Introduction

Each year obesity-related conditions cost over $100 billion and cause an estimated 300,000 premature deaths in the United States, making a very strong case that the obesity epidemic is the most significant threat to the future of this country as well as other nations. In 1962, 13% of Americans were obese. By 1980 the proportion had risen to 15% and by 1994 it was up to 23%, and by the year 2004 obesity in America had reached a rate of one out of three, or 33%. Approximately 65 million adult Americans are now obese—more than the population of Britain, France, or Italy. As alarming as these statistics are, it must be pointed out that there is no end in sight. In particular, the percentage of children who are obese is also rising at an alarming rate. It is now estimated that 16.9% of children and adolescents from 2 to 19 years old are obese. Given the health challenges associated with obesity, the significance of these increases is staggering.1–5

Obesity and Health

Can you be both fat and healthy? No. According to detailed studies, obesity is more damaging to health than smoking, high levels of alcohol consumption, or poverty.4,5 Obesity affects all major bodily systems—heart, lung, muscles, and bones. The health effects associated with obesity include, but are not limited to, the following:

• High blood pressure. Additional fat tissue in the body needs oxygen and nutrients in order to live, and therefore the blood vessels must circulate more blood to the fat tissue. This increases the workload of the heart because it must pump more blood through additional blood vessels. More circulating blood also means more pressure on the artery walls. Higher pressure on the artery walls increases blood pressure. In addition, extra weight can raise the heart rate and reduce the body’s ability to transport blood through the vessels.

• Diabetes. Obesity, particularly abdominal obesity, is the major cause of type 2 diabetes. Obesity can cause resistance to insulin, the hormone that regulates blood sugar. When obesity causes insulin resistance, the body’s blood sugar levels becomes elevated. Even moderate obesity dramatically increases the risk of diabetes.

• Heart disease. Atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries) is present 10 times more often in obese people compared with those who are not obese. Coronary artery disease is also more prevalent because fatty deposits build up in arteries that supply the heart. Narrowed arteries and reduced blood flow to the heart can cause chest pain (angina) or a heart attack. Blood clots can also form in narrowed arteries and cause a stroke.

• Cancer. In women, being overweight contributes to an increased risk for a variety of cancers, including those of the breast, colon, gallbladder, and uterus. Men who are overweight have a higher risk of colon and prostate cancers.

• Joint problems, including osteoarthritis. Obesity can affect the knees and hips because of the stress placed on the joints by extra weight. Joint replacement surgery, while commonly performed on damaged joints, may not be advisable for an obese person because the artificial joint has a higher risk of loosening and causing further damage.

• Sleep apnea and respiratory problems. Sleep apnea, which causes people to stop breathing for brief periods, interrupts sleep throughout the night; the result is sleepiness during the day. It also causes heavy snoring. Respiratory problems associated with obesity occur when the added weight of the chest wall squeezes the lungs and causes restricted breathing. Sleep apnea is also associated with high blood pressure.

• Psychosocial effects. In a culture where often the ideal of physical attractiveness is to be overly thin, people who are overweight or obese frequently suffer disadvantages. Overweight and obese individuals are often blamed for their condition and may be considered lazy or weak-willed. It is not uncommon for overweight or obese people to have lower incomes or fewer or no romantic relationships. Disapproval of overweight people expressed by some individuals may progress to bias, discrimination, and even torment.

Obese individuals have a life expectancy that is on average five to seven years shorter compared with normal-weight individuals, with greater obesity associated with a greater relative risk for early mortality.4,5 Most of the increased risk for early mortality is due to cardiovascular disease, as obesity carries with it a tremendous risk for type 2 diabetes, elevated cholesterol levels, high blood pressure, and other factors contributing to atherosclerosis. In 2009 annual medical spending due to overweight and obesity was estimated to be $147 billion.6

Health Problems Resulting from Obesity

• Cardiovascular problems

![]() Angina

Angina

![]() Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis

![]() Congestive heart failure

Congestive heart failure

![]() Deep vein thrombosis

Deep vein thrombosis

![]() Heart attack

Heart attack

![]() High blood pressure

High blood pressure

![]() High cholesterol levels

High cholesterol levels

![]() Pulmonary embolism

Pulmonary embolism

![]() Stroke

Stroke

• Skin problems

![]() Cellulitis

Cellulitis

![]() Hirsutism

Hirsutism

![]() Intertrigo

Intertrigo

![]() Lymphedema

Lymphedema

![]() Stretch marks

Stretch marks

• Endocrine and reproductive problems

![]() Complications during pregnancy

Complications during pregnancy

![]() Diabetes

Diabetes

![]() Infertility

Infertility

![]() Menstrual disorders

Menstrual disorders

![]() Polycystic ovarian syndrome

Polycystic ovarian syndrome

• Gastrointestinal problems

![]() Gastroesophageal reflux disease

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

![]() Gallstones

Gallstones

![]() Fatty liver disease

Fatty liver disease

• Neurological problems

![]() Carpal tunnel syndrome

Carpal tunnel syndrome

![]() Dementia

Dementia

![]() Idiopathic intracranial hypertension

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension

![]() Migraine headaches

Migraine headaches

![]() Multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis

• Cancer

• Mental health issues

![]() Depression

Depression

![]() Social stigmatization

Social stigmatization

• Respiratory problems

![]() Asthma

Asthma

![]() Obstructive sleep apnea

Obstructive sleep apnea

• Rheumatological and orthopedic problems

![]() Chronic low back pain

Chronic low back pain

![]() Gout

Gout

![]() Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis

• Genital and urinary problems

![]() Chronic renal failure

Chronic renal failure

![]() Erectile dysfunction

Erectile dysfunction

![]() Hypogonadism

Hypogonadism

![]() Urinary incontinence

Urinary incontinence

Obesity Defined

The basic definition of obesity is an excessive amount of body fat. A simple measure known as the body mass index (BMI) is now the accepted standard for classifying individuals with regard to their body composition, and generally correlates well with a person’s total body fat. (This may not be true for some very muscular athletes, whose body weight may place them in the category of overweight even though they have a low percentage of body fat.) BMI is calculated by dividing a person’s weight in kilograms by height in meters squared. On the opposite page is a simple table to use to determine your BMI. To use the table, find your height in the left-hand column. Move across the row to your weight. The number at the top of the column is the BMI for that height and weight.

A BMI of 25 to 29.9 is a marker for being overweight, while someone who has a BMI of 30 or greater is considered obese. To put the BMI into perspective, a 5-foot-4-inch woman with a BMI of 30 is about 30 pounds above her ideal body weight. So obesity is not a matter of simply being a few pounds overweight. It reflects a significant amount of excess fat.

There is one more calculation that is important—your waist size. The combination of your BMI and your waist circumference is very good indicator of your risk for all of the diseases associated with obesity, especially the major killers: heart disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes.

Abdominal Obesity

Abdominal obesity is highly associated with metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, elevated inflammatory markers, high cholesterol and/or triglycerides, and high blood pressure. It is much more strongly linked to these issues than body mass index. So it appears that it is not how much you weigh but rather where you store your fat that determines your risk for cardiovascular disease.

Abdominal fat tissue was previously regarded as an inert storage depot; however, the emerging concept describes adipose tissue as a complex and highly active metabolic and endocrine organ. Fat cells secrete hormone-like compounds known as adipokines that control insulin sensitivity and appetite. As abdominal fat accumulates, it leads to alterations in adipokines that ultimately promote insulin resistance and increased appetite, thereby adding more abdominal fat. Fortunately, reduction of abdominal fat through diet and increased physical activity can reestablish insulin sensitivity and reduce appetite.

BMI(KG/M2) |

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

25 |

26 |

27 |

28 |

29 |

30 |

35 |

40 |

Height(inches) |

Weight (pounds) |

|||||||||||||

58 |

91 |

96 |

100 |

105 |

110 |

115 |

119 |

124 |

129 |

134 |

138 |

143 |

167 |

191 |

59 |

94 |

99 |

104 |

109 |

114 |

119 |

124 |

128 |

133 |

138 |

143 |

148 |

173 |

198 |

60 |

97 |

102 |

107 |

112 |

118 |

123 |

128 |

133 |

138 |

143 |

148 |

153 |

179 |

204 |

61 |

100 |

106 |

111 |

116 |

122 |

127 |

132 |

137 |

143 |

148 |

153 |

158 |

185 |

211 |

62 |

104 |

109 |

115 |

120 |

126 |

131 |

136 |

142 |

147 |

153 |

158 |

164 |

191 |

218 |

63 |

107 |

113 |

118 |

124 |

130 |

135 |

141 |

146 |

152 |

158 |

163 |

169 |

197 |

225 |

64 |

110 |

116 |

122 |

128 |

134 |

140 |

145 |

151 |

157 |

163 |

169 |

174 |

204 |

232 |

65 |

114 |

120 |

126 |

132 |

138 |

144 |

150 |

156 |

162 |

168 |

174 |

180 |

210 |

240 |

66 |

118 |

124 |

130 |

136 |

142 |

148 |

155 |

161 |

167 |

173 |

179 |

186 |

216 |

247 |

67 |

121 |

127 |

134 |

140 |

146 |

153 |

159 |

166 |

172 |

178 |

185 |

191 |

223 |

255 |

68 |

125 |

131 |

138 |

144 |

151 |

158 |

164 |

171 |

177 |

184 |

190 |

197 |

230 |

262 |

69 |

128 |

135 |

142 |

149 |

155 |

162 |

169 |

176 |

182 |

189 |

196 |

203 |

236 |

270 |

70 |

132 |

139 |

146 |

153 |

160 |

167 |

174 |

181 |

188 |

195 |

202 |

207 |

243 |

278 |

71 |

136 |

143 |

150 |

157 |

165 |

172 |

179 |

186 |

193 |

200 |

208 |

215 |

250 |

286 |

72 |

140 |

147 |

154 |

162 |

169 |

177 |

184 |

191 |

199 |

206 |

213 |

221 |

258 |

294 |

73 |

144 |

151 |

159 |

166 |

174 |

182 |

189 |

197 |

204 |

212 |

219 |

227 |

265 |

302 |

74 |

148 |

155 |

163 |

171 |

179 |

186 |

194 |

202 |

210 |

218 |

225 |

233 |

272 |

311 |

75 |

152 |

160 |

168 |

176 |

184 |

192 |

200 |

208 |

216 |

224 |

232 |

240 |

279 |

319 |

76 |

156 |

164 |

172 |

180 |

189 |

197 |

205 |

213 |

221 |

230 |

238 |

246 |

287 |

328 |

Risk of Disease According to BMI and Waist Size |

||

BMI |

WAIST SIZE LESS THAN OR EQUAL TO 40 INCHES (MEN) OR 35 INCHES (WOMEN) |

WAIST SIZE GREATER THAN 40 INCHES (MEN) OR 35 INCHES (WOMEN) |

18.5 or less (underweight) |

No increased risk of disease |

No increased risk of disease |

18.5–24.9 (normal weight) |

No increased risk of disease |

No increased risk of disease |

25.0–29.9 (overweight) |

Increased risk of disease |

High risk of disease |

30.0–34.9 (obese) |

High risk of disease |

Very high risk of disease |

35.0–39.9 (obese) |

Very high risk of disease |

Very high risk of disease |

40 or greater (extremely obese) |

Extremely high risk of disease |

Extremely high risk of disease |

To determine your waist circumference, place a measuring tape around the abdomen just above the upper hip bone, ensuring that the tape measure is horizontal. The tape measure should be snug but not tight. If you are a man and your waist circumference is greater than 40 inches, or if you are a woman and your waist circumference is greater than 35 inches, there is no need to do any further calculation, as this measurement alone has been shown to be a major risk factor for both cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. If your waist circumference is less than these values, you need to determine your waist/hip ratio. To do this, measure the circumference of your hips at the widest part. Divide the waist circumference by the hip circumference. A waist/hip ratio above 1.0 for men and above 0.8 for women increases the risk of developing cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and gout.

1. Measure the circumference of your waist: _______

2. Measure the circumference of your hips: _______

3. Divide the waist measurement by the hip measurement: _______ (this is your waist/hip ratio)

Body Fat vs. Body Weight

The number on the scale represents your total weight, not body composition (proportion of fat to muscle). It is increased body fat that is associated with poor health outcomes, not increased body weight. For example, people with a normal BMI can develop type 2 diabetes if they have an increased body fat percentage, especially if that excess fat is collecting around the waist. To more accurately determine body composition, we recommend using a scale that utilizes a safe, very low-level amount of electricity to measure body fat percentage by bioelectrical impedance. Since fat does not conduct much bioelectricity, a higher degree of impedance of the electrical charge is associated with a higher percentage of body fat. The most popular scales of this sort are manufactured by Tanita (www.tanita.com) and range in cost from $55 to $200 depending upon features. Ideally, women should strive to keep their body fat below 25% and men below 20%.

Causes of Obesity

Although there may or may not be a specific “obesity gene,” the tendency to be overweight is definitely inherited. Nonetheless, even high-risk individuals can avoid obesity, and this indicates that dietary and lifestyle factors (primarily little or no physical activity) are chiefly responsible for obesity. In looking at possible causes beyond diet and lifestyle, researchers have focused on both psychological factors and physiological factors.

In the past, psychological factors were thought to be largely responsible for obesity. An early popular theory proposed that overweight individuals were insensitive to internal signals for hunger and satiety while simultaneously being extremely sensitive to external stimuli (sight, smell, and taste) that can increase the appetite. One source of external stimuli that has clearly been shown to be associated with obesity is watching television.

Watching TV has been demonstrated to be linked to the onset of obesity, and there is a dose-related effect. Increased TV viewing and decreased physical activity are thought to be primary causes of the growing number of obese children in the United States. TV viewing in childhood and adolescence is associated not only with being overweight but also with poor fitness and with obesity, smoking, and raised cholesterol levels in adulthood, indicating that excessive viewing has long-lasting adverse effects on health.7

TV viewing also contributes to being overweight in adults. In one study 50,277 women who had a BMI less than 30 completed questions on physical activity. During six years of follow-up, 3,757 (7.5%) became obese (BMI ≥30) and 1,515 new cases of type 2 diabetes occurred. Time spent watching TV was positively associated with risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Each two-hour-per-day increment in TV watching was associated with a 23% increase in obesity and a 14% increase in risk of diabetes. In contrast, each two-hour-per-day increment in sitting at work was associated with a 5% increase in obesity and a 7% increase in diabetes.8

Although watching TV fits nicely with the psychological theory (increased sensitivity to external cues), several physiological effects of watching television promote obesity, such as reducing physical activity and the lowering of basal metabolic rate to a level similar to that experienced during trancelike states. These factors clearly support the physiological view.

Although the psychological theories primarily propose that obese individuals have a decreased sensitivity to internal cues of hunger and satiation, an emerging theory of obesity states almost the opposite: that obese individuals appear to be extremely sensitive to specific internal cues.4 Unfortunately, these cues lead to dysfunctional appetite control, thanks to a combination of genetic, dietary, and lifestyle factors. At the center of this dysfunction in many cases is resistance to the hormone insulin, a conditioned response to a high-glycemic diet. The development, progression, and maintenance of obesity form a vicious circle of positive feedback consisting of insulin resistance, abdominal obesity, alterations in the fat cell hormones known as adipokines, loss of appetite control, impaired diet-induced thermogenesis, and low brain serotonin levels. All of these factors are interrelated and support the theory that obesity is primarily an adaptive response that is out of control. Failure to address these underlying areas and provide proper psychological support results in only temporary weight loss at best.

The Set Point

Body weight is closely tied to what is referred to as the “set point”—the weight that a body tries to maintain by regulating the amount of food and calories consumed. Research with animals and humans has found that each person has a programmed set point weight. It has been postulated that individual fat cells control this set point: when the enlarged fat cells in obese individuals become smaller, they either send powerful messages to the brain to eat or block the action of appetite-suppressing compounds.

The existence of this set point helps to explain why most diets do not work. Although the obese individual can fight off the impulse to eat for a time, eventually the signals become too strong to ignore. The result is rebound overeating, with individuals often exceeding their previous weight. In addition, their set point is now set at a higher level, making it even more difficult to lose weight. This has been termed the “ratchet effect” and “yo-yo dieting.”

The key to overcoming the fat cells’ set point appears to be increasing the sensitivity of the fat cells to insulin. This sensitivity apparently can be improved, and the set point lowered, by exercise, a specially designed diet, and several nutritional supplements (discussed later). The set point theory suggests that a diet that does not improve insulin sensitivity will most likely fail to provide long-term results.

When fat cells, particularly those around the abdomen, become full of fat, they secrete a number of biological products (e.g., resistin, leptin, tumor necrosis factor, and free fatty acids) that dampen the effect of insulin, impair glucose utilization in skeletal muscle, and promote glucose production by the liver. Also important is that as the number and size of fat cells increase, they lead to a reduction in the secretion of compounds that promote insulin action, including adiponectin, a protein produced by fat cells. Not only is adiponectin associated with improved insulin sensitivity, but it also has anti-inflammatory activity, lowers triglycerides, and blocks the development of atherosclerosis. The net effect of all these actions by fat cells is that they severely stress blood sugar control mechanisms, as well as lead to the development of the major complication of diabetes—atherosclerosis. Because of all these newly discovered hormones secreted by fat cells, many experts now consider adipose tissue a member of the endocrine system.9,10

Adipokine and Gut-Derived Hormone Alterations

It could be argued that obese individuals are more sensitive to internal signals to eat. Appetite reflects a complex system that has evolved to help humans deal with food shortages. As a result, it is extremely biased toward weight gain. It makes sense that people who survived famines were those who were more adept at storing fat than burning it. So humans have a built-in tendency to overeat, even though in developed countries food is readily available.

To combat the tendency to eat more than is required, it is important to accentuate the normal physiological processes that curb the appetite. An elaborate system exists that is supposed to tell the hypothalamus when the body requires more food, as well as when enough food has been consumed. Many of these strong signals of appetite control actually originate from the gastrointestinal tract. In addition to nerve signals feeding back to the central nervous system, researchers have identified a growing list of gut-derived hormones and peptides that affect appetite, such as PYY, ghrelin, and cholecystokinin.11,12 While some of these compounds promote feelings of satiety, others cause increased appetite. For example, the stomach-derived hormone ghrelin increases appetite. Ghrelin levels are highest when the stomach is empty and during calorie restriction. Obese individuals tend to have elevated ghrelin levels, and when they try to lose weight, ghrelin levels increase even more. Part of the reason gastric bypass surgery is successful in producing permanent weight loss is thought to be that it significantly reduces ghrelin levels.13

Although using various appetite regulators as therapeutic agents in human obesity is possible, preliminary studies seem to indicate that in humans compensatory actions may negate the effect. The perfect drug or natural product to affect appetite must possess an ability to increase insulin sensitivity and produce a targeted effect of reducing factors that increase appetite while simultaneously increasing factors that decrease appetite. Highly viscous dietary fiber seems ideal for this (a good example, PolyGlycopleX, is discussed below).

Diet-Induced Thermogenesis

Another physiological difference between obese and thin people is how much of the food consumed is converted immediately to heat. This process is known as diet-induced thermogenesis. Researchers have found that in lean individuals a meal may stimulate up to a 40% increase in diet-induced thermogenesis. In contrast, overweight individuals often display an increase of only 10% or less.14 In overweight individuals the food energy is stored instead of being converted to heat as it is in lean individuals.

A major factor for the decreased thermogenesis in overweight people is, once again, insulin insensitivity.15 Therefore enhancing insulin sensitivity may go a long way toward reestablishing normal thermogenesis, as well as resetting the set point in overweight individuals.

Researchers have also shown that even after weight loss has been achieved, individuals predisposed to obesity still have decreased diet-induced thermogenesis compared with lean individuals.16 Therefore it is important to continue to support insulin sensitivity and proper metabolism indefinitely if weight loss is to be maintained.

In addition to insulin insensitivity and reduced sympathetic nervous system activity, another factor determines diet-induced thermogenesis—the amount of brown fat. Most fat in the body is white fat: an energy reserve that contains triglycerides stored in a single compartment. Tissue composed of white fat looks white or pale yellow. Brown fat cells contain multiple fat storage compartments. The triglycerides are localized in smaller droplets surrounding numerous mitochondria. An extensive blood vessel network and the density of the mitochondria give the tissue its brown appearance, as well as its increased capacity to metabolize fatty acids.17

Brown fat does not metabolize fatty acids to chemical energy as efficiently as other tissues of the body, including white fat. This inefficiency results in increased heat production. Brown fat plays a major role in diet-induced thermogenesis.

Some theories suggest that lean people have a higher ratio of brown fat to white fat than overweight individuals. Evidence supports this theory. The amount of brown fat in modern humans is extremely small (estimates are 0.5 to 5% of total body weight), but because of its profound effect on diet-induced thermogenesis, as little as 1 oz brown fat (0.1% of body weight) could make the difference between maintaining body weight and putting on an extra 10 lb/year.17

Lean individuals also tend to respond to excess calories differently from overweight individuals. In one experiment, lean individuals were overfed to increase their weight. In order to maintain the excess weight, they had to increase their caloric intake by 50% over their previous intake.18 The opposite appears to be the case in overweight and formerly overweight individuals. They require fewer calories to gain and maintain their weight; in addition, studies have shown that in order to maintain a reduced weight, formerly obese persons must restrict their food intake to approximately 25% less than a lean person of similar weight and body size.19

Individuals predisposed to obesity because of decreased diet-induced thermogenesis have been shown to be extremely susceptible to significant weight gain when consuming a high-fat diet, compared with lean individuals.20 Not only are these individuals more sensitive to the weight-gain-promoting effects of a high-fat diet, but they tend to consume much more dietary fat than lean individuals and exercise less.

The Low Serotonin Theory

A considerable body of evidence demonstrates that levels of serotonin in the brain play a major role in influencing eating behavior. Initial studies showed that when animals and humans are fed diets deficient in tryptophan, appetite is significantly increased, resulting in binge eating of carbohydrates.21,22 A diet low in tryptophan leads to low brain serotonin levels, a condition the brain interprets as starvation, resulting in the stimulation of the appetite control centers. This stimulation results in a preference for carbohydrates. Feeding animals or humans a carbohydrate meal leads to increased tryptophan delivery to the brain, resulting in the elevated manufacture of serotonin. This scenario has led to the idea that low serotonin levels contribute to carbohydrate cravings and play a major role in the development of obesity.

Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that concentrations of tryptophan in the bloodstream and subsequent brain serotonin levels plummet with dieting.23 In response to severe drops in serotonin levels, the brain simply puts out such a strong message to eat that it cannot be ignored. This explains why most diets do not work.

Cravings for carbohydrates due to low serotonin levels can be mild or quite severe. They may range in severity from the desire to nibble on a piece of bread or a cookie to uncontrollable binging. At the upper end of the spectrum of carbohydrate addiction is bulimia, a potentially serious eating disorder characterized by binge eating and purging of the food through forced vomiting or the use of laxatives. The medical consequences of bulimia can be quite severe (e.g., rupture of the stomach, erosion of the dental enamel, and heart disturbances due to loss of potassium).

Therapeutic Considerations

Long-term control of obesity is one of the greatest clinical challenges. Few people want to be overweight, and most overweight people express a strong desire to lose weight, yet only 5% of obese individuals can attain and maintain normal body weight for a year or more, while 66% of those just a few pounds or so overweight are able to do the same.

The successful program for obesity is consistent with the basic foundations of good health—a positive mental attitude, a healthful lifestyle (especially important is regular exercise), a health-promoting diet, and supplementary measures. All of these components are interrelated, creating a situation in which no single component is more important than the others. Improvement in one facet may be enough to result in some positive changes, but incorporating all components yields the greatest results.

Literally hundreds of diets and diet programs claim to be the answer to the problem of obesity. Dieters are constantly bombarded with new reports of yet another “wonder” diet. However, the basic calculation for losing weight never changes. In order for an individual to lose weight, energy intake must be less than energy expenditure. This goal can be achieved by decreasing caloric intake or by increasing the rate at which calories are metabolized; the best results are achieved by doing both.

To lose 1 pound, a person must consume 3,500 fewer calories than he or she expends. The loss of 1 lb each week requires a negative caloric balance of 500 calories a day. This can be achieved by decreasing the amount of calories ingested or by increasing exercise. Reducing a person’s caloric intake by 500 calories is often difficult, as is increasing metabolism by an additional 500 calories a day through exercise (accomplished by a 45-minute jog, playing tennis for an hour, or a brisk walk for 1.25 hours). The most sensible approach to weight loss is to both decrease caloric intake and increase energy expenditure through exercise.

Most individuals begin to lose weight if they decrease their caloric intake below 1,500 calories a day and exercise for 15 to 20 minutes three to four times per week. Starvation and crash diets usually result in rapid weight loss (largely of muscle and water) but cause rebound weight gain. The most successful approach to long-term, sustainable weight loss is gradual weight reduction (0.5 to 1 lb per week) through adopting long-term dietary and lifestyle habits that promote health and the attainment and maintenance of ideal body weight. Exercise is critical to maintaining muscle mass and bone mineral density and to preventing the accumulation of abdominal fat, both during active weight loss and after weight loss has been achieved.24,25

Although many obese individuals may need to lose considerable weight to achieve their long-term goals, it is important to stress that even modest reductions in body weight can produce significant health benefits. For example, a 5 to 10% reduction in weight is accompanied by clinically meaningful improvements in cholesterol, blood pressure, and blood glucose levels.

Although clinical studies indicate that behavioral approaches to the management of obesity are often successful in achieving clinically significant weight loss, the lost weight is generally regained. The great majority of patients return to their pretreatment weight within three years. In order to provide the best insights on effective interventions, it is important to examine the psychological characteristics of people who have lost significant amounts of weight and experienced only minimal weight regain.26 Six main behavioral characteristics have been identified in individuals who avoid significant weight regain:

• Maintaining high levels of physical activity (approximately one hour a day)

• Eating a low-calorie, low-fat, low-glycemic diet

• Eating breakfast regularly

• Self-monitoring weight

• Maintaining a consistent eating pattern across weekdays and weekends

• Avoiding depression

These characteristics are intertwined within a whole host of additional factors that provide necessary leverage for successful weight loss. For example, most obese patients who see a doctor about weight loss want to lose 20 to 30% of their body weight. Because most people lose only modest amounts of weight, many quickly lose the motivation and determination to keep the weight off. However, if people feel a significant boost to self-esteem and self-confidence, as well as have the experience of improving their appearance, feeling more attractive, and being able to wear more fashionable clothing, it can provide tremendous impetus for continued weight loss until goals are achieved.

Remember that the majority of people want to lose weight for the changes in their physical appearance, not the health benefits. Although there is widespread awareness that being overweight is associated with increased health risks, relatively few patients give this as their reason for seeking treatment. Identifying patients’ primary goals for losing weight is a key step in helping them achieve success.

The dietary strategy that we recommend for obesity is the one given in the chapter “A Health-Promoting Diet.” The principles and goals detailed there reinforce some of the key goals in achieving weight loss and maintaining ideal body weight. It is important to stress the importance of adequate protein consumption. We recommend 2 g protein daily per kg of body weight unless a person is showing signs of kidney failure.

The importance of higher protein consumption was demonstrated in the Diogenes Study (Diogenes is an acronym for “Diet, Obesity, and Genes”). The five-year program involved 29 world-class centers in diet and health studies, epidemiology, dietary genomics, and food technology across Europe. More than 700 overweight adults from eight European countries who had lost at least 8% of their initial body weight with an 800-calorie diet (mean initial weight loss was 24.2 lb) were randomly assigned to one of five diets to prevent weight regain: a low-protein and low-glycemic diet, a low-protein and high-glycemic diet, a high-protein and low-glycemic diet, a high-protein and high-glycemic diet, or a control diet. The participants were to stay on the diet for 26 weeks, and the amount they could eat was not controlled. Fewer participants dropped out in the high-protein/high glycemic and high-protein/low-glycemic groups than in the low-protein/high-glycemic group (26.4% and 25.6%, respectively, vs. 37.4%). Among participants who completed the study, only the low-protein/high-glycemic diet was associated with subsequent significant weight regain (3.7 lbs). The weight regain was 2.0 lb less in the groups assigned to a high-protein diet than in those assigned to a low-protein diet and 2.1 lb less in the groups assigned to a low-glycemic-index diet than in those assigned to a high-glycemic-index diet. The groups did not differ significantly with respect to diet-related adverse events.27

Water Consumption

It is well established that water consumption can acutely reduce the amount of calories eaten during a meal, especially among middle-aged and older adults. In the most recent study, 48 adults ages 55 to 75 with a BMI of 25 to 40 were assigned to one of two groups: (1) a low-calorie diet plus 500 ml water prior to each meal (water group), or (2) a low-calorie diet alone (non-water group). Weight loss was about 4.4 lb greater in the water group than in the non-water group, and the water group showed a 44% greater decline in weight over the 12 weeks than the non-water group.28

The Atkins Diet

Although hundreds of fad diets have been promoted over the years, we would be remiss if we did not mention the most famous weight loss diet of all time, the Atkins Diet. This high-protein, high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet was developed by Robert Atkins, M.D., during the 1960s. In the early 1990s Dr. Atkins brought his diet back into the nutrition spotlight with the publication of his best-selling book Dr. Atkins’ New Diet Revolution. An estimated 50 million people worldwide have tried the Atkins Diet, which emphasizes the consumption of protein and fat. Individuals following the Atkins Diet are permitted to eat unlimited amounts of all meats, poultry, fish, and eggs, plus most cheeses.

The Atkins Diet is divided into four phases: induction, ongoing weight loss, pre-maintenance, and maintenance. During the induction phase (the first 14 days of the diet), carbohydrate intake is limited to no more than 20 g per day. No fruit, bread, grains, starchy vegetables, or dairy products except cheese, cream, and butter are allowed during this phase. During the ongoing weight loss phase, dieters experiment with various levels of carbohydrate consumption until they determine the most liberal level of carbohydrate intake that allows them to continue to lose weight. Dieters are encouraged to maintain this level of carbohydrate intake until their weight loss goals are met. Then, during the pre-maintenance and maintenance phases, dieters determine the level of carbohydrate consumption that allows them to maintain their weight. To prevent regaining weight, dieters must stick to this level of carbohydrate consumption, perhaps for the rest of their lives.

Although we agree with the underlying principle of the Atkins Diet, that diets high in sugar and refined carbohydrates cause weight gain and ultimately lead to obesity, we disagree with several aspects of the solution. One of the big reasons why the Atkins Diet is so attractive to dieters who have tried unsuccessfully to lose weight on low-fat, low-calorie diets is that while on the Atkins Diet, they can eat as many calories as desired from protein and fat, as long as carbohydrate consumption is restricted. As a result, many Atkins dieters are spared the feelings of hunger and deprivation that accompany other weight loss regimens. However, we simply do not agree that such a diet is conducive to long-term health.

Despite its enormous popularity, the Atkins program was not evaluated in a proper clinical trial until 2003. In this initial study, although people following the Atkins Diet did experience initial weight loss (probably as a result of water loss rather than true fat loss), in the long run they gained it all back plus more. In the study, 63 obese men and women were randomly assigned to the Atkins Diet or a low-calorie, high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet. Professional contact was minimal to replicate the approach used by most dieters. Although at 6 months subjects on the Atkins Diet had lost more weight than subjects on the conventional diet, the difference at 12 months was not significant. Adherence was poor, and attrition was high in both groups.29

Since this initial clinical evaluation, other studies have shown similar results. For example, in one study of 34 adults with impaired glucose tolerance, 12 weeks of a low-fat (18% of total calories), high-complex-carbohydrate (62% of total calories) diet alone (high-CHO) or paired with an aerobic exercise training program (high-CHO-ex) was compared with the effects of an Atkins-style diet (41% fat, 14% protein, 45% carbohydrate). Fiber intake averaged 58 to 61 g per day in the two high-carbohydrate groups vs. 18.5 g per day in the control group. Participants engaged in aerobic exercise for 45 minutes per day, four days per week, at 80% of peak oxygen consumption in the high-CHO-ex group. All participants were instructed not to limit their food intake. Although caloric intake was similar in all three groups, both high-CHO groups (with and without exercise) lost more weight (mean loss was 10.5 lb with exercise and 7 lb without exercise) than the control group (mean loss was a fraction of 1 lb). Similarly, a higher percentage of body fat was lost by the high-CHO-ex group (3.5%) and the high-CHO without exercise group (2.2%) than by controls (0.2% increase in body fat). Thigh fat area also decreased significantly in both high-CHO groups but not in the control group. Resting metabolic rate and rate of fat oxidation were not decreased in the high-CHO (or control) groups.30

In another study, 132 obese adults (BMI >35), of whom 83% had type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome, were counseled to consume either an Atkins-like diet limited to less than 30 g carbohydrates per day or a diet restricted by 500 calories per day with less than 30% of calories from fat. Although the Atkins Diet did promote weight loss during the first 6-month period, this effect began to disappear during the second 6-month period. At 12 months, the difference in average weight loss in the groups was no longer statistically significant (11 lb in the Atkins group vs. 7 lb in the low-fat group), though changes in triglyceride levels favored the Atkins Diet (–57 mg/dl vs. –4 mg/dl), as did HgA1c reductions (–0.7 vs. –0.1%) in the patients with type 2 diabetes.31

Another study worth commenting on was funded by the Atkins Foundation. In this study, 120 overweight but otherwise healthy adult subjects with elevated lipid levels followed either the Atkins Diet or a diet containing fewer than 30% calories from fat, 10% or fewer calories from saturated fat, less than 300 mg cholesterol, and a deficit of 500 to 1,000 calories. At 24 weeks, the Atkins group had lost a mean of 26 lb. vs. a mean loss of 14 lb. in the reduced-fat group. Triglyceride levels fell more in the Atkins group (–74 mg/dl) than in the restricted-fat group (–28 mg/dl) as well, and HDL levels increased in the Atkins group (5.5 mg/dl) while they decreased in the low-fat group (–1.6 mg/dl). The main criticism of this dietary study was that the so-called low-fat group received almost 30% of its caloric intake from fat, and the dieticians administering the dietary recommendations made no clear attempt to significantly restrict sugar and refined carbohydrate sources. Thus, the control diet with which the Atkins Diet was compared was significantly less than ideal.32

The findings from these clinical trials indicate that while adhering strictly to the Atkins Diet (dramatically reducing carbohydrate intake while allowing free access to high-fat and high-protein foods) can lead to more weight loss in the first six months, eating the diet described in the chapter “A Health-Promoting Diet” is associated with greater efficacy in the long run and is considerably better for health. Although the low-carbohydrate diet was associated with a greater improvement in some risk factors, on the basis of the current evidence we do not recommend the Atkins Diet. Furthermore, since the high protein content of the Atkins Diet stresses the liver and kidneys, we do not recommend it for anyone with impaired liver or kidney function. Our final concern is that on the Atkins Diet there is not much differentiation between high-quality proteins and fats and those of lower quality. For example, a person eating an Atkins-type diet can consume excessive amounts of carcinogens from meats and omega-6 fatty acids from corn-fed animals that can result in silent inflammation (see the chapter “Silent Inflammation” for a more complete discussion).

Several natural weight loss aids can help to either reduce appetite or enhance metabolism. In decreasing order of efficacy, we rate these items as follows:

• Fiber supplements

• Meal replacement formulas

• Chromium

• 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP)

• Hydroxycitrate

• Medium-chain triglycerides

Fiber Supplements

A tremendous amount of clinical evidence indicates that increasing the amount of dietary fiber promotes weight loss. The best supplemental fiber for weight loss is PolyGlycopleX, or PGX (discussed below), followed by glucomannan, gum karaya, psyllium, chitin, guar gum, and pectin, because they are highly viscous, soluble fibers. When taken with water before meals, these fiber sources bind to the water in the stomach to form a gelatinous mass that induces a sense of satiety. As a result, individuals are less likely to overeat.

The benefits of fiber go well beyond this mechanical effect, however. Fiber supplements have been shown to enhance blood sugar control, decrease insulin levels, and reduce the number of calories absorbed by the body. In some of the clinical studies demonstrating weight loss, fiber supplements were shown to reduce the number of calories absorbed by 30 to 180 per day. Although modest, this reduction in calories would, over the course of a year, result in a 3- to 18-lb weight loss.33,34

When choosing a fiber supplement, avoid products that contain a lot of sugar or other sweeteners to camouflage the taste. Be sure to drink adequate amounts of water when taking any fiber supplement, especially if it is in pill form.

Several studies have used guar gum, a soluble fiber obtained from the Indian cluster bean (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba), glucomannan from konjac root (Amorphophallus konjac), and pectin, with good results.35–40 In one study, nine women weighing between 160 and 242 lb were given 10 g guar gum immediately before lunch and dinner. They were told not to consciously alter their eating habits. After two months, the women reported an average weight loss of 9.4 lb. Reductions were also noted for cholesterol and triglyceride levels.35

An important consideration is that the effectiveness of fiber in reducing appetite, blood sugar, and cholesterol is directly proportional to the amount of water the fiber is able to absorb (water holding capacity) and the degree of thickness or viscosity it imparts when in the stomach and intestine. For instance, this ability to bind water and form a viscous mass is why oat bran lowers cholesterol and controls blood sugar better gram for gram than wheat bran.

Although there are many varieties of soluble fiber, PolyGlycopleX (PGX) is a completely novel matrix produced from natural soluble fibers (xantham gum, alginate, and glucomannan). PGX produces a higher level of viscosity, gel-forming properties, and expansion with water than the same quantity of any other fiber alone.41,42 PGX is able to bind roughly six hundred times its weight in water, resulting in volume and viscosity three to five times greater than those of other highly soluble fibers such as psyllium or oat beta-glucan. To put this in perspective, a 5 g serving of PGX in a meal replacement formula or on its own produces volume and viscosity that would be equal to as much as those produced by four bowls of oat bran. In this way, small quantities of PGX can be added to foods or taken as a drink before meals to have an impact on appetite and blood sugar control equivalent to eating enormous and impractical quantities of any other form of fiber.

Detailed clinical studies published in major medical journals and presented at the world’s major diabetes conferences have shown PGX to exert the following benefits:43–47

• Reduces appetite and promotes effective weight loss, even in the morbidly obese

• Increases the level of compounds that block the appetite and promote satiety

• Decreases the level of compounds that stimulate overeating

• Reduces postprandial (after-meal) blood glucose levels when added to or taken with foods

• Reduces the glycemic index of any food or beverage

• Increases insulin sensitivity and decreases blood insulin

• Improves diabetes control and dramatically reduces the need for medications or insulin

• Stabilizes blood sugar control in the overweight and obese

• Lowers blood cholesterol and triglycerides

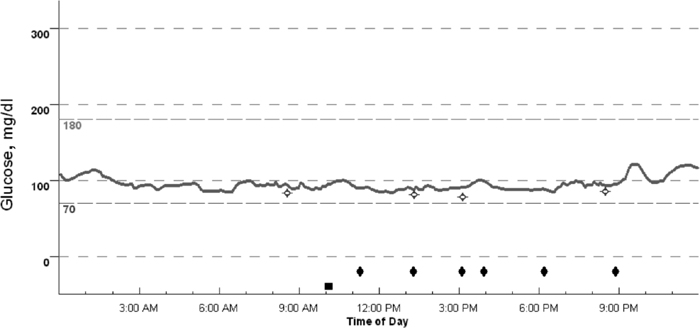

Groundbreaking research by Michael R. Lyon, M.D., has shown that people who are overweight spend much of their day on a virtual “blood sugar roller coaster.” Specifically, by using new techniques in two-hour blood sugar monitoring, it has been shown that excessive appetite and food cravings in overweight subjects are directly correlated with rapid fluctuations in blood glucose throughout the day and night. Furthermore, by utilizing PGX these same subjects can dramatically restore their body’s ability to tightly control blood sugar levels and that this accomplishment is powerfully linked to remarkable improvements in insulin sensitivity and reductions in calories consumed.

To gain the benefits of PGX it is important to ingest 1.5 to 5 g PGX at major meals, perhaps double that for those with an appetite more difficult to tame. PGX is available in a variety of forms: soft gelatin capsules, a zero-calorie drink mix, granules to be added into food and beverages, and a meal replacement drink mix. The key to effective use of PGX is to take it before every meal with a glass of water. Detailed studies in both humans and animals have shown that PGX is very safe and well tolerated. There are no specific drug interactions, but it is best to take any medication either an hour before or an hour after taking PGX. For more information, see www.PGX.com.

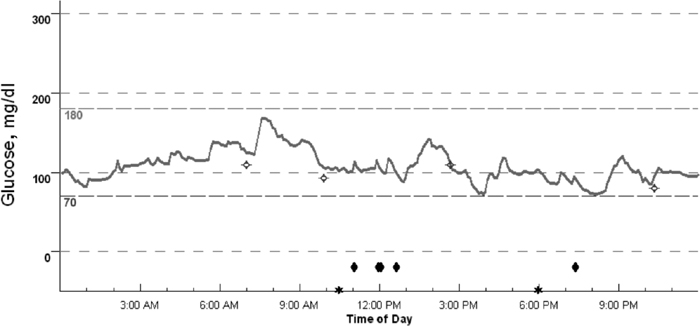

CGMS Graph 1

Uncontrolled and erratic blood sugar levels of an overweight woman over 24 hours with a poor diet and no physical activity.

CGMS Graph 2

Controlled and balanced blood sugar levels of the same woman after consuming PGX for six weeks and experiencing a healthy weight loss of 2 lbs. per week.

Meal replacement formulas are a popular weight-loss strategy. Their effectiveness has been confirmed in several clinical trials.48–54 In these studies, dietary compliance and convenience were viewed more favorably by participants who consumed meal replacement (MR) formulas than by those in a conventional weight-loss program. Ideally MR formulations should be of high nutritional quality: high in protein, low in glycemic load, and high in soluble fiber. A protein target of 2.2 g per kg of body weight per day is recommended.

Medifast is a popular physician-supervised weight loss program that relies heavily on MR formulas. In one 40-week randomized, controlled clinical trial that included 90 obese adults with a BMI between 30 and 50, subjects were randomly assigned to one of two weight loss programs for 16 weeks and then followed for a 24-week period of weight maintenance. The dietary intervention was either a meal replacement program (Medifast) or a self-selected food-based meal plan (FB) with an amount of calories equal to the Medifast plan. The Medifast plan included five meal replacement drinks (90–110 calories each), 5–7 oz lean protein, 11/2 cups nonstarchy vegetables, and up to two fat servings per day, providing a total of 800–1,000 calories. The meal replacements used in this study were low-fat, low-glycemic, and low-sugar; provided a balanced ratio of carbohydrates to proteins; and were based on either soy and/or whey protein. The food-based plan included 3 oz grains, 1 cup vegetables, 1 cup fruit, 16 fl oz milk, 5–7 oz lean protein, and 3 tsp fat per day, providing a total of about 1,000 calories per day. The FB group was also instructed to take a multivitamin and additional calcium to ensure that micronutrient needs were met while following a low-calorie meal plan. Weight loss at 16 weeks was significantly better in the Medifast group vs. the food-based group: 12.3% of starting weight vs. 6.9%, respectively. Significantly more of the Medifast participants had lost 5% or more of their initial weight at week 16 (93% vs. 55%) and week 40 (62% vs. 30%). Significant improvements in body composition were also observed in Medifast participants compared with FB at week 16 and week 40. At week 40, mean body fat had dropped among the subjects in the Medifast group by 2.9%, whereas the FB group decreased by 1.8%; lean muscle mass as a percentage of total weight was significantly increased by 4.5% from baseline to week 40 in the Medifast group, whereas the FB group did not experience any significant change. Blood pressure also dropped: at week 40, the Medifast group saw a reduction in systolic blood pressure of 6.0 mm Hg (4.5%), and the FB group experienced a drop of 8.3 mm Hg (6.5%). Diastolic blood pressure decreased by 5.5 mm Hg (6.20%) for the Medifast group, compared with 0.9 mm Hg (0.45%) in the FB group.53

Chromium

One of the goals for enhancing weight loss is to increase the sensitivity of the cells throughout the body to insulin. Chromium has recently gained a great deal of attention as an aid to weight loss, as it plays a key role in cellular sensitivity to insulin. The importance of this trace mineral in human nutrition was not discovered until 1957, when it was shown that it was essential to proper blood sugar control. Although there is no recommended dietary intake (RDI) for chromium, good health requires a dietary intake of at least 200 mcg per day. Chromium levels can be depleted by refined sugars, white flour products, and lack of exercise.54

In some clinical studies of type 2 diabetics, supplementing the diet with chromium has been shown to decrease fasting glucose levels, improve glucose tolerance, lower insulin levels, and decrease total cholesterol and triglyceride levels, while increasing HDL cholesterol levels.55 Obviously chromium is a critical nutrient in diabetes, but it is also important in hypoglycemia. In one study, eight female patients with hypoglycemia given 200 mg per day for three months demonstrated alleviation of their symptoms.56 In addition, glucose tolerance test results were improved and the number of insulin receptors on red blood cells was increased.

Chromium supplementation has been demonstrated to lower body weight yet increase lean body mass, presumably as a result of increased insulin sensitivity.57 In one study, patients were given either a placebo or chromium picolinate in one of two doses (200 mcg or 400 mcg) per day for 2.5 months.58 Patients taking the 200 and 400 mcg doses of chromium lost an average of 4.2 lb of fat. The group taking the placebo lost only 0.4 lb. Even more impressive was the fact that the chromium groups gained more muscle (1.4 vs. 0.2 lb) than those taking a placebo. The results were most striking in elderly subjects and in men. The men taking chromium picolinate lost more than seven times as much body fat as those taking the placebo (7.7 vs. 1 lb). The 400-mcg dose was more effective than the 200-mcg dose.

The results of these preliminary studies with chromium are encouraging. Particularly interesting is the fact that in these initial studies, chromium picolinate promoted an increase in lean body weight percentage, as it led to fat loss but also to muscle gain.59 Greater muscle mass means greater fat-burning potential. However, two clinical trials with women involved in an exercise program did not find any significant changes in body composition.60,61

All of the effects of chromium appear to be due to increased insulin sensitivity. Several forms of chromium are on the market. Chromium picolinate, chromium polynicotinate, chromium chloride, and chromium-enriched yeast are each touted by their respective suppliers as providing the greatest benefit. No firm evidence indicates that one is a significantly better choice than another.

5-Hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP)

5-HTP is the direct precursor to the brain chemical serotonin. More than three decades ago, researchers demonstrated that administering 5-HTP to rats that were genetically bred to overeat and be obese resulted in a significant reduction in food intake. Further research revealed that these rats have decreased activity of the enzyme tryptophan hydroxylase, which converts tryptophan to 5-HTP, itself subsequently converted to serotonin. In other words, these rats are fat as a result of a genetically determined low level of activity of the enzyme that starts the manufacture of serotonin from tryptophan. These rats don’t get the message to stop eating until they have consumed far greater amounts of food than normal rats. Circumstantial evidence indicates that many humans are genetically predisposed to obesity. This predisposition may involve the same mechanism as that in these genetically predisposed rats (i.e., decreased conversion of tryptophan to 5-HTP and, as a result, decreased serotonin levels). When preformed 5-HTP is provided, this genetic defect is bypassed and more serotonin is manufactured.

The early animal studies with 5-HTP as a weight loss aid have been followed by a series of three human clinical studies of overweight women.62–64 The first study showed that 5-HTP was able to reduce calorie intake and promote weight loss despite the fact that the women made no conscious effort to lose weight.62 The average amount of weight loss during the 5-week period of 5-HTP supplementation was a little more than 3 lb.

The second study sought to determine if 5-HTP helped overweight individuals adhere to dietary recommendations.63 The 12-week study was divided into two 6-week periods. For the first 6 weeks there were no dietary recommendations, and for the second 6 weeks the women were placed on a 1,200-calorie diet. The women taking the placebo lost 2.28 lb, while the women taking the 5-HTP lost 10.34 lb.

As in the previous study, 5-HTP appeared to promote weight loss by promoting satiety, leading to consumption of fewer calories at meals. All women taking 5-HTP reported early satiety.

A third study with 5-HTP was similar to the second study: for the first 6 weeks there were no dietary restrictions, and for the second 6 weeks the women were placed on a diet of 1,200 calories per day.64 The group receiving the 5-HTP lost an average of 4.39 lb after the first 6 weeks and an average of 11.63 lb after 12 weeks. In comparison, the placebo group lost an average of only 0.62 lb after the first 6 weeks and 1.87 lb after 12 weeks. The lack of weight loss during the second 6-week period in the placebo group obviously reflects the fact that the women had difficulty adhering to the diet.

Early satiety was reported by 100% of the subjects taking 5-HTP during the first 6-week period. During the second 6-week period, even with severe caloric restriction, 90% of the women taking 5-HTP reported early satiety. Many of the women receiving the 5-HTP (300 mg three times per day) reported mild nausea during the first 6 weeks of therapy. However, the symptom was never severe enough for any of the women to drop out of the study. No other side effects were reported.

Hydroxycitrate

Hydroxycitrate (HCA) is a natural substance isolated from the fruit of the Malabar tamarind (Garcinia cambogia), a yellowish fruit that is about the size of an orange, with a thin skin and deep furrows similar to an acorn squash. It is native to southern India, where it is dried and used extensively in curries. The dried fruit contains about 30% hydroxycitric acid.

HCA has been shown to be a powerful inhibitor of fat formation in animals.65,66 Whether it demonstrates this effect in humans has not yet been determined. The weight-loss-promoting effects in animals are perhaps best exemplified in a study that shows HCA producing a “significant reduction in food intake, and body weight gain,” in rats.67 Not only may HCA be a powerful inhibitor of fat production; it may also suppress appetite. It is critical in using an HCA formula that a low-fat diet be maintained, as it inhibits only the conversion of carbohydrates into fat.

By itself, HCA may offer a safe, natural aid for weight loss when taken at a dosage of 1,500 mg three times per day. In two clinical trials, a total of 90 moderately obese subjects (ages 21 to 50, BMI greater than 26) were randomly divided into three groups. Group A was administered HCA 4,667 mg; group B was administered a combination of HCA 4,667 mg, niacin-bound chromium 4 mg, and Gymnema sylvestre extract 400 mg; and group C was given a placebo. All subjects were provided a 2,000-calorie-per-day diet and participated in a supervised walking program for 30 minutes a day, five days a week. Eighty-two subjects completed the study. At the end of eight weeks, in group A, both body weight and BMI decreased by 5.4%, LDL cholesterol and triglycerides levels were reduced by 12.9% and 6.9% respectively, HDL cholesterol levels increased by 8.9%, and urinary excretion of fat metabolites increased between 32 and 109%. Group B demonstrated similar beneficial changes, but generally to a greater extent. Specifically, group B reduced body weight and BMI by 7.8% and 7.9%, respectively; food intake was reduced by 14.1%; total cholesterol, LDL, and triglyceride levels were reduced by 9.1, 17.9, and 18.1%, respectively, while HDL levels increased by 20.7%; and the excretion of urinary fat metabolites increased between 146 and 281%. No significant adverse effects were observed in either trial.68

Medium-Chain Triglycerides

Medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs) are saturated fats (extracted from coconut oil) that range in length from 6 to 12 carbon chains. MCTs are used by the body differently from the long-chain triglycerides (LCTs), which are the most abundant fats found in nature. LCTs, which range in length from 18 to 24 carbon chains, are the storage fats for both humans and plants. This difference in length makes a substantial difference in how MCTs and LCTs are metabolized. Unlike regular fats, MCTs appear to promote weight loss rather than weight gain.

MCTs may promote weight loss by increasing thermogenesis and energy expenditure.69–73 In contrast, the LCTs are usually stored in the fat deposits, and because their energy is conserved, a high-fat diet tends to decrease the metabolic rate. In one study the thermogenic effect of a high-calorie diet containing 40% fat as MCTs was compared with one containing 40% fat as LCTs. The thermogenic effect (calories wasted six hours after a meal) of the MCTs was almost twice as high as that of the LCTs, 120 calories vs. 66 calories. The researchers concluded that the excess energy provided by fats in the form of medium-chain triglycerides would not be efficiently stored as fat, but rather would be wasted as heat. A follow-up study demonstrated that MCT oil given over a six-day period can increase diet-induced thermogenesis by 50%.74

QUICK REVIEW

• A successful program for weight loss must be consistent with the four cornerstones of good health—proper diet, adequate exercise, a positive mental attitude, and the right support for the body through natural measures.

• Atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries) is present 10 times more often in obese people compared with those who are not obese.

• Obese individuals have a life expectancy that is on average five to seven years shorter than that of normal-weight individuals, with a greater relative risk for early mortality associated with a greater degree of obesity.

• As abdominal fat accumulates it leads to alterations in adipokines that ultimately promote insulin resistance and an increased appetite, thereby adding more abdominal fat.

• The reason why most Americans are overweight is that they eat too much fat and sugar and do not get enough physical activity.

• Television watching has been demonstrated to be linked to the onset of obesity, and there is a dose-related effect: the more TV watched, the greater the degree of obesity.

• Physiological theories of obesity are tied to brain serotonin levels, diet-induced thermogenesis, activity of the sympathetic nervous system, metabolism of fat cells, and sensitivity to the hormone insulin.

• Fiber supplements, especially PGX, have been shown to enhance blood sugar control and insulin effects, as well as reduce the number of calories absorbed by the body.

• 5-hydroxytryptophan reduces the number of calories consumed and promotes weight loss.

• One of the key goals for enhancing weight loss is to increase the sensitivity of cells throughout the body to the hormone insulin.

• Chromium supplementation has been demonstrated to lower body weight yet increase lean body mass, presumably as a result of increased insulin sensitivity.

• Medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs) may promote weight loss by increasing thermogenesis.

• Hydroxycitrate has been shown to be a powerful inhibitor of fat formation in animals.

TREATMENT SUMMARY

A successful program for weight loss must be consistent with the four cornerstones of good health detailed in these chapters:

• “A Positive Mental Attitude”

• “A Health-Promoting Lifestyle”

• “A Health-Promoting Diet”

• “Supplementary Measures”

All of these components are essential and interrelated.

• Foundational supplements as described in the chapter “Supplementary Measures”:

![]() PGX: 1.5 to 5 g before meals

PGX: 1.5 to 5 g before meals

![]() Chromium: 200 to 400 mcg per day

Chromium: 200 to 400 mcg per day

![]() Medium-chain triglycerides (optional): up to 1 to 2 tbsp per day

Medium-chain triglycerides (optional): up to 1 to 2 tbsp per day

![]() 5-HTP: for the first two weeks, 50 to 100 mg 20 minutes before meals; after two weeks, if weight loss has been less than 1 lb per week, double the dosage, to a maximum of 300 mg (high dosages can cause nausea, but this symptom disappears after six weeks of use)

5-HTP: for the first two weeks, 50 to 100 mg 20 minutes before meals; after two weeks, if weight loss has been less than 1 lb per week, double the dosage, to a maximum of 300 mg (high dosages can cause nausea, but this symptom disappears after six weeks of use)

• Hydroxycitrate (from G. cambogia): 1,500 mg three times per day

In another study, researchers compared single meals of 400 calories composed entirely of MCTs or LCTs.75 The thermic effect of MCTs over six hours was three times greater than that of LCTs. In addition, while the LCTs elevated blood fat levels by 68%, MCTs had no effect on the blood fat level. Researchers concluded that substituting MCTs for LCTs would produce weight loss as long as the calorie level remained the same.

In order to gain the benefit from MCTs, a diet must remain low in LCTs. MCTs (or coconut oil) can be used as an oil for salad dressing or as a bread spread, or simply taken as a supplement. A good dosage recommendation for MCTs is 1 to 2 tbsp a day.