Let your food be your medicine and let your medicine be your food.

—HIPPOCRATES

Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to initiate the reader into the growing field of nutritional medicine by focusing on key dietary recommendations for a health-promoting diet. Most naturopathic physicians utilize these principles to help educate and inspire their patients to attain a higher level of wellness. The critical importance to health of a whole-foods diet cannot be overstated.

It is now well established that certain dietary practices can either cause or prevent a wide range of diseases, particularly chronic degenerative diseases such as heart disease, cancer, and other conditions associated with aging. In addition, more and more research indicates that certain diets and foods offer immediate therapeutic benefit.

There are two basic facts underlying the diet-disease connection: (1) a diet rich in plant foods (whole grains, legumes, nuts and seeds, fruits, and vegetables) is protective against many diseases that are extremely common in Western society, and (2) a low intake of plant foods is a causative factor in the development of these diseases and provides conditions under which other causative factors are more active.

The Importance of a Plant-Based Diet

Although the human gastrointestinal tract is capable of digesting both animal and plant foods, a number of physical characteristics indicate that Homo sapiens evolved to digest primarily plant foods. Specifically, our 32 teeth include 20 molars, which are perfect for crushing and grinding plant foods, along with 8 front incisors, which are well suited for biting into fruits and vegetables. Only our front four canine teeth are specifically designed for meat eating. Our jaws swing both vertically to tear and laterally to crush, but carnivores’ jaws swing only vertically. Additional evidence that supports the body’s preference for plant foods is the long length of the human intestinal tract. Carnivores typically have a short bowel, whereas herbivores have a bowel length proportionally comparable to that of humans. Thus the human bowel length favors plant foods.1

Nonhuman wild primates such as chimpanzees, monkeys, and gorillas are also omnivores or, as often described, herbivores and opportunistic carnivores. They eat mainly fruits and vegetables but may also eat small animals, lizards, and eggs if given the opportunity. Only 1% and 2%, respectively, of the total calories consumed by gorillas and orangutans are animal foods. The remainder of their diet is from plant foods. Because humans are between the weights of the gorilla and orangutan, it has been suggested that humans are designed to eat around 1.5% of their diet as animal foods.2 Most Americans, however, derive well over 50% of their calories from animal foods.

Although most primates eat a considerable amount of fruit, it is critical to point out that the cultivated fruit in American supermarkets is far different from the highly nutritious wild fruits these animals rely on. Wild fruits have a slightly higher protein content and a higher content of certain essential vitamins and minerals, but cultivated fruits tend to be higher in sugars. Cultivated fruits are therefore very tasty to humans, but because they have a higher sugar composition and also lack the fibrous pulp and multiple seeds found in wild fruit that slow down the digestion and absorption of sugars, cultivated fruits raise blood sugar levels much more quickly than their wild counterparts.

Wild primates fill up not only on fruit but also on other highly nutritious plant foods. As a result, wild primates weighing 1/10th as much as a typical human ingest nearly 10 times the level of vitamin C and much higher amounts of many other vitamins and minerals. Other differences in the wild primate diet are also important to point out, such as a higher ratio of alpha-linolenic acid (an essential omega-3 fatty acid) to linoleic acid (an essential omega-6 fatty acid).2

Determining what foods humans are best suited for may not be as simple as looking at the diet of wild primates. There are some structural and physiological differences between humans and apes. The key difference may be the larger, more metabolically active human brain. In fact, it has been theorized that a shift in dietary intake to more animal foods may have been the stimulus for brain growth. The shift itself was probably the result of limited food availability that forced early humans to hunt grazing mammals such as antelope and gazelles. Archaeological data support this association: the brains of humans started to grow and become more developed at about the same time as evidence shows an increase in bones of animals butchered with stone tools at sites of early villages.

Improved dietary quality alone cannot fully explain why human brains grew, but it definitely appears to have played a critical role. With a bigger brain, early humans were able to engage in more complex social behavior, which led to improved foraging and hunting tactics, which in turn led to even higher-quality food intake, fostering additional brain evolution.

Data from anthropologists looking at hunter-gatherer cultures are providing much insight as to what humans are designed to eat; however, it is very important to point out that these groups were not entirely free to determine their diets. Instead, their diets were molded by what was available to them. Regardless of whether hunter-gatherer communities relied on animal or plant foods, the incidence of diseases of civilization, such as heart disease and cancer, is extremely low in such communities.3

It should also be pointed out that the meat that our ancestors consumed was much different from the meat found in supermarkets today. Domesticated animals have always had higher fat levels than their wild counterparts, but the desire for tender meat has led to the breeding of cattle that produce meat with a fat content of 25 to 30% or more, compared with less than 4% for free-living animals and wild game. In addition, the type of fat is considerably different. Domestic beef contains primarily saturated fats and is very low in omega-3 fatty acids. In contrast, the fat of wild animals contains more than five times as much polyunsaturated fat per gram and has good amounts of beneficial omega-3 fatty acids (approximately 4 to 8%).4

The Pioneering Work of Burkitt and Trowell

Much of the link between diet and chronic disease originated from the work of two medical pioneers: Denis Burkitt, M.D., and Hugh Trowell, M.D., authors of Western Diseases: Their Emergence and Prevention, first published in 1981.5 Although now extremely well recognized, their work is actually a continuation of the landmark work of Weston A. Price, a dentist and author of Nutrition and Physical Degeneration. In the early 1900s, Dr. Price traveled the world observing changes in the structure of the teeth and palate as various cultures discarded traditional dietary practices in favor of a more “civilized” diet. Price was able to follow individuals as well as cultures over periods of 20 to 40 years and carefully documented the onset of degenerative diseases as their diets changed. On the basis of extensive studies examining the incidence of diseases in various populations and his own observations of primitive cultures, Burkitt formulated the following sequence of events:

• First stage. In cultures consuming a traditional diet consisting of whole, unprocessed foods, the incidence of chronic diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, and cancer is quite low.

• Second stage. As the culture moves toward eating a more Western-style diet, there is a sharp rise in the number of individuals with obesity and diabetes.

• Third stage. As more and more people abandon their traditional diet, conditions that were once quite rare become extremely common. Examples are constipation, hemorrhoids, varicose veins, and appendicitis.

• Fourth stage. Finally, with full westernization of the diet, other chronic degenerative or potentially lethal diseases, such as heart disease, cancer, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and gout, become extremely common.

Since Burkitt and Trowell’s pioneering research, a virtual landslide of data has continually emphasized the Western diet as the key factor in virtually every chronic disease, especially obesity and diabetes. The following table lists diseases with convincing links to a diet low in plant foods. Many of these now common diseases were extremely rare before the 20th century.

Diseases Strongly Associated with a Low-Fiber Diet |

|

TYPE OF DISEASE |

SPECIFIC DISEASES |

Metabolic |

Obesity, gout, diabetes, kidney stones, gallstones |

Cardiovascular |

High blood pressure, strokes, heart disease, varicose veins, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism |

Colonic |

Constipation, appendicitis, diverticulitis, diverticulosis, hemorrhoids, colon cancer, irritable bowel syndrome, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease |

Other |

Dental caries, autoimmune disorders, pernicious anemia, multiple sclerosis, thyrotoxicosis, psoriasis, acne |

Trends in U.S. Food Consumption

During the 20th century, food consumption patterns changed dramatically. Total dietary fat intake rose from 32% of calories in 1909 to 43% by the end of the century. Overall carbohydrate intake dropped from 57% to 46%; and protein intake remained fairly stable at about 11%.

Trends in Quantities of Foods Consumed per Capita (Pounds per Year) |

||||

FOODS |

1909 |

1967 |

1985 |

1999 |

Meat, Poultry, and Fish |

|

|

|

|

Beef |

54 |

81 |

73 |

66 |

Pork |

62 |

61 |

62 |

50 |

Poultry |

18 |

46 |

70 |

68 |

Fish |

12 |

15 |

19 |

15 |

Total |

146 |

203 |

224 |

199 |

|

|

|

|

|

Eggs |

37 |

40 |

32 |

32 |

|

|

|

|

|

Dairy Products |

|

|

|

|

Whole milk |

223 |

232 |

122 |

112 |

Low-fat milk |

64 |

44 |

112 |

101 |

Cheese |

5 |

15 |

26 |

30 |

Other |

47 |

159 |

190 |

210 |

Total |

339 |

450 |

450 |

453 |

|

|

|

|

|

Fats and Oils |

|

|

|

|

Butter |

18 |

6 |

5 |

5 |

Margarine |

1 |

10 |

11 |

8 |

Shortening |

8 |

16 |

23 |

22 |

Lard and tallow |

12 |

5 |

4 |

6 |

Salad and cooking oil |

2 |

16 |

25 |

29 |

Total |

41 |

53 |

68 |

70 |

|

|

|

|

|

Fruits |

|

|

|

|

Citrus |

17 |

60 |

72 |

79 |

Noncitrus, fresh |

154 |

73 |

87 |

115 |

Noncitrus, processed |

8 |

35 |

34 |

37 |

Total |

179 |

168 |

193 |

231 |

|

|

|

|

|

Tomatoes |

46 |

36 |

38 |

55 |

Dark green and yellow |

34 |

25 |

31 |

39 |

Other, fresh |

136 |

87 |

96 |

126 |

Other, processed |

8 |

35 |

34 |

39 |

Total |

224 |

183 |

199 |

259 |

|

|

|

|

|

Potatoes, White |

|

|

|

|

Fresh |

182 |

67 |

55 |

49 |

Processed |

0 |

19 |

28 |

91 |

Total |

182 |

86 |

83 |

140 |

|

|

|

|

|

Legumes |

|

|

|

|

Dry beans, peas, nuts, and soybeans |

16 |

16 |

18 |

22 |

|

|

|

|

|

Grain Products |

|

|

|

|

Wheat products |

216 |

116 |

122 |

150 |

Corn |

56 |

15 |

17 |

28 |

Other grains |

19 |

13 |

26 |

24 |

Total |

291 |

144 |

165 |

202 |

|

|

|

|

|

Sugar and Sweeteners |

|

|

|

|

Refined sugar |

77 |

100 |

63 |

68 |

Syrups and other sweeteners |

14 |

22 |

90 |

91 |

Total |

91 |

122 |

153 |

159 |

Modified from United States Department of Agriculture, Food Review 2000, 23:8–15

Compounding these detrimental patterns are the individual food choices people make. The biggest changes were significant rises in the consumption of meat, fats and oils, and sugars and sweeteners in conjunction with the decreased consumption of noncitrus fruits, vegetables, and whole-grain products. The largest change was the switch from a diet with a high level of complex carbohydrates, which naturally occur in grains and vegetables, to a tremendous and dramatic increase in the number of calories consumed from simple sugars. Currently, more than half of the carbohydrates being consumed are in the form of sugars (sucrose, corn syrup, etc.) being added to foods as sweetening agents. High consumption of refined sugars is linked to many chronic diseases, including obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and cancer.

The Government and Nutrition Education

Throughout the years, various governmental organizations have published dietary guidelines, but the recommendations of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) have become the most widely known. In 1956, the USDA published Food for Fitness: A Daily Food Guide. This became popularly known as the Basic Four Food Groups. The Basic Four were:

Milk group (milk, cheese, ice cream, and other milk-based foods)

Meat group (meat, fish, poultry, and eggs, with dried legumes and nuts as alternatives)

Fruit and vegetable group

Breads and cereals group

One of the major problems with the Basic Four Food Groups model was that graphically, it suggested that the food groups are equal in health value. The result was overconsumption of animal products, dietary fat, and refined carbohydrates, and insufficient consumption of fiber-rich foods such as fruits, vegetables, and legumes. This in turn has resulted in many premature deaths, chronic diseases, and increased health care costs.

As the Basic Four Food Groups became outdated, various other governmental as well as medical organizations developed guidelines of their own designed to reduce the risk of either a specific chronic degenerative disease, such as cancer or heart disease, or all chronic diseases.

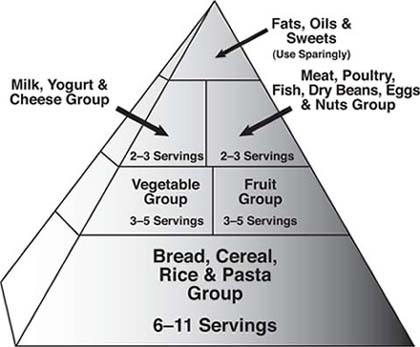

U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Pyramid

In an attempt to create a new model in nutrition education, the USDA first published the Eating Right Pyramid in 1992. That resulted in harsh criticisms from numerous experts and other organizations. One big question was “Is it appropriate to have the USDA making these recommendations?” After all, the USDA serves two somewhat conflicting roles: (1) it represents the food industry and (2) it is in charge of educating consumers about nutrition. Many people believe that the pyramid was weighted more toward dairy products, red meat, and grains because of influence from the dairy, beef, and grain farming and processing industries. In other words, the pyramid was designed not to improve the health of Americans but rather to promote the USDA agenda of supporting multinational agrifoods giants.

One of the main criticisms of the Eating Right Pyramid was that it did not stress strongly enough the importance of high-quality food choices. For example, the bottom of the pyramid represented the foods that should make up the bulk of a healthful diet: the Bread, Cereal, Rice, and Pasta Group. Eating 6 to 11 servings a day from this group was supposedly the path to a healthier life. But the Eating Right Pyramid did not take into consideration how quickly blood glucose levels rise after certain types of food are eaten—an effect referred to as the foods’ glycemic index (GI). The GI is a numerical scale used to indicate how fast and how high a particular food raises blood glucose (blood sugar) levels. Foods with a lower GI create a slower rise in blood sugar, whereas foods with a higher GI create a faster rise in blood sugar. Some of the foods that the pyramid was directing Americans to eat more of, such as breads, cereals, rice, and pasta, can greatly stress blood sugar control, especially if derived from refined grains, and are now being linked to an increased risk for obesity, diabetes, and cancer. The pyramid did not stress that individuals need to choose whole, unrefined foods in this category.

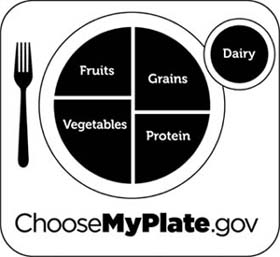

In June 2011 the USDA unveiled a new food icon, MyPlate, to replace the food pyramid. This simplified illustration is designed to help Americans make healthier food choices. MyPlate is the first step in a multiyear effort to raise consumers’ awareness and educate them about eating more healthfully. The initial launch came with some simple recommendations:

Balancing Calories

• Enjoy your food, but eat less.

• Avoid oversize portions.

Foods to Increase

• Make half your plate fruits and vegetables.

• Make at least half your grains whole grains.

• Switch to fat-free or low-fat (1%) milk.

Foods to Reduce

• Compare sodium in foods like soup, bread, and frozen meals—and choose the foods with lower numbers.

• Drink water instead of sugary drinks.

We hope this new campaign will be more successful than prior efforts—and that the program will focus on communicating important nutritional guidance and not yield to political pressure.

USDA MyPlate

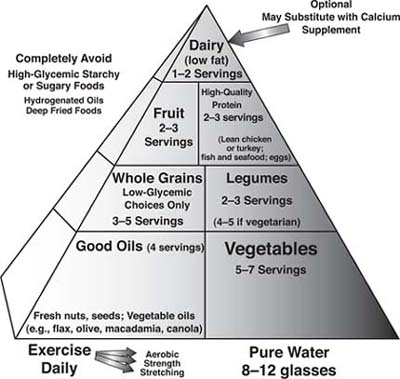

The Optimal Health Food Pyramid

On the basis of existing evidence we have created the Optimal Health Food Pyramid, which incorporates the best of two of the most healthful diets ever studied—the traditional Mediterranean diet and the traditional Asian diet. In addition, the Optimal Health Food Pyramid more clearly defines healthful choices within the categories and stresses the importance of vegetable oils and regular fish consumption as part of a healthful diet. We based the Optimal Health Food Diet on the following nine principles:

1. Eat a rainbow assortment of fruits and vegetables.

2. Reduce exposure to pesticides, heavy metals, and food additives.

3. Eat to support blood sugar control.

4. Do not overconsume animal foods.

5. Eat the right types of fats.

6. Keep salt intake low, potassium intake high.

7. Avoid food additives.

8. Take measures to reduce foodborne illness.

9. Drink sufficient amounts of water each day.

The Optimal Health Food Pyramid

A diet rich in fruits and vegetables is the best bet for preventing virtually every chronic disease. That fact has been established time and again in scientific studies on large numbers of people. The evidence in support of this recommendation is so strong that it has been endorsed by U.S. government health agencies and by virtually every major medical organization, including the American Cancer Society. “Rainbow” simply means that selecting colorful foods—red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and purple—provides the body with powerful antioxidants as well as the nutrients it needs for optimal function and protection against disease.

The Rainbow Assortment of Foods

RED

Apples (red)

Bell peppers (red)

Cherries

Cranberries

Grapefruit

Grapes (red)

Radishes

Raspberries

Plums (red)

Strawberries

Tomatoes

Watermelon

DARK GREEN

Artichoke

Asparagus

Bell peppers (green)

Broccoli

Brussels sprouts

Chard

Collard greens

Cucumbers

Green beans

Grapes (green)

Honeydew melon

Kale

Leeks

Lettuce (dark

green types)

Mustard greens

Peas

Spinach

Turnip greens

YELLOW AND LIGHT GREEN

Apples (green or yellow)

Avocado

Banana

Bell peppers (yellow)

Bok choy

Cabbage

Cauliflower

Celery

Fennel

Kiwi fruits

Lemons

Lettuce (light green types)

Limes

Onions

Pears (green) or yellow)

Pineapple

Squash (yellow)

Zucchini

ORANGE

Apricots

Bell peppers (orange)

Butternut squash

Cantaloupe

Carrots

Mangoes

Oranges

Papaya

Pumpkin

Sweet potatoes

Yams

PURPLE

Beets

Blueberries

Blackberries

Currants

Cabbage (purple)

Cherries

Eggplant

Onions (red)

Grapes (purple)

Pears (red)

Plums (purple)

Radishes

Fruits and vegetables are so important in the battle against cancer that some experts have said, and we believe, that cancer is a result of a “maladaptation” over time to a reduced level of intake of fruits and vegetables. As a study published in the medical journal Cancer Causes and Control put it, “Vegetables and fruit contain the anticarcinogenic cocktail to which we are adapted. We abandon it at our peril.”6 A vast number of substances found in fruits and vegetables are known to protect against cancer.7–9 Some experts refer to these as “chemopreventers,” but they are better known to many as phytochemicals. Phytochemicals include pigments such as carotenes, chlorophyll, and flavonoids; dietary fiber; enzymes; vitamin-like compounds; and other minor dietary constituents. Although they work in harmony with antioxidants such as vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium, phytochemicals exert considerably greater protection against cancer than these simple nutrients.

Examples of Anticancer Phytochemicals |

||

PHYTOCHEMICAL |

ACTIONS |

SOURCES |

Carotenes |

Antioxidants Enhance immune functions |

Dark-colored vegetables such as carrots, squash, spinach, kale, tomatoes, yams, and sweet potatoes; fruits such as cantaloupe, apricots, and citrus |

Coumarins |

Antitumor properties Enhance immune functions Stimulate antioxidant mechanisms |

Carrots, celery, fennel, beets, citrus fruit |

Dithiolthiones, glucosinolates, and thiocyanates |

Block cancer-causing compounds from damaging cells Enhance detoxification |

Vegetables in the brassica family—cabbage, broccoli, brussels sprouts, kale, etc. |

Flavonoids |

Antioxidants Direct antitumor effects Immune-enhancing properties |

Fruits, particularly darker fruits such as berries, cherries, and citrus fruits; also tomatoes, peppers, and greens |

Isoflavonoids |

Block estrogen receptors |

Soy and other legumes |

Lignans |

Antioxidants Modulate hormone receptors |

Flaxseed and flaxseed oil; whole grains, nuts, and seeds. |

Limonoids |

Enhance detoxification Block carcinogens |

Citrus fruits, celery |

Polyphenols |

Antioxidants Block carcinogen formation Modulate hormone receptors |

Green tea, chocolate, red wine |

Sterols |

Block production of carcinogens Modulate hormone receptors |

Soy, nuts, seeds |

In the United States, more than 1.2 billion lb of pesticides and herbicides are sprayed on or added to food crops each year. That is roughly 5 lb of pesticides for each man, woman, and child. There is a growing concern that in addition to the significant number of cancers caused by the pesticides directly, exposure to these chemicals damages the body’s detoxification mechanisms, thereby raising the risk of cancer and other diseases. To illustrate just how problematic pesticides can be, take a quick look at the health problems of the farmer. The lifestyle of farmers is generally healthy: compared with city dwellers, farmers have access to lots of fresh food; they breathe clean air, work hard, and have a lower rate of cigarette smoking and alcohol use. Yet studies show that farmers have a higher risk of lymphomas, leukemias, and cancers of the stomach, prostate, brain, and skin.10–12 Exposure to pesticides may explain this.

Perhaps the most problematic pesticides are the halogenated hydrocarbons such as DDE, PCB, PCP, dieldrin, and chlordane. These chemicals persist almost indefinitely in the environment. For example, a similar pesticide, DDT, has been banned for nearly 30 years, yet it can still be found in the soil and root vegetables such as carrots and potatoes. Our bodies have a tough time detoxifying and eliminating these compounds. Instead, they end up being stored in our fat cells. What’s more, inside the body these chemicals can act like the hormone estrogen. They are thus suspected as a major cause of the growing epidemic of estrogen-related health problems, including breast cancer.13 Some evidence also suggests that that these chemicals increase the risk of lymphomas, leukemia, and pancreatic cancer, as well as play a role in low sperm count and reduced fertility in men.14

Avoiding pesticides is especially important for children of preschool age. Children are at greater risk for two reasons: they eat more food relative to body mass, and they consume more foods higher in pesticide residues, such as juices, fresh fruits, and vegetables. A recent University of Washington study that analyzed levels of breakdown products of organophosphorus pesticides (a class of insecticides that disrupt the nervous system) in the urine of 39 urban and suburban children two to four years old found that concentrations of pesticide metabolites were six times lower in the children who ate organic fruits and vegetables than in those who ate conventional produce.15

After conducting an analysis of USDA pesticide residue data for all pesticides for 1999 and 2000, Consumers Union warned parents of small children to limit or avoid conventionally grown foods known to have high pesticide residues, such as cantaloupe, green beans (canned or frozen), pears, strawberries, tomatoes (Mexican-grown), and winter squash.16 The University of Washington study added apples to this list.

Unfortunately, not only pesticides have entered our food supply. The EPA now maintains a list of the levels of herbicides, toxic metals (arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury), and even radionuclides in the foods we eat. It is beyond the scope of this book to address all of these. The bottom line is that just like pesticides, all these toxins increase our risk of almost every disease.

How to Avoid Toxins in the Diet

• Do not overconsume foods that have a tendency to concentrate pesticides, such as animal fat, meat, eggs, cheese, and milk.

• Buy organic produce, which is grown without the aid of synthetic pesticides and fertilizers. Although less than 3% of the total produce in the United States is grown without pesticides, organic produce is widely available.

• Develop a good relationship with your local grocery store produce manager. Explain your desire to reduce your exposure to pesticides, heavy metals, and waxes. Ask what measures the store takes to ensure that toxin residues are within approved limits. Ask where the store obtains its produce; make sure the store is aware that foreign produce is much more likely to contain excessive levels of pesticides as well as pesticides that have been banned in the United States.

• Try to buy local produce in season.

• Peeling off the skin or removing the outer layer of leaves of some produce may be all you need to do reduce pesticide levels. The downside is that many of the nutritional benefits of fruits and vegetables are concentrated in the skin and outer layers. An alternative measure is to remove surface pesticide residues, waxes, fungicides, and fertilizers by soaking the item in a mild solution of additive-free soap such as Ivory or pure castile soap. All-natural, biodegradable vegetable cleansers are also available at most health food stores. To use, spray the food with the cleanser, gently scrub, and rinse.

• Eat smaller, wild-caught fish rich in omega-3 fatty acids and avoid eating larger species and farmed fish with the exception of tilapia. Best choices are sardines, anchovies, small mackerel, salmon, and small tuna.

Concentrated sugars, refined grains, and other sources of simple carbohydrates are quickly absorbed into the bloodstream, causing a rapid rise in blood sugar. In response, the body boosts secretion of insulin by the pancreas. High-sugar junk-food diets definitely lead to poor blood sugar regulation, obesity, and ultimately type 2 diabetes and heart disease.17–19 The stress on the body that these diets cause can promote the growth of cancer as well.

As already discussed, the glycemic index of a food refers to how quickly blood sugar levels will rise after it is eaten. However, the GI does not indicate how much carbohydrate is in a typical serving of a particular food, so another tool is needed. The glycemic load (GL) is a way to assess the effect of carbohydrate consumption that takes the GI into account but gives a fuller picture of the effect that a food has on blood sugar levels. A GL of 20 or more is high, a GL of 11 to 19 inclusive is medium, and a GL of 10 or less is low. For example, beets have a high GI but a low GL. Although the carbohydrate in beets has a high GI, the amount of carbohydrate is low, so a typical serving of cooked beets has a relatively low GI (about 5). Thus, as long as you eat a reasonable portion of a low-GL food, the impact on blood sugar is acceptable and the food will not cause blood sugar instability. For example, a diabetic can enjoy some watermelon (GI 72) as long as he or she keeps the serving size reasonable; the GL for 120 g watermelon is only 4.

In essence, foods that are mostly water (such as apples and watermelon), fiber (for example, beets and carrots), or air (such as popcorn) will not cause a steep rise in blood sugar even if their GIs are high as long as portion sizes are moderate. To help you design a healthful diet, we provide a list of the GI, fiber content, and GL of common foods in Appendix B.

Considerable evidence indicates that a high intake of red or processed meat increases the risk of an early death. For example, in a cohort study of half a million people age 50 to 71 at the start of the study, men and women who ate the most red and processed meat had an elevated risk for overall mortality compared with those who ate the least.20

Study after study seems to indicate that the higher the intake of meat and other animal products, the higher the risk of heart disease and cancer, especially cancers of the colon, breast, prostate, and lung, whereas a diet focusing on plant foods has the opposite effect.21,22

There are many reasons for this association. Meat lacks the antioxidants and phytochemicals that protect against cancer. At the same time, it contains lots of saturated fat and other potentially carcinogenic compounds, including pesticide residues, heterocyclic amines, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, the last two of which form when meat is cooked at high temperatures (grilled, fried, or broiled). The more well-done the meat, the higher level of amines as well.23

Some proponents of a diet high in meats claim that people should eat the way their “caveman” ancestors did. That argument does not really hold up. As already discussed, the meat of wild animals that early humans consumed had a fat content of less than 4%. The demand for tender meat has led to the breeding of cattle whose meat contains 25 to 30% or more fat. Corn-fed domestic beef contains primarily saturated fats and virtually no beneficial omega-3 fatty acids (discussed later), whereas the fat of wild animals contains more than five times the polyunsaturated fat per gram and has substantial amounts (about 4–8%) of omega-3 fatty acids.

Particularly harmful to human health are cured or smoked meats, such as ham, hot dogs, bacon, and jerky, that contain sodium nitrate and/or sodium nitrite—compounds that keep the food from spoiling but dramatically raise the risk of cancer. These chemicals react with amino acids in foods in the stomach to form highly carcinogenic compounds known as nitrosamines.

Research in adults makes a convincing argument for avoiding these foods. Even more compelling is the evidence linking consumption of nitrates to a significantly increased risk of the major childhood cancers (leukemias, lymphomas, and brain cancers):

• Children who eat 12 hot dogs per month have nearly 10 times the risk of leukemia compared with children who do not eat hot dogs.24

• Children who eat hot dogs once a week double their chances of brain tumors; eating hot dogs twice a week triples the risk.24

• Pregnant women who eat two servings per day of any cured meat have more than double the risk of bearing children who will eventually develop brain cancer.25

• Kids who eat the most ham, bacon, and sausage have three times the risk of lymphoma.24

In addition, kids who eat ground meat once a week have twice the risk of acute lymphocytic leukemia compared with those who eat none; eating two or more hamburgers weekly triples the risk.24

Healthier Food Choices |

|

REDUCE YOUR INTAKE OF: |

SUBSTITUTE: |

Red meat |

Fish and white meat or poultry |

Hamburgers and hot dogs |

Soy-based or vegetarian alternatives |

Eggs |

Egg Beaters and similar reduced-cholesterol products |

Tofu |

|

High-fat dairy products |

Low-fat or nonfat products |

Butter, lard, other saturated fats |

Olive oil |

Ice cream, pies, cake, cookies, etc. |

Fruits |

Fried foods, fatty snacks |

Vegetables, fresh salads |

Salt and salty foods |

Low-sodium foods, salt substitute |

Coffee, soft drinks |

Herbal teas, green tea, fresh fruit and vegetable juices |

Margarine, shortening, and other source of trans-fatty acids or partially hydrogenated oils |

Olive, macadamia nut, or coconut oil; vegetable spreads that contain no trans-fatty acids (available at most health food stores) |

Fortunately, vegetarian alternatives to these standard components of the American diet are now widely available, and many of them actually taste quite good. Consumers can find soy hot dogs, soy sausage, soy bacon, and even soy pastrami at their local health food stores as well as in many mainstream grocery stores. Those who must have red meat are encouraged to eat only lean cuts of meat, preferably from animals raised on grass rather than corn or soy.

There is no longer any debate: the evidence is overwhelming that a diet high in fat, particularly saturated fat, trans fatty acids, and cholesterol, is linked to heart disease and numerous cancers. Both the American Cancer Society and the National Cancer Institute recommend a diet that supplies less than 30% of calories as fat. However, just as important as the amount of fat is the type of fat consumed. The goal is to decrease total fat intake (especially intake of saturated fats, trans-fatty acids, and omega-6 fats) while increasing intake of omega-3 fatty acids and monounsaturated fatty acids.

What makes a fat “bad” or “good” has a lot to do with the function of fats in the body. Cellular membranes are made mostly of fatty acids. The type of fat consumed determines the type of fatty acid present in the cell membrane. A diet high in saturated fat (primarily from animal fats), trans-fatty acids (from margarine, shortening, and other products that contain hydrogenated vegetable oils), and cholesterol results in unhealthy cell membranes. Without a healthy membrane, cells lose their ability to hold water, vital nutrients, and electrolytes. They also lose their ability to communicate with other cells and to be controlled by regulating hormones, including insulin. Without the right type of fats in cell membranes, cells simply do not function properly. Considerable evidence indicates that cell membrane dysfunction is a critical factor in the development of many diseases.26–29

One diet that provides an optimal intake of the right types of fat is the traditional Mediterranean diet—food patterns typical of some Mediterranean regions in the early 1960s, such as Crete, parts of the rest of Greece, and southern Italy. The traditional Mediterranean diet has shown tremendous benefit in preventing and even reversing heart disease and cancer as well as diabetes.30 It has the following characteristics:

• Olive oil is the principal source of fat.

• It features an abundance of plant-based foods (fruit, vegetables, breads, pasta, potatoes, beans, nuts, and seeds).

• Foods are minimally processed, and there is a focus on seasonal and locally grown foods.

• Fresh fruit is the typical everyday dessert, sweets containing concentrated sugars or honey being consumed a few times per week at most.

• Dairy products (principally cheese and yogurt) are consumed in low to moderate amounts.

• Fish is consumed on a regular basis.

• Poultry and eggs are consumed in moderate amounts (1–4 times weekly) or not at all.

• Red meat is consumed in low amounts.

• Wine is consumed in low to moderate amounts, normally with meals.

Olive oil contains not only the monounsaturated fatty acid oleic acid but also several antioxidant agents that may account for some of its health benefits. Olive oil is particularly valued for its protection against heart disease. It lowers the harmful low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and increases the level of protective high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. It also helps prevent circulating LDL cholesterol from becoming damaged by free radicals, and it has been proved to help control the elevated blood triglycerides so common in diabetes.30

Electrolytes—potassium, sodium, chloride, calcium, and magnesium—are mineral salts that can conduct electricity when dissolved in water. For optimal health, it is important to consume these nutrients in the proper balance. For example, too much sodium in the diet from salt can disrupt this balance. Many people know that a high-sodium, low-potassium diet can cause high blood pressure and that the opposite can lower blood pressure,31,32 but not as many are aware that the former diet also raises the risk of cancer.33

In the United States, only 5% of sodium intake comes from the natural ingredients in food. Prepared foods contribute 45% of our sodium intake; 45% is added in cooking, and another 5% is added at the table. You can reduce your salt intake by following these tips:

• Take the salt shaker off the table.

• Omit added salt from recipes and food preparation.

• If you absolutely must have the taste of salt, try salt substitutes such as No Salt and Nu-Salt. These products are made with potassium chloride and taste very similar to regular salt (sodium chloride).

• Learn to enjoy the flavors of unsalted foods.

• Try flavoring foods with herbs, spices, and lemon juice.

• Read food labels carefully to determine the amounts of sodium. Learn to recognize ingredients that contain sodium. Salt, soy sauce, salt brine, baking soda (sodium bicarbonate), and any ingredient with sodium in its name (such as monosodium glutamate) contain sodium.

• In reading labels and menus, look for words that often signal high sodium content, such as smoked, barbecued, pickled, broth, soy sauce, teriyaki, Creole sauce, marinated, cocktail sauce, tomato base, Parmesan, and mustard sauce.

• Do not eat canned vegetables or soups, which are often extremely high in sodium.

• Choose low-salt (reduced-sodium) products when available.

Most Americans’ diets have a potassium-to-sodium (K:Na) ratio of less than 1:2. In other words, they ingest twice as much sodium as potassium. But experts believe that the optimal dietary K:Na ratio is greater than 5:1, which means we should be getting about ten times more potassium than we currently do. However, even this may not be optimal. A natural diet rich in fruits and vegetables can easily produce much higher K:Na ratios, because most fruits and vegetables have a K:Na ratio of at least 50:1. The average K:Na ratios for several common fresh fruits and vegetables are as follows:

Carrots |

75:1 |

Potatoes |

110:1 |

Apples |

90:1 |

Bananas |

440:1 |

Oranges |

260:1 |

Food additives are used to prevent spoiling, add color, or enhance flavor; they include such substances as preservatives, artificial flavorings, and acidifiers. Although the government has banned many synthetic food additives, it should not be assumed that all the additives currently used in the U.S. food supply are safe. A great number of food additives remain in use that are being linked to such diseases as depression, asthma or other allergy, hyperactivity or learning disabilities in children, and migraine headaches.34–37

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the use of more than 2,000 different food additives. It is estimated that the per capita daily consumption of these food additives is approximately 13 to 15 g, with the result that each of us takes in an astounding 10 to 12 lb of these chemicals every year. This leads to many questions: Which food additives are safe? Which should be avoided? An extremist might argue that no food additive is safe. However, many food additives fulfill important functions in the modern food supply. And while some are synthetic compounds with known cancer-causing effects, many substances approved as additives are natural in origin and possess health-promoting properties. Obviously, the most sensible approach is to focus on whole, natural foods and avoid foods that are highly processed.

An illustration of the problem with food additives involves one of the most widely used synthetic food colors, FD&C yellow no. 5, or tartrazine. Tartrazine is added to almost every packaged food as well as to many drugs, including some antihistamines, antibiotics, steroids, and sedatives. In the United States, the average daily per capita consumption of certified dyes is 40 mg, of which 25 to 40% is tartrazine; among children, consumption is usually much higher.

Although the overall rate of allergic reactions to tartrazine is quite low in the general population, such reactions are extremely common (20 to 50%) in individuals sensitive to aspirin as well as in other allergic individuals. Like aspirin, tartrazine is a known inducer of asthma, hives, and other allergic conditions, particularly in children. In addition, tartrazine, as well as benzoate (a preservative) and aspirin, increases the production of a compound that raises the number of mast cells in the body. Mast cells are involved in producing histamine and other allergic compounds. A person with more mast cells in the body is typically more prone to allergies. For example, more than 95% of patients with hives have a higher than normal number of mast cells.

In studies using provocation tests in patients with hives, the proportion of those with sensitivities to tartrazine and other food additives has ranged from 5 to 46%. Diets eliminating tartrazine as well as other food additives have in many cases been shown to be of great benefit to patients with hives and other allergic conditions, such as asthma and eczema.

Foodborne illness is caused by consumption of contaminated foods or beverages. Although the food supply in the United States is one of the safest in the world, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 76 million people get sick in the United States each year from foodborne illness; more than 300,000 are hospitalized, and 5,000 die.38 The microbe or toxin enters the body through the gastrointestinal tract and often causes the first symptoms there, so nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea are common symptoms in many foodborne diseases. Most cases of foodborne illness are mild, but serious diarrheal disease or other complications may occur.

More than 250 different organisms have been documented as being capable of causing foodborne illness.39 Most of these cases are infections by a variety of bacteria, viruses, and parasites, but poisonings can also occur as a result of ingestion of harmful toxins from organisms that have contaminated the food; for example, botulism occurs when the bacterium Clostridium botulinum grows and produces a powerful paralytic toxin in foods. The botulism toxin can produce illness even if the bacteria are no longer present.

Most of the common causes of foodborne infections are microorganisms frequently present in the intestinal tracts of healthy animals. Meat and poultry can become contaminated during slaughter by contact with small amounts of intestinal contents, and fresh fruits and vegetables can be contaminated if they are washed or irrigated with water that is tainted with animal manure or human sewage.

The most common causes of foodborne infections are the bacteria Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Escherichia coli species O157:H7 and a group of viruses called caliciviruses, also known as the Norwalk and Norwalk-like viruses. Undercooked meat and poultry, raw eggs, unpasteurized milk, and raw shellfish are the most common sources of these organisms.

The foremost measure to reduce the risk of foodborne illness is to cook meat, poultry, and eggs thoroughly. Using a thermometer to measure the internal temperature of meat is a good way to be sure that it is cooked sufficiently to kill bacteria. For example, ground beef should be cooked to an internal temperature of 160°F, poultry should reach a temperature of 185°F, and an egg should be cooked until the yolk is firm.

Also take care to avoid contaminating foods by making sure to wash hands, utensils, and cutting boards after they have been in contact with raw meat or poultry and before they touch another food. Cooked meat should be served on a clean platter, rather than put back on the one that held the raw meat. Wash fresh fruits and vegetables in running tap water. A soft-bristle brush with a little mild soap can be used. Greens can be swished in cold water as many times as needed to get them clean.

Water is essential for life. The average amount of water in the human body is about 10 gallons. We recommend that you drink at least 48 fl oz water per day to replace the water that is lost through urination, sweat, and breathing. Even mild dehydration impairs physiological and performance responses.40 Many nutrients dissolve in water so they can be absorbed more easily in the digestive tract. Similarly, many metabolic processes need to occur in water. Water is a component of blood and thus is important for transporting chemicals and nutrients to cells and tissues and removing waste products. Each cell is constantly bathed in a watery fluid. Water absorbs and transports heat. For example, heat produced by muscle cells during exercise is carried by water in the blood to the surface, helping to maintain the right temperature balance. The skin cells also release water as perspiration, which helps maintain body temperature.

Several factors are thought to increase the likelihood of chronic mild dehydration: a faulty thirst “alarm” in the brain; dissatisfaction with the taste of water; regular exercise that increases the amount of water lost through sweat; living in a hot, dry climate; and consumption of caffeine and alcohol, both of which have a diuretic effect.

There is currently great concern over the U.S. water supply. It is becoming increasingly difficult to find pure water. Most of the water supply is full of chemicals, including not only chlorine and fluoride, which are routinely added, but also a wide range of toxic organic compounds and chemicals, such as PCBs, pesticide residues, and nitrates, and heavy metals such as lead, mercury, and cadmium. It is estimated that lead alone may contaminate the water of more than 40 million Americans. You can determine the safety of your tap or well water by contacting your local water company; most cities have quality assurance programs that perform routine analyses.

Nutritional Supplementation

Nutritional supplementation—the use of vitamins, minerals, and other food factors to support good health as well as to prevent or treat illness—is an important component of nutritional medicine. The key functions of nutrients such as vitamins and minerals in the human body revolve around their role as essential components in enzymes and coenzymes. One of the key concepts in nutritional medicine is to supply the necessary support or nutrients to allow the enzymes of a particular tissue to work at optimal levels. The concept of “biochemical individuality” was developed by nutritional biochemist Roger Williams in the 1970s to recognize the wide range in humans’ enzymatic activity and nutritional needs. These observations also provided the basis for orthomolecular medicine, as envisioned by two-time Nobel laureate Linus Pauling who coined the term to mean “the right molecules in the right amounts” (ortho is Greek for “right”). Orthomolecular medicine seeks to maintain health and prevent or treat diseases by optimizing nutritional intake and/or prescribing supplements.

In addition to serving as necessary components in enzymes and coenzymes, many nutrients seem to exert pharmacologic effects. Most of these effects appear to be the result of enzyme induction or inhibition. In other words, when used at levels above those required for normal physiology, nutrients can induce the manufacture of enzymes, induce enzymes to become more active, or even inhibit enzyme action. For example, the B vitamin niacin (nicotinic acid) is well known as a lipid-lowering agent when given at high dosages (2–6 g per day in divided doses). Its mechanism of action appears to be inhibition of enzymes that manufacture very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) while stimulating the production or activity of enzymes that take up LDL in the liver. The advantage of using nutrients at pharmacological dosages is that they are more recognizable to the body and better metabolized than synthetic drugs, as evidenced by a better safety profile. Even so, the use of nutrients as pharmacological agents is closely akin to drug therapy. That being the case, it is imperative that they be used and monitored appropriately.

QUICK REVIEW

Follow these guidelines:

1. Eat a “rainbow” assortment of fruits and vegetables.

2. Reduce exposure to pesticides, heavy metals, and food additives.

3. Eat to support blood sugar control.

4. Do not overconsume animal foods.

5. Eat the right types of fats.

6. Keep salt intake low, potassium intake high.

7. Reduce exposure to pesticides, heavy metals, and food additives.

8. Take measures to reduce foodborne illnesses.

9. Drink sufficient amounts of water each day.

The dietary guidelines and principles that are detailed in this chapter represent our answer to the hotly debated question “What is the best diet?” After a review of every popular diet in detail as well as thousands of scientific articles on the role of diet in human health, our offering here is based on the evolutionary understanding of what constitutes the optimal diet. The bottom line for a health-promoting diet is to reduce the intake of potentially harmful substances—foods laden with empty calories, additives, and artificial sweeteners—and replace them with natural foods, preferably organically grown.