition in America (1954). Wright insisted that:

what went on in western Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, especially what went on in England, is critically important for an understanding of American cultural history . . . we have remained essentially British in the quality of our civilization . . . we have inherited a great tradition which we have made our own and we are often not aware of its British origins . . . The civilization developed within the British Isles between 1485 and 1715 . . . had such extraordinary vigor that it had not yet lost its dynamic power. It carried over to the New World and became the assimilative force which created the American people as we are.77

In Wright’s terms, then, American culture was forged in the crucible of seventeenth-century British history, which had civil war and regicide at its heart. Wright’s view was an Anglophilic and inappropriately monochromatic Caucasian representation of American culture. Wright was delivering his arguments in 1954 in Birmingham, Alabama, which within a decade would become the focus of the Civil Rights Movement. Narrowly defined interpretations of American culture like Wright’s would soon be dismissed. As the historiographical lens widened to incorporate the diversity of American history and culture, English Puritans like Whalley, Goffe, and Dixwell lost their once-central position in the American consciousness. Instead, they became subjects fit for little more than children’s books like Myra Clarke Crandell’s Molly and the Regicides (1968).

By the 1960s, the trauma of the assassination of John F. Kennedy on 22 November 1963 (followed by that of Martin Luther King on 4 April 1968 and Robert F. Kennedy on 5 June 1968) may have further deterred American readers from thinking about those who kill their leaders. In the same way that there was little published interest in the regicides after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, if we look beyond Molly and the Regicides the once-popular American regicide industry dwindled after the assassination of Kennedy. Obviously there is a difference between an allegedly tyrannical leader dying judicially after a trial in the seventeenth century (however distressing that may have been to his supporters) and a democratically elected leader being murdered in cold blood in the twentieth. But meditation on the former would have led to dwelling on the latter at a time of national trauma, a trauma intensified by the ubiquity of Kennedy’s assassination. Media coverage made the event unavoidable, as it was replayed on television in people’s front rooms and permeated their magazines and newspapers. As with Lincoln’s assassination, reflections on Kennedy’s death used the term ‘regicide’ to refer to the act of the killing or to refer to the individual doing that killing. Leo Sauvage in March 1964, for example, referred to the president’s assassin Lee Harvey Oswald as ‘a psychopathic regicide’.78 That Kennedy’s presidency had the monarchical overtones of dynasty and personal glamour at the so-called court of Camelot would have made parallels between presidential assassination and regicide all the more potent.