Chapter 6

Kokoda

‘We were very good at executing night attacks. We had experience of this in China. We kept shooting all night’

—Imanishi Sadaharu, of the Tsukamoto Battalion, which launched the first attack on Kokoda

Captain Sam Templeton was a quiet, considerate man in his early fifties, of great mental and physical stamina. He had been a naval reserve gunner in World War I, and was reputed to have fought in the Spanish Civil War. ‘Uncle Sam’, as the troops called him, was too old to serve abroad in the Australian Imperial Force. He spoke rarely, with a slight Northern Irish accent, usually after the hurricane lamps had been doused. Darkness loosened his inhibitions.1 Remote and enigmatic, Templeton’s age and combat experience were reassuring to younger troops, who looked on him as a father figure. They would follow him anywhere, and indeed they did.

Templeton led the first company of Australians over the mountains, with Kienzle as his guide. This was B Company of the 39th Battalion. The march was less arduous than it would later prove for the AIF troops who had to carry full packs and ammunition in pouring rain. The Papuan climate in early July was relatively benign, being the end of the ‘dry’ season; the daily monsoonal deluge would start promptly in September. And Kienzle’s carriers were on hand to shoulder much of the equipment. Even so, it was an exhausting initiation to the Owen Stanleys.

The less fit troops couldn’t carry their loads and Warrant Officer Jack Wilkinson, an AIF veteran of the Greek campaign, lent a hand. He and Templeton shouldered four rifles and three haversacks between them up one ascent. ‘Uncle Sam insisted on carrying all my gear as well as that of others,’ Wilkinson wrote in his diary. Wilkinson’s drinking habits were interesting: ‘Made a brew of rum and lime and hot water, which revived some. Many non-drinkers among these kids. Rum turned out to be mostly metho…’2

Perhaps an exaggerated rumour, or poor communications, led to Port Moresby’s bleak report on the state of these troops. General Morris wired Brisbane on 17 July that ‘33%’ of the men were unfit for action after their hike to Kokoda: ‘request urgent advice aircraft for troop carrying to Kokoda’.3

On the contrary, Uncle Sam’s men reached Kokoda in fairly good shape; only one fell by the side of the track due to dysentery. En route, they ate bananas and pawpaws, and at Kokoda Kienzle shared out food from his farm in the Yodda valley. In any case, Morris received no advice on airlifting the men to Kokoda, nor any explanation for the lack of planes. Brisbane simply ignored him.

Twenty tons of stores awaited Templeton at Buna. His company arrived there on 19 July, two days before the enemy landed. He loaded up a long line of carriers, and set off back to Kokoda. As his patrol rested, on the 21st, he heard a distant rumble on the horizon. He gazed over the green apron of palm groves that spread to the sea. The sound seemed to issue from a thundercloud at the base of a tropical storm. But there was only light cloud cover that afternoon.

At Buna Government Station—which was being attacked—Sergeant Barry Harper relayed the message: ‘A Japanese warship is shelling Buna…to cover a landing at Gona or Sanananda. Acknowledge, Moresby. Over…’4 Harper received no reply from Port Moresby. But three coastwatchers—all soon to be killed by the Japanese—picked up the message at Ambasi, 40 miles north-west of Buna, and relayed it to Moresby. Templeton soon learned the cause of the boom. He ordered a platoon (of about thirty men) forward. He had no idea of the scale of the landing, and continued back to Kokoda to meet his battalion’s commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel William Owen.

The lone platoon, led by Lieutenant Arthur Seekamp, marched through the night and reached the village of Awala at 11.00 a.m. on 22 July. They dumped their packs and prepared to meet the enemy. Within hours the first of Tsukamoto’s forward scouts, moving nimbly south from the coast, appeared and, in a lightning manoeuvre, encircled Seekamp’s platoon. The speed and physique of the Japanese troops astonished the Australians, who had been led to think of ‘the Jap’ as a ‘little yellow, bespectacled fellow’: ‘The first Jap I hit was six feet two inches and 15 stone…’ recalled a stunned Lieutenant Doug McClean of the 39th Battalion. ‘Their movement in the bush had to be seen to be believed…they’d just vanish. Their field craft and movement was magnificent.’5

The enemy were not, in fact, all fleet-footed sumo wrestlers; the point was that the Australians perceived them as larger that the clichéd image in their minds. There were a few extreme cases among the crack troops of the Yokoyama infantry. But most were simply well-built, well-trained men. Later, a shorter, clumsier Japanese soldier—closer to the stereotype—appeared, but that didn’t dispel the rumour of thousands of Japanese supermen crashing through the undergrowth towards Port Moresby.

Okada Seizo, the Asahi Shimbun war correspondent attached to the Yokoyama Advance Force, described the advance troops in more pedestrian terms: ‘…the unit continued to walk with single-mindedness…day and night. Each man was required to carry provisions for thirteen days in his backpack, comprising 18 litres of rice, a pistol, ammunition, hand grenades, a spoon, first aid kit, [approximately 100 pounds]…The backpacks loaded with this luggage rose about 30 cm above the heads of the soldiers. They would walk step by step with staff in hand, using it as an extra leg to propel them along.’6

Some slept in riverbeds, and a few troops drowned when flash floods surged through their camp sites. They knew little of the terrain and had had little jungle experience—contrary to what most Australian sources had maintained. Senior Japanese intelligence officers misread maps and photos, and most seemed to think a road connected Kokoda to Port Moresby.

What they had in speed and experience, they lacked in firepower. Their light arms were inferior to the Australians’. They did not possess automatic weapons of the quality of the Bren and Tommy guns, both of which were relatively light and efficient.

Imanishi said his troops typically carried a Type 38 bolt-action rifle that shot five rounds, and was designed in the Meiji period. Their grenades were left over from the Russo–Japanese war of 1904–05; they would not explode unless struck on the ground at a 45-degree angle (later, some Japanese would commit suicide by striking these against their heads). They did have, however, two remarkable weapons: the wheel-mounted mountain artillery (carried in pieces) and the Juki heavy machine-gun, both of which inflicted terrible casualties on Allied forces. Astonishingly, they lugged these weapons over the mountains. Both far exceeded in destructive power anything in the Australian arsenal during the first phase of the battle.

Another weapon the Japanese deployed in droves was the human bullet. Suicide squads hurled themselves at the enemy to draw their fire and frighten them into submission. The Japanese outnumbered the Australians by ten to one at Kokoda and at least three to one at Isurava. There seemed no shortage of volunteers for suicide squads, at least at the start of battle, and Australian veterans remember night attacks by squads of human bullets—the Japanese excelled at night attacks—as the most terrifying experience of the war.

Seekamp’s little Australian patrol fell back to the Kumusi River, at Wairopi (pidgin for ‘wire rope’ bridge) in the early hours of 24 July. The river is about sixty yards wide here; the depth depended on the rains, which could turn a gentle current into a swirling torrent. At 9.00 a.m., they received Templeton’s signal to pull out: ‘Reported on radio broadcast that 1500–2000 Japs landed at Gona Mission Station…in view of the numbers I recommend that your action be contact and rearguard only—no do-or-die stunts. Close back on Kokoda.’7 Accordingly, they ripped up the footboards, slashed the cables, and sent the wire bridge crashing into the river. Twenty men—two sections—remained on the southern shores of the Kumusi, and two machine-gunners set up either side of the little bridge spanning Gorari Creek.

The Japanese waded the river, and the advance troops walked into the Australian ambush; fifteen were shot dead. The setback did not detain them long. Snipers, scurrying up trees, poured fire onto the Australian gunners, who retreated back to Templeton’s company at Oivi. The resistance briefly surprised, but did little to dent, Tsukamoto’s push to Kokoda.

‘There was some resistance and a few casualties,’ said Imanishi. ‘But I was a bit behind. I had to carry my bicycle on my shoulders across the Kumusi.’ He threw it away further up: ‘I thought there’d be a road; I saw it was useless.’8

Lieutenant-Colonel Owen flew into Kokoda on 23 July. A survivor of the invasion of Rabaul, he was under no illusions about the determination of the Japanese soldier. He listened closely to Templeton’s report and signalled Port Moresby for reinforcements: ‘must have two companies…must have fresh troops…to avoid being outflanked’.

Military jargon is full of anodyne phrases the purpose of which is to normalise the process of killing the enemy. To be outflanked along a jungle path meant, in effect, encirclement and probable destruction. This was the danger at Oivi, an elevated strip of land where Templeton’s troops were being comprehensively outflanked. They dug a trench with their bayonets and steel helmets, and waited. Behind them were the foothills of the mountains, in front, the coastal plain.

Owen wanted at least 200 men. He got 30. The first fifteen flew into Kokoda in the morning of 25 July, and he sent them off straightaway. One sergeant asked the way. Owen pointed, bellowing, ‘Follow that track and you’ll get there!’

The reinforcements never got there. Templeton’s men were trapped in a classic Japanese pincer movement—a miniature precursor of the vast outflanking manoeuvres to come. Unaware of the extent of their predicament, Uncle Sam set off alone back up the track to warn the arriving reinforcements not to come forward. He was never seen again. His men heard only a machine-gun burst in the forest behind them. Stories later went that he was badly wounded and died in Japanese captivity. Indeed, Templeton is cited as the source for the Japanese belief that they faced a thousand Australians at Kokoda—an exaggeration, possibly elicited under threats or torture, to dent Japanese self-confidence. ‘Templeton’s Crossing’, a camp site by the banks of Eora Creek, now bears his name.

Cut off without a leader, the troops cursed themselves for letting Uncle Sam leave unaided. As night fell, the Japanese taunted the remaining Australians—young, leaderless militia. They hacked through the scrub, banged their mess tins and shouted orders in English: e.g. ‘Come forward Corporal White!’9 The 39th replied by rolling grenades down the hill.*

It was dark when a native police boy, Lance-Corporal Sinopa, led the unit to safety along the Oivi Creek, a feat for which he won a Military Medal. Each man held the bayonet scabbard of the man in front, and some reportedly used the phosphorescent fungus on the jungle floor as ‘headlights’.10 From behind came a burst of machine-gun fire, as the Japanese poured into the empty clearing.

The retreating troops reached Kokoda at dawn, and found the plateau deserted. Stores and huts were burnt down and still smouldering, supplies destroyed: the result of Owen’s rash scorched-earth policy. The battalion commander had hastily abandoned Kokoda for Deniki, a village a few hours’ south-east, just forward of Isurava. Owen’s sudden withdrawal was a mistake: it handed the Kokoda airstrip to the invaders without a shot being fired. Realising this, the commander of the 39th returned to Kokoda the next day, to defend the vital airstrip. He atoned for his error with the supreme sacrifice.

Kokoda is an orderly government station set on a tongue-shaped plateau protruding from the Owen Stanley Range at the northern end of the eponymous track. The tongue juts out over a wide valley, and the area has a reassuringly open feel for troops about to enter, or emerge from, the jungle-clad mountains to the south. In 1942, Kokoda’s little huts, gardens, school, airstrip and hospital—the few oddments of civilisation—seemed thrown together in meek defiance of Nature’s encroaching chaos. Strategically vital for its airstrip and commanding location, Kokoda marked the link with civilisation in an otherwise inhospitable land, and the troops held this outpost in great affection—as do hikers today.

To the north-east, the short escarpment falls away to the Mambare River and the coastal plain of the Gona–Sanananda–Buna littoral. To the

south-east Fiawani Creek, a tributary of Eora Creek, feeds into the Mambare River via a narrow gorge; west is the airstrip, and beyond it, dense jungle rising to a high ridgeline which eventually becomes the Naro Ridge.

Leading out of Kokoda heading south is a lane, lined in 1942 by a rubber plantation (and today, by ginger plants and palm groves). After a few miles the lane narrows into the famous little track (or trail, or path) bearing the name Kokoda, which gradually ascends the first mountain in the Owen Stanley Range towards the villages of Deniki and Isurava.

‘To us [Kokoda] was paradise,’ said Jack Lloyd of the 39th Battalion. For one thing, the lush gardens supplemented their dreary ration of bully beef, biscuits and baked beans with delicious fresh fruit, bananas, pawpaws and wild passion fruit.

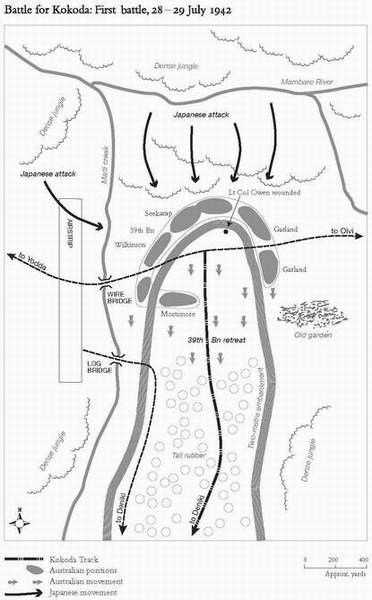

Owen strode about the edge of the Kokoda plateau in apparent command of the situation; he deployed his meagre force—the same men of B Company, of the 39th Battalion—along the tip of the escarpment, where he expected Tsukamoto’s advance unit to attack. The invader soon did. At 2.00 a.m. on 29 July, about 400 of Tsukamoto’s 900-strong force charged up the short, steep slope. It was a classic nocturnal charge; they shouted and sometimes chanted, and fell on the Australians with apparent unconcern for their own lives. ‘We were ordered to occupy the airfield at Kokoda,’ recalls Imanishi. ‘No one knew there was a hill; we knew nothing of the terrain. But we were very good at executing night attacks. We had experience of this in China. We kept shooting all night.’11

The shocked 39th responded with a couple of machine-guns, grenades and rifle fire; they had not expected anything like this. Their resistance briefly delayed the enemy, whose front-line troops soon scrambled onto the plateau. Both sides merged in a melee of hand-to-hand combat.

The gathering mist obscured the moonlight, and bloody chaos ensued. Men were bayoneted in the darkness. One Australian officer shouted for help to his neighbouring troops; they happened to be Japanese, and hurled grenades at the voice in the darkness. A sniper’s bullet hit Owen in the head. He fell off the edge of the escarpment into a weapon pit. Captain Geoffrey Vernon, then the battalion’s medical officer, climbed down the slope with stretcher-bearers. They found Owen ‘propped up in a narrow place struggling violently yet more than semi-conscious, quite unable to realise where he was…’12 They hauled him up the escarpment. The ‘Japs [were] moving and whispering in the grass’, recalled Jack Wilkinson, as he assisted Vernon. The bullet had penetrated Owen’s skull above the right eye. There was no exit wound. The dying commander looked strangely on the faces of his men. Brain tissue protruded from the wound. He fell unconscious, his body convulsed, and settled. ‘A hopeless case,’Wilkinson recorded.13

Vernon and Wilkinson worked desperately in their medical hut—dressing wounds and sending the wounded back through the rubber plantation—as scores of fresh Japanese troops stormed the plateau in the forward area. As Vernon recalled: ‘Wilkinson held the lantern for me and every time he raised it a salvo of machine-gun bullets was fired at the building.’14

They stayed with Owen, who lay in a coma, until the last moment: ‘We fixed up the Colonel,’ said Vernon, ‘who was now dying, as comfortably as possible, moistening his mouth and cleaning him up. Then I stuffed our operating instruments and a few dressings into my pocket, seized the lantern, and went out toward the rubber.’ Owen lasted perhaps fifteen minutes.15

The Australians managed to salvage most of their weapons, although the Japanese did capture 180 grenades, 1850 rifle rounds and five automatic weapons, according to an enemy sitrep. It added: ‘The [Australians] are skilled marksmen and expert grenade throwers.’16 No doubt there were quite a few good cricketers in the militia. An enemy Intelligence Report observed that the Australians ‘have greater fighting spirit…[than] English, American and Filipino troops’.17

The 39th retreated along the Kokoda Track; the walking wounded hobbled to safety. The early morning mist, like billowing smoke, spilled off the Kokoda plateau to the Mambare River: ‘Thick white streams…stole between the rubber trees and turned the whole scene into a weird combination of light and shadow,’ wrote Vernon, who had a poet’s command of the language. The troops climbed by the moonlight, which occasionally shone on the path through the mist. With the Japanese in control of Kokoda, the Australians withdrew to the village of Deniki, on the first ascent of the Owen Stanleys.

During the pre-dawn retreat to Deniki, Captain Vernon lingered beneath a rubber tree on the Kokoda plateau. It had been ‘dinned’ into him that the place of a medical officer was at the end of a retreating column.18

This gentle Sydney doctor, on whose grave is inscribed the words ‘A friend to all men’, took his responsibilities to the letter. As he waited, his mind curiously contemplated the ‘weirdness’ of the natural world around him, and the sadness of the soldiers’ place in it. He later wrote this beautiful passage, oft-quoted because it evokes the very mood of the place: ‘[there was] the mysterious veiling of trees, houses and men, the drip of moisture from the foliage, and at the last, the almost complete silence, as if the rubber groves of Kokoda were sleeping as usual in the depths of the night, and men had not brought disturbance’.19

Vernon remains unsung. He was a hero of the Kokoda campaign, chiefly for his unusual devotion to the care of the troops and the Papuan carriers. Born on 16 December 1882 in Hastings, England, he immigrated to New South Wales where his father was made government architect. He attended the Sydney Church of England Grammar School and Sydney University.

During World War I he was concussed by enemy fire, probably at Gallipoli, where he served as a captain in the Australian Army Medical Corps. He suffered partial deafness for the rest of his life, of which he later wrote: ‘…being very deaf, from concussion…on Active Service 1915, I do not gather much information from others. I therefore miss much that goes on, including the many rumours and false reports that constantly passed along the line, and the absence of these may be an advantage.’20

As regimental medical officer of the 11th Light Horse, he won the Military Cross for ‘conspicuous gallantry’ at the battle of Romani in 1916. Though wounded, ‘he went beyond the Australian lines at night to attend and bring back an injured man’.21

The outbreak of World War II found him, a rubber planter, in the hills of west Papua, where his tall, khaki-clad frame and tanned, leathery skin was a familiar sight. He volunteered for the Papuan Infantry Battalion in February 1942, aged 60, and established a hospital at Ilolo, near the start of the Kokoda Track.

Vernon crossed the Owen Stanleys in July 1942 to make himself useful. Passing through Efogi, on his way to Kokoda, he heard from a tribal police runner that the Japanese had landed at Gona. ‘I’ll go on,’ he said. ‘There’s no medical officer with those 39th youngsters.’

In the months ahead, Vernon quietly allotted himself the job of caring for the fuzzy wuzzy angels, the native stretcher-bearers who would carry out Australia’s wounded. Most officers had little time to think of their needs. Yet their villages and gardens were plundered and destroyed, and their people displaced, as the war crashed across their land. Vernon requisitioned blankets, medicines and food for them, and helped to ease their terror of bombardment and machine-gun fire. He spoke to their souls and found a beautiful and willing response.

Hank Nelson wrote of Vernon:

…with his white hair and body so thin there seemed only a sheet of brown paper covering his bones…he became one of the most remembered men on the Trail. He doctored and comforted black and white, boosting the morale of the carriers, protecting them from over-work and ensuring they were properly fed and clothed. His own frailty was partly because he gave his rations to the carriers. Vernon was one of the few Australians present at both the fall and recapture of Kokoda. ‘This’ he said of the Kokoda Campaign, ‘should bind us to the Papuan race.’22

The doctor continued smoking under his rubber tree, awaiting stragglers. Two soldiers passed, Major W. T. Watson and Lieutenant Peter Brewer, and urged him to join them. He stayed.

‘Snowy’ Parr, and another private, were in fact the last soldiers out. Parr, a young Bren gunner who had just learned to use his weapon, had watched the death throes of Owen, his respected commander, with a silent rage. Parr then hid on the threshold of Kokoda and waited until two dozen Japanese troops stood around celebrating. From a range of 60 yards, toting the weapon at shoulder height, he emptied a full magazine at the crowd, killing about twenty Japanese. He then hastened cheerfully back through the rubber plantation. ‘You couldn’t miss,’Vernon heard him say to his mate as they passed.

Vernon then withdrew, the last man out. At Deniki he was relieved as the 39th Battalion’s temporary medical officer by Captain John Shera. He went back to the Eora Creek field hospital, where he took charge of the casualties there—both sick and wounded, black and white.

The first battle for Kokoda was, in terms of casualties, tiny. Yet the count revealed a Japanese readiness to tolerate huge losses. Of the Australians, there were just six killed and five were wounded. For these, 40 Japanese died, according to one captured Japanese document.23 Another source counted eighteen Japanese dead, and 45 wounded. Lieutenant Noda Hidetaka, of the 3rd Kuwada Battalion, summed up: ‘our Advance Force has been engaged in battle with 1,200 Australians and has suffered unexpectedly heavy casualties…’24 The Yazawa and Yokoyama Battalions respectively reported 1000 and 1200 Australian troops at Kokoda. There were in fact 77 Australian troops at the first battle of Kokoda.

Yet the 39th had lost its commander, Owen, and a company commander, Templeton, within days. The loss of much-admired senior officers deeply depressed the younger troops. Unlike the Japanese, who were inured to battle and bloodshed, few of the Australians had ever seen a corpse. A number ran away when their officers fell. Others, such as Parr, experienced a general hardening of the mind. To the untutored soldier of the 39th, revenge became the battle cry, the revenge of fallen mates. Mateship was not contrived or clichéd, it was real. Laurie Howson, recalling later how his sergeant, ‘Bunny’ Pulfer died, said, ‘Your mate alongside you became your mother, father and God all rolled into one.’25